Abstract

Objective

The Ways of Responding (WOR) instrument measures compensatory skills, a central construct in some theories of the mechanism of cognitive therapy for depression. However, the instrument is time-consuming and expensive to use in community settings, because it requires trained independent judges to rate subjects’ open-ended written responses to depressogenic scenarios. The present study evaluated the reliability and validity of a self-report version of the WOR in a community mental health sample with depressive symptoms (N = 467).

Method

Subjects completed the self-report version of the WOR (WOR-SR), a modified version of the original WOR, and other measures of depressive symptoms, dysfunctional cognitions, functioning, quality of life, and interpersonal problems at multiple time points.

Results

An exploratory factor analysis confirmed the two-factor structure of the WOR-SR. The positive and negative subscales both demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas = .91) and moderate convergent validity with other measures.

Conclusion

The WOR-SR is a reliable and valid measure of compensatory skills in patients receiving treatment for depression at community mental health centers.

Keywords: depression, ways of responding, compensatory skills, community mental health, reliability, validity

One of the central mechanisms of change in cognitive therapy (CT) for depression (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) is the acquisition of compensatory skills that allows patients to cope more adaptively with negative thoughts and stressful situations (Barber & DeRubeis, 1989, 2001). Compensatory strategies taught in cognitive therapy involve generating initial and then alternative explanations for distressing thoughts and events and creating plans to resolve stressful problems. Accordingly, the compensatory skills model of CT suggests that depressed patients improve by learning and enhancing cognitive skills that help curtail negative automatic thoughts and increase adaptive responses. The acquisition and improvement of compensatory skills in CT is also consistent with the role of cognitive reappraisal as an adaptive emotion regulation strategy theorized to be protective against psychopathology (Gross, 1988).

To assess the acquisition and development of compensatory skills, Barber and DeRubeis (1992) developed the Ways of Responding (WOR) instrument. The WOR consists of six mood induction scenarios followed by initial negative thoughts that might be automatically associated with each situation. Respondents are asked to imagine themselves in each scenario and describe their feelings, thoughts, and potential reactions in an open-ended, written format. Trained independent judges read these written answers and determine the number of positive and negative cognitive responses recorded for each scenario. The number of positive responses reflects the number of times a respondent uses an adaptive mode of responding taught and encouraged by cognitive therapists, whereas the number of negative responses represents the quantity of depressotypic reactions toward a given scenario. A WOR total score is created by subtracting the positive score from the negative score. The WOR has demonstrated good internal consistency, interrater reliability, construct validity, predictive validity, and convergent validity with other measures of mood and cognitions in both student and clinical samples (Barber & DeRubeis, 1992).

Several studies have used the WOR to examine the covariation between compensatory skills and depressive symptoms over the course of psychotherapy. In a study of patients receiving 12 weeks of CT as a treatment for depression, Barber and DeRubeis (2001) found not only a significant improvement in compensatory skills as measured by the WOR, but also covariation between the change in compensatory skills and change in depressive symptoms. Consistent with these findings, Adler, Strunk, and Fazio (2015) found that after 16 weeks of CT, patients displayed improvements in compensatory skills that were significantly related to reductions in depressive symptoms. In addition, even after controlling for post-treatment residual depressive symptoms, compensatory skills measured by the WOR significantly predicted a lower likelihood of relapse a year after CT treatment (Strunk, DeRubeis, Chiu, & Alvarez, 2007). Moreover, Connolly Gibbons et al. (2009) demonstrated that in both cognitive and dynamic therapies, change in the WOR total score (reflecting an improvement in compensatory skills) covaried with symptom course during treatment and was also predictive of subsequent symptom course, even after accounting for total symptom change from pre- to post-treatment. Although prediction of subsequent symptom course, controlling for prior change, comes closer to pointing to a causal role for compensatory skills in relation to reduction of depressive symptoms, it should be noted that other variables may still be confounds of the reported associations of compensatory skills with change in depression.

With several studies consistently demonstrating that improvement in compensatory skills is associated with improvement in depressive symptoms, it has become important to measure this crucial construct across diverse settings. The WOR, however, has several limitations to its utility. In particular, because the WOR requires trained judges to rate written responses, its utility is restricted in settings where time, education, and budget are limited. Previous efforts have been made to develop and validate self-report measures of patients’ understanding and use of cognitive skills taught in CT (Jarrett, Vittengl, Clark, & Thase, 2011; Strunk, Hollars, Adler, Goldstein, & Braun, 2014). Mid-treatment scores on the eight-item Skills of Cognitive Therapy (SoCT) questionnaire developed by Jarrett et al. (2011) have demonstrated good predictive validity with odds of response to CT. Strunk et al.’s (2014) Competencies of Cognitive Therapy Scale (CCTS), a 29-item self-report measure of CT skills, has shown good convergent validity with the WOR over the course of 16 weeks of CT, even after controlling for depressive symptoms. In addition, greater change in CT skills as measured by the CCTS was significantly associated with greater reduction of depressive symptoms.

Despite the strong psychometric properties of these measures, we identified a need for a self-report measure of compensatory skills consistent with the two-factor structure of the original WOR, which separately assesses negative depressotypic reactions and positive coping responses. Using the original WOR, Barber and DeRubeis (2001) reported that change in the positive score, but not the negative score, was significantly associated with change in depression for patients in CT. No other studies have examined both the positive and negative WOR scores in relation to outcome. In contrast to the WOR, both the SoCT and CCTS were designed to measure only the utilization of positive coping skills. Our goal was to develop an alternative to the original, two-factor WOR that could be easily administered and scored in a wide range of settings and allowed for examining the role of both positive and negative compensatory skills in the process of change. Drawing upon examples of negative and positive responses included in the scoring manual for the original WOR, we compiled a list of self-report items assessing the degree to which a respondent engaged negative depressotypic thinking and positive coping strategies in response to stressful mood-induction scenarios. These items were used to create the initial version of the WOR self-report (WOR-SR).

In the current study, we present the development of the WOR-SR and report on its reliability, factor analysis, and validity in a community mental health sample. The WOR-SR was administered at multiple time points to patients seeking treatment for depression and referred for participation in a large comparative effectiveness trial of cognitive and dynamic therapies for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) in a community mental health setting (Connolly Gibbons, Mack, Lee, et al., 2014). We hypothesized that the WOR-SR would be moderately associated with the original WOR, which we modified slightly to be more applicable to a community setting, as well as with other measures of depressive symptoms, dysfunctional cognitions, general functioning, quality of life, and interpersonal problems.

Method

Participants

The present sample consisted of 467 outpatients seeking treatment for depression and referred for participation in a comparative effectiveness trial of cognitive and supportive-expressive dynamic therapies for MDD in a large community mental health center in Pennsylvania (Connolly Gibbons, Mack, Lee, et al., 2014). Patients with a score of 11 or above on the Quick Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS; Rush et al., 2003) at intake were referred to the study. More information regarding recruitment and enrollment is provided by Connolly Gibbons, Mack, Lee, et al. (2014). For analyses, this clinical sample was divided into a derivation sample, consisting of the first 100 cases (n = 148) that completed both the WOR-SR and a modified version of the original WOR, and a validation sample consisting of the 319 subsequent cases.

The study sample was predominantly female (73.7%) and 50.3% Caucasian, with an average age of 36. The highest level of education reported by the majority of participants (61.5%) was a high school diploma or less. About half of the sample was unemployed (49.3%) at baseline (see Table 1). The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board approved this study, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Clinical Sample

| Characteristics | Sample N = 467 |

|---|---|

| Gender, (Female), N(%) | 344(73.7) |

| Age, years, M(SD) | 36.63(12.07) |

| Marital Status, N(%) | |

| Single | 246(52.7) |

| Married/Cohabitating | 92(19.7) |

| Separated/Divorced | 115(24.6) |

| Widowed | 14(3.0) |

| Ethnicity, (Hispanic), N(%) | 18(3.9) |

| Race, N(%) | |

| Black/African-American | 194(41.5) |

| White/Caucasian | 235(50.3) |

| Other | 38(8.2) |

| Employment Status, N(%) | |

| Full-Time | 30(6.4) |

| Part-Time | 45(9.6) |

| Stay at Home Parent | 36(7.7) |

| Unemployed | 230(49.3) |

| Student | 31(6.7) |

| Disabled | 95(20.3) |

| Education Level, N(%) | |

| Less than High School | 94(20.2) |

| High School Diploma/GED | 193(41.3) |

| Some College | 151(32.3) |

| College Graduate | 18(3.9) |

| Post-graduate or Professional degree | 11(2.4) |

Procedures

Participants completed a demographic questionnaire, the WOR-SR, a modified version of the original WOR, the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D; Hamilton, 1960), the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS; Weissman & Beck, 1978), the Psychological Distance Scaling Task (PDST; Dozois & Dobson, 2001a, 2001b), the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form (SF-36; Ware & Sherbourne, 1992), the Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI; Frisch, Cornell, Villanueva, & Retzlaff, 1992), and the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-48 (IIP-48; Gude, Moum, Kaldestad, & Friis, 2000).

Measures were completed at the baseline assessment and months 1, 2, and 5 following baseline. Because participants were initially recruited for exhibiting moderate to severe depressive symptoms (i.e., QIDS score above 11), the range of depression severity at baseline assessment was relatively restricted in this sample. Our goal was to evaluate the performance of the WOR-SR across the full range of depressive symptoms that would be present in a typical clinical population. Therefore, we analyzed values of each measure from the last assessment point at which each participant completed the WOR-SR (i.e., endpoint scores). At these last observation assessments, the standard deviation of the BDI-II, for example, was 25% higher than at baseline. The number of participants who completed each measure at the last observation of the WOR-SR varies due to missing data.

Measures

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)

The BDI-II (Beck et al., 1996) is a reliable and valid 21-item self-report questionnaire widely used to assess the severity of depression symptoms over the preceding two weeks. This measure demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the current study sample at the endpoint assessment (n = 435, Cronbach’s α = .94).

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D)

The HAM-D (Hamilton, 1960) is one of the most commonly used, reliable questionnaires for rating the severity of typical depressive symptoms. In the present study, a trained diagnostician administered the 24-item version of the HAM-D, using the Structured Interview Guide to strengthen reliability (Williams, 1988). Satisfactory internal consistency of the first 17 items of this measure was found in the present study sample at the endpoint assessment (n = 462, Cronbach’s α = .76).

Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS)

The DAS (Weissman & Beck, 1978) is a 40-item self-report inventory designed to measure cognitive distortions that are thought to predispose individuals to depression. Higher scores indicate greater number and severity of dysfunctional beliefs. This instrument exhibited excellent internal consistency in the present study sample at the endpoint assessment (n = 430, Cronbach’s α = .94).

Psychological Distance Scaling Task (PDST)

The PDST (Dozois & Dobson, 2001a, 2001b) is a computerized cognitive task developed to measure underlying depressogenic schemas. Subjects are presented with a square grid divided into quadrants by a horizontal line, with the anchors Not at all like me on the left and Very much like me on the right, and a vertical line, with the anchors Very positive on the top and Very negative on the bottom. Subjects are instructed to rate 80 randomly ordered positive schematic (achievement positive, interpersonal positive) or negative schematic (achievement negative, interpersonal negative) adjectives.

The rating consists of moving the mouse to a location on the grid that best reflects the degree of self-relevance and valence of each stimulus. The psychometric properties of this cognitive task have been tested and validated in a number of studies (Dozois & Dobson, 2001; Dozois & Frewen, 2006; Dozois, 2007; Dozois et al., 2009). We used here a modified version of the PDST designed for participants with low education levels (Diehl et al., in press). As has been done in previous studies involving the PDST (Dozois, 2007), we used log-transformed scores for each PDST subscale to account for non-normal distributions of the scores.

The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form (SF-36)

The SF-36 (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992) is a commonly administered self-report measure of general health status and quality of life. It consists of eight multi-item scales (Physical Functioning, Role Limitations due to Physical Health Problems, Role Limitations due to Emotional Problems, Bodily Pain, General Health Perceptions, Vitality, Social Functioning, and Mental Health), which are standardized and weighted into two summary scales, the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS). Good internal consistency has been reported for all eight scales (McHorney, War, Lu, & Sherbourne, 1994), and a factor analysis has confirmed the two-factor structure of this measure (McHorney, Ware, Raczek, 1993). The PCS and MCS have also demonstrated good discriminant validity (McHorney et al., 1993; Ware et al., 1995).

Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI)

The QOLI (Frisch et al., 1992) is a 32-item self-report measure of overall satisfaction with aspects of life deemed important by the respondent. The measure has demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α’s = .77–.89) across both clinical and non-clinical samples, good test-retest reliability (r = .80–.91), and good convergent validity with seven other measures of well-being (Frisch et al., 1992). We found that the internal consistency of this instrument was adequate in the present sample at the endpoint assessment (n = 438, Cronbach’s α = .88).

The Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-48 (IIP-48)

The IIP-48 (Gude et al., 2000) is a 48-item self-report measure developed to identify sources of interpersonal distress. This measure derives from a principal components analysis of the original 127-item IIP (Horowitz, Rosenberg, Baer, Ureño, & Villaseñor, 1988). The IIP-48 measures three factors: Assertiveness, Sociability, and Interpersonal Sensitivity. All three subscales have demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .69 to .80), and there is significant convergence between the 48-item IIP and the original 127-item IIP (Gude et al., 2000). In the present study, we found excellent internal consistency for this instrument at the endpoint assessment (n = 382, Cronbach’s α = .91).

Ways of Responding (WOR)

We used a slightly modified version of the original WOR developed by Barber and DeRubeis (1992). The WOR consists of six written stressful scenarios that are designed to be mild mood induction prompts. For example, one scenario states: “Imagine that you’ve been applying for jobs, and you just received a phone call saying the latest position you applied for has been filled by someone else. This is the third time this has happened to you. The first thought that pops into your head is, ‘Will I ever get a job? There just doesn’t seem to be any point in applying.’ The respondent is then asked to rate (on a 0–100 scale) how vividly they are imagining this situation, as well as the intensity of their mood. Respondents are also asked to describe their mood in writing and to note any further thoughts that they would have in this scenario. The written responses are rated by three independent judges who are trained with the WOR Rater’s Guide (Barber & DeRubeis, 1992). The first judge is responsible for determining the number of individual thought units within a response and then coding each unit into one of 25 categories representing negative (e.g., leaving or ignoring the situation, focusing blame on the self, acting out, coming up with a general and vague solution or plan, thinking negatively) or positive (e.g., planning to improve, recruiting help or accepting help, expressing a hopeful attitude towards the situation, planning to test a belief or idea, recruiting help or accepting help, looking for or finding a positive feature) mood and behavior. The second judge receives the responses that have already been parsed into thought units by the first rater and independently categorizes each unit as positive or negative. The third judge resolves any discrepancies between the first two judges’ decisions. WOR subscale scores are calculated by separately averaging the number of positive responses and the number of negative responses across the six scenarios. A total score can be calculated as the difference between the positive and negative scores.

In the current study, we made minor modifications to the WOR to make it more appropriate for a community mental health setting. First, we changed several words in order to reduce the reading level and make the wording more culturally appropriate. In addition, we replaced one of the six original scenarios. One scenario in the original WOR was more appropriate for students (“You’ve been sitting at your desk trying to write an essay for two hours and haven’t been able to put two sentences together.”). We replaced this scenario with the following: “Imagine that you’re sick and you need to go to the doctor. You call everyone you know, but no one will give you a ride. The first thing that pops into your head is, “I’m on my own. No one is ever going to be there for me.” A preliminary study using this slightly modified WOR in a student sample (N = 99) found adequate inter-judge reliability [intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (3, 2) ranging from .74 to .85] and good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of .80 and .82 for the positive and negative subscales, respectively) (Connolly Gibbons, Lee, Mack, et al., 2014). The modified WOR was administered to patients in the current study and rated by three independent judges. We used a balanced incomplete block design in which two graduate student judges independently rated each response for positive compensatory strategies and negative depressotypic reactions, and a third judge resolved discrepancies between the first two judges. To avoid rater drift, the judges participated in monthly recalibration sessions that were held via conference call. There was good inter-judge agreement on both the positive [ICC (2, 2) = 0.92] and negative [ICC (2, 2) = 0.94] subscales of the WOR. We found adequate internal consistency for both the positive (n = 317, Cronbach’s α = .83) and negative (n = 317, Cronbach’s α = .81) subscales at the endpoint assessment.

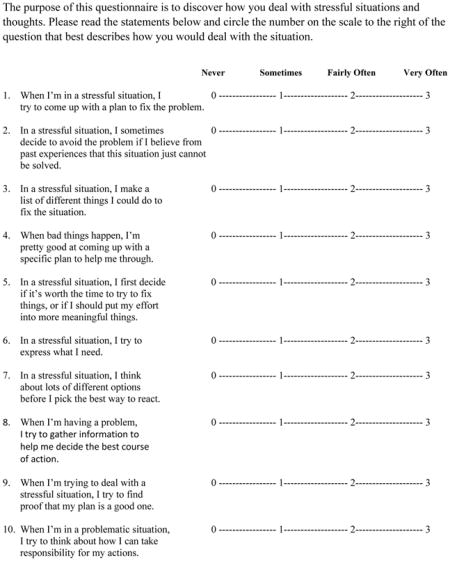

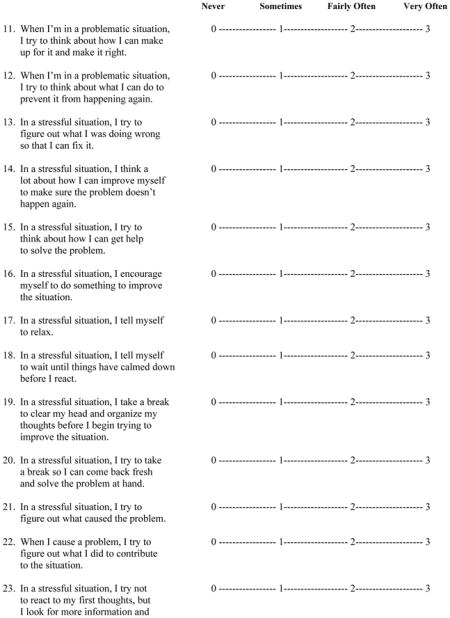

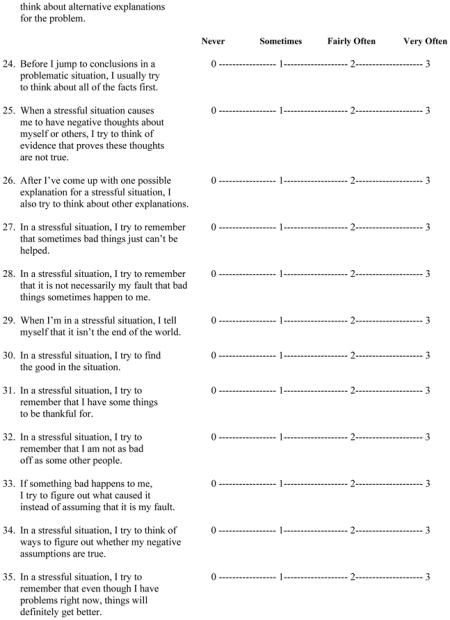

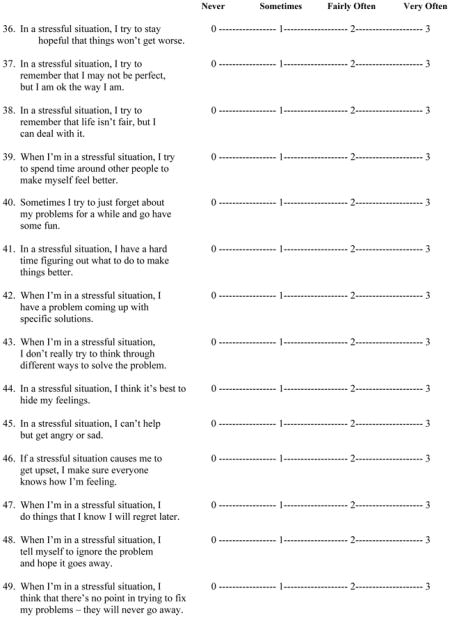

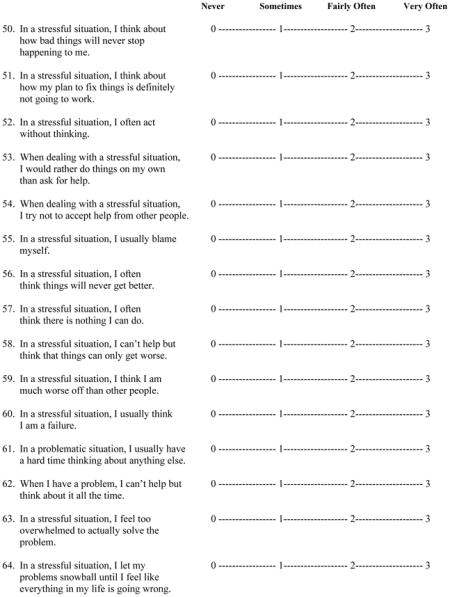

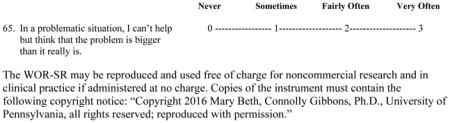

Ways of Responding-Self-Report (WOR-SR)

As described above, we developed a self-report version of the original WOR in order to measure compensatory skills without the use of written responses and trained raters (see Appendix). On a 4-point scale (0 = Never to 3 = Very Often), participants rated items representing positive compensatory strategies (e.g., “In a stressful situation, I try to come up with a plan to fix the problem”) and negative, depressotypic reactions (e.g., “In a stressful situation, I usually think that I am a failure”). An average positive score and average negative score were calculated across the respective positive and negative items.

The initial WOR-SR item pool consisted of 65 items, with 39 of those representing potential positive compensatory strategies and 26 representing negative depressotypic reactions. The positive and negative items were drawn from the examples of positive and negative responses presented in the scoring manual for the original WOR (Barber & DeRubeis, 1992). The examples in the WOR manual were created based on the literature on coping and the types of skills taught by cognitive therapists, as described in the manual for cognitive therapy (Beck et al., 1979).

The WOR-SR item pool was first examined in a preliminary study using a student sample (Connolly Gibbons, Lee, Mack, et al., 2014). In this student sample (N = 99), Cronbach’s alpha for the positive and negative subscales including all items were .94 and .87, respectively. However, one positive item and three negative items demonstrated low (Cronbach’s alpha < .20) item-total correlations. We deleted those four items and retained the remaining items for analyses in the current community mental health sample in order to derive the final scales.

Results

Final Item Selection from Derivation Sample

Because we developed the WOR-SR as an alternative to the original WOR, our goal for item selection was to choose items that were most highly related to scores on the original WOR among patients with depressive symptoms. To address the relation between WOR-SR items and the original WOR, we set aside a derivation sample (first 100 patients who completed both the WOR-SR and the modified WOR) from the current study and examined correlations between the WOR-SR items and the two subscales of the WOR. To retain a reasonable number of items for the positive WOR-SR scale, we used a cutoff score of .20 for the correlation between WOR-SR positive items and the WOR positive subscale score. We were able to obtain an adequate number of WOR-SR negative items by using a cutoff score of .30 for the correlation with the WOR negative subscale score. A further requirement for item selection was that the WOR-SR positive items had to be more highly correlated with the WOR positive subscale than with the WOR negative subscale, and vice versa for the WOR-SR negative items. The selected WOR-SR items (14 positive and 17 negative) are presented in Table 2. The correlations between the 14 positive items and the WOR positive subscale range from .21 to .38, while the correlations between the 17 negative items and the WOR negative subscale range from .31 to .45. All further analyses were conducted within the validation sample.

Table 2.

Pattern Matrix from Exploratory Factor Analysis in Validation Clinical Sample (n = 319)

| 1: Negative Factor | 2: Positive Factor | |

|---|---|---|

| WOR-SR Positive Items | ||

| 1:When I’m in a stressful situation, I try to come up with a plan to fix the problem | .018 | .654 |

| 3:In a stressful situation, I make a list of different things I could do to fix the situation | −.139 | .487 |

| 4:When bad things happen, I’m pretty good at coming up with a specific plan to help me through | −.146 | .616 |

| 7:In a stressful situation, I try to express what I need | −.112 | .661 |

| 8:When I’m having a problem, I try to gather information to help me decide the best course of action | −.075 | .700 |

| 10:When I’m in a problematic situation, I try to think about how I can take responsibility for my actions | .051 | .681 |

| 11:When I’m in a problematic situation, I try to think about how I can make up for it and make it right | .104 | .734 |

| 12:When I’m in a problematic situation, I try to think about what I can do to prevent it from happening again | .057 | .766 |

| 13:In a stressful situation, I try to figure out what I was doing wrong so that I can fix it | .076 | .732 |

| 16:In a stressful situation, I encourage myself to do something to improve the situation | −.017 | .777 |

| 21:In a stressful situation, I try to figure out what caused the problem | .062 | .742 |

| 22:When I cause a problem, I try to figure out what I did to contribute to the situation | .147 | .660 |

| 32:In a stressful situation, I try to remember that I am not as bad off as some other people | −.020 | .502 |

| 34:In a stressful situation, I try to think of ways to figure out whether my negative assumptions are true | −.022 | .522 |

| WOR-SR Negative Items | ||

| 41:In a stressful situation, I have a hard time figuring out what to do to make things better | .478 | .208 |

| 44:In a stressful situation, I think it’s best to hide my feelings | .524 | .048 |

| 45:In a stressful situation, I can’t help but get angry or sad | .615 | −.036 |

| 47:When I’m in a stressful situation, I do things that I know I will regret later | .507 | .036 |

| 50:In a stressful situation, I think about how bad things will never stop happening to me | .726 | .107 |

| 51:In a stressful situation, I think about how my plan to fix things is definitely not going to work | .617 | −.007 |

| 52:In a stressful situation, I often act without thinking | .595 | −.048 |

| 53:When dealing with a stressful situation, I would rather do things on my own than ask for help | .561 | .110 |

| 54:When dealing with a stressful situation, I try not to accept help from other people | .452 | .006 |

| 55:In a stressful situation, I usually blame myself | .645 | .001 |

| 59:In a stressful situation, I think I am much worse off than other people | .690 | −.043 |

| 60:In a stressful situation, I usually think I am a failure | .732 | −.013 |

| 61:In a problematic situation, I usually have a hard time thinking about anything else | .646 | −.001 |

| 62:When I have a problem, I can’t help but think about it all the time | .713 | .031 |

| 63:In a stressful situation, I feel too overwhelmed to actually solve the problem | .670 | −.104 |

| 64:In a stressful situation, I let my problems snowball until I feel like everything in my life is going wrong | .683 | −.176 |

| 65:In a problematic situation, I can’t help but think that the problem is bigger than it really is | .715 | −.070 |

Note. WOR-SR, Ways of Responding Self-Report Version.

Item-Total Correlations and Internal Reliability

Within the validation sample (n = 319), corrected item-total correlations for the 14 positive items ranged from .47 to .71, and those of the 17 negative items ranged from .43 to .69. The positive and negative subscales of the WOR-SR demonstrated excellent internal consistency (both Cronbach’s alphas = .91).

Exploratory Factor Analysis

To confirm that the positive WOR-SR items were associated primarily with the positive WOR-SR subscale and the negative items with the negative subscale, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis with promax rotation within the validation sample. Eigenvalues (factor 1: 7.78; factor 2: 6.46) showed a clear break after two factors. The rotated pattern matrix revealed that all of the positive items except for one loaded greater than .50 on the positive factor (factor 1), and all of the negative items except for two loaded greater than .50 on the negative factor (factor 2; see Table 2). None of the positive items loaded highly on the negative factor, and none of the negative items loaded highly on the positive factor.

Convergent Validity

Descriptive statistics for the convergent validity measures within the validation sample are presented in Table 3. Depressive symptoms in the study sample, as measured by the BDI-II and HAM-D, were moderate to severe on average.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics of Convergent Validity Measures in Validation Clinical Sample (n = 319)

| Measure | M | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| WOR-SR Subscales | |||

| Positive | 1.43 | .62 | 319 |

| Negative | 1.54 | .61 | 319 |

| WOR Subscales | |||

| Positive | 1.53 | .85 | 217 |

| Negative | 1.20 | 1.00 | 217 |

| BDI-II | 30.3 | 12.5 | 273 |

| HAM-D | 17.1 | 7.0 | 315 |

| DAS | 139.0 | 38.5 | 317 |

| PDST Subscales | |||

| Interpersonal positive | 1.19 | .30 | 255 |

| Interpersonal negative | 1.57 | .37 | 249 |

| Achievement positive | 1.28 | .36 | 238 |

| Achievement negative | 1.50 | .38 | 234 |

| SF-36 MCS | 28.0 | 11.0 | 315 |

| QOLI | −.76 | 2.15 | 319 |

| IIP-48 Total | 1.57 | .65 | 315 |

Note. WOR-SR, Ways of Responding Self-Report Version; WOR, Ways of Responding (modified original measure); BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; HAM-D, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; DAS, Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale; PDST, Psychological Distance Scaling Task; SF-36 MCS, The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Mental Component Score; QOLI, Quality of Life Inventory; IIP-48 Total, Total Score of the 48-Item Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, Sample sizes vary due to missing data.

There was moderate convergence between the modified version of the original WOR and the WOR-SR (r = .31, p < .001 for positive scales; r = .43, p < .001 for negative scales). The correlations between the WOR-SR and other validity measures are presented in Table 4. The WOR-SR demonstrated moderate convergent validity with both measures of depressive symptoms, with the highest correlation between the WOR-SR negative subscale and the BDI-II (r = .53, p < .001). In general, the correlations of the WOR-SR subscales with the validity measures were numerically as large if not larger than the correlations of the modified version of the original WOR with these same validity measures. Tests of the difference between dependent correlations revealed that the correlation between the WOR-SR negative subscale and the BDI-II (r = .53) was significantly (z = 2.98, N = 173, p = .003) larger than that between the WOR negative subscale and BDI-II (r =.32). None of the other correlations with validity measures was significantly different for the WOR-SR compared to the WOR.

Table 4.

Pearson Correlations of the WOR and WOR-SR with Other Measures

| WOR Subscales

|

WOR-SR Subscales

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive r |

Negative r |

Positive r |

Negative r |

|

| BDI-II | −.19* | .32*** | −.16** | .53*** |

| HAM-D | −.17* | .21** | −.20*** | .33*** |

| DAS | −.39*** | .46*** | −.25*** | .48*** |

| PDST Subscales | ||||

| Interpersonal Positive | −.02 | .11 | −.19** | .18** |

| Interpersonal Negative | .22** | −.19* | .16* | −.20** |

| Achievement Positive | −.17* | .28** | −.29*** | .18** |

| Achievement Negative | .17* | −.18* | .24*** | −.22** |

| SF-36 MCS | .25*** | −.38*** | .20*** | −.46*** |

| QOLI | .21** | −.24*** | .18** | −.36*** |

| IIP-48 Total | −.30*** | .38*** | −.23*** | .49*** |

Note. WOR-SR, Ways of Responding Self-Report Version; WOR, Ways of Responding (modified original measure); BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; HAM-D, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; DAS, Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale; PDST, Psychological Distance Scaling Task; SF-36 MCS, The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Mental Component Score; QOLI, Quality of Life Inventory; IIP-48 Total, Total Score of the 48-Item Inventory of Interpersonal Problems,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

To ascertain whether the convergent validity between the WOR-SR and WOR was due to the fact that both were simply measuring depressive symptoms, we calculated partial correlations between the WOR-SR and WOR, controlling for BDI-II scores. The partial correlations between the WOR-SR positive and WOR positive subscales, as well as those between the WOR-SR negative and WOR negative subscales, were only slightly reduced after controlling for the BDI-II (rp = .28, p < .001 and rp = .40, p < .001, respectively).

Discussion

Several previous studies have validated the original WOR developed by Barber and DeRubeis (1992) as a reliable measure of the acquisition and use of compensatory skills that is sensitive to change over the course of psychotherapy (Barber & DeRubeis, 2001; see also Adler et al., 2015; Connolly Gibbons, et al., 2009). Nonetheless, there are significant limitations to its application in community mental health and other settings due to its open-ended format and use of trained judges. To increase the utility of the WOR, we developed a new self-report version (WOR-SR).

The selected positive and negative items of the WOR-SR demonstrated excellent internal consistency (both Cronbach’s alphas = .91), indicating that the items selected for each subscale reliably measure a single construct. An exploratory factor analysis using promax rotation further confirmed the two-factor structure of the WOR-SR, suggesting that the positive items were associated primarily with the positive compensatory skills scale and the negative items with the negative depressotypic reactions scale, as intended. In addition, the WOR-SR positive and negative subscales were found to be moderately associated with the corresponding scales from the original WOR. These correlations were largely unaffected when depressive symptoms were partialled out, indicating that the WOR-SR captures compensatory skills and is not simply a measure of depressive symptoms. Though the WOR-SR and the modified version of the original WOR were only moderately correlated with each other, it is not uncommon for scales using different methodologies (e.g., self-report versus relying on judges) to only show modest convergence. For example, meta-analytic results comparing self-ratings with other ratings of Big Five personality dimensions reveal correlations in the .39 to .51 range across the five dimensions, even after correcting for test-retest reliability of the measures, which was not done in the present study (Connolly & Ones, 2010). It is to be expected that convergence of a self-report measure with another method that involves rating brief written responses (as is done in the original WOR) is even lower, given that limited information is contained in these written responses. However, in the case of the similar Strunk et al. (2014) CCTS measure, a .54 correlation is reported between patient and therapist versions of the scale. Whether the lower correlations between the WOR-SR and WOR found here are a function of the limitations of the WOR (e.g., relying on participants’ degree of verbal production in response to the prompts), lower validity of the WOR-SR, or other differences between the studies (such as the use of therapists’ versus judges’ ratings) should be addressed in future research. In examining the relation of the CCTS to the WOR, Strunk et al. (2014) report an r of .37, similar to the correlations of .31 (positive subscales) and .43 (negative subscales) found here. These correlations, however, may not be directly comparable, because Strunk et al. (2014) used a global WOR quality rating rather than the separate positive and negative WOR subscales used in the current study.

In our clinical sample of patients with depressive symptoms, both the WOR-SR and the modified version of the WOR demonstrated moderate convergence with the two measures of depressive symptoms, the BDI-II and HAM-D. The convergent validity of the WOR with the BDI-II has been demonstrated in previous studies (Barber & DeRubeis, 1992, 2001; Connolly Gibbons, et al., 2009). The significant correlation between the WOR-SR and HAM-D indicates that the association between compensatory skills and depressive symptoms is not simply due to method variance. The moderate convergence between the DAS and each of the two WORs (WOR-SR and the modified version of the WOR) is also consistent with previous research demonstrating convergent validity between the original WOR and the DAS (Barber & DeRubeis, 2001; Adler et al., 2015).

Previous research has not examined the relation of a measure of compensatory skills to measures of quality of life or interpersonal problems. The moderate convergence between the two WORs and both quality of life measures suggests that engaging in more negative depressotypic reactions is associated with poorer self-perceived health and functioning in daily life. Future studies should examine whether changes in compensatory skills, as measured by the WOR-SR, contribute to improved daily functioning or self-perceptions of mental and physical health. The significant moderate correlation between the IIP-48 and each version of the WOR also indicates that greater engagement in negative depressotypic reactions is associated with greater interpersonal distress. The relation between change in compensatory skills, as measured by the WOR-SR, and reduction of interpersonal problems should be further examined.

Despite the significant correlations between the WOR-SR subscales and the PDST subscales, the modified version of the original WOR did not consistently demonstrate convergence with the PDST. Specifically, there was no significant association between the modified version of the original WOR and the interpersonal positive subscale of the PDST. In addition, the size of the correlations between the two WOR measures and the PDST were relatively small. This suggests that the cognitive processes measured by the PDST (i.e., those involved in the consolidation of self-referent content within cognitive schema) overlap only slightly with the cognitive processes that underlie compensatory skill acquisition. Thus, it may be that some of the cognitive processes that contribute to depression are relatively independent of each other. Alternatively, some cognitive processes may contribute to a depressive episode, while others are a consequence of depression.

In no cases were the validity coefficients for the WOR-SR significantly lower than those found for the original (modified) WOR. In fact, one validity coefficient (with the BDI-II) was significantly higher for the WOR-SR negative subscale compared to the WOR negative subscale. Thus, it appears that there is no loss of validity, at least among the measures tested here, for the WOR-SR relative to the WOR. This is an important finding in support of the potential use of the WOR-SR by investigators who prefer to avoid the time and expense that is associated with scoring the WOR.

Despite the evidence presented here on the factor structure, internal reliability, and concurrent validity of the WOR-SR, further work is needed to fully understand the constructs measured and their utility for understanding the process of change in CT. In measuring negative compensatory skills, there is ambiguity concerning what is an actual negative coping action that might contribute to further depression, and what is simply a cognitive reaction to stress (an absence of a negative compensatory skill). Items in our WOR-SR negative scale likely reflect both of these processes to some degree. Whether this is a problem with lack of clarity in constructs such as “compensatory skills” and “cognitive reactivity” or a problem with the original Barber and DeRubeis (1992) WOR list of compensatory skills is not known. Further research examining the positive and negative scales of the original WOR and/or WOR-SR in relation to other measures, and in particular to the outcome of cognitive and other therapies for depression, will help resolve these issues.

In conclusion, our results suggest that the new self-report version of the WOR introduced here is a reliable and valid measure of compensatory skills among patients receiving treatment for depression at community mental health centers. Considering the time and financial burden associated with evaluating compensatory skills via written responses, the WOR-SR may be an efficient and valid alternative to the standard version of the WOR. Ongoing studies will examine the WOR-SR as a potential mediator of change in depressive symptoms over the course of cognitive therapy for depression.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01 HS018440) and a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH092363). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the National Institute of Mental Health.

Appendix. WAYS OF RESPONDING QUESTIONNAIRE - SELF REPORT VERSION

References

- Adler AD, Strunk DR, Fazio RH. What Changes in Cognitive Therapy for Depression? An Examination of Cognitive Therapy Skills and Maladaptive Beliefs. Behavior Therapy. 2015;46:96–109. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber JP, DeRubeis RJ. On second thought: Where the action is in cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive therapy and research. 1989;13:441–457. doi: 10.1007/BF01173905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barber JP, DeRubeis RJ. The ways of responding: A scale to assess compensatory skills taught in cognitive therapy. Behavioral Assessment. 1992;14:93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Barber JP, DeRubeis RJ. Change in Compensatory Skills in Cognitive Therapy for Depression. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research. 2001;10:8–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly BS, Ones DS. Another perspective on personality: meta-analytic integration of observers’ accuracy and predictive validity. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:1092–1122. doi: 10.1037/a0021212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly Gibbons MB, Crits-Christoph P, Barber JP, Stirman SW, Gallop R, Goldstein LA, … Ring-Kurtz S. Unique and Common Mechanisms of Change across Cognitive and Dynamic Psychotherapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:801–813. doi: 10.1037/a0016596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly Gibbons MB, Lee JK, Mack RA, Markell HM, Crits-Chrisoph P. The reliability and validity of community and self-report version of the Ways of Responding Questionnaire. Poster presented at the 45th annual meeting of the Society for Psychotherapy Research; Copenhagen, Denmark. 2014.2014. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- Connolly Gibbons MB, Mack R, Lee J, Gallop R, Thompson D, Burock D, Crits-Christoph P. Comparative effectiveness of cognitive and dynamic therapies for major depressive disorder in a community mental health setting: study protocol for a randomized non-inferiority trial. BMC Psychology. 2014;2:47. doi: 10.1186/s40359-014-0047-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl CK, Yin S, Markell HM, Gallop R, Connolly Gibbons MB, Crits-Christoph P. The Measurement of Cognitive Schemas: Validation of the Psychological Distance Scaling Task in a Community Mental Health Sample. doi: 10.1521/ijct_2016_09_18. in press. Retrieved from http://ijct.msubmit.net/ijct_files/2016/06/03/00000204/03/204_3_art_file_1592_587j1c.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dozois DJA, Dobson KS. Information processing and cognitive organization in unipolar depression: Specificity and comorbidity issues. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:236–246. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJA, Frewen PA. Specificity of cognitive structure in depression and social phobia: A comparison of interpersonal and achievement content. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;90:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJA. Stability of negative self-structures: A longitudinal comparison of depressed, remitted, and nonpsychiatric controls. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;63:319–338. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJA, Bieling PJ, Patelis-Siotis I, Hoar L, Chudzik S, McCabe K, Westra HA. Changes in self-schema structure in cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:1078–1088. doi: 10.1037/a0016886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1997. Clinical Version. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch MB, Cornell J, Villanueva M, Retzlaff PJ. Clinical validation of the Quality of Life Inventory. A measure of life satisfaction for use in treatment planning and outcome assessment. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:92–101. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.92. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, DeLongis A. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:571–579. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Review of General Psychology. 1998;2:271–299. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gude T, Moum T, Kaldestad E, Friis S. Inventory of Interpersonal Problems: A three-dimensional balanced and scalable 48-item version. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2000;74:296–310. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7402_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LM, Rosenberg SE, Baer BA, Ureño G, Villaseñor VS. Inventory of interpersonal problems: psychometric properties and clinical applications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:885–892. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett RB, Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Thase ME. Skills of Cognitive Therapy (SoCT): A New Measure of Patients’ Comprehension and Use. Psychological Assessment. 2011;23:578–586. doi: 10.1037/a0022485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Co; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical Care. 1993;31:247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Lu JR, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Medical care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, … Keller MB. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:573–583. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strunk DR, DeRubeis RJ, Chiu AW, Alvarez J. Patients’ competence in and performance of cognitive therapy skills: relation to the reduction of relapse risk following treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(4):523–530. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strunk DR, Hollars SN, Adler AD, Goldstein LA, Braun JD. Assessing patients’ cognitive therapy skills: Initial evaluation of the competencies of cognitive therapy scale. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2014;38:559–569. doi: 10.1007/s10608-014-9617-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30:473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr , Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, McHorney CA, Rogers WH, Raczek A. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Medical Care. 1995;33:AS264–AS279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JB. A structured interview guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:742–747. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800320058007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman AN, Beck AT. Development and validation of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale: A Preliminary Investigation. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. 1978. Mar, [Google Scholar]