Abstract

Discrepant drinking (i.e., differences in alcohol use) and perpetration of intimate partner violence in same-sex female couples were examined. Self-identified lesbian participants were recruited from market research firms and reported on their own and their partner’s alcohol use and their own perpetration of psychological aggression and physical violence at baseline, then 6- and 12- months later. Cross lagged panel analyses revealed that discrepant drinking predicted participants’ subsequent perpetration of psychological aggression but not physical violence. Both psychological aggression and physical aggression predicted subsequent discrepant drinking. Consistent with findings in heterosexual couples, differences in alcohol use appear to be a risk factor for relationship aggression.

Keywords: Alcohol use, Lesbian, Discrepant drinking, Partner Violence

Lesbian women are at increased risk for hazardous drinking and alcohol-related problems compared to heterosexual women (Drabble, Midanik, & Trocki, 2005; Green & Feinstein, 2012). Intimate partner violence (IPV), including physical violence and psychological aggression, between same-sex female partners occurs at a rate similar to or greater than IPV between opposite-sex partners (Edwards, Sylaska, & Neal, 2015; Walters, Chen, & Breiding, 2013; West, 2002). Among heterosexual couples, discrepancies in partners’ alcohol consumption have been associated with marital dissolution, relationship conflict, and IPV perpetration (Fischer & Wiersma, 2012). Similarly, among lesbian couples, discrepant alcohol use was associated with experiencing IPV and poorer relationship adjustment (Kelley, Lewis, & Mason, 2015). The purpose of the current study is to examine the link between discrepant drinking and physical and psychological aggression in a sample of women in same-sex relationships, measured longitudinally at three time points.

The relation between alcohol use and IPV, well established among heterosexual couples (Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012; Foran & O’Leary, 2008), has also been observed in cross-sectional studies of lesbian couples (Goldberg & Meyer, 2013; Eaton et al., 2008). Fortunata and Kohn (2003) compared batterers (defined as engaging in at least one act of physical violence in the past year) and nonbatterers in a sample of lesbian women and found that batterers had higher rates of alcohol problems. Similarly, in a sample of self-identified lesbians, frequency of drinking was significantly related to both committing abusive acts and being the victim of abusive acts where “abusive” was not defined (Schilit, Lie, & Montagne, 1990). Likewise, Kelly, Izienicki, Bimbi, and Parsons (2011) found that both alcohol use and previous substance abuse treatment were associated with mutual partner violence (including both physical and psychological aggression) in a sample of lesbian and bisexual women. Also, in cross-sectional analyses of Wave 1 of the data used for the current longitudinal study (Lewis, Mason, Winstead, & Kelley, 2017; Lewis et al., 2015) and other datasets (Mason, Lewis, Gargurevich, & Kelley, 2016), models incorporating alcohol use as a predictor of IPV have been supported.

The association between alcohol use and IPV may be understood theoretically from four perspectives (Wiersma et al., 2010): (1) Some other factor such as antisocial personality might explain both alcohol use and abusive behavior; (2) Important mediators such as relationship conflict explain an indirect association between drinking and IPV; (3) Proximal effects occur such that alcohol use impairs judgment, impulse control, and decision making that are directly related to violence; and (4) Discrepant drinking between partners that involves both indirect and proximal effects when differential alcohol use creates relationship conflicts (i.e., indirect effects) and/or heavy drinking serves as a proximal effect.

Despite the assumption that alcohol use leads to greater IPV, it is possible that the direction of influence is reversed or is mutual. Most research on this topic is cross-sectional and while tested models routinely support the drinking-IPV connection, few have examined the relationship longitudinally. When Schumacher, Homish, Leonard, Quigley, and Kearns-Bodkin (2008) examined excessive drinking and IPV across the first four years of marriage in a heterosexual sample, excessive drinking was longitudinally predictive of IPV only for husbands who were hostile. Similarly, Feingold, Washburn, Tiberio, and Capaldi (2015), studying both heavy episodic drinking and illicit drug use as predictors of IPV among romantic heterosexual couples, found no main effects. On the other hand, in a daily diary study with heterosexual married or cohabiting couples, Testa and Derrick (2014) found that the odds of perpetration of verbal and physical aggression by both female and male partners increased when alcohol was consumed. Nevertheless, the possibility that IPV also leads to alcohol or substance use, possibly as a way of coping, deserves further consideration.

Although the links of alcohol use with heterosexual marital functioning include marital dissatisfaction, negative interaction patterns, and higher levels of IPV (Fischer & Wiersma, 2012; Marshal, 2003; Stuart, O’Farrell, & Temple, 2009), research results have also suggested that light drinking and perhaps, especially shared drinking, might be adaptive (Wiersma, Cleveland, Herrera, and Fischer, 2010). This phenomenon has been referred to as the “drinking partnership.” On the flip side, discrepant drinking, or a pattern where one partner drinks more than or away from the other partner, may be particularly problematic in terms of relationship satisfaction, relationship dissolution, and IPV (Fischer & Wiersma, 2012).

Studies have examined the association between discrepant drinking and relationship satisfaction, a known correlate of IPV in heterosexual (Capaldi et al., 2012) and same-sex (West, 2014) couples. For example, in a longitudinal study of heterosexual couples, discrepancies in heavy alcohol use in the first year of marriage predicted decreased marital satisfaction, even controlling for drinking quantity (Homish & Leonard, 2007). Among heterosexual women, discrepant drinking was inversely associated with relationship satisfaction after controlling for partner’s physical and verbal aggression (Kelly & Halford, 2006). Similarly, in a cross-sectional sample of New Zealanders, couples reporting more happiness in their relationships also reported more congruence in both drinking frequency and drinking quantity (Meiklejoun, Connor, & Kypri, 2012). Research with heterosexual couples also suggests that discrepant drinking is associated with relationship dissolution (e.g., Leonard, Smith, & Homish, 2014; Torvik, Roysamb, Gustavson, Idstad, & Tambs, 2013). In the only study to our knowledge examining discrepant drinking among same-sex female couples, using data from wave 1 only of the longitudinal data set, discrepant drinking was related to lower relationship satisfaction (Kelley et al., 2015).

Regarding discrepant drinking and IPV in heterosexual couples, mixed findings have emerged. For example, in a national survey of family violence, despite most couples having similar drinking habits, couples with drinking discrepancies were more likely to experience alcohol-related arguments and physical violence (Leadley, Clark, & Caetano, 2000). In contrast, while finding that alcohol consumption was related to IPV in marriages, Testa et al. (2012) reported that discrepant drinking was related neither to the occurrence of IPV nor to the frequency of IPV. Similarly, Wiersma, et al. (2010) found no differences in IPV among four young adult couple types, based on drinking frequency and discrepancy. However, among married (as opposed to dating or cohabiting) couples, discrepant male heavy and frequent drinking couples reported more severe violence than congruent light and infrequent drinking couples.

Although deleterious effects of discrepant drinking have been found in heterosexual couples, much less is known about discrepant drinking and partner violence in same-sex relationships. In a cross-sectional study, using Wave 1 of the longitudinal data used in the current study, Kelley et al. (2015) found that, similar to findings among heterosexual couples, discrepant drinking was related to experiencing physical assault and psychological aggression in the relationship.

Most research to date on discrepant drinking and relationship variables is cross-sectional. As with alcohol use, which may be a predictor of IPV or possibly a response to it, couples who drink separately may be more likely to engage in IPV as a consequence or may be responding to dysfunction in the relationship (including IPV) by spending time (including drinking time) apart.

Current Study

There is evidence that discrepant drinking is associated with poorer relationship adjustment in heterosexual couples, and emerging evidence of a similar pattern in same-sex female relationships. Among heterosexual couples some studies support an association between discrepant drinking and IPV, whereas others do not. The only study to examine this among same-sex female couples suggested that discrepant drinking is associated with partner violence. Discrepant drinking or the drinking partnership has been studied almost exclusively in heterosexual couples and primarily with cross-sectional designs. The current study fills a gap in the literature by examining discrepant drinking in same-sex female partnerships with three assessments over a 12-month period and increases our understanding of the temporal association between drinking and IPV. Since longitudinal findings regarding discrepant drinking in heterosexual couples suggested that discrepant drinking is associated with subsequent relationship dissatisfaction (e.g., Homish & Leonard, 2007) and since daily diary data in heterosexual couples demonstrated that alcohol use predicts subsequent IPV (cf. Testa & Derrick, 2014), it is expected that discrepant drinking in same-sex female couples will be associated with subsequent IPV. In this cross-lagged panel study, however, we are also able to test the possibility that IPV in same-sex relationships predicts subsequent discrepant drinking.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Qualifying criteria for participation included:1) being a self-identified lesbian woman, 2) aged 18–35 years old, 3) being in a current romantic or dating relationship with another woman for at least three months; 4) seeing her partner physically at least once a month. The sample (n = 1052) was recruited from online market research panels in the U.S. The mean age of the sample was 28.79 years (SD = 4.29 years). Other demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of Sample

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | ||||

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 814 | 77.5 | - | - | - | - |

| African American | 109 | 10.4 | - | - | - | - |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 11 | 1.0 | - | - | - | - |

| Asian | 43 | 4.1 | - | - | - | - |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | 3 | 0.3 | - | - | - | - |

| Some other race alone | 43 | 4.1 | - | - | - | - |

| Two or more races | 15 | 1.4 | - | - | - | - |

| Prefer not to answer | 12 | 1.1 | - | - | - | - |

| Missing | 2 | 0.2 | - | - | - | - |

| Highest education level | ||||||

| High school graduate | 57 | 5.4 | - | - | - | - |

| Some college | 224 | 21.4 | - | - | - | - |

| Associate’s degree | 92 | 8.8 | - | - | - | - |

| Bachelor’s degree | 399 | 38.1 | - | - | - | - |

| Master’s degree | 218 | 20.8 | - | - | - | - |

| Doctoral/professional degree | 58 | 5.5 | - | - | - | - |

| Missing | 4 | 0.4 | - | - | - | - |

| Annual income | ||||||

| <$50,000 | 458 | 43.5 | - | - | - | - |

| $50,000 to <$100,000 | 357 | 34.0 | - | - | - | - |

| $100,000 to <$150,000 | 137 | 13.1 | - | - | - | - |

| >$150,000 | 45 | 4.2 | - | - | - | - |

| Declined to answer | 53 | 5.0 | - | - | - | - |

| Missing | 2 | 0.2 | - | - | - | - |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||

| Only homosexual/lesbian | 756 | 72.0 | - | - | - | - |

| Mostly homosexual/lesbian | 273 | 26.0 | - | - | - | - |

| Other | 21 | 2.0 | - | - | - | - |

| Missing | 2 | 0.2 | - | - | - | - |

| Relationship status | ||||||

| Single, dating in a casual relationship | 30 | 2.9 | 7 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Single, dating in a serious relationship | 51 | 4.9 | 13 | 3.2 | 3 | 1.4 |

| Partnered, in a casual relationship | 38 | 3.6 | 6 | 1.5 | 11 | 5.2 |

| Partnered, in a committed relationship | 669 | 63.7 | 231 | 56.9 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Partnered, married or in a civil union | 244 | 23.2 | 144 | 35.5 | 111 | 52.1 |

| Other | 18 | 1.7 | 5 | 1.2 | 85 | 39.9 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.2 | 646 | 61.4 | 839 | 79.8 |

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | ||||

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Cohabitating with partner | ||||||

| Yes | 777 | 74.1 | 332 | 82.2 | 173 | 82.4 |

| No | 271 | 25.9 | 72 | 17.8 | 37 | 17.6 |

| Missing | 4 | 0.4 | 648 | 61.6 | 842 | 80.0 |

| Frequency physically seeing partner | ||||||

| Daily | 819 | 78.0 | 343 | 84.5 | 186 | 87.3 |

| A few times a week | 101 | 9.6 | 30 | 7.4 | 10 | 4.7 |

| Once or twice a week | 55 | 5.2 | 6 | 1.5 | 5 | 2.3 |

| A few times a month | 41 | 3.9 | 13 | 3.2 | 6 | 2.8 |

| Monthly | 34 | 3.2 | 8 | 2.0 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Less than monthly | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 1.5 | 4 | 1.9 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.2 | 646 | 61.4 | 839 | 79.8 |

| Past year sexual behavior | ||||||

| Women only | 1001 | 95.3 | 408 | 93.6 | 210 | 90.9 |

| Women and men | 38 | 3.6 | 10 | 2.3 | 7 | 3.0 |

| Men only | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.7 | 3 | 1.3 |

| No one | 8 | 0.8 | 13 | 3.0 | 8 | 3.5 |

| Declined to respond | 3 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.5 | 3 | 1.3 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.2 | 616 | 58.6 | 821 | 78.0 |

| Sexual attraction | ||||||

| Only women | 612 | 58.3 | 237 | 54.4 | 135 | 58.4 |

| Most women | 433 | 41.2 | 185 | 42.4 | 88 | 38.1 |

| Equally men and women | 0 | 0.0 | 12 | 2.8 | 7 | 3.0 |

| Mostly men | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Only men | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Declined to respond | 5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.2 | 616 | 58.6 | 821 | 78.0 |

Note. Two cases had missing data for all variables at Time 1, but met study criteria at Time 2 (their first wave of data).

Participants were invited to join the online panels in various ways, including advertisements on popular websites. They were emailed invitations and received an incentive determined by the online panel to complete the survey (e.g., points or rewards that could be exchanged for gift cards or donated to a charity). All participants consented to participate in the study. Participants completed an online survey in approximately 30 minutes that included measures of physical aggression, psychological aggression, and self and partner drinking, from which discrepant drinking was derived. Data were collected at three waves: baseline (time 1), and then six months after baseline (time 2), and one year after baseline (time 3). Because two participants were added for the later waves that did not complete baseline, the participation rates were as follows: time 1 n = 1050 (99.8%), time 2 n = 436 (41.4%), and time 3 n = 231 (22.0%).

Measures

Physical aggression.

Participants completed the 12 perpetration items from the physical assault subscale and the six perpetration items from the injury subscale of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). Sample items of the physical assault subscale are “I slapped my partner” and “I slammed my partner against the wall.” Sample items of the injury subscale are “My partner needed to see a doctor because of a fight with me, but didn’t” and “My partner had a broken bone from a fight with me.” At baseline, participants indicated on a 7-point scale how often these events occurred in the past year. At 6- and 12- month follow up participants reported on the past six months. Response options ranged from never (0) to more than 20 times (6). Higher scores indicated more frequent perpetration of physical assault and injury. Validity of the CTS2 physical assault subscale has been established as evidenced by its significant correlations with masculinity, insecure attachment, and poor relationship quality among lesbian and gay adults (Balsam & Szymanski, 2005; McKenry, Serovich, Mason, & Mosack, 2006). Internal consistency was good for the current data (α = .88 for Time 1, α = .88 for Time 2, and α = .81 for Time 3 for all 18 items).

Psychological aggression.

The short form of the Psychological Maltreatment against Women (PMWI; Tolman, 1989) scale included 14 items and was used to assess perpetration of psychological aggression. Sample items include “I monitored her time and made her account for her whereabouts” and “I yelled and screamed at her.” Response options ranged from 0 (never) to 5 (not applicable). Significant associations between the PMWI and physical assault, poor mental health, and relationship intrusiveness among lesbian female perpetrators and victims demonstrate the validity of the PMWI (Mason et al., 2015). Internal consistency was excellent for the current data (α = .92 for Time 1, α = .93 for Time 2, and α =.94 for Time 3).

Discrepant drinking.

Participants reported on their own and their partner’s alcohol use using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). Participants were asked to report how many drinks they drink each day of a typical week for the past three months. They were asked to report the same information for their partner. Convergent validity of the DDQ has been demonstrated by its significant correlation with the Drinking Practices Questionnaire (DPQ; Collins et al., 1985). The average number of standard drinks consumed per drinking day was calculated for self and for partner. The alcohol discrepancy score represented the absolute value of the difference between participant average number of drinks per day and partner average number of drinks per day. This variable provides a direct representation of discrepant drinking habits, regardless of which partner drinks more. Given that the sex of both partners is the same, the absolute value approach seems most appropriate for the current population, and was confirmed with scatterplots indicating similar associations at larger values of discrepancy, regardless of who is the heavier drinker.

Analysis Approach

To examine the longitudinal influence of discrepant drinking on aggression as well as the influence of aggression on discrepant drinking, cross-lagged panel models (also known as auto-regressive models or panel models) were conducted using Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). Two models were conducted: one for perpetration of physical aggression and one for perpetration of psychological aggression. These models include two major components: autoregressive effects, and cross-lagged effects. Autoregressive effects control for previous levels of each construct at later waves (e.g., discrepant drinking at time 2 controlled for Discrepant drinking at time 1). Cross-lagged effects examine the relationship between two constructs across time (e.g., between discrepant drinking at time 2 and physical aggression at time 3, controlling for time 2 aggression). In addition, correlations among constructs within wave were included in each model. These models allowed for the simultaneous exploration of the relationship from aggression at time t to discrepant drinking at time t + 1, controlling for the influence of discrepant drinking at time t, in the same model. Missing select data points within a time wave with data present (<2%) were imputed using expectation maximization imputation. Maximum likelihood estimation was used to address missing time waves. To evaluate overall model fit, we used criteria suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999) including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > .95, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) > .95, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < .06, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < .08. We also examined “stationarity”, or that the influence of X on Y is the same over time. In other words, similar structural paths were constrained to equality (e.g., the influence of physical aggression at time 1 on drinking discrepancy at time 2 is equal to the influence of physical aggression at time 2 on drinking discrepancy at time 3). Consistent with recommendations for cross-lagged panel models (Kenny, 1979; Cole and Maxwell, 2003; Little, Preacher, & Selig, 2007) we compared model fit via likelihood ratio tests to determine if stationarity applied for cross-lagged effects and autoregressive effects separately.

Results

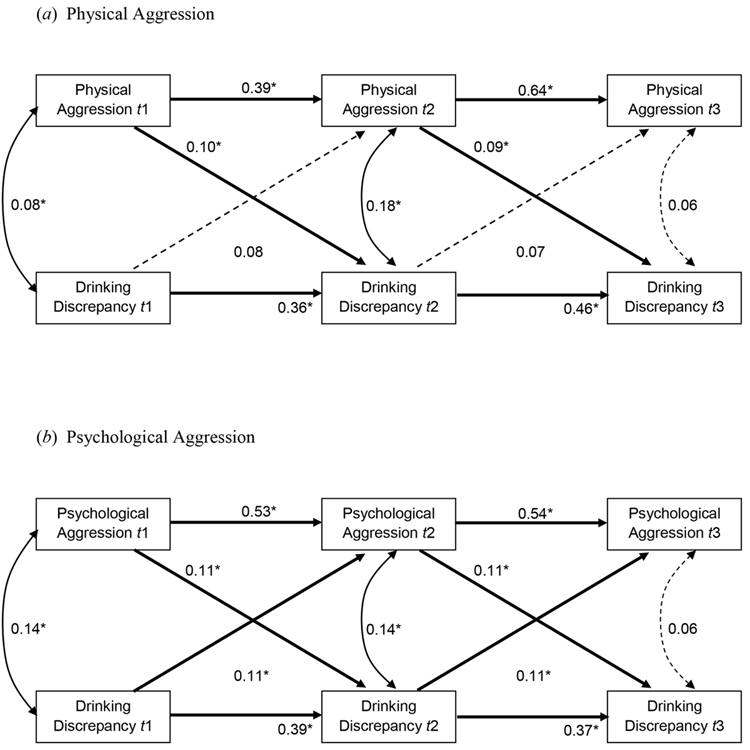

Physical aggression (via a sum of physical assault and injury perpetration scores) was cube root transformed to reduce skewness. Similarly, the absolute value drinking discrepancy variable was transformed by taking the natural log of the discrepancy plus a constant (i.e., 1) to avoid negative values, also to reduce skewness. Normality was confirmed for all variables after transformation. Descriptive information (i.e., means, SD, skewness, and kurtosis values) and correlations among study variables are in Table 2. Results for the cross-lagged panel models are included in Table 3 and graphically displayed in Figure 1. Tests of stationarity concluded that the cross-lagged effects had stationarity in both models (i.e., identical effects across time), but the autoregressive effects only had stationarity in the psychological aggression model. The physical aggression model showed significant decrement of fit when autoregressive stationarity constraints were added, so they remain unconstrained in the final model.

Table 2.

Descriptive Information and Correlations among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Physical Aggr. (t1) | - | ||||||||

| 2. Physical Aggr. (t2) | .43 | - | |||||||

| 3. Physical Aggr. (t3) | .36 | .67 | - | ||||||

| 4. Discrepancy (t1) | .06 | .09 | .04 | - | |||||

| 5. Discrepancy (t2) | .08 | .14 | .10 | .31 | - | ||||

| 6. Discrepancy (t3) | .03 | .44 | .33 | .27 | .60 | - | |||

| 7. Psychological Aggr. (t1) | .48 | .21 | .20 | .11 | .14 | .09 | - | ||

| 8. Psychological Aggr. (t2) | .32 | .56 | .38 | .15 | .17 | .27 | .51 | - | |

| 9. Psychological Aggr. (t3) | .30 | .44 | .55 | .11 | .12 | .23 | .43 | .59 | - |

| Mean | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 2.45 | 2.43 | 2.37 |

| SD | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 1.19 | 1.16 | 1.23 |

| Skewness | 2.43 | 2.32 | 2.08 | 1.37 | 1.51 | 1.51 | 0.34 | 0.03 | -0.02 |

| Kurtosis | 5.77 | 5.54 | 3.02 | 2.58 | 3.27 | 2.88 | 2.14 | 0.63 | 0.20 |

Note. Aggr. = aggression, t1 = time 1, t2 = time 2, t3 = time 3. Values represent cube root transformations for physical aggression, and natural log transformations of the absolute value for drinking discrepancy.

Table 3.

Results for Physical and Psychological Aggression Cross-Lagged Panel Models

| β | SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Aggression Model | |||

| Autoregressive Effects | |||

| Discrepant Drinking t1 → Discrepant Drinking t2 | 0.358* | 0.053 | <.001 |

| Discrepant Drinking t2 → Discrepant Drinking t3 | 0.463* | 0.080 | <.001 |

| Aggression t1 → Aggression t2 | 0.386* | 0.044 | <.001 |

| Aggression t2 → Aggression t3 | 0.641* | 0.038 | <.001 |

| Cross-Lagged Effects | |||

| Aggression t1 → Discrepant Drinking t2 | 0.103* | 0.047 | .029 |

| Aggression t2 → Discrepant Drinking t3 | 0.094* | 0.044 | .034 |

| Discrepant Drinking t1 → Aggression t2 | 0.076 | 0.041 | .067 |

| Discrepant Drinking t2 → Aggression t3 | 0.072 | 0.039 | .067 |

| Correlations within Timepoint | |||

| Discrepant Drinking t1 with Aggression t1 | 0.077* | 0.035 | .027 |

| Discrepant Drinking t2 with Aggression t2 | 0.175* | 0.064 | .006 |

| Discrepant Drinking t3 with Aggression t3 | 0.058 | 0.101 | .567 |

| Psychological Aggression Model | |||

| Autoregressive Effects | |||

| Discrepant Drinking t1 → Discrepant Drinking t2 | 0.388* | 0.046 | <.001 |

| Discrepant Drinking t2 → Discrepant Drinking t3 | 0.365* | 0.054 | <.001 |

| Aggression t1 → Aggression t2 | 0.528* | 0.029 | <.001 |

| Aggression t2 → Aggression t3 | 0.538* | 0.039 | <.001 |

| Cross-Lagged Effects | |||

| Aggression t1 → Discrepant Drinking t2 | 0.110* | 0.046 | .016 |

| Aggression t2 → Discrepant Drinking t3 | 0.114* | 0.047 | .016 |

| Discrepant Drinking t1 → Aggression t2 | 0.114* | 0.040 | .004 |

| Discrepant Drinking t2 → Aggression t3 | 0.106* | 0.037 | .004 |

| Correlations within Timepoint | |||

| Discrepant Drinking t1 with Aggression t1 | 0.135* | 0.034 | .002 |

| Discrepant Drinking t2 with Aggression t2 | 0.138* | 0.060 | .021 |

| Discrepant Drinking t3 with Aggression t3 | 0.064 | 0.086 | .459 |

Note. t[#] = time/wave. “Aggression” scores reflect perpetration of physical or psychological aggression, as defined by model label. Significant parameters are indicated with bold text.

p < .05

Figure 1.

Cross-lagged panel models for discrepant drinking with perpetration of physical aggression (a) and psychological aggression (b). t[#] = time/wave. Dashed paths and correlations are not significant. Note that cross-lagged effects in both models are constrained to equality over time, but autoregressive effects are constrained to equality across time only in the psychological aggression model due to significant decrement of fit for the physical aggression model. *p < .05

Physical aggression.

As seen in Table 3, autoregressive effects were significant for both physical aggression and discrepant drinking. In addition, physical aggression was associated with more discrepant drinking at later timepoints. No other cross-lagged effects were significant (i.e., drinking discrepancy was not associated with later physical aggression). Model fit suggested the hypothesized model adequately fit the data with good fit based on RMSEA = 0.053 (90% CI [0.032, 0.076]), and SRMR = 0.059, but CFI = 0.929, and TLI = 0.834, were slightly lower than desirable.

Psychological aggression.

Autoregressive effects were significant for both psychological aggression and discrepant drinking. In addition, discrepant drinking was associated with more psychological aggression at later timepoints, and psychological aggression was also then associated with more discrepant drinking at later timepoints (i.e., all cross-lagged effects were significant). Model fit suggested the hypothesized model adequately fit the data, with good fit based on RMSEA = 0.047 (90% CI [0.027, 0.067]), and SRMR = 0.069, but CFI = 0.935, and TLI = 0.887 were slightly lower than desirable.

Discussion

The link between alcohol use and IPV has been well established among heterosexual couples (see Fischer & Wiersma, 2012 for a review) but has received relatively little attention in the context of same-sex female couples. The lack of attention to relationship violence and alcohol use among sexual minority women is of particular concern in light of their elevated rates of alcohol problems. Further, there is a paucity of research regarding discrepant drinking. Given its association with poorer relationship outcomes, relatively well documented in heterosexual couples, it deserves attention in the sexual minority relationship research. To address this gap in the literature, this study examined the association of discrepant drinking patterns with IPV in same-sex female couples over a one-year period. Discrepant alcohol use in lesbian couples was associated with more psychological, but not physical, aggression over time suggesting that discrepant drinking may be an important risk factor for IPV in lesbian women’s intimate relationships. In addition, both psychological and physical aggression predicted future discrepant drinking. These findings add to the current literature in important ways. First, discrepant drinking has been associated with partner violence among heterosexual couples – the current findings support this link, at least in terms of psychological aggression, for same-sex female couples. Second, links between alcohol use and IPV among sexual minority women have been established in cross-sectional research but we have yet to investigate these associations over time. The longitudinal design of this study illuminates the temporal association between discrepant drinking and IPV. Specifically, differences in partner alcohol use are associated with subsequent psychological, but not physical aggression, six months later. In our community sample, the rates of physical aggression were relatively low with 19.5 percent of the participants reporting any past year physical violence which may have attenuated the association between discrepant drinking and physical violence.

In addition, both psychological and physical aggression predicted later discrepant drinking. Much of the existing literature focuses on the influence of alcohol use on relationship outcomes (e.g., Fischer & Wiersma, 2012; Marshal, 2003; Stuart et al., 2009), but the current findings highlight how IPV may also influence drinking patterns within a couple. Although we have only three waves of data, this pattern suggests how some couples may find themselves in a downward spiral as discrepant drinking leads to psychological aggression and instances of IPV lead to more discrepant drinking.

It is important to consider what unique mechanisms may underlie the association between discrepant drinking and alcohol use among lesbian women. It is possible that a difference in alcohol use between partners creates conflict and distress in the relationship that then escalates to the point of IPV. Although prediction from discrepant drinking to physical aggression was not statistically significant, the fact that discrepant drinking was associated with subsequent psychological aggression is noteworthy as psychological aggression is often as harmful as, and serves as a precursor to, physical violence (e.g., Jordan, Campbell, & Follingstad, 2010; Lawrence, Yoon, Langer, & Ro, 2009). Results also indicate that IPV leads to discrepant drinking. Trocki, Drabble, and Midanik (2005) found that lesbian women are more likely to go to bars than heterosexual women, and there is evidence that lesbian bars offer an important social venue in which to interact with other sexual minority women (Gruskin, Byrne, Kools, & Alschuler, 2007). Incidents of physical or psychological aggression in relationships may lead lesbian partners to choose different social activities and to spend time apart, including in activities that involve drinking. Engaging in different social activities, including discrepant drinking, may further undermine closeness in the relationship. In addition, women’s (sexual identity not specified) IPV perpetration was associated with subsequent depression (Johnson, Giordano, Longmore, & Manning, 2014) although in another study perpetration was associated with subsequent marijuana use but not depression or problematic alcohol use (Simmons, Knight, & Menard, 2015). It is possible that IPV is associated with discrepant drinking via negative affect and some partners’ drinking to cope with this negative emotion.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the results of this study increase our understanding of lesbian women’s alcohol use and IPV, several limitations must be noted. First, one partner provided information on herself and her partner. As a result, our measure of discrepant drinking is based on the respondent’s assessment of her own drinking and her partner’s drinking. Future research that collects data on alcohol use and relationship variables from both partners will facilitate better understanding of discrepant drinking. Also, as is the case in studies of IPV in community samples, there were relatively low rates of physical aggression. It is possible that discrepant drinking predicts physical aggression in couples where more physical violence occurs. Although desirable, as treatment programs for IPV in sexual minority women are virtually non-existent (see Winstead et al., in press, for a review), it would be very difficult to obtain a clinical sample in which these findings could be replicated. In addition, the participants in this study represent an online convenience sample of lesbians, limiting generalizability to the larger lesbian population or to bisexual women. We must also acknowledge the attrition rates at each wave. Although over 1,000 lesbian women began this study, less than only 231 participated in all three waves. The sparseness of the data precluded more complex examinations, including controlling for level of drinking by self or partner, a future area of research. Attrition is a significant problem in longitudinal research, especially for underserved populations (Leonard et al., 2003; Patel, Doku, & Tennakoon, 2003). Exploring a variety of strategies to enhance retention of participants over time is important for future research (see Booker, Harding, & Benzeval, 2011 for a review).

Finally, it is important for future research to consider what mediators may explain the temporal associations supported in this research. For example, it would be useful to examine whether relationship dissatisfaction or milder forms of conflict may explain why discrepant drinking leads to psychological aggression. It is possible that the lack of a shared activity such as drinking may create relationship problems or distance that escalates into violence. Similarly, models examining mediators such as how partners’ may differentially cope with individual and relationship distress may help elucidate why IPV leads to discrepant drinking.

Conclusions

Intimate partner violence is a significant public health problem that impacts same-sex as well as heterosexual relationships. Identifying individual or dyadic risk factors is a critical next step to reducing IPV in same-sex female couples. To date, limited research has examined risk factors in this understudied population, and existing research has been cross-sectional in design, limiting our ability to determine temporal associations. Based on the current longitudinal design, results are consistent with findings among heterosexual couples that discrepant drinking predicts subsequent psychological aggression. In addition, both physical and psychological aggression predict future discrepant drinking offering evidence for the cyclical nature of discrepant drinking and relationship violence over time. Our findings also add to the literature regarding potential harms (i.e., relationship violence) resulting from alcohol use among lesbian women.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) of the National Institutes of Health under award number R15AA020424 to Robin Lewis (PI). Abby L. Braitman is supported by a research career development award (K01- AA023849) from NIAAA. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The Harris Interactive Service Bureau (HISB) was responsible solely for the data collection in this study. The authors were responsible for the study’s design, data analysis, reporting the data, and data interpretation.

Biography

Robin J. Lewis, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology and the Director of Clinical Training for the clinical psychology Ph.D. program at Old Dominion University affiliated with the Virginia Consortium Program in Clinical Psychology. Her research focuses on sexual minority health and reducing health disparities for sexual minority women. She is particularly interested in how minority stress contributes to alcohol use and violence among sexual minority women.

Barbara A. Winstead, Ph.D. is professor of psychology at Old Dominion University and a clinical faculty member with the Virginia Consortium Program in Clinical Psychology. Her research focuses on gender and relationships, including interpersonal violence and unwanted pursuit/stalking and the effects of relationships and social support on coping with stress and illness.

Abby L. Braitman, Ph.D., is a research assistant professor at Old Dominion University. Her research explores risky health behaviors among emerging adults, particularly alcohol use, with a focus on the impact of social influence as well as developing techniques to strengthen and extend the effects of harm reduction interventions.

Phoebe Hitson, M.S., is an alumna of Old Dominion University, where she earned a B.S. in Psychology in 2013 and a M.S. in Experimental Psychology in 2016. She is currently a doctoral student in the Virginia Consortium Program in Clinical Psychology. Her research interests include unwanted pursuit, stalking, and intimate partner violence.

Footnotes

A portion of this research was presented at the 2015 Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT) annual meeting, Chicago, IL.

References

- Balsam KF, & Szymanski DM (2005). Relationship quality and domestic violence in women’s same-sex relationships: The role of minority stress. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 258–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00220.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Booker CL, Harding S, & Benzeval M (2011). A systematic review of the effect of retention methods in population-based cohort studies. BMC Public Health, 11, 249. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, & Kim HK (2012). A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 3, 231–280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, & Maxwell SE (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, & Marlatt GA (1985). Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 189–200. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Midanik LT, & Trocki K (2005). Reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems among homosexual, bisexual and heterosexual respondents: results from the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66, 111–120. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton L, Kaufman M, Fuhrel A, Cain D, Cherry C, Pope H, & Kalichman SC (2008). Examining factors co-existing with interpersonal violence in lesbian relationships. Journal of Family Violence, 23, 697–705. doi: 10.1007/s10896-008-9194-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Sylaska KM, & Neal AM (2015). Intimate partner violence among sexual minority populations: A critical review of the literature and agenda for future research. Psychology of Violence, 5, 112–121. doi: 10.1037/a0038656 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A, Washburn EJ, Tiberio SS, & Capaldi DM (2015). Changes in the associations of heavy drinking and drug use with intimate partner violence in early adulthood. Journal of Family Violence, 30, 27–34. doi: 10.1037/a0013250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JL, & Wiersma JD (2012). Romantic relationships and alcohol use. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 5, 98–116. doi: 10.2174/1874473711205020098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, & O’Leary KD (2008). Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortunata B, & Kohn CS (2003). Demographic, psychosocial, and personality characteristics of lesbian batterers. Violence and Victims, 18, 557–568. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.5.557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg NG, & Meyer IH (2013). Sexual orientation disparities in history of intimate partner violence: Results from the California Health Interview Survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28, 1109–1118. doi: 10.1177/08862605124593845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KE, & Feinstein BA (2012). Substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: An update on empirical research and implications for treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 265–278. doi: 10.1037/a0025424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin E, Byrne K, Kools S, & Altschuler A (2007). Consequences of frequenting the lesbian bar. Women & Health, 44, 103–120. doi: 10.1300/J013v44n02_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, & Leonard KE (2007). The drinking partnership and marital satisfaction: The longitudinal influence of discrepant drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical psychology, 75, 43–51. 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WL, Giordano PC, Longmore MA, & Manning WD (2014). Intimate partner violence and depressive symptoms during adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55, 39–55. doi: 10.1177/0022146513520430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan CE, Campbell R, & Follingstad D (2010). Violence and women’s mental health: The impact of physical, sexual, and psychological aggression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 607–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-090209-151437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, Lewis RJ, & Mason TB (2015). Discrepant alcohol use, intimate partner violence, and relationship adjustment among lesbian women and their same-sex intimate partners. Journal of Family Violence, 30, 977–986. doi: 10.1007/s10896-015-9743-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AB, & Halford WK (2006). Verbal and physical aggression in couples where the female partner is drinking heavily. Journal of Family Violence, 21, 11–17. doi: 10.1007/s10896-005-9003-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, Izienicki H, Bimbi DS, & Parsons JT (2011). The intersection of mutual partner violence and substance use among urban gays, lesbians, and bisexuals. Deviant Behavior, 32, 379–404. doi: 10.1080/01639621003800158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA (1979). Correlation and causality. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Yoon J, Langer A, & Ro E (2009). Is psychological aggression as detrimental as physical aggression? The independent effects of psychological aggression on depression and anxiety symptoms. Violence and Victims, 24, 20–35. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadley K, Clark CL, & Caetano R (2000). Couples’ drinking patterns, intimate partner violence, and alcohol-related partnership problems. Journal of Substance Abuse, 11, 253–263. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00025-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Smith PH, & Homish GG (2014). Concordant and discordant alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use as predictors of marital dissolution. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28, 780–789. doi: 10.1037/a0034053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard NR, Lester P, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mattes K, Gwadz M, & Ferns B (2003). Successful recruitment and retention of participants in longitudinal behavioral research. AIDS Education and Prevention, 15, 269–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Mason TB, Winstead BA, & Kelley ML (2017). Empirical investigation of a model of sexual minority specific and general risk factors for intimate partner violence among lesbian women. Psychology of Violence, 7, 110–119. doi: 10.1037/vio0000036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Padilla MA, Milletich RJ, Kelley ML, Winstead BA, Lau-Barraco C, & Mason TB (2015). Emotional distress, alcohol use, and bidirectional partner violence among lesbian women. Violence against Women, 21, 917–938. doi: 10.1177/1077801215589375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Preacher KJ, Selig JP & Card NA (2007). New developments in latent variable panel analyses of longitudinal data. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31, 357–365. doi: 10.1177/0165025407077757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP (2003). For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 959–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason TB, Gargurevich M, & Lewis RJ (2015). Minority stress, mental health outcomes, and IPV. Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- Mason TB, Lewis RJ, Gargurevich M, & Kelley ML (2016). Minority stress and intimate partner violence perpetration among lesbians: Negative affect, hazardous drinking, and intrusiveness as mediators. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3, 236–246. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKenry PC, Serovich JM, Mason TL, & Mosack K (2006). Perpetration of gay and lesbian partner violence: A disempowerment perspective. Journal of Family Violence, 21, 233–243. doi: 10.1007/s10896-006-9020-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meiklejohn J, Connor JL, & Kypri K (2012). Drinking concordance and relationship satisfaction in New Zealand couples. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 47, 606–611. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén BO (1998-2015). Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén [Google Scholar]

- Patel M, Doku V, & Tennakoon L (2003). Challenges in recruitment of research participants. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 9 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Schilit R, Lie GY, & Montagne M (1990). Substance use as a correlate of violence in intimate lesbian relationships. Journal of Homosexuality, 19, 51–66. doi: 10.1300/J082v19n03_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Quigley BM, Kearns-Bodkin JN (2008). Longitudinal moderators of the relationships between excessive drinking and intimate partner violence in the early years of marriage. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0013250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SB, Knight KE, & Menard S (2015). Consequences of intimate partner violence on substance use and depression for women and men. Journal of Family Violence, 30, 351–361. doi: 10.1007/s10896-015-9691-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, & Sugarman DB (1996). The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17, 283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, O’Farrell TJ, & Temple JR (2009). Review of the association between treatment for substance misuse and reductions in intimate partner violence. Substance Use and Misuse, 44, 1298–1317. doi: 10.1080/10826080902961385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Kubiak A, Quigley BM, Houston RJ, Derrick JL, Levitt A, ... & Leonard KE (2012). Husband and wife alcohol use as independent or interactive predictors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73, 268–276. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, & Derrick JL (2014). A daily process examination of the temporal association between alcohol use and verbal and physical aggression in community couples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28, 127–138. doi: 10.1037/a0032988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM (1989). The development of a measure of psychological maltreatment of women by their male partners. Violence and Victims, 4, 159–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torvik FA, Roysamb E, Gustavson K, Idstad M, & Tambs K (2013). Discordant and concordant alcohol use in spouses as predictors of marital dissolution in the general population: Results from the hunt study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37, 877–884. doi: 10.1111/acer.12029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trocki KF, Drabble L, & Midanik L (2005). Use of heavier drinking contexts among heterosexuals, homosexuals and bisexuals: Results from a national household probability survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66, 105–110. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2205.66.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ML, Chen J, & Breiding MJ (2013). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 findings on victimization by sexual orientation Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- West CM (2002). Lesbian intimate partner violence: Prevalence and dynamics. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 6, 121–127. doi: 10.1300/J155v06n01_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West CM (2012). Partner abuse in ethnic minority and gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender populations. Partner Abuse, 3, 336–357. [Google Scholar]

- Wiersma JD, Cleveland HH, Herrera V, & Fischer JL (2010). Intimate partner violence in young adult dating, cohabitating, and married drinking partnerships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 360–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00705.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstead BA, Lewis RJ, Kelley ML, Mason TB, Calhoun DM, & Fitzgerald HN (in press). Intervention for violence and aggression in gay and lesbian relationships In Sturmey P (Ed.), The Wiley Handbook on Violence and Aggression. Wiley. [Google Scholar]