Abstract

Evidence from previous studies has suggested that movement execution in younger adults is accelerated in response to temporally predictable vs. unpredictable sensory stimuli. This effect indicates that external temporal information can modulate motor behavior; however, how aging can influence temporal predictive mechanisms in motor system has yet to be understood. The objective of the present study was to investigate aging effects on the initiation and inhibition of speech and hand movement reaction times in response to temporally predictable and unpredictable sensory stimuli. Fifteen younger (mean age: 22.6) and fifteen older (mean age: 63.8) adults performed a randomized speech vowel vocalization or button press initiation and inhibition tasks in two counterbalanced blocks in response to temporally predictable and unpredictable visual cue stimuli. Results showed that motor reaction time was accelerated in both younger and older adults for predictable vs. unpredictable stimuli during initiation and inhibition of speech and hand movement. However, older adults were significantly slower than younger adults in motor execution of speech and hand movement when stimulus timing was unpredictable. Moreover, we found that overall, motor inhibition of speech and hand was executed faster than their initiation. Our findings suggest that older adults can compensate age-related decline in motor reaction times by incorporating external temporal information and execute faster movement in response to predictable stimuli whereas unpredictable temporal information cannot counteract aging effects efficiently and lead to less accurate motor timing predictive codes for speech production and hand movement.

Keywords: Aging, Speech production, Hand movement, Motor reaction time, Temporal predictive code

Introduction

Temporal information processing is a fundamentally important function of the human nervous system, which enables us to process sensory stimuli and generate motor responses with high temporal precision. Beside our nervous system’s ability to generate temporally precise and accurate movements in our limb motor system [1–6], studies have shown that temporal aspects of sensory stimuli can also enhance motor timing responses during speech production [7,6,5]. Converging evidence from these studies indicates that temporally predictable sensory stimuli can accelerate response time for movement initiation [1–4,8,5,6] and inhibition [9,6,10] compared to unpredictable stimuli. It has been suggested that the motor system itself can extract temporal information from sensory stimuli [11,12] and thus facilitate temporal processing of movement initiation and inhibition response time during speech production [7,5,6] and hand movement [2,3,13,5,6,14].

However, studies regarding temporal mechanisms in the motor system have focused primarily on younger adults [1,13,15,9,14,8,5,6,16,10,17] and it remains elusive how aging can affect temporal aspects of movement initiation and inhibition in response to temporally predictable and unpredictable sensory stimuli.

The aim of the present study is to examine how aging can affect motor response reaction time for initiation and inhibition of speech and hand movement when sensory stimulus timing is predictable or unpredictable. In what follows, we will provide a general overview of how temporal aspects of sensory stimuli can modulate movement initiation and inhibition of speech and hand movement in younger adults and will review the findings of studies that examined aging effect on the mechanisms of movement reaction time. We will finally conclude with discussing our novel approach to address questions on how temporal aspects of sensory stimuli can modulate speech and hand motor behavior in older adults and what predictions were established in the present study.

Temporal aspects of movement initiation and inhibition

The temporal processing of movement has been examined using motor reaction time tasks during which subjects were required to press a button [1–3,13,14,16,17,6,5] or produce a speech sound [7,5,6]. Reaction time has been considered as a behavioral index of information processing [18] and has been used to address how temporal information can modulate movement response times [19,4,15,9,8,5,6].

Some studies have manipulated inter-stimulus intervals (ISI) to examine temporal mechanisms in the motor system [20,21,16]. These studies have revealed that fixed ISIs can accelerate hand movement initiation compared with variable ISIs, suggesting that the motor system is able to use past timing information to establish temporal predictions in response preparation for future movement. Other studies have used the well-established Foreperiod (FP) paradigm to examine temporal mechanisms in the motor system [1,2,13,9,14]. The FP task involves a warning signal that appears on the screen, followed by an interval before the imperative signal with predictable (fixed) or unpredictable (variable) timing [2]. From an information processing perspective, FP provides a mechanism for temporal preparation for the upcoming imperative signal. Studies demonstrated that during short FPs, a predictable interval between warning and imperative signals can accelerate hand movement initiation response times compared to unpredictable FPs [22,14]. The faster reaction time for fixed FPs indicates that temporally predictable information can enhance the preparatory phase of movement initiation compared to unpredictable intervals.

In contrast to movement initiation, few studies have examined the effect of temporal aspects of sensory stimuli on movement inhibition reaction time [9,10,6]. While some studies have found that movement inhibition is not sensitive to the predictability of sensory stimuli [23,15], others indicated that temporally predictable sensory stimuli can accelerate movement inhibition compared to unpredictable stimuli [9,10,6].

Nevertheless, it is relatively unclear whether temporal processing of movement initiation and inhibition share common mechanisms. A recent study showed that movement initiation reaction time was positively correlated with movement inhibition reaction time in response to both temporally predictable and unpredictable sensory stimuli [6], and the correlation was stronger when timing information was predictable. These findings suggest that even though movement initiation and inhibition may be driven by distinct functional mechanisms in the brain, they may share common mechanisms for temporal information processing.

Effects of temporal predictability on speech and hand movement reaction time

Temporal aspects of sensory stimuli can modulate response time for both speech production and hand movement, but it is still unclear if these modalities share common temporal mechanisms. Previous studies have demonstrated interaction between speech production and hand movement at both neural [24–28] and behavioral levels [6]. Although most studies on temporal aspects of movement initiation and inhibition have focused on hand movement [3,20,9,14,8,16,10,17], a few studies have examined these mechanisms during speech production [7,5,6]. Similar to effects observed during hand movements, faster reaction times were registered in response to temporally predictable vs. unpredictable sensory stimuli during speech initiation [5,6] and inhibition [6]. Moreover, motor reaction times for initiation and inhibition of hand movement were positively correlated with speech initiation and inhibition, suggesting that speech production and hand movements share common temporal mechanisms to initiate or inhibit movement in response to temporally predictable and unpredictable sensory stimuli.

Temporal predictive code in motor system

We recently proposed that temporal aspects of movement initiation and inhibition follow the principle of the predictive code model [5,6]. According to this model, the brain can extract temporal aspects of sensory stimuli to establish predictions about the timing of upcoming imperative signals, and these predictions are more robust and precise when temporal information is predictable. Specifically, we suggested that motor system may recruit distinct functional mechanisms to initiate/inhibit movement in response to temporally predictable vs. unpredictable sensory stimuli [6]. The notion of a temporal predictive code in motor system is supported by findings in a recent study showing that different cortical regions of the brain within the parietal lobe are involved in processing temporally predictable vs. unpredictable intervals [17]. This latter study suggested that for temporally predictable intervals, the brain can extract temporal information from sensory stimuli and establish temporal expectancy about the timing of upcoming imperative signals. Temporally unpredictable intervals, however, are supported by the hazard function in which the probability of the upcoming imperative signal increases as time elapses, leading to slower and less precise motor responses.

Aging effects on temporal aspects of movement production

Temporal predictive coding mechanisms in the motor system are mainly studied in younger adults [2,3,20,14,16,7], and the effect of aging on these mechanisms has remained relatively unclear. Studies have found that as individuals age, they show increasing difficulties in processing of temporal information at sensory [29,30] and motor levels [31–33]. Older adults are slower than younger adults during motor reaction time tasks [19,8]. This slower reaction time in older adults may be attributed to a slower central processing, which can subsequently decelerate movement production reaction time [34]. Alternatively, this effect can also be accounted for by a specific abnormality in temporal information processing in older adults [35,29,36,37]. Older adults have also been reported to make more errors than younger adults during the performance of time perception-related tasks [36]. Specifically, older adults are shown to overestimate temporal intervals suggesting their difficulty in processing temporal information for sensory stimuli [35]. It has been suggested that motor timing and time perception are subserved by common neural networks in motor cortex [38], so that slower reaction times in older adults might be due to a general decline in temporal processing for movement production.

While studies have shown abnormal temporal processing older individuals, it is not fully understood how aging can affect temporal predictive coding mechanisms in the motor system. It has been demonstrated that older adults are significantly slower than younger adults in hand movement initiation during both fixed and variable FPs, suggesting age-related decline in temporal predictive code mechanisms limb motor system [8]. Moreover, older adults have been shown to fail to use explicit temporal cues to accelerate hand movement reaction time during short FPs, while younger subjects responded faster than older adults and used temporal cues to facilitate hand movement initiation [37]. In contrast, a recent study [39] has found that both older and younger adults can benefit from explicit temporal cues during short FPs to accelerate hand movement reaction times. Therefore, findings on temporal predictive mechanisms in older adults do not conform a consistent framework across different studies and it is not fully understood how aging may influence temporal processing mechanisms in the human motor system.

Study objectives

Although previous studies have provided some insights into age-related changes of temporal processing mechanisms during movement production [8,37,39], our understanding of how aging can influence these mechanisms has been limited by two factors. First, previous studies on the effects of aging on temporal aspects of movement production have been limited to comparing older and younger adults only during hand movement [8,37,39]. Therefore, it is still unclear whether temporal aspects of speech production are similarly or differently affected by aging. Second, the effect of aging on temporal aspects of movement production has been studied during hand movement initiation [8,37,39], and less is known about aging effects on these mechanisms during movement inhibition for speech production and hand movement.

The present study was motivated by the question of how aging would influence the temporal predictive coding mechanisms in the motor system during initiation and inhibition of speech production and movement. We designed an experiment in which both younger and older adults performed a randomized speech (vowel vocalization) or hand (button press) motor response reaction time task in two counterbalanced blocks with temporally predictable and unpredictable visual stimuli. The visual stimuli were presented to cue the subjects to first initiate and then inhibit the ongoing motor action during speech or hand movement tasks, with either fixed or randomized time intervals during predictable and unpredictable blocks, respectively. We used motor response reaction time as a behavioral index of temporal information processing during speech production and hand movement. This novel experimental design provided a unified framework to simultaneously examine the effects of temporal predictability on initiation and inhibition of speech production and hand movement in both younger and older adults, and to examine aging effects on these temporal information processing mechanisms. We hypothesized that the motor reaction time would be slower in older compared with younger adults in both speech production and hand movement modalities. However, due to the absence of empirical evidence on the effects temporal predictability, and initiation vs. inhibition motor tasks, we took an exploratory approach to determine the effects of these factors in our data analyses.

Materials and method

Subjects

A total of 15 young (7 males and 8 females, age range 20–30 years old, mean: 22.6) and 15 older subjects (8 males and 7 females, age range 50–73 years old, mean: 63.8) participated in this study. Subjects reported no history of psychiatric or neurological conditions and they had no history of speech or hearing impairment. All subjects also had normal or corrected vision. Handedness of subjects was obtained using the Edinburgh handedness inventory; and all were right handed (score range 72–100). All study procedures, including recruitment, data acquisition, and informed consent were approved by the University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board, and subjects were monetarily compensated for their participation.

Experimental design

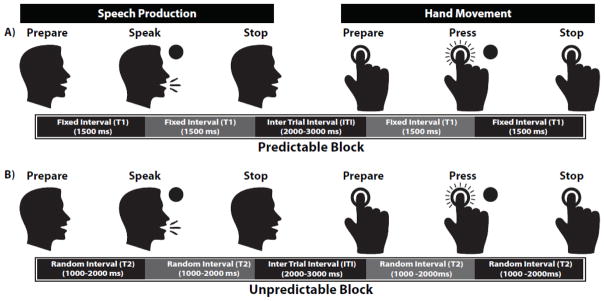

The experiment was conducted in a sound attenuated booth in which subjects performed the experimental tasks. The experiment consisted of two random-order tasks that involved initiation and inhibition of speech and hand movement. Subjects were instructed to prepare to perform one of the above motor tasks (speech or hand) following the onset of a relevant visual cue on the screen (figure 1). During each task, subjects were instructed to prepare for the cued movement and start pressing a button or vocalizing a steady vowel sound /a/ after a circle (go signal) appeared on the screen and stop after the circle disappeared (figure 1). Subjects were seated in a comfortable chair directly in front of the computer screen at a distance of about 15–20 inches to easily see the presented visual cues. The background of the screen was black and the visual cues appeared as white circles 1.5 inches in diameter. We designed two counterbalanced blocks within which subjects performed the speech and hand movement tasks in a randomized order: 1) temporally-predictable block, in which there was a fixed time interval of 1500 ms between the onset of the Visual Cue and Go signal, as well as the Go and Stop signals, and 2) temporally-unpredictable block in which the time internal between the Visual Cue and Go signal, as well as the Go and Stop signals, was randomized between 1000–2000 ms. During each block, a total number of 220 trials were collected, with approximately 110 trials for speech and hand movement initiation and inhibition. The inter-trial-interval (ITI) was 2–3 seconds in each block and subjects took a 5-minute break between the two blocks. All the experimental parameters, including Visual Cues, Go, and Stop signals and the time intervals between them were controlled by a custom-made program implemented in Max 5.0 (Cycling ‘74, San Francisco, CA). Additionally, timing within trials (T) and order of trials (speech and hand) were controlled by the Max program. Subjects’ responses including vowel sound vocalizations and button presses were recorded on a laboratory computer for the analysis of the reaction time. The speech signal was recorded through a head-mounted AKG condenser microphone (model C520) amplified by a Motu Ultralite-MK3 module.

Figure 1.

Experimental design for speech and hand reaction time task during A) predictable and B) unpredictable blocks. In each block, subjects were instructed to prepare to vocalize the steady vowel /a/ or press a button after a circle (go signal) appeared on the screen and stop after it disappeared. In this figure, T indicates the time interval between Preparation and Go, and the time interval between Go and Stop cues in either vocalization or button press task. For the predictable block, T was fixed at 1500 ms whereas for the unpredictable block it was randomized between 1000–2000 ms. ITI represents the inter-trial-interval which was about 2–3 seconds for both predictable and unpredictable conditions.

Reaction time analysis

For each subject, measures of reaction time were obtained for both predictable and unpredictable blocks (button press initiation and inhibition, speech initiation and inhibition). The reaction time for each condition was extracted using a custom-made MATLAB code by calculating the time difference between the onset of the go and stop visual cues and the initiation and inhibition of speech and hand movements, respectively. A repeated measure ANOVA was performed to examine effects of group (younger vs. older adults), timing (predictable vs. unpredictable), modality (Speech vs. hand) and task (initiation vs. inhibition) as well as their interaction on reaction time measures. The alpha level was 0.05 and post-hoc tests were corrected using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Results

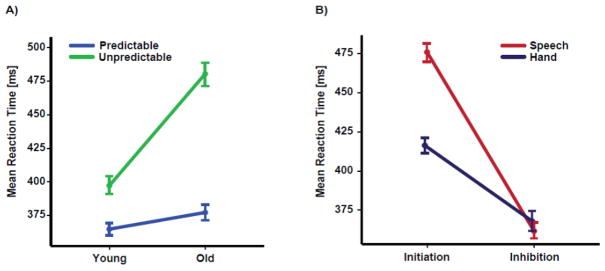

The results of the ANOVA yielded significant main effects of group (F(1,28) = 5.16, p = 0.03, η2 = 0.15), timing (F(1,28) = 24.78, p < 0.0001, η2 =0.47) and task (F(1,28) = 87.31, p < 0.0001, η2 = 0.74) on the measure of motor reaction time. The timing and group effects showed two-way interactions (F(1,28) = 6.75, p = 0.01, η2 = 0.20), and post hoc analysis revealed that younger adults were significantly faster than older adults during the unpredictable (t(118) = 3.54, p = 0.001) but not the predictable condition (t(118) = 0.89, p = 0.42) (see figure 2A). Moreover, the task effect showed two-way interactions with modality and task (F(1,28) = 8.19, p = 0.008, η2 = 0.22), indicating that hand initiation (t(118) = 3.22, p = 0.002), but not inhibition (t(118) = 0.26, p = 0.79), was significantly faster than speech initiation regardless of timing and group factors (see figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Panel A demonstrates the group (old vs. young) by timing (predictable vs. unpredictable) interaction for the mean reaction time, indicating that older adults were slower than younger adults when stimulus timing was unpredictable. Panel B demonstrates task (initiation vs. inhibition) by modality (speech vs. hand) interaction, indicating that movement initiation for speech was slower than hand irrespective of stimulus timing. In each panel, error bars show the standard error of the mean (SEM) for each experimental factor, separately.

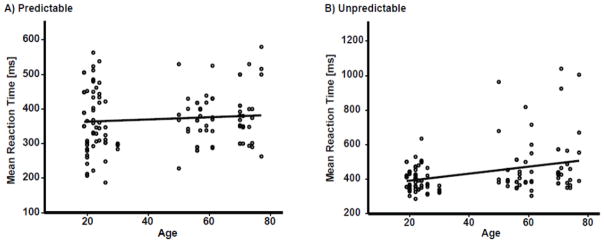

As mentioned above, the significant group by timing interaction indicated that the older adults were slower than the younger only when sensory stimuli were temporally unpredictable regardless of the response modality and task. Therefore, we probed the association between the age and motor temporal processing by using age as a scale variable. Given that there was no significant age by task or age by modality interactions in repeated-measures ANOVAs, the measures of motor reaction time were combined as a dependent variable across both tasks (initiation and inhibition) and response modalities (speech and hand), and age and stimulus timing were included as independent variables of interest in our regression analysis. Results of this analysis yielded a significant timing by age interaction (beta = 0.58, p = 0.009). Then, we ran follow up correlation analyses between the measures of reaction time and age for the predictable and unpredictable conditions, separately. The correlations were corrected for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni’s method. The results confirmed that age was positively correlated with reaction time for the unpredictable (r(118) = 0.33, p < 0.0001), but not the predictable (r(118) = 0.09, p = 0.37) stimulus timing condition (Figure 3). The correlation between age and reaction time was significant even after the task and modality factors were partialed out for both unpredictable (r(116) = 0.34, p < 0.0001) and predictable (r(116) = 0.10, p = 0.28) conditions. Finally, Levene’s test was preformed to examine whether the significant correlation for unpredictable condition was because of inequality of variances between younger and older adults’ reaction times. Results did not reveal a significant difference between variances for predictable (F(7,112) = 1.5, p = 0.16) and unpredictable (F(7,112) = 1.8, p = 0.10) conditions, indicating that significant correlation for temporally unpredictable stimuli was not accounted for by inequality of variances between younger and older adults’ reaction times.

Figure 3.

Correlation plots between the measures of reaction time and age overlaid across movement initiation and inhibition tasks in both speech and hand modalities. Correlations plots are demonstrated for A) temporally predictable, and B) temporally unpredictable stimuli, separately.

Discussion

The present study investigated how aging can affect motor reaction time in response to temporally predictable vs. unpredictable sensory stimuli during the initiation and inhibition of speech production and hand movement. We found that in general, motor reaction time was faster in response to temporally predictable vs. unpredictable sensory stimuli, irrespective of movement modality (speech vs. hand) and task (initiation vs. inhibition). However, our data showed that aging had a significant effect on motor response reaction time for temporally predictable vs. unpredictable sensory stimuli. While younger and older adults did not significantly differ in their responses to temporally predictable sensory stimuli, older adults were slower compared to younger adults in response to temporally unpredictable sensory stimuli, regardless of task and response modality. In addition, movement inhibition reaction time was faster than that for initiation, and this task effect was modality-specific. Finally, we found that participants’ age was positively correlated with movement reaction time only in response to temporally unpredictable stimuli.

The finding that older and younger adults’ reaction time was not significantly different for predictable stimuli is consistent with data from a previous studies by Chauvin et al. [39] in which it has been shown that older adults can use temporal cues to accelerate their motor response reaction time. In contrast, data from a study by Vallesi et al. [8] showed that older adults were slower than younger adults in response to temporally predictable stimuli. This inconsistency with respect to motor responses to predictable intervals might be in part due to the timing intervals that were used in Vallesi et al.’s study [8] in which they included short and long intervals for both predictable and unpredictable blocks. We argue that using mixed length intervals for predictable stimuli may have decreased the predictability effect of sensory stimuli in Vallesi et al.’s study [8], which was systematically different from the fixed intervals used in the present study.

Our results have suggested that the motor mechanisms of temporal predictive code are relatively spared for initiation and inhibition of speech and hand movements when stimulus timing is predictable. However, we found that movement production was significantly slower in older compared with younger adults specifically in response to temporally unpredictable sensory stimuli. In addition, the significant correlation between individuals’ age and their motor reaction time in response to unpredictable stimuli confirms that movement reaction times for sensory stimuli with unpredictable timing increases as people age. This correlation, along with slower reaction times for older adults during unpredictable timing, provides new insights into temporally specific age-related deficits in movement production mechanisms for initiation and inhibition of speech and hand motor responses.

The older adults’ slower motor reaction times for temporally unpredictable stimuli may be discussed in the context of temporal expectancy and the hazard function [17]. It has been suggested that the brain uses a hazard function to process temporally unpredictable intervals, whereas temporal expectancy supports the processing of predictable intervals [17]. Based on our findings, we suggest that aging is associated with decline of the hazard function, which can consequently lead to less precise estimates about the timing of upcoming imperative signals for movement initiation and inhibition during unpredictable timing. In contrast, temporal expectancy mechanisms are preserved for movement production in aging, suggesting that similar to younger adults, older subjects can use temporally predictable information to establish expectancy about the timing of an upcoming imperative signal and accelerate their motor response reaction time.

The finding that younger adults were faster than older adults in response to temporally unpredictable speech stimuli may reflect age-related changes in processing of complex sensory-motor stimuli. Older adults may experience increased difficulties in processing temporal information during a complex and more cognitively demanding sensory-motor task compared with younger adults, partially due to their limitation in allocation of neural resources during information processing for stimuli with unpredictable temporal patterns [40,41]. In this study, we used a fixed timing for temporally predictable stimuli during the motor reaction time task and this enabled subjects to establish a stronger temporal expectancy about the timing of the upcoming imperative signal. In contrast, timing variability in the unpredictable condition may have resulted in an increase in the level of complexity for temporal information processing, leading to diminished cognitive and sensorimotor performance in older adults compared with their younger counterparts.

We also found that hand movement initiation was faster than speech initiation regardless of timing and aging group. This supports our previous findings that in general, hand movement is executed with faster motor reaction time compared with that during speech production [5,6]. We suggest that this effect is accounted for by the difference in complexity of the executed motor task in speech vs. hand modality [42]. Our data suggest that due to the inherent complexity of speech production compared with hand movement, speech initiation requires activation and coordination of a large group of muscles (e.g. respiration, larynx, and articulation) at different levels of the speech subsystem compared to a less complex motor task for hand movement during button press [6].

Conclusion

In summary, our findings revealed that temporal predictive mechanisms in motor system are more prominently affected by aging in response sensory stimuli that follow a temporally unpredictable vs. predictable pattern. However, we found that for temporally predictable stimuli, movement production mechanisms are relatively spared in older adults compared with their younger counterparts. These findings provide new insights into the effects of aging the temporal aspects of information processing for movement production. Future studies are warranted to promote our understanding of other possible age-related effects on the underlying mechanisms involved in temporal information processing for speech production and hand movement.

Table 1.

Shows the mean reaction time and standard deviation (SD) for younger and older adults during initiation and inhibition of speech production and hand movement for both predictable and unpredictable stimulus timing conditions.

| Predictable | Unpredictable | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Initiation | Inhibition | Initiation | Inhibition | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Younger | Older | Younger | Older | Younger | Older | Younger | Older | |

| Speech | 436 ± 49 | 444 ± 68 | 340 ± 74 | 307 ± 38 | 460 ± 73 | 565 ± 165 | 380 ± 52 | 421 ± 155 |

| Hand | 377 ± 79 | 403 ± 54 | 304 ± 64 | 353 ± 54 | 401 ± 47 | 489 ± 145 | 347 ± 38 | 478 ± 145 |

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Drs. Chris Rorden and Allen Montgomery for their feedback on this manuscript. This research was supported by a grant from the NIH/NIDCD, Grant Number: K01-DC015831-01A1 (PI: Behroozmand), and by the Graduate Scholar Award for Aging Research received by Karim Johari from the University of South Carolina.

Footnotes

Author contributions

RB designed the research and KJ collected data for the experiments. KJ and RB analyzed the collected data. KJ, RB, and DO interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript and all authors reviewed and approved the final draft.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Statement of human and animal rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Disclosure

No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit on the author(s) or on any organization with which the author(s) is/are associated.

References

- 1.Klemmer ET. Time uncertainty in simple reaction time. Journal of experimental psychology. 1956;51(3):179–184. doi: 10.1037/h0042317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlin L. Reaction time as a function of foreperiod duration and variability. Journal of experimental psychology. 1959;58(2):185–191. doi: 10.1037/h0049152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertelson P, Boons J-P. Time uncertainty and choice reaction time. Nature. 1960;187(4736):531–532. doi: 10.1038/187531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drazin D. Effects of foreperiod, foreperiod variability, and probability of stimulus occurrence on simple reaction time. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1961;62(1):43–50. doi: 10.1037/h0046860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johari K, Behroozmand R. Premotor neural correlates of predictive motor timing for speech production and hand movement: evidence for a temporal predictive code in the motor system. Experimental brain research. 2017;235(5):1439–1453. doi: 10.1007/s00221-017-4900-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johari K, Behroozmand R. Temporal Predictability Modulates Reaction Time during Hand and Speech Movement Initiation and Inhibition. Human movement science. 2017;(54):41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behroozmand R, Sangtian S, Korzyukov O, Larson CR. A temporal predictive code for voice motor control: Evidence from ERP and behavioral responses to pitch-shifted auditory feedback. Brain Res. 2016;1636:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vallesi A, McIntosh AR, Stuss DT. Temporal preparation in aging: A functional MRI study. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47(13):2876–2881. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li C-SR, Krystal JH, Mathalon DH. Fore-period effect and stop-signal reaction time. Experimental brain research. 2005;167(2):305–309. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berchicci M, Lucci G, Spinelli D, Di Russo F. Stimulus onset predictability modulates proactive action control in a Go/No-go task. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015:9. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolpert DM. Computational approaches to motor control. Trends Cogn Sci. 1997;1(6):209–216. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(97)01070-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolpert DM, Flanagan JR. Motor prediction. Curr Biol. 2001;11(18):R729–R732. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bevan W, Hardesty DL, Avant LL. Response Latency with Constant and Variable Interval Schedules. Percept Motor Skill. 1965;20(3):969–972. doi: 10.2466/pms.1965.20.3.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vallesi A, McIntosh AR, Shallice T, Stuss DT. When Time Shapes Behavior: fMRI Evidence of Brain Correlates of Temporal Monitoring. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2009;21(6):1116–1126. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramautar JR, Kok A, Ridderinkhof KR. Effects of stop-signal probability in the stop-signal paradigm: The N2/P3 complex further validated. Brain Cognition. 2004;56(2):234–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koppe G, Gruppe H, Sammer G, Gallhofer B, Kirsch P, Lis S. Temporal unpredictability of a stimulus sequence affects brain activation differently depending on cognitive task demands. Neuroimage. 2014;101:236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coull JT, Cotti J, Vidal F. Differential roles for parietal and frontal cortices in fixed versus evolving temporal expectations: Dissociating prior from posterior temporal probabilities with fMRI. NeuroImage. 2016;141:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pachella RG. The interpretation of reaction time in information processing research. MICHIGAN UNIV ANN ARBOR HUMAN PERFORMANCE CENTER; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singleton W. Age and performance timing on simple skills. Old age in the modern world. 1955:221–231. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattes S, Ulrich R. Response force is sensitive to the temporal uncertainty of response stimuli. Perception & Psychophysics. 1997;59(7):1089–1097. doi: 10.3758/bf03205523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thickbroom G, Byrnes M, Sacco P, Ghosh S, Morris I, Mastaglia F. The role of the supplementary motor area in externally timed movement: the influence of predictability of movement timing. Brain Res. 2000;874(2):233–241. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niemi P, Näätänen R. Foreperiod and simple reaction time. Psychol Bull. 1981;89(1):133. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Logan GD, Burkell J. Dependence and Independence in Responding to Double Stimulation - a Comparison of Stop, Change, and Dual-Task Paradigms. J Exp Psychol Human. 1986;12(4):549–563. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.12.4.549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Binkofski F, Buccino G, Posse S, Seitz RJ, Rizzolatti G, Freund HJ. A fronto-parietal circuit for object manipulation in man: evidence from an fMRI-study. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11(9):3276–3286. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Binkofski F, Buccino G, Stephan KM, Rizzolatti G, Seitz RJ, Freund H-J. A parieto-premotor network for object manipulation: evidence from neuroimaging. Experimental Brain Research. 1999;128(1–2):210–213. doi: 10.1007/s002210050838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corballis MC. From mouth to hand: gesture, speech, and the evolution of right-handedness. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2003;26(02):199–208. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x03000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gentilucci M, Volta RD. Spoken language and arm gestures are controlled by the same motor control system. Q J Exp Psychol. 2008;61(6):944–957. doi: 10.1080/17470210701625683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gentilucci M, Campione GC, Dalla Volta R, Bernardis P. The observation of manual grasp actions affects the control of speech: A combined behavioral and Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation study. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47(14):3190–3202. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craik FI, Hay JF. Aging and judgments of duration: Effects of task complexity and method of estimation. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 1999;61(3):549–560. doi: 10.3758/bf03211972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balci F, Meck WH, Moore H, Brunner D. Animal models of human cognitive aging. Springer; 2009. Timing deficits in aging and neuropathology; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fozard JL, Vercruyssen M, Reynolds SL, Hancock P, Quilter RE. Age differences and changes in reaction time: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Journal of gerontology. 1994;49(4):P179–P189. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.p179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munoz D, Broughton J, Goldring J, Armstrong I. Age-related performance of human subjects on saccadic eye movement tasks. Experimental brain research. 1998;121(4):391–400. doi: 10.1007/s002210050473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levin O, Fujiyama H, Boisgontier MP, Swinnen SP, Summers JJ. Aging and motor inhibition: a converging perspective provided by brain stimulation and imaging approaches. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2014;43:100–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan Jerry HR, Thomas George E, Stelmach J. Aging and rapid aiming arm movement control. Experimental aging research. 1998;24(2):155–168. doi: 10.1080/036107398244292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Block RA, Zakay D, Hancock PA. Human aging and duration judgments: A meta-analytic review. Psychology and Aging. 1998;13(4):584–596. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.13.4.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Espinosa-Fernández L, Miró E, Cano M, Buela-Casal G. Age-related changes and gender differences in time estimation. Acta psychologica. 2003;112(3):221–232. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6918(02)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zanto TP, Pan P, Liu H, Bollinger J, Nobre AC, Gazzaley A. Age-related changes in orienting attention in time. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(35):12461–12470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1149-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schubotz RI, Friederici AD, Von Cramon DY. Time perception and motor timing: a common cortical and subcortical basis revealed by fMRI. Neuroimage. 2000;11(1):1–12. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chauvin JJ, Gillebert CR, Rohenkohl G, Humphreys GW, Nobre AC. Temporal orienting of attention can be preserved in normal aging. Psychology and aging. 2016;31(5):442–455. doi: 10.1037/pag0000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma HI, Trombly CA. Effects of task complexity on reaction time and movement kinematics in elderly people. Am J Occup Ther. 2004;58(2):150–158. doi: 10.5014/ajot.58.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jordan T, Rabbitt P. Response times to stimuli of increasing complexity as a function of ageing. British Journal of Psychology. 1977;68(2):189–201. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1977.tb01575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gajewski PD, Falkenstein M. Effects of task complexity on ERP components in Go/Nogo tasks. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2013;87(3):273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]