Abstract

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are involved in the pathology of various tumors, including colorectal cancer (CRC). The crosstalk between carcinoma- associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and cancer cells in the tumor microenvironment promotes tumor development and confers chemoresistance. In this study, we further investigated the underlying tumor-promoting roles of CAFs and the molecular mediators involved in these processes.

Methods: The AOM/DSS-induced colitis-associated cancer (CAC) mouse model was established, and RNA sequencing was performed. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) sequences were used to knock down H19. Cell apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry. SW480 cells with H19 stably knocked down were used to establish a xenograft model. The indicated protein levels in xenograft tumor tissues were confirmed by immunohistochemistry assay, and cell apoptosis was analyzed by TUNEL apoptosis assay. RNA-FISH and immunofluorescence assays were performed to assess the expression of H19 in tumor stroma and cancer nests. The AldeRed ALDH detection assay was performed to detect intracellular aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) enzyme activity. Isolated exosomes were identified by transmission electron microscopy, nanoparticle tracking and Western blotting.

Results: H19 was highly expressed in the tumor tissues of CAC mice compared with the expression in normal colon tissues. The up-regulation of H19 was also confirmed in CRC patient samples at different tumor node metastasis (TNM) stages. Moreover, H19 was associated with the stemness of colorectal cancer stem cells (CSCs) in CRC specimens. H19 promoted the stemness of CSCs and increased the frequency of tumor-initiating cells. RNA-FISH showed higher expression of H19 in tumor stroma than in cancer nests. Of note, H19 was enriched in CAF-derived conditioned medium and exosomes, which in turn promoted the stemness of CSCs and the chemoresistance of CRC cells in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, H19 activated the β-catenin pathway via acting as a competing endogenous RNA sponge for miR-141 in CRC, while miR-141 significantly inhibited the stemness of CRC cells.

Conclusion: CAFs promote the stemness and chemoresistance of CRC by transferring exosomal H19. H19 activated the β-catenin pathway via acting as a competing endogenous RNA sponge for miR-141, while miR-141 inhibited the stemness of CRC cells. Our findings indicate that H19 expressed by CAFs of the colorectal tumor stroma contributes to tumor development and chemoresistance.

Keywords: H19, CRC, CAFs, stemness, chemoresistance

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most frequently diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death globally 1. Despite the declining mortality rate of CRC, mainly due to advances in screening tests, surgery, radiation therapy and adjuvant chemotherapy, more than 40% of CRC patients die from tumor recurrence and metastasis 2. Acquisition of resistance to multiple chemotherapeutics leads to the main therapy failure in CRC. Emerging evidence indicates that cancer stem cells (CSCs), a cellular subpopulation with stem cell-like features, are critical for CRC initiation, progression, relapse, metastasis and chemoresistance 3-5. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), one of the primary stromal cell types in the stroma of CRC tissues, also play an important role in tumor proliferation, metastasis, angiogenesis and chemoresistance by utilizing paracrine factors 6-8. CAFs can remodel the extracellular matrix structure and tumor microenvironment, which contribute to generate the CSC niche 9, 10.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a heterogeneous class of transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with limited protein-coding potential 11. They are involved in multiple cellular and biological processes by interacting with various macromolecules such as DNA, chromatin, proteins, and RNAs 12-14. LncRNAs are aberrantly expressed in multiple human cancers, such as colorectal, prostate, breast, liver, brain cancer, renal, and bladder cancer, where they may modulate numerous hallmarks to promote or inhibit CRC development, invasion, and metastasis including proliferation, apoptosis, metastasis and metabolism 15-19. Nevertheless, the roles of lncRNAs in controlling CSC maintenance and chemoresistance are poorly understood.

H19 is maternally imprinted and critical for embryonic development and growth control 20, 21. Previous studies have reported that H19 maintains the repopulating ability of hematopoietic stem cells through a miR-675-Igf1r signaling circuit 22. Abundantly expressed H19 is found in a majority of human cancers, including CRC, hepatocellular carcinoma, esophageal cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer and bladder cancer, and plays a role in oncogenesis 23-26. In CRC, high H19 expression was correlated with poor prognosis of CRC patients and shown to be involved in cell proliferation, cycle, and migration of CRC cells 27-30. Although those findings have indicated the important roles of H19 in tumorigenicity, the role of H19 in stemness and chemoresistance of CRC is still unknown. In addition, little is known about the upstream factors that induce the abundant expression of H19 in CRC.

RNA molecules, including mRNAs, microRNAs, circular RNAs and lncRNAs, are highly enriched in exosomes, which are nanosized vesicles (30-150 nm) secreted by most cell types 31, 32. Exosomes serve as mediators of cell-to-cell communication, which plays an important role in tumor progression, invasion, metastasis and chemoresistance 33, 34. The ncRNA-loaded exosomes serve as mediators to regulate the tumor microenvironment, stemness and chemoresistance of cancer cells 35-37. Recent studies have shown that exosomes are involved in the dynamic crosstalk among CAFs and cancer cells and shape the tumor environment to promote tumor progression and metastasis 38, 39.

Here, we explored the role of H19 in stemness and chemoresistance in CRC. We found that lncRNA 19 could be transferred from CAFs to cancer cells through exosomes, and exosome-enriched H19 promoted the stemness of CSCs and chemoresistance of CRC cells. Therefore, H19 activated the β-catenin pathway as a competing endogenous RNA sponge for miR-141 in CRC, while miR-141 inhibited the stemness of CRC cells. Our findings indicate that H19 expressed by CAFs of the colorectal tumor stroma contributes to tumor development and chemoresistance.

Methods

Patients and tissue samples

Tumor tissues of CRC patients were obtained from the Nanjing General Hospital. For isolation of the primary normal fibroblasts (NFs) and CAFs of CRC patients, 10 paired tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues were collected during the surgery. The sterile fresh CRC tissues and adjacent normal tissues were immediately washed with PBS containing 20% antibiotics. Then, the tissues were digested with collagenase type I (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) and hyaluronidase (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) to isolate the primary NFs and CAFs. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional ethics committee of Medical school of Nanjing University.

RNA sequencing

After the AOM/DSS-induced CAC mouse model was established, the tissues of colons undergoing the carcinoma pathological process were collected and frozen in a -80 °C freezer. Then, we performed whole-genome transcriptome profiling by RNA sequencing. Total RNA extraction, RNA sequencing and bioinformatics data analysis were performed by Novel Bioinformatics (Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). Pathway analysis of the differentially expressed genes from the RNA sequencing results was performed using the KEGG database, and significant pathways were selected by Fisher's exact test. The P-value and FDR were used to define the threshold of significance, and the figures were generated by R language.

Cell culture

Human CRC cell lines (HCT116 and SW480) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, United States) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 ℃ and 5% CO2. For the culture of CAFs and NFs, DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS was used. The FBS used in the study was from Life Technologies (USA). For preparation of the exosome-depleted FBS, FBS was ultracentrifuged at 110,000 ×g for 18 h at 4 °C. The preparation progress occurred under sterile conditions, and the supernatant was collected. In all of the experiments involving exosomes in the study, exosome-depleted FBS was used for cell culture.

Cell counting kit-8 assay

Cell Counting Kit-8 (DOJINDO, Japan) was used for the CCK8 assay, as previously described 40. Briefly, colorectal cancer cells after corresponding treatment in the study were harvested and seeded in 96-well plates (100 μL, 10000/well). To test the cell viability, 10 μL of CCK8 reagent was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Then, the absorption was evaluated by a microplate reader at 450 nm (Tecan, Switzerland).

RNA extraction and reverse transcriptase quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

For total RNA extraction from cells and tissues, TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) was used following the manufacturer's protocol. For cell lysis, the cells were washed with PBS and 1 mL TRIzol was added per well for 3 min. For tissue lysis, the tissues were cut into pieces with scissors and added to a small iron column with 1 mL TRIzol. Then, the samples were ground using a tissue grinder in a pre-cooled environment. To extract the total RNA in exosomes, a miRNeasy Micro Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) was used following the manufacturer's protocol. The concentration and purity of the RNA were evaluated using a spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For qRT-PCR, total reverse transcription was performed first. One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using a cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Takara, Japan). Afterwards, real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Invitrogen, USA) and Step-One Plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, CA). The 2-∆∆CT method was used to evaluate the relative expression. The sequences of primers used in the study are shown in Table S1.

Western blotting

Western blot assays to detect the protein level in cells were performed according to reported protocols 41. The protein concentrations were tested by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, USA). β-catenin, vimentin, α-SMA, HSP70, CD63, GM130, Sox2, Oct4, Nanog, CD44, CD133 and GAPDH antibodies were used in the study. β-catenin, α-SMA, HSP70, CD63, and GM130 antibodies (1:1000) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (MA, USA). CD63 antibody (1:1000) was purchased from Santa Cruz (USA), and vimentin, Sox2, Oct4, Nanog, CD44 and CD133 antibodies (1:500) were purchased from Proteintech Group (Rosemont, USA). The enhanced chemiluminescence reaction was used to detect the protein bands.

Immunofluorescence assays and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Immunofluorescence assays were performed as described in our previous study 42. Cy3-labeled H19 and FISH Kit (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) were used following the manufacturer's instructions 43. A FV10i confocal microscope (OLYMPUS, Japan) was used to capture the images.

AldeRed ALDH detection assay

The AldeRed ALDH Detection Kit (Millipore, USA) was used following the manufacturer's instructions 44. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, Germany).

Exosome isolation

As in our previous study, the differential centrifugation method was used to isolate the exosomes from the culture supernatants 45. Briefly, CAFs or NFs were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% exosome-depleted FBS for 48 h, and culture supernatants were collected. For exosome isolation, the debris and apoptotic bodies in the supernatants were removed first by centrifugation at 2000 ×g (10 min) and 10,000 ×g (30 min). Then, the supernatants were collected and ultracentrifuged at 110,000 ×g for 70 min. Afterwards, the exosomes were washed with sterilized PBS and purified by centrifugation at 110,000 ×g for 1 h. Subsequently, the exosomes were resuspended in PBS and filtered through 0.22 μm filters (Millipore, USA). To measure the total protein concentration of isolated exosomes, Bradford assay (Pierce) was performed.

Exosome characterization

The characterization of exosomes was also demonstrated in our previous study 45. To characterize the morphology of the isolated exosomes, transmission electron microscopy (Hitachi HT7700, Tokyo, Japan) was used. Briefly, the isolated exosomes were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and spotted onto a glow-discharged copper grid on filter paper. Afterwards, the copper grid was dried for 15 min at room temperature. Then, the samples were stained with 2% uranyl acetate and dried for 10 min. Subsequently, the samples were examined at 100 keV. For size distribution of the isolated exosomes, qNano (Izon Science, New Zealand) was used following the manufacturer's instructions. To analyze the protein markers of exosomes, Western blotting assays were performed, and anti-CD63, anti-HSP70 and anti-GM130 antibodies were used.

Transient transfection

H19-specific siRNAs, miRNA mimics and negative controls were synthesized by RiboBio (Guangzhou, China). RNAi negative control was used as a negative control (NC). The targeting sequences of H19 siRNA were as follows: si-H19-1, 5′- GGCCTTCCTGAACACCTTA-3′; si-H19-2, 5′-GACGTGACAAGCAGGACAT-3′, si-H19-3, 5′- CCTCTAGCTTGGAAATGAA-3′; negative control, 5′-UUCUCCGAA-CGUGUCACGUTT-3′. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used for transfection following the manufacturer's instructions.

In vivo studies

For the oxaliplatin resistance model, 5×106 Lv-shC and Lv-shH19 SW480 cells resuspended in 200 μL of ice-cold PBS were injected in each mouse to establish xenografts. The NOD/SCID mice (5 weeks old, male) used in the study were purchased from the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University. To study the role of H19 in oxaliplatin resistance, we randomly divided the mice into four groups (Lv-shC, Lv-shH19, Lv-shC+oxaliplatin, Lv-shH19+oxaliplatin). For oxaliplatin treatment, mice were injected once every 3 days with oxaliplatin (5 mg/kg). The same volume of saline was used as control treatment, and the tumor volume was calculated.

For the in vivo limiting dilution assay, indicated numbers of SW480 cells were suspended in PBS and Matrigel (1:1 ratio) and subcutaneously implanted in the flanks of 5-week-old NOD/SCID mice. After 60 days, tumor formation was examined, and CSC frequency was calculated using the ELDA webtool (http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda).

For the exosome treatment model, 5×106 SW480 cells per mouse were used to establish xenografts. Then, the mice were randomly divided into four groups (Control, OXA, OXA+Exo-NF and OXA+Exo-CAFs). Exosomes (100 µg total protein in 100 μL volume) were injected twice a week in the vicinity of the subcutaneous tumors. The tumor volume was calculated using the formula V = a × b2 / 2, where a is the long axis and b is the short axis. Male NOD/SCID mice (5-6 week) were used in the study. Animals were sacrificed before neoplastic masses reached limit points. All animal work was approved by the Animal Care Committee of Nanjing University in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Luciferase assay

The psicheck2-based luciferase reporter plasmids containing wild-type H19 (psicheck2-H19-wt) and H19 mutated at the putative miR-141 binding sites (psicheck2-H19-mut) were designed and constructed by Generay Biotech (Shanghai, China). HEK293T cells were seeded into 24-well plates and co-transfected with psicheck2-H19-wt plasmids, psicheck2-H19-mut plasmids, miR-141 mimics or mimic controls by Lipofectamine 2000. After 48 h of transfection, the cell lysates were collected and the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) was used to detect the firefly and renilla luciferase activities.

Immunoprecipitation assay

The RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation (RIP) experiment was performed as previously described 46. In brief, the SW480 cells were lysed in RIP lysis buffer and the extracts were collected. Then, RIP buffer containing magnetic beads coated with Ago2 antibody or control IgG antibody (negative control) was added to the extracts and incubated at 4 °C for 4 h. The antibodies were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, USA). After being washed, the immunoprecipitated RNA was isolated by TRIzol reagent and subjected to RT-qPCR. SDS-PAGE was used for detecting the proteins.

Statistical analyses

GraphPad_Prism_5.0 (Graphpad Software Inc.) was used for the statistical analyses. To determine significance between two groups, an unpaired t-test was performed. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate the differences between more than two groups. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

LncRNA H19 is overexpressed in colorectal cancer

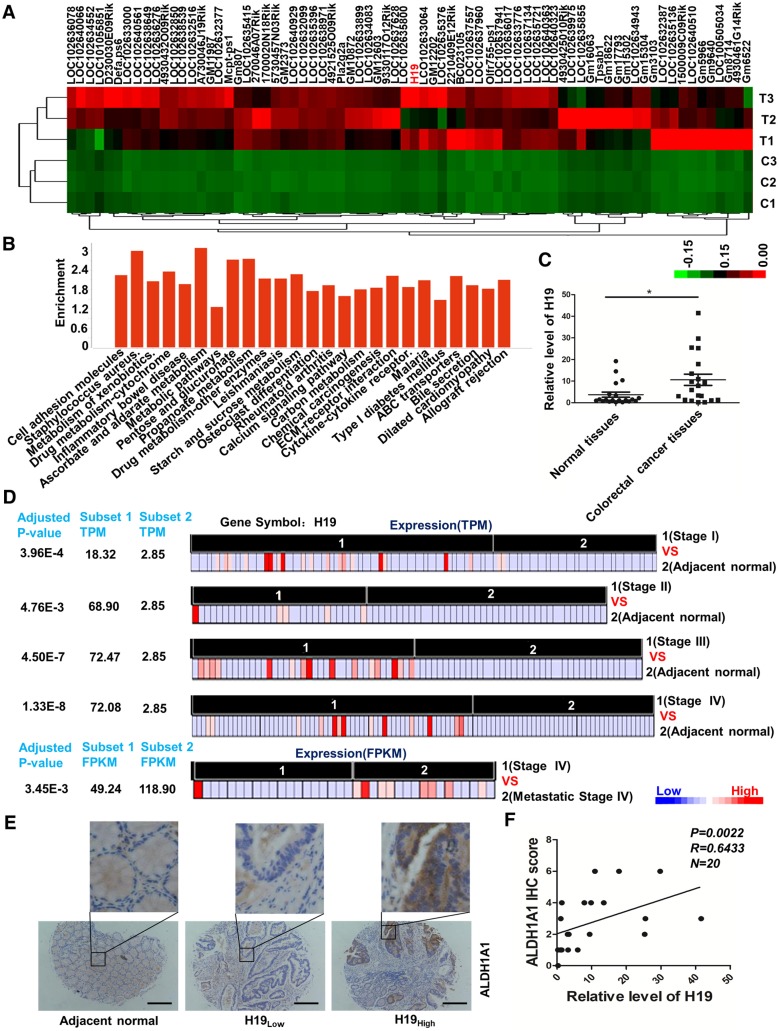

In our previous study, the AOM/DSS-induced CAC mouse model was successfully established, and colon tissues undergoing the pathological process associated with carcinoma were collected 47. We performed whole-genome transcriptome profiling by RNA sequencing and applied an EBseq algorithm to filter the differentially expressed genes. The heat map provided a visual representation of the unregulated lncRNAs in tumor tissues compared with normal colon tissues (Figure 1A and Table S2). Pathway analysis revealed that several critical pathways, including cell adhesion molecules, metabolism of xenobiotics, inflammatory bowel disease and drug metabolism (Figure 1B and Table S3), were involved in the carcinogenesis of the CAC mouse model. Expectedly, the inflammatory bowel disease pathway was significantly activated. Of note, H19 was unregulated 375.16-fold in carcinoma compared with its expression in normal colon tissues (Table S2). H19 is one of the best-known imprinted genes with a secondary RNA structure conserved across lineages 48, 49. H19 has been shown to be up-regulated in CRC tissues and associated with CRC patient survival. In addition, H19 has also been reported to play an important role in epithelial-mesenchymal transition 50 and drug metabolism 51-53. Therefore, H19 was chosen and validated for further exploration. The qRT-PCR results showed increased expression of H19 in tumor tissues from CRC patients (Figure 1C, p = 0.0169).

Figure 1.

LncRNA H19 is overexpressed in colorectal cancer. (A) The differential expression of a set of lncRNAs in colon tissues identified from NGS data is shown in the heat map. In the map, H19 was highly expressed overall, although the expression in T2 was relatively low. (B) The pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed mRNAs is shown. The figure was generated using the R language tool. (C) The expression of H19 in CRC tissues was analyzed by qRT-PCR (n=20, p = 0.0169). (D) The differential expression of H19 in five subsets of different stages (Stage I, Stage II, Stage III, Stage IV and metastatic Stage IV). The expression level is indicated by transcripts per million (TPM) or fragments per kilobase million (FPKM). To obtain the TPM, the expression values (tau values, calculated by RSEM) of TCGA Level 3 RNA-Seq version 2 data sets were multiplied by 106. TPM and RPKM (reads per kilobase million) values were used to standardize the average transcript expression. (E) Representative immunostaining graphs of ALDH1A1 expression in H19-high and H19-low CRC tissues. Scale bar, 200 μm. (F) Correlation between relative H19 level and ALDH1A1 immunostaining scores in CRC tissues with linear regression lines. All representative data are from three independent experiments. Error bars, SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Next, we analyzed RNA-seq data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) of coding transcripts using the bioinformatics tools “Cancer RNA-seq Nexus” (CRN, http://syslab4.nchu.edu.tw/). Specifically, we analyzed the expression of H19 in five subsets of different stages (Stage I, Stage II, Stage III, Stage IV and metastatic Stage IV). In all of these pairs, H19 was significantly overexpressed (adjusted P-values 1.33×10-8 to 4.76×10-3) in cancer subsets (average TPM = 18.32-72.47) with respect to normal subsets (average TPM = 2.85). The results indicated that the level of H19 was significantly increased as a whole in early stages and increased with the development of CRC (Stage I, Stage II and Stage III). In addition, the expression of H19 was also higher in metastatic Stage IV compared to its expression in non-metastatic Stage IV cases (Figure 1D).

The CRC specimens in our study were stratified into two categories, H19-high and H19-low CRC groups, with the median H19 expression value as the cutoff. Further analysis of CRC specimens demonstrated that H19 expression correlated with immunostaining scores of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 (ALDH1A1) in corresponding specimens (Figure 1E-F; p = 0.0022, R = 0.6433). As ALDH1A1 has been reported as a cancer stem cell marker in CRC 54, this result indicates that H19 might be associated with the stemness of CRC stem cells.

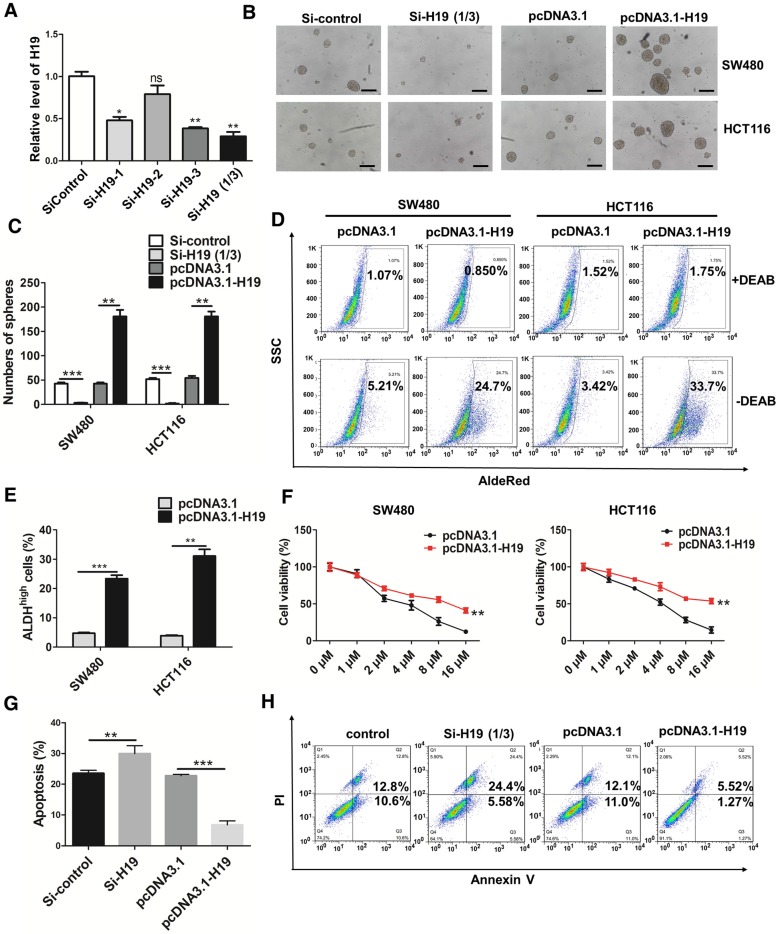

LncRNA H19 promotes the stemness and oxaliplatin resistance of colorectal cancer

To further ascertain the role of H19 in the stemness of CRC, we knocked down or overexpressed H19 in CRC cells. Three siRNA sequences designed to target H19 were used to knock down H19 expression, and si-H19 was selected for further use in our study (Figure 2A). As shown in Figure 2B-C, the knockdown of H19 significantly decreased the sphere-propagating capacity, while the overexpression of H19 enhanced the sphere-propagating capacity in colon cancer cells (both SW480 and HCT116 cells). As high intracellular ALDH enzyme activity serves as a universal marker of CRC stem cells 55, 56, we also performed AldeRed ALDH detection assays to assess the populations of ALDH1high cancer cells. H19 overexpression significantly increased the populations of ALDH1high cells (Figure 2D-E). Moreover, H19 overexpression enhanced the expression of pluripotency transcription factors (Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2) and several CSC markers (Figure S1). As CSCs have been reported to be relatively resistant to chemotherapy, we assessed the chemosensitivity of CRC cells by conventional and widely used chemotherapeutic agents (oxaliplatin). H19 overexpression markedly contributed to oxaliplatin resistance in SW480 and HCT116 cells (Figure 2F). The cell apoptosis assay confirmed that the oxaliplatin resistance of SW480 cells was further enhanced by overexpression of H19 (Figure 2G-H).

Figure 2.

H19 promotes the stemness and oxaliplatin resistance of colorectal cancer. (A) SW480 cells were transfected with three small interfering RNAs. The level of H19 in the SW480 cells after transfection was analyzed by qRT-PCR. The H19 in SW480 was significantly knocked down by si-H19-1 and si-H19-3 transfection. (B-C) SW480 and HCT116 cells were transfected with si-control, mixture of si-H19-1 and si-H19-3, pcDNA3.1 or pcDNA3.1-H19, and the knockdown of H19 significantly decreased the capacity to form spheres. Representative images are presented. Scale bars, 200 µm. (D-E) The SW480 and HCT116 cells were transfected with si-control, mixture of si-H19-1 and si-H19-3, pcDNA3.1 or pcDNA3.1-H19, and an AldeRed ALDH detection assay was performed. Representative images are presented; the ALDH1high cell population was increased by H19 overexpression and decreased by knockdown of H19. (F) H19 was overexpressed in SW480 and HCT116 cells, which were then treated with different concentrations of oxaliplatin (0 μM, 1 μM, 2 μM, 4 μM, 8 μM and 16 μM) for 24 h for the CCK8 assay. H19 overexpression promoted oxaliplatin resistance. (G-H) Expression of H19 were inhibited or overexpressed in SW480 cells. Then, cells were treated with 4 μM oxaliplatin for 48 h. Flow cytometry was used to analyze cell apoptosis. H19 overexpression decreased the cell apoptosis induced by oxaliplatin. All representative data are from three independent experiments. Error bars, SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

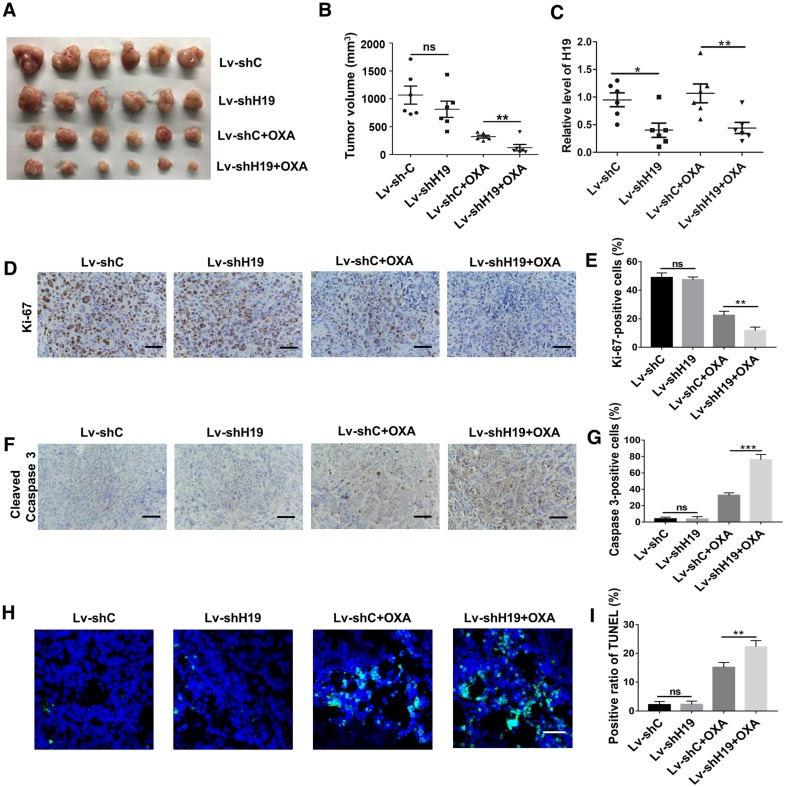

To further ascertain the role of H19 in promoting CSC-like characteristics, we performed limiting dilution assays. As shown in Table 1, the frequency of tumor-initiating cells was significantly decreased by knocking down H19. We also established a xenograft model by stably knocking down H19 in SW480 cells (Lv-shH19) and investigated the role of H19 in tumor growth and oxaliplatin resistance. As shown in Figure 3A-B, knocking down H19 significantly inhibited tumor growth under the treatment of oxaliplatin, while knocking down H19 without oxaliplatin treatment had no effect on tumor growth. The expression of H19 in tumor tissues of the xenograft models was confirmed, as shown in Figure 3C. Furthermore, knocking down H19 also decreased the expression of Ki-67 (Figure 3D-E) and increased the expression of cleaved Caspase-3 (Figure 3F-G). In addition, knocking down H19 increased the apoptotic index in tumor tissues (Figure 3H-I). Together, H19 promoted the stemness and oxaliplatin resistance of CRC.

Table 1.

Tumorigenic capacity of Lv-shC and Lv-shH19 SW480 cells in NOD/SCID mice.

| Cell Dose | Tumor-Initialing-Frequency (95% Confidence Interval) |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells | 105 | 104 | 103 | 102 | ||

| Lv-shC | 5/5 | 3/5 | 1/5 | 0/5 | 1/9338 (1/3306-1/26376) | 0.000312 |

| Lv-shH19 | 2/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 1/14632 (1/44878-1/477460) | |

Figure 3.

H19 promotes oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer in vivo. H19 stable knockdown (Lv-shH19) and control (Lv-shC) SW480 cells were used to establish a xenograft model. Mice were treated with vehicle or oxaliplatin (5 mg/kg). (A-B) The changes of tumor volume were monitored and shown (n=6 per group). Knocking down H19 significantly inhibited the tumor growth under oxaliplatin treatment. (C) The level of H19 in tumor tissues of the indicated group was analyzed by qRT-PCR, and the level of H19 in tumor tissues was knocked down. (D-E) Immunohistochemistry analysis of Ki-67 protein levels in xenograft tumor tissues; the knockdown of H19 decreased the expression of Ki-67. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F-G) Immunohistochemistry analysis of cleaved Caspase-3 protein levels in xenograft tumor tissues; cleaved Caspase-3 was decreased by knockdown of H19. Scale bar, 50 μm. (H-I) TUNEL apoptosis assay analysis of cell apoptosis in tumor tissues. Scale bar, 25 μm. Error bars, SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

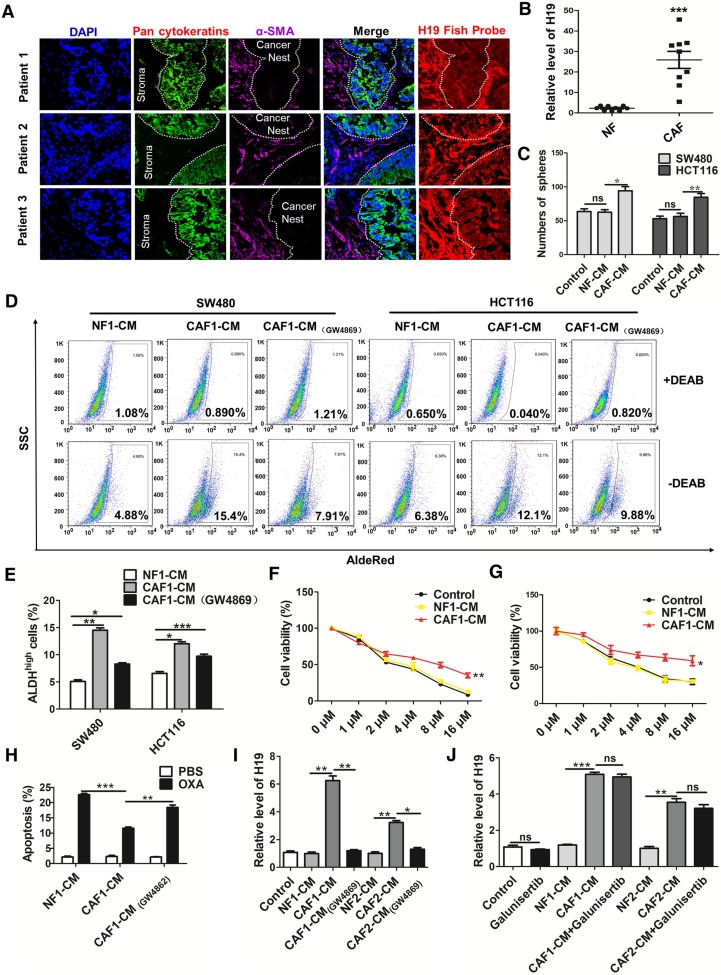

LncRNA H19 is highly expressed in the CAFs of the colorectal cancer stroma

To explore the origin and role of H19 in CRC, we assessed the expression of H19 in both cancer nests (pan-CK-positive) and tumor stroma (α-SMA-positive) by RNA-FISH and immunofluorescence assays. Intriguingly, although both the cancer nest and tumor stroma exhibited high H19 levels, H19 was more highly expressed in tumor stroma than in cancer nests (Figure 4A). To further confirm the expression of H19 in tumor stroma, we isolated CAFs and NFs from CRC tissues and adjacent normal tissues. To identify the purity and phenotype of isolated NFs and CAFs, fibroblast biomarkers were tested. In CAFs, the expression of CAF-specific genes, including fibroblast activation protein (FAP), fibroblast specific protein 1 (FSP1), alpha-smooth muscle actin (ACTA2) and CD90, were markedly unregulated compared to the expression in NFs (Figure S2A). Immunofluorescence staining assays confirmed the cellular morphology and marker of the isolated fibroblast populations (NFs and CAFs) (Figure S2B). Both the isolated NFs and CAFs were found to express vimentin, while the expression of a myofibroblast marker (α-SMA) was only found in CAFs (Figure S2C). Surprisingly, we found higher levels of H19 in CAFs compared to the expression in NFs (Figure 4B). Therefore, H19 was more highly expressed in the CAFs of tumor stroma cells than in those of CRC cells. These findings suggested a hypothesis that the stemness and oxaliplatin resistance of CRC may be ascribed to overexpression of H19 in CAFs of the CRC microenvironment.

Figure 4.

CAF-derived exosomes might be involved in the enhanced expression of H19, stemness and oxaliplatin resistance of colorectal cancer cells. (A) In situ analysis with Cy3-labeled RNA using an H19 FISH probe in CRC tissues. The scale bar represents 50 μm. CRC tissues were also stained with pancytokeratins (cancer nest) and α-SMA (stroma) by immunofluorescence assay. (B) qRT-PCR analyzed the level of H19 in isolated CAFs and NFs. SW480 and HCT116 cells were cultured under conditioned medium derived from NFs (NF-CM) and CAFs (CAF-CM) for 4 days. (C) The capacity of cells to form spheres was assessed. Measurements were taken digitally, and mammospheres were quantified using six pictures per well. The mean number of mammospheres >75 μm was counted and shown. (D) CAF cells were treated with GW4869, and the conditioned medium was collected. CAF1-CM (GW4869) represents the conditioned medium of CAF cells treated with GW4869. The SW480 and HCT116 cells were cultured under NF-CM, CAF-CM and CAF1-CM (GW4869) for 4 days. The AldeRed ALDH detection assay was performed to detect the intracellular ALDH enzyme activity. The ALDH1high population was defined as cells showing a right shift in fluorescence in the absence of DEAB. (E) The percentage of the ALDH1high cancer cell population. (F-G) SW480 and HCT116 cells were cultured under NF-CM and CAF-CM for 4 days. Cells were treated with different concentrations of oxaliplatin (0 μM, 1 μM, 2 μM, 4 μM, 8 μM and 16 μM) for 24 h, and cell viability was measured by CCK8. (H) SW480 cells were cultured under NF-CM and CAF-CM for 4 days. Cells were then treated with 4 μM oxaliplatin for 48 h, and cell apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry. (I) SW480 cells were cultured under NF-CM, CAF-CM and CAF1-CM (GW4869) for 4 days. The level of H19 was analyzed by qRT-PCR. (J) SW480 cells were pretreated with 10 μM galunisertib or PBS and were then treated with NF-CM, CAF-CM and CAF1-CM (GW4869) for 4 days. Levels of H19 in cells were analyzed. All representative data are from three independent experiments. Error bars, SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

CAFs enhances the level of H19, stemness and oxaliplatin resistance of colorectal cancer cells

To assess whether CAFs regulate the CSC-like characteristics of CRC cells, we treated human CRC cells with conditioned medium derived from NFs (NF-CM) and CAFs (CAF-CM). CAF-CM treatment strikingly increased the sphere-propagating capacity compared with NF-CM treatment, while there was no difference between the NF-CM and control group (Figure 4C and Figure S2D). Moreover, CAFs acquired from other CRC patients showed a similar effect on CRC cells (Figure S3). Previous studies reported that exosomes were transferred from stromal to breast cancer cells and contributed to drug and radiation resistance 57. We hypothesized that exosomes might contribute to the enhanced sphere-forming capacities of CRC cells. To investigate the role of exosomes, an exosome inhibitor (GW4869) was used to block exosome secretion. As shown in Figure 4D-E, CAF-CM treatment significantly enhanced the populations of ALDH1high cancer cells, while GW4869 reversed this effect. Those results indicated that exosomes released by CAFs might enhance the stemness of CRC cells. On the other hand, CAF-CM treatment significantly enhanced cell viability of CRC cells (Figure 4F-G) and decreased oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis, while cell apoptosis was increased along with the blockage of exosome secretion from CAFs by GW4869 (Figure 4H). These data indicated that CAFs might induce inherent resistance to chemotherapeutic agents through secretion of exosomes.

We further analyzed the level of H19 in SW480 cells after CAF-CM and NF-CM treatment. The results showed that CAF-CM treatment increased the level of H19 compared to the expression in the NF-CM group (Figure 4I). In contrast, CAF-CM with blockage of exosome secretion could not increase the level of H19 in SW480 cells (Figure 4I). H19 has been shown to be induced by TGF-β in CRC 58, and CAFs have been found to secrete TGF-β to promote vascular mimicry formation 59. We wondered whether TGF-β was involved in the increased H19 level of CRC cells induced by CAFs. Therefore, we blocked the TGF-β pathway with galunisertib (an inhibitor of TGF-β receptor I). As shown in Figure 4J, the blockage of TGF-β receptor I in SW480 cells did not decrease H19 expression under CAF-CM treatment. Together, these data indicated that CAF-derived exosomes, rather than TGF-β secreted by CAFs, might be involved in the enhanced expression of H19, stemness and oxaliplatin resistance in CRC cells.

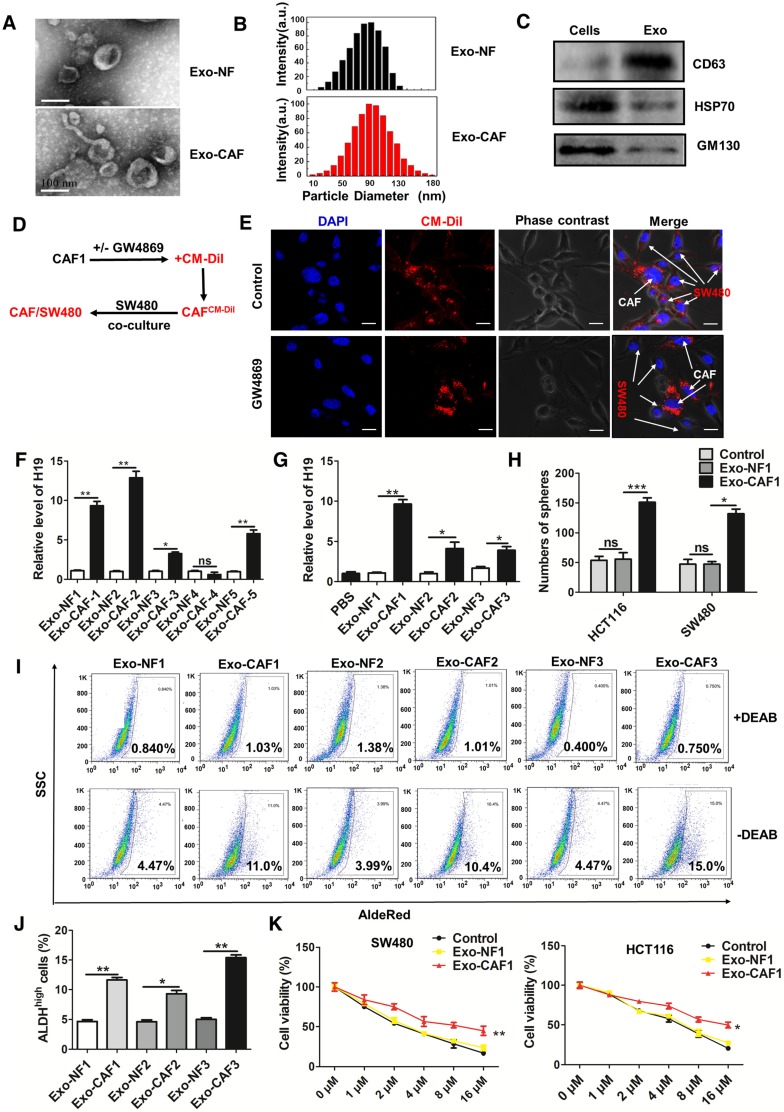

CAF-derived exosomes transfer lncRNA H19 to colorectal cancer cells

To further confirm the role of CAF-derived exosomes, we purified exosomes from the conditioned medium derived from CAFs and NFs. Both the isolated exosomes exhibited typical lipid bilayer membrane encapsulation, cup-shaped morphology, size, and number (Figure 5A-B). The isolated exosomes also positively expressed exosome protein markers, including CD63 and Hsp70 (Figure 5C). The GW4869 or vehicle pre-treated CAFs were labeled with CM-Dil and co-cultured with SW480 cells for 18 h. Immunofluorescence was used to analyze the distribution of CM-Dil in cells (Figure 5D). As shown in Figure 5E, more Dil-positive SW480 cells were observed under co-culture with vehicle pre-treated CAFs compared with the number observed in GW4869 cells pre-treated with CAFs that secreted fewer exosomes. The results indicated that the SW480 cells could effectively ingest CAF-derived exosomes. Furthermore, we analyzed the level of H19 in the isolated exosomes and found that exosomes derived from CAFs of CRC patients showed higher levels of H19 than the exosomes derived from corresponding NFs (Figure 5F). Expectedly, incubation with exosomes from CAFs significantly increased the intracellular levels of H19 in SW480 and HCT116 cells. However, exosomes derived from NF cells could not increase the levels of H19 in SW480 or HCT116 cells (Figure 5G and Figure S4A). Together, these results indicated that H19 was enriched in CAF-derived exosomes and could be transferred from CAFs to CRC cells.

Figure 5.

CAF-derived exosomes transfer H19 to colorectal cancer cells. (A) The representative images of exosomes derived from CAFs and NFs analyzed by transmission electron microscopy. Scale bar, 100 nm. (B) The size distribution of the isolated exosomes was analyzed by nanoparticle tracking analysis. (C) Western blotting analysis for exosomal markers CD63, Hsp70 and GM130 of SW480 cells and exosomes derived from CAF cells. (D-E) CAFs were pre-treated with or without GW4869. Then, the CAFs were labeled with CM-Dil (red) and co-cultured with SW480 for 18 h. Immunofluorescence analyzed the distribution of CM-Dil in cells. Scale bars, 20 µm. (F) qRT-PCR analyzed the level of H19 in the isolated exosomes derived from CAFs and NFs of five patients. (G) The SW480 cells were incubated with indicated exosomes or PBS for 48 h, and the level of H19 was analyzed by qRT-PCR. (H) The SW480 and HCT116 were incubated with exosomes (10 µg/mL from CAFs or NFs for 24 h, and the capacity of cells to form spheres was assessed. Measurements were taken digitally, and mammospheres were quantified using six pictures per well. The mean number of mammospheres >75 μm was counted and shown. (I-J) SW480 cells were incubated with exosomes (10 µg/mL) from CAFs or NFs from three patients for 48 h, and AldeRed ALDH detection assay was performed. (K) SW480 and HCT116 cells were incubated with exosomes (10 µg/mL) from CAFs or NFs from three patients for 24 h. Cells were then treated with different concentrations of oxaliplatin (0 μM, 1 μM, 2 μM, 4 μM, 8 μM and 16 μM) for 24 h, and the cell viability was measured by CCK8. All representative data are from three independent experiments. Error bars, SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To assess the effect of exosomes on stemness and oxaliplatin resistance, CRC cells were incubated with exosomes from CAFs or NFs. As shown in Figure 5H and Figure S4B-D, the cancer cells displayed higher sphere formation ability with incubation of CAF-derived exosomes than exosomes from NFs. Exosomes from CAFs significantly enhanced the populations of ALDH1high cells compared to exosomes from NFs (Figure 5I-J). Furthermore, exosomes from CAFs promoted resistance to oxaliplatin in SW480 and HCT116 cells (Figure 5K).

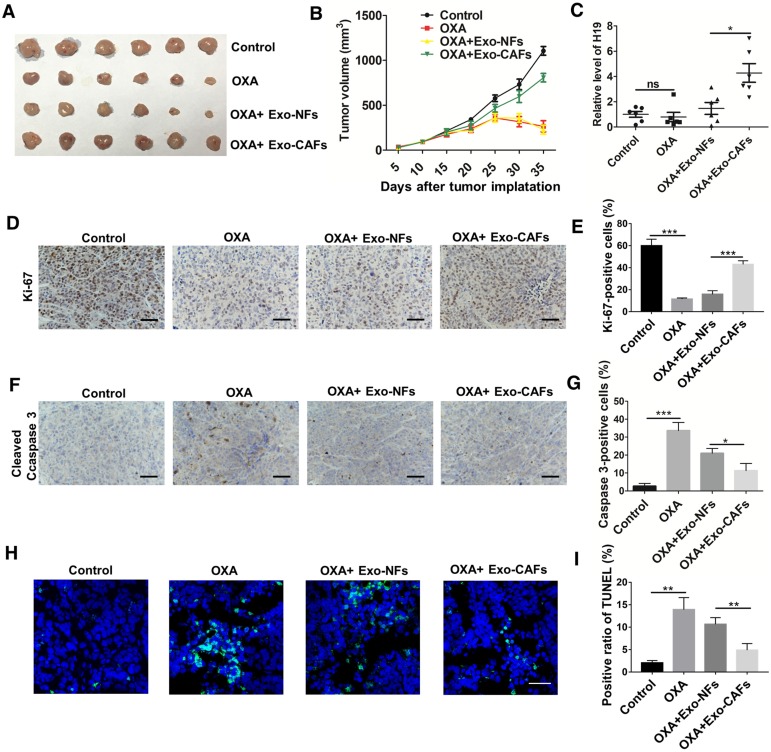

To further investigate the role of CAF-derived exosomes in vivo, we established a xenograft model. As shown in Figure 6A-B, oxaliplatin treatment inhibited tumor growth, while treatment with CAF-exosomes significantly promoted tumor growth and reversed the antitumor effect of oxaliplatin. Moreover, treatment with CAF-exosomes also increased the proliferation marker Ki-67 and decreased the level of cleaved Caspase-3 induced by oxaliplatin (Figure 6D-G). TUNEL apoptosis assays showed that CAF-exosomes decreased the oxaliplatin-induced cell apoptosis (Figure 6H-I). These results were consistent with the H19 in vivo data. Furthermore, CAF-exosome treatment increased the level of H19 in tumor tissues compared with NF-exosome treatment (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

CAF-derived exosomes transfer H19 to CRC cells and promote tumor growth and oxaliplatin resistance in vivo. (A-B) Subcutaneous xenografts were established in nude mice, which were treated with vehicle or oxaliplatin (5 mg/kg). In the exosome groups, the mice were injected with the indicated exosomes. The changes of tumor volume were monitored and shown (n = 6 per group). (C) The level of H19 in tumor tissues was analyzed by qRT-PCR and was increased by CAF-exosome treatment compared with NF-exosome treatment. (D-E) Immunohistochemistry analysis of Ki-67 protein levels in xenograft tumor tissues. Treatment with CAF-exosomes increased the expression of Ki-67 under treatment with oxaliplatin. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F-G) Immunohistochemistry analysis of cleaved Caspase-3 protein levels in xenograft tumor tissues. Scale bar, 50 μm. Treatment with CAF-exosomes decreased the protein expression of cleaved Caspase-3 under the treatment of oxaliplatin. (H-I) TUNEL apoptosis assay analysis of cell apoptosis in tumor tissues. Scale bar, 25 μm. Error bars, SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

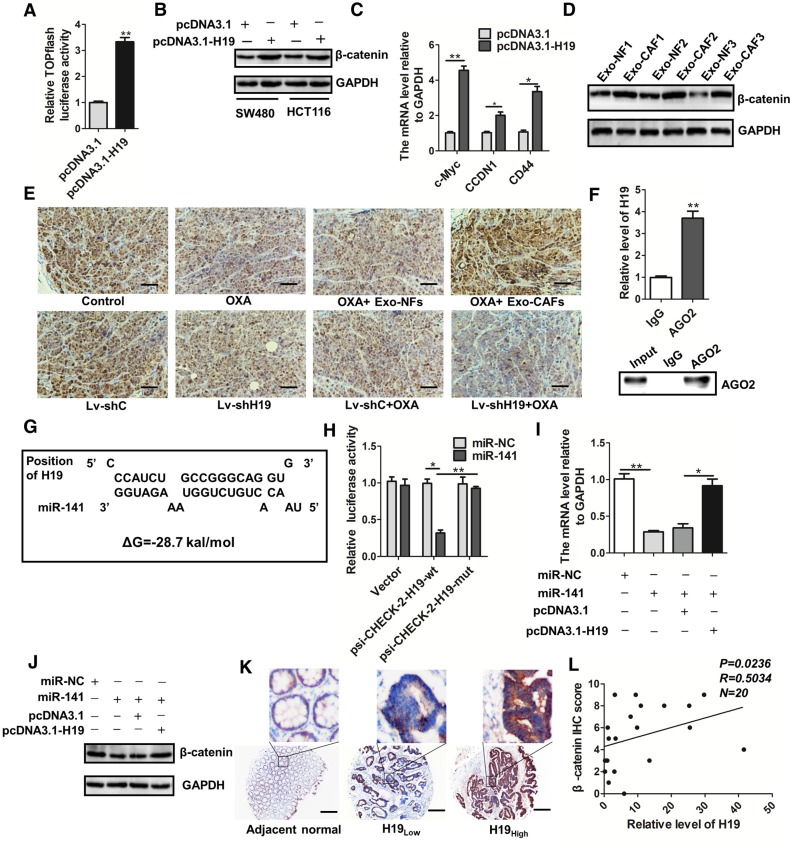

H19 activates the β-catenin pathway via acting as a competing endogenous RNA sponge for miR-141 in colorectal cancer

Given that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is critical for the capability of intestinal stem cells 60-62, the maintenance of CSCs 63, 64 and the chemoresistance of cancer cells 65-67, we wondered whether the Wnt/β-catenin pathway was regulated by H19 in CRC. We found that overexpression of H19 promoted Wnt luciferase reporter (TOPFlash) activity (Figure 7A) and significantly increased the protein level of β-catenin (Figure 7B). Overexpression of H19 also enhanced the expression of the downstream genes of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Figure 7C). Furthermore, CAF-exosomes significantly enhanced the protein level of β-catenin in SW480 cells (Figure 7D). We also analyzed the expression of β-catenin in tumor tissues in our established xenograft model. As shown in Figure 7E, treatment with CAF-exosomes significantly increased the protein level of β-catenin compared to treatment with NF-exosomes, while knocking down H19 decreased the β-catenin level. Together, these results indicated that exosomal H19 activated the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in CRC. Further data showed that H19 could regulate many biological processes as an endogenous sponge for miRNAs. RNA immunoprecipitation analysis showed that H19 was elevated in AGO2-containing miRNPs compared with its expression in control IgG immunoprecipitates (Figure 7F). Next, we confirmed that H19 could functionally interact with miRNAs in CRC cells. Sequence analysis and bioinformatics prediction analysis showed the putative-binding sites between H19 and miR-141 (Figure 7G), suggesting that H19 had ceRNA potential for miR-141. MiR-141, a member of the miR-200 cluster, targets β-catenin and suppresses the Wnt/β-catenin pathway 68-71. Previous studies have reported that miR-141 plays an important role in the stemness and chemosensitivity of CSCs 72-75. MiR-141 suppresses prostate cancer stem cells and metastasis via regulating pro-metastasis genes 73. The mammosphere and tumor-initiating capacity of breast cancer cells were increased by knockdown of miR-141 74. Here, we found that the stemness of CRC cells was significantly suppressed by miR-141. The overexpression of miR-141 significantly decreased the sphere-forming capacities of SW480 and HCT116 cells (Figure S5A-B), and the overexpression of miR-141 abolished the induction of ALDH1high cells by H19 overexpression (Figure S5C-D).

Figure 7.

H19 activates the β-catenin pathway by acting as a competing endogenous RNA sponge for miR-141 in colorectal cancer. (A) H19 was overexpressed by transfection with the pcDNA3.1-H19 plasmid, and luciferase experiments with Top-Luc Flash reporter and pRL-TK (as an internal control) were performed to analyze the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. (B) Western blotting assessed the level of β-catenin in SW480 and HCT116 cells after indicated treatments. (C) The expression of the downstream genes of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (c-myc, CCND1 and CD44) was analyzed qRT-PCR. (D) SW480 cells were treated with exosomes (10 µg/mL) derived from CAFs or NFs for 48 h, and Western blotting analyzed the protein level of β-catenin. (E) Immunohistochemistry analysis of β-catenin levels in two xenograft tumor tissues in Figure 4 and Figure 6. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F) Immunoprecipitation using anti-AGO2 antibody (lane 3) or IgG (lane 2) followed by Western blot analysis. Immunoprecipitated RNA was isolated by TRIzol reagent, and the level of H19 was analyzed by qRT-PCR. (G) The putative binding sites between H19 and miR-141 were predicted. (H) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with luciferase plasmids (psicheck2 vector, psicheck2-H19-wt, psicheck2-H19-mut) and miR-141 mimics or mimic controls, and dual-luciferase reporter gene assays were performed. (I) The mRNA levels of β-catenin were analyzed by qRT-PCR. The SW480 cells were transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3.1), H19-overexpressing plasmids (pcDNA3.1-H19), miR-NC (mimic control) or miR-141 (mimic), and mRNA levels of β-catenin were analyzed by qRT-PCR. (J) The protein levels of β-catenin were analyzed by Western blotting in SW480 cells transfected with plasmids overexpressing H19 (pcDNA3.1-H19), an empty vector (pcDNA3.1), miR-NC (mimic control) or miR-141 (mimic). (K) Representative immunostaining graphs of β-catenin expression in H19-high and H19-low CRC tissues. Scale bar, 200 μm. (L) Correlation between relative H19 level and β-catenin immunostaining scores in CRC tissues with linear regression lines. Data are shown as the means ± SD from three independent experiments. Error bars, SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We therefore investigated the relationship between H19 and miR-141. To confirm the putative binding site of H19 and miR-141, we performed dual-luciferase reporter assays. As shown in Figure 7H, miR-141 transfection significantly reduced the luciferase activities of the H19-wt reporter but did not affect the activities of the reporter containing mutated H19. We also confirmed that β-catenin was a target of miR-141 in CRC cells and that H19 regulated the expression of β-catenin by interacting with miR-141 (Figure 7I-J). Further analysis of CRC specimens demonstrated that H19 expression was positively correlated with immunostaining scores of β-catenin in corresponding specimens (Figure 7K-L; p = 0.0236, R = 0.5034). Overall, our findings demonstrate that H19 activated the β-catenin pathway via acting as a competing endogenous RNA sponge for miR-141 in CRC.

Discussion

In the present study, the conserved H19 was found to be highly expressed in the tissues of CAC mice and CRC under different TNM stages. We found that H19 enhanced the stemness and oxaliplatin resistance of CRC cells in both in vitro and in vivo assays. Importantly, differential expression of H19 in cancer nests and tumor stroma was found, which indicated that H19 might be involved in the crosstalk between tumor stroma cells and CRC cells in the tumor microenvironment.

The present study demonstrated, for the first time to our knowledge, that CAFs expressed significantly higher levels of H19 than NFs and that CAFs transferred the lncRNA H19 to neighboring CRC cells. As the main infiltrated non-lymphocytes in tumor stroma, CAFs promote tumor cell proliferation, cell invasion, angiogenesis and chemoresistance by secreting a secretome that includes CAF-specific proteins, cytokines and extracellular matrix 6-8. As is well known, periostin, expressed by fibroblasts in normal tissue and primary tumors, promotes the metastasis of breast tumors by enhancing breast CSC maintenance 76. Our results showed that CAFs promoted the stemness of CRC cells via activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. This observation is in accordance with previous findings that tumor cells preferentially located close to stromal myofibroblasts have high Wnt signaling activity 77. Moreover, we found that CAFs activated the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway of CRC cells by secreting H19-containing exosomes.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays an important role in biological processes including normal development, stem cell self-renewal and differentiation, and tumorigenesis 78, 79. Abnormal activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is the initiating and driving event underlying the vast majority of CRC tumorigenesis 80, 81. The constitutive transactivation of β-catenin represents a primary initiator of intestinal stem cell transformation and an initial event in CRC 82, 83. Collective data suggest that hyperactivated Wnt signaling is essential for maintaining the tumor-initiating potential or CSC characteristics of CRC 4, 63, 64. In the current study, CAFs promoted CSC characteristics by transferring exosomal H19. We found that H19 overexpression promoted the Wnt luciferase report (TOPFlash) activity and significantly increased the protein level of β-catenin. As expected, the exosomes derived from CAFs showed a similar effect on the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

The CSCs of CRC are involved in tumor recurrence, metastasis and chemoresistance. The properties of CSCs were enhanced by the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, resulting in the initiation of CRC and resistance to chemotherapy 63, 64. In NSCLC, the overactivation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling induced by miR-128-3p enhanced the stemness-like properties and promoted chemoresistance-associated metastasis 65. In CRC, KDM3 family histone demethylases promoted the growth and chemoresistance of human colorectal CSCs by activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling 66. Correspondingly, the inhibition of Wnt activity in a pharmacological or genetic manner restores the chemosensitivity of DNA-alkylating drugs in human medulloblastoma 67. In both in vivo and in vitro assays, both CAF-derived exosomes and H19 promoted the oxaliplatin resistance of CRC cells by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

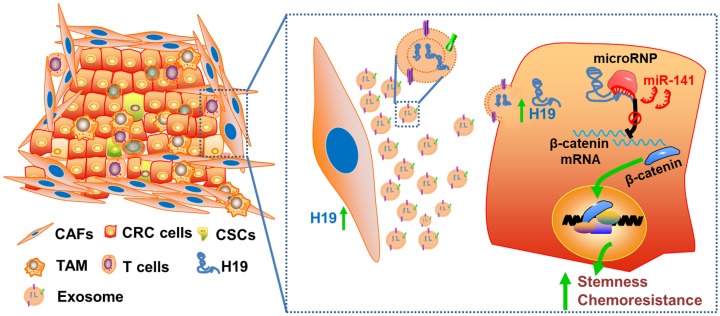

Collectively, we characterized the roles of lncRNA H19 and CAFs in CRC stemness and oxaliplatin resistance and delineated the underlying molecular mechanism by which CAF-derived exosomes activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling by transferring exosomal H19 (Figure 8). This study has deepened our understanding of the occurrence of colorectal cancer, the maintenance of colorectal cancer stemness and the tolerance of chemotherapy drugs, as well as provided new ideas and targets for the clinical treatment of colorectal cancer. In addition, our findings highlight the potential for a therapeutic strategy in which therapies targeting CAFs, lncRNA H19 or Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the CRC microenvironment may synergize with chemotherapeutic drugs to increase treatment efficacy.

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of the crosstalk between CAFs and cancer cells in the tumor microenvironment. Exosomes derived from CAFs were transferred to CRC cells. H19 was highly expressed in CAFs and enriched in the CAF-derived exosomes. H19 could activate the β-catenin pathway via acting as a competing endogenous RNA sponge for miR-141 in CRC, while miR-141 significantly inhibited the stemness of CRC cells.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31570909 to Y.H and 81772542 to T.W.) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province in China (BK20161400 to T.W.).

Abbreviations

- ALDH

aldehyde dehydrogenase

- ACTA2

alpha-smooth muscle actin

- CAC

colitis-associated cancer

- CAFs

carcinoma-associated fibroblasts

- CAF-CM

conditioned medium derived from CAFs

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- CSCs

colorectal cancer stem cells

- FAP

fibroblast activation protein

- FSP1

fibroblast specific protein 1

- LncRNAs

long non-coding RNAs

- NFs

normal fibroblasts

- NF-CM

conditioned medium derived from NFs

- RNA-FISH

rna-fluorescence in situ hybridization

- RIP

rna-binding protein immunoprecipitation

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

References

- 1.Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2014;383:1490–502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Punt CJ, Tol J. More is less combining targeted therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:731–3. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brabletz T, Jung A, Spaderna S, Hlubek F, Kirchner T. Opinion: migrating cancer stem cells - an integrated concept of malignant tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:744–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clevers H. The cancer stem cell: premises, promises and challenges. Nat Med. 2011;17:313–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clevers H. The intestinal crypt, a prototype stem cell compartment. Cell. 2013;154:274–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Au Yeung CL, Co NN, Tsuruga T, Yeung TL, Kwan SY, Leung CS. et al. Exosomal transfer of stroma-derived miR21 confers paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer cells through targeting APAF1. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11150. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitadai Y. Cancer-stromal cell interaction and tumor angiogenesis in gastric cancer. Cancer Microenviron. 2010;3:109–16. doi: 10.1007/s12307-009-0032-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeung TL, Leung CS, Wong KK, Samimi G, Thompson MS, Liu J. et al. TGF-beta modulates ovarian cancer invasion by upregulating CAF-derived versican in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5016–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen WJ, Ho CC, Chang YL, Chen HY, Lin CA, Ling TY. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts regulate the plasticity of lung cancer stemness via paracrine signalling. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3472. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lacina L, Plzak J, Kodet O, Szabo P, Chovanec M, Dvorankova B. et al. Cancer microenvironment: what can we learn from the stem cell niche. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:24094–110. doi: 10.3390/ijms161024094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beermann J, Piccoli MT, Viereck J, Thum T. Non-coding RNAs in development and disease: background, mechanisms, and therapeutic approaches. Physiol Rev. 2016;96:1297–325. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prensner JR, Chinnaiyan AM. The emergence of lncRNAs in cancer biology. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:391–407. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang F, Zhang L, Huo XS, Yuan JH, Xu D, Yuan SX. et al. Long noncoding RNA high expression in hepatocellular carcinoma facilitates tumor growth through enhancer of zeste homolog 2 in humans. Hepatology. 2011;54:1679–89. doi: 10.1002/hep.24563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmitt AM, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs incancer pathways. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:452–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang JF, Guo YJ, Zhao CX, Yuan SX, Wang Y, Tang GN. et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx)-related long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) down-regulated expression by HBx (Dreh) inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by targeting the intermediate filament protein vimentin. Hepatology. 2013;57:1882–92. doi: 10.1002/hep.26195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan JH, Yang F, Wang F, Ma JZ, Guo YJ, Tao QF. et al. A long noncoding RNA activated by TGF-beta promotes the invasion-metastasis cascade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:666–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ. et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464:1071–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prensner JR, Iyer MK, Sahu A, Asangani IA, Cao Q, Patel L. et al. The long noncoding RNA SChLAP1 promotes aggressive prostate cancer and antagonizes the SWI/SNF complex. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1392–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung CL, Wang LY, Yu YL, Chen HW, Srivastava S, Petrovics G. et al. A long noncoding RNA connects c-Myc to tumor metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:18697–702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415669112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pachnis V, Belayew A, Tilghman SM. Locus unlinked to alpha-fetoprotein under the control of the murine raf and Rif genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:5523–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.17.5523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabory A, Jammes H, Dandolo L. The H19 locus: role of an imprinted non-coding RNA in growth and development. Bioessays. 2010;32:473–80. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Venkatraman A, He XC, Thorvaldsen JL, Sugimura R, Perry JM, Tao F. et al. Maternal imprinting at the H19-Igf2 locus maintains adult haematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Nature. 2013;500:345–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui H, Onyango P, Brandenburg S, Wu Y, Hsieh CL, Feinberg AP. Loss of imprinting in colorectal cancer linked to hypomethylation of H19 and IGF2. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6442–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ariel I, Miao HQ, Ji XR, Schneider T, Roll D, de Groot N. et al. Imprinted H19 oncofetal RNA is a candidate tumour marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Pathol. 1998;51:21–5. doi: 10.1136/mp.51.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hibi K, Nakamura H, Hirai A, Fujikake Y, Kasai Y, Akiyama S. et al. Loss of H19 imprinting in esophageal cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:480–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berteaux N, Lottin S, Monte D, Pinte S, Quatannens B, Coll J. et al. H19 mRNA-like noncoding RNA promotes breast cancer cell proliferation through positive control by E2F1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29625–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504033200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han D, Gao X, Wang M, Qiao Y, Xu Y, Yang J. et al. Long noncoding RNA H19 indicates a poor prognosis of colorectal cancer and promotes tumor growth by recruiting and binding to eIF4A3. Oncotarget. 2016;7:22159–73. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohtsuka M, Ling H, Ivan C, Pichler M, Matsushita D, Goblirsch M. et al. H19 noncoding RNA, an independent prognostic factor, regulates essential Rb-E2F and CDK8-beta-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer. EBioMedicine. 2016;13:113–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsang WP, Ng EK, Ng SS, Jin H, Yu J, Sung JJ. et al. Oncofetal H19-derived miR-675 regulates tumor suppressor RB in human colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:350–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarzenbach H. Biological and clinical relevance of H19 in colorectal cancer patients. EBioMedicine. 2016;13:9–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mateescu B, Kowal EJ, van Balkom BW, Bartel S, Bhattacharyya SN, Buzas EI. et al. Obstacles and opportunities in the functional analysis of extracellular vesicle RNA - an ISEV position paper. J Extracell Vesicles. 2017;6:1286095. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2017.1286095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramirez MI, Amorim MG, Gadelha C, Milic I, Welsh JA, Freitas VM. et al. Technical challenges of working with extracellular vesicles. Nanoscale. 2018;10:881–906. doi: 10.1039/c7nr08360b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L, Li C, Wang S, Wang Z, Jiang J, Wang W. et al. Exosomes derived from hypoxic oral squamous cell carcinoma cells deliver miR-21 to normoxic cells to elicit a prometastatic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2016;76:1770–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan Q, Yang L, Zhang X, Peng X, Wei S, Su D. et al. The emerging role of exosome-derived non-coding RNAs in cancer biology. Cancer Lett. 2018;414:107–15. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fatima F, Ekstrom K, Nazarenko I, Maugeri M, Valadi H, Hill AF. et al. Non-coding RNAs in mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: deciphering regulatory roles in stem cell potency, inflammatory resolve, and tissue regeneration. Front Genet. 2017;8:161. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2017.00161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nawaz M. Extracellular vesicle-mediated transport of non-coding RNAs between stem cells and cancer cells: implications in tumor progression and therapeutic resistance. Stem Cell Investig. 2017;4:83. doi: 10.21037/sci.2017.10.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fatima F, Nawaz M. Vesiculated Long non-coding RNAs: Offshore packages deciphering trans-regulation between cells, cancer progression and resistance to therapies. Non-coding RNA. 2017;3:10. doi: 10.3390/ncrna3010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fatima F, Nawaz M. Stem cell-derived exosomes: roles in stromal remodeling, tumor progression, and cancer immunotherapy. Chin J Cancer. 2015;34:541–53. doi: 10.1186/s40880-015-0051-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luga V, Zhang L, Viloria-Petit AM, Ogunjimi AA, Inanlou MR, Chiu E. et al. Exosomes mediate stromal mobilization of autocrine Wnt-PCP signaling in breast cancer cell migration. Cell. 2012;151:1542–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, Liu R, Yang F, Cheng R, Chen X, Cui S. et al. miR-19a promotes colorectal cancer proliferation and migration by targeting TIA1. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:53. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0625-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren J, Nie Y, Lv M, Shen S, Tang R, Xu Y. et al. Estrogen upregulates MICA/B expression in human non-small cell lung cancer through the regulation of ADAM17. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:768–76. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ren J, Ding L, Xu Q, Shi G, Li X, Li X. et al. LF-MF inhibits iron metabolism and suppresses lung cancer through activation of P53-miR-34a-E2F1/E2F3 pathway. Sci Rep. 2017;7:749. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00913-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jin C, Jia L, Huang Y, Zheng Y, Du N, Liu Y. et al. Inhibition of lncRNA MIR31HG promotes osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cells. 2016;34:2707–20. doi: 10.1002/stem.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gauck D, Keil S, Niggemann B, Zanker KS, Dittmar T. Hybrid clone cells derived from human breast epithelial cells and human breast cancer cells exhibit properties of cancer stem/initiating cells. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:515. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3509-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song Y, Dou H, Li X, Zhao X, Li Y, Liu D. et al. Exosomal miR-146a contributes to the enhanced therapeutic efficacy of interleukin-1beta-primed mesenchymal stem cells against sepsis. Stem Cells. 2017;35:1208–21. doi: 10.1002/stem.2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jain R, Devine T, George AD, Chittur SV, Baroni TE, Penalva LO. et al. RIP-Chip analysis: RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation-microarray (Chip) profiling. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;703:247–63. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-248-9_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang T, Xu X, Xu Q, Ren J, Shen S, Fan C. et al. miR-19a promotes colitis-associated colorectal cancer by regulating tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3-NF-kappaB feedback loops. Oncogene. 2017;36:3240–51. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Juan V, Crain C, Wilson C. Evidence for evolutionarily conserved secondary structure in the H19 tumor suppressor RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1221–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.5.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hurst LD, Smith NG. Molecular evolutionary evidence that H19 mRNA is functional. Trends Genet. 1999;15:134–5. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lv M, Zhong Z, Huang M, Tian Q, Jiang R, Chen J. lncRNA H19 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of bladder cancer by miR-29b-3p as competing endogenous RNA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1864:1887–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li X, Liu R, Yang J, Sun L, Zhang L, Jiang Z. et al. The role of long noncoding RNA H19 in gender disparity of cholestatic liver injury in multidrug resistance 2 gene knockout mice. Hepatology. 2017;66:869–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.29145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen S, Bu D, Ma Y, Zhu J, Chen G, Sun L. et al. H19 Overexpression Induces Resistance to 1,25(OH)2D3 by targeting VDR through miR-675-5p in colon cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2017;19:226–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cai B, Ma W, Bi C, Yang F, Zhang L, Han Z. et al. Long noncoding RNA H19 mediates melatonin inhibition of premature senescence of c-kit(+) cardiac progenitor cells by promoting miR-675. J Pineal Res. 2016;61:82–95. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Minn I, Wang H, Mease RC, Byun Y, Yang X, Wang J. et al. A red-shifted fluorescent substrate for aldehyde dehydrogenase. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3662. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Balber AE. Concise review: aldehyde dehydrogenase bright stem and progenitor cell populations from normal tissues: characteristics, activities, and emerging uses in regenerative medicine. Stem Cells. 2011;29:570–5. doi: 10.1002/stem.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Douville J, Beaulieu R, Balicki D. ALDH1 as a functional marker of cancer stem and progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:17–25. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boelens MC, Wu TJ, Nabet BY, Xu B, Qiu Y, Yoon T. et al. Exosome transfer from stromal to breast cancer cells regulates therapy resistance pathways. Cell. 2014;159:499–513. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liang WC, Fu WM, Wong CW, Wang Y, Wang WM, Hu GX. et al. The lncRNA H19 promotes epithelial to mesenchymal transition by functioning as miRNA sponges in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:22513–25. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang J, Lu Y, Lin YY, Zheng ZY, Fang JH, He S. et al. Vascular mimicry formation is promoted by paracrine TGF-beta and SDF1 of cancer-associated fibroblasts and inhibited by miR-101 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2016;383:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan KS, Janda CY, Chang J, Zheng GXY, Larkin KA, Luca VC. et al. Non-equivalence of Wnt and R-spondin ligands during Lgr5(+) intestinal stem-cell self-renewal. Nature. 2017;545:238–42. doi: 10.1038/nature22313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Janda CY, Dang LT, You C, Chang J, de Lau W, Zhong ZA. et al. Surrogate Wnt agonists that phenocopy canonical Wnt and beta-catenin signalling. Nature. 2017;545:234–7. doi: 10.1038/nature22306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Farin HF, Jordens I, Mosa MH, Basak O, Korving J, Tauriello DV. et al. Visualization of a short-range Wnt gradient in the intestinal stem-cell niche. Nature. 2016;530:340–3. doi: 10.1038/nature16937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Masuda M, Uno Y, Ohbayashi N, Ohata H, Mimata A, Kukimoto-Niino M. et al. TNIK inhibition abrogates colorectal cancer stemness. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12586. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang X, Jung YS, Jun S, Lee S, Wang W, Schneider A. et al. PAF-Wnt signaling-induced cell plasticity is required for maintenance of breast cancer cell stemness. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10633. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cai J, Fang L, Huang Y, Li R, Xu X, Hu Z. et al. Simultaneous overactivation of Wnt/beta-catenin and TGFbeta signalling by miR-128-3p confers chemoresistance-associated metastasis in NSCLC. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15870. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li J, Yu B, Deng P, Cheng Y, Yu Y, Kevork K. et al. KDM3 epigenetically controls tumorigenic potentials of human colorectal cancer stem cells through Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15146. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wickstrom M, Dyberg C, Milosevic J, Einvik C, Calero R, Sveinbjornsson B. et al. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway regulates MGMT gene expression in cancer and inhibition of Wnt signalling prevents chemoresistance. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8904. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tian Y, Pan Q, Shang Y, Zhu R, Ye J, Liu Y. et al. MicroRNA-200 (miR-200) cluster regulation by achaete scute-like 2 (Ascl2): impact on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colon cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:36101–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.598383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liang WC, Fu WM, Wang YB, Sun YX, Xu LL, Wong CW. et al. H19 activates Wnt signaling and promotes osteoblast differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20121. doi: 10.1038/srep20121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abedi N, Mohammadi-Yeganeh S, Koochaki A, Karami F, Paryan M. miR-141 as potential suppressor of beta-catenin in breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:9895–901. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3738-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qiu W, Kassem M. miR-141-3p inhibits human stromal (mesenchymal) stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:2114–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mateescu B, Batista L, Cardon M, Gruosso T, de Feraudy Y, Mariani O. et al. miR-141 and miR-200a act on ovarian tumorigenesis by controlling oxidative stress response. Nat Med. 2011;17:1627–35. doi: 10.1038/nm.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu C, Liu R, Zhang D, Deng Q, Liu B, Chao HP. et al. MicroRNA-141 suppresses prostate cancer stem cells and metastasis by targeting a cohort of pro-metastasis genes. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14270. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Finlay-Schultz J, Cittelly DM, Hendricks P, Patel P, Kabos P, Jacobsen BM. et al. Progesterone downregulation of miR-141 contributes to expansion of stem-like breast cancer cells through maintenance of progesterone receptor and Stat5a. Oncogene. 2015;34:3676–87. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu C, Kelnar K, Vlassov AV, Brown D, Wang J, Tang DG. Distinct microRNA expression profiles in prostate cancer stem/progenitor cells and tumor-suppressive functions of let-7. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3393–404. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Malanchi I, Santamaria-Martinez A, Susanto E, Peng H, Lehr HA, Delaloye JF. et al. Interactions between cancer stem cells and their niche govern metastatic colonization. Nature. 2011;481:85–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vermeulen L, De Sousa EMF, van der Heijden M, Cameron K, de Jong JH, Borovski T. et al. Wnt activity defines colon cancer stem cells and is regulated by the microenvironment. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:468–76. doi: 10.1038/ncb2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cadigan KM, Nusse R. Wnt signaling: a common theme in animal development. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3286–305. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, Barker N, Clevers H, Vogelstein B. et al. Activation of beta-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in beta-catenin or APC. Science. 1997;275:1787–90. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Giles RH, van Es JH, Clevers H. Caught up in a Wnt storm: Wnt signaling in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1653:1–24. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(03)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Groden J, Thliveris A, Samowitz W, Carlson M, Gelbert L, Albertsen H. et al. Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Cell. 1991;66:589–600. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goss KH, Groden J. Biology of the adenomatous polyposis coli tumor suppressor. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1967–79. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.9.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.