Abstract

This study compared temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) patients with amygdala lesion (AL) without hippocampal sclerosis (HS) (TLE-AL) with patients with TLE and HS without AL (TLE-HS). Both subtypes of TLE arose from the right hemisphere.

The TLE-AL group exhibited a lower Working Memory Index (WMI) on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, third edition (WAIS-III), indicating that the amygdala in the right hemisphere is involved in memory-related function. [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission topography (FDG-PET) showed glucose hypometabolism limited to the right uncus for the TLE-AL group.

The results suggest the importance of considering cognitive functions in the non-dominant hemisphere to prevent impairment after surgery.

Keywords: Amygdala lesion, Temporal lobe epilepsy, Cognitive functions, Working memory

Highlights

-

•

Low working memory index (WMI) was found due to a right amygdala lesion (AL).

-

•

Glucose hypometabolism was limited to the right uncus for the Temporal Lobe Epilepsy-AL (TLE-AL) patients

-

•

Glucose hypometabolism was associated with low WMI in the TLE-AL patients

-

•

We suggest the need to consider cognitive function in non-dominant hemisphere

1. Introduction

The most common cause of drug-resistant mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is hippocampal sclerosis (HS) [1], [2], [3]. Epileptogenesus originating from the pathological hippocampus, however, often involve the amygdala that is anatomically adjacent to the hippocampus [4]. For example, Graebenitz and his colleague reported that epileptiform network of TLE with HS involved the amygdala [5]. In some cases, amygdala sclerosis coexists with HS in patients with TLE [6]. Wieser, furthermore, reported a patient with amygdala epilepsy without HS [7]. Recent reports have indicated that enlargement of the amygdala without HS can be epileptogenic [8], [9], [10].

As for the characteristics of seizures, both similarities and differences between the TLE with amygdala lesion (AL) without HS (TLE-AL) and TLE with HS without AL (TLE-HS) are more or less understood [8], [11]. Reports regarding interictal conditions also exist. Tebartz van Elst and his colleagues reported an association between bilateral amygdala enlargement with affective disorders in some patients with TLE [12]. Some researchers reported memory impairment associated with HS in TLE-HS [13], [14]. To our knowledge, however, neither systematic investigation on the effects of unilateral amygdala lesion nor report that deals with effects of AL on cognitive functions in TLE-AL exists. Hence, functional influence of both TLE-AL and TLE-HS are still to be delineated, particularly in the interictal state.

The main function of hippocampus is memory formation. The main function of the amygdala, by contrast, is considered to be related to emotion and drives, and not memory itself. The amygdala plays a role in memory enhancement in emotional conditions. The amygdala is also related to olfaction and autonomic control mediated by connection with the olfactory bulb, hypothalamic and brainstem centers [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. A lesion in the hippocampus, therefore, is considered to be associated with memory impairment. As for lesions in the amygdala, however, no report so far demonstrated a clear implication of memory impairment.

In the present study, we intended to clarify the effects of the right amygdala lesion on higher order functions and explore whether the amygdala lesion causes deficits of cognitive function among drug-resistant TLE-AL in comparison with TLE-HS. The right hemisphere typically tends to be regarded as not crucial in language-related functions because the left hemisphere is usually dominant for speech. Understanding the functions and roles of such brain areas as the amygdala and hippocampus in the non-dominant hemisphere, however, is still incomplete, and thus, this study also explores the aspect of cognitive functions in the non-dominant hemisphere.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Subjects

Among patients with drug-resistant TLE in an epilepsy surgery program at National Epilepsy Center, Shizuoka Institute of Epilepsy and Neurological Disorders between 2007 and 2013, 148 patients were diagnosed with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy in the right hemisphere based on multimodal preoperative evaluation. Before admission to the surgery program, psychiatrists saw each patient to confirm that the patient had no psychiatric contraindications to epilepsy surgery.

The studies used for the diagnosis of TLE included ictal and interictal scalp video-EEG, 1.5-Tesla MR images, and Iomazenil-SPECT. Iomazenil-SPECT was included as a standard clinical procedure based on its usefulness [20], [21]. Video-EEG confirmed clinical features of the seizures with impaired awareness within the category suggestive of mesial TLE [22]. Interictal Iomazenil-SPECT showed decreased perfusion unilaterally in the right mesial temporal area compared with the left.

The 148 consecutive patients were then screened based on inclusion criteria for amygdala lesion (AL) without hippocampal sclerosis (TLE-AL) and for hippocampal sclerosis (HS) without AL (TLE-HS). They were required to be left hemisphere language-dominant confirmed by intracarotid-propofol (Wada) test, to be between 15 and 50 years old at surgery, to be a native speaker of Japanese, to have no neurological or psychiatric disorders other than epilepsy, and to possess preoperative Full Scale IQ > 80. In the MRI evaluation for TLE-AL, we confirmed that fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images showed no hyperintensity and volume increase in the right amygdala compared with the left, and no difference in the right and the left hippocampus in terms of signal intensity and volume. In MRI evaluation for TLE-HS, we confirmed that FLAIR images showed hyperintensity and volume decrease in the right hippocampus compared with the left without any abnormality in bilateral amygdalae. The inclusion criteria found 12 TLE-AL patients and the first 12 consecutive TLE-HS patients.

All patients were taking anti-seizure drugs at the time of evaluation. Of the twelve patients in the TLE-AL group, three were treated with monotherapy consisting of carbamazepine, one with levetiracetam, and the remaining eight with 2 or 3 drugs, including carbamazepine, valproate, levetiracetam, zonisamide, phenobarbital, gabapentin, or clobazam. All twelve patients in the TLE-HS group were treated with more than 2 drugs out of the drugs mentioned above, at the time of evaluation.

In statistical imaging studies of [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), 19 right-handed healthy volunteers (mean age ± SD, 34.1 ± 4.6; 9 females) recruited for the present study also participated as normal controls.

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Epilepsy Center, Shizuoka Institute of Epilepsy and Neurological Disorders, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Neuropsychological and imaging studies

The TLE patients, both with AL without HS (TLE-AL) and with HS without AL (TLE-HS), took the Japanese version of two standardized neuropsychological tests, Wechsler Adult Intelligent Scale, third edition (WAIS-III) [23] and Wechsler Memory Scale, revised (WMS-R) [24]. The WAIS-III, designed to evaluate global cognitive functioning and specific domains of cognition, provides four index scores. The WMS-R provides four memory-related index scores. Since these evaluations were conducted as part of presurgical examination, the objective was cross-sectional study at a specific point in time, between 3 and 6 months before surgery.

Eight out of 12 subjects in each patient group who gave informed consent for PET study and 19 normal controls underwent 18F-FDG PET by using Discovery ST Elite PET scanner (GE Healthcare Japan, Tokyo). They received an intravenous injection of 3.7 MBq/kg 18F-FDG and were scanned after a 60-min bed rest. The patients had no seizure at least for 12 h before the PET scan. Positron count was acquired in 128 × 128 matrix (5.47 × 5.47 × 3.27 mm) and reconstructed in VUE Point Plus (3D-OSEM) procedure (GE Healthcare Japan) with post Gaussian filter of 2.19 mm. Slice thickness of reconstructed images was 3.27 mm with FOV of 256 mm. Anatomical T1-weighted MR images of each subject were acquired on a 1.5 Tesla Signa HDxt Optima Edition Twin Speed system (GE Healthcare Corporate) with 3D fast spoiled gradient-recall (FSPGR) sequence (TR = 7.856 ms, TE = 2.996 ms, FOV = 24.0 cm, 1.3 mm slice thickness, 124 slices). Before group analysis, an experienced radiologist (KM) inspected the FDG-PET images of each patient and confirmed unilateral glucose hypometabolism in the right temporal area. The inspection of the FDG-PET and anatomical MR images of each normal control found no abnormality.

2.3. Analysis

2.3.1. Demographic and neuropsychological data

Demographic data of the TLE-AL and TLE-HS groups were compared by using t-test and Fisher's exact test. Cognitive performance of the patients was compared between the TLE-AL and TLE-HS groups by using eight index scores obtained from WAIS-III and WMS-R. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to test the null hypothesis between groups. For multiple comparisons, p-value adjusted by the Bonferroni method (p < 0.00625) was considered statistically significant. Subtest scaled scores of WAIS-III and WMS-R were also compared between the two groups. Analyses were conducted with SPSS version 19.0 (IBM).

2.3.2. Imaging data

We evaluated differences in glucose metabolism between TLE-AL group and the normal control (NC) group between TLE-HS group and NC group, and between TLE-AL group and TLE-HS group, using parametric mapping software SPM 8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm8/). Individual FDG-PET images were co-registered with his/her structural T1-weighted MR images, spatially normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space, and smoothed with an 8-mm full-width and half maximal (FWHM) Gaussian kernel. Whole brain voxel-wise group comparison was conducted for the TLE-AL vs. the NC and the TLE-HS vs. the NC. A two-sample t-test was performed to find regions with glucose hypometabolism. Statistically significant clusters corrected for Familywise Error (FWE) (T value > 5.45; voxel per cluster > 64 for TLE-AL vs. NC, T value > 5.48; voxel per cluster > 60 for TLE-HS vs. NC) (p < 0.05, FWE corrected) were anatomically referenced by using Talairach Client [25], and Anatomy Toolbox version 2.1 implemented in SPM 8 [26].

2.3.3. Correlation between cognitive and imaging data

To investigate the relation between cognitive test results and localized glucose hypometabolism in each patient, we evaluated the severity of regional glucose hypometabolism of each patient using three-dimensional stereotactic surface projections software (3D-SSP, AZE, Tokyo) [27]. The same NC data that we used in SPM 8 analysis were used as the normal database for 3D-SSP. After spatial normalization, each patient's radiotracer uptake at each 3D pixel was compared with the corresponding 3D pixel in the NCNormal database. The comparison was quantified as numerical Z-score:

Extent of glucose hypometabolism in each gyrus was analyzed using a stereotactic extraction estimation method (SEE) [28], which automatically yielded the ratio of 3D pixels of glucose hypometabolism within each classified anatomical structure. For the classification of anatomical structures, SEE applied the definition of Talairach Daemon database [25]. SEE also showed the severity of decreased glucose metabolism in each anatomical structure by means of Z-score. We defined a severity score of each patient as his/her Z-score multiplied by his/her extent ratio of 3D pixels.

Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to assess for association between index scores and severity scores after the test of normality (Shapiro–Wilk). Analyses were conducted with SPSS version 19.0 (IBM).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and neuropsychological characteristics of the patients

Table 1 shows the clinical features of two groups of TLE patients. Although the two groups of patients (TLE-AL and TLE-HS), as a whole, showed similarities in terms of clinical and demographic characteristics, the two groups differed in pathological aspects. In the TLE-AL group, surgical pathology analysis found hamartoma (10 patients), low-grade glioma (one patient), and dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor (one patient). HS was totally absent in this group. In the TLE-HS group, surgical pathology analysis in all patients confirmed the total absence of AL.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients.

| Characteristics | TLE-AL group | TLE-HS group | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender total (male/female) | 12 (4/8) | 12(5/7) | 0.67 |

| Age (years) at seizure onset | 20.7(10.9) | 14.5(4.9) | 0.09 |

| Age at operation (years) | 30.9(10.5) | 32.9(8.6) | 0.62 |

| Education (years) | 14.0(1.9) | 15.0(1.3) | 0.17 |

| Pathology (n) | Hamartoma (10) Low-grade glioma (1) DNT (1) |

HS (12) |

Values are mean (1SD), if not specified.

AL: amygdala lesion; DNT: dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor.

HS: hippocampal sclerosis; TLE: temporal lobe epilepsy.

Numerical variables were evaluated by t test.

Nominal variables were evaluated by Fisher's exact test.

Table 2 shows the means of index scores of the two groups. Working Memory Index (WMI) was significantly lower in the TLE-AL group. The other three index scores of WAIS-III and all index scores of WMS-R exhibited no remarkable difference between the two groups.

Table 2.

Means (1SDs) of index scores in WAIS-III and WMS-R between the TLE-AL and TLE-HS groups.

| Group | TLE-AL |

TLE-HS |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of index | (n = 12) | (n = 12) | ||

| WAIS-III | ||||

| Verbal comprehension | 93.1 (8.0) | 99.4 (13.1) | 0.148 | |

| Perceptual organization | 95.5 (11.4) | 101.6 (8.4) | 0.173 | |

| Working memory | 92.1 (8.1) | 104.9 (15.8) | 0.006 | |

| Processing speed | 94.4 (12.1) | 95.6 (12.3) | 0.817 | |

| WMS-R | ||||

| Verbal memory | 101.0(11.2) | 105.5(14.6) | 0.543 | |

| Visual memory | 106.1 (7.6) | 104.6 (9.2) | 0.816 | |

| Attention/concentration | 98.8(11.9) | 108.4(16.6) | 0.093 | |

| Delayed recall | 98.6(14.1) | 98.9(10.4) | 0.908 | |

Norms = 100 (15).

AL = amygdala lesion; HS = hippocampal sclerosis; TLE = temporal lobe epilepsy.

WAIS-III = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, third edition, Japanese version.

WMS-R = Wechsler Memory Scale, revised, Japanese version.

3.2. Imaging studies with FDG-PET

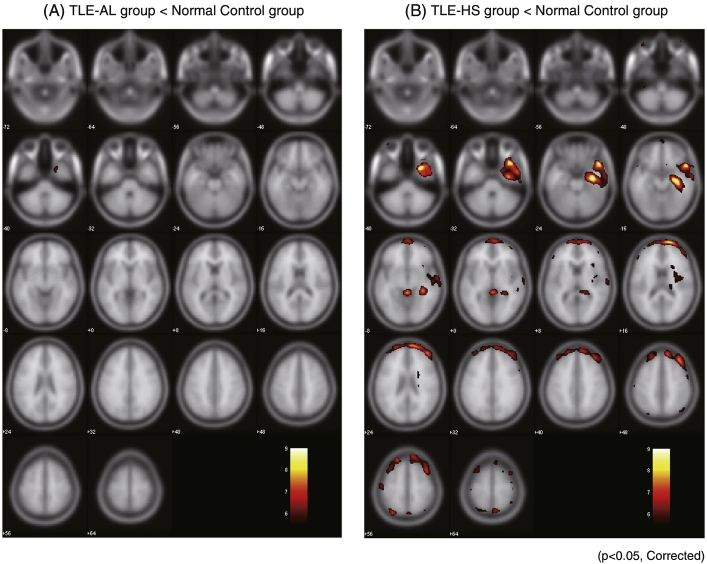

Fig. 1 shows the whole brain statistical analysis of the TLE-AL vs. NC (Fig. 1, panel (A)) and that of the TLE-HS vs. NC (Fig. 1, panel (B)). Compared with the Control group, the TLE-AL group showed significant glucose hypometabolism in a limited region of the right medial temporal lobe. Size of the cluster was 98 voxels (T > 5.45) (p < 0.05, corrected) and the MNI coordinate with maximum T was (20, 8, − 36), which was identified as the uncus by Talairach Client (Table 3). In the cluster, 18 voxels was identified as the entorhinal cortex by Anatomy toolbox software. The right amygdala per se showed glucose hypometabolism in uncorrected analysis (26 voxels, T > 3.45) (p < 0.01, uncorrected) but not in the corrected analysis. No significant hypometabolism was observed in the hippocampus.

Fig. 1.

Regional glucose hypometabolism in the TLE-AL group (panel (A)) and the TLE-HS group (panel (B)). Each group was compared with a group of 19 adult healthy volunteers (normal control group, NC). Regions with glucose hypometabolism were displayed above a critical threshold of t = 5.0 in red/yellow (p < 0.05, FWE corrected). Numbers in axial brain images indicate distance (mm) from anterior commissure-posterior commissure plane.

Table 3.

Brain regions showing decrease in glucose metabolism in TLE-AL and TLE-HS groups.

| Cluster size (voxels) | T value of the peak | Peak coordinate (MNI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | Anatomical region | |||

| Comparison with controls | ||||||

| TLE-AL | 98 | 6.46 | 20 | 8 | − 36 | Right uncus |

| TLE-HS | 7479 | 9.22 | 28 | 14 | − 38 | Right superior temporal gyrus BA38 |

| 7539 | 6.1 | 44 | 50 | 24 | Right middle frontal gyrus | |

AL = amygdala lesion; HS = hippocampal sclerosis; TLE = temporal lobe epilepsy.

BA = Brodmann area.

The TLE-HS group showed extensive significant hypometabolism in the right temporal lobe including the hippocampus and the amygdala. Size of cluster was 7479 voxels (T > 5.48) (p < 0.05, corrected) and the MNI coordinate with maximum T was (28, 14, − 38). The TLE-HS group also showed glucose hypometabolism in the right frontal lobe (Fig. 1, panel (B), and Table 3).

The comparison between the two patient groups confirmed that the TLE-AL group had no region with statistically significant lower glucose metabolism compared with the TLE-HS group.

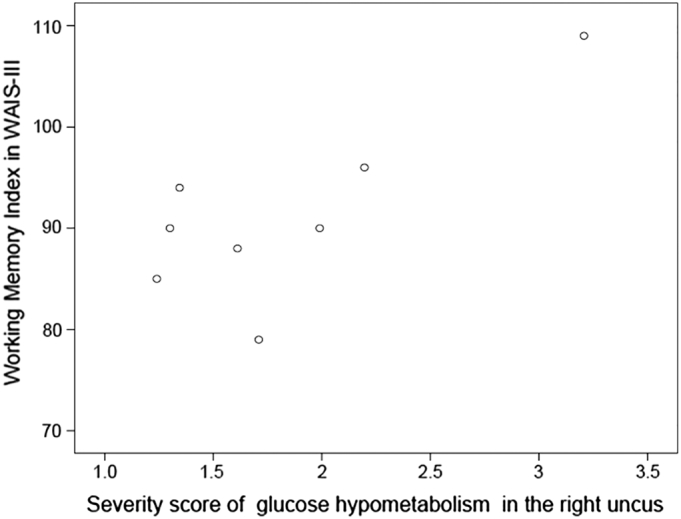

3.3. Correlation between neuropsychological index scores and glucose hypometabolism

In a whole brain map of each TLE-AL patient obtained from 3D-SSP SEE method, we focused on the glucose metabolism in the right uncus of each patient, the only region that showed significant glucose hypometabolism in the group analysis. In the right uncus, the extent ratio of 3D pixels which showed glucose hypometabolism varied among the patients, ranging from 0.62 to 1.00 (1.00 means whole structure involved) and also the Z-score, ranging from 1.30 to 3.46 (Z > 0.00 means glucose hypometabolism). We plotted the working memory index (WMI) of WAIS-III by the severity score of each patient. Pearson's correlation coefficient showed that the severity scores of glucose hypometabolism in the right uncus were related with WMI (r = 0.772, p = 0.025) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Working Memory Index of WAIS-III plotted by severity score of glucose hypometabolism in the right uncus. Severity score of each patient is defined as his/her Z-score multiplied by his/her extent ratio of 3D pixels. The Z-score and extent ratio of 3D pixels were obtained by 3D-SSP SEE method. The blank circles in the figure show patients with TLE-AL (n = 8).

4. Discussion

4.1. Impaired working memory in TLE-AL

The present study investigated whether amygdala lesion (AL) in the right hemisphere affects cognitive functions among patients with drug-resistant TLE. We compared TLE patients with AL with those with hippocampal sclerosis (HS).

WAIS-III and WMS-R test results tabulated in Table 2 revealed that the means of three out of four index scores of WAIS-III (Verbal Comprehension, Perceptual Organization and Processing Speed) and of all four index scores of WMS-R were in the average range for the TLE-AL group. The result also exhibited that seven out of eight index scores showed no significant difference between the TLE-AL group and TLE-HS group. These findings suggest that the pathology in the right medial temporal structures has no differential effect on cognitive functions in terms of these seven aspects.

Working Memory Index (WMI) in WAIS-III for the TLE-AL group, however, was lower than that of the TLE-HS group. The result that only one of eight indexes recognizably lower in the TLE-AL group implies that amygdala lesion in the right hemisphere of patients with drug-resistant TLE may preferentially impair the ability relating to working memory.

4.2. Metabolic state in amygdala

Results in the statistical group analysis of FDG-PET in the TLE-AL group (Fig. 1(A)) revealed that the right hippocampus of TLE-AL showed no glucose hypometabolism. As for the right amygdala of the TLE-AL group, the data showed glucose hypometabolism to some extent compared with the NC group that exhibited no glucose hypometabolism. The TLE-HS group (Fig. 1(B)), by contrast, demonstrated significant hypometabolism in the right mesial temporal lobe, including the hippocampus and the amygdala.

Based on the data shown in Fig. 2, there existed some correlation between WMI of WAIS-III and the severity scores of glucose hypometabolism in the right uncus. Since the number of patients in this study is limited (as described in the latter Section 4.4), there might be a possibility that some of the data points look to be outliers. If, for instance, a data point at the uppermost corner (severity score, WMI = 3.2, 109) was supposed to be excluded, Pearson's correlation coefficient would show no statistical significance. However, to provide sufficient number of data to prove statistical distribution is out of the scope of this report.

The result of this study is more or less in agreement with the report by Takaya and his colleagues [10]. Our finding, however, differed in the extent of glucose hypometabolism in the amygdala and its surrounding area. Takaya and his colleagues found glucose hypometabolism in a broad area including the amygdala, temporal pole, anterior part of the basal temporal area, and bilateral dorsolateral part of the thalamus. The TLE-AL group in the present study, by contrast, showed glucose hypometabolism only in the limited area of the right uncus. Although our result is unable to disclose the causes, we suppose that the strong projections from the amygdala to the uncus [29], [30] may be related.

4.3. Role of amygdala in cognition (possible mechanisms)

The amygdala has been regarded as a crucial structure for emotional information processing [19], [31], [32]. It also plays a role in memory enhancement in emotional conditions [16], [33], [34]. Cognition and emotion are often described as separable processes implemented by different regions of the brain. The amygdala, therefore, was unexpected to include cognitive functions. In this regard, a remarkable finding in this study is that the amygdala in the right hemisphere would possess some sort of cognitive functions, and plays a crucial role in working memory-related functions in particular.

Although to reveal the mechanism of impairment of WM function in AL is beyond the scope of the present study, we postulate two functional possibilities:

-

(a)

Cross link or connection

One hypothesis is that the amygdala, together with other brain networks, possesses functions related to WM. The prefrontal cortex is involved in WM [29], [35], [36], which has afferent and efferent connections to the amygdala. The ventral temporal cortex includes visual association area, which has functional connectivity with the amygdala [37].

-

(b)

Mediation

Another hypothesis is that the amygdala itself possesses no direct function of WM but rather controls a flow of signal or allocates roles among areas in the brain. In other words, the amygdala mediates the functional deficit. In this respect, a new perspective on the function of amygdala exists, which indicates that the amygdala allocates processing resources of the brain to a certain information vital to react surrounding environment properly [17].

4.4. Limitation of the present study

Although this study has reached its aims, some limitations exist in this report. First, because the purpose of this study was to examine the influence of amygdala lesion in the non-dominant hemisphere (rather than to compare the right and the left lesion), subjects with the left amygdala lesion were absent.

Second, this study lacked the potential to detect multi-dimensionality of symptoms. Since we carefully selected the patients without pathological emotional symptoms in order to focus on cognitive functions, no emotional symptoms appeared among the patients during a wide variety of evaluations. Thus, in the absence of patients with pathological emotional symptoms, our study was not sufficient to examine the correlation between the emotional symptoms and TLE-AL.

Third, a macroscopic description of anatomy and functional areas satisfied the objective of our study. Identifying a boundary at the cellular level and examining cellular loss and its effect on cognitive function were beyond our scope.

Fourth, the total number of patients is a little smaller than those of larger scale research using over 100 cases. This report, however, is of no less importance. The two groups of patients (TLE-AL and TLE-HS) showed no significant difference in terms of clinical and demographic characteristics. All patients were taking anti-seizure drugs at the time of evaluation. Background conditions of the patients, therefore, were almost identical, which is an essential condition for the reliability of results.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the features of TLE with a unilateral lesion in the right amygdala, and characterized the impairment in cognitive functions. The TLE patients with an amygdala lesion in the non-language dominant hemisphere exhibited noticeable decline of WM compared with the TLE-HS patients. Areas in the non-dominant hemisphere are typically regarded as not crucial in language-related functions. Our results, however, indicated the existence of memory-related function in the amygdala in the right hemisphere.

The present study also displayed a spatial pattern of cerebral glucose metabolism among patients with TLE-AL. We revealed that glucose hypometabolism was minimal for the right TLE-AL patients, while hypometabolism observed for the right TLE-HS patients was noticeable and extensive.

Although recent reports in the literature mentioned that the amygdala is involved in cognitive functions such as memory, learning, and attention [38], [39], [40], our study demonstrated specificity of impairments in memory function and glucose metabolic conditions in the right hemisphere.

The result may further suggest that presurgical examination must include attention to these functions such as working memory in the non-dominant hemisphere. Presurgical counseling in terms of a possibility of postsurgical cognitive deficit would benefit the surgical candidates. More investigation of this functional deficit is needed to identify the precise mechanism with our initial evidence.

Acknowledgements

This research was partly supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16K09723.

References

- 1.Engel J., Jr. Etiology as a risk factor for medically refractory epilepsy: a case for early surgical intervention. Neurology. 1998;51:1243–1244. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.5.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.French J.A., Williamson P.D., Thadani V.M., Darcey T.M., Mattson R.H., Spencer S.S. Characteristics of medial temporal lobe epilepsy: I. Results of history and physical examination. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:774–780. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson P.D., French J.A., Thadani V.M., Kim J.H., Novelly R.A., Spencer S.S. Characteristics of medial temporal lobe epilepsy: II. Interictal and ictal scalp electroencephalography, neuropsychological testing, neuroimaging, surgical results, and pathology. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:781–787. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gloor P. Oxford University Press; 1997. The temporal lobe and limbic system. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graebenitz S., Kedo O., Speckmann E.J., Gorji A., Panneck H., Hans V. Interictal-like network activity and receptor expression in the epileptic human lateral amygdala. Brain. 2011;134:2929–2947. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller L.A., McLachlan R.S., Bouwer M.S., Hudson L.P., Munoz D.G. Amygdalar sclerosis: preoperative indicators and outcome after temporal lobectomy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:1099–1105. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.9.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wieser H.G. Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy versus amygdalar epilepsy: late seizure recurrence after initially successful amygdalotomy and regained seizure control following hippocampectomy. Epileptic Disord. 2000;2:141–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beh S.M., Cook M.J., D'Souza W.J. Isolated amygdala enlargement in temporal lobe epilepsy: a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;60:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitsueda-Ono T., Ikeda A., Inouchi M., Takaya S., Matsumoto R., Hanakawa T. Amygdalar enlargement in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:652–657. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.206342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takaya S., Ikeda A., Mitsueda-Ono T., Matsumoto R., Inouchi M., Namiki C. Temporal lobe epilepsy with amygdala enlargement: a morphologic and functional study. J Neuroimaging. 2014;24:54–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2011.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du X., Usui N., Terada K., Baba K., Matsuda K., Tottori T. Semiological and electroencephalographic features of epilepsy with amygdalar lesion. Epilepsy Res. 2015;111:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tebartz Van Elst L., Baeumer D., Lemieux L., Woermann F.G., Koepp M., Krishnamoorthy S. Amygdala pathology in psychosis of epilepsy: a magnetic resonance imaging study in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2002;125:140–149. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bell B., Lin J.J., Seidenberg M., Hermann B. The neurobiology of cognitive disorders in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:154–164. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rausch R., Kraemer S., Pietras C.J., Le M., Vickrey B.G., Passaro E.A. Early and late cognitive changes following temporal lobe surgery for epilepsy. Neurology. 2003;60:951–959. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000048203.23766.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swanson L.W., Petrovich G.D. What is the amygdala? Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phelps E.A. Emotion and cognition: insights from studies of the human amygdala. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57:27–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pessoa L., Adolphs R. Emotion processing and the amygdala: from a ‘low road’ to ‘many roads’ of evaluating biological significance. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:773–783. doi: 10.1038/nrn2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray E.A. The amygdala, reward and emotion. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:489–497. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qin S., Young C.B., Duan X., Chen T., Supekar K., Menon V. Amygdala subregional structure and intrinsic functional connectivity predicts individual differences in anxiety during early childhood. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75:892–900. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaneko K., Sasaki M., Morioka T., Koga H., Abe K., Sawamoto H. Pre-surgical identification of epileptogenic areas in temporal lobe epilepsy by 123IiomazenilSPECT: a comparison with IMP SPECT and FDG PET. Nucl Med Commun. 2006;27:893–899. doi: 10.1097/01.mnm.0000243380.79872.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Umeoka S., Matsuda K., Baba K., Usui N., Tottori T., Terada K. Usefulness of 123I-iomazenil single-photon emission computed tomography in discriminating between mesial and lateral temporal lobe epilepsy in patients in whom magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates normal findings. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:352–363. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/08/0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wieser H.G. ILAE Commission Report. Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis. Epilepsia. 2004;45:695–714. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.09004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wechsler D., Fujita K., Maekawa H., Dairoku H., Yamanaka K. Nihon Bunka Kagakusha Co. Ltd.; 2006. The WAIS-III, Japanese version. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wechsler D., Sugishita M. Nihon Bunka Kagakusha Co. Ltd; 2001. The WMS-R, Japanese version. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lancaster J.L., Woldorff M.G., Parsons L.M., Liotti M., Freitas C.S., Rainey L. Automated Talairach atlas labels for functional brain mapping. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;10:120–131. doi: 10.1002/1097-0193(200007)10:3<120::AID-HBM30>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eickhoff S.B., Stephan K.E., Mohlberg H., Grefkes C., Fink G.R., Amunts K. A new SPM toolbox for combining probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps and functional imaging data. Neuroimage. 2005;25:1325–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minoshima S., Frey K.A., Koeppe R.A., Foster N.L., Kurk D.E. A Diagnostic approach in Alzheimer's disease using three-dimensional stereotactic surface projections of fluorine-18-FDGPET. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1238–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizumura S., Kumita S., Cho K., Ishihara M., Nakajo H., Toba M. Development ofquantitative analysis method for stereotactic brain image: assessment of reduced accumulation inextent and severity using anatomical segmentation. Ann Nucl Med. 2003;17:289–295. doi: 10.1007/BF02988523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sah P., Faber E.S.L., De Armentia M.L., Power J. The amygdaloid complex: anatomy and physiology. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:803–834. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitkanen A., Pikkarainen M., Nurminen N., Ylinen A. Reciprocal connections between the amygdala and the hippocampal formation, perirhinal cortex, and postrhinal cortex in rat — a review. In: Scharfman H.E., Witter M.P., Schwarcz R., editors. Parahippocampal region: implications for neurological and psychiatric diseases. 2000. pp. 369–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LeDoux J. The emotional brain, fear, and the amygdala. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2003;23:727–738. doi: 10.1023/A:1025048802629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baas D., Aleman A., Kahn R.S. Lateralization of amygdala activation: a systematic review of functional neuroimaging studies. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;45:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis M., Whalen P.J. The amygdala: vigilance and emotion. Mol Psychiatry. 2001;6:13–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paz R., Pelletier J.G., Bauer E.P., Pare D. Emotional enhancement of memory via amygdala-driven facilitation of rhinal interactions. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1321–1329. doi: 10.1038/nn1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baddeley A. Working memory: looking back and looking forward. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:829–839. doi: 10.1038/nrn1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lara A.H., Wallis J.D. The role of prefrontal cortex in working memory: a mini review. Front Syst Neurosci. 2015;9:173. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bickart K.C., Dickerson B.C., Barrett L.F. The amygdala as a hub in brain networks that support social life. Neuropsychologia. 2014;63:235–248. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallagher M., Holland P.C. The amygdala complex: multiple roles in associative learning and attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11771–11776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holland P.C., Gallagher M. Amygdala circuitry in attentional and representational processes. Trends Cogn Sci. 1999;3:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaefer A., Braver T.S., Reynolds J.R., Burgess G.C., Yarkoni T., Gray J.R. Individual differences in amygdala activity predict response speed during working memory. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10120–10128. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2567-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]