Abstract

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a bioactive sphingolipid mediator, has been implicated in regulation of many processes important for breast cancer progression. Previously we observed that S1P is exported out of human breast cancer cells by ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter ABCC1, but not by ABCB1, both known multidrug resistance proteins that efflux chemotherapeutic agents. However, the pathological consequences of these events to breast cancer progression and metastasis has not been elucidated. Here, it is demonstrated that high expression of ABCC1, but not ABCB1, is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients. Overexpression of ABCC1, but not ABCB1, in human MCF7 and murine 4T1 breast cancer cells enhanced S1P secretion, proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells. Implantation of breast cancer cells overexpressing ABCC1, but not ABCB1, into the mammary fat pad markedly enhanced tumor growth, angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis with a concomitant increase in lymph node and lung metastases as well as shorter survival of mice. Interestingly, S1P exported via ABCC1 from breast cancer cells upregulated transcription of sphingosine kinase 1 (SPHK1) thus, promoting more S1P formation. Finally, patients with breast cancers that express both activated SPHK1 and ABCC1 have significantly shorter disease-free survival. These findings suggest that export of S1P via ABCC1 functions in a malicious feed-forward manner to amplify the S1P axis involved in breast cancer progression and metastasis, which has important implications for prognosis of breast cancer patients and for potential therapeutic targets.

Keywords: ATP-binding cassette transporter C1, sphingosine-1-phospate, sphingosine kinase 1, breast cancer, prognosis

Introduction

Despite the recent improvement of 5-year survival due to advances in chemotherapy and targeted therapy, close to 40,000 women in the US continue to succumb to breast cancer every year (1). ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are transmembrane proteins that transport various molecules across cellular membranes including chemotherapeutic agents, functioning as a xenobiotic protective mechanism (2). Some of the ABC transporters, such as ABCB1 (multidrug resistance protein 1: MDR1) and ABCC1 (multidrug resistance associated protein1: MRP1), were originally identified as “multi-drug resistant genes and proteins”. Indeed, ABCB1 was demonstrated to export doxorubicin, one of the most frequently used chemotherapeutics for breast cancer that led to development of ABCB1 inhibitors to fight drug resistance (3,4). Disappointingly, all 12 clinical trials that examined ABCB1 targeted therapy failed to improve survival (5). This suggested to us that other ABC transporters may also drive drug resistance not only because they export drugs, but because they export molecules that biologically aggravate cancer progression, and that targeting these transporters may not be sufficient to improve survival.

The bioactive sphingolipid mediator sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is a key regulatory molecule in cancer that promotes cell proliferation, migration, invasion, angiogenesis, and lymphangiogenesis (6-8). S1P is generated intracellularly by two sphingosine kinases, SphK1 and SphK2, and is exported out of the cells where it regulates many functions by binding to and signaling through a family of five G protein-coupled receptors (S1PR1–5) in an autocrine, paracrine and/or endocrine manner, which is known as “inside-out” signaling (9). We previously demonstrated that SphK1, but not SphK2, produces S1P that is exported from MCF7 breast cancer cells stimulated by estradiol (10). We also demonstrated that expression of SphK1 is upregulated in human breast cancers (11) and the level of activated, phosphorylated SphK1 correlates with lymphatic metastasis (12), in agreement with reports by others (13,14).

It has previously been proposed that ABC transporters such as ABCC1 may function not only as an export mechanism for drugs but also exacerbate cancer progression. However, no candidates for this potential mechanism have yet been uncovered (3,15). High expression of ABCC1 has also been associated with poor prognosis in several types of human cancers, including breast cancer (5). Based upon our finding that ABCC1 exports S1P (10), it was tempting to suggest that S1P export via ABCC1 contributes to aggressive breast cancers with poor prognosis. Here we show that export of S1P via ABCC1 functions in a feed-forward manner to amplify the S1P axis involved in breast cancer progression and contributes to shortened survival of mice and humans with breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

MCF7 human mammary adenocarcinoma cells was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA), a murine mammary adenocarcinoma cell line that overexpresses luciferase 4T1-luc2 was obtained from Perkin Elmer (Waltham., MA). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and human lymphatic endothelial cells (HLEC) were obtained from Angio-Proteomie (Boston, MA) Cells were purchased in 2010-2012. After purchase, cell lines were expanded and frozen after one to three passages. Cells were expanded and stored according to the producer’s instructions. MCF7 and 4T1-luc2 cells were used for no longer than 10 passages, while HUVEC and HLEC cells were used for no longer than 3passages. All cell cultures were routinely tested to rule out mycoplasma infection using Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Abm, BC, CA). MCF7 was cultured in modified-IMEM without phenol red supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.22% dextrose, and 2 mM glutamine. 4T1-luc2 was cultured in RPMI Medium 1640 with 10% FBS. HUVEC and HLEC were maintained in endothelial cell medium supplemented with 5% FBS and endothelial cell growth supplement (ScienCell Research Laboratories).

Full length Homo sapiens ABCB1 (NM_000927.4) and ABCC1 (NM_004996.3) were subcloned into pcDNA3.1 in frame with a C-terminal V5-His tag (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using PCR with the following primers: ABCB1-forward 5′-TAA TAT GGA TCC ATG GAT CTT GAA GGG GAC CG-3′; ABCB1-reverse 5′-TAA TAT GGA TCC ATG GAT CTT GAA GGG GAC CG-3′; ABCC1-forward 5′-TAA TAT TCT AGA TTC TGG CGC TTT GTT CCA GC-3′; ABCC1-reverse 5′-TAA TAA TCT AGA TTC ACC AAG CCG GCG TCT TTG G-3′. Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Lipofectamine Plus reagents (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used to transfect MCF7 and 4T1-luc cells and Geneticin (G418) at 0.8 g/L or 0.1 g/L, respectively, was used to select stably transfected clones.

In vitro assays

Cell proliferation was determined with a WST-8 kit (Dojindo, Japan). Motility was determined by wound healing assays (16). In vitro angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis were determined by tube formation assays as previously described (17,18). QPCR, and western blotting were carried out essentially as described previously (10). Lipids were extracted and sphingolipids quantified by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS) (10,19). Cells were fixed for 5 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline and blocked by horse serum, and immunocytochemistry was performed using the following primary antibodies: anti-ABCB1 (C219, Abcam, UK), anti-ABCC1 (MRPr1, Monosan, The Netherlands), and anti-SphK1 phospho-Ser225 (ECM Biosciences). The specificities of anti-ABCC1 and anti-SphK1 antibodies and anti-phospho-SphK1 specific antibody, phospho-Ser225, were previously confirmed using siRNA knockdown (10,20). After incubation with biotinylated secondary antibodies, antigens were visualized with 3,30-diaminobenzidine (Dako, Denmark) and cells counterstained with hematoxylin.

Animal studies

All procedures were approved by the VCU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) that is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). For mice xenograft experiments, 10-18 week-old female BALB/c nu/nu mice (Harlan Laboratories, Frederick, MD) were ovariectomized via the dorsal approach and 0.72 mg 17-β-estradiol pellets (Innovative research) were implanted subcutaneously as described (21). MCF7 cells stably expressing ABCB1 (B1), ABCC1 (C1), or vector (V) were orthotopically implanted into the right upper mammary fat pads of nude mice as previously described (18,22,23). For syngeneic mice experiments, 4T1-luc2 cells stably expressing ABCB1, ABCC1, or vector were implanted in the same manner in 8-12 week old female BALB/c mice (Harlan Laboratories). Tumor volumes in mm3 were determined by measurements of length and width using calipers every 2-3 days. Bioluminescence was used to determine total tumor burden as well as metastases in ex vivo in axillary lymph nodes and lungs and was measured and quantified utilizing Xenogen IVIS 200 and Living Image software (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA) (24,25). Tumor interstitial fluid was collected as previously described (26).

For fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), tumors were minced and digested, and cell suspensions processed (18). Alexa 488–conjugated LYVE-1 (eBioscience); PE-conjugated podoplanin, PerCP-Cy5.5–conjugated CD45, APC-conjugated CD31, Alexa 700–conjugated TER-119 (Biolegend), or appropriate matched fluorochrome-labeled isotype control monoclonal antibodies were used for staining. Cells were analyzed by FACS using BD FACSCanto II and BD FACSAria II (BD Biosciences) and data assessed with BD FACSDiva Software version 6.1.3 (BD Biosciences). The remaining tumor sections were fixed with 10% of neutral buffered formalin for histopathological analysis.

Patient samples

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yokohama City University, and the patients provided informed consents before inclusion in the study. The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice guidelines. Tissues were obtained from 275 patients with stage 1 to 3 breast cancers treated in Yokohama City University Medical Center, Japan, between 2006 and 2008. The clinical characteristics are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Tissue micro-arrays were constructed as described (27). Because SphK1 is activated by phosphorylation in breast cancer cells, we examined the activation status of SphK1 in breast cancer patients by immunostaining of a tissue microarray from breast cancer patients with a phospho- SphK1 specific antibody. Specificity of the anti-phosphorylated SphK1 antibody was confirmed by immunocytochemistry of MCF7 human breast cancer cells. In agreement with previous studies (10,28), pSphK1 staining was increased after stimulation of MCF7 cells with estradiol and was absent when SphK1 was downregulated by a specific siRNA (data not shown).

Histopathologic analyses of mouse and human tumor samples

Five µm sections of mouse and human tumors were stained with anti-Ki-67 (DAKO), anti-SphK1 (Abcam), anti-SphK1 phospho-Ser225 (ECM Biosciences), anti–CD31 (BD), anti-LYVE-1 (Abcam), or anti-CK8 (Abcam). Sections were examined with a BX-41 light microscope (Olympus) or TCS-SP2 AOBS Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (Leica) and microvessel density was determined as previously described (29). ABCB1 and ABCC1 staining in the breast tumors was assessed according to the intensity and population of staining. We scored each sample by 0 to 3: 0 = negative, there is no staining in the tumor cells; 1 = weak, more than 10 % of tumor cells stained with weak intensity; 2 = moderate, more than 30% of tumor cells stained with intermediate intensity or less than 30% of tumor cells stained with strong intensity; 3 = strong, more than 30% of tumor cells stained with strong intensity. Negative: 0 and weak: 1 are considered as low expression, while moderate: 2 and strong: 3 are considered as high expression as previously described (27).

Interstitial fluid collection and quantification of sphingolipids by mass spectrometry

Cells, culture medium, and interstitial fluid from breast tumors was collected as described previously (26). Lipids were extracted from these samples, and sphingolipids were quantified by liquid chromatography, electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS, 4000 QTRAP, AB Sciex) as described (26).

METABRIC data acquisition and pre-processing and survival analysis

Level 3 Z-score normalized gene expression data was downloaded from the METABRIC breast cancer study using CBioPortal. All of 2509 patients with both overall survival data and U133 microarray data from Curtis et al. and Pereira et al. studies were considered (30,31). For single gene survival analyses based on expression of SphK1, patients were classified as having high or low expression of the given gene using a gene-specific z-score threshold. Patients were labeled as “high” if the expression of the interrogated gene was above the threshold and “low” if below the threshold. To determine the SphK1-specific threshold, Z-scores of 0, ±0.5, ±1, and ±2 were investigated. For each cutoff a survival curve was generated. The cutoff that generated the lowest log-rank p value, was chosen as the SphK1 cutoff. For dual ABCC1 or ABCB1 transporter and SphK1 survival analyses, an inclusive Z-score threshold of above and below 0 for each gene was used to maximize the size of the study sample. Two patient groups were classified by their patterns of expression of the pair of genes. For all analyses, Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed using GraphPad prism software. Statistical analysis was performed using the Mantel-Cox Log-Rank test and considered significant at the alpha = 0.05 significance level.

Statistical analysis

In vitro and in vivo experiments were repeated at least three times and consistent results are presented. Results were analyzed for statistical significance with the Student’s t test for unpaired samples. Correlations among the clinicopathologic parameters and each transporter or activated SphK1 were evaluated by the Pearson v2 test, the Fisher exact test, and the Mann–Whitney test. Patient outcomes were assessed by disease-free survival and distributions were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method using SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) Differences were compared using the log-rank test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

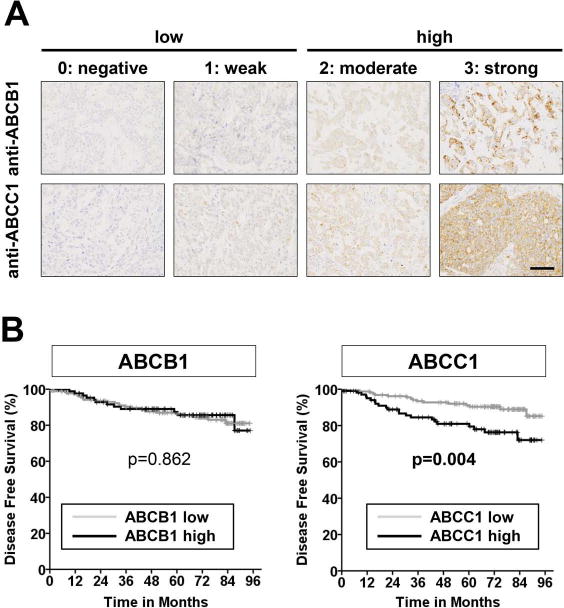

High expression of ABCC1, but not ABCB1, is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients

To further solidify the association of ABC transporter expression with breast cancer patient prognosis, we extended our previous study, which had a limited number of patients and a short duration (27), utilizing a tumor tissue microarray from a larger cohort of patients, and we analyzed expression of ABC transporters by immunohistochemistry. Patient and tumor characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Table S2. ABCB1 was highly expressed in 32.4% (89/275) while ABCC1 was highly expressed in 38.9% (107/275) of the tumors analyzed. Representative images of ABCB1 and ABCC1 stained tissues are shown in Fig. 1A. Patients with high ABCC1 expression had significantly shorter disease-free survival compared to patients with low ABCC1 expressing tumors with the follow up period up to 8 years (P = 0.004; Fig. 1B). In contrast, expression levels of ABCB1 were not associated with disease-free survival despite the extended number of patients and follow up period (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Expression of ABCC1 but not ABCB1 correlates with poor prognosis in human breast cancer patients.

Tissue microarrays containing 275 breast tumor tissues were stained with anti-ABCB1 or anti-ABCC1 antibodies. (A) Expression of ABCB1 and ABCC1 was scored as 0: negative, 1: weak, 2: moderate, or 3: strong. Score 0 and 1 are considered as low expression while score 2 and 3 are considered as high expression. Representative images are shown under high magnification for ABCB1 staining (upper), ABCC1 staining (lower). (B) Kaplan-Meier disease-free survival curves according to expression of ABCB1 and ABCC1. P values were calculated by the log-rank test. Scale bars, 50 μm.

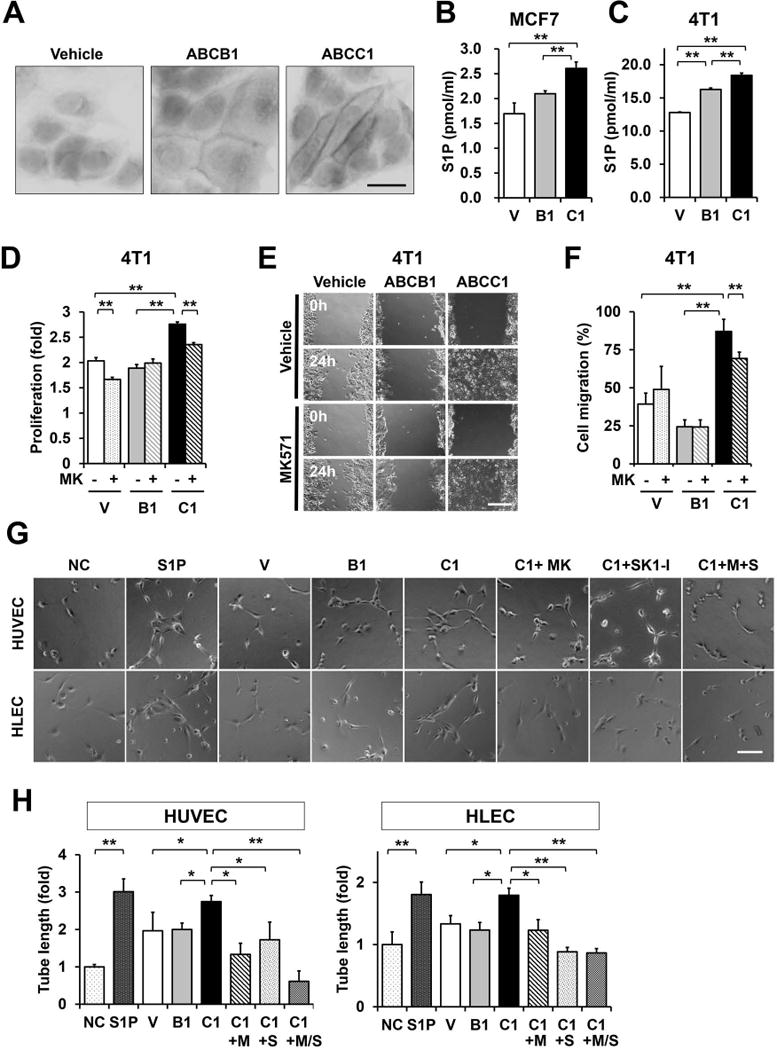

Overexpression of ABCC1, but not ABCB1, enhances S1P secretion, proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells and promotes angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in vitro

To investigate the role of ABC transporters in cancer progression, we generated MCF7 human breast cancer cells and 4T1-luc2 murine breast cancer cells stably overexpressing vector, ABCB1, and ABCC1. Expression of ABCB1 and ABCC1 was confirmed at the mRNA and protein levels by QPCR and western blotting, respectively, and immunohistochemistry confirmed that these ABC transporters are expressed on the plasma membrane (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 2. Overexpression of ABCC1 but not ABCB1, enhances proliferation and cell migration of breast cancer cells and promotes S1P secretion mediated angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis of endothelial cells. (A-E) MCF7 or 4T1 breast cancer cells were transfected with vector (V), ABCB1 (B1), or ABCC1 (C1) as indicated.

(A) Immunohistochemistry reveals that expressed ABCB1 and ABCC are localized to the plasma membrane. (B, C) S1P secreted from the indicated breast cancer cells was determined by LC-ESI-MS/MS. (D) Proliferation of cells treated with vehicle or 20 μM MK571 for 48 hours was determined by WST8 assay. Data are expressed as fold increase compared to 0 time. (E, F) Monolayers of the indicated 4T1 cells treated with vehicle or 20 μM MK57 were wounded and migration of cells into the wounded area was measured 24 h later. (E) Representative photographs of wounded areas are shown. (F) Cell migration was determined as percent of initial wounded area and expressed as means ± SD of 6 determinations. (G, H) HUVECs and HLECs were cultured on reduced growth factor basement membrane matrix-coated 48-well plates and incubated for 6 h without or with S1P (1 μM) or conditioned medium from MCF cells overexpressing ABCC1 (C1) were pretreated with vehicle (NC, non-treated control) or 20 μM MK571 without or with 10 μM SK1-I for 12 h and conditioned medium prepared. +M, treated with MK571; +S, treated with SK1-I. Six random fields per condition were photographed (G) and total tube length determined (H). Scale bars, 20 μm (A), 200 μm (E), 100 μm (G). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 determined by Student t test. Data are means ± SD.

Consistent with our previous reports demonstrating that S1P is exported via ABCC1 but not ABCB1 using siRNA (10), and specific inhibitors (20), overexpression of ABCC1, but not ABCB1, significantly increased S1P secretion from human MCF7 and murine 4T1 breast cancer cells, as measured by LC-ESI-MS/MS, (Fig. 2B,C). In addition, ABCC1 overexpression increased not only S1P, but also dihydro-S1P (DHS1P) (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Moreover, as expected, intracellular S1P was decreased while sphingosine (Sph) was increased (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Although, intracellular ceramides and sphingomyelins levels were slightly decreased (Supplementary Fig. S2C, S3A, and S3B), there was no significant changes in intracellular monohexosylceramides (Supplementary Fig. S2C, and S3C). Our results imply that overexpression of ABCC1 that increases secretion of S1P leads to increased degradation of ceramide to sphingosine to compensate for the loss of intracellular S1P.

We next examined several biological processes important for cancer progression known to be regulated by S1P (7,8). Overexpression of ABCC1 but not ABCB1, significantly enhanced cell proliferation (Fig. 2D). Moreover, MK571, an ABCC1 inhibitor, not only prevented secretion of S1P, but also suppressed the growth stimulating effect of ABCC1 overexpression (Fig. 2D). In agreement with previous reports showing that directly adding S1P enhances breast cancer cell proliferation and migration (17,32), cells expressing ABCC1 also showed significantly enhanced migration in scratch assays that was reduced by treatment with MK571. In contrast, MK571 had no significant effects on migration of vector or ABCB1 transfected cells (Fig. 2E,F). These results suggest that overexpression of ABCC1 increases the export S1P that enhances proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells.

Since S1P is a potent angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factor (18), we next examined whether S1P secreted from cells overexpressing ABC transporters could affect angiogenesis or lymphangiogenesis. Conditioned media from breast cancer cells expressing ABCC1, but not ABCB1 cells, promoted both angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and human lymphatic endothelial cells (HLEC), respectively (Fig. 2G,H). However, conditioned medium from MCF7 cells expressing ABCC1 that were treated with MK571, an inhibitor of ABCC1 or with SK1-I, a specific inhibitor of SphK1, lost its ability to stimulate in vitro angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis of endothelial and lymph endothelial cells, respectively (Fig. 2G,H). Collectively, these results suggest that S1P produced by SphK1 and secreted from breast cancer cells via ABCC1 transporter could affect not only the cancer cells themselves but also the microenvironment.

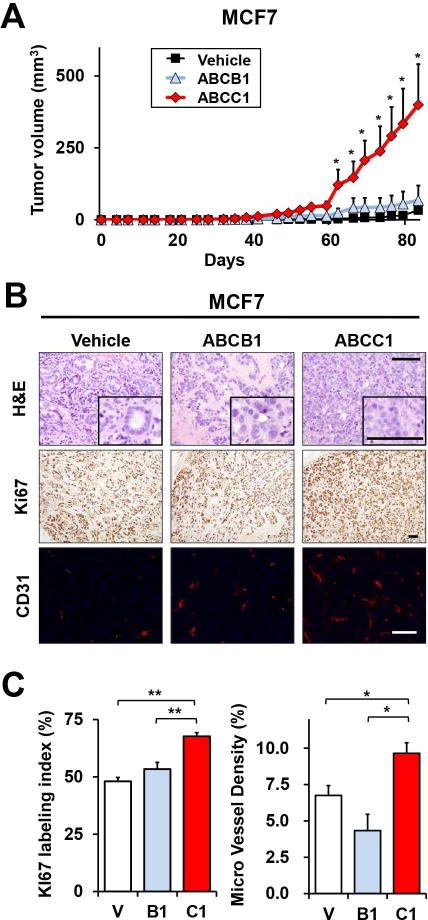

Overexpression of ABCC1, but not ABCB1, markedly enhances tumorigenesis in MCF7 xenografts

We next examined the role of ABCC1 and secreted S1P in breast cancer progression in vivo by comparing tumors produced by MCF7 cells stably overexpressing ABCC1 or ABCB1 implanted into ovariectomized athymic nude mice in the presence of estradiol pellets. MCF7 cells were utilized because they readily secrete S1P in response to estradiol (10). Tumors from MCF7 cells overexpressing ABCC1 grew significantly faster and were much larger than tumors from mice implanted with MCF7 cells overexpressing vector or ABCB1 (Fig. 3A). Morphologically, MCF7/C1 tumors appeared more poorly differentiated by H&E staining (Fig. 3B). In agreement, these tumors also had significantly higher mitotic activity than tumors from MCF7 cells overexpressing vector or ABCB1 by Ki67 staining (Fig. 3B,C). Likewise, mice implanted with MCF7 cells overexpressing ABCC1 had significantly higher blood vessel densities detected by CD31 immunofluorescence (Fig. 3B,C). These results suggest that overexpression of ABCC1 enhances breast cancer progression and angiogenesis.

Figure 3. Overexpression of ABCC1, but not ABCB1, enhances MCF7 tumor growth in a mouse xenograft model.

(A) BALB/c nude mice were ovariectomized and estrogen pellets implanted under anesthesia. Tumors were established by surgical implantation of MCF7 cells stably overexpressing vector, ABCB1, or ABCC1 into chest mammary fat pads. Tumor size was measured at the indicated times (n=5 mice per group). (B) Representative images of H&E and Ki67 staining and confocal immunofluorescent images of stained blood vessels with anti-CD31 (red) and nuclei co-stained with Hoechst (blue) in tumor sections 83 d after implantation. (C) Percentage of Ki67 positive cells and micro vessel density were determined. Scale bars, 100 μm. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 determined by Student t test. Data are means ± SEM.

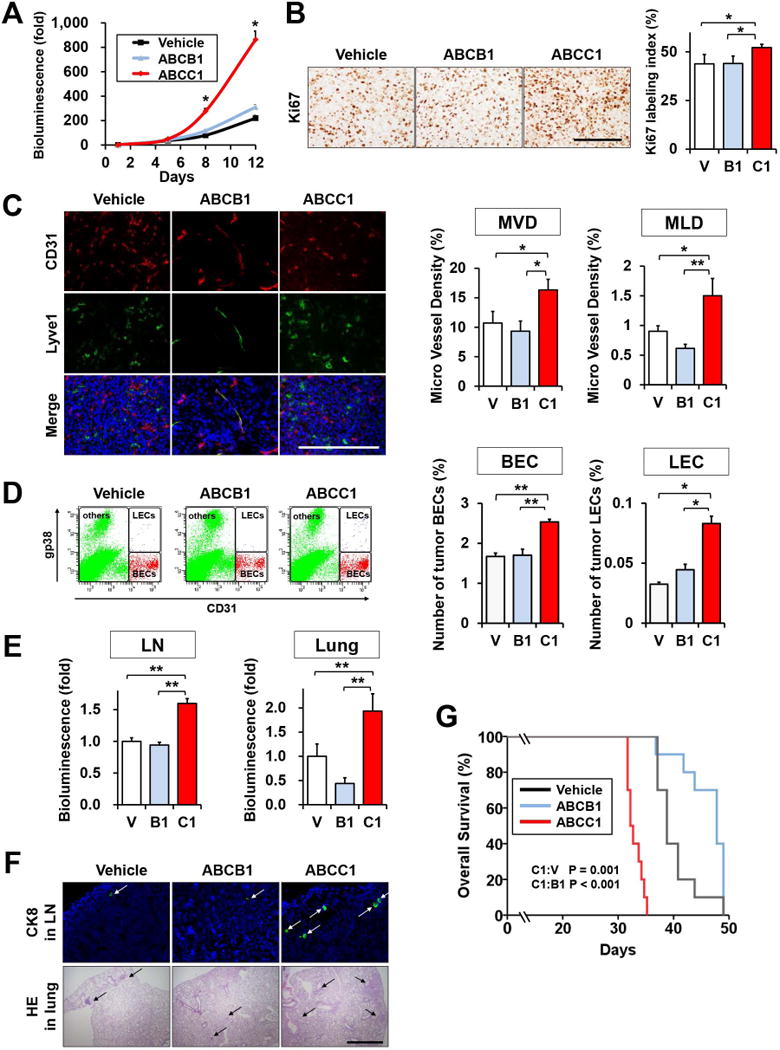

Overexpression of ABCC1, but not ABCB1, enhances tumor growth, angiogenesis, and lymphangiogenesis and contributes to poor survival of mice bearing 4T1 syngeneic tumors

Since it is well established that S1P plays critical roles in immune responses and affects the tumor microenvironment, we next examined the role of ABCC1 in an immunocompetent syngeneic breast cancer model. In vivo bioluminescence revealed that tumors from 4T1-luc2 cells overexpressing ABCC1 orthotopically implanted in BALB/C mice grew significantly faster and to a much greater size than 4T1-luc2 tumors overexpressing vector or ABCB1 (Fig. 4A). Similar to the xenograft model, tumors of 4T1 cells overexpressing ABCC1 also had high mitotic activity measured by Ki67 staining (Fig. 4B). These tumors also had increased angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis compared to tumors overexpressing ABCB1 or empty vector, as quantified by microvessel density of blood vessels (MVD) and lymphatic vessels (MLD) determined by immunofluorescence staining for CD31 and Lyve1, respectively (Fig. 4C). These results were further confirmed by flow cytometry of cells from mammary site tumors that quantified blood endothelial cells (BEC) and lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC) using CD31, a marker for both BEC and LEC, and gp38 (podoplanin), a specific marker for LEC (Fig. 4D). Given the significant increase in both angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis, we then determined lymph node and lung metastasis and survival of the mice. As shown in Fig. 4E, mice implanted with 4T1 cells overexpressing ABCC1 had significantly more metastases not only in lymph nodes but also in the lung, both measured by ex vivo bioluminescence, than in mice implanted with 4T1 cells overexpressing ABCB1. Similarly, the numbers of metastatic lesions were significantly greater in the mice bearing ABCC1 expressing tumors, determined by immunofluorescence and H&E staining (Fig. 4F). Furthermore, these mice had significantly shorter survival compared to mice bearing ABCB1 expressing tumors (23±3 days compared to 30±2 days) (Fig. 4G). Together, these results suggest that tumors overexpressing ABCC1 are much more aggressive with worse survival, possibly due to enhanced S1P secretion.

Figure 4. Overexpression of ABCC1, but not ABCB1, enhances 4T1 tumor growth and decreases survival in a syngeneic mouse model.

(A–F) 4T1-luc2 cells transfected with vector, ABCB1, or ABCC1 were implanted into mammary fat pads of BALB/c mice under direct vision (23). (A) Tumor burden was determined by in vivo bioluminescence (n=10 mice per group). (B) Representative images of Ki67 staining of tumor sections are shown and the percentage of Ki67 positive cells within tumors was enumerated. (n=5) (C) Confocal immunofluorescent images of tumors stained for blood vessels (anti-CD31, red), lymphatic vessels, (anti-lyve1, green), and nuclei (Hoechst, blue). Micro vessel density and lymphatic vessel density were determined. (D) Tumors were minced, digested with collagenase, and BECs and LECS were quantified by FACS. Representative panels of FACS analysis are shown. (E) Regional lymph node metastases and lung metastases were determined by ex vivo bioluminescence 12 d after implantation. (F) Confocal immune fluorescent images of lymph nodes stained for adenocarcinoma (anti-CK8, green, white arrows) and nuclei (Hoechst, blue) and H&E stained lung sections show metastases (black arrow). (G) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice bearing 4T1/V, 4T1/B1, and 4T1/C1 tumors. Days after cancer cell implantation. P values were calculated by log-rank test. Scale bars, 100 μm (B, C); 2 µm (F). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 based on Student t test. Data are means ± SEM.

S1P exported via ABCC1 upregulates transcription of SphK1 and enhances its own production of S1P

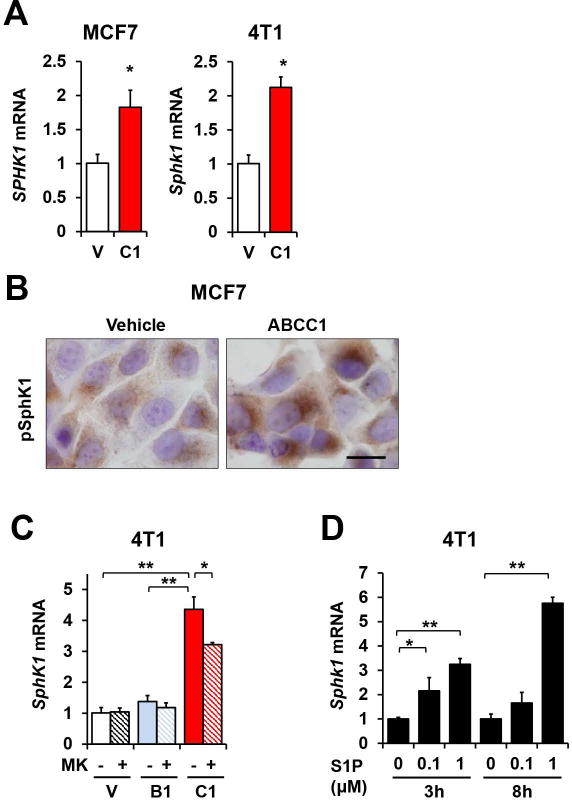

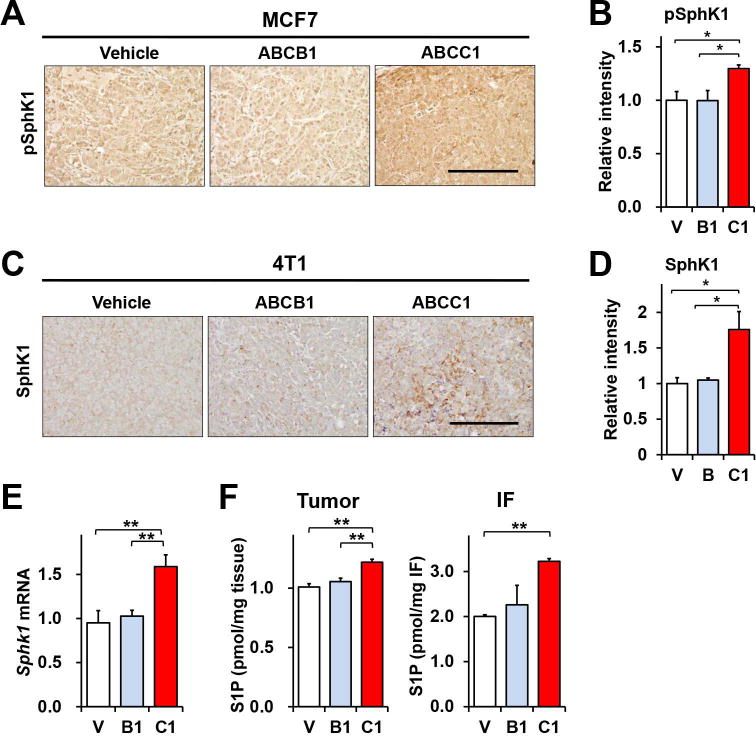

Previous studies demonstrated that expression of SphK1 is elevated (33,34) and correlates with poor survival in human breast cancer patients (13) and in mice breast cancer models (18). Therefore, it was of interest to determine expression of SphK1 in breast cancer cells and tumors overexpressing ABC transporters. SphK1 mRNA levels were significantly increased in both MCF7 and 4T1 cells overexpressing ABCC1 (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Fig. S4). Similarly, immunohistochemistry revealed increased activated SphK1 determined with a phospho-SphK1 specific antibody (Fig. 5B). Upregulation of SphK1 mRNA in cells overexpressing ABCC1 was suppressed by MK571, an ABCC1 inhibitor, but had no effects on SphK1 levels in cells overexpressing ABCB1 or vector (Fig. 5C). As these results suggest that S1P secreted through ABCC1 leads to upregulation of SphK1, the kinase that produces it, we next examined whether exogenous S1P can upregulate SphK1 in naive breast cancer cells. Indeed, SphK1 mRNA was increased by treatment of 4T1 cells with S1P in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5D), supporting the notion that S1P exported by ABCC1 can act in a positive feedback manner to amplify its own production. In agreement with this in vitro data, immunohistochemistry revealed that tumors overexpressing ABCC1 had higher levels of SphK1 and activated SphK1 than those expressing ABCB1 or vector (Fig. 6A,B,C, and D). Likewise, SphK1 mRNA expression was higher in tumors overexpressing ABCC1, as demonstrated by QPCR (Fig. 6E). Consistent with increased SphK1 expression, S1P levels in tumors and in tumor interstitial fluid were significantly higher in tumors overexpressing ABCC1 than tumors overexpressing ABCB1 or vector (Fig. 6F).

Figure 5. S1P exported via ABCC1 upregulates expression of SphK1.

(A) SphK1 expression in MCF7 and 4T1 cells transfected with vector or ABCC1 was determined by QPCR and normalized to GAPDH. Data are means ± SEM. (B) Activation of SphK1 in transfected MCF7 cells was determined by immunocytochemistry with pSphK1 antibody. Scale bars: 20 μm. (C) 4T1 cells transfected as indicated were treated with vehicle or 20 μM MK571 for 24 h in serum-free medium. Cells were then stimulated in medium containing 10% serum for 3 h. SphK1 mRNA levels were determined by QPCR and normalized to Gapdh. Data are means ± SD (D) Naïve 4T1 cells were starved for 24 h and treated with 100 nM or 1 μM S1P in 0.4% fatty acid free BSA for 3 or 8 hours as indicated. SphK1 and GAPDH mRNA was determined by QPCR.

Figure 6. Overexpression of ABCC1 in breast tumors enhances expression of SphK1 and increases S1P in tumor interstitial fluid.

(A, B) MCF7 cells transfected with vector, ABCB1, or ABCC1 were implanted into chest mammary fat pads of ovariectomized BALB/c nude mice. pSphK1 in tumors determined by immunohistochemistry on day 32. (C-E) 4T1-luc2 cells transfected with vector, ABCB1, or ABCC1 were implanted into mammary fat pads of BALB/c mice and tumors analyzed on day 12. SphK1 expression in 4T1 tumors was examined by staining with anti-SphK1 antibody. (B, D) Relative intensity of immunostaining was quantified by NIH ImageJ. Scale bars: 200μm. (E) Sphk1 mRNA level in tumors were determined by QPCR and normalized to Gapdh. (F) S1P levels in tumors (n=10) and in tumor interstitial fluid (n=5) were determined by LC-ESI-MS/MS. Data are means ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

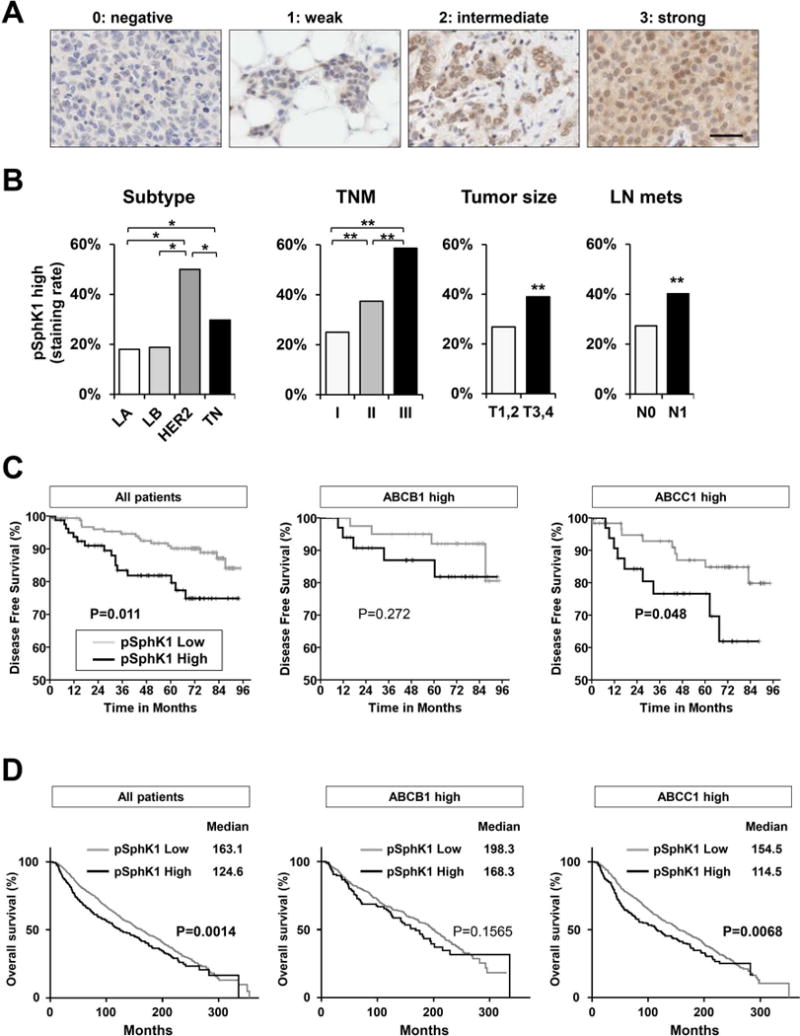

Patients with breast cancers that express both activated SphK1 and ABCC1 have shorter disease free survival

Because expression of ABCC1 in murine breast tumors upregulates SphK1 and decreases survival, we investigated whether increased expression of SphK1 and ABCC1 in human breast tumors could be a prognosis indicator. To this end, expression of ABCC1 and activated SphK1 in human breast cancer tissues was determined by immunohistochemistry of human breast tumor microarrays and ER, PgR, and HER2 status was determined by an expert pathologist and tumors divided into 4 subtypes of breast cancer: Luminal (ER+, HER2−); Luminal-HER2 (ER+, HER2+); HER2 (ER−, HER2+); and triple negative breast cancer (TNBC: ER−, HER2−) (Supplementary Table S1). Scoring of pSphK1 expression in human breast tumor samples were shown in Fig. 7A. The frequency of strong pSphK1 expression was higher in HER2 overexpressing or TNBC, the more aggressive breast cancer subtypes. pSphK1 was more prevalent and increased in a larger tumors (higher T stage) and in tumors from patients with lymph node metastases (higher TNM stage) (Fig. 7B, Supplementary Table S3). Finally, we correlated clinical outcomes with expression of pSphK1 and ABCC1. Importantly, patients with breast tumors that had higher expression of pSphK1 had worse disease free survival compared to those with weaker pSphK1 levels (P = 0.011; Fig. 7C). Strikingly, in patient tumors with high expression of both pSphK1 and ABCC1, disease free survival was significantly decreased (Fig. 7C). In contrast, there was no significant difference in survival of those expressing high levels of ABCB1 and pSphK1 (Fig. 7C). In agreement with previous studies showing that expression of SphK1 is elevated in patients with breast cancer and correlates with poor prognosis (13), mining of METABRIC breast tumor expression database showed that SphK1 expression significantly correlates with worse survival prognosis (median survival of 124 months with high SphK1 expression compared to 163 months for patients with low SphK1 expression, p=0.0014) (Fig. 7D). Furthermore, those with high levels of both SphK1 and ABCC1 had much worse prognosis with median survival of 114 months (p < 0.0068, Fig. 7D). Such correlations were not observed with ABCB1 expression (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7. Patients with breast cancers that express both activated SphK1 and ABCC1 have shorter disease free survival.

pSphK1 in 275 human breast tumors examined by immunohistochemistry. (A) Scoring of pSphK1 expression in human breast tumor samples. (B) Frequency of high pSphK1 expression in human breast tumors correlated with clinicopathological factors, tumor size, and lymph node metastasis status and TNM stage. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (C) Kaplan-Meier disease free survival curves according to expression of pSphK1, co-expression of pSphK1 with ABCB1, and co-expression of pSphK1 with ABCC1. P values were calculated by log-rank test. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of breast cancer patients from the METABRIC database. Data was obtained from patients with clinical and expression information. Median survival is tabulated along with a Log Rank p-value representing the significance of high gene expression of SphK1 among all patients, among ABCB1 high patients, or among ABCC1 high patients on patient survival.

Together, these findings support the notion that breast cancer patients with tumors that have high ABCC1 expression have poorer survival, at least in part, due to enhanced expression of SphK1 and secretion of S1P into the tumor microenvironment.

Discussion

Among the many known ABC transporters, ABCB1 and ABCC1 are two multidrug resistant proteins that are upregulated in breast cancer in response to chemotherapy and contribute to chemo-resistance (2). ABCB1 is the most well studied since it effluxes the commonly used anti-cancer drugs, anthracyclines and taxanes. However, clinical trials with agents targeting ABCB1 have all failed (35). Recent reports suggest that the functions of ABC transporters are not limited merely to the efflux of drugs as they also transport other types of molecules including lipids (36). Lipid-derived signaling molecules such as leukotrienes and prostaglandins, conjugated organic anions, and S1P have also been identified as substrates of multitasking ABCC1 transporter (37). Among them, the bioactive sphingolipid mediator S1P is now recognized as a critical regulator of many physiological processes important for breast cancer progression (38). S1P is generated inside cancer cells by SphK1, then exported outside of the cell into the tumor microenvironment where it can bind to five G protein-coupled receptors whose downstream signaling is responsible for most of the action of S1P. This “inside-out” signaling by S1P plays a pivotal role in cancer cells and in the tumor microenvironment by regulating inflammatory cells recruitment and stimulating angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis (39). SphK1 levels are upregulated in many malignant tumors including lung (40), kidney (33), colon (41), breast (13,18), prostate (42), stomach (43), liver (44), brain (45), in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (46), chronic myeloid leukemia (47), and has been reported to be associated with poor prognosis in several types of cancer, including esophageal (48), bladder (49), prostate (50), and breast (13,51). In agreement, we found that expression of SphK1 correlates with breast cancer staging. We also demonstrated for the first time that activated SphK1, determined with a phospho-SphK1 specific antibody, which is a direct reflection of S1P production, is associated with poor survival in human breast cancer. Interestingly, patients whose breast tumor had high expression of both activated SphK1 and ABCC1 had significantly shorter disease free survival, whereas no associations were observed with expression of ABCB1. These findings are consistent with the view that increased production of S1P by higher levels of pSphK1 and its increased efflux of S1P by ABCC1 combine to shorten survival.

It is now recognized that tumors display another level of complexity by regulating the tumor microenvironment (52). We demonstrated previously that S1P is increased in breast tumors and in their interstitial fluid that fills the space of the tumor microenvironment (26) and that S1P can enhance breast cancer-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis (18,53). In the current study, we have shown that S1P levels in tumor and interstitial fluid are higher in breast tumors that overexpress ABCC1. Furthermore, export of S1P by ABCC1 not only affected the cancer cells themselves and markedly enhanced tumor growth, it also influenced the tumor microenvironment, increasing angiogenesis, and lymphangiogenesis. It is thus not surprising that these rapidly growing tumors aggressively metastasized to lymph nodes or distant organs, and shortened survival of mice bearing these tumors. In sharp contrast, overexpression of ABCB1 could result in a slightly increased level of S1P around breast cancer cells that have very high endogenous SphK1, but the effects of small increases in S1P levels on physiological functions such as tumor progression and metastasis would not be expected to be significant. Our results suggest that export of S1P by ABCC1 is as important as production of S1P by SphK1 in cancer progression and in the tumor microenvironment.

Another unexpected and important finding in this study was that S1P exported via ABCC1 from breast cancer cells upregulated their expression of SphK1 leading to further increased production of S1P that in turn acts on the tumor cells themselves and on the tumor microenvironment. Hence, exported S1P acts in a malicious feed forward amplification loop to amplify the S1P axis that drives tumorigenesis and metastasis. Although not examined in the present study, the results of many previous studies suggest that these effects of S1P are mediated by binding to S1P receptors present on the cancer cells or on cells in the microenvironment, including endothelial and lymphendothelial cells (8). Similar to the shorter survival of mice bearing tumors overexpressing ABCC1 (that upregulates SphK1), patients with tumors that overexpress both SphK1 and ABCC1 have poor prognosis. Taken together, our results suggest that combined therapies that target SphK1 (S1P production) and ABCC1 (S1P secretion) should be more beneficial than targeting each of them alone or then inhibitors of ABCB1. Our study might also explain the failure of previous clinical trials targeting ABCB1. We suggest that ABCC1, not ABCB1, contributes to worse prognosis through the export of the potent lipid mediator, S1P, independently of its effects on efflux chemotherapeutic drugs. This represents a new concept of action of ABCC1 and a significant advancement in understanding of the role of ABC transporters in breast cancer, with the potential for applicability in other malignancies.

Supplementary Material

Implication statement.

Multidrug resistant transporter ABCC1 and activation of SPHK1 in breast cancer worsen patient’s survival by export of S1P to the tumor microenvironment to enhance key processes involved in cancer progression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jeremy Allegood for the lipidomics analyses. We thank Dr. Jorge A. Almenara, Director of the Anatomic Pathology Research Services (APRS), and the Tissue and Data Acquisition and Analysis Core (TDAAC) of VCU for technical assistance with tissue processing, sectioning and staining. The VCU Lipidomics and Microscopy Cores are supported in part by funding from the National Institutes of Health, NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016059.

Grant Support

This work was supported by NIH grants (R01CA160688 to K.T. and R01CA61774 to S.S.); Susan G. Komen Foundation Investigator Initiated Research Grant (IIR12222224) to K.T.; Department of Defense BCRP Program Award W81XWH-14-1-0086 to S.S., and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (16K19055 to A.Y., and 15H05676 and 15 K15471 to M.N.).

Abbreviations

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette transporter

- S1P

sphingosine-1-phosphate

- Sph

Sphingosine

- DHS1P

dihydrosphingosine-1-phosphate

- SphK

sphingosine kinase

- MDR1

multidrug resistance protein 1

- MRP1

multidrug resistance associated protein1

- S1PR

sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- HLEC

human lymphatic endothelial cells

- SK1-I

sphingosine kinase 1 inhibitor

- MVD

microvessel density of blood vessels

- MLD

microvessel density of lymphatic vessels

- BEC

blood endothelial cells

- LEC

lymphatic endothelial cells

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- ER

estrogen receptor

- PgR

progesterone receptor

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- TNBC

triple negative breast cancer,

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest:

No potential conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.DeSantis CE, Fedewa SA, Goding Sauer A, Kramer JL, Smith RA, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2015: Convergence of incidence rates between black and white women. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:31–42. doi: 10.3322/caac.21320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szakacs G, Annereau JP, Lababidi S, Shankavaram U, Arciello A, Bussey KJ, et al. Predicting drug sensitivity and resistance: profiling ABC transporter genes in cancer cells. Cancer cell. 2004;6:129–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fletcher JI, Haber M, Henderson MJ, Norris MD. ABC transporters in cancer: more than just drug efflux pumps. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:147–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Z, Shi T, Zhang L, Zhu P, Deng M, Huang C, et al. Mammalian drug efflux transporters of the ATP binding cassette (ABC) family in multidrug resistance: A review of the past decade. Cancer lett. 2016;370:153–64. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leonessa F, Clarke R. ATP binding cassette transporters and drug resistance in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10:43–73. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takabe K, Spiegel S. Export of sphingosine-1-phosphate and cancer progression. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:1839–46. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R046656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pyne NJ, Pyne S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:489–503. doi: 10.1038/nrc2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunkel GT, Maceyka M, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Targeting the sphingosine-1-phosphate axis in cancer, inflammation and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:688–702. doi: 10.1038/nrd4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takabe K, Paugh SW, Milstien S, Spiegel S. “Inside-out” signaling of sphingosine-1-phosphate: therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:181–95. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takabe K, Kim RH, Allegood JC, Mitra P, Ramachandran S, Nagahashi M, et al. Estradiol induces export of sphingosine 1-phosphate from breast cancer cells via ABCC1 and ABCG2. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10477–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagahashi M, Tsuchida J, Moro K, Hasegawa M, Tatsuda K, Woelfel IA, et al. High levels of sphingolipids in human breast cancer. J Surg Res. 2016;204:435–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuchida J, Nagahashi M, Nakajima M, Moro K, Tatsuda K, Ramanathan R, et al. Breast cancer sphingosine-1-phosphate is associated with phospho-sphingosine kinase 1 and lymphatic metastasis. J Surg Res. 2016;205:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruckhaberle E, Rody A, Engels K, Gaetje R, von Minckwitz G, Schiffmann S, et al. Microarray analysis of altered sphingolipid metabolism reveals prognostic significance of sphingosine kinase 1 in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9836-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watson C, Long JS, Orange C, Tannahill CL, Mallon E, McGlynn LM, et al. High expression of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors, S1P1 and S1P3, sphingosine kinase 1, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 is associated with development of tamoxifen resistance in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2205–15. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katoh SY, Ueno M, Takakura N. Involvement of MDR1 function in proliferation of tumour cells. J Biochem. 2008;143:517–24. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shida D, Fang X, Kordula T, Takabe K, Lepine S, Alvarez SE, et al. Cross-talk between LPA1 and epidermal growth factor receptors mediates up-regulation of sphingosine kinase 1 to promote gastric cancer cell motility and invasion. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6569–77. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang F, Van Brocklyn JR, Hobson JP, Movafagh S, Zukowska-Grojec Z, Milstien S, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate stimulates cell migration through a G(i)-coupled cell surface receptor. Potential involvement in angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35343–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagahashi M, Ramachandran S, Kim EY, Allegood JC, Rashid OM, Yamada A, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate produced by sphingosine kinase 1 promotes breast cancer progression by stimulating angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:726–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hait NC, Allegood J, Maceyka M, Strub GM, Harikumar KB, Singh SK, et al. Regulation of histone acetylation in the nucleus by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Science. 2009;325:1254–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1176709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitra P, Oskeritzian CA, Payne SG, Beaven MA, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Role of ABCC1 in export of sphingosine-1-phosphate from mast cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16394–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603734103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingberg E, Theodorsson A, Theodorsson E, Strom JO. Methods for long-term 17beta-estradiol administration to mice. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2012;175:188–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rashid OM, Nagahashi M, Ramachandran S, Dumur C, Schaum J, Yamada A, et al. An improved syngeneic orthotopic murine model of human breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;147:501–12. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3118-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rashid OM, Nagahashi M, Ramachandran S, Graham L, Yamada A, Spiegel S, et al. Resection of the primary tumor improves survival in metastatic breast cancer by reducing overall tumor burden. Surgery. 2013;153:771–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katsuta E, DeMasi SC, Terracina KP, Spiegel S, Phan GQ, Bear HD, et al. Modified breast cancer model for preclinical immunotherapy studies. J Surg Res. 2016;204:467–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terracina KP, Aoyagi T, Huang WC, Nagahashi M, Yamada A, Aoki K, et al. Development of a metastatic murine colon cancer model. J Surg Res. 2015;199:106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagahashi M, Yamada A, Miyazaki H, Allegood JC, Tsuchida J, Aoyagi T, et al. Interstitial Fluid Sphingosine-1-Phosphate in Murine Mammary Gland and Cancer and Human Breast Tissue and Cancer Determined by Novel Methods. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2016;21:9–17. doi: 10.1007/s10911-016-9354-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada A, Ishikawa T, Ota I, Kimura M, Shimizu D, Tanabe M, et al. High expression of ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCC11 in breast tumors is associated with aggressive subtypes and low disease-free survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:773–82. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2398-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sukocheva O, Wadham C, Holmes A, Albanese N, Verrier E, Feng F, et al. Estrogen transactivates EGFR via the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor Edg-3: the role of sphingosine kinase-1. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:301–10. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagahashi M, Shirai Y, Wakai T, Sakata J, Ajioka Y, Hatakeyama K. Perimuscular connective tissue contains more and larger lymphatic vessels than the shallower layers in human gallbladders. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4480–3. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i33.4480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curtis C, Shah SP, Chin SF, Turashvili G, Rueda OM, Dunning MJ, et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 2012;486:346–52. doi: 10.1038/nature10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pereira B, Chin SF, Rueda OM, Vollan HK, Provenzano E, Bardwell HA, et al. The somatic mutation profiles of 2,433 breast cancers refines their genomic and transcriptomic landscapes. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11479. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goetzl EJ, Dolezalova H, Kong Y, Zeng L. Dual mechanisms for lysophospholipid induction of proliferation of human breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4732–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.French KJ, Schrecengost RS, Lee BD, Zhuang Y, Smith SN, Eberly JL, et al. Discovery and evaluation of inhibitors of human sphingosine kinase. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5962–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shida D, Takabe K, Kapitonov D, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Targeting SphK1 as a new strategy against cancer. Curr Drug Targets. 2008;9:662–73. doi: 10.2174/138945008785132402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dean M. ABC transporters, drug resistance, and cancer stem cells. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2009;14:3–9. doi: 10.1007/s10911-009-9109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quazi F, Molday RS. Lipid transport by mammalian ABC proteins. Essays Biochem. 2011;50:265–90. doi: 10.1042/bse0500265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cole SP. Multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1, ABCC1), a “multitasking” ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:30880–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.609248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maceyka M, Harikumar KB, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling and its role in disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagahashi M, Takabe K, Terracina KP, Soma D, Hirose Y, Kobayashi T, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate transporters as targets for cancer therapy. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:651727. doi: 10.1155/2014/651727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song L, Xiong H, Li J, Liao W, Wang L, Wu J, et al. Sphingosine kinase-1 enhances resistance to apoptosis through activation of PI3K/Akt/NF-kappaB pathway in human non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1839–49. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawamori T, Osta W, Johnson KR, Pettus BJ, Bielawski J, Tanaka T, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 is up-regulated in colon carcinogenesis. FASEB J. 2006;20:386–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4331fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malavaud B, Pchejetski D, Mazerolles C, de Paiva GR, Calvet C, Doumerc N, et al. Sphingosine kinase-1 activity and expression in human prostate cancer resection specimens. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:3417–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W, Yu CP, Xia JT, Zhang L, Weng GX, Zheng HQ, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 is associated with gastric cancer progression and poor survival of patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1393–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi J, He YY, Sun JX, Guo WX, Li N, Xue J, et al. The impact of sphingosine kinase 1 on the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with portal vein tumor thrombus. Ann Hepatol. 2015;14:198–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J, Guan HY, Gong LY, Song LB, Zhang N, Wu J, et al. Clinical significance of sphingosine kinase-1 expression in human astrocytomas progression and overall patient survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6996–7003. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bayerl MG, Bruggeman RD, Conroy EJ, Hengst JA, King TS, Jimenez M, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 protein and mRNA are overexpressed in non-Hodgkin lymphomas and are attractive targets for novel pharmacological interventions. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:948–54. doi: 10.1080/10428190801911654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marfe G, Di Stefano C, Gambacurta A, Ottone T, Martini V, Abruzzese E, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 overexpression is regulated by signaling through PI3K, AKT2, and mTOR in imatinib-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Exp Hematol. 2011;39:653–65.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan J, Tao YF, Zhou Z, Cao BR, Wu SY, Zhang YL, et al. An novel role of sphingosine kinase-1 (SPHK1) in the invasion and metastasis of esophageal carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2011;9:157. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meng XD, Zhou ZS, Qiu JH, Shen WH, Wu Q, Xiao J. Increased SPHK1 expression is associated with poor prognosis in bladder cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:2075–2080. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pchejetski D, Bohler T, Stebbing J, Waxman J. Therapeutic potential of targeting sphingosine kinase 1 in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;8:569–678. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pyne S, Edwards J, Ohotski J, Pyne NJ. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors and sphingosine kinase 1: novel biomarkers for clinical prognosis in breast, prostate, and hematological cancers. Front Oncol. 2012;2:168. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aoyagi T, Nagahashi M, Yamada A, Takabe K. The role of sphingosine-1-phosphate in breast cancer tumor-induced lymphangiogenesis. Lymphat Res Biol. 2012;10:97–106. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2012.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.