Abstract

Phosphorus (P) is arguably more limiting than nitrogen for forest ecosystems being free of disturbances for lengthy time periods. The elucidation of multivariate relationships between foliar P and its primary drivers for dominant species is an urgent issue and formidable challenge for ecologists. Our goal was to evaluate the effects of primary drivers on foliar P of Quercus wutaishanica, the dominant species in broadleaved deciduous forest at the Loess Plateau, China. We sampled the leaves of 90 Q. wutaishanica individuals across broad climate and soil nutrient gradients at the Loess Plateau, China, and employed structural equation models (SEM) to evaluate multiple causal pathways and the relative importance of the drivers for foliar P per unit mass (Pmass) and per unit area (Parea). Our SEMs explained 73% and 81% of the variations in Pmass and Parea, respectively. Pmass was negatively correlated to leaf mass per area, positively correlated to leaf area, and increased with mean annual precipitation and total soil potassium. Parea was positively correlated to leaf mass per area, leaf dry weight, and increased significantly with total soil potassium. Our results demonstrated that leaf P content of Q. wutaishanica increased with total soil potassium in the Loess Plateau accordingly.

Introduction

Leaf nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) play crucial roles in productivity and other biological processes [1–6]. In terrestrial ecosystems, N and P are the most common limiting elements, either individually, and/or in combination [7–11]. Nitrogen supply increases with on-going increases in atmospheric N deposition [12]. By contrast, a fixed complement of P is primarily derived from rock weathering, and even very small losses of P may not be readily replenished [13]. The availability of P declines during long-term ecosystem development, and may eventually lead to P-deficient soils [5, 7, 13]. Although N is frequently proposed as the primary limiting nutrient in forests (particularly in boreal and temperate biomes), P is arguably more limiting for systems that have been free of disturbances for lengthy time periods [11, 14].

This relative P limitation may be further intensified under continuous and widespread anthropogenic N emissions [11, 15]. High N deposition, typically from anthropogenic emissions, decreases soil C:N ratio and increases N supply to plants [12]. In China, which is currently, by far, the largest creator and emitter of anthropogenic N globally, foliar N was observed to increase significantly between 1980 and 2000 across all plant species; however, foliar P was not altered over the same time period [15]. As a vital element for energy storage and cell structure, P has emerged as a key limiting nutrient to plant development and growth, spanning from regional to global scales [1, 4, 16].

Leaf P per mass (Pmass) and per unit area (Parea) are two important indices for leaf P status, and their respective advantages remain under discussion. Pmass appeals more to researchers who are concerned with plant growth and economics, such as resource investment and return, whereas Parea has a greater appeal for researchers who are interested in photosynthetic physiology, which focuses on the implementation of leaf functions [17–19].

On an extensive regional or global scale, leaf resident N and P increases from the tropics to the cooler and drier mid-latitudes [7]. Moreover, the first global quantification of the relationship between leaf phosphorus status and soil nutrients indicated that leaf P was positively correlated to soil P; however, soil P was negatively associated with precipitation [20]. Thus, it remains unclear as to whether foliar P is determined by soil P or precipitation. Potassium (K) is the most abundant cation in plant cells and the second most abundant nutrient after N in leaves, but is a limited nutrient in 70% of all studied terrestrial ecosystems [21]. Soil K is critical to K supply for plants because the loss of K from leaves through leaching is more pronounced than for other elements [22, 23]. K deficiency reduced photosynthesis [4], and impaired phloem transport of sucrose to root systems, which are important for the fine root growth and absorption of mineral nutrients, including P [24–28]. We therefore hypothesize that soil resident K is positively associated with foliar P.

The intraspecific relationships between leaf morphological traits (LMT) and leaf P gradually got more attention in recent years, especially for widespread species. Leaf mass per area (LMA) quantifies the leaf dry-mass investment per unit of light-intercepting leaf area [29, 30]. The negative correlations between LMA and Pmass were observed in Phragmites australis and Robinia pseudoacacia [31, 32], which was coordinated with the relationships at interspecific scale [17, 31, 33, 34]. The limitation of P initiates reductions in leaf area (LA) and leaf growth due to both the direct effects of P shortage on leaf expansion rates, and the reduction of assimilation products that are required for growth [35, 36]. However, the associations between LA and leaf dry weight (LDW), which are independent of LMA [37–39], and foliar P remain poorly understood.

Recent literature has revealed that intraspecific variation in leaf traits is greater than previously supposed [40, 41]. To better understand the determinants of foliar P within species, we studied the Pmass and Parea of the Liaotung oak (Quercus wutaishanica), which is a dominant and widely distributed species of the temperate deciduous broad-leaved forests along natural gradients of climate and soil nutrient variability in the Loess Plateau, in Northern China [42]. Here, we tested following hypotheses that: (i) in addition to LMA, LA and LDW may also contribute to the variation of foliar P; (ii) the influences of environmental, especially for soil K, and leaf trait variables on Pmass and Parea differ in strength and even directions. By using structural equation modeling (SEM) [43], we examined the influences of climate, soil nutrients, and the morphological traits of leaves on the variations in leaf Pmass and Parea of Q. wutaishanica.

Materials and methods

Study area

This study was conducted on the Loess Plateau in Northern China, where Q. wutaishanica is primarily distributed. The 30 sites were distributed across six mountains, with the same locations as Xing, Kang (28) (Table 1 and S1 Table). The mean annual temperature (MAT) and mean annual precipitation (MAP) ranged from 4.1 to 10.3 °C, and 554 to 880 mm, respectively, whereas the elevation ranged from 1252 to 2303 m (Table 1). In the upper 0–20 cm soil layer, total soil N, P, K were on average 2.48 mg g-1, 0.52 mg g-1, and 19.57 mg g-1, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Description of sampling range, environmental conditions, and leaf traits.

| Variables | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation (m) | 1700 | -- | 1252 | 2303 | -- |

| Longitude (°) | -- | -- | 106.68233 | 113.50182 | -- |

| Latitude (°) | -- | -- | 34.04959 | 37.13302 | -- |

| MAT (°C) | 6.7 | 1.84 | 4.1 | 10.3 | 27 |

| MAP (mm) | 637 | 94.47 | 554 | 889 | 15 |

| TSN (mg g-1) | 2.48 | 1.84 | 0.90 | 9.60 | 71 |

| TSK (mg g-1) | 19.57 | 2.56 | 14.10 | 25.90 | 13 |

| TSP (mg g-1) | 0.52 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 1.30 | 39 |

| LMA (g m-2) | 77.06 | 2.16 | 35.18 | 132.85 | 23 |

| LA (cm2 leaf-1) | 35.82 | 11.31 | 19.50 | 72.40 | 28 |

| LDW (g leaf-1) | 0.27 | 14.01 | 0.13 | 0.51 | 30 |

| Nmass (mg g-1) | 23.59 | 3.42 | 17.60 | 33.70 | 15 |

| Narea (g m-2) | 1.79 | 0.39 | 1.00 | 3.10 | 22 |

| Pmass (mg g-1) | 1.12 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 1.88 | 26 |

| Parea (g m-2) | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 34 |

| Kmass (mg g-1) | 6.71 | 1.44 | 2.79 | 10.88 | 21 |

| Karea (g m-2) | 0.51 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.94 | 29 |

| N:P ratio | 21.78 | 0.54 | 13.15 | 41.76 | 20.8 |

Abbreviations: MAT, mean annual temperature; MAP, mean annual precipitation; TSN, total soil nitrogen; TSK, total soil potassium; TSP, total soil phosphorus; LMA, leaf mass per area; LA, leaf area; LDW, leaf dry weight; Pmass, leaf phosphorus per unit mass; Nmass, leaf nitrogen per unit mass; Kmass, leaf potassium per unit mass; Narea, leaf nitrogen per unit area; Parea, leaf phosphorus per unit area; Karea, leaf potassium per unit area; SD, standard deviation; CV, the coefficient of variation.

Sample collection

To ensure a wide coverage of habitat conditions, we selected sample sites at every 100-m elevation interval on each of the six mountains, and a total of 90 samples from 30 sites were collected. Subsequent to confirming that every sample site was at least 50 m from any clearing, and 100 m from any roadway, we randomly sampled three healthy Q. wutaishanica trees, and collected 20 canopy leaves from the sun-exposed side of each tree. Within a 400 m2 vicinity, three soil samples were randomly collected from a 0–20 cm soil depth, where the bulk of the fine roots of most plants occur, and large amounts of N, P, and K accumulate, due to uplift and release at the surface by plants through litter fall and fine root turnover [44, 45]. Three soil samples were combined to make a composite sample from each sample site, yielding a total 30 composite soil samples for laboratory analysis [46].

Variable measurements

Leaf nutrients and morphological traits were measured or calculated for each sampled Q. wutaishanica tree. We determined the average LA (cm2 leaf-1) of each tree by scanning the fresh leaves. Subsequent to oven drying these leaf samples at 80°C for 48 hours, we quantified the average LDW (g leaf-1), and LMA (g m-2) was calculated by LDW/LA. The oven-dried samples were then pulverized using a plant sample mill and sieved through a 0.15 mm mesh screen. We employed the CHNS element analyzer (Vario EL III, Elementar Analyser systeme GmbH, Hanau, Germany) to determine the N concentrations (Nmass, mg g-1) of each sample. The P concentrations (Pmass, mg/g) of each sample were quantified using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry measurements (ICP-AES, SPECTRO ARCOS EOP, SPECTRO, Germany) after dissolved 65% nitric acid (HNO3). The Parea and Narea were calculated as Pmass and Nmass × LDW/LA, respectively [47].

Soil samples were oven-dried at 50°C to constant weight, pulverized using a soil sample mill, sieved through a 0.15 mm mesh screen, and then analyzed for total soil nitrogen (TSN) (mg g-1) via the CHNS element analyzer (Vario EL III, Elementar Analyser systeme GmbH, Hanau, Germany). Total soil P (TSP) and total soil K (TSK) were quantified using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry measurements (ICP-AES, SPECTRO ARCOS EOP, SPECTRO, Germany) after microwave-digestion with for HCl-HNO3 (3:1 by volume) (Sandroni and Smith 2002).

Mean annual temperature (MAT) and mean annual precipitation (MAP) were extracted from the WorldClim spatial climate data (period from 1950 to 2000 with resolution at ca 1 km, available at www.worldclim.org/) based on spatial coordinates (latitude, longitude, and elevation). The spatial location, i.e., latitude, longitude, and elevation, of each sample tree was determined via GPSMAP 629sc (Garmin).

Data analyses

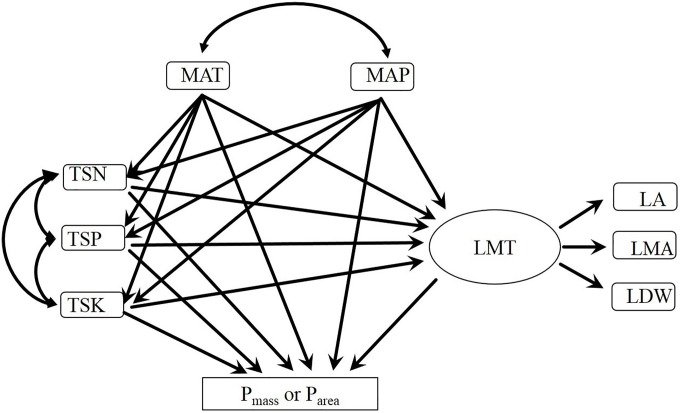

Structural equation models (SEMs) have been increasingly employed in ecology to separate direct and indirect effects between exogenous and endogenous variables [48–50]. An integrative modeling approach has led to a major advance in the ability to discern underlying processes in ecological systems [51]. We first examined the bivariate correlation between variables, and then established an a priori model based on a known theoretical construct, according to the previous foliar P studies mentioned above, including key variables and possible paths (Table 1, Fig 1). LMA, LDW, and LA are pairwise correlated leaf morphological traits influencing leaf P. In order to represent the synthetic effects on foliar P, three traits were incorporated into leaf morphological trait (LMT), which was the theoretical concept that combined three manifest variables to a latent variable (Fig 1). Each of the three observable soil nutrient variables (TSN, TSP, and TSK) had its path to foliar P, due to their different roles in plant physiology and growth [52]. MAT and MAP also had separate paths to soil nutrients, LMT and foliar P (Fig 1). Subsequently, we employed stepwise procedures, guided by Akaike information criterion values, to obtain the most parsimonious set of predictors [48]. We adopted several indices to evaluate the suitability of the final models: the chi-square test (χ2), the root square mean error of approximation (RMSEA), the adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), the normed fit index (NFI) and χ2/d.f. (NC) [53]. SEM analyses were performed with AMOS 20.0 package, and correlation analyses were performed with IBM SPSS 20.0.0 (IBM SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Fig 1. The a priori model for leaf P concentrations.

Single headed arrows indicate a causal influence of one variable upon another. Double headed arrows indicate correlation between two variables. Abbreviations: MAT, mean annual temperature; MAP, mean annual precipitation; TSN, total soil nitrogen; TSK, total soil potassium; TSP, total soil phosphorus; LMT, leaf morphological trait; LMA, leaf mass per area; LA, leaf area; LDW, leaf dry weight; Pmass, leaf phosphorus per unit mass; Parea, leaf phosphorus per unit area.

Results

Correlations between leaf P content, leaf morphological traits and environmental factors

Pmass was negatively correlated to LMA (Table 2) and positively correlated to LA (Table 2), and Parea was positively correlated to LMA and LDW (Table 2). Both Pmass and Parea increased caused by higher TSK (Table 2). There was also positive correlation between TSK and TSP (Table 2), and both of which decreased caused by higher MAP (Table 2). There were no clear relationships between MAT, TSN and leaf traits.

Table 2. Pearson correlation coefficients between variables.

| Pmass | Parea | Nmass | Narea | Kmass | Karea | LMA | LDW | LA | TSN | TSK | TSP | MAT | |

| Parea | 0.63*** | ||||||||||||

| Nmass | 0.61*** | 0.11 | |||||||||||

| Narea | 0.13 | 0.76*** | 0.06 | ||||||||||

| Kmass | 0.58*** | 0.25* | 0.40** | -0.04 | |||||||||

| Karea | 0.23 | 0.70 | -0.13 | 0.68** | 0.54** | ||||||||

| LMA | -0.26* | 0.54*** | -0.53*** | 0.74*** | -0.23 | 0.63** | |||||||

| LDW | 0.22 | 0.50*** | -0.03 | 0.45*** | 0.16 | 0.47** | 0.38** | ||||||

| LA | 0.42*** | 0.05 | 0.39** | -0.17 | 0.38** | -0.03 | -0.34** | 0.69*** | |||||

| TSN | -0.02 | 0.10 | -0.23 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.09 | -0.07 | ||||

| TSK | 0.37** | 0.60*** | 0.18 | 0.55*** | 0.11 | 0.39** | 0.35** | 0.28* | 0.03 | -0.08 | |||

| TSP | 0.03 | 0.23 | -0.07 | 0.27* | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.30* | 0.23 | -0.01 | 0.03 | 0.58*** | ||

| MAT | -0.05 | -0.03 | -0.17 | -0.04 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.06 | -0.06 | -0.11 | -0.07 | 0.09 | 0.13 | |

| MAP | 0.03 | -0.02 | -0.21 | -0.17 | 0.12 | 0.04 | -0.03 | -0.02 | -0.03 | 0.59*** | -0.53*** | -0.36** | -0.34** |

Significances are at P < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), and < 0.001 (***). Abbreviations: MAT, mean annual temperature; MAP, mean annual precipitation; TSN, total soil nitrogen; TSK, total soil potassium; TSP, total soil phosphorus; LMA, leaf mass per area; LA, leaf area; LDW, leaf dry weight; Nmass, leaf nitrogen per unit mass; Narea, leaf nitrogen per unit area; Pmass, leaf phosphorus per unit mass; Parea, leaf phosphorus per unit area; Kmass, leaf potassium per unit mass; Karea, leaf potassium per unit area.

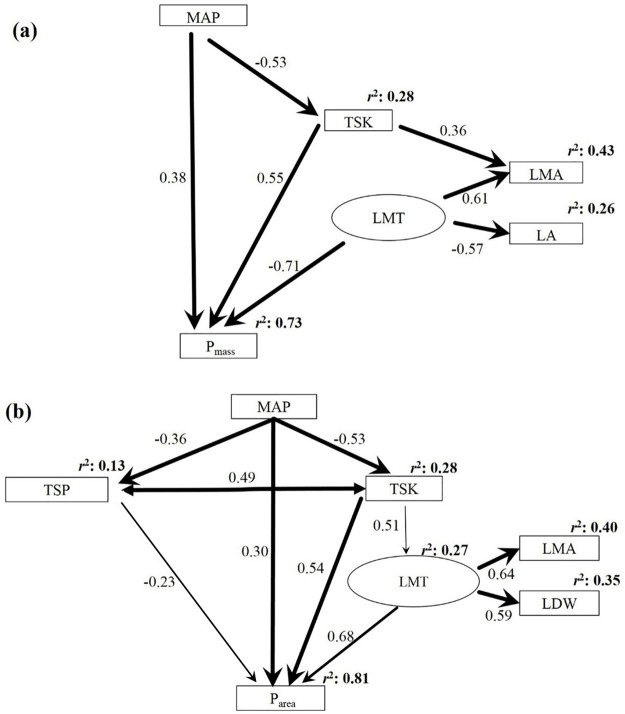

The final SEM model for Pmass

The final SEM model for Pmass had a good fit to the data, and explained 73% of the variation in Pmass (Tables 3 and 4, Fig 2a). The model revealed that Pmass was impacted by leaf morphological traits (including LMA and LA), MAP, and TSK. Leaf morphological traits had the largest standardized total effect on Pmass (-0.71) among all factors (Table 4, Fig 2a). Increasing TSK led to an increase in Pmass (0.55). MAP had a positive direct effect Pmass, but a negative indirect effect via TSK (Table 4, Fig 2a). As the direct and indirect effects of MAP on Pmass were approximately the same (but in opposite directions), MAP had a limited total effect (0.09) on Pmass (Table 4).

Table 3. Structural equation model fit indices and evaluation criteria.

| Indices | Evaluation criteria or critical value for fit | Pmass | Parea |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | P > 0.05 | χ2 = 2.886 P = 0.410 |

χ2 = 5.162 P = 0.396 |

| RMSEA | < 0.08 | 0.000 | 0.022 |

| NC | < 3 | 0.946 | 1.034 |

| AGFI | > 0.9 | 0.919 | 0.902 |

| NFI | > 0.9 | 0.968 | 0.965 |

χ2, the chi-square test; RMSEA, the root square mean error of approximation; AGFI, the adjusted goodness of fit index; NFI, the normed fit index; NC, χ2 divided by its degrees of freedom; Pmass, leaf P concentration per unit mass; Parea, leaf P concentration per unit area.

Table 4. Paths and standardized effects each predictor for foliar P.

| Model | Predictor | Paths | Standardized effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pmass | MAP | Direct | 0.38*** |

| Indirect through TSK | -0.29*** | ||

| Total | 0.09 | ||

| TSK | Direct | 0.55*** | |

| Indirect | -- | ||

| Total | 0.55 | ||

| LMT (LMA and LA) | Direct | -0.71*** | |

| Indirect | -- | ||

| Total | -0.71 | ||

| Parea | MAP | Direct | 0.30*** |

| Indirect through TSK | -0.47** | ||

| Indirect through TSP | 0.08* | ||

| Total | -0.09 | ||

| TSK | Direct | 0.54*** | |

| Indirect through LMT | 0.35** | ||

| Total | 0.89 | ||

| TSP | Direct | -0.23* | |

| Indirect | -- | ||

| Total | -0.23 | ||

| LMT (LMA and LDW) | Direct | 0.68** | |

| Indirect | -- | ||

| Total | 0.68 |

Significant effects are at P < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), and < 0.001 (***). MAP, mean annual precipitation; TSK, total soil potassium; TSP, total soil phosphorus; LMT, leaf morphological trait; LMA, leaf mass per area; LA, leaf area; LDW, leaf dry weight; Pmass, leaf phosphorus per unit mass; Parea, leaf phosphorus per unit area.

Fig 2. Final SEMs linking Pmass and Parea and their drivers.

Single headed arrows indicate a causal influence of one variable upon another. Narrow arrows indicate P < 0.05; wider arrows indicate P < 0.01; and the widest arrows indicate P < 0.001. Values on arrows indicate standardized coefficients. The value at the top-right corner of each variable (r2) represents the proportion of variance explained. Abbreviations: MAP, mean annual precipitation; TSK, total soil potassium; TSP, total soil phosphorus; LMT, leaf morphological trait; LMA, leaf mass per area; LA, leaf area; LDW, leaf dry weight; Pmass, leaf phosphorus per unit mass; Parea, leaf phosphorus per unit area.

The final SEM model for Parea

The final SEM model for Parea also fit well with the data, and explained 81% of the variation in Parea (Tables 3 and 4, Fig 2b). Parea was influenced by leaf morphological traits (including LMA and LDW), MAP, TSK, and TSP. Leaf morphological traits had an effect on Parea (0.68) (Table 4, Fig 2b). MAP had a positive direct effect (0.30), a negative indirect effect via TSK (-0.47), and a positive indirect effect via TSP (0.08), resulting in a total effect of -0.09 on Parea (Table 4). TSK had a positive direct (0.54) and a positive indirect effect through leaf morphological traits (0.35) on Parea. TSP had a negative direct effect Parea (-0.23), and was positively correlated with TSK (0.49) (Table 4, Fig 2b).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first attempt to describe intraspecific leaf P variation across a large geographic scale. Meanwhile, mean value of leaf N:P ratio exceeding the Redfield ratio suggested the P limited status (N:P ratio = 16) of our research subjects [13, 54], which made our research on the primary drivers on leaf P more necessary. Directly comparing the significant correlations of total soil potassium and leaf P and non-significant correlations of total soil phosphorus and leaf P, we were naturally impressed by the larger role of soil K in determining leaf P instead of soil P, meanwhile multiple determinants of the leaf phosphorus status can provide us more evidences. Using structural equation models, we discovered that the Pmass and Parea of Q. wutaishanica in Northern China were collectively influenced by leaf morphological traits, mean annual precipitation, and soil nutrients. These complex Pmass and Parea associated causal relationships would be difficult to obtain from small-scale experiments, or empirical bivariate studies.

Characteristics of the leaf Pmass and Parea variation in Q. wutaishanica across the Loess Plateau

We found that Pmass and Parea were linked with leaf morphological traits. Consistent with previous interspecific findings [33, 34], LMA was negatively correlated to Pmass, and positively correlated to Parea. Across plant species, leaf assimilation capacity per unit area positively correlated to Narea and Parea and increased with increasing LMA [34]. By contrast, the foliage assimilation capacity per unit mass positively correlated to Nmass and Pmass [17], and scaled negatively with LMA [29]. The positive correlation between LMA and Parea found in Q. wutaishanica suggested that leaves of higher LMA enhanced the quantity of photosynthetic tissues per unit area, similar to the relationship between LMA and Narea across species from different habitats [29, 34]. Increases in LMA prompt the enhancement of the intercellular transfer resistance to CO2, and decreases in assimilative leaf compounds, thus leading to the negative correlation between LMA and Pmass, similar to the relationship between LMA and Nmass [29, 34]. Collectively, the relationships between foliar P content and LMA in Q. wutaishanica were similar to those reported across a range of species [34].

Relationship between leaf P content and leaf morphological traits

With the influences of LMA simultaneously accounted for in our structural equation models, we found, in agreement with our hypothesis, that there were also positive correlations between LA and Pmass, and between LDW and Parea. The negative correlation between LMA and LA was similar to the results of Q. ilex [55], indicating a reduction in support tissue per unit area as the leaf area increases within species. Higher Pmass, and thus higher net photosynthetic rate per mass [54] in larger leaves appears to be an adaptation of lower LMA [33]. The positive correlation between LA and Pmass may have resulted from the positive effects of leaf P concentration on leaf expansion rates, and the increased production of assimilates required for growth over the duration of expansion [36].

Important effects of both total soil K and P on leaf P content according to the SEMs

We revealed positive effects of total soil K on Pmass, and Parea. The positive effects of soil K on both Pmass and Parea of Q. wutaishanica from direct and indirect paths supported the hypothesis that soil K plays critical roles in increasing foliar P. Although leaves of K-deficient plants accumulate sugars, they rarely increase their root biomass, because they are less able to translocate sucrose to the root via the phloem [24], which decreases root and/or mycorrhizal fungi biomass for the absorption of P [25, 27]. These processes may be responsible for the positive effects of soil K both Pmass and Parea we observed in the system with low environmental availability of inorganic P [8, 15].

We found no significant effects of soil resident P on foliar Pmass, but a negative direct effect of soil P on Parea, while soil N had little effects on either Pmass or Parea. Typically, plant and soil P are coupled [54, 56], and the Pmass of 753 terrestrial plant species increased significantly with increasing soil P in China [8]. The lack of the effect of soil P on Pmass in our study may be attributed to that photosynthetic products that are prioritized to meet requirements for the growth of roots rather than leaves in low soil P habitats to ensure a necessary supply of P [4, 24, 52, 54, 56–57]. It means that coupled change between leaf P supply and photosynthetic production allocated to leaves lead to the non-significant correlation between Pmass and soil P, even though soil P of more than 6-fold was reported here. Although our bivariate analysis showed a positive effect of TSP on Parea, similar to those reported previously [34, 58], our SEM analysis indicates that the direct effect of TSP on Parea was negative, but complimented by the positive effect of TSK on Parea.

These complex relationships likely involve several mechanisms. In a P limited environment, plants reduce disparities in the supply of photosynthetic products and nutrients by enhancing their capacity to acquire the most limiting resource [59], leading to the allocation of additional photosynthetic products to root systems and less to leaf biomass. Higher plant nutrient concentrations in nutrient-poor environments enhanced their competitive capacity associated with plant growth capacity[16], meanwhile, plants increase leaf thickness in order to cope with low soil P [29]. Therefore, the negative direct effect of soil P on Parea likely reflects the collective influence of reduced photosynthetic product supplies to leaves and increased leaf thickness for more proportion of mesophyll tissue [29]. Conversely, increasing soil P associated with increasing soil K, due to their simultaneous provision from weathering of parent materials and uplift, and release at the surface soil layer by plants through litter fall and fine root turnover [44, 45] impart a positive effect on Parea. Unlike the overwhelmingly demonstrated positive effects of P addition on Pmass [11], little is known about the P addition effects on Parea. To better elucidate the influence of soil P on Parea, future methodical experiments may further verify the complex mechanisms that we observed in our study.

Different paths leading to the combined effects of precipitation on leaf P content

In contrast to regional and global level reports [7, 17], mean annual temperature had no effect on leaf traits in our study (which might have resulted from the limited temperature variation in our sample set), and was thus excluded from our SEMs. Consistent with Ordoñez, Van Bodegom (20) and Maire, Wright (34), the variation of Pmass and Parea that could be explained by mean annual precipitation was exacted but modest. Nonetheless, the direct positive and indirect negative effects of precipitation on Pmass and Parea were all of significance. This key environmental variable should not be simply ignored due to the different mechanisms involved with direct and indirect effects. Forest sites that receive higher precipitation are typically characterized by the augmented downward transport of humic substances in the soil profile, and enhanced transmission of nutrients within the rhizosphere [60], which might assist with increasing the P supply for Q. wutaishanica. Nevertheless, the indirect effect of precipitation on foliar P content, mediated via TSK, was negative. This was likely due to soil P and K leaching losses, which increased in conjunction with precipitation [22, 23].

Our study revealed the variation of Pmass and Parea in Quercus wutaishanica leaves along with multiple factors in the Loess Plateau, China. Consistent with previous interspecific findings, we revealed that leaf mass per area was negatively correlated with Pmass, and positively correlated with Parea. We also observed positive correlations between leaf dry weight and Parea, and between leaf area and Pmass. We found that total soil K was the most critical environmental driver for leaf P, whereas the total P concentration of the soil had no effect on Pmass. Moreover, our SEM highlighted a direct negative effect of total soil P on Parea, and indicated that the positive bivariate correlation between total soil P and Parea masked the direct negative effect of total soil P, and positive effect of total soil K on Parea. Future nutrient addition experiments might facilitate the testing of mechanistic links between soil P, soil K, and leaf P, particularly Parea, by simultaneously examining above- and belowground nutrient allocation and leaf morphological acclimation, meanwhile researches focusing on the mechanism of soil K in determining leaf P and accurate proportion of leaf K, P taken up from different soil layers have important implications in understanding the forest potassium and phosphorus cycling.

Supporting information

MAT, mean annual temperature; MAP, mean annual precipitation.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors owe many thanks to Danhui Liu, Yu Liang, Guoyi Wang and Tan Liu for their assistance with field data collection and nutrient determination work.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the project funded by the State Key Laboratory of Earth Surface Processes and Resource Ecology, Beijing Normal University, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41630750), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41271059), and the National Key Basic Research Special Foundation of China (No. 2011FY110300), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2014KJJCB33). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Chapin FS III (1980) The mineral nutrition of wild plants. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 11:233–260. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sterner RW, Elser JJ (2002) Ecological stoichiometry: the biology of elements from molecules to the biosphere. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuan Z, Chen HY (2012) A global analysis of fine root production as affected by soil nitrogen and phosphorus. Proc R Soc Lond, Ser B: Biol Sci 279:3796–3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marschner H, Marschner P (2012) Marschner’s mineral nutrition of higher plants. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aerts R, Chapin F III (2000) The mineral nutrition of wild plants revisited: a re-evaluation of processes and patterns. Adv Ecol Res 30:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elser JJ, Fagan WF, Denno RF, Dobberfuhl DR, Folarin A, Huberty A, et al. (2000) Nutritional constraints in terrestrial and freshwater food webs. Nature 408:578–580. 10.1038/35046058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reich PB, Oleksyn J (2004) Global patterns of plant leaf N and P in relation to temperature and latitude. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:11001–11006. 10.1073/pnas.0403588101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han W, Fang J, Guo D, Zhang Y (2005) Leaf nitrogen and phosphorus stoichiometry across 753 terrestrial plant species in China. New Phytol 168:377–385. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01530.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wardle DA, Walker LR, Bardgett RD (2004) Ecosystem properties and forest decline in contrasting long-term chronosequences. Science 305:509–513. 10.1126/science.1098778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y, Han W, Tang L, Tang Z, Fang J (2013) Leaf nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations of woody plants differ in responses to climate, soil and plant growth form. Ecography 36:178–184. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan Z, Chen HY (2015) Decoupling of nitrogen and phosphorus in terrestrial plants associated with global changes. Nature Clim Change 5:465–469. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Högberg P (2012) What is the quantitative relation between nitrogen deposition and forest carbon sequestration? Global Change Biol 18:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vitousek PM, Porder S, Houlton BZ, Chadwick OA (2010) Terrestrial phosphorus limitation: mechanisms, implications, and nitrogen-phosphorus interactions. Ecol Appl 20:5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Augusto L, Achat DL, Jonard M, Vidal D, Ringeval B (2017) Soil parent material-A major driver of plant nutrient limitations in terrestrial ecosystems. Global Change Biol 23:3808–3824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Zhang Y, Han W, Tang A, Shen J, Cui Z, et al. (2013) Enhanced nitrogen deposition over China. Nature 494:459–462. 10.1038/nature11917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sardans J, Bartrons M, Margalef O, Gargallo‐Garriga A, Janssens IA, Ciais P, et al. (2017) Plant invasion is associated with higher plant–soil nutrient concentrations in nutrient‐poor environments. Global Change Biol 23:1282–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright IJ, Reich PB, Westoby M, Ackerly DD, Baruch Z, Bongers F, et al. (2004) The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428:821–827. 10.1038/nature02403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westoby M, Reich PB, Wright IJ (2013) Understanding ecological variation across species: area-based vs mass-based expression of leaf traits. New Phytol 199:322–323. 10.1111/nph.12345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lloyd J, Bloomfield K, Domingues TF, Farquhar GD (2013) Photosynthetically relevant foliar traits correlating better on a mass vs an area basis: of ecophysiological relevance or just a case of mathematical imperatives and statistical quicksand? New Phytol 199:311–321. 10.1111/nph.12281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ordoñez JC, Van Bodegom PM, Witte JPM, Wright IJ, Reich PB, Aerts R (2009) A global study of relationships between leaf traits, climate and soil measures of nutrient fertility. Global Ecol Biogeogr 18:137–149. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sardans J, Peñuelas J (2015) Potassium: a neglected nutrient in global change. Global Ecol Biogeogr 24:261–275. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levia DF, Frost EE (2006) Variability of throughfall volume and solute inputs in wooded ecosystems. Prog Phys Geog 30:605–632. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tukey H Jr (1970) The leaching of substances from plants. Annual review of plant physiology 21:305–324. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marschner H, Kirkby E, Cakmak I (1996) Effect of mineral nutritional status on shoot-root partitioning of photoassimilates and cycling of mineral nutrients. J Exp Bot 47:1255–1263. 10.1093/jxb/47.Special_Issue.1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brundrett M (2002) Coevolution of roots and mycorrhizas of land plants. New Phytol 154:275–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maathuis FJM (2009) Physiological functions of mineral macronutrients. Curr Opin Plant Biol 12:250–258. 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hermans C, Hammond JP, White PJ, Verbruggen N (2006) How do plants respond to nutrient shortage by biomass allocation? Trends Plant Sci 11:610–617. 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xing K, Kang M, Chen HY, Zhao M, Wang Y, Wang G, et al. (2016) Determinants of the N content of Quercus wutaishanica leaves in the Loess Plateau: a structural equation modeling approach. Scientific reports 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niinemets Ü (1999) Research review. Components of leaf dry mass per area—thickness and density—alter leaf photosynthetic capacity in reverse directions in woody plants. New Phytol 144:35–47. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poorter H, Niinemets Ü, Poorter L, Wright IJ, Villar R (2009) Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA): a meta‐analysis. New Phytol 182:565–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu Y-K, Pan X, Liu G-F, Li W-B, Dai W-H, Tang S-L, et al. (2015) Novel evidence for within-species leaf economics spectrum at multiple spatial scales. Front Ecol Plant Sci 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin T, Liu G, Fu B, Ding X, Yang L (2011) Assessing adaptability of planted trees using leaf traits: A case study with Robinia pseudoacacia L. in the Loess Plateau, China. Chinese Geographical Science 21:290–303. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright IJ, Reich PB, Westoby M (2001) Strategy shifts in leaf physiology, structure and nutrient content between species of high‐and low‐rainfall and high‐and low‐nutrient habitats. Funct Ecol 15:423–434. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maire V, Wright IJ, Prentice IC, Batjes NH, Bhaskar R, Bodegom PM, et al. (2015) Global effects of soil and climate on leaf photosynthetic traits and rates. Global Ecol Biogeogr 24:706–717. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynch J, Läuchli A, Epstein E (1991) Vegetative growth of the common bean in response to phosphorus nutrition. Crop Sci 31:380–387. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodríguez D, Zubillaga M, Ploschuk E, Keltjens W, Goudriaan J, Lavado R (1998) Leaf area expansion and assimilate production in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) growing under low phosphorus conditions. Plant and soil 202:133–147. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cordell S, Goldstein G, Meinzer F, Handley L (1999) Allocation of nitrogen and carbon in leaves of Metrosideros polymorpha regulates carboxylation capacity and δ13C along an altitudinal gradient. Funct Ecol 13:811–818. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleiman D, Aarssen LW (2007) The leaf size/number trade‐off in trees. J Ecol 95:376–382. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Royer DL, McElwain JC, Adams JM, Wilf P (2008) Sensitivity of leaf size and shape to climate within Acer rubrum and Quercus kelloggii. New Phytol 179:808–817. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02496.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richardson SJ, Allen RB, Buxton RP, Easdale TA, Hurst JM, Morse CW, et al. (2013) Intraspecific relationships among wood density, leaf structural traits and environment in four co-occurring species of Nothofagus in New Zealand. PloS one 8:e58878 10.1371/journal.pone.0058878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu T, Wang GG, Wu Q, Cheng X, Yu M, Wang W, et al. (2014) Patterns of leaf nitrogen and phosphorus stoichiometry among Quercus acutissima provenances across China. Ecol Complex 17:32–39. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen J, Wu Z-y, Raven PH (1999) Flora of China. Beijing: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grace JB, Schoolmaster DR, Guntenspergen GR, Little AM, Mitchell BR, Miller KM, et al. (2012) Guidelines for a graph-theoretic implementation of structural equation modeling. Ecosphere 3:art73. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jobbágy EG, Jackson RB (2004) The uplift of soil nutrients by plants: biogeochemical consequences across scales. Ecology 85:2380–2389. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan Z, Chen HY (2010) Fine root biomass, production, turnover rates, and nutrient contents in boreal forest ecosystems in relation to species, climate, fertility, and stand age: literature review and meta-analyses. Crit Rev Plant Sci 29:204–221. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu C-C, Tsui C-C, Hseih C-F, Asio VB, Chen Z-S (2007) Mineral nutrient status of tree species in relation to environmental factors in the subtropical rain forest of Taiwan. For Ecol Manage 239:81–91. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cornelissen JHC, Lavorel S, Garnier E, Diaz S, Buchmann N, Gurvich DE, et al. (2003) A handbook of protocols for standardised and easy measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Aust J Bot 51:335–380. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jonsson M, Wardle DA (2010) Structural equation modelling reveals plant-community drivers of carbon storage in boreal forest ecosystems. Biol Lett 6:116–119. 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Chen HY (2015) Individual size inequality links forest diversity and above‐ground biomass. J Ecol 103:1245–1252. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gaitán JJ, Oliva GE, Bran DE, Maestre FT, Aguiar MR, Jobbágy EG, et al. (2014) Vegetation structure is as important as climate for explaining ecosystem function across Patagonian rangelands. J Ecol 102:1419–1428. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grace JB, Anderson TM, Seabloom EW, Borer ET, Adler PB, Harpole WS, et al. (2016) Integrative modelling reveals mechanisms linking productivity and plant species richness. Nature 529:390–393. 10.1038/nature16524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pallardy SG (2008) Physiology of woody plants. 3rd edn ed San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grace JB (2006) Structural equation modeling and natural systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chapin FS, Matson PA, Vitousek PM (2011) Principles of terrestrial ecosystem ecology. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Niinemets Ü (2015) Is there a species spectrum within the world-wide leaf economics spectrum? Major variations in leaf functional traits in the Mediterranean sclerophyll Quercus ilex. New Phytol 205:79–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hedin LO (2004) Global organization of terrestrial plant–nutrient interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:10849–10850. 10.1073/pnas.0404222101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fujita K, Kai Y, Takayanagi M, El-Shemy H, Adu-Gyamfi JJ, Mohapatra PK (2004) Genotypic variability of pigeonpea in distribution of photosynthetic carbon at low phosphorus level. Plant Sci 166:641–649. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu F, Lu X, Mo J (2014) Phosphorus limitation on photosynthesis of two dominant understory species in a lowland tropical forest. J Plant Ecol 7:526–534. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bloom AJ, Chapin FS, Mooney HA (1985) Resource limitation in plants-an economic analogy. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 16:363–392. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meier I, Leuschner C (2014) Nutrient dynamics along a precipitation gradient in European beech forests. Biogeochemistry 120:51–69. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

MAT, mean annual temperature; MAP, mean annual precipitation.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.