Abstract

Incidental orbital masses that are asymptomatic and appear benign are often observed without surgical intervention unless there is a clinical or radiographic change in the mass. There is a burgeoning population of cancer patients with incidental masses that have been detected while under surveillance for metastasis. This population of patients is growing due to a number of reasons, including more extensive imaging, an aging population, and more effective cancer treatments. Closer scrutiny should be applied to these patients, due to the possibility of the mass being an orbital metastasis. In addition, the approach to these patients may have implications regarding the adult patient without a cancer history who presents with a symptomatic orbital mass. The purpose of this paper is to explore the approach to the patient with and without a cancer history who presents with an orbital mass.

Keywords: Orbital biopsy, orbital metastasis, orbital tumor

Introduction

Treatment of the incidental orbital mass is not a novel subject. This became an issue with newer imaging modalities and the increasing frequency of imaging. It is not uncommon for the orbital surgeon to assess an orbital mass detected on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head in a patient being evaluated for headaches. If the patient is asymptomatic and the mass has the typical appearance of a benign lesion (e.g., cavernous malformation), most patients would be reassured and kept under surveillance. Biopsy of the incidental mass is usually reserved for patients that are symptomatic or those patients who request biopsy for peace of mind. If any change in the mass is noted during surveillance or if the patient develops symptoms, biopsy is usually recommended. However, the vast majority of patients can continue to live without intervention with a mass that has potentially been present for decades.

In recent years, a new population of patients has presented with orbital masses that have required closer scrutiny. Due to the increasing age of the population in the United States and the availability of more effective cancer treatments, patients with a history of cancer are being seen more often with orbital masses. These patients are undergoing more extensive imaging for surveillance of metastatic disease. A dilemma is thus presented to the orbital surgeon: can these incidental masses be treated similar to those seen in the noncancer patients, or should the threshold for biopsy in these patients be lower to ensure a metastatic lesion is not missed?

The purpose of this paper is to examine these questions as well as others. When should a patient with a history of cancer and an incidental orbital mass undergo biopsy? What are the characteristics of an orbital mass that should make one suspect a metastasis? In a noncancer patient, should patients with symptomatic orbital masses undergo more extensive study before biopsy, as any patient may initially present with a metastatic lesion in the orbit? Should we reevaluate the role of fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) in these patients?

Orbital Metastases

Metastatic orbital lesions have been estimated to account for 1%–13% of all orbital tumors.[1,2,3] 2%–5% of patients with systemic cancer are reported to have an orbital metastasis.[4] Spread to the orbit is secondary to hematogenous spread of the primary tumor. The most common primary cancers with orbital metastases are breast, lung, and prostate.[5] Breast consistently ranks the most common primary site, with 48%–53% of metastatic orbital lesions.[6] Other sites include kidney, thyroid, stomach, melanoma, and pancreas.[7] The frequency at each of the sites can differ depending on the demographics and country of origin of the study.[8] A study from southern China reported nasopharyngeal carcinoma to be the most common primary cancer that metastasized to the orbit.[9] Most orbital metastases are carcinomas; sarcomas and melanomas are considerably less common.[2,10] Clinical presentations include diplopia (48%), proptosis (26%), pain (19%), decreased vision (16%), ptosis (10%), and palpable mass.[1] Scirrhous breast carcinoma may present with enophthalmos. The mean age of patients is 60 years in different series.[11,12] The median survival of patients with orbital metastasis was reported 40 years ago to be 15.6 months.[13] A more recent study showed survival is very similar to that noted 40 years ago, limited to 1.5 years after diagnosis, independent of the histological type, with 29% of patients alive after 17 months. This same study showed the orbit was the first presentation in 15% of the cases.[14] The mean time of presentation of orbital metastasis after the diagnosis of primary cancer has been found to be 52 months; however, orbital metastases can occur at any time after initial cancer diagnosis, with one case presenting after 35 years.[15] The incidence of reported orbital metastases has been increasing.[1] This may be due to improved treatments, which has led to an increase in the median survival of cancer patients. Other considerations include advances in the diagnosis and application of imaging techniques which has led to an increase in the detection of these lesions.[8]

Evaluation of the Suspected Orbital Metastasis

When presented with an orbital mass in a patient with a cancer history, the history, examination, and imaging characteristics can usually determine if the mass would be suspected to be a metastasis. A patient with no symptoms strongly suggests a benign lesion. Due to the small space of the orbit and the relatively rapid growth of most metastatic lesions, symptoms would be produced in a metastatic orbital mass. Some metastases are relatively slow growing and may mimic a benign lesion; however, authors have argued that orbital metastases very rarely present as a slowly progressive mass.[2] With slow growth, symptoms may arise slowly or not at all with the patient being able to adapt with horizontal and vertical fusion amplitudes. A consideration is whether delay in diagnosis of a slow-growing metastasis would result in an increase in morbidity or mortality. If the patient has a cancer history, evaluation for other distant metastases would have already been performed. In addition, most suspected benign lesions would be placed under surveillance to ensure that they maintain a benign character. If a slow-growing metastatic lesion is thought to be benign, surveillance would detect additional growth. However, the isolated orbital mass in a patient with cancer history and no other evidence of metastasis may have prognostic implications, as an orbital metastasis would increase the stage of the patient's cancer.

Examination of the patient should look for any orbital signs to help determine if a metastasis is suspected. Although any space occupying mass (benign or malignant) may result in axial displacement of the globe, most metastases will produce a motility deficit, pain, or decrease in vision.[1] Benign lesions are usually asymptomatic, or symptoms may progress very slowly on the order of years.

Imaging characteristics of the lesion will also help in determining if a mass is suspected to be a metastasis or not. Metastatic lesions are more common in the anterior orbit than posterior orbit.[10] Well-encapsulated, discrete, and focal intraconal masses are unlikely to be metastases while masses which involve the extraocular muscles and bone are much more likely to be metastases [Figure 1]. No area of the orbit is immune to a metastasis, with case reports of metastases to every anatomic structure of the orbit, including the subperiosteal space.[16] Tumor pattern can vary from diffuse infiltrative to a focal mass. Metastases from carcinoid, renal cell carcinoma, and melanoma tend to be circumscribed [Figure 2]. All orbital metastases should show some enhancement with contrast on MRI.[17]

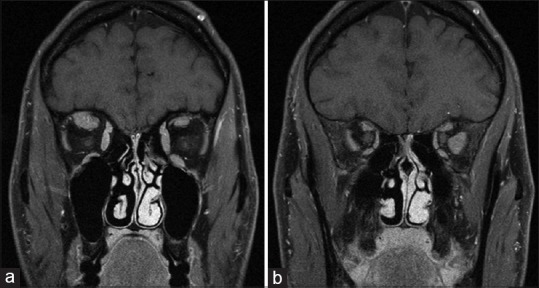

Figure 1.

A 38-year-old with a history of metastatic pancreatic cancer. The patient presented with new onset diplopia. T1 weighted, fat suppressed magnetic resonance imaging shows a metastatic lesion to the right superior rectus (a) and left lateral rectus (b)

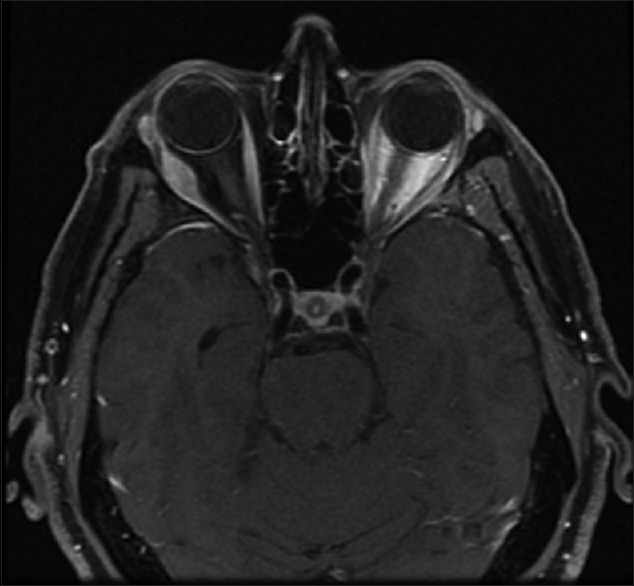

Figure 2.

A 51-year-old with a history of metastatic carcinoid tumor with new proptosis. T1 weighted, fat suppressed magnetic resonance imaging shows a right lateral rectus, well-circumscribed mass

It is critical to review all of the patient's imaging. Often, many cancer patients have had previous head imaging performed which includes the orbit. A new mass that was not present in previous imaging in a cancer patient is highly suggestive of a metastasis, while a lesion that was present on previous imaging (often not noted by the radiologist reading the brain imaging) and is unchanged is less likely to be a metastasis. As many patients have had multiple previous scans at different institutions, it is critical to obtain and personally review the previous imaging to confirm if the mass was present before.

When and How to Biopsy a Suspected Orbital Metastasis

With regards to biopsy of the mass, this should be performed when requested by the oncologist. In patients with widespread disease and a new orbital mass, biopsy rarely needs to be performed to confirm metastasis. Situations in which biopsy may be necessary include a solitary metastasis to the orbit with no other metastatic disease or in those cases in which decreasing tumor burden may result in more effective chemotherapy or radiation. In addition, biopsy of the orbit may present less risk than other sites, as in those situation in which additional material may be needed for staging or therapeutic decisions. This is especially true when newer therapies (targeted therapy) may depend on the molecular analysis of the tumor, or when the metastasis is behaving in a different manner compared to the primary tumor. An anterior orbital location to the metastasis has been reported in 66% of cases, allowing easy access.[2] In those cases, which only need a confirming biopsy, FNAB may be the most prudent method rather than open biopsy.[18] The availability of previous pathology from the patient enables the cytopathologist to determine if the FNAB specimen is the same tumor. This ability to have a known specimen with which to compare places the use of FNAB in an advantageous position rather than relying on a new diagnosis from what is often scant material.

When to Suspect a Metastasis in a Patient Without a Cancer History

When should a metastasis be suspected in a noncancer patient, and should these patients undergo a metastatic work up even before biopsy of the orbital mass? It could be argued that any adult patient with a new, symptomatic orbital mass should be suspected to have a metastasis until proven otherwise. In the series from the Wills Hospital, 93% of patients with orbital metastasis were 40 years of age or older. The most common metastases in children are neuroblastoma, Wilms tumor, and Ewing sarcoma.[19] In contrast to uveal metastases, orbital metastases are much more often unilateral than bilateral.[10]

Patients who present with an orbital metastasis with no previous history of cancer were noted in 19%–32% of orbital lesions that proved to be a metastasis.[2,10,11,15] Unfortunately, a significant portion of these patients never has a primary tumor detected, with the biopsy only showing poorly differentiated carcinoma.

New onset orbital processes which do not suggest inflammation and are not based in the lacrimal gland in an older patient are likely to be a metastasis or lymphoma. In these patients, it may be prudent to perform a metastatic work up with a positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) before biopsy. One could argue that many of these tumors end up being lymphoma, but if it is lymphoma, those patients will undergo a PET/CT. This approach of doing a whole-body PET/CT before biopsy of an orbital mass would be especially useful for those masses in the posterior orbit that are in a relatively high-risk area. Some metastases are very vascular (e.g., renal cell carcinoma) and biopsy could result in significant morbidity.

The best support for the argument of whole-body PET/CT prior comes from the study by Demirci et al., that looked at orbital tumors in the senior adult population.[20] In this study, 63% of orbital tumors were found to be malignant. Earlier studies showed that the percentage of malignant tumors increased with age, with malignancies being common in older patients secondary to the higher incidence of lymphoma and metastases.[5] This is supported by an additional study which showed that in patients younger than 59 years, the most common space-occupying lesions were benign tumors, while in patients aged 60–92 years, the frequency of malignant tumors increased.[3]

Are We Entering a New Era in the Evaluation of Orbital Masses?

With increasing age, orbital tumors become more common.[21] The number of orbital tumors encountered by the orbital surgeon will, thus, be exacerbated by the increasing age of the population. In general, a new era is bring entered for the evaluation of patients with orbital masses. First, there are many more cancer survivors who will present with orbital metastases. Second, it may not be unreasonable to observe some of these metastases, especially if the patient is under therapy that is controlling the primary tumor. Many metastases in the orbit do not need to be biopsied, as this is not the standard of care for metastases elsewhere in the body in patients with the known metastatic disease. If confirmation is needed, FNAB is an underutilized option and should be considered especially in cases where the previous pathology is available so that the aspirate can be compared. The prevalence of an orbital mass presenting as the first sign of metastatic disease brings up the question as to whether any nonbenign, noninflammatory appearing lesion should have a whole-body PET/CT before biopsy.

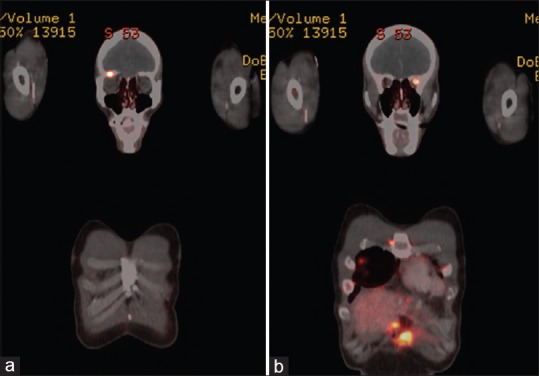

PET is commonly used in whole-body imaging of neoplasms [Figure 3]. The scan demonstrates areas of high uptake of a glucose labeled radiotracer. Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) PET/CT provides more precise localization of the uptake of the radiotracer 18-FDG. FDG accumulates in tumor cells. Ocular adnexal lymphoma (OAL) includes lymphomas that involve the orbit, eyelid, or conjunctiva. As a high percentage of patients presenting with OAL have systemic involvement, it is argued that thorough systemic staging should be performed with a whole-body PET/CT for any patient presenting with OAL.[22]

Figure 3.

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan of the patient from Figure 1. Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose uptake is noted in the right superior orbit (a) and left lateral orbit (b), consistent with a pancreatic cancer metastases

Is it concerning to detect a lesion that does not change, even if the appearance is not that of a benign lesion, especially if the patient has been surveilled for metastatic disease and the patient is undergoing systemic treatment? Char et al. noted that they managed a few patients with asymptomatic orbital metastases or with minor symptoms and far advanced disease by serial observation alone. This approach may become more common as these lesions become more frequent. In fact, routine surveillance of the orbit for metastasis is not undertaken as the small space will eventually result in the presence of symptoms.

Conclusion

As cancer treatment changes, so will our care of suspected or potential metastatic lesions of the orbit. The asymptomatic mass is just that – an asymptomatic mass. In a patient with known metastasis, an absence of symptoms with an incidental mass can often be observed until the mass produces symptoms. The increasing effectiveness of newer therapies will result in patients with orbital metastases living with their tumors with systemic treatment alone. However, any adult patient with a new, symptomatic orbital mass has a high likelihood of having a lesion which has systemic implications. Performing a primary biopsy may not be the most appropriate treatment for these patients, which may be able to be diagnosed with noninvasive imaging (albeit expensive), or potentially having other areas biopsied with less potential morbidity. In addition, the greater efficacy of FNAB introduces the potential of less morbidity and cost in the diagnosis and treatment of these patients.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ahmad SM, Esmaeli B. Metastatic tumors of the orbit and ocular adnexa. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18:405–13. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3282c5077c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magliozzi P, Strianese D, Bonavolontà P, Ferrara M, Ruggiero P, Carandente R, et al. Orbital metastases in Italy. Int J Ophthalmol. 2015;8:1018–23. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2015.05.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonavolontà G, Strianese D, Grassi P, Comune C, Tranfa F, Uccello G, et al. An analysis of 2,480 space-occupying lesions of the orbit from 1976 to 2011. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;29:79–86. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31827a7622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matlach J, Nowak J, Göbel W. Papilledema of unknown cause. Ophthalmologe. 2013;110:543–5. doi: 10.1007/s00347-012-2731-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields JA, Shields CL, Scartozzi R. Survey of 1264 patients with orbital tumors and simulating lesions: The 2002 Montgomery lecture, part 1. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:997–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meltzer DE, Chang AH, Shatzkes DR. Case 152: Orbital metastatic disease from breast carcinoma. Radiology. 2009;253:893–6. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2533081926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fahmy P, Heegaard S, Jensen OA, Prause JU. Metastases in the ophthalmic region in Denmark 1969-98. A histopathological study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003;81:47–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2003.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eldesouky MA, Elbakary MA. Clinical and imaging characteristics of orbital metastatic lesions among Egyptian patients. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:1683–7. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S87788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan J, Gao S. Metastatic orbital tumors in Southern China during an 18-year period. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:1387–93. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1660-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shields JA, Shields CL, Brotman HK, Carvalho C, Perez N, Eagle RC., Jr Cancer metastatic to the orbit: The 2000 Robert M. Curts Lecture. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;17:346, 54. doi: 10.1097/00002341-200109000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Char DH, Miller T, Kroll S. Orbital metastases: Diagnosis and course. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:386–90. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.5.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Günalp I, Gündüz K. Metastatic orbital tumors. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1995;39:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferry AP, Font RL. Carcinoma metastatic to the eye and orbit II. A clinicopathological study of 26 patients with carcinoma metastatic to the anterior segment of the eye. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93:472–82. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1975.01010020488002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valenzuela AA, Archibald CW, Fleming B, Ong L, O'Donnell B, Crompton JJ, et al. Orbital metastasis: Clinical features, management and outcome. Orbit. 2009;28:153–9. doi: 10.1080/01676830902897470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spraker MB, Francis CE, Korde L, Kim J, Halasz L. Solitary orbital metastasis 35 years after a diagnosis of lobular carcinoma in situ. Cureus. 2017;9:e1404. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nash S, Bartels H, Pemberton J. Metastatic cervical adenocarcinoma to the orbital subperiosteal space. Can J Ophthalmol. 2017;52:e60–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan SN, Sepahdari AR. Orbital masses: CT and MRI of common vascular lesions, benign tumors, and malignancies. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2012;26:373–83. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dresner SC, Kennerdell JS, Dekker A. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of metastatic orbital tumors. Surv Ophthalmol. 1983;27:397–8. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(83)90197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg RA, Rootman J. Clinical characteristics of metastatic orbital tumors. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:620–4. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32534-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demirci H, Shields CL, Shields JA, Honavar SG, Mercado GJ, Tovilla JC, et al. Orbital tumors in the older adult population. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:243–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Margo CE, Mulla ZD. Malignant tumors of the orbit. Analysis of the Florida cancer registry. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:185–90. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(98)92107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hui KH, Pfeiffer ML, Esmaeli B. Value of positron emission tomography/computed tomography in diagnosis and staging of primary ocular and orbital tumors. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2012;26:365–71. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]