We report portable, user-friendly reagents and equipment for visual, hands-on biology activities with supporting curriculum.

Abstract

Synthetic biology offers opportunities for experiential educational activities at the intersection of the life sciences, engineering, and design. However, implementation of hands-on biology activities in classrooms is challenging because of the need for specialized equipment and expertise to grow living cells. We present BioBits™ Bright, a shelf-stable, just-add-water synthetic biology education kit with easy visual outputs enabled by expression of fluorescent proteins in freeze-dried, cell-free reactions. We introduce activities and supporting curricula for teaching the central dogma, tunable protein expression, and design-build-test cycles and report data generated by K-12 teachers and students. We also develop inexpensive incubators and imagers, resulting in a comprehensive kit costing <US$100 per 30-person classroom. The user-friendly resources of this kit promise to enhance biology education both inside and outside the classroom.

INTRODUCTION

Synthetic biology aims to program biological systems to carry out useful functions. As a field, synthetic biology has made meaningful progress toward biomanufacturing of medicines (1, 2), sustainable chemicals (3, 4), and advanced fuels (5), as well as cellular diagnostics and therapies (6–9). At the core of these advances is the ability to control and tune the processes of transcription and translation, offering a point of entry for teaching fundamental biology topics through cutting-edge biological technologies. Synthetic biology also offers rich educational opportunities, as it requires students to confront real-world, interdisciplinary problems at the intersection of diverse disciplines including chemistry, biology, engineering, computer science, design, policy, and ethics. Such cross-cutting educational activities align closely with the objectives of K-12 STEAM (science, technology, engineering, the arts, and mathematics) education and priorities identified by the National Academy of Engineering to enable students to apply, adapt, and connect fundamental principles across multiple disciplines (10).

Synthetic biology–based educational efforts such as the BioBuilder Educational Foundation (11–14) and the International Genetically Engineered Machines competition (15, 16) have made great strides toward incorporating synthetic biology into high school and university education. These programs have resulted in student-reported academic gains, high student engagement, and increased self-identification as biological engineers (17–19). However, efforts to incorporate a hands-on molecular or synthetic biology curriculum have been limited by (i) the number of robust systems that can be converted into teaching materials; (ii) the need for expensive, specialized equipment to store, grow, and transport cells; and (iii) biosafety considerations that limit the ability to work with cells outside of a laboratory setting (20). Addressing these limitations would help expand educational opportunities for students in classrooms, as well as inform and promote public engagement in synthetic biology.

Freeze-dried, cell-free (FD-CF) systems represent an emerging technology with exciting potential as a chassis for educational tools. FD-CF systems harness an ensemble of catalytic components [for example, RNA polymerases, ribosomes, aminoacyl–transfer RNA (tRNA) synthetases, translation initiation, and elongation factors, etc.] from cell lysates to synthesize proteins in vitro (21). Hence, FD-CF reactions do not use intact organisms; thus, they circumvent many of the biosafety and biocontainment regulations that exist for living cells. Further, FD-CF systems are stable at room temperature for more than 1 year (22) and can be run simply by adding water and DNA template to a freeze-dried pellet of reagents, eliminating the need for specialized equipment or expertise to run reactions. Finally, FD-CF systems are robust, with demonstrated utility for point-of-use biosynthesis of sophisticated diagnostics, protein therapeutics, vaccines, small molecules, and molecular biology reagents (22–29). If FD-CF technology could be used to develop safe, portable, and easy-to-use educational tools, it would significantly lower the barrier to entry for teaching synthetic biology.

Here, we describe BioBits™ Bright, a portable, just-add-water educational kit and accompanying hands-on laboratory modules designed for use outside of the laboratory by untrained operators (Fig. 1). To facilitate kit construction, we developed a library of fluorescent proteins that express at high yields (≥600 μg ml−1) in FD-CF reactions. We report data for each module from workshops with Chicago K-12 students and teachers to demonstrate robustness and ease of use. Laboratory modules are designed to (i) synergize with fundamental biology education, as evidenced by the supporting curriculum developed by Chicago middle and high school teachers (curricula S1 to S5); (ii) be run independently or in sequence; and (iii) be adapted for use with students at various educational levels. Notably, to make BioBits™ Bright laboratory activities accessible to resource-limited classrooms, we have also developed low-cost incubators and imagers. Separately, we describe BioBits™ Explorer [see companion article by Huang et al. (30)], a next-generation BioBits™ kit developed to illustrate an even wider range of biological concepts (for example, enzymatic catalysis and genetic circuits). We anticipate that the availability of our BioBits™ kits and the data reported here will encourage teaching and broaden participation in the field of synthetic biology.

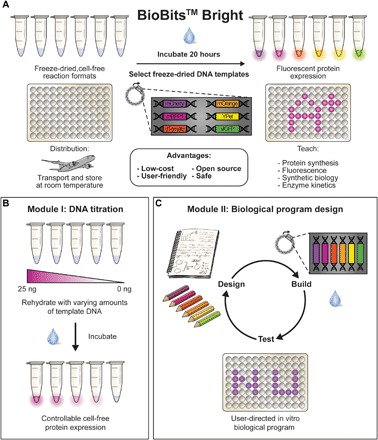

Fig. 1. BioBits™ Bright: A portable, cell-free synthesized fluorescent protein library for teaching the central dogma of molecular biology and synthetic biology.

(A) We describe here the development of an educational kit containing two laboratory modules using FD-CF reactions and a library of in vitro–synthesized fluorescent proteins. (B) In module I, students investigate how biological systems can be engineered by adding varying amounts of DNA template to FD-CF reactions. Titrating the amount of DNA template results in varying levels of fluorescent protein production, which are visible to the naked eye and under a blue or black light. (C) In module II, users design their own in vitro program using DNA encoding the fluorescent protein library and any of the DNA template concentrations investigated in module I. This module offers the opportunity to go through a user-directed design-build-test (DBT) cycle. All reagents used in these activities (freeze-dried reactions and plasmids) can be stored and transported without refrigeration, making them highly portable for use outside of the laboratory.

RESULTS

High-yielding in vitro expression of a diverse fluorescent protein library

Based on the success of colorimetric chemistry kits, we sought to create synthetic biology classroom modules for BioBits™ Bright with simple, visual readouts. We reasoned that the ability to link a visual output to abstract concepts such as the central dogma of molecular biology would increase student engagement and understanding. Fluorescent proteins are routinely used as reporters in synthetic biology and represent an attractive readout for an educational kit for two main reasons. First, a wide variety of fluorescent protein variants have been discovered or engineered (31–36), which produce an array of colors visible to the naked eye. Second, these variants are well studied and documented in freely available databases such as the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Table 1), making them ideal instructional tools.

Table 1. Diverse fluorescent protein library enables educational kit development.

A 13-member fluorescent protein library was designed to include red, orange, yellow, green, teal, and blue fluorescent protein variants, which were cloned into the in vitro expression vector pJL1. PDB accession numbers are provided if the protein (or a closely related variant) has been crystallized.

| Protein | Color |

Excitation (nm) |

Emission (nm) |

PDB entry |

| mCherry | Red | 587 | 610 | 2H5Q |

| mRFP1 | Red | 584 | 607 | 2VAD |

| eforRed | Red | 587 | 610 | 2VAD |

| dTomato | Orange | 554 | 581 | — |

| mOrange | Orange | 548 | 562 | 2H5O |

| YPet | Yellow | 517 | 530 | 1F0B |

| sfGFP | Green | 485 | 528 | 2B3P |

| mTFP1 | Cyan | 462 | 492 | 4Q9W |

| CyPet | Cyan | 435 | 477 | 3I19 |

| Aquamarine | Cyan | 420 | 474 | 2WSN |

| mTagBFP2 | Blue | 399 | 454 | 3M24 |

| mKalama1 | Blue | 385 | 456 | 4ORN |

| eBFP2 | Blue | 383 | 448 | 1BFP |

To build BioBits™ Bright, we initially designed a diverse 13-member fluorescent protein library based on existing fluorescent protein variants (Table 1) and cloned this library into the pJL1 cell-free expression vector. As an open-source kit, we have made these constructs available through Addgene (constructs 102629 to 102640, 106285, and 106320). The library was chosen to include red, orange, yellow, green, cyan, and blue fluorescent proteins. The selected library members represent a diversity of amino acid sequences, with sequence homology to our standard cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) reporter, a superfolder green fluorescent protein (sfGFP) variant (37), ranging from 90 to 22% (fig. S1). Because of this diversity, and because many of the library members were evolved in the laboratory from naturally occurring fluorescent proteins, the fluorescent protein library could be used to teach evolution, a required subject according to Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) for K-12 education (38, 39). Plasmids encoding each of the selected library members were used as templates in 5 μl FD-CF reactions lasting 20 hours at 30°C. Yields and full-length expression of all 13 fluorescent proteins were assessed using 14C-leucine incorporation.

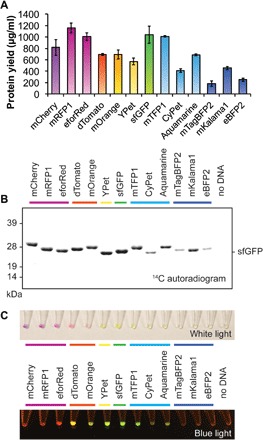

We observed that all proteins expressed with high soluble yields (between 160 and >1100 μg ml−1) (Fig. 2A) with exclusively full-length products observed on a Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel (fig. S2) and by autoradiogram (Fig. 2B). In particular, six fluorescent protein constructs (mCherry, mRFP1, dTomato, mOrange, YPet, and sfGFP) expressed at yields of ≥600 μg ml−1 and generated distinct colors and fluorescence visible to the naked eye (Fig. 2C). These results make these six proteins ideal candidates for educational tools, especially in resource-limited classrooms or other nonlaboratory settings. While expression is optimal at 30°C, the six-member library expresses with similar yields (~60% or higher) in reactions incubated at 21°C (room temperature) for 40 hours (fig. S3). These results indicate that precise temperature control is not required for CFPS, demonstrating that these reactions can be run without an incubator, water bath, or other specialized equipment. Notably, these proteins represent a diversity of amino acid sequences to facilitate evolution curriculum, with between 24 and 89% amino acid sequence homology to sfGFP (fig. S1). For these reasons, these six proteins were selected to form the core set of reagents for BioBits™ Bright, which we next used to develop two educational modules.

Fig. 2. High-yielding cell-free production of fluorescent protein library enables development of BioBits™ Bright.

A 13-member fluorescent protein library was designed to include red, orange, yellow, green, cyan, and blue fluorescent protein variants and cloned into the cell-free expression vector pJL1. (A) Following CFPS for 20 hours at 30°C, soluble yields of the fluorescent protein library were measured via 14C-leucine incorporation. Values represent averages, and error bars represent SDs of n ≥ 3 biological replicates. (B) Soluble fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and 14C autoradiogram. All library members expressed with exclusively full-length products observable by autoradiogram. (C) Images of FD-CF reactions expressing the fluorescent protein library under white light (top) and blue light (bottom).

Module I: Tunable in vitro expression of fluorescent proteins

The first laboratory module demonstrates the ability to control protein synthesis titers by varying the amount of DNA template present in FD-CF reactions, essentially limiting the in vitro transcription and translation reaction for one of its essential substrates. This activity teaches students fundamental biology and synthetic biology concepts such as (i) information flow in the central dogma of molecular biology and (ii) how synthetic biologists can engineer biological systems in predictable ways. Freeze-dried DNA templates encoding mCherry, mRFP1, dTomato, mOrange, and YPet were rehydrated, added to FD-CF reactions in varying amounts (25, 10, 5, 2.5, or 0 ng of DNA), and incubated at 30°C for 20 hours. The sixth library member, sfGFP, exhibited protein synthesis rates between 2 and 10 times faster than the other library members. This relatively high rate of protein synthesis is expected because sfGFP was evolved to exhibit enhanced folding and rapid fluorescence (40); however, after 20 hours, we were unable to observe discrete variations in protein synthesis with varying amounts of DNA template (fig. S4). This is not ideal for a typical classroom setting, where teachers will not see students for 24 to 48 hours after reactions are set up. For this reason, sfGFP was excluded from this module.

FD-CF reactions primed with varying concentrations of the five selected DNA templates were assembled by a graduate student (expert) and compared to those assembled by Chicago middle and high school students and teachers. In all cases, we observed that reducing the concentration of DNA template led to a concomitant decrease in total protein expression, even in reactions assembled by users who were running the BioBits™ Bright laboratory for the first time (Fig. 3A). Visible differences in color and fluorescence showing these trends were observable in all samples under both white and blue light (Fig. 3B). The ability to easily perceive variations in reaction color with the naked eye makes it possible to qualitatively assess protein synthesis yields from this module without a spectrophotometer. Through its easy, visual outputs, this laboratory module helps students understand how proteins are synthesized, as well as some of the key biochemical factors that affect this process (for example, DNA as the instructions that guide protein synthesis). As an extension of the activity presented here, students could investigate factors other than DNA concentration that affect protein synthesis, such as ion concentration, amino acid concentration, or energy substrate concentration, among others (41). As examples of these activities, we worked with Chicago public high school teachers to develop a set of inquiry-based curricula for this module with emphasis on student-driven experimental design to satisfy NGSS requirements for high school biology (curricula S1 and S2).

Fig. 3. Controllable in vitro expression of diverse fluorescent proteins.

FD-CF reactions were rehydrated with 25, 10, 5, 2.5, or 0 ng of template DNA encoding mCherry, mRFP1, dTomato, mOrange, or YPet and run for 20 hours at 30°C. (A) Results from experiments run by graduate students (experts), high school students, or middle and high school teachers are shown. In all cases, we observed a concomitant decrease in protein synthesis as the amount of DNA template was decreased. Values represent averages, and error bars represent average errors of n ≥ 2 biological replicates. (B) The variation in protein expression was marked enough to be observed qualitatively with the naked eye under both white light and blue light. Images are representative examples of experiments prepared by high school students.

Module II: Design, build, and test an in vitro biological program

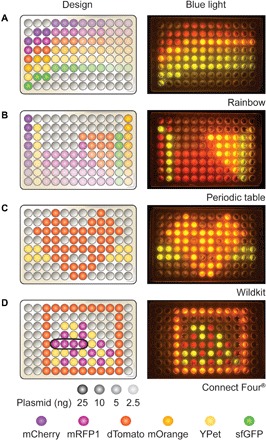

The second laboratory module engages participants in a design, build, test (DBT) cycle wherein they create their own in vitro program with DNA. This laboratory recapitulates the idea of controllable protein expression from module I, introduces the DBT cycle as a key synthetic biology and engineering concept, and could pair with a brief research project to introduce students to the broader field of synthetic biology (for example, curriculum S3). Specifically, participants were given a 96-well PCR plate containing 5 μl FD-CF reactions and separately freeze-dried plasmid templates. Programs could be constructed by rehydrating FD-CF reactions with any of the six-member fluorescent protein library members at any of the concentrations tested in the first laboratory module (0 to 25 ng of total template DNA). Participants designed, built, and tested their in vitro programs by carrying out protein synthesis for 20 hours at 30°C.

We ran this activity with students of varying ages, ranging from preschool-aged students to high school teachers, and observed a number of successful designs (Fig. 4). This module’s educational merit is twofold. First, this activity engages students in the engineering process, helping them go beyond simple pipetting and reagent handling for a self-directed, independent learning experience. Second, this module bridges the gap between science and art, offering an opportunity for incorporation of emerging interdisciplinary STEAM ideologies into biology curriculum, which have reported improved educational outcomes (42). One participant described this laboratory as a “biological Lite Brite,” highlighting the design component of this module and the potential for students’ creative innovation within this laboratory activity. Of note, sample curricula for high school math (curriculum S4) and middle school science classes (curriculum S5) were developed in partnership with Chicago area teachers, emphasizing the laboratory’s cross-cutting nature and the value of this activity at various educational levels.

Fig. 4. Design and execution of in vitro programs.

Participants were asked to design, build, and test their own in vitro program with DNA in a 96-well PCR plate. Designs could include the mCherry, mRFP1, dTomato, mOrange, YPet, or sfGFP plasmids at concentrations between 0 and 25 ng (same template concentrations tested in module I), denoted with corresponding colors and opacity in the pictured designs (legend, bottom left). Successful designs included (A) a rainbow, (B) a periodic table, (C) a wildkit (the Evanston Township High School mascot), and (D) a game of Connect Four®. These biological programs were designed, built, and tested by untrained operators, demonstrating the potential of this laboratory for use in a classroom setting.

Portable, low-cost imagers and incubators for taking BioBits™ beyond the laboratory

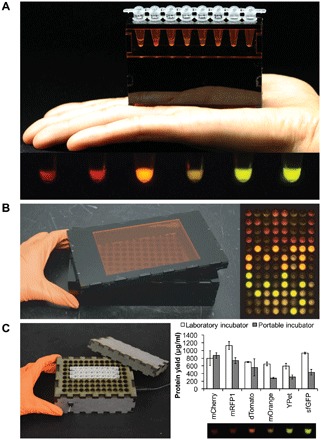

Recognizing that a vast majority of classrooms will not have laboratory-grade fluorescent imagers or incubators to run FD-CF reactions, we developed affordable and portable versions to make the BioBits™ Bright laboratory activities accessible to resource-limited classrooms. Specifically, we developed two compact, battery-powered imagers for visualizing FD-CF reactions producing fluorescent proteins. One imager is designed to accommodate eight-strip PCR tubes for imaging DNA titration experiments, while the second is designed for imaging 96-well plates containing in vitro biological programs. Both systems faithfully image the fluorescent protein library and have the same key components: a single 450-nm light-emitting diode (LED) light, colored acrylic plates to filter out the inherent color of the LED for fluorescence visualization (fig. S5), and a laser-cut casing to house the system (Fig. 5, A and B). The initial prototypes for the 8-well and 96-well imagers cost about US$15 and US$32, respectively, to build (table S1). We also developed two versions of a USB (universal serial bus)–powered incubator: one in which temperature is controlled by a switch calibrated to two temperature settings, 30° or 37°C (Fig. 5C), and one with a dial to enable any temperature setting between 30° and 37°C (folder S1). Both versions perform similarly and can be built in schools with fabrication workshops for less than US$20 (table S1).

Fig. 5. Portable, low-cost equipment for teaching outside of the laboratory.

(A) The eight-well imager is handheld and battery-operated for easy use (top) and can be used to image the six-member fluorescent library (bottom). We show FD-CF reactions expressing, from left to right, mCherry, mRFP1, dTomato, mOrange, YPet, and sfGFP. (B) The 96-well imager is also battery-powered and has a removable lid for easy use (left). In vitro biological programs can be imaged using our custom 96-well imager with similar performance as a laboratory imager (right). (C) The portable incubator accommodates up to 96 standard PCR tubes and has a removable, insulating lid for maintaining reaction temperature at its two set points, 30° and 37°C (left). Fluorescent protein yields using our incubator set at 30°C are at least 50% of those achieved using a laboratory incubator (top right) and produce fluorescence that is visible in our handheld eight-well imager (bottom right). Values represent averages, and error bars represent average errors of n = 2 biological replicates.

We tested the expression of our six-member fluorescent protein library at 30°C in our portable incubator and observed at least 50% of protein yields achieved using a thermocycler, with fluorescence easily observable in our handheld eight-well imager (Fig. 5C). As an example of cross-cutting STEAM education integrating engineering, fabrication, electronics, and synthetic biology, the BioBits™ Bright computer-aided design (CAD) files (folder S1) can be used with the open-source FreeCAD software and accompanying circuit diagrams (folder S1) to enable students to manufacture their own portable imager or incubator for use in subsequent experiments.

With the portable imagers and incubators at hand, we were able to demonstrate that FD-CF reactions can be run in a “laboratory-free” environment, using our portable incubator, imager, and disposable exact-volume transfer pipettes (VWR 89497-718) to rehydrate the reaction. Reactions run in the laboratory (with laboratory pipettes, incubators, and imagers) are comparable to those run with our kit components and are visually consistent across different experiments and different operators (fig. S6).

DISCUSSION

We present here the BioBits™ Bright educational kit and an accompanying collection of resources and data for teaching synthetic biology outside of the laboratory. To develop the fluorescent reagents, we assembled a fluorescent protein library that expresses at high yields in FD-CF reactions. We further demonstrated that both DNA templates encoding this library and cell-free reactions could be freeze-dried and reconstituted by just adding water, providing the necessary reagents for portable educational tools. Furthermore, we developed two laboratory modules designed to teach students about synthetic biology and successfully tested these modules with Chicago K-12 teachers and students. For both laboratory modules, we report data generated by both teachers and students, demonstrating the utility of these resources for use by untrained operators without sophisticated laboratory equipment.

In the first laboratory module, participants investigate how protein expression in FD-CF can be tuned by adding varying amounts of DNA template. This activity can be used to introduce the central dogma of molecular biology or the idea of tunable protein expression (for example, curricula S1 and S2). This module also reinforces basic biology concepts by demonstrating how variations in gene/protein sequence can affect protein function, since differences in protein sequence result in distinct protein properties (visible differences in protein color and fluorescence).

For more advanced groups, differences in protein synthesis rates and final titers can be measured and quantified to investigate how protein synthesis can be modeled as an enzymatic reaction and how kinetics can be controlled by changing the amount of substrate (DNA template). Alternatively, students can carry out the same investigation using sample kinetic data we collected from student-assembled reactions (data S1). Long-term independent science projects can also be conceived by incorporating complementary biochemistry and molecular biology experiments, such as one project we recently designed with a high school synthetic biology after-school club. In this example, students used FD-CF reactions to synthesize the human leptin hormone as a potential treatment for obesity and quantified the amount produced using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (43).

In the second laboratory module, participants design, build, and test their own in vitro program with DNA. This laboratory demonstrates how in vitro biological systems can be engineered to produce outputs of interest. This module primes students for discussion of synthetic biology and potential application areas (for example, therapeutic protein production, sustainable chemical production, and cellular/organismal engineering) and the ethics involved in the field (for example, curriculum S3). In addition, by engaging participants in a self-directed DBT cycle, this module offers a straightforward way to incorporate engineering principles into biology curriculum. Finally, the simple framework of this module encourages creative innovation through STEAM principles. The potential for such opportunities are highlighted by the complementary design activity (curriculum S5) and math curriculum piece we have developed (curriculum S4), as well as the availability of FreeCAD and our open-source design files to enable students to build their own portable fluorescence imagers and incubators (folder S1).

Importantly, BioBits™ Bright makes even more educational resources possible, perhaps through the formation of an open-source community. For example, next-generation iterations of these kits could incorporate antibiotic ribosome inhibitors for tuning protein expression, offering opportunities for educators to discuss health-related themes in class. In addition, coexpression of two or more fluorescent proteins or incorporation of synthetic genetic circuits (44) to control fluorescent protein expression would introduce students to more complex examples of biological regulation. Further, engagement of students through different sensory outputs could improve student engagement and understanding, which will empower them to make informed decisions about cutting-edge synthetic biology topics [for example, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)–Cas9 genome editing] (45). We have addressed some of these needs through the development of a next-generation kit: BioBits™ Explorer (see companion article). The Explorer kit expands the toolbox of educational materials for teaching synthetic biology and provides additional opportunities for student-driven, independent synthetic biology investigations. Beyond this, future work could expand the parallels between engineering, biology, and design, such as through the integration of a novel phone application and LED display to aid the design of in vitro biological programs in module II of the BioBits™ Bright kit (46). We also plan to launch a website where students can share their data and biological program designs with other users of these kits from around the world.

In sum, BioBits™ Bright represents a comprehensive set of educational resources for synthetic biology akin to the “chemistry set” that brought chemistry education to the masses and inspired generations of scientists. We have purposely designed our kit to be economically accessible, priced at less than US$100 per 30-person classroom (table S2). This is made possible by our in-house freeze-dried reactions, which are two orders of magnitude more affordable than existing commercial cell-free kits, at just ~US$0.01 per microliter of reaction volume (table S3) compared to ~US$1 per microliter (Promega L110; NEB E6800S). Our custom imagers and incubators are included in BioBits™ Bright, making reaction analysis accessible for resource-limited classrooms. Because of the highly portable, cost-effective, and user-friendly nature of the reagents and laboratory activities, the BioBits™ Bright and Explorer kits have utility both inside and outside of a formal classroom or laboratory setting. In sum, these resources promise to increase access to cell-free technologies, enhance basic biology education, and increase participation and teaching in the field of synthetic biology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids

Escherichia coli NEB 5-alpha (New England BioLabs) was used in plasmid cloning transformations and for plasmid preparation. E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for preparation of CFPS extracts. Gibson assembly was used for seamless construction of plasmids used in this study (table S4). For cloning, the pJL1 vector (Addgene, 69496) was digested using restriction enzymes Nde I and Sal I–HF (NEB). Each gene was amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (NEB) with forward and reverse primers designed with the NEBuilder Assembly Tool (nebuilder.neb.com) and purchased from IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies). PCR products were gel-extracted using the EZNA Gel Extraction Kit (Omega Bio-Tek), mixed with Gibson assembly reagents, and incubated at 50°C for 1 hour. Plasmid DNA from the Gibson assembly reactions was transformed into E. coli NEB 5-alpha cells, and circularized constructs were selected on LB agar supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg ml−1; Sigma-Aldrich). Sequence-verified clones were purified using the EZNA Plasmid Midi Kit (Omega Bio-Tek) for use in FD-CF reactions.

CFPS extract preparation

CFPS extract was prepared by sonication, as previously reported (47). Briefly, E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was grown in 2× YTPG media at 37°C. T7 polymerase expression was induced at an OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) of 0.6 to 0.8 with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside. Cells were grown at 30°C to a final OD600 of 3.0, at which point cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 5000g for 15 min at 4°C. Cell pellets were then washed three times with cold S30 buffer [10 mM tris-acetate (pH 8.2), 14 mM magnesium acetate, and 60 mM potassium acetate] and pelleted at 5000g for 10 min at 4°C. After the final wash, cells were pelleted at 7000g for 10 min at 4°C, weighed, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. For lysis, cell pellets were suspended in 1 ml of S30 buffer per 1 g of wet cell mass, and cells were transferred into 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes and placed in an ice-water bath to minimize heat damage during sonication. The cells were lysed using a Q125 Sonicator (Qsonica) with a 3.175-mm-diameter probe at 20 kHz and 50% amplitude. The input energy was monitored, with 640 J used to lyse 1 ml of suspended cells. The lysate was then centrifuged once at 12,000g at 4°C for 10 min. Cell extract was aliquoted, flash-frozen on liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Alternatively, for classroom settings where it is not practical to generate or obtain FD-CF reactions, similar cell-free systems are available commercially from companies such as Promega (L1130).

Cell-free protein synthesis

FD-CF reactions were carried out in PCR tubes or plates (5 μl reactions). The CFPS reaction mixture consisted of the following components: 1.2 mM adenosine 5′-triphosphate; 0.85 mM each of guanosine 5′-triphosphate, uridine 5′-triphosphate, and cytidine 5′-triphosphate; l-5-formyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrofolic acid (34.0 μg ml−1; folinic acid); E. coli tRNA mixture (170.0 μg ml−1); 130 mM potassium glutamate; 10 mM ammonium glutamate; 8 mM magnesium glutamate; 2 mM each of 20 amino acids; 0.4 mM nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; 0.27 mM coenzyme A; 1.5 mM spermidine; 1 mM putrescine; 4 mM sodium oxalate; 33 mM phosphoenolpyruvate; 57 mM HEPES; plasmid (13.3 μg ml−1; unless otherwise noted); and 27% (v/v) of cell extract (48). For quantification of fluorescent protein yields via radioactive leucine incorporation, 10 μM l-14C-leucine (11.1 gigabecquerel mmol−1, PerkinElmer) was added to the CFPS mixture.

Lyophilization of cell-free reactions

FD-CF reactions were prepared according to the recipe above, but without plasmid added. CFPS reactions and plasmids were separately lyophilized using a VirTis BenchTop Pro lyophilizer (SP Scientific) at 100 mtorr and −80°C overnight or until fully freeze-dried. Following lyophilization, plasmids were rehydrated with nuclease-free water (Ambion) and added to FD-CF reaction pellets at a final concentration of 13.3 μg mL−1, unless otherwise noted. CFPS reactions were carried out at 30°C for 20 hours after rehydration, unless otherwise noted. In a classroom setting, reactions can be incubated in our portable incubator at 30°C or in a 30°C water bath in an insulated container (Styrofoam, plastic cooler, etc.) for 20 hours. Alternatively, reactions can be run in a room temperature water bath or on a tabletop for 40 hours.

Quantification of in vitro–synthesized protein

Active full-length protein synthesis was measured continuously via fluorescence using the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). If fluorescence saturated the real-time PCR detector, then endpoint fluorescence was measured in 96-well half-area black plates (CoStar 3694; Corning Incorporated) using a Synergy2 plate reader (BioTek). Excitation (ex) and emission (em) wavelengths used to measure fluorescence of each protein construct were as follows: mCherry, eforRed, mRFP1, and dTomato: ex, 560 to 590 nm; em, 610 to 650 nm; mOrange: ex, 515 to 535 nm; em, 560 to 580 nm; YPet, sfGFP, mTFP1, CyPet, Aquamarine, mTagBFP2, mKalama1, and eBFP2: ex, 450 to 490; em, 510 to 530 nm. Following CFPS, reactions were centrifuged at 20,000g for 10 min to remove insoluble or aggregated protein products before further analysis. To quantify the amount of protein synthesized, two approaches were used. For assessing yields of the full 13-member library, reaction samples were analyzed directly by incorporation of 14C-leucine into trichloroacetic acid–precipitable radioactivity using a liquid scintillation counter, as described previously (49). These reactions were also run on a Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel and exposed by autoradiography. Autoradiographs were imaged with Typhoon 7000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Following selection of the smaller six-member library, standard curves were generated for mCherry, mRFP1, dTomato, mOrange, and YPet constructs via serial dilution of CFPS reactions containing 14C-leucine and correlating protein yields with measured fluorescence (fig. S7). Fluorescence units of sfGFP were converted to concentrations using a standard curve, as previously described (50).

For quantification without a spectrophotometer, reactions can be semiquantitatively analyzed via imaging using one of our portable, low-cost imagers and subsequent fluorescence analysis in ImageJ, a free image-processing program (imagej.nih.gov/ij). Images of FD-CF reactions were taken with a digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) camera and arranged in Adobe Illustrator. Protein production can also be qualitatively assessed with the naked eye under white light or blue or black light using our portable blue light imagers (Fig. 5) or others [for example, Bio-Rad ultraviolet (UV) pen lights #1660530EDU, Walmart black light bulb with fixture #552707607, Home Science Tools portable UV black light #OP-BLKLITE, and miniPCR blueBox transilluminator #QP-1700-01].

Construction of portable imagers and incubators

To design our portable laboratory equipment, we used the open-source three-dimensional CAD modeling software FreeCAD. Open-source tutorials for FreeCAD are also available on their website (freecadweb.org). Designed acrylic or wood components were laser-cut to desired specifications (folder S1) and assembled using adhesive (SCIGRIP Weld-On 16 for acrylics or Gorilla Wood Glue for wood components). Individual acrylic or wood parts were gently pressed together by hand for about a minute and left to cure overnight. Electronic components were soldered, and heat shrink was applied as necessary. Once the incubator circuit was assembled (folder S1), it was mounted onto the incubator with 0.25-inch screws through laser-cut and/or predrilled pilot holes.

After the incubator was assembled, the set temperature was calibrated. For the switch version of the incubator, various resistors or resistor combinations were tested to achieve the two desired temperature set points (30° and 37°C). For the dial version of the incubator, the potentiometer position was adjusted to reach the desired set points. In both cases, the temperature was monitored using an Arduino and, once determined, the set positions were labeled and temperatures were verified through additional temperature monitoring.

Statistical analysis

Statistical parameters including the definitions and values of n, SDs, and/or SEs are reported in the figures and corresponding figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge M. Barbier, R. Campbell, P. Daugherty, M. Davidson, J. Leonard, and R. Tsien for the gift of plasmids encoding fluorescent protein genes. We also acknowledge A. d’Aquino and M. Takahashi for help in editing the manuscript, J. Dietch for help with the Python Environment for Tree Exploration (ETE) toolkit, L. Durbin for help with portable laboratory equipment assembly and the laboratory-free experiments, and M. Beltran, Christopher Jewett, Colin Jewett, and E. Jewett for help in the design and execution of the in vitro Connect Four® game. Funding: This work was supported by the Army Research Office grant W911NF-16-1-0372 (to M.C.J.), NSF grants MCB-1413563 and MCB-1716766 (to M.C.J.), the Air Force Research Laboratory Center of Excellence grant FA8650-15-2-5518 (to M.C.J.), the Defense Threat Reduction Agency grant HDTRA1-15-10052/P00001 (to M.C.J.), the David and Lucile Packard Foundation (to M.C.J.), the Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Program (to M.C.J.), and the U.S. Department of Energy BER (Biological and Environmental Research) grant DE-SC0018249 (to M.C.J.). We also acknowledge support from the Wyss Institute (to J.J.C.), the Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group (to J.J.C.), the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (to J.J.C.), and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada (RGPIN-2016-06352 to K.P.). J.C.S. was supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship. A.H. was supported by the Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group. P.Q.N. was supported by a Wyss Technology Development Fellowship. R.S.D. was funded, in part, by the Northwestern University Chemistry of Life Processes Summer Scholars program. The U.S. government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for governmental purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation thereon. The views and conclusions contained herein are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of the Air Force Research Laboratory, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, or the U.S. government. Author contributions: J.C.S., A.H., and P.Q.N. designed research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. J.B., T.M., A.M.-B., A.P., K.R., M.S., and L.B. performed research and designed the curriculum. T.C.F., R.S.D., K.J.H., M.A., A.K., Q.M., J.S.P., R.P., P.P., D.Q., T.Z., L.R.H., J.F.C., N.F., S.F., E.G., E.M.G., T.G., J.K., B.N., S.O., C.P., A.P., S.S., A.S., and T.W. performed research. N.D. and K.P. aided in research design. M.C.J. and J.J.C. directed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All plasmid constructs used in this study are deposited on Addgene (constructs 102629 to 102640, 104776, and 104777), and student-generated fluorescence data from Fig. 3 are included as part of the Supplementary Material (data S1). Reagents are available by request from M.C.J. All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/8/eaat5107/DC1

Fig. S1. Diversity of the fluorescent protein library facilitates evolution curriculum.

Fig. S2. Fluorescent protein library expresses with soluble, full-length products observed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiogram.

Fig. S3. FD-CF reactions tolerate a range of incubation temperatures.

Fig. S4. DNA template is not limiting for in vitro sfGFP synthesis due to relatively high initial rates of protein synthesis.

Fig. S5. Orange and yellow filters enable imaging of diverse fluorescent proteins in portable imagers.

Fig. S6. FD-CF reactions can be run in a laboratory-free environment using low-cost, portable imagers and incubators.

Fig. S7. Standard curves for converting fluorescence to protein concentrations.

Table S1. Cost analysis of portable imagers and incubators.

Table S2. Cost analysis for BioBits™ Bright.

Table S3. Cost analysis of FD-CF reactions.

Table S4. Plasmids used in this study.

Curriculum S1. Let it glow!

Curriculum S2. What factors affect CFPS yields?

Curriculum S3. Synthetic biology: Looking to nature to engineer new designs.

Curriculum S4. How fast is it really?

Curriculum S5. Super power protein!

Data S1. This file contains example student-generated fluorescence data from the tunable protein expression laboratory activity (Fig. 3) and includes time-course data for modeling protein synthesis as an enzymatic reaction with varying amounts of substrate (DNA template).

Folder S1. This folder contains FreeCAD files and circuit diagrams to enable user construction of portable imagers and incubators.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Paddon C. J., Westfall P. J., Pitera D. J., Benjamin K., Fisher K., McPhee D., Leavell M. D., Tai A., Main A., Eng D., Polichuk D. R., Teoh K. H., Reed D. W., Treynor T., Lenihan J., Jiang H., Fleck M., Bajad S., Dang G., Dengrove D., Diola D., Dorin G., Ellens K. W., Fickes S., Galazzo J., Gaucher S. P., Geistlinger T., Henry R., Hepp M., Horning T., Iqbal T., Kizer L., Lieu B., Melis D., Moss N., Regentin R., Secrest S., Tsuruta H., Vazquez R., Westblade L. F., Xu L., Yu M., Zhang Y., Zhao L., Lievense J., Covello P. S., Keasling J. D., Reiling K. K., Renninger N. S., Newman J. D., High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature 496, 528–532 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galanie S., Thodey K., Trenchard I. J., Interrante M. F., Smolke C. D., Complete biosynthesis of opioids in yeast. Science 349, 1095–1100 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielsen J., Keasling J. D., Engineering cellular metabolism. Cell 164, 1185–1197 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yim H., Haselbeck R., Niu W., Pujol-Baxley C., Burgard A., Boldt J., Khandurina J., Trawick J. D., Osterhout R. E., Stephen R., Estadilla J., Teisan S., Schreyer H. B., Andrae S., Yang T. H., Lee S. Y., Burk M. J., Van Dien S., Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for direct production of 1,4-butanediol. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 445–452 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu C., Colón B. C., Ziesack M., Silver P. A., Nocera D. G., Water splitting–biosynthetic system with CO2 reduction efficiencies exceeding photosynthesis. Science 352, 1210–1213 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danino T., Prindle A., Kwong G. A., Skalak M., Li H., Allen K., Hasty J., Bhatia S. N., Programmable probiotics for detection of cancer in urine. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 289ra84 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porter D. L., Levine B. L., Kalos M., Bagg A., June C. H., Chimeric antigen receptor–modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 725–733 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riglar D. T., Giessen T. W., Baym M., Kerns S. J., Niederhuber M. J., Bronson R. T., Kotula J. W., Gerber G. K., Way J. C., Silver P. A., Engineered bacteria can function in the mammalian gut long-term as live diagnostics of inflammation. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 653–658 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roybal K. T., Williams J. Z., Morsut L., Rupp L. J., Kolinko I., Choe J. H., Walker W. J., McNally K. A., Lim W. A., Engineering T cells with customized therapeutic response programs using synthetic notch receptors. Cell 167, 419–432.e16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Academy of Engineering, Educating the Engineer of 2020: Adapting Engineering Education to the New Century (National Academies Press, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandran D., Bergmann F. T., Sauro H. M., TinkerCell: Modular CAD tool for synthetic biology. J. Biol. Eng. 3, 19 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon J., Kuldell N., BioBuilding: Using banana-scented bacteria to teach synthetic biology. Methods Enzymol. 497, 255–271 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon J., Kuldell N., Mendel’s modern legacy: How to incorporate engineering in the biology classroom. Sci. Teach. 79, 52–57 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levskaya A., Chevalier A. A., Tabor J. J., Simpson Z. B., Lavery L. A., Levy M., Davidson E. A., Scouras A., Ellington A. D., Marcotte E. M., Voigt C. A., Synthetic biology: Engineering Escherichia coli to see light. Nature 438, 441–442 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.iGEM Team EPFL 2017, Educational Cell-Free Mini Kit (ECFK) (2017); 2017.igem.org/Team:EPFL/HP/Mini-Kit.

- 16.Kelwick R., Bowater L., Yeoman K. H., Bowater R. P., Promoting microbiology education through the iGEM synthetic biology competition. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 362, fnv129 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell A. M., Meeting report: Synthetic biology Jamboree for undergraduates. Cell Biol. Educ. 4, 19–23 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.R. Mitchell, N. Kuldell, MIT’s introduction to biological engineering: A longitudinal study of a freshman inquiry-based class, in Inquiry-Based Learning for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) Programs: A Conceptual and Practical Resource for Educators. (Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2015), pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell R., Dori Y. J., Kuldell N. H., Experiential engineering through iGEM—An undergraduate summer competition in synthetic biology. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 20, 156–160 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuldell N., Authentic teaching and learning through synthetic biology. J. Biol. Eng. 1, 8 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson E. D., Gan R., Hodgman C. E., Jewett M. C., Cell-free protein synthesis: Applications come of age. Biotechnol. Adv. 30, 1185–1194 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pardee K., Green A. A., Ferrante T., Cameron D. E., DaleyKeyser A., Yin P., Collins J. J., Paper-based synthetic gene networks. Cell 159, 940–954 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pardee K., Slomovic S., Nguyen P. Q., Lee J. W., Donghia N., Burrill D., Ferrante T., McSorley F. R., Furuta Y., Vernet A., Lewandowski M., Boddy C. N., Joshi N. S., Collins J. J., Portable, on-demand biomolecular manufacturing. Cell 167, 248–259.e12 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pardee K., Green A. A., Takahashi M. K., Braff D., Lambert G., Lee J. W., Ferrante T., Ma D., Donghia N., Fan M., Daringer N. M., Bosch I., Dudley D. M., O’Connor D. H., Gehrke L., Collins J. J., Rapid, low-cost detection of Zika virus using programmable biomolecular components. Cell 165, 1255–1266 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gootenberg J. S., Abudayyeh O. O., Lee J. W., Essletzbichler P., Dy A. J., Joung J., Verdine V., Donghia N., Daringer N. M., Freije C. A., Myhrvold C., Bhattacharyya R. P., Livny J., Regev A., Koonin E. V., Hung D. T., Sabeti P. C., Collins J. J., Zhang F., Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science 356, 438–442 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salehi A. S. M., Smith M. T., Bennett A. M., Williams J. B., Pitt W. G., Bundy B. C., Cell-free protein synthesis of a cytotoxic cancer therapeutic: Onconase production and a just-add-water cell-free system. Biotechnol. J. 11, 274–281 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith M. T., Berkheimer S. D., Werner C. J., Bundy B. C., Lyophilized Escherichia coli-based cell-free systems for robust, high-density, long-term storage. Biotechniques 56, 186–193 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dudley Q. M., Anderson K. C., Jewett M. C., Cell-free mixing of Escherichia coli crude extracts to prototype and rationally engineer high-titer mevalonate synthesis. ACS Synth. Biol. 5, 1578–1588 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaroentomeechai T., Stark J. C., Natarajan A., Glasscock C. J., Yates L. E., Hsu K. J., Mrksich M., Jewett M. C., DeLisa M. P., Single-pot glycoprotein biosynthesis using a cell-free transcription-translation system enriched with glycosylation machinery. Nat. Commun. 9, 2686 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang A., Nguyen P. Q., Stark J. C., Takahashi M. K., Donghia N., Ferrante T., Dy A. J., Hsu K. J., Dubner R. S., Pardee K., Jewett M. C., Collins J. J., BioBits™ Explorer: A modular synthetic biology education kit. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat5105 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaner N. C., Campbell R. E., Steinbach P. A., Giepmans B. N. G., Palmer A. E., Tsien R. Y., Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 1567–1572 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen A. W., Daugherty P. S., Evolutionary optimization of fluorescent proteins for intracellular FRET. Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 355–360 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ai H.-w., Henderson J. N., Remington S. J., Campbell R. E., Directed evolution of a monomeric, bright and photostable version of Clavularia cyan fluorescent protein: Structural characterization and applications in fluorescence imaging. Biochem. J. 400, 531–540 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heim R., Tsien R. Y., Engineering green fluorescent protein for improved brightness, longer wavelengths and fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Curr. Biol. 6, 178–182 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Subach O. M., Cranfill P. J., Davidson M. W., Verkhusha V. V., An enhanced monomeric blue fluorescent protein with the high chemical stability of the chromophore. PLOS ONE 6, e28674 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giepmans B. N. G., Adams S. R., Ellisman M. H., Tsien R. Y., The fluorescent toolbox for assessing protein location and function. Science 312, 217–224 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bundy B. C., Swartz J. R., Site-specific incorporation of p-propargyloxyphenylalanine in a cell-free environment for direct protein–protein click conjugation. Bioconjug. Chem. 21, 255–263 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Next Generation Science Standards, Middle School Life Science Standards (Next Generation Science Standards, 2013); nextgenscience.org/sites/default/files/MS%20LS%20DCI%20combinedf.pdf.

- 39.Next Generation Science Standards, High School Natural Selection and Evolution Standards (Next Generation Science Standards, 2017); nextgenscience.org/topic-arrangement/hsnatural-selection-and-evolution.

- 40.Pédelacq J. D., Cabantous S., Tran T., Terwilliger T. C., Waldo G. S., Engineering and characterization of a superfolder green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 79–88 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albayrak C., Jones K. C., Swartz J. R., Broadening horizons and teaching basic biology through cell-free synthesis of green fluorescent protein in a high school laboratory course. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 22, 963–973 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peppler K., STEAM-powered computing education: Using e-textiles to integrate the arts and STEM. Computer 46, 38–43 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson M., Mucha Q., Patel R., Patel P., Qaq D., Zondor T., The production of human leptin using cell-free protein synthesis. Biotreks 2, e201705 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 44.R. M. Murray, Build a DNA circuit (2017); txtlbio.org/waitwhat/.

- 45.Doudna J. A., Charpentier E., The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 346, 1258096 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.H. Steiner, T. Meany, bi.xels (2017); designbio.co.uk/blog/bi-xels.

- 47.Kwon Y.-C., Jewett M. C., High-throughput preparation methods of crude extract for robust cell-free protein synthesis. Sci. Rep. 5, 8663 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jewett M. C., Swartz J. R., Mimicking the Escherichia coli cytoplasmic environment activates long-lived and efficient protein synthesis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 86, 19–26 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jewett M. C., Calhoun K. A., Voloshin A., Wuu J. J., Swartz J. R., An integrated cell-free metabolic platform for protein production and synthetic biology. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4, 220 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hong S. H., Ntai I., Haimovich A. D., Kelleher N. L., Isaacs F. J., Jewett M. C., Cell-free protein synthesis from a release factor 1 deficient Escherichia coli activates efficient and multiple site-specific nonstandard amino acid incorporation. ACS Synth. Biol. 3, 398–409 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/8/eaat5107/DC1

Fig. S1. Diversity of the fluorescent protein library facilitates evolution curriculum.

Fig. S2. Fluorescent protein library expresses with soluble, full-length products observed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiogram.

Fig. S3. FD-CF reactions tolerate a range of incubation temperatures.

Fig. S4. DNA template is not limiting for in vitro sfGFP synthesis due to relatively high initial rates of protein synthesis.

Fig. S5. Orange and yellow filters enable imaging of diverse fluorescent proteins in portable imagers.

Fig. S6. FD-CF reactions can be run in a laboratory-free environment using low-cost, portable imagers and incubators.

Fig. S7. Standard curves for converting fluorescence to protein concentrations.

Table S1. Cost analysis of portable imagers and incubators.

Table S2. Cost analysis for BioBits™ Bright.

Table S3. Cost analysis of FD-CF reactions.

Table S4. Plasmids used in this study.

Curriculum S1. Let it glow!

Curriculum S2. What factors affect CFPS yields?

Curriculum S3. Synthetic biology: Looking to nature to engineer new designs.

Curriculum S4. How fast is it really?

Curriculum S5. Super power protein!

Data S1. This file contains example student-generated fluorescence data from the tunable protein expression laboratory activity (Fig. 3) and includes time-course data for modeling protein synthesis as an enzymatic reaction with varying amounts of substrate (DNA template).

Folder S1. This folder contains FreeCAD files and circuit diagrams to enable user construction of portable imagers and incubators.