Development in metal based radiopharmaceuticals – review on design considerations, ongoing research and future directions.

Development in metal based radiopharmaceuticals – review on design considerations, ongoing research and future directions.

Abstract

The growing epidemiological and economic burden of neurological diseases on society is tremendous. A correct and timely diagnosis can help in lowering the burden and improving the life quality of both the diseased person and the caretaker. Imaging of the brain (neuroimaging) using CT, MRI, and nuclear imaging methods can provide anatomical and functional information. Neuroreceptors are central to neurotransmission and neuromodulation in the CNS. In vivo imaging of receptors in the brain provides powerful tools for the functional study of the central nervous system (CNS) in normal or diseased states. Presently, PET imaging using non-metallic radiotracers dominates the imaging of neuroreceptors. Metal-based probes for SPECT and PET can be economical and logistically easier to use without compromising the information. This review focuses on the development of metallic radiotracers for (99mTc) SPECT and (68Ga) PET along with future directions based on the metallic probes developed for other imaging modalities namely MRI.

Introduction

The growing epidemiological and economic burden of neurological diseases on society is tremendous. A correct and timely diagnosis can help in lowering the burden and improving the life quality of both the diseased person and the caretaker.1 A century ago, diagnosis relied on the physiological and psychological symptoms. The most definitive diagnosis was autopsy carried out only after the patient had died. Later invasive methods like intraventricular sampling and microdialysis were used for diagnosis. Autoradiographic studies and other in vitro tests are carried out postmortem. These studies could answer the effects of late stage diseases on proteins and the effect caused by medications.2 There was no way for early intervention to prevent or delay the advancement of diseases. Research in diagnostic sciences aims for early and accurate prediction of diseases. Diagnosis of neurological disorders can also benefit from advances in diagnostic sciences. Advances in diagnostics have allowed clinicians to “see” a living brain through imaging and predict the onset of a disease much before the symptoms appear.

Imaging sciences can be broadly classified into anatomical imaging and functional imaging. Since neurological disorders affect the brain at both anatomical and functional levels, diagnostic imaging plays a significant role in understanding brain anatomy and function. Both kinds of information are central to the diagnosis and management of neurological disorders including therapeutic interventions.

What is neuroimaging and neuroreceptor imaging?

Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging is imaging of the brain using CT, MRI, and nuclear imaging methods and can provide anatomical and functional information. Neuroimaging studies have extended the understanding of the brain by giving information on the location, propagation, and connections of brain activity at the physiological level. These studies can:

1. Help to gain insight into the mechanism of a disease;

2. Assist in assessing the disruption as a result of a disorder;

3. Assist in drug development which includes the interaction of the drug at the target site and evaluation of the pharmacodynamics parameters;

4. Clinically, assist in therapeutic intervention by assessing the drug action; and

5. Can help in planning of personalized medicine.

CT and MRI are the major players for anatomical imaging. Functional imaging relies on PET, SPECT, and functional MRI. Functional MRI relies on the localized changes in water and tissue composition. PET/SPECT requires specific probes. The specific probes can be based on metabolites or specific ligands or inhibitors against receptors or enzymes, respectively.

Neuroreceptor imaging

Neuroreceptors (henceforth referred as receptors) are central to neurotransmission and neuromodulation in the CNS. These are present on the surface of the neurons and interact with neurotransmitters, release chemical messengers and make neuron–neuron or neuron–target cell communication possible. Thus, receptors are the key to understanding the functional activity of the brain and in vivo imaging of the receptors enables to “see” the functional activity. In vivo imaging of receptors in the brain provides powerful tools for the functional study of the central nervous system (CNS) in normal or diseased states. Information from neuroreceptor imaging when compared with the information obtained biochemically can commensurate receptor occupancy, receptor-mediated signaling and vascular response in the CNS. The assumption is that the target receptor should have an adequate density which can be detected in normal and (or) diseased states.

Methods for neuroreceptor imaging

Presently, PET, SPECT and MRI imaging modalities can be used for neuroreceptor imaging. These techniques provide a non-invasive quantitative measurement of receptors and their activity. The requirement is a highly specific and selective probe targeted against a particular receptor. Signals which are detected by the imaging modality arise as a result of radioactive decay in the case of PET/SPECT or as the contrast in MRI. Each modality has its pros and cons. PET has higher resolution, higher sensitivity, and better quantitative capability than SPECT/MRI. SPECT is more accessible since more hospitals are equipped with SPECT scanners than PET, economically viable (also referred as poor man's PET), and therefore, more practical as a routine procedure than PET. SPECT is more sensitive than MRI. MRI has no radiation burden associated. Other methods that are currently being developed are based on optical and ultrasound receptor imaging.

As early as 1979, Eckelman et al.3 stated that “Radiotracers that bind to receptors appear to be a potential source of radiopharmaceuticals that could give important information about the changes in receptor concentration or the appearance of receptors as a function of a specific pathologic state.” Since then, a large number of radiotracers have been developed and validated and are currently being used clinically. Initial studies for neuroreceptor imaging comprise muscarinic cholinergic receptors and dopamine. Quantification of brain receptor concentrations began with the first PET study published in 1983, wherein dopamine receptors were imaged using the radioligand 3-N-11C-methylspiperone.4 After these groundbreaking studies, in a span of nearly 35 years, many neuroreceptors have been targeted in normal and diseased states.

What is being accomplished through neuroreceptor imaging includes:

1. Brain regional distribution of receptors;

2. Receptor density;

3. Receptor occupancy;

4. Structural state of the receptor: monomer or higher state; and

5. Functional state of the receptor: high affinity or low affinity state.

Current status of the literature

In the past SPECT and PET tracers for brain imaging have been reviewed. Table 1 covers some of the reviews dedicated to the development of radioligands for neuroreceptors.

Table 1. Comprehensive list of reviews.

| 2003: Radiopharmaceuticals for single-photon emission computed tomography brain imaging5 |

| Article focuses on 123I and 99mTc-based radiotracers for brain-imaging agents that have shown clinical usefulness |

| Receptor- and site-specific brain-imaging agents have been discussed for • Benzodiazepine-receptor imaging agents; • Dopamine D2/D3 receptors; • Dopamine-transporter imaging agents; • Serotonin-transporter imaging agents; • Muscarinic-receptor imaging agents; and • Nicotinic-receptor imaging agents |

| 2010: Molecular tracers for PET and SPECT imaging of diseases6 |

| Introduction to PET/SPECT and applications (cancer and neurodegenerative diseases) |

| Discusses neuroreceptor imaging as part of: PET imaging of neurodegenerative diseases |

| SPECT imaging of neurodegenerative diseases and head injury |

| 2012: Radiotracers for SPECT imaging: current scenario and future prospects7 |

| Article covers introduction to 123I and 99mTc, chemistry involved, and SPECT radiotracers for neurology |

| 2013: Special issue: carbon-11 and fluorine-18 chemistry devoted to molecular probes for imaging the brain with PET: Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals8 |

| 2014: PET/SPECT imaging agents for neurodegenerative diseases9 |

| Introduction to radiopharmaceuticals and isotopes for PET and SPECT imaging |

| SPECT/PET imaging agents are useful in diagnosis and monitoring disease progression |

| Specific examples on in vivo imaging of dopamine transporters for the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease |

| Specific examples of in vivo imaging agents for mapping amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's disease |

What follows from these reviews is that PET tracers 11C and 18F and the SPECT tracer 123I have dominated neuroreceptor imaging. All the three radionuclides are non-metallic radiotracers. Further, all the three radionuclides are cyclotron produced. Metallic radionuclide 99mTc (SPECT) has been reported for the development of neuroreceptor imaging though with limited success. The only 99mTc radioligand that has been proven successful is 99mTc-[TRODAT].

This limited success can be attributed to the design challenges involved in designing metallic radionuclide bearing radiotracers. The introduction of 11C, 18F or 123I in the pharmacophore scaffold with the least disturbance in bio-affinity towards the target is possible. In contrast, the introduction of a metallic radionuclide can result in large disturbances of the electronic distribution leading to variations in bio-affinity. The following question arises: why at all is there a need for metallic radiotracers when these are associated with more uncertainties? Advantage of using metallic radiotracers is the availability in case the radionuclide is generator produced. Thus, for SPECT imaging among the metal radionuclides 99mTc, 111In, and 67Ga, 99mTc gets an edge as it is generator produced. 111In and 67Ga are cyclotron produced radionuclides. Similarly, among the choices for PET metal radionuclides (64Cu, 89Zr, 68Ga, 86Y, and 82Rb), 68Ga and 82Rb are generator produced. However, 82Rb has a very short half-life of only 75 s, thereby making it suitable only for very fast acquisitions. 64Cu and 89Zr have low positron abundance resulting in poorer image quality and longer scanning duration. Thus, metallic radiotracers for diagnostics predominantly are either based on 99mTc (SPECT) or 68Ga (PET). The use of these radionuclides can have a high societal impact as these are generator produced and hence, more economical and can be made widely available. The impact these two radionuclides have in diagnostics has been reviewed.10Table 2 highlights a few advantages of 99mTc and 68Ga as metal radionuclides.

Table 2. Advantages and disadvantages of 99mTc and 68Ga (ref. 10).

| 99mTc | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Availability | Most widely used radioisotope for SPECT imaging and dominates approximately 70–80% of diagnostic imaging | Global shortage may become an issue in the years to come due to the closure of nuclear reactors |

| Nuclear properties | 1. Ideal nuclear properties of the isotope 2. Monochromatic 140 keV γ-ray with 89% abundance, energy optimal for imaging with commercial gamma cameras 3. Absence of high energy beta emission allows the injection of activities (≈1.11 GBq (30 mCi)) with low radiation exposure to the patient 4. Half-life of six hours is long enough for studying metabolic processes and short enough to add to the radiation burden | |

| Chemistry and radiolabeling | 1. Versatile chemistry due to its multi-oxidation states which allows labeling with a wide variety of chelators of desired properties 2. Possible to achieve high specific activities | Complex chemistry which can get affected by the reaction conditions and co-ligands |

| 68Ga | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Availability | An attractive alternative to 99mTc | Present generators require more modification to address issues related to: (a) High eluate volume resulting in low concentration of 68Ga; and (b) Contamination with 68Ge and other metal ions resulting in low labeling yields and specific activities |

| Nuclear properties | Versatility for use as a SPECT tracer using 67Ga (cyclotron produced) and as a PET tracer using 68Ga (generator produced) | Higher positron energy than that of 18-F can potentially lead to lower spatial resolution |

| 67Ga: | ||

| Readily available | ||

| Reasonable cost | ||

| Long half-life of 78.3 h allows shipment over long distances | ||

| 68Ga: | ||

| Cost-effective, | ||

| Half-life of 67.71 min allows sufficient time for labeling and imaging | ||

| Chemistry and radiolabeling | Shares similar coordination chemistry to 90Y and 177Lu and thus the complexes can have versatility as therapeutic and diagnostic agents | 1. Hydrolysis and formation of insoluble gallium hydroxide during radiopharmaceuticals preparation requires proper purification 2. Ligand exchange studies using transferring need to be performed to establish biological stability. This is because of the similar coordination chemistry of gallium (+3) and iron |

This review discusses the design and development of 99mTc- and 68Ga-radiolabelled probes for neuroreceptor imaging. The review is divided into three sections. Briefly, Section 1 describes the design considerations for a general radiotracer and narrows down to the requirements of a tracer required for receptor targeting in the brain. This is followed by a comprehensive literature search of the radioligands in Section 2. The ligands are covered as per the receptors and also ligands reported for MRI which can serve as leads are mentioned. Section 3 describes outcomes from the research studies discussed in Section 2 and gives an insight into future research that can be undertaken in the field.

Section 1: design considerations

Dedicated reviews covering different aspects in the development of radiotracers for brain imaging have already been reported (Table 3). The following section summarizes (1) the general design aspects of radiotracers, (2) fine tuning of the design for brain targeting and for neuroreceptor imaging, and (3) the challenges involved in the design of metallic radiotracers for neuroreceptors.

Table 3. Reviews of the design of brain radiotracers.

| 2014: Development of F-18-labeled radiotracers for neuroreceptor imaging with positron emission tomography11 Introduction to the principles of PET Detailed discussion on the strategy for radiotracer development: target selection identification of lead structures, target characterization, in vitro screening, physicochemical characterization, labeling precursors, metabolism of radiotracers in animals, proof of target in animals, proof-of-concept in humans |

| 2014: Radioligand development for molecular imaging of the central nervous system with positron emission tomography12 The role of PET imaging in CNS drug development Target selection, radioligand discovery (in vitro and preclinical evaluation), radiochemistry, manufacturing PET radiopharmaceuticals, clinical implementation and validation |

1. Designing radiotracers

The general requirements in the design and development for a radiotracer are:10,12–14

1. Target selection: a validated target is required which has a mechanistic role in the prognosis of a disease. The target should be present in accessible amounts for a good signal-to-noise ratio.

2. Organic synthesis: easy synthesis with high purity.

3. Radiochemistry: high specific activity when radiolabelled and quick to label without loss of affinity.

4. Pharmacological properties: the radiotracer should have fast clearance from the blood, rapid localization to the target and fast washout from non-target tissues. The metabolic stability of the radiotracer should be well established to avoid toxicity and non-specific signals of radio metabolites. If metabolites are generated at all, these should be preferably polar, measurable or unlabeled, and should not interfere with the radioligand's binding kinetics.

5. Pharmacodynamics: the radiotracer should be able to be modeled to quantify the receptor density based on the kinetic information obtained by imaging. The radioligand binding must equilibrate within the imaging time frame and in 3–5 half-lives of the radiotracer.

6. Imaging requirements: the radiotracer should bind to the target with high affinity and have a high target to non-target ratio.

7. Sterile preparation: it should be safe to use.

2. Designing radiotracers for the CNS

The design for a CNS radioligand requires further fine-tuning of parameters.

1. Blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetration

First and foremost, the tracer should be able to cross the intact BBB. Making drugs capable of crossing the BBB has been a major challenge for medicinal chemists. How challenging it can be to make a drug cross the BBB can be assessed from the fact that only 5% of drugs of the CMC (Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry) database cross the BBB.15 The BBB allows the migration of small lipophilic molecules through a variety of mechanisms – passive diffusion, active diffusion and receptor-mediated. Some empirical rules exist; however, a large number of exceptions also exist as well. The rules of thumb are: molecular mass less than 600 Da, polar surface area less than 90Å2, no charge and moderate lipophilicity at pH 7.4 between 1 and 3. Lipophilicity also has a cutoff. More lipophilic compounds will be effluxed out through efflux pumps like the Pgp and other ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family efflux pumps. Further, the more lipophilic a compound, the higher are its chances of binding with the plasma protein and membranes. This nonspecific binding will lead to a low target to non-target ratio. Once bound to the plasma proteins, the BBB permeation will decrease as the free form of the compound will be no longer available to cross the BBB. In addition, lipophilic compounds can also be absorbed by syringes; hence, administration of the compounds will be difficult.

2. Dissociation constant

The second consideration is the dissociation constant of the radioligand. The binding potential of the radioligand is defined as the ratio of the target's concentration to its dissociation constant and this ratio should be approximately 10 or greater in order to provide a reliable quantifiable signal. Neuroreceptors are present in very low concentrations. At times, in the brain, the concentration is only one-tenth of the total concentration. Thus, tracers with very high affinities having dissociation constants in nanomolar concentrations are preferred.

3. Selectivity

Neuroreceptors share sequence similarities. Hence, the selectivity of the radioligand has to be established. The radioligand should have 20–100 fold less affinity for any other binding site with the same expression level.

3. Designing metallic radiotracers

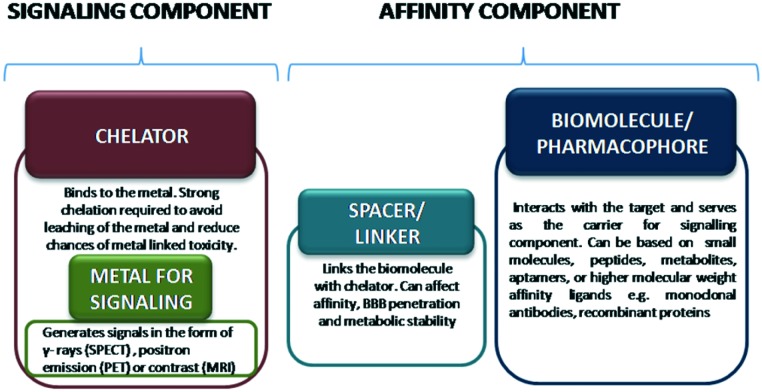

Typically, the radioligand which has to be radiolabelled with a metal consists of three parts: (a) the biomolecules, (b) the chelate system and (c) the linker (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Design components of a metallic radiotracer.

Development of metallic radiotracers becomes tricky because it involves the introduction of a chelator system which along with metal binding can cause alterations in drug permeability and target affinity thereby affecting BBB penetration and efficacy.

In the past, metallic radiotracers viz., 99mTc-DTPA (pentetate) or [99mTc]-pertechnetate have been used for brain imaging. Being hydrophilic, these were used for imaging in a compromised BBB. Diseases may not be always accompanied by BBB disruption especially in the early stages. In order to image when an intact BBB is present, lipophilic molecules and complexes have been designed that can cross the intact BBB. The transport across the membrane can be either passive diffusion or facilitated transport.7

A comprehensive literature search of the reported metallic radioligands follows. The ligands are discussed as per the neuroreceptors the ligands target.

Section 2: comprehensive literature for the 99mTc and 68Ga ligands

Dopaminergic pathway

DAT

Dopamine transporter (DAT) has been one of the early targets for the design of radiotracers. Repeated attempts to develop technetium-labeled probes were defeated by one major consideration – brain entry. The first successful technetium-labeled compound for DAT reported to cross the blood–brain barrier and accumulate in a selective target, the striatum in monkeys, was a phenyltropane analog, O-861 (Technepine (1)).16 Technepine bound with high affinity to the dopamine transporter. The radioactivity build up in the brain was fast and was detectable for 3 h.

In parallel, Meegalla et al. also labeled tropanes for DAT imaging. Of the four analogs they labeled, 99mTc-TRODAT(2),[2-[[2-[[[3-(4-chlorophenyl)-8-methyl-8-azabicyclo[3.2.1]oct-2-yl]methyl](2-mercaptoethyl)amino]ethyl]amino]ethanethiolato(3-)-N2,N2′,S2,S2′]oxo-[1R-(exo–exo)]-[99mTc]technetium, showed promising results. The conclusions18–20 of various studies for 99mTc-TRODAT are summarized in Table 4. In 1996, the radioligand was first used for imaging of DAT in humans.2199mTc-TRODAT has been extensively used in imaging. Google search shows around 700 hits for 99mTc-TRODAT since 2000 and has been reported for imaging in Parkinson's disease, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia and many other neuro-disorders, apart from its use in dual-isotope imaging with PET–SPECT and SPECT–SPECT combination. Table 5 gives a comprehensive list of metal based ligands for DAT.

Table 4. Some salient features of 99mTc-TRODAT.

| Physicochemical parameters:19 | |

| Partition coefficient in octanol and buffer | 227 (pH 7.0) |

| Pharmacological parameters: | |

| Animal: rat: mode of administration: i.v. | |

| Highest initial brain uptake19 | 0.4%, 2 min |

| Striatal/cerebellar (ST/CB) ratio19 | 2.66 at 60 min |

| Effect of pretreatment of rats with a competing DAT ligand27 | |

| β-CIT or RTI-55 (i.v., 1 mg kg–1) | Blocked the specific striatal uptake and the regional brain uptake reduced to ST/CB = 1.2 |

| Haloperidol (i.v., 1 mg kg–1) | Specific striatal uptake not affected |

| In vivo stability18 | Good: more than 95% of the original compound recovered from the striatal homogenates at 60 min |

| Effect of rat sex18 | Similar and comparable organ distribution patterns and regional brain uptakes obtained for male and female rats |

| Ex vivo autoradiography18 | Confirmed the high uptake and retention in the striatal region |

| In vitro binding studies18 | |

| TRODAT-1 as a free ligand | K i – 9.7 nM |

| Re-TRODAT as a non-radioactive rhenium derivative | K i – 14.1 nM |

| Behavioural studies18 | No effect on locomotor activity |

| Animal: nonhuman primates20 | |

| Basal ganglia to occipital lobe contrast ratios | 3.5 : 1 |

Table 5. Selected examples for metal-based DAT ligands.

| Structure |

1

1

|

2

2

|

3

3

|

4

4

|

| Tc-oxo core with a dithiol–amine–amide tetradendate chelator | Tc-oxo core with a bis aminoethane thiol tetradendate chelator | Tc-oxo core with a dithiol–amine–amide tetradendate chelator | Tc-oxo core with a dithiol–amine–amide tetradendate chelator | |

| NameRef | Technepine (O-861)16 | TRODAT17–21 | FLUORATEC (O1505)22 | 99mTc-BAT-tropane ester23 |

| K i/IC50 | 5.99 ± 0.81 nM | 14.1 nM | 2.05 nM | n.r. |

| Log P | n.r | 2.48–2.35 | n.r | 1.64 |

| Brain uptake | Absolute uptake in the brain ∼ low5(f) | 0.4%, 2 min in rats | n.r | No brain uptake |

| Selectivity ratios | 5HTT/DAT = 21 and NET/DAT of 6730 | 5HTT/DAT ≈ 25 (ref. 18) | SERT/DAT = 242 | n.r. |

| Structure |

5

5

|

6

6

|

7

7

|

8

8

|

| Tc-oxo core with a tetradendate chelator “N2S2 integrate” tropane integrated with a biovector | Dithioether/carbonyl complex | 99mTc-tricarbonyl | 99mTc-tricarbonyl | |

| NameRef | Integrated tropane BAT24 | TROTEC25 | 99mTc-tricarbonyl tropane-PAA26 | 99mTc(CO)3(Tropyn)I27 |

| K i/IC50 | n.r. | Receptor affinity state dependent i. DAT high affinity 0.146 ± 0.042 nM ii. DAT low affinity 20.3 ± 16.1 nM | n.r. | n.r. |

| Log P | n.r. | n.r. | ≈2.1 | n.r. |

| Brain uptake | 0.24% of I.D. at 1 h p.i. in rats | n.r. | No brain uptake | (Mice) 0.60 ± 0.12% ID, 2 min p.i. (Rat) 0.49 ± 0.0.09% ID, 2 min p.i. |

Possible leads

Recently, macrocycle (DO3A) containing ligands have been reported for in vitro DAT imaging. Two complexes were reported based on tropane (–)-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-chlorophenyl) tropane (β-CCT, or RTI-31(9)) and arecoline (10). The synthesis was carried out by the addition reaction between Grignard nucleophiles and the α,β-unsaturated methyl esters of ecgonidine and arecoline. The reaction proceeded with the formation of a cyclic intermediate which regioselectively produced the 1,4-conjugate. A 2-amino-ethanethiol linker was appended to the conjugate and coupled to maleimide-containing DO3A. Binding affinities were inferred using the relaxivity data. Since for the arecoline complex no appreciable change in relaxivity could be observed, it was inferred that the arecoline complex did not bind with DAT. The β-CCT complex showed appreciable DAT affinity (Kd 303 ± 138 nM) which is comparable to the affinity of natural cocaine. Though the authors have evaluated gadolinium-loaded complexes for the purpose of MRI, they agree that MRI studies of in vivo DAT may not be successful because of the inherent insensitivity of magnetic resonance techniques and the nanomolar concentrations of DAT in vivo. Also, BBB permeation has not been reported. However, these compounds can be readily prepared via an analogous method and employed for in vivo SPECT and PET imaging studies using metallic radionuclides and further validated.28

Dopamine receptors

Spiperone derivatives were labeled with 99mTc using dithiocarbamate (SPDC)29 and bis-aminoethanethiols (BAT)30 as chelators. The synthesis of SPDC involved conjugation with carbon disulfide in ethanol in the presence of a base. BAT derivatives were synthesized using the Strecker reaction. In both studies,29,30 biodistribution studies following i.p. injection in rats showed low uptake of radioactivity in the brain (SPDC brain uptake 0.05% of the dose; BAT derivatives (11, 12) brain uptake 0.07–0.09% ID g–1). Sethi et al.31 reported the design, synthesis and biological evaluation of the 99mTc-labeled DTPA-bis-(1-phenyl-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4,5]decan-4-one) (13). Two units of bis-spiperone were conjugated with DTPA and labeled with 99mTc. The Kd for the 99mTc-DTPA-bis conjugate was 6.26 nM. The competitive binding assay showed 1000 fold more selectivity for D2 as compared to D1. Thus, the authors were able to demonstrate the retention of activity of spiperone even after conjugation with the chelate.

Possible leads

Gadolinium-loaded spiperone compounds have been reported for MRI imaging of dopamine. The group of Cohen et al. reported the synthesis of DO3A bound spiperone ligands32,33 and evaluated their relaxivity and binding affinity. The structures (14–16) show the impact on the affinity of the molecule when the substitutions are carried out at different positions.

Recently, DO3A was chelated with two units of spiperone (17). The main highlight of this report was (a) a bivalent ligand approach and (b) the use of bio-orthogonal reaction-click chemistry to link the two units. Though quantitation of the ligand entering the brain was not reported, an effective contrast was obtained.34

Serotonergic pathways

Serotonin transporters

6-Nitroquipazine is the pharmacophore of choice as it displays high in vitro affinity and in vivo selectivity towards 5HT. 99mTc-labelled 6-nitroquipazine was synthesised as [N-[2-(3-(4-(6-nitroquinolin-2-yl)piperazin-1-yl)propyl)(2-mercaptoethyl)amino]-acetyl-2-aminoethanethiolato] [99mTc]technetium(v)oxide (99mTc-MAMA-3-PQ (18)) and evaluated. The ligand had a radiochemical yield of 80%, high initial brain uptake and relatively fast washout in mice (0.09% ID per organ at 60 min p.i.). It accumulated in SERT-rich regions with high specific binding ratios at 60 min p.i. (T/CB ≈ 2.9, HT/CB ≈ 2.6). However, these encouraging results need further validation through challenge experiments and in vitro competitive binding studies.35

There are some reports wherein 99mTc-TRODAT has been used to image 5HT in regions of the brain with low DAT receptors such as the mid brain and hypothalamus area. Further, pre-treatment with methylphenidate reduces the specific binding of [99mTc]TRODAT-1 to DAT sites without affecting the binding to SERT sites.36

Serotonin receptors

5HT1A

Serotonin isoforms have been extensively targeted using molecular imaging methods. Of these, 5HT1A has been the most widely focused neuroreceptor, probably because it happens to be the best characterized. IAEA reports summarize the development of 5HT1A targeting ligands using 99mTc. The ligands developed were derivatives of WAY-100635, a well-known antagonist of 5HT1A and reported as an effective PET tracer. The development of technetium-labeled ligands for serotonin receptors was reported as early as 1999. WAY derivatives have been radiolabelled using technetium through different strategies. The changes were tested by varying the linker lengths, nature of linkers, chelating systems, and technetium cores. A comprehensive list of the ligands is reported.37 A few other examples are presented here in Table 6.

Table 6. A few examples of ligands for 5HT1A.

(19)38 (19)38

|

IC50 ≈ 1.29 |

| Brain uptake (rats) = 0.56% ± 0.07% ID, 2.5 min p.i. | |

| Selectivity | |

| 5-HT1A/5-HT2A 700 | |

| 5-HT1A/D2 150 | |

n = 2: R = C6H5, 4-CH3OC6H4, n = 3: R = C6H5, 4-CH3OC6H4, 4-CH3C6H4, 4-C2H5C6H4, 4-n-C4H9C6H4, 4-ClC6H4, 3BrC6H4, C6H5CH2CH2, 4-t-C4H9C6H4CH2 (20)39

n = 2: R = C6H5, 4-CH3OC6H4, n = 3: R = C6H5, 4-CH3OC6H4, 4-CH3C6H4, 4-C2H5C6H4, 4-n-C4H9C6H4, 4-ClC6H4, 3BrC6H4, C6H5CH2CH2, 4-t-C4H9C6H4CH2 (20)39

|

Brain uptake (rats) = 0.24–1.31% ID at 2 min p.i. |

| Max. uptake for n = 2. | |

(21)40 (21)40

|

n = 4: log PO/W = 1.9 IC50 ≈ 0.29 Brain uptake (rats) = 0.23% ID g–1, 5 min p.i. n = 5: IC50 ≈ 0.62 Brain uptake (rats) = 0.32% ID g–1, 5 min p.i. n = 6: log PO/W = 2.3 IC50 ≈ 4.5 Brain uptake (rats) = 0.18% ID g–1, 5 min p.i. |

(22)41 (22)41

|

R = H, (IC = 8 nM) log Poct/buffer = 0.78 R = CH3, (IC = 54 nM) log Poct/buffer = 1.06 Brain uptake ∼ poor |

(23)42 (23)42

|

Brain uptake ∼ 0.34% ID g–1 Moderate IC50 = 13 ± 0.89% |

Our group has also contributed to the development of metal-based radioligands for imaging of 5HT1A. The work consists of (1) development of agonist-based ligands, (2) ligands with multimeric interactions and (3) ligand loaded with 68Ga for PET.

A serotonin agonist was derivatised as a dithiocarbamate and validated as a 5HT1A receptor imaging agent. Docking studies were performed for the ligand SER-DTC using a 5-HT1A homology model to understand and compare the interactions between the ligand (SER-DTC, (24)) and serotonin (SER) with the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor. The neuroimaging efficacy of the technetium-labeled ligand 99mTc-SERDTC was evaluated based on the biodistribution profile of the radiolabelled compound, in vivo and in vitro stability and scintigraphy results. The peak brain uptake value was 1.10 ± 0.02% ID g–1, 5 min p.i.43

Using the bivalent ligand approach, a homodimeric 5-HT1A receptor ligand was synthesized by appending two identical pharmacophores, 1-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazine, through DTPA (25). A high radiolabeling yield (>95%) and radiochemical purity (>98%) were obtained. The complex was found to be 1000 times more selective for 5-HT1A than for 5-HT2A receptors. The Kd value was in the picomolar range. The Hill coefficients, which were between 1.9 and 2.3, indicated the involvement of both units for cooperative binding. In vivo organ distribution and dynamic gamma scintigraphy showed the uptake in the brain as early as 2 min with maximum uptake at 10 min (2.07 ± 0.76% ID g–1 in a mouse brain and 2.81% ID g–1 in a rat brain). Further, there was high hippocampus and cerebral cortex uptake because these are 5-HT1A receptor-rich regions.44

DO3A has been conjugated with methoxyphenyl piperazine (26). The distance between the pharmacophore and the macrocycle corresponds to a 7 atom spacer. The complex has been radiolabelled with 68Ga for PET, Gd3+ for MRI and Eu3+ for optical studies. Theoretical studies support good binding affinity for the receptor. The brain uptake in rat was 3.91% ID g–1 at 30 min p.i.45

5HT2A

For the assessment of 5HT2A receptors, 3 + 1′′ type mixed-ligand complexes were synthesized using ketanserin fragments and a SNS/S donor set. A series of compounds were generated having either the quinazolinedione part or the (4-fluorobenzoyl)piperidine portion of ketanserin (27).46

Muscarinic cholinergic receptors

In 1994, the neuromuscular blocking agent benzovesamicol was conjugated to diaminodithiol and radiolabeled with 99mTc (28).47 Biodistribution of the complex in CD-l mice showed very little uptake and no regional selectivity in the mouse brain.

The receptors were also targeted using quinuclidinylcarboxymethyl radiolabelled with 99mTc to form an isomeric complex 99mTc-[2,5,5,9-tetramethyl-4,7-diaza-7-(3′-(R)-quinuclidinylcarboxymethyl)-2,9-decanedithiolato oxo]. High KD (1.9 ± 0.5 μM and 4.5 + 0.5 μM) values were obtained and 0.3% ID accumulated in the brain at 5 min p.i.48

Benzodiazepine receptors

Desmethyldiazepam derivatives were labeled with 99mTc through the technetium nitride core using [99mTc(N)-(PXP)]2+ (29) and evaluated. IC50 > 1 μM was obtained for the analogs.49

Amyloids

Though amyloids do not qualify as neuroreceptors, imaging amyloids require the ligand to cross the BBB. Initial work concentrated on large molecules based on Congo red and chrysamine G derivatives. Reports exist wherein metal-labeled small neutral molecules have been demonstrated to cross the BBB and shown an affinity for the plaques. Both 99mTc and 68Ga ligands have been synthesized and validated.

Curcuminoids50 and chalcones51 have been used for targeting amyloid plaques. The curcuminoid derivatives (30 [68Ga (CUR)2]+, [68Ga (DAC)2]+, [68Ga (bDHC)2]+) were charged, and the brain entry was not commented. The chalcone derivatives (31)51 were neutral and showed a brain uptake of 1.24 ± 0.31% ID g–1 at 2 min and 0.36 ± 0.06% ID g–1 at 30 min p.i.

A review52 is already published covering technetium-labeled ligands for β-amyloid plaques. The succeeding examples after 2011 have been included here (Table 7). A variety of amyloid binding motifs, viz., phenyl benzoxazole (32),53 pyridyl benzofuran (33),54 2-arylbenzothiazole (34,543555), dibenzylideneacetone (36),56 and chalcone (37–39),57 have been conjugated with 99mTc to develop as 99mTc-labelled SPECT probes.

Table 7. Selected examples of 99mTc-probes for amyloid imaging.

(32)53 (32)53

|

X = CH2, Ki = 11.1 nM X = C = 0, Ki = 14.3 nM Brain uptake (mice) 0.81% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. |

[99mTc]BAT-Bp-2 (33)54 [99mTc]BAT-Bp-2 (33)54

|

R = –NH2, Ki = 149.6 Nm Brain uptake (mice) 1.59% ID g–1 at 2 min p.i. R = –NHMe, Ki = 32.8 nM Brain uptake (mice) 1.80% ID g–1 at 2 min p.i. R = –NMe2, Ki = 13.6 nM Brain uptake (mice) 1.41% ID g–1 at 2 min p.i. |

(34)55 (34)55 (General formula) (General formula) |

n = 3, Ki = 8.8 ± 1.8 nM Brain uptake (mice) (i) 2.11% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. (ii) 0.62% ID g–1 at 60 min Brain uptake (Rhesus monkey) 0.78–1.23% ID from 0–10 min p.i. |

(35)56 (35)56

|

n = 3, R = –H, Ki ≈ 142 nM Brain uptake (mice) 0.50% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. n = 3, R = –CH3, Ki ≈ 75.8 n. Brain uptake (mice) 0.36% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. n = 5, R = –H, Ki ≈ 64.1 n. Brain uptake (mice) 0.26% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. n = 5, R = –CH3, Ki ≈ 24.0 n. Brain uptake (mice) –0.37% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. Log D = 3.55–3.17 |

(36)57 (36)57

|

n = 2, X = CH2; Ki = 24.7 nM, log D = 3.36, brain uptake (mice) ≈ 0.49% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. X = CO; Ki = 120.9 nM, log D = 3.52, brain uptake (mice) ≈ 0.48% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. n = 4, X = CH2; Ki 13.6 nM, log D ≈ 3.17, brain uptake (mice) ≈ 0.47% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. X = CO; Ki 59.1 nM, log D ≈ 3.57, brain uptake (mice) ≈ 0.31% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. |

(37)58 (37)58

|

n = 1–3 Ki ≈ 899–108 nM Brain uptake = 4.10 ± 0.38%–1.11 ± 0.34% ID g–1 |

(38) 99mTc-BAT-chalcone derivatives59 (38) 99mTc-BAT-chalcone derivatives59

|

n = 3, log P = 2.51, max. brain uptake: 99mTc-BAT-chalcone: 1.48% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. n = 5, log P = 2.73 Brain uptake (mice) 0.78% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. |

(39) 99mTc-MAMA-chalcone derivatives59 (39) 99mTc-MAMA-chalcone derivatives59

|

n = 3: log P = 1.51, brain uptake (mice) 0.62% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. n = 5: log P = 2.55, brain uptake (mice) 0.22% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. |

The studies have also arrived at certain structure–affinity relationships mentioned in Section 3.

Possible leads

Selective detection of β-amyloid fibrils was demonstrated using lanthanide-labelled probes. A luminescent dipyridophenazine ruthenium(ii) [Ru(bpy)2(dppz)]2+ complex showed strong photoluminescence in the presence of β-amyloid fibril aggregates.60

Opioid receptors

Naltrindole, a highly potent and highly selective δ-opioid receptor antagonist, was conjugated to DO3A and DOTA through the N1′-position (40). The chemistry involved reductive amination of naltrindole propionaldehyde with DO3A and coupling reactions involving aminopropyl naltrindole with the N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester of DOTA. Inspite of being appended with macrocycles, the conjugates displayed good affinity for δ-opioid receptors in vitro.61

Ligands with undefined selectivity/specificity but with data on brain entry

“3 + 1” oxo technetium mixed-ligand complexes of Gabapentin were synthesized (41).62 A good radiochemical yield of 75–80% was obtained for the two ligands. Significant initial brain uptake at 5 min p.i. and a good retention (0.6%–0.7% for complexes at 120 min) were observed in mice. However, validation of the ligand's specificity and selectivity will require in vivo imaging, receptor specificity and corresponding in vivo accumulation.

Ligands designed for specific receptors with data on brain entry not reported/not evaluated

TSPO or peripheral benzodiazepine receptors (PBR)

The antagonist imidazopyridine was derivatised as CB256 and labeled with 99mTc using fac[99mTc(CO)3 (H2O)3]+ for tumor imaging. Complex 42 was evaluated in tumor cell lines (C6 rat glioma and U87MG human glioblastoma) for uptake.63

β2-adrenoceptor receptors

The β2-adrenoceptor receptor was targeted using europium-labeled pindolol ligands (43).64

Section 3: Summary of the results

Designing metal radiotracers is a challenge and limited success has been achieved in comparison with 11C, 18F or 123I radiotracers. What follows from the studies above is that metal chelators are bulky molecules and can affect the bio-affinity of the ligands. The primary challenge is to make the radioligand cross the BBB. The penetrating ability of the radioligand can be enhanced by modulating the lipophilicity, charge, and size of the molecule. Neutral lipophilic ligands are preferred. Charged ligands for amyloids like [68Ga (CUR)2]+, [68Ga (DAC)2]+, [68Ga (bDHC)2]+ do not reach the brain. Efforts to increase the lipophilicity can be made through choosing a lipophilic biomolecule, linker or even the chelate and the core of the radionuclide. Examples wherein a balance in lipophilicity is brought about by designing linkers and pharmacophores appropriately include the development of DTPA-conjugated bis spiperone,31 MPBA,44 and chalcone51 (Table 8).

Table 8. Lipophilicity modulation for DTPA-based radiotracers.

| Pharmacophore |

Ligand |

Metal loaded chelate |

|||

| CH2 | 3.48 ± 0.11 | DTCH2 | 0.96 ± 0.06 | 68Ga-DTCH2 | 1.58 |

| DTPA-bis(MPBA) | –1.04 | 99mTc-DTPA bis(MPBA) | 2.445 | ||

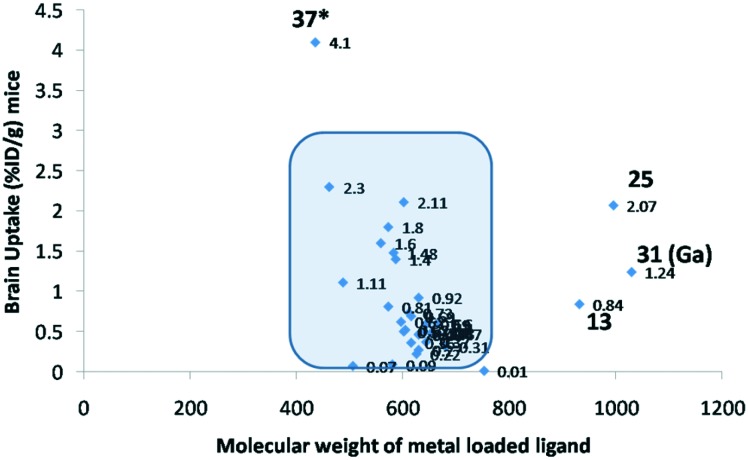

These examples are also outliers for the molecular weight rule; still, the ligands were able to cross the BBB (Fig. 2). We tried to establish a correlation between brain uptake and the molecular weight. The molecular weight was calculated for the complex along with the metal. However, no regular pattern could be established. Among the reported ligands, majority of compounds had the molecular weight in the range 400–600 Da. Compound 37* is based on [Cp99mTc-(CO)3] and has π conjugation.

Fig. 2. Correlation graph.

Linkers can also affect BBB permeation and affinity. In the work of Jia et al., (35)56 the amide bond in the linker linking the lipophilic piano stool chelator [Cp99mTc-(CO)3] with the 2-phenylbenzothiazole binding motif was considered to have a negative effect on BBB permeation. They hypothesized that the amide bond gets involved in the formation of H-bonding thereby lowering the brain uptake. Using [Cp99mTc-(CO)3] and chalcones conjugated to each other through the integral approach and having extended π-conjugation, Li et al. (37)58 were able to show that the length of conjugation did have an effect on brain penetration. A shorter chain complex was able to achieve the highest brain penetration.

As reported by Zhang et al. in their work for amyloid imaging, longer alkyl linkers increased the binding affinity. As they varied the linker n = 3–5 in the structure (34), an increase in affinity as a general trend was reported, with n = 5 showing maximum or near-maximum affinity in all combinations of –X and –R.

In the work of Ono et al. (38–39)59 for developing tracers for amyloid, chalcone was conjugated with chelators with varying linkers. They deduced that the length of the alkyl chain between 99mTc complexes and the chalcone backbone played a significant role in the binding of Aβ(1–42) aggregates with complexes n = 5 ranked higher in binding affinity in comparison with those with n = 3. However, the maximum uptake was found for 99mTc-BAT-chalcone having n = 3. Using spiperone for dopamine imaging, Cohen et al. demonstrated that the hydrophobic C11 spacer has higher binding affinity than the hydrophilic tetraethylene glycol spacer (14–16). In the case of 5HT1A receptors as well, the length of the linkers was reported to play a crucial role. As the linker length increased, the affinity decreased in 20.40 Ethylene chain spacers had lower IC50 (20–22 nM) compared to those with a propylene chain (IC50: 6.0–5.8 nM). Similarly, Papagiannopoulou et al. (20)39 reported that the length of the alkyl chain connecting the –Npiperazine and chelate –N was also crucial. Complexes with an ethylene chain had IC50 = 20 and 22 nM and complexes with a propylene chain had IC50 = 6.0 and 5.8 nM. Butylene and pentylene linkers are expected to have better IC50. The effect of conjugation on affinity was reported by Li et al. (37)58 wherein a longer conjugated system had a better binding affinity.

The effect of chelators has been studied by Ono et al. (38–39), wherein 99mTc-BAT and 99mTc-MAMA complexes were evaluated. The ligands (MAMA and BAT) did not affect the affinity; however, the BAT derivative had a better brain uptake.59

SAR studies may help in deciding the site of modification for pharmacophores. For example, spiperone is a well-established pharmacophore for dopamine targeting. It can be modified at different sites and has been conjugated using only the spiro part, the fluoro part and spiperone as a whole. Studies have pointed out that modification at amide N does not interfere with the binding properties.29 Cohen et al. pointed out that if the carbonyl group of the spiperone is changed to an etheric moiety as in AMI 193 or spiramide, the modification resulted in a much lower affinity for the dopamine receptors. For targeting dopamine using 13, the spiro part was sufficient to have the affinity for dopamine. When conjugated with DO3A in (17), the “spiro” part of the spiperone was not found to be as effective. Also, it was pointed out that binding of a large chemical moiety through the N3 position of the spiperone did not reduce the binding affinity to the dopamine receptors. Thus, the N3 position may be the best position to modify the spiperone moiety without compromising the binding affinity to the receptors.

Other factors affecting brain targeting

Mode of administration

Authors29,50 have also attributed low brain penetration to the route of administration. Complexes administered intraperitoneally are absorbed slowly in comparison with those administered intravenously and are susceptible to first pass hepatic metabolism before reaching the systemic circulation.

Interspecies dependence

The SPET study of 21 (ref. 40) in cynomolgus monkeys showed hardly any brain uptake even though the compound had a brain uptake of ≈0.41% ID, 5 min p.i. in rats. Similarly, for 34,55 brain uptake in mice was 2.11% ID g–1, 2 min p.i. whereas in Rhesus monkeys, the uptake was in the range 0.78–1.23% ID. These studies indicate strong species dependence.

Effect of receptors

Lastly, the effect of receptors cannot be ruled out. The inherent characteristics of receptors further complicate the entire process of designing any ligand (whether metallic or non-metallic) targeting them. According to the “occupancy model”, the uptake/retention of a tracer at the site of its receptor will be inversely related to the local concentration of the competing neurotransmitter. However, the status of the receptor viz., availability due to up- or down-regulation, internalization, altered affinity states, etc., may also change with the stimulus leading to the change in the neurotransmitter concentration. The status of the receptor will affect the uptake of the tracer. Thus, the receptor, radioligand, neurotransmitter and stimulus must be fully understood before such determinations can be made routinely. Factors that contribute are:65

• Structural heterogeneity mostly due to isoforms and the existence of oligomeric/monomeric states;

• Functional heterogeneity due to the presence of an agonist;

• Heterologous and homologous desensitization; and

• Supersensitization especially in therapeutically managed subjects.

Future directions

Based on previous experiences, future work in the development of metallic probes for neuroreceptors will concentrate on:

1. Structure–affinity relationship (SAR) studies which focus on the effect of modification and introduction of chelates on the biologically active molecule can help in initial screening. Linkers play a significant role in affinity and brain uptake as highlighted in Section 3. Modeling and simulation studies can contribute to predicting an effective linker.

2. Synthesis of stable and lipophilic chelates will have an impact on the coordination of metal radionuclides as well as brain entry. This can be achieved by synthesizing novel chelates or by modifying existing chelates using lipophilic moieties.66,67

3. Multimodality probes. With the advent of PET-MR imaging, probes capable of being loaded with two metals capable of generating PET/SPECT and MRI/optical signals will have an edge over probes with single modality.

4. The studies on radiotracers that have been included in this review have focussed on the evaluation of their binding affinity and brain penetration. However, the in vivo data will have to be supplemented further with rodent studies as discussed in Section 3.

5. Quantitative measurements of receptors using the radiotracers need to be optimised to have better insights into the receptor density distribution.

Conclusion

This review discusses the development of metal-labeled radiotracers for neuroreceptor imaging. In the routine, the metal-based radionuclides (99mTc and 68Ga) can be more practical for use in clinics owing to their easy availability through generators compared to cyclotron produced radionuclides. In the past 35 years, progress has been made in the development of targeted metal complexes. However, the immediate impact of 11C, 18F and 131I radiotracers cannot be matched by 99mTc or 68Ga probes. The main obstacles in the successful development of metal-labeled radiotracers pertain to (a) the lack of conceptual knowledge in the design and (b) the lack of in vivo data and correlation. The introduction of metal radionuclides requires attachment of chelating systems which provide thermodynamically and kinetically stable complexes. The bulky chelating systems along with linkers can affect the bio-affinity and targeting capability of the targeting moiety. For CNS tracers, the effect on BBB penetration also needs to be considered. Research on effective metal-labeled radiotracers for neuroreceptors is ongoing and needs to be in line with the future needs of multi-imaging and quantitative requirements.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Director of INMAS for providing the necessary facilities.

Biographies

S. Chaturvedi

Dr S. Chaturvedi was born in 1979 in New Delhi, India. She obtained her Bachelor's degree (Chemistry) from St. Stephen's College, Delhi in 2000 and her Master's degree (Chemistry) from the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi in 2002. She was appointed as a Scientist at INMAS, Delhi in 2004. During her tenure, she obtained her PhD in Chemistry from Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi. Her research group focuses on the design and development of targeted radiopharmaceuticals. She has been a co-investigator of several research projects, related to onco-imaging, neuro-imaging, and infection imaging.

A. Kaul

Dr A. Kaul was born in 1979 in Srinagar, India. After completing her Bachelor's degree in Pharmacy at Mumbai University in 2001, she joined INMAS as a Technical Officer. She completed her PhD (Life Sciences) at Bharathiar University, Coimbatore, India. She is a trained radio pharmacist with vast experience in radiolabeling small molecules and nanoparticles. Her research interests include radiochemistry and preclinical evaluation of radiopharmaceuticals.

Puja P. Hazari

Dr Puja P. Hazari was born in 1979 in New Delhi. She is currently working as a Biomedical Scientist at INMAS. She completed her Master's degree and PhD in Biomedical Sciences at Delhi University, India in 2006. As a Scientist, she has taken a keen interest in the development of radiopharmaceuticals for SPECT and PET imaging and successfully translated basic research into clinics. She has demonstrated expertise in the development of a new PET radiolabeling methodology towards PET labeling of small molecules with carbon-11 and fluorine-18. She has focused on and implemented fluorine-18-based labeling techniques that can be readily extended to peptides and nucleic acids for specific targeting in neuro/onco diseases and small animal imaging.

Anil K. Mishra

Dr Anil K. Mishra was born in 1963 in India. He obtained his M.S. degree (Chemistry) in 1984 from Gorakhpur University, Gorakhpur and his Ph.D. (Chemistry) in 1988 from Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. In 1989, he moved to Université de Bourgogne, France where he worked with Prof. Guilard on macrocycle chemistry. In 1992, he joined Prof. Meares at the University of California, Davis, USA. He also served as a Scientist at INSERM, Nantes, France in the team of Prof. Chatal. In 1997, he was appointed as a Senior Scientist at INMAS, Delhi, India. His research group focuses on the development of targeted radiopharmaceuticals using different classes of molecules and applying novel chemistries and approaches.

Footnotes

†The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Chisholm D., Saxena S. and Van Ommeren M., Dollars, DALYs and decisions: economic aspects of the mental health system, World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse R. N. and Collier T. L., Neuroreceptor Imaging Applications Advances and Limitations, In Molecular imaging: principles and practice, ed. R. Weissleder, B. D. Ross, A. Rehemtulla and S. S. Gambhir, PMPH-USA, 2010, pp. 1035–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Eckelman W. C., Reba R. C., Gibson R. E. J. Nucl. Med. 1979;20:350–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner Jr H. N., Burns H. D., Dannals R. F., Wong D. F., Langstrom B., Duelfer T. Science. 1983;221(4617):1264–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.6604315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung H. F., Kung M. P., Choi S. R. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2003;33(1):2–13. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2003.127296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimlott S. L., Sutherland A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40(1):149–162. doi: 10.1039/b922628c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adak S., Bhalla R., Vijaya Raj K., Mandal S., Pickett R., Luthra S. Radiochim. Acta. 2012;100:95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Articles in the Special Issue: Carbon-11 and fluorine-18 chemistry devoted to molecular probes for imaging the brain with PET: J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm., 2013, 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Ploessl K., Kung H. F. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:6683–6691M. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60430f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomä M. D., Louie A. S., Valliant J. F., Zubieta J. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:2903–2920. doi: 10.1021/cr1000755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brust P., van den Hoff J., Steinbach J. Neurosci. Bull. 2014;30(5):777–811. doi: 10.1007/s12264-014-1460-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honer M., Gobbi L., Martarello L., Comley R. A. Drug Discovery Today. 2014;19:1936–1944. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi S., Mishra A. K. Front. Med. 2016;3:5. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2016.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J. S. D., Mann J. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2014;14(2):96–112. doi: 10.2174/1871524914666141030124316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose A. K., Viswanadhan V. N., Wendoloski J. J. J. Comb. Chem. 1999;1:55–68. doi: 10.1021/cc9800071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madras B. K., Jones A. G., Mahmood A., Zimmerman R. E., Garada B., Holman B. L., Davison A., Blundell P., Meltzer P. C. Synapse. 1996;22(3):239–246. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199603)22:3<239::AID-SYN6>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meegalla S., Ploessl K., Kung M.-P., Stevenson D. A., Liable-Sands L. M., Rheingold A. L., Kung H. F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:11037–11038. [Google Scholar]

- Kung M. P., Stevenson D. A., Plössl K., Meegalla S. K., Beckwith A., Essman W. D., Mu M., Lucki I., Kung H. F. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1997;24(4):372–380. doi: 10.1007/BF00881808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meegalla S. K., Plössl K., Kung M. P., Chumpradit S., Stevenson D. A., Kushner S. A., McElgin W. T., Mozley P. D., Kung H. F. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40(1):9–17. doi: 10.1021/jm960532j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung H. F. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2001;28(5):505–508. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(01)00220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung H. F., Kim H.-J., Kung M.-P., Meegalla S. K., Plössl K., Lee H.-K. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1996;23:1527–1530. doi: 10.1007/BF01254479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer P. C., Blundell P., Zona T., Yang L., Huang H., Bonab A. A., Livni E., Fischman A., Madras B. K. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:3483–3496. doi: 10.1021/jm0301484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanbilloen H. P., Kieffer D., Cleynhens B. J., Bormans G., Mortelmans L., Verbruggen A. M. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2005;32:607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleynhens B. J., de Groot T. J., Vanbilloen H. P., Kieffer D., Mortelmans L., Bormans G. M., Verbruggen A. M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:1053–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoepping A., Reisgys M., Brust P., Seifert S., Spies H., Alberto R., Johannsen B. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:4429–4432. doi: 10.1021/jm981008a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanbilloen H. P., Rattat D., Terwinghe C. Y., Mortelmans L., Bormans G. M., Verbruggen A. M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16(2):382–386. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Zhu L., Ding S., Liu B. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2005;50(8):761–764. [Google Scholar]

- Naumiec G. R., Lincourt G., Clever J. P., McGregor M. A., Kovoor A., DeBoef B. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015;13:2537–2540. doi: 10.1039/c4ob02165g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballinger J. R., Gulenchyn K. Y., Hassan M. N. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 1989;40:547–549. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(89)90145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samnick S., Brandau W., Sciuk J., Steinsträβer A., Schober O. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1995;22:573–583. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(95)00004-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethi S. K., Varshney R., Rangaswamy S., Chadha N., Hazari P. P., Kaul A., Chuttani K., Milton M. D., Mishra A. K. RSC Adv. 2014;4:50153–50162. [Google Scholar]

- Zigelboim I., Weissberg A., Cohen Y. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:7001–7012. doi: 10.1021/jo400646k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigelboim I., Offen D., Melamed E., Panet H., Rehavi M., Cohen Y. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2007;59:323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Varshney R., Sethi S. K., Rangaswamy S., Tiwari A. K., Milton M. D., Kumaran S., Mishra A. K. New J. Chem. 2016;40:5846–5854. [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Chen X., Jia H., Ji X., Liu B. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2008;66:1804–1809. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresel S. H., Kung M.-P. T., Huang X., Plössl K., Hou C., Shiue C. Y., Karp J., Kung H. F. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1999;26:342–347. doi: 10.1007/s002590050396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- I. Pirmettis Technetium-99 m Radiopharmaceuticals In Neurology Chapter 6 In Radioisotopes, I.A.E.A. and No, R.S.,. 1: Technetium-99 m Radiopharmaceuticals: Status and Trends. 2009.

- Heimbold I., Drews A., Syhre R., Kretzschmar M., Pietzsch H.-J., Johannsen B. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2002;29:82–87. doi: 10.1007/s00259-001-0660-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papagiannopoulou D., Pirmettis I., Tsoukalas C., Nikoladou L., Drossopoulou G., Dalla C., Pelecanou M., Papadopoulou-Daifotis Z., Papadopoulos M., Chiotellis E. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2002;29(8):825–832. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00343-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews A., Pietzsch H.-J., Syhre R., Seifert S., Varnäs K., Hall H., Halldin C., Kraus W., Karlsson P., Johnsson C. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2002;29:389–398. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00296-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiotellis A., Tsoukalas C., Pelecanou M., Pirmettis I., Papadopoulos M. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2012;70:957–964. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanzadeh L., Erfani M., Sadat Ebrahimi S. E. J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm. 2012;55(10):371–376. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.3709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi S., Kaul A., Yadav N., Singh B., Mishra A. K. MedChemComm. 2013;4:1006–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Singh N., Hazari P. P., Prakash S., Chuttani K., Khurana H., Chandra H., Mishra A. K. MedChemComm. 2012;3(7):814–823. [Google Scholar]

- Hazari P. P., Prakash S., Meena V. K., Singh N., Chuttani K., Chadha N., Singh P., Kukreti S., Mishra A. K. RSC Adv. 2016;6:7288–7301. [Google Scholar]

- Johannsen B., Scheunemann M., Spies H., Brust P., Wober J., Syhre R., Pietzsch H. J. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1996;23(4):429–438. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(96)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rosario R. B., Jung Y. W., Baidoo K. E., Lever S. Z., Wieland D. M. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1994;21(2):197–203. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever S. Z., Baidoo K. E., Mahmood A., Matsumura K., Scheffel U., Wagner H. N. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1994;21(2):157–164. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(94)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschi A., Uccelli L., Duatti A., Bolzati C., Refosco F., Tisato F., Romagnoli R., Baraldi P. G., Varani K., Borea P. A. Bioconjugate Chem. 2003;14(6):1279–1288. doi: 10.1021/bc034124n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubagotti S., Croci S., Ferrari E., Iori M., Capponi P. C., Lorenzini L., Calzà L., Versari A., Asti M. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17(9):E1480. doi: 10.3390/ijms17091480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan K., Datta A., Adhikari A., Chuttani K., Singh A. K., Mishra A. K. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:7328–7337. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00941j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M., Saji H. Int. J. Mol. Imaging. 2011;2011:543267. doi: 10.1155/2011/543267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Cui M., Yu P., Li Z., Yang Y., Jia H., Liu B. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:4327–4331. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Ono M., Kimura H., Ueda M., Saji H. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:2279–2286. doi: 10.1021/jm201513c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Yu P., Yang Y., Hou Y., Peng C., Liang Z., Lu J., Chen B., Dai J., Liu B., Cui M. Bioconjugate Chem. 2016;27(10):2493–2504. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J., Cui M., Dai J., Liu B. Dalton Trans. 2015;44:6406–6415. doi: 10.1039/c5dt00023h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Cui M., Jin B., Wang X., Li Z., Yu P., Jia J., Fu H., Jia H., Liu B. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;64:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Cui M., Dai J., Wang X., Yu P., Yang Y., Jia J., Fu H., Ono M., Jia H. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:471–482. doi: 10.1021/jm3014184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M., Ikeoka R., Watanabe H., Kimura H., Fuchigami T., Haratake M., Saji H., Nakayama M. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2010;1(9):598–607. doi: 10.1021/cn100042d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook N. P., Torres V., Jain D., Martí A. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133(29):11121–11123. doi: 10.1021/ja204656r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval R. A., Allmon R. L., Lever J. R. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:2144–2156. doi: 10.1021/jm0700013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin A., Abou Zid K., Bayoumi N., Abd El-hamid M. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2009;283(1):55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. Y., Iacobazzi R. M., Perrone M., Margiotta N., Cutrignelli A., Jung J. H., Park D. D., Moon B. S., Denora N., Kim S. E., Lee B. C. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17(7):1085–1095. doi: 10.3390/ijms17071085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martikkala E., Lehmusto M., Lilja M., Rozwandowicz-Jansen A., Lunden J., Tomohiro T., Hänninen P., Petäjä-Repo U., Härmä H. Anal. Biochem. 2009;392(2):103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeff N. P. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1991;18(7):482–502. doi: 10.1007/BF00181287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S., Hazari P. P., Meena V. K., Jaswal A., Khurana H., Kukreti S., Mishra A. K. Bioconjugate Chem. 2016;27(11):2780–2790. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accardo A., Tesauro D., Aloj L., Pedone C., Morelli G. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009;253(17):2193–2213. [Google Scholar]