Abstract

Purpose: Various tools have been utilized for cultural competency training in residency programs, including cultural standardized patient examinations. However, it is unknown whether residents feel the training they received has a long-term impact on how they care for patients. The purpose of this study was to assess whether surgical residents who participated in a cultural standardized patient examination view the experience as beneficial.

Methods: Surgical residents who completed a standardized patient examination from Fall 2009 to Spring 2015 were asked to complete a 13-question survey assessing the following: (1) did participants feel prepared when dealing with patients from different cultural backgrounds, (2) did they feel the standardized patient experience was beneficial or improved their ability to care for patients, and (3) did they perceive that cultural competence was important when dealing with patients.

Results: Sixty current/former residents were asked to participate and 24 (40%) completed the survey. All agreed cross-cultural skills were important and almost all reported daily interaction with patients from different cultural backgrounds. Sixteen participants (67%) reported the cultural standardized patient examination aided their ability to care for culturally dissimilar patients, and 13 (54%) said the training helped improve their communication skills with patients. Thirteen (54%) reported they would participate in another cultural standardized patient examination.

Conclusion: Development of effective cultural competency training remains challenging. This study provides some preliminary results that demonstrate the potential lasting impact of cultural competency training. Participants found the skills gained from cultural standardized patient examinations helpful.

Keywords: : cultural competence, general surgery residency training, cultural standardized patient examination

Introduction

Cultural competency is the ability to communicate effectively and provide consistently excellent care to patients from diverse backgrounds. The importance of cultural competency in surgery has been noted.1–6 For example, cultural competency is critical for the development of physician-patient rapport to increase patient adherence and satisfaction.2 These skills fall under three categories of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competencies: patient care, professionalism, and interpersonal and communication skills. Despite this recognition, formal cultural competency training programs in surgery are still lacking. Shah et al. conducted a survey of ACGME-accredited general surgery residency programs in the United States and interviewed those who reported formal curricula in cultural competency.7 Currently, only three programs have ongoing initiatives that have lasted for 7 years or more, with a new initiative at Brigham and Women's Hospital's Center for Surgery and Public Health that includes a patient satisfaction/outcome component.8

There is debate over the best method to teach and cultivate these skills. While it has been traditionally believed that one could gain cultural competency by observing senior physicians, studies have shown that passive learning is not enough to significantly improve one's skill in cultural competency,9,10 calling an end to the “see one, do one, teach one” era.11 Multiple institutions have focused on developing a standardized form of training and assessment through the use of Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) or cultural standardized patient examinations,4–6,9,12 and studies have demonstrated the immediate benefits of using a standardized patient examination to train surgical residents.3–5,9,13 The use of formal didactic sessions along with standardized patient examinations has shown positive changes in patient care delivery and formation of better relationships with physicians.13

Many studies agree that standardized patient examinations are practical and valuable tools to train and assess cultural competency,2,9,12 but training can be costly and time-consuming to proctor. The assessment of long-term effects becomes important in supporting the necessity of standardized patient examinations in resident training. Hochberg et al. looked into the sustained effect of integration of professionalism into residency education at the New York University Medical Center.13 A post-study 3 years after the implementation of the professionalism curriculum showed that formal training did translate to retained skills over time.

In consultation with faculty from the UHM Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Chun et al. developed a cultural standardized patient examination focused on a surgeon attempting to obtain informed consent from an elderly Samoan male who must have a below-the-knee amputation or face certain death. In addition to him, two additional standardized patients were also present (i.e., the patient's spouse and a medical interpreter). Samoan medical interpreters from a local community health clinic provided feedback on the case to enhance authenticity.5

Taking place in the late Summer, the examination utilizes two measures to assess resident performance. The first measure, an abridged version of Weissman and Betancourt's Cross-Cultural Care Survey (which assesses resident's perceived preparedness to provide cross-cultural care), was administered right before the resident participated in the cultural standardized patient examination.14,15

The second measure, an ACGME competency-based written checklist developed by the UHM Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, allowed the faculty and standardized patients to provide immediate feedback to the resident. In addition, the resident completed a self-assessment/self-reflection. The sessions were also videorecorded so that the residents could review their performance. During the Fall, a lecture/didactic session/journal club on a relevant cultural competency topic was presented during Grand Rounds. During the late Winter/early Spring, a post-test, utilizing the same protocol as the pre-test, was conducted.4,5

Designed in 2008, the initial evaluation of the project was published in 2012,4 with a follow-up study in 2014, which did not demonstrate statistically significant differences in skillfulness or knowledge, but there was a statistically significant change from the pre-test to post-test in the overall rating scale.5 Our study hopes to gain a better understanding of the residents' long-term perception of the effectiveness of the cultural standardized patient examination experience, as well as evaluate the participants' confidence in handling encounters that require cultural competency. The survey results may also serve as an important tool to encourage critical thinking and self-reflection on the current training program, educational methods, and areas in need of improvement.

Materials and Methods

The University of Hawaii at Manoa Department of Surgery (UHM Dept of Surgery) initiated a cultural standardized patient examination in 2008. A survey was created to assess whether participation in the examination had any long-term effect on the participants' perceptions about cultural competency and their abilities to provide cross-cultural care to patients. All surgical residents who completed the standardized patient examinations from Fall 2009 to Spring 2015 were asked to participate in the study. Participation was strictly voluntary. A total of 60 subjects were eligible, with 24 completing the survey.

Participants were given the option to complete (1) an online survey, (2) hardcopy survey, (3) phone interview, (4) in-person interview, or (5) in-person focus group interview. Eligible participants were contacted through the UHM Dept of Surgery's residency program. The first e-mail was sent out on August 27, 2015, and participants were asked to complete an online survey. A reminder e-mail was sent out on September 11, 2015. Due to a low response rate (three participants, 5%), the phone interview, in-person interview, and/or in-person focus group interview options were added. To improve participation, $10 Starbucks gift cards were offered for completion. The study was announced at Grand Rounds on October 14, 2015. No participants used the phone interview, in-person interview, or focus group interview options; so we determined that a hardcopy survey distributed during Grand Rounds would likely result in higher participation. The hardcopy survey was distributed during a Town Hall meeting with the current residents on November 11, 2015. A final reminder e-mail was sent on November 24, 2015.

Survey items were developed from a review of the literature and categorized by the following topic areas: (1) did participants feel prepared when dealing with patients from different cultural backgrounds, (2) did they feel the standardized patient experience was beneficial/did they feel any improvement in their ability to care for patients, and (3) did they feel cultural competence was important when dealing with patients. The survey included 13 open-ended questions, listed in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

Survey questions provided to participants.

Due to survey responses being open ended, some recoding was necessary for analysis. Specifically, responses to questions 5, 7, 8, and 9 were recoded into categories of “Definitely Yes,” “To Some Extent,” “To Minimal Extent,” and “Definitely No.” Almost all responses to question 6 were recoded into a common metric of “Daily,” with the exception of one response of “Multiple Times Per Week.” Responses to questions 11 and 12 were recoded into dichotomous “Yes” and “No” responses. A content analysis was conducted on the qualitative feedback from questions 10 and 13, and the frequencies of common themes were tabulated. Data were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics 23 Descriptive Statistics.

We obtained Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Hawaii Human Studies Program (CHS no. 23322). The study was deemed as exempt.

Results

Of the 24 participants, 17 (71%) were current residents and 7 (29%) were former residents. Their reported specialties included surgery (75%), anesthesiology (13%), general practice and informatics (4%), and radiology (4%), while this information was missing for one participant (4%). All, but one participant (96%) reported interacting with patients from cultural backgrounds different from their own as frequently as daily, and one participant reported “multiple times per week.”

In response to the item inquiring whether they felt prepared when caring for patients from cultural backgrounds different from their own, 16 participants (67%) replied Definitely Yes, 7 (29%) replied To Some Extent, and 1 (4%) replied To Minimal Extent (Fig. 2). With regard to whether the cross-cultural training helped improve their communication skills with their patients, 10 participants (42%) said Definitely Yes, 3 (13%) said To Some Extent, 3 (13%) said To Minimal Extent (13%), and 8 (33%) said Definitely No.

FIG. 2.

Preparedness when caring for patients from different cultural backgrounds.

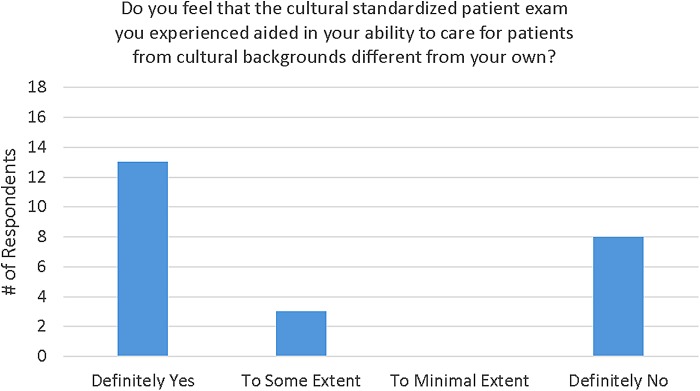

Thirteen participants (54%) felt that the cultural standardized patient examination definitely aided in their ability to care for culturally dissimilar patients, while three participants (13%) felt it helped To Some Extent, and eight (33%) said it did not help (Fig. 3). Of those who felt it was helpful, the most commonly reported specific aspects of the training they felt were most helpful were the feedback they received from the standardized patient or with the surgery attending (4 [27%] of those who reported specific aspects), learning how to communicate (also 4 [27%] of those who reported specific aspects), and the practice it provided in general or specifically with the interpreter (3 [20%] of those who reported specific aspects). Other specific aspects perceived as most helpful (one response each) included learning about a specific culture, the cultural barriers and religious influences, reflecting on the activity, gaining “awareness,” and the overall mock patient experience.

FIG. 3.

Helpfulness of standardized patient examination training.

All participants (100%) felt that cross-cultural skills are important when interacting with their patients and 13 (54%) would participate in another cultural standardized patient training experience.

Discussion

Cultural competency is widely acknowledged as an important skill when dealing with patients, but creating effective training for future physicians to obtain cross-cultural healthcare skills remains challenging. Simply gaining exposure by learning and working within multicultural societies or participating in immersion programs is not enough to significantly improve one's cultural competency.10

Previous studies by Chun et al. have shown that participation in a cultural standardized patient examination led to an improvement in the overall ratings scale in a post-test taken 6 months later.5 Our follow-up study showed that participants have maintained positive attitudes toward cultural competency standardized examinations even years after completion. All participants reported feeling at least somewhat prepared when dealing with patients from different cultural backgrounds. A majority reported that training helped improve their communication skills and aided in their ability to care for patients from different cultural backgrounds. This suggests that the residents felt the skills and knowledge they gained from the standardized patient examinations during residency were for the most part retained and helped shape their practice as physicians.

Although our study assessed only the residents' attitude after training completion, the finding of positive attitudes was consistent with other studies that quantitatively assessed the long-term effectiveness of cultural competency training. Ho et al. reported that improvements in cross-cultural communication skills could be sustained a year later.16 Students participated in two interactive cultural competence workshops and were later evaluated using OSCEs with standardized patients. Cross-cultural communication skills were assessed immediately after completion of the workshops and again 1 year later. Although the effectiveness of training diminished slightly with time, the group with training had higher competency scores than the control group without training. Improvement in cultural competency helps to explain why our residents had an overall positive feeling and attitude toward cultural competency after the completion of their training.

Not surprisingly, all participants agreed cross-cultural skills are important when interacting with their patients. However, while most of the participants (54%) would participate in another training, almost half (46%) would not. In fact, one-third did not find the standardized patient training helpful. These findings should be investigated further. One explanation may be that the participants perceive themselves as culturally competent when interacting with patients, believing they already have the necessary cross-cultural healthcare skills and have no need to attend more training. This brings up the issue of unconscious bias, the idea that physicians' actions may be influenced by cultural stereotypes or prejudices they are not aware of.17 Physicians are unaware these biases may influence how they approach and communicate with a patient, leading to unintended discrimination against and compromised care for patients from different cultural backgrounds.17–19 This is important to consider when using self-reported answers to evaluate cultural competency.

Although the cultural standardized patient examination training has room for improvement, our results show residents considered it a useful tool. Cross-cultural healthcare skills can be retained and applied to real-life interactions with patients even years after the training occurred. Participants particularly found the feedback sessions and experience communicating with the patients to be beneficial. While open-ended surveys have their share of limitations, they do allow for honest and unrestricted feedback. These results can help to improve the development of future cultural competency training using standardized patient examinations.

Along with the small sample size, limitations included the lack of a control or comparison group. To maintain anonymity, results from survey responses were not compared with an objective post-test. Most participants were current residents in the UHM Dept of Surgery, predisposing us to selection bias as the data would not be entirely applicable and representable to residents elsewhere. Residents practicing in Hawaii are exposed to daily encounters of cultural diversity at work and may answer more positively in regard to the importance of cultural competency. Residents practicing in less diverse regions may not be exposed to scenarios that require cultural sensitivity and competency on a daily basis. Hence, they may not feel the cultural competency training was as useful. Although the population could not have been separated in this study due to the blinding process, this potential geographical bias would be an interesting point to pursue for any future study. Follow-up surveys may include questions pertaining to the location of their current practice and specific examples on how they apply their cultural competency skills in interactions with patients. We understood the limitations of open-ended survey as we designed our method. However, our decision to choose this form of study has been heavily dependent on our wish to preserve the freedom of providing feedback without the constraints of forced response scales.

Conclusion

Cultural competency training continues to be a mandatory part of both undergraduate and graduate medical curricula. However, doubts remain as to its long-term impact on trainees. More studies need to take the time to assess the effect cultural competency training has not only those who participate in the training but also those who provide the training, and most importantly, those who are “recipients” of the training—the patients. This is one critical component of ensuring equitable healthcare for all. Therefore, we recommend the following for those attempting to assess the efficacy of their cultural competency training:

1. Incorporate a long-term evaluation component during the project design phase, not during the course of the study or after the fact. Ensure that tools used have been validated and they adequately measure whether the intervention was effective or not. Attempt to utilize existing protocols and tailor them to your program rather than starting with a blank slate;

2. Include all stakeholders in the development of the evaluation component, including patients, to determine how to best obtain their feedback, while not violating any HIPAA or other privacy rules; and

3. Pilot the evaluation tools to test for validity and reliability. Attempt to establish a long-term commitment from study participants so that periodic follow-ups can be conducted to determine if the training has been retained.

Abbreviations Used

- ACGME

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

- OSCEs

Objective Structured Clinical Examinations

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ly CL, Chun MB. Welcome to cultural competency: surgery's efforts to acknowledge diversity in residency training. J Surg Educ. 2013;70:284–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins LG, Schrimmer A, Diamond J, et al. Evaluating verbal and non-verbal communication skills, in an ethnogeriatric OSCE. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:158–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis D, Lee G. The use of standardized patients in the plastic surgery residency curriculum: teaching core competencies with objective structured clinical examinations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:291–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chun MB, Young KG, Honda AF, et al. The development of a cultural standardized patient examination for a general surgery residency program. J Surg Educ. 2012;69:650–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chun MB, Deptula P, Morihara S, et al. The refinement of a cultural standardized patient examination for a general surgery residency program. J Surg Educ. 2014;71:398–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun MB, Yamada AM, Huh J, et al. Using the cross-cultural care survey to assess cultural competency in graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2:96–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah SS, Sapigao FB, Chun MBJ. An overview of cultural competency curricula in ACGME-accredited general surgery residency programs. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Experts and Patients Develop Cultural Dexterity Curriculum for Surgeons. https://bwhclinicalandresearchnews.org/2016/01/07/experts-and-patients-develop-cultural-dexterity-curriculum-for-surgeons Accessed July26, 2017

- 9.Wehbe-Janek H, Song J, Shabahang M. An evaluation of the usefulness of the standardized patient methodology in the assessment of surgery residents' communication skills. J Surg Educ. 2011;68:172–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton J. Intercultural competence in medical education—essential to acquire, difficult to assess. Med Teach. 2009;31:862–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenchus JD. End of the “see one, do one, teach one” era: the next generation of invasive bedside procedural instruction. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2010;110:340–346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balzora S, Abiri B, Wang XJ, et al. Assessing cultural competency skills in gastroenterology fellowship training. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1887–1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hochberg MS, Berman RS, Kalet AL, et al. The professionalism curriculum as a cultural change agent in surgical residency education. Am J Surg. 2012;203:14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weissman JS, Betancourt J, Campbell EG, et al. Resident physicians' preparedness to provide cross-cultural care. JAMA. 2005;294:1058–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chun MB, Huh J, Hew C, et al. An evaluation tool to measure cultural competency in graduate medical education. Hawaii Med J. 2009;68:116–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho MJ, Yao G, Lee KL, et al. Long-term effectiveness of patient-centered training in cultural competence: what is retained? What is lost? Acad Med. 2010;85:660–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santry HP, Wren SM. The role of unconscious bias in surgical safety and outcomes. Surg Clin North Am. 2012;92:137–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellack JP. Unconscious bias: an obstacle to cultural competence. J Nurs Educ. 2015;54:S63–S64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haider AH, Schneider EB, Sriram N, et al. Unconscious race and social class bias among acute care surgical clinicians and clinical treatment decisions. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:457–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

Cite this article as: Yeung F, Yuan C, Jackson DS, Chun MBJ (2017) Gone, but not forgotten? Survey of resident attitudes toward a cultural standardized patient examination for a general surgery residency program, Health Equity 1:1, 150-155, DOI: 10.1089/heq.2017.0016.