Abstract

In early embryos, microtubules form star-shaped aster structures that can measure up to hundreds of micrometres, and move at high speeds to find the geometrical centre of the cell. This process, known as aster centration, is essential for the fidelity of cell division and development, but how cells succeed in moving these large structures through their crowded and fluctuating cytoplasm remains unclear. Here, we demonstrate that the positional fluctuations of migrating sea urchin sperm asters are small, anisotropic, and associated with the stochasticity of dynein-dependent forces moving the aster. Using in vivo magnetic tweezers to directly measure aster forces inside cells, we derive a linear aster force-velocity relationship and provide evidence for a spring-like active mechanism stabilizing the transverse position of the asters. The large frictional coefficient and spring constant quantitatively account for the amplitude and growth characteristics of athermal positional fluctuations, demonstrating that aster mechanics ensure noise suppression to promote persistent and precise centration. These findings define generic biophysical regimes of active cytoskeletal mechanics underlying the accuracy of cell division and early embryonic development.

Microtubule asters are star-shaped cytoskeletal structures composed of microtubule polymers radiating from an organizing center called the centrosome. They contribute to the spatial organization of crucial functions in eukaryotic cells, ranging from cell migration to nuclear centration and mitotic spindle orientation 1–3. One highly conserved property of microtubule asters is their ability to probe the geometrical boundaries of the cell to move and position themselves in the exact cell center. This was best highlighted in seminal in vitro work reconstituting aster growth and centration in microfabricated wells of a few microns in size. In those studies, pushing forces resulting from astral microtubule polymerization against the chamber wall 4,5 or pulling forces provided by minus-end directed dynein motors attached to the wall surface 6 allowed asters to target the chamber center.

A stereotypical and ubiquitous in vivo counterpart for aster centration occurs soon after fertilization in most animal embryos 7. In this context, the fertilizing sperm brings the male pro-nucleus and its associated centrosomal material into the side of the egg, which results in the nucleation of a “sperm aster” that continuously grows and moves to the egg center. This centration motion is critical to position the nucleus and subsequent spindle and division plane in the exact cell center. Contrary to in vitro situations, studies in systems including worm, frog, fish, and echinoderm embryos have suggested that aster centration in those cells may not primarily involve microtubule polymerization or cortical dynein forces 8–12. Rather, a prominent model is that most of the forces are provided by dynein motors working along astral microtubules in bulk cytoplasm 11,13–15. Dynein motors generate plus-end directed traction forces, probably as complexes with endomembrane components such as the endoplasmic reticulum, lysosome vesicles or yolk granules13,14, via frictional interactions with the viscous cytoplasm. As longer microtubules may associate with more cargos, they may exert larger pulling forces on the centrosome. This length-dependent system, coupled to microtubule length asymmetries caused by cellular boundaries, provides a self-organization design for asters to target the cell center 11,15–17.

One outstanding physical problem posed by aster centration in early embryos arises from the unusually large size of egg cells and early blastomeres 3,18. These cells are typically 10-100 times larger than somatic cells 19 or in vitro microchambers 6, yet achieve aster centration on a time-scale of only a few tens of minutes. Because of the physiological importance of aster centration in early embryos, these parameters set extreme constraints on motion persistency, speed, and centering precision. Given cytoplasmic crowding, extrinsic cellular noise, and intrinsic stochasticity of molecular elements involved 20,21, how moving asters may satisfy those constraints inside cells remains mysterious overall.

Here we exploited the centration of sea urchin sperm asters as a quantitative model system to derive the biophysical principles ensuring robust aster centration. By combining high-resolution tracking and direct intracellular aster force measurement, we find that aster motion is associated with large forces and small active positional fluctuations. This work demonstrates how aster mechanics may ensure noise-suppression to promote persistent and precise centration.

We first employed high-resolution microscopy (spatial resolution ~20 nm, temporal resolution ~50 ms, see methods) (Fig. S1-2 and movie S1) to track the motion of male pro-nuclei attached to sperm microtubule asters in fertilized sea urchin eggs. We confirmed that aster speed was, on average, constant along the longitudinal centering direction (X-axis) and zero along the transverse axis (Y-axis) 11. Aster trajectory appeared smooth overall, but did exhibit some minor excursions away from the centering axis, which rapidly resorbed (Fig. 1, a and b).

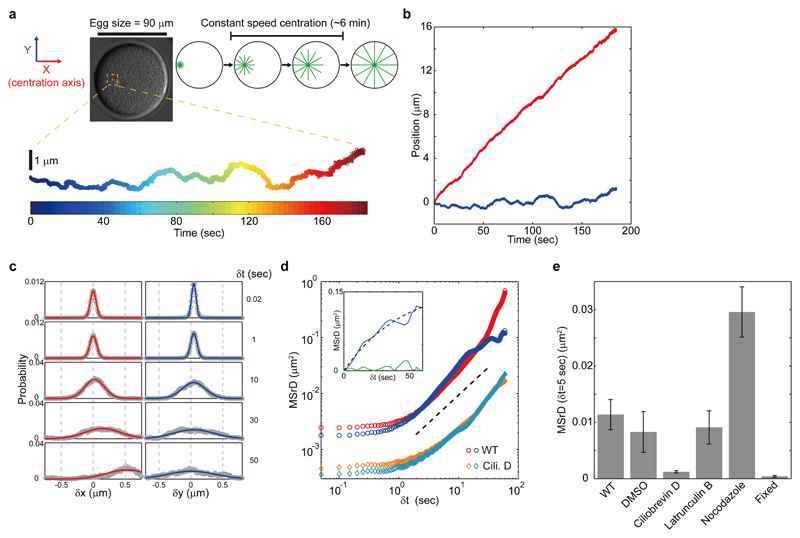

Fig. 1. Fluctuation analysis of centering microtubule asters.

(a and b) High-resolution tracking of sperm microtubule asters during the constant speed centration phase. The representative 3 min trajectory corresponds to 3600 time points. Aster XY position was defined using X as the centering axis. (c) PDFs of residual displacements along X and Y for different δt. Bold lines are best-fit Gaussian distributions. (d) X and Y MSrDs for control and Ciliobrevin D-treated samples plotted as a function of δt in log scale. The broken line indicates a slope of 1. Inset: Transverse MSrD (blue curve) of controls superimposed with a fit of the model from Eq. 1 (broken line), plotted on a linear scale. The absolute magnitude of the residual error between the fit and the data is also depicted (green curve). (e) Contributions of cytoskeletal components to aster positional fluctuations. The fluctuation amplitude was characterized by computing the MSrD at δt=5 sec. Error bars represent standard deviations.

To quantitatively examine the stochastic fluctuations around the mean motion, we detrended aster trajectory by subtracting its local velocity and computed the residual displacements, δX and δY, as a function of lag time, δt (eq. S2) 22. The probability distribution functions (PDFs) of δX and δY were nearly similar for δt < 30 sec, and were well described by Gaussian functions (Fig. 1c). For δt > 30 sec, while the PDF of δY kept a near-constant shape, the PDF of δX appeared to deviate from a Gaussian and had a non-zero mean, which could reflect more complex behaviors such as higher order slow changes in the aster mean speed.

We characterized the statistical properties of aster fluctuations by plotting the second order moment of δX and δY (mean-squared residual displacement, MSrD) as a function of δt (Fig. 1d). Both MSrDs were flat at δt < 1 sec, due to measurement noise. They then grew linearly above the measurement noise with a slope close to 1 for 1 < δt < 30 sec, suggesting diffusive dynamics with similar diffusion coefficients along both axes: Dx = 1.7*10-3 μm2/sec and Dy = 1.8*10-3 μm2/sec. These results indicate the existence of uniform random forces which cause asters to fluctuate in a diffusive manner.

The two MSrDs had different behaviors at δt > 30 sec. While the longitudinal fluctuations kept growing, the transverse fluctuations saturated, likely reflecting a positional feedback that stabilizes aster trajectory transversely (Fig. 1d). Accordingly, these transverse fluctuations were well described by a random walk under spring-like restoration forces (Fig. 1d, inset) 23, so that

| (Eq. 1) |

with a saturation amplitude 2τDy = 0.17 μm2 and saturation timescale τ = 46 sec. This corresponded to the typical size and restoration time of excursion events away from the centering axis. The saturation amplitude allowed for estimating a mean deviation distance of the aster from the centering axis of which was typically less than 1% of the cell radius, demonstrating a remarkable centration precision. Thus, aster fluctuations are small and anisotropic with characteristics determined by a balance between random forces and viscous dampening, and additional spring-like feedback in the transverse axis.

To discern if the observed fluctuations reflected thermal noise or active processes, we manipulated cytoskeletal components using specific chemical inhibitors (Fig. 1, d and e and Fig. S3-4). To separately characterize the diffusive fluctuations from the effects of positional feedback, we computed a fluctuation amplitude defined as MSrD at δt=5 sec, where asters exhibit purely diffusive behavior. Strikingly, addition of 100 μM of Ciliobrevin D, which inhibits dynein activity and halts aster motion without grossly altering aster growth and morphology 11 (Fig. S3), decreased positional fluctuation amplitude by almost an order of magnitude. Thus, dynein force-generation events which drive aster centration may also add active noise to this motion because of their stochastic nature. Actin depolymerization with 20 μM Latrunculin B affected cell cortex and cell shape 11, but did not affect aster motion or fluctuation amplitude. This suggests that dynein drives aster fluctuations within the bulk cytoplasm not from the cortex, and by associating with cytoplasmic elements independent of actin 23,24. Finally, treatment with 20 μM Nocodazole to depolymerize microtubules also halted aster motion, but caused the sperm nucleus to fluctuate more than in controls, suggesting that microtubules may contribute to a large fraction of aster viscous drag. Importantly, in Nocodazole and Ciliobrevin D treatments, longitudinal and transverse MSrDs both grew diffusively for the entire timescale without saturation (Fig. 1d and fig. S4). This indicates that microtubules and dynein contribute to the transverse spring-like feedback.

To understand how those kinetic properties may emerge from the mechanical properties of moving asters, we set out to directly measure the physical forces of asters inside cells. We modified a magnetic tweezer strategy recently used to measure forces for mitotic spindle maintenance in C. elegans 25 to be able to apply larger forces of several hundreds of pN to moving asters in arbitrary directions. These modifications rested on the injection of magnetic beads with highly persistent minus-end targeting activity, which rapidly aggregated and bound to the aster center upon fertilization in a microtubule- and dynein-dependent manner 26. Application of large calibrated forces was achieved by bringing a sharpened steel piece connected to a magnet to a controlled distance from the internalized beads (Fig. 2a and figs. S5 to S9) (see supplementary information).

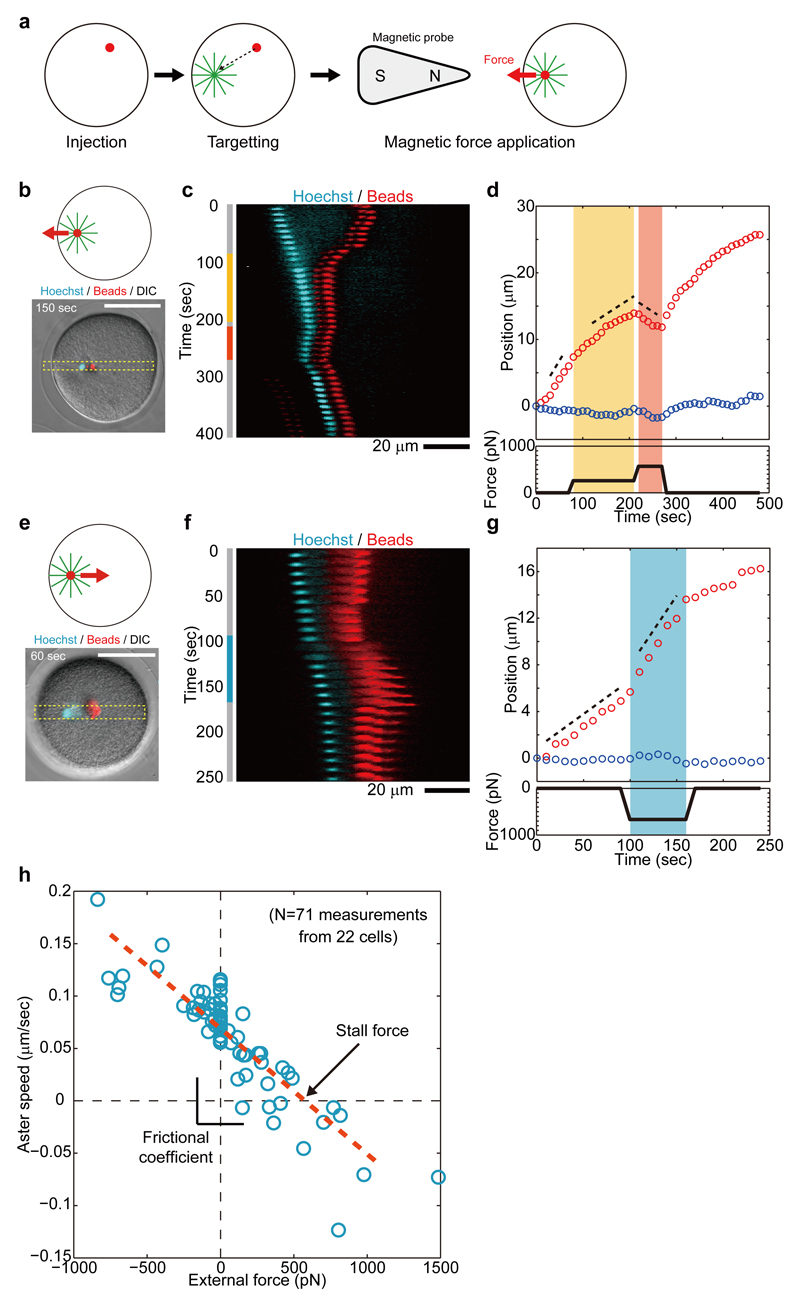

Fig. 2. Force-velocity relationships of microtubule asters.

(a) Aggregates of injected magnetic beads were targeted to the aster center to directly apply magnetic forces to centering asters. (b-g) External magnetic forces were applied to asters either against (b-d) or along (e-g) the centering direction. The 1D kymographs (c and f) and time-evolution of aster XY positions (d and g) show how applied forces consistently change aster longitudinal speed. (h) Aster longitudinal speed Vx plotted as a function of external force amplitude. N=71 measurements from 22 cells. The red broken line indicates a linear fit.

Application of external longitudinal forces against aster-centering motion caused aster speed to decrease in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2, b-d, Fig. S10 and movie S2). In these experiments, we focused on a short timescale response by computing aster speed within typically ~ 30 sec after force application, to minimize long-term adaptive responses. In Fig. 2b-d, we first applied a 260 pN force, which dropped aster longitudinal speed Vx by almost a factor 2 without altering Vy. This force was subsequently increased to 570 pN which further decreased Vx to a negative value, thus reverting aster motion. After the force was released, the aster restored a centering velocity close to its original value, suggesting that external forces did not grossly perturb aster organization. Conversely, applying external forces along the centering direction caused asters to accelerate (Fig. 2, e-g, Fig. S11 and movie S3). In Fig. 2e-g, we applied a 670 pN force in the positive X direction which increased aster speed by nearly 2-fold.

Systematic repetition of these measurements allowed the derivation of an aster force-velocity relationship for a wide range of external forces, from +1500 pN to –700 pN (a positive force corresponds to a rear pull). Consequent changes in longitudinal aster speed Vx varied from -0.13 to 0.2 μm/sec and collapsed into a single linear curve (Fig. 2h and fig. S12). These results indicate that aster motion is governed by a simple linear friction law, so that:

| (Eq. 2) |

Importantly, this linear relationship holds for external forces applied along and against aster centering motion, suggesting that contributions from compressive microtubule forces at the aster rear, close to the cortex, may be negligible here. Using those results, we determined an aster stall force which is equal to the aster endogenous force of Faster = 580 +/- 21 pN, and a frictional coefficient γ of 8400 +/- 280 pN*sec/μm (+/- indicates the standard error in fitting parameters unless specified). Detached bead aggregates with a similar size to the male pro-nucleus moved much faster than asters under the same forces, indicating that most of this friction may be associated with microtubules in the aster (fig. S6). These results demonstrate that the centering motion of sperm asters obeys a simple linear friction law involving large self-propelling forces and drag.

Fluctuation analyses in the transverse axis supported the existence of a spring-like feedback mechanism stabilizing aster position around the centering axis. To characterize this feedback, we applied magnetic forces perpendicular to the motion direction (Fig. 3a and b, fig. S13 and movie S4). In Fig. 3a-b, we applied a 470 pN force in the Y positive direction for 140 sec. The external force did not affect aster motion along the X-axis, but caused a continuous drift in Y which eventually saturated ~7 μm away from the X-axis. Remarkably, after force cessation the Y position restored to its original value within tens of seconds (Fig. 3b). Computing the maximum Y-displacement at saturation as a function of various applied forces yielded a linear force-displacement curve (Fig. 3c). These results directly demonstrate the existence of a linear spring stabilizing aster position around the centration axis, with a spring constant of κ = 59 +/- 2.8 pN/μm. The stiffness of this spring is ~4 times higher than in C. elegans 25, plausibly revealing different force-generation mechanisms. Accordingly, the transverse speed Vy following force application was comparable to the changes in Vx in the longitudinal force experiments, ruling out a major contribution of microtubule compressive forces to this transverse feedback. In addition, it has been shown that aster laser severing along the transverse axis in this system yields aster motion away from the site of ablation 11. These data support that this centering spring is mostly associated with microtubule pulling forces.

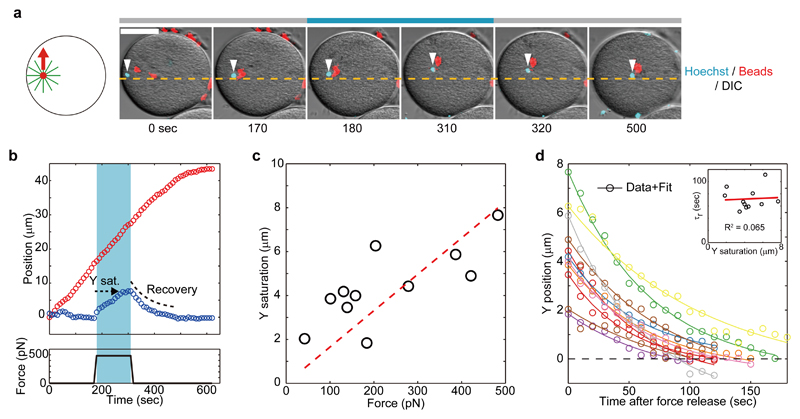

Fig. 3. Direct demonstration of a transverse feedback stabilizing asters along their centering direction.

(a and b) External forces were applied orthogonally to the centering direction along the Y-axis for 140 sec. The applied force causes a drift towards the magnet tip. (c) Aster Y saturation (shown in b) plotted as a function of external force amplitude. N=10 measurements from 10 cells. The spring constant κ=59 pN/μm was determined from the slope of the linear fit (red broken line). (d) Recovery dynamics of aster Y position. Aster Y position after force cessation was plotted as a function of time. N=10 measurements from 10 cells. Solid lines indicate best fits with exponential function (eq. S6), yielding a mean recovery timescale τr = 72 +/- 18 sec. Inset: Recovery timescale plotted as a function of Y saturation. The correlation analysis indicates that there is no correlation between the two variables.

These transverse force experiments are consistent with a Kelvin–Voigt model, in which an elastic spring and viscous dashpot are connected in parallel 25 (Fig. 4). This model predicts that the mean-squared displacement driven by internal random forces should saturate in an exponential manner, as observed in fluctuation analysis, with a timescale equal to the relaxation timescale upon displacement by an external load. Accordingly, quantification of the recovery dynamics after force cessation revealed a restoring kinetic well described by an exponential relaxation with a single characteristic timescale, τr = 72 +/- 18 sec (+/- indicates standard deviation), independent of the initial Y-offset (Fig. 3d). This timescale was close to the saturation timescale observed in the transverse fluctuations (τ = 46 sec), supporting the consistency between our passive and active characterizations of the transverse positional feedback. Given that fluctuation saturation depended on microtubules and dynein, these results suggest that the positional feedback maintaining the aster around the centering axis relies on dynein pulling forces on microtubules.

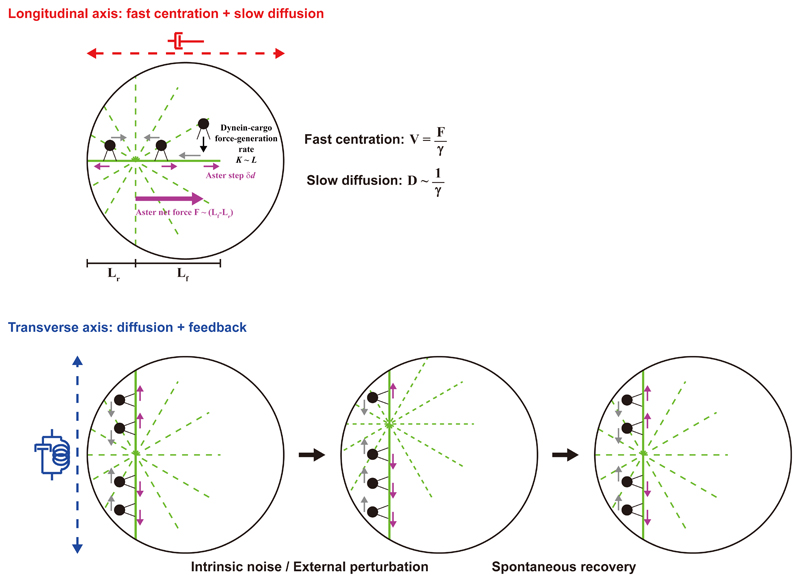

Fig. 4. Aster mechanics ensure fast, persistent and precise aster centration.

The large frictional coefficient of asters suppresses active fluctuations along the longitudinal axis. This process was analyzed using a simple Poisson model, in which a single dynein-force generation event causes an aster step motion (see main and supplementary text). Given this large drag, asters must exert large net endogenous forces to move at high speed in the cytoplasm. Along the transverse axis, fluctuations are further suppressed by a dynein-dependent feedback mechanism, which stabilizes the centering direction with respect to cell geometry.

These findings may be consistent with the length-dependent mechanism proposed to drive aster centration in sea urchins and other embryos 8–13,15,16,27,28. This system has the properties of an ‘active spring’ with respect to cell geometry: a displacement away from the cell center yields a length imbalance on the two sides of the aster and creates a dynein-dependent restoration force proportional to the displacement 8. During aster centration, this spring is expected to function only along the transverse axis, because MTs reach the cortex along this axis, while front MTs do not reach to the opposite side until the very end of centration (Fig. 4) 11. Using the simplest linear length-dependency for microtubule forces, FMT = αLMT, we can relate the spring constant κ to the length-dependency factor, α, so that α = κ/2. This analysis indicates that ~30 pN forces are generated per 1 μm-depth region of the aster surface (corresponding to a volume of 5*103 μm3 for an aster radius of 20 μm). This suggests a lower bound of 100-200 dynein motors involved in moving and positioning these asters, much higher than in previous indirect estimates 15,29.

Aster mechanical properties along the two different axes appeared to be largely consistent. For asters to move to the cell center, front microtubules should be longer than those at the back, because their growth is not restricted by the cortex. We recently estimated a difference in length between front and rear microtubules of about δL ~ 10 μm 11. This would correspond to a net force of Faster = αδL ~ 300 pN; smaller yet close to the direct longitudinal force measurement calculated above. Furthermore, the relaxation timescale in the transverse force experiments allows for defining a frictional coefficient given by γ = κ ∙ τr = 4200 pN*sec/μm. This value is comparable to but twice smaller than that obtained from direct measurements in the longitudinal axis. Because the time-window used to compute the frictional coefficient in the transverse axis (>100 sec) is larger than in the longitudinal axis (~30 sec), we envision that the differences in γ could reflect some shape changes of the aster, which could modify the effective drag over this longer timescale. Together, these findings indicate that the viscous dampening in the transverse position is essentially the same as the drag associated with aster longitudinal centering motion, and that length-dependent dynein-MT forces may account for both transverse feedback and net centering force.

The frictional coefficient of MT asters is remarkably high, 60 times larger than the measured value for static mitotic spindles in C. elegans and 15 times larger than indirect estimates for sperm asters in C. elegans 25,30. This value suggests that the cell dedicates an energy of at least γV2 ~ 1000 ATP molecules/sec for centering microtubule asters. Based on the measured cytoplasmic viscosity of fertilized sea urchin eggs 31, this friction would amount to that of an object with a hydrodynamic radius of ~440 μm, typically ~20 times larger than the aster physical radius. Such large friction may not be readily explained by internal structures in the aster. Indeed, given the high density of astral MTs, their association with endomembranes such as the endoplasmic reticulum 15, an aster may be viewed as a sphere with low permeability 32,33. The frictional coefficient of asters is thus expected be close to that of a non-permeable counterpart, and much smaller than the sum of the drag of individual microtubules. One possible source for such a large frictional coefficient is the confinement set by the cell boundary: the hydrodynamic interaction between the aster and cell boundaries could significantly reduce the hydrodynamic mobility of the aster. In support of this, recent quantitative hydrodynamic simulations suggest that even a moderate cell-confinement (aster/cell size ~ 0.5) can lead to a 10-30 times increase of aster frictional coefficient 33. Our experimental results may thus highlight the overlooked physical effect of cell-confinement on the mobility of intracellular structures.

Finally, we propose a simple model which explains how measured mechanical properties may account for aster positional fluctuations. Aster motion kinetics can be represented by one length-scale defined by dividing the diffusion coefficient by the mean speed, Dx/Vx = 20 nm. This small length-scale reflects the high persistency of aster motion. To illustrate how this characteristic length-scale may emerge from aster mechanics, we introduce a simple model for aster longitudinal motion (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Material). In this model, a single force-generation event created by a moving dynein on a microtubule causes a fixed aster displacement, δd, towards or away from the cell center. We assume that force-generation obeys a first-order reaction, (i.e. it is limited by either the binding or the activation of dynein), with a reaction rate Kf (Kr) proportional to the front (rear) aster radius Lf (Lr). Using Poisson statistics 34, we can express δd as a function of Dx/Vx as (see Supplementary Material):

| (Eq. 3) |

Assuming force balance between the aster and a single dynein-cargo complex, and using typical cargo vesicle parameters (radius r ~ 0.5 μm and run-length l ~ 5 μm 11) and aster shape asymmetry Lr/Lf ~ 0.8 11, this model predicts an aster hydrodynamic radius as R = (l⋅r)/δd ~620 μm, which is comparable to our direct measurement of ~440 μm. This result demonstrates how the large aster frictional coefficient may suppress the motion error caused by dynein active fluctuations.

Owing to unusually large endogenous forces and friction, aster centration in large cells of early embryos is thus extremely precise, significantly more so than in well-controlled in vitro aster centration assays4–6. The large frictional coefficient enables asters to take an ensemble average of stochastic dynein force generation events and ensures motion persistency. The transverse feedback further suppresses those fluctuations and can even bring back the aster along its centering trajectory after accidental deviations larger than those caused by dynein fluctuations (Fig. 3). Most fertilizing embryos are associated with rotational flows, shape changes and other cytoplasmic re-organization7. MT asters in early embryos may thus be equipped with near-optimal physical designs to stabilize their motion in such an unfavorable environment to rapidly and precisely target the geometrical center of large cells.

Methods

Sea urchin gametes

Purple sea urchins (Paracentrotus lividus) were obtained from either L’Oursine de Ré or the Roscoff Marine station, and maintained in aquariums. Artificial sea water (ASW; Reef Crystals, Instant Ocean) was used for adult maintenance in aquariums, and embryo development. Gametes were collected by intracoelomic injection of 0.5 M KCl. Dry sperm was kept at 4°C and used within 1 week. Eggs were rinsed twice with ASW, kept at 16°C, and used on the day of collection.

High-speed aster centration imaging

Aster centration imaging was performed as described in 11. Briefly, eggs were first passed 3X through a 80-μm Nitex mesh, incubated 30 min with 10 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich) and subsequently let to sediment and stick on protamine-coated glass chambers. An activated sperm solution was prepared by diluting the sperm stock 1000X in ASW with subsequent vigorous ups and downs with a Pasteur pipette. One drop of this solution was added to the dish for fertilization. The center of sperm MT asters was tracked by visualizing the Hoechst-stained DNA of the male pro-nucleus.

Time-lapses were acquired on a spinning-disk confocal microscope (TI-Eclipse, Nikon) equipped with a Yokogawa CSU-X1FW spinning head, and an EM-CCD camera (Hamamatsu), using a 60x oil-immersion objective (Apo, NA 1.4, Nikon). The pixel size was 0.180 μm. The microscope was operated by MetaMorph (Molecular Devices), using a high speed image acquisition in ‘stream’ mode. The imaging area was reduced to obtain a frame rate of 20 Hz. After fertilization, an egg in which the sperm entered close to the equatorial plane was selected. Image acquisition was then started after the aster had moved 10-15 μm from the cell boundary, and monitored for 3-5 min at 20 Hz, corresponding to 3600-6000 time frames. Motion in Z was evaluated based on the focus quality of the Hoechst signal. Samples exhibiting large Z motion were excluded from the analysis. Imaged eggs proceeded to subsequent cell division and development.

Pharmacological inhibitors

Cytoskeletal inhibitors were applied by rapidly exchanging the medium in chambers. Drugs were applied after asters had migrated about 10 μm away from the cell boundary (typically ~ 5 min post fertilization). High-speed imaging was initiated 1-2 min after inhibitor application. Inhibitors were prepared in 100× stock aliquots in DMSO. Latrunculin B (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at a final concentration of 20 μM, Nocodazole (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 20 μM and Ciliobrevin D (EMD Millipore) at 100 μM.

High-resolution tracking

The sub-pixel localization of the center of the aster was obtained using standard analysis methods involving 2D Gaussian fits. An 80*80 pixels area was cropped around the aster center and used for successive analysis (Fig. S1, a and b). The intensity profile of the Hoechst signal was fitted with a 2D Gaussian function, and the aster center was defined as the mode of the best-fit Gaussian (Fig. S1, c and d). The spatial resolution was evaluated to be around ~20 nm, by performing those analyses in fixed samples (fig. S1, e and f). The effect of DNA signal deformation was mostly negligible when compared to the net displacement of asters (fig. S1e).

Fluctuation analyses

XY coordinates for the fluctuation analyses were defined by aligning the X axis with the longitudinal centering direction. Former studies showed that aster centration in this system is persistent with a large fraction of the centration motion associated with an average constant directionality and speed 11. Therefore, the XY coordinates were defined by assuming no systematic drift in the transverse Y axis, that is, a temporal integration of the Y position equal to zero. The outputs of the analyses did not depend on the particular choice of the coordinate origin, which was thus set to be the initial position of the aster center.

The aster trajectory can be decomposed into a deterministic component with constant velocity and a stochastic component , as:

| (eq. S1) |

To separate those two components, the residual displacement of the aster center, , was defined using a linear detrend of aster trajectory 22 (fig. S1g):

| (eq. S2) |

Putting eq. S1 into S2, yields

| (eq. S3) |

in which vanishes, indicating that may be regarded as the positional fluctuation accumulated during the lag time δt. The amplitude of for a fixed δt was mostly constant during the measurement period, suggesting that aster positional fluctuation can be considered as a steady-state problem (fig. S2).

The statistical properties of positional fluctuations were characterized by computing the Mean-Squared residual Displacements (MSrD) along the X and Y-axis ; MSrDx(δt) ≡ 〈δX2 (t; δt)〉t, MSrDy(δt) ≡ 〈δY2 (t; δt)〉t, where 〈 〉t denotes temporal average. The 1D diffusion coefficient along the X-axis, Dx, was determined by linear fitting of MSrDx (δt) for the period up to δt = 35 sec. Dy and the saturation timescale of fluctuations along the Y-axis, τ, were determined by fitting MSrDy(δt) for the period up to 60 sec using:

| (eq. S4) |

which describes a random walk of inertia-free particles under spring-like restoration forces 35. Equation S4 shows that the Y fluctuation is bound by 2τDy, which corresponds to the saturated Y fluctuation amplitude for longer time scale.

Magnetic tweezers set-up

The magnet tip used for force applications in vivo was built from three rod-shaped strong neodymium magnets (diameter 4 mm - height 10 mm, S-04-10-AN supermagnet) prolonged by a sharpened steel piece with a tip radius of ~50 μm to create a magnetic gradient.. The surface of the steel tip was electro-coated with gold to prevent oxidization.

The magnetic tweezers were mounted on an inverted epifluorescent microscope (TI-Eclipse, Nikon) combined with a CMOS camera (Hamamatsu). Eggs were filmed with a 20x dry objective (Apo, NA 0.75, Nikon) and a 1.5x magnifier, yielding a pixel size of 0.217 μm. The microscope was operated with Micro-Manager (Open Imaging). The magnetic tweezers were controlled using a micromanipulator (Injectman 4, Eppendorf).

Magnetic beads

To apply magnetic forces to intact sperm MT asters in eggs, several types of magnetic beads were tested. Large 2.8 μm diameter beads, allowed to apply large and localized forces, but did not strongly attach to asters (Fig S5). On the counterpart, small super-paramagnetic beads (NanoLink, solulink) (beads diameter 150-800 nm) had several advantages for the force experiments. First, it was possible to inject many beads without damaging the eggs. Second, injected beads were transported towards the aster center, most likely along astral MTs in a dynein and MT dependent manner (fig. S6 a) 26. This natural centripetal motion strongly facilitated the targeting process. The beads usually formed a single large aggregate stably attached to the aster center, which enabled to apply large forces to asters.

To prepare beads for injection, a solution of 10 μl of undiluted streptavidin-beads was first washed in 100 μL of washing solution (1 M NaCl with 1% Tween-20), and sonicated for 5 min. Beads were then washed 3X in water and re-suspended in 20 μL of Atto-488-biotin solution to render them fluorescent for 30 min at room temperature and kept on ice until use.

Unfertilized eggs were placed on protamine-coated glass bottom dish. The beads’ solution was injected using a micro-injection system (FemtoJet 4, Eppendorf) and a micro-manipulator (Injectman 4, Eppendorf). Injection pipettes were prepared from siliconized (Sigmacote) borosilicate glass capillaries (1 mm diameter). Glass capillaries were pulled using a needle puller (P-1000, Sutter Instrument) and grinded with a 30° angle on a diamond grinder (EG-40, Narishige) to obtain a 10 μm aperture. Injection pipettes were back-loaded with 2μl of bead solution before each experiment and were not re-used.

After injection, beads were accumulated on the egg side with the magnet, and subsequently released. Following fertilization, beads were naturally transported close to the male pro-nucleus at the center of the sperm aster where they formed a large aggregate. Beads targeting was oftentimes aided by approaching the magnet (movie S2).

The tight binding of the beads to the aster center was assessed by monitoring the distance between the beads aggregate and the Hoechst-stained sperm pro-nucleus at the aster center. This distance was mostly constant during force application (fig. S8), suggesting a tight binding between beads and asters. In the presence of 20 μM Nocodazole or 100 μM Ciliobrevin D, beads detached from the aster under external forces and rapidly moved in the cytoplasm. Beads also occasionally detached from the aster during force application (fig. S6c). The mobility of those detached beads was comparable to beads detaching in the presence of Nocodazole or Ciliobrevin D and significantly larger than that of the beads-aster complex (fig. S6d).

Immunostaining

Immunostaining was performed using similar procedures as described previously 11. Fixation to control for the effect of Ciliobrevin D was done in bulk, as described in fig S3. The fixation of eggs with injected beads, was performed in injection dishes after bead injection, fertilization and bead targeting to the aster center (fig S9 a). Fixations were done under the microscope to ensure that eggs did not move or change shape during liquid exchange. Eggs were first fixed for 70 min 100 mM Hepes, pH 6.9, 50 mM EGTA, 10 mM MgSO4, 2% formaldehyde,0.2% glutaraldehyde, 0.2% Triton X-100, and 400 mM glucose. Eggs were then rinsed three times for 10 min in PBS plus Tween 20 (PBT) and one time in PBS and placed in 0.1% NaBH4 in PBS made fresh for 30 min. Eggs were rinsed again with PBS and PBT and blocked in PBT plus 5% goat serum and 0.1% BSA for 30 min. For MT staining, cells were incubated for 48 h with a primary anti–α-tubulin antibody, clone DM 1A (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1/8,000, rinsed twice in PBS, and then incubated for 4 h with fluorophore-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1/750.

Magnetic force calibration

To calibrate magnetic forces, we first characterized the large-scale magnetic force field created by the magnet tip. To this aim, 2.8 μm mono-dispersed magnetic beads were placed in a viscous test fluid (80% glycerol, viscosity 8.0*10-2 Pa*sec at 22°C) and pulled by the same magnet used in vivo along its principle axis (fig. S8 a). The motion of the fluid during the force application was measured using non-magnetic tracer beads and found to be largely negligible. The speed of a bead, which is proportional to the magnetic force, was finally plotted as a function of the distance between the bead and the magnet tip (fig. S8 b).

Next, we characterized the drag coefficients of beads’ aggregates. To form aggregates in vitro, magnetic beads were first washed and labelled following the abovementioned protocol. 10 μL of beads were then mixed with 100 μL Poly-L-Lysine (1 mg/mL) and incubated for 3 min. This caused beads to form aggregates with sizes ranging from 2 to 8 μm typically, similar to what observed in cells (fig. S8 c). Those aggregates were tightly packed and largely homogenous, similar to the aggregates formed inside cells (fig. S7 a-h) We also confirmed that for both in vitro and in vivo situations, the aggregates did not largely change their size in the presence of magnetic fields (fig. S7, i and j). Those data suggest that aggregates prepared in vitro are close to those formed in the cell.

Aggregates prepared in vitro were placed in 50% glycerol (viscosity 7.7*10-3 Pa*sec at 22 °C) between a glass slide and a coverslip and let to sediment. The fall speed was measured by acquiring a Z-stack in time-lapse with a spinning-disk confocal microscope (Fig. S8 d). The Z interval used was 3 μm, and the time interval 5 sec. The signal intensity of the beads in each Z planes was plotted as a function of Z, and the position of the aggregate center was determined as the mode of a best-fit Gaussian for the intensity profile along the Z axis. (fig. S8 e). The fall speed of aggregations was determined by linear fit of Z position-time plot (fig. S8 f).

We found that the fall speed of aggregates was well approximated by that of a sphere with the same size (fig. S8 g). The fall speed of a perfect sphere with radius R follows the Stokes’ law so that:

| (eq. S5) |

where η is the viscosity of the test fluid, and ρbeads (ρsolution) is the density of beads (test fluid). The size of the aggregate Ra was defined using the longest length L1 and the length perpendicular to the longest axis, L2, as The fall speed of the aggregates was slightly but consistently smaller than that of a sphere with the same size, which is expected since the drag at low Reynolds number is governed by the largest dimension of an object 36. We evaluated this effect by fitting the results with where α is a fitting parameter. The best fit gave α = 0.66.

We then pulled the beads’ aggregates in 80% glycerol and measured the speed V (Fig. S8 h and i). The speed was translated into a force using Stokes’ law F = 6πηRaV, approximating aggregates as a sphere of radius Ra. Our direct measurement indicates that this approximation can lead to ~ 35% underestimation of the magnetic force. This analysis allowed to compute the magnetic force at a fixed distance (100 μm) as a function of aggregate size (fig. S8 i). The force-size relationship was well described by a cubic function, consistent with a magnetic dipole proportional to the aggregate volume. These force-size and force-distance relationships of beads’ aggregates were used to compute the magnetic forces applied to asters inside cells.

Magnetic force applications inside eggs

Unfertilized eggs were placed on protamine-coated glass bottom dish (P50G-0-14-F, MatTek), as described above. About 20 eggs were micro-injected with magnetic beads and fertilized under the microscope. An egg in which a sperm entered at the equatorial plane and close to the beads, was selected. The dish was then rotated to align the force direction and the principle axis of the magnetic tweezers. The center of the aster was tracked using the Hoechst-stained male pro-nucleus. Beads aggregates were tracked either in DIC or using fluorescence. Time-lapse movies were acquired with a time interval of 10 sec.

The force amplitude was controlled by adjusting the longitudinal position of the magnet tip. It took less than the time interval (10 sec) to modify the position of the magnet. The positions of the magnet tip and aster center were recorded in DIC and fluorescence, respectively. The distance between the aster and the beads was computed to control for the tight binding between the aster and the beads in each experiment.

Data analysis 1. Force applications along the centration axis

In experiments in which the forces were applied along the centering longitudinal direction of the aster, the force amplitude was varied 1-4 times in a step-like manner during each experiment. To minimize possible contributions from aster adaptive responses, we focused on short-time changes in aster speed. To that aim, we selected and analyzed typically 4 time points (30 sec) in each force step application during which the aster velocity and beads-aster distance were constant in time. The magnetic forces were computed using the beads-magnet tip distance at the mid-time point, which corresponds to an average force amplitude for the force application period. Aster velocity was defined using a linear fit of the aster trajectory. In front-pull experiments, asters sometimes overran the cell center when we applied the magnetic force for a long time (see fig. S10 Cell #11, for an example). These periods were excluded from the analysis. Importantly, aster frictional coefficient and stall force values were not grossly affected when considering only the first force step application, or all subsequent steps; ruling out dramatic aster reorganization after force applications. Finally, those parameters were also mostly robust to the range of aggregates sizes used (fig S12).

Data analysis 2. Force applications orthogonal to the centration axis

In experiments in which forces were applied along the axis transverse to centration, the asters were pulled until their Y position reached saturation, which took typically 1-2 min. In the force-displacement analyses, the magnetic forces were computed using the distance between the magnet tip and beads aggregates at the end of the force application where aster Y position reached saturation. The centration axis was defined in a semi-automated manner, using the trajectory before force application.

The recovery dynamics of the transverse Y position after force cessation was fitted using:

| (eq. S6) |

where t=0 corresponds to the time of force cessation. The recovery time-scale τr did not depend on the Y saturation (Fig. 3d, inset), suggesting that the aster response is in a linear regime.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge M. Coppey and J. Azimzadeh for technical support, and S. Dmitrieff, T. Strick, M. Piel, M. Thery and K. Laband for careful reading of the manuscript. This research was supported by the CNRS and grants from the “Mairie de Paris emergence” program, the FRM “amorçage” grant AJE20130426890 and the European Research Council (CoG Forcaster N° 647073).

Footnotes

Additional information:

The experimental protocol was approved by Isabelle Le Parco, head of the animal facility at Institut Jacques Monod.

Data Availability Statement:

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Author contributions:

H.T., L.D., J.S., and N.M. performed experiments. H.T. analyzed the data and developed the model. H.T. and N.M. designed the research and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bornens M. The centrosome in cells and organisms. Science. 2012;335:422–426. doi: 10.1126/science.1209037. 335/6067/422 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang N, Marshall WF. Centrosome positioning in vertebrate development. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:4951–4961. doi: 10.1242/jcs.038083. 125/21/4951 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchison T, et al. Growth, interaction, and positioning of microtubule asters in extremely large vertebrate embryo cells. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2012 doi: 10.1002/cm.21050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holy TE, Dogterom M, Yurke B, Leibler S. Assembly and positioning of microtubule asters in microfabricated chambers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:6228–6231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faivre-Moskalenko C, Dogterom M. Dynamics of microtubule asters in microfabricated chambers: the role of catastrophes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16788–16793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252407099. 252407099 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laan L, et al. Cortical Dynein Controls Microtubule Dynamics to Generate Pulling Forces that Position Microtubule Asters. Cell. 2012;148:502–514. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert S. Developmental Biology. 9th edition. Sinauer Associates; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamaguchi MS, Hiramoto Y. Analysis of the Role of Astral Rays in Pronuclear Migration in Sand Dollar Eggs by the Colcemid - UV Method. Development, growth & differentiation. 1986;28:143–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1986.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura A, Onami S. Computer simulations and image processing reveal length-dependent pulling force as the primary mechanism for C. elegans male pronuclear migration. Dev Cell. 2005;8:765–775. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.007. S1534-5807(05)00095-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longoria RA, Shubeita GT. Cargo transport by cytoplasmic dynein can center embryonic centrosomes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanimoto H, Kimura A, Minc N. Shape-motion relationships of centering microtubule asters. J Cell Biol. 2016;212:777–787. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201510064. jcb.201510064 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wuhr M, Tan ES, Parker SK, Detrich HW, 3rd, Mitchison TJ. A model for cleavage plane determination in early amphibian and fish embryos. Curr Biol. 2010;20:2040–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.024. S0960-9822(10)01288-1 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura K, Kimura A. Intracellular organelles mediate cytoplasmic pulling force for centrosome centration in the Caenorhabditis elegans early embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:137–142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013275108. 1013275108 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terasaki M, Jaffe LA. Organization of the sea urchin egg endoplasmic reticulum and its reorganization at fertilization. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:929–940. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.5.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minc N, Burgess D, Chang F. Influence of cell geometry on division-plane positioning. Cell. 2011;144:414–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.016. S0092-8674(11)00017-1 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierre A, Salle J, Wuhr M, Minc N. Generic Theoretical Models to Predict Division Patterns of Cleaving Embryos. Dev Cell. 2016;39:667–682. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.11.018. S1534-5807(16)30830-9 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haupt A, Minc N. How cells sense their own shape - mechanisms to probe cell geometry and their implications in cellular organization and function. J Cell Sci. 2018;131 doi: 10.1242/jcs.214015. jcs214015 [pii], 131/6/jcs214015 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wuhr M, Dumont S, Groen AC, Needleman DJ, Mitchison TJ. How does a millimeter-sized cell find its center? Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1115–1121. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.8.8150. doi:8150 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu J, Burakov A, Rodionov V, Mogilner A. Finding the cell center by a balance of dynein and myosin pulling and microtubule pushing: a computational study. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:4418–4427. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-07-0627. E10-07-0627 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fulton AB. How crowded is the cytoplasm? Cell. 1982;30:345–347. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90231-8. doi:0092-8674(82)90231-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brangwynne CP, Koenderink GH, MacKintosh FC, Weitz DA. Cytoplasmic diffusion: molecular motors mix it up. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:583–587. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806149. jcb.200806149 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winkler F, et al. Fluctuation Analysis of Centrosomes Reveals a Cortical Function of Kinesin-1. Biophys J. 2015;109:856–868. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.07.044. S0006-3495(15)00779-1 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pecreaux J, et al. The Mitotic Spindle in the One-Cell C. elegans Embryo Is Positioned with High Precision and Stability. Biophys J. 2016;111:1773–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.09.007. doi:S0006-3495(16)30800-1 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almonacid M, et al. Active diffusion positions the nucleus in mouse oocytes. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:470–479. doi: 10.1038/ncb3131. ncb3131 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garzon-Coral C, Fantana HA, Howard J. A force-generating machinery maintains the spindle at the cell center during mitosis. Science. 2016;352:1124–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9745. 352/6289/1124 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamaguchi MS, Hamaguchi Y, Hiramoto Y. Microinjected polystyrene beads move along astral rays in sand dollar eggs. Development, growth & differentiation. 1986;28:461–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1986.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinar T, Mana M, Piano F, Shelley MJ. A model of cytoplasmically driven microtubule-based motion in the single-celled Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10508–10513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017369108. 1017369108 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbosa DJ, et al. Dynactin binding to tyrosinated microtubules promotes centrosome centration in C. elegans by enhancing dynein-mediated organelle transport. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006941. PGENETICS-D-17-00891 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grill SW, Howard J, Schaffer E, Stelzer EH, Hyman AA. The distribution of active force generators controls mitotic spindle position. Science. 2003;301:518–521. doi: 10.1126/science.1086560. 301/5632/518 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Simone A, Spahr A, Busso C, Gonczy P. Uncovering the balance of forces driving microtubule aster migration in C. elegans zygotes. Nat Commun. 2018;9:938. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03118-x. 10.1038/s41467-018-03118-x [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hiramoto Y. Mechanical properties of the protoplasm of the sea urchin egg. II. Fertilized egg. Exp Cell Res. 1969;56:209–218. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(69)90004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nazockdast E, Rahimian A, Needleman D, Shelley M. Cytoplasmic flows as signatures for the mechanics of mitotic positioning. Mol Biol Cell. 2017;28:3261–3270. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-02-0108. mbc.E16-02-0108 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nazockdast E, Rahimian A, Zorin D, Shelley M. A fast platform for simulating semi-flexible fiber suspensions applied to cell mechanics. J Comput Phys. 2017;329:173–209. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Svoboda K, Mitra PP, Block SM. Fluctuation analysis of motor protein movement and single enzyme kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11782–11786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doi M, Edwards SF. The theory of polymer dynamics. Vol. 73 oxford university press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Happel J, Brenner H. Low Reynolds number hydrodynamics: with special applications to particulate media. Vol. 1 Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.