Abstract

Introduction

Determining the population-based scope and stability of eating, activity, and weight-related problems is critical to inform interventions. This study examines: (1) the prevalence of eating, activity, and weight-related problems likely to influence health and (2) trajectories for having at least one of these problems during the transition from adolescence to adulthood.

Methods

Project EAT I-IV (Eating and Activity in Teens and Young Adults) collected longitudinal survey data from 858 females and 597 males at four waves, approximately every 5 years, from 1998 to 2016, during the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Analyses were conducted in 2017–2018. Measures included high fast food intake (≥3 times/week), low physical activity (<150 minutes/week), unhealthy weight control, body dissatisfaction, and obesity status.

Results

Among females, the prevalence of having at least one eating, activity, or weight-related problems was 78.1% at Wave 1 (adolescence) and 82.3% at Wave 4 (adulthood); in males, the prevalence was 60.1% at Wave 1 and 69.2% at Wave 4. Of all outcomes assessed, unhealthy weight control behaviors had the highest prevalence in both genders. The stability of having at least one problem was high; 60.2% of females and 34.1% of males had at least one problematic outcome at all four waves.

Conclusions

The majority of young people have some type of eating, activity, or weight-related problem at all stages from adolescence to adulthood. Findings indicate a need for wide-reaching interventions that address a broad spectrum of eating, activity, and weight-related problems prior to and throughout this developmental period.

INTRODUCTION

The high prevalence of eating, activity, and weight-related problems during adolescence is of great public health concern, given that adolescence is a period of rapid growth and development1–6 and behavioral patterns established during this time may set the stage for adulthood.7 If eating, activity, and other weight-related problems persist from adolescence into early adulthood, then young adults, and the future generations they influence as parents, will be at increased risk for developing chronic health outcomes. To inform the content and timing of interventions, it is important to understand the scope and stability of eating, activity, and weight-related problems throughout the critical period from adolescence to adulthood.

The current study examines the prevalence and stability of a broad spectrum of eating, activity, and weight-related factors that have been linked to adverse health consequences. Examining a broad spectrum of eating, activity, and weight-related problems concurrently is valuable for learning about the scope of various problems that may be interrelated and have cumulative impacts on health. The current study thus includes indicator variables from within the domains of eating, physical activity, weight control practices, body image, and weight status that have been found to be associated with adverse health outcomes: high fast food intake,8,9 low levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA),10–12 unhealthy weight control practices,13 body dissatisfaction,14–17 and obesity.18 For example, eating fast food more than twice a week is associated with excess weight gain and increased insulin resistance 15 years later.9 Low MVPA predicts elevated all-cause mortality and cardiovascular risk 20 years later.19 Unhealthy weight control behaviors (e.g., skipping meals, taking diet pills) predict greater weight gain over time13 and low body satisfaction is linked to higher rates of binge eating, smoking,16 depression, and poor self-esteem.20

Research questions to be addressed include: (1) How does the prevalence of eating, activity, and weight-related problems change over time among females and males during the transition from adolescence to early adulthood? And (2) What are the individual trajectories over time for having at least one eating, activity, or weight-related problem in females and males? Examining prevalence over time provides information about the scope of the problems, whereas examining individual trajectories provides information about the stability or consistency of having at least one problematic outcome. Findings will inform the field’s understanding of the scope, timing, and patterns of eating, activity, and weight-related problems across key developmental periods of the life cycle and thus provide important information to guide policies, community- and school-based interventions, and clinical practices.

METHODS

Study Population and Measures

Project EAT (Eating and Activity in Teens and Young Adults) is a longitudinal study of eating, activity, and weight-related measures in young people. In 1998–1999 (Project EAT-I/Wave 1), middle school and high school students (n=4,746, mean age=14.8 [SD=1.6] years) from 31 public schools in the Minneapolis and St. Paul metropolitan area completed surveys and anthropometric measures.21,22 Follow-up mailed assessments were conducted at 5-year intervals: EAT-II/Wave 2 (n=2,516, mean age=19.4 [SD=1.7] years), EAT-III/Wave 3 (n=2,287, mean age=25.3 [SD=1.7] years), and EAT-IV/Wave 4 (n=1,830, mean age=31.0 [SD=1.6] years) to examine changes among participants as they progressed through adolescence and young adulthood.23–29 To allow for longitudinal comparisons, key variables, described in Table 1, were assessed using nearly identical survey items at each wave; any relevant differences made (e.g., to make more developmentally appropriate) are noted in the table. There were 858 females and 597 males who completed surveys at all four assessment waves. The University of Minnesota’s IRB Human Subjects Committee approved all protocols.

Table 1.

Description of Survey Measures Included on the Project EAT Wave 1–4 Surveys

| Measure | Survey items or descriptiona |

|---|---|

| High fast food intake | Frequency of fast food intake was assessed with the question: In the past week, how often did you eat something from a fast food restaurant (like McDonald’s, Burger King, etc.)? Response categories included never, 1– 2 times, 3–4 times, 5–6 times, 7 times, and more than 7 times. High intake was defined by a response of three or more times per week (test- retest agreement=86%). |

| Low moderate-to- vigorous physical activity (MVPA) | Hours of physical activity during a typical week was assessed using questions adapted from the widely used Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire.62,63 Survey items assessed individually strenuous (for example, jogging, swimming laps, basketball) and moderate activity (for example, walking quickly, easy bicycling, snowboarding) in a typical week, with several examples of each level of activity provided; item wording was identical at each wave but some of the team sport examples were dropped for surveys administered after participants had transitioned to adulthood. Response options were none, less than ½ hour, ½ hour to 2 hours, 2½ to 4 hours, 4½ to 6 hours, and 6 or more hours. Each response was assigned a midpoint value and responses were then summed to compute total weekly hours (Test-retest reliability r =0.84). Low levels of MVPA was defined as less than 150 minutes per week. |

| Use of any unhealthy weight control practices | Use of any unhealthy weight control practices was assessed with the question: Have you done any of the following things in order to lose weight or keep from gaining weight during the past year? Participants were asked to respond yes/no for each of nine specific practices (e.g., fasted, ate very little food, took diet pills, made myself vomit, used laxatives). Scores were dichotomized to none or ≥1 method (test-retest agreement=86%). |

| High body dissatisfaction | Body dissatisfaction was assessed using a modified version of the Body Shape Satisfaction Scale.64 Participants rated their satisfaction with 10 different body parts (height, weight, body shape, waist, hips, thighs, stomach, face, body build, shoulders) using a 5-point Likert scale (range: 10–50, Cronbach’s α=0.92, test-retest r =0.82). High dissatisfaction was defined by a score of <30. |

| Obesity | Self-reported height and weight were found to be highly correlated with measured values collected at Time 1 (BMI males r =0.88 and females r =0.8558; and Time 3 (BMI males r =0.95 and females r =0.9859,65; and were used to calculate BMI at each time point (test-retest height r =0.98, weight r =0.97). For Wave 1 and Wave 2, obesity status was determined based on a BMI at or above the 95th percentile for sex and age.66,67 For Wave 3 and Wave 4, obesity was defined according to current BMI guidelines for adults (overweight: BMI ≥30 kg/m2).68 |

Psychometrics for survey items were assessed at all four study waves; values included here are for Project EAT-IV. Scale psychometric properties were assessed in the full EAT-IV survey sample and estimates of item test-retest reliability were determined in a subgroup of 103 participants who completed the EAT-IV survey twice within a period of 1 to 4 weeks.

Project EAT, Project Eating and Activity in Teens and Young Adults

Statistical Analysis

To address the first research question regarding the scope of eating, activity, and weight-related problems at each of the four waves, the prevalence of having each specific outcome, any of these outcomes, and at least three of the five outcomes were examined. Tests of trends in prevalence over time (increasing or decreasing), and gender differences in time effects, were tested using t-tests from a logistic model with generalized estimating equations to control for repeated measures within an individual. To address the second research question regarding the individual trajectories of eating, activity, and weight-related problems, a five-category trajectory was defined (i.e., never, starters, mixed, stoppers, always). Frequencies were summarized for each trajectory category and gender differences in likelihood of being in each category were assessed using chi-square tests. All analyses were stratified by sex given prior findings showing different levels of specific eating, activity, and weight-related variables in males and females,11 and the importance of examining trajectories over time across sex.

The analytic sample included only participants who responded at all four study waves. Response propensity weighting30 was used in all analyses so that estimates are generalizable to the population originally sampled in Wave 1. Response propensities were estimated using a logistic regression of responder status at all four waves on a large number of predictor variables from the Wave 1 survey. Responders to all four waves differed from the Wave 1 sample in that they were more likely to be female, non-Hispanic white, and of higher SES. After response propensity weighting, the distribution of demographics and Wave 1 weight-related problems among responders did not differ from the original sample (all p-values >0.05). The unweighted sample was 71.3% white, 7.6% African American, 13.2% Asian, 3.0% Hispanic, 1.9% Native American, and 3.0% mixed (e.g., noted both African American and Native American) or other (e.g., Pacific Islander) ethnic/racial backgrounds. Educational attainment was as follows: 20.4% high school degree or less; 24.1% vocational, technical, or associate degree; 37.6% bachelor’s degree; and 17.8% graduate or professional degree. After nonresponse propensity weighting, the sample who completed surveys at all four waves matched the original sample: 46.9% white, 19.0% African American, 19.2% Asian, 5.2% Hispanic, 3.5% Native American, and 6.2% mixed or other ethic/racial backgrounds; and educational attainment was as follows: 29.1% high school degree or less; 28.0% vocational, technical or associate degree; 29.8% bachelor’s degree; and 13.1% graduate or professional degree.

Because of intermittent missing data on the five weight-related problems, the sample size varied slightly for testing trends in each outcome among complete cases. Missing data ranged from 0.9% to 4.4% for fast food, MVPA, unhealthy weight control, body dissatisfaction, and obesity; combining across all five outcomes, 7.4% of males and 9.7% of females were missing data for trends in the prevalence of having any one or any three of the weight-related problems. Females who were pregnant or breastfeeding at Waves 3 or 4 (n=198) were excluded from analyses of trends of obesity over time but remained in analyses of having any or three or more weight-related problems excluding obesity. All analyses were conducted in 2017 in SAS, version 9.4.

RESULTS

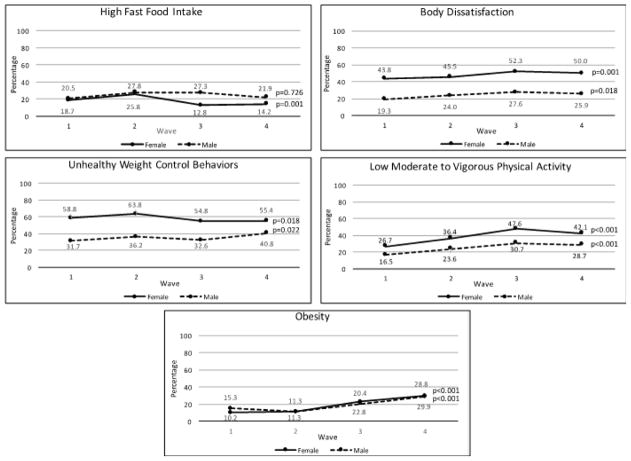

Prevalences of most eating, activity, and weight-related problems were high in adolescence and either remained high or increased during the transition to adulthood (Figure 1). For example, among females, the prevalence of low MVPA increased from 26.7% (Wave 1, adolescence) to 42.1% (Wave 4, adulthood). Among males, the prevalence of low MVPA increased from 16.5% to 28.7% during the study period. The prevalence of obesity tripled in females and nearly doubled in males from adolescence to young adulthood; nearly 30% of both females and males had BMI values in the obesity range at Wave 4. Body dissatisfaction increased in both sexes over time; at Wave 4, half (50.0%) of females and a quarter (25.9%) of males were dissatisfied. Unhealthy weight control practices were high at all waves; a slight decrease over time was found for females, while the prevalence increased among males. At Wave 4, there were 55.4% of females and 40.8% of males engaged in unhealthy weight control practices. The only potentially meaningful decrease in a problematic outcome was found for fast food intake among females, from 18.7% at Wave 1 to 14.2% at Wave 4.

Figure 1.

Trends in specific eating, activity, and weight-related problems from adolescence (Wave 1) to young adulthood (Wave 4) at 5-year intervals over a 15-year period, by gender.

Prevalences of body dissatisfaction, low MVPA, and unhealthy weight control behaviors were always higher in females than in males (t >3.00, p<0.002 at each of the four waves). Obesity prevalence did not differ by sex at any wave. Fast food intake was higher among males at Waves 3 and 4 (t= − 4.93, p<0.001 at Wave 3 and t= −2.68, p=0.007 at Wave 4). To determine if trends over time differed across sex, interactions between sex X study wave were examined. Interactions were significant for high fast food intake (t=2.53, p=0.011), with a decreased intake over time in females but not males, and for unhealthy weight control practices (t=3.23, p=0.001), with a decrease over time in females and an increase for males. Interactions were not significant for obesity (t= −1.66, p=0.097), body dissatisfaction (t=0.44, p=0.662), and low MVPA (t= −0.12, p=0.904); trends for these variables were similar over time across sex.

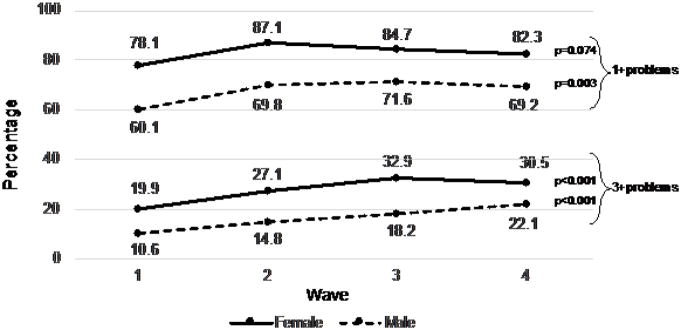

The vast majority of participants had at least one eating, activity, or weight-related problem at each study wave (Figure 2). Among females, prevalences ranged from 78.1% (Wave 1, adolescence) to 82.3% (Wave 4, adulthood; t=1.79, p=0.074). Among males, prevalences ranged from 60.1% at Wave 1 to 69.2% at Wave 4 (t=2.96, p=0.003). The prevalence of having at least one problem was significantly higher among females than males at each wave (t>3.00, p<0.001 at each wave). Interactions between sex X study wave were not statistically significant, indicating that trends over time for having at least one problematic outcome did not significantly differ across sex.

Figure 2.

Trends in having at least one type (1+), and at least three types (3+), of eating, activity, and weight-related problem from adolescence (Wave 1) to young adulthood (Wave 4) at 5-year intervals over a 15-year period, by gender.

The clustering of eating, activity, and weight-related problems is evident in examining the prevalence of having at least three problems at each of the study waves (Figure 2). Among females, prevalence ranged from 19.9% (Wave 1) to 30.5% (Wave 4), a statistically significant increase (t=5.31, p<0.001). Among males, prevalence ranged from 10.6% (Wave 1) to 22.1% (Wave 4; t=5.04, p<0.001). The prevalence of having at least three problematic behaviors was higher among females than males at each wave (t=3.12, p=0.002 at Wave 1; t=3.61, p<0.001 at Wave 2; t=4.27, p<0.001 at Wave 3; t=2.52, p=0.012 at Wave 4). Interactions between sex X study wave were not statistically significant.

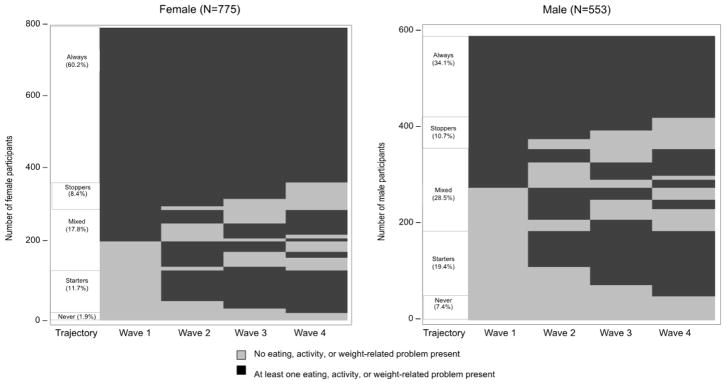

Trajectories for having any eating, activity, or weight-related problem were examined to assess the within-person stability of these problems over time (Figure 3). Trajectories were defined by combining information from all four waves and participants were categorized into five trajectories: always, never, stoppers, starters, and mixed. Among females (n=775), the majority (60.2%) had at least one problematic outcome at all assessment waves (always). Only 1.9% of female participants never had any of these problems (never), 8.4% had at least one problem at Wave 1, but stopped sometime between Wave 2 and 4 (stoppers), and 11.7% started to have a problem after Wave 1 and continued to have a problem through Wave 4 (starters). Finally, 17.8% of females had different patterns of trajectories over the four waves (mixed). Among males (n=553), 34.1% fell into the always category, 7.4% were in the never category, 19.4% were starters, and 10.7% were stoppers. A high percentage showed mixed patterns throughout the study period (28.5%).

Figure 3.

Trajectories for having any eating, activity, or weight-related problem.

Key: Always: Had at least one problem at all four waves; Stoppers: Had at least one problem at Wave 1, but not at later waves; Starters: Did not have a problem at Wave 1, but started at a future wave; Never: Did not have a problem at any waves; Mixed: Different pattern to any of the above.

DISCUSSION

There is both theoretical and empirical support for addressing a broad spectrum of eating, activity, and weight-related outcomes.13,16,23,31–34 Current study findings show that the majority of adolescents and young adults have problematic eating, activity, or weight-related outcomes and demonstrate the stability of these problems across critical developmental stages. Both the scope and the stability of having at least one eating, activity, or weight-related problem were particularly high among females. During adolescence, growth and development is rapid and behavioral patterns are becoming established as young people become more independent.7 Young adulthood is a time when many people begin to have their own families; thus, problematic eating, activity, and weight-related patterns during this life stage are also important. For example, periconceptual nutrition may impact the health of offspring through epigenetic imprinting35 and behavioral patterns modeled by parents may get passed on to the next generation.36,37 The finding that the majority of young people have at least one eating, activity, or weight-related problem throughout adolescence and young adulthood is thus of public health concern, indicating a need for population-based interventions.

The scope and stability of having at least one eating, activity, or weight-related problem among young women is particularly concerning; nearly two thirds of females had at least one problem at all four assessments, whereas less than 2% never had an eating, activity, or weight-related problem. The high prevalence and stability of eating, activity, and weight-related problems point to a need for interventions during or prior to adolescence and continuing throughout young adulthood. These findings expand upon prior research demonstrating that female adolescents and young adults are at high risk for body dissatisfaction and unhealthy weight control practices,13 most likely because of strong societal pressures emphasizing thinness38,39 within a society wherein energy-dense foods are often inexpensive and widely available,40 and opportunities for sedentary activity have increased.41,42 Interventions addressing unrealistic societal standards for female appearance are of high priority. The low level of MVPA among young females also demonstrates a need for interventions tailored to the unique barriers young adult females may experience (e.g., career development, parenting young children).

More than two thirds of male participants had at least one problem at each study wave and one third of males consistently had one of these problems across the study period. Although the prevalence of some problems was higher among females, the prevalence of obesity among males and females was similar. Furthermore, fast food intake decreased among females, but not among males, who had higher intakes at each study wave. Given that fast food intake tends to be energy dense,43 and that young adulthood is a high-risk period for weight gain,44,45 interventions to both decrease fast food intake and improve its nutritional density are warranted. Given that males may be less likely than females to be targeted, and to participate, in health-oriented interventions for themselves and their children,46–49 work is needed to meet the needs of young adult males. Similar to what is recommended for females, interventions aimed at health promotion in males, and particularly those focusing on healthy weight management, should ensure that these interventions do not inadvertently lead to undesirable outcomes such as unhealthy weight control practices and body dissatisfaction.

Among both female and male participants, the large increase in obesity over time is of public health concern. There is a need for prevention prior to adolescence, during adolescence, and throughout young adulthood.7,50–53 Because dieting and unhealthy weight control practices strongly predict weight gain over time,13,23,54–57 interventions should help young people avoid these behaviors, and instead engage in healthy eating and physical activity behaviors. Of note, although BMI cut off points are useful for examining population-based trends, other factors such as past history of an eating disorder, overall energy intake, and percentage body fat, should be taken into account in determining healthy weight status.

Limitations

Study strengths and limitations should be considered in interpreting the findings. This study allowed for the assessment of multiple eating, activity, and weight-related problems, in a large population, during the important transition from adolescence to adulthood. It may be advantageous to intervene on multiple interrelated outcomes within interventions,31,32,51 therefore it is useful to have data on a broad spectrum of eating, activity, and weight-related measures. That said, in the interest of parsimony, indicators from various domains were selected for inclusion, whereas other potentially relevant variables were excluded (e.g., fruit and vegetable intake). Furthermore, in this study, associations between the different measures were not examined; future analyses should examine these associations over time (e.g., how body dissatisfaction is related to physical activity). Although height and weight were assessed via self-report at all assessments, at Wave 1 all participants also had their height and weight measured and at Wave 3 a validation substudy was conducted; correlations between measured and reported heights and weights were very high at both timepoints.58–60 Although having data over a 15-year period is a study strength, the 5-year intervals between assessments does not allow for the capture of changes during these periods. Additionally, data were not collected at baseline on pubertal development, which can be useful in looking at weight-related variables. Although attrition was a study limitation, statistical weighting was employed to allow for generalizations to be made to the original baseline population.30 Finally, the study population was originally from one geographic location and analyses were not stratified by ethnicity/race; future research should examine trends in broader populations and by subgroups.

CONCLUSIONS

Study findings indicate that eating, activity, and weight-related problems are prevalent and have high stability over critical stages of physical and psychosocial development. Addressing eating, activity, and weight-related concerns in a comprehensive manner, both early on and throughout adolescence and young adulthood, is warranted. An example of an intervention that addresses a broad spectrum of eating, activity, and weight-related problems in adolescent girls is New Moves61 (www.newmovesonline.com). New Moves is designed as an alternative physical education class, with sessions on a non-dieting approach to healthy eating and body image, which can be adapted to other settings. To improve the broad spectrum of eating, activity, and weight-related problems that are associated with adverse health outcomes, possible policy interventions include efforts to ensure that healthy food options and opportunities for physical activity are available, accessible, and affordable for young people and their families, whereas there should be limitations on unhealthy exposures (e.g., fast food options within and adjacent to schools, false media advertisements for weight control products, and ongoing exposure to extremely thin media images). Community and school-based interventions need to be monitored to ensure that messages given do not inadvertently lead to one problem (e.g., body dissatisfaction) while trying to solve another problem (e.g., obesity). Clinical practices should involve working with adolescents and their families toward preventing the broad spectrum of eating, activity, and weight-related problems,50,51 and appropriate guidelines and services are needed to meet the needs of young adults.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute through grant number R01HL116892.

DNS is principal investigator of the study and wrote the manuscript. MMW is a co-investigator on the study and contributed to data analysis and interpretation. CC conducted data analysis for this study. NL is the study project director, managed acquisition of data, and contributed to writing. MJC and NES contributed to writing this manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and approved the manuscript.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or NIH.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among U.S. children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson MC, Neumark-Stzainer D, Hannan PJ, Sirard JR, Story M. Longitudinal and secular trends in physical activity and sedentary behavior during adolescence. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):e1627–1634. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hazzard VM, Hahn SL, Sonneville KR. Weight misperception and disordered weight control behaviors among U.S. high school students with overweight and obesity: Associations and trends, 1999–2013. Eat Behav. 2017;26:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falbe J, Willett WC, Rosner B, et al. Longitudinal relations of television, electronic games, and digital versatile discs with changes in diet in adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(4):1173–1181. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.088500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson NI, Story M. Adolescent nutrition and physical activity. In: Fisher M, Alderman E, Kreipe R, Rosenfeld W, editors. American Academy of Pediatrics: Textbook of Adolescent Health Care. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2011. pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holt K, Wooldridge NH, Story M, Sofka D. Adolescence. In: Holt K, Wooldridge NH, Story M, Sofka D, editors. Bright Futures Nutrition. 3. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2011. pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson MC, Story M, Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Lytle LA. Emerging adulthood and college-aged youth: An overlooked age for weight-related behavior change. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(10):2205–2211. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niemeier HM, Raynor HA, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Rogers ML, Wing RR. Fast food consumption and breakfast skipping: predictors of weight gain from adolescence to adulthood in a nationally representative sample. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(6):842–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira MA, Kartashov AI, Ebbeling CB, et al. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet. 2005;365(9453):36–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fogelholm M, Kukkonen-Harjula K. Does physical activity prevent weight gain--a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2000;1(2):95–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2000.00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berkey CS, Rockett HR, Field AE, et al. Activity, dietary intake, and weight changes in a longitudinal study of preadolescent and adolescent boys and girls. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4):E56. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.4.e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boone JE, Gordon-Larsen P, Adair LS, Popkin BM. Screen time and physical activity during adolescence: longitudinal effects on obesity in young adulthood. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4:26. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Story M, Standish AR. Dieting and unhealthy weight control behaviors during adolescence: Associations with 10-year changes in body mass index. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(1):80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loth KA, Watts AW, van den Berg P, Neumark-Sztainer D. Does body satisfaction help or harm overweight teens? A 10 -year longitudinal study of the relationship between body satisfaction and body mass index. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(5):559–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van den Berg P, Neumark-Sztainer D. Fat ‘n happy 5 years later: Is it bad for overweight girls to like their bodies? J Adolesc Health. 2007;41(4):415–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumark-Sztainer D, Paxton SJ, Hannan PJ, Haines J, Story M. Does body satisfaction matter? Five-year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(2):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stice E, Shaw HE. Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: a synthesis of research findings. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(5):985–993. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35(7):891–898. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barengo NC, Hu G, Lakka TA, et al. Low physical activity as a predictor for total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men and women in Finland. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(24):2204–2211. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paxton SJ, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Eisenberg ME. Body dissatisfaction prospectively predicts depressive mood and low self-esteem in adolescent girls and boys. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35(4):539–549. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Croll J. Overweight status and eating patterns among adolescents: where do youths stand in comparison with the Healthy People 2010 objectives? Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):844–851. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.5.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neumark-Sztainer D, Croll J, Story M, et al. Ethnic/racial differences in weight-related concerns and behaviors among adolescent girls and boys - Findings from Project EAT. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(5):963–974. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Guo J, et al. Obesity, disordered eating, and eating disorders in a longitudinal study of adolescents: How do dieters fare 5 years later? J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(4):559–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Larson NI, Eisenberg ME, Loth K. Dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(7):1004–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larson N, Neumark-Sztainer D, Harwood EM, et al. Do young adults participate in surveys that ‘go green’? Response rates to a web and mailed survey of weight-related behaviors. Int J Child Health Hum Dev. 2011;4(2):225–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neumark-Sztainer D, MacLehose RF, Watts AW, et al. How is the practice of yoga related to weight status? Population-based findings from Project EAT-IV. J Phys Act Health. 2017;14(12):905–912. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2016-0608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puhl RM, Wall MM, Chen C, et al. Experiences of weight teasing in adolescence and weight-related outcomes in adulthood: A 15-year longitudinal study. Prev Med. 2017;100:173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berge JM, Miller J, Watts A, et al. Intergenerational transmission of family meal patterns from adolescence to parenthood: longitudinal associations with parents’ dietary intake, weight-related behaviours and psychosocial well-being. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(2):299–308. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017002270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisenberg ME, Franz R, Berge JM, Loth KA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Significant others’ weight-related comments and their associations with weight-control behavior, muscle-enhancing behavior, and emotional well-being. Fam Syst Health. 2017;35(4):474–485. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Little RJA. Survey nonresponse adjustments for estimates of means. Int Stat Rev. 1986;54(2):139–157. doi: 10.2307/1403140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumark-Sztainer D. The interface between the eating disorders and obesity fields: moving toward a model of shared knowledge and collaboration. Eat Weight Disord. 2009;14(1):51–58. doi: 10.1007/BF03327795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neumark-Sztainer D. Integrating messages from the eating disorders field into obesity prevention. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2012;23(3):529–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall MM, Haines JI, et al. Shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating in adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(5):359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumark-Sztainer D, Levine MP, Paxton SJ, et al. Prevention of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: What next? Eat Disord. 2006;14(4):265–285. doi: 10.1080/10640260600796184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunford AR, Sangster JM. Maternal and paternal periconceptional nutrition as an indicator of offspring metabolic syndrome risk in later life through epigenetic imprinting: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2017;11(suppl 2):S655–S662. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loth KA, MacLehose RF, Larson N, Berge JM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Food availability, modeling and restriction: How are these different aspects of the family eating environment related to adolescent dietary intake? Appetite. 2016;96:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larsen JK, Hermans RC, Sleddens EF, et al. How parental dietary behavior and food parenting practices affect children's dietary behavior. Interacting sources of influence? Appetite. 2015;89:246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown A, Dittmar H. Think “thin” and feel bad: The role of appearance schema activation, attention level, and thin-ideal internalization for young women’s responses to ultra-thin media ideals. J Soc Clin Psych. 2005;24(8):1088–1113. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2005.24.8.1088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Engeln-Maddox R. Cognitive responses to idealized media images of women: The relationship of social comparison and critical processing to body image disturbance in college women. J Soc Clin Psych. 2005;24(8):1114–1138. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2005.24.8.1114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804–814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCormack GR, Virk JS. Driving towards obesity: a systematized literature review on the association between motor vehicle travel time and distance and weight status in adults. Prev Med. 2014;66:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brownson RC, Boehmer TK, Luke DA. Declining rates of physical activity in the United States: what are the contributors? Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:421–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prentice AM, Jebb SA. Fast foods, energy density and obesity: a possible mechanistic link. Obes Rev. 2003;4(4):187–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789X.2003.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gordon-Larsen P, The NS, Adair LS. Longitudinal trends in obesity in the United States from adolescence to the third decade of life. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(9):1801–1804. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kimokoti RW, Newby PK, Gona P, et al. Patterns of weight change and progression to overweight and obesity differ in men and women: implications for research and interventions. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(8):1463–1475. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012003801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crane MM, LaRose JG, Espeland MA, Wing RR, Tate DF. Recruitment of young adults for weight gain prevention: randomized comparison of direct mail strategies. Trials. 2016;17(1):282. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1411-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crane MM, Ward DS, Lutes LD, Bowling JM, Tate DF. Theoretical and behavioral mediators of a weight loss intervention for men. Ann Behav Med. 2016;50(3):460–470. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9774-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crane MM, Lutes LD, Ward DS, Bowling JM, Tate DF. A randomized trial testing the efficacy of a novel approach to weight loss among men with overweight and obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23(12):2398–2405. doi: 10.1002/oby.21265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morgan PJ, Young MD, Lloyd AB, et al. Involvement of fathers in pediatric obesity treatment and prevention trials: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20162635. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Golden NH, Schneider M, Wood C, et al. Preventing obesity and eating disorders in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161649. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neumark-Sztainer D. Preventing obesity and eating disorders in adolescents: What can health care providers do? J Adolesc Health. 2009;44(3):206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laska MN, Pelletier JE, Larson NI, Story M. Interventions for weight gain prevention during the transition to young adulthood: A review of the literature. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(4):324–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Rex J. New Moves: a school-based obesity prevention program for adolescent girls. Prev Med. 2003;37(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chaput JP, Leblanc C, Perusse L, et al. Risk factors for adult overweight and obesity in the Quebec Family Study: have we been barking up the wrong tree? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17(10):1964–1970. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, et al. Relation between dieting and weight change among preadolescents and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):900–906. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stice E, Presnell K, Shaw H, Rohde P. Psychological and behavioral risk factors for obesity onset in adolescent girls: A prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(2):195–202. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Viner RM, Cole TJ. Who changes body mass between adolescence and adulthood? Factors predicting change in BMI between 16 year and 30 years in the 1970 British Birth Cohort. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30(9):1368–1374. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Himes JH, Hannan P, Wall M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Factors associated with errors in self-reports of stature, weight, and body mass index in Minnesota adolescents. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(4):272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sirard JR, Hannan P, Cutler GJ, Neumark-Sztainer D. Evaluation of 2 self-report measures of physical activity with accelerometry in young adults. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10(1):85–96. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Quick V, Wall M, Larson N, Haines J, Neumark-Sztainer D. Personal, behavioral and socio-environmental predictors of overweight incidence in young adults: 10-yr longitudinal findings. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:37. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Neumark-Sztainer D, Friend SE, Flattum CF, et al. New Moves - Preventing weight-related problems in adolescent girls: A group-randomized study. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(5):421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985;10(3):141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sallis JF, Condon SA, Goggin KJ, et al. The development of self-administered physical activity surveys for 4th grade students. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1993;64(1):25–31. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1993.10608775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pingitore R, Spring B, Garfield D. Gender differences in body satisfaction. Obes Res. 1997;5(5):402–409. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quick VM, Byrd-Bredbenner C. Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): norms for U.S. college students. Eat Weight Disord. 2013;18(1):29–35. doi: 10.1007/s40519-013-0015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000;314(314):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Must A, Dallal GE, Dietz WH. Reference data for obesity - 85th and 95th percentiles of body-mass index (Wt/Ht2) and triceps skinfold thickness. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53(4):839–846. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.5.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S102–S138. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]