A series of new benzo[d]thiazole-hydrazones were synthesized and characterized by analytical and spectroscopic techniques.

A series of new benzo[d]thiazole-hydrazones were synthesized and characterized by analytical and spectroscopic techniques.

Abstract

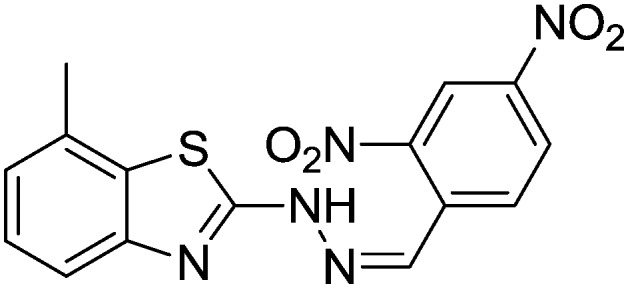

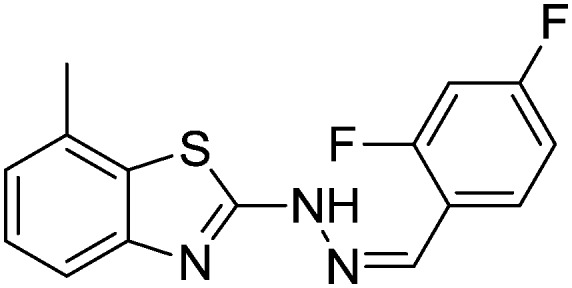

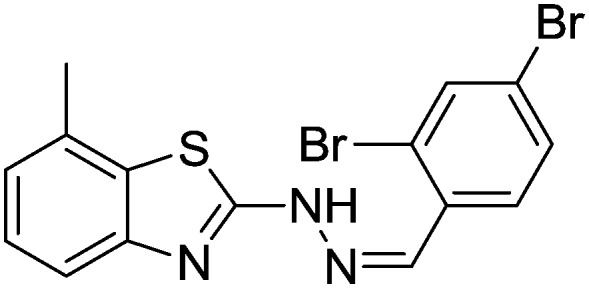

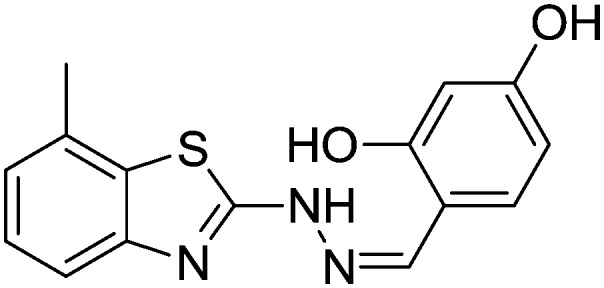

A series of new benzo[d]thiazole-hydrazones were synthesized and characterized by analytical and spectroscopic techniques. All the compounds were screened for their in vitro inhibition of H+/K+ ATPase and anti-inflammatory effects. The results revealed that compounds 6–8, 13–15, 18–20, 22, 23 and 27–30 displayed excellent inhibitory activity against H+/K+ ATPase, and their IC50 values were lower than those of the standard compound omeprazole. Compounds 2–5, 9–12, 28 and 30 exhibited better anti-inflammatory activity in comparison to the standard compound indomethacin. Studies of the structure–activity relationship (SAR) showed that electron-donating groups (OH and OCH3) favored inhibitory activity against H+/K+ ATPase, whereas electron-withdrawing groups (F, Cl, Br and NO2) favored anti-inflammatory activity, and derivatives with both electron-donating (OH and OCH3) and electron-withdrawing (Br) groups (16–18) displayed reasonable activity, whereas aliphatic analogues (24–26) exhibited less activity and heterocyclic analogues (27–30) displayed moderate activity in both biological studies. Molecular docking studies were performed for all the synthesized compounds, among which compounds 19 and 20 exhibited the highest docking scores for inhibitory activity against H+/K+ ATPase, whereas compounds 10 and 12 displayed the highest docking scores for anti-inflammatory activity.

1. Introduction

Gastric and duodenal ulcers are common diseases of the gastrointestinal tract with high clinical incidence rates, which may result in severe superior gastrointestinal bleeding. They may be caused by an imbalance between aggressive and defensive forces in the stomach and duodenum. The reduction of acid secretion has been proven to be a useful means for promoting the healing of ulcers.1 H+/K+ ATPase catalyzes the terminal step in gastric acid secretion, and the inhibition of H+/K+ ATPase can provide an intrinsically greater reduction in gastric acid secretion.2 As a result, H+/K+ ATPase could be a therapeutic target for various acid-related diseases. Although a number of H+/K+ ATPase inhibitors are available on the market, there is always a need for new agents with even better efficacy and safety profiles.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most commonly used anti-inflammatory agents. They exhibit their anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting the production of prostaglandin, which is a potent mediator of inflammation. The pharmacological target of NSAIDs is cyclooxygenase (COX), which catalyses the first committed step in arachidonic acid metabolism.3 The key cyclooxygenase enzyme exists in two isoforms, namely, the constitutive form COX-1 and the inducible form COX-2. COX-1 is present in most tissues, whereas COX-2 is expressed during inflammation.4 However, traditional NSAIDs that inhibit both cyclooxygenase enzymes may cause gastrointestinal side effects and selective COX-2 inhibitors such as coxibs have been reported to cause significant cardiovascular side effects.5 In order to overcome the above drawbacks, it is of great significance to develop novel compounds with improved profiles.

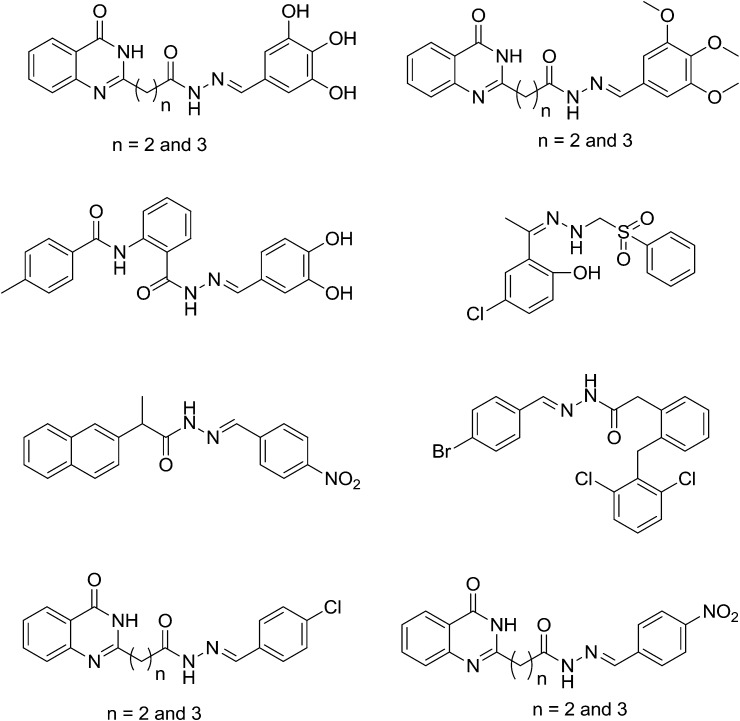

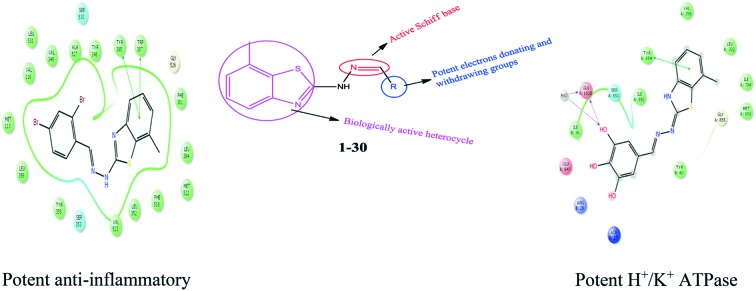

Benzo[d]thiazoles are bicyclic ring systems that are widespread and abundant in natural products. They have attracted increasing attention because of their diverse biological activities such as antimicrobial,6 antimalarial,7 anticonvulsant,8 antioxidant,9 anti-inflammatory,10 antitumor,11 analgesic,12 antitubercular,13 antidiabetic14 activities, and so on. Hydrazone Schiff bases are compounds that contain an azomethine group (–CH N–) in their structure, which is generally synthesized by the condensation of hydrazine derivatives with active carbonyl groups. Different derivatives of benzothiazole substituted at the 2 position have diverse therapeutic applications15 and anticancer effects.16 Hence, on the basis of the above observations and our ongoing research into the chemistry and bioactivity of novel heterocyclic compounds,2,17–20 we discuss our attempt to synthesize a new series of benzo[d]thiazole Schiff bases as potential H+/K+ ATPase inhibitors and anti-inflammatory agents in this paper. Some of the reported hydrazones with potent inhibitory activity against H+/K+ ATPase and anti-inflammatory activity are shown in Fig. 1.2,17,21–24

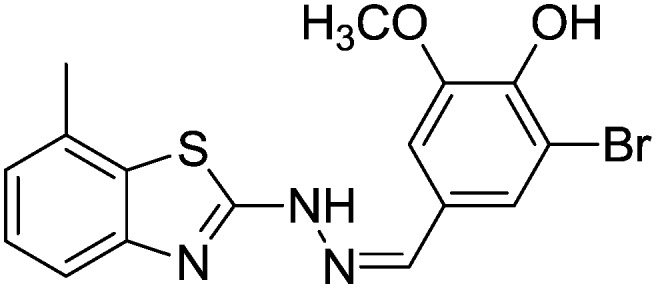

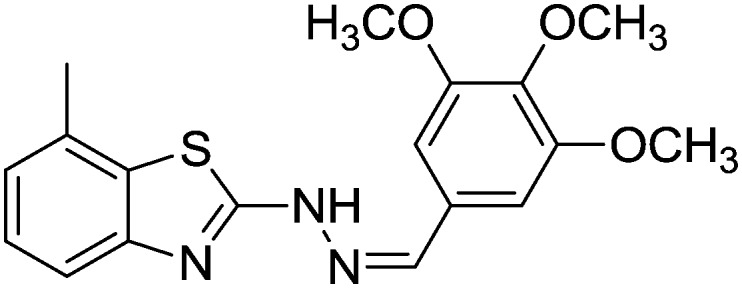

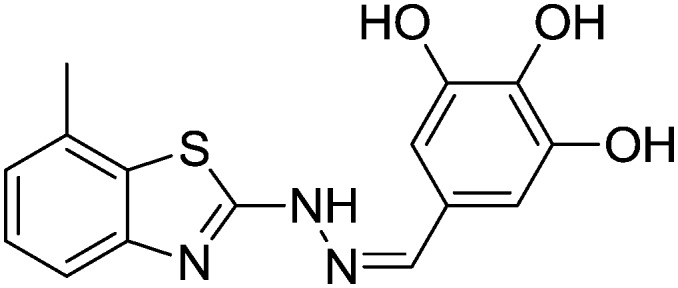

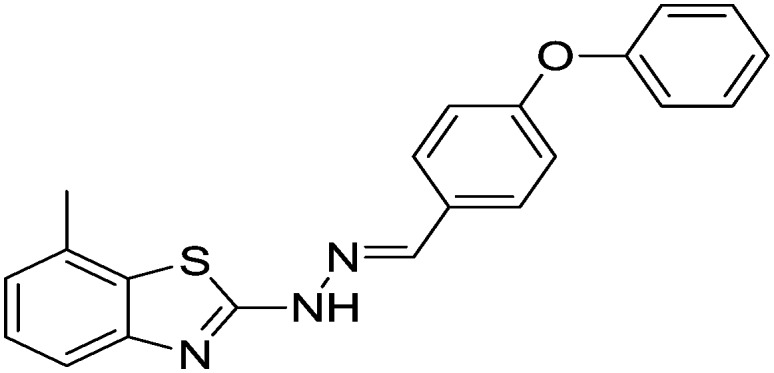

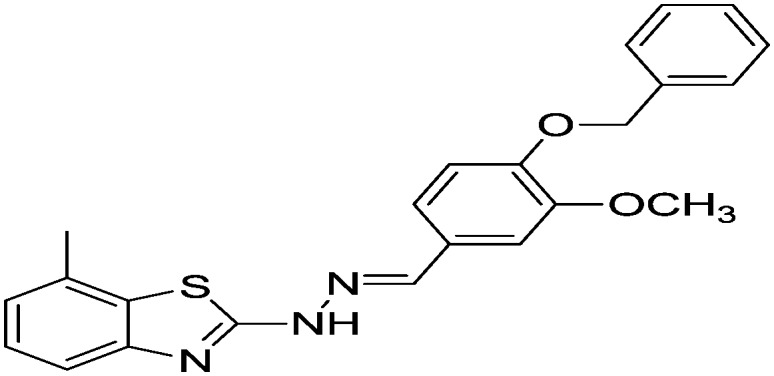

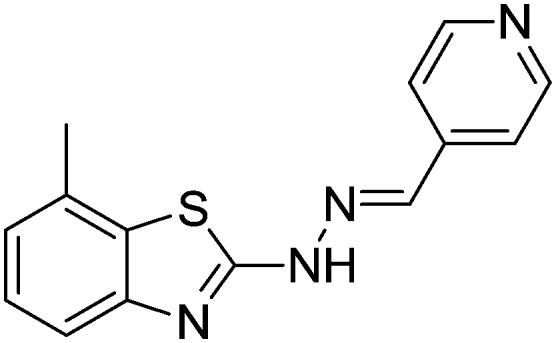

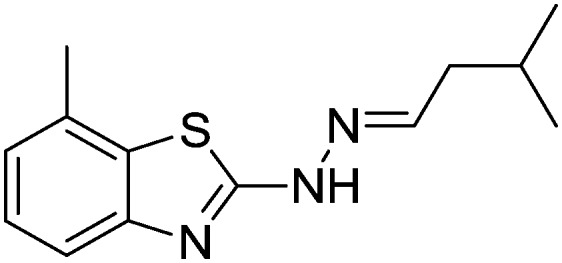

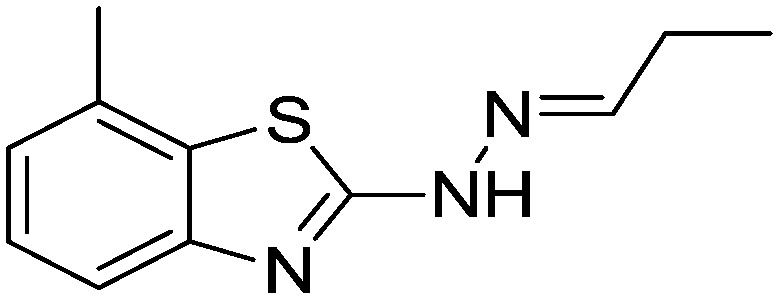

Fig. 1. Structures of representative hydrazones with potential inhibitory activity against H+/K+ ATPase and anti-inflammatory activity.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

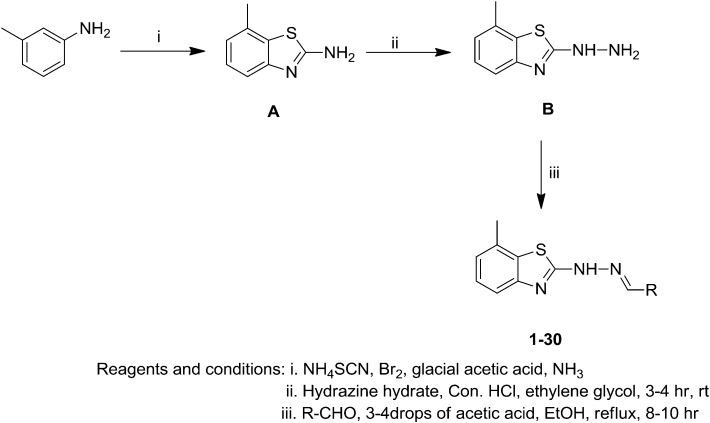

The preferred compounds were synthesized according to the steps illustrated in Scheme 1. 7-Methylbenzo[d]thiazol-2-amine (A) was synthesized according to the method reported in the literature.25,26 To a suspension of compound A in ethylene glycol, an excess amount of hydrazine hydrate and a catalytic amount of concentrated HCl were added. The mixture was refluxed for 3–4 h to obtain compound B. Compound B was continually reacted with various aldehydes in the presence of a catalytic amount of glacial acetic acid to afford hydrazones (1–30). All the derivatives were obtained in high yields by simple manipulation. The structures of all the newly synthesized compounds, including intermediates, were confirmed by IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR and mass spectral analysis (see ESI‡). The formation of hydrazones was confirmed by the presence of an absorption band at 1612–1630 cm–1 for the imine group, i.e., –N CH–, in the IR spectra and a singlet peak at δ = 7.80–8.02 ppm in the 1H NMR spectra. The chemical structures were confirmed by spectroscopic techniques.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the title compounds (1–30).

2.2. Biology

2.2.1. H+/K+ ATPase inhibition activity

All the synthesized compounds were screened for their in vitro inhibitory activity against H+/K+ ATPase, and the results are tabulated in Table 1. Omeprazole was used as a standard compound. Among the derivatives, compound 1, which had no substituents on the phenyl ring, exhibited activity with IC50 = 84 μg mL–1 but was thus less potent than omeprazole (IC50 = 46 μg mL–1). It can be inferred that compounds without substituents on the phenyl ring display less activity. Therefore, the effects of substituents on the phenyl ring were further investigated. Benzo[d]thiazoles with different electron-donating (OH and OCH3) or electron-withdrawing (Cl, NO2, F and Br) groups on the phenyl ring and those in which the phenyl ring was replaced with an aliphatic or heterocyclic substituent were synthesized and their antiulcer and anti-inflammatory activities were also evaluated. It was found that when there were hydroxyl and/or methoxy groups substituted on the phenyl ring, the corresponding derivatives exhibited highly potent inhibitory activity against H+/K+ ATPase.2,27 Compounds 6, 7, 8, 13, 14, 15, 19, 20, 27, 28 and 30 displayed excellent inhibitory activity against H+/K+ ATPase, with IC50 values of 26, 30, 34, 14, 20, 26, 12, 8, 38, 30 and 28 μg mL–1, respectively, which were much lower than that of the standard compound omeprazole (IC50 = 46 μg mL–1). The inhibitory activity increased together with an increase in the number of hydroxyl and methoxy groups. When three hydroxyl (20) or three methoxy (19) groups were present on the phenyl ring, the derivatives exhibited the most potent activity, with IC50 values of 8 and 12 μg mL–1, respectively, and the trends in activity were 1OH or OCH3 < 2OH or OCH3 < 3OH or OCH3. Furthermore, we were also interested in designing the molecule by replacing the aromatic aldehydes with aliphatic or heterocyclic aldehydes (23 and 27–30) and testing the products for their inhibitory activity against H+/K+ ATPase. Analogues derived from furan (27), thiophene (28) and indole (30) displayed good activity against H+/K+ ATPase. Derivatives with electron-withdrawing groups (Cl, NO2, F and Br) on the phenyl ring and aliphatic analogues (24–26) exhibited least antiulcer activity.2

Table 1. Activities against H+/K+ ATPase and anti-inflammatory activities of the synthesized compounds (1–30).

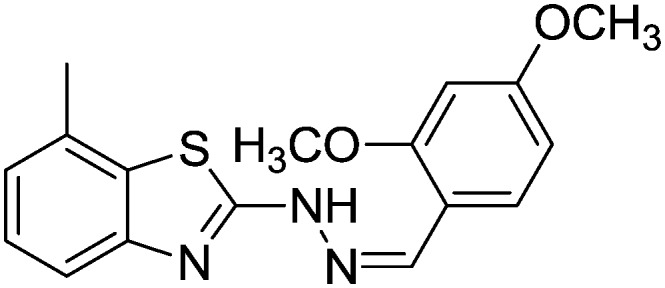

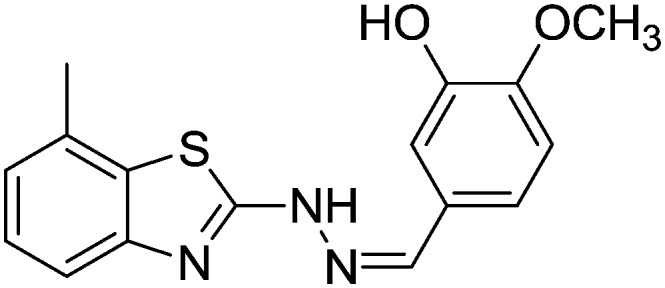

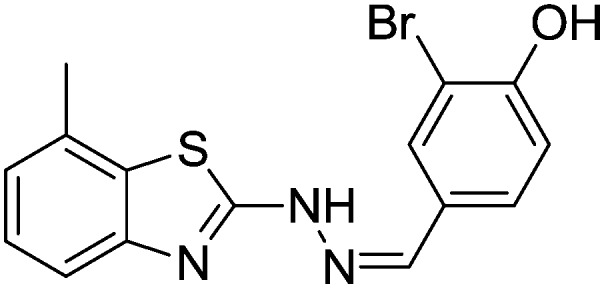

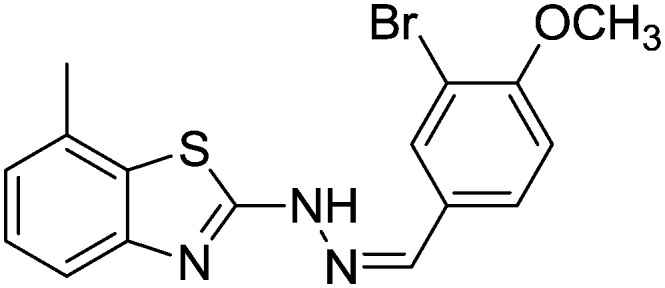

| Sl. no. | Structure | Antiulcer activity a (IC50 μg mL–1) | Anti-inflammatory activity a (IC50 μg mL–1) |

| 01 |

|

84.1 ± 1.02 | 80.14 ± 1.02 |

| 02 |

|

68.17 ± 1.23 | 28.74 ± 1.25 |

| 03 |

|

72.17 ± 0.58 | 24.07 ± 1.07 |

| 04 |

|

66.10 ± 1.09 | 32.15 ± 0.36 |

| 05 |

|

60.11 ± 0.46 | 20.07 ± 0.47 |

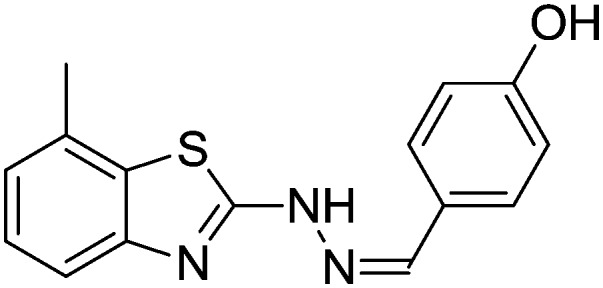

| 06 |

|

26.33 ± 0.47 | 60.01 ± 1.07 |

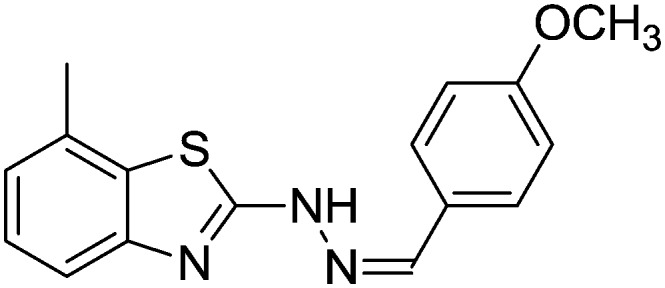

| 07 |

|

30.44 ± 0.74 | 72.69 ± 1.62 |

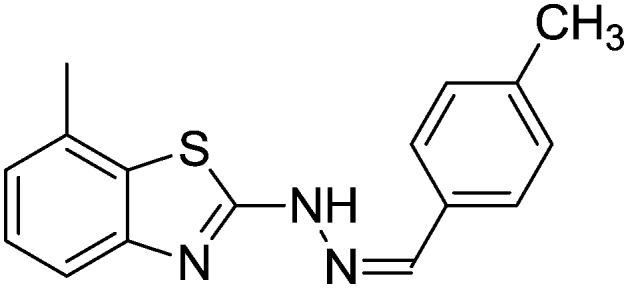

| 08 |

|

34.17 ± 1.14 | 54.31 ± 1.39 |

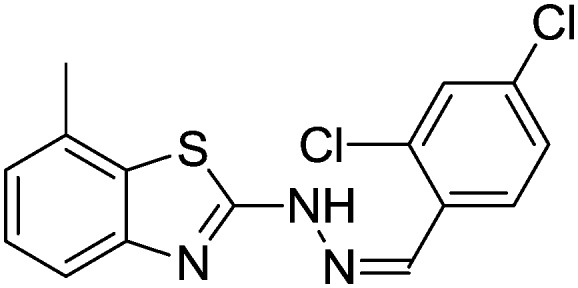

| 09 |

|

68.94 ± 0.68 | 18.17 ± 0.74 |

| 10 |

|

80.63 ± 1.84 | 12.74 ± 0.43 |

| 11 |

|

70.56 ± 0.47 | 16.14 ± 0.45 |

| 12 |

|

66.14 ± 0.40 | 10.12 ± 0.34 |

| 13 |

|

14.12 ± 0.77 | 58.17 ± 0.62 |

| 14 |

|

20.37 ± 0.46 | 68.10 ± 0.64 |

| 15 |

|

26.19 ± 0.33 | 56.18 ± 1.34 |

| 16 |

|

48.06 ± 0.88 | 52.38 ± 0.95 |

| 17 |

|

54.38 ± 0.66 | 58.64 ± 0.74 |

| 18 |

|

42.07 ± 0.74 | 56.38 ± 0.74 |

| 19 |

|

12.77 ± 0.17 | 74.58 ± 0.52 |

| 20 |

|

8.99 ± 0.78 | 68.56 ± 0.73 |

| 21 |

|

56.38 ± 0.75 | 60.89 ± 0.78 |

| 22 |

|

42.86 ± 0.23 | 66.19 ± 0.17 |

| 23 |

|

40.18 ± 0.85 | 54.19 ± 0.49 |

| 24 |

|

82.19 ± 1.59 | 90.74 ± 0.45 |

| 25 |

|

80.17 ± 0.99 | 78.46 ± 0.74 |

| 26 |

|

72.15 ± 0.88 | 82.16 ± 0.77 |

| 27 |

|

38.26 ± 0.47 | 50.14 ± 0.17 |

| 28 |

|

30.44 ± 0.18 | 28.74 ± 0.17 |

| 29 |

|

42.56 ± 0.87 | 46.18 ± 0.48 |

| 30 |

|

28.14 ± 0.49 | 30.18 ± 0.74 |

| Omeprazole | 46.14 ± 0.15 | — | |

| Indomethacin | — | 40.04 ± 0.45 |

aThe values are the means of three determinations, the ranges of which were <5% of the mean in all cases.

2.2.2. Anti-inflammatory activity

All the synthesized compounds were investigated for their in vitro anti-inflammatory activity using a known literature procedure on human erythrocytes.28 A significant number of compounds were identified as displaying excellent to moderate inhibitory activity in comparison to the standard drug indomethacin. The IC50 values determined for the compounds showed that more than 50% of the compounds had higher inhibitory concentrations (Table 1). Compounds 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 28 and 30 displayed excellent activity, with IC50 values of 28, 24, 32, 20, 18, 12, 16, 10, 28 and 30 μg mL–1, respectively, which were much lower than that of the standard drug indomethacin (IC50 = 40 μg mL–1).

In general, the presence of electron-withdrawing groups (2–5 and 9–12) favored anti-inflammatory activity,17 and the presence of two electron-withdrawing groups (9–12) made the molecules highly active. The presence of electron-donating groups in combination with electron-withdrawing groups decreased the activity (16–18). Derivatives with electron-donating groups (OH and OCH3) on the phenyl ring and the aliphatic analogues 24–26 displayed the least activity, and among those with heterocyclic moieties 28 and 29 exhibited good anti-inflammatory activity.

2.2.3. Docking studies

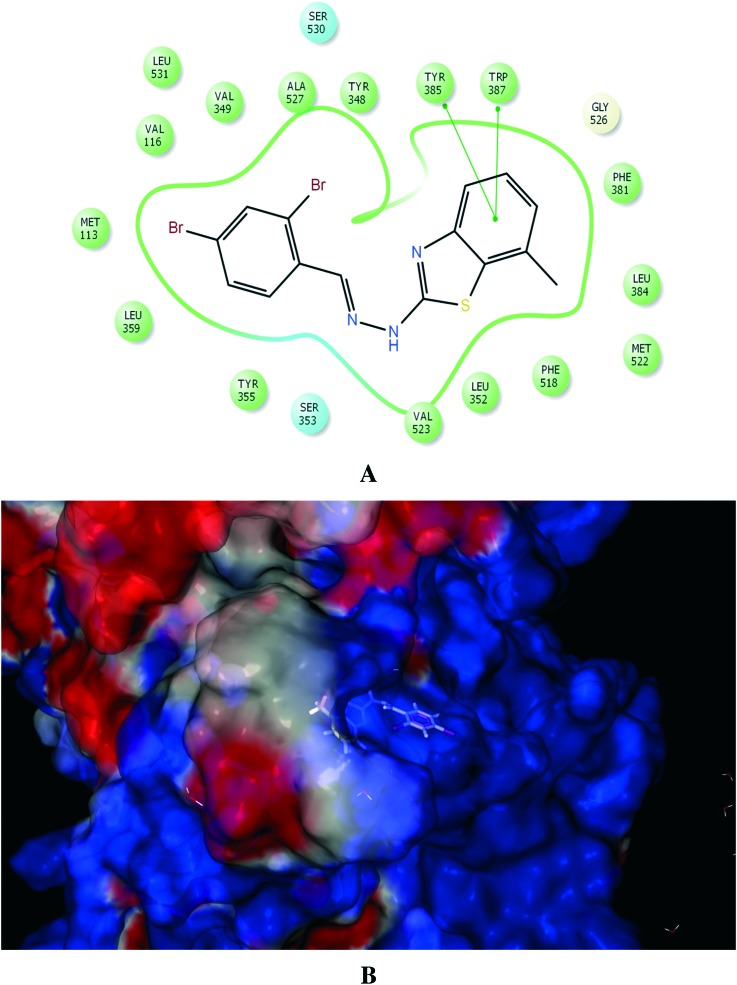

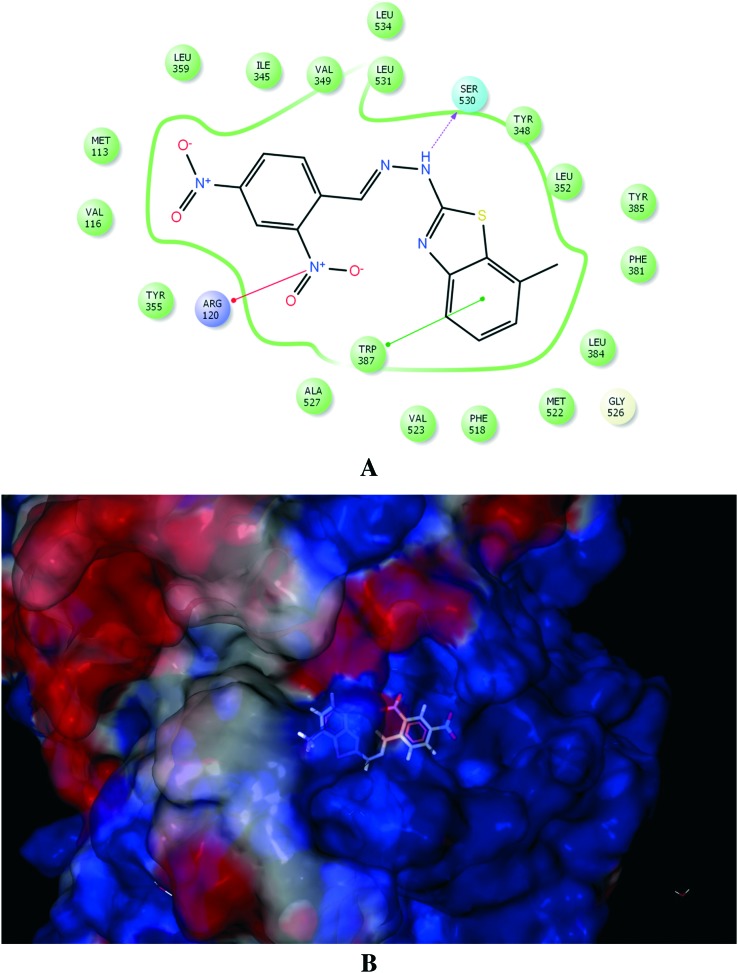

PLA2 is the first upstream enzyme in the inflammatory cascade, followed by COX-2 or LOXs, which are activated during tissue damage or inflammation.29 The current therapy for inflammation comprises non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), owing to their inherent capability to inhibit the first downstream enzymes, namely, cyclooxygenases (COXs), which are the key enzymes involved in arachidonic acid metabolism. However, the long-term use of NSAIDs may give rise to marked gastrointestinal (GI) irritation and ulceration owing to their unwanted inhibition of COX-1. Hence, we aimed to assess the potency of our ligands against both main enzymes, which are COX-2 and H+/K+ ATPase during the process of inflammation and GI irritation. The active site of COX-2 was identified by creating a grid of 20 Å × 20 Å × 20 Å in x, y and z coordinates around diclofenac bound to COX-2. Indomethacin was chosen as a reference ligand to calculate RMSD values for the newly synthesized ligands. Among the 30 ligands that were docked with COX-2, the most potent ligands 12 and 10 gave D-scores of –8.90 and –8.69, respectively (Table 2). The docked configuration of ligand 12 displayed interactions with Arg120, Tyr385 and Tyr387 via π–π stacking (Fig. 2). These hydrophobic interactions indicated that ligand 12 binds deep in the core of the active site where the reference ligand binds. However, ligand 10 interacted with Arg120, Tyr387 and Ser530 (Fig. 3). Current anti-inflammatory drugs such as NSAIDs are closely related to gastric ulcers,30 as anti-inflammatory drugs cause gastric ulcers owing to the presence of free carboxylic groups.31 Hence, we docked the 30 newly synthesized ligands with H+/K+ ATPase to assess their antiulcer activity.

Table 2. Docking scores of all synthesized compounds against COX-2 and H+/K+ ATPase.

| Protein | COX-2 |

H+/K+ ATPase |

||||||||||

| Ligand | RMSD OPLS-2005 | Docking score | Glide ligand efficiency | Glide ligand efficiency Sa | Glide Gscore | Glide lipo | RMSD OPLS-2005 | Docking score | Glide ligand efficiency | Glide ligand efficiency Sa | Glide Gscore | Glide lipo |

| M-1 | 0.005 | –7.19 | –0.34 | –0.95 | –8.53 | –4.08 | 0.046 | –4.94 | –0.25 | –0.67 | –5.25 | –2.93 |

| M-2 | 0.033 | –8.33 | –0.46 | –1.21 | –8.74 | –4.33 | 0.009 | –5.11 | –0.30 | –0.77 | –5.12 | –2.53 |

| M-3 | 0.046 | –8.40 | –0.42 | –1.14 | –8.70 | –4.82 | 0.032 | –5.03 | –0.25 | –0.68 | –5.61 | –2.78 |

| M-4 | 0.038 | –8.30 | –0.44 | –1.17 | –8.76 | –4.29 | 0.036 | –5.16 | –0.18 | –0.56 | –5.51 | –3.12 |

| M-5 | 0.028 | –8.54 | –0.43 | –1.16 | –9.01 | –4.82 | 0.024 | –5.22 | –0.24 | –0.67 | –5.65 | –2.33 |

| M-6 | 0.021 | –7.56 | –0.34 | –0.96 | –7.97 | –4.46 | 0.021 | –5.53 | –0.25 | –0.70 | –5.94 | –3.04 |

| M-7 | 0.037 | –7.36 | –0.32 | –0.91 | –7.77 | –3.91 | 0.013 | –5.50 | –0.26 | –0.72 | –5.93 | –2.86 |

| M-8 | 0.023 | –7.86 | –0.36 | –1.00 | –8.28 | –4.01 | 0.015 | –5.36 | –0.26 | –0.70 | –5.80 | –2.61 |

| M-9 | 0.022 | –8.63 | –0.43 | –1.17 | –9.05 | –4.11 | 0.016 | –5.07 | –0.24 | –0.67 | –5.72 | –3.04 |

| M-10 | 0.002 | –8.69 | –0.46 | –1.22 | –9.09 | –4.12 | 0.014 | –5.03 | –0.23 | –0.64 | –5.25 | –2.29 |

| M-11 | 0.023 | –8.65 | –0.46 | –1.22 | –8.72 | –4.03 | 0.021 | –5.06 | –0.25 | –0.69 | –5.47 | –2.73 |

| M-12 | 0.001 | –8.90 | –0.42 | –1.17 | –9.33 | –4.50 | 0.038 | –5.14 | –0.27 | –0.72 | –5.61 | –2.56 |

| M-13 | 0.015 | –7.73 | –0.37 | –1.02 | –8.17 | –4.03 | 0.046 | –5.60 | –0.25 | –0.71 | –5.69 | –2.49 |

| M-14 | 0.008 | –7.43 | –0.34 | –0.95 | –7.84 | –4.19 | 0.023 | –5.57 | –0.29 | –0.78 | –5.64 | –2.74 |

| M-15 | 0.011 | –7.86 | –0.37 | –1.03 | –8.27 | –3.97 | 0.002 | –5.55 | –0.29 | –0.78 | –5.96 | –2.97 |

| M-16 | 0.030 | –7.96 | –0.40 | –1.08 | –8.07 | –4.15 | 0.023 | –5.25 | –0.24 | –0.67 | –5.66 | –3.02 |

| M-17 | 0.006 | –7.56 | –0.36 | –0.99 | –8.25 | –5.03 | 0.004 | –5.23 | –0.29 | –0.76 | –5.64 | –2.76 |

| M-18 | 0.001 | –7.83 | –0.31 | –0.92 | –8.66 | –4.39 | 0.03 | –5.30 | –0.27 | –0.72 | –5.41 | –2.63 |

| M-19 | 0.014 | –7.35 | –0.33 | –0.94 | –7.57 | –3.87 | 0.042 | –5.64 | –0.27 | –0.74 | –5.76 | –2.43 |

| M-20 | 0.016 | –7.38 | –0.35 | –0.97 | –8.02 | –4.28 | 0.022 | –5.67 | –0.28 | –0.77 | –6.10 | –3.01 |

| M-21 | 0.009 | –7.48 | –0.44 | –1.13 | –7.48 | –3.69 | 0.022 | –5.23 | –0.19 | –0.57 | –5.76 | –3.61 |

| M-22 | 0.017 | –7.44 | –0.34 | –0.95 | –8.96 | –4.04 | 0.006 | –5.26 | –0.25 | –0.69 | –5.55 | –2.76 |

| M-23 | 0.042 | –7.89 | –0.38 | –1.04 | –8.01 | –4.13 | 0.013 | –5.31 | –0.21 | –0.62 | –5.49 | –2.59 |

| M-24 | 0.016 | –7.05 | –0.47 | –1.16 | –7.06 | –3.36 | 0.017 | –4.95 | –0.28 | –0.72 | –5.37 | –2.14 |

| M-25 | 0.002 | –7.27 | –0.32 | –0.90 | –8.60 | –4.37 | 0.001 | –5.03 | –0.20 | –0.59 | –5.86 | –2.74 |

| M-26 | 0.037 | –7.12 | –0.36 | –0.97 | –8.45 | –4.50 | 0.048 | –5.04 | –0.19 | –0.58 | –5.39 | –3.18 |

| M-27 | 0.017 | –8.13 | –0.45 | –1.18 | –8.54 | –3.87 | 0.008 | –5.31 | –0.21 | –0.62 | –5.40 | –2.43 |

| M-28 | 0.004 | –8.38 | –0.42 | –1.14 | –8.82 | –4.23 | 0.004 | –5.43 | –0.27 | –0.74 | –5.87 | –2.64 |

| M-29 | 0.004 | –8.04 | –0.45 | –1.17 | –8.45 | –4.04 | 0.048 | –5.29 | –0.26 | –0.72 | –5.69 | –2.72 |

| M-30 | 0.023 | –8.16 | –0.41 | –1.11 | –8.62 | –4.76 | 0.001 | –5.51 | –0.26 | –0.72 | –5.92 | –3.23 |

| Indomethacin | 0.002 | –8.89 | –0.68 | –1.14 | –7.91 | –4.13 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Omeprazole | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.001 | –6.31 | –0.26 | –0.62 | –6.49 | –2.29 |

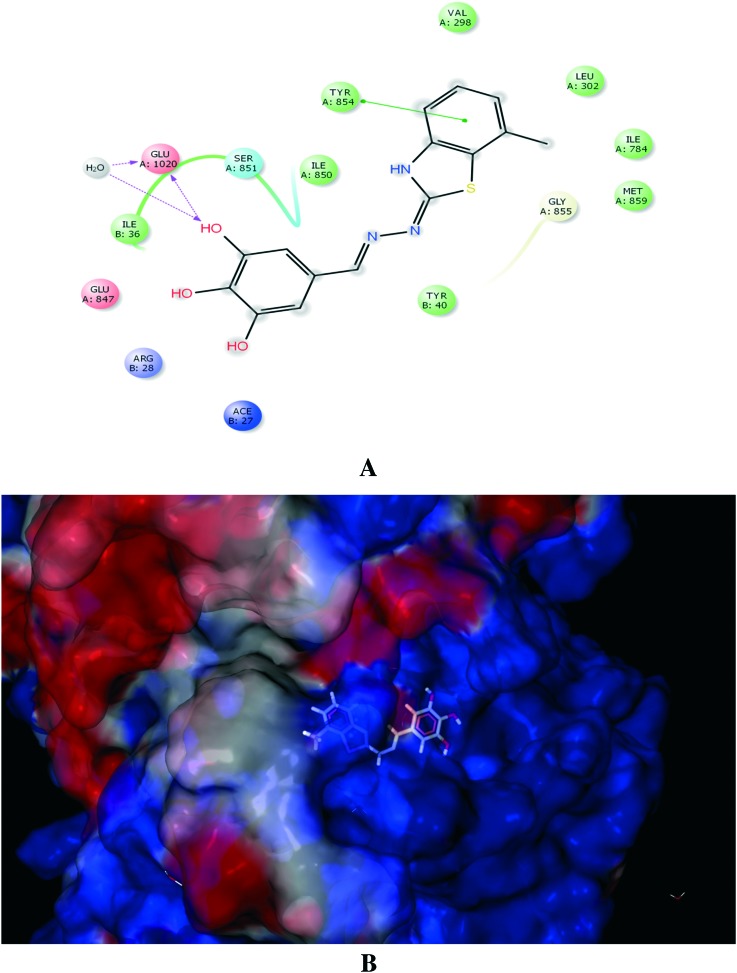

Fig. 2. (A) Molecular interaction of COX-2 enzyme with ligand 12. (B) Electrostatic surface representation of the protein depicting the best docking configuration for ligand 12.

Fig. 3. (A) Molecular interaction of COX-2 enzyme with ligand 10. (B) Electrostatic surface representation of the protein depicting the best docking configuration for ligand 10.

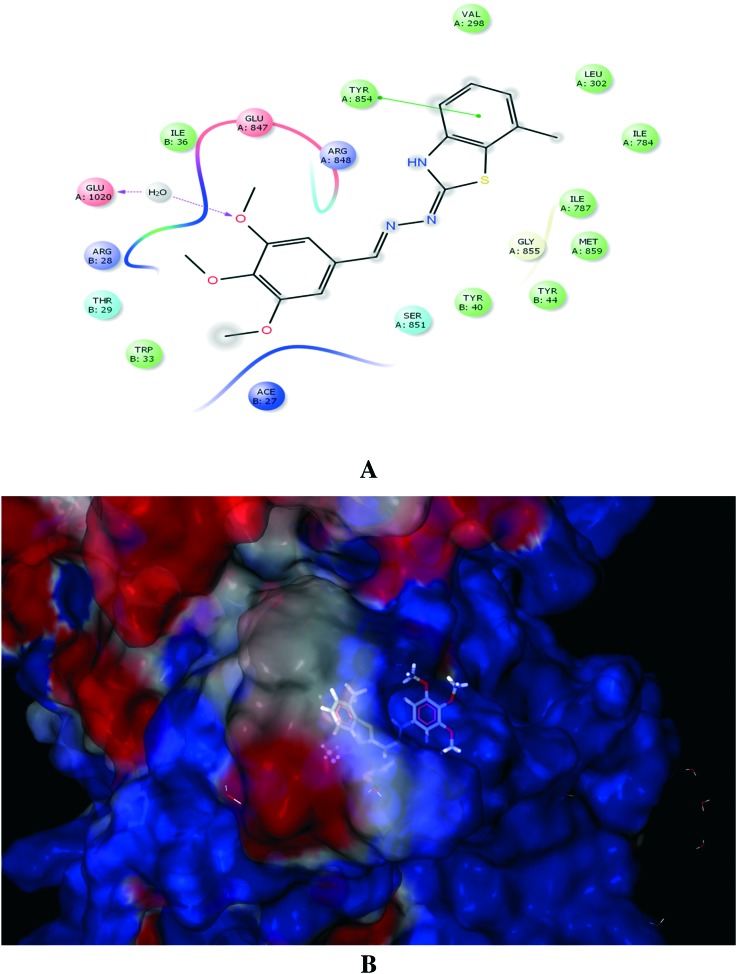

Molecular docking studies of H+/K+ ATPase have provided a homology model of H+/K+-ATPase; hence, H+/K+ ATPase was used to dock the ligands.32 Ligands 20 and 19 exhibited good binding affinity, with G-scores of –5.67 and –5.64, respectively. Ligand 20 displayed strong interactions with Asp897 and Glu899 (Fig. 4), whereas ligand 19 exhibited a favourable energy configuration towards Glu905 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. (A) Molecular interaction of H+/K+ ATPase enzyme with ligand 20. (B) Electrostatic surface representation of the protein depicting the best docking configuration for ligand 20.

Fig. 5. (A) Molecular interaction of H+/K+ ATPase enzyme with ligand 19. (B) Electrostatic surface representation of the protein depicting the best docking configuration for ligand 19.

ADME studies of these ligands (except for ligands 21 and 22) showed key characteristics of drugs, as they followed Lipinski's rule of a molecular weight below 500 Da, fewer than five hydrogen bond donors and fewer than ten acceptors. The value of QP log Po/w (octanol/water partition coefficient) for all the ligands was less than 5.33 All the ligands satisfied the criteria for the values of the octanol/gas (QP log Poct), water/gas (QP log Pw), and brain/blood (QP log BB) partition coefficients, skin permeability (QP log Kp) and aqueous solubility (QP log S), which can predict the properties of ligands within the permissible ranges (Table 3).

Table 3. Computer-aided ADME screening of the synthesized compounds.

| Ligand | Mol wt | a* | b* | c* | d* | e* | f* | g* | h* | i* | j* | k* | l* |

| M-1 | 267.35 | 31.20 | 8.36 | 3.61 | –4.38 | –6.09 | 4111 | 0.03 | 3803 | –0.58 | 0.15 | 100 | 0 |

| M-2 | 301.79 | 32.52 | 8.12 | 4.11 | –5.11 | –6.01 | 4111 | 0.20 | 9389 | –0.75 | 0.27 | 100 | 0 |

| M-3 | 312.35 | 32.99 | 9.54 | 2.82 | –4.52 | –6.04 | 389 | –1.15 | 282 | –2.69 | 0.11 | 89.85 | 0 |

| M-4 | 285.34 | 31.49 | 8.14 | 3.85 | –4.74 | –5.97 | 4111 | 0.14 | 6881 | –0.71 | 0.19 | 100 | 0 |

| M-5 | 346.24 | 32.87 | 8.13 | 4.18 | –5.23 | –6.04 | 4111 | 0.21 | 10 000 | –0.75 | 0.29 | 100 | 0 |

| M-6 | 283.35 | 31.07 | 10.46 | 2.88 | –4.12 | –5.97 | 1245 | –0.57 | 1046 | –1.64 | –0.01 | 100 | 0 |

| M-7 | 297.37 | 33.12 | 8.65 | 3.63 | –4.63 | –6.00 | 3262 | –0.16 | 2805 | –0.88 | 0.17 | 100 | 0 |

| M-8 | 281.38 | 33.07 | 8.06 | 3.92 | –4.95 | –6.01 | 4110 | 0.02 | 3803 | –0.77 | 0.31 | 100 | 0 |

| M-9 | 336.24 | 33.70 | 7.98 | 4.42 | –5.59 | –5.85 | 3465 | 0.23 | 10 000 | –1.02 | 0.37 | 100 | 0 |

| M-10 | 357.34 | 34.41 | 10.46 | 2.39 | –4.45 | –5.78 | 114 | –1.75 | 79 | –3.77 | 0.04 | 77.73 | 0 |

| M-11 | 303.33 | 31.83 | 8.03 | 3.97 | –5.05 | –5.88 | 3277 | 0.12 | 8283 | –1.01 | 0.23 | 100 | 0 |

| M-12 | 425.14 | 34.37 | 7.96 | 4.69 | –5.94 | –5.97 | 4139 | 0.37 | 10 000 | –0.87 | 0.41 | 100 | 0 |

| M-13 | 299.35 | 30.98 | 12.61 | 2.12 | –3.83 | –5.87 | 367.69 | –1.21 | 265 | –2.69 | –0.17 | 85.26 | 0 |

| M-14 | 327.40 | 35.13 | 8.88 | 3.84 | –4.89 | –5.96 | 4132 | –0.11 | 3825 | –0.75 | 0.18 | 100 | 0 |

| M-15 | 313.37 | 33.04 | 10.75 | 3.04 | –4.35 | –5.94 | 1489 | –0.59 | 1203 | –1.53 | 0.01 | 100 | 0 |

| M-16 | 362.24 | 32.70 | 10.23 | 3.46 | –4.89 | –5.92 | 1451 | –0.35 | 3104 | –1.65 | 0.11 | 100 | 0 |

| M-17 | 376.27 | 35.07 | 8.46 | 4.21 | –5.54 | –6.01 | 3261 | 0.01 | 7295 | –1.03 | 0.32 | 100 | 0 |

| M-18 | 392.27 | 34.58 | 10.48 | 3.68 | –5.07 | –5.88 | 2114 | –0.25 | 4529 | –1.36 | 0.13 | 100 | 0 |

| M-19 | 357.43 | 37.58 | 7.99 | 4.54 | –5.63 | –5.81 | 4086 | –0.12 | 3692 | –0.87 | 0.51 | 100 | 0 |

| M-20 | 315.35 | 30.85 | 14.65 | 1.37 | –3.54 | –5.76 | 158 | –1.67 | 110 | –3.43 | –0.33 | 74.35 | 0 |

| M-21 | 359.45 | 42.05 | 8.34 | 5.79 | –6.85 | –7.26 | 4087 | –0.07 | 3693 | –0.03 | 1.00 | 100 | 1 |

| M-22 | 389.47 | 43.35 | 9.93 | 5.25 | –6.35 | –7.22 | 3985 | –0.22 | 3600 | –0.01 | 0.65 | 100 | 1 |

| M-23 | 268.34 | 30.41 | 9.83 | 2.61 | –3.77 | –5.90 | 1762 | –0.36 | 1443 | –1.43 | –0.16 | 100 | 0 |

| M-24 | 247.36 | 28.26 | 6.74 | 3.22 | –4.16 | –5.03 | 3021 | –0.17 | 2668 | –1.51 | 0.09 | 100 | 0 |

| M-25 | 219.30 | 24.49 | 6.89 | 2.48 | –3.38 | –4.80 | 2537 | –0.17 | 2210 | –1.76 | –0.15 | 100 | 0 |

| M-26 | 275.41 | 31.62 | 6.32 | 3.99 | –5.06 | –5.59 | 2552 | –0.48 | 2223 | –1.37 | 0.31 | 100 | 0 |

| M-27 | 256.32 | 29.52 | 6.77 | 3.99 | –4.59 | –5.84 | 5072 | 0.19 | 4688 | –0.60 | 0.34 | 100 | 0 |

| M-28 | 272.38 | 29.66 | 4.85 | 4.31 | –4.65 | –5.48 | 3526 | 0.08 | 5481 | –1.02 | 0.37 | 100 | 0 |

| M-29 | 255.34 | 29.93 | 7.84 | 3.83 | –4.63 | –5.85 | 3385 | 0.00 | 3028 | –0.97 | 0.34 | 100 | 0 |

| M-30 | 305.40 | 35.44 | 7.19 | 4.70 | –5.81 | –6.29 | 2249 | –0.27 | 1928 | –1.09 | 0.72 | 100 | 0 |

| 95% range for drugs | 130.0/725.0 | 13.0/70.0 | 4.0/45.0 | –2.0/6.5 | –6.5/0.5 | Concern if below –5 | <25 poor, >500 good | –3.0/1.2 | <25 poor, >500 good | — | –1.5/1.5 | >80% is high | >4 |

3. Conclusions

In the present study, novel H+/K+ ATPase-inhibiting and anti-inflammatory hydrazones were synthesized by conjugating benzo[d]thiazoles with different aldehydes. Our studies revealed that compounds 6–8, 13–15, 18–20, 22 and 23, which had CH3, OH and/or OCH3 groups on the phenyl ring (electron-donating) or a heterocyclic moiety, exhibited more potent inhibitory activity against H+/K+ ATPase than the standard drug. Compounds 2–5 and 9–12, which had Cl, NO2, F and/or Br groups on the phenyl ring (electron-withdrawing), demonstrated excellent anti-inflammatory activity. Compounds 27–30, which contained a heterocyclic moiety, exhibited good inhibitory activity against H+/K+ ATPase as well as good anti-inflammatory activity. Compounds 24, 25 and 26 displayed less potent anti-H+/K+ ATPase and anti-inflammatory activities. Molecular docking studies were performed for all the synthesized compounds, among which compounds 19 and 20 gave the highest docking scores for inhibitory activity against H+/K+ ATPase, whereas compounds 10 and 12 gave the highest docking scores for anti-inflammatory activity.

4. Experimental

4.1. General

All chemicals and reagents were obtained from Merck (India) and Avra Synthesis (India) and were used without further purification. Melting points were determined with a Superfit melting point apparatus (India) and were uncorrected. FT-IR spectroscopy was performed with a Jasco spectrometer (Japan) using Nujol media. 1H NMR (400 MHz) and 13C NMR (100 MHz) spectra were recorded with an Agilent Technologies (USA) spectrometer using CDCl3 as the solvent. High-resolution mass spectroscopic analysis was performed using a Bruker MicroTOF QII mass spectrometer in positive mode. The progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC using silica gel coated on glass plates with a solvent system comprising chloroform/methanol/acetic acid in the ratio of 95 : 5 : 3 (Rf), and the compounds on the TLC plates were detected under UV light.

4.1.1. Synthesis of 2-hydrazinyl-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole (B)

Concentrated hydrochloric acid (10 mL) was added dropwise to a suspension of hydrazine hydrate (0.06 mol) in ethylene glycol (40 mL) at 5–6 °C, and then compound (A) (0.02 mol) was added. The mixture was refluxed for 2–3 h and cooled to room temperature. The reaction mixture was filtered and the resulting precipitate was washed with distilled water. Then, the resulting crude product was crystallized from ethanol to obtain the product (B).

4.1.2. General procedure for the synthesis of hydrazones (1–30)

Compound B (1 mmol) was dissolved in ethanol (10 mL g–1 compound) and treated with the appropriate aldehyde (1 mmol) in the presence of 5–7 drops (0.3–0.5 mL) of glacial acetic acid. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 8–10 h, and the completion of the reaction was monitored by TLC. After the completion of the reaction, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the mixture was cooled by adding ice-cold water. The resulting precipitate was filtered, washed with water and recrystallized from ethanol to obtain the desired benzo[d]thiazole-hydrazone (1–30).

4.1.3. 2-Hydrazinyl-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [B]

Yield 78.9%, light yellow solid, Rf = 0.34, m.p. 208–210 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1920, 3310; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.54 (s, 3H, CH3), 4.82 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.01 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.46 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 11.20 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.2, 118.5, 121.6, 126.6, 128.7, 130.4, 151.1, 173.4; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C8H9N3S: 180.0517; found: 180.0526.

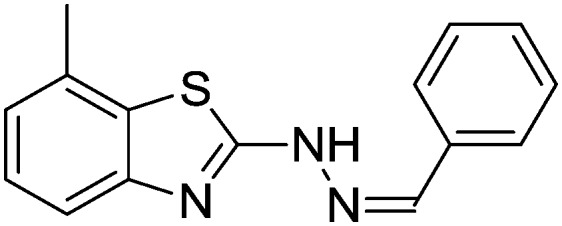

4.1.4. 2-(2-Benzylidenehydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [1]

Yield 91.2%, light yellow solid, Rf = 0.58, m.p. 170–172 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1611, 3314; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.54 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.08 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.16 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.34–7.41 (m, 3H, Ar–H), 7.52 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.63–7.66 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.86 (s, 1H, –N CH), 9.63 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.0, 118.8, 122.2, 125.1, 126.9, 127.0, 127.7, 128.6, 129.7, 134.0, 143.9, 148.2, 167.8; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H13N3S: 268.0830; found: 268.0834.

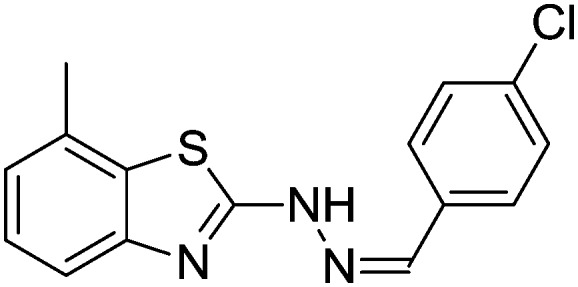

4.1.5. 2-(2-(4-Chlorobenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [2]

Yield 83.9%, white solid, Rf = 0.44, m.p. 188–189 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1611, 3348; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.52 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.05 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.17 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.50 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.60–7.62 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.77–7.79 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.89 (s, 1H, –N CH), 10.8 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.7, 117.9, 123.4, 125.7, 127.3, 128.4, 129.7, 130.1, 133.5, 137.9, 142.7, 148.0, 167.2; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H12ClN3S: 302.0440; found: 302.0428.

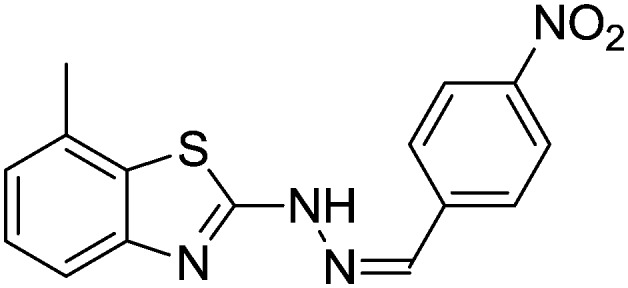

4.1.6. 7-Methyl-2-(2-(4-nitrobenzylidene)hydrazinyl)benzo[d]thiazole [3]

Yield 88.5%, yellow solid, Rf = 0.49, m.p. 201–202 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1610, 3337; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.56 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.07 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.14 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 7.26 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.48 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.52 (s, 1H, Ar–H), 7.65 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 8.02 (s, 1H, –N CH), 11.10 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 17.1, 118.7, 122.6, 124.8, 125.1, 127.1, 128.3, 129.6, 133.3, 142.8, 148.5, 152.3, 168.3; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H12N4O2S: 313.0681; found: 313.0652.

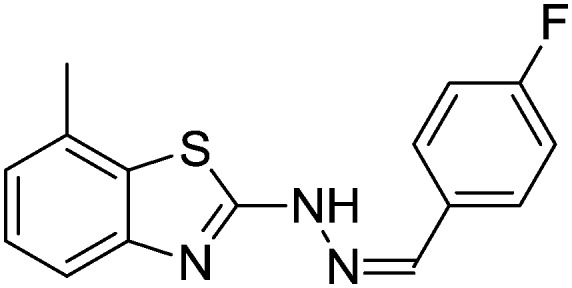

4.1.7. 2-(2-(4-Fluorobenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [4]

Yield 92.1%, off-white solid, Rf = 0.47, m.p. 177–178 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1631, 3354; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.49 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.79–6.81 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.01 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.41 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.62–7.64 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.81 (s, 1H, –N CH), 11.04 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 17.8, 115.1, 118.3, 123.0, 126.1, 127.4, 128.3, 129.9, 131.0, 144.0, 148.6, 160.7, 168.3; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H12FN3S: 286.3393; found: 286.3367.

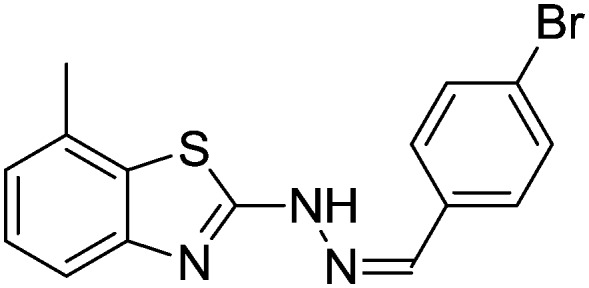

4.1.8. 2-(2-(4-Bromobenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [5]

Yield 88.41%, light yellow solid, Rf = 0.56, m.p. 191–193 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1606, 3354; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.54 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.08 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.16 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.38–7.40 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.53 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.65 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.87 (s, 1H, –N CH), 11.10 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.1, 119.4, 123.7, 125.3, 127.4, 128.0, 129.6, 130.1, 131.0, 132.4, 142.7, 147.6, 167.2; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H12BrN3S: 346.1449; found: 346.1452.

4.1.9. 4-((2-(7-Methylbenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)hydrazono)methyl)phenol [6]

Yield 85.6%, cream solid, Rf = 0.41, m.p. 166–167 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1617, 3325, 3541; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.36 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.89–6.93 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.01–7.08 (m, 3H, Ar–H), 7.19–7.22 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 7.27–7.31 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 7.36 (s, 1H, –N CH), 8.31 (s, 1H, OH), 10.8 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 17.4, 116.8, 118.1, 119.6, 122.4, 123.0, 125.0, 127.7, 130.8, 131.3, 152.8, 158.3, 166.8; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H13N3OS: 284.0813; found: 284.0869.

4.1.10. 2-(2-(4-Methoxybenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [7]

Yield 88.9%, white solid, Rf = 0.53, m.p. 157–159 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1624, 3328; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.53 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.83 (s, 3H, OCH3), 6.90 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 7.07 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.15 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.52 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 7.82 (s, 1H, –N CH), 11.0 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.1, 55.3, 114.2, 118.8, 121.9, 126.9, 127.0, 127.4, 128.4, 129.8, 144.0, 148.6, 161.0, 168.3; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C16H15N3OS: 298.2398; found: 298.2364.

4.1.11. 7-Methyl-2-(2-(4-methylbenzylidene)hydrazinyl)benzo[d]thiazole [8]

Yield 87.8%, brown solid, Rf = 0.51, m.p. 152–154 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1618, 3310; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.20 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.51 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.90–6.92 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.02 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.11 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.42 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.68–7.70 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 7.80 (s, 1H, –N CH), 10.7 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 19.2, 22.8, 119.3, 123.7, 125.0, 126.8, 127.1, 129.3, 130.4, 132.4, 139.4, 144.3, 148.7, 167.3; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C16H15N3S: 282.1020; found: 282.1031.

4.1.12. 2-(2-(2,4-Dichlorobenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [9]

Yield 86.9%, off-white solid, Rf = 0.48, m.p. 183–185 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1616, 3351; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.53 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.05 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.24–7.27 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 7.37 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.97 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 8.20 (s, 1H, –N CH), 9.82 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 17.9, 118.8, 122.4, 125.4, 127.2, 127.4, 127.7, 129.5, 130.2, 134.0, 135.6, 139.3, 147.8, 150.1, 167.6; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H11Cl2N3S: 336.0051; found: 336.0074.

4.1.13. 2-(2-(2,4-Dinitrobenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [10]

Yield 79.6%, yellow solid, Rf = 0.52, m.p. 170–171 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1620, 3310; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.54 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.90–6.91 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.07 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.13 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.41 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.65–7.67 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 7.70–7.72 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 8.01 (s, 1H, –N CH), 10.8 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.7, 118.2, 121.0, 123.4, 125.9, 127.0, 129.8, 130.7, 132.5, 135.4, 142.6, 148.6, 149.2, 151.7, 168.1; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H11N5O4S: 358.0823; found: 358.0819.

4.1.14. 2-(2-(2,4-Difluorobenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [11]

Yield 88.9%, light yellow solid, Rf = 0.40, m.p. 184–186 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1601, 3322; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.50 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.75–6.80 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 6.89–6.94 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 7.02 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.45 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.92–7.98 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 8.06 (s, 1H, –N CH), 9.11 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 17.8, 103.9, 112.0, 118.5, 122.3, 127.1, 127.7, 127.8, 129.4, 136.3, 142.6, 147.8, 159.7, 162.3, 167.6; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H11F2N3S: 304.0642; found: 304.0666.

4.1.15. 2-(2-(2,4-Dibromobenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [12]

Yield 83.6%, brown solid, Rf = 0.55, m.p. 167–169 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1612, 3314; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.52 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.82–6.84 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 7.06 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.16 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.47 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.60–7.61 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 7.70–7.71 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 7.89 (s, 1H, –N CH), 9.28 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.6, 118.1, 122.4, 123.7, 124.3, 125.8, 127.6, 129.4, 131.0, 133.7, 134.6, 136.7, 142.1, 147.9, 166.9; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H11Br2N3S: 425.1409; found: 425.1454.

4.1.16. 4-((2-(7-Methylbenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)hydrazono)methyl)benzene-1,3-diol [13]

Yield 88.1%, off-white solid, Rf = 0.29, m.p. 188–189 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1601, 3314, 3510, 3547; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.48 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.92–6.93 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 7.03 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.42 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.55–7.57 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.80 (s, 1H, –N CH), 8.90 (s, 2H, OH), 9.90 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.9, 104.8, 109.3, 111.5, 118.7, 123.2, 125.9, 127.3, 131.4, 135.2, 144.7, 148.3, 160.8, 162.3, 167.9; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H13N3O2S: 300.0762; found: 300.0715.

4.1.17. 2-(2-(2,4-Dimethoxybenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [14]

Yield 85.6%, off-white solid, Rf = 0.45, m.p. 169–170 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1612, 3549; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.51 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.85 (s, 6H, 2OCH3), 6.66–6.68 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.05 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.10 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.62–7.63 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 7.89 (s, 1H, –N CH), 11.04 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.7, 54.9, 55.4, 102.7, 106.9, 109.4, 118.7, 122.4, 125.9, 128.0, 131.4, 133.7, 142.8, 147.3, 160.4, 163.4, 167.9; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C17H17N3O2S: 328.1041; found: 328.1047.

4.1.18. 2-Methoxy-5-((2-(7-methylbenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)hydrazono)methyl)phenol [15]

Yield 91.7%, off-white solid, Rf = 0.39, m.p. 177–179 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1621, 3314, 3542; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.53 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.96 (s, 1H, OH), 3.98 (s, 3H, OCH3), 6.92 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.04–7.09 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.34 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.47 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.83 (s, 1H, –N CH), 9.82 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 17.5, 55.6, 108.5, 114.4, 118.2, 122.1, 126.2, 127.2, 128.7, 130.8, 137.3, 142.9, 145.0, 146.4, 149.7, 166.1; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C16H15N3O2S: 314.1119; found: 314.1187.

4.1.19. 2-Bromo-4-((2-(7-methylbenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)hydrazono)methyl)phenol [16]

Yield 82.6%, light yellow solid, Rf = 0.40, m.p. 158–159 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1622, 3360, 3548; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.49 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.95 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.06–7.09 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.40 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.62–7.68 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.90 (s, 1H, –N CH), 9.10 (s, 1H, OH), 11.6 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 19.0, 113.4, 117.0, 118.3, 122.8, 124.8, 127.6, 128.3, 129.4, 130.3, 132.4, 144.1, 148.3, 158.3, 167.8; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H12BrN3OS: 362.9864; found: 362.9860.

4.1.20. 2-(2-(3-Bromo-4-methoxybenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [17]

Yield 86.4%, brown solid, Rf = 0.52, m.p. 188–189 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1610, 3345; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.53 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.82 (s, 3H, OCH3), 6.90–6.92 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 7.02 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.40 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.69–7.71 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.84 (s, 1H, –N CH), 10.9 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 19.4, 54.6, 111.4, 112.7, 118.3, 123.0, 125.6, 126.8, 128.2, 128.9, 129.7, 131.6, 143.8, 148.7, 160.4, 167.9; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C16H14BrN3OS: 376.2790; found: 376.2751.

4.1.21. 2-Bromo-6-methoxy-4-((2-(7-methylbenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)hydrazono)methyl)phenol [18]

Yield 80.4%, brown solid, Rf = 0.40, m.p. 201–203 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1623, 3345, 3560; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.51 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.80 (s, 3H, OCH3), 6.87–6.88 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 7.03 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.42 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.72–7.73 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.88 (s, 1H, –N CH), 8.95 (s, 1H, OH), 11.4 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.9, 55.7, 111.7, 115.3, 119.0, 122.7, 123.6, 125.7, 127.3, 129.4, 132.7, 142.0, 144.3, 148.6, 151.7, 167.8; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C16H14BrN3O2S: 392.0024; found: 392.0324.

4.1.22. 7-Methyl-2-(2-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzylidene)hydrazinyl)benzo[d]thiazole [19]

Yield 78.6%, off-white solid, Rf = 0.46, m.p. 208–209 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1607, 3540; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.53 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.80 (s, 9H, 3OCH3), 7.03 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.11–7.15 (m, 3H, Ar–H), 7.46 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.79 (s, 1H, –N CH), 11.2 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 19.2, 55.7, 59.7, 104.7, 118.4, 122.7, 125.3, 127.8, 128.9, 132.4, 140.9, 143.7, 148.3, 151.7, 167.8; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C18H19N3O3S: 358.1181; found: 358.1189.

4.1.23. 7-Methyl-2-(2-(3,4,5-trihydroxybenzylidene)hydrazinyl)benzo[d]thiazole [20]

Yield 77.6%, off-white solid, Rf = 0.32, m.p. 212–214 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1627, 3349, 3540, 3556; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.51 (s, 3H, CH3), 5.28 (s, 2H, OH), 6.84–6.86 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.06 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.14 (s, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.41 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.89 (s, 1H, –N CH), 9.20 (s, 1H, OH), 11.3 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.6, 108.7, 119.1, 122.8, 125.7, 127.6, 129.6, 133.1, 142.6, 144.7, 148.1, 148.7, 168.9; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H13N3O3S: 316.0711; found: 316.0726.

4.1.24. 7-Methyl-2-(2-(4-phenoxybenzylidene)hydrazinyl)benzo[d]thiazole [21]

Yield 90.7%, light yellow solid, Rf = 0.56, m.p. 193–195 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1604, 3360; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.45 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.08–7.14 (m, 6H, Ar–H), 7.46–7.50 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 7.72–7.76 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.91 (s, 1H, –N CH), 10.81 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 19.2, 117.2, 118.4, 119.6, 121.4, 123.4, 125.9, 126.4, 128.1, 128.9, 130.4, 131.4, 143.8, 148.9, 156.4, 160.7, 168.7; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C21H17N3OS: 360.1126; found: 360.1195.

4.1.25. 2-(2-(4-Benzyloxy-3-methoxybenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [22]

Yield 82.4%, off-white solid, Rf = 0.53, m.p. 162–163 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1620, 3360; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.50 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.96 (s, 3H, OCH3), 5.19 (s, 2H, CH2), 6.87 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.04 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.29–7.39 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 7.44 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, Ar–H), 7.87 (s, 1H, –N CH), 9.69 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.0, 21.5, 55.9, 70.9, 108.9, 113.4, 118.8, 121.3, 122.1, 126.9, 127.2, 127.5, 127.9, 128.4, 128.5, 131.5, 136.7, 144.9, 149.9, 168.3, 177.0; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C23H21N3O2S: 404.1354; found: 404.1359.

4.1.26. 7-Methyl-2-(2-(pyridin-4-ylmethylene)hydrazinyl)benzo[d]thiazole [23]

Yield 90.8%, off-white solid, Rf = 0.42, m.p. 151–152 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1619, 3344; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.53 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.09 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.16 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.50 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.54 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 7.83 (s, 1H, –N CH), 8.61 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, Ar–H), 11.7 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 17.8, 118.9, 120.7, 122.7, 125.4, 127.1, 131.4, 141.0, 141.4, 148.7, 150.2, 169.4; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C14H12N4S: 269.0783; found: 269.0756.

4.1.27. 7-Methyl-2-(2-(3-methylbutylidene)hydrazinyl)benzo[d]thiazole [24]

Yield 82.6%, light yellow solid, Rf = 0.44, m.p. 170–171 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1612, 3334; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 0.97 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H, (CH3)3), 1.85–1.91 (m, 1H, CH), 2.20 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.56 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.03 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.20 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.47 (d, 1H, –N CH), 11.1 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.0, 23.3, 26.7, 40.9, 118.6, 121.8, 123.7, 125.7, 126.7, 131.4, 146.9, 169.4; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C13H17N3S: 248.1143; found: 248.1160.

4.1.28. 7-Methyl-2-(2-propylidenehydrazinyl)benzo[d]thiazole [25]

Yield 86.4%, off-white solid, Rf = 0.49, m.p. 142–143 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1604, 3318; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 1.11 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 2.29–2.34 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.50 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.03 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.23 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.47 (s, 1H, –N CH), 11.12 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 10.7, 18.3, 25.7, 118.6, 121.4, 126.6, 127.1, 129.7, 149.2, 150.6, 167.3; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C11H13N3S: 219.0830; found: 219.0877.

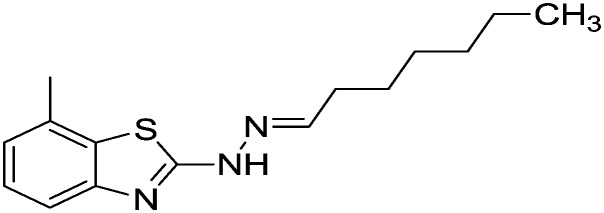

4.1.29. 2-(2-Heptylidenehydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [26]

Yield 80.4%, off-white solid, Rf = 0.56, m.p. 150–152 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1610, 3345; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 0.91 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.20–1.35 (m, 8H, (CH2)4), 1.67–1.69 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.53 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.10 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.15 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.44 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.91 (s, 1H, –N CH), 10.89 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 15.2, 19.2, 20.7, 23.4, 26.7, 29.3, 31.0, 119.1, 123.5, 125.6, 127.3, 132.5, 144.0, 148.6, 168.9; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C15H21N3S: 276.1490; found: 276.1453.

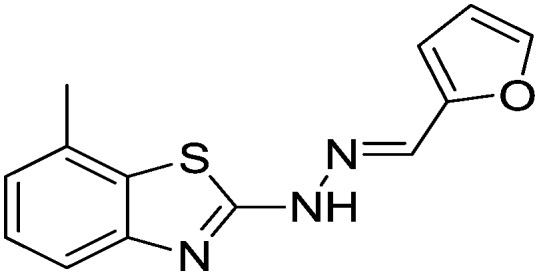

4.1.30. 2-(2-(Furan-2-ylmethylene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [27]

Yield 91.2%, cream solid, Rf = 0.51, m.p. 164–166 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1619, 3365; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.52 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.65–6.72 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.02 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.41 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.71–7.72 (m, 1H, Ar–H), 7.86 (s, 1H, –N CH), 10.99 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.6, 112.7, 118.5, 119.3, 123.0, 125.1, 127.3, 132.4, 141.7, 144.5, 148.7, 150.1, 168.7; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C13H11N3OS: 258.0656; found: 258.0621.

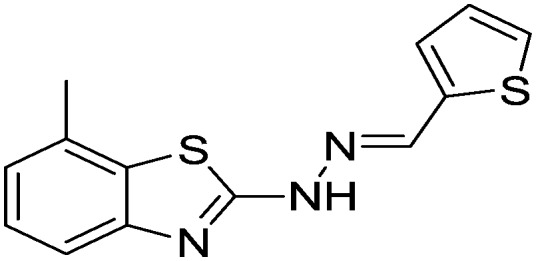

4.1.31. 7-Methyl-2-(2-(thiophen-2-ylmethylene)hydrazinyl)benzo[d]thiazole [28]

Yield 85.6%, off-white solid, Rf = 0.49, m.p. 187–190 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1601, 3214; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.46 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.06 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.12–7.15 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.38 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.68–7.70 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.89 (s, 1H, –N CH), 9.89 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 19.2, 118.3, 123.7, 125.1, 126.7, 127.9, 128.6, 129.7, 133.5, 137.9, 142.8, 148.6, 167.3; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C13H11N3S2: 274.0428; found: 274.0454.

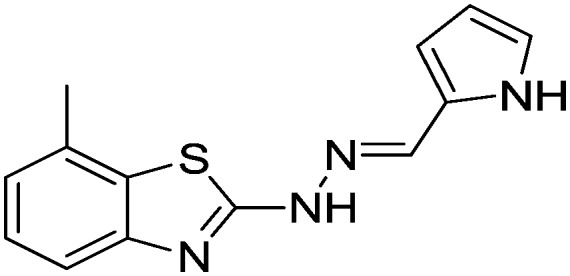

4.1.32. 2-(2-(1H-Pyrrol-2-ylmethylene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [29]

Yield 81.6%, brown solid, Rf = 0.42, m.p. 210–211 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1612, 3345, 3348; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.53 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.60–6.72 (m, 3H, Ar–H), 7.04 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.15 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.44 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.90 (s, 1H, –N CH), 9.89 (s, 1H, NH), 11.20 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 19.1, 110.7, 118.6, 119.4, 122.7, 124.6, 125.9, 127.6, 131.4, 133.5, 140.8, 148.6, 169.7; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C13H12N4S: 257.0816; found: 257.0841.

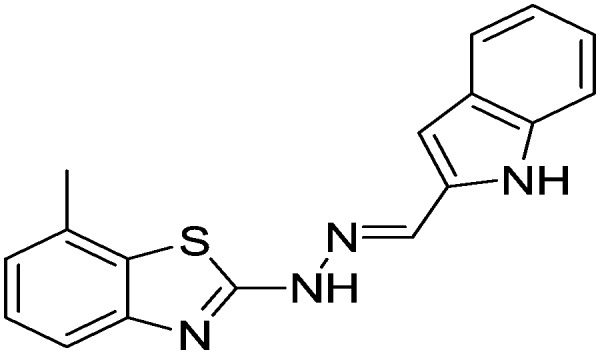

4.1.33. 2-(2-(1H-Indol-2-ylmethylene)hydrazinyl)-7-methylbenzo[d]thiazole [30]

Yield 82.6%, light yellow solid, Rf = 0.45, m.p. 196–198 °C, IR KBr (cm–1): 1610, 3214, 3342; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 2.49 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.86–6.92 (m, 3H, Ar–H), 7.07 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.17 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.41 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 7.61–7.65 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.81 (s, 1H, –N CH), 10.81 (s, 1H, NH), 11.26 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm: 18.4, 101.4, 112.7, 118.7, 119.6, 120.7, 121.4, 122.9, 123.5, 126.7, 127.3, 128.4, 131.6, 133.4, 141.6, 148.9, 168.9; HRMS m/z [M + 1]: calcd for C17H14N4S: 307.3849; found: 307.3856.

5. Biological activity

5.1. Gastric H+/K+ ATPase activity

Isolation of parietal cells from sheep stomach

The fundic portion of a sheep stomach was collected soon after sacrifice and rinsed with Krebs Ringer buffer (250 mM sucrose, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA and 2 mM Hepes-Tris of a pH of 7.4). The upper layer was pinned with the help of needles on a dissection table. Mucosal scrapings were suspended in 10 volumes of Krebs Ringer buffer (pH = 7.4) containing sucrose (250 mM) and homogenized by 20 strokes of a mortar-driven Teflon pestle homogenizer. The tissues were discarded and the filtrate was subjected to subcellular fractionation. The pellets obtained were dissolved in 2 mL sucrose-EGTA buffer and used as an enzyme sample.

Protein estimation

The protein content was calculated using the Lowry method,34 and bovine serum albumin was used as a standard (0–75 μg). Eight clean and dry test tubes were taken and aliquots of various concentrations of the synthesized derivatives were prepared. To the 7th and 8th test tubes were added unknown samples (5 μL and 10 μL of cells isolated from the sheep stomach), for which the protein content was to be determined. In every test tube, the solution was made up to 1 mL by the addition of distilled water, followed by the addition of 5 mL Lowry's reagent. All the test tubes were incubated at RT for 8–10 min, and then 0.5 mL Folin–Ciocalteu reagent was added and the tubes were again incubated at RT for 30 min. The absorbance of each solution was recorded at 670 nm against a blank solution. A graph was plotted using the concentration of protein on the X-axis and OD on the Y-axis. From the standard graph obtained, the concentration of protein in the unknown sample was calculated, and it was found to contain 21 mg protein per 8 g tissue homogenate.

Inorganic phosphorus estimation

Inorganic phosphorus was estimated according to the Fiske Subbarow method.35 Aliquots of a working standard solution (40 μg mL–1) were added to 8 fresh and dry test tubes in volumes of 0 to 1 mL, and 5 μL and 10 μL of the enzyme sample were added to the 7th and 8th test tubes, respectively. The volumes of all solutions were made up to 8.6 mL using 10% TCA. Ammonium molybdate (1 mL) and ANSA reagent (0.4 mL) were added to all test tubes. All test tubes were allowed to stand for 10 min at RT. Then the color was developed and the λmax value at 660 nm was recorded.

5.2. ATPase activity

ATPase activity was determined using a reported method.36 The basal activity of Mg2+-dependent ATPase was calculated in 1 mL reaction mixture comprising 2 mmol L–1 ATP and 50 mmol L–1 Tris-HCl buffer (pH = 7.5). The activities of K+-stimulated and HCO3–-stimulated ATPase were tested in basal medium. The ATPase reaction was started by the addition of the substrate (ATP), carried out at 37 °C for 10–15 min and then terminated by the addition of 1 mL cold 20% TCA. The amount of inorganic phosphate liberated from ATP was estimated using the literature method.36

The activity of the enzyme sample in the presence of ATP was 0.066 μmol.

The activity of the enzyme sample in the absence of ATP was 0.042 μmol.

100% activity of the enzyme was 0.066 μmol – 0.042 μmol = 0.024 μmol.

5.3. Anti-inflammatory activity

Human erythrocyte suspension

Human blood was collected in a heparinized vacutainer from a healthy volunteer who had not taken any NSAIDs for 2 weeks before the experiment. The collected healthy human blood was washed with 0.9% saline and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3000 rpm. The packed cells were washed with 0.9% saline, and a 40% (v/v) suspension was prepared with isotonic phosphate buffer of 154 mM NaCl in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at a pH of 7.4 and used as a stock erythrocyte (RBC) suspension.

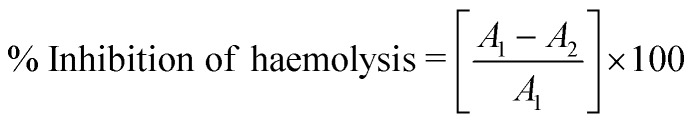

Hypotonic solution-induced haemolysis

The activity of the synthesized compounds was tested according to a reported method.28 The tested samples, which consisted of 0.5 mL stock erythrocyte (RBC) suspension, 5 mL hypotonic solution (50 mM NaCl in 10 mM sodium phosphate-buffered saline at a pH of 7.4) and samples of different concentrations (20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 μg mL–1), were prepared. The blank control consisted of 0.5 mL mixed RBC suspension and 5 mL hypotonic buffered solution alone. The mixtures were incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3000 rpm, and the supernatant was measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm. The percentage inhibition of haemolysis was calculated according to the following formula: where: A1 = absorbance of hypotonic buffered solution alone; and A2 = absorbance of test/standard sample in hypotonic solution.

where: A1 = absorbance of hypotonic buffered solution alone; and A2 = absorbance of test/standard sample in hypotonic solution.

5.4. Molecular docking and ADME predictions

The coordinates of COX-2 and H+/K+ ATPase were obtained from the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank, and their PDB IDs are ; 1PXX and ; 2ZXE, respectively. The ligands were drawn using Maestro 2D sketcher, and energy minimization was performed with OPLS 2005. Protein structures were obtained by retrieval from the Maestro platform (Schrödinger, Inc.). Protein structures were corrected using the Schrödinger Prime software module to correct the missing loops in the protein. Water molecules in COX-2 and H+/K+ ATPase were removed beyond 5 Å from the respective heteroatom. Water molecules that were thought to be important in aiding the interaction with the receptor were optimized using Protein Preparation Wizard. Necessary bonds, bond orders, hybridization, explicit hydrogens and charges were assigned automatically. The OPLS 2005 force field was applied to the protein to restrain minimization, and an RMSD of 0.30 Å was set to converge heavy atoms during preprocessing of the protein before docking was started. Using extra-precision (XP) docking and scoring, each compound was docked into a receptor grid of dimensions of 20 Å × 20 Å × 20 Å, and the docking calculations were judged on the basis of the Glide score, ADME results and Glide energy. The prediction program QikProp was used to calculate the ADME properties of all the ligands, and molecular visualization was performed in the Maestro workspace.37

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China for financial support. The authors are also thankful to the management of SRI RAM CHEM (India) for their continuous encouragement towards the research.

Footnotes

†The authors declare no competing interests.

‡Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c7md00111h

References

- Gustavsson S., Adam H. O., Loof L. Lancet. 1983;8342:124–125. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakesh K. P., Shantharam C. S., Manukumar H. M. Bioorg. Chem. 2016;68:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurumbail R. G., Stevens A. M., Gierse J. K., McDonald J. J., Stegeman R. A., Pak J. Y., Gildehaus D. Nature. 1996;384:644–648. doi: 10.1038/384644a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G., Fischer J., Kis-Varga A., Gyires K. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:142–147. doi: 10.1021/jm070821f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rodriguez L. A., Hernández-Diaz S. Epidemiology. 2003;14:240–246. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000034633.74133.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K., Kaneko Y., Suwa K., Ebara S., Nakazawa K., Yasuno K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:2509–2522. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger A., Sawhey S. N. J. Med. Chem. 1968;11:270–273. doi: 10.1021/jm00308a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui N., Rana A., Khan S. A., Bhat M. A., Haque S. E. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;15:4178–4182. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cressier D., Prouillac C., Hernandez P., Amourette C., Diserbo M., Lion C., Rima G. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:5275–5284. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafi S., Alam M. M., Mulakayala N., Mulakayala C., Vanaja G., Kalle A. M., Pallu R., Alam M. S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;49:324–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X., Yan Y., Zhu N., Liu G. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;76:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo F., Romeo G., Santagati N. A., Caruso A., Cutuli V., Amore D. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1994;29:569–578. [Google Scholar]

- Telvekar V. N., Bairwa V. K., Satardekar K., Bellubi A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:649–652. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay S. P., Kamalakar P. N., Sougata G., Rao V. J., Chopade B. A., Sridhar B., Bhosale S. V., Bhosale S. V. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;59:304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwan A., Palewicz M., Krompiec M., Grucela-Zajac M., Schab-Balcerzak E., Sikora A. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A. 2012;97:546–555. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwan A., Siwy M., Janeczek H., Rannou P. Phase Transitions. 2012;85:297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Rakesh K. P., Manukumar H. M., Gowda D. C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:1072–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakesh K. P., Ramesha A. B., Shantharam C. S., Mantelingu K., Mallesha N. RSC Adv. 2016;6:108315–108318. [Google Scholar]

- Qin H.-L., Shang Z.-P., Jantan I., Tan O. U., Hussain M. A., Sher M., Bukhari S. N. A. RSC Adv. 2015;5:46330–46338. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar G. B., Bukhari S. N. A., Qin H.-L. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2017;89:634–638. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaram N. S., Musalam L., Ali H. M., Abdulla M. A. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2012;11:251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Alafeefy A. M., Bakht M. A., Ganaie M. A., Ansarie M. N., El-Sayed N. H., Awaad A. S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.11.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizian H., Mousavi Z., Faraji H., Tajik M., Bagherzadeh K., Bugat P., Shafice A., Almasirad A. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2016;67:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari S. V., Bothara K. G., Raut M. K., Patil A. A., Sarkate A. P., Mokale V. J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:1822–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P., Kumar A., Kumari P., Singh J., Kaushik M. P. Med. Chem. Res. 2012;21:1136–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Hamprecht R., US Pat., 4808723, 1989.

- Sharma A., Suhas R., Chandana K. V., Banu S. H., Gowda D. C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;14:4096–4098. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde U. A., Phadke A. S., Nair A. M., Mungantiwar A. A., Dikshit V. J., Saraf M. N. Fitoterapia. 1999;70:251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Vivek H. K., Supritha G. S., Priya B. S., Sethi G., Rangappa K. S., Swamy S. N. Anal. Biochem. 2014;461:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2014.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballinger A., Smith G. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2001;2:31–40. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameshwar V. H., Kumar J. R., Priya B. S., Swamy S. N. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2017;426:161–175. doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2888-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Huang N., Wang J., Luo H., He H., Ding M., Deng W. Q., Zou K. Fitoterapia. 2013;89:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C. A., Lombardo F., Dominy B. W., Feeney P. J. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry O. H., Rosebrough N. J., Farr A. L., Randall R. J. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske C. H., Subbarow Y. J. Biol. Chem. 1952;66:375–400. [Google Scholar]

- Im W. B., Sih J. C., Blakeman D. P., McGrath J. P. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:4591–4597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesner R. A., Banks J. L., Murphy R. B., Halgren T. A., Klicic J. J., Mainz D. T., Repasky M. P. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.