Abstract

Neuroactive steroids are potent positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors (GABAAR), but the locations of their GABAAR binding sites remain poorly defined. To discover these sites, we synthesized two photoreactive analogs of alphaxalone, an anesthetic neurosteroid targeting GABAAR, 11β-(4-azido-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorobenzoyloxy)allopregnanolone, (F4N3Bzoxy-AP) and 11-aziallopregnanolone (11-AziAP). Both photoprobes acted with equal or higher potency than alphaxalone as general anesthetics and potentiators of GABAAR responses, left-shifting the GABA concentration – response curve for human α1β3γ2 GABAARs expressed in Xenopus oocytes, and enhancing [3H]muscimol binding to α1β3γ2 GABAARs expressed in HEK293 cells. With EC50 of 110 nM, 11-AziAP is one the most potent general anesthetics reported. [3H]F4N3Bzoxy-AP and [3H]11-AziAP, at anesthetic concentrations, photoincorporated into α- and β-subunits of purified α1β3γ2 GABAARs, but labeling at the subunit level was not inhibited by alphaxalone (30 μM). The enhancement of photolabeling by 3H-azietomidate and 3H-mTFD-MPAB in the presence of either of the two steroid photoprobes indicates the neurosteroid binding site is different from, but allosterically related to, the etomidate and barbiturate sites. Our observations are consistent with two hypotheses. First, F4N3Bzoxy-AP and 11-aziAP bind to a high affinity site in such a pose that the 11-photoactivatable moiety, that is rigidly attached to the steroid backbone, points away from the protein. Second, F4N3Bzoxy-AP, 11-aziAP and other steroid anesthetics, which are present at very high concentration at the lipid-protein interface due to their high lipophilicity, act via low affinity sites, as proposed by Akk et al. (Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34S1, S59–S66).

Graphical Abstract

Azide and diazirine analogs of the neurosteroid general anesthetic drug, alphaxalone, were synthesized and were found to efficiently photolabel heteropentameric GABAA receptors.

INTRODUCTION

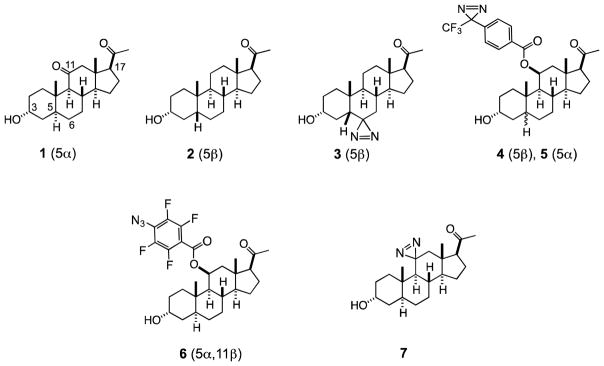

Alphaxalone (1) is a potent synthetic neurosteroid modulator of GABAAR,1–3 a member of a class of compounds that are analogs of endogenous GABAAR modulators, such as certain pregnanolones and corticosterones.4 Neurosteroids were clinically used as anesthetics in the past, but have been withdrawn due to toxic and other unwanted effects.5,6 Some of these compounds are still used in veterinary medicine, or remain in clinical evaluations.7,8 The binding site(s) for neurosteroids is/are different from those of etomidate, propofol, barbiturate and benzodiazepines, and presumably located deeper in the transmembrane domains.9 The pharmacology of these steroids differs from the other modulators mentioned above, especially with regard to δ-subunit-containing receptors.9 These intriguing features of their action make them worthwhile targets of investigation.

Our design of a neurosteroid photoprobe is based on the emerging pharmacophore for this class of compounds.10–14 Briefly, steroids featuring both planar (1, allopregnanolone-type, 5α) and kinked (2, pregnanolone-type, 5β) scaffold geometry at the A/B ring junction are active,10 however, 5α-isomers display much larger difference between activities of natural and unnatural enantiomers,10 potentially indicating different binding sites for 5α- and 5β-isomers. The presence of the 3α-hydroxyl group is essential,11 whereas the 3β-position can be substituted with a variety of alkyl and aryloxyalkyl appendices.11 Interestingly, both enantiomers of the steroids are effective ligands, but they seem to bind in different orientations; the natural enantiomers (eg. 1 & 2, shown above) bind with the upper edge of their steroid framework pointing out of the cavity, whereas the unnatural enantiomers (not shown) bind with the upper edge of their steroid framework pointing into the cavity.12 Consistently, the 11-position of the natural enantiomer of the steroid can be functionalized with sterically large groups,12,13 but in contrast, the 6-position of the natural enantiomer can be modified with only a small group, such as a diazirine.15,16 The presence of the oxygenated group at the 11-position is nonessential, but if hydroxylated, the 11β-configuration is preferred.16 The 17-position can be altered by a replacement of the acetyl group with a keto-group or 17β-nitrile, suggesting that the modulatory activity relies on the presence of a dipole in this part of molecule.14 The only neurosteroid-based photoprobes reported thus far are 6-azipregnanolone (3),15 and 11β-(p-TFD-benzyloxy)pregnanolones 4 and 5.17 The photoprobe 3 has photolabeled Phe301 in the M3 helix of the homomeric β3 receptor. However, it remains unclear if this residue is present at the steroid binding site, since inhibition of photolabeling (or even attempts at) by a pregnanolone drug was not reported.16

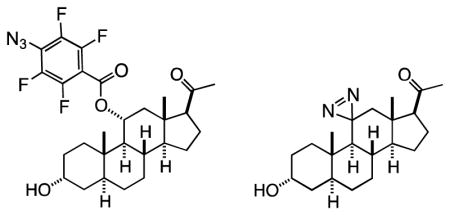

Given the existing SAR described above and the large size of the steroid scaffold, it should be possible to use photolabels to define not only the steroid site or sites of action, but also their orientation in the binding site. Our strategy in pursuit of this goal is to construct four types of photolabels, where the photoreactive residue is attached at the top (C-11), bottom (C-6), left (C-3) and right sides (C-17) of the steroid framework. In this manuscript, we report the synthesis of the two C-11-modified photoprobes, 11β-(p-azidotetrafluorobenzoyloxy)allopregnanolone (6, F4N3Bzox-AP), and 11-aziAP (7, 11-AziAP), and their use for the photolabeling of the α1β3γ2 isoform of the GABAA receptor.

RESULTS

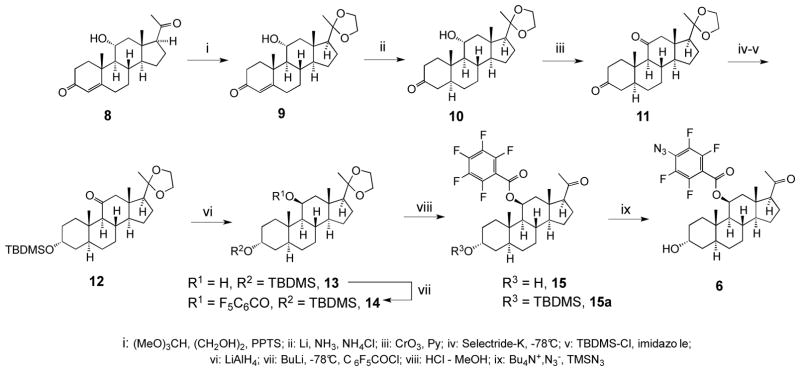

Synthesis of 11β-(4-azido-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorobenzoyloxy)allopregnanolone 6 (F4N3Bzox-AP)

The 9-step synthesis of the compound 6 shown in Scheme 1 started from the commercially available 11α-hydroxyprogesterone 8, which, under mild condition, was selectively converted into the 20-ketal 9. The double bond at the 4-position was stereoselectively reduced with lithium in liquid ammonia18 into the 5α-isomer 10, and the 11α-hydroxy group was inverted into 11β orientation by the oxidation-reduction sequence. Toward this goal, the 11α-hydroxyl was first oxidized with pyridinium dichromate, and the resulting 3,11-diketone 11 was regio- and stereo-selectively reduced at the 3-position with Selectride-K into the 3α-alcohol and silylated with dimethyl-tert-butylsilyl chloride to generate compound 12. The 11-keto group was subsequently stereoselectively reduced into 11β-alcohol 13 with lithium aluminium hydride, and the 11-hydroxyl group was acylated with pentafluorobenzoyl chloride into the corresponding ester 14. The silyl and ketal protective groups were removed by acidic methanolysis to afford the penultimate intermediate 15. In the final step, compound 15 was converted into the azide 6 by the substitution of the fluoride at the p-position of pentafluorobenzoate using tetra-n-butylammonium azide – TMS azide reagent.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of F4N3Bzox-AP 6.

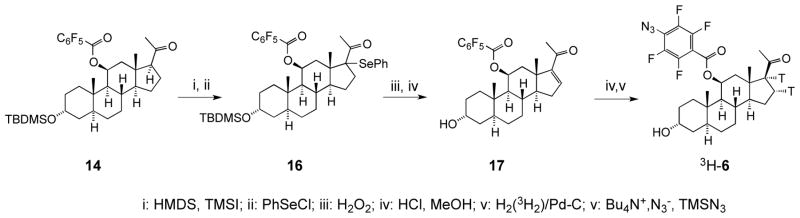

Tritiation of F4N3Bzox-AP 6

The synthesis of the tritiated photoprobe 3H-6 is shown in Scheme 2. While the simplest way to introduce tritium into 6 would comprise the oxidation-reduction sequence at the 3-position, such procedure with the available highly trititated agents (e.g. NaBT4) would provide predominantly an undesirable 3β-isomer.19 We opted instead for introduction of tritium via saturation of the double bond, that typically also provides higher specific radioactivity due to incorporation of two tritium atoms per probe molecule. Here, the treatment of the intermediate 15a with TMS iodide in the presence of hexamethyldisilazane produced the corresponding enol silyl ether, and addition of phenylselenyl chloride into the double bound afforded the selenide 16. Oxidation into selenoxide with hydrogen peroxide resulted in a spontaneous elimination, while the deprotection of the 3-silyl group with HCl in methanol yielded the α,β-unsaturated ketone 17. In a small-scale reaction, hydrogenation of the double bond over palladium catalyst afforded cleanly a 17β-acetyl product 15, while the subsequent in situ azidation produced 6, that was identical to that produced via Scheme 1. Finally, using this optimized procedure, the reduction of the double bond in 17 with tritium gas followed by azidation was performed by Vitrax Co. to afford 3H-6 with specific radioactivity of 45 Ci/mmol.

Scheme 2.

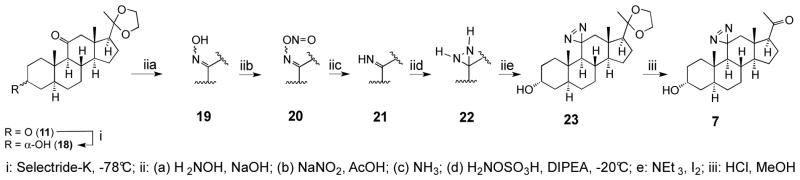

Synthesis of 11-aziallopregnanolone 7 (11-aziAP)

Starting from the diketone 11 (Scheme 3), the reduction at the 3-position with Selectride-K afforded stereoselectively the α-alcohol 18. It is noteworthy that due to very high steric hindrance, the reduction of the 11-keto group was not observed. Due to this steric hindrance, however, application of the typical general procedure used for the installation of the diazirine residue at position-11 was not successful. Instead, we used an alternative method involving transient formation of ketimine20 applicable to highly hindered ketone substrates. This procedure consisted of five steps carried out sequentially without purification of the intermediates, including formation of the oxime 19, its nitrosation into the nitrite 20, formation of the imine 21, the reaction of the imine with hydroxylamine sulfonic acid to form the diaziridine 22, and its oxidation with iodine into the diazirine 23 in a very low overall yield. Finally, the hydrolysis of the 20-ketal afforded the ultimate compound 7.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 11-aziallopregnanolone 7 (11-aziAP).

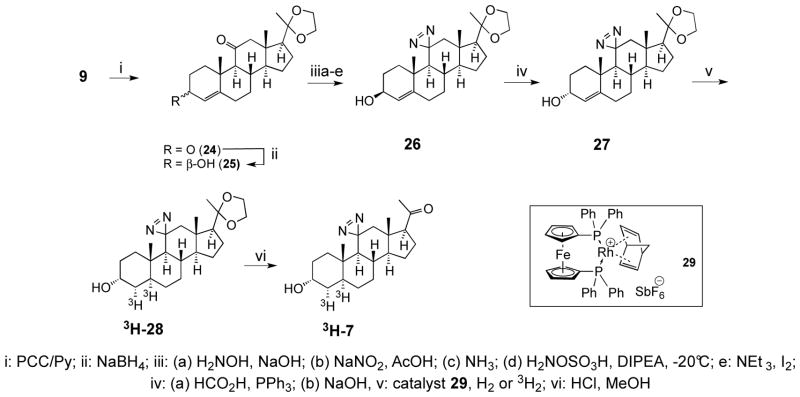

Tritation of the photoprobe 7

Our tritiation procedure was based on the saturation of the double bond at the 4-position using a modification of Scheme 3, whereby the assembly of a diazirine was performed at the 4-ene analog of 23 and the catalytic saturation of the double bond was carried out just before the ultimate ketal deprotection. The synthesis of tritiated 3H-7 is shown in the Scheme 4.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of tritiated 11-aziAP 3H-7.

Here, the intermediate 9 from the above (Scheme 1) was oxidized at the 11-position with chlorochromate in pyridine into a diketone 24, and the 3-keto group was reduced with sodium borohydride to provide the 3-β alcohol 25. This compound was subjected to diazirination as described above to provide the diazirine 26, and the alcohol function was inverted using the Mitsunobu procedure to provide the 3-α-alcohol 27. The critical step of stereoselective hydrogenation to provide the 5α-intermediate 28 was carried out using the homogeneous rhodium catalyst 29. Lastly, hydrolysis of the ketal group afforded the product 7 that was indistinguishable from that produced via Scheme 3. Saturation of the double bond in compound 27 with a tritium gas, carried out by Vitrax Co., followed by hydrolysis of the ketal group afforded the tritiated photoprobe 3H-7 with an estimated specific radioactivity of 40 Ci/mmol.

Proof of structures of photoprobes 6 and 7

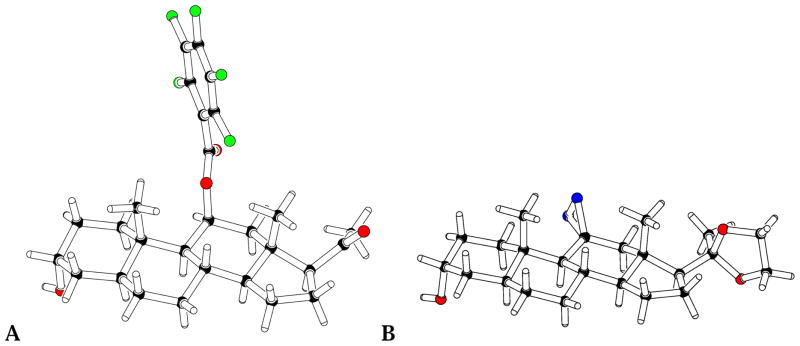

Given that 1H NMR analyses did not provide the necessary clarity with regard to the stereochemical structures of the final products, we have obtained the structural proof in the form of x-ray structures. Although we were unsuccessful in crystallizing the final products 6 and 7, we obtained the crystalline forms of the penultimate intermediates 15 and 28, and solved their x-ray crystal structures (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

X-ray structures of compounds 15 (A) and 28 (B), the penultimate intermediates in the syntheses F4N3Bzox-AP 4 and 11-azi-allopregnanolone 7, respectively.

The x-ray data prove unequivocally that these compounds, and hence by inference, also the final compounds 6 and 7, have the desired stereochemical structures.

Pharmacological Properties

Anesthetic Potency of F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-AziAP

The anesthetic potency of F4N3Bzox-AP was studied as loss of righting reflexes (LoRR) in tadpoles, using the concentration range from 30 nM to 10 μM, and compared to alphaxalone as a reference. Similarly, 11-aziAP was studied over the 10 nM – 1 μM range. Anesthesia with all agents was reversible, and all animals recovered within an hour after transfer to fresh water. The potency of the F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-aziAP were 2.6- and 17-fold greater, respectively, than that of alphaxalone. [Agent, EC50 (μM), Slope, # of animals: Alphaxalone, 1.9 ± 0.36 μM, 1.7 ± 0.5, 51; F4N3Bzox-AP, 0.72 ± 0.09 μM, 2.1 ± 0.68, 70; 11-aziAP, 110 ± 18 nM, 1.7 ± 0.5, 70, Errors are standard deviations].

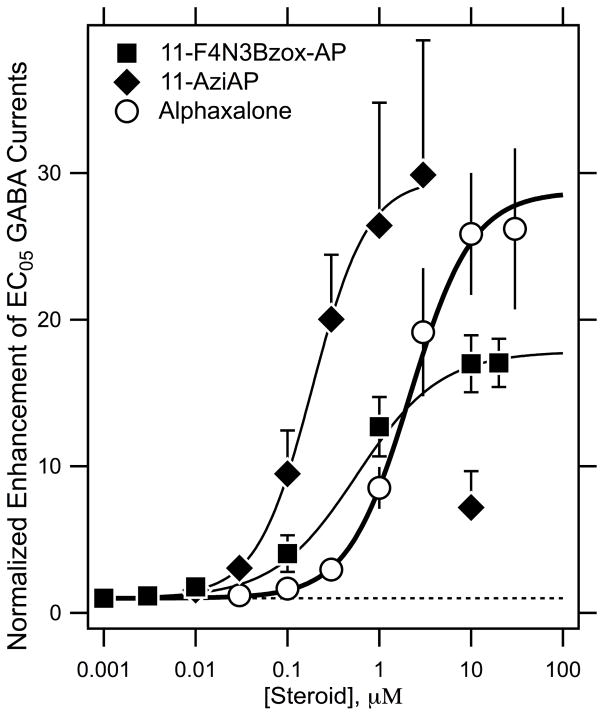

Enhancement of the GABAA Receptor Currents by F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-AziAP

In human α1β2γ2L GABAA receptor expressed in Xenopus oocytes, EC5–10 GABA chloride currents were dramatically potentiated by alphaxalone, F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-aziAP (30-, 17- and 30-fold, respectively) (Figure 2) with EC50 values of 2.2 ± 0.8 μM, 0.5 ± 0.2 μM and 0.2 ± 0.1 μM, respectively.

Figure 2.

F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-aziAP are potent and efficacious positive modulators of GABA-induced currents.

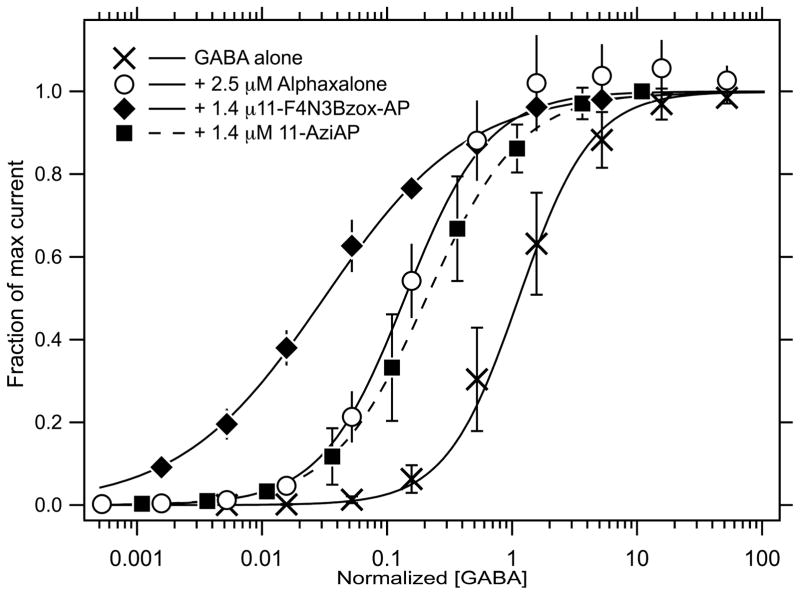

Modulation of the GABA Dose-Response Curves by F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-AziAP

Interactions of α1β3γ2L receptor with alphaxalone, F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-aziAP, resulted in a profound left-shifts of the GABA concentration – response curves consistent with positive allosteric modulation of the agonist site (Figure 3). Thus, the GABA EC50 = 4.5 μM in the absence of the modulator decreased to 0.5 μM in the presence of 2.5 μM alphaxalone, 70 nM in the presence of 1.4 μM F4N3Bzox-AP and 1.23 μM in the presence of 1.4 μM 11-aziAP.

Figure 3.

F4N3Bzox-AP, 11-aziAP and alphaxalone shift the GABA dose-response curve to the left.

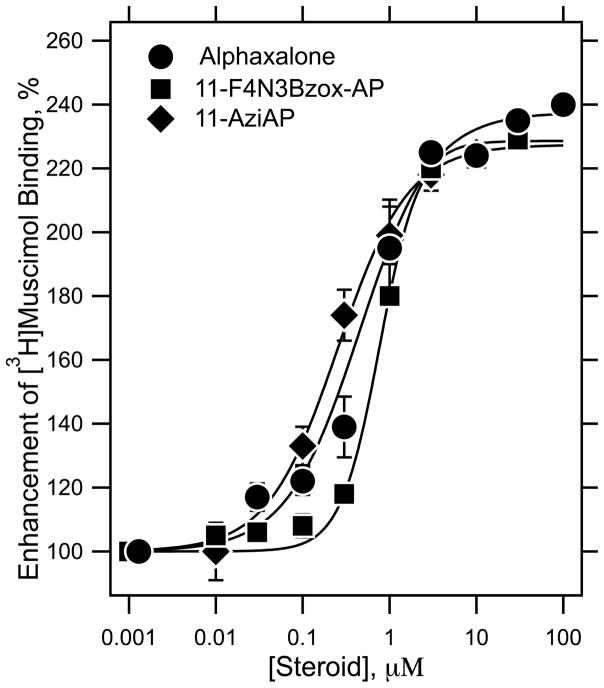

Modulation of Agonist-Binding to GABAA Receptors by F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-AziAP

To further assess the allosteric action, the abilities of alphaxalone, F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-aziAP to modulate the binding of 2 nM [3H]muscimol to α1β3γ2 GABAARs membranes were compared (Figure 4). Displaceable binding of [3H]muscimol was enhanced in a concentration–dependent manner by all three agents between 30 nM and 3 μM, above which it plateaued. The potencies of alphaxalone, F4N3Bzox-AP, and 11-aziAP were comparable with EC50 = 450 ± 62, 770 ± 14, and 250 ± 43 nM, respectively. The Hill coefficients were 1.0 ± 0.1, 1.9 ± 0.1 and 1.1 ± 0.2, respectively. The efficacies of the modulation were comparable at 235 ± 2, 228 ± 4 and 227 ± 2 % for alphaxalone, F4N3Bzox-AP, and 11-aziAP, respectively.

Figure 4.

F4N3Bzox-AP, 11-aziAP and alphaxalone modulate agonist binding to human α1β3γ2 GABAA receptors. The specific binding of 2 nM [3H]muscimol to membrane suspensions of GABAA receptors heterogeneously expressed in HEK293 cells was evaluated as a function of steroid concentration. Each data point was determined in triplicate and is plotted as the mean ± standard deviation.

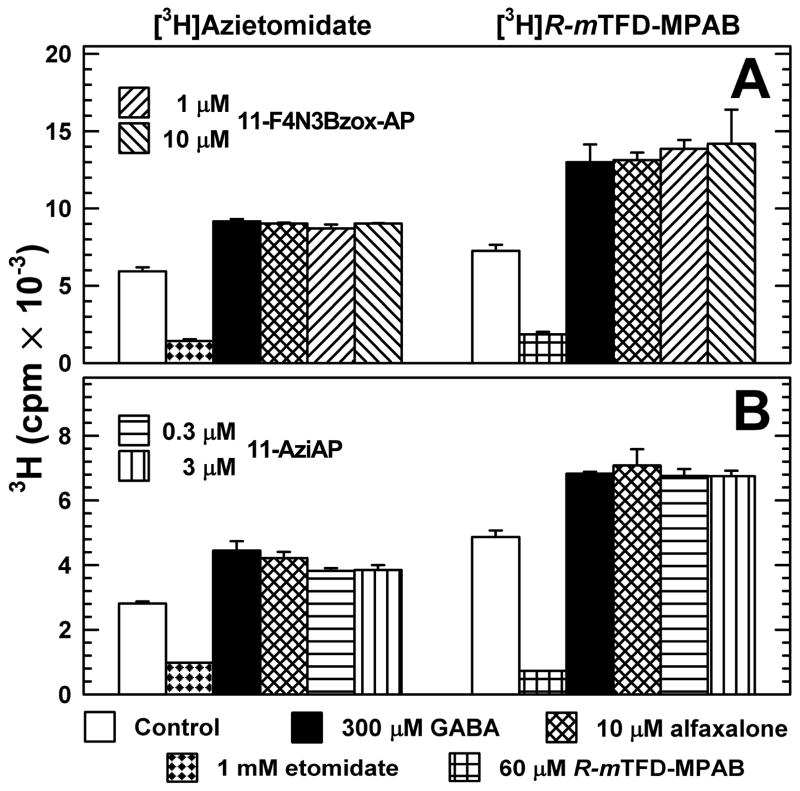

F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-AziAP Enhance [3H]Azietomidate and [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB Photolabeling of Purified Human α1β3γ2 GABAA Receptor

For GABAARs photolabeled in the absence of GABA, F4N3Bzox-AP at 1 or 10 μM enhanced [3H]azietomidate or [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photoincorporation by ~50% and 75%, respectively, i.e. to the same extent as alphaxalone at 30 μM or GABA at 300 μM (Figure 5A), concentrations that produce maximal enhancement of photolabeling.22 Similarly, 11-aziAP at 0.3 and 1 μM enhanced photolabeling by both probes to the same extent as GABA or alphaxalone (Figure 5B). F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-aziAP potentiation of [3H]azietomidate and [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling established that when bound to the GABAAR, it also does not prevent [3H]azietomidate binding in the pocket near the extracellular end of the transmembrane domain between the βM2/βM3 helices and αM2αM1 helices or [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB binding to the homologous pocket between the αM2/αM3 (or γM2/γM3) and βM2/βM1 helices. The enhancement rather than inhibition of photolabeling indicate that the photoreactive steroids bind to sites distinct from either the etomidate or barbiturate site, and that the latter sites interact allosterically with the steroid binding sites.

Figure 5.

11-F4B3Bzox-AP and 11-AziAP potentiate [3H]azietomidate and [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling of α1β3γ2 GABAAR similar to alphaxalone or GABA. Affinity-purified α1β3γ2 GABAA receptors (~ 2 pmol of muscimol sites in 35 μL/lane) were equilibrated with 3 μM [3H]azietomidate or 1 μM [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB in the absence or presence of various drugs. After irradiation, the samples (in duplicate except for etomidate and R-mTFD-MPAB in B) were separated by SDS-PAGE and the stained GABAAR subunits were excised for 3H quantification by liquid scintillation counting. Means and ranges for the duplicate samples are plotted.

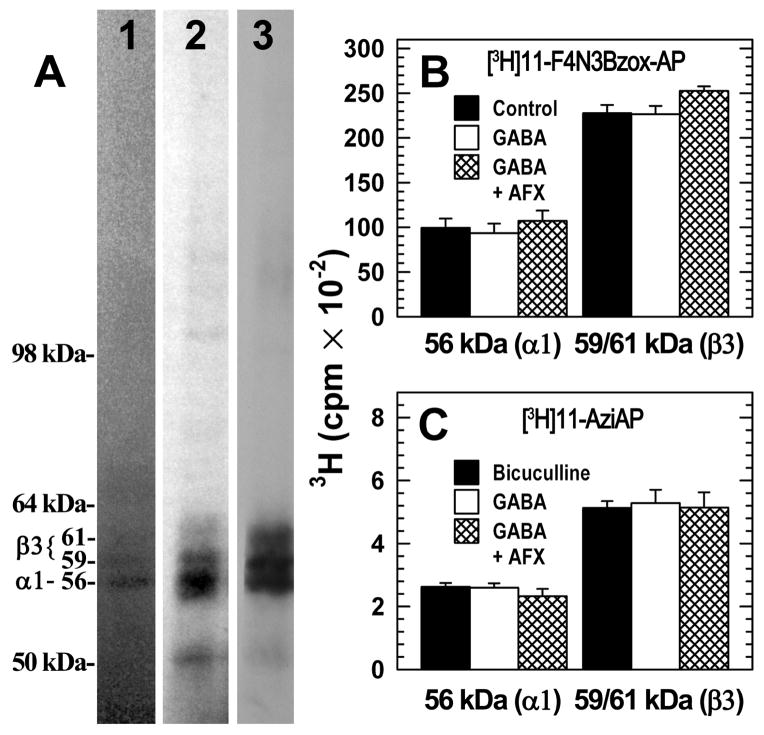

GABAA Receptor Photolabeling by [3H]F4N3Bzox-AP and [3H]11-aziAP

Purified α1β3γ2 GABAARs were photolabeled in the absence of other drugs, or in the presence of bicuculline (100 μM, resting state), GABA (300 μM, desensitized state), or GABA (300 μM) and alphaxalone (30 μM), (Figure 6). Photoincorporation was characterized by SDS-PAGE, with 3H incorporation determined by fluorography (Fig. 6A) or by liquid scintillation counting of excised gel bands containing GABAAR subunits (Figs. 6B and C). Based upon fluorography, [3H]F4N3Bzox-AP and [3H]11-aziAP were each incorporated into the three gel bands revealed by Coomassie Blue stain, a band of 56-kDa, containing by sequence analysis primarily the α1 subunit, and bands of 59- and 61-kDa containing primarily β3 subunits22. The γ2 subunit is broadly distributed in this gel region and present in all three stained bands. Based upon liquid scintillation counting, photoincorporation of either photoreactive steroid at the subunit level in the absence or presence of GABA or bicuculline differed by less than 10%, and in the presence of GABA, alphaxalone altered photolabeling by <10%. Based upon the level of 3H cpm incorporation into the subunits and the pmols of GABAAR loaded on the gel, at 0.7 μM [3H]F4N3Bzox-AP photolabeled ~10% and 6% of β3 and α1 subunits, while [3H]11-aziAP photolabeled ~0.4% and 0.2% of β3 and α1 subunits, respectively. Based upon the α-subunit photolabeling by [3H]azietomidate (Figure 5A) and by [3H]F4N3Bzox-AP (Figure 6B) and the radiochemical specific activities of the ligands, [3H]azietomidate at 3.5 μM and [3H]F4N3Bzox-AP at 0.7 μM photolabeled 10% and 6% of subunits, respectively. This suggests that when photolabeled at the same concentrations, they incorporate with similar efficiency.

Figure 6.

[3H]F4N3Bzox-AP and [3H]11-AziP photolabeling of α1β3γ2 GABAARs. A, Aliquots of α1β3γ2 GABAAR (4 pmol [3H]muscimol sites in 80 μl) were equilibrated with 300 μM GABA and 0.7 μM [3H]11-aziAP (lane 2) or 0.4 μM [3H]F4N3Bzox-AP (lane 3). After irradiation, the aliquots were separated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue (lane 1, a representative lane) and the stained gel was prepared for fluorography, dried, and exposed to X-ray film for 11 days (lane 3) or 42 days (lane 2). Denoted on the left are the mobilities of the molecular mass markers and the Coomassie Blue stained bands that contain GABAAR subunits. B and C, In separate experiments, aliquots of α1β3γ2 GABAAR (3.0 pmol [3H]muscimol sites in 80 μl) were equilibrated with either 0.7 μM [3H]F4N3Bzox-AP (B) or 0.7 μM [3H]11-AziAP (C) in the absence of other drugs or in the presence of 100 μM bicuculline, 300 μM GABA, or 300 μM GABA and 30 μM alphaxalone. After irradiation the aliquots were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the stained gel bands containing α1 and β3 subunits were excised and counted for tritium. The means and standard deviations from 3 ([3H]F4N3Bzox-AP) or 4 ([3H]11-aziAP) parallel samples are plotted. The efficiency of incorporation of [3H]F4N3Bzox-AP was ~20-fold greater than that of [3H]11-AziAP, with no evidence of inhibition by alphaxalone of photolabeling at the subunit level.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In the past decade, binding sites of several allosteric modulators on GABAA receptor have been determined, including those for volatile halogenated ether anesthetics,24–25 propofol,26–27 etomidate28–29 and barbiturates.22,30 Most of these modulators serve as popular clinically used general anesthetics, sedatives or anticonvulsants. Determining the location of the modulator binding sites, and the conformational state of the receptor targeted (open, closed or desensitized), could prove useful to the understanding of the mechanism of allosteric modulation of GABAAR, and ultimately help in development of more efficient and safer GABA-ergic drugs. Despite much therapeutic success with the above listed drugs, the location of the neurosteroid binding site on the heteropentameric GABAAR remains an open question.9,16,17 Both naturally occurring and synthetic neurosteroids, such as pregnanolones and allopregnanolones, are known potent GABAAR modulators,3,4,9,31 and could potentially be used as general anesthetics and anticonvulsants. The mixture of alphaxalone and alfadolone (21-hydroxylated alphaxalone) has been previously used as a general anesthetic, althesin.32 Although it has been withdrawn from the clinic due to potentially fatal side effects, these side effects have been later attributed to the solubilizing lipid excipient used in the drug formulation,6 rather than the pharmacologically active constituent. Another neurosteroid, ganaxalone (3-methyl-allopregnanolone), is in phase 3 clinical studies as an antiepileptic.33,34 Given the potential broad clinical applications of neurosteroids and their different type of structure as compared to other GABAAR ligands, determining the binding site of neurosteroids and understanding their mode of action remains an important biomedical goal.

As with other general anesthetics, our approach toward this objective has been to synthesize photoreactive analogs of alphaxalone, compare their pharmacological properties with those of the parent anesthetic, and if they bear close resemblance, to photolabel the receptor and determine the site of the probe’s photoincorporation. Similar efforts have been previously carried out by others, whereby photoactivatable pregnanolones and allopregnanolones have been used in an analogous fashion, most notably, 6-azipregnanolone 315 and 11-[4-(TFD-benzyloxy]pregnanolone 4 (and its corresponding allo-isomer 5).17 Compound 3 was found to photoincorporate into Phe301 in the third transmembrane domain (M3) of the β3-homomeric receptor.16 This area would constitute a novel modulator binding site located closer to the cytoplasmic face of the membrane, as compared to the other known intersubunit binding sites for general anesthetics that are located closer to the extracellular domain.22,27 However, these workers did not establish the pharmacological specificity of the photolabeling at Phe301, so this interpretation should be regarded with caution. On the other hand, compounds 4 and 5 were found to replicate pharmacology of their parent compounds, and to photolabel GABA receptors in rat brain membranes, however their subunit specificities and the sites of photoincorporation were not determined.17

In our work, we also chose to modify the position-11 of alphaxalone to synthesize photoreactive anesthetics incorporating either a bulky azidotetrafluorophenyl residue, which produces a photoreactive nitrene, or a smaller diazirine, similar to the photoreactive group in azietomidate. Structure-activity studies of naturally and unnaturally configurated neurosteroid analogs12 suggest that neurosteroids featuring a natural stereochemical structure interact with the GABAA receptor using the lower edge of their steroid framework,12 thereby permitting large scale structural modifications to the upper edge. An uncertainty related to this mode of receptor – modulator interaction was that if correct, a photoreactive group linked to the upper edge might be exposed to interactions with membrane lipids, and hence would not be an efficient protein photolabel, but instead would predominantly modify the membrane lipids.

F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-aziAP Display Pharmacological Properties Similar to Alphaxalone

This work involves extensive pharmacological characterization of the F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-aziAP photoprobes. In all assays performed, F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-aziAP closely reproduced the pharmacology of the parent compound, alphaxalone, except in most assays they were more potent (Figures 2–4). Thus, they were more potent general anesthetics than alphaxalone in the LORR assay; they were also strong and efficacious positive allosteric modulators of the heteropentameric α1β3γ2 GABAAR in oocytes, potentiating the ion currents 17- and 30-fold, respectively. Likewise, both left-shifted the GABA dose-response curve, and modulated the binding of agonist muscimol by GABAAR similarly to alphaxalone.

Neurosteroid Site Is Distinct From Those of Either Etomidate or Barbiturate

Similar to alphaxalone,22 F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-aziAP each enhanced photolabeling by the two site-selective photoprobes, [3H]azietomidate and [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB (Figure 5). This result indicates that these steroid anesthetics do not compete for the binding to the intersubunit sites we recently located at the extracellular end of the transmembrane domain at the β+–α− (etomidate28) and at the α+– β− and γ+–β− subunit interfaces (barbiturate).22 This result is also consistent with the earlier ones showing an enhancement of anesthetic potency of etomidate by neurosteroids35 and of chromaffin cell‘s responses to natural neurosteroids in the presence of a variety of barbiturates.36 Our results confirm that these sites (etomidate, barbiturate and neurosteroid) are nonidentical, but their occupancies are allosterically coupled.22

Photolabeling of the GABAA Receptor by F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-AziAP

[3H]F4N3Bzox-AP photoincorporated into the GABAA receptor α and β subunits at an efficiency similar to that seen for [3H]azietomidate. The major difference between the photoprobes is that 80% of [3H]azietomidate subunit photolabeling was pharmacologically specific, i.e. inhibitable by etomidate, while alphaxalone at 30 μM did not inhibit [3H]F4N3Bzox-AP photolabeling at the subunit level. [3H]11-AziAP also photoincorporated into GABAAR α and β subunits, but at only ~5% the efficiency of [3H]F4N3Bzoxy-AP, and also with no inhibition by 30 μM alphaxalone.

Possible modes of interactions of F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-aziAP with GABAAR

Both F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-aziAP are potent allosteric effectors of GABAA receptors whose binding site is distinct from, but allosterically coupled to, those of both etomidate and R-mTFD-MPAB. The fact that a large substitution at the 11-position of the steroid framework does not compromise its interactions with the GABA receptor is consistent with the established SAR.10–14 Nonetheless, the observed photolabeling was not pharmacologically specific. The simplest explanation for these observations is that both F4N3Bzox-AP and 11-aziAP bind with the photoreactive moieties oriented away from the binding site as suggested by Krishnan et al.12 Inspection of Figure 1 shows that in F4N3Bzox-AP, the photoactive moiety has extremely limited mobility relative to the rigid steroid backbone. Thus, if the latter is tightly bound in certain orientations, the photoactivated group would be incapable of photoincorporation. This is consistent with the suggestion that such agents bind with the upper edge pointing out of the binding site.12

If the above hypothesis is correct, the GABAA receptor photolabeling we observed must result primarily from nonspecific interactions. The high lipophilicity of neuroactive steroids in general, including our new photoprobes, as well as compounds 3–5, means that the lipid phase magnifies the concentration of the ligand.31 For example, alphaxalone, with a partition coefficient of log P = 3.1,31 reaches a near millimolar concentration in the membrane at bulk phase concentrations close to the potentiation EC50 (0.6 μM).9,31 Due to even higher lipophilicity of F4N3Bzox-AP (by ca. 1.5 log P units as compared to alphaxalone), its membrane concentration is likely even higher. At such high concentration of ligand in proximity to the receptor, nonspecific photolabeling is probably unavoidable, and it is possible that a pharmacologically specific (inhibitable) portion of the overall (specific plus nonspecific) photolabeling is too small to be discerned at the subunit level, but perhaps could be detected at the amino acid level. For example, the hydrophobic photoprobe [3H]diazofluorane appeared to photolabel the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) in a pharmacologically non-specific manner at the subunit level, whereas state-dependent, pharmacologically specific photolabeling was identified at the amino acid level within the ion channel by sequence analysis of appropriate subunit fragments.37 However, preliminary results from sequencing GABAA receptors photolabeled with F4N3Bzox-AP, have not yet revealed such sites.38

We cannot rule out that our results are consistent with the hypothesis developed by Akk et al.31 that in spite of submicromolar potencies of neurosteroid anesthetics, specific binding of these ligands to the receptor protein occurs with much lower, possibly millimolar, intrinsic affinity for the GABAAR because, as noted above, the actual concentration at the lipid-receptor interface is millimolar.31

Development of the additional neurosteroid photoprobes proposed in the introduction will be required to resolve these issues in a more definitive manner. The known structure–activity relationships suggest it may be difficult to achieve high potency with substitutions larger than the diazirine residue. The limitation of aliphatic diazirines is that they photolabel only a limited number of amino acids bearing nucleophilic side chains. In any event, it may be advantageous for such agents to have lower membrane partition coefficients to decrease their membrane concentration and to have smaller photoreactive residues located closer to the steroid backbone or other positions of the steroid scaffold to enhance the chance of photoincorporation into the binding site and to limit potential lipid photolabeling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Analytical Chemistry

1H, 13C and 19F NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker Avance spectrometer at 400 MHz, 100 MHz and 376 MHz, respectively, unless otherwise noted. NMR chemicals shifts were referenced indirectly to TMS for 1H and 13C, and CFCl3 for 19F NMR. HRMS experiments were performed with Q-TOF-2TM (Micromass). TLC was performed with Merck 60 F254 silica gel plates. Purity of the final compounds was assessed by HPLC analysis with a Synergy Hydro-RP column (4 μm, 4.60 × 150 mm) using methanol-water with 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid; the gradient applied was from 50% MeOH at the start to 100% MeOH over 18 min, followed by isocratic elution. Elution was monitored by UV at 254 nm. The analysis indicated purity greater than 96%. Preparative Shimadzu LC-20 HPLC system was used for all preparative and analytical separations, unless otherwise stated.

Materials

11α-Hydroxyprogesterone was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Anhydrous grade solvents were from Aldrich, and were not further dried or purified. [3H]F4N3Bzox-AP (45 Ci/mmol) and [3H]-11-aziAP (40 Ci/mmol) were synthesized by ViTrax Company (Placentia, CA) by tritiation of compounds 15 and 25, respectively, using the procedure described below. [3H]Azietomidate (12 Ci/mmol) and [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB (38 Ci/mmol) were prepared as described.30,40 Human α1β3γ2 GABAARs with a FLAG epitope on the N-terminus of the α1 subunit was purified as described41 on an anti-FLAG antibody column from detergent extracts of membrane fractions from a tetracycline-inducible HEK293S cell line. GABAAR was eluted from the column with 0.1 mM FLAG peptide in elution buffer containing 5 mM CHAPS, 0.2 mM asolectin and then stored at −80°C until use.

Determination of the x-ray structures of compound 15 and 23

A crystal measuring roughly 10 × 10 × 30 μm was selected for data collection. It was encased in silicon oil, drawn into a nylon loop, and cooled to 100 K. Data collection was carried out at beam line 21-ID-D, LS-CAT, Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory, using a MAR 300mm CCD detector, with a wavelength of 0.72849 Å and a crystal-to-detector distance of 95 mm; 180 images were collected, each from a 2° rotation with an exposure of 1 s. Integration of the data with XDS resulted in a total of 67,769 reflections, and an average of 6090 unique reflections to a resolution of 0.76 Å. The unit cell was identified as hexagonal, and subsequent analysis led to the selection of the space group as P62 (No. 171) or P64 (No. 172). The structure was solved with SHELXS, and refined with SHELXL-2013. All hydrogen atoms were evident in the difference electron density map, and placed in calculated positions; hydrogen atoms on the methyl and hydroxyl groups were restrained to ride on the adjacent atom at fixed bond lengths. The inverted structure was also refined, and resulted in the selection of space group as P64 (No. 172). A water molecule is present in the structure along the c-axis, and the hydrogen atoms were not evident in the electron density difference map. Since the water could not be adequately modeled, it was removed from the refinement model. After convergence, SQUEEZE was run to modify the structure factors. Thus, we assign a water molecule to this structure, at half occupancy along the c-axis, but it is not included in the final reported model. There is substantial libration with the fluoroaromatic ring, and the fluorine atoms were modeled as single atoms with large librational motion perpendicular to the plane of the aromatic ring. We were unable to determine the absolute configuration of the structure with this data. The final agreement is good, with RF(all) = 0.0819, RF(2σ) = 0.0795, Rw(all) = 0.2071, goodness-of-fit = 1.046.

Electrophysiology of GABAA Receptors

With prior approval by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care, oocytes were obtained from adult, female Xenopus laevis (Xenopus One, Dextor, Michigan) and prepared using standard methods as described below. In vitro transcription from linearized cDNA templates and purification of subunit specific cRNAs was carried out using Ambion mMessage Machine RNA kits and spin columns. Oocytes were injected with ~100 ng total mRNA (α1, β2, γ2L) mixed at a ratio of 1:1:2 transcribed from human GABA receptor subunit cDNAs in pCDNA3.1.42 All two-electrode voltage clamp experiments were done at room temperature, with the oocyte transmembrane potential clamped at −50 mV and with continuous oocyte perfusion with ND96 (100 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5) at ~2 mL/min. Barbiturate stock solutions were prepared in DMSO at a concentration of 100 mM for storage at −20°C. Compounds were further diluted in ND96 to achieve the desired concentration (the highest final DMSO concentration was 1%). All agents were applied for 15–25 s; oocytes were washed ~3 min between each application. Currents were amplified using an Oocyte Clamp OC-725C amplifier (Warner Instrument Corp), digitized using a Digidata 1322A (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA), and analyzed using Clampex/Clampfit 8.2 (Axon Instruments) and OriginPro 6.1 software.

Concentration response data were fit by nonlinear least squares regression to the Hill (logistic) equation (1) of the general form:

| (1) |

where X is the concentration of the activating ligand, IGABA,max is the maximally evoked current, EC50 is the concentration of X eliciting half of its maximal effect, and nH is the Hill coefficient of activation. Inhibition experiments were fit with logistic equations of the form:

| (2) |

Allosteric regulation of agonist binding to GABAA receptors

Human α1β3γ2 GABAA receptors were expressed in HEK293 TetR cells. Homogenized cell membranes were prepared as described previously,40 and 200 μg of α1β3γ2 GABAA receptor membrane protein was resuspended in 500 μL of assay buffer (10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 200 mM KCl, and 1 mM EDTA). The suspension was equilibrated with 2 nM [3H]muscimol and various concentrations of steroid at 4°C for 1 h. The nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 1 mM GABA. The suspension was filtered on GF/B glass fiber filters (Whatman, Schleicher & Schuell, Maidstone, U.K.) that were pretreated in 0.5% w/v polyethyleneimine for 1 h. After receptor application, filters were washed under vacuum with 7 mL of cold assay buffer and dried under a lamp for 30 min. Subsequently, they were equilibrated in Liquiscint (Atlanta, GA) and counted (Tri-Carb 1900, liquid scintillation analyzer, Perkin-Elmer/Packard, Waltham, MA).

Photolabeling α1β3γ2 GABAARs

Aliquots of purified GABAAR in elution buffer were photolabeled on an analytical scale (35–75 μL/aliquot containing ~3 pmol [3H]muscimol binding sites) to determine subunit photoincorporation and the effects of non-radioactive anesthetics on photolabeling. An appropriate volume of a tritiated, photoreactive anesthetic solution in methanol was transferred into a glass tube. After solvent was evaporated to near dryness under a stream of argon gas, freshly thawed GABAAR in elution buffer was added to the tube, and the radioligand was resuspended at 4°C by gentle agitation for 30 min to final concentrations of 0.4 – 0.7 μM [3H]F4N3-alphaxalone or [3H]11-aziAP, 3 μM [3H]azietomidate, or 1 μM [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB. Aliquots were then transferred to glass vials, and appropriate amounts of non-radioactive drugs were added using a 1 μl glass syringe (Hamilton #7101) from stock solutions prepared in methanol such that the final methanol concentration was ≤ 0.5% (v/v). After another 30 min incubation (4 °C), the samples were transferred to the wells of plastic microtiter plates and irradiated on ice for 30 min at 365 nm with a Spectroline model EN-280L lamp at a distance of < 1 cm. After photolysis, GABAAR subunits were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and 3H incorporation into GABAAR subunits was determined by liquid scintillation counting or fluorography as described.22

20-Ethylenedioxy-11α-hydroxy-pregn-4-ene-3-one (9)

A suspension of finely powdered 11α-hydroxyprogesterone (8, 2.00 g, 6.06 mmol) in dry ethylene glycol (50 mL) was vigorously stirred for 30 min at room temperature and pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (0.80, 1.58 mmol) was added at once, followed by trimethyl orthoformate (1.0 mL, 9.14 mmol). The reaction mixture was left stirred at room temperature for 48 h (control – TLC in ethyl acetate – hexane, 7:3). The reaction mixture was neutralized with saturated solution of sodium bicarbonate (10 mL), the newly formed precipitate was filtered off and washed with water (2×10 mL), dried on air and recrystallized from the mixture of methanol and triethylamine (100:1), filtered, washed with small amount of MeOH (2 × 1 mL) and dried on air to give a white solid (1.023 g, 45%). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 5.73 (s, 1H, -CH=), 4.07 – 3.83 (m, 5H, OCH2CH2O + 11α-CH), 2.67 (dt, 1H, J = 13.8 Hz, 6.4 Hz), 2.50 – 2.22 (m, 5H), 2.01 (td, 1H, J = 13.8 Hz, 4.5 Hz), 1.90 – 1.70 (m, 4H), 1.70 – 1.60 (m, 1H), 1.60 – 1.44 (m, 1H), 1.32 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.30 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.28 -1.00 (m, 5H), 0.84 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 200.2, 171.3, 124.4, 111.5, 68.9, 65.1, 63.2, 59.2, 57.8, 55.1, 51.4, 42.6, 39.9, 37.5, 34.5, 34.2, 33.7, 24.5, 23.6, 23.0, 18.3, 14.2. HR MS: predicted for C23H33O4 [M−H]+: 373.2379; found 373.24.

11α-Hydroxy-20-ethylenedioxy-5α-pregnane-3-one (10).18

A mixture of freshly distilled ammonia (50 mL), dry toluene (20 mL) and absolute THF (5mL) was cooled to −78°C under argon with stirring. Lithium metal (50 mg, 7.2 mmol) was added at once and stirring continued until full dissolution of the metal (~ 1 hour at −78°C). The ketal 9 (1.00 g, 2.67 mmol) was dissolved in boiling toluene (10 mL) under the stream of argon, cooled with stirring and redissolved in dry THF (10 mL). The resulted solution was added dropwise over 5 min into vigorously stirred Li-NH3-THF-toluene mixture at −78°C. After one hour, the reaction mixture was quenched by addition of solid NH4Cl (5 g, stirred at −78°C until the disappearance of the blue color) and left to warm up to room temperature overnight while the ammonia gas evaporated. The resulting mixture was partitioned between ethyl acetate and water (50 mL ea.), the organic phase was washed with brine and water (20 mL ea.), dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated under vacuum. Chromatography on silica gel in ethyl acetate – hexane (1:1, 0.2% of triethylamine) afforded saturated hydroxyketone 10 as a slowly crystallizing white solid (734 mg, 73%). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 4.06 – 3.83 (m, 5H), 2.78 (ddd, J = 13.8 Hz, 6.4 Hz, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 2.48 – 2.24 (m, 4H), 2.10 (ddd, J = 15.0, ~4.1 Hz, 2.4 Hz), 1.85 (dd, J = 10.7 Hz, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 1.81 – 1.48 (m, 6H), 1.48 – 1.30 (m, 3H), 1.30 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.27 – 1.07 (m, 2H), 1.15 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.04 – 0.91 (m, 2H), 0.89 – 0.80 (m, 1H), 0.81 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 212.1, 111.6, 69.0, 65.1, 63.2, 60.0, 58.0, 55.4, 51.6, 47.4, 45.2, 42.5, 40.2, 38.4, 37.2, 34.1, 31.5, 29.4, 24.5, 23.8, 23.0, 14.1, 11.8. HR MS: predicted for C23H37O4 [M+H]+: 377.2692; found 377.2694.

20-Ethylenedioxy-5α-pregnane-3,11-dione (11)

A suspension of CrO3 (2.00 g, 20 mmol) in dry dichloromethane (10 mL) was cooled with stirring to −20°C under argon, and dry pyridine (5 mL, 63 mmol) was added dropwise with vigorous stirring. The resulted dark suspension was stirred 30 min at −20°C, then 30 min at 0°C, and the solution of hydroxyketone 10 (700 mg, 1.86 mmol) in DCM (5 mL) was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h on ice bath and 2 h at 20°C. The mixture was cooled to −10°C and quenched with a mixture of ice and saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (5 mL each). The resulted heavy and dark suspension was stirred for 5 h with the mixture of ethyl acetate, aqueous NaHCO3 (20 mL ea.) and EDTA (6 g, ~20 mmol). The layers were separated, the aqueous phase was extracted with ethyl acetate (2×20 mL), the combined organic phases were washed with water (2×20 mL), brine (10 mL) and dried over Na2SO4. Chromatography on silica gel (eluent hexane – ethyl acetate 4:1 + 0.1% NEt3) afforded pure 3,11-dione 11 as colorless needles (571 mg, 82%). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 4.05 – 3.83 (m, 4H, OCH2CH2O), 2.80 (ddd, J = 13.1 Hz, 6.4 Hz, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 2.64 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 2.46 (td, J = 14.8 Hz, 6.5 Hz), 2.35 – 2.20 (m, 3H), 2.15 – 1.97 (m, 2H), 1.95 – 1.60 (m, 7H), 1.55 – 1.42 (m, 1H), 1.41 – 1.30 (m, 2H), 1.26 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.22 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.25 – 1.05 (m, 1H), 0.75 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 211.5, 211.0, 111.2, 64.8, 63.7, 63.2, 57.7, 56.8, 55.3, 47.0, 46.0, 44.3, 38.0, 37.1, 36.3, 35.1, 32.2, 28.3, 24.3, 23.5, 23.4, 14.6, 11.1. HR MS: predicted for C23H35O4 [M+H]+: 375.2535; found: 375.2525.

3α-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyloxy)-20-ethylenedioxy-5α-pregnane-11-one (12)

Regio- and stereo-selective reduction of 3,11-diketone 11 (555 mg, 1.48 mmol) at the 3 position with Selectride-K in THF at −78°C was performed as described previously,18 except urea – hydrogen peroxide complex was used instead of pure aqueous H2O2. The crude 3α-alcohol from the previous step (yield was nearly quantitative) was stirred with the solution of TBDMSCl (452 mg, 3.00 mmol), imidazole (408 mg, 6.00 mmol) in DMF (2 mL) for 2 days at room temperature. A usual work-up and chromatography on silica gel (eluent hexane – ethyl acetate, 9:1 + 0.1% NEt3) afforded 3α-silyloxyketone 12 as colorless crystals (559 mg, 77% in two stages). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 4.03 - 3.83 (m, 5H), 2.59 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 2.29 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 2.15 (dt, J = 12.7, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 2.04 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 1.91 – 1.65 (m, 7H), 1.65 – 1.50 (m, 1H), 1.50 – 1.38 (m, 1H), 1.32 -1.12 (m, 6H), 1.25 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.00 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.90 (s, 9H, tert-Bu), 0.73 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.03 (s, 6H, Si-CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 211.7, 111.3, 66.7, 64.9, 64.4, 63.2, 57.9, 57.0, 55.6, 46.0, 39.0, 36.4, 36.4, 35.6, 32.7, 31.1, 29.5, 28.1, 25.9, 24.3, 23.5, 23.3, 18.1, 14.1, 11.1, −4.8, −4.9. HR MS: predicted for C29H51O4Si [M+H]+: 491.3557; found: 491.3548.

3α-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyloxy)-20-ethylenedioxy-11β-hydroxy-5α-pregnane (13)

A solution of silyloxyketone 12 (530 mg, 1.08 mmol) in absolute ether (10 mL) under argon was stirred with lithium aluminium hydride (40 mg, 1.05 mmol). After two hours, the reaction mixture was cooled to −78°C, quenched with acetone (1 mL), and added with 10% aq. NH4Cl (5 mL) and EDTA-sodium hydroxide buffer with pH 7 (~10% EDTA, 10 mL). The resulted suspension was left stirred while warming up and partitioned between ethyl acetate (50 mL) and water (20 mL). An extraction and chromatography (eluent hexane – ethyl acetate 9:1 to 4:1) afforded pure 11β-hydroxysteroid 13 as colorless crystals (392 mg, 74%). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 4.34 -4.28 (m, 1H, 11α-CH), 4.04 - 3.83 (m, 4H, OCH2CH2O + 3β-CH), 2.21 (dd, J = 14.1, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 1.84 – 1.62 (m, 6H), 1.62 – 1.38 (m, 7H), 1.31 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.27 – 1.10 (m, 4H), 1.10 – 0.95 (m, 2H), 1.02 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.99 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.90 (s, 9H, tert-Bu), 0.80 (d, J = 7.0, 3.0 Hz), 0.03 (s, 6H, Si-CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 111.9, 68.4, 66.7, 65.0, 63.2, 58.7, 58.2, 57.9, 48.4, 41.3, 39.9, 36.2, 36.1, 32.3, 32.1, 30.7, 29.4, 28.1, 25.9, 24.5, 23.7, 22.7, 15.8, 14.6, −4.9.

3α-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyloxy)-20-ethylenedioxy-11β-(pentafluorobenzoyloxy)-5α-pregnane (14)

A solution of 11β-hydroxysteroid 13 (190 mg, 0.385 mmol) in anhydrous THF (5 mL) under argon was cooled with stirring to −78°C, and butyllithium (0.29 mL, 1.6 M in hexane) was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred for additional 10 min, and pentafluorobenzoyl chloride (0.067 mL, 0.46 mmol) was added dropwise, followed by N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.1 mL, 0.57 mmol). After an overnight stirring, a usual work-up and chromatography (hexane – ethyl acetate 24:1), the pentafluorobenzoyl derivative 14 was crystallized from methanol (190 mg, 72%). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 5.71 (q, J =2.5 Hz, 1H, 11α-CH), 4.04 - 3.80 (m, 5H, OCH2CH2O + 3β-CH), 2.47 (dd, J = 14.9, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 1.86 – 1.65 (m, 6H), 1.62 – 1.45 (m, 6H), 1.45 -1.32 (m, 2H), 1.28 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.27 – 1.05 (m, ~8H), 1.02 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.90 (s, 9H, tert-Bu), 0.87 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.81 (d, J = 7.0, 3.0 Hz), 0.03 (s, 6H, Si-CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 158.7, 144.5 (dm, J ~ 255.8 Hz), 142.7 (dm, J ~ 258.7 Hz), 137.6 (dm, J ~ 250.7 Hz), 111.6, 74.2, 66.5, 65.0, 63.2, 58.5, 57.4, 57.0, 44.5, 41.0, 40.2, 36.2, 35.8, 32.2, 32.1, 31.4, 29.7, 29.2, 27.8, 25.9, 24.5, 23.6, 22.7, 18.1, 14.8, 13.9, −4.9. 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ -138.6 (m, 2F, o-CF), −149.9 (tt, J = 17.5, 3.3 Hz, 1F, p-CF), −160.2 (m, 2F, m-CF). HR MS: predicted for C36H52O5F5Si [M+H]+: 687.3504; found: 687.3530.

3α-Hydroxy-11β-(pentafluorobenzoyloxy)-pregnane-20-one (15) and 3α-(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)-11β-(pentafluorobenzoyloxy)-pregnane-20-one (15a)

A stirred solution of silyloxy-ketal 14 (168 mg, 0.245 mmol) in the MeOH-DCM mixture (2:1, 3 mL) was treated with 0.5 M solution of hydrogen chloride in methanol at room temperature. After 1h (control – TLC), the reaction mixture was divided between aq. NaHCO3 and ethyl acetate (10 mL each). Organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under vacuum. Chromatography on silica gel afforded hydroxyketone 15 (36 mg, 28%) and silyloxy-ketone 15a (110 mg, 70%) as colorless crystalline solids.

15

1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 5.78 (q, J =2.6 Hz, 1H, 11α-CH) 4.06 (s, 1H, 3β-CH3), 2.51 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 2.46 (dd, J = 14.5, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 2.25 – 2.12 (m, 1H), 2.12 (s, 3H, COCH3), 1.90 – 1.35 (m, 14H), 1.35 -1.26 (m, 6H), 1.13 (dd, J = 10.9, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 1.08 – 0.95 (m, 1H), 0.82 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.73 (s, 3H, CH3). 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ -138.2 (m, 2F, o-CF), −149.1 (tt, J = 21.0, 3.2 Hz, 1F, p-CF), −160.0 (m, 2F, m-CF). HR MS: calculated for C28H33O4F5Na [M+Na]+: 551.2197; found: 551.2202.

15a

1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 5.77 (q, J =2.8 Hz, 1H, 11α-CH) 3.96 (s, 1H, 3β-CH3), 2.51 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 2.45 (dd, J = 14.4, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 2.25 – 2.12 (m, 1H), 2.12 (s, 3H, COCH3), 1.90 – 1.72 (m, 4H), 1.72 -1.45 (m, 6H), 1.45 – 0.98 (m, 11H), 1.28 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.27 – 1.05 (m, ~8H), 0.90 (s, 9H, tert-Bu), 0.80 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.74 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.04 (s, 3H, Si-CH3), 0.03 (s, 3H, Si-CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 208.7 (COMe), 66.4, 63.8, 57.7, 57.0, 43.9, 42.8, 40.2, 36.1, 35.9, 32.3, 32.2, 31.8, 31.3, 29.1, 27.7, 25.9, 24.2, 22.5, 22.3, 18.1, 15.1, 14.0, −4.9 (Si-CH3). 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ -138.2 (m, 2F, o-CF), −149.1 (tt, J = 21.0, 3.2 Hz, 1F, p-CF), −160.0 (m, 2F, m-CF). HR MS: calculated for C34H47F5NaO4Si [M+Na]+: 665.3061; found: 665.3068.

11β-(4-Azido-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorobenzoyloxy)-3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnane-20-one (6)

A solution of an azidation reagent was prepared by dissolving tetra-n-butylammonium azide (10 mg, 0.035 mmol) and trimethylsilyl azide (0.05 mL, 0.37 mmol) in dry deuterated acetone. A solution of pentafluorobenzoyloxy derivative 15 (35.3 mg, 0.0668 mmol) in dry deuterated acetone (0.6 mL), was mixed with 0.05 mL of the reagent solution at room temperature. After 1h, 19F NMR showed a complete and clean conversion of pentafluorobenzoyl derivative into the 4-azido-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorobenzoyl derivative. The reaction mixture was diluted with methanol, evaporated in the stream of air, dissolved in methanol – ethyl acetate mixture (1 mL ea.) and treated with methanolic HCl (0.1 mL, 0.5M). After 1 h at room temperature, the reaction mixture was divided between ethyl acetate (10 mL) and water (5 mL), washed with brine and water (5 ml ea.), dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated under vacuum. Chromatography on silica gel in ethyl acetate – hexane 2:3 to 1:1 v/v afforded pure target steroid 6 as white colorless solid (35.2 mg, 96%).

6

1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 5.77 (q, J =2.7 Hz, 1H, 11α-CH) 4.06 (s, 1H, 3β-CH3), 2.51 (t, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 2.45 (dd, J = 14.5, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 2.25 – 2.12 (m, 1H), 2.12 (s, 3H, COCH3), 1.93 – 1.15 (m, 24H), 1.12 (dd, J = 11.0, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 1.08 – 0.96 (m, 1H), 0.82 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.74 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 208.6, 159.0, 144.9 (d, J = ~252 Hz), 140.6 (d, J = ~251 Hz), 72.9, 66.1, 63.8, 57.9, 57.0, 44.0, 42.8, 40.1, 36.0, 35.2, 32.2, 32.0, 31.8, 31.3, 28.6, 27.6, 27.0, 24.2, 22.5, 15.1, 13.7. 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ -138.4 (m, 2F), −150.5 (m, 2F). HR MS: calculated for C28H33F4N3NaO4 [M+Na]+: 574.2305; found: 574.2308.

3α-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyloxy)-11β-(pentafluorobenzoyloxy)-17-phenylselenyl-pregnane (16) and 3α-Hydroxy-11β-(pentafluorobenzoyloxy)-pregn-17-ene (17).39

The solution of the silyl ether 15a (114 mg, 0.177 mmol) in dry pentane (5 mL) under argon was cooled with stirring to −25°C. Hexamethyldisilazane (44 μL, 0.212 mmol) was added at once, followed by trimethylsilyl iodide (28 μL, 0.195 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at −20°C for 30 min, then left to warm up overnight. The mixture was cooled with stirring to −25°C and quenched with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (1 mL), left to warm up to room temperature, and stirred with water (1 mL) until full dissolution of solids (~30 min). This mixture was cooled to −30°C, the organic layer was decanted, solid layer was washed with pentane (2×1 mL), the combined organic phases were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in the stream of argon. The resulted colorless oil was dissolved in absolute THF and cooled with stirring under argon to −78°C, and dry pyridine (20 μL, 0.25 mmol) was added, followed by a solution of phenylselenyl chloride (40.6 mg, 0.212 mmol) in THF (0.5 mL). The mixture was stirred for 30 min at −78°C and quenched with addition of aqueous HCl (1 M, 1 mL) and ethyl acetate (5 mL). The reaction mixture was allowed to warm up to room temperature, phases were separated, organic layer was washed with water (2×2 mL) and dried over Na2SO4. The resulted crude solution was stirred with a mixture of pyridine (25 μL, 0.31 mmol), urea-hydrogen peroxide complex (150 mg, 1.6 mmol) and water (2 drops) on ice bath. After 1 h, the resulted mixture was partitioned between ethyl acetate (10 mL) and water (5 mL). The organic layer was washed with water and brine (5 mL each), dried and evaporated under vacuum. Chromatography on silica gel (eluent hexane – ethyl acetate 30:1 to 24:1) afforded crystalline phenylselenyl derivative 16, starting material 14, and the unsaturated product 17. The recovered phenyl selenide 16 was dissolved in THF (1 mL) and stirred with pyridine (20 μL), urea-hydrogen peroxide (100 mg) and water (3 drops) on ice bath for 2 hours. After similar work-up and chromatography, the desired unsaturated steroid 17 was isolated as a colorless solid (24.3 mg, 21% from 15a, 81% from the phenyl selenide 16).

16

1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.50 – 7.25 (m, 5H, Ph), 5.84 (s, 1H, 11α-CH), 3.98 (s, 1H, 3β-CH3), 2.55 – 2.40 (m, 1H), 2.43 (s, 3H, COCH3), 2.38 – 2.18 (m, 2H), 1.95 – 1.05 (m, 17H), 0.98 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.94 (s, 9H, tert-Bu) 0.74 (s, 3H, CH3). 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ -138.4 (m, 2F), −149.0 (t, J = 21.0 Hz, 1F), −159.8 (m, 2F). HR MS: calculated for C40H52F5O4SeSi [M+H]+: 799.2720; found: 799.2723.

17

1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 6.71 (q, J = ~1.5 Hz, 1H, -CH=), 5.77 (unres. q, J =2.0 Hz, 1H, 11α-CH), 4.06 (q, 1H, 3β-CH3), 2.79 (dd, J = 15.1, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 2.40 (ddd, J = 17.0, 6.6, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 2.26 (s, 3H, COCH3), 2.17 – 1.97 (m, 2H), 1.92 – 1.83 (m, 1H), 1.74 – 1.36 (m, 9H), 1.36 -1.20 (m, 8H), 1.16 (dd, J = 11.1, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 1.06 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.93 – 0.86 (m, 3H), 0.85 (s, 3H, CH3). 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ -138.2 (m, 2F), −149.4 (t, J =~21.0 Hz, 1F), −160.1 (m, 2F). HR MS: calculated for C28H31F5NaO4 [M+Na]+: 549.2040; found: 549.2046.

Conversion of alkene 17 into F4N3Bzox-AP (6)

The alkene 17 was hydrogenated (tritiated) using hydrogen (tritium) gas under atmospheric pressure over 10% Pd/C in ethyl acetate. The catalyst was filtered off, the solution concentrated, the residue dissolved in a minimal amount of DMSO and treated with ~ 1% tetra-n-butylammonium azide in DMSO for 1 minute. The product was isolated by extraction with ethyl acetate and purified by chromatography on silica gel using ethyl acetate - hexane 1:1 for elution or by HPLC. The tritiated compound was purified by HPLC using Eclipse XDB-C18 3.5 μm, 4.6–150 mm column and linear gradient of acetonitrile in isocratic 0.05% TFA-H2O for elution (60% at t=0, 90% at t=10 min) with 1.0 mL/min flow rate. The identity of the tritiated product was verified by MS and by HPLC co-elution of the tritiated product with a genuine sample of 6 obtained via Scheme 1. The product had 45 Ci/mmol specific radioactivity.

20-Ethylenedioxy-3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnane-11-one (18).18

Selective reduction of 3,11-diketone 11 (555 mg, 1.48 mmol) with Selectride-K in THF at −78°C was achieved as described18, except urea-hydrogen peroxide complex was used instead of aqueous H2O2. While the yield was nearly quantitative, the crude product contained up to 10% of the 3β-OH-isomer. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 4.04 (brs, 1H, 3β-CH), 4.02 - 3.83 (m, 4H, OCH2CH2O), 2.59 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 2.31 – 2.20 (m, 2H), 2.03 (t, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H), 1.93 – 1.70 (m, 7H), 1.70 – 1.61 (m, 2H), 1.61 – 1.48 (m, 3H), 1.44 – 1.31 (m, 2H), 1.26 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.30 – 1.09 (m, 5H), 1.02 (s, 3H, CH3), 0.72 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 211.6 (C=O), 111.3 (O-C-O), 66.3, 64.8, 64.2, 63.2, 57.8, 56.9, 55.6, 46.0, 39.0, 36.3, 35.7, 35.3, 32.5, 30.9, 28.9, 27.9, 24.3, 23.5, 23.3, 14.1, 10.9.

11-Azi-20-ethylenedioxy-3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnane (23)

Formation of an oxime 19. A suspension of the ketone 18 (947 mg, 2.51 mmol), hydroxylamine hydrochloride (1.72 g, 25 mmol) and sodium hydroxide (1.10 g, 27.5 mmol) in methanol (10 mL) was refluxed with stirring under nitrogen atmosphere. After 36 h, the reaction mixture was cooled, and additional portion of hydroxylamine hydrochloride and NaOH (same amounts as above) was added, and the resulted heavy colorless suspension was refluxed for another 48 h. The reaction mixture was filtered, extracted with water (20 mL), and divided between water (20 mL) and ethyl acetate (50 mL). The phases were separated, the organic phase was washed with brine (10 mL), dried over MgSO4 and evaporated under vacuum. Nitrozation of the oxime 19. The foregoing crude oxime 19 and finely powdered sodium nitrite were dispersed in dry dichloromethane (40 mL) with vigorous stirring. Glacial acetic acid (2.17 mL, 38 mmol) was added dropwise during 2 h with slow nitrous oxide evolution, and the resulted colored reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for extra 2 h. The reaction mixture was washed with 5% sodium bicarbonate (40 mL) and brine (20 mL), dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under vacuum. Formation of the imine 21. The crude product from the above step was cooled on ice bath under argon, and ammonia in methanol (~7 M, 5 mL) was added dropwise. The reaction flask was sealed with a septum and warmed up to room temperature. After 5 h of stirring, the resulted light-orange suspension was concentrated and dried under high vacuum. Formation of the diaziridine 22. A suspension of hydroxylaminesulfonic acid (1.819 g, 16.1 mmol) in dry methanol (5 mL) under argon was cooled to −70°C and diisopropylethylamine (3.08 mL, 17.7 mmol) was added dropwise with vigorous stirring. The resulted mixture was slowly warmed up to room temperature (during 1 h) and added via syringe to the cooled (−50°C) crude imine 21 with stirring under argon. After 3 h of stirring at 0°C, the reaction mixture was left in a refrigerator for one week with occasional stirring. Formation of the diazirine 23. The reaction mixture from the previous step was divided between the solution of Na2CO3 [1.0 g in water (15 mL)] and triethylamine (2 mL) and EtOAc (20 mL). Phases were separated and the organic layer was washed with H2O (10 mL), diluted with MeOH (10 mL) and cooled to −5°C with stirring. The excess of iodine (634 mg, 2.5 mmol) was added portionwise, the mixture stirred for 10 min on ice bath, then 5 min at room temperature. The resulted brown solution was washed with 5% aqueous sodium sulfite, water and brine (10 mL each), dried over MgSO4, concentrated under vacuum and chromatographed on silica gel using ethyl acetate – hexane 1:4 to 2:3, with 0.1% of trimethylamine, for elution. The product was recrystallized from methanol (1 mL). The product was also isolated from the mother liquor by reverse phase HPLC using Phenomenex C18 column: 250 mm × 21.2 mm and Macherey-Nagel guard column 16×10 mm, both with 5 μm grain. Eluent A: methanol-water 1:1, eluent B: pure methanol; 10 mL/min. Elution: 0–2 min 1%B, 2–44 min gradient 1% B to 99% B, then 99%B (44–64 min). The elution of the product (retention time 48.1 min) was monitored by UV at 254 and 350 nm. The combined yield of 23 was 62 mg (6.3% from 18). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 3.94 (brs, 3β-H), 3.98 – 3.78 (m, 4H, OCH2CH2O), 1.88 – 1.66 (m, 8H), 1.54 – 1.12 (m, 10H), 1.18 (s, 3H), 1.09 (s, 3H), 1.08 – 0.92 (m, 1H), 0.92 – 0.77 (m, 1H), 0.68 (d, J = 13.7 Hz), 0.48 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 111.5 (O-C-O), 65.8, 64.8, 63.2, 57.3, 56.5, 53.3, 48.7, 43.5, 39.4, 35.5, 35.3, 35.0, 31.7, 31.6, 30.3, 28.4, 28.2, 24.2, 23.8, 23.0, 14.0, 11.1. HR MS: predicted for C23H37N2O3 [M+H]+: 389.2804; found: 389.2557.

11-Aziallopregnanolone (7)

Diazirine ketal 23 (5.0 mg, 0.0129 mmol) was dissolved in a mixture of methanol (2 mL), water (1 mL) and 1M aqueous hydrochloric acid (0.2 mL) and stirred for 10 min. The dissolution of the substrate occurred after 10 min, and the reaction was complete after 30 min. The product was purified by HPLC (using the same chromatography conditions as described above) to afford the ketone 7 in a nearly quantitative yield, The product was eluted at the retention time of 42.2 min. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 3.95 (brq, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H, 3β-H), 2.50 (t, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 2.25 – 2.12 (m, 1H), 2.03 (d, J ~13 Hz), 1.88 – 1.66 (m, 4H), 1.53 – 1.28 (m, 9H), 1.28 – 1.05 (m, 3H), 1.05 – 0.97 (m, 1H), 0.95 (s, 3H), 0.86 (dt, J = 13.2, 3.5 Hz), 0.67 (d, J = 13.2 Hz), 0.48 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 208.5 (C=O), 65.7, 62.7, 56.8, 53.2, 47.9, 45.0, 39.4, 35.5, 35.4, 35.3, 31.8, 31.5, 31.1, 30.1, 28.4, 28.0, 24.3, 22.7, 14.2, 11.0. HR MS: predicted for C21H33N2O2 [M+H]+: 345.2540; found: 345.2537.

3,11-Dioxo-20-ethylenedioxy-pregn-4-ene (24)

Compound 24 was obtained in 83% yield by PCC oxidation of ketal 9, analogously to the synthesis of the diketone 11. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 5.71 (s, 1H, -CH=), 4.03 – 4.82 (m, 4H, OCH2CH2O), 2.77 (ddd, J = 13.6, 5.0, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 2.67 (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 1H), 2.53 – 2.35 (m, 2H), 2.35 – 2.23 (m, 2H), 2.03 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 2.00 – 1.75 (m, 6H), 1.72 – 1.56 (m, 2H), 1.41 (s, 3H), 1.36 – 1.22 (m, 2H), 1.25 (s, 3H), 0.77 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 209.6 (C=O), 199.7 (C=O), 168.9, 124.4 (=CH-), 111.1 (O-C-O), 64.8, 63.2, 62.7, 57.7, 56.7, 54.7, 38.2, 36.5, 34.7, 33.7, 32.3, 32.1, 24.3, 23.5, 23.4, 17.2, 14.1. HR MS: predicted for C23H33O4 [M+H]+ 373.2379; found: 373.2373.

20-Ethylenedioxy-3β-hydroxy-11-oxo-pregn-4-ene (25)

A suspension of enedione 24 (2.586 g, 6.94 mmol) in MeOH (50 mL) and NaOH (28 mg, 0.7 mmol) was cooled on ice bath with stirring. NaBH4 (263 mg, 6.94 mmol) was added in small portions over the period of 1 h. The reaction mixture was partitioned between ethyl acetate (200 mL) and water (100 mL), the upper layer was washed with water and brine (50 mL each), dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under vacuum. Chromatography on silica gel using methyl tert-butyl ether as eluent and subsequent crystallization afforded pure 25 as colorless crystals, yield 527 mg (20%). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 5.34 (brd, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H, -CH=), 4.13 (br. s, 1H, 3α-H), 4.03 – 4.82 (m, 4H, OCH2CH2O), 2.63 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 1H), 2.50 (ddd, J = 13.7, 4.5, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 2.30 – 2.18 (m, 2H), 2.10 – 1.98 (m, 2H), 1.97 – 1.72 (m, 7H), 1.68 – 1.58 (m, 1H), 1.53 – 1.40 (m, 1H), 1.37 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 1.35 – 1.25 (m, 1H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.26 (s, 3H), 1.24 – 1.06 (m, 2H), 0.75 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 210.9 (C=O), 145.7, 125.0 (=CH-), 111.2 (O-C-O), 67.7, 64.9, 63.9, 63.2, 57.8, 56.8, 55.1, 45.8, 36.9, 36.8, 34.4, 33.4, 31.8, 29.0, 24.3, 23.5, 23.4, 18.9, 14.1.

11-Azi-20-ethylenedioxy-3β-hydroxy-pregn-4-ene (26)

The diazirine 26 was synthesized in 5% yield from 11-ketone 25 using the analogous procedure as described above. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 5.24 (brq, J ~ 1.4 Hz, 1H, -CH=), 4.09 (br. s, 1H), 3.99 – 3.80 (m, 4H, OCH2CH2O), 2.17 (tm, J = 14.0, ~2.3 Hz), 1.99 (ddd, J = 13.9, 4.1, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 1.92 (dd, J = 11.2, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 1.89 – 1.68 (m, 7H), 1.39 (d, J =4.0 Hz, 1H), 1.36 (s, 1H), 1.35 – 1.18 (m, 2H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.16 – 1.12 (m, 2H), 1.11 (s, 3H), 0.94 (qd, J ~ 12.0, 4.2 Hz), 0.79 (s, 3H), 0.70 (d, J = 13.6 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 146.2, 124.3 (-CH=), 111.4 (O-C-O), 67.2, 64.8, 63.2, 57.3, 56.0, 53.1, 48.7, 43.4, 36.5, 35.4, 34.7, 32.8, 32.0, 30.2, 28.3, 24.2, 23.8, 23.0, 20.0, 13.9.

11-Azi-20-ethylenedioxy-3α-hydroxy-pregn-4-ene (27)

The flask (3 mL) containing 3β-alcohol 26 (20 mg, 0.052 mmol) and PPh3 (27 mg, 0.104 mmol) was purged with argon, and the solids dissolved in THF (1 mL). Neat formic acid (4 μL, 0.104 mmol) was added at once, followed by diethyl azodicarboxylate (16 μL, 0.104 mmol). The resulted light-yellowish solution was left stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The reaction mixture was divided between methyl tert-butyl ether (3 mL) and aqueous NaHCO3 (2%, 1 mL), the organic phase washed with water (1 mL), added with methanolic NaOH (1M, 0.2 mL) and left for for 20 min. The reaction mixture was washed with water and brine (1 mL each), dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under vacuum. Chromatography on silica (ethyl acetate – hexane 1:4, 0.1% NEt3), afforded diastereomerically pure 27, contaminated with 33 mol. % of bis-(ethoxycarbonyl)hydrazine (DEAD-H2). This product was used for the reduction in the presence of the rhodium catalyst without further purification, as described below. Yield 18 mg (78%). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 5.43 (dd, J = 4.8, 1.2 Hz, 1H, -CH=), 3.98 (br. s, 1H, 3b-OH), 3.98 – 3.80 (m, 4H, OCH2CH2O), 2.18 (t, J ~ 13.7, 2.3 Hz), 1.99 (ddd, J = 13.8, 4.0, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 1.92 (dd, J = 11.2, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 1.89 – 1.70 (m, 6H), 1.62 - 1.48 (m, 2H), 1.47 (d, J = 11.0 Hz), 1.45 – 1.40 (m, 1H), 1.40 – 1.19 (m, 3H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.06 – 0.91 (m, 2H), 0.72 (d, J = 13.6 Hz), 0.69 (s, 3H). HR MS: calculated for C23H33N2O3 [M-H]−: 385.2491; found: 385.2631.

Rhodium Catalyst Rh+(dppf)(NBD)SbF6− (29)

The solution of bis-acetonitrile-[norbornadiene]-rhodium(I) hexafluoroantimonate (51.3 mg, 100 mmol) in dry THF (1 mL) was stirred under argon and 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene (61 mg, 110 mmol) was slowly added. The resulted bright-red solution was stirred at room temperature for 30 min and concentrated using a stream of argon until crystallization of the product has started. Absolute ether (0.5 mL) was added and the resulting suspension was stirred for another 30 min, filtered under positive argon pressure and washed with ether (1 mL). Yield 86 mg (87%). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.77 – 7.68 (m, 8H, o-Ph), 7.65 – 7.55 (m, 12H, m-, p-Ph), 4.44 (br s, 4H), 4.39 (s, 4H), 4.35 (s, 4H), 4.00 (br s, 2H), 1.57 (s, 2H, -CH2-). ESHR MS: (positive-ion mode): predicted for C41H36FeP2Rh [cation]+: 749.07; found: 749.07, (negative-ion mode), predicted for SbF6− [anion]−: 234.89, found: 234.87.

11-Azi-20-ethylenedioxy-allopregnanolone (28) and 11-aziallopregnanolone (7)

All the glassware was flame-dried and cooled under argon. The reaction was done in a small, custom made piece of glassware with a very small stirring bar, in order to maintain strictly anaerobic and anhydrous condition during the reaction. Unsaturated alcohol 27 (1.0 mg, 2.6 μmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (0.2 mL), and catalyst 29 was added. The solution was purged by a stream of hydrogen gas under slightly positive pressure. After one hour, the resulted dark red-brown solution was diluted with mixture of aqueous HCl (1 M) and methanol (1:9, 0.1 mL) and stirred for 5 min. The reaction mixture was diluted with methanol-water 1:1 (0.3 mL), filtered through a submicron filter and chromatographed on a semi-prep HPLC column: Phenomenex Luna (2), 21mm × 250mm, 5 μm, C18 with Macherey-Nagel Nucleodur guard column, 10 x16 mm, 5 μm, C18 using 10 mL/min flow rate. Gradient conditions: phase A, methanol-water 1:1, phase B, methanol; gradient: 1% B, 0–2 min, then linear gradient to 99% B at 44 min, followed by washing with 99% B for the next 20 min. Fraction collector: 1.5 mL each fraction, starting from 38 min. Detection: UV at 254 and 350 nm wavelength, the pure diazirine fractions were identified by the characteristic absorption at 350 nm, that is ~2 times greater than that at 254 nm. Under those conditions the retention times were 42.2 min for 20-ketone 7, 48.1 min for 20-ketal 28, and 47.5 min for substrate 27. The combined yield of 28 and 7 was nearly quantitative. TLC and 1H NMR spectra of the products were identical with those of the product obtained via Scheme 3. The tritiation was performed by Vitrax Inc. using analogous procedure to that described above. [3H]11-azi-AP was purified by HPLC using Eclipse XDB-C18, 5 mm, 4.6×150 mm column using linear gradient of acetonitrile in isocratic 0.05% TFA-H20 (50% ACN at t=0, 90% CAN at t=10 min) at 1.0 mL/min flow rate. The product had 30 Ci/mmol specific radioactivity.

Chart 1.

Highlights.

Two photoreactive 5-α-neurosteroid modulators of GABAAR were synthesized

Both ligands are potent general anesthetics and GABAAR receptor modulators

Both ligands interact with GABAAR at sites distinct from etomidate or barbiturate site

3H-Ligands photolabel α- and β-subunits in α1β3γ2-GABA receptor

Photolabeling is not inhibited by alphaxalone or the unlabeled ligands

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute for General Medicine to K.W.M. (GM 58448). Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. We thank Dr. Bernard Santarsierro for determination of x-ray structures of compounds 6 and 7. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor for the support of this research program (Grant 085P1000817).

Abbreviations Used

- ACh

acetylcholine

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- DMSO

methyl sulfoxide

- TBDMS

tert-butyldimethylsilyl

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- EC50

concentration required for 50% of full effect

- EC5

concentration required for 5% of full effect

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- GABAAR

GABAA-type receptor

- IC50

concentration required for 50% of full inhibitory effect

- LoRR

loss of righting reflexes

- nH

Hill coefficient

- SD

standard deviation

- TFD

trifluoromethyldiazirine

- THF

tetrahydrofurane

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Olsen RW, Sieghart W. GABAA receptors: Subtypes provide diversity of function and pharmacology. Neuropharmacol. 2009;56:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambert JJ, Belelli D, Hill-Venning C, Peters JA. Neurosteroids and GABAA receptor function. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, da Silva HM, Smart TG. Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABAA receptors through two discrete transmembrane sites. Nature. 2006;444:486–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABA(A) receptor. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:565–75. doi: 10.1038/nrn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornet WT, Popescu DT. Althesin (alphadione, CT 1341): a ‘new’ induction agent for anesthesia. Arch Chir Neerl. 1977;29:135–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke RS. Adverse effects of intravenously administered drugs used in anaesthetic practice. Drugs. 1981;22:26–41. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198122010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nohria V, Giller E. Ganaxolone. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4:102–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metcalfe S, Hulands-Nave A, Bell M, Kidd C, Pasloske K, O’Hagan B, Perkins N, Wilhelm T. Multicentre, randomised clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of alphaxalone administered to bitches for induction of anaesthesia prior to caesarean section. Aust Vet J. 2014;92:333–8. doi: 10.1111/avj.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akk G, Covey DF, Evers AS, Steinbach JH, Zorumski CF, Mennerick S. Mechanisms of neurosteroid interactions with GABA(A) receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;116:35–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Covey DF, Nathan D, Kalkbrenner M, Nilsson KR, Hu Y, Zorumski CF, Evers AS. Enantioselectivity of pregnanolone-induced γ-aminobutyric acid(A) receptor modulation and anesthesia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:1009–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogenkamp DJ, Tahir SH, Hawkinson JE, Upasani RB, Alauddin M, Kimbrough CL, Acosta-Burruel M, Whittemore ER, Woodward RM, Lan NC, Gee KW, Bolger MB. Synthesis and in vitro activity of 3β-substituted-3α-hydroxypregnan-20-ones: allosteric modulators of the GABAA receptor. J Med Chem. 1997;40:61–72. doi: 10.1021/jm960021x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnan K, Manion BD, Taylor A, Bracamontes J, Steinbach JH, Reichert DE, Evers AS, Zorumski CF, Mennerick S, Covey DF. Neurosteroid analogues. Inverted binding orientations of androsterone enantiomers at the steroid potentiation site on γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. J Med Chem. 2012;55:1334–45. doi: 10.1021/jm2014925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slavikova B, Bujons J, Matyas L, Vidal M, Babot Z, Kristofikova Z, Sunol C, Kasal A. Allopregnanolone and pregnanolone analogues modified in the C ring: Synthesis and activity. J Med Chem. 2013;56:2323–36. doi: 10.1021/jm3016365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bandyopadhyaya AK, Manion BD, Benz A, Taylor A, Rath NP, Evers AS, Zorumski CF, Mennerick S, Covey DF. Neurosteroid analogues. A comparative study of the anesthetic and GABA-ergic actions of alphaxalone, Δ16-alphaxalone and their corresponding 17-carbonitrile analogues. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:6680–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darbandi-Tonkabon R, Hastings WR, Zeng CM, Akk G, Manion BD, Bracamontes JR, Steinbach JH, Mennerick SJ, Covey DF, Evers AS. Photoaffinity labeling with a neuroactive steroid analogue. 6-azi-pregnanolone labels voltage-dependent anion channel-1 in rat brain. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13196–206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen ZW, Manion B, Townsend RR, Reichert DE, Covey DF, Steinbach JH, Sieghart W, Fuchs K, Evers AS. Neurosteroid analog photolabeling of a site in the third transmembrane domain of the β3 subunit of the GABA(A) receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82:408–19. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.078410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen CW, Wang C, Krishnan K, Manion BD, Hastings R, Bracamontes J, Taylor A, Eaton MM, Zorumski CF, Steinbach JH, Akk G, Mennerick S, Covey DF, Evers AS. 11-Trifluoromethylphenyldiazirinyl neurosteroid analogues: potent general anesthetics and photolabeling reagents for GABAA receptors. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:3479–91. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3568-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komarapuri S, Krishnan K, Covey DF. Synthesis of 19-trideuterated ent-testosterone and the GABAA receptor potentiators ent-androsterone and ent-etiocholanolone. J Label Compd Radiopharm. 2008;51:430–434. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stastná E, Cerný I, Pouzar V, Chodounská H. Stereoselectivity of sodium borohydride reduction of saturated steroidal ketones utilizing conditions of Luche reduction. Steroids. 2010;75:721–5. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kupfer R, Rosenberg MG, Brinker UH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:6647–6648. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li GD, Chiara DC, Cohen JB, Olsen RW. Neurosteroids allosterically modulate binding of the anesthetic etomidate to gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11771–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C900016200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiara DC, Jayakar SS, Zhou X, Zhang X, Savechenkov PY, Bruzik KS, Miller KW, Cohen JB. Specificity of intersubunit anesthetic binding sites in the transmembrane domain of the human α1β3γ2 GABAA receptor. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:19343–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.479725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Estrada-Mondragon A, Lynch JW. Functional characterization of ivermectin binding sites in α1β2γ2L GABA(A) receptors. Front Mol Neurosci. 2015;8:55. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiara DC, Trinidad JC, Wang D, Ziebell MR, Sullivan D, Cohen JB. Identification of amino acids in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist binding site and ion channel photolabeled by 4-[(3-trifluoromethyl)-3H-diazirin-3-yl]benzoylcholine, a novel photoaffinity antagonist. Biochemistry. 2003;42:271–83. doi: 10.1021/bi0269815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eckenhoff RG, Xi J, Shimaoka M, Bhattacharji A, Covarrubias M, Dailey PD. Azi-isoflurane, a photolabel analog of the commonly used inhaled general anesthetic isoflurane. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2010;1:139–145. doi: 10.1021/cn900014m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jayakar SS, Dailey WP, Eckenhoff RG, Cohen JB. Identification of propofol binding sites in a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with a photoreactive propofol analog. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6178–89. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.435909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jayakar SS, Zhou X, Chiara DC, Dostalova Z, Savechenkov PY, Bruzik KS, Dailey WP, Miller KW, Eckenhoff RG, Cohen JB. Multiple propofol-binding sites in a γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor (GABAAR) identified using a photoreactive propofol analog. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:27456–68. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.581728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li GD, Chiara DC, Sawyer GW, Husain SS, Olsen RW, Cohen JB. Identification of a GABAA receptor anesthetic binding site at subunit interfaces by photolabeling with an etomidate analog. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11599–605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3467-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiara DC, Dostalova Z, Jayakar SS, Miller KW, Cohen JB. Mapping general anesthetic binding site(s) in human α1β3 γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors with [3H]TDBzl-etomidate, a photoreactive etomidate analogue. Biochemistry. 2012;51:836–47. doi: 10.1021/bi201772m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart DS, Savechenkov PY, Dostalova Z, Chiara DC, Ge R, Raines DE, Cohen JB, Forman SA, Bruzik KS, Miller KW. Allyl mTFD-mephobarbital: A potent enantioselective and photoreactive barbiturate general anesthetic. J Med Chem. 2012;55:6554–6565. doi: 10.1021/jm300631e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akk G, Covey DF, Evers AS, Steinbach JH, Zorumski CF, Mennerick S. The influence of the membrane on neurosteroid actions at GABAA Receptors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34S1:S59–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clarke RS, Dundee JW, Carson IW. A new steroid anaesthetic-Althesin. Proc Royal Soc Med. 1973;66:1027–1030. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laxer K, Blum D, Abou-Khalil BW, Morrell MJ, Lee DA, Data JL, Monaghan EP. Assessment of ganaxolone’s anticonvulsant activity using a randomized, double-blind, presurgical trial design. Ganaxolone Presurgical Study Group. Epilepsia. 2000;41:1187–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pieribone VA, Tsai J, Soufflet C, Rey E, Shaw K, Giller E, Dulac O. Clinical evaluation of ganaxolone in pediatric and adolescent patients with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1870–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]