Abstract

Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), a pleiotropic cytokine belonging to the interleukin-6 family, is most often noted for its role in maintaining the balance between stem cell proliferation and differentiation. In rodents, LIF is expressed in both the fetal and adult testis; with the peritubular myoid (PTM) cells thought to be the main site of production. Given their anatomical location, LIF produced by PTM cells may act both on intratubular and interstitial cells to influence spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis respectively. Indeed, the leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR) is expressed in germ cells, Sertoli cells, Leydig cells, PTM cells and testicular macrophages, suggesting that LIF signalling via LIFR may be a key paracrine regulator of testicular function. However, a precise role(s) for testicular LIFR-signalling in vivo has not been established. To this end, we generated and characterised the testicular phenotype of mice lacking LIFR either in germ cells, Sertoli cells or both, to identify a role for LIFR-signalling in testicular development/function. Our analyses reveal that LIFR is dispensable in germ cells for normal spermatogenesis. However, Sertoli cell LIFR ablation results in a degenerative phenotype, characterised by abnormal germ cell loss, sperm stasis, seminiferous tubule distention and subsequent atrophy of the seminiferous tubules.

Introduction

The mammalian testis is a complex multicellular organ, separated into two distinct compartments which carry out its principle functions. In the adult testis, sperm production (spermatogenesis) occurs within the seminiferous tubules, and androgen biosynthesis (steroidogenesis) occurs in Leydig cells found in the interstitial space. Both these processes are subject to tight regulation at endocrine and paracrine levels. In addition to negative feedback control of testicular function by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, the importance of cross-talk between different cell types within the testis, required for the support of spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis, is well established1,2. For example; Leydig cell-derived androgens, signalling via androgen receptors in Sertoli cells and peritubular myoid cells, are essential for the maintenance of spermatogenesis3–6 whilst Sertoli cells, peritubular myoid cells and testicular macrophages have been shown to support Leydig cell development and steroidogenesis7–12. However, the full extent of the paracrine network which supports testicular function remains to be established. Identification of paracrine factors and/or mechanisms which regulate testicular function will be of benefit to the development of novel treatments for infertility and hypogonadism as well as for male contraceptive strategies.

Locally produced growth factors and cytokines have been suggested to play a role in the regulation of normal testicular development and function1,13. One such example is leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) which belongs to the multifunctional interleukin-6 (IL-6)-related family of cytokines14. LIF signalling is mediated by a heterodimeric receptor complex consisting of the leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR, also known as gp190), which binds LIF, and the signal transducing gp130 subunit common to the IL-6 family members15–17. Expression of both LIF and LIFR, as well as the gp130 signal transducer, has been detected in the rodent testis from fetal stages through to adulthood, suggesting LIF/LIFR signalling may play a role in normal testicular development and function18–21. Peritubular myoid cells have been identified as the principal source of LIF within the rat testis and, given the anatomical location of these cells, LIF has been hypothesised to be a paracrine regulator of both the tubular and interstitial compartments19. Interestingly, LIF-deficient males are reported to be fertile22 whereas complete knockout of the LIFR results in perinatal death due to pleiotropic defects including neurological and metabolic disturbances23. Whilst LIFR is expressed by somatic Sertoli cells, Leydig cells, peritubular myoid cells and macrophages, spermatogonia have been speculated to be the main target of LIFR signalling within the rat testis. This supposition is based on in vitro binding assays with biotinylated LIF and immunohistochemical detection of LIFR in testis sections18; however, the precise role(s) of testicular LIFR signalling remains to be established.

To definitively identify the role(s) of LIFR signalling in the testis in vivo, we generated multiple cell-specific LIFR-deficient mice and analysed their testicular phenotype to dissect out and characterise the role of LIFR signalling in the development and function of the testis. Firstly, to determine whether LIFR signalling is required for prenatal testis development, we validated a novel Lifr knockout allele (Lifrtm1b(EUCOMM)Hmgu) and assessed the impact of complete LIFR-loss on testicular structure in new-born mice at postnatal day 0. We next generated testis cell-specific Lifr-knockout mice to identify potential role(s) for LIFR signalling in the postnatal/adult testis. The data presented herein demonstrate that (i) LIFR is dispensable for prenatal testis development and (ii) in adulthood, LIFR is required in Sertoli cells, but not developing germ cells, for the maintenance of normal spermatogenesis.

Results

LIFR is Not Required for Prenatal Testicular Development

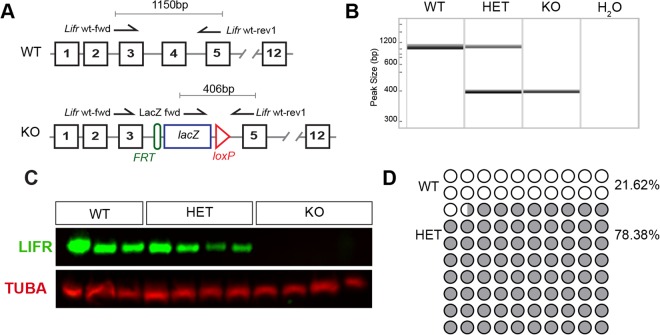

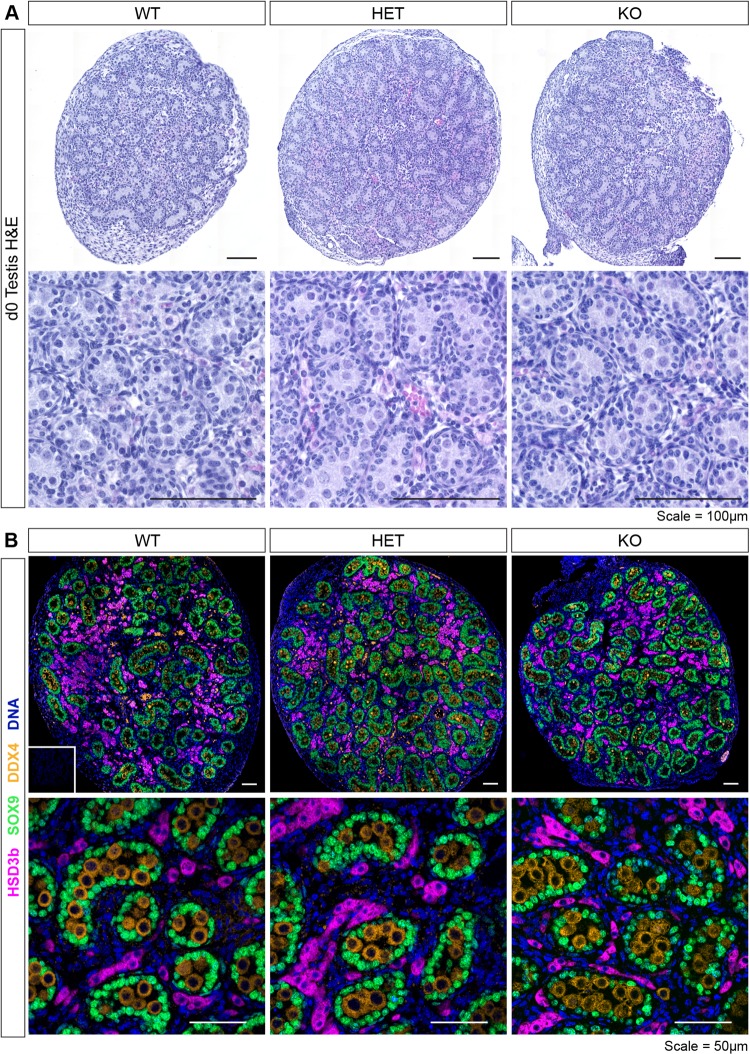

To determine whether there is a requirement for LIFR signalling in prenatal testis development, we first confirmed the absence of LIFR protein in new-born Lifrtm1b(EUCOMM)Hmgu mice. Wild-type (WT), heterozygous (HET) and homozygous (KO) mice were generated as described in the materials and methods. Genotyping primers were designed to detect the synthetic targeting cassette (Fig. 1A) and used to amplify genomic DNA isolated from tail tip biopsies to identify WT, HET and KO animals (Fig. 1B). Western blot analysis of neonatal whole brain protein extracts revealed that LIFR protein expression was completely abolished in homozygous Lifrtm1b(EUCOMM)Hmgu mice on postnatal day (d) 0 (Fig. 1C). At weaning, on d21, we noted a significant deviation from the expected Mendelian genotype ratios (Fig. 1D), reflecting absence of Lifr KO pups, consistent with previous reports of pre-weaning lethality in Lifr-KO mice23, and indicating that the Lifrtm1b(EUCOMM)Hmgu allele is a true loss of function allele. We next assessed the impact of LIFR ablation on development of the prenatal testis. Histological analysis revealed that testicular architecture was normal in LIFR-deficient animals at d0 (Fig. 2A). No differences in the immuno-localisation of SOX9, DDX4 and HSD3b in the testes of WT, HET and KO animals was observed (Fig. 2B), suggesting that establishment of the Sertoli, germ and fetal Leydig cell populations, and the structural arrangement of these cells in the testis occurs normally in fetal life in the absence of LIFR signalling.

Figure 1.

Validation of the Lifr-knockout allele. (A) Schematic of WT and KO alleles detailing the location of the genotyping primers and expected PCR product sizes. (B) Representative PCR analysis of genomic DNA isolated from tail-tip biopsies of neonatal mice identified wild-type (WT), heterozygous (HET) and homozygous (KO) animals. (C) Western blot analysis of neonatal brain tissue homogenates confirmed LIFR protein expression was abolished in KO animals. Tubulin-alpha (TUBA) was used as a loading control. Both LIFR and TUBA bands have been cropped from a single gel blot image which is included in the supplementary materials with the cropped areas highlighted. (D) Transgene inheritance in offspring derived from heterozygous matings based on genomic PCR of DNA isolated from ear-clip biopsies collected at weaning. Chi-squared analysis revealed a significant deviation from the expected Mendelian ratios (X2; p < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

LIFR signalling is not required for prenatal testis development. (A) Representative H&E stained testis sections from WT, HET and KO mice at post-natal day 0. Testes appeared morphologically normal, with fully formed seminiferous cords containing abundant spermatogonia. n = 3–5, scale = 100 µm. (B) Immunostaining for HSD3b (magenta), SOX9 (green) and DDX4 (gold) confirmed the presence of fetal Leydig cells, Sertoli cells and spermatogonia respectively, No obvious difference was noted between WT, HET and KO testes. Inset = primary antibody negative control. n = 3–5, scale = 50 µm.

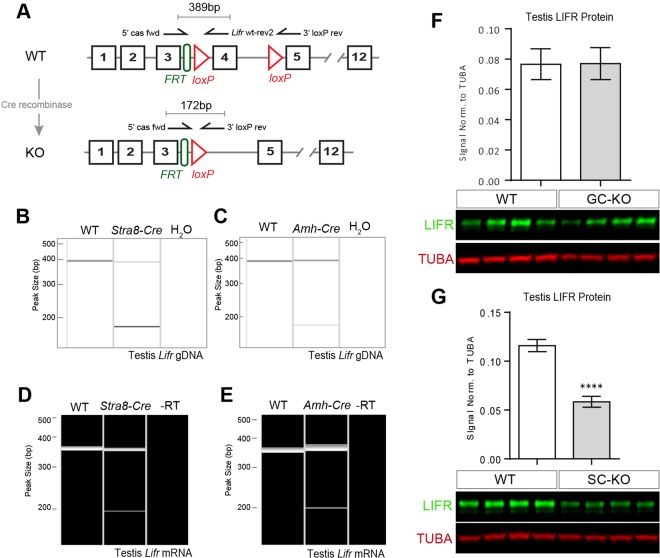

Generation of Germ Cell and Sertoli Cell specific Lifr-KO Mice

To circumvent the lethality observed in LIFR deficient animals, we utilised a conditional variant of the Lifr allele (Lifrtm1c(EUCOMM)Hmgu) to generate cell-specific LIFR knock-outs to identify potential role(s) for LIFR signalling in adult testis development/function. Lifr was selectively disrupted separately in germ cells (GC), Sertoli cells (SC) or both by breeding to the well-established Stra8-Cre24 and Amh-Cre25 lines. PCR analysis of genomic DNA isolated from the testes of heterozygote Stra8-Cre+/−; Lifrwt/tm1c and Amh-Cre+/−; Lifrwt/tm1c mice demonstrated recombination of the conditional Lifr allele upon exposure to either Cre-recombinase (Fig. 3A–C). Furthermore, PCR analysis of testicular cDNA revealed the presence of a mutant Lifr transcript following Cre-mediated recombination of Lifr gDNA, confirming that Lifr mRNA is expressed both in germ cells and in Sertoli cells (Fig. 3D,E respectively). According to the IMPC mutagenesis prediction, recombination of the loxP sequences flanking exon 4 of the Lifrtm1c(EUCOMM)Hmgu allele is predicted to frameshift the Lifr transcript such that a premature stop codon is introduced into exon 5, resulting in no protein product. Interestingly, Western blot analysis of whole adult testis protein extracts from Stra8-Cre+/−;Lifrtm1c/tm1c (GC-KO) and Amh-Cre+/−;Lifrtm1c/tm1c (SC-KO) mice revealed a significant reduction of LIFR protein in SC-KO but not GC-KO testes compared to their respective controls (Fig. 3F,G). This suggests that, although Lifr mRNA is expressed in the germ cell population, the Sertoli cell population (which translates Lifr mRNA into LIFR protein) may be the major target of LIFR signalling within the seminiferous tubule.

Figure 3.

Generation of germ cell and Sertoli cell-specific Lifr-KO mice. (A) Schematic of the conditional Lifr allele detailing the location of PCR primers designed to detect Cre-mediated recombination and the expected sizes of the PCR products. Germ cell and Sertoli cell Lifr-knockout mice were generated as described in materials and methods. Representative PCR analysis of genomic DNA isolated from the testes of heterozygote Stra8-Cre−/−;Lifrwt/tm1c and Stra8-Cre+/−;Lifrwt/tm1c (B) and Amh-Cre−/−;Lifrwt/tm1c and Amh-Cre+/−;Lifrwt/tm1c (C) mice confirmed recombination of the conditional Lifr allele upon Cre exposure. Representative PCR analysis of testicular cDNA from Stra8-Cre−/−;Lifrwt/tm1c and Stra8-Cre+/−;Lifrwt/tm1c (D) and Amh-Cre−/−;Lifrwt/tm1c and Amh-Cre+/−;Lifrwt/tm1c (E) mice confirmed Lifr mRNA is expressed in germ cells and Sertoli cells, evidenced by the presence of a mutant transcript following Cre-mediated gDNA recombination. Representative Western blot analysis of whole testis protein extracts from Stra8-Cre−/−;Lifrtm1c/tm1c (WT) and Stra8-Cre+/−;Lifrtm1c/tm1c (GC-KO) (F) and Amh-Cre−/−;Lifrtm1c/tm1c (WT) and Amh-Cre+/−;Lifrtm1c/tm1c (SC-KO) (G) mice. A significant reduction in testicular LIFR protein is observed only when Lifr is disrupted in Sertoli cells (SC-KO; unpaired t-test; p = 0.001). For GC-KO and SC-KO blots, both LIFR and TUBA bands have been cropped from single gel blot images which are included in the supplementary materials with the cropped areas highlighted. Tubulin-alpha (TUBA) was used as a loading control. Values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M of n = 7 samples per genotype.

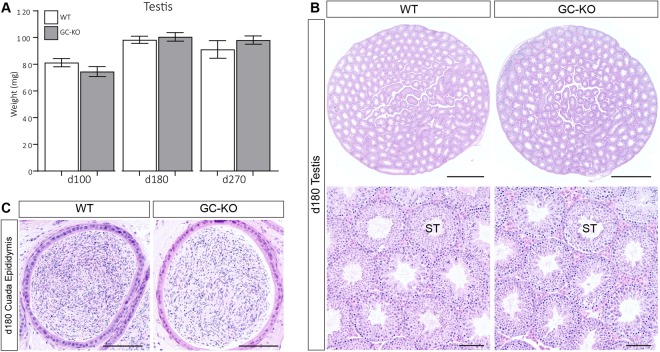

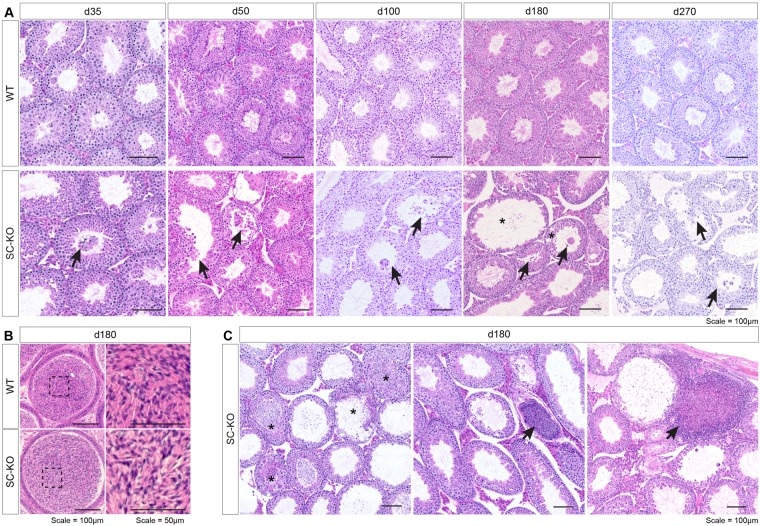

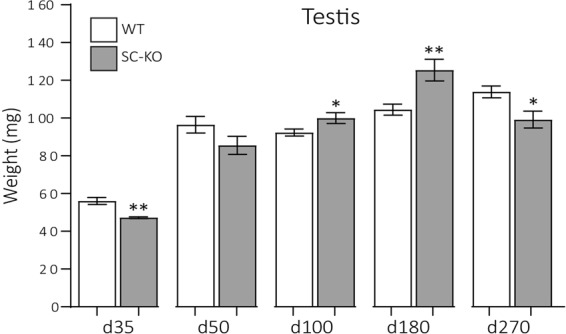

A Progressive, Degenerative Testicular Phenotype is observed in SC-KO Mice

We next sought to characterise the testicular phenotype of our conditional Lifr mutants. We first assessed phenotypic changes in GC-KO animals. Testis weight did not differ between WT and GC-KO mice up to d180 (Fig. 4A) and no difference in testicular architecture was observed between WT and GC-KO mice (Fig. 4B). In addition, morphologically mature sperm were present in the cauda epididymides of both WT and GC-KO mice (Fig. 4C). These data unequivocally demonstrate that LIFR is not required in the germ cell population for qualitatively normal spermatogenesis to occur. Conversely, a striking testicular phenotype was observed in SC-KO animals. Initially, testis weight was reduced in SC-KO animals at d35 (Fig. 5), consistent with germ cell sloughing from the seminiferous epithelium, evidence of which was occasionally noted in SC-KO testes (Fig. 6A). Significant degeneration of the seminiferous epithelium was observed from d180 in SC-KO animals (Fig. 6A), accompanied first by increased testis weight at d180, followed by reduced testis weight at d270 (Fig. 5). While seminiferous tubule degeneration/atrophy was widespread, there were still tubules within SC-KO testes that appeared normal (Fig. 6A). Additionally, morphologically mature spermatids were present in both WT and SC-KO cauda epididymides at d180 (Fig. 6B), suggesting that LIFR-deficient Sertoli cells can still support all steps of spermatogenesis. From d180, the seminiferous tubules appeared dilated with larger lumens. When quantified, the luminal percentage volume was increased two-fold in the SC-KO testis and the percentage volume of the seminiferous epithelium was reduced by 25% compared to WT controls (Supplemental Fig. 1). Serial sectioning through entire SC-KO testes revealed regions of seminiferous tubule, often in close proximity to the rete testis, with increasing concentrations of sloughed germ cells/cellular debris and signs of apparent sperm stasis (Fig. 6C). The observed phenotype is consistent with increased fluid back-pressure inside the testis similar to that observed in several other rodent models26–30. To determine whether there is an additive effect of LIFR ablation from both germ cells and Sertoli cells together, we generated double SC-GC Lifr knockout mice. Testis histology in double mutants was similar to that of the SC-KO animals, further confirming that Sertoli cells, and not germ cells, are the major functional site of seminiferous tubule LIFR signalling (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Figure 4.

Testicular morphology is normal in GC-KO mice. (A) No difference in testis weight was observed between WT and GC-KO mice up to d270 (unpaired t-tests). Values are expressed as mean ± S.E.M of n = ≥10 mice per age/genotype. (B) Representative H&E staining of WT and GC-KO testes at d180. No difference in testis morphology was noted between WT and GC-KO mice. ST = seminiferous tubule, scale = 1 mm in top panels and 100 µm in bottom panels. (C) Representative H&E analysis of the cauda epididymis confirmed the presence of morphologically mature spermatids in both WT and GC-KO mice. Scale = 100 µm.

Figure 5.

Testis weight is altered in SC-KO mice. At d35, a significant decrease in testis weight was observed in SC-KO animals (unpaired t-test; p = 0.0028, n = 7–9). At d50, testis weight was similar between WT and SC-KO animals (unpaired t-test; p = 0.1129, n = 9). At d100, a slight but significant increase in testis weight was observed in SC-KO mice (unpaired t-test; 0.0354, n = 13). This increase became more exaggerated at d180 (Mann-Whitney U-test; p = 0.0027; n = 12–16). By d270, a significant decrease in testis weight was observed in SC-KO mice (unpaired t-test; p = 0.0195; n = 9–11). Values are expressed mean ± S.E.M.

Figure 6.

A Progressive degenerative testicular phenotype is observed in SC-KO mice. (A) Representative H&E staining of WT (top) and SC-KO testes (bottom) up to d270. Testis histology was largely normal in SC-KO up to d100 although evidence of germ cell sloughing was occasionally observed (arrows). At d180, more wide-spread degeneration of the seminiferous epithelium was observed in SC-KO testes. While morphologically normal tubules were present in the d180 SC-KO testis, a large proportion of tubules appeared distended and vacuolation of the seminiferous epithelium was noted (asterisks). (B) Morphologically mature spermatids were present in cauda epididymides of both WT and SC-KO mice at d180. (C) Serial sectioning through entire SC-KO testes revealed sections of tubule with increasing concentrations of sloughed germ cells/cellular debris (asterisks) and signs of apparent sperm stasis (arrows). Scale bars = 100 µm.

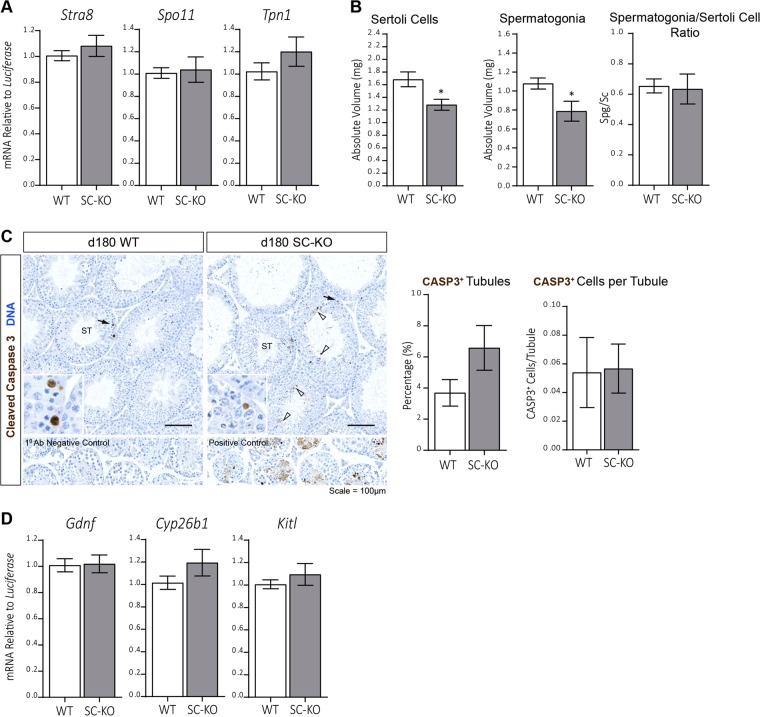

Sertoli cell and Spermatogonia Volume is Reduced in 6-month old SC-KO Mice

To determine whether sloughing of a specific germ cell population was responsible for the tubule obstruction observed in SC-KO mice, we next measured the expression of germ cell-specific ‘biomarker’ mRNAs in WT and SC-KO testes. No difference in the expression of Stra8, Spo11 or Tpn1 was detected between WT and SC-KO testes at d180 (Fig. 7A), suggesting no major deficit in the spermatogonia, spermatocyte or spermatid populations respectively. However, stereological analysis of the seminiferous epithelium revealed a reduction in Sertoli cell and spermatogonia volume per testis in SC-KO mice at d180 by 24% and 27% respectively (Fig. 7B). The spermatogonia/Sertoli cell ratio was similar between SC-KO and WT controls (Fig. 7B), suggesting Sertoli cell support for spermatogonia is retained in SC-KO testes. No difference in spermatocyte or spermatid volume per testis was noted between WT control and SC-KO mice (Supplemental Fig. 3). We next asked whether increased apoptosis may explain the observed reduction in the number of Sertoli cells and spermatogonia. When quantified, no difference in the proportion of activated CASP3-positive tubules per section, or CASP3-positive cells in the basal region of seminiferous tubules was noted between WT and SC-KO animals (Fig. 7C). Finally, to determine whether a perturbation in the spermatogonial stem cell (SSC) niche may be responsible for the decreased number of spermatogonia, we measured the mRNA expression of Sertoli-cell derived factors which have been shown to be important for proper maintenance of SSCs31. Expression of Gdnf, Cyp26b1 and Kitl was similar in WT and SC-KO testes (Fig. 7D), suggesting that dysregulation of the SSC niche may not explain the reduction in spermatogonia in SC-KO testes.

Figure 7.

Reduced Sertoli cell and spermatogonia volume in SC-KO testes. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of spermatogonia (Stra8), spermatocyte (Spo11) and spermatid (Tpn1) specific mRNAs. Expression levels were similar between WT and SC-KO testes at d180 (unpaired t-test, n = 9–10). (B) Stereological analysis revealed a reduction in the absolute nuclear volume of Sertoli cells and spermatogonia in the SC-KO testis at d180 (unpaired t-test; p = 0.0172 and 0.0325 respectively; n = 7). Spermatogonia/Sertoli cell ratio is maintained in the SC-KO testis (unpaired t-test, n = 7). (C) Representative immunostaining for activated CASP3 (brown), as a marker of apoptosis, in WT and SC-KO testes at d180. No difference in the number of CASP3-positive tubules, or CASP3-positive cells lining the basal region of the tubules (black arrows, higher magnification insets) was observed between WT and SC-KO testes (unpaired t-test; n = 5–6). CASP3 immunoreactivity was occasionally observed throughout the seminiferous epithelium (open arrowheads) in SC-KO animals. Primary antibody negative control and experimentally-induced Sertoli cell death positive controls are included. Scale bars = 100 µm. (D) mRNA expression of Gdnf, Cyp26b1 and Kitl was similar between WT and SC-KO testes (unpaired t-tests, n = 9–10). All values are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M.

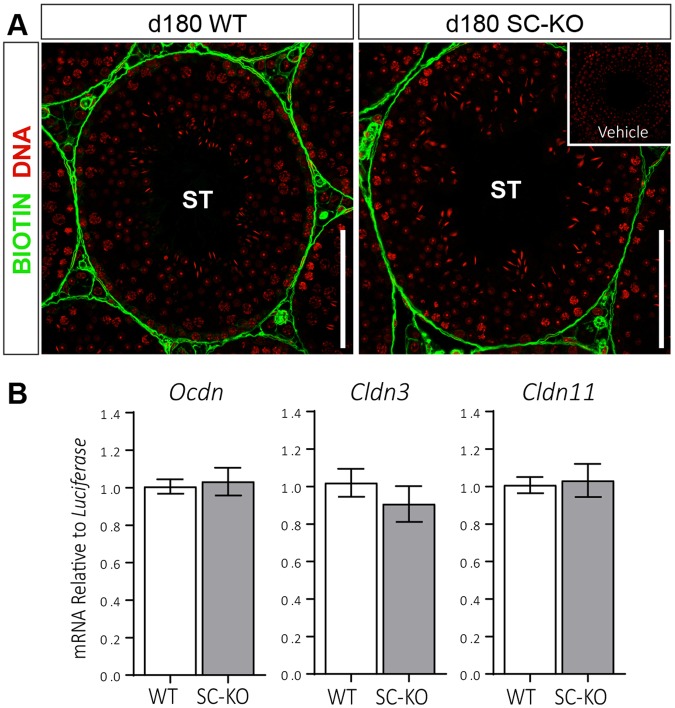

Blood-Testis-Barrier Function Remains Intact in the SC-KO Testis

The blood-testis-barrier (BTB) plays an important role in maintaining the appropriate intratubular environment required for normal spermatogenesis. Previous reports have suggested a role for IL-6 family cytokines, of which LIF is a member, in the regulation of BTB function32,33. We therefore assessed the ability of LIFR-deficient Sertoli cells to maintain the integrity of the BTB. Functional assessment of the BTB using a biotin tracer confirmed the BTB remains intact in the SC-KO testis (Fig. 8A), consistent with normal mRNA expression of the BTB associated genes Ocdn, Cldn3 or Cldn11 (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

Blood-testis-barrier function remains functional in SC-KO mice. (A) A biotin tracer injected into the testis interstitium was restricted to the interstitial compartment between seminiferous tubules (ST) confirming the blood-testis-barrier remained intact in SC-KO mice at d180. Scale bars = 100 µm. (B) Expression of the blood-testis-barrier associated mRNAs Ocdn, Cldn3 or Cldn11 was unaltered in SC-KO testes at d180 (unpaired t-test; n = 9–10). Values are expressed as means ± S.E.M.

Discussion

Development and function of the mammalian testis is subject to endocrine regulation by the HPG axis, as well as a complex suite of paracrine factors, which ensure the adequate production of both sperm and androgens in adult males. In the present study, we set out to identify the contribution of leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR) signalling to testis development and function. Using a series of mutant Lifr mouse models, we found that LIFR does not appear to be crucial for prenatal testicular development. Conversely, LIFR in Sertoli cells, but not germ cells, is required for the maintenance of normal structure/function of the seminiferous tubules in adulthood.

Both Lif and Lifr, are expressed in the prenatal rodent testis from embryonic day (e) 12.518–20 suggesting a role in testis organogenesis. In the present study, we observed a normal testicular architecture, characterised by fully formed seminiferous cords containing Sertoli and germ cells, and abundant interstitial fetal Leydig cells, in LIFR-deficient mice on the day of birth, suggesting that LIFR is dispensable for the establishment of a morphologically normal testis. Our analysis is limited to morphological assessment of testis structure at d0, thus we cannot rule out the possibility that LIFR-loss affects testicular organogenesis at earlier developmental time points, or in subtle ways which may not be readily apparent at d0. It has been reported previously that the number and morphology of primordial germ cells (PGC) is normal in LIFR-deficient mice when analysed at e10.5-13.523, which would be consistent with our observations. Conversely, a slight reduction in PGC number was noted in gp130-deficient male fetuses20. Together, this suggests that further, more detailed analysis may be warranted. Whilst neither study made comment upon the developing somatic components of the fetal mouse testis, a recent study which aimed to identify genes involved in congenital abnormalities of the kidney and urogenital tract (CAKUT), noted a form of cryptorchidism in a CAKUT patient heterozygous for a hypomorphic LIFR mutation34. The authors suggest that disruption of murine Lifr also results in a potential form of cryptorchidism, characterised by an abnormal ligament attaching the testis to the dorsal aorta, present at e18.5. Such a defect was not noted in the present study, possibly owing to the genetic background of the Lifr mutants – in the above study animals were maintained on an outbred Ztm:NMRI background which may be more susceptible to developmental urogenital defects35. Alternatively, regression of this structure may occur between e18.5 and d0 – the time point at which our Lifr mutants were analysed. It may also be possible that such a defect went unnoticed during the course of the present studies. Nevertheless, our analysis of d0 testes demonstrate that LIFR is not required for the development of normal prenatal testicular structure.

Constitutive Lifr deletion results in a lethal phenotype prior to weaning thus LIFR deficient mice cannot be used for the study of adult testis development/function. We therefore used a Cre/loxP approach to disrupt Lifr in germ cells and Sertoli cells. Cre recombinase is reported to be active in spermatogonia from postnatal day 3 in the TgStra8-icre1Reb mouse line24 which we used to disrupt Lifr in germ cells. In the rat testis, spermatogonia have been suggested to be a major target of LIFR signalling18, although this conclusion was arrived at through the comparison of d9 spermatogonia to d20 somatic cells. Surprisingly, analysis of our GC-KO mice suggests that LIFR is in fact dispensable in germ cells, from the spermatogonial stage onward, for normal spermatogenesis in mice. Functional redundancy between LIF and other IL6-family members signalling through gp130 provide a possible explanation, however, a previous report using Tnap-cre to delete gp130 from primordial germ cells reported no phenotype in mutant male mice20. However, no mention of the age of the animals was made in that study, thus the development of a progressive spermatogenic defect in ageing gp130-deficient animals cannot be ruled out.

A number of studies have documented wide-spread expression of Lif and Lifr in both germ and somatic cell populations in the adult rodent testis18–21, implicating LIF/LIFR signalling as a potential regulator of testicular function. Indeed, in vitro experiments have demonstrated that LIF can enhance the survival of gonocytes and Sertoli cells in a primary co-culture system36 and that LIF stimulates spermatogonial proliferation and/or survival when added to primary cultures of seminiferous tubule segments18. In vitro data suggest that LIF/LIFR signalling is active in rat Sertoli cells, but not germ cells21 indicating that the proliferative and/or anti-apoptotic effects of LIF on gonocytes/spermatogonia are likely mediated by the Sertoli cells present in the cultures. The data presented herein are consistent with this hypothesis, as we report that LIFR is dispensable in germ cells for normal spermatogenesis to occur, but Sertoli cell LIFR ablation appears to cause spermatogenic defects. Reduced numbers of spermatogonia in SC-KO testes was not be explained by increased apoptosis or obvious perturbation to the spermatogonial stem cell niche. Reduction of spermatogonia could be explained by altered proliferation of differentiating type A, intermediate and type B spermatogonia or may be secondary to reduced Sertoli cell numbers in the SC-KO testis. As we did not note any difference in apoptosis within the spermatogonia/Sertoli cell compartment of the seminiferous tubules of adult SC-KO mice, reduced Sertoli cell number could be due to altered proliferation during pubertal development, this requires further investigation.

Based on our histological analyses, postnatal testis development appears largely normal when LIFR is deleted from the Sertoli cell population. However, whilst LIFR-deficient Sertoli cells are able to support the production of mature spermatids, evidence of germ cell sloughing from the seminiferous epithelium was noted highlighting a requirement for LIFR for the maintenance of normal spermatogenesis. Despite an apparent reduction in Sertoli cells and spermatogonia, testis weight was significantly increased in d180 SC-KO mice and a large proportion of tubules appeared dilated. This is likely a result of increased fluid backpressure inside the testis due to occlusion of the testicular excurrent ductal system by sloughed germ cells30,37. However, the molecular mechanism(s) behind disruption to the seminiferous epithelium remains to be elucidated. Germ cell sloughing is often noted following toxicant-induced or genetic disruption to the Sertoli cell microtubule network30,38–41. Interestingly, the cytoplasmic form of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3; which is engaged following LIFR/gp130 signal transduction) has been implicated in the modulation of microtubule dynamics42–44. This raises the possibility that perturbed microtubule dynamics in LIFR-deficient Sertoli cells may in part explain premature germ cell exfoliation in SC-KO testes. Additionally, disruption of Sertoli cell microtubules results in decreased seminiferous tubule fluid production45 which could impair the efficiency of the excurrent ductal system resulting in blockage/sperm stasis as observed in SC-KO testes; this requires further investigation. Nevertheless, the studies conducted herein provide, to the best of our knowledge, the first in vivo evidence that LIFR signalling is required for normal testicular function in adulthood. Specifically, we have identified a requirement for Sertoli cell LIFR in the maintenance of normal spermatogenic function, further widening our understanding of the paracrine factors which support the function of this fundamentally important cell.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

Experimental procedures and animal breeding and maintenance were approved by University of Edinburgh Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body and were carried out with licenced permission under project licences 60/4200 and 70/8804 held by Professor Lee B. Smith in line with the UK Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986. Reference was made to the ARRIVE guidelines46 in the preparation of this manuscript.

Transgenic Mice

Mice carrying a reporter-tagged Lifr knockout allele (Lifrtm1b(EUCOMM)Hmgu) were obtained from the IMPC project (http://www.mousephenotype.org/) and maintained on a C57Bl/6Ntac background. Constitutive Lifr-knockout mice were generated by intercrossing male and female Lifrwt/tm1b mice to generate Lifrwt/wt, Lifrtwt/tm1b and Lifrtm1b/tm1b offspring (herein referred to as WT, HET and KO respectively). Mice carrying a conditional Lifr allele (Lifrtm1c(EUCOMM)Hmgu) were also obtained from the IMPC project. Germ cell and Sertoli cell-specific Lifr knockout mice were generated by mating Lifrtm1c(EUCOMM)Hmgu mice to mice expressing Cre-recombinase under the control of either the stimulated by retinoic acid-8 promoter (Stra8; TgStra8-icre1Reb)24 or Anti-Müllerian Hormone promoter (AMH; TgAmh-cre1Flor)25 respectively. First generation (F1) Cre+/−; Lifrwt/tm1c and Cre−/−; Lifrwt/tm1c were crossed to produce Cre+/−; Lifrtm1c/tm1c and Cre−/−; Lifrtm1c/tm1c animals in the second generation (F2; referred to as GC-KO and SC-KO respectively). Genomic DNA isolated from tail or ear biopsies was used to genotype mice by standard PCR techniques using either using either BioMix™ PCR reaction buffer (Bioline Reagents Ltd, UK) or Type-it Mutation Detect PCR Kit (QIAGEN Ltd., UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Details of genotyping assays are listed in Table 1. Lifr recombination was assessed in genomic DNA isolated from testis biopsies of Cre+; Lifrwt/tm1c mice. PCR products were analysed using the QIAxcel capillary electrophoresis system (Qiagen, UK).

Table 1.

Details of genotyping assays.

| Assay | Forward Primer(s) | Reverse Primer(s) | Buffer | Product Sizes (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifr tm1b | Lifr wt-fwd ggaaaccctggtattgtgga LacZ-fwd ccagttggtctggtgtca |

Lifr wt-rev1 catgccacagtgcgacag | Type-it |

Lifrwt - 1150 Lifrtm1b - 406 |

| Lifr tm1c | Lifr wt-fwd ggaaaccctggtattgtgga | Lifr wt-rev2 ggctgtcctggaactcactc | Type-it |

Lifrwt - 244 Lifrtm1c - 418 |

| Lifr tm1d | 5′ cas-fwd aaggcgcataacgataccac | 3′ loxP-rev actgatggcgagctcagacc Lifr wt-rev2 ggctgtcctggaactcactc |

Type-it |

Lifrtm1c - 389 Lifrtm1d - 172 |

| Amh-Cre | Amh-cre fwd cacatcaggcccagctctat Il2-fwd ctaggccacagaattgaaagatct |

Amh-cre rev gtgtacaggatcggctctgc Il2-rev gtaggtggaaattctagcatcatcc |

Biomix |

Amh-cre - 180 Il2 - 330 |

| Stra8-Cre | Str8-cre fwd gtgcaagctgaacaacagga Il2-fwd ctaggccacagaattgaaagatct |

Stra8-cre rev agggacacagcattggagtc Il2-rev gtaggtggaaattctagcatcatcc |

Biomix |

Stra8-cre - 260 Il2 - 330 |

Tissue Collection

Animals were sacrificed in the morning (8:00am - 11:00am) in accordance with Schedule 1 of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986. Exposure to an increasing concentration of carbon dioxide, followed by confirmation of permanent cessation of the circulation by palpitation was used for adult mice. Neonatal animals were sacrificed by destruction of the brain. Testis weights were recorded and tissues were either frozen on dry ice for storage at −80 °C or immersed in Bouin’s fixative (Clin-Tech Ltd, UK) for 6 hr. Bouin’s fixed tissues were processed, embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned at 5 µm for histological analyses.

Histology and Immunostaining

For histological analyses, Bouin’s fixed, paraffin embedded tissue sections were stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) following standard protocols. Testicular cell composition was estimated using standard stereological techniques involving point counting of cell nuclei to determine the absolute volume (mg) of Sertoli cell and germ cell nuclei3. Immuno-staining of an individual antigen of interest was performed using chromogenic immunostaining procedures as previously described7. For detection of multiple antigens on the same tissue section, multiplexed immuno-staining was performed using fluorogenic immunostaining procedures as described previously47. Details of the antibodies used are listed in Table 2. Images were acquired using either an LSM 780 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, UK) or an Axio Scan Z.1 slide scanner (Carl Zeiss, UK). CASP3-positive seminiferous tubules and CASP3-positive cells per tubule were scored from an average of 165 tubules across 2 separate testis sections per animal.

Table 2.

Details of antibodies used for immunohistochemistry.

| Target | Antigen Retrieval | Primary Antibody | Secondary Reagent | Detection Method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Catalogue No. | Dilution | Source | Cat. No. | Dilution | |||

| HSD3b | Citrate pH 6 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology Germany | sc30820 | 1:2000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology Heidelberg, Germany | sc-2961 | 1:200 | ChαG HRP Tyramide |

| SOX9 | Tris-EDTA pH 9 | Merk Millipore USA | AB5535 | 1:4000 | Vector Laboratories Burlingame, CA, USA | PI-1000 | 1:200 | GαR HRP Tyramide |

| CASP3 | n/a | Cell Signalling Technology Netherlands | 9661 S | 1:300 | Anti-rabbit Poly-HRP-IgG Leica Biosystems, UK | DS 9800 | n/a | Poly-HRP DAB |

| COUP-TFII | Citrate pH 6 | Persus Proteomics Japan | PP-H7147-00 | 1:1000 | Agilent Technologies (DAKO) Cheadle, UK | P0447 | 1:500 | GαM HRP Tyramide |

| PDGFRb | Citrate pH 6 | Abcam UK | ab32570 | 1:1500 | Vector Laboratories Burlingame, CA, USA | PI-1000 | 1:200 | GαR HRP Tyramide |

| DDX4 | Citrate pH 6 | Abcam UK | ab13840 | 1:1000 | Vector Laboratories Burlingame, CA, USA | PI-1000 | 1:200 | GαR HRP Tyramide |

ChαG = Chicken anti-Goat; GαR = Goat anti-Rabbit; GαM = Goat anti-Mouse; HRP = Horseradish Peroxidase; DAB = 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine.

Western Blotting

Western blotting for LIFR was performed as previously described41 with minor modifications. Briefly, proteins (30 µg) were separated on a 7% Tris-Acetate polyacrylamide gel (Thermo Fisher, UK) and transferred onto an Immobilon-Fl membrane (Merk Millipore, UK). Blots were probed with primary antibodies against LIFR (sc-659; 1:400; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Germany) and TUBBA (ab6160; 1:5000; Abcam, UK). Primary antibodies were detected using Goat anti-Rabbit IRDye® 800CW (925-32211, 1:10,000; LI-COR Biosciences, UK) and Goat anti-Rat IRDye® 680RD (925-68076; 1:10,000; LI-COR Biosciences, UK) secondary antibodies. Blots were imaged using the LI-COR Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR biosciences, UK). Full blot images are included in supplementary materials.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was isolated from frozen testis tissue and cDNA synthesis was carried out as previously described48. Real-time PCR was carried using the ABI Prism 7900HT Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, UK), in 384-well format, with the Roche Universal ProbeLibrary (Roche, UK). qRT-PCR assays were designed using the Universal ProbeLibrary Design Centre tool (https://lifescience.roche.com/en_gb/brands/universal-probe-library.html). Details of the assays used are listed in Table 3. Data were analysed using the ΔΔCt method.

Table 3.

Details of qRT-PCR assays.

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | UPL Probe | Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ocdn | GCGGAAAGAGTTGACAGTCC | ATCTCCTGGGCCACTTCAG | 25 | 99 |

| Cldn3 | TGGGAGCTGGGTTGTACG | CAGGAGCAACACAGCAAGG | 26 | 99 |

| Cldn11 | TGGAGTGGCCAAGTACAGG | GACAATGGCGCAGAGAGC | 20 | 93 |

| Stra8 | TTGACGTGGCAAGTTTCCT | AGTTGCAGGTGGCAAACATA | 107 | 102 |

| Spo11 | GGCTCCTGGACGACAACTT | CAGATCTGGAACGCCCTTT | 18 | 99 |

| Tpn1 | AGCCGCAAGCTAAAGACTCA | CGGTAATTGCGACTTGCAT | 91 | 96 |

| Gdnf | GCTCAAAATTGTGACAACCTCA | CAGAGGGTCTGGAACGACAT | 107 | 104 |

| Cyp26b1 | AACATGGCAAGGAGATGACC | TTGCATGATCAAGGATGTGC | 17 | 99 |

| Kitl | GCTGCTGGTGCAATATGCT | GATAAATGCAAGTGATAATCCAAGTTT | 50 | 97 |

Functional Integrity of the Blood-Testis-Barrier

Permeability of the blood-testis-barrier to a biotin tracer was carried out as previously described49 with minor modifications. Briefly, EZ-link sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (Thermo Scientific, UK) was freshly prepared as a 10 mg/mL solution in 0.01 M MgCl2 in PBS. 10–15 uL of biotin solution was injected into the testis under the tunica albuginea immediately after sacrifice, 10–15 uL of 0.01 M MgCl2 in PBS was injected into the contralateral testis as a control. Testes were left on ice for 30 mins and then fixed and processed as described above. The localisation of the biotin tracer was visualised by incubation with Streptavidin Alexa Fluor™ 546 conjugate (S11225, Thermo Scientific, UK), diluted 1:200 in PBS, for 1 hr at room temperature. Tissue sections were imaged using an LSM 780 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, UK).

Statistical Analyses

Data were statistically analysed using GraphPad Prism 7.02 software (GraphPad software Inc., USA). The D’Agostino & Pearson or Shapiro-Wilk normality test was first used to assess the distribution of data. Comparisons were made between two groups using either an unpaired, two tailed, t-test (for parametric data) or the Mann-Whitney U-test (for non-parametric data). Differences between more than two groups conforming to a Gaussian distribution were identified using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). For one-way ANOVA, means were compared between groups using Dunnet’s post hoc analysis. Transgene inheritance was assessed using a Chi-square test. In each case, a p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We kindly thank Professor Richard Sharpe and Mr Mike Millar for useful advice relating to the manuscript. We are also grateful for technical assistance from Lyndsey Boswell and Gary Menzies of the University of Edinburgh SuRF core and Mr Mike Dodds of the Central Biological Services team. This work was supported by a BBSRC DTP grant (BB/J01446X/1) and a Medical Research Council Programme Grant award (MR/N002970/1) to LBS. IMPC mice were obtained from MRC Harwell funded by the Medical Research Council for generating (53658) and phenotyping (53650) the mice. The authors declare no competing interests (financial or otherwise as defined by Nature Research), or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reported in this paper.

Author Contributions

L.B.S. and M.C. designed the study. M.C., L.M., S.S., N.A., D.R. and A.D. carried out experimental work. M.C., L.B.S. and P.W.F.H. analysed the results. S.W. provided research tools. M.C. and L.B.S. wrote and revised the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-30011-w.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gnessi L, Fabbri A, Spera G. Gonadal peptides as mediators of development and functional control of the testis: an integrated system with hormones and local environment. Endocrine reviews. 1997;18:541–609. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.4.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlatt S, Meinhardt A, Nieschlag E. Paracrine regulation of cellular interactions in the testis: factors in search of a function. European journal of endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 1997;137:107–117. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1370107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Gendt K, et al. A Sertoli cell-selective knockout of the androgen receptor causes spermatogenic arrest in meiosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:1327–1332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308114100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willems A, et al. Sertoli cell androgen receptor signalling in adulthood is essential for post-meiotic germ cell development. Molecular reproduction and development. 2015;82:626–627. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welsh M, Saunders PT, Atanassova N, Sharpe RM, Smith LB. Androgen action via testicular peritubular myoid cells is essential for male fertility. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2009;23:4218–4230. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-138347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Shaughnessy PJ, Verhoeven G, De Gendt K, Monteiro A, Abel MH. Direct action through the sertoli cells is essential for androgen stimulation of spermatogenesis. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2343–2348. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rebourcet D, et al. Sertoli Cells Maintain Leydig Cell Number and Peritubular Myoid Cell Activity in the Adult Mouse Testis. PloS one. 2014;9:e105687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rebourcet D, et al. Sertoli cells control peritubular myoid cell fate and support adult Leydig cell development in the prepubertal testis. Development (Cambridge, England) 2014;141:2139–2149. doi: 10.1242/dev.107029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welsh M, et al. Androgen receptor signalling in peritubular myoid cells is essential for normal differentiation and function of adult Leydig cells. International journal of andrology. 2012;35:25–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2011.01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Gendt K, et al. Development and function of the adult generation of Leydig cells in mice with Sertoli cell-selective or total ablation of the androgen receptor. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4117–4126. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen PE, Chisholm O, Arceci RJ, Stanley ER, Pollard JW. Absence of colony-stimulating factor-1 in osteopetrotic (csfmop/csfmop) mice results in male fertility defects. Biology of reproduction. 1996;55:310–317. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod55.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeFalco T, et al. Macrophages Contribute to the Spermatogonial Niche in the Adult Testis. Cell Rep. 2015;12:1107–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedger MP, Meinhardt A. Cytokines and the immune-testicular axis. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2003;58:1–26. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0378(02)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Muller-Newen G, Schaper F, Graeve L. Interleukin-6-type cytokine signalling through the gp130/Jak/STAT pathway. The Biochemical journal. 1998;334(Pt 2):297–314. doi: 10.1042/bj3340297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ip NY, et al. CNTF and LIF act on neuronal cells via shared signaling pathways that involve the IL-6 signal transducing receptor component gp130. Cell. 1992;69:1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90634-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gearing DP, et al. The IL-6 signal transducer, gp130: an oncostatin M receptor and affinity converter for the LIF receptor. Science. 1992;255:1434–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.1542794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gearing DP, et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor receptor is structurally related to the IL-6 signal transducer, gp130. The EMBO journal. 1991;10:2839–2848. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorval-Coiffec I, et al. Identification of the Leukemia Inhibitory Factor Cell Targets Within the Rat Testis. Biology of reproduction. 2005;72:602–611. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.034892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piquet-Pellorce C, Dorval-Coiffec I, Pham MD, Jegou B. Leukemia inhibitory factor expression and regulation within the testis. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1136–1141. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.3.7399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molyneaux KA, Schaible K, Wylie C. GP130, the shared receptor for the LIF/IL6 cytokine family in the mouse, is not required for early germ cell differentiation, but is required cell-autonomously in oocytes for ovulation. Development (Cambridge, England) 2003;130:4287–4294. doi: 10.1242/dev.00650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenab, S. & Morris, P. L. Testicular leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and LIF receptor mediate phosphorylation of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT)-3 and STAT-1 and induce c-fos transcription and activator protein-1 activation in rat Sertoli cells but not germ cells. Endocrinology139, 10.1210/endo.139.4.5871 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Stewart CL, et al. Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor. Nature. 1992;359:76–79. doi: 10.1038/359076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ware, C. B. et al. Targeted disruption of the low-affinity leukemia inhibitory factor receptor gene causes placental, skeletal, neural and metabolic defects and results in perinatal death. Development (Cambridge, England)121 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Sadate-Ngatchou PI, Payne CJ, Dearth AT, Braun RE. Cre recombinase activity specific to postnatal, premeiotic male germ cells in transgenic mice. genesis. 2008;46:738–742. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lecureuil C, Fontaine I, Crepieux P, Guillou F. Sertoli and granulosa cell-specific Cre recombinase activity in transgenic mice. Genesis. 2002;33:114–118. doi: 10.1002/gene.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Hara L, Welsh M, Saunders PT, Smith LB. Androgen receptor expression in the caput epididymal epithelium is essential for development of the initial segment and epididymal spermatozoa transit. Endocrinology. 2011;152:718–729. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeffs B, et al. Blockage of the Rete Testis and Efferent Ductules by Ectopic Sertoli and Leydig Cells Causes Infertility in Dax1-Deficient Male Mice. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4486–4495. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.10.8447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heuser A, Mecklenburg L, Ockert D, Kohler M, Kemkowski J. Selective Inhibition of PDE4 in Wistar Rats Can Lead to Dilatation in Testis, Efferent Ducts, and Epididymis and Subsequent Formation of Sperm Granulomas. Toxicologic Pathology. 2013;41:615–627. doi: 10.1177/0192623312463783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hess RA. Disruption of estrogen receptor signaling and similar pathways in the efferent ductules and initial segment of the epididymis. Spermatogenesis. 2014;4:e979103. doi: 10.4161/21565562.2014.979103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakai M, et al. Acute and Long-term Effects of a Single Dose of the Fungicide Carbendazim (Methyl 2-Benzimidazole Carbamate) on the Male Reproductive System in the Rat. Journal of andrology. 1992;13:507–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia TX, Farmaha JK, Kow S, Hofmann M-C. RBPJ in mouse Sertoli cells is required for proper regulation of the testis stem cell niche. Development (Cambridge, England) 2014;141:4468–4478. doi: 10.1242/dev.113969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, H. et al. Interleukin-6 disrupts blood-testis barrier through inhibiting protein degradation or activating phosphorylated ERK in Sertoli cells. 4, 4260, 10.1038/srep04260 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Perez CV, et al. Loss of occludin expression and impairment of blood-testis barrier permeability in rats with autoimmune orchitis: effect of interleukin 6 on Sertoli cell tight junctions. Biology of reproduction. 2012;87:122. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.101709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kosfeld A, et al. Mutations in the leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR) gene and Lifr deficiency cause urinary tract malformations. Human molecular genetics. 2017;26:1716–1731. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deerberg F, Müller-Peddinghaus R. Vergleichende Untersuchungen über die Häufigkeit von Spontanerkrankungen und Spontantodesfällen bei weiblichen konven-tionellen und bei spezifiziert pathogenfreien NMRI/Han-Mäusen. Z. Versuchstierk. 1970;12:341–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Miguel MP, et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor and ciliary neurotropic factor promote the survival of Sertoli cells and gonocytes in coculture system. Endocrinology. 1996;137:1885–1893. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.5.8612528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hess RA, Nakai M. Histopathology of the male reproductive system induced by the fungicide benomyl. Histology and histopathology. 2000;15:207–224. doi: 10.14670/HH-15.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakai M, Hess RA. Morphological changes in the rat Sertoli cell induced by the microtubule poison carbendazim. Tissue & cell. 1994;26:917–927. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(94)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Markelewicz RJ, Jr., Hall SJ, Boekelheide K. 2,5-hexanedione and carbendazim coexposure synergistically disrupts rat spermatogenesis despite opposing molecular effects on microtubules. Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2004;80:92–100. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell LD, Malone JP, MacCurdy DS. Effect of the microtubule disrupting agents, colchicine and vinblastine, on seminiferous tubule structure in the rat. Tissue & cell. 1981;13:349–367. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(81)90010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith LB, et al. KATNAL1 Regulation of Sertoli Cell Microtubule Dynamics Is Essential for Spermiogenesis and Male Fertility. PLOS Genetics. 2012;8:e1002697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ng DC, et al. Stat3 regulates microtubules by antagonizing the depolymerization activity of stathmin. The Journal of cell biology. 2006;172:245–257. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan B, et al. STAT3 Association with Microtubules and Its Activation Are Independent of HDAC6 Activity. DNA and Cell Biology. 2015;34:290–295. doi: 10.1089/dna.2014.2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verma NK, et al. STAT3-Stathmin Interactions Control Microtubule Dynamics in Migrating T-cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:12349–12362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807761200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richburg JH, Redenbach DM, Boekelheide K. Seminiferous Tubule Fluid Secretion Is a Sertoli Cell Microtubule-Dependent Process Inhibited by 2,5-Hexanedione Exposure. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1994;128:302–309. doi: 10.1006/taap.1994.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving Bioscience Research Reporting: The ARRIVE Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. PLOS Biology. 2010;8:e1000412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Hara L, York JP, Zhang P, Smith LB. Targeting of GFP-Cre to the Mouse Cyp11a1 Locus Both Drives Cre Recombinase Expression in Steroidogenic Cells and Permits Generation of Cyp11a1 Knock Out Mice. PloS one. 2014;9:e84541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Hara L, et al. Autocrine androgen action is essential for Leydig cell maturation and function, and protects against late-onset Leydig cell apoptosis in both mice and men. The FASEB Journal. 2015;29:894–910. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-255729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elkin ND, Piner JA, Sharpe RM. Toxicant-induced leakage of germ cell-specific proteins from seminiferous tubules in the rat: relationship to blood-testis barrier integrity and prospects for biomonitoring. Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2010;117:439–448. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.