Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to present the results of newborns who were referred to advanced audiology centers after newborn hearing screening, and to determine concordance of our results with the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines about the ages of hearing loss, aid fitting, and cochlear implantation.

Materials and Methods

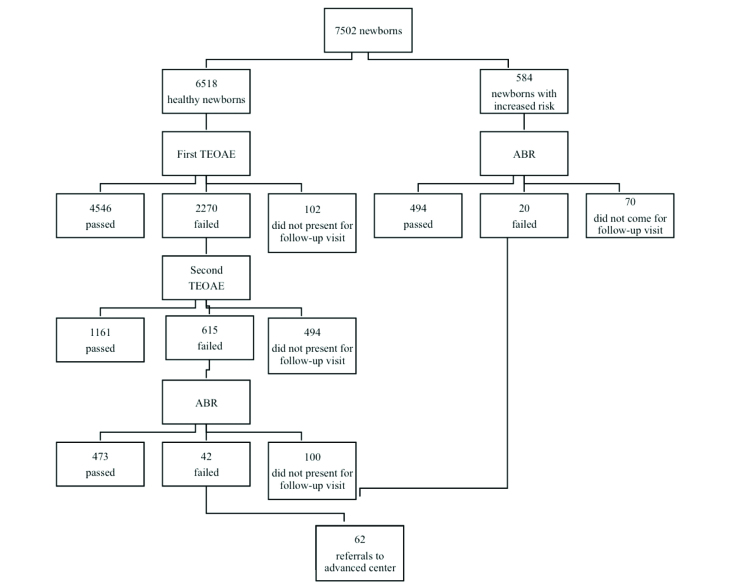

A total of 7502 newborns were screened in Gaziosmanpaşa Taksim Research and Training Hospital between March 2014 and June 2016 using the transient otoacustic emissions test as the first two steps and automated auditory brainstem response test for the third step. Newborns who had risk factors were screened using the automated auditory brainstem response only. Newborns who failed the screening tests were referred to advanced audiology centers.

Results

Of the 7502 newborns, 6736 (90%) completed the screening. The ratio of hearing loss was 0.08%. Six of 62 newborns who failed auditory brainstem response test and were referred to advanced audiology centers had severe bilateral hearing loss. One of the patients was not fitted with a hearing aid because the family refused it. The other one was not fitted an aid and did not undergo cochlear implantation because of severe and treatment-resistant acute otitis media. The age of diagnosis for the rest was before three months, and except for one patient, hearing aid fitting was before six months. The age of cochlear implantation was 12 months for two patients and 14 months for two patients.

Conclusion

Ninety percent of patients completed the screening, the age of diagnosis for hearing loss was before three months and aid fitting was before six months, except for one patient. The results of the study were compatible with the diagnosis and treatment guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Keywords: Hearing loss, hearing screening, newborn

Introduction

Early diagnosis of hearing loss, which takes an important place among congenital anomalies in terms of prevalence, is important. Early diagnosis and treatment provides academic, perceptional, and social and economic benefit because it positively affects language development. In healthy newborns, congenital hearing loss occurs with a rate ranging between 1:1000 and 3:1000, and it is observed in 2–4% of babies treated in intensive care units (1, 2). This prevalence is much higher compared with phenylketonuria and hypothyroidism, which are screened in the neonatal period (3–5). Therefore, it should be screened and early diagnosis and treatment should be achieved. Both families and physicians are unsuccessful in recognizing babies with hearing loss in the first year of life. In addition, half of the affected babies cannot be determined because only the babies who are thought to have an increased risk of hearing loss are investigated. Thus, the diagnosis of hearing loss may delayed until the age of three years in children in whom screening is not performed at birth (6). Accordingly, newborn hearing screening is very important for babies with advanced and extremely advanced hearing loss in terms of being diagnosed as early as possible. Detection of congenital hearing loss in the first three months and early rehabilitation with a hearing aid in the first six months and cochlear implantation at the appropirate time should be targeted (7–11). Two methods are used for newborn hearing screening: evoked otoacoustic emissions (EOAEs) and auditory brainstem response (ABR). Two forms of evoked otoacoustic emissions are used most frequently in hearing screening. These include transient evoked otoacustic emissions (TEOAE) and distortion product otoacustic emissions (DPOAE) tests. Although both are successful, TEOAE is preferred more frequently than DEPOAE because it is technically more simple, its test time is shorter and can detect even mild degrees of hearing loss (12, 13). Transient evoked otoacoustic emissions are the acoustic echo response created by the external hair cells in the internal ear to the stimulus given, which can be measured in the external auditory canal. They show the physical status of the cochlea and measure cochlear functions independent of the central nervous system (2). Auditory brainstem response is a measurement of the responses of the electrical potentials created by intermittent stimuli in the auditory canals and brainstem in the first 10–20 ms using surface electrodes on the skull (14). The reason that these tests are being used as screening tests is the fact that they are noninavasive, inexpensive, and easily applicable tests.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended hearing screening in babies who have an increased risk of hearing loss in their statement in 1982. However, when it was found that 50% of 126 babies who were diagnosed as having congenital hearing loss in the Colorado Newborn Hearing Loss Project between 1992 and 1996 did not carry any risk in terms of hearing loss, the AAP published a statement in 1999 recommending that all newborns should be screened, hearing loss should be confirmed in the first three months, and necessary interventions should be implemented in six months (15, 16). In Turkey, newborn hearing screening was initiated in 1994 for the first time in Hacettepe University and in 1998 in Marmara Univeristy. With a protocol signed between the Rectorship of Hacettepe University and the Prime Minister Deparment of Administration of the Disabled and the Ministry of Health, newborn hearing screening was initiated in 2000 in Ankara Zübeyde Hanım Maternity and in 2003 in Dr. Zekai Tahir Burak Maternity Hospital. The Newborn Screening Program was expanded such that it included some pilot hospitals including Gazi and Dokuz Eylül University Hospitals at the end of 2003 and all 81 provinces in 2012 (17).

In our study, the results of hearing screening performed in 7502 newborn babies between March 2014 and June 2016 in our hospital were evaluated. The clinical characteristics and accompanying risk factors of the babies who had hearing loss, and the ages at the times of diagnosis and treatment of hearing loss (placement of hearing aid and cochlear implantation) were determined. The aim of the study was to evaluate how compatible the results of the Newborn Hearing Screening Program were with the diagnostic and therapeutic targets of the AAP.

Material and Methods

A total of 7502 babies comprising those who were born between March 2014 and June 2016 in Gaziosmanpaşa Taksim Education and Research Hospital and followed up beside their mothers, those who were being followed up in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), and those who were born in other healthcare centers in our province and referred to our hospital for hearing screening were included in this study. The study data were evaluated retrospectively with patient admittence forms. The results of 62 patients who failed the screening program and were referred to upper level centers were learned by calling the families. The newborns were evaluated by an experienced odiometrist according to the Ministry of Health Newborn Hearing Screening Program TEOAE device hearing screening protocol. In this program, conditions that are considered risk factors in terms of congenital hearing loss and hearing loss in the early childhood (maternal TORCHS infections; history of infectious disease during pregnancy including toxoplasmosis, rubella, citomegalovirus, herpes, syphylisis and familial history of congenital hearing loss, head and facial anomalies related with the external auditory canal and auricula, syndromes accompanied by hearing loss, a birth weight below 1500 g, low APGAR score at birth, hyperbilirubinemia in the neonatal period, bacterial menigitis, use of ototoxic drugs, history of prolonged mechanical ventilation) were interrogated for each newborn screened. Hearing screening was performed during the work days before the baby was discharged from hospital. A written document stating that hearing screening should be performed in 15 days at the latest was given to families of babies who were discharged on holidays and hearing screening was performed in babies who were brought to hospital. The babies who were hospitalized in the NICU were screened in one month at the latest.

The tests were performed when the baby was in the mother’s lap or on a flat surface in a special room. Appropriate probes for the baby’s external auditory canal were selected. Hearing screening was performed with TEOAE and ABR tests using a MADSEN Accu-Screen PRO device. In newborns who had any of the above-mentioned risk factors, screening was performed directly with ABR. Automatically obtaining a result “passed” was considered a criterion for passing the screening test. The babies who had a test result of bilateral or unilateral “failed” were referred to advanced hearing centers. In newborns who had no risk factors, hearing screening performed initially with the TEOAE test was performed with a three-step protocol. In the first step, bilateral measurement was performed and the babies in whom bilateral emission response was obtained were considered to have passed the screening test. The babies in whom bilateral or unilateral emission response could not be achieved were called back to repeat the test. In the second step, the measurement was repeated in these babies. The babies who showed a “passed” response in both ears in the second test were considered to have passed the screening. A specialist performed the autoscopic examination in babies who failed unilaterally or bilaterally in the second step. If any problem related with the external auditory canal and/or middle ear including remnants or infection that could affect the TEOAE response was found on examination, appropriate treatment was given and the baby was called back to repeat the test. Babies in whom treatment had been initiated and who could not pass the test were called back 15 days later and when ABR was performed. Babies who failed the auditory brainstem response test were referred to advanced hearing centers with suspicious baby registration forms with the objective of making a definitive diagnosis. The families of babies who were referred to advanced centers with suspicious baby registration forms were called by phone and it was learned if the baby had hearing loss, at which month the diagnosis was made, if hearing loss was present, and at which month treatment was initiated.

Ethics committee approval was obtained from Gaziosmanpaşa Taksim Education and Research Hospital Ethics Commitee for the study (08.03.2017–12).

Statistical Analysis

In this study statistical analyses were performed using the NCSS 10 program.

Results

Three thousand eight hundred twenty-six (51%) of 7502 babies who were included in the assessment were female and 3676 (49%) were male. Four thousand eight hundred seventy-six (65%) of the babies were born by normal vaginal delivery and 2626 (35%) were born by cesarean section; 584 (7.8%) of these carried risk in terms of hearing loss: 62 patients had a familial history of congenital hearing loss, 17 patients were born with a birth weight of 1500 g and below, 124 patients had a history of hyperbilirubinemia, 351 patients had a history of ototoxic drug use, and 30 patients had a history of mechanical ventilation and ototoxic drug use for five days or more. In the newborn babies included in our study, the rate of congenital hearing loss was found as 0.08%.

The ABR test was performed directly in 584 of 7502 babies because they had risk factors, whereas the TEOAE screening test was performed primarily in the other babies; 4546 (60.6%) of the babies passed the first TEOAE test. One hundred two (1.3%) babies who were discharged on the weekend and given an appointment for TEOAE test did not present for the first TEOAE test and these patients could not be contacted. One thousand one hundred sixty-one (15.5%) of 2270 newborns who participated in the second TEOAE screening passed the test. Four hundred ninety-four (6.6%) babies who did not pass the first screening and were called back could not be contacted. Four hundred seventy-three (6.3%) of 615 babies who took and failed the second TEOAE test did pass the ABR screening test. Forty-two (0.6%) of the babies failed the ABR screening and 100 (1.3%) did not present for the ABR test, and these patients could not be reached. It was planned to perform ABR screening directly in 584 (6.8%) babies who had risk factors in terms of hearing loss, but ABR screening could only be performed in 514 (6.8%) newborns who carried increased risk; 70 (0.9%) babies did not present for ABR screening and 20 babies failed the ABR screening (Table 1). Among the 20 newborns who had increased risk in terms of hearing loss and failed the auditory brainstem response screening test, 12 had a history of ototoxic drug use, three had hyperbilirubinemia, and five had a familial history of hearing loss. A total of 62 babies were referred to advanced hearing centers owing to advanced or extremely advanced hearing loss because they failed the ABR test unilaterally or bilaterally (Table 2). It was learned that one of the patients who were referred was lost, 12 patients never attended the advanced center and hearing loss was not found in 32 patients who presented to the advanced center. The results of twelve patients are not known because they could not be contacted. It was learned that bilateral hearing loss was found in six of the newborns who were referred and they were recommended to use a hearing aid. It was learned that bilateral cochlear implantation was performed in four babies who had hearing loss, the process still continued for one patient and a hearing aid could not be placed in one baby because the family did not give consent. A familial history of hearing loss was present in three of four patients in whom cochlear implantation was performed. In all patients who were diagnosed as having hearing loss, the age at the time of diagnosis was below the age of three months. It was learned that hearing aids were placed at the age of four months in two patients, at the age of five months in one patient, and at the age of eight months in one patient. The ages at the time of cochlear implantation were found to be 12 months in two patients and 14 months in two patients.

Table 1.

Newborn hearing screening results

ABR: Auditory brainstem response; TEOAE: Transient evoked otoacustic emissions

Table 2.

Results of the patients who were referred to reference center

| No | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of referrals to advanced center | 62 | 0.82 |

| Those who passed the test | 31 | - |

| Those wo were lost to follow-up | 24 | - |

| Those who had hearing loss | 6 | 0.08 |

Discussion

If congenital hearing loss is not diagnosed and treated early, normal language development, speech, and social abilities are affected. Therefore, early diagnosis and intervention is essential for language and cognitive development (18). The possibility of being diagnosed in the first year of life is considerably low in babies with advanced hearing loss without a screening test (19). Vohr et al. (20) found that the mean age at the time of confirmation of permanent hearing loss was three months in babies who participated in a screening program in a study they conducted between 1993 and 1996, whereas this value was 31.25 months before screening program. Therefore, newborn hearing tests were transformed to a screening program that included all newborns rather than only babies who had increased risk in terms of hearing loss (Universal Newborn Hearing Screening, UNHS) (21). Subsequenty, the AAP 2010 and Joint Committee on Infant Hearing (JCIH) 2007 specified “1–3–6” criteria for monitoring the screening program: 1. Complete newborn hearing screening after delivery before one month, 2. Diagnose hearing loss before the age of three months, 3. Plan early intervention before six months in babies diagnosed as having hearing loss. In addition, the JCIH (2007) announced the success targets of these criteria; 95% of all newborns should be screened before the age of one month, a diagnosis should be made before the age of three months in 90% of babies who fail screening and are referred to advanced centers, hearing aid should be placed before the age of six months in 95% of the patients who are diagnosed as having permanent hearing loss.

Although the TEOAE test is used frequently in newborn hearing screenings, there are also protocols in which the TEOAE test is used in association with the ABR test or only the ABR test is used (7, 8, 14, 22, 23). In our study, we primarily used the TEOAE test in healthy newborns, an automated ABR test in babies who failed the emission test twice, and directly automated ABR test in newborns who had an increased risk in terms of hearing loss. We referred patients who failed the ABR test to advanced hearing centers for the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of hearing loss.

The incidence of congenital hearing loss is between 0.1% and 0.3% in healthy newborns. This incidence has been found to be much higher (2–4%) in newborns with increased risk (24). Many studies related with this issue have been conducted in Turkey. In the hearing screening study conducted by Genç et al. (23) in Hacettepe University with 5485 term newborns, the incidence of advanced/extremely advanced sensoryneural hearing loss was found as 0.20%. Çelik et al. (25) found this incidence as 0.27% in a much larger study involving the time period between 2005 and 2011 in Zekai Tahir Burak Women’s Health Education and Research Hospital. In the study conducted by Bolat et al. (26) in which the results of 764,352 newborns screened between 2004 and 2008 throughout Turkey were evaluated, the incidence was reported as 0.17%. According to the screening performed in different education and research hospitals in Polatlı and Istanbul, the incidence of hearing loss ranges between 0.1% and 0.15% (24, 27). In the newborns included in our study, the incidence of congenital hearing loss was found as 0.08%, which is lower compared with the literature. We think that this lower incidence may be related to the facts that the number of the newborns with increased risk of hearing loss was markedly lower in our study compared with the other studies, that some patients were lost to follow-up in different stages of the screening program, that we could not contact some patients who we referred to advanced centers following ABR, and that some patients never presented to the advanced center.

In our study, risk factors were present in 20 of 62 patients who were referred to advanced hearing centers because they failed the hearing screening test; it was found that 12 patients had a history of ototoxic drug use, three patients had hyperbilirubinemia, and five patients had a familial history of hearing loss. Hearing loss was found in six of 62 patients who were referred to advanced centers. A familial history of hearing loss was present in half of these six patients and one patient had no risk factors. The number of babies who had an increased risk of hearing loss was low in our study compared with other studies because tertiary care was not being given in the NICU in our hospital. Although consanguineous marriage is not considered a risk factor, it may be significant to it more carefully considering that its frequency is high in our country and in the region where our hospital serves, and consanguineous marriage increases the possibility of some genetic diseases that are accompanied by hearing loss. In our study, consanguineous marriage was present in two patients who had hearing loss. In studies conducted in countries where consanguineous marriage is prevalent including Turkey, Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the incidence of autosomal recessive diseases accompanied by hearing loss have been reported as high (28–32). Sajjad et al. (29) conducted a study in Pakistan with 140 students who had hearing loss and 221 students who were healthy and reported that first- and second-degree consanguineous marriage was present between the mother and father in 86.4% of the children who had hearing loss and in 59.7% who did not have hearing loss. In the study conducted by Dereköy et al. (32), consanguineous marrigae was present between the mother and father in 64 (49.2%) of 130 students who had hearing loss.

According to the AAP 2010 guideline, the rate of referral to advanced centers for comprehensive audiological assessment should be <4%. In our study, the rate of referral to advanced center following hearing screening tests was 0.6% (42 newborns) in healthy newborns and 3.4% (20 newborns) in newborns with an increased risk of hearing loss. The total rate of referral was 0.82% (62 newborns).

According to the AAP 2010 and JCIH 2007 criteria, a diagnosis should be made up to the third month in 90% of patients who are referred to advanced hearing centers and hearing aids should be placed up to the sixth month in 95% of patients who have permanent hearing loss (33). In a study conducted by Özcebe et al. (34), the mean age at the time of diagnosis was reported as 19.4 months, the mean age at the time of placing a hearing aid was 26.5 months, and the mean age at the time of cochlear implantation was 33 months between 1999 and 2004 in Turkey. In the study conducted by Yılmazer et al. (24) between 2009 and 2011 in Bakırköy Dr. Sadi Konuk Education and Research hospital, the mean age at the time of diagnosis was reported as 6.1 months, the mean age at the time of placing hearing aid was 9.5 months, and the mean age at the time of cochlear implantation was 24.5 months. In our study, the age at the time of diagnosis was found to be below three months, and the age at the time of placing a hearing aid was found to be below six months. The age at the time of cochlear implantation was found as 12 months in two of our patients and 14 months in two other patients. Although the number of patients with hearing loss was lower compared with other studies, it was observed that a significant improvement was obtained in terms of the age at the time of diagnosis, the age at the time of placing hearing aid, and the age at the time of cochlear implantation, and the AAP and JCIH targets were achieved. This shows that considerable advancement was achieved in terms of diagnosis and treatment following screening as well as successful conduction of the hearing screening program, which was initiated in the beginning of the 2000s in pilot hospitals and subsequently expanded to the whole country. We think that the marked improvement in the mean age at the time of diagnosis and treatment compared with 2011 was closely related with the increase in the number of centers where screening is performed and in the number of odiometrists, the increase in the number of advanced diagnostic and therapeutic centers for hearing loss, the number of specialist physicians interested in the issue, and with better informing of families in this issue.

The major limitation of our study was that it was a retrospective study. Therefore, the information was limited to the information recorded in the patient files. Risk factors could not be interrogated in detail in babies with an increased risk again because of the same reason.

More successful speech and language skills and better emotional, social and cognitive development are enabled with early diagnosis and treatment of congenital hearing loss. In addition to newborn hearing screening, it is important and essential to accurately and appropriately inform families of children who fail screening tests, to make the diagnosis before the age of three months in advanced centers, and to place hearing aids before the age of six months in order to achive this objective.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from the ethics committee of Taksim Gaziosmanpaşa Training and Research Hospital (08.03.2017-12).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was not obtained due to retrospective nature of this study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - S.E.A.Ö, S.A.; Design - S.E.A.Ö, S.A; Supervision - S.E.A.Ö, S.A;Funding - S.E.A.Ö, L.T.K, F.Ç., Z.M; Materials - Z.M ; Data Collection and/or Processing - S.E.A.Ö, L.T.K, F.Ç., Z.M; Analysis and/or Interpretation - S.A., S.E.A.Ö ; Literature Review - S.E.A.Ö, S.A.; Writing - S.A., S.E.A.Ö ; Critical Review - S.E.A.Ö, S.A, L.T.K, F.Ç.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Gabbard SA, Northern JL, Yoshinaga-Itano C. Hearing screening in newborns under 24 hours of age. Semin Hear. 1999;20:291–305. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1082945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kemp DT, Ryan S, Bray P. A guide to effective use of otoacoustic emissions. Ear Hear. 1990;11:93–105. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199004000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ovalı F. Fetus ve yenidoğanda işitme: temel kavramlar ve perspektifler. Turkiye Klinikleri J Pediatr. 2005;14:138–49. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham M, Cox EO. Hearing assesment in infants and children: recommendations beyond neonatal screening. Pediatrics. 2003;111:436–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White KR, Vohr BR, Behrens TR. Universal newborn hearing screening using transient evoked otoacoustic emissions: results of the Rhode Island hearing assessment Project. Semin Hear. 1993;14:18–29. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Serious hearing impairment among children aged 3–10 years. Atlanta, Georgia, 1991–1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46:1073–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hahn M, Lamprecht-Dinnesen A, Heinecke A, et al. Hearing screening in healthy newborns: feasibility of different methods with regard to test time. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1999;51:83–9. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(99)00265-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson DC, McPhillips H, Davis RL, et al. Universal newborn hearing screening: summary of evidence. JAMA. 2001;286:2000–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.16.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nekahm D, Weichbold V, Welzl-Mueller K, et al. Improvement in early detection of congenital hearing impairment due to universal newborn hearing screening. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;59:23–8. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(01)00447-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle KJ, Burggraaff B, Fujikawa S, et al. Newborn hearing screening by otoacoustic emissions and automated auditory brainstem response. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;41:111–9. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(97)00066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennedy CR, Kimm L, Dees DC, et al. Otoacoustic emissions and auditory brainstem responses in the newborn. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:1124–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.10_Spec_No.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2000 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2000;106:798–817. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White KR, Vohr BR, Behrens TR. Universal newborn hearing screening using transient evoked otoacoustic emissions: results of the Rhode Island hearing assessment project. Semin Hear. 1993;14:18–29. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorton AR, Kimm L, Kennedy CR. Methodological factors involved in neonatal screening using transientevoked otoacoustic emissions and automated auditory brainstem response testing. Hear Res. 2003;182:65–76. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(03)00173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehl AL, Thomson V. Newborn hearing screening: the great omission. Pediatrics. 1998;101:1–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.1.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Academy of Pediatrics. Task Force on Newborn and Infant Hearing. Newborn and infant hearing loss: detection and intervention. Pediatrics. 1999;103:527–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.2.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolat H, Genc GA. Türkiye ulusal yenidoğan işitme taraması programı: tarihçesi ve prensipleri. Türkiye Klinikleri J ENT-Special Topics. 2012;5:11–4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verhaert N, Willems M, Van Kerschaver E, et al. Impact of early hearing screening on language development and education level: evaluation of 6 years of universal hearing screening in Flanders-Belgium. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72:599–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu K, Elimian A, Barbera J, et al. Antecedents of newborn hearing loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:584–8. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)03118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vohr BR, Oh W, Stewart EJ, et al. Comparison of cost and referral rates of three universal newborn hearing screening protocols. J Pediatr. 2001;139:238–44. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.115971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erenberg A, Lemons J, Sia C, et al. American Academy of Pediatrics task force on newborn and infant hearing. Newborn and infant hearing loss: detection and intervention. Pediatrics. 1999;103:527–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.2.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatzopoulos S, Pelosi G, Petrucelli J, et al. Efficient otoacoustic emission protocols employed in a hospital-based neonatal screening program. Acta Otolaryngol. 2001;121:269–73. doi: 10.1080/000164801300043802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Genç GA, Başar F, Kayıkçı ME, et al. Hacettepe Üniversitesi yenidoğan işitme taraması bulguları. Çocuk Sağlığı ve Hastalıkları Dergisi. 2005;48:119–24. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yılmazer R, Yazıcı MZ, Erdim İ, et al. Follow-up results of newborns after hearing screening at a training and research hospital in Turkey. J Int Adv Otol. 2016;12:55–60. doi: 10.5152/iao.2015.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Çelik İH, Canpolat FE, Demirel G, et al. Zekai Tahir Burak Women’s Health Education and Research Hospital newborn hearing screening results and assessment of the patients. Turk Pediatri Arch. 2014;49:138–41. doi: 10.5152/tpa.2014.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolat H, Bebitoglu FG, Ozbas S, et al. National newborn hearing screening program in Turkey: struggles and implementations between 2004 and 2008. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1621–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renda L, Özer E, Renda R. Ankara Polatlı Devlet Hastanesi yenidoğan işitme taraması programı: 6 yıllık sonuçlar. Pam Tıp Derg. 2012;5:123–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ant A, Karamert R, Bayazıt YA. İşitme kayıplarının genetik yönü ve Türkiye’deki görünümü. Türkiye Klinikleri J ENT-Special Topics. 2012;5:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sajjad M, Khattak AA, Bunn JE, et al. Causes of childhood deafness in Pukhtoonkhwa Province of Pakistan and the role of consanguinity. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122:1057–63. doi: 10.1017/S0022215108002235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zakzouk S. Consanguinity and hearing impairment in developing countries: a custom to be discouraged. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116:811–6. doi: 10.1258/00222150260293628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khabori MA, Patton MA. Consanguinity and deafness in Omani children. Int J Audiol. 2008;47:30–3. doi: 10.1080/14992020701703539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dereköy FS. Etiology of deafness in Afyon school for the deaf in Turkey. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;55:125–31. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(00)00390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Busa J, Harrison J, Chappell J, et al. Year 2007 position statement: principles and guidelines for early detecting and intervention programs. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2007;120:898–921. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozcebe E, Sevinc S, Belgin E. The ages of suspicion, identification, amplification and intervention in children with hearing loss. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:1081–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]