A novel myeloperoxidase inhibitor, 7-benzylether triazolopyrimidine was discovered which reversibly inhibits enzyme activity and shows pharmacodynamic effects in mouse models.

A novel myeloperoxidase inhibitor, 7-benzylether triazolopyrimidine was discovered which reversibly inhibits enzyme activity and shows pharmacodynamic effects in mouse models.

Abstract

Myeloperoxidase, a mammalian peroxidase involved in the immune system as an anti-microbial first responder, can produce hypochlorous acid in response to invading pathogens. Myeloperoxidase has been implicated in several chronic pathological diseases due to the chronic production of hypochlorous acid, as well as other reactive radical species. A high throughput screen and triaging protocol was developed to identify a reversible inhibitor of myeloperoxidase toward the potential treatment of chronic diseases such as atherosclerosis. The identification and characterization of a reversible myeloperoxidase inhibitor, 7-(benzyloxy)-3H-[1,2,3]triazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-5-amine is described.

Introduction

The myeloid hemoprotein myeloperoxidase (MPO) is a mammalian peroxidase that uniquely catalyzes the oxidation of chloride ion in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to generate hypochlorous acid (HOCl), a powerful oxidant. MPO can also act as a classical peroxidase, producing a wide range of free radicals and reactive oxidant species. MPO is synthesized in promyelocytes and promonocytes in the bone marrow and stored in the azurophilic granules of neutrophils where it constitutes 2–5% of total cellular protein content, and is present in lower abundance in subpopulations of monocytes and macrophages. MPO plays an important role in the immune system to help kill invading pathogens.1 Recent evidence supports a pathological role of MPO in various chronic inflammatory conditions;2–6 therefore, MPO inhibitors may be useful to treat inflammatory diseases including cardiovascular disease.

MPO has been implicated in cardiovascular disease in human clinical studies and by mechanistic work linking deleterious MPO oxidation of high density lipoprotein (HDL) and low density lipoprotein (LDL) to disease progression.3–7 MPO is expressed in the shoulder regions and necrotic core of human atherosclerotic lesions and active enzyme has been isolated from autopsy specimens of human lesions.8,9 Moreover, HOCl-modified HDL and LDL lipoproteins have been detected in advanced human atherosclerotic lesions.10–12 After isolation from atherosclerotic lesions, the HDL apolipoprotein, ApoA1, had chlorinated and nitrated tyrosine residues.3,5,13–15 Chlorotyrosine modifications of apoA1 are proposed to be specific biomarkers of MPO activity, and were shown to be associated with impaired cholesterol acceptor function.15,16 The lipid and protein content of LDL are also targets for MPO oxidation, and LDL particles exposed to MPO in vitro have impaired binding to the LDL-receptor. In the atherosclerotic plaque context, oxidized LDL is most likely taken up by macrophage scavenger receptors leading to macrophage foam cell formation.17 Further evidence implicating MPO in atherosclerosis pathophysiology comes from the study of hMPO transgenic mice crossed with LDL-R KO mice showing significantly larger aortic lesions than control LDL-R KO mice.18 Thus, MPO appears to play a role in the generation of oxidized, dysfunctional HDL and LDL, which contribute to atherosclerosis plaque development.

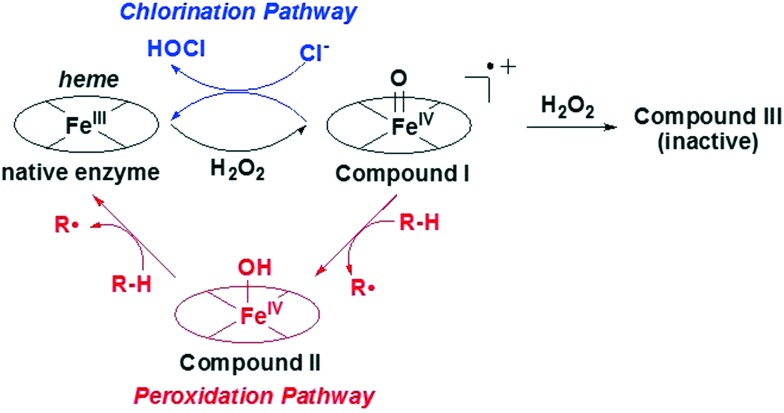

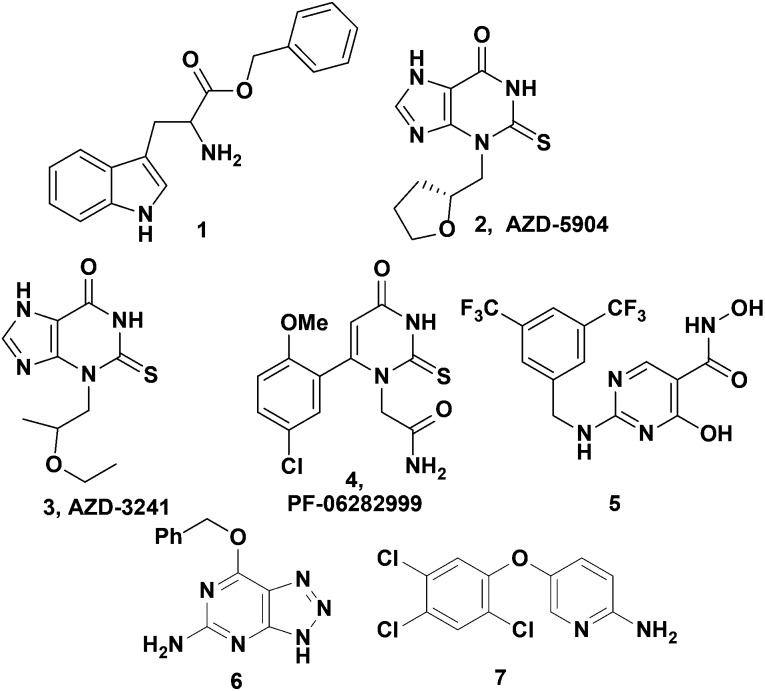

MPO exerts its biological activity predominantly via a pair of catalytic pathways (Fig. 1). The chlorination pathway starts by reaction of the Fe(iii) native enzyme with H2O2 to generate compound I, which contains two oxidizing equivalents more than the native enzyme (Fig. 1). Compound I has a high redox potential with the capacity to oxidize chloride ions to form HOCl and regenerate native enzyme. Alternatively in the peroxidase pathway, compound I is reduced by two consecutive one electron reduction steps via compound II intermediate back to the native enzyme. In these redox reactions a plethora of substrates can be oxidized to their corresponding free radicals. Substrate inhibitors such as tryptophan benzyl ester (1), indoles and nitroxides compete with chloride for oxidation by rapidly reacting with highly redox active compound I to form compound II and generating a radical intermediate.19–23 While compound II will persist with some substrates in vitro, it is likely a physiological substrate like tyrosine, urate, or ascorbate in the in vivo milieu would recycle compound II back to its native state. Irreversible inhibitors such as 2-thioxanthines (2,3) and 2-thiouracil 4 act in two steps by first generating a free radical intermediate from reaction with compound I, and then the radical forms a covalent linkage with the heme moiety resulting in permanent inactivation of MPO (Fig. 2).2,24,25 There is the potential for these free radical intermediates to be released from the active site and then react with other proteins.26 There have been limited reports of inhibitors such as the hydroxamic acid 5 that tightly bind at the MPO active site and function as reversible inhibitors of the enzyme; however 5 was also reported to be metabolized to nitroxide radicals thereby acting by a mixed mechanism.27 While several irreversible inhibitors (2–4) have progressed to clinical trials, and AZD-3241 (3) was reported in clinical trials for multiple systems atrophy, the efforts described herein were focused on the search for reversible MPO inhibitors to determine if potent inhibition could be obtained (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. MPO catalytic mechanism.

Fig. 2. Literature MPO inhibitors (1–5) and HTS hits (6, 7).

Results

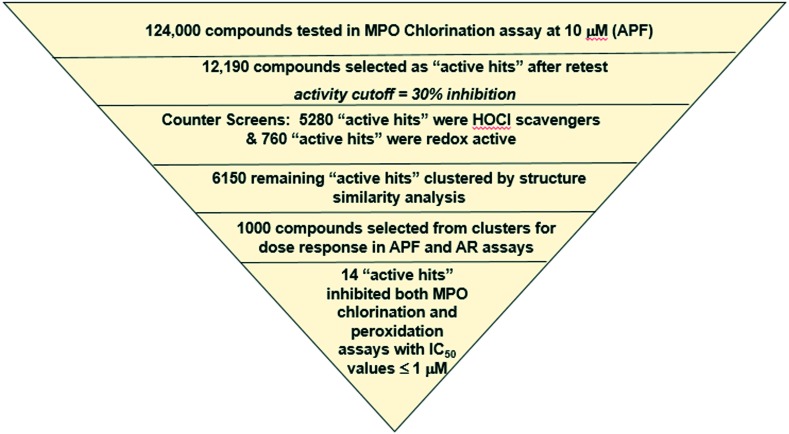

The goal of this project was to identify a stable reversible MPO inhibitor that would bind to the active site of the native enzyme and block its function without generating intermediate radicals. A screening tree based on this strategy was designed and tested on a 124 K compound collection (Fig. 3) for proof-of-concept purposes. The first screening assay was conducted with aminophenyl fluorescein (APF) to detect inhibition of MPO chlorination. After retests, 10% of the screening collection were identified as “active hits” at 10 μM. Two counter screens were employed to eliminate ∼50% of hits that were HOCl scavengers and redox active leaving 6150 “active hits”. After structure based clustering, 1000 hits were tested in dose response mode in the APF assay, and in an MPO peroxidase inhibition assay with amplex red (AR) detection and no chloride. To differentiate potent, irreversible inhibitors from reversible inhibitors, the reactions were carried out with and without a 10 minute pre-incubation step. Potent, irreversible inhibitors showed a strong shift toward increased potency in the APF assay with pre-incubation compared to no pre-incubation as demonstrated with AZD-5904 (Ex. 2, Table 1), which had a 6 fold increase in potency. Whereas, many MPO substrates had a potency loss in the AR assay compared to APF assay as shown with tryptophan benzyl ester (Ex. 1, Table 1), fourteen compounds of interest remained after this triaging process that inhibited both MPO-mediated chlorination and peroxidation reactions. Further mechanistic characterization was performed as described below for hits 6 and 7.

Fig. 3. HTS testing and triaging operations.

Table 1. In vitro MPO inhibitor profile.

| Ex. # | Human MPO APF assay w pre-inc IC50 μM | Human MPO APF assay w/o pre-inc IC50 μM | Human MPO AR assay w pre-inc IC50 μM | TPO IC50 μM | LPO IC50 μM | EPX IC50 μM | Mouse MPO APF assay w pre-inc IC50 μM | Neutrophil HOCl production IC50 μM |

| 1 | 0.2 ± 0.05 | 0.11 ± 0.026 | >13 | |||||

| 2 | 0.009 ± 0.001 | 0.056 ± 0.013 | 0.012 ± 0.002 | 3.9 (n = 1) | 1 (n = 1) | |||

| 6 | 0.11 ± 0.046* | 0.084 ± 0.033* | 0.11 ± 0.034 a | >30 | >30 | 0.015 ± 0.007* | 0.081 (n = 1) | 5 (n = 1) |

| 7 | 0.36 ± 0.11* | 0.32 ± 0.070* | 0.84 ± 0.32 a | 6.0 ± 1.6* | 13 ± 1.0 | 0.16 ± 0.063* | 0.23 (n = 1) | 1700 (n = 1) |

a n > 15. All other values were tested between 3 and 14 replicates unless otherwise indicated, and standard deviation is reported. Procedures are reported in ESI.

Neither 6 nor 7 appear to be irreversible inhibitors based on similar potency in the presence or absence of an enzyme-inhibitor preincubation step in the APF assay (Table 1). In order to confirm reversibility, pre-incubation jump dilution experiments were conducted under varying conditions of pre-incubation time, peroxide concentration and presence or absence of chloride, and the results clearly showed that inhibition by compound 6 was reversible compared to a known irreversible inhibitor (Fig. SI1. In ESI†).

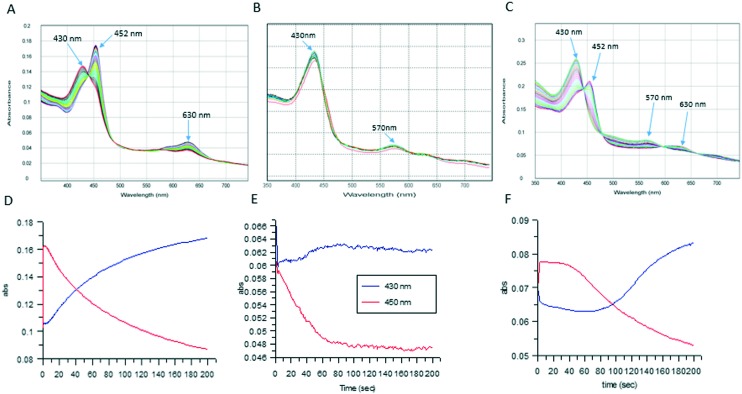

Stopped-flow experiments were conducted with MPO and inhibitors 6 and 7 to determine whether the compounds were truly inhibitors of MPO or behaving as slow substrates. The absorption spectrum of both native enzyme and compound I is characterized by a Soret band at 430 nm, while compound II and III absorb at 452 and 630 nm, respectively.28 Compound I was pre-formed by the incubation of MPO with a slight excess of H2O2 followed by rapid mixing with a solution of the MPO inhibitor plus peroxide. The amount of peroxide used in these experiments was purposely limiting to determine if the enzyme would return to its resting state upon consumption of this limiting substrate. As expected slow substrates such as tryptophan benzyl ester (1), showed an initial rapid increase in the 452 nm band for MPO along with a concomitant decrease in the 430 nm band and a small increase in absorbance at 630 nm (Fig. 4A and D).23 At longer incubation times, the 452 nm band decreased in intensity, and the 430 nm band increased indicating the reversion of the enzyme to its resting state after consumption of the available peroxide. Compound 7 showed a similar profile indicating it was a substrate for MPO (Fig. 4C and F); however, 7 had a prolonged plateau for the 450 nm peak compared with 1 indicating that 7 reacts more slowly with MPO contributing to its potency in the biochemical assays. In contrast, as shown in Fig. 4B and E, rapid mixing of compound 6 with MPO showed no change in the intensity of the 430 nm Soret band over 200 s, indicating no reaction occurred with the enzyme. The combination of the stopped-flow experiments and the reversibility experiments allowed us to identify reversible, unreactive inhibitors of MPO.

Fig. 4. A–C: Multiwavelength stopped-flow scans over 50 ms after mixing 1 uM MPO, 5 uM peroxide and 80 uM compound 1 (4A), 40 uM compound 6 (4B), and 7 (4C). D–F: Single wavelength traces from separate stopped-flow experiments showing the change in 430 nm and 450 nm wavelengths over 200 s after mixing for compound 1 (4D), 6 (4E), and 7 (4F).

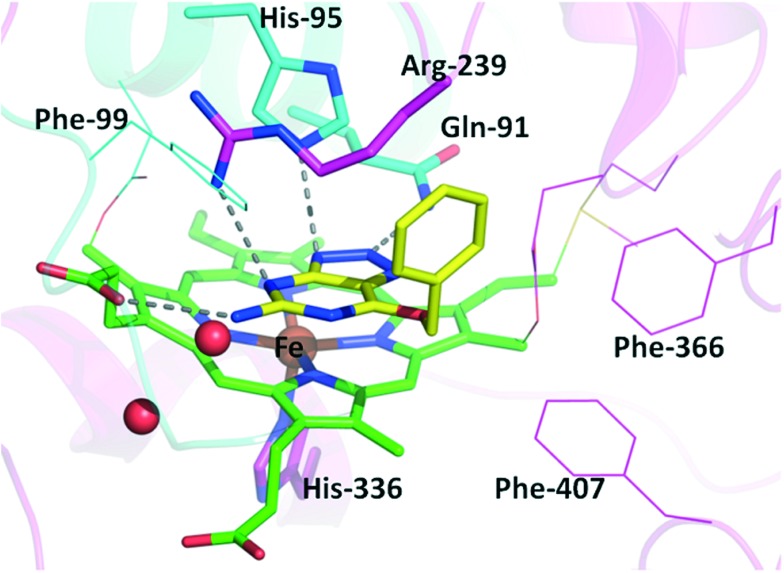

Crystallization of 6 with MPO provided additional evidence of native MPO enzyme inhibition with the inhibitor bound directly above the heme in a stacked fashion effectively filling the active site (Fig. 5). The triazolopyrimidine has three hydrogen bonds with the active site residues Gln-91, His-95 and Arg-239, effectively matching the polar amino acid residues in the active site. In addition the pendant amine interacts with a heme carboxylic acid. Further stabilizing the complex, the phenyl group has hydrophobic interactions with the Arg-239 methylenes. The orientation of the benzyl group is almost orthogonal to the benzyl in the reported structure of 5, showing different hydrophobic interactions provide affinity for 6.27

Fig. 5. Co-crystal structure of 6 with MPO. The carbons of compound 6 are colored in yellow and the carbons for heme are colored in green. Light chain residues of MPO are shown in cyan and heavy chain in magenta. Oxygens are colored red and nitrogens are blue. Hydrogen bonds are indicated with dashed lines.

Selectivity was assessed to ensure the inhibitors were not general heme binders. Compounds 6 and 7 were >10-fold selective compared to lactoperoxidase (LPO) and thyroid peroxidase (TPO) while potent inhibition of eosinophil peroxidase (EPX) was measured (Table 1). The compounds were also tested for inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP). Whereas 6 inhibited CYP3A4 with weak potency (IC50 = 14 μM), and had no inhibition against six other CYP enzymes, 7 demonstrated potent inhibition (IC50 < 0.1 μM) of CYPs 2B6 and 2C9.

The biological significance of the mechanistic and selectivity profiles exhibited by these compounds was studied in the following set of experiments. Inhibitors 2, 6 and 7 were tested in a dose-response for inhibition of HOCl production using human neutrophils isolated from healthy donor blood. Neutrophils were incubated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) to trigger neutrophil phagolysosome and NADPH oxidase complex assembly leading to MPO release from granules and H2O2 production. Formation of HOCl was quantified by luminol oxidation and resulting chemiluminescence was measured in kinetic mode. The irreversible inhibitor 2 and reversible inhibitor 6 demonstrated similar potency in human neutrophils, whereas the substrate inhibitor 7 was much less potent (Table 1). These results confirmed that in the cell milieu the availability of physiological substrate allowed recycling of the enzyme, and both reversible and irreversible inhibitors could efficiently block the enzyme activity.

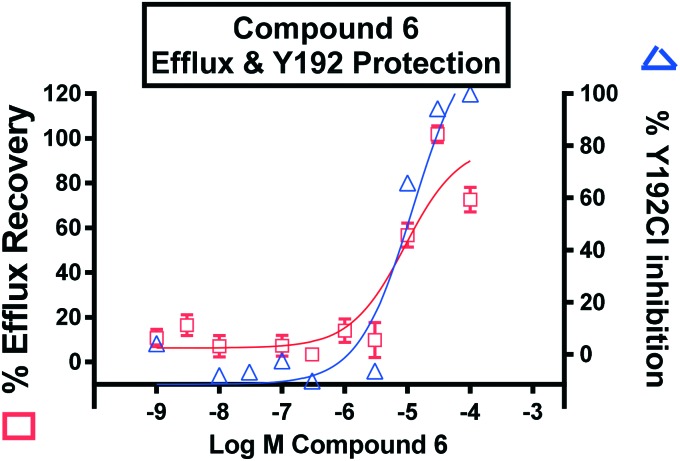

The ability of 6 to inhibit MPO mediated oxidation of a known physiological substrate ApoA1 was assessed by monitoring the formation of ApoA1 chlorotyrosine 192 (Y192Cl, Fig. 6) and oxidation of tryptophan 50 (W50ox) using a sensitive LC-MS/MS approach. In parallel, a cell-based cholesterol efflux assay using ApoA1 as the acceptor was carried out with MPO treated ApoA1 and varied concentrations of 6. As previously shown, MPO-mediated oxidation of ApoA1 impaired in vitro cholesterol efflux from macrophages.29–31 After treatment with inhibitor 6, an inverse correlation between the levels of chlorinated Y192Cl and oxidized W50ox ApoA1 residues, and the acceptor capability of ApoA1 to exchange cholesterol from THP-1 macrophages was observed with an EC50 value of 10 μM (Fig. 6 and ESI†). These observations support the concept of using an MPO reversible inhibitor to prevent MPO-mediated oxidation of ApoA1, and the impairment of ABCA1 cholesterol efflux pathway to counteract foam cell formation in the artery wall.

Fig. 6. Inhibition of MPO mediated chlorination by 6 (blue) rescued ApoA1 cholesterol efflux capacity (red).

The potential of 6 to inhibit MPO in mice was assessed using an acute neutrophil degranulation model with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) based on a similar method described by Gross, S. et al.32 Initially the model was validated by comparing the production of HOCl-mediated chemiluminescence in MPO KO versus wild type mice upon injection with PMA. No luminescence signal was detected from MPO KO plasma after PMA injection indicating the formation of oxidized luminol was dependent on MPO production of HOCl (Fig. SI3, ESI†).33 In wild type mice, PMA injection led to a rapid formation of luminol-dependent chemiluminescence that was inhibited ∼50 and 70% by pre-treatment with 6 dosed at 30 and 100 mpk, respectively (Fig. 7). These doses provided plasma concentrations of 180 and 460 μM at 20 minutes, which is 36 and 92 fold higher than the potency in the human in vitro neutrophil PMA assay (Table 1), likely due in part to plasma protein binding (87% bound in mouse). The potency to inhibit mouse and human MPO in the APF assay was similar (Table 1). While a full-dose response in mice was not determined to correlate in vitro and in vivo potency, this result confirmed that an MPO reversible inhibitor can block the enzymatic production of HOCl in vivo.

Fig. 7. Inhibition of MPO-mediated formation of HOCl after dosing 6 at 30 and 100 mpk as measured by luminol chemiluminescence. *P < 0.05, vs. vehicle, t test.

Initial SAR focused on investigating the triazolopyrimidine core to determine the critical interactions to maintain activity (Fig. 8). Changes to the pendant amino group resulted in a loss of potency as observed for the pyrimidine 8, pyrimidinol 9, and pyrimidine alkyl amine 10. Methylation of the triazole at any position caused loss of MPO inhibition (11, 12). The purine analogs (13–14) and indazole 15 had a loss of activity, indicating the pKa of the triazolopyrimidine (pKa = 6.6) may be important for the binding.

Fig. 8. SAR of the triazolopyrimidine core of lead 6.

Interactions with the hydrophobic pocket were best maintained with the benzyl ether lead, which had better activity than the phenyl ether (16), or phenethyl ether (17, Table 2). Small substituents on the pendant benzyl had similar potency in the APF assay, with small electron withdrawing fluorine substitutions trending toward increased potency (18, 21, 25), and the methyl or methoxy substitutions showing a modest reduction in potency (20, 23, 27, Table 2). Inhibitor 6 has been described in the literature as a reactive inhibitor of methyl guanine methyl transferase (MGMT),34 and subsequent publications will address optimization of MPO potency and efforts to remove the reactivity with MGMT by optimizing the benzyl ether.

Table 2. Ether substitution and MPO inhibition.

| |||

| Ex. # | n | R | APF assay w pre-inc IC50 a μM |

| 16 | 0 | H | >13 |

| 17 | 2 | H | 0.63 |

| 18 | 1 | 2-F | 0.078 |

| 19 | 1 | 2-Cl | 0.18 |

| 20 | 1 | 2-CH3 | 0.47 |

| 21 | 1 | 3-F | 0.040 |

| 22 | 1 | 3-Cl | 0.20 |

| 23 | 1 | 3-OMe | 0.49 |

| 24 | 1 | 3-OCF2H | 0.20 |

| 25 | 1 | 4-F | 0.047 |

| 26 | 1 | 4-CF3 | 0.14 |

| 27 | 1 | 4-CH3 | 0.51 |

aAssay was run n = 1 or 2 for each compound.

Conclusions

A triazolopyrimidine reversible inhibitor of MPO was identified using a carefully constructed HTS testing protocol. While many substrate and irreversible inhibitors of MPO have been reported, compound 6 is the first non-reactive MPO inhibitor reported. The reversible, non-reactive nature of inhibitor 6 was confirmed using multiple types of mechanism studies. The crystallographic data is consistent with this conclusion and provides some indication of the important protein-inhibitor contacts that are necessary for potency. Compound 6 can inhibit the in vitro chlorination of ApoA1, which is thought to be deleterious toward atherosclerotic plaque formation, and the neutrophil production of HOCl in an acute mouse model. Further optimization of MPO inhibitory potency and the selectivity for MPO over MGMT would be required for progression to a lead compound for chronic in vivo studies.

Abbreviations

- ApoA1

Apolipoprotein A1

- APF

Aminophenyl fluorescein

- AR

Amplex red

- CYP

Cytochrome P450

- EPX

Eosinophil peroxidase

- HDL

High density lipoprotein

- HTS

High throughput screening

- LDL

Low density lipoprotein

- LPO

Lactoperoxidase

- MGMT

Methyl guanine methyl transferase

- MPO

Myeloperoxidase

- PMA

Phorbol myristate acetate

- Pre-inc

Preincubation

- RT

Retest

- SAR

Structure activity relationship

- TPO

Thyroid peroxidase

- w pre-inc

With preincubation

- w/o pre-inc.

Without preincubation

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: General synthetic methods, key compound characterization, assay methods, and crystallographic information are available in the ESI. See DOI: 10.1039/c7md00268h

References

- Klebanoff S. J. Science. 1970;169:1095. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3950.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M., Pulli B., Courties G., Tricot B., Sebas M., Iwamoto Y., Hilgendorf I., Schob S., Dong A., Zheng W., Skoura A., Kalgukar A., Cortes C., Ruggeri R., Swirski F. K., Nahrendorf M., Buckbinder L., Chen J. W. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2016;1:633. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., DiDonato J. A., Levison B. S., Schmitt D., Li L., Wu Y., Buffa J., Kim T., Gerstenecker G. S., Gu X., Kadiyala C. S., Wang Z., Culley M. K., Hazen J. E., Didonato A. J., Fu X., Berisha S. Z., Peng D., Nguyen T. T., Liang S., Chuang C. C., Cho L., Plow E. F., Fox P. L., Gogonea V., Tang W. H., Parks J. S., Fisher E. A., Smith J. D., Hazen S. L. Nat. Med. 2014;20:193. doi: 10.1038/nm.3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikitimur B., Karadag B. Future Cardiol. 2010;6:693. doi: 10.2217/fca.10.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao B., Pennathur S., Heinecke J. W. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:6375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.337345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Veen B. S., de Winther M. P., Heeringa P. Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2009;11:2899. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutter D., Devaquet P., Vanderstocken G., Paulus J. M., Marchal V., Gothot A. Acta Haematol. 2000;104:10. doi: 10.1159/000041062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty A., Dunn J. L., Rateri D. L., Heinecke J. W. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;94:437. doi: 10.1172/JCI117342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama S., Okada Y., Sukhova G. K., Virmani R., Heinecke J. W., Libby P. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;158:879. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64036-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delporte C., Boudjeltia K. Z., Noyon C., Furtmuller P. G., Nuyens V., Slomianny M. C., Madhoun P., Desmet J. M., Raynal P., Dufour D., Koyani C. N., Reye F., Rousseau A., Vanhaeverbeek M., Ducobu J., Michalski J. C., Neve J., Vanhamme L., Obinger C., Malle E., Van Antwerpen P. J. Lipid Res. 2014;55:747. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M047449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell L. J., Arnold L., Flowers D., Waeg G., Malle E., Stocker R. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:1535. doi: 10.1172/JCI118576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen S. L., Heinecke J. W. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:2075. doi: 10.1172/JCI119379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDonato J. A., Huang Y., Aulak K. S., Even-Or O., Gerstenecker G., Gogonea V., Wu Y., Fox P. L., Tang W. H., Plow E. F., Smith J. D., Fisher E. A., Hazen S. L. Circulation. 2013;128:1644. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennathur S., Bergt C., Shao B., Byun J., Kassim S. Y., Singh P., Green P. S., McDonald T. O., Brunzell J., Chait A., Oram J. F., O'Brien K., Geary R. L., Heinecke J. W. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:42977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao B., Tang C., Sinha A., Mayer P. S., Davenport G. D., Brot N., Oda M. N., Zhao X. Q., Heinecke J. W. Circ. Res. 2014;114:1733. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Nukuna B., Brennan M. L., Sun M., Goormastic M., Settle M., Schmitt D., Fu X., Thomson L., Fox P. L., Ischiropoulos H., Smith J. D., Kinter M., Hazen S. L. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:529. doi: 10.1172/JCI21109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podrez E. A., Febbraio M., Sheibani N., Schmitt D., Silverstein R. L., Hajjar D. P., Cohen P. A., Frazier W. A., Hoff H. F., Hazen S. L. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105:1095. doi: 10.1172/JCI8574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani L. W., Chang J. J., Wang X., Lusis A. J., Reynolds W. F. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:1366. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600005-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allegra M., Furtmuller P. G., Regelsberger G., Turco-Liveri M. L., Tesoriere L., Perretti M., Livrea M. A., Obinger C. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;282:380. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz R. F., Vaz S. M., Augusto O. Biochem. J. 2011;439:423. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees M. D., Bottle S. E., Fairfull-Smith K. E., Malle E., Whitelock J. M., Davies M. J. Biochem. J. 2009;421:79. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soubhye J., Aldib I., Elfving B., Gelbcke M., Furtmuller P. G., Podrecca M., Conotte R., Colet J. M., Rousseau A., Reye F., Sarakbi A., Vanhaeverbeek M., Kauffmann J. M., Obinger C., Neve J., Prevost M., Zouaoui Boudjeltia K., Dufrasne F., Van Antwerpen P. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:3943. doi: 10.1021/jm4001538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliskovic I., Abdulhamid I., Sharma M., Abu-Soud H. M. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2009;47:1005. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri R. B., Buckbinder L., Bagley S. W., Carpino P. A., Conn E. L., Dowling M. S., Fernando D. P., Jiao W., Kung D. W., Orr S. T., Qi Y., Rocke B. N., Smith A., Warmus J. S., Zhang Y., Bowles D., Widlicka D. W., Eng H., Ryder T., Sharma R., Wolford A., Okerberg C., Walters K., Maurer T. S., Zhang Y., Bonin P. D., Spath S. N., Xing G., Hepworth D., Ahn K., Kalgutkar A. S. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:8513. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiden A. K., Sjogren T., Svensson M., Bernlind A., Senthilmohan R., Auchere F., Norman H., Markgren P. O., Gustavsson S., Schmidt S., Lundquist S., Forbes L. V., Magon N. J., Paton L. N., Jameson G. N., Eriksson H., Kettle A. J. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:37578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.266981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J., Spath S. N., Pabst B., Carpino P. A., Ruggeri R. B., Xing G., Speers A. E., Cravatt B. F., Ahn K. Biochemistry. 2013;52:9187. doi: 10.1021/bi401354d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes L. V., Sjogren T., Auchere F., Jenkins D. W., Thong B., Laughton D., Hemsley P., Pairaudeau G., Turner R., Eriksson H., Unitt J. F., Kettle A. J. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:36636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.507756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furtmuller P. G., Zederbauer M., Jantschko W., Helm J., Bogner M., Jakopitsch C., Obinger C. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2006;445:199. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergt C., Fu X., Huq N. P., Kao J., Heinecke J. W. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:7856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309046200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borja M. S., Zhao L., Hammerson B., Tang C., Yang R., Carson N., Fernando G., Liu X., Budamagunta M. S., Genest J., Shearer G. C., Duclos F., Oda M. N. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Settle M., Brubaker G., Schmitt D., Hazen S. L., Smith J. D., Kinter M. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross S., Gammon S. T., Moss B. L., Rauch D., Harding J., Heinecke J. W., Ratner L., Piwnica-Worms D. Nat. Med. 2009;15:455. doi: 10.1038/nm.1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brestel E. P. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1985;126:482. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90631-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae M. Y., Swenn K., Kanugula S., Dolan M. E., Pegg A. E., Moschel R. C. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:359. doi: 10.1021/jm00002a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.