Abstract

One strategy to promote workforce well-being has been health incentive plans, in which a company's insured employees are offered compensation for completing a particular health-related activity. In 2015, Providence Health & Services adopted an Advance Care Planning (ACP) activity as a 2015–2016 health incentive option. More than 51,000 employees and their insured relatives chose the ACP incentive option. More than 80% rated the experience as helpful or very helpful. A high proportion (95%) of employees responded that they had someone they trusted who could make medical care decisions for them, yet only 23% had completed an advance directive, and even fewer (11%) had shared the document with their health care provider. The most common reason given for not completing an advance directive was that health care providers had never asked about it. These findings suggest that an insured employee incentive plan can encourage ACP consistent with the health care organizations' values and strategic priorities.

Keywords: : advance care planning, health incentive, advance directive, employer, whole-person care, workforce health

Introduction

For a majority of Americans, health care insurance is paid for through an employer-based system.1 This approach contrasts with most developed countries in which insurance or direct access to medical care is provided by governments. Although there are complexities and shortcomings to this employer-based system, one potential advantage is that corporations, as well as federal and state governments and other public employers, have a financial stake in their employees' well-being.2 In addition to lowering direct costs and insurance premiums, healthier employees contribute to overall productivity by reducing absence from work and ameliorating presenteeism, or diminished performance while at work.3

One strategy to promote workforce well-being has been wellness incentive plans, in which eligible individuals who are insured under corporate health plans are offered rewards in the form of direct compensation, reduced medical premiums, or other cost-sharing discounts, for completing a particular health promotion activity.4,5 Alternately, some incentive programs charge employees higher fees for not engaging in health improvement activities or refraining from unhealthy behaviors.6 Traditionally, incentive plans have focused on reducing the underlying lifestyle risks associated with chronic conditions through activities related to smoking cessation, dietary modification, increasing exercise, and improving body mass index.4 Although short-term impact can frequently be seen, most interventions are designed to improve long-term health and the overall need for health care services.4,7 For corporations that deliver health care, such wellness incentive plans may have the additional benefit of encouraging employees to model the healthy behaviors that the corporation seeks to promote within the patient populations it serves.

Patient-centeredness, a core attribute of health care quality, entails delivery of care that is consistent with patients' wants, needs, and preferences.8 The first practical step to achieving this patient-centered, goal-aligned care is for providers, patients, and (usually) families to have 1 or more conversations about what a person's preferences and priorities would be in the context of a life-threatening condition or life-altering medical event with an uncertain prognosis. Numerous studies have demonstrated that goal-concordant care is associated with better quality and patient satisfaction, improved health of the population, and controlled health care costs.9–12

Advance directives are designed to enable an individual to express his or her wishes and, importantly, to appoint another individual as health care proxy to make medical decisions on his/her behalf should he/she become incapacitated and unable to make contemporaneous decisions. Multiple professional and public advocacy groups recommend that all adults aged 18 years and older should complete an advance directive and have a conversation with their primary health care provider about these wishes.13–15 These conversations are encompassed by the term advance care planning (ACP). Despite numerous public education efforts over nearly 3 decades, rates of ACP conversations and completion of advance directive documents remain low. In a recent large survey, only 27% of individuals had spoken to a loved one about their wishes for treatment and care if they were to have a life-threatening condition.16 Even fewer (23%) had recorded their wishes in writing or had an ACP conversation with their health care provider (7%).17

In 2015, Providence Health & Services (PH&S) used the upcoming year's health incentive plan to encourage ACP conversations and completion of advance directives among its insured employees.

Methods

PH&S is a not-for-profit health care system that at the time of this initiative encompassed more than 56,000 health insurance eligible employees operating 34 hospitals and 600 physician clinics. It is committed to enhancing goal-aligned, whole-person care for its patients and, as an employer, is committed to the well-being of its workforce. The Institute for Human Caring, a quality improvement program within PH&S, proposed an ACP activity as a 2015–2016 health incentive option. This initiative is 1 component of the Institute for Human Caring's multifaceted approach to fostering a culture of whole-person care, which includes establishing ACP and goals of care conversations as common expectations of clinicians, patients, and families alike.

The Institute for Human Caring's proposal to focus the insured employee health incentive plan on ACP was presented to the senior leadership of PH&S at a meeting of the Healthcare Operations Council on February 11, 2015. The proposal emphasized the initiative's congruence with PH&S’ mission and core values, “Triple Aim” health services goals, the modeling of healthy behaviors and employee well-being. The Council unanimously approved the proposal and sent a recommendation to the company's human resources department to incorporate this initiative within the organization's 2015–2016 employee benefits program.

Incentive program design

Participant activities: informational video, reflective survey, identified goal

For the 2015–2016 benefits open enrollment cycle, those PH&S employees eligible for health insurance (ie, work 20 or more hours per week) and actively enrolled in the health insurance plan were provided 2 options to earn a 2015–2016 health incentive – one that focused on ACP, and the other a traditional health risk reduction assessment. Employees who selected the ACP option were asked to watch a 4-minute online video that discussed the importance of ACP (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uzhpsw2onuI) and then complete an online survey about their personal attitudes regarding ACP (Table 1). Participants could select a single response to each reflective question from a pre-populated list of potential responses. Three survey items had the option for additional free-text responses. At the end of the activity, participants were asked to commit to a goal for the coming year from a list of potential responses (Table 2). Electronic surveys were conducted independently by RedBrick Health, the contracted wellness program administrator for the PH&S health incentive plan.

Table 1.

Survey Questions and Responses of Participants to Reflective Questions

| Percent of responses (number) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflective question | Yes | No | Unsure |

| Is there someone you trust to make medical care decisions on your behalf if you are unable to speak for yourself? | 95% (48,980) | 2% (1,012) | 3% (1,824) |

| Does the person you trust know that in the event of a critical accident or serious health condition, you would want him or her to make those decisions for you? | 82% (42,468) | 9% (4,436) | 9% (4,913) |

| Have you created an advance health care directive – such as a durable power of attorney or living will – or other written statement of your wishes regarding medical treatment? | 23% (11,989) | 74% (38,209) | 3% (1,628) |

| Have you given your doctor or health care provider a health care directive, and/or is that noted in your medical record? | 11% (5,746) | 83% (42,776) | 6% (3,286) |

| When you think about medical care at the end of your life, do you worry about: | |||

| Neither, I do not worry about this. | 50% (25,906) | ||

| Not getting enough medical care. | 17% (8,881) | ||

| Getting too much medical intervention. | 6% (14,139) | ||

| Other:_____ | 6% (2,898) | ||

| If you have not created an advance care directive, what is the main reason: | |||

| My health care provider has never asked about advance directives. | 33% (14,168) | ||

| I don't have enough information. | 17% (7,426) | ||

| I (and/or my family) don't want to think about this subject. | 12% (5,098) | ||

| It sounds as though I'd need to hire an attorney. | 9% (3,980) | ||

| Other:_____ | 29% (12,210) | ||

Table 2.

Respondent's Commitment Toward a Goal

| Pick at least one goal that you will work on this year (multiple selections allowed) | Percent of respondents (number) |

|---|---|

| I will start a conversation with my loved ones about this subject. | 37% |

| Below are some questions for discussion with your loved ones: | (19,286) |

| • If you had 6 months to live, how would you want to spend the time? What would you do? Who would be with you? Could you plan those now? | |

| • Are there people you have lost touch with that you'd like to contact? Could you reach out to them? | |

| • Your will is a list of things you will give away when you die. What gift could you give away now? | |

| • What would you hope people would say about you at your funeral or memorial service? | |

| I will talk to my health care provider about advance care planning, including advance directive documents, at my next visit. | 26% (13,673) |

| I will learn more about advance directives (written statement of a person's wishes for medical treatment), palliative care, or hospice services. See the More Resources page for additional advance care planning resource. | 18% (9,219) |

| I will update my life insurance and savings plan beneficiaries. | 17% (8,838) |

| I already have my advance care directives on file with my provider. I will encourage others to do the same. | 7% (3,643) |

| I will find a primary health care provider | 6% (3,088) |

| Other:_____ | 4% (2,005) |

Financial incentives

Each employee who completed the survey within the open enrollment period earned a financial incentive that was tied to his/her 2016 health plan election. PH&S also offers health benefits for the employee's spouse or adult benefits recipient (ABR) and children. For employees whose spouses or ABRs were enrolled in their medical plan, both adults were invited to participate in the incentive activity. An ABR is someone who has been and will continue to be part of the employee's family, whether legally related or not. Specifically an ABR is someone who: shares a committed, close personal relationship of mutual caring; is 18 years of age or older; must not be the employee's child younger than age 26; must rely on the employee for financial support; must have lived with the employee for at least 12 months prior to enrollment and continue to do so for the upcoming enrollment year; and must not have access to other medical coverage. Employees who were enrolled in a preferred provider organization (PPO) plan received $700 deposited into the account associated with their plan—either a health reimbursement account or health savings account—as a lump sum in January 2016. Additionally, for those enrolled in a PPO plan, an additional $700 was provided if an employee's covered spouse/ABR also completed the survey. Those enrolled in a health maintenance organization plan received $400 for themselves and an additional $400 if their spouse/ABR participated. This amount was divided into twice-monthly payments that reduced the employee's medical premiums for 2016.

Individuals included in this study were presented an online privacy policy through the wellness platform portal describing the measures in place to protect their Personal Health Information and the use of data in accordance with the Privacy Rule of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 and client-specific agreements. All data were de-identified prior to attainment by researchers for analysis.

Results

In December 2015, PH&S had 49,700 benefits-eligible employees and 18,134 benefits-eligible spouses/ABRs. For the 2015–2016 benefits open enrollment cycle, 39,389 (79%) of eligible employees and 12,237 (67%) of eligible spouses/ABRs fully completed either health incentive option. Additionally, 1556 eligible employees and spouses/ABRs only partially completed an activity. Of the individuals who completed an activity, 37,892 eligible employees (96%) and 11,965 (97%) eligible spouses/ABRs completed the ACP activity, while the remainder elected the health self-assessment activity.

A high proportion (95%) of participants in the ACP activity responded that they had an individual they trusted who could make medical care decisions for them if they were unable to do so on their own. Only a small proportion (23%) had completed any formal documentation to this effect, and even fewer (11%) had shared a completed advance directive with their health care provider (Table 1). The most common reason (33%) expressed for not having an advance directive was that the respondent's health care providers had never asked about it, highlighting a pattern of practice that may contribute to potential care misalignment.

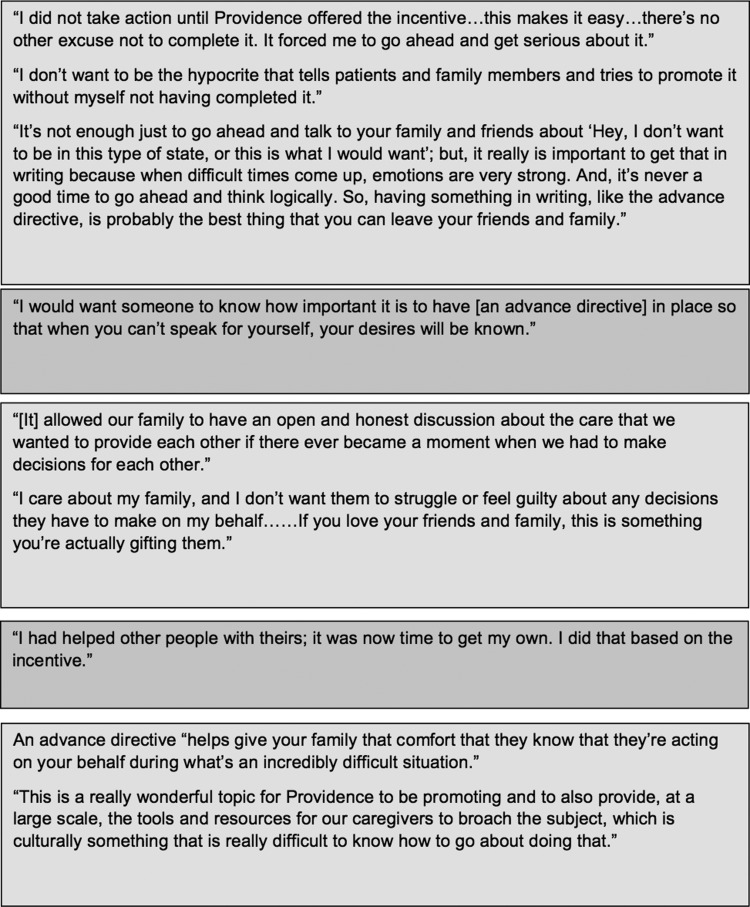

Individuals also were surveyed on helpfulness of this initiative; 81% of participants either somewhat agreed (46%) or strongly agreed (35%) that the activity was helpful. Participants committed to future goals related to ACP (Table 2). Participants were allowed to select multiple goals for the year, although a plurality of respondents selected only 1 option (43%). The most common goal selected was that the participant would start a conversation with his/her loved ones about this subject (37%). Free-text feedback from participants illustrates that these activities constructively influenced people's attitudes and behaviors (Figure 1).

FIG. 1.

Representative quotes from the initiative results video.

Discussion

Employers have both ethical and moral reasons, as well as legitimate business interests, for promoting well-being of their workforce.7 Demographic and business trends have heightened the value of employee health and health care. Individuals are working to older ages and health care costs continue to rise.18,19 More employers are offering high-deductible plans as a way to control costs and share financial risk with their employees.20 Although health incentive plans can be misused, they represent 1 strategy by which employers can foster healthy behaviors. When the employer is a health care system, this strategy carries the additional potential of fostering a culture within its workforce that normalizes the healthy behaviors that the provider organization seeks to promote among its clientele.

A major organizing theme within health care reform has been the centrality of patient-centered care, which at its core is goal-aligned care.8 There is broad agreement about the ethical and clinical importance of every adult choosing a trusted person to speak on his or her behalf in making medical decisions at a future time of incapacity. Similarly, consensus exists that patient-centeredness requires opportunities for people to express their personal values, preferences, and priorities in situations of life-threatening conditions. However, these are sensitive conversations that at times evoke strong, complex emotions, and are not initiated by either patients or their providers.

Indeed, although the majority of the public believes that these conversations are important, national surveys continue to find that a minority of people have had these conversations themselves or have completed advance directives.16,17 The present study findings among 1 health care company's workforce and their beneficiaries are consistent with public surveys, which was surprising given the working hypothesis that health care workers would have a higher ACP completion rate compared to the general population.

Rates of participation in the PH&S 2015–2016 health incentive program ACP option and survey responses suggest that employees of this health care provider organization are receptive to learning about ACP and feel that it is a healthy behavior worth encouraging. The level of participation in the PH&S 2015–2016 health incentive plan was relatively high and comparable to prior years, which focused on more traditional healthy lifestyle activities. For comparison, the following year (2016–2017), when the health incentive returned to more traditional foci of a health risk assessment or biometric health screen, the rates of participation were slightly higher with 45,903 (88%) of insured employees and 14,589 (78%) of covered spouses/ABRs completing a health incentive option. A review of internal data from Redbrick Health's client base of contracted employers who offered a 2016 personal health assessment incentive activity yielded an aggregate completion rate of 43% of total eligible individuals (47% of eligible employees, 34% of eligible spouses). In addition to the general acceptability of the topic and activity, the high value of the compensation offered – up to $700 per individual and $1400 per couple – likely contributed to this rate of participation. For context, a recent survey of American employers found that high-value incentives were associated with a 52% rate of participation.21 Of note, employees were asked to select from one of 2 health incentive options. Participation rates might increase further if the activity was a part of a points-based incentive system rather than requiring full participation.

The Triple Aim of better patient experience (quality and satisfaction), improved health of the population, and controlled health care costs has guided efforts to reform the US health care system.22 Several authors have called for adding the well-being of the clinical workforce to be an essential component of the “Quadruple Aim” of health system reform.23,24 A health plan that rewards individuals for healthy physical and emotional behaviors, including ACP, is a potentially effective way of aligning provider culture with the healthy behaviors the organization seeks to foster in the patient populations it serves.

There are several limitations to these findings. The PH&S 2015–2016 incentive plan ACP option did not specifically require individuals to complete an advance directive or attest to having a conversation with family or clinical provider. Additionally, protection of Personal Health Information and the design of this incentive program prevents calculation of a return on investment for this activity. It also remains unclear what, if any, concrete actions individuals will take as a result of the intervention. Repeating a comparable survey in future plan years may help evaluate the impact this activity had on employee behaviors, including the filing of a completed advance directive document in one's health record. Indeed, to address this, a follow-up ACP incentive activity has been planned for the PH&S 2017–2018 benefit cycle.

This plan involves employees and their spouses and other adult dependents of a single health care organization, which is faith-based and highlights its Catholic core values in recruiting and hiring employees. These characteristics of the corporate culture may increase the sense of trust that insured individuals have in their employer. It will be interesting to observe the rates of employee participation and expressed acceptance as similar incentive plans are offered by secular health care systems and non–health care corporations with different workforce compositions.

Conclusion

This program represents one of the first large-scale health system employer incentive plans aimed at increasing ACP as a healthy behavior within its workforce and as a means of fostering a culture of patient-centered, goal-aligned care. Early experience shows that the program was feasible and acceptable. Future surveys will be needed to assess whether rates of reported ACP conversations and advance directive completions change.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Yvonne Corbeil for assistance in revising data visualization.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Barnett J, Vornovitsky M. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2015. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willis Towers Watson. High-performance insights—best practices in Health Care. 2015 20th Annual Willis Towers Watson/National Business Group on Health Best Practices in Health Care Employer Survey. 2015. www.towerswatson.com/en-US/Insights/IC-Types/Survey-Research-Results/2015/11/full-report-2015-towers-watson-nbgh-best-practices-in-health-care-employer-survey Accessed January4, 2017

- 3.Stein AD, Shakour SK, Zuidema RA. Financial incentives, participation in employer-sponsored health promotion, and changes in employee health and productivity: HealthPlus Health Quotient Program. J Occup Environ Med 2000;42:1148–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattke S, Liu H, Caloyeras J, et al. Workplace wellness programs study: final report. Rand Health Q 2013;3:7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollitz K, Rae M. Workplace wellness programs characteristics and requirements. 2016. www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/workplace-wellness-programs-characteristics-and-requirements/ Accessed January3, 2017

- 6.Schmidt H, Voigt K, Wikler D. Carrots, sticks, and health care reform—problems with wellness incentives. N Engl J Med 2010;362:e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baicker K, Cutler D, Song Z. Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:304–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silveira MJ, Kim SYH, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1211–1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bischoff KE, Sudore R, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Smith AK. Advance care planning and the quality of end-of-life care in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:209–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiarchiaro J, Buddadhumaruk P, Arnold RM, White DB. Prior advance care planning is associated with less decisional conflict among surrogates for critically ill patients. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12:1528–1533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:480–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Health Care Decisions Day. www.nhdd.org/ Accessed November29, 2016

- 15.The Conversation Project. http://theconversationproject.org/ Accessed November29, 2016

- 16.The Conversation Project. New survey reveals ‘conversation disconnect’: 90 percent of Americans know they should have a conversation about what they want at the end of life, yet only 30 percent have done so. 2013. http://theconversationproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/TCP-Survey-Release_FINAL-9-18-13.pdf Accessed November7, 2016

- 17.California Health Care Foundation. Final chapter: Californians' attitudes and experiences with death and dying. 2012. www.chcf.org/publications/2012/02/final-chapter-death-dying Accessed November7, 2016

- 18.Pew Research Center. More older Americans are working, and working more, than they used to. 2016. www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/06/20/more-older-americans-are-working-and-working-more-than-they-used-to/ Accessed May6, 2017

- 19.Keehan SP, Stone DA, Poisal JA, et al. National health expenditure projections, 2016–25: price increases, aging push sector to 20 percent of economy. Health Aff 2017;36:553–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Claxton G, Rae M, Long M, Damico A, Whitmore H, Foster G. Health benefits in 2016: family premiums rose modestly, and offer rates remained stable. Health Aff 2016;35:1908–1917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batorsky B, Taylor E, Huang C, Liu H, Mattke S. Understanding the relationship between incentive design and participation in U.S. workplace wellness programs. Am J Health Promot 2016;30:198–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:759–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:573–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sikka R, Morath JM, Leape L. The quadruple aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:608–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]