Abstract

A poorly exploited paradigm in the antimicrobial therapy field is to target virulence traits for drug development. In contrast to target-focused approaches, antivirulence phenotypic screens enable identification of bioactive molecules that induce a desirable biological readout without making a priori assumption about the cellular target. Here, we screened a chemical library of 678 small molecules against the invasive hyphal growth of the human opportunistic yeast Candida albicans. We found that a halogenated salicylanilide (N1-(3,5-dichlorophenyl)-5-chloro-2-hydroxybenzamide) and one of its analogs, Niclosamide, an FDA-approved anthelmintic in humans, exhibited both antifilamentation and antibiofilm activities against C. albicans and the multi-resistant yeast C. auris. The antivirulence activity of halogenated salicylanilides were also expanded to C. albicans resistant strains with different resistance mechanisms. We also found that Niclosamide protected the intestinal epithelial cells against invasion by C. albicans. Transcriptional profiling of C. albicans challenged with Niclosamide exhibited a signature that is characteristic of the mitochondria-to-nucleus retrograde response. Our chemogenomic analysis showed that halogenated salicylanilides compromise the potential-dependant mitochondrial protein translocon machinery. Given the fact that the safety of Niclosamide is well established in humans, this molecule could represent the first clinically approved antivirulence agent against a pathogenic fungus.

Introduction

Candida albicans is an ascomycete fungus that is an important commensal and opportunistic pathogen in humans. Systemic infections resulting primarily from this yeast and the filamentous fungus, Aspergillus fumigatus, are associated with mortality rates of 50% or greater despite current therapies1–3. Therapeutic options are limited to treatment with mainly three antifungal classes, namely polyenes, azoles and echinocandins4. These compounds target the specific fungal biological process of ergosterol metabolism (azoles and polyenes) and cell wall β-1,3-glucan synthesis (echinocandins). However, these drugs have serious side effects such as nephrotoxicity and/or create complications such as resistance and interactions with other commonly prescribed drugs. There are currently a limited number of novel antifungal molecules on the drug discovery pipelines and most of them target the same cellular processes as azoles and echinocandins5–7. Thus, these molecules will most likely face the same limitations in term of resistance and toxicity. These considerations highlight the urgent need to identify novel targets and strategies for antifungal therapies.

The pathogenicity of C. albicans is mediated by different factors such as invasive filamentation, biofilm formation and the ability to escape the immune system4. A relatively new but poorly exploited paradigm in the antimicrobial therapy field is to target virulence traits for drug development8–10. In contrast to target-focused approaches, phenotypic screens enable identification of bioactive molecules that induce a desirable biological readout without making a priori assumption about the cellular target. Additionally, compounds identified by phenotypic screens are by definition cell permeable and engage their target with sufficient affinity. Taking into consideration the commensal lifestyle of C. albicans, suppressing its growth in different niches inside the host will perturb the microbial flora equilibrium and lead to other opportunistic infections11. Specific inhibition of fungal virulence determinants without affecting commensal growth represents thus an attractive approach.

C. albicans is a polymorphic fungus that are able to reversibly shift to different morphologies including yeast, pseudohyphae and true hyphae forms. Hyphae are long tubular cells that are associated with the invasion of organs and tissues of the human host during Candidemia episodes.

In addition to ensuring a physical force required to penetrate host cells, the hyphae state is characterized by an enhanced adhesiveness and allow to the fungal cells to escape the from phagocytes and to conquer niches where nutrient conditions are not limiting12. Furthermore, even if hyphae are not essential for the formation of C. albicans biofilms, they are determinant for the compression strength and the resistance to mechanical dislocation of this highly resistant growth lifestyle13. Thus, antivirulence therapy based on molecules that inhibit hyphae formation could have substantial benefits on managing fungal infections. Moreover, antivirulence agents might provide an alternative strategy to circumvent antifungal resistance by disarming fungal resistant pathogens from their virulence factors14.

Proof of principle for this concept has been demonstrated in different investigations15–20. Fazly et al. characterized a small molecule called filastatin that inhibits C. albicans filamentation, adhesion and virulence16, yet, the molecular mechanism by which this molecule acts remain elusive. Recently, screening of small molecules that are being clinically tested for different pathologies identified two antifilamentation compounds that also perturbed endocytosis17. However, these compounds were also found to inhibit the commensal yeast growth at the effective antifilamentation concentrations.

In this study, we screened a chemical library of 678 small molecules that were preselected for bioactivity in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae and have well-balanced hydrophilic-lipophilic properties allowing the crossing of both the hydrophilic fungal cell wall and the lipophilic membrane. We found that N1-(3,5-dichlorophenyl)-5-chloro-2-hydroxybenzamide (TCSA: Tri-Chloro-Salicyanilide, for simplified nomenclature), a halogenated salicylanilide, was a potent antifilamentation molecule and inhibited also biofilm formation of both C. albicans and the multi-resistant yeast C. auris. The TCSA analog, Niclosamide, that is an FDA-approved anthelmintic agent, exhibited a similar anti-filamentation and anti-biofilm activities and conferred a significant protective activity to intestinal epithelial cells against fungal invasion. Both genome-wide transcriptional profiling and chemical-genetic approach were used to gain insight into the mechanism of action associated with the antivirulence activity of the halogenated salicylanilides (HSA). We found that HSA-mediated antivirulence activity is likely related to the perturbation of the fungal mitochondrial protein import machinery.

Results

Phenotypic screening of yeast-bioactive small molecules for inhibition of hyphal growth

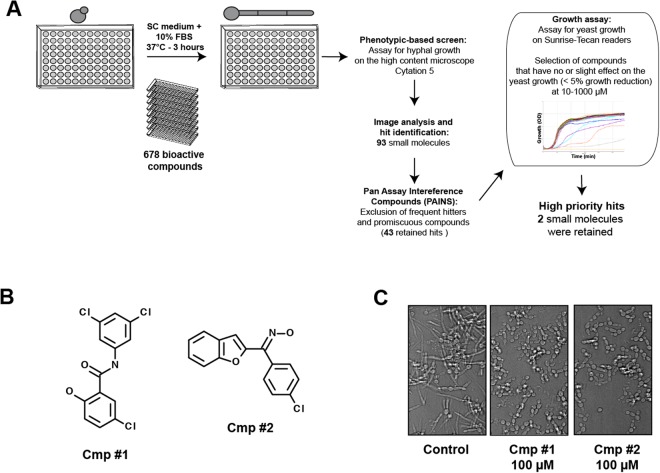

To identify small molecules with antivirulence properties the yeast bioactive small molecule library21 was screened for compounds that inhibit hyphal formation (Fig. 1A). Compounds of this chemical library were preselected for bioactivity in S. cerevisiae and have well-balanced hydrophilic-lipophilic properties allowing the crossing of both the hydrophilic fungal cell wall and the lipophilic membrane. C. albicans cells were grown in 96-well under hyphae-promoting conditions (SC-10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)) for 3 h at 37 °C in the presence of the bioactive compounds. The ability of each compounds to inhibit C. albicans SC5314 strain morphogenesis was assessed by imaging each well using the high-content microscope Cytation 5. This primary screen identified 93 molecules with anti-filamentation activity at 100 µM (70–80% of C. albicans cells with no germ tubes). A total of 50 promiscuous molecules with chemical structures similar to pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) associated with antifungal activity22 were removed from the hit list of the primary screen. Inhibition of filamentation could be associated with the fact that small molecules are very toxic which might systematically alter all developmental process of a fungal cell such as morphogenesis. To rule out cytotoxic molecules that impaired growth per se, the 43 retained hits were assayed for their ability to inhibit growth of yeast cells growing at 30 °C. Through this process, a subset of five molecules were selected which were then assayed for their potency using a quantitative dose-response filamentation inhibition assay. Among the five hits, we found two molecules that had a significant effect on filamentous growth at pharmacological concentrations of 1–10 µM (data not shown). The effect of this compounds on C. albicans filamentation were confirmed using a new batch of powders from different suppliers (Fig. 1B,C).

Figure 1.

Hyphal growth inhibition assay in C. albicans. (A) Workflow of small-molecule high-throughput screen for hyphal growth inhibition of C. albicans SC5314 strain. (B) Chemical structure of the antifilamentation compound 1 (Cmp #1; N1-(3,5-dichlorophenyl)-5-chloro-2-hydroxybenzamide) and (Cmp #2; 3-Chloro-aryl(benzofuran-2-yl) ketoxime). (C) Antifilamentation activity of the Cmp #1 and Cmp #2 at 100 µM. C. albicans SC5314 strain was grown under hyphae-promoting conditions (SC medium supplemented with 10% FBS) for three hours at 37 °C.

Compound #1 (N1-(3,5-dichlorophenyl)-5-chloro-2-hydroxybenzamide or TCSA) is a halogenated form of salicylanilide scaffold. Salicylanilides are widely used as antiparasitic veterinary drugs against helminths and ectoparasites23. The salicylanilide Niclosamide (5-chloro-salicyl-(2-chloro-4-nitro) anilide) was approved by the FDA to treat tape worm infection in humans24 and has been recently shown to have anti-cancer and anti-diabetic activities25,26. Recently, HSA including Niclosamide and Oxyclozanide were repurposed as alternative antibiotic therapy against clinical resistant isolates of Staphylococcus aureus27. The compound #2 (3-Chloro-aryl(benzofuran-2-yl) ketoxime) had chemical features with previously described biological activities. This compound had both oxime and benzofuran residues that are associated with the antifungal activity of many molecules28–33. Derivatives of compound #2 were also shown to be active against C. albicans by targeting the N-myristoyltransferase, Nmt134,35. While in our conditions this molecule had a slight effect on the growth of the yeast form of C. albicans (10% of inhibition at 1 mM), other studies using different growth medium (RPMI) had shown a strong growth reduction at 15 µM32. Based on this, we decided to focus our downstream investigation on compound #1.

TCSA and Niclosamide inhibit C. albicans filamentation without affecting the commensal yeast growth

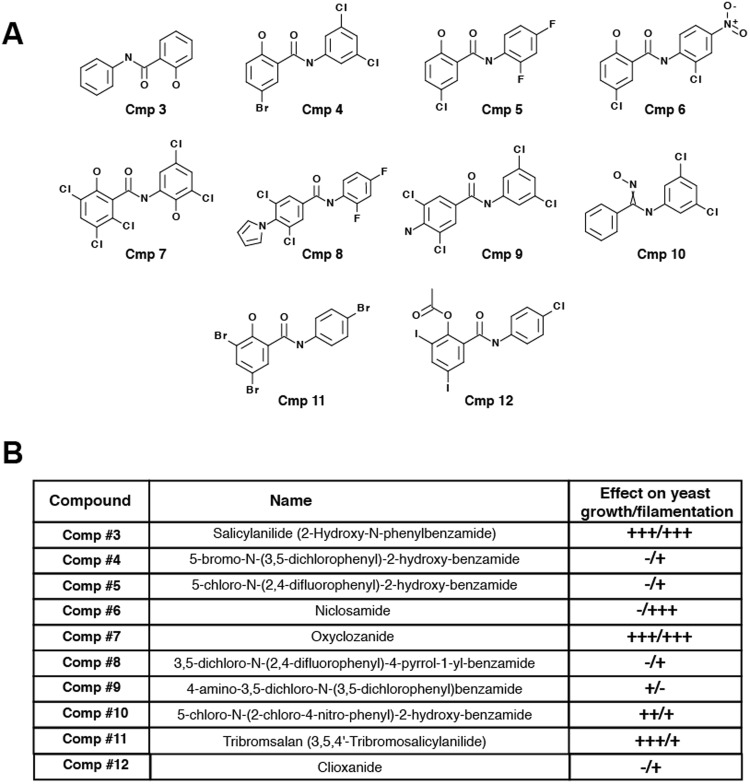

Commercially available HSA analogs 3–12 were purchased and tested on both growth and filamentation (Fig. 2A). With the exception of Niclosamide (compound #6), all tested salicylanilide derivatives impaired the growth of C. albicans at concentration of 20 µM (>50% inhibition of the growth as compared to the control) (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the salicylanilide scaffold alone had a strong effect on the fungal growth, suggesting that halogenation potentiates the antifilamentation rather than yeast antigrowth effect of TCSA and Niclosamide. Both TCSA and Niclosamide have no significant impact on the growth of the yeast form (Fig. 3A,B). At 50 µM, TCSA inhibited hyphae elongation by 90%, as compared to the control, while Niclosamide abolished completely C. albicans filamentation (Fig. 3C,D).

Figure 2.

Effect of halogenated salicylanilide analogs on C. albicans yeast and hyphal growths. (A) Chemical structures of different commercially available salicylanilides. (B) Effect of TCSA analogs on both yeast and hyphal growths of C. albicans. To assess the effect of each compound on yeast growth at concentrations ranging from 1 to 100 µM, C. albicans SC5315 strain was grown on SC medium at 30 °C for 24 hours. Hyphae-promoting conditions were obtained by incubating C. albicans cells on SC medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C for 3 hours and salicylanilides (1–100 µM). (+++), (++) and (+) indicate strong, medium and low inhibition, respectively. Absence of inhibition was indicated by (−).

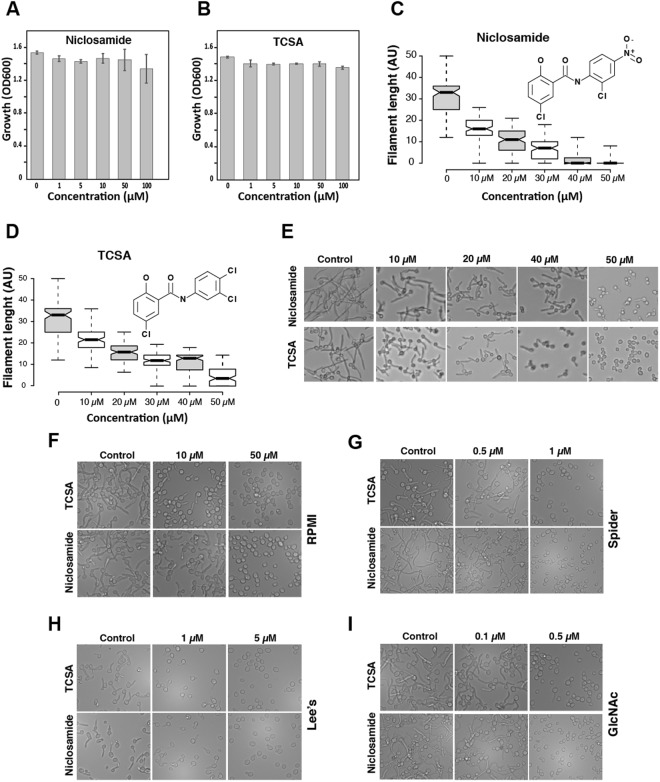

Figure 3.

Niclosamide and TCSA abolished C. albicans hyphal growth promoted by different cues. Effect of Niclosamide (A) and TCSA (B) on the growth of the commensal yeast form. C. albicans SC5315 strain was exposed at different concentrations of the two HSA in SC medium and grown at 30 °C for 24 h. (C) Dose-response effect of Niclosamide (C) and TCSA (D) on filament length of C. albicans visualized by box plots. Bold lines in the box plots show the medians. C. albicans SC5315 strain was grown under hyphae-promoting conditions (SC + 10% FBS) in the absence (control) or the presence of HSA (10–50 µM). Filament length were measured for at least 100 cells and shown as arbitrary unit (AU). (E–I) DIC micrographs showing the dose-response antifilamentation effect of Niclosamide and TCSA on C. albicans hypha grown on SC medium supplemented with 10% FBS serum (E) or on RPMI (F), Spider (G) and Lee’s (H) media, and SC with N-acetyl-D- glucosamine (GlcNAc) (I).

Since the yeast-to-hyphae transition is triggered by different environmental cues, the antifilamentation effect of TCSA and Niclosamide was also tested and confirmed using other hyphae-promoting media. In RPMI medium, both compounds were effective at concentrations similar to those in SC supplemented with 10% FBS (Fig. 3E). Interestingly, in Spider, N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and Lee’s media the antifilamentation activity of TCSA and Niclosamide were enhanced and a complete abolition of the C. albicans hyphal growth were perceived at concentration ranging from 0.5 to 5 µM (Fig. 3F–I). Both TCSA and Niclosamide exhibited antifilamentation activity on other non-albicans Candida species including C. dubliniensis and C. tropicalis (data not shown).

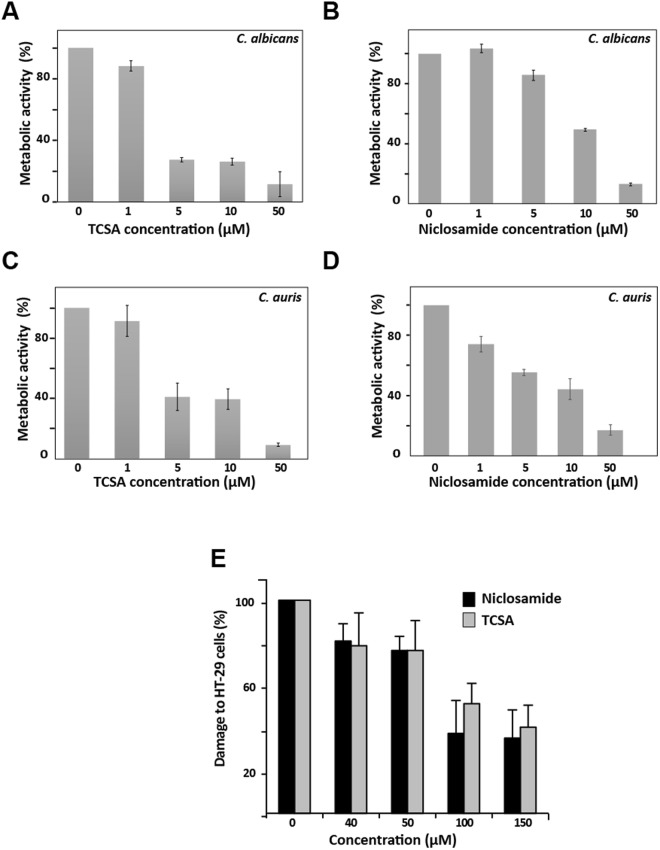

TCSA and Niclosamide inhibit C. albicans biofilm formation

The effect of the two HSA were also assessed on C. albicans biofilm, a highly resistant sessile growth lifestyle associated with the contamination of medical devices. Niclosamide and TCSA impaired considerably the ability of C. albicans to establish biofilms (Fig. 4A,B). Antibiofilm activity were noticed at 1 µM (12% inhibition) and 5 µM (15% inhibition) for TCSA and Niclosamide, respectively. Both compounds were active on the biofilm of the emerging multi-drug resistant yeast, C. auris, and their inhibitory effect was perceived at 1 µM (Fig. 4C,D). For both Candida species, biofilm inhibition was greater with TCSA as compared to Niclosamide.

Figure 4.

Niclosamide and TCSA antivirulence activity are expanded to the inhibition of biofilm formation and host invasion. Effect of TCSA (A,C) and Niclosamide (B,D) on biofilm formation of C. albicans (A,B) and C. auris (C,D). The effect of HSA on biofilm formation of both C. albicans SC5314 and C. auris HDQ-RPCau1 strains was assessed using the metabolic colorimetric assay based on the reduction of XTT. Results represent growth inhibition (%) and are shown as the mean of at least three independent replicates. (E) Both Niclosamide and TCSA attenuate damage of enterocytes cells caused by C. albicans. Damage of the human epithelial intestinal cells HT-29 infected by C. albicans SC5314 strain was assessed using LDH release assay. Cell damage was calculated as percentage of LDH activity of HSA-treated experiment relatively to that of the control experiment (C. albicans invading HT-29 cells in the absence of HSA). Results are represented as the mean of three independent replicates.

Niclosamide and TCSA attenuate damage of intestinal epithelial cells caused by C. albicans

Since Niclosamide and TCSA inhibited the formation of invasive hyphae, we wanted to check whether it conferred a protective activity for host cells against fungal invasion. C. albicans-mediated damage of the human colon epithelial HT-29 cells was quantified based on the LDH release assay in cells treated or not with different concentrations of the two HSA. Our data showed clearly that both antifilamentation compounds significantly reduced, but not completely abolished, the damage to HT-29 enterocytes (Fig. 4E). The protective effect was perceived at 40 µM of either Niclosamide or TCSA (~20% reduction of enterocyte invasion). At concentration ≥100 µM, Niclosamide and TCSA attenuated HT-29 cell damage by 63% and 49%, respectively.

Niclosamide induces retrograde response in C. albicans

To gain insight into the mechanism of action associated with the antifilamentation effect of HSA, transcriptional profiling was undertaken on cells grown under hyphae-stimulating conditions in the presence of 50 µM of Niclosamide. Gene ontology analysis showed that transcripts related to drug transport and, carbohydrate, trehalose and glyoxylate metabolisms were induced while genes of cell wall, filamentation and lipid metabolism including ergosterol (ERG6, ERG25, CYB5, NDT80), sphingolipids (LCB2, FEN1, LAC1) and phosphoglycerides (AYR1, CHO2, PEL1, EPT1, YEL1, DGK1) were downregulated (Table 1). We also found that genes encoding different proteins that control the activity of different protein kinases such as those modulating cell cycle progression (CLN3, CLG1, SOL1, CIP1) were repressed in response to Niclosamide. Gene expression alteration of eight genes including four upregulated (ICL1, MLS1, MDR1, GDH2) and four downregulated (ZRT2, ERG25, LAC1, CDC47) transcripts was confirmed using qPCR (Table S1).

Table 1.

Gene function and biological process associated with C.

| GO category | Gene name | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated transcripts | ||

| Drug transport | CDR1, CDR11, QDR3, MDR1, TPO3, MTE4, SGE11, C1_10710C_A, CR_09830W_A | 1.30e-04 |

| Trehalose metabolism in response to stress | HSP21, NTH1, HSP104, TPS2 | 2.10e-02 |

| Glyoxylate metabolic process | GOR1, ICL1, MLS1, C4_05390W_A | 5.17e-02 |

| Carbohydrate metabolic process |

GAL1, GAL10, TPS2, ICL1, PFK26, MLS1, PFK27, HSP21, GPD1, PYC2, XKS1, NTH1, GSY1, HSP104 |

6.25e-02 |

| Oxidation-reduction process |

GOR1, AOX2, ERO1, FMP52, MRF1, C2_07270W_A, IFM3, UCF1, GPD1, DAO2, SCS7, C4_05390W_A, OYE32, GPX1, OYE23, MIX17, NPD1, ALK2, GSY1, IFE2, CDG1 |

7.63e-02 |

| Down-regulated transcripts | ||

| Lipid biosynthetic process | CWH8, FEN1, LCB2, DGK1, AYR1, ERG6, LAC1, IDI1, PEL1, CYB5, EPT1, COQ1, ERG25, CHO2, NDT80 | 1.34e-03 |

| Regulation of protein serine/threonine kinase activity | RHO2, SOL1, WSC1, PBS2, CLN3, CIP1, CLG1 | 7.82e-03 |

| Filamentous growth | CHS7, RAC1, CAT1, VRG4, SSU81, UTP6, GIN4, NDT80, ESC4, RHO2, RAS1, ASH1, MNT2, CCC1, WSC1, LAC1, MNN9, PBS2, ISW2, CLN3, CHT2, TOP1, CUP9, YEL1, RSR1, SMC5, PGA1 | 5.07e-02 |

| Fungal-type cell wall organization or biogenesis |

XOG1, CHS7, RAC1, SSU81, FEN1, SIM1, SPF1, RHO2, MNT2, WSC1, CHS4, MNN9, PBS2, PGA1 |

5.99e-02 |

Albicans response to Niclosamide. Gene ontology analysis was performed using the Candida Genome Database GO Term Finder. aThe p-value was calculated using hypergeometric distribution, as described on the GO Term Finder website.

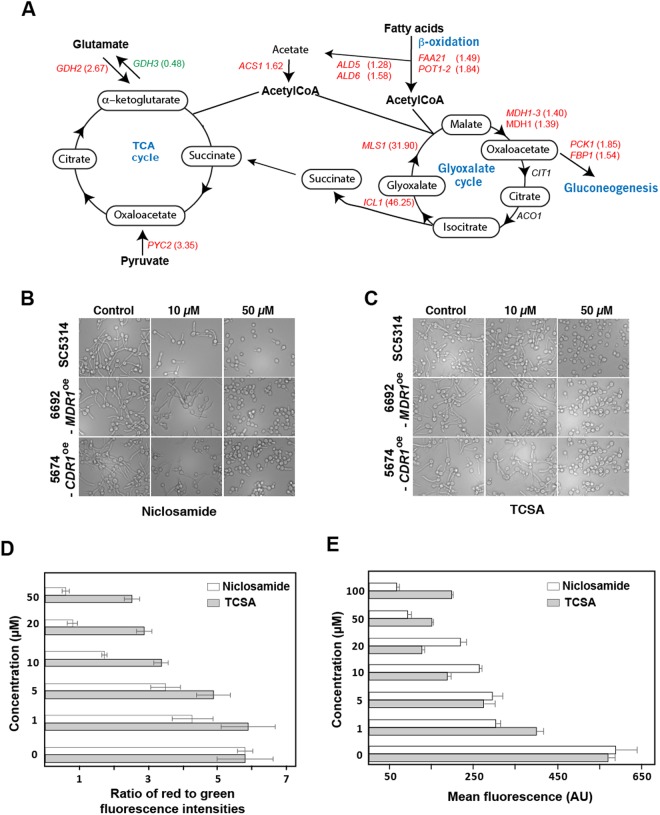

Of note, transcripts of the isocitrate lyase, ICL1, and the malate synthase, MLS1, both key enzymes of glyoxylate cycle were highly induced (46- and 13-fold induction for ICL1 and MLS1, respectively) (Fig. 5A and Table S2). The glyoxylate cycle is an anaplerotic pathway of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle that allows assimilation of carbon from C2 compounds by bypassing the CO2-generating steps of the TCA cycle. Both Icl1 and Mls1 enzymes are perxisomal, unique to the glyoxylate route and are not shared with the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle36,37. Activation of those genes in response to Niclosamide suggests a metabolic reconfiguration where acetyl-CoA is supplied by the glyoxylate cycle instead of the TCA cycle, which might be compromised (Fig. 5A). This transcriptional signature is characteristic of the retrograde (RTG) response, which is a mitochondria-to-nucleus signaling that cells activates as a cytoprotective mechanism to compensate for mitochondrial dysfunctions38. Another supportive evidence of the TCA cycle failure, is reflected by the activation of genes that mediate other anaplerotic reactions to supply the TCA cycle with intermediates from alternative pathways. This includes the cytoplasmic pyruvate carboxylase enzyme, Pyc2, that converts the pyruvate to oxaloacetate. Transcript level of the glutamate dehydrogenase, Gdh2, that degrades glutamate to ammonia and alpha-ketoglutarate, were also induced (2.67-fold change), however, the levels of induction were not consistent enough (p = 0.21) for it to pass the threshold of statistical significance.

Figure 5.

Niclosamide induces retrograde response in C. albicans. (A) Genome-wide transcriptional profiling reveals that transcript level of genes of anaplerotic reactions are altered in response to Niclosamide. Upregulated and downregulated genes are indicated by red and green, respectively. Transcripts that were not differentially expressed are shown in black. Simplified tricarboxylic and glyoxylate cycles as annotated in the CGD database are shown. (B,C) Antifilamentation effect of Niclosamide (B) and TCSA (C) on C. albicans resistant strains with different resistance mechanisms. C. albicans 6692 and 5674 resistant strains were grown under hyphae-promoting conditions (SC + 10% FBS) in the absence (control) or the presence of HSA (10–50 µM). (D,E) Niclosamide and TCSA alter the mitochondrial membrane potential. C. albicans SC5314 strain cells were treated with different concentrations (1–50 µM) of either TCSA or Niclosamide. Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) were measured using the fluorescent potentiometric dye JC-1 and flow cytometry (D). Alternatively, the effect of both HSA on ΔΨm was assessed by MitoTracker staining (E). For both of JC-1 and MitoTracker assays, fluorescence ratio and intensities (AU) were presented as the mean of at least three independent experiments.

Activated transcripts were also enriched in genes encoding many proteins with oxidoreductase activity which might reflect a compensatory response to reoxidize the NADH as a consequence of TCA and mitochondrial electron transport failures. Reactivation of glycolytic regulatory genes PFK26 and PFK27 suggests also an adaptation to the drop of the intracellular level of ATP as a result of mitochondrial dysfunction. The strong upregulation of the alternative oxidase transcript, Aox2 (31.5-fold induction), emphasizes that C. albicans cells might use this alternative electron transport systems to bypass the lack of mitochondrial electron transport. Taken together, the Niclosamide-transcriptional signature is reminiscent of cells experiencing an RTG response as a consequence of impaired mitochondrial activity.

Antifilamentation activity of Niclosamide and TCSA against C. albicans azole-resistant strains

In response to Niclosamide, C. albicans cells induced the expression of transporters such as Cdr1 and Mdr1 that are a key determinant of antifungal clinical resistance in this human pathogen39–41. This reflect that C. albicans is trying to expel Niclosamide through efflux process. This prompt us to check whether antifungal resistance mediated by efflux process might bypass the antifilamentation effect of HSA. Both Niclosamide and TCSA were tested on clinical strains for which azole resistance is mediated by MDR1 (strain 6692) and CDR1 (strain 5674) overexpression. As shown in Fig. 5B,C, the antifilamentation effect of the two salicylanilides on these two resistant isolates was similar to that noticed for the SC5314 sensitive clinical strain. This emphasizes that Niclosamide and TCSA could be used to compromise C. albicans filamentation of both azole-sensitive and resistant strains.

Niclosamide and TCSA alter the mitochondrial membrane potential

In the budding yeast, RTG response is triggered by the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) as a consequence of mitochondria dysfunction42. Thus, Niclosamide or TCSA might induce RTG in C. albicans by promoting the perturbation of the ΔΨm. Change in ΔΨm was quantitatively assessed using JC-1, a green fluorescent potentiometric dye that shifts to red fluorescence as a consequence of ΔΨm. C. albicans cells treated with either Niclosamide or TCSA exhibited a collapse of the ΔΨm which was obvious at the concentration of 5 µM (Fig. 5D). The effect of both HSA on the failure of ΔΨm was also confirmed using the MitoTracker dye that stains and accumulate in mitochondria dependently on ΔΨm43 (Fig. 5E). These data suggest that both HSA induce RTG response in C. albicans as consequence of the alteration of ΔΨm.

Mutants of the mitochondrial protein import machinery are required for Niclosamide tolerance and filamentation

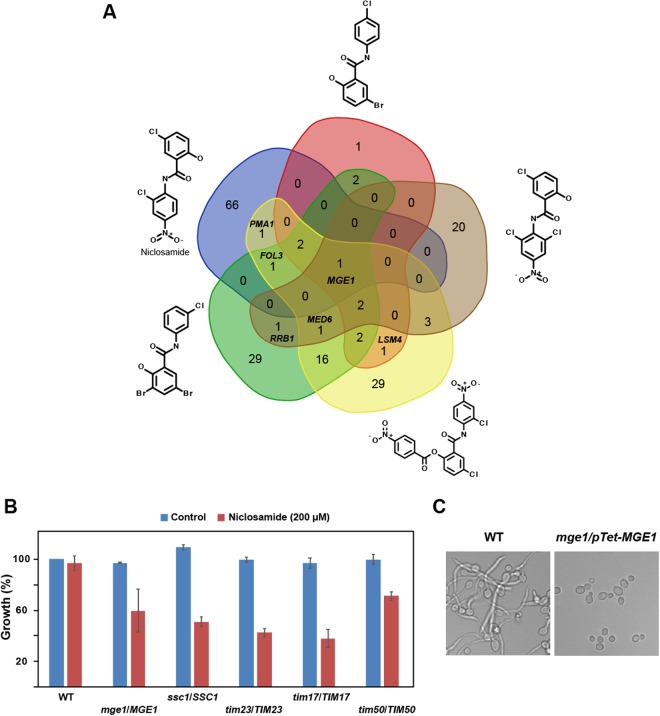

Chemical-genetic assays such as the haploinsufficient profiling (HIP) is a powerful tool that has been widely used to uncover the mechanism of action (MoA) of many bioactive compounds44–47. The principle of the HIP assay is based on the fact that decreased dosage of a drug target gene in a heterozygous mutant can result in increased drug sensitivity. To investigate the MoA of the HSA associated with their antifilamentation activity, we mined the data of HIP experiments performed in the yeast model S. cerevisiae in two resource studies48,49. Hoepfner et al.48 has performed HIP assay for Niclosamide while other analogs similar to HSA were investigated using the same approach by Corey Nislow’ group49. To gain a consensual knowledge into the MoA of HSA, common hits identified by HIP assay of these related compound were identified by Venn diagram that revealed mge1/MGE1 mutant as unique common hit for the five HSA (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Mitochondrial protein import machinery is required for Niclosamide tolerance and filamentation. (A) Mining HIP assay data of HSA from studies performed by Hoepfner et al.48 and Corey Nislow’ group49 (http://chemogenomics.pharmacy.ubc.ca/hiphop/) in S. cerevisiae. HSA-haploinsufficient mutant hits identified by HIP assay for each compound were selected based on z-score ≥ 2.5. The Venn diagram was generated using the web tool software at the following URL: www. bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn. (B) C. albicans heterozygous mutants of the TIM23 complex including tim23/TIM23, tim17/TIM17, tim50/TIM50, ssc1/SSC1 and mge1/MGE1 are sensitive to high concentration of Niclosamide (200 µM). (C) The conditional homozygous mutant mge1/pTeT-MGE1 under repressive conditions (100 µg/mL tetracycline) is unable to differentiate true hyphae when grown at 37 °C in Spider medium as compared to the parental strain CAI4.

Mge1 is a nucleotide release factor for the mitochondrial heat shock protein 70, Ssc1 that acts by facilitating the release of ADP from Ssc150. This process is essential for the import complex to translocate nuclear-encoded proteins to their final mitochondrial destination. Both Mge1 and Scc1 are components of the Tim23-Tim17 import motor complex that mediates the translocation of proteins through the inner mitochondrial membrane51. The sensitivity of C. albicans heterozygous mutants of TIM23 complex including tim23/TIM23, tim17/TIM17, tim50/TIM50, ssc1/SSC1 and mge1/MGE1 was tested toward high concentration of Niclosamide (200 µM). While the WT parental strain had no discernable growth defect, all tested mutants were sensitive when exposed to Niclosamide (Fig. 6B). The Niclosamide-induced haploinsufficiency of the TIM23 complex suggests that the C. albicans translocase machinery of the inner mitochondrial membrane is required to tolerate Niclosamide and/or might be a target of this HSA.

In opposite to S. cerevisiae, MGE1 is not essential in C. albicans52. As for the heterozygous mutant strain, the conditional homozygous mutant mge1/pTeT-MGE1 under repressive condition (100 µg/mL tetracycline) was also sensitive to Niclosamide (not shown). Furthermore, genetic inactivation of MGE1 led to a complete filamentation defect which support the hypothesis that this protein might be the target of HSA (Fig. 6C).

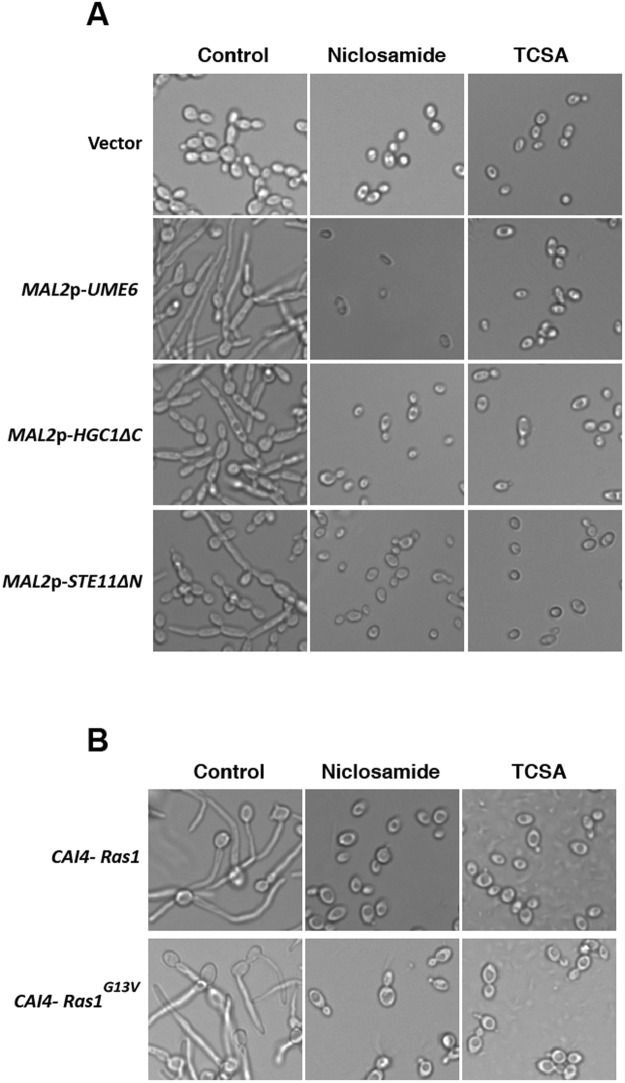

Chemical genetics of hyphal signaling using TCSA and Niclosamide as perturbers

The C. albicans morphogenetic switch is controlled by intertwined regulatory circuits that signal different filamentation cues. The RAS/cAMP53, the MAPK54 and Ume6/Hgc155 pathways are high hierarchical regulators and signaling hubs that control the filamentation process in C. albicans. To test whether Niclosamide and TCSA alter C. albicans filamentation through these pathways, the effect of the two molecules was assessed in mutants overexpressing UME6, HGC1 and the MAPKKK, STE11 in addition to the dominant mutant Ras1G13V. These mutants constitutively formed hyphae or pseudohyphae which will determine whether antifilamentation molecules act upstream or downstream these pathways. Niclosamide and TCSA blocked C. albicans filamentation regardless the targeted regulators suggesting that both compounds acted on effectors downstream these signaling pathways (Fig. 7A,B).

Figure 7.

Chemical genetics of the C. albicans hyphal signaling network using HSA as perturbers. (A) Effect of Niclosamide and TCSA on C. albicans mutants overexpressing key regulator of the yeast-to-hyphae transition. Ectopic filamentation of MAL2p-UME6, MAL2p-HGC1ΔC and MAL2p-STE11ΔN mutants was ensured by growing these strains under inducing conditions in YNB- 2% maltose medium at 30 °C for 3 hours. (B) Constitutive filamentation of the dominant Ras1G13V mutant is inhibited by Niclosamide and TCSA. Both Ras1G13V mutant and the control strain (CAI4-Ras1) were grown at 30 °C on Spider medium.

Discussion

Neutralizing the virulence traits of a fungal pathogen represents a promising therapeutic strategy to circumvent antifungal resistance. Regardless the degree of susceptibility or resistance of a fungal strain toward conventional antifungal drugs, antivirulence molecules lead to the silencing of the virulence machinery which in turn inhibits the installation of the infection. Furthermore, antivirulence agents could bypass the undesirable side effects of antimicrobials that kill beneficial commensal fungi including C. albicans itself14. In the current work, we have repurposed the widely used anthelminthic, Niclosamide and its derivative TCSA as a promising antivirulence compounds that impede both invasive filamentation and biofilm formation in both susceptible and resistant clinical C. albicans strains. Currently, the antivirulence paradigm was clinically exploited to manage bacterial virulence factors such as anthrax toxins and botulinum neurotoxin14. To our knowledge, and given the fact that the safety of Niclosamide is well established in humans56, this molecule could represent the first clinically approved antivirulence agent against a pathogenic fungus. Interestingly, this anthelmintic agent was also shown to be affective toward bacterial pathogens as an antivirulence molecules against Pseudomonas aeruginosa57 or as an antibiotic against multi-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus27. This newly discovered antibacterial and antifungal proprietes would reinforce and maintain the status of Niclosamide as being one of the essential medicines in the list the World Health Organization.

Here, we uncovered that halogenated salicylanilides represent new chemical scaffolds that impede specifically C. albicans virulence without affecting the commensal yeast growth. Future comprehensive structure-guided medicinal chemistry investigations are required to precisely point out the chemical group that lead to this discriminative antivirulence activity. Of note, the non-halogenated salicylanilide scaffold (compound #3) has a strong anti-growth activity against C. albicans and suggests that halogenation enhances the antivirulence activity. Halogen bonds are exploited in medicinal chemistry for their steric effect to accommodate a best fitting of a small molecule to occupy the binding site of its target58. Our data showed that chlorination was more effective as compared to fluorination (compound #5 and #8) or bromination (compound #11) regarding the antivirulence activity. This might be explained by the fact that, as compared to the other halogens-carbon bonds, C-Cl is more stable which might allow a steady docking on its virulence-related target58.

Regarding the mechanism of action, HSA have been associated with the perturbation of a plethora of biological processes in bacteria and parasites. Salicylanilides have been shown to inhibit the two-component regulatory systems, uptake of nutrients and oxidative phosphorylation, and to cause leakage and membrane damage and protein aggregation59. However, their mechanisms associated with their antifungal or antivirulence activity were not investigated so far. In the current study, the transcriptional signature exhibited by C. albicans cells exposed to Niclosamide suggests activation of different anaplerotic metabolic pathways that can sustain the TCA cycle with metabolites such as citrate, succinate and oxaloacetate. This phenomenon, so-called RTG, is most likely triggered in C. albicans cells as a consequence of the dissipation of the mitochondrial potential. The HIP assays on cells treated to different HSA uncovered that Mge1 might be a potential target of Niclosamide and TCSA. Indeed, genetic inactivation of Mge1 led to a complete filamentation defect which supports the hypothesis that this protein might be the target of HSA.

Mge1 is a nucleotide release factor that mediates the release of ADP from the heat shock protein Ssc150. This process is essential for the mitochondrial import complex to translocate nuclear-encoded proteins to mitochondria. Interestingly, this process is ΔΨm-depend which suggests that the collapse of ΔΨm mediated by HSA might contribute to the malfunctioning of the mitochondrial import complex and thus compromises protein translocation in the mitochondria60. Alternatively, in addition to its role as ADP-ATP recycling factor, Mge1 functions as a co-chaperone in the mitochondrial matrix together with Scc1 and Mdj1 to refold desaturated proteins61. Taken together, either protein translocation or refolding functions of Mge1 could be hampered by HSA which in turn lead to the filamentation defect in C. albicans.

To assess whether HSA perturb mitochondrial processes, their effect was also tested on a rho0 petite mutant of the budding yeast S. cerevisiae missing the mitochondrial DNA (not shown). We were not able to generate a C. albicans rho0 petite mutant since mitochondrial DNA is most likely essential for the viability of this opportunistic yeast as reported previously62. When exposed to high concentrations of HSA (>250 µM), the rho0 mutant was as sensitive as its congenic parental WT strain suggesting that mitochondrial functions that require mitochondrial DNA are dispensable to tolerate either Niclosamide or TCSA. This finding suggests also that HSA might have additional cellular target(s) other than the mitochondrial protein import machinery. Meanwhile, the rho0 data in S. cerevisiae could not be extrapolated in C. albicans since it is suggestive of other target(s) in the context of yeast growth inhibition but not filamentation inhibition.

While deep investigations are required to validate that Mge1 and/or the mitochondrial protein import complex as a target of HSA, previous elegant investigations in C. albicans have shown that many fungal mitochondrial proteins are therapeutic targets for antifungal development63. Furthermore, Mge1 has been recently shown to be a key regulator of azole susceptibility64 which make the fungal mitochondria as an attractive organelle target to develop anti-virulence, anti-growth and anti-resistance molecules to manage fungal infection.

Methods

Strains and growth conditions

The strains used in the current study are listed and described in Table 2. For general propagation, the strains were cultured at 30 °C in synthetic complete (SC; 0.67% yeast nitrogen base with ammonium sulfate, 2% glucose, and 0.079% complete supplement mixture) or yeast-peptone-dextrose (YPD; 2% Bacto-peptone, 1% yeast extract, 2% dextrose) media supplemented with uridine (50 mg/L).

Table 2.

Fungal strains used in this study.

| Name | Description/Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans | ||

| SC5314 (ATCC-MYA-2876) |

C. albicans wild-type reference strain. | 72 |

| 5674 | Azole-resistant clinical strain (overexpressing the ABC-transporters Cdr1 and Cdr2, and the phosphatidylinositol transfer protein, Pdr16) isolated from mouth | 73 |

| 6692 | Azole-resistant clinical strain (overexpressing the MFS-transporter Mdr1 and had a gain-of-function mutation on the transcription factor, Mrr1) isolated from mouth | 73, 74 |

| KC685 | ura3Δ/ura3Δ his1Δ/his1Δ leu2Δ/leu2Δ arg4Δ/arg4Δ pMAL2-URA3 | 17 |

| KC753 | KC685 STE11/pMAL2-STE11ΔN-URA3 | 17 |

| KC763 | KC685 UME6/pMAL2-UME6-URA3 | 17 |

| KC754 | KC685 HGC1/pMAL2-HGC1ΔC-URA3 | 17 |

| DH545 | ura3::λimm434/ura3 pYPB1-ADHpL-CaRAS1 | 75 |

| DH409 | ura3::λimm434/ura3 pYPB1-ADHpL-CaRAS1G13V | 75 |

| Candida auris | ||

| HDQ-RPCau1 | Clinical isolate from Hôtel-Dieu de Québec Hospital, QC, Canada | — |

Screen of the bioactive chemical yeast library

To identify small molecules with antifilamentation properties, the yeast bioactive small molecule library from Dr Mike Tyers (University of Montreal) consisting of 678 compounds preselected from the Maybridge collection (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was screened. C. albicans SC5314 strain cells were grown in 96-well in SC medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Wisent) and one microliter of each compound from the master library plate was dispensed into the assay plate at a final concentration of 100 µM. DMSO at 1% (v/v) final concentration was added as control to each assay plate. After an incubation for 3 h in the high-content microscope Cytation 5 (BioTek®, Thermo Fisher Scientific), images were taken in each well. Hit from this primary screen were confirmed using new batch of powders ordered separately. Frequent hitters and promiscuous compounds in antifungal discovery pipelines22 were removed from our hit list. Effect of antifilamentation compounds on the yeast growth of C. albicans were assessed as follow: SC5314 strain was grown overnight in YPD medium at 30 °C in a shaking incubator at 220 rpm. Cells were then resuspended in fresh SC at an OD600 of 0.05. A total volume of 99 μl fungal cells was added to each well of a flat-bottom 96-well plate in addition to 1 μl of the corresponding stock solution antifilamentation molecules. Plates were incubated in a Sunrise-Tecan plate reader at 30 °C with agitation and OD600 readings were taken every 10 min over 24 h. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Hyphal growth and biofilm assays

An overnight culture of the C. albicans strains was used to inoculate a 5 mL of fresh YPD at an OD600 of 0.05. Cells were grown for 4 h at 30 °C under agitation to reach the exponential phase. To induce hypha, the SC5314, 6692 and 5674 strains were grown at 37 °C in YPD supplemented with either 10% FBS (Wisent) or 2.5 mM N-acetyl-D- glucosamine (Sigma), or in Spider (1% mannitol, 1% nutrient broth, 0.2% K2HPO4), Lee’s65 or RPMI 1640 (Gibco) media. The filament length of the generated filaments was assessed for at least 100 C. albicans cells per sample, and all experiments were performed in triplicate. The effect of HSA on hyphae lengths were presented as box plot using the BoxPlotR web tool66.

Biofilm formation and XTT (2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfo- phenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide) assays were carried out as follow: overnight YPD cultures were washed three times with PBS and resuspended in fresh RPMI 1640 supplemented with L-glutamine (0.3 g/L) to an OD600 of 0.1. C. albicans yeast cells were allowed to attach to a flat-bottom 96-well polystyrene plate for 3 h at 37 °C in a rocking incubator. After removing non-attached cells by washing 3 time using PBS, fresh RPMI supplemented with HAS was added. The plates were then incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C for biofilm formation under agitation at 220 rpm. Each well in the plate was then washed 3 times with PBS and fresh RPMI supplemented with 100 μl of XTT-menadione mix (0.5 mg/ml XTT in PBS and 1 mM menadione in acetone) was added. After 3 hours of incubation on dark at 37 °C, 80 μl of the resulting colored supernatants were used for colorimetric reading at an OD490 to assess metabolic activity of biofilms. A minimum of four replicates were at least performed. Biofilm formation for C. auris was performed as for C. albicans with the sole exception that cells were allowed to attach for 6 hours.

Transcriptional profiling

Overnight cultures of C. albicans strain SC5314 were diluted to an OD600 of 0.1 in 100 mL of fresh YPD and grown at 30 °C until an OD600 of 0.65. The culture was divided into two volumes of 50 mL where 10% FBS serum was added to induce hyphae formation; one sample was maintained as the control where DMSO was added, and the other treated with Niclosamide at 50 µM. Candida cells were then incubated at 37 °C and under agitation at 220 rpm for 15 min. Cells were then centrifuged for 2 min at 3,500 rpm, the supernatants were removed, and the samples were quick-frozen and stored at 80 °C.

RNA extractions, cDNA labelling and microarrays procedures were performed as described by Chaillot et al.67. Data analysis were carried out using Genespring v.7.3 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Statistical analysis used Welch’s t-test with a false-discovery rate (FDR) of 5% and 2-fold enrichment cut-off. Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed using the Candida Genome Database (CGD) GO Term Finder. The p-value was calculated using hypergeometric distribution with multiple hypothesis correction (http://www.candidagenome.org/cgi-bin/GO/goTermFinder)68. Descriptions of each C. albicans gene in Table S2 were extracted from CGD database69.

For quantitative real time PCR (qPCR) confirmation, cell cultures and RNA extractions were performed as described for the microarray experiment. cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). The mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 10 min, 37 °C for 120 min and 85 °C for 5 min. Then RNAse H (NEB) was added to remove RNA. qPCR was performed using LightCycler 480 Instrument (Roche Life Science) with SYBR Green fluorescence (Applied Biosystems). The reactions were incubated at 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 2 min and cycled 40 times at 95 °C, 15 s; 54 °C, 30 s; 72 °C, 1 min. Fold-enrichment of each tested transcripts was estimated using the comparative ΔΔCt method as described by Guillemette et al.70. To evaluate the gene expression level, the results were normalized using Ct values obtained from Actin (ACT1, C1_13700W_A). Primer sequences used for this analysis are summarized in Supplemental Table S3.

HT-29 damage assay

Damage to the human enterocyte HT-29 (ATCC-HTB-38) was assessed using a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity detection kit, which measures the release of LDH in the growth medium as described by Garcia et al.71. Briefly, enterocytes were plated at 10.000 cells per 96-well in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The HT-29 cells were then infected with C. albicans SC5314 strain cells with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1:20 (Enterocyte:C. albicans). Following 24 hours of incubation, 100 µL supernatant was removed from each experimental well and LDH activity in this supernatant was determined by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm. Each LDH activity assay was performed in triplicate and at least three independent biological replicates were performed.

Chemical epistasis assay

Inhibition assay of ectopically hyphae-grown strains KC753 (MAL2-STE11ΔN), KC763 (MAL2-UME6) and KC754 (MAL2- HGC1ΔC) as well as their control strain KC685 was performed as follow: cells were grown overnight in SC medium where glucose was replaced by 2% raffinose. Overexpression of UME6, STE11 and HGC1 was ensured by diluting the overnight cultures in fresh SC medium where glucose was replaced by 2% maltose in the presence or not of HSA. The cells were incubated for 5 h at 30 °C. The DH409 mutant with a hyperactive Ras1 (Ras1G13V) allele and the control strain DH545 were allowed to filament in Spider medium at 30 °C in the presence of HSA for 2 h.

Measurements of mitochondrial membrane potential

The mitochondrial membrane potential of C. albicans cells was measured using both fluorescent probes, JC-1 and MitoTracker Red CMXRos (ThermoFisher). Exponentially grown C. albicans cells were washed twice with PBS and treated or not with different concentrations of either Niclosamide or TCSA for 30 min under hyphae promoting conditions. JC1 and MitoTracker were added to C. albicans cells at final concentration of 5 µM and 100 nM, respectively, and cells were incubated at 30 °C for 30 min in dark. Cells were then washed twice with PBS to remove residual dyes. Fore JC-1, fluorescence was quantitatively assessed using flow cytometry (BD FACSCanto™) using 106 C. albicans cells. For the MitoTracker assay, the fluorescence was measured using the Cytation 5 plate reader (BioTek®). Results of JC-1 and MitoTracker assays were measured as the mean of fluorescence intensities of at least three independent experiments.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mike Tyers and Susan Moore (Université de Montreal) for providing the yeast bioactive small molecule library. We thank Martine Raymond (Université de Montreal) for providing C. albicans clinical strains, René Pelletier (Research Center of the CHU de Québec) for the C. auris strain, Deborah Hogan (Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth) for sharing the Ras1G13V mutant and Daniel Kornitzer (Technion) for the hypofilamentous C. albicans strains. Work in Sellam’s laboratory is supported by the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQS) (Établissement de jeunes chercheurs), the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI- # 34171), the Fondation de l’Université Laval-Merck fund and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) discovery grant (06625). AS is a recipient of the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQS) J1 salary award. AB and JC received Ph.D. scholarships from Université Laval (Faculty of Medicine) and the CHUQ foundation.

Author Contributions

A.S. designed the experiments. C.G., A.B., J.C., E.P., I.K. and A.S. performed the experiments and interpreted the data. C.G. and A.S. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-29973-8.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2007;20:133–163. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gudlaugsson O, et al. Attributable mortality of nosocomial candidemia, revisited. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2003;37:1172–1177. doi: 10.1086/378745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pappas PG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2009;48:503–535. doi: 10.1086/596757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro RS, Robbins N, Cowen LE. Regulatory circuitry governing fungal development, drug resistance, and disease. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR. 2011;75:213–267. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00045-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perfect JR. The antifungal pipeline: a reality check. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:603–616. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wurtele H, et al. Modulation of histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation as an antifungal therapeutic strategy. Nat Med. 2010;16:774–780. doi: 10.1038/nm.2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raj S, et al. The Toxicity of a Novel Antifungal Compound Is Modulated by Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Protein Degradation Components. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;60:1438–1449. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02239-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alksne LE, Projan SJ. Bacterial virulence as a target for antimicrobial chemotherapy. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2000;11:625–636. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gauwerky K, Borelli C, Korting HC. Targeting virulence: a new paradigm for antifungals. Drug discovery today. 2009;14:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim K, Zilbermintz L, Martchenko M. Repurposing FDA approved drugs against the human fungal pathogen, Candida albicans. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2015;14:32. doi: 10.1186/s12941-015-0090-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rizzetto L, Cavalieri D. Friend or foe: using systems biology to elucidate interactions between fungi and their hosts. Trends in microbiology. 2011;19:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobsen ID, et al. Candida albicans dimorphism as a therapeutic target. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012;10:85–93. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paramonova E, Krom BP, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ, Sharma PK. Hyphal content determines the compression strength of Candida albicans biofilms. Microbiology. 2009;155:1997–2003. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.021568-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickey SW, Cheung GYC, Otto M. Different drugs for bad bugs: antivirulence strategies in the age of antibiotic resistance. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:457–471. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toenjes KA, et al. Small-molecule inhibitors of the budded-to-hyphal-form transition in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:963–972. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.3.963-972.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fazly A, et al. Chemical screening identifies filastatin, a small molecule inhibitor of Candida albicans adhesion, morphogenesis, and pathogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:13594–13599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305982110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bar-Yosef H, Vivanco Gonzalez N, Ben-Aroya S, Kron SJ, Kornitzer D. Chemical inhibitors of Candida albicans hyphal morphogenesis target endocytosis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5692. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05741-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goffena, J., Toenjes, K. A. & Butler, D. K. Inhibition of Yeast-to-Filamentous Growth Transitions in Candida albicans by a Small Molecule Inducer of Mammalian Apoptosis. Yeast, 10.1002/yea.3287 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Romo, J. A. et al. Development of Anti-Virulence Approaches for Candidiasis via a Novel Series of Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Candida albicans Filamentation. MBio8, 10.1128/mBio.01991-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Vila, T. & Lopez-Ribot, J. L. Screening the Pathogen Box for Identification of Candida albicans Biofilm Inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother61, 10.1128/AAC.02006-16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Ishizaki H, et al. Combined zebrafish-yeast chemical-genetic screens reveal gene-copper-nutrition interactions that modulate melanocyte pigmentation. Disease models & mechanisms. 2010;3:639–651. doi: 10.1242/dmm.005769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pouliot M, Jeanmart S. Pan Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) and Other Promiscuous Compounds in Antifungal Research. J Med Chem. 2016;59:497–503. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swan GE. The pharmacology of halogenated salicylanilides and their anthelmintic use in animals. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1999;70:61–70. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v70i2.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frayha GJ, Smyth JD, Gobert JG, Savel J. The mechanisms of action of antiprotozoal and anthelmintic drugs in man. Gen Pharmacol. 1997;28:273–299. doi: 10.1016/S0306-3623(96)00149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tao H, Zhang Y, Zeng X, Shulman GI, Jin S. Niclosamide ethanolamine-induced mild mitochondrial uncoupling improves diabetic symptoms in mice. Nat Med. 2014;20:1263–1269. doi: 10.1038/nm.3699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye T, et al. The anthelmintic drug niclosamide induces apoptosis, impairs metastasis and reduces immunosuppressive cells in breast cancer model. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajamuthiah R, et al. Repurposing salicylanilide anthelmintic drugs to combat drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossello A, et al. Synthesis, antifungal activity, and molecular modeling studies of new inverted oxime ethers of oxiconazole. J Med Chem. 2002;45:4903–4912. doi: 10.1021/jm020980t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gundogdu-Karaburun N, Benkli K, Tunali Y, Ucucu U, Demirayak S. Synthesis and antifungal activities of some aryl [3-(imidazol-1-yl/triazol-1-ylmethyl) benzofuran-2-yl] ketoximes. Eur J Med Chem. 2006;41:651–656. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benkli K, et al. Synthesis and antifungal activities of some aryl (3-methyl-benzofuran-2-yl) ketoximes. Arch Pharm Res. 2003;26:202–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02976830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koca M, et al. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of some novel derivatives of benzofuran: part 1. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of (benzofuran-2-yl)(3-phenyl-3-methylcyclobutyl) ketoxime derivatives. Eur J Med Chem. 2005;40:1351–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Demirayak S, et al. Synthesis and antifungal activities of some aryl(benzofuran-2-yl)ketoximes. Farmaco. 2002;57:609–612. doi: 10.1016/S0014-827X(02)01257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nevagi RJ, Dighe SN, Dighe SN. Biological and medicinal significance of benzofuran. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;97:561–581. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.10.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Telvekar VN, Kundaikar HS, Patel KN, Chaudhari HK. 3-D QSAR and Molecular Docking Studies on Aryl Benzofuran-2-yl Ketoxime Derivatives as Candida albicans N-myristoyl transferase Inhibitors. QSAR & Combinatorial Science. 2008;27:1193–1203. doi: 10.1002/qsar.200810017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawasaki K, et al. Design and synthesis of novel benzofurans as a new class of antifungal agents targeting fungal N-myristoyltransferase. Part 3. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:87–91. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(02)00844-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piekarska K, et al. The activity of the glyoxylate cycle in peroxisomes of Candida albicans depends on a functional beta-oxidation pathway: evidence for reduced metabolite transport across the peroxisomal membrane. Microbiology. 2008;154:3061–3072. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/020289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunn MF, Ramirez-Trujillo JA, Hernandez-Lucas I. Major roles of isocitrate lyase and malate synthase in bacterial and fungal pathogenesis. Microbiology. 2009;155:3166–3175. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.030858-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jazwinski SM. The retrograde response: a conserved compensatory reaction to damage from within and from without. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2014;127:133–154. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394625-6.00005-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsao S, Rahkhoodaee F, Raymond M. Relative contributions of the Candida albicans ABC transporters Cdr1p and Cdr2p to clinical azole resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1344–1352. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00926-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmes AR, et al. ABC transporter Cdr1p contributes more than Cdr2p does to fluconazole efflux in fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3851–3862. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00463-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White TC. Increased mRNA levels of ERG16, CDR, and MDR1 correlate with increases in azole resistance in Candida albicans isolates from a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1482–1487. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jazwinski SM, Kriete A. The yeast retrograde response as a model of intracellular signaling of mitochondrial dysfunction. Front Physiol. 2012;3:139. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pendergrass W, Wolf N, Poot M. Efficacy of MitoTracker Green and CMXrosamine to measure changes in mitochondrial membrane potentials in living cells and tissues. Cytometry A. 2004;61:162–169. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baetz K, et al. Yeast genome-wide drug-induced haploinsufficiency screen to determine drug mode of action. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:4525–4530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307122101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giaever G, et al. Chemogenomic profiling: identifying the functional interactions of small molecules in yeast. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:793–798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307490100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lum PY, et al. Discovering modes of action for therapeutic compounds using a genome-wide screen of yeast heterozygotes. Cell. 2004;116:121–137. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu D, et al. Genome-wide fitness test and mechanism-of-action studies of inhibitory compounds in Candida albicans. PLoS pathogens. 2007;3:e92. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoepfner D, et al. High-resolution chemical dissection of a model eukaryote reveals targets, pathways and gene functions. Microbiol Res. 2014;169:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee AY, et al. Mapping the cellular response to small molecules using chemogenomic fitness signatures. Science. 2014;344:208–211. doi: 10.1126/science.1250217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Q, D’Silva P, Walter W, Marszalek J, Craig EA. Regulated cycling of mitochondrial Hsp70 at the protein import channel. Science. 2003;300:139–141. doi: 10.1126/science.1083379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Demishtein-Zohary K, Azem A. The TIM23 mitochondrial protein import complex: function and dysfunction. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;367:33–41. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Meara TR, et al. Global analysis of fungal morphology exposes mechanisms of host cell escape. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6741. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feng Q, Summers E, Guo B, Fink G. Ras signaling is required for serum-induced hyphal differentiation in Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6339–6346. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6339-6346.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Csank C, et al. Roles of the Candida albicans mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog, Cek1p, in hyphal development and systemic candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2713–2721. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2713-2721.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y. Hgc1-Cdc28-how much does a single protein kinase do in the regulation of hyphal development in Candida albicans? J Microbiol. 2016;54:170–177. doi: 10.1007/s12275-016-5550-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andrews P, Thyssen J, Lorke D. The biology and toxicology of molluscicides, Bayluscide. Pharmacol Ther. 1982;19:245–295. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(82)90064-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Imperi F, et al. New life for an old drug: the anthelmintic drug niclosamide inhibits Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:996–1005. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01952-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hernandes MZ, Cavalcanti SM, Moreira DR. de Azevedo Junior, W. F. & Leite, A. C. Halogen atoms in the modern medicinal chemistry: hints for the drug design. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:303–314. doi: 10.2174/138945010790711996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kratky M, Vinsova J. Salicylanilide ester prodrugs as potential antimicrobial agents–a review. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:3494–3505. doi: 10.2174/138161211798194521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dudek J, Rehling P, van der Laan M. Mitochondrial protein import: common principles and physiological networks. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:274–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kubo Y, et al. Two distinct mechanisms operate in the reactivation of heat-denatured proteins by the mitochondrial Hsp70/Mdj1p/Yge1p chaperone system. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:447–464. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shingu-Vazquez M, Traven A. Mitochondria and fungal pathogenesis: drug tolerance, virulence, and potential for antifungal therapy. Eukaryot Cell. 2011;10:1376–1383. doi: 10.1128/EC.05184-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li D, Calderone R. Exploiting mitochondria as targets for the development of new antifungals. Virulence. 2017;8:159–168. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1188235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Demuyser, L. et al. Mitochondrial Cochaperone Mge1 Is Involved in Regulating Susceptibility to Fluconazole in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida Species. MBio8, 10.1128/mBio.00201-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Lee KL, Buckley HR, Campbell CC. An amino acid liquid synthetic medium for the development of mycelial and yeast forms of Candida Albicans. Sabouraudia. 1975;13:148–153. doi: 10.1080/00362177585190271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spitzer M, Wildenhain J, Rappsilber J, Tyers M. BoxPlotR: a web tool for generation of box plots. Nat Methods. 2014;11:121–122. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chaillot J, et al. The Monoterpene Carvacrol Generates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in the Pathogenic Fungus Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:4584–4592. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00551-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Inglis DO, et al. The Candida genome database incorporates multiple Candida species: multispecies search and analysis tools with curated gene and protein information for Candida albicans and Candida glabrata. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D667–674. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Skrzypek MS, et al. The Candida Genome Database (CGD): incorporation of Assembly 22, systematic identifiers and visualization of high throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D592–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guillemette T, Sellam A, Simoneau P. Analysis of a nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene from Alternaria brassicae and flanking genomic sequences. Curr Genet. 2004;45:214–224. doi: 10.1007/s00294-003-0479-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Garcia, C. et al. The Human Gut Microbial Metabolome Modulates Fungal Growth via the TOR Signaling Pathway. mSphere2, 10.1128/mSphere.00555-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Fonzi WA, Irwin MY. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics. 1993;134:717–728. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saidane S, Weber S, De Deken X, St-Germain G, Raymond M. PDR16-mediated azole resistance in Candida albicans. Molecular microbiology. 2006;60:1546–1562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dunkel N, Blass J, Rogers PD, Morschhauser J. Mutations in the multi-drug resistance regulator MRR1, followed by loss of heterozygosity, are the main cause of MDR1 overexpression in fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains. Molecular microbiology. 2008;69:827–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Davis-Hanna A, Piispanen AE, Stateva LI, Hogan DA. Farnesol and dodecanol effects on the Candida albicans Ras1-cAMP signalling pathway and the regulation of morphogenesis. Molecular microbiology. 2008;67:47–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06013.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.