Resulting from hit-to-lead optimization, the aminopyrazole 3a is a NIK inhibitor selective over 44 kinases.

Resulting from hit-to-lead optimization, the aminopyrazole 3a is a NIK inhibitor selective over 44 kinases.

Abstract

NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK), an oncogenic drug target that is associated with various cancers, is a central signalling component of the non-canonical pathway. A blind screening process, which established that amino pyrazole related scaffolds have an effect on IKKbeta, led to a hit-to-lead optimization process that identified the aminopyrazole 3a as a low μM selective NIK inhibitor. Compound 3a effectively inhibited the NIK-dependent activation of the NF-κB pathway in tumour cells, confirming its selective inhibitory profile.

Acting as a key regulator of immune response, cell proliferation, cell death and inflammation, NF-κB is a ubiquitously expressed family of transcription factors known to be constitutively activated in a variety of malignancies, resulting in uncontrolled apoptosis, cell cycle deregulation and metastatic growth.1 These observations have led to the NF-κB pathway being validated as a target, particularly in breast2 and thyroid cancers.3 The non-canonical NF-κB pathway is an important component of NF-κB signalling and predominantly targets the activation of the p52/RelB NF-κB complex.4,5 Specifically, the non-canonical NF-κB pathway is involved in secondary lymphoid organ development, B cell survival and maturation, dendritic cell activation, lymphocyte recruitment and bone metabolism.6 NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) is a central signalling component of the non-canonical pathway that integrates signals from a subset of TNF receptor family members and activates a downstream kinase, IκB kinase-α (IKKα), triggering p100 phosphorylation and processing. The specific kinase inhibition activity shown by NIK may provide a means to directly inhibit the non-classical NF-κB pathway and thus potentially influence multiple human diseases, including a number of cancers.7 The crystal structure of the NIK catalytic domain has recently been resolved,8 allowing potent, conformationally restricted NIK inhibitors to be identified (Fig. 1).6,9,10

Fig. 1. Examples of selective NIK inhibitors A9 and B.6 PS-1145 structure of a potent IKKβ inhibitor.10.

With the aim of identifying new chemical entities11 that can block the NF-kB cascade, the authors have recently described 4-hydroxy-N-[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1,2,5-thiadiazole-3-carboxamide12,13 as a nM-inhibitor of the NF-κB pathway. Following that experience, in this work, a blind screening was conducted on the four kinases, IKKβ, IKKα, IKKε and NIK, which characterise the NF-κB pathway in order to find novel chemotypes. The study involved 2320 compounds from three dedicated Prestwick libraries (Prestwick Chemical Library® (1200 cpds), Prestwick Pyridazine Library (400 cpds) and Prestwick Fragment Library (720 cpds)). An aminopyrazole (2a, Fig. 2), which is able to weakly (microM range) but selectively inhibit IKKβ, was identified from among the 10 most promising hits. Starting from this compound, a hit-to-lead optimization process was directed to improve its potency while simultaneously retaining the observed selectivity. A schematic representation of compound 2a modulation is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. A schematic description of the compounds investigated in the hit-to-lead process applied to 2a.

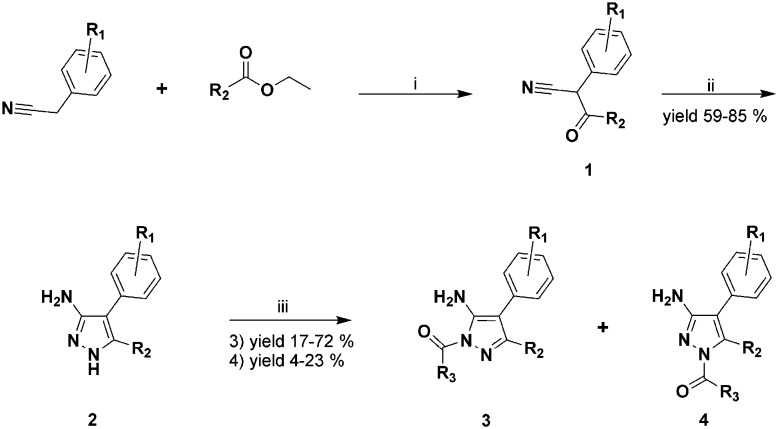

Of the 44 aminopyrazole derivatives involved in this study, 39 were synthesised using the general procedures described in Scheme 1, in which Claisen condensation between the appropriate ethyl ester and benzyl cyanide gave the 3-oxo-2-phenylpropionitriles (structure type 1). These systems had been allowed to react, according to a previously reported procedure,14 with an excess of hydrazine dihydrochloride to yield the desired 3-aminopyrazoles (structure type 2). Acetylated product types 3 and 4 were prepared from these compounds. The 3-aminopyrazoles (type 2) can be acetylated/alkylated in three positions: the primary exocyclic NH2 group and the two annular nitrogen atoms. The variations in the regiochemistry of the acylation reactions of 3-aminopyrazoles have been described in several studies,15–18 although 5-methyl-1H-pyrazol-3-amines, substituted with a phenyl-substituted group in the 4 position, have never been used as a substrate, to the best of our knowledge. Nevertheless, it appears that regioselective substitution is heavily dependent on the nature of the electrophilic reagent,15 as well as the reaction conditions and the substrate.19–22

Scheme 1. General synthesis scheme of the lead compounds with general structure formulae 2, 3 and 4. Reaction conditions: i) dry THF, NaH, reflux, overnight; ii) NH2NH2·2HCl, 3 Å sieves, dry EtOH, reflux, overnight; iii) R3COCl, dry pyridine, dry THF, rt, or appropriate anhydride, dry THF, rt, from 2 h to overnight.

The treatment of compound 2a with acetic anhydride gave two mono-acetylated products, 3a (the main product) and 4a. The functionalization of the two annular nitrogen atoms was established using the 1H NMR spectra of the two products obtained; broad singlet signals with δ values of 5.47 ppm and 6.75 ppm, which correspond to the NH2 protons, were observed in both spectra (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. 1H-NMR spectra of the starting material 2a and acylated 3a–4a.

The two regioisomers were distinguished by comparing their NH2 proton signals with a similar isomeric couple described in the literature (compounds C and D, Fig. 4).17 The authors observed the presence of two intramolecular N–H···O hydrogen bonds between the 5-exoamino group and the carbonyl of the N1-acetyl group in compound C, resulting in its NH2 signal being downfield compared to compound D. Notably, a downfield chemical shift in the pyrazolic CH3 signal, which was probably due to the shielding effect of the vicinal CH3CO group, can also be seen in compound 4a.

Fig. 4. Chemical shift of compounds described by Kusakiewicz-Dawid et al.17.

In order to modulate the active isomer 3a, other 1-acyl-5-aminopirazoles (see Fig. 2 and Scheme 1) were synthesised under Scheme 1 conditions. If the appropriate anhydrides were not commercially available, the corresponding and more accessible acyl chlorides were involved. As for 2a, acylation generally gave type 3 as the main product. In some cases, traces of compound type 4 were isolated and characterized (see the ESI†). In only two cases (compounds 6a and 6b) did the acylation of the primary exocyclic NH2 group occur (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of compounds 6a and 6b. Reaction conditions: i) pyridine-2-carbonyl chloride or trifluoroacetic anhydride, dry pyridine, dry THF, rt, overnight.

Surprisingly, when compound 2a was treated with pyridine-2-carbonyl chloride, in an attempt to obtain the corresponding 2-pyridinyl regioisomer 3, only carboxamide 6a was produced in modest yield. On the other hand, the synthesis of 6b should be carried out using trifluoroacetic anhydride instead of acetic anhydride. Pierce et al. have observed the same acylation trend in a number of 3,4-diaryl-5-aminopyrazoles.19

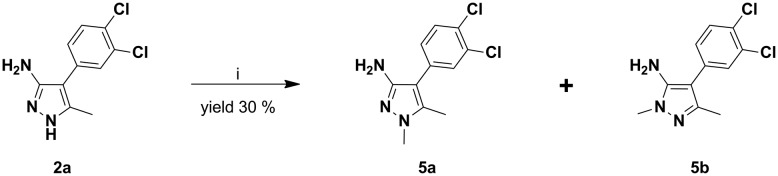

In an attempt to modulate 2avia the insertion of an alkyl group at endocyclic N positions of the pyrazole ring, it was reacted with 1.0 equivalent of methyl iodide, producing a mixture of compounds 5a and 5b (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Methylation of 2a to give compounds 5a and 5b. Reaction conditions: i) Cs2CO3, CH3I, dry THF, rt, overnight.

An effort to increase conversion yields, which were low for both regioisomers (19 and 11%), by adding more than 1 equivalent of methyl iodide resulted in dimethylated/polymethylated mixtures that were difficult to resolve. The two regioisomers (5a and 5b) were easily resolved by flash chromatography and distinguished using 2D-NMR (see the ESI†).

The designed compounds (Fig. 2) were biologically evaluated both at enzymatic and cellular levels and compared with Amgen compound A (Fig. 1)9 and PS-1145,23,24 which were used as NIK and IKKβ reference inhibitors, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. The effects of PS-1145, Amgen compound A and the designed compounds on ATP-based kinase assays for IKKβ, IKKα, IKKε and NIK (expressed as the IC50 value, μM). All experiments were performed in triplicate and the data represent means ± SD.

| CPD | IKKβ IC50 (μM) | IKKα IC50 (μM) | IKKε IC50 (μM) | NIK IC50 (μM) |

| PS-1145 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| Cpd A | >100 | >100 | >100 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| 2a | 50.9 ± 3.2 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 2b | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 2c | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 2d | 42.8 ± 1.3 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 2e | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 2f | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 2g | >100 | >100 | 93.4 | >100 |

| 2h | 88.0 ± 2.4 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 2i | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 2j | 22.4 ± 1.8 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 2k | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 2l | 37.9 ± 3.3 | >100 | >100 | 61.1 |

| 2m | 60.1 | 89.7 | >100 | >100 |

| 2n | >100 | >100 | 15.4 | >100 |

| 2o | 22.9 ± 3.5 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 2p | 75.7 ± 2.7 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 3a | >100 | >100 | >100 | 8.4 ± 1.3 |

| 3b | >100 | >100 | >100 | 27.4 ± 3.2 |

| 3c | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 3d | >100 | >100 | >100 | 24.3 ± 4.3 |

| 3e | >100 | >100 | >100 | 2.9 ± 1.1 |

| 3f | >100 | >100 | >100 | 41.0 ± 1.2 |

| 3g | >100 | >100 | >100 | 3.3 ± 0.4 |

| 3h | >100 | >100 | >100 | 23.0 ± 1.4 |

| 3i | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 3j | >100 | >100 | >100 | 58.2 ± 4.1 |

| 3l | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 3k | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 3m | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 3n | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 3o | >100 | >100 | >100 | 39.6 ± 0.9 |

| 3p | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 3q | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 3r | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 3s | 13.6 ± 1.6 | >100 | 22.9 ± 3.0 | >100 |

| 4a | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4e | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4i | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 4s | 47.7 ± 4.0 | >100 | >100 | 12.5 ± 2.1 |

| 5a | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 5b | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 6a | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 6b | >100 | 34.9 ± 2.3 | >100 | >100 |

In order to complete the biological investigation, we assayed all the compounds against the other three kinases that are involved in the canonical and non-canonical NF-κB activation pathways (IKKα, IKKε and NIK). The first group contains compounds (2b–2o) that were derived from 2avia modulation of the phenyl moiety. In 2b, the attempt to remove both the chlorine atoms present in 2a led to inactivity towards all four kinases. The same behaviour was observed when both the chlorine atoms present in 2a were replaced with lipophilic/bulky substituents (cpds 2c–2e). The meta substitution of compounds 2f–2j was investigated and it was observed that the presence of a trifluoromethyl group on 2j was beneficial for its IKKβ activity. 2j was two times more active against IKKβ (IC50 = 22.4 μM) than 2a but retains the same selectivity profile. Similar behaviour was observed in 2o (IC50 = 22.9 μM), which bears two meta trifluoromethyl groups. The presence of a single meta substitutent (cpds 2k–2n) does not generally appear to be beneficial for activity. The only interesting behaviour here was observed in 2l, which showed NIK, as well as IKKβ, activity. Inverting the phenyl and methyl moieties in compound 2p, which is an isomer of 2a, did not improve IKKβ activity, although selectivity was retained. The major breakthrough in the series was obtained when 3(5)-aminopyrazoles were acetylated/alkylated in one of the three nitrogen positions. While the substitution of the exocyclic NH2 (cpds 6a and 6b) and N1 acylation (cpds 4a, 4e and 4i) led to a complete loss of activity, it became evident that the N(2) acetyl analogue 3a was the most interesting compound in the entire series due to its selective NIK profile in the low μM range (IC50 = 8.4 μM). As the presence of the acetyl moiety was required for activity (the N(2) methyl analogue 5b was found to be inactive), the acyl substituent was investigated further (cpds 3b–3r), leading to the cyclobutyl analogue 3e (IC50 = 2.9 μM) and the cyclohexyl analogue 3g (IC50 = 3.32 μM) being observed as the most potent NIK inhibitors.

The cellular activity of the compounds with a NIK selective profile was evaluated using a gene reporter assay to measure NF-kB activation in EJM cells (ACC-560, DSMZ), a multiple myeloma cell line characterized by constitutively high levels of nuclear NF-κB as a consequence of NIK gene amplification.25 The inhibitory activity of each compound was determined at the highest concentration resulting in ≥80% cell viability on the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay (Table 2). Cell viability was determined using Promega CellTiter Glo luminescent assay. In order to check the selectivity of the compounds, gene reporter assays were carried out in SKBr3 (HTB-30, ATCC) and MDA-MB-231 (ACC-732, DSMZ), two cell lines in which constitutive activation of nuclear NF-κB is unrelated to NIK.26,27 All the compounds were found to inhibit the NF-κB activity in EJM cells, but not in MDA-MB-231 and SKBr3 cells, thus indicating their potential for NIK-selective inhibitory activity in cells. Compound 3a was also tested against two purified NIK kinase domains. The first was the mouse NIK kinase domain (mNIK) comprising amino acids 345–675 in which V480 was mutated to L, generating the so-called humanized KD-mNIK. The second one was the human NIK kinase domain (hNIK) comprising amino acids 330–680 in which S549 was mutated to D, generating the constitutively active form. Compound 3a did not show appreciable inhibitory activity against either domain (data not shown). Further investigations are in progress to identify the mode of action of compound 3a.

Table 2. The effects of PS-1145, Amgen compound A and the designed compounds on the NF-κB signalling pathway. NF-κB activation was assessed using Dual Luciferase reporter assay in a) MDA-MB-231, b) EJM and c) SKBr3 cells. Data are expressed as % of inhibition at the highest concentration tested, indicated in brackets. All experiments were performed in triplicate and the data represent means ± SD.

| Cpd | NF-kB reporter assay – % of inhibition (concentration) |

||

| MDA | EJM | SKBr3 | |

| PS-1145 | 87.9 ± 3.3 (50 μM) | 89.3 ± 4.3 (20 μM) | 3.6 ± 0.2 (50 μM) |

| Cpd A | 7.1 ± 0.4 (1 μM) | 93.5 ± 2.4 (1 μM) | 2.3 ± 0.1 (1 μM) |

| 2l | 29.9 ± 3.4 (50 μM) | 10.4 ± 1.1 (50 μM) | 4.2 ± 0.7 (100 μM) |

| 3a | –0.77 ± 0.1 (100 μM) | 83.4 ± 3.6 (25 μM) | 3.9 ± 0.2 (100 μM) |

| 3b | 10.3 ± 1.3 (100 μM) | 66.8 ± 2.2 (50 μM) | –3.14 ± 0.1 (100 μM) |

| 3d | 5.8 ± 0.3 (50 μM) | 68.9 ± 3.8 (100 μM) | 3.66 ± 0.1 (50 μM) |

| 3e | 2.36 ± 0.2 (100 μM) | 96.2 ± 4.1 (25 μM) | 5.2 ± 0.2 (100 μM) |

| 3g | 2.36 ± 0.6 (100 μM) | 94.7 ± 3.4 (25 μM) | 3.7 ± 1.3 (100 μM) |

| 3h | 13.8 ± 1.1 (100 μM) | 75.2 ± 2.8 (50 μM) | 0.31 ± 0.1 (100 μM) |

Given 3a was found to be selective towards the other kinases involved in NF-κB activation, we investigated its activity towards a larger kinase panel (Table 4). The determination of IC50 values for 44 representative kinases showed that 3a had a very good selectivity profile versus NIK (IC50 kinases >100 μM).

Table 4. IC50 profiling for 3a against 44 protein kinases.

| Kinase | IC50 (μM) | Kinase | IC50 (μM) |

| AMPK-alpha1 aa1-550 | >100 | JAK1 | >100 |

| AXL | >100 | MAP3K11 | >100 |

| B-RAF wt | >100 | MAP4K2 | >100 |

| CAMKK1 | >100 | MEK1 wt | >100 |

| CDK1/CycB1 | >100 | MELK | >100 |

| CHK2 | >100 | MET wt | >100 |

| CK1-alpha1 | >100 | MST1 | >100 |

| CK2-alpha1 | >100 | mTOR | >100 |

| CLK1 | >100 | NEK6 | >100 |

| COT | >100 | p38-alpha | >100 |

| CSK | >100 | PAK1 | >100 |

| DAPK1 | >100 | PCTAIRE1/CycY | >100 |

| DYRK1A | >100 | PDGFR-alpha wt | >100 |

| EGF-R wt | >100 | PDK1 | >100 |

| EPHA6 | >100 | PIM1 | >100 |

| ERK2 | >100 | PKC-alpha | >100 |

| FGF-R1 wt | >100 | PLK1 | >100 |

| FLT3 wt | >100 | SRC (GST-HIS-tag) | >100 |

| GSK3-beta | >100 | SRPK2 | >100 |

| HIPK1 | >100 | SYK | >100 |

| INS-R | >100 | TAOK2 | >100 |

| IRAK4 (untagged) | >100 | TLK1 | >100 |

The preliminary ADME profile of 3a was evaluated as the final step in this work. While 3a showed an acceptable log D value and solubility parameters at this stage, the relative metabolic instability of the compound was highlighted and must be considered in any future exploration (Table 3).

Table 3. Early ADME profiling for 3a.

aHuman liver microsomes (obtained from Xenotech: Xtreme 200 human liver microsomes) 1 μM, 37 °C, NADPH cofactor.

bCpd was also found to be unstable in the absence of NADPH, indicating chemical instability or a non-NADPH dependent enzymatic degradation.

cPBS pH 7.4/octanol.

dPBS pH 7.4, 60 min, room temperature.

In conclusion, we have herein identified N-acetyl-3-aminopyrazoles as new chemotypes that can block the NF-kB cascade by selectively inhibiting NIK. Compound 3a is the most representative of the series, which exhibited selectivity for NIK in a panel of 44 kinases. It also displayed acceptable log D and solubility parameters. Further experiments will be performed to elucidate the binding mode of 3a and improve its metabolic stability.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research has been financially supported by TAKTIC Translational Kinase Tumour Inhibitor discovery Consortium FP7-SME-2012 grant 315746. The authors wish to thank Dr. Annalisa Costale for performing all UPLC analyses, Dr. Livio Stevanato for performing all NMR experiments and for maintaining the instrument, and finally, Dr. Dale James Matthew Lawson for proofreading the final manuscript.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Additional biochemical data, chemistry, NMR characterization of final compounds, and biochemical protocols. See DOI: 10.1039/c8md00068a

References

- Park H., Shin Y., Choe H., Hong S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:337–348. doi: 10.1021/ja510636t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Nag S. A., Zhang R. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015;22:264–289. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666141106124315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozdeyev N., Berlinberg A., Wuensch K., Wood W. M., Zhou Q., Shibata H., Haugen B. R. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S.-C. Cell Res. 2011;21:71–85. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S.-C. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017;17:545–558. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanedo G. M., Blaquiere N., Beresini M., Bravo B., Brightbill H., Chen J., Cui H.-F., Eigenbrot C., Everett C., Feng J., Godemann R., Gogol E., Hymowitz S., Johnson A., Kayagaki N., Kohli P. B., Knuppel K., Kraemer J., Kruger S., Loke P., McEwan P., Montalbetti C., Roberts D. A., Smith M., Steinbacher S., Sujatha-Bhaskar S., Takahashi R., Wang X., Wu L. C., Zhang Y., Staben S. T. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:627–640. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Santillan K., Melendez-Zajgla J., Jimenez-Hernandez L. E., Gaytan-Cervantes J., Munoz-Galindo L., Pina-Sanchez P., Martinez-Ruiz G., Torres J., Garcia-Lopez P., Gonzalez-Torres C., Ruiz V., Avila-Moreno F., Velasco-Velazquez M., Perez-Tapia M., Maldonado V. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37340. doi: 10.1038/srep37340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leon-Boenig G., Bowman K. K., Feng J. A., Crawford T., Everett C., Franke Y., Oh A., Stanley M., Staben S. T., Starovasnik M. A., Wallweber H. J. A., Wu J., Wu L. C., Johnson A. R., Hymowitz S. G. Structure. 2012;20:1704–1714. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K., McGee L. R., Fisher B., Sudom A., Liu J., Rubenstein S. M., Anwer M. K., Cushing T. D., Shin Y., Ayres M., Lee F., Eksterowicz J., Faulder P., Waszkowycz B., Plotnikova O., Farrelly E., Xiao S.-H., Chen G., Wang Z. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:1238–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hideshima T., Chauhan D., Richardson P., Mitsiades C., Mitsiades N., Hayashi T., Munshi N., Dang L., Castro A., Palombella V., Adams J., Anderson K. C. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:16639–16647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200360200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lolli M., Narramore S., Fishwick C. W. G., Pors K. Drug Discovery Today. 2015;20:1018–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainas S., Pippione A. C., Giorgis M., Lupino E., Goyal P., Ramondetti C., Buccinna B., Piccinini M., Braga R. C., Andrade C. H., Andersson M., Moritzer A. C., Friemann R., Mensa S., Al-Kadaraghi S., Boschi D., Lolli M. L. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;129:287–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pippione A. C., Federico A., Ducime A., Sainas S., Boschi D., Barge A., Lupino E., Piccinini M., Kubbutat M., Contreras J. M., Morice C., Al-Karadaghi S., Lolli M. L. MedChemComm. 2017;8:1850–1855. doi: 10.1039/c7md00278e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton D. R., Sheng S., Carlson K. E., Rebacz N. A., Lee I. Y., Katzenellenbogen B. S., Katzenellenbogen J. A. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:5872–5893. doi: 10.1021/jm049631k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwar H. F., Elnagdi M. H. ARKIVOC. 2009:198–250. [Google Scholar]

- Plescia S., Daidone G., Bajardi M. L. J. Heterocyclic Chem. 1982;19:685–687. [Google Scholar]

- Kusakiewicz-Dawid A., Masiukiewicz E., Rzeszotarska B., Dybala I., Koziol A. E., Broda M. A. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007;55:747–752. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke D., Mares R. W., McNab H., Riddell F. G. Magn. Reson. Chem. 1994;32:255–257. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce L. T., Cahill M. M., McCarthy F. O. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:4601–4611. [Google Scholar]

- Pask C. M., Camm K. D., Kilner C. A., Halcrow M. A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:2531–2534. [Google Scholar]

- Deprez-Poulain R., Cousaert N., Toto P., Willand N., Deprez B. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:3867–3876. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Adiwish W. M., Tahir M. I., Siti-Noor-Adnalizawati A., Hashim S. F., Ibrahim N., Yaacob W. A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;64:464–476. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- t. H. Obtained from Sigma (code: P6624).

- Castro A. C., Dang L. C., Soucy F., Grenier L., Mazdiyasni H., Hottelet M., Parent L., Pien C., Palombella V., Adams J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003;13:2419–2422. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00408-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annunziata C. M., Davis R. E., Demchenko Y., Bellamy W., Gabrea A., Zhan F., Lenz G., Hanamura I., Wright G., Xiao W., Dave S., Hurt E. M., Tan B., Zhao H., Stephens O., Santra M., Williams D. R., Dang L., Barlogie B., Shaughnessy J. D., Kuehl W. M., Staudt L. M. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkhofer E. C., Cogswell P., Baldwin A. S. Oncogene. 2009;29:1238. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi N., Ito T., Azuma S., Ito E., Honma R., Yanagisawa Y., Nishikawa A., Kawamura M., Imai J.-i., Watanabe S., Semba K., Inoue J.-i. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1668–1674. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.