Abstract

Mentha piperita L. essential oil (EO) is employed for external use as antipruritic, astringent, rubefacient and antiseptic. Several studies demonstrated its significant antiviral, antifungal and antibacterial properties. The aim of this work is the study of the synergistic effects of M. piperita EO with antibacterials and antifungals that are widely available and currently prescribed in therapies against infections. The observed strong synergy may constitute a potential new approach to counter the increasing phenomenon of multidrug resistant bacteria and fungi. In vitro efficacy of the association M. piperita EO/drugs was evaluated against a large panel of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and yeast strains. The antimicrobial effects were studied by checkerboard microdilution method. The synergistic effect of M. piperita EO with gentamicin resulted in a strong growth inhibition for all the bacterial species under study. The synergistic effect observed for M. piperita EO and antifungals was less pronounced.

Introduction

Bacterial resistance to antibiotic therapy is a growing emergency [1]. In the last years, several research programs have focused on designing new compounds possessing potential antimicrobial activity in order to avoid this problem [2–6]. New sources, especially plant-derived antimicrobial compounds, have been extensively studied in recent years [7,8].

Plant essential oils (EOs) have been examined in detail for their pharmacological properties and may constitute a promising source for new natural drugs [9–14]. Currently, approximately 3000 EOs are known of which 300 are commercially available in the agronomic, alimentary, sanitary and pharmaceutical fields [15–19]. Plant-derived EOs are natural mixtures of a certain complexity. At times, they may contain more than 100 components at quite different concentrations. These components encompass two groups of distinct biosynthetic origin: the main group includes terpenes and terpenoids, while the other one includes aromatic and aliphatic constituents with low molecular weight [20]. Plausibly, the presence of all these compounds in the EOs explains the absence of microbial resistance or adaptation to their pharmacological properties. Thus, EOs constitute an effective alternative or complementary therapy to synthetic compounds, without manifesting the same side effects [21].

Properties and uses of M. piperita L.

M. piperita L. (Lamiaceae) is used as raw material in several different applications in foods and cosmetics; leaves and flowers are used for medicinal preparations [22].

M. piperita EO is used in perfume industry, cosmetics, aromatherapy, spices, nutrition, etc. Several studies have shown the antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal properties and antioxidant activities of EOs and of the extract of the herbal parts of M. piperita obtained through different preparative procedures [23]. As the chemical profile of M. piperita EO depends on both the method used for the extraction and the amount of molecules extracted, it is very difficult to establish which specific biological target is responsible for the action. The biological profile of the EO may be the result of a synergistic action of all the molecules contained in the EO or it may reflect only the activity of the main molecules.

Chemical composition and potential therapeutic applications of M. piperita L. EO

The content of EOs can be detected by hyphenated gas chromatography with mass spectrometry (GC/MS) technique [24,25]. M. piperita EO is composed by monoterpenes, menthone, menthol and their derivatives. Several authors have underlined the role of EOs in the management of several therapeutic conditions, as inflammation of the oral mucosa, irritable colon, spastic discomfort of the upper gastrointestinal tract and bile ducts, catarrhs of the respiratory tract. A therapeutic approach based on a combination of drugs could contribute to overcoming antibiotic resistance [26–28].

Recently, we assessed and reported the positive synergism against Candida spp. of the echinocandin anidulafungin combined with aspirin or with other NSAIDs [29,30]. All these observations prompted us to investigate the combination of commercially available M. piperita EO with well-known synthetic antimicrobials, with the aim of providing a greater effectiveness to combat infections and overcome the phenomenon of drug resistance [31–35].

Aims of research

Gentamicin and ampicillin were chosen as antibacterial agents, while amphotericin B was chosen as antifungal. Gentamicin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic largely used for the treatment and prevention of severe Gram-negative bacterial infections. However, its severe side effects (oto- and nephrotoxicity) limit its use. In addition, psychiatric symptoms related to gentamicin (confusion, anorexia, depression, disorientation and visual hallucinations) may occur.

Ampicillin is a β-lactam antibiotic that showed several side effects. Recently, an increased resistance to this antibiotic has been reported [36].

Amphotericin B is a polyene antifungal drug which is considered the drug of choice for the treatment of mycosis; it is often combined with azoles. However, several authors have observed that in the last decades Candida species have become resistant to treatment to azoles alone and to azoles in association with amphotericin B [37].

In the class of azoles, fluconazole and miconazole were chosen for the association with M. piperita EO. Regarding all this, the aim of the present study was to examine the possible synergistic effect of M. piperita EO with common antimicrobials.

We recently reported the in vitro synergistic activity of certain combinations of essential oils with antimicrobials [38–40]. The antimicrobial activity of the M. piperita EO against different Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and fungi, along with its synergistic effects when combined with antimicrobial drugs (gentamicin, ampicillin, amphotericin B, miconazole and fluconazole), has been studied by following the microdilution checkerboard method. The composition of commercially available M. piperita EO used in our experiments has been confirmed by GC/MS analyses [41–45].

Materials and methods

Microorganisms

Ten bacterial strains from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) were used for tests: Bacillus cereus ATCC 10876, Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538p, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 43300 (MRSA), Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 19883, Acinetobacter baumanni ATCC 19606, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853. Seven Candida species from ATCC were used for antifungal tests: Candida albicans ATCC 10231, Candida albicans ATCC 24433, Candida albicans ATCC 90028, Candida guilliermondii ATCC 6260, Candida glabrata ATCC 15126, Candida krusei ATCC 14243, Candida kefyr ATCC 204093.

Microbial and yeast cultures

The bacterial species were cultured on Mueller Hinton agar (MHA, Oxoid) and each bacterial suspension was composed of 2–3 colonies for each strain taken from an MHA plate and dissolved in 2 mL of MHB (Mueller Hinton Broth). The resulting suspensions were diluted with 0.85% NaCl solution and then adjusted to 1x108 CFU/mL (0.5 McFarland).

The fungal strains were subcultured twice on Sabouraud dextrose agar before being tested. Yeast cells were washed four times in sterile saline. Each fungal suspension was taken from its frozen stock at –70°C. The strains were inoculated in 5 mL of Sabouraud dextrose broth, and then incubated under stirring at 35°C for 48 h.

MIC evaluation protocols

MIC values were determined by broth microdilution method, in accordance with CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute) Protocol M07-A9 guidelines for bacteria and Protocol M27-A3 guidelines for yeasts [46,47].

Antimicrobial activity

For antibacterial tests, a stock solution (EO/Ethanol 1:2.5, 40% v/v with Tween 80, 0.1%) was diluted 1:20 in MHB to obtain a 2% (v/v) final solution. Doubling dilutions of the EO from 2% to 0.015% for EO were prepared directly in 96 well microtiter trays in MHB. After the addition of 0.02 mL of the inoculum, the microtiter trays were incubated at 36°C for 24 h. The final concentration of ethanol was 1.5% (v/v). The MHB medium 0.1% (v/v) Tween 80 and ethanol 1.5%, (without EO) was used as a positive growth control.

Preparation of the EO for the antifungal tests followed the same procedure as the one for the antibacterial tests. A small quantity of inoculum was dissolved in RPMI 2% glucose and then spectrophotometrically adjusted to 0.5 x 103 to 2.5 x 103 CFU/mL (McFarland, turbidity standard). The initial inocula were confirmed by plating serial dilutions and determining the colony counts. A total of 0.1 mL of each yeast suspension was dispensed into serially diluted wells containing the drugs or the EO, achieving final drug concentration. After the addition of 0.1 mL of inoculum, the plates were incubated at 36°C for 48 h. MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the mixtures at which no visible growth of the fungal strains could be detected compared to their growth in the negative control well. MIC values are given in mg/mL and μg/mL for M. piperita EO and antimicrobial drugs, respectively.

MIC determinations were realized in triplicate in three independent assays.

FICI determination

MIC data of the antimicrobial compounds and M. piperita EO were converted into Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC), determined using the formula FIC = (MICAcombination/MICAalone). MIC values for the EO-drugs associations were defined as the lowest concentration at which no visible growth of the microbial strains could be detected compared to their growth in the control well, as described in Eucast document [48].

Microdilution checkerboard method

In the combination assays, the checkerboard procedure described by White et al. [49] was followed to evaluate the synergistic action of the EO with selected drugs. Twelve double serial dilutions of the EO were prepared following the same method used to evaluate the MIC. Dilutions of the EO were prepared together with a series of double dilutions of the antimicrobial drugs: for antifungal drugs in the range of 32.0–0.66 μg/mL, for antibacterial in the range of 64.0–0.125 μg/mL and for M. piperita EO in the range of 18.2–0.09 mg/mL.

This method was used to mix each antimicrobial compounds dilution with the appropriate concentrations of EO in order to obtain a series of concentration combinations of the EO with each particular drug. In our experimental protocol, the substance combinations were analysed by calculating the FIC index (FICI) as follows: FIC of the EO plus FIC of the drug. Generally, the FICI value was interpreted as: i) a synergistic effect when ≤ 0.5; ii) an additive or indifferent effect when > 0.5 and <1; iii) an antagonistic effect when > 1 [49]. The concentrations prepared accounted for 40%, 20%, 10%, and 5% of the MIC value for the EO, and 25%, 12.5%, 6.25%, 3.12% of the MIC value for the antibiotic. Also, the combination of two components is shown graphically in a Cartesian diagram by applying the isobole method. The non-interaction of the two components results in a straight line, whereas the occurrence of an interaction is shown by a concave isobole [50–53].

Chemicals and materials

Antifungal and antibacterial agents Gentamicin, Ampicillin, Amphotericin B, Miconazole and Fluconazole were purchased from Sigma S.r.l. (Milan, Italy). Commercially available pure M. piperita EO (Lot 140/0000324, 10.2018, 10 mL) was provided by Erbenobili S.r.l. (Corato, Bari,—Italy). C7-C30 alkanes mixture and solvents, all of analytical grade, were purchased from Sigma Aldrich S.r.l. (Milan, Italy), filters were supplied by Agilent Technologies Italia S.p.a. (Milan, Italy).

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry equipment

The gas chromatographic analyses have been performed on HP GC/MS 6890N-5973N MSD HP ChemStation equipped with autosampler and HP-5MS column (crosslinked 5% PH ME siloxane) 30 m x 0.25 mm x 0.25 μm Film Thickness. The following temperature program was applied: 40°C (4 min), 4°C per minute heating up to 280°C (30 min). The mass spectrometer was operated in EI mode at 70 eV; the ion source temperature was 220°C. The mass spectra were measured in the range of 35–360 amu.

Compound identification

For chemical characterization, a standard solution of 100 μL of the pure EO in 1 mL of ethyl acetate was prepared. The solution was filtered and 1 μL was analyzed by GC/MS. The sample was analyzed in triplicate. Qualitative analysis was executed comparing the calculated Linear Retention Indices (LRI) and Similarity Index Mass Spectra (SI/MS) for the obtained peaks with the analogous data from NIST2011 and Adams 4th ed. (2007) databases. LRI of each compound was obtained by temperature programming analysis and was determined in relation to an homologous series of n-alkanes (C7–C30) under the same operating conditions. LRI was calculated following the Van den Dool and Kratz equation [24,25,45,54] and compared with the Arithmetic Index (AI) from NIST2011 database and Adams, 4th ed. (Adams 2007). SI/MS were determined as reported by Koo et al. [55]. Component relative percentages were calculated on the basis of GC peak areas without using correction factors.

Results and discussion

The present research has tested M. piperita EO in association with several antifungal and antibacterial drugs. The effects have been evaluated on ten strains of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and seven strains of Candida spp. FICI values for M. piperita EO in combination with antibacterial agents as gentamicin and ampicillin are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Mentha piperita EO and antibacterial drugs–fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) and FIC indices (FICI).

| Gentamicin | Ampicillin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MICo | MICc | FIC | FICI | MICo | MICc | FIC | FICI | |

| Bacillus cereus ATCC 10876 | ||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 2.00±0.58 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 1.00±0.48 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 4.55±1.32 | 0.23±0.13 | 0.05 | 4.55±1.32 | 1.82±0.79 | 0.40 | ||

| Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 | ||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 0.50±0.48 | 0.01±0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.12±0.08 | 0.01±0.02 | 0.08 | 0.13 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 4.55±1.32 | 0.23±0.13 | 0.05 | 4.55±1.32 | 0.23±0.13 | 0.05 | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538p | ||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 2.0±0.58 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.03 | 0.103 | 0.12±0.08 | 0.03±0.02 | 0.24 | 0.44 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 9.10±2.63 | 0.91±0.39 | 0.10 | 9.10±2.63 | 1.82±0.79 | 0.20 | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 | ||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 0.5±0.58 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 1.0±0.29 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 4.55±2.63 | 0.46±0.12 | 0.10 | 4.55±2.63 | 1.82±0.79 | 0.4 | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 43300 | ||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 8.0±2.31 | 2.0±0.58 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 8.0±2.31 | 2.0±0.58 | 0.25 | 0.65 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 9.10±2.63 | 0.46±0.12 | 0.05 | 9.10±2.63 | 3.64±1.05 | 0.40 | ||

| Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 | ||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 8.0±2.31 | 1.0±0.29 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 1.0±0.48 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 9.10±2.63 | 1.82±0.79 | 0.20 | 9.10±2.63 | 3.64±0.66 | 0.40 | ||

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | ||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 1.0±0.48 | 0.03±0.02 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 16.0±4.62 | 4.0±2.31 | 0.50 | 0.55 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 9.10±2.63 | 3.64±1.05 | 0.40 | 9.10±2.63 | 2.27±0.66 | 0.05 | ||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 19833 | ||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 32.0±9.24 | 1.0±0.29 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 16.0±4.62 | 4.0±2.31 | 0.25 | 0.50 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 9.10±2.63 | 3.64±1.05 | 0.40 | 9.10±2.63 | 2.27±0.66 | 0.25 | ||

| Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606 | ||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 8.00±2,31 | 0.5±0.14 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 16.0±4.62 | 4.0±2.31 | 0,25 | 0,50 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 9.10±2.63 | 3.64±1.05 | 0.40 | 9.10±2.63 | 2.27±0.66 | 0.25 | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | ||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 2.00±0.58 | 0.06±0.01 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 16.0±4.62 | 4.0±2.31 | 0.23 | 0.50 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 9.10±2.63 | 0.46±1.05 | 0.05 | 9.10±2.63 | 2.27±0.98 | 0.23 | ||

MICo ± S.E.M. = MIC of an individual sample; MICc ± S.E.M. = MIC of an individual sample at the most effective combination; FIC = fractional inhibitory concentration; FICI = FIC of antibiotic + FIC of M. piperita EO.

FICI values for the association with gentamicin and ampicillin were, respectively, in the range of 0.07–0.46 and 0.13–0.65 against all tested bacterial strains. It is also interesting to underline that the MIC value for gentamicin is markedly reduced when combined with M. piperita EO, as the MIC value for this particular association was found to be more than 30-fold lower against six out of the ten bacteria strains considered. The most interesting result was obtained for Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 for which the MIC value of gentamicin was found to have decreased from 0.5 to 0.01 μg/mL (FICI = 0.07). Moreover, a promising result was obtained also against Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606, a Gram-negative bacillus resistant to treatment with gentamicin alone. In this case, a 16-fold reduction of gentamicin MIC (FICI = 0.46) was observed when used with M. piperita EO. The strong synergy observed between gentamicin and the EO against the Gram-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 19833 is worthy of note. In particular, the MICc value for gentamicin is much lower than that normally required to achieve the direct inhibition of bacterial growth (MICc: 0.06 μg/mL vs MICo: 2 μg/mL, MICc: 1 μg/mL vs MICo: 32 μg/mL). Associations of ampicillin with M. piperita EO showed a marked synergistic effect against Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 (FICI = 0.08) and Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 (FICI = 0.13). Results for the associations with antifungals are reported in Table 2.

Table 2. Mentha piperita EO and antifungal drugs–fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) and FIC indices (FICI).

| Amphotericin B | Fluconazole | Miconazole | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candida Strains (ATCC) | MICo | MICc | FIC | FICI | MICo | MICc | FIC | FICI | MICo | MICc | FIC | FICI |

| Albicans ATCC 10231 | ||||||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 1.00±0.29 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 1.00±0.29 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 2.00±0.58 | 0.13±0.04 | 0.06 | 0.46 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 2.28±1.30 | 0.91±0.26 | 0.40 | 2.28±1.30 | 0.91±0.26 | 0.40 | 2.28±1.30 | 0.91±0.26 | 0.40 | |||

| Albicans ATCC 24433 | ||||||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 1.00±0.58 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 1.00±0.29 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 2.00±0.58 | 0.12±0.03 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 2.28±1.30 | 0.91±0.26 | 0.40 | 2.28±1.30 | 0.91±0.26 | 0.40 | 2.28±1.30 | 0.23±0.07 | 0.10 | |||

| Albicans ATCC 90028 | ||||||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 1.00±0.29 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 1.00±0.29 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 1.00±0.29 | 0.40±0.30 | 0.40 | 0.46 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 2.28±1.30 | 0.91±0.26 | 0.40 | 2.28±1.30 | 0.91±0.26 | 0.40 | 2.28±1.30 | 0.14±0.33 | 0.06 | |||

| Guilliermondii ATCC 6260 | ||||||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 1.00±0.29 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 2.28±1.30 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 0.50±0.14 | 0.10±0.03 | 0.20 | 0.25 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 2.28±0.66 | 0.91±0.26 | 0.40 | 2.28±1.30 | 0.91±0.26 | 0.40 | 2.28±0.66 | 0.12±0.03 | 0.05 | |||

| Glabrata ATCC 15126 | ||||||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 2.00±0.58 | 0.50±0.14 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 16±4.620 | 1.00±0.29 | 0.06 | 0.47 | 1.00±0.29 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 1.14±0.66 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.05 | 1.14±0.66 | 0.46±0.45 | 0.40 | 1.14±0.66 | 0.46±0.35 | 0.40 | |||

| Krusei ATCC 6258 | ||||||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 1.00±0.29 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 16±4.620 | 1.00±0.29 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 1.00±0.29 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 4.54±1.30 | 1.82±1.05 | 0.40 | 4.54±1.30 | 1.82±1.05 | 0.40 | 4.54±1.30 | 1.82±1.05 | 0.40 | |||

| Kefyr ATCC 204093 | ||||||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 2.00±0.5 | 0.12±0.03 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 2.28±1.30 | 0.25±0.08 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 0.50±0.14 | 0.03±0.05 | 0.06 | 0.46 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 4.54±1.30 | 1.82±1.05 | 0.40 | 4.54±1.30 | 1.82±1.05 | 0.40 | 4.54±1.30 | 1.82±1.05 | 0.40 | |||

| Parapsilosis ATCC 22019 | ||||||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 1.00±0.58 | 0.03±0.05 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 1.00±0.29 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 2.00±0.58 | 0.13±0.04 | 0.06 | 0.46 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 2.28±1.30 | 0.12±0.03 | 0.40 | 2.28±1.30 | 0.91±0.26 | 0.40 | 2.28±1.30 | 0.91±0.26 | 0.40 | |||

| Tropicalis ATCC 750 | ||||||||||||

| Drug (μg/ml) | 2.00±0.50 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 1.00±0.29 | 0.06±0.02 | 0.06 | 0.46 | 2.00±0.58 | 0.12±0.03 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

| EO (mg/ml) | 4.54±1.30 | 0.91±0.26 | 0.40 | 2.28±1.30 | 0.91±0.26 | 0.40 | 2.28±1.30 | 0.23±0.07 | 0.10 | |||

MICo ± S.E.M. = MIC of an individual sample; MICc ± S.E.M. = MIC of an individual sample at the most effective combination; FIC = fractional inhibitory concentration; FICI = FIC of antifungal + FIC of M. piperita EO.

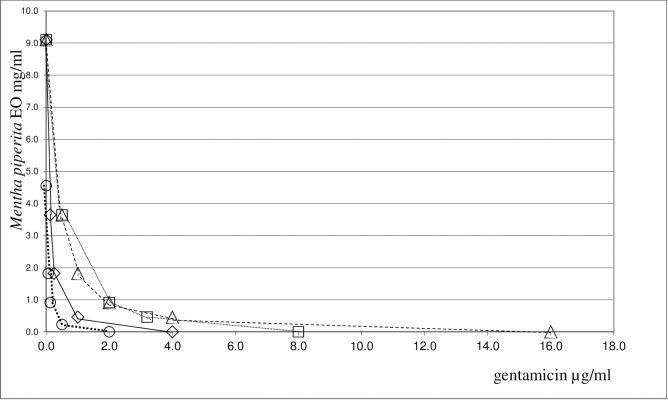

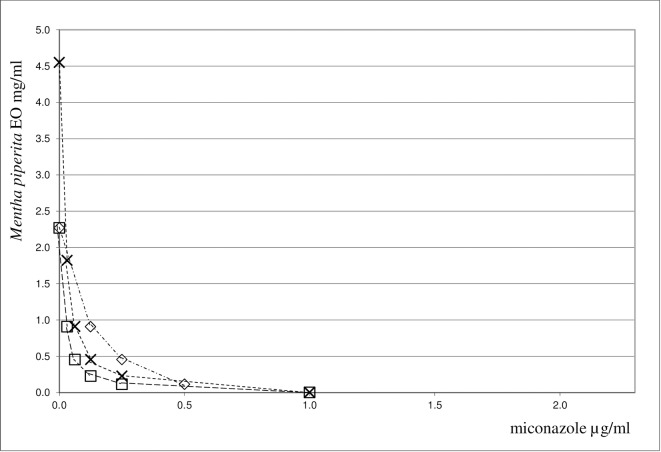

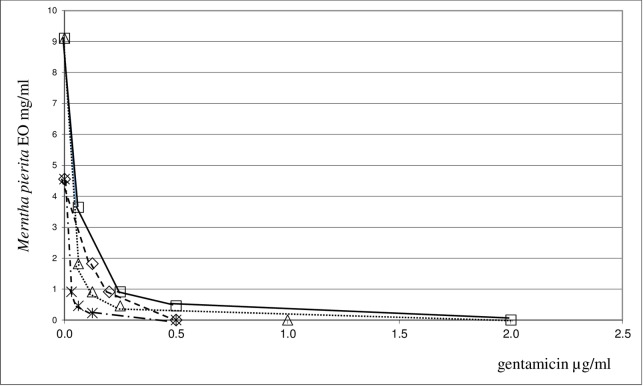

A synergistic antifungal action was observed when M. piperita EO was combined with fluconazole, amphotericin B or miconazole against yeast strains under study. FICI values close to 0.4 were found for amphotericin B and fluconazole, whereas they ranged between 0.23 and 0.46 for miconazole. It is interesting to note that this association had a strong synergistic effect against the C. albicans and C. guilliermondii spp.. On the whole, the synergistic antimicrobial action demonstrated by combining M. piperita EO with antifungals was less pronounced against yeast strains than that of antibacterial agents combined with the same EO against bacteria strains. The synergistic interaction between M. piperita EO and the most promising antimicrobials, gentamicin and miconazole, is shown in Figs 1–3.

Fig 1. Isobole curves revealing the synergistic effect of Mentha piperita EO with gentamicin in inhibiting four bacterial strains.

◇ P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, □ E. faecalis ATCC 29212, △ K.pneuomoniae ATCC 13883, ○ B.cereus ATCC 10876.

Fig 3. Isobole curves revealing the synergistic effect of Mentha piperita EO with miconazole in inhibiting three yeast strains.

□ Candida albicans ATCC 90028, × Candida krusei, ◇ Candida albicans ATCC 10231.

Fig 2. Isobole curves revealing the synergistic effect of Mentha piperita EO with gentamicin in inhibiting four bacterial strains.

Δ E. coli ATCC 25922, ✳ S. aureus ATCC 29213, ◇ B. subtilis ATCC 6633, □ S. aureus ATCC 6538P.

The combination of the two components is shown by an isobole method [50]. An isobole is an “iso-effect” curve, in which a combination of constituents is represented on a graph, whose axises represent the inhibitory doses of the individual agents. If the agents do not interact, the isobole (the line joining the points representing the combination to the points on the dose axises representing the individual doses with the same effect as the combination) will be a straight line. If the effect is additive, the curve of the isobole will be a “concave” line, thus indicating that the agents in the mixture are synergic. When the opposite occurs, a “convex” line will result, showing antagonism. In other words, the same biological effects of the isolated agents are obtained at lower (or higher) doses than those observed for the mixture. Our graphs indicate, indeed, a high synergism against all the bacteria and yeast strains examined. The synergistic or antagonistic relationship between antimicrobials may result from competition for a possible primary target [56]. Conversely, a synergistic multi-target effect may occur, involving enzymes, substrates, metabolites and proteins, receptors, ion channels, transport proteins, ribosomes, DNA/RNA and physicochemical mechanisms [40]. An alternative explanation may be that the interaction between different compounds may lead to changes in the structural conformation, and it may result in the reduction of the inhibitory activity. However, it is difficult to elucidate the exact mechanism of the synergistic effect without further investigation. In order to assess the impact of M. piperita EO in association with antimicrobials we evaluated the chemical composition of this EO by GC/MS analysis. For the chemical characterization of the commercially available EO used for the biological assay, GC/MS analysis were performed [42,43]. 27 components have been identified in the pure EO, 20 of which corresponded to 97.64% of the mixture. Menthol was found to be the major component, amounting to 68% of the mixture. The composition of the EO has been summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Chemical composition of essential oil of Mentha piperita.

| Compound | Area % ± SEM | Library/ID | LRI | AI | SI/MS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.73 ± 0.23 | α-Pinene | 930 | 932 | 97 |

| 2 | 0.22 ± 0.012 | Sabinene | 965 | 969 | 91 |

| 3 | 0.72 ± 0.22 | β-Pinene | 968 | 974 | 90 |

| 4 | 0.40 ± 0.32 | β-Myrcene | 988 | 988 | 79 |

| 5 | 1.85 ± 0.31 | Limonene | 1024 | 1024 | 99 |

| 6 | 0.20 ± 0.021 | Eucalyptol | 1025 | 1026 | 98 |

| 7 | 0.17 ± 0.035 | Linalool | 1094 | 1095 | 72 |

| 8 | 1.35 ± 0.34 | Isopulegol | 1143 | 1145 | 98 |

| 9 | 9.48 ± 0.72 | Menthone | 1149 | 1148 | 95 |

| 10 | 8.36 ± 0.98 | Isomenthone | 1158 | 1158 | 97 |

| 11 | 67.98 ± 1.53 | Menthol | 1165 | 1167 | 91 |

| 12 | 0.46 ± 0.21 | α-Terpineol | 1187 | 1186 | 72 |

| 13 | 0.40 ± 0.17 | Pulegone | 1233 | 1233 | 97 |

| 14 | 0.49 ± 0.23 | 2-Hexenyl isovalerate | 1243 | 1241 | 90 |

| 15 | 0.85 ± 0.16 | Piperitone | 1251 | 1249 | 96 |

| 16 | 2.37 ± 0.61 | Menthyl acetate | 1291 | 1294 | 91 |

| 17 | 0.23 ± 0.17 | β-Bourbonene | 1377 | 1387 | 93 |

| 18 | 0.58 ± 0.16 | β-Caryophyllene | 1404 | 1417 | 99 |

| 19 | 0.69 ± 0.15 | Germacrene | 1467 | 1484 | 96 |

| 20 | 0.11 ± 0.022 | β-Germacrene | 1548 | 1559 | 80 |

| 97.64 |

RT: Retention Time on HP-5MS column. LRI: Linear Retention Index on HP-5MS column, experimentally determined using homologous series of C7-C30 alkanes. AI: Arithmetic Index (Adams, 2007) SI/MS: Similarity Index/Mass Spectrum (NIST, 2011 Database)

Several constituents fell within the terpene fraction: isomenthone 9.48%; menthone 8.36%; limonene 1.85%. These results are in agreement with those previously reported for EOs of different M. piperita species [37]. Conceivably, the antibacterial activity, as well as the synergistic effect of EO, may be attributed to the high percentage of oxygenated monoterpenes, which represent the major components of the EO. Trombetta et al. [57] demonstrated that monoterpenes contained in the EOs interact with model membranes and that their antimicrobial effect may be attributed to a damage sustained by the microbial lipid membrane fraction. The Gram-negative outer membrane has a strong negative charge conferred to it by the lipopolysaccharide, which is connected to lipid composition and to the net surface charge of the microbial membrane. The lower synergistic effect observed on yeasts may be attributed to a negative interaction with the antifungal drugs.

Conclusions

This paper describes a study regarding the association of M. piperita EO with several antimicrobial agents against a large panel of bacteria and fungi strains. Gentamicin and ampicillin were chosen as antibacterial agents, whereas amphotericin B, fluconazole and miconazole were chosen as antifungals. On the whole, a synergism between M. piperita EO and antimicrobials was found. The FIC indices for the association of gentamicin and M. piperita EO indicate, indeed, a very strong synergistic mode of action for all tested Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains. As a consequence, the combination of these two compounds allows for a significant reduction of the amount of gentamicin needed to inhibit bacteria strains. For example, a 33-fold reduction for gentamicin for Bacillus cereus ATCC 10876 (FICI = 0.08), a 50-fold reduction for Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 (FICI = 0.07) and 4-fold reduction for Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 43300 (methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus) (FICI = 0.30) were observed. Mixtures of ampicillin and M. piperita EO show marked synergistic effects against Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 (FICI = 0.08) and Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 (FICI = 0.13). Conversely, no evident synergistic effect was observed for ampicillin (FICI = 0.55) against Gram-negative strains as Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 19833, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853. The results against Gram-negative bacteria as Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are of particular interest as these bacteria are difficult to treat with commonly employed antibacterial drugs. Generally, a synergistic effect was also observed against yeast strains, although it was less evident than against bacteria. This result may conceivably depend on the poor interaction between the EO with azoles and amphotericin B. Further investigation would allow a more complete understanding of the antimicrobial potential of this association and may be useful for the preparation of new agents for the cure of infections caused by these important pathogens.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Robin Libero Carbonara for his professional editing service in reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Fondo di Ateneo: Università degli Studi di Bari, 2014. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Davis S. Infections and the rise of antimicrobial resistance. Vol 2. Chief medical officer annual report; 2011.

- 2.Rosato A, Piarulli M, Schiavone BPI, Catalano A, Carocci A, Carrieri A, et al. In vitro effectiveness of anidulafungin against Candida sp. biofilms. J Antibiot 2013; 66(12):701–704. 10.1038/ja.2013.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parisi OI, Fiorillo M, Caruso A, Cappello AR, Saturnino C, Puoci F, et al. Enhanced cellular uptake by "pharmaceutically oriented devices" of new simplified analogs of Linezolid with antimicrobial activity. Int J Pharmacol. 2014; 461(1–2):163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catalano A, Carocci A, Defrenza I, Muraglia M, Carrieri A, Van-Bambeke F, et al. 2-Aminobenzothiazole derivatives: search for new antifungal agents. Eur J Med Chem. 2013; 64:357–364. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.03.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Defrenza I, Catalano A, Carocci A, Carrieri A, Muraglia M, Rosato A, et al. 1,3-Benzothiazoles as antimicrobial agents. J Heterocycl Chem. 2015; 52(6):1705–1712. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armenise D, Carocci A, Catalano A, Muraglia M, Defrenza I, De Laurentis N, et al. Synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of a new series of N-1,3-benzothiazol-2-ylbenzamides, J Chem. 2013; Article ID 181758, 7 pages. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avato P, Raffo F, Guglielmi G, Vitali C, Rosato A Extracts from St. John’s Worth and their antimicrobial activity. Phytother Res. 2004; 18(3):230–232. 10.1002/ptr.1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avato P, Bucci R, Tava A, Vitali C, Rosato A, Bialy Z, et al. Antimicrobial activity of saponins from Medicago spp.: structure-activity relationship. Phytother Res. 2006; 20(6):454–457. 10.1002/ptr.1876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silva J, Abebe W, Sousa SM, Duarte VG, Machado MIL, Matos FJA (2003) Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of essential oils of Eucalyptus. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003; 89(2–3):277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaaban HAE, El-Ghorab AH, Shibamoto T. Bioactivity of essential oils and their volatile aroma components: Review. J Essent Oil Res. 2012; 24:203–212. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raut JS, Karuppayil SM. A status review on the medicinal properties of essential oils. Ind Crops Prod. 2014; 62:250–264. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lis-Balchin M (2006) Aromatherapy Science–A guide for healthcare professionals, Pharmaceutical press: London. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giamperi L, Fraternale D, Ricci D. The in vitro action of essential oils on different organisms. J Essent Oil Res. 2002; 14:312–318. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollini M, Sannino A, Paladini F, Sportelli MC, Picca RA, Cioffi N, et al. Combining Inorganic Antibacterial Nanophases and Essential Oils: Recent Findings and Prospects In: Rai M.; Zacchino S.; Derita M (Eds.), Essential Oils and Nanotechnology for Treatment of Microbial Diseases for CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, (2017) ISBN: 9781138630727. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nerio LS, Verbal JO, Stashenko E. Repellent activity of essential oils: A review. Biores Technol. 2010; 101(1):372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakkali F, Averbeck S, Averbeck D, Idaomar M. Biological effects of essential oils–A review. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008; 46(2):446–475. 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bilia AR, Guccione C, Isacchi B, Righeschi C, Firenzuoli F, Bergonzi MC. Essential oils loaded in nanosystems: a developing strategy for a successful therapeutic approach. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014; Article ID 651593, 14 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18.Inouye S, Takizawa T, Yamaguchi H. Antibacterial activity of essential oils and their major constituents against respiratory tract pathogens by gaseous contact. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001; 47(5):565–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carvalho IT, Estevinho BN, Santos L. Application of microencapsulated essential oils in cosmetic and personal healthcare products–a review. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016; 38(2):109–119. 10.1111/ics.12232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Croteau R, Kutchan TM, Lewis NG (2000) Natural products (secondary metabolites) In: Buchanan B.; Gruissem W.; Jones R. (Eds.), Biochemistry and molecular biology of Plants. American Society of Plant Physiologist. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carson CF, Riley TV. Non-antibiotic therapies for infectious diseases. Commun Dis Intell. 2003; S143–S146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKay DL, Blumberg JB. A review of the bioactivity and potential health benefits of peppermint tea (Mentha piperita L.). Phytother Res. 2006; 20(8):619–633. 10.1002/ptr.1936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saharkhiz MJ, Motamedi M, Zomorodian K, Pakshir K, Miri R, Hemyari K. Chemical composition, antifungal and antibiofilm activities of the essential oil of Mentha piperita L., Int Schol Res Net Pharm. 2012; Article ID 718645, 6 pages [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams RP (2007) Identification of Essential Oils components by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Allured Publishing Corporation. ISBN: 9781932633214. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosato A, Maggi F, Cianfaglione K, Conti F, Ciaschetti G, Rakotosaona R. et al. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of seven uncommon essential oils. J Essent Oil Res. 2018; 30:4, 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoon SY, Eo SK, Lee DK, Han SS. Antimicrobial activity of Ganoderma lucidum extract alone and in combination with some antibiotics. Arch. Pharm. Res. 1994; 17(6):438–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin S, Kang CA. Antifungal activity of the essential oil of Agastache rugosa Kuntze and its synergism with Ketoconazole. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2003; 36(2):111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin S, Lim S. Antifungal effects of herbal essential oils and in combination with ketoconazole against Trichopyton spp. J Appl Microbiol. 2004; 97(6):1289–1296. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02417.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosato A, Catalano A, Carocci A, Carrieri A, Carone A, Caggiano G, et al. In vitro interactions between anidulafungin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on biofilms of Candida spp. Bioorg Med Chem. 2016; 24(5):1002–1005. 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biavatti MW. Synergy: an old wisdom, a new paradigm for pharmacotherapy. Br J Pharm Sci. 2009; 45(3):371–378. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner H, Ulrich-Merzenich G. Synergy research: approaching a new generation of phytopharmaceuticals. Phytomedicine. 2009; 16(2–3):97–110. 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bidlack WR, Omaye ST, Meskin MS, Topham D. Phytochemicals as bioactive agents, 106–110. Lancaster, UK, Technomic Publishing Company, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosato A, Vitali C, Piarulli M, Mazzotta E, Mallamaci R. In vitro synergic efficacy of the combination Nystatin essential oils against some Candida species. Phytomedicine. 2009; 16(10):972–975. 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox SD, Mann M, Markham JL, Bell JE, Gustafson JE, Warmington JR, et al. The mode of antimicrobial action of the essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree oil). J Appl Microbiol. 2000; 88(1):170–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bapela NB, Lall N, Fourie SG, Franzblau SG, Van Rensburg CEJ. Activity of 7-methyljuglone in combination with antitubercolous drugs against Mycobacterium tubercolosis. Phytomedicine. 2006; 13(9–10):630–635. 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lâm TT, Claus H, Elias J, Frosch J, Vogel U. Ampicillin resistance of invasive Haemophilus influenzae isolates in Germany 2009–2012. Int J Med Microbiol. 2015; 305(7):748–755. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2015.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Te Dorsthorst DTA, Verweij PE, Meletiadis J, Bergevoet M, Punt NC, Meis JFGM, et al. In vitro interaction of flucytosine combined with Amphotericin B or Fluconazole against thirty-five yeast isolates determined by both the fractional inhibitory concentration index and the response surface approach. Antimicrob Ag Chemother. 2002; 46(9):2982–2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosato A, Vitali C, De Laurentis N, Armenise D, Milillo MA. Antibacterial effect of some essential oils administered alone or in combination with Norfloxacin, Phytomedicine. 2007; 14(11):727–732. 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosato A, Vitali C, Gallo D, Balenzano L, Mallamaci R. The inhibition of Candida species by selected essential oils and their synergism with Amphotericin. Phytomedicine. 2008; 15(8):635–638. 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosato A, Piarulli M, Corbo F, Muraglia M, Carone A, Vitali ME, et al. In vitro synergistic action of certain combinations of Gentamicin and Essential oils. Curr Med Chem. 2010; 17(28):3289–3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bicchi C, Brunelli C, Cordero C, Rubiolo P, Galli M, Sironi A. Direct resistively heated column gas chromatography (Ultrafast module-GC) for high-speed analysis of essential oils of differing complexities. J Chromat A. 2004; 1024(1–2):195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waseem R, Low KH. Advanced analytical techniques for the extraction and characterization of plant-derived essential oils by gas chromatography with mass spectrometry. J Sep Sci. 2015; 38(3):483–501. 10.1002/jssc.201400724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Di Vito M, Fracchiolla G, Mattarelli P, Modesto M, Tamburro A, Padula F, et al. Probiotic and tea tree oil treatments improve therapy of vaginal candidiasis: a preliminary clinical study. Med J Obstet Gynecol. 2016; 4(4):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liantonio A, Gramegna G, Camerino GM, Dinardo MM, Scaramuzzi A, Potenza MA, et al. In-vivo administration of CLC-K kidney chloride channels inhibitors increases water diuresis in rats: a new drug target for hypertension? J Hypertens. 2012; 30(1):153–167. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834d9eb9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zellner BDA, Bicchi C, Dugo P, Rubiolo P, Dugo G, Mondello L. Linear retention indices in gas chromatographic analysis: a review. Flavour Fragr. J. 2008; 23(5):297–314. [Google Scholar]

- 46.M07-A9: Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard—Ninety Edition 2012, Vol. 32, No. 2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne (USA) Laboratory Standards.

- 47.CLSI, Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeast. Approved standard, 3rd Ed. M27-A3, CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA 2008.

- 48.EUCAST, 2000. Terminology relating to methods for the determination of susceptibility of bacteria to antimicrobial agents, Eucast definitive document 2.1, European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID). Basel (SW). 6:503–508. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.White RL, Burgess DS, Manduru M, Bosso JA. Comparison of three different in vitro methods of detecting synergy: time-kill, checkerboard, and E test. Antimicrob Ag Chemother. 1996; 40(8):1914–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosato A, Piarulli M, Schiavone BIP, Montagna MT, Caggiano G, Muraglia M, et al. In vitro synergy testing of Anidulafungin with Fluconazole, Tioconazole, 5-Flucytosine and Amphotericin B against some Candida spp. Med Chem. 2012; 8(4):690–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williamson EM. Synergy and other interactions in phytomedicines. Phytomedicine. 2001; 8(5):401–409. 10.1078/0944-7113-00060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eloff JN. Quantification the bioactivity of plant extracts during screening and bioassay guided fractionation. Phytomedicine. 2004; 11(4):370–371. 10.1078/0944711041495218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berenbaum MC. What is synergy? Pharmacol Rev. 1989; 41(2):93–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van den Dool H, Kratz PD. A generalization of the retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas-liquid partition chromatography. J Chromatog A. 1963; 11:463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koo I, Kim S, Zhang X. Comparative analysis of mass spectral matching-based compound identification in gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J Chromatog A. 2013; 1298:132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mandalari G, Bennett RN, Bisignano G, Trombetta D, Saija A, Faulds CB, et al. Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids extracted from bergamot (Citrus bergamia Risso) peel, a by-product from the essential industry. J Appl Microbiol. 2007; 103(6):2056–2064. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03456.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trombetta D, Castelli D, Sarpietro MG, Venuti V, Cristiani M, Daniele C, et al. Mechanisms of antibacterial action of three monoterpenes. Antimicrob. Ag Chemother. 2005; 49(6):2474–2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.