Abstract

Background

Tumor proliferation often occurs from pathologic receptor upregulation. These receptors provide unique targets for near-infrared (NIR) probes that have fluorescence-guided surgery (FGS) applications. We demonstrate the use of three smart-targeted probes in a model of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Methods

A dose escalation study was performed using IntegriSense750, ProSense750EX, and ProSense750FAST in mice (n=5) bearing luciferase-positive SCC-1 flank xenograft tumors. Whole body fluorescence imaging was performed serially after intravenous injection using commercially available open-field (LUNA, Novadaq, Canada) and closed-field NIR systems (Pearl, LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). An ex vivo, whole-body biodistribution was conducted. Lastly, FGS was performed with IntegriSense750 to demonstrate orthotopic and metastatic disease localization.

Results

Disease fluorescence delineation was assessed by tumor-to-background fluorescence ratios (TBR). Peak TBR values were 3.3 for 1nmol ProSense750EX, 5.5 for 6nmol ProSense750FAST, and 10.8 for 4nmol IntegriSense750 at 5.5, 3, and 4d post administration, respectively. Agent utility is unique: ProSense750FAST provides sufficient contrast quickly (TBR: 1.5, 3h) while IntegriSense750 produces strong (TBR: 10.8) contrast with extended administration-to-resection time (96h). IntegriSense750 correctly identified all diseased nodes in situ during exploratory surgeries. Ex vivo, whole-body biodistribution was assessed by tumor-to-tissue florescence ratios (TTR). Agents provided sufficient fluorescence contrast to discriminate disease from background, TTR>1. IntegriSense750 was most robust in neural tissue (TTR: 64) while ProSense750EX was superior localizing disease against lung tissue (TBR: 13).

Conclusion

All three agents appear effective for FGS.

Keywords: optical guided surgery, head and neck cancer, surgical oncology, fluorescence imaging

INTRODUCTION

For many solid tumors, primary treatment is surgical resection with negative margins guided by intraoperative analysis of frozen tumor sections. This method has several limitations: high cost, increased operating time, sampling error, and, occasional discrepancy between frozen and permanent sections.1,2 Fluorescence imaging (FLI) has demonstrated considerable promise in oncologic surgery, including improved progression-free survival3 and reduced margin positivity rates.4,5 As FLI grows, researchers have focused on developing tumor-specific contrast agents to improve cancer detection at the molecular level while reducing the shortcomings of currently available imaging modalities.6 While many reports cite regulatory barriers for the clinical application of investigational new drugs7, there is a largely unrecognized preclinical market consisting of widely available and clinically applicable fluorescent probes. These probes are ideal for rapid clinical integration because dosing, image acquisition time, and toxicity studies have been completed. Furthermore, the industry in which they are produced has abundant resources to assist in their transition.

IntegriSense750, ProSense750EX, and ProSense750FAST are 3 non-peptide, smart-targeted probes initially designated as preclinical imaging agents and marketed as adjunct probes for measuring therapeutic response. These widely available optical imaging probes can be re-purposed for clinical use for tumor detection, progression, and therapeutic response. IntegriSense750 is a small molecule probe that binds strongly to the integrin αvβ3, a pivotal member in the angiogenesis cascade.8 ProSense750EX and ProSense750FAST are uniquely optically silent until locally activated by cathepsin, a cysteine protease pathologically overexpressed in cancer.9 This mechanism potentially results in higher tumor-to-background fluorescence contrast (TBR) when compared to nonspecific fluorescent agents. Both αvβ3 and cathepsin are upregulated in numerous cancer types.8–11 As such, these probes may provide specific tumor fluorescence contrast in human models.

To characterize agent usefulness for fluorescence-guided surgery (FGS), they were first assessed with a dose-time ranging study in a murine model of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Agent accumulation was evaluated with an ex vivo, 12-tissue, whole body fluorescence biodistribution. Lastly, clinical FGS translation feasibility was appraised using an orthotopic, metastatic disease model of HNSCC.

METHODS

Acquisition & Description of Optical Imaging Agents

Three non-peptide, smart-targeted probes were tested: Integrisense750, ProSense750EX, and ProSense750FAST (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). IntegriSense750 and ProSense750EX were supplied as 24nmol lyophilized solids requiring reconstitution in 1.2mL of 1X PBS. ProSense750FAST was received as a 48nmol lyophilized solid, reconstituted in 1.2mL of 1X PBS. Once solubilized, agents were administered via tail vein injections.

Cell Line and Animal Models

SCC-1 cells were maintained in complete DMEM containing 10% FBS and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. The SCC-1 cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). SCC-1 cells were genetically modified with a luciferase-expressing construct (Addgene, Cambridge, MA). Tumors were implanted into female nude athymic mice, aged 4–6w (Charles River Laboratories, Hartford, Connecticut). All experiments and euthanasia procedures were performed in accordance with the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Dose-Time Ranging

Two million luciferase-positive (Luc+) SCC-1 cells in 100μL of PBS were implanted into the right flank. Two weeks post-implantation, tumor-bearing mice received cohort-specific agents and doses (n=5). All groups were imaged with closed-field (Pearl, LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) FLI. Dose and imaging intervals were based on previously reported data provided by Perkin Elmer describing optimal conditions. From that dose, we also studied a dose higher and lower. IntegriSense750 was tested at 4, 2, and 1nmol; ProSense750EX at 4, 2, and 1nmol; and ProSense750FAST at 6, 4, and 2nmol. Imaging intervals postinjection are as follows: IntegriSense750 6, 12, 24, 48, 60, 72, 84, and 96h; ProSense750EX 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, 96, 108, 120, and 132h; and ProSense750FAST 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 54, and 72h.

Whole Body Ex Vivo BioDistribution

After final imaging, animals were euthanized and dissected into 12 different organs: brain, femur, heart, kidney, large and small intestines, leg muscle, liver, lungs, reproductive organs, spleen, and stomach. Tissues were imaged individually with closed-field FLI and mean fluorescence intensity per mg (MFI/mg) of tissue was calculated as previously described.12

Minimum Tumor Size Threshold

In a second analysis model, a representative mouse for each agent’s optimal dose, as determined in the dose-time ranging study, was used to assess the smallest amount of tumor tissue detectable. Excised tumors were sectioned and weighted to fragments of 5.0, 1.0, and 0.5mg. Individual fragments were placed back into the wound bed and reimaged on closed-field FLI. True tumor detection was defined by a TBR>1, when tumor mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was greater than background MFI. Additionally, each wound bed and tumor fragment combination was washed with 50μL of topical rLuciferase/Luciferin Reagent (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) and subsequently imaged on a Xengen IVIS 100 (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) bioluminescence imaging (BLI) device used to detect the presence of Luc+ SCC-1 cells.

Orthotopic and Metastatic Disease Model

A SCC-1-Luc+ tumor bolus of 2.5×105 cells in 25μL of PBS was implanted into the lingual apex (n=3). Tumors grew until local cervical lymph node metastases was confirmed by BLI. Mice (n=3) were then dosed with 4nmol IntegriSense750 96h before being sacrificed, dissected, and imaged on BLI and both closed-field and wide-field (LUNA, Novadaq, Canada) FLI. First overlaying skin was removed. Next, positive lymph node, confirmed on BLI, was excised following fluorescence guidance. Finally, the primary tumor was removed en bloc with FGS; BLI confirmed resection success.

Data Analysis

Open-field fluorescence images were analyzed with ImageStudio (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE), which functions to quantify MFI of hand-drawn regions of interest (ROI). To calculate in situ TBRs, a ROI was drawn around the tumor periphery - seen on bright field - and a second, background ROI was drawn on the anterior limb.

Biodistribution data was assessed by quantifying MFI/mg as previously described.12 Biodistriubtion tumor-to-tissue fluorescence ratios (TTR) are tumor-to-individual organ MFI/mg.

Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed, unpaired T-tests with SAS Statistical Analytics Software. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

RESULTS

Optimal dose-time ranging for fluorescent contrast enhancement

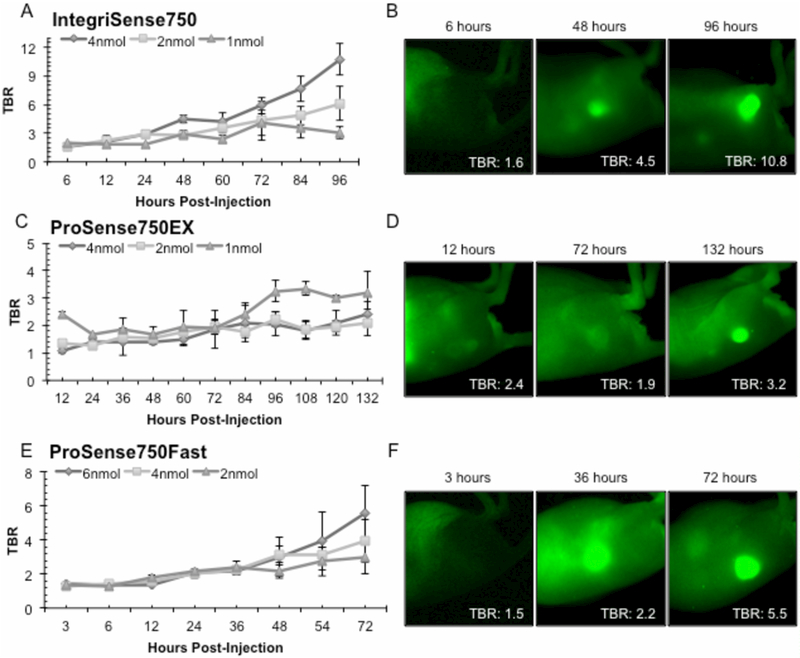

A dose-time ranging study was performed to better understand agent pharmacokinetics. Figure 1 depicts TBRs for the 3 tested agents at serial time points. All agents had a trend of increasing TBR values with time. Specifically, 4nmol IntegriSense750 peaked 96h post-administration (TBR: 10.7±1.7) whereas the 2nmol and 1nnol dose peaked at 96h (TBR: 6.1±1.8) and 72h (TBR: 3.1±0.7), respectively (1A). The 4nmol dose produced TBR values significantly greater than the 2nmol dose from 84–96h and the 1nmol dose from 24–96h post-injection (p<0.05). Representative closed-field FLI from initial, median, and final imaging time points of Integrisense750 4nmol are shown (1B). ProSense750EX 1nmol (1C) reached max TBR at 108h (TBR: 3.3±0.2). The 1nmol dose (1D) yielded significantly increased TBR values compared to the 2nmol, recommended dose from 84–132h and the 4nmol dose from 96–120h (p<0.05). ProSenseFAST (1E) doses (6nmol, 4nmol, and 2nmol) reached max TBR at 72h (TBR: 5.5±1.7, 3.9±1.2, 3.0±1.0, respectively). Figure 1F shows representative closed-field fluorescence acquisitions of 6nmol ProSenseFAST. Additionally, an appreciable accumulation in tumor and washout of background fluorescence occurs temporally for all 3 agents (1B, 1D, and 1F).

Figure 1.

displays results from the dose-time ranging study. (A) Quantification of the tumor-to-background (TBR) mean fluorescence intensity for IntegriSense750 across 96h. (B) Illustrates visually the change in tumor-to-background fluorescence contrast for the 4nmol dose at 6h, 48h, and 96h. (C) Shows the temporal effect of ProSense750EX across 132h along with (D) qualitative images of the 1nmol dose at the 12h, 72h, and 132h time points. (E) TBR values for ProSense750FAST through 72h (F) Images from the 6nmol ProSense750FAST dose at 3h, 36h, and 72h post injection. Data are average TBR ± SD.

Whole Body Ex Vivo Biodistribution Studies

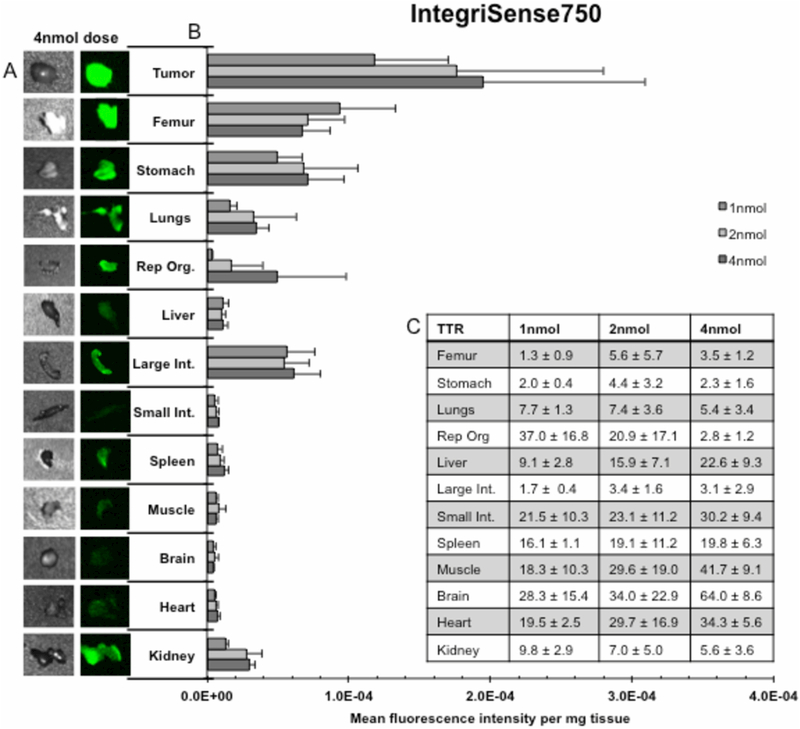

Agent specificity for tumor tissue was assessed by evaluating uptake in non-target tissues with a whole body, 12-tissue, ex vivo biodistribtion. Results from the IntegriSense750 cohort are displayed in Figure 2. Representative bright field and closed-field fluorescence images of each resected tissue from the 4nmol dose are shown (2A). Qualitatively, high intensity fluorescence is shown in the tumor when compared to normal tissues. MFI/mg values (2B) are significantly greater (p<0.05) at the 4nmol, 2nmol, and 1nmol dose in tumor (MFI/mg: 1.9×10−4, 1.8×10−4, 1.2×10−4) compared to the majority of tissues, including: femur (only at 2nmol dose, MFI/mg: 7.1×10−5), reproductive organs (MFI/mg: 5.0×10−5, 1.7×10−5, 3.4×10−6), liver (MFI/mg: 1.2×10−5, 1.0×10−5, 1.1×10−5), small intestine (MFI/mg: 7.8×10−6, 6.0×10−6, 5.2×10−6), spleen (MFI/mg: 1.3×10−5, 9.5×10−6, 7.4×10−6), muscle (MFI/mg: 5.9×10−6, 8.1×10−6, 5.8×10−6), brain (MFI/mg: 4.3×10−6, 5.8×10−6, 4.7×10−6), heart (MFI/mg: 7.1×10−6, 5.9×10−6, 4.9×10−6), and kidney (MFI/mg: 3.0×10−5, 2.8×10−5, 1.3×10−5), respectively. Peak TTR (2C) values occurred at the manufacturer’s recommended dose in 3 tissues: femur (TTR: 5.6±5.7), stomach (TTR: 4.4±3.2), and large intestine (TTR: 3.4±1.6). IntergriSense750’s highest TTR values include 4nmol brain (TTR 64.0±8.6), 4nmol muscle (TTR: 41.7±9.1), 4nmol heart (TTR: 34.3±5.6), 2nmol brain (TTR: 34.0±22.9), and 4nmol small intestine (TTR: 30.2±9.4). A dose dependent increase in TTR occurred between the 1nmol dose and the 4nmol dose for femur (TTR: 1.3±0.9 vs. 3.5±1.2), liver (TTR: 9.1±2.8 vs. 22.6±9.3), muscle (TTR: 18.3±10.3 vs. 41.7±9.1), and heart (TTR: 19.5±2.5 vs. 34.3±5.6), respectively.

Figures 2.

illustrate results from a 12 tissue, whole body, ex vivo biodistribution for IntegriSense750. (A) Qualitative assessment of the fluorescence signal produced in each of the 12 dissected tissues as well as tumor (left) for the 4nmol dose; bright field images detail tissue shape (right). (B) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity per milligram tissue (MFI/mg) ± SD for each dose for all 12 dissected tissues as well as tumor. (C) Table of tumor-to-tissue MFI/mg ratios (TTR) ± SD for all 12 dissected tissues.

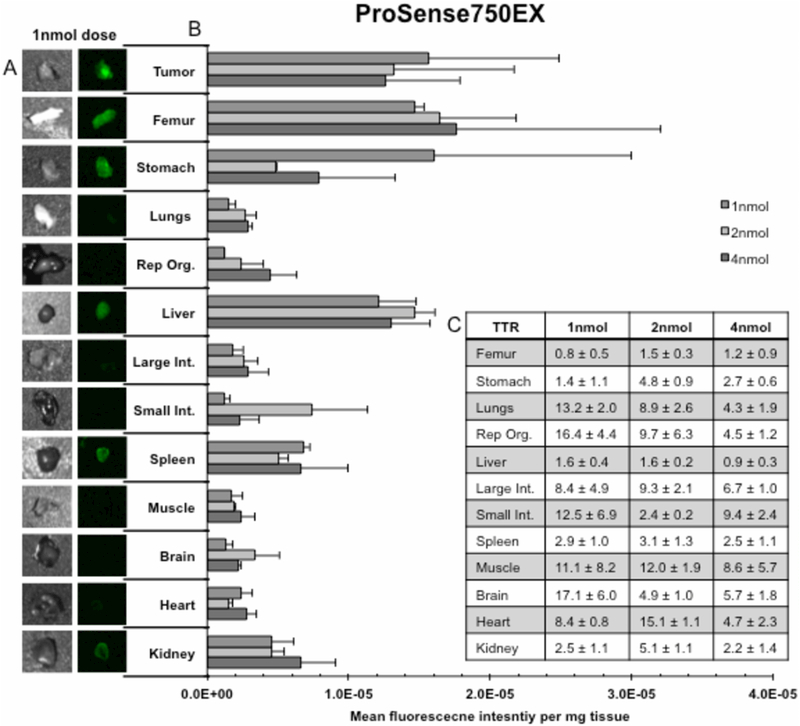

ProSense750EX cohort’s biodistribution is illustrated in Figure 3. Representative closed-field fluorescence acquisitions are shown (3A) for the 1nmol dose. Note the appreciable difference in fluorescence signal between tumor compared to lung, reproductive organs, large and small intestine, muscle, brain, and heart. Assessment of MFI/mg (3B) revealed a significantly greater (p<0.05) signal at the 4nmol, 2nmol, and 1nmol dose in tumor (MFI/mg: 1.3×10−5, 1.9×10−5, 1.6×10−5) compared to the majority of tissues, including: lungs (MFI/mg: 2.9×10−6, 2.7 ×10−6, 1.5×10−6), large intestine (MFI/mg: 2.9×10−6, 2.6×10−6, 1.8×10−6), respectively. Additionally, tumor MFI was significantly increased compared to stomach (MFI/mg: 4.8×10−6) and spleen (MFI/mg: 5.1×10−6) at the 2nmol dose, p<0.05. Peak TTR values (3C) occurred at the manufacturer’s recommended dose (2nmol) in 8 tissues: femur (TTR: 1.5±0.3), stomach (TTR: 4.8±0.9), liver (TTR: 1.6±0.2), large intestine (TTR: 9.3±2.1), spleen (TTR: 3.1±1.3), muscle (TTR: 12.0±1.9), heart (TTR: 15.1±1.1), and kidney (TTR: 5.1±1.1). Highest TTR values occurred at 50% manufacture’s recommended dose: 1nmol lungs (TTR: 13.2±2.0), 1nmol reproductive organs (TTR: 16.4±4.4), 1nmol small intestines (TTR: 12.5±6.9), and 1nmol brain (TTR: 17.1±6.0). A dose-dependent response occurred between: stomach 1nmol (TTR: 1.4±1.1) and 2nmol (TTR: 4.8±0.9); small intestine 2nmol (TTR: 2.4±0.2) and 4nmol (TTR: 9.4±2.4); heart 1nmol (TTR: 8.4±0.8) and 2nmol (TTR: 15.1±1.1); and kidney 1nmol (2.5±1.1) and 2nmol (TTR: 5.1±1.1), p<0.05.

Figures 3.

illustrate results from a 12 tissue, whole body, ex vivo biodistribution for ProSense750EX. (A) Qualitative assessment of the fluorescence signal produced in each of the 12 dissected tissues as well as tumor (left) for the 1nmol dose; bright field images detail tissue shape (right). (B) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity per milligram tissue (MFI/mg) ± SD for each dose for all 12 dissected tissues as well as tumor. (C) Table of tumor-to-tissue MFI/mg ratios (TTR) ± SD for all 12 dissected tissues.

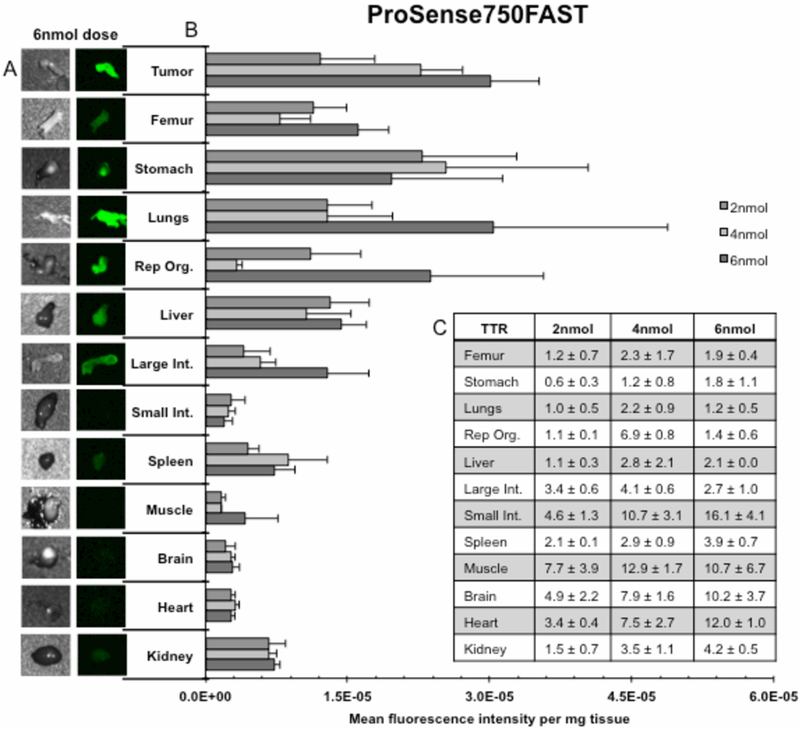

ProSense750FAST’s biodistribution is displayed in Figure 4. Representative bright field and fluorescent images (4A) are the 6nmol dose group, which achieved max tumor MFI/mg. Qualitatively, tumor fluorescence intensity was shown to be appreciably higher than other tissues, specifically the small intestine, spleen, muscle, brain, heart, and kidney. Quantitatively (4B), there was a dose dependent increase in tumor MFI/mg between 2nmol and 4nmol (p<0.001), as well as 4nmol and 6nmol (p<0.05). Furthermore, MFI/mg is significantly greater (p<0.05) in tumor (MFI/mg: 5.2×10−6, 4.4×10−6, and 5.9×10−6) at the 6nmol, 4nmol, and 2nmol doses compared to the majority of tissues. Assessment of TTR values (4C) reveals 6 tissues peaked at the manufacture’s recommended 4nmol dose: femur (TTR: 2.3±1.7), lungs (TTR: 2.2±0.9), reproductive organs (TTR: 6.9±0.8), liver (TTR: 2.8±2.1), large intestine (TTR: 4.1±0.6), and muscle (TTR: 12.9±1.7). However, ProSense750FAST’s optimal TTR values occurred in 6nmol small intestine (TTR: 16.1±4.1), 4nmol small intestine (TTR: 10.7±3.1), 4nmol muscle (TTR: 12.9±1.7), 6nmol muscle (TTR: 10.7±6.7), and 6nmol heart (TTR: 12.0±1.0). A dose-dependent response was present between the 4nmol and 6nmol dose for heart (TTR: 7.5±2.7 and 12.0±1.0) and between the 2nmol and 4nmol dose for femur (TTR: 1.2±0.7 vs. 2.3±1.7), lungs (TTR: 1.0±0.5 vs. 2.2±0.9), reproductive organs (TTR: 1.1±0.1 vs. 6.9±0.8 vs.), small intestine (TTR: 4.6±1.3 vs. 10.7±3.1), muscle (TTR: 7.7±3.9 vs. 12.9±1.7), heart (TTR: 3.4±0.4 vs. 7.5±2.7), for kidney (TTR: 1.5±0.7 vs. 3.5±1.1), respectively.

Figures 4.

illustrate results from a 12 tissue, whole body, ex vivo biodistribution for ProSense750FAST. (A) Qualitative assessment of the fluorescence signal produced in each of the 12 dissected tissues as well as tumor (left) for the 6nmol dose; bright field images detail tissue shape (right). (B) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity per milligram tissue (MFI/mg) ± SD for each dose for all 12 dissected tissues as well as tumor. (C) Table of tumor-to-tissue MFI/mg ratios (TTR) ± SD for all 12 dissected tissues.

Smallest Detectable Tumor Fragment

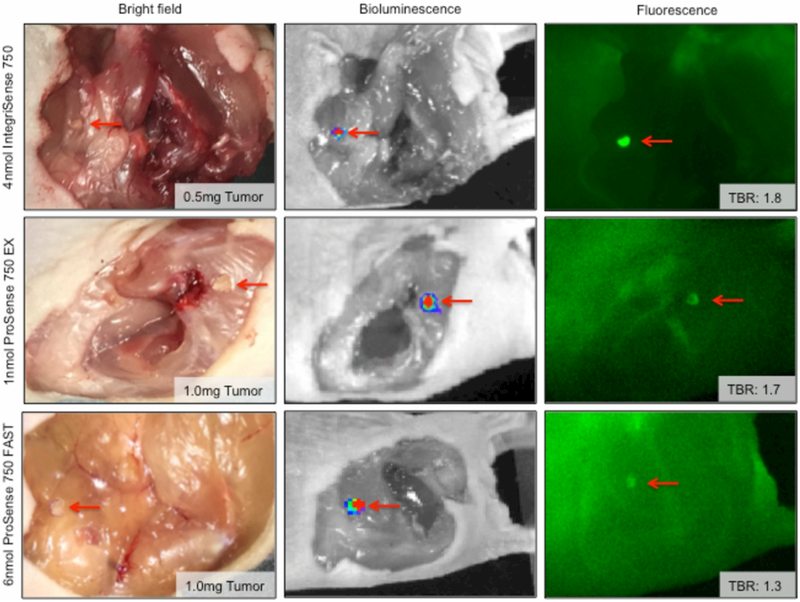

The fluorescence disease detection limit for each agent was assessed by TBR values of known tissue fragments. Figure 5 illustrates the smallest, positively identified tumor fragment for each agent administered at its optimal dose, noted in Figure 1. Bright field images show the tumor fragment in situ. BLI of each tumor fragment was used as the gold standard for SCC-1 localization, Closed-field FLI demonstrates the qualitative discriminability between tumor and background for each agent. Tumor fragments are indicated with red arrows. Foci of strong fluorescence intensity correlates with areas identified with bioluminescence. The mass of the smallest tumor fragment positively detected and the associated TBR are listed for each agent in bright field and closed-field FLI images, respectively. Quantitative results are as follows: IntegriSense750 (0.5mg tumor; TBR: 1.8), ProSense750EX (1.0mg tumor; TBR: 1.7), and ProSense750FAST (1.0mg tumor; TBR: 1.3).

Figure 5.

features images illustrating the tumor mass detection threshold for each agent at the corresponding optimal dose - 4nmol IntegriSense750, 1nmol ProSense750EX, and 6nmol ProSense750FAST. Bright field, bioluminescence, and fluorescence (closed-field) are shown with inset tumor fragment weight and corresponding TBR according to fluorescence. Red arrows indicate the tumor fragment.

Intra-Operative Model of Fluorescence Guided Surgery

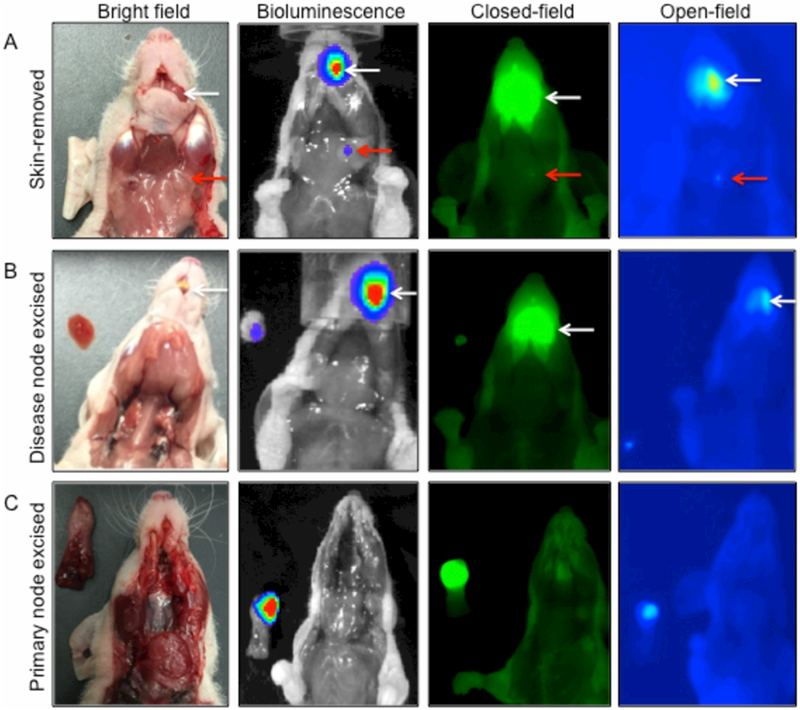

A proof of concept FGS resection model was developed to demonstrate intra-operative translatability. Figure 6 illustrates the clinical potential that fluorescently active probes can provide to augment complete resection of primary and metastatic disease. IntegriSense750 (4nmol) was selected for its ability to produce strong fluorescence contrast as seen in Figure 1A. BLI confirms Luc+-SCC-1 growth. Close-field and open-field FLI were used to localize disease foci. Primary and metastatic disease remains in situ (6A) and only overlaying skin is removed. A red arrow indicates the diseased lymph node; a white arrow denotes the location of the primary tumor. BLI signal was observed in the tongue and left cervical region, which correlated with both closed-field and open-field fluorescence intensity from the primary tumor site and diseased lymph node, respectively. Diseased lymph node was excised (6B) using FGS with open-field FLI and placed in the imaging field. BLI confirmed metastatic tumor excision. Open-field FLI guided primary site excision (6C). BLI counts emitted from the lingual apex correlate with FLI.

Figure 6.

displays the utility of the 4nmol IntegriSense750 dose for fluorescence-guided surgery (FGS) in an orthotopic, metastatic model of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Column 1 contains bright field images; while Column 2 the biolumninescence images, Column 3 the closed-field fluorescence images, and Column 4 the open-field fluorescence images. (A) Removal of overlaying skin. (B) Illustrates the utility of FGS to remove the diseased lymph node, and (C) demonstrates the function of FGS for removing the primary tumor en bloc. White and red arrows indicate primary and metastatic disease, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluates the utility of 3 non-peptide, smart-targeted probes, IntegriSense750, ProSense750EX, and ProSenseFAST, for FGS application. First, the temporal relationship of TBR values for each agent at 3 doses was assessed. Each agent provides adequate contrast for FGS as qualitatively demonstrated (Figure 1B, 1D, and 1F). Interestingly, translatability is agent specific. For example, for urgent FGS, the 2nmol ProSense750FAST dose can delineate cancerous tissue rapidly, within 3h (TBR: 1.5±0.1) (1E). However, when immediate resection is not necessary, and patients can be dosed 96h prior, the 6nmol IntegriSense750 dose provides optimal contrast (TBR: 10.8±1.7) (1A). On the other hand, for situations between urgent and delayed resection, ProSense750EX produces excellent contrast at 12h (TBR: 2.4±0.1) (1C).

Evaluations of dose also suggest that the manufacturer’s recommended dose could be further optimized for FGS. During the study, the 200% IntegriSense750, 50% ProSense750EX, and 150% ProSense750FAST doses provided optimal TBR values compared to the 100%, recommended dose (TBR: 10.8±1.7 vs. 6.1±1.8, 3.3±0.2 vs. 2.2±0.3, and 5.5±1.7 vs. 4.0±1.2, respectively). Even more, the 200% IntegriSense750 and 50% ProSense750EX doses yielded significantly greater (p<0.05) TBR values when compared to the 100% doses for both agents. Lastly, the trend of increasing TBR values for IntegriSense750 and ProSenseFAST agents may imply that peak TBR values have yet been determined.

Ex vivo biodistribution MFI/mg values were used to assess in vivo agent localization. Clinically, this evaluates agent accumulation in off target tissue location, which may result in side effect/toxicity profiles that do not justify the intended benefit. Biodistribution extent (12-tissue, whole body) was necessary to realize the most through, clinical evaluation. Results demonstrate all 3 agents have strong affinity (p<0.05) for tumor when compared to the majority of tissues. Furthermore, evaluation of TTR values simulates how tumor fluorescence would compare to background fluorescence in the 12 tissues tested. In other words, background uptake values reveal expected values if using the respective agent in combination with FGS for those tumor or tissue types. These data showed that all 3 agents provide adequate contrast in the majority of tissue bed types (TTR>1); thus, revealing the potential amenability of these agents in other tumor types. However, the strength of each agent to provide adequate contrast is dependent upon target expression and the local perfusion profile.13 For example, IntegriSense750 provided the greatest contrast in brain, muscle, heart, small intestine, liver, and spleen at the 200% dose; femur at the 100% dose; and reproductive organs and kidney at the 50% dose. On the other hand, ProSense750EX produced the highest contrast among the agents for lung at the 50% dose and large intestine and stomach at the 100% dose. When considering ProSense750FAST, the agent did not produce a max TBR for any of the tested tissues. However, the strength of ProSense750FAST is the ability to provide rapid disease specific fluorescence. Thus, appreciation of the true potential of ProSense750FAST was limited in this study as it washed out prior to the biodistribution. This is supported by its pharmacokinetics; though it has a similar mechanism to ProSense750EX, it is 20 times smaller and thereby facilitates swift translocation and activation.

Considering the biodistribution data in its entirety, we surmise that all 3 agents are translatable for FGS in multiple tumor locations. However, the optimal agent-dose combination is dependent on disease tissue bed type. That is, while our conclusions are limited to HNSCC testing, we believe multiple doses and agents must be tested for each cancer type to identify the ideal therapeutic, surgical agent-dose pairing.

Agent disease detection sensitivity was assessed by fragmenting tumors to masses of 5.0, 1.0, and 0.5mg. Chosen masses were based on current imaging detection limits; contemporary CT/MRI a maximum resolution of 1g or 1cm^3 of tissue.14 Results demonstrate ProSense750EX and ProSense750FAST were capable of detecting as little as 1.0mg of tumor (TBR: 1.7 and 1.8, respectively), while IntegriSense750 could localize 0.5mg of tumor tissue (TBR: 1.3) (Figure 5). Localization success was defined as greater tumor to off target background tissue mean fluorescence counts. Thus, agents were only considered successful if they provided positive tumor fragment fluorescence contrast. However, while this technology is limited by the ability to produce positive contrast, it is disease specific and not limited to anatomical or morphological differences in tissue such as CT/MRI/white light disease localization. FGS technical limitations include the level of aberrant tumor target expression, optimization of imaging devices, size or depth of occult cells relative to cut surface, and even quantum yield of the fluorescence molecule. Nevertheless, the authors’ postulate the impact of FGS will improve surgical morbidity and mortality.

Lastly, we employed an orthotopic HNSCC model with cervical metastasis to characterize the translatability of these agents during FGS (Figure 6). We selected the 4nmol IntegriSense750 dose as it provided the greatest overall tumor contrast during dose and timing studies. Qualitatively, IntegriSense750 generated strong fluorescence in primary and metastatic disease, which was confirmed with BLI. We then effectively performed FGS to completely excise the diseased node as seen by fluorescence in all tested animals. Lastly, a glossectomy under FGS guidance was performed successful remove primary disease en bloc (3/3 animals). This model demonstrates the utility of these agents during FGS to assist in complete disease resection.

While fluorescence guided surgery offers a plethora of exciting data, surgical utility is best determined with respect to the technology’s limitations. Categorically, these include: innate photon limitations (i.e. local fluorescence scattering events that blur disease boundaries), device limitations (i.e. need for improved hardware for optimization purposes), tumor limitations (i.e. low target expression relative to background, poor tumor perfusion), and surgeon’s limitations (i.e. little FGS training).14 To note, the authors’ advance FGS is not intended to replace a surgeon’s judgment, but rather serve as an adjunct to expand the ablative surgeon’s visual field. However, while the above list is not complete, many of the limitations are modifiable. Thus, it is the authors’ hopes that as technology further progresses, so too will follow FGS.

CONCLUSION

FGS’s surgical advantage arises from the technology’s ability to identify subclinical disease. That is to say, FGS has the potential to augment surgical success rates for pathology with a metastatic/recurrence risk and excision is associated with significant risk to surrounding structures, which is improved with fluorescence target localization. All three agents are amendable for use in FGS applications. Each agent-dose combination demonstrated robust translatability. Each agent provided strong fluorescence contrast, which was highly dependent on time-to-resection, cancer cell type, and tissue bed type. However, further research is required to further optimize these agents for translation into different cancer types.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Robert Armstrong Research Acceleration Fund, NIH T32CA091078, and institutional equipment and material loans from Novadaq, LI-COR Biosciences, and Perkin Elmer. The authors would like to thank Yolanda Hartman for her hard work and contributions to this study.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by the Robert Armstrong Research Acceleration Fund, NIH T32CA091078, the UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Preclinical Imaging Shared Facility (P30CA013148), and institutional equipment and material loans from Novadaq, LI-COR Biosciences, and Perkin Elmer.

Glossary

- BLI

Bioluminescence imaging

- FGS

Fluorescence-guided surgery

- FLI

Fluorescence imaging

- HNSCC

Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- MFI

Mean fluorescence intensity

- NIR

Near-infrared

- TBR

Tumor-to-background fluorescence ratio

- TTR

Tumor-to-tissue fluorescence ratio

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

DISCLOSURES

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest and nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosenthal EL, Warram JM, de Boer E, et al. Successful Translation of Fluorescence Navigation During Oncologic Surgery: A Consensus Report. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2016;57(1):144–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Twaalfhoven FC, Peters AA, Trimbos JB, Hermans J, Fleuren GJ. The accuracy of frozen section diagnosis of ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;41(3):189–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stummer W, Pichlmeier U, Meinel T, et al. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(5):392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tipirneni KE, Warram JM, Moore LS, et al. Oncologic Procedures Amenable to Fluorescence-guided Surgery. Ann Surg. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stummer W, Novotny A, Stepp H, Goetz C, Bise K, Reulen HJ. Fluorescence-guided resection of glioblastoma multiforme by using 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced porphyrins: a prospective study in 52 consecutive patients. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(6):1003–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frangioni JV. New technologies for human cancer imaging. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(24):4012–4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snoeks TJ, van Driel PB, Keereweer S, et al. Towards a successful clinical implementation of fluorescence-guided surgery. Molecular imaging and biology: MIB : the official publication of the Academy of Molecular Imaging. 2014;16(2):147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villegas-Pineda JC, Garibay-Cerdenares OL, Hernandez-Ramirez VI, et al. Integrins and haptoglobin: Molecules overexpressed in ovarian cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2015;211(12):973–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Habibollahi P, Figueiredo JL, Heidari P, et al. Optical Imaging with a Cathepsin B Activated Probe for the Enhanced Detection of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma by Dual Channel Fluorescent Upper GI Endoscopy. Theranostics. 2012;2(2):227–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knowles LM, Gurski LA, Engel C, Gnarra JR, Maranchie JK, Pilch J. Integrin alphavbeta3 and fibronectin upregulate Slug in cancer cells to promote clot invasion and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73(20):6175–6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorger M, Krueger JS, O'Neal M, Staflin K, Felding-Habermann B. Activation of tumor cell integrin alphavbeta3 controls angiogenesis and metastatic growth in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(26):10666–10671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zinn KR, Korb M, Samuel S, et al. IND-directed safety and biodistribution study of intravenously injected cetuximab-IRDye800 in cynomolgus macaques. Mol Imaging Biol. 2015;17(1):49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thurber GM, Weissleder R. Quantitating antibody uptake in vivo: conditional dependence on antigen expression levels. Mol Imaging Biol. 2011;13(4):623–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prince AC, Jani A, Korb M, et al. Characterizing the detection threshold for optical imaging in surgical oncology. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116(7):898–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]