Abstract

Underlying preferences are often considered to be persistent, and are important inputs into economic models. We first conduct an extensive review of the disparate literature studying the stability of preferences measured in experiments. Then, we test the stability of individuals’ choices in panel data from rural Paraguay over almost a decade. Answers to social preference survey questions are quite stable. Experimental measures of risk, time, and social preferences do not exhibit much stability. Correlations between experimental measures of risk aversion are a more precisely estimated zero, whereas correlations for time and social preferences are larger and noisier. We also find no systematic evidence that real world shocks influence play in games. We suggest that in a developing country context researchers should explore designing simpler experiments and including survey questions in addition to experiments to measure preferences.

1 Introduction

Time, risk, and social preference parameters are crucial inputs into many economic models. They have important impacts on outcomes in models of technology adoption, migration, savings, and risk-sharing among others. Over the past decades, experimental economists have worked on perfecting methods for measuring these parameters. Preferences are assumed constant by theory, so the experiment and survey-based constructs which purport to measure them should also remain constant. If preferences do vary over time, theory would suggest that this is due to some shock in the environment the individuals are facing (e.g., a monetary windfall or a recently experienced theft).

We study the stability over time of risk and time preferences as measured by experiments, and of social preferences as measured by both survey questions and experiments. We also study whether these measures are affected by real world shocks or experiences in experiments in previous years. Because the literature on this topic is spread across many journals in many different disciplines including economics, psychology, management, and marketing, our first contribution is an extensive cross-disciplinary review of the literature regarding the stability of experimentally-measured preferences over time. Most of the existing literature is focused on developed countries and more educated populations, though that emphasis has been changing more recently. We compile the correlations of preferences over time found in each paper, which can serve as a baseline to compare the correlations found in our own data and those found in future studies.

Next, we make use of a unique dataset which follows households in rural Paraguay, running surveys and experiments with them in 2002, 2007, 2009, and 2010. This data contains experimental measures of social, risk, and time preferences as well as survey measures of social preferences. Our contribution compared to the previous work is that we look at all three types of preferences,1 over relatively long periods of time, and with a relatively large and diverse population in a developing country.

We should note that we do not observe preferences themselves, we observe choices made in experiments and answers given to survey questions. These choices will typically depend on both underlying preferences and the environment. If there are aggregate shocks (e.g., a recession) this should affect the average level of preferences, but an individual’s relative position in the distribution should not change. Our results account for the environment by controlling for idiosyncratic characteristics of the environment (e.g., household-level income and village fixed effects) when measuring the stability of choices.

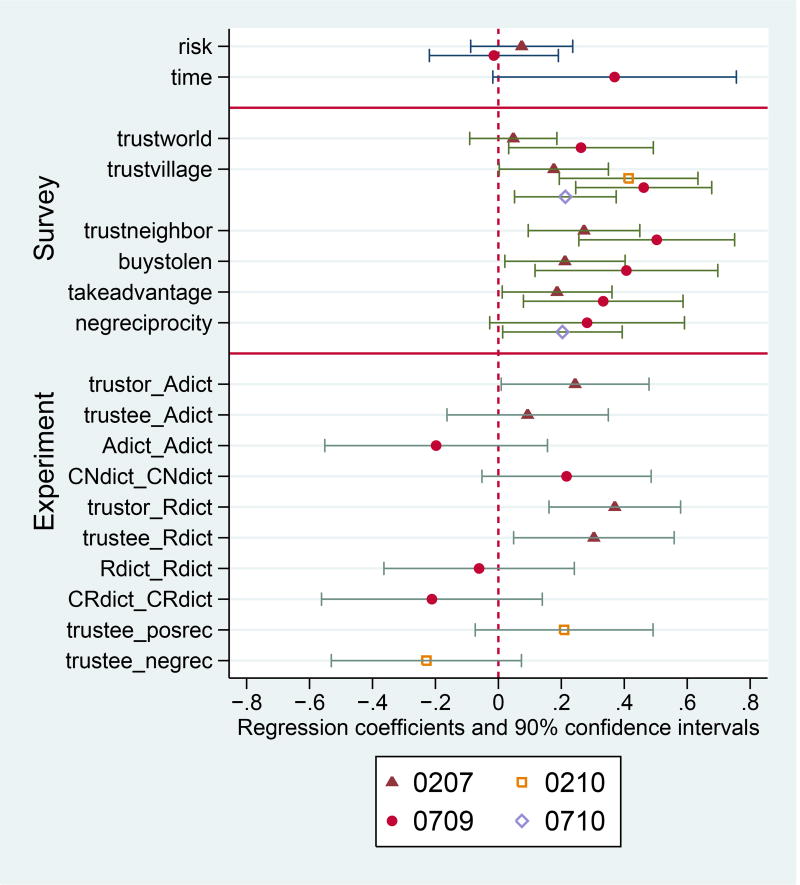

We find that survey measures of social preferences are extremely stable over long periods of time in our data. None of the experimental measures approaches such a level of stability. Experimental measures of risk preferences are not stable over time. We find weak evidence of stability in experimental measures of time and social preferences, but the data seems too noisy to estimate this relationship with much precision.

One potential explanation for the fact that experimental measures of preferences are not stable over time in our data might be that households are facing shocks which cause their decisions or preferences to change. For rural Paraguayans who do not have access to crop or health insurance, such shocks may take a large toll on the household’s financial situation. We test whether income, health, and theft shocks are correlated with play in games or answers to survey questions. We find no evidence that these shocks have any impact on the choices people make in experiments or their answers to the survey preference questions. The only somewhat consistent effect is that households which experienced health shocks give less in experiments. We do find some suggestive evidence that experiences in earlier experiments impact play in future games; e.g., that being linked with a more generous partner in the past makes a player more generous himself in future games and more likely to punish ungenerous players. But, it seems that these effects have more to do with learning about the game rather than actual changes in preferences.

In sum, in our dataset survey measures of social preferences are quite consistent over time; on the other hand, experimental measures of social and time preferences are only weakly correlated over time. Experimental measures of risk preferences are not at all stable. Neither income, theft, nor health shocks impact answers to survey questions or choices made in experiments.

The greater stability of social preferences measured by surveys may be due to many reasons (also see Section 4). One reason is that many of the theoretically elegant experiments designed by experimental economists may be better suited for student populations found in university labs who tend to be highly educated and non-poor.

Recent research suggests that economic scarcity consumes attentional resources and interferes with cognitive function which may then lead to errors and biases in decision making (Shah et al., 2012). Schofield (2014) shows that nutritional scarcity also interferes with cognitive function. Benjamin et al. (2013) and Burks et al. (2009) give evidence that individuals with lower cognitive ability exhibit more behavioral biases in risk and time experiments and play less consistently in risk experiments. The scarcity experienced by poor individuals in rural areas of developing countries may lead the decisions they make in experiments to contain more errors than decisions made by individuals who do not experience such need. This may then explain why the decisions they make in experiments are not correlated over time.

In addition to the effect of poverty on cognitive function and decision making, the low levels of education in our rural Paraguayan sample may imply that the experiments are significantly harder for them to understand than are the survey questions. In our data the median level of education is only five years and the maximum is twelve. Using a representative sample in the Netherlands, Choi et al. (2014) find that less educated respondents play less consistently in risk and time preference games. Similarly, Charness and Viceisza (2015) compare rates of player inconsistency between experiments run in the developed and developing world, and find that a greater share of players in the developing world make inconsistent choices.

Using a sample of Canadians, Dave et al. (2010) find that simpler experiments measuring risk aversion work better among less numerate subjects, as more complex experiments lead to much noise in decision-making. Charness and Viceisza (2015) measure the risk preferences of a population of rural Senegalese individuals and find suggestive evidence that more complex tasks lead to lower levels of understanding and more noisy responses. Cook (2015) finds that data collected in risk aversion experiments in low income countries contains suggestive evidence that players are confused.

In terms of comparing survey measures to experimental measures, Dohmen et al. (2011) and Lönnqvist et al. (2014) find that survey measures of risk aversion perform better than experimental measures and we find the same for social preferences. On the other hand, Burks et al. (2012) find that a survey measure of time preference perform worse than experimental measures. Although economists have tended to dismiss survey measures of preferences, they may want to reconsider the usefulness of such measures.

This discussion highlights the difficulties involved in conducting economic experiments in developing countries among populations with high levels of poverty and low levels of education. More research on how to best design experiments for developing country populations, as well as on when survey questions might be more informative than experiments is still needed.

2 Previous Literature

While Loewenstein and Angner (2003) ponder whether underlying preferences are stable over time from a philosophical and theoretical perspective, we empirically examine whether preferences measured from surveys and experiments are stable. Below we review three related strands of the literature. The empirical literature on preference stability over time is most directly related and we review those papers first and most thoroughly. Our paper can also be related to the growing number of studies looking at how shocks such as illness, income shocks, civil wars, and natural disasters lead to changes in measures of preferences.2 Finally, we briefly review the literature on the stability of preferences as measured in different games but played on the same day, which is relevant since in many cases we do not play exactly the same game in each year.

2.1 Stability over Time of Preferences Measured in Experiments

First we review papers studying the stability of measures of risk, time, and social preferences over time. Compared with our data, much of this literature either uses a smaller sample, a shorter period of time, or both. These papers only focus on one type of preference with the large majority studying only risk preferences. More recently the number of papers looking at time preferences has been growing, while there are still very few that look at the stability of social preferences. Very few of these papers discuss attrition, although the sample sizes reported often suggest that many fewer individuals participate in later rounds compared to earlier rounds of the experiments.3 In addition many focus on student populations, which leads to worries about selection and external validity. The majority use better-educated samples from developed countries, although this has been changing more recently.

Most of the papers which report correlations find that measured preferences are significantly correlated over time. This may potentially be due to the file drawer effect - many individuals run similar experiments with the same population at two points in time but if the correlations are not significant then the results may not be published anywhere and are instead filed away in a drawer. There are two components to the file drawer effect: the fact that papers finding no correlation are more likely to be rejected; and the fact that researchers who do not find a significant correlation are less likely to write up the results.

Risk Preferences

The results regarding stability of risk preferences are summarized in Table 1. The evidence suggests that risk preferences are relatively stable over time, with reported correlations ranging from a low of −.38 to a high of 0.68. If one excludes the studies with fewer than 100 observations, the range is 0.13 to 0.55.4,5 Interestingly, there does not appear to be much systematic difference in the correlations reported by studies which measure risk preferences over shorter versus longer periods of time. Likewise, there doesn’t appear to be much difference in the the stability of hypothetical versus incentivized measures, or from student versus non-student populations.

Table 1.

Stability of Risk Preferences

| Paper | Population | Time | Corr | Sig | Inc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menkhoff and Sakha (2014) | 384 rural Thai | 5 years | ? | yes | inc |

| Levin et al. (2007) | 124 US children/parents | 3 years | 0.20 – 0.38 | yes | inc |

| Guiso et al. (2011) | 666 Italian investors | 2 years | 0.131 | yes | hyp |

| Kimball et al. (2008) | 700 older Americans | 2 years | 0.27 | ? | hyp |

| Love and Robison (1984) | 23 US farmers | 2 years | −0.38 – 0.231 | no2 | hyp |

| Sahm (2012) | 12000 older Americans | multiple years | 0.18 | yes | hyp |

| Beauchamp et al. (2012) | 489 Swedish twins | 1 year | 0.483 | yes | hyp |

| Goldstein et al. (2008) | 75 Americans | 1 year | 0.43 | yes | hyp |

| Lönnqvist et al. (2014) | 43 German students | 1 year | 0.21 | no | inc |

| Smidts (1997) | 205 Dutch farmers | 1 year | 0.44 | yes | hyp |

| Wehrung et al. (1984) | 84 N. American businessmen | 1 year | 0.36 | yes | hyp |

| Andersen et al. (2008) | 97 Danes | 3– 17 months | ? | yes | inc |

| Harrison et al. (2005) | 31 US students | 6 months | ? | yes | inc |

| Vlaev et al. (2009) | 69 British students/adults | 3 months | 0.20–0.634 | yes | hyp |

| Horowitz (1992) | 66 US students & 23 PTA | 2 months | ? | no | inc |

| Wölbert and Riedl (2013) | 53 Dutch students | 5–10 weeks | 0.36–0.68 | yes | inc |

| Schoemaker and Hershey (1992) | 109 US MBA students | 3 weeks | 0.55 | yes | hyp |

| Hey (2001) | 53 British students | a few days | ? | yes | inc |

Corr - the correlation of risk preferences over time. Sig - whether risk preferences are significantly related over time. Inc - whether the experiment was incentivized rather than hypothetical.

Our own calculation, from the raw data reported in the original paper.

In fact, the negative correlation of −0.38 is significant at the 10% level.

This is a polychoric correlation, which may be larger because it suffers from less attenuation bias.

Interestingly, the one correlation which was not statistically significantly different than 0 (value of 0.20)was for the risk question which used the Multiple Price List (MPL) mechanism over gains. This is arguably the most common method for collecting risk preferences.

Time Preferences

The results regarding stability of experimentally measured time preferences can be found in Table 2. Of the papers looking at the stability of time preferences, the reported correlation coefficients range from 0.004 to 0.75. Most numbers seem to be slightly higher than the range of risk preference correlation coefficients mentioned above, although there are fewer observations. If one excludes the studies with less than 100 observations four studies remain, with correlations (for the comparisons with over 100 observations) ranging from 0.09 to 0.68. This is similar to the range of the correlations in the risk aversion studies.6

Table 2.

Stability of Time Preferences

| Paper | Population | Time | Corr | Sig | Inc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meier and Sprenger (2015) | 250 US low-income | 2 years | 0.40 | yes | inc |

| Krupka and Stephens Jr (2013) | 1194 Americans | 1 year | ? | ? | hyp |

| Harrison et al. (2006) | 97 Danes | 3 – 17 months | ? | yes | inc |

| Kirby et al. (2002) | 95–123 Bolivian Amerindians | 3 –12 months | 0.004–0.46 | yes | inc |

| Kirby (2009) | 46–81 US students | 1 – 12 months | 0.57–0.75 | yes | inc |

| Li et al. (2013) | 336–516 Americans | 1 week – 14 months | 0.33–0.68 | yes | hyp |

| Wölbert and Riedl (2013) | 53 Dutch students | 5–10 weeks | 0.61–0.68 | yes | inc |

| Dean and Sautmann (2014) | 961 peri-urban Malians | 1 week | 0.61–0.67 | yes | inc |

Corr - the correlation of time preferences over time. Sig - whether time preferences are significantly related over time. Inc - whether the experiment was incentivized rather than hypothetical.

Social Preferences

The results regarding stability of experimentally-measured social preferences can be found in Table 3. In this case, correlation coefficients range from −0.15 to 0.69, similar to the range for time and risk preferences. If one excludes the studies with less than 100 observations then only one study remains, with a range of 0.12 to 0.28.7

Table 3.

Stability of Social Preferences

| Paper | Population | Time | Corr | Sig | Inc | game / preference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carlsson et al. (2014) | 196 Vietnamese | 6 years | 0.12 – 0.28 | yes | inc | public good |

| Lönnqvist et al. (2014) | 22 German students | 1 year | 0.69 | yes | inc | trust |

| Brosig et al. (2007) | 40 German students | 3 months | 0.09–0.481 | no/yes | inc | altruism |

| Brosig et al. (2007) | 40 German students | 3 months | −0.15–0.561 | no/yes | inc | sequential PD |

Corr - the correlation of social preferences over time. Sig - whether social preferences are significantly related over time. Inc - whether the experiment was incentivized rather than hypothetical.

Our own calculation, from the raw data reported in the original paper.

Scanning all three tables, no obvious patterns appear. The results are similar for games played at longer and shorter intervals, for incentivized and hypothetical games, and for games played with student and non-student populations. While we see that there are many papers which study the stability of measures of preferences over time, our contribution is that we look at both experimental and survey measures of all three (risk, time, and social preferences) in a relatively large dataset over relatively long periods of time with a diverse population in a developing country, and that we also have data on other real-world outcomes for these same individuals.

2.2 Impact of Events on Preferences: Economic Shocks, Natural Disasters, and Conflict

Research studying how shocks affect preferences usually starts from the underlying implicit assumption that, in the absence of the shock, preferences would have changed less. Originally researchers were most interested in studying how job market shocks cause changes in preferences. Many papers find that changes in income, unemployment, health status, and family composition do not lead to changes in risk preferences (Brunnermeier and Nagel, 2008; Chiappori and Paiella, 2011; Sahm, 2012) or time preferences (Harrison et al., 2006; Meier and Sprenger, 2015).8

Specific examples of papers which find no evidence of changes in preferences after varying shocks in low income settings include Giné et al. (2014) who find no impact of household shocks such as a death in the family or shortfalls in expected income on time preferences in rural Malawi. Carvalho et al. (2014) look at low-income Americans and find that individuals are more present-biased regarding money before payday than after, but they hypothesize that this is most likely due to differences in liquidity constraints rather than differences in preferences since they behave similarly for inter-temporal decisions regarding non-monetary rewards and play no differently in risk experiments. Meier and Sprenger (2015) suggest that changes in measured preferences over time thus may either be noise, or may be orthogonal to socio-demographics.

Another group of papers disagrees with this assessment and does find that preferences are affected by shocks. Fisman et al. (2014) find that the Great Recession increased selfishness while Gerrans et al. (2015) and Necker and Ziegelmeyer (2015) find that it decreased risk tolerance. Krupka and Stephens Jr (2013) show that economic shocks are correlated with changes in time preferences.9

In a developing country context Dean and Sautmann (2014) find, using weekly data, that individuals become more patient when they have positive income or savings shocks, and more impatient when they face negative shocks. Menkhoff and Sakha (2014) find that agricultural shocks (drought and flood) and economic shocks (an increase in the price of inputs or the collapse of a business) cause rural Thai respondents to become more risk averse. Finally, using a randomized controlled trial, Carvalho et al. (2014) find that Nepali women who are randomly offered savings accounts are more risk-taking and more patient than those who are not. Kandasamy et al. (2014) provide a psychological mechanism to explain the effects of stress on risk aversion: they find that randomly raising the stress hormone cortisol increases risk aversion.

Education has also sometimes been found to have an impact on preferences. Jakiela et al. (2015) find that higher educational achievement among female primary school students in Kenya increased their generosity. Lührmann et al. (2015) find that randomly providing high school students with financial education decreases present bias. Booth et al. (2014) find that randomly assigning female college students to single-sex discussion sections causes them to make more risky decisions in games. On the other hand, Dasgupta et al. (2014) find that a randomized vocational training program among women residing in Indian slums does not effect risk preferences.

There is a new burgeoning literature looking at how preferences are impacted by extreme events such as civil wars or natural disasters. While this literature is fascinating, authors tend to face two main difficulties. First, data on preferences is usually only available after the event and not before. Second, it is difficult to construct a control group, since these events affect different populations differentially. Papers looking at the impact of natural disasters and civil wars find amazingly divergent results. The number of these papers has been growing at a rapid clip, with no signs of converging to one consistent set of results. This lack of consistency may suggest that there are nuances involved in the experience of disaster that we are currently not considering, or that experimental choices are filled with much noise. It would be helpful for future researchers to attempt to reconcile these results.

The research on natural disasters (including earthquakes, famines, floods, hurricanes, and tsunamis) suggests that such shocks increase risk aversion (Cameron and Shah, 2015; Cassar et al., 2011; Chantarat et al., 2015; Samphantharak and Chantarat, 2015; van den Berg et al., 2009), decrease risk aversion (Bchir and Willinger, 2013; Eckel et al., 2009; Hanaoka et al., 2014; Ingwersen, 2014; Page et al., 2014; Willinger et al., 2013), have no effect at all on risk preferences (Becchetti et al., 2012), or have no consistent effect on risk preferences (Said et al., 2015); increase impatience (Bchir and Willinger, 2013; Cassar et al., 2011; Sawada and Kuroishi, 2015), decrease impatience (Callen, 2011; Chantarat et al., 2015), or have no consistent effect on time preferences (Willinger et al., 2013); increase trust (Cassar et al., 2011), decrease trust (Chantarat et al., 2015), or have no effect on the level of trust (Andrabi and Das, 2010); decrease trustworthiness (Fleming et al., 2014); and increase altruism (Becchetti et al., 2012; Chantarat et al., 2015), decrease altruism (Samphantharak and Chantarat, 2015), or have no consistent effect on altruism (Afzal et al., 2015).10

The research on conflict (including civil wars and political violence) likewise shows contradictory results. Findings suggest that conflict may decrease risk aversion (Voors et al., 2012) or increase risk aversion (Callen et al., 2014; Kim and Lee, 2014; Moya, 2011); decrease patience (Voors et al., 2012); lower trust (Cassar et al., 2013; De Luca and Verpoorten, 2015) or have no effect on trust (Grosjean, 2014); increase initial trustworthiness but lower subsequent trustworthiness (Becchetti et al., 2014); increase altruism (Voors et al., 2012) or decrease altruism to out-groups with no effect within group (Silva and Mace, 2014); and increase egalitarianism (Bauer et al., 2014).

Finally, there is a bit of evidence regarding how experiences in one experiment may impact play in later experiments and real-world decisions. Conte et al. (2014) and Matthey and Regner (2013) find that individuals who have participated in experiments in the past behave more selfishly in subsequent experiments. Mengel et al. (2015) show that subjects become more risk averse after playing games involving ambiguity rather than games involving pure risk only, and He and Hong (2014) show that subjects become more risk averse after playing games involving higher levels of risk. Cai and Song (2014) find that experiencing more disaster in an insurance game increases uptake of a real insurance product but does not influence risk aversion as measured in a subsequent game. Jamison et al. (2008) find that being deceived in one experiment leads participants to behave more inconsistently (exhibit more multiple-switching behavior) in future experiments measuring risk aversion.

2.3 Stability of Preferences Measured in Different Games

There are many papers which look at the stability of preferences measured in different games and we only mention a few here. This subsection of the literature review is not as comprehensive as the subsection reviewing the literature on stability measured over time. Most research shows that risk preferences are not stable across different settings or different games (Anderson and Mellor, 2009; Berg et al., 2005; Binswanger, 1980; Dulleck et al., 2015; Eckel and Wilson, 2004; Isaac and James, 2000; Kruse and Thompson, 2003; Vlaev et al., 2009). On the other hand, Choi et al. (2007) find that risk preferences are stable across games when the games in question are quite similar to one another. Reynaud and Couture (2012) find that risk preferences are stable both across games and within the same game at different levels of stakes, while Dulleck et al. (2015) using a similar design only find stability across levels of stakes for the same game but not across different games.

Time preferences have been found to be correlated across goods (Reuben et al., 2010; Ubfal, 2014) and across lengths of time (Halevy, 2015; McLeish and Oxoby, 2007). Social preferences have been found to be rather stable both using variants of the same game (Andreoni and Miller, 2002; Fisman et al., 2007) and using very different games (Ackert et al., 2011; de Oliveira et al., 2012), although Blanco et al. (2011, Table 3) find a low correlation across most games in their sample.

Although our review of previous research suggests that risk preferences may be less stable across different games than time and social preferences are, our review in this subsection of the literature on stability across games is not exhaustive nor does it take into account publication bias. One message that seems to be supported by the majority of papers is that preferences tend to be more stable when measured in similar games or games which are variants of one another. When preferences are measured in very different games, they are less likely to be consistent. This conclusion was reached long ago by Slovic (1972) with regards to experiments on risk taking and seems to more generally continue to be verified.

3 Datasets

We have survey and experimental data from 2002, 2007, 2009, and 2010 for different subsets of the same sample. As the original purpose of this data collection was not to look at the stability of preferences over time, both the samples and the experiments varied across rounds. Summary statistics of all the outcome variables analyzed here can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary Statistics

| Mean | Sd | Min | Max | # Obs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bet in 2002 | 3.43 | 2.05 | 0 | 8 | 189 |

| roll of die in risk game in 2002 | 3.37 | 1.69 | 1 | 6 | 172 |

| # risky choices in 2007 (hyp) | 2.09 | 1.77 | 0 | 5 | 449 |

| # risky choices in 2009 (hyp) | 1.55 | 1.53 | 0 | 5 | 176 |

| time preference in 2007 (hyp) | 199.35 | 561.22 | 75 | 5000 | 449 |

| time preference in 2009 (hyp) | 111.99 | 116.61 | 75 | 1000 | 176 |

|

| |||||

| sent as trustor in 2002 | 3.74 | 1.99 | 0 | 8 | 188 |

| sent as dictator in anonymous game in 2007 | 5.08 | 2.69 | 0 | 14 | 371 |

| sent as dictator in chosen non-revealed game in 2007 | 5.39 | 2.68 | 0 | 14 | 371 |

| sent as dictator in revealed game in 2007 | 5.47 | 2.69 | 0 | 14 | 371 |

| sent as dictator in chosen revealed game in 2007 | 5.93 | 2.84 | 0 | 14 | 371 |

| sent as dictator in anonymous game in 2009 | 2.51 | 1.94 | 0 | 10 | 176 |

| sent as dictator in chosen non-revealed game in 2009 | 2.72 | 2.02 | 0 | 13 | 129 |

| sent as dictator in revealed game in 2009 | 3.01 | 2.18 | 0 | 12 | 176 |

| sent as dictator in chosen revealed game in 2009 | 3.69 | 2.71 | 0 | 14 | 129 |

|

| |||||

| share returned as trustee in 2002 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0 | 1 | 188 |

| amount received as trustee in 2002 | 11.23 | 5.97 | 0 | 24 | 188 |

| proportion received back as trustor in 2002 | 1.30 | 0.61 | 0 | 3 | 175 |

|

| |||||

| trust people in the world in 2002 (survey) | 2.40 | 0.64 | 1 | 5 | 214 |

| trust people in the world in 2007 (survey) | 2.58 | 0.92 | 1 | 5 | 449 |

| trust people in the world in 2009 (survey) | 2.84 | 1.15 | 1 | 5 | 176 |

|

| |||||

| trust people in the village in 2002 (survey) | 3.14 | 1.13 | 1 | 5 | 214 |

| trust people in the village in 2007 (survey) | 3.22 | 1.09 | 1 | 5 | 449 |

| trust people in the village in 2009 (survey) | 3.40 | 1.22 | 1 | 5 | 176 |

| trust people in the village in 2010 (survey) | 3.40 | 1.11 | 1 | 5 | 119 |

|

| |||||

| trust closest neighbors in 2002 (survey) | 3.96 | 1.27 | 1 | 5 | 214 |

| trust closest neighbors in 2007 (survey) | 3.97 | 1.30 | 1 | 5 | 449 |

| trust closest neighbors in 2009 (survey) | 3.96 | 1.34 | 1 | 5 | 176 |

|

| |||||

| would villagemates take advantage if had opportunity in 2002 (survey) | 2.90 | 1.15 | 1 | 5 | 214 |

| would villagemates take advantage if had opportunity in 2007 (survey) | 2.44 | 1.09 | 1 | 5 | 449 |

| would villagemates take advantage if had opportunity in 2009 (survey) | 2.56 | 1.14 | 1 | 5 | 176 |

|

| |||||

| bad to buy something you know is stolen in 2002 (survey) | 0.90 | 0.30 | 0 | 1 | 214 |

| bad to buy something you know is stolen in 2007 (survey) | 0.87 | 0.34 | 0 | 1 | 449 |

| bad to buy something you know is stolen in 2009 (survey) | 0.85 | 0.36 | 0 | 1 | 176 |

|

| |||||

| negative reciprocity in 2007 (survey) | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0 | 1 | 449 |

| negative reciprocity in 2009 (survey) | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0 | 1 | 176 |

| negative reciprocity in 2010 (survey) | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 | 119 |

|

| |||||

| positive reciprocity in 2010 | 0.71 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 | 119 |

| negative reciprocity in 2010 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0 | 1 | 119 |

Note: Hyp denotes that the game was hypothetical. All data is from experiments unless otherwise stated.

From looking at the summary statistics table, we note something which may hint at the results we will find below. The means of the survey questions (for example, questions such as what share of people in the world do you trust) appear to be much more stable over time than the experimental data (for example, the amounts sent in the dictator games). On the other hand, we do see a similar pattern in both the 2007 and 2009 dictator data, where the least is sent in the anonymous game; the most is sent in the chosen-revealed game; and the amounts sent in the revealed and chosen non-revealed games lie somewhere in between. A discussion of and explanation for this pattern in the 2007 data can be found in Ligon and Schechter (2012).

3.1 Sample Selection

In 1991, the Land Tenure Center at the University of Wisconsin in Madison and the Centro Paraguayo de Estudios Sociológicos in Asunción worked together in the design and implementation of a survey of 285 rural Paraguayan households in fifteen randomly chosen villages in three departments (comparable to states) across the country. The households were stratified by land-holdings and chosen randomly.11 The original survey was followed by subsequent rounds of survey data collection in 1994 and 1999. Subsequent rounds including both survey and experimental data were conducted in 2002, 2007, 2009, and 2010.

In 2002 the survey began to include questions measuring trust and economic experiments were conducted. By that point it was only possible to interview 214 of the original 285 households. Of the 214 households interviewed, 188 also sent a household member to participate in the economic experiments.

In 2007, new households were added to the survey in an effort to interview 30 households in each of the fifteen villages. (This meant adding between 6 and 24 new households in any village in addition to the original households.) Villages range in size from around 30 to 600 households. In total 449 households were interviewed, of which 371 sent a household member to participate in the economic experiments. We interviewed 195 of the previous 214 households and added 254 new households.

In 2009, we returned only to the two smallest villages. Of the 59 households interviewed in these two villages in 2007, we interviewed someone from 52 of those households in 2009. In this round, the experiments were conducted as part of the survey and so all surveyed households also participated in the experiments.

Finally, in 2010 we returned to the ten villages in the two more easily accessible departments, excluding the five villages in the more distant department. These ten villages included the two villages interviewed in 2009. In this round, we played a reciprocity experiment with 119 of the 299 individuals interviewed in 2007 in those ten villages. The households who participated were those chosen by political middlemen.

The numbers cited in the previous paragraphs refer to the number of households followed over time. As preferences are individual characteristics, rather than household characteristics, we also care about whether the same individual responded to the survey or participated in the experiments. In 2002 we told individuals that we preferred to run the surveys and games with the household heads but allowed other household members to participate if the head was not available. For the 2007 survey we tried to follow up with the 2002 game player if possible. The 2007 games were with the household head if possible. In 2009 we interviewed all adults in each household. In 2010 we followed up with the 2007 survey respondent. For more details on the 2002 dataset see Schechter (2007a), for the 2007 dataset see Ligon and Schechter (2012), and for the 2010 dataset see Finan and Schechter (2012).

In sum, while 214 households were interviewed in 2002, and the sample was expanded to cover 449 households in 2007, the number of observations we can compare across rounds is smaller. Table 5 presents the number of observations in each survey and the number of observations for the same person across rounds.

Table 5.

Sample Sizes

| 02 survey | 02 game | 07 survey | 07 game | 09 participate | 10 participate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 02 survey | 214 | 142 | 123 | 79 | 21 | 39 |

| 02 game | 188 | 139 | 103 | 17 | 43 | |

| 07 survey | 449 | 282 | 49 | 119 | ||

| 07 game | 371 | 41 | 81 | |||

| 09 participate | 176 | 23 | ||||

| 10 participate | 119 |

Note: Each cell contains the number of individuals participating in both the row and the column data.

The individuals we follow over time may be a rather select sample. They are still alive and haven’t migrated away. They also include those households in which we were consistently able to contact the same individual in each round. One could conduct a selection analysis if one had access to a variable which affected the likelihood of staying in our sample, but did not affect social, time, or risk preferences. Though we can think of no such variable, we believe that our sample consists of precisely those people whose preferences are most likely to be consistent over time. They are the most stable individuals: people who continue to live in the same village and be available to be interviewed over a period of many years. So, we believe that our estimates of the stability of preferences over time should overstate this stability. Given that we find that experimental measures of preferences are not very stable in our sample, one might expect that a sample without such attrition problems would exhibit even less stability.12

We test whether the people who remain in our survey are different from those who attrit. Table 6 shows average characteristics (as measured in 2002) for two mutually exclusive subsets of the individuals who participated in 2002: those how remained in later rounds and those who attrited. Table 7 shows average characteristics (as measured in 2007) for the individuals who participated in 2007 and did or did not attrit in later rounds. To distinguish how much selection there is at the village versus the individual level (since not all villages were visited in each survey round) we show unconditional tests for significant differences in characteristics and also show such tests conditional on village fixed effects.

Table 6.

Tests for Sample Attrition from 2002

| 2002 survey and 2007 survey | 2002 survey and 2010 survey | 2002 game and 2007 game | 2002 game and 2010 game | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in both (1) |

attrit (2) |

diff1 (3) |

diff2 (4) |

in both (5) |

attrit (6) |

diff1 (7) |

diff2 (8) |

in both (9) |

attrit (10) |

diff1 (11) |

diff2 (12) |

in both (13) |

attrit (14) |

diff1 (15) |

diff2 (16) |

|

| hhd income | 19,611 (47,977) | 18,830 (50,209) | 780 (6,811) [0.880] | 1,724 (6,065) [0.768] | 10,323 (8,840) | 21,275 (53,656) | −10,952** (4,299) [0.091]* | 787 (1,499) [0.590] | 13,821 (18,475) | 23,167 (69,961) | −9,346 (7,800) [0.102] | −8607 (7467) [0.113] | 10,348 (8,396) | 20,330 (55,512) | −9,981** (4,791) [0.229] | 1,472 (1,439) [0.293] |

| log(hhd inc) | 9.25 (0.97) | 9.07 (0.98) | 0.18 (0.14) [0.162] | 0.24* (0.12) [0.070]* | 8.96 (0.80) | 9.22 (1.01) | −0.26* (0.15) [0.155] | 0.05 (0.15) [0.695] | 9.09 (0.85) | 9.14 (1.06) | −0.05 (0.14) [0.591] | −0.03 (0.13) [0.771] | 8.96 (0.77) | 9.16 (0.99) | −0.21 (0.14) [0.328] | 0.10 (0.15) [0.403] |

| hhd size | 5.72 (2.51) | 5.48 (2.31) | 0.23 (0.33) [0.466] | 0.34 (0.31) [0.233] | 5.59 (2.09) | 5.62 (2.49) | −0.03 (0.38) [0.951] | 0.59 (0.40) [0.313] | 5.67 (2.51) | 5.48 (2.44) | 0.19 (0.36) [0.580] | 0.23 (0.35) [0.513] | 5.53 (2.13) | 5.60 (2.57) | −0.07 (0.39) [0.870] | 0.39 (0.41) [0.392] |

| male | 0.76 (0.43) | 0.77 (0.42) | −0.01 (0.06) [0.934] | −0.01 (0.06) [0.849] | 0.79 (0.41) | 0.76 (0.43) | 0.03 (0.07) [0.665] | 0.13 (0.08) [0.194] | 0.73 (0.45) | 0.65 (0.48) | 0.08 (0.07) [0.276] | 0.10 (0.07) [0.181] | 0.74 (0.44) | 0.68 (0.47) | 0.07 (0.08) [0.381] | 0.22** (0.09) [0.030]** |

| age | 52.89 (13.25) | 50.30 (16.60) | 2.59 (2.11) [0.262] | 2.39 (2.08) [0.375] | 53.85 (12.75) | 51.33 (15.20) | 2.52 (2.33) [0.337] | 0.61 (2.39) [0.799] | 50.74 (15.15) | 46.21 (20.05) | 4.53* (2.64) [0.201] | 4.03 (2.91) [0.198] | 52.56 (14.62) | 47.54 (18.32) | 5.01* (2.69) [0.114] | 4.09 (3.20) [0.229] |

| ed | 4.54 (2.38) | 4.98 (2.38) | −0.43 (0.36) [0.236] | −0.36 (0.35) [0.323] | 4.38 (1.99) | 4.81 (2.66) | −0.42 (0.38) [0.197] | −0.51 (0.41) [0.186] | 4.55 (2.37) | 5.09 (2.78) | −0.54 (0.38) [0.275] | −0.45 (0.44) [0.392] | 4.26 (1.88) | 4.96 (2.73) | −0.70* (0.36) [0.058]* | −0.79* (0.43) [0.084]* |

| bet | 3.57 (2.20) | 3.27 (1.85) | 0.30 (0.30) [0.423] | 0.28 (0.31) [0.453] | 3.77 (1.91) | 3.34 (2.08) | 0.43 (0.34) [0.183] | 0.81** (0.34) [0.026]** | ||||||||

| sent as trustor | 3.73 (2.10) | 3.76 (1.86) | −0.04 (0.29) [0.900] | −0.19 (0.31) [0.533] | 3.95 (2.11) | 3.68 (1.95) | 0.27 (0.36) [0.588] | 0.70* (0.36) [0.289] | ||||||||

| trust in village | 3.13 (1.15) | 3.15 (1.09) | −0.02 (0.15) [0.911] | −0.05 (0.16) [0.791] | 3.15 (1.09) | 3.14 (1.14) | 0.02 (0.19) [0.928] | −0.11 (0.22) [0.434] | 3.17 (1.16) | 3.19 (1.11) | −0.02 (0.17) [0.900] | −0.16 (0.18) [0.434] | 3.12 (1.10) | 3.19 (1.15) | −0.08 (0.19) [0.698] | −0.35* (0.21) [0.087]* |

| # Obs. | 123 | 91 | 39 | 175 | 103 | 85 | 43 | 145 | ||||||||

Note: Standard deviations are in parentheses for means while heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are in parentheses for the tests of differences. Wild cluster bootrap p-values are in brackets.

Per-comparison significance: *** p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1.

Columns 1, 5, 9, and 13 show information for the non-attriters while Columns 2, 6, 10, and 14 show information for the attriters. Diff1 is coefficient in regression controlling only for participation at the later date. Diff2 is coefficient in regression aditionally controlling for village fixed effects. Income is in thousands of Guarani. All variables are measured in 2002.

Table 7.

Tests for Sample Attrition from 2007

| 2007 survey and 2009 survey | 2007 survey and 2010 survey | 2007 game and 2009 game | 2007 game and 2010 game | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in both (1) |

attrit (2) |

diff1 (3) |

diff2 (4) |

in both (5) |

attrit (6) |

diff1 (7) |

diff2 (8) |

in both (9) |

attrit (10) |

diff1 (11) |

diff2 (12) |

in both (13) |

attrit (14) |

diff1 (15) |

diff2 (16) |

|

| hhd income | 14,614 (11,564) | 24,545 (39,286) | −9,931*** (2,559) | −4,161 (3,946) | 17,510 (13,006) | 25,607 (42,735) | −8,097*** (2,638) [0.050]** | 243 (1,481) [0.904] | 14,743 (11,728) | 21,600 (31,981) | −6,858*** (2,529) | 1,634 (2,016) | 15,922 (8,752) | 22,216 (34,051) | −6,294*** (2,224) [0.036]** | 320 (1,290) [0.853] |

| log(hhd inc) | 9.33 (0.75) | 9.70 (0.82) | −0.37*** (0.11) | −0.34 (0.21) | 9.56 (0.67) | 9.70 (0.86) | −0.14* (0.08) [0.279] | 0.03 (0.08) [0.758] | 9.35 (0.72) | 9.63 (0.78) | −0.28** (0.12) | −0.03 (0.16) | 9.50 (0.65) | 9.63 (0.81) | −0.12 (0.09) [0.259] | 0.06 (0.09) [0.628] |

| hhd size | 4.88 (2.63) | 4.91 (2.36) | −0.03 (0.39) | −0.24 (0.66) | 4.98 (2.58) | 4.88 (2.32) | 0.10 (0.27) [0.750] | 0.29 (0.27) [0.355] | 4.78 (2.49) | 5.00 (2.37) | −0.22 (0.41) | −1.05 (0.93) | 4.75 (2.29) | 5.03 (2.41) | −0.28 (0.29) [0.197] | −0.08 (0.29) [0.818] |

| male | 0.63 (0.49) | 0.68 (0.47) | −0.04 (0.07) | −0.04 (0.17) | 0.64 (0.48) | 0.68 (0.47) | −0.04 (0.05) [0.337] | 0.06 (0.06) [0.044]** | 0.49 (0.51) | 0.65 (0.50) | −0.16** (0.08) | −0.01 (0.20) | 0.65 (0.48) | 0.63 (0.48) | 0.03 (0.06) [0.612] | 0.13** ((0.07) [0.051]* |

| age | 48.49 (17.56) | 50.15 (15.30) | −1.66 (2.60) | 7.71 (6.91) | 51.39 (15.62) | 49.46 (15.51) | 1.93 (1.67) [0.420] | 1.72 (1.88) [0.567] | 48.17 (18.80) | 47.95 (16.14) | 0.23 (3.04) | 16.93** (6.97) | 51.95 (15.09) | 46.86 (16.64) | 5.09*** (1.94) [0.035]** | 6.32*** (2.13) [0.022]** |

| ed | 5.12 (2.50) | 5.05 (3.03) | 0.08 (0.39) | −1.94 (1.25) | 5.05 (2.63) | 5.05 (3.09) | −0.00 (0.29) [0.988] | −0.23 (0.34) [0.570] | 4.90 (2.36) | 5.21 (2.98) | −0.31 (0.40) | −1.91** (0.81) | 4.89 (2.10) | 5.26 (3.11) | −0.37 (0.30) [0.231] | −0.78** (0.36) [0.047]** |

| risky choices | 1.71 (1.68) | 2.13 (1.78) | −0.42 (0.25) | −0.87 (0.56) | 2.04 (1.78) | 2.10 (1.77) | −0.06 (0.19) [0.756] | −0.21 (0.22) [0.349] | 1.90 (1.67) | 2.13 (1.79) | −0.23 (0.28) | −0.45 (0.67) | 2.15 (1.80) | 2.09 (1.77) | 0.06 (0.23) [0.822] | −0.13 (0.25) [0.646] |

| time preference | 120 (67) | 209 (593) | −89*** (31) | 8 (18) | 156 (456) | 215 (594) | −58 (53) [0.446] | −23 (56) [0.593] | 117 (59) | 196 (570) | −79** (32) | 19 (18) | 182 (550) | 188 (536) | −7 (69) [0.942] | 59 (74) [0.626] |

| sent as dictator | 4.59 (2.33) | 5.15 (2.73) | −0.56 (0.39) | −0.84 (0.75) | 4.79 (2.46) | 5.17 (2.75) | −0.38 (0.32) [0.468] | 0.17 (0.35) [0.717] | ||||||||

| trust in village | 3.51 (1.19) | 3.18 (1.08) | 0.33* (0.18) | 0.61* (0.37) | 3.35 (1.15) | 3.17 (1.07) | 0.19 (0.12) [0.072]* | 0.12 (0.13) [0.190] | 3.71 (1.19) | 3.22 (1.07) | 0.49** (0.19) | 0.66** (0.31) | 3.47 (1.10) | 3.21 (1.09) | 0.26* (0.14) [0.051]* | 0.14 (0.15) [0.304] |

| # Obs. | 49 | 400 | 119 | 330 | 41 | 330 | 81 | 290 | ||||||||

Note: Standard deviations are in parentheses for means while heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are in parentheses for the tests of differences. Wild cluster bootrap p-values are in brackets.

Per-comparison significance: *** p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1.

Columns 1, 5, 9, and 13 show information for the non-attriters while Columns 2, 6, 10, and 14 show information for the attriters. Diff1 is coefficient in regression controlling only for participation at the later date. Diff2 is coefficient in regression aditionally controlling for village fixed effects. Income is in thousands of Guarani. All variables are measured in 2002.

Looking across the two tables, the number of significant differences we find is higher than what we would have expected by chance. In 2009 and 2010 we followed up with the poorer villages, and left out the richer villages. Many of these differences decrease in size once controlling for village fixed effects and so seem to be due to selection in terms of which villages we re-surveyed rather than selective attrition within villages. Once controlling for village fixed effects, it still appears that those individuals who remain in our sample over time are slightly older and less educated; as well as slightly more trusting. In all tables which follow we control for village fixed effects, age, education, sex, log income, and household size to help account for some of this selection.

3.2 Survey Data

The data for which we have the most continuity across rounds is the survey trust data. In 2002 the survey asks what share of people in the world, people in the village, and close neighbors they trust. The survey also asks what share of their village-mates would take advantage of them if given the opportunity. Possible answers for both sets of questions are 5-all, 4-more than half, 3-half, 2-less than half, and 1-none. While the correct cardinality is approximately 1, .75, .50, .25, and 0, as this is just a linear transformation of the 1–5 scale we have left the variable in its original form for regression analysis. Respondents are also asked if they think it is bad if somebody buys something knowing it is stolen (The variable equals 1 if they say it is very bad and 0 if they say it is a little bad or not bad at all.)

These same questions all reappear in the 2007 survey, although for the final question it is made more specific asking if they think it is bad if somebody buys a radio knowing it is stolen. In this round a new negative reciprocity question was added asking if someone put them in a difficult position would they to do the same to that person (1 equals always or sometimes, 0 equals never). All of these questions were continued in the 2009 survey. The 2010 survey was shortened so that it only asks about trust in villagemates and negative reciprocity.

We include measures of trust (from both surveys and experiments) in our analysis of social preferences although one might argue that trust measures beliefs about others rather than an underlying social preference (Fehr, 2009; Sapienza et al., 2013). For example, if one sees that trust is going down over time, as measured either by a decrease in the amount sent in a trust game (described later) or an increase in the share of one’s village-mates one believes would take advantage if given the opportunity, this may be due to one of many different reasons. It may be because the respondent’s social preferences are changing, for example the respondent has become inherently more trusting; it may be because social preferences in the village are changing, for example trustworthiness in the village is going down causing the individual to be more trusting; or it may be because the respondent’s beliefs have changed, for example the respondent experienced a robbery and so now believes his village-mates to be less trustworthy. Given that some piece of trust is due to underlying preferences, and that we can control for village fixed effects which capture the environment of trustworthiness in the village, we include trust in our analysis.

3.3 Experimental Data

Because each round of data collection was conducted to answer different questions, rather than with the express purpose of looking at the stability of preferences over time, some of the experiments conducted in each round differ while some are repeated.

3.3.1 Risk Preferences

In 2002 we conducted an incentivized risk experiment in which players were given 8,000 Gs and chose how much of that to bet on the roll of a die (Schechter, 2007b). At that point in time the exchange rate was approximately 4,800 Gs to the dollar, and a day’s wages was 12,000 Gs. Participants could choose to bet 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8 thousand Gs, and different rolls of the dice led to losing all their bet, half their bet, keeping their bet, or earning an extra 50%, 100%, or 150% of their bet. The measure of risk preferences is the amount of money bet on the die.

The 2007 and 2009 surveys both contained hypothetical risk questions based on the question asked in the Mexican Family Life Survey (MxFLS). The respondent is asked if he prefers 50 thousand Gs for sure or a 50-50 chance of 50 or 100 thousand Gs. If he prefers the lottery, he is then asked if he prefers 50 thousand Gs to a 40/100 lottery. Respondents who still prefer the lottery are then offered 30/100, 20/100, and finally 10/100 lotteries. The measure of risk preferences is the number of risky choices preferred. The 2010 survey does not measure risk preferences.

3.3.2 Time Preferences

The 2007 and 2009 surveys ask hypothetical questions measuring time preferences, while the 2002 and 2010 surveys do not broach this topic. Respondents are asked whether they prefer 50,000 Gs today or 75,000 Gs a month from today. For those who prefer the money today, they are asked if they would prefer 50,000 Gs today or 100,000 Gs a month from today. If the person still prefers the money today, he is asked how much one would have to offer him to convince him to wait for a month. The measure of time preferences is the amount of money he would need one month later.

3.3.3 Social Preferences

Every round of survey collection conducted at least one incentivized experiment measuring social preferences, although some of the experiments differed across rounds.

2002 Trust Game

We conducted an incentivized trust game in which every participant played both the role of trustor and trustee (Berg et al., 1995). The trustor was given 8,000 Gs and decided how much of that to keep and how much to send to the trustee. The trustee was randomly chosen from the group of players and received the amount sent by the trustor, tripled. The trustee then decided how much of that to keep and how much to send back to the trustor, if any. These games were anonymous as neither player knew with whom he was matched. The amount sent by the trustor is often used to measure trust (although it also measures risk aversion and altruism), while the amount sent by the trustee is often used to measure trustworthiness or reciprocity (although it also measures altruism).

2007 Variants of Dictator Game

Participants were asked to play four distinct dictator games. For more details see Ligon and Schechter (2012). The games varied in whether or not the dictator was anonymous, and in whether the recipient was randomly selected from the set of households in the village, or was chosen by the dictator. In each of the games the dictator was given 14,000 Gs and decided how to divide it between herself and another household. The other household could be any household in the village, not just those participating as dictators in the experiment. We doubled any money shared by the dictator and also added a random component with mean 5,000 Gs before passing it on to the recipient at which point the game ended.

In the ‘Anonymous-Random’ (AR) game, the dictator decided how much to share with a randomly selected household in the village, and neither the dictator nor the recipient ever learned who the other was. This is the canonical dictator game and it measures undirected altruism or benevolence. In the ‘Revealed-Random’ (RR) game, the dictator once more chose how much to send to a randomly selected household. It was known that the identities of the dictator and recipient would subsequently be revealed to each other. The amount sent measures a combination of undirected altruism and fear of sanctions.

In the two ‘Chosen’ games the dictator chose a single, common recipient. In the ‘Anonymous-Chosen’ game, the recipient never learned the identity of the dictator. The amount sent measures a combination of undirected and directed altruism. In the ‘Revealed-Chosen’ game, the dictator’s identity is revealed to the recipient. The amount sent in this final game measures a combination of undirected and directed altruism, fear of sanctions, and reciprocity.

2009 Variants of Dictator Game

Participants played in games which were quite similar to those in 2007. The difference is that in 2009 no random component was added to the amount received by the recipient. And, some (but not all) participants played the two ‘Chosen’ games.

2010 Reciprocity Game

Respondents in 2010 were asked to play a reciprocity game similar to that designed by Andreoni et al. (2003) with the political middlemen who chose them. The respondent was told that the middleman was given 12,000 Gs and could choose to send 2, 4, 6, 8, or 12,000 Gs to the respondent. The respondent could take the money and choose to do nothing, or he could choose to reward or fine the middleman. For every 100 Gs the respondent put toward the reward or fine, the middleman received an extra 500 Gs, or had 500 Gs taken away from him. Neither player could earn less than 0 Gs total.

We used the strategy method, asking the respondent what he would do if he were to receive each potential amount. Here we define a negative reciprocal individual as one who would fine the middleman if he sent 2,000 Gs (the lowest possible amount to send) and a positive reciprocal individual as one who would reward him if he sent all 12,000 Gs.

3.3.4 Experiences while Playing

Not only will we look at the stability of preferences over time, but we will also look at whether and how experiences in the experiments in one year impact play in later years of the experiments. The different experiences we will look at include the following:

In the 2002 risk games the player’s winnings were determined by the roll of the die. The die was rolled in front of the player. The higher the roll of the die, the luckier the player was and the more he won.

In the 2002 trust game, the trustee received a certain amount from the trustor. Receiving more can change the trustee’s perception of the trust and generosity of his village-mates.

In the 2002 trust game, the trustor chose how much to send to the trustee. The trustee then decided how much of that, if any, to return. Receiving back a higher share of the amount sent can change the trustor’s perception of the generosity and reciprocity of his village-mates.

3.4 Shock Data

Finally, we study how preferences react to household experiences. We have data on income, health, and theft shocks which are arguably some of the most important shocks faced by agricultural households who do not have access to crop insurance or health insurance. Specifically, the 2002, 2007, and 2009 surveys contain information on household income and theft experienced in the past year. Those rounds also asked the days of school or work lost to illness in the past year.

4 Analysis and Results

Our hypothesis is that preferences as measured by experiments and surveys are significantly correlated over time. In the first stage of our analysis we look at the stability of preferences (as measured in experiments and surveys) over time. We show the correlation coefficient between the two variables of interest and evaluate whether it is statistically significantly different from 0. In addition, we run regressions of the later variable on the earlier variable with village fixed effects while also controlling for log income, sex, age, and education level as measured in the later year.13 In results not shown here, we re-run all of the analysis dividing our sample into those below and above the median in terms of age (50 years) or education (5 years) but do not find any consistent differences.

In all tables of results we show asterisks (*) to represent levels of significance according to traditional p-values which treat each test as a lone independent test. These p-values are based on standard errors which are robust to heteroskedasticity. Given that we are testing multiple hypotheses at the same time, these traditional p-values may over-reject the hypothesis of zero correlation of measures over time. To account for this, we additionally show plus signs (+) to represent levels of significance according to q-values for False Discovery Rates (FDR) to correct for multiple comparisons. We use the calculation designed by Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) and explored in detail by Anderson (2008).

In addition to simply correcting our standard errors for heteroskedasticity, we can also correct for potential correlations between observations within clusters (villages). Because we do not have a large number of clusters, we use the wild cluster bootstrap suggested by Cameron et al. (2008) to generate p-values. The 2002 and 2007 data sets have 15 villages; the 2010 data has 10 villages; and the 2009 data has only 2 villages. Because two villages is too few to account for clustering, we do not show clustered p-values in any analysis using data from 2009.

Theory would suggest that if the decisions made by the same individual at two points in time are not highly correlated, it is because the environment has changed. For example, think about an individual with exogenously determined income y. Assume this person has constant relative risk aversion (CRRA) utility, with coefficient of relative risk aversion γ. He must decide between a sure thing (with payoff s) and a lottery (winning payoff h with probability p and outcome l with probability (1 − p)). The individual chooses whether or not to gamble where g = 0 if he chooses the safe option and g = 1 if he chooses the gamble. His total consumption will be his exogenous income plus his earnings in the risk game.

The maximization problem is thus:

This equation makes clear that a person may make different decisions at different points in time either because his underlying risk preference γ has changed, or because his income y has changed. A monetary windfall may cause a person to choose the more risky option. A similar income confound arises for social and time preferences. And, one could imagine shocks other than income, such as health shocks, changing the optimal decision. The main point is that a person can have stable preferences but still behave differently in experiments at different points in time.

We account for this in our study in three ways. First, if everyone is getting poorer or wealthier across the board at the same rate, then we would still imagine that the people who were most risk averse in earlier years would continue to be the people who were most risk averse in later years. Second, our regressions control for income, education, sex, age, and village fixed effects and so our results are conditional on the environment. Finally, if the environment played a large role, then we would expect to find significant results in an analysis looking at how income, health, and theft shocks are related to play in games. But we do not find much correlation between shocks and preferences.

Overall, we find that experimental measures are less stable than survey measures. This may be because some of the experiments varied across years, while the survey questions remained the same in each survey. Semantically, when we compare play in the same game at different points in time we are running “test-retest” analysis, while when we compare play in different games purportedly measuring the same preferences at different points in time we are running a “construct validity” analysis. That said, even when we do have experimental measures for the exact same game at two points in time, for example the variants of the dictator games or the repeated risk game, the choices are not any more stable than measures of the same preferences from different games.

The decisions made in the experiments are not very correlated over time, nor are they correlated with shocks to the environment, suggesting that individuals’ decisions may contain substantial noise. This may be more likely in a developing country context where participants experience high levels of poverty and scarcity and have low levels of education.

With so much data from so many different experiments and survey questions, in so many different rounds of data collection, it would be possible to look at thousands of correlations. We limit ourselves by only showing results which fit the following criteria. First, given that we have much incentivized experimental social preference data, we do not analyze the data from the hypothetical social preference experiments.14 We do analyze the hypothetical risk and time preference data, since we have less data on these preferences.

Second, we do not include comparisons between the 2002 and 2009 data, since the sample size in those comparisons is only 21, nor do we include comparisons between the 2009 and 2010 data, since that sample size is only 23. The comparisons we do include are 2002 vs 2007, 2002 vs 2010, 2007 vs 2009, and 2007 vs 2010.

Third, we only compare variables which are measures of the same thing at different points in time. For example, we look at how survey measures of trust are correlated over time, and we look at how experimental measures of trust are correlated over time. But, we do not look at how survey measures of trust are correlated with experimental measures of trust over time, or at how experimental measures of trust are correlated with experimental measures of risk aversion over time. Although there are definitely many interesting comparisons to be made, we avoid data mining by setting these rules for ourself in advance.

4.1 Stability of Preferences

4.1.1 Risk and Time Experiments

Table 8 shows the results for risk and time preferences. The 2002 game was incentivized. The same hypothetical risk game was played in both 2007 and 2009. The research cited in Section 2.3 has shown that players do not have stable preferences across different risk games played at the same point in time. This makes it less likely that we will find risk preferences are correlated between 2002 and 2007 but this critique should not affect the 2007–2009 comparison. Still, the table shows no significant correlation between risk preferences measured at different points in time. If we run the analysis using coefficients of relative risk aversion rather than the number of risky choices, we again find insignificant results of similar magnitudes. The magnitudes of the correlations in measures of risk preferences over time we find in Table 8 are far below those magnitudes cited in Section 2.1.

Table 8.

Stability of Risk and Time Preferences

| Explanatory variable |

Dependent variable |

Correlation coefficient |

Regression coefficient |

# Obs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bet in 2002 | # risky choices in 2007 (hyp) | 0.070 | 0.066 (0.087) [0.488] | 140 |

| bet in 2002 | # risky choices in 2007 (hyp-d) | 0.043 | 0.045 (0.090) [0.586] | 112 |

| # risky choices in 2007 (hyp) | # risky choices in 2009 (hyp) | −0.059 | −0.012 (0.102) | 49 |

| # risky choices in 2007 (hyp-d) | # risky choices in 2009 (hyp-d) | −0.009 | 0.003 (0.112) | 32 |

| Time preference in 2007 (hyp) | Time preference in 2009 (hyp) | 0.432*** ++ | 1.036 (0.646) | 49 |

Notes: Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are in parentheses. Wild cluster bootrap p-values are in brackets.

Per-comparison significance: ***p <0.01,

p <0.05,

p <0.10.

FDR q-values: +++ q <0.01,

q <0.05,

q <0.10 calculated for 5 hypotheses within table and column.

In regression column these are based on the heteroskedasticity robust standard errors. Controls in regressions include log income, sex, age, education, and village fixed effects. Hyp denotes that the game was hypothetical. Hyp-d additionally denotes that individuals choosing the strictly dominated optoin are excluded.

On the other hand, time preferences (measured from the answers to the same series of hypothetical questions in 2007 and 2009) are relatively stable over time. We cannot reject that the coefficient on time preferences in 2007 predicting time preferences in 2009 is 1. We also can not reject that it equals 0 at conventional levels of confidence, although it is statistically different from 0 at the 12% significance level. This is in stark contrast to the results for the hypothetical risk games in 2007 and 2009 where the coefficient is a much more precise 0. This may be because time preferences are more stable over time than risk preferences, or because people understood the time questions better and so they contain less noise.

One indication that the 2007/2009 risk preference data contains much noise is the fact that 19% of respondents in 2007 and 27% in 2009 preferred 50,000 Gs for sure to a 50/50 chance of winning 50,000 or 100,000 Gs, even after the game was explained to them a second time. If one assumed that an equal share did not understand the game but choose the better option by chance, this would imply that 38–54% of respondents do not understand the game. Such low levels of understanding wreak havoc on our ability to use these games to measure risk preferences.

While the share of individuals choosing dominated options may seem high, they are in fact quite similar to those found in other studies. In the MxFLS, upon which the questions we used in our survey were based, nearly a quarter of the individuals chose the dominated option even after having it explained a second time (Hamoudi, 2006). In a similar set of questions in the 2007 Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS), 41% of the almost 30,000 respondents chose the dominated option (Caruthers, 2013). Even in the US, Bhargava et al. (2015) find that over half of individuals choose dominated health insurance plans, and bad choices are even more common among the poor and the elderly.

This is reminiscent of the debate following Gneezy et al. (2006) who find that many individuals value a risky prospect less than its worst possible realization. Subsequent work argued that the effect is eliminated either when focussing on the subset of the subject pool which passes a comprehension test or when making the instructions more clear (Keren and Willemsen, 2009; Rydval et al., 2009). Choices made by individuals who do not fully understand the experiment may be filled with much noise, and thus these choices may not be significantly correlated over time.

This suggests that one reason we find such low correlations for measures of risk aversion compared to those found in the rest of the literature may be that our sample has a much lower level of education than most of the other experiments. Choi et al. (2014) find that younger, more educated, and wealthier respondents behave more consistently across multiple games measuring risk and time preferences played at the same point in time.

We explore this in two ways. First, we exclude those individuals who chose the strictly dominated option. We present those results in Table 8 and find that the magnitudes are no larger and the correlations no closer to being significant when excluding those individuals.

Second, we divide our sample into those below and above the median in terms of age or education. When doing that we find a similar lack of significance in all groups for risk preferences.15 Given that the median in our sample is 5 years of education and the maximum is 12, the more educated half of our sample still has much lower education levels than respondents in most other samples studied in the literature. For time preferences, the relatively strong correlation seems to be coming entirely from the younger and more educated halves of the population.

Looking forward, in the next subsection we show evidence that the more specific a trust question is, the more stable its answer. While some risk games conducted in developing countries are framed in terms of crop choice or other real-world investment decisions, our risk games were very abstract. It would be interesting for future research to study whether decisions made in framed experiments are more stable than those made in artefactual (neutrally framed) experiments.

4.1.2 Social Preference Surveys

Table 9 shows the results for the survey questions which measure social preferences and were repeated across years.16 Many of the variables show a surprising amount of stability over time. Almost all of the comparisons are significant. On the other hand, when looking at the regression coefficients we can also reject that the relationship is one-to-one.

Table 9.

Stability of Social Preferences in Surveys

| Years | Variable | Correlation coefficient |

Regression coefficient |

# Obs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 vs 2007 | trust people in the world | 0.064 | 0.068 (0.119) [0.585] | 123 |

| 2007 vs 2009 | trust people in the world | 0.284** + | 0.339* (0.176) | 49 |

|

| ||||

| 2002 vs 2007 | trust people in the village | 0.137 | 0.162* (0.096) [0.211] | 123 |

| 2002 vs 2010 | trust people in the village | 0.440*** ++ | 0.425*** (0.132)++ [0.011]** | 39 |

| 2007 vs 2009 | trust people in the village | 0.525*** +++ | 0.525*** (0.146)+++ | 49 |

| 2007 vs 2010 | trust people in the village | 0.254*** ++ | 0.206** (0.094)+ [0.052]* | 119 |

|

| ||||

| 2002 vs 2007 | trust closest neighbors | 0.273*** ++ | 0.275** (0.108)++ [0.013]** | 123 |

| 2007 vs 2009 | trust closest neighbors | 0.463*** +++ | 0.545*** (0.159)+++ | 49 |

|

| ||||

| 2002 vs 2007 | bad to buy something you know is stolen | 0.141 | 0.226* (0.123) [0.230] | 123 |

| 2007 vs 2009 | bad to buy something you know is stolen | 0.372*** ++ | 0.353** (0.150)+ | 49 |

|

| ||||

| 2002 vs 2007 | would villagemates take advantage if had opportunity | 0.251*** ++ | 0.167* (0.094) [0.108] | 123 |

| 2007 vs 2009 | would villagemates take advantage if had opportunity | 0.355** ++ | 0.420** (0.190)+ | 49 |

|

| ||||

| 2007 vs 2009 | negative reciprocity | 0.360** ++ | 0.236 (0.154) | 49 |

| 2007 vs 2010 | negative reciprocity | 0.245*** ++ | 0.176* (0.099) [0.176] | 119 |

Notes: Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are in parentheses. Wild cluster bootrap p-values are in brackets.

Per-comparison significance: ***p <0.01,

p <0.05,

p <0.10.

FDR q-values: +++ q <0.01,

q <0.05,

q <0.10 calculated for 14 hypotheses within table and column.

In regression column these are based on the heteroskedasticity robust standard errors. Controls in regressions include log income, sex, age, education, and village fixed effects.

Imagine a model in which observed trust is equal to an underlying trust parameter plus two additional pieces: recent experiences and measurement error. If most of the variation around the underlying trust parameter is due to recent experiences, we might expect the correlation to go down as more time passed. On the other hand, if most of the variation around the underlying trust parameter were due to measurement error, then we might expect the size of the correlations to be similar over time.

The correlation and regression coefficients are almost always highest for the 2007 vs 2009 comparison, which is also the comparison over the shortest time span. Unfortunately, this is also the only comparison which involves the 2009 data. Because the 2009 data only comes from the two smallest villages, there is very little overlap between either 2002 or 2010 and 2009. Thus, we cannot test whether the high correlation between 2007 and 2009 is due to the select sample in 2009 or if it is due to the shorter time span.17

Given the large magnitude of the coefficients for the one comparison shown between 2002 and 2010 (trust people in village), it suggests that it is not the case that the correlation goes down significantly over long periods of time. In fact, we can replicate the results in Table 9, but only for those 39 individuals who are surveyed in 2002, 2007, and 2010. When we do so (results not shown), we continue to find no significant difference in the coefficients for the 2002–2007 2007–2010, and 2002–2010 comparisons for trust in village, with 2002–2007 continuing to be the smallest coefficient. This may imply that most variation is due to measurement error rather than the influence of recent experiences.

These questions may measure innate preferences which are stable and not strongly affected by shocks. On the other hand, the stability of answers to these questions may indicate that individuals have a well-developed self-identity or feel a strong social norm regarding how to answer the questions which may or may not be what researchers have in mind when modeling social preferences.

There also seems to be some suggestive evidence that as the questions become more specific, the responses exhibit more stability. For example, the correlation and regression coefficients regarding trusting people in the world are rather low and often not significant. The coefficients regarding trusting people in the village are higher, while the coefficients regarding trusting close neighbors are usually even higher, although most of these differences are not significant.18

4.1.3 Social Preference Experiments

Table 10 shows the results for the experimental measures of social preferences. The results are loosely divided up by social preference into altruism, trust, and reciprocity. Many of the decisions made in the games measure multiple preferences at the same time. For example, the amount sent by the trustor in the trust game is a combination of both trust and altruism. The amount returned by the trustee in the trust game combines altruism, trust, and reciprocity. The amounts sent by the dictator in the two non-revealed games measure altruism. The amounts sent in the two revealed games additionally measure trust since a person who trusts his village-mates more will send more in the hopes that the recipient will return more to the dictator once the recipient learns the dictator’s identity. Finally, the reciprocity experiments measure reciprocity.

Table 10.

Stability of Social Preferences in Games

| Explanatory variable |

Dependent variable |

Correlation coefficient |

Regression coefficient |

# Obs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALTRUISM | ||||

| sent as trustor in 2002 | sent as dictator in anonymous game in 2007 | 0.297*** ++ | 0.298* (0.173) [0.221] | 103 |

| share returned as trustee in 2002 | sent as dictator in anonymous game in 2007 | 0.132 | 1.171 (1.939) [0.628] | 103 |

| sent as dictator in anonymous game in 2007 | sent as dictator in anonymous game in 2009 | −0.107 | −0.180 (0.190) | 41 |

| sent as dictator in chosen non-revealed game in 2007 | sent as dictator in chosen non-revealed game in 2009 | 0.138 | 0.126 (0.091) | 33 |

|

| ||||

| TRUST | ||||

| sent as trustor in 2002 | sent as dictator in revealed game in 2007 | 0.354*** +++ | 0.513*** (0.174)++ [0.037]** | 103 |

| share returned as trustee in 2002 | sent as dictator in revealed game in 2007 | 0.283*** ++ | 4.335* (2.189) [0.118] | 103 |

| sent as dictator in revealed game in 2007 | sent as dictator in revealed game in 2009 | 0.049 | −0.050 (0.145) | 41 |

| sent as dictator in chosen revealed game in 2007 | sent as dictator in chosen revealed game in 2009 | −0.118 | −0.236 (0.229) | 33 |

|

| ||||

| RECIPROCITY | ||||

| share returned as trustee in 2002 | positive reciprocity in 2010 | 0.009 | 0.473 (0.376) [0.309] | 43 |

| share returned as trustee in 2002 | negative reciprocity in 2010 | 0.123 | −0.430 (0.334) [0.216] | 43 |

Notes: Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are in parentheses. Wild cluster bootrap p-values are in brackets.

Per-comparison significance: ***p <0.01,

p <0.05,

p <0.10.

FDR q-values: +++ q <0.01,

q <0.05,

q <0.10 calculated for 10 hypotheses within table and column.

In regression column these are based on the heteroskedasticity robust standard errors. Controls in regressions include log income, sex, age, education, and village fixed effects.

When looking at the stability of different social preferences over time we look at choices made in different games, some of which are more pure measures of the preference than others. For example, in 2007 and 2009 we have measures of altruism from anonymous dictator games which should arguably be the best measures of altruism. In 2002, we only have the amounts sent as trustor and trustee in the trust game. Although altruism is sure to influence those decisions, trust and reciprocity will influence them as well. We look at whether these decisions are correlated over time not because we believe that there is a single latent trait which drives behavior across all the experiments. We look at them because we believe that all three of those decisions involve altruism, and if altruism is a stable preference over time then those decisions should be correlated.

With regards to altruism, we find that the amount sent as trustor in 2002 and the amount sent in the anonymous game in 2007 are positively correlated. We find a strong correlation between the two measures of trust in 2002 and 2007. Individuals who give generously in one game at one point in time tend to be more generous in a different game at a different point in time.