Compound 6 potently inhibited the enzymatic activity of BTK with an IC50 value of 1.9 nM.

Compound 6 potently inhibited the enzymatic activity of BTK with an IC50 value of 1.9 nM.

Abstract

Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) plays a critical role in B cell receptor (BCR)-mediated signaling pathways responsible for the development and function of B cells, which makes it an attractive target for the treatment of many types of B-cell malignancies. Herein, a series of N5-substituted 6,7-dioxo-6,7-dihydropteridine-based, irreversible BTK inhibitors were reported with IC50 values ranging from 1.9 to 236.6 nM in the enzymatic inhibition assay. Compounds 6 and 7 significantly inhibited the proliferation of Ramos cells which overexpress the BTK enzyme, as well as the autophosphorylation of BTK at Tyr223 and the activation of its downstream signaling molecule PLCγ2. Overall, this series of compounds could provide a promising starting point for further development of potent BTK inhibitors for B-cell malignancy treatment.

Introduction

Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK), a member of the Tec family of non-receptor protein-tyrosine kinases,1 is an essential enzyme in the B cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway, which regulates the proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis of B cells.2 Upon binding of specific antigen to BCR, the downstream signaling cascades are initialized, inducing the phosphorylation and activation of LYN and spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK), which in turn binds and activates phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) to produce phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3).3,4 After aggregating into the plasma membrane through binding to PIP3 via its pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, BTK becomes fully activated with phosphorylation of Tyr551 by LYN and SYK, as well as autophosphorylation of Tyr223.5 Activated BTK phosphorylates phospholipase C (PLC) γ2, resulting in the production of inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG), both of which are important second messengers that participate in Ca2+ mobilization and many downstream transcriptional signaling such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB).6–9

Studies have shown that overexpression and gain of function mutations of BTK have been observed in many types of B-cell malignancies, including acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL),10 chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL),11,12 mantle cell lymphoma (MCL),13,14 and multiple myeloma (MM).15 The BCR signaling pathway that is activated by overexpressed BTK inhibits the normal differentiation and apoptosis of B cells, leading to abnormal proliferation, so the inhibition of BTK activity is expected to provide an effective strategy for the clinical treatment of B-cell malignancies. As the mechanism of action of BTK-associated signal-transduction pathways is explored in depth, various small molecules of BTK inhibitors (as shown in Fig. 1) have been developed as therapeutic agents for B-cell malignancies.15,16

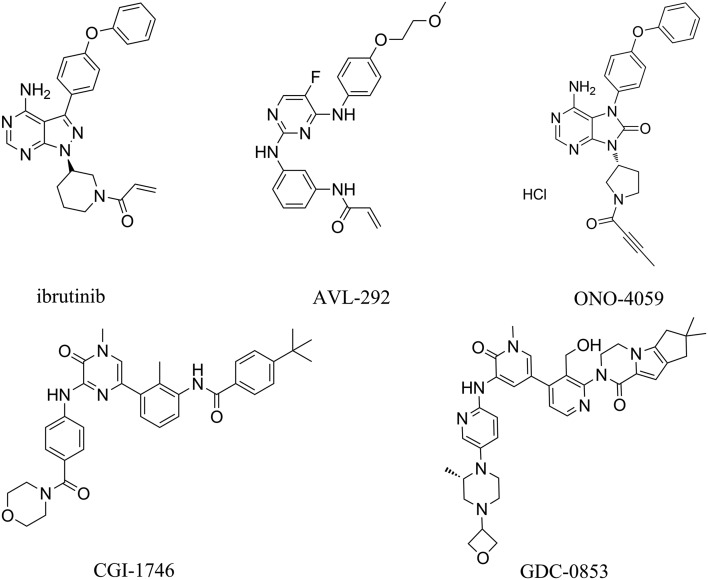

Fig. 1. Representative structures of reported BTK inhibitors.

With the breakthrough therapy designation ibrutinib (PCI-32765), the most clinically effective irreversible BTK inhibitor, has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of MCL in September 2013, CLL in February 2014,17 and Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia (WM) in January 2015.18 In addition, a number of BTK inhibitors including AVL-292,19 ONO-4059,20 CGI-1746 (ref. 21) and GDC-0853 (ref. 22) are in various stages of preclinical or clinical trials as potential therapeutic agents for hematological malignancies. However, most of the BTK inhibitors mentioned above have been reported to have limited efficacy and strong side effects.23,24 Hence, there is still an increasing need to discover novel BTK inhibitors which could be developed into therapeutic candidates for the treatment of B-cell malignancies. In this study, a series of N5-substituted 6,7-dioxo-6,7-dihydropteridines were identified as irreversible BTK inhibitors, and the structure–activity relationship (SAR) was investigated through analysis of their proposed docking poses to shed light on further structural modification. Cellular activities and kinase selectivities of two representative compounds 6 and 7 were tested to better evaluate their effects against BTK.

Materials and methods

Covalent docking

Compounds were docked to the ATP-binding pocket of BTK through the covalent docking protocol of Maestro 10.1 (Schrödinger LLC, Release 2015). After being derived from the Protein Data Bank, the crystal structure of BTK in complex with a small molecule B43 (PDB code 3GEN)25 was modified using the Protein Preparation Wizard. The inhibitor was expected to bind to Cys481 of BTK by Michael addition reaction and its core position was constrained to a maximum acceptable RMSD value of 1.0 Å from that of the binding ligand B43. The docking mode was specified as pose prediction, which performs the full protocol to find the accurate docking pose. The affinity score between the inhibitor and BTK was calculated using Glide.26

Cell culture and reagents

The human Burkitt's lymphoma cell line Ramos was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The cell line was grown in RPMI-1640 (Gibco®, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco®, USA). The cell line was maintained and propagated as monolayer cultures at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

In vitro enzymatic activity assay and kinase selectivity profiles

Kinase viability assays and kinase selectivity profiles were evaluated using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The BTK enzyme was purchased from Millipore. A total of 20 μg mL–1 Poly (Glu, Tyr)4:1 (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was precoated in 96-well ELISA plates as a substrate. Active kinases were incubated with indicated drugs in a 1× reaction buffer (50 mmol L–1 HEPES pH 7.4, 20 mmol L–1 MgCl2, 0.1 mmol L–1 MnCl2, 0.2 mmol L–1 Na3VO4, 1 mmol L–1 DTT) containing 5 μmol L–1 ATP at 37 °C for 1 hour. After incubation, the wells were washed with PBS and then incubated with an anti-phosphotyrosine (PY99) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) followed by incubation with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody. The wells were visualized using o-phenylenediamine (OPD) and the absorbance was read with a multiwell spectrophotometer (VERSAmax™, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 492 nm.

Cell proliferation inhibition assay

All the cell proliferation assays were evaluated using the thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. The lymphoma cells were seeded in 96-well plates and grown for 2 hours. The cells were then treated with various concentrations of PBS solution containing test compounds, with each concentration tested in triplicate, and then cells were cultured for an additional 72 hours. At the end of exposure, 20 μL of MTT (5 mg ml–1) was added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 4 hours until a purple precipitate is visible. Next, 100 μL of SDS lysis buffer was added and the plate was put back in the cell incubator. The absorbance of each well was recorded at 570 nm using a multiwell spectrophotometer (VERSAmax, Molecular Devices). The inhibition rate for cell proliferation was calculated as [1 – (A515 treated/A515 control)] × 100%.

Western blot analysis

Cells were suspended in a 1× lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 100 mM DTT, 2% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 10% glycerol] and boiled for 30 minutes. Western blot analysis was subsequently performed as per standard procedures. Antibodies directed against the following proteins were used: BTK, p-BTK (Tyr223), PLCγ2, p-PLCγ2, which were obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies (Cambridge, MA, USA). β-Actin and α-tubulin were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Results and discussion

SAR analysis

In a previous study, we elaborated a series of N5-substituted 6,7-dioxo-6,7-dihydropteridine derivatives as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors, among which compound 5 also exhibited inhibitory activity (percent of control value is 4%) against BTK at the concentration of 1000 nM in the kinase profiling study.27 To further evaluate their inhibitory effects against BTK, an in vitro enzymatic activity assay was performed and the results are shown in Table 1. Compound 1 strongly inhibited the enzymatic activity of BTK with an IC50 value of 5.4 nM. Its predicted covalent docking pose (Fig. 2A) shows that the 6,7-dioxo-6,7-dihydropteridine core occupies the pocket adjacent to the hinge region, forming classic bidentate hydrogen bond interactions with the backbone of Met477. The left-hand side chain extends out of the ATP-binding pocket, but the hydrogen bond interaction between the methoxy group and Tyr476 and the hydrophobic interactions between the phenyl group and residues Leu408 and Gly480 provide favorable impacts on binding activities. Additionally, the N-methylpiperazine moiety is poised in a suitable position to allow for the electrostatic interaction with Glu488 and the hydrophobic interaction with Asn484. As expected, the electrophilic acrylamide group is covalently bonded to Cys481, along with the formation of the fourth hydrogen bond interaction between the oxygen atom and the nitrogen atom on the side chain of Asn484.

Table 1. In vitro enzymatic inhibitory activities of compounds 1–10.

| ||||

| Compd. | R 1 | R 2 | R 3 | Enzymatic inhibitory activity (IC50, nM) a |

| 1 | –H | 2-OCH3 |

|

5.4 ± 1.3 |

| 2 | –CH3 | 2-OCH3 |

|

236.6 ± 26.4 |

| 3 |

|

2-OCH3 |

|

17.2 ± 9.3 |

| 4 |

|

2-OCH3 |

|

21.8 ± 19.4 |

| 5 |

|

2-OCH3 |

|

47.4 ± 26.7 |

| 6 |

|

3-CH3 |

|

1.9 ± 2.1 |

| 7 |

|

3-OCH3 |

|

2.4 ± 1.1 |

| 8 |

|

2-OCH3 |

|

20.8 ± 15.8 |

| 9 |

|

2-OCH3 |

|

31.9 ± 20.9 |

| 10 |

|

2-OCH3 |

|

12.8 ± 7.4 |

| Ibrutinib | 0.6 | |||

aBTK inhibitory activity was conducted by using the ELISA-based assay. Data are reported as mean ± SD (standard deviation).

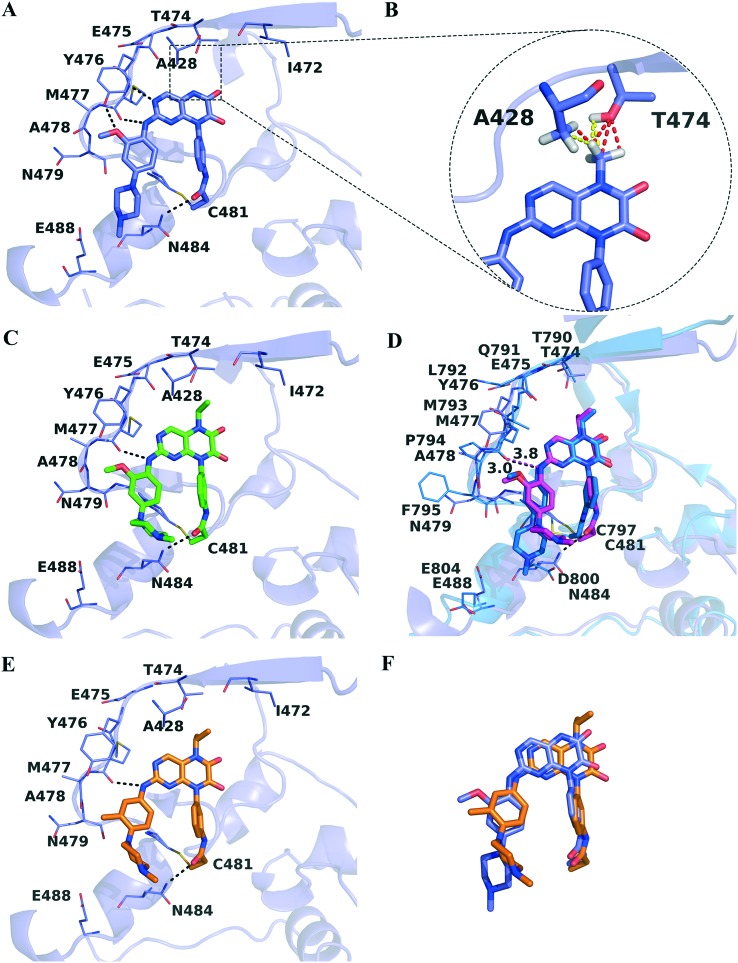

Fig. 2. (A) Putative binding pose of compound 1 (purple) against BTK (purple). BTK is shown in a cartoon representation with the inhibitor in a stick representation. Key residues are shown as sticks and the hydrogen bonds are highlighted as black dashed lines. (B) Representation of bad (yellow) and ugly (red) contacts between the N5-substituted methyl group and residues Ala428 and Thr474. Hydrogen atoms involved are displayed for explanation purposes. (C) Putative binding pose of compound 3 (green) against BTK. (D) Superposition of the BTK structure in complex with compound 5 (magenta) and EGFR (blue) in complex with 5 (blue). (E) Putative binding pose of compound 6 (orange) against BTK. (F) Alignment of putative binding poses of compounds 1 and 6.

The N-5 atom of compound 1 lies directly beneath the side chain of the gatekeeper residue Thr474, thus the introduction of the methyl group in the N-5 position may cause disadvantageous steric clashes which leads to a 43-fold activity loss of compound 2. Based on the predicted pose of compound 1, a methyl group was added to the N-5 atom by using the build toolbar of Maestro 10.0, and unfavorable Bad and Ugly contacts were detected with residues Ala428 and Thr474 (Fig. 2B) through the measurement toolbar with default criteria. However, when the N5-substituted alkyl group became larger, improved inhibitory activities (but still lower than that of compound 1) were observed for compounds 3–5 compared to compound 2, in accordance with the previously reported activity tendency against wild-type EGFR possessing the same threonine gatekeeper. In the proposed binding mode against BTK (Fig. 2C), compound 3 moves slightly towards the hydrophobic pocket behind Thr474 to accommodate the ATP binding site well. Consequently, the 6,7-dioxo-6,7-dihydropteridine core is farther away from the hinge region, bringing about the disappearance of the hydrogen bond interaction between Met477 and the N-3 atom that is observed for compound 1. The ethyl group occupies the entrance of the back pocket, participating in favorable hydrophobic contacts and van der Waals (VDW) interactions with residues Thr474, Ala428 and Lys430, which may partially compensate the reduction of activity induced by the hydrogen bond disruption.

Compound 5 has an isopropyl group at the N-5 moiety, and its IC50 value is 47.4 nM against BTK. As a potent wide-type EGFR inhibitor with an IC50 value of 2.0 nM, compound 5 exhibited 23-fold selectivity over BTK. The predicted covalent docking poses of compound 5 bound to BTK and EGFR, respectively, were aligned, to probe the structural basis for selectivity. The conformations of the hinge loops of BTK and EGFR are slightly different, due to the great diversity of residues in the two regions. In the compound 5–EGFR complex (Fig. 2D) derived from the previous study,27 a hydrogen bond is formed between the nitrogen atom of the –NH– group and the oxygen atom of the backbone of Met793. Despite of the similar binding mode, compound 5 is not involved in hydrogen bond interactions with the hinge region of BTK, as the distance between its nitrogen atom and the oxygen atom of Met477 increases from 3.0 Å to 3.8 Å.28 Previously reported BTK inhibitors tend to interact with the hinge region through hydrogen bond interactions, which are highly conserved in most kinase-inhibitor cocrystal structures.29 Presumably, the lower inhibitory activity of compound 5 against BTK is mainly ascribed to the absence of hydrogen bond interactions with the hinge region.

When the methoxy group was removed from the 2-position of benzene on the left-hand side chain and the methyl and methoxy groups were introduced at the 3-position, compounds 6 and 7 displayed 24-fold and 19-fold enhanced potencies against BTK relative to compound 5, respectively. As depicted in Fig. 2E, compound 6 tilts slightly towards the activation loop to avoid steric clash with Thr474, with N5-substituted isopropyl partly extending to the back pocket and forming expected hydrophobic interactions with adjacent residues. Similar to compound 3, compound 6 forms a hydrogen bond interaction with Met477 via its nitrogen atom of the –NH– group. Corresponding to Leu792 in EGFR, the Tec-family kinases including BTK have a bulkier tyrosine residue in the hinge region which would sterically interfere with bound inhibitor molecules containing bulky substituents.30 In the predicted binding pose of compound 6 in complex with BTK, the 2-position of benzene on the left-hand side chain is located close to Tyr476, probably giving rise to steric clashes if a methoxy group is introduced, hence the inhibitory activities of compounds 6 and 7 increased after removing the methoxy group at the 2-position of benzene. Intriguingly, compound 1 bearing a 2-methoxyphenyl moiety exhibited a comparable single nanomolar IC50 value with compounds 6 and 7 against BTK. After aligning the two docking poses (Fig. 2F), it was found that the deviation of the 6,7-dioxo-6,7-dihydropteridine core of compound 6 from Thr47 triggered the different orientations of the two left-hand side chains as well, where the 2-position of benzene of compound 1 lies in a position farther away from Tyr476 to tolerate the methoxy group well. Therefore, the potential steric conflicts of the gatekeeper residue Thr474 and the hinge loop residue Tyr476 should be taken into consideration simultaneously to optimize and obtain potent BTK inhibitors.

Compared with compound 5, replacements of the N-methylpiperazine moiety with N,N,N′-trimethylethylenediamine, N,N-dimethylethanolamine, and 1-methyl-4-(piperidin-4-yl)piperazine yielded more potent compounds 8–10 against BTK. Whereas the IC50 values are still in the same range as that of compound 5, suggesting that the single modification of the R3 group could not induce significantly increased inhibitory potency against BTK.

Antiproliferative effects of compounds 1, 6 and 7 against Ramos cells

As proof, compounds 1, 6 and 7 were identified as potent BTK inhibitors in the enzymatic assay, with IC50 values at 5.4 nM, 1.9 nM and 2.4 nM, respectively. Subsequently, their potency to repress B cell proliferation was evaluated using Ramos lymphoma cells which express high levels of BTK and were widely used to evaluate BTK inhibition.31 The FDA-approved drug ibrutinib was used as the reference compound. The results illustrated in Table 2 showed that compounds 6 and 7 could inhibit the proliferation of Ramos cells with micromolar IC50 values (9.37 and 10.08 μM, respectively) comparable to that of ibrutinib (6.18 μM). In spite of the high inhibitory effects in the enzymatic assay, compound 1 totally lost its activity at the cellular level. The predicted QPPCaco2 value of compound 1 was 22.4 as reported in our previous study,27 and the poor cell permeability (<25) may be exactly the reason for the disappearance of the compound's cellular efficacy on Ramos cells.

Table 2. In vitro antiproliferative effects of compounds 1, 6 and 7 against Ramos cells.

| Compd. | Cellular antiproliferative activity (IC50, μM) a |

| 1 | >100 |

| 6 | 9.37 ± 1.16 |

| 7 | 10.08 ± 1.18 |

| Ibrutinib | 6.18 ± 1.44 |

aAntiproliferation activities of compounds were detected by using the MTT assay. Data are averages of at least two independent determinations and reported as mean ± SD.

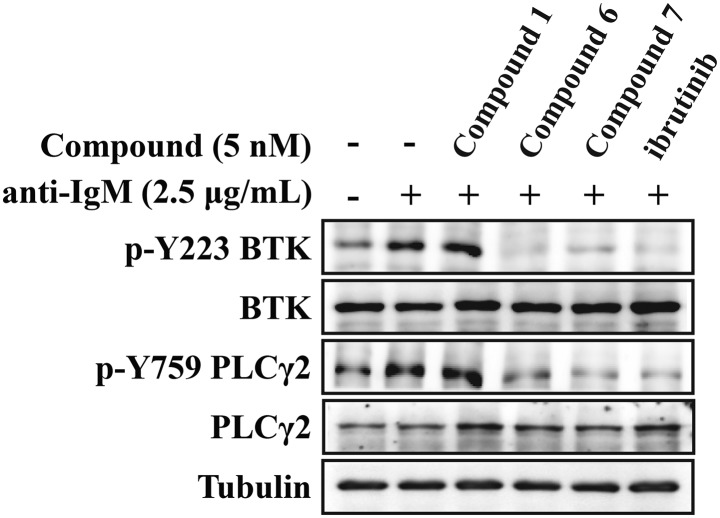

Effects of compounds 1, 6 and 7 on the BTK-mediated signaling pathway

BTK inhibitors regulate the development and function of B cells through disruption of BTK-mediated signaling pathways.32,33 We, thus, proceeded to evaluate the inhibitory activities of these compounds on BTK activation and downstream signaling transduction in Ramos cells. The results (Fig. 3) demonstrated that compounds 6 and 7 significantly inhibited the phosphorylation of BTK Tyr223 induced by anti-IgM, as well as the activation of its downstream signaling molecule PLCγ2. Likewise, compound 1 poorly affected the activation of BTK in the corresponding cells because of its poor cell permeability.

Fig. 3. Phosphorylation blocking effects of compounds 1, 6 and 7 for BTK Tyr223 and the downstream molecule PLCγ2. Cells were starved for 2 h and treated with indicated concentration of compounds 1, 6, 7 or ibrutinib for 1.5 h and then stimulated by anti-IgM (2.5 μg mL–1) for 15 min.

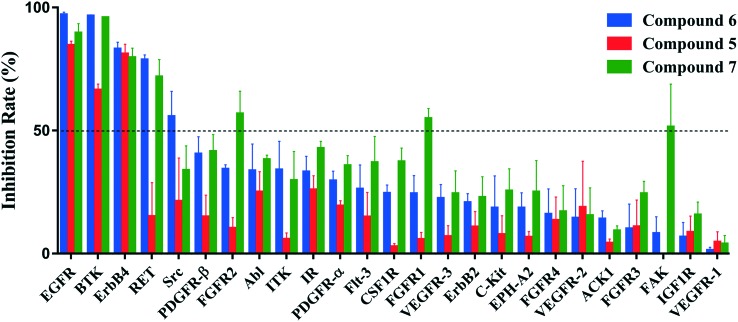

Kinase selectivities of compounds 5, 6 and 7

To assess the kinase selectivity profiles of this chemical series, the in vitro inhibitory effects of compounds 5, 6 and 7 were measured against a panel of kinases that are available in our lab. Among the 25 kinases displayed in Fig. 4, there are four kinases that share a modifiable cysteine at the same position as Cys481 on BTK: EGFR, ErbB2, ErbB4 and ITK. Except for BTK and EGFR, the three compounds were also active against ErbB4 at 100 nM, but their inhibitory activities against ErbB2 and ITK were very weak (inhibition rate < 35%). It has been reported that ibrutinib showed potency against ErbB2 (IC50 = 9.4 nM) and ITK (IC50 = 10.7 nM).34 Therefore, compounds 6 and 7 seemed to be superior in terms of selectivities to those kinases susceptible to irreversible inhibition by ibrutinib. The more selective BTK binding profiles of compounds 6 and 7, and their implications regarding in vivo pharmacological effects, however, still need further thorough investigation.

Fig. 4. Kinase selectivities of compounds 5, 6 and 7 against 25 kinases. Measurements were conducted at a concentration of 100 nM and the values were determined from the results of two independent tests.

For the majority of tested kinases without a homologous cysteine, the three compounds showed moderate or weak inhibitory activities (inhibition rate < 50% at 100 nM). Unlike compound 5, both compounds 6 and 7 could significantly inhibit the activity of RET at 100 nM (inhibition rate > 70%). RET has tyrosine at the structurally identical position of Tyr476 on BTK in the hinge region,35 and the large residue probably causes the activity loss of compound 5. The activity divergence between compound 5 and compounds 6 and 7 corresponds well to that observed against BTK, implying that, as mentioned above, the substituent position on the phenyl group of the left-hand side chain may be vital to alter the inhibitory activities towards different kinases for the chemical scaffold reported in this study.

Conclusions

In summary, a series of N5-substituted 6,7-dioxo-6,7-dihydropteridines were identified as BTK inhibitors through the in vitro enzymatic activity assay, among which compounds 1, 6 and 7 were the most active ones with single nanomolar IC50 values. SAR analysis revealed that the volume of N5-substituents and the position of substituents on the phenyl group of the left-hand side chain were the critical factors that affected the activities of the compounds against BTK at the enzymatic level, which would shed light on further structural optimization. Due to poor cell permeability, compound 1 showed no activity at the cellular level, reflecting the significance of suitable physicochemical properties for a small molecule to exert its biological action. Meanwhile, compounds 6 and 7 could repress the proliferation of Ramos cells and inhibit the activation of BTK and its downstream signaling molecule PLCγ2, demonstrating their potential applications for further in vivo studies. We believe that these compounds discovered in this study will provide a novel scaffold for hit-to-lead optimization and lay the foundation for further development of therapeutic candidates for the treatment of B-cell malignancies by targeting BTK.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The research is supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program (Grant 2016YFA0502304), the Special Program for Applied Research on Super Computation of the NSFC-Guangdong Joint Fund (the second phase) under Grant No. U1501501 and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

References

- Smith C., Islam T. C., Mattsson P. T., Mohamed A. J., Nore B. F., Vihinen M. BioEssays. 2001;23:436–446. doi: 10.1002/bies.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buggy J. J., Elias L. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2012;31:119–132. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2012.664797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw J. M. Cell. Signalling. 2010;22:1175–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinleye A., Chen Y., Mukhi N., Song Y., Liu D. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2013;6:59. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed A. J., Yu L., Bäckesjö C. M., Vargas L., Faryal R., Aints A., Christensson B., Berglöf A., Vihinen M., Nore B. F., Smith C. I. E. Immunol. Rev. 2009;228:58–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassford J., Soeiro I., Skarell S. M., Banerji L., Holman M., Klaus G. G., Kadowaki T., Koyasu S., Lam E. W. Oncogene. 2003;22:2248–2259. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajpai U. D., Zhang K., Teutsch M., Sen R., Wortis H. H. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:1735–1744. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.10.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petro J. B., Khan W. N. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:1715–1719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto S., Iwamatsu A., Ishiai M., Okawa K., Yamadori T., Matsushita M., Baba Y., Kishimoto T., Kurosaki T., Tsukada S. Blood. 1999;94:2357–2364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman P. A., Wood C. M., Vassilev A. O., Mao C., Uckun F. M. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2003;44:1011–1018. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000067576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kil L. P., de Bruijn M. J., van Hulst J. A., Langerak A. W., Yuvaraj S., Hendriks R. W. Am. J. Blood Res. 2013;3:71–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. R., Barrientos J. C., Barr P. M., Flinn I. W., Burger J. A., Tran A., Clow F., James D. F., Graef T., Friedberg J. W., Rai K., O'Brien S. Blood. 2015;125:2915–2922. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-585869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterthwaite A. B., Witte O. N. Immunol. Rev. 2000;175:120–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckesjö C.-M., Vargas L., Superti-Furga G., Smith C. I. E. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;299:510–515. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J. A. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2014;9:44–49. doi: 10.1007/s11899-013-0188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Cruz O. J., Uckun F. M. OncoTargets Ther. 2013;6:161–176. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S33732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.-S., Rattu M. A., Kim S. S. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2016;22:92–104. doi: 10.1177/1078155214561281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavriatopoulou M., Terpos E., Kastritis E., Dimopoulos M. A. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2017;26:197–205. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2017.1275561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. R., Sharman J. P., Harb W. A., Kelly K. R., Schreeder M. T., Sweetenham J. W., Barr P. M., Foran J. M., Gabrilove J. L., Kipps T. J., Ma S., O'Brien S. M., Evans E., Lounsbury H., Silver B. A., Singh J., Stiede K., Westlin W., Witowski S., Mahadevan D. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:8032. [Google Scholar]

- Walter H. S., Rule S. A., Dyer M. J. S., Karlin L., Jones C., Cazin B., Quittet P., Shah N., Hutchinson C. V., Honda H., Duffy K., Birkett J., Jamieson V., Courtenay-Luck N., Yoshizawa T., Sharpe J., Ohno T., Abe S., Nishimura A., Cartron G., Morschhauser F., Fegan C., Salles G. Blood. 2016;127:411–419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-664086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo J. A., Huang T., Balazs M., Barbosa J., Barck K. H., Bravo B. J., Carano R. A. D., Darrow J., Davies D. R., DeForge L. E., Diehl L., Ferrando R., Gallion S. L., Giannetti A. M., Gribling P., Hurez V., Hymowitz S. G., Jones R., Kropf J. E., Lee W. P., Maciejewski P. M., Mitchell S. A., Rong H., Staker B. L., Whitney J. A., Yeh S., Young W. B., Yu C., Zhang J. A., Reif K., Currie K. S. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:41–50. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young W. B., Barbosa J., Blomgren P., Bremer M. C., Crawford J. J., Dambach D., Eigenbrot C., Gallion S., Johnson A. R., Kropf J. E., Lee S. H., Liu L., Lubach J. W., Macaluso J., Maciejewski P., Mitchell S. A., Ortwine D. F., Paolo J. D., Reif K., Scheerens H., Schmitt A., Wang X., Wong H., Xiong J.-M., Xu J., Yu C., Zhao Z., Currie K. S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;26:575–579. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aw A., Brown J. R. Drugs Aging. 2017;34:509–527. doi: 10.1007/s40266-017-0468-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd J. C., Furman R. R., Coutre S. E., Flinn I. W., Burger J. A., Blum K. A., Grant B., Sharman J. P., Coleman M., Wierda W. G., Jones J. A., Zhao W. Q., Heerema N. A., Johnson A. J., Sukbuntherng J., Chang B. Y., Clow F., Hedrick E., Buggy J. J., James D. F., O'Brien S. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:32–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte D. J., Liu Y. T., Arduini R. M., Hession C. A., Miatkowski K., Wildes C. P., Cullen P. F., Hong V., Hopkins B. T., Mertsching E., Jenkins T. J., Romanowski M. J., Baker D. P., Silvian L. F. Protein Sci. 2010;19:429–439. doi: 10.1002/pro.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesner R. A., Banks J. L., Murphy R. B., Halgren T. A., Klicic J. J., Mainz D. T., Repasky M. P., Knoll E. H., Shelley M., Perry J. K., Shaw D. E., Francis P., Shenkin P. S. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y., Wang X., Zhang T., Sun D., Tong Y., Xu Y., Chen H., Tong L., Zhu L., Zhao Z., Chen Z., Ding J., Xie H., Xu Y., Li H. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:7111–7124. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:48–76. [Google Scholar]

- van Linden O. P., Kooistra A. J., Leurs R., de Esch I. J., de Graaf C. J. Med. Chem. 2013;57:249–277. doi: 10.1021/jm400378w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Ercan D., Chen L., Yun C. H., Li D., Capelletti M., Cortot A. B., Chirieac L., Iacob R. E., Padera R., Engen J. R., Wong K. K., Eck M. J., Gray N. S., Janne P. A. Nature. 2009;462:1070–1074. doi: 10.1038/nature08622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitanaka A., Mano H., Conley M. E., Campana D. Blood. 1998;91:940–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata M., Kurosaki T. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:31–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauld S. B., Dal Porto J. M., Cambier J. C. Science. 2002;296:1641–1642. doi: 10.1126/science.1071546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honigberg L. A., Smith A. M., Sirisawad M., Verner E., Loury D., Chang B., Li S., Pan Z., Thamm D. H., Miller R. A., Buggy J. J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:13075–13080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004594107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles P. P., Murray-Rust J., Kjær S., Scott R. P., Hanrahan S., Santoro M., Ibáñez C. F., McDonald N. Q. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:33577–33587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]