Nor-β-lapachone-loaded (NβL-loaded) microcapsules were characterized. The NβL-loaded PLGA microcapsules exhibited a pronounced initial burst release. The cytotoxic activity against a set of cancer cell lines was investigated.

Nor-β-lapachone-loaded (NβL-loaded) microcapsules were characterized. The NβL-loaded PLGA microcapsules exhibited a pronounced initial burst release. The cytotoxic activity against a set of cancer cell lines was investigated.

Abstract

In this work, we characterize nor-β-lapachone-loaded (NβL-loaded) microcapsules prepared using an emulsification/solvent extraction technique. Features such as surface morphology, particle size distribution, zeta potential, optical absorption, Raman and Fourier transform infrared spectra, thermal analysis data, drug encapsulation efficiency, drug release kinetics and in vitro cytotoxicity were studied. Spherical microcapsules with a size of 1.03 ± 0.46 μm were produced with an encapsulation efficiency of approximately 19%. Quantum DFT calculations were also performed to estimate typical interaction energies between a single nor-β-lapachone molecule and the surface of the microparticles. The NβL-loaded PLGA microcapsules exhibited a pronounced initial burst release. After the in vitro treatment with NβL-loaded microcapsules, a clear phagocytosis of the spheres was observed in a few minutes. The cytotoxic activity against a set of cancer cell lines was investigated.

1. Introduction

Cancer is a proliferative disease characterized by atypical growth of uncontrolled cells that invade other tissues. Cancerous cells, also called malignant cells, move to the blood circulation and spread to lymph nodes (metastasis), eventually developing new tumours in different organs.1 These aberrant proliferations can be clinically detectable as neoplasia, which literally means new growth.2 Many studies have attested that these mutations can allow the functional activation of some genes (oncogenes) or the inactivation of tumour suppressor genes.1,3 Oncogenes contribute to the stimulation of proliferation or the deactivation of senescence and/or apoptosis, whereas tumour suppressor genes generally act as checkpoints to proliferation or cell death.1,4 Epigenetic factors connect external (toxic compounds, drugs or diet) and internal factors (cytokines or growth factors) involved in cancer development.5

Numerous plant-derived compounds were reported to possess robust anticancer activity.6 Among the most promising drugs, quinones constitute a diversified class of compounds, which are widely distributed in nature, classified by the aromatic moieties existent in their structure and associated with diverse biological activities.7 The National Cancer Institute (NCI) identified the quinone moiety as an important pharmacophoric group owing to its cytotoxic activity in screening of natural products.8

As reported so far, the cytotoxicity of quinones can be related to a number of mechanisms, in particular redox cycling, which produces reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the alkylation of cellular nucleophiles, prompting covalent binding with proteins and/or DNA9 and producing irreversible cellular changes and death.10

Quinoidal compounds are the second largest class of anticancer drugs used clinically for cancer chemotherapy.9b,11 Related to this class, lapachol (extracted from the heartwood of Tabebuia sp.) and its derivatives α-lapachone and β-lapachone are among the most important naphthoquinones studied due to their biological activities.12 β-Lapachone is one of the most widely studied naphthoquinones currently in phase II clinical trials.13 β-Lapachone was shown to be a selective inducer of cell death in cancer cells,14 acting against a wide variety of multidrug resistant cancer cell lines.15 Furthermore, β-lapachone increased the lethality against human cancer cells in association with other drugs (taxol, mitomycin C and paclitaxel) and acted as a co-adjuvant in killing human cancer cells during radiotherapy treatment.14 Specifically, this compound is bioactivated by NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1). NQO1 induces futile cycling of the drug that exhausts NAD(P)H in the cell, leading to a considerable quantity of ROS that causes DNA damage.16 Unfortunately, the low solubility and non-specific distribution of β-lapachone have limited its suitability for clinical assays.17 To overcome these problems, several delivery release strategies were proposed: β-lapachone complexed with hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin16 or methylated-β-cyclodextrin18 and β-lapachone-containing poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(d,l-lactide) polymer micelles.16 Gold nanoparticles with surface modifications with polyethylene glycol loaded with β-lapachone in per-6-thio-β-cyclodextrin pockets and complexed with an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody as a targeting ligand were already demonstrated.19 More recently, β-lapachone in liposomes20 and a β-lapachone-poloxamer-cyclodextrin ternary system17 were also put to the test.

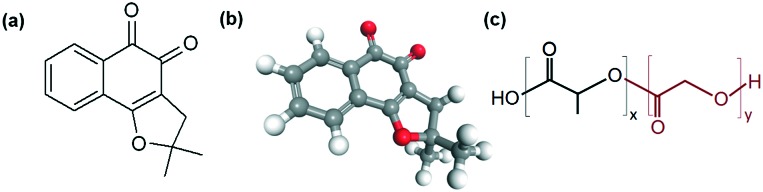

Our research group has dedicated effort to the synthesis and antitumor studies of lapachone derivatives.21 Recognized as an important prototype with anti-cancer activity, nor-β-lapachone (NβL) (Fig. 1) was studied by us against several cancer cell lines, exhibiting IC50 values in the range of 0.3–2.5 μM.10,22 Interestingly, this drug showed low cytotoxic activity in non-tumor cells and genotoxic and mutagenic effects only at high concentrations.23,24 Compared with β-lapachone, nor-β-lapachone also has great advantages in synthetic terms. NβL is prepared from nor-lapachol in a quantitative yield. Nor-lapachol is easily prepared from a commercial quinone, lawsone.21

Fig. 1. Representation of the nor-β-lapachone (NβL) and PLGA molecules: (a) planar chemical structure of NβL; (b) 3D chemical structure of NβL; (c) planar chemical structure of poly(d,l)-lactide-co-glycolide (PLGA); x (lactic acid) and y (glycolic acid) indicate the number of repetitions of each unit.

Strategies for cancer treatment based on controlled delivery systems are the focus of many investigations to overcome liposolubility and/or low bioavailability problems, as well as the instability of the drug in physiological fluids and off-target toxicity of anticancer drugs, optimizing therapeutic efficacy and reducing toxic side effects.25 Gradual release of the drug with constant plasma levels simplifies its uptake by cancer cells, improving the drug availability at the desired target and consequently increasing its efficacy.25a Besides, it decreases the drug resistance developed by tumour cells.26

Numerous chemotherapeutic agents have been microencapsulated in a poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) polymer (Fig. 1).26a,27 PLGA is a biodegradable and biocompatible polymer approved by the US FDA for human use28 and applied in pharmaceutical and medical devices which allows the gradual release of entrapped drugs over a long duration.25a PLGA-based drug delivery systems undergo two main release mechanisms, namely, diffusion and degradation/erosion,29 and may present an adjustable degradation rate based on the amount of the d,l-lactide/glycolide polymers.28 All these properties have turned PLGA into an attractive option for the development of controlled release delivery devices.

For the reasons discussed above, recently we have shown the efficiency of NβL in PLGA microparticles for improving its cytotoxicity against prostate cancer cells.30 In this previous report, we have discussed our first impressions related to this efficient strategy to make this lapachone derivative more potent against cancer cells.

In this work, we present a complete study on a PLGA-microencapsulated formulation containing nor-β-lapachone. We evaluated some modifications to increase the drug load. The interaction of NβL and PLGA after encapsulation was then studied by absorbance measurements, luminescence spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). The drug loading, encapsulation efficiency, and in vitro drug release kinetics were measured by spectroscopic analysis, while scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to assess the surface morphology and size distribution of the microparticles. Surface charges were evaluated by zeta potential measurements, and classical molecular dynamics, annealing, and adsorption techniques were combined with quantum density functional theory (DFT) calculations to estimate the typical binding energy values of the drug on the PLGA microparticle surface. The in vitro cytotoxic effect of the NβL-loaded microcapsules was investigated by examining their viability on different cancer cell lines in comparison with empty PLGA microcapsules and the free drug. The in vitro cellular internalization of NβL-loaded microcapsules was visualized by using optical microscopy.

2. Results and discussion

Nano/microparticles are important carriers for drug delivery. Microparticles have diameters between 1 and 250 μm and are prepared through conventional emulsion solvent evaporation techniques or spray drying,28 which are easy to implement. Microencapsulation methods can form microspheres (monolithic matrix) or microcapsules (hollow capsules),31 in general exhibiting a spherical morphology with monodisperse32 or polydisperse particle size distributions.31a Microparticles, in comparison with nanoparticles, have the advantage of carrying higher drug amounts and exhibit better control over sustained release profiles.32

Initially, we have focused our efforts on the preparation and characterization of PLGA microparticles involving NβL. Based on the physicochemical properties of NβL, PLGA microparticle formulations were prepared by the emulsion solvent evaporation method, either with a simple (o/w) or a double (w/o/w) emulsion system. The w/o/w method was not effective for this drug, the simple emulsion method being the most satisfactory for the preparation of NβL microparticles. Evaluation of the role of formulation parameters such as the drug/polymer ratio and PVA solution volume in the microparticles was carried out. Table S1 (ESI†) gives the details of 10 formulations prepared using an o/w emulsion and 9 formulations prepared using a w/o/w emulsion. Formulation 7 showed the best results in terms of morphology and encapsulation rate and was selected for all subsequent studies. The percentage yield of each adequate encapsulation was determined and was greater than 70% for all formulations.

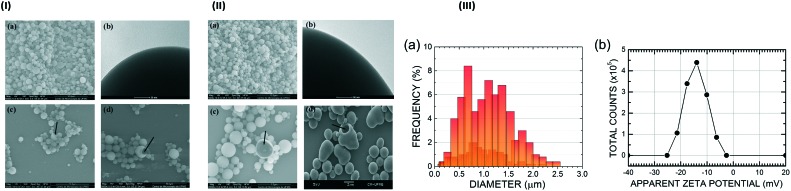

Following our strategy, the microparticle morphology, size distribution and zeta potential were also studied. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were employed for the morphological characterization of the PLGA microparticles with (Fig. 2, IIa–d) and without NβL (Fig. 2, Ia–d). The PLGA microparticles containing NβL showed a regular spherical shape, a heterogeneous size and the absence of agglomeration (Fig. 2, IIa), looking not very different from the case of pure PLGA microparticles (Fig. 2, Ia). Their surfaces were smooth and nonporous, and no drug crystal formation was observed (Fig. 2, IIb). The electron microscopy studies also confirmed that the formulated microparticles had a hollow structure (microcapsules) (Fig. 2, IIc), as in the samples of pure PLGA microparticles (Fig. 2, Ic). Following incubation in distilled water at 37 °C for 24 h, we observed changes in morphology and polymer degradation after just one day, as shown in Fig. 2(Id), while for pure PLGA the same level of degradation was observed after five days of degradation in water at the average core human body temperature of 37 °C. PLGA microparticles containing NβL exhibit a bimodal size distribution with maxima at 0.68 μm and 1.23 μm, an average diameter of 1.03 ± 0.46 μm (Fig. 2, IIIa), a minimum observed diameter of 0.15 μm (0.2% frequency) and a maximum observed diameter of 2.47 μm (0.4% frequency). The most common PLGA microparticle diameter found was about 0.68 μm, with 8% frequency, followed by 1.1 μm with 7.2%, 1.37 μm with 6.8% and 1.23 μm with 6%. The surface electrical properties of the microcapsules revealed that empty PLGA microparticles had a zeta potential of –23.4 ± 0.35 mV, while PLGA microparticles containing NβL exhibited a less negative value (–14.0 ± 0.17 mV) (Fig. 2, IIIb), corresponding to 4.4 × 105 counts at –14.0 mV, 3.4 × 105 counts at –17.6 mV and 2.9 × 105 counts at –10.0 mV (the number of counts falls to practically zero below –25.2 mV and above –2.50 mV). Thus, PLGA microparticles loaded with NβL tend to be less stable against coagulation than colloidal dispersions of pure PLGA microparticles.

Fig. 2. (I) Microphotographs illustrating the regular spherical form, different sizes and surface features of empty PLGA microparticles obtained by the simple emulsion (o/w) process. (a) Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) at a magnification of ×5000; (b) transmission electron microscopy image showing a microparticle surface at a magnification of ×300; (c) SEM showing cryofractured microcapsules (black arrow); (d) SEM showing the irregular form and erosion of PLGA microparticles (black arrow) after 5 days of degradation in water at 37 °C. (II) Microphotographs illustrating the shapes, different size ranges and the surface structure of PLGA microparticles containing NβL obtained by the simple emulsion (o/w) process. (a) Scanning electron micrographs (SEM) at a magnification of ×5000; (b) Transmission electron microscopy image showing a microparticle surface at a magnification of ×300; (c) SEM showing cryofractured microparticles (black arrow); (d) SEM showing the irregular form and erosion of PLGA microparticles (black arrow) after 1 day of degradation in water at 37 °C. (III) Characterization of PLGA microparticles containing NβL: a) size distribution of 500 particles and b) zeta potential (N = 3).

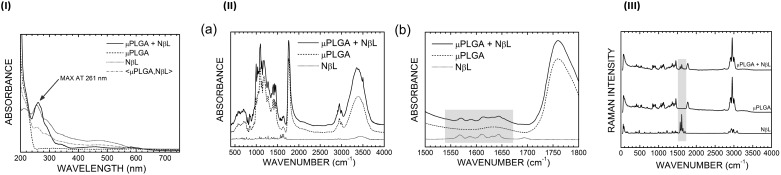

The incorporation of NβL into the microcapsules was also detected through spectroscopic techniques. Fig. 3(I) shows the UV-vis absorption curves of pure NβL, PLGA microparticles without the drug and PLGA microcapsules containing NβL molecules. One can see that the NβL molecule has its absorption onset at about 580 nm with two bumps at 470 nm and 285 nm and a pronounced maximum at 256 nm. The PLGA microcapsules, on the other hand, exhibit a sharp absorption onset at 250 nm. When both spectra are added and averaged (μPLGA,NβL, the dashed-dotted gray curve in Fig. 3(I)), the resulting plot resembles a scaled down version of the NβL loaded PLGA curve for wavelengths smaller than 305 nm. The NβL loaded PLGA UV-vis absorption spectrum, on the other hand, has a very pronounced maximum at 261 nm related to the NβL spectral peak at 256 nm and a small absorption bump at 580 nm. Other features of the NβL UV spectrum can be seen in Fig. 3(I) as well: absorption shoulders at 288, 339, and 453 nm are matched in the pure NβL spectrum with equivalent structures at 285, 343, and 470 nm.

Fig. 3. (I) Absorbance spectra of NβL (pure and encapsulated in PLGA microparticles) and PLGA microparticles without the drug (empty). The arrow shows the peak of NβL in the formulation containing the drug (black line). (II) (a) FT-IR spectra of pure NβL (dotted line), empty PLGA microparticles (dashed line) and PLGA microparticles containing nor-β-lapachone (solid line). (b) The gray rectangle highlights the peaks of NβL in the formulation containing the drug in the 1500–1800 cm–1 range. (III) Raman spectra of pure NβL, empty PLGA microparticles and PLGA microparticles containing NβL. The gray rectangle shows the signature peaks of NβL in the formulation containing the drug.

The FT-IR spectrum (Fig. 3, IIa) of the PLGA microcapsules loaded with NβL follows closely the spectrum of the unloaded microparticles, exhibiting a series of absorption bands between 490 and 780 cm–1 (related to CH bending vibrations), 980 and 1480 cm–1 (CH2 bending vibrations and wagging vibrations for the lowest wavenumbers, backbone CCO stretching vibrations for the highest wavenumbers), a sharp peak at about 1760 cm–1 (C O stretching vibrations), and bands centered at 2950 (CH2 stretching vibrations) and 3380 cm–1 (OH stretching motion). The pure NβL curve, in contrast, has a set of low intensity absorption bands scattered between 500 and 1740 cm–1 and high wavenumber bands at 2920 cm–1 and 3440 cm–1. In the region between 1500 and 1670 cm–1, one can see a set of characteristic peaks of NβL, which are also present in the NβL-loaded PLGA microcapsules (Fig. 3, IIb), but absent in the empty formulation. These peaks occur (for pure NβL) at wavenumbers 1568, 1587, 1611, 1631, and 1643 cm–1 (there is also a small absorption band at 1694 cm–1 which is barely visible in the PLGA microparticles with NβL resembling the E2g normal mode of benzene at 1763 cm–1). The peak at 1568 cm–1 can be assigned to the bending motion of the CH3 groups of the NβL molecule, while the 1587 cm–1 absorption band corresponds to the bending of two CH bonds in the benzene region of NβL (in the same fashion as the A2g normal mode of benzene at 1544 cm–1). At 1611, 1631, and 1643 cm–1, the vibrational modes can be depicted as CH3 scissoring motions and the combination of CH benzene bending (reminiscent of the E1u benzene normal mode at 1658 cm–1) with a small degree of C–C bond stretching. For the drug loaded PLGA microparticles, the same peaks in the order of increasing wavenumber occur at 1571, 1589, 1614, 1632, 1645, and 1693 cm–1, the first five exhibiting small blue shifts (of the order of 2 cm–1) with respect to the spectral curve of the isolated drug.

Fig. 3(III) shows the Raman spectra of the pure NβL, empty PLGA microcapsules and PLGA microcapsules containing NβL. The presence of NβL was verified by the appearance of four signature peaks in the 1560–1660 cm–1 wavenumber range, namely at 1571, 1591, 1614, and 1647 cm–1. The maxima at 1571 and 1591 cm–1 correspond to the infrared absorption lines observed at 1568 and 1587 cm–1, with the wavenumber differences being ascribed to experimental uncertainties. These lines involve CH3 and benzene ring vibrations, as described previously, while the Raman bands at 1614 and 1647 cm–1 are related to infrared absorption peaks at 1611 and 1643 cm–1 (also assigned to benzene ring normal modes), respectively. These Raman intensities are slightly blue shifted (by about 1 cm–1) for the PLGA microparticles with drug incorporation; the peak at 1571 cm–1 moves to 1572 cm–1, the peak at 1591 cm–1 shifts to 1594 cm–1, the 1614 cm–1 line stays at the same wavenumber, and the peak at 1647 cm–1 shifts to 1648 cm–1.

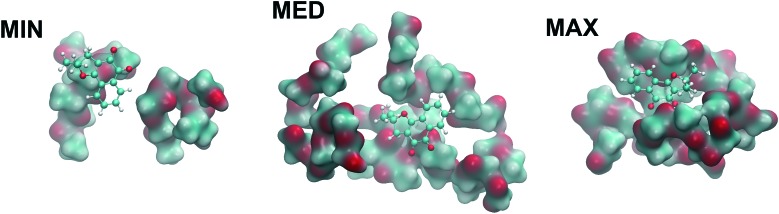

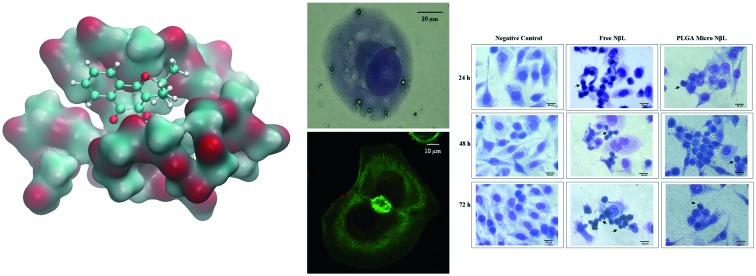

We have also established by computational analysis (Fig. 4) the optimized structures of PLGA chains with monomers of lactic acid and glycolic acid in a random sequence interacting with a single NβL molecule. After carrying out classical geometry optimizations and annealing computations, the best geometries were reoptimized using quantum density functional theory (DFT) in order to estimate the binding energy of NβL on the surface of a PLGA microparticle. It was observed that the polymeric structure is highly irregular before and after the classical annealing procedures, giving rise to connected clusters with dissimilar sizes and which are rich in indentations, cavities and clefts suitable for the binding of NβL. Monte Carlo calculations were employed to probe the surface of the annealed polymer, and 50 adsorption sites were found. Their adsorption energies were estimated to be ranging from –9.85 kcal mol–1 (physisorption or weak binding) to –31.5 kcal mol–1 (chemisorption or strong binding). Three of these structures were selected, with adsorption energies at the classical levels of –9.85 kcal mol–1 (MIN), –18.5 kcal mol–1 (MED), and –31.5 kcal mol–1 (MAX). Fig. 4 shows the DFT adsorption geometries obtained from these classically optimized structures using a GGA dispersion corrected exchange-correlation functional. In the maximum binding energy configuration, the NβL molecule is docked to a cleft where the effective contact surface with PLGA is the largest in comparison with the MED and MIN adsorption geometries and with a DFT adsorption energy of –40.9 kcal mol–1, which indicates a quantum correction to the classical energy of about –9.4 kcal mol–1 or, conversely, an increase in the binding energy of about 30%. For the MED geometry, the quantum correction was –8 kcal mol–1 (increase of 43% in the binding energy) and for the MIN case, –5.5 kcal mol–1 (56% increase in the binding energy). So it seems that the classical calculations tend to underestimate the strengths of both physisorption and chemisorption processes in the NβL-PLGA adsorbate. Adsorption energies calculated at the quantum level can be useful in the understanding of the drug loading process and are helpful to describe the first phase of the drug release kinetics (a burst release mechanism due to adsorption was observed in the NβL loaded microparticles). In particular, classical and quantum molecular dynamics simulations can be employed to investigate water solvation effects and the role of pH in the drug release mechanism from PLGA microparticle and nanoparticle surfaces.

Fig. 4. NβL molecule (orange) adsorbed on the PLGA structure in three configurations: MIN, MED, and MAX, which stand for minimum, medium and maximum adsorption energies.

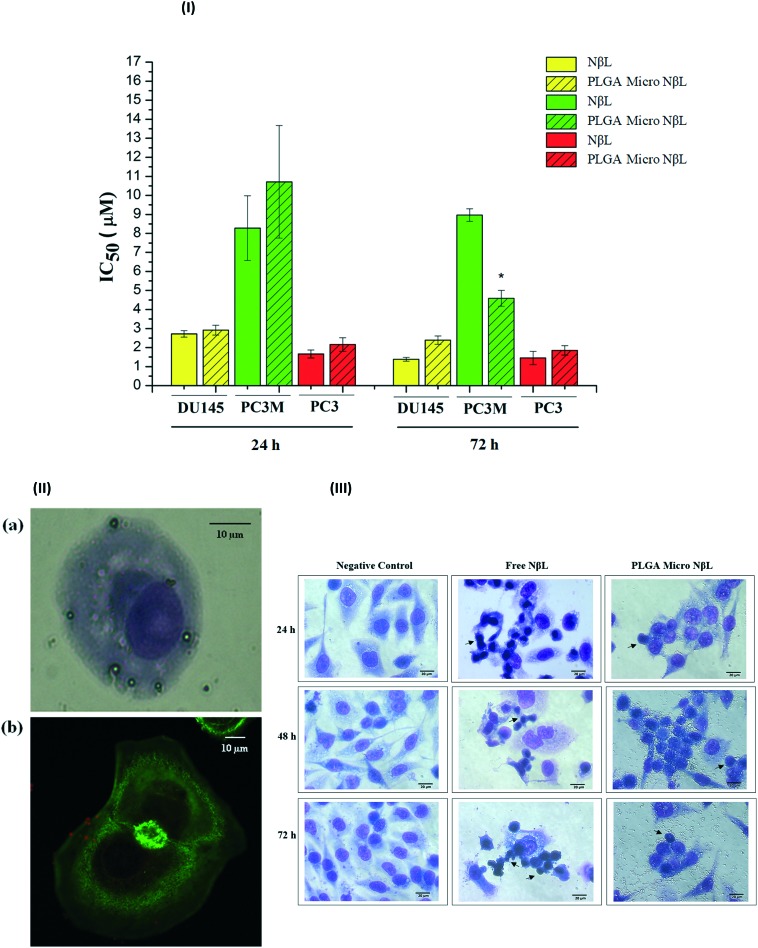

Finally, after the complete characterization of nor-β-lapachone-loaded microcapsules, their in vitro antiproliferative activity in human tumor cells was evaluated. MTT, a yellow dye that is reduced in living cells to form an insoluble dark blue product, was used to assess the cytotoxic effect of pure NβL, empty PLGA microcapsules and PLGA microcapsules containing NβL on tumor cell lines SF295, OVCAR-8, HCT-116, DU145, PC3M, and PC3. The IC50 data (μg mL–1 and μM) for the cytotoxic activity after 72 h are presented in Table 1, along with the data obtained for doxorubicin (positive control). PLGA microcapsules containing NβL demonstrated cytotoxic activity against all cell lines, giving high or moderate activity. PLGA microcapsules containing NβL showed greater sensitivity for the prostate cancer cell lines (DU145, PC3M and PC3). The IC50 values for the cytotoxic activity against these cells after 24 h and after 72 h are shown in Fig. 6(I). According to Pérez-Sacau et al.,33 compounds are classified according to their activity as highly active (IC50 < 1 μg mL–1), moderately active (1 μg mL–1 < IC50 < 10 μg mL–1) or inactive (10 μg mL–1 > IC50). Encapsulated NβL has the best inhibitory activity for the PC3M cell line, in which the PLGA microcapsules containing NβL exhibited a higher activity than the free drug. As can be seen from Fig. 6(I), PC3M cells exhibited the maximum activity of the encapsulated drug after just 24 h. After incubation for 24 h, the IC50 values of the free and encapsulated NβL formulations were 1.887 (1.54–2.31) and 2.442 (1.86–3.21) μg mL–1, respectively. After 72 h, the corresponding values were 2.045 (1.971–2.122) and 1.046 (0.82–1.34) μg mL–1, and after 96 h they were 1.787 (1.63–1.96) and 1.401 (1.20–1.64) (data not shown in the graph). The free drug was mostly toxic towards PC3M cells within the first 24 h and no additional cytotoxicity was observed until 96 h, probably due to its potent cytotoxicity. We suggest that in 72 h, the activity of the NβL-loaded PLGA microcapsules was increased because of the higher concentration of the drug within the cells. For PC3, no difference in cytotoxicity between free and encapsulated NβL was observed in 24 and 72 h. For DU145, differences were not observed between free and encapsulated NβL in 24 h; however, in 72 h, a superior cytotoxic activity was observed in the free drug. For DU145 and PC3, there was no difference between the cytotoxicity profiles of free and encapsulated NβL in 72 h and 96 h. That is, the maximal cytotoxic activity was achieved in 72 h. Aiming to exclude possible cytotoxic effects of the microcapsules without the drug, a cytotoxicity test was also carried out in empty microcapsules. Empty PLGA microcapsules did not demonstrate proliferative inhibition at the maximum concentration of 10 μM (2.28 μg mL–1). Alamar Blue, a non-fluorescent dye that is reduced to a pink-colored fluorescence, was used to evaluate the in vitro cytotoxic activity on primary cell cultures (PBMC). The IC50 data (μg mL–1 and μM) are displayed in Table 1. Pure NβL and PLGA microcapsules containing NβL did not present proliferative inhibition at the maximum concentration of 2.28 μg mL–1 (10 μM) on PBMC. Alamar Blue is widely used to investigate the selective cytotoxicity of compounds toward normal proliferating cells because of its low toxicity to normal cells. Optical microscopy experiments revealed that the microcapsules adhered to the surface and then were phagocytized (Fig. 6, II). In Fig. 6, IIa, it is possible to see the internalization after 20 min of treatment in PLGA microcapsules containing NβL in DU145 cells. Confocal microscopy imaging showed the PLGA microcapsules around the cell membrane (Fig. 6, IIb) after 60 min of treatment; however, the internalization was not clear. Fig. 6(III) shows the morphological changes in the PC3M prostate cell line caused by free and encapsulated NβL in 24, 48 and 72 h. Changes over time in the cell cytoplasm and death by apoptosis were observed.

Table 1. Cytotoxic activity expressed as IC50 for pure NβL, PLGA microcapsules containing NβL and Dox (positive control) after 72 h of exposure to different cancer cell lines.

| Compounds | IC50 μg mL–1 (μM) (CI 95%) – 72 h |

||||||

| Pure NβL | SF-295 (glioblastoma) | OVCAR-8 (ovarian) | HCT-116 (colon) | DU145 (prostate) | PC3M (prostate) | PC3 (prostate) | PBMC a |

| 0.330 (1.447) | 0.588 (2.579) | 0.359 (1.575) | 0.316 (1.386) | 2.045 (8.969) | 0.331 (1.453) | ||

| 0.219–0.496 (0.961–2.175) | 0.515–0.672 (2.246–2.947) | 0.268–0.481 (1.175–2.110) | 0.299–0.335 (1.311–1.469) | 1.971–2.122 (8.643–9.307) | 0.261–0.420 (1.144–1.844) | >2.28 (10.000) | |

| PLGA microcapsules containing NβL | 1.688 (7.404) | 3.132 (13.737) | 1.706 (7.482) | 0.543 (2.382) | 1.046 (4.587) | 0.423 (1.854) | |

| 0.950–2.990 (4.167–13.114) | 2.674–3.668 (11.728–16.088) | 1.246–2.335 (5.465–10.241) | 0.495–0.597 (2.171–2.618) | 0.818–1.340 (3.593–5.856) | 0.370–0.482 (1.624–2.116) | >2.28 (10.000) | |

| Dox | 0.217 (0.399) | 0.337 (0.620) | 0.120 (0.221) | 0.083 (0.153) | 0.200 (0.368) | 0.240 (0.442) | 0.924 (1.700) |

| 0.158–0.239 (0.291–0.440) | 0.310–0.364 (0.570–0.670) | 0.090–0.170 (0.166–0.313) | 0.006–0.115 (0.011–0.212) | 0.170–0.230 (0.313–0.423) | 0.210–0.270 (0.386–0.497) | 0.489–1.685 (0.900–3.100) | |

aThe Alamar Blue assay was performed on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) after 72 h of drug exposure. Doxorubicin (Dox) was the positive control. CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 6. (I) IC50 for free and encapsulated NβL (PLGA micro NβL) after 24 and 72 h of incubation in human prostate cell lines. *With significant difference from the PLGA micro NβL (24 h) group (p < 0.05) according to ANOVA and Tukey's test. (II) Photomicrographs illustrating the interaction of the DU145 cancer cell line with PLGA microparticles containing NβL. (a) Optical microscopy image of DU145 cells phagocyting PLGA microparticles containing NβL after 20 min of treatment, with a magnification of ×400; (b) confocal fluorescence microscopy image of microparticles containing NβL (red particles) in the membrane of DU145 cells after 60 min of treatment, with a magnification ×600. (III) Nor-β-lapachone induces morphological changes in PC3M human prostate cell lines. Microscopic analysis of hematoxylin/eosin-stained cells after 24, 48 and 72 h of incubation with free nor-β-lapachone (NβL) at 11.2 μM and PLGA microcapsules containing nor-β-lapachone (PLGA Micro NβL) at 5.4 μM. The cells were analyzed by light microscopy (400×). The black arrows show cells in different stages of apoptosis.

The thermograms of the pure NβL, empty PLGA microcapsules and PLGA microcapsules containing NβL are shown in Fig. 5. The DSC trace of the pure NβL shows a sharp endothermic peak at 192.04 °C, which corresponds to its melting point (Fig. 5, Ia). This peak was not observed in the PLGA microcapsules containing NβL. The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and the differential thermal analysis (DTA) thermograms are shown in Fig. 5(Ib) and (Ic), respectively. The thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) of the PLGA microcapsules containing NβL showed a mass gain due to decomposition (Fig. 5, Ib). Several preparations were made to optimize the drug entrance into the microcapsules. Microcapsules were prepared from PLGA 50 : 50 with different drug/polymer ratios (1 : 10–1 : 30). The 1 : 20 drug/polymer ratio showed the maximum efficiency in the drug encapsulation with a total drug loading of 1.19 ± 0.07% and an encapsulation efficiency of 19.36 ± 1.15%. The in vitro release kinetics of NβL-loaded microcapsules was monitored in PBS buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. The NβL release from the microcapsules followed a biphasic profile (Fig. 5II). In the first 6 hours, around 70% of the total amount of drug was released. An initial burst effect was observed with around 90.05 ± 6.76% of the drug released within 24 h followed by a sustained release for an extended time period.

Fig. 5. (I) Thermal analysis of pure NβL (dotted lines), empty PLGA microparticles (dashed lines) and PLGA microparticles containing NβL (solid lines). (a) Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC); (b) thermogravimetric analysis (TG); (c) differential thermal analysis (DTA). (II) Release profile of NβL from PLGA microparticles, under physiological conditions, at 37 °C in PBS buffer (pH 7.4). Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of three experiments.

As drug carriers, microparticles have been demonstrated to be very promising for the treatment of several types of cancer.25a,c,34 In this work, the encapsulation of NβL, a lipophilic synthetic naphthoquinone, in PLGA microparticles has proven to be a considerable challenge. Numerous encapsulation protocols have been described in the literature, the selection of the method being dependent on the chemical properties of the compound. For hydrophobic compounds, o/w methods are frequently used, in which the polymer and the drug are dissolved together in an organic phase.35 This encapsulation method has been used for anticancer drugs such as aclarubicin, lomustine, and paclitaxel.31a Due to the increased solubility of NβL in the aqueous phase constituted of PVA solution by the o/w technique, the o/w/o approach has been regarded as a possible alternative to improve the drug entrapment. However, NβL encapsulation was possible in this work only by the simple emulsion (o/w) technique.

The microcapsules formulated here showed good morphological characteristics. The NβL loading had no effect on the surface morphology in comparison with empty microcapsules. The SEM images (Fig. 2, IID), on the other hand, revealed that the microcapsule degradation involves swelling, loss of form and erosion. The less negative value of the zeta potential in the PLGA microcapsules containing NβL clearly points to the adsorption of the drug by the microparticles, while the UV absorption bands and the FT-IR spectra (benzene ring infrared absorption bands) of both pure NβL and PLGA microcapsules containing NβL confirmed the drug loading. However, no significant differences in the position of the absorption spectral bands of NβL were observed, indicating the absence of strong chemical interactions between NβL and PLGA. Raman spectroscopy, which is a useful method to reveal the solid-state interactions between molecules,36 validated the presence of drug non-covalently bound to the microcapsules as well. The adsorption geometry of a single NβL in PLGA was modelled using classical molecular dynamics, annealing and DFT geometry optimization, revealing that the drug is adsorbed with binding energies varying from –6 kcal mol–1 (physisorption) to –52 kcal mol–1 (chemisorption). At the same time, thermal analysis has established that the incorporation of NβL changes the thermal properties of the microcapsules. The absence of the peak corresponding to the melting point of pure NβL in the PLGA microcapsules containing NβL suggests that the drug was dissolved or molecularly dispersed within the polymer in an amorphous fashion, with no drug crystallization during the microencapsulation process,27a,f helping the diffusion and dissolution of NβL in the release medium, corroborating the TEM results which showed no drug crystals at the surface of the microparticles. DSC analysis reinforced this picture.

One can assume that the low amount of encapsulated drug (1.19% w/w loading) is due to the drug diffusion to the external aqueous phase. According to Shahani and Panyam,37 many hydrophobic drugs have been encapsulated in PLGA microparticles using o/w emulsion solvent evaporation with loading values of 10–20% (w/w), but it is not always possible to achieve a high drug loading through this technique.

The in vitro drug release rate of polymeric microparticles can be influenced by several factors, including the type and composition of the polymer, porosity, particle size, proportion of non-encapsulated drug and formation of drug crystals on the surface of the microcapsules.26a,31a The release profile of NβL from the PLGA microcapsules in this study occurred in two stages. An initial burst release phase takes place within the first day, followed by a second gradual release phase. According to Wischke and Schwendeman,31a this burst release effect has often been attributed to the drug adsorbed on the surface, which results in greater initial drug diffusivity. The initial burst observed here has often been reported.27a,c,f Indeed, the o/w method is able to transport drug molecules to the microparticle surface due to the flow of the solvent out of the oil phase during solvent evaporation.31a

From Table 1, one can see that PLGA microcapsules containing NβL exhibit cytotoxic activity against all the cancer cell lines investigated but did not show higher activity than pure NβL for the following cell lines: SF-295 (glioblastoma), OVCAR-8 (ovarian) and HCT-116 (colon). Encapsulated NβL exhibited the best inhibitory activity against the human prostate cancer cell lines. For DU145 and PC3M, the maximum activity of the drug could already be observed within 24 h (Fig. 5) as the in vitro drug release was around 90% in this time interval. Empty PLGA microcapsules showed negligible cytotoxicity, with no effect on cell proliferation. These results are satisfactory concerning the PLGA biocompatibility and the presence of possible residues from the formulation process (organic solvent, PVA solution).38 Simón-Yarza and coworkers39 mentioned in their work the differences between drug release under in vitro conditions (PBS at 37 °C, under shaking) and that in tissue, in which the drug release decelerates. Thus, the release profile in vivo will probably be different, with the peak plasma level of the drug going below 90% after 24 h. The microscopy data reveal that microcapsules containing NβL are quickly internalized, causing cell death through apoptosis as can be seen from images of cellular reduction, chromatin condensation, cell fragmentation and bleb formation.40

3. Conclusions

In this study, a PLGA microparticle-based drug delivery system was developed for NβL using the emulsion solvent evaporation method. Simple o/w and w/o/w emulsions were tested to optimize the formulation, and microcapsules with good morphological features were obtained. The characterization of NβL by UV spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy and FT-IR spectroscopy techniques confirmed the occurrence of drug loading with vibrational signatures related to the benzene ring normal modes of NβL. Classical molecular dynamics, annealing and quantum DFT calculations carried out to investigate the interaction of a NβL molecule with the PLGA microparticle surface revealed the occurrence of physisorption and chemisorption processes. DSC analysis and microscopy data suggest that NβL is incorporated in an amorphous state dispersed into the polymer. In terms of the in vitro drug release profile, NβL had an initial burst release within the first day, followed by a constant release rate afterwards. Cytotoxicity studies indicated that PLGA microcapsules containing NβL exhibited cytotoxic activity against various cancer cell lines, with better activity against prostate cancer cells (DU145, PC3M and PC3). Moreover, the cytotoxic activity of NβL against PC3M cells was more effective when the drug was delivered in PLGA microcapsules in comparison with the free drug, indicating that microcapsules containing NβL could be a promising drug delivery system for prostate anticancer treatment.

Conflicts of interest

These authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Brazilian Research Agency CNPq for financial support through projects 550579/2012-5 (Edital Jovens Pesquisadores), 305385/2014-3, PVE 401193/2014-4, 402329/2013-9, 470767/2012-0 and Edital Universal MCTI/CNPq No 01/2016. E. W. S. C. received financial support from CNPq project 307843/2013-0 and FUNCAP (Fundação Cearense de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Brazil). C. P. received financial support from CNPq through projects 555020/2010-0 and 490045/2011-1 (FUNCAP-PRONEX). E. N. S. J. would like to thank the Programa Pesquisador Mineiro PPM-X, FAPEMIG (APQ-02478-14) and INCT-catálise.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: All the experimental details. See DOI: 10.1039/c7md00196g

References

- (a) Harlozinska A. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3327–3333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Goon P. P. Y., Lip G. Y. H., Boos C. J., Stonelake P. S., Blann A. D. Neoplasia. 2006;8:79–88. doi: 10.1593/neo.05592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lobo N. A., Shimono Y., Qian D., Clarke M. F. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;23:675–699. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram J. S. Mol. Aspects Med. 2001;21:167–223. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(00)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparre G., Porcelli A. M., Lenaz G., Romeo G. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a011411. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Hanahan D., Weinberg R. A. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hanahan D., Weinberg R. A. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Feinberg A. P., Tycko B. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:143–153. doi: 10.1038/nrc1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vecchio L., Etet P. F. S., Kipanyula M. J., Krampera M., Kamdje A. H. N. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1836:90–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman D. J., Cragg G. M. J. Nat. Prod. 2016;79:629–661. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Esteves-Souza A., Figueiredo D. V., Esteves A., Câmara C. A., Vargas M. D., Pinto A. C., Echevarria A. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2007;40:1399–1402. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2006005000159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bonifazi E. L., Ríos-Luci C., León L. G., Burton G., Padrón J. M., Misico R. I. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:2621–2630. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) de Castro S. L., Emery F. S., da Silva Júnior E. N. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;69:678–700. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) da Silva Júnior E. N., Jardim G. A. M., Menna-Barreto R. F. S., de Castro S. L. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2014;25:1780–1798. [Google Scholar]; (e) Hosamani B., Ribeiro M. F., da Silva Júnior E. N., Namboothiri I. N. N. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016;14:6913–6931. doi: 10.1039/c6ob01119e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei P., Zhang X., Tu S., Yan S., Ying H., Ouyang P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:828–830. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Bolton J. L., Trush M. A., Penning T. M., Dryhurst G., Monks T. J. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000;13:135–160. doi: 10.1021/tx9902082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sagar S., Kaur M., Minneman K. P., Bajic V. B. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:3519–3530. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Vessecchi R., Emery F. S., Galembeck S. E., Lopes N. P. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2010;24:2101–2108. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Júnior E. N., Souza M. C. B. V., Pinto A. V., Pinto M. C. F. R., Goulart M. O. F., Barros F. W. A., Pessoa C., Costa-Lotufo L. V., Montenegro R. C., Moraes M. O., Ferreira V. F. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:7035–7041. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Marinho-Filho J. D. B., Bezerra D. P., Araújo A. J., Montenegro R. C., Pessoa C., Diniz J. C., Viana F. A., Pessoa O. D. L., Silveira E. R., Moraes M. O., Costa-Lotufo L. V. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2010;183:369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Salustiano E. J. S., Netto C. D., Fernandes R. F., Silva A. J. M., Bacelar T. S., Castro C. P., Buarque C. D., Maia R. C., Rumjanek V. M., Costa P. R. R. Invest. New Drugs. 2010;28:139–144. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9231-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Siegel D., Yan C., Ross D. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012;83:1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ríos-Luci C., Bonifazi E. L., León L. G., Montero J. C., Burton G., Pandiella A., Misico R. I., Padrón J. M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;53:264–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=lapachone&Search=Search. Accessed April 10, 2017.

- Rocha D. R., Souza A. C. G., Resende J. A. L. C., Santos W. C., Santos E. A., Pessoa C., Moraes M. O., Costa-Lotufo L. V., Montenegro R. C., Ferreira V. F. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:4315–4322. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05209h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos J. R. G., Prieto J. M., Heinrich M. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;121:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco E., Bey E. A., Dong Y., Weinberg B. D., Sutton D. M., Boothman D. A., Gao J. Cancer Res. 2007;70:3896–3904. [Google Scholar]

- Seoane S., Díaz-Rodríguez P., Sendon-Lago J., Gallego R., Pérez-Fernández R., Landin M. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013;84:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang S. B., Kim D., Kim S. Y., Park C., Jeong J. H., Kuh H. J., Lee J. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2013;17:9–13. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2013.17.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S. Y., Park S. J., Yoon S. M., Jung J., Woo H. N., Yi S. L., Song S. Y., Park H. J., Kim C., Lee J. S., Choi E. K. J. Controlled Release. 2009;139:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti I. M. F., Mendonça E. A. M., Lira M. C. B., Honrato S. B., Camara C. A., Amorim R. V. S., Mendes Filho J., Rabello M. M., Hernandes M. Z., Ayala A. P., Santos-Magalhães N. S. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011;44:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) da Cruz E. H. G., Carvalho P. H. P. R., Corrêa J. R., Silva D. A. C., Diogo E. B. T., de Souza Filho J. D., Cavalcanti B. C., Pessoa C., de Oliveira H. C. B., Guido B. C., da Silva Filho D. A., Neto B. A. D., da Silva Júnior E. N. New J. Chem. 2014;38:2569–2580. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jardim G. A. J., Guimarães T. T., Pinto M. C. F. R., Cavalcanti B. C., de Farias K. M., Pessoa C., Gatto C. C., Nair D. K., Namboothiri I. N. N., da Silva Júnior E. N. Med. Chem. Commun. 2015;6:120–130. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bahia S. B. B. B., Reis W. J., Jardim G. A. M., Souto F. T., de Simone C. A., Gatto C. C., Menna-Barreto R. F. S., de Castro S. L., Cavalcanti B. C., Pessoa C., Araujo M. H., da Silva Júnior E. N. Med. Chem. Commun. 2016;7:1555–1563. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Júnior E. N., Deus C. F., Cavalcanti B. C., Pessoa C., Costa-Lotufo L. V., Montenegro R. C., Moraes M. O., Pinto M. C. F. R., Simone C. A., Ferreira V. F., Goulart M. O. F., Andrade C. K. Z., Pinto A. V. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:504–508. doi: 10.1021/jm900865m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti B. C., Barros F. W. A., Cabral I. O., Ferreira J. R. O., Magalhães H. I. F., Júnior H. V. N., da Silva Júnior E. N., Abreu F. C., Costa C. O., Goulart M. O. F., Moraes M. O., Pessoa C. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011;24:1560–1574. doi: 10.1021/tx200180y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida E. R., Lucena F. R. S., Silva C. V. N. S., Costa-Junior W. S., Cavalcanti J. B., Couto G. B. L., Silva L. L. S., Mota D. L., Silveira A. B., Sousa Filho S. D., Silva A. C. P. Phytother. Res. 2009;23:1276–1280. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Farazuddin M., Sharma B., Khan A. A., Joshi B., Owais M. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012;7:35–47. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S24920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fattal E., Barratt G. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009;157:179–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang Z., Chui W. K., Ho P. C. Pharm. Res. 2011;28:585–596. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kim I., Byeon H. J., Kim T. H., Lee E. S., Oh K. T., Shin B. S., Lee K. C., Youn Y. S. Biomaterials. 2013;33:5574–5583. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Lin R., Ng L. S., Wang C. H. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4476–4485. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen Z. Trends Mol. Med. 2010;16:594–602. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sah H., Thoma L. A., Desu H. R., Sah E., Wood G. C. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013;8:747–765. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S40579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Zidan A. S., Sammour O. A., Hammad M. A., Megrab N. A., Hussain M. D., Khan M. A., Habib M. J. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2006;7:E38–E46. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jackson J. K., Hung T., Letchford K., Burt H. M. Int. J. Pharm. 2007;342:6–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wischke C., Zhang Y., Mittal S., Schwendeman S. P. Pharm. Res. 2010;27:2063–2074. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0202-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhang Y. H., Yue Z. J., Zhang H., Tang G. S., Wanga Y., Liu J. M. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2010;76:371–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang Y. H., Zhang H., Liu J. M. Med. Oncol. 2011;28:901–906. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9531-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Ossa D. H. P., Lorente M., Gil-Alegre M. E., Torres S., García-Taboada E., Aberturas M. R., Molpeceres J., Velasco G., Torres-Suárez A. I. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundargi R. C., Babu R. V., Rangaswamy V., Patel P., Aminabhavi T. M. J. Controlled Release. 2008;125:193–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredenberg S., Wahlgren M., Reslow M., Axelsson A. Int. J. Pharm. 2011;415:34–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M. P., Feitosa A. C. S., Oliveira F. C. E., Cavalcanti B. C., da Silva Jr. E. N., Dias G. G., Sales F. A. M., Sousa B. L., Barroso-Neto I. L., Pessoa C., Caetano E. W. S., Fiore S. D., Fischer R., Ladeira L. O., Freire V. N. Molecules. 2016;21:873. doi: 10.3390/molecules21070873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Wischke C., Schwendeman S. P. Int. J. Pharm. 2008;364:298–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fujii S., Okada M., Nishimura T., Maeda H., Sugimoto T., Hamasaki H., Furuzono T., Nakamura Y. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;374:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateh D. D., Leinster V. H., Lambert S. R., Shah A., Khan A., Walklin H. J., Johnstone J. V., Ibrahim N. I., Kadam M. M., Malik Z., Gironès M., Veldhuis G. J., Warnes G., Marino S., McNeish I. A., Martin J. E. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8538–8547. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Sacau E., Díaz-Peñate R. G., Estévez-Braun A., Ravelo A. G., García-Castellano J. M., Pardo L., Campillo M. J. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:696–706. doi: 10.1021/jm060849b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanda D. S., Tyagi P., Mirvish S. S., Kompella U. B. J. Controlled Release. 2013;168:239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellach M., Margel S. Chem. Cent. J. 2011;5:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-5-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L. S., Langkilde F. W., Zografi G. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001;90:888–901. doi: 10.1002/jps.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahani K., Panyam J. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011;100:2599–2609. doi: 10.1002/jps.22475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y., Wu J., Yin G., Huang Z., Yao Y., Liao X., Chen A., Pu X., Liao L. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2008;70:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simón-Yarza T., Formiga F. R., Tamayo E., Pelacho B., Prosper F., Blanco-Prieto M. J. Int. J. Pharm. 2013;440:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore S. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007;35:495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.