Small-molecule inhibition of Keap1–Nrf2 protein–protein interactions as a novel approach to activate Nrf2.

Small-molecule inhibition of Keap1–Nrf2 protein–protein interactions as a novel approach to activate Nrf2.

Abstract

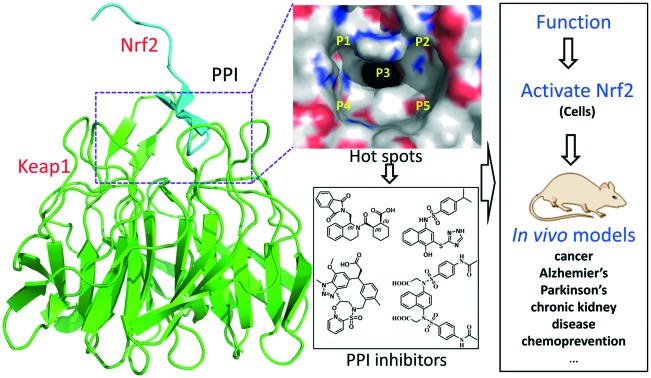

Oxidative stress is well recognized to contribute to the cause of a wide range of diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, arteriosclerosis, and inflammation. The Keap1–Nrf2–ARE pathway plays a critical regulatory role and can protect cells from oxidative stress through activating Nrf2 to induce its downstream phase II enzymes. Nrf2 activation through the covalent inactivation of Keap1 may cause unpredictable side effects. Non-covalent disruption of the Keap1–Nrf2 protein–protein interactions is an alternative strategy for Nrf2 activation, potentially with reduced risk of toxicity. Efforts have been made in recent years to develop peptide- and small molecule-based Keap1–Nrf2 PPI inhibitors via different approaches, including high-throughput screening, target-based virtual screening, structure-based optimization, and fragment-based drug design. This review aims to highlight the recently discovered small-molecule inhibitors as well as their therapeutic potential.

1. Introduction

The human body is continuously exposed to internal and external reactive oxidants and electrophiles,1 which contribute to the aetiology of various diseases, including cancers,2 diabetes,3 Alzheimer's disease,4,5 arteriosclerosis,6,7 inflammatory diseases,8 and the process of normal aging.9–11 The antioxidant defense system is the key mechanism to protect cells from these oxidative and electrophilic chemicals. A number of phase II enzymes, such as NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO-1), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), glutamate–cysteine ligase (GCL), catalase, thioredoxin (TRX) and glutathione S-transferase (GST), are the major components of this defense system.12,13 Typically, these phase II enzymes are transcriptionally regulated by their upstream antioxidant response element (ARE).14 Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is the key ARE-binding transcription factor.15 Numerous studies have confirmed the protective role of Nrf2 in preventing oxidative stress.16 Nrf2 remains at a low cellular concentration under unstressed conditions and is negatively regulated by the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) via proteasome-mediated degradation.15 Upon oxidative stress, Keap1 is deactivated so that Nrf2 escapes from Keap1-mediated degradation and translocates into the nucleus to transcriptionally activate the ARE-dependent antioxidant genes. It is, therefore, a reasonable strategy to target the Keap1–Nrf2–ARE signalling pathway for the discovery of therapeutic agents against oxidative stress-mediated diseases.17–19

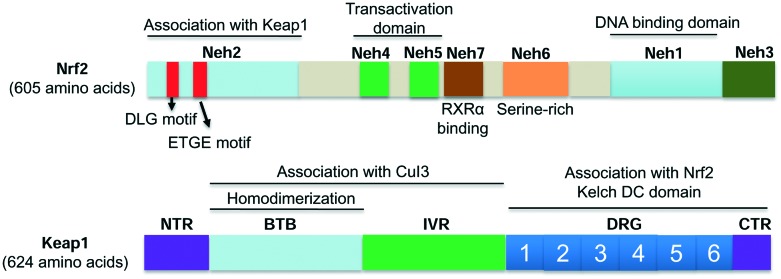

Nrf2 is composed of 605 amino acids with seven highly conserved domains (namely Neh1 to Neh7, Fig. 1).20 Each domain plays distinct roles for Nrf2 functions. Neh1 contains a basic leucine zipper motif that forms heterodimers with DNA, the small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (Maf) protein, or other transcription partners. Neh2 contains two motifs known as DLG and ETGE, which are essential for the interactions between Keap1 and Nrf2 that regulate Nrf2 ubiquitination and stability.21,22 Neh3 is critical for the transactivation of the ARE-dependent genes.23 Neh4 and Neh5 bind the CH3 motif of the CREB-binding protein (CBP), a transcriptional co-activator that mediates Nrf2 transcriptional activity.24 Neh6, a serine-rich domain, controls the stability of Nrf2 in a Keap1-independent manner.25 Neh7 interacts with retinoic X receptor alpha (RXRα) and inhibits the Nrf2–ARE signalling pathway.20,26

Fig. 1. The protein domains of Nrf2 and Keap1.

Keap1, the key suppressor of Nrf2, is a cysteine-rich protein.27 Seven of its cysteines (Cys151, Cys257, Cys273, Cys288, Cys297, Cys434, and Cys613) have been confirmed to be involved in redox sensing and Nrf2 activation.15,28,29 Human Keap1 contains five domains (Fig. 1): a N-terminal region (NTR), a BTB domain, an intervening region (IVR) with several cysteines, a double glycine region (DGR) and a C-terminal region (CTR).30,31 The BTB domain could dimerize with Cullin3 (Cul3), which is responsible for Nrf2 ubiquitination.32 The IVR domain has highly reactive cysteines that serve as sensors to oxidative stress.33 The DGR domain comprises six repetitive Kelch motifs. The DGR and CTR domains, together named as the DC domain, bind to Neh2 of Nrf2 to mediate the interactions between Keap1 and Nrf2.15,22,30

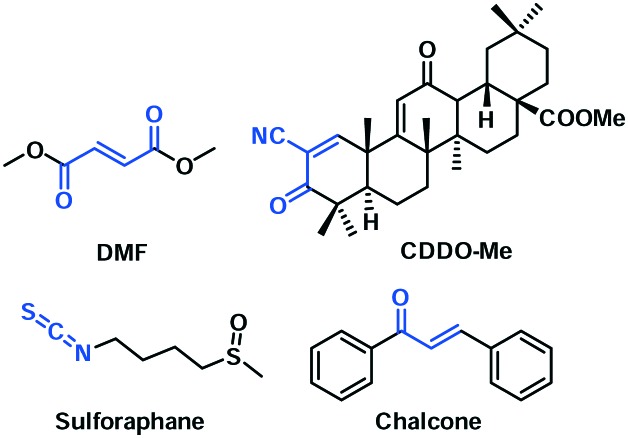

Based on the structural and mechanistic knowledge of the Keap1–Nrf2 system, many Nrf2 activators have been developed as potential therapeutics. They could be broadly divided into two categories according to their mechanisms of action. Electrophilic agents can induce Nrf2 activation through covalent modification of Keap1 via its reactive cysteines, resulting in Keap1 conformational changes and the subsequent release of Nrf2. Dimethyl fumarate (DMF) and bardoxolone methyl (CDDO-Me) are the representatives from this category, which are currently in clinical evaluation (Fig. 2). Sulforaphane and chalcones are other examples in this category. A few excellent reviews have covered the recent progress of this class of Nrf2 activators.17–19,34–36 These electrophile-based Nrf2 activators, besides covalently modifying Keap1, have the potential to react with other proteins and may cause unpredictable side effects.18 Alternatively, Nrf2 can be activated via a non-covalent inhibition of Keap1–Nrf2 protein–protein interactions,17–19,30,37 which may result in a better safety profile.19,38 Although several peptide-based inhibitors have been rationally designed based on the structure of the Keap1–Nrf2 complex,39–42 they typically lack in vivo activity, potentially due to a poor bioavailability. This review aims to highlight the recently discovered small-molecule inhibitors (2012–2016) and their therapeutic potential, which are organized based on their discovery strategies.

Fig. 2. Representative covalent Nrf2 activators with the electrophilic functional groups highlighted in blue.

2. Strategies in discovering small-molecule Keap1–Nrf2 PPI inhibitors

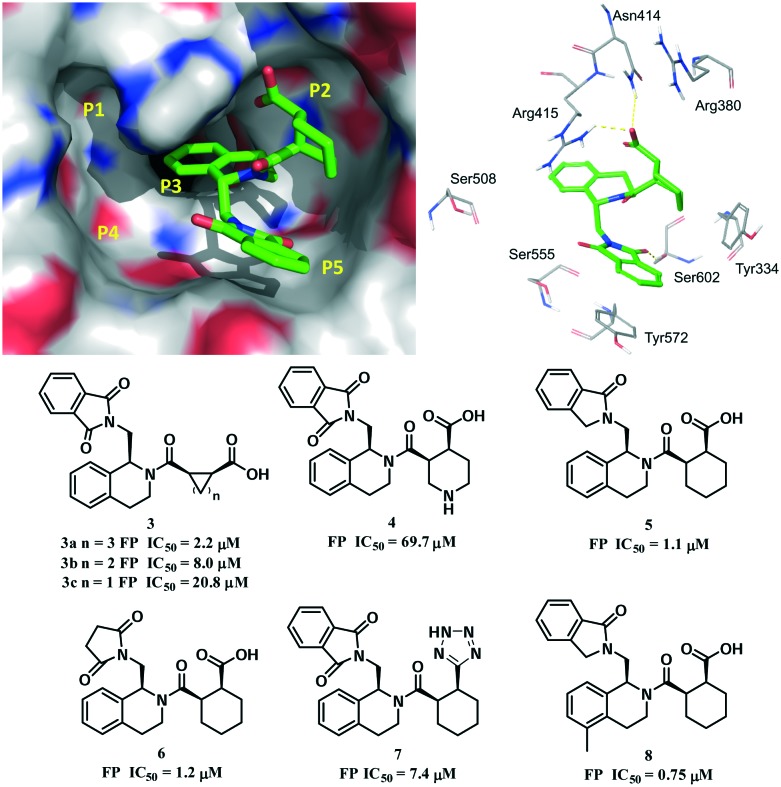

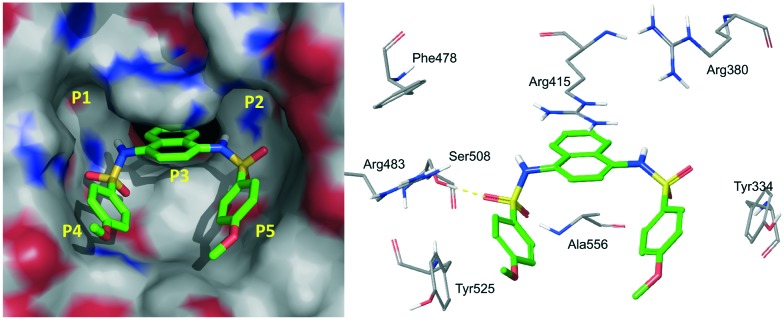

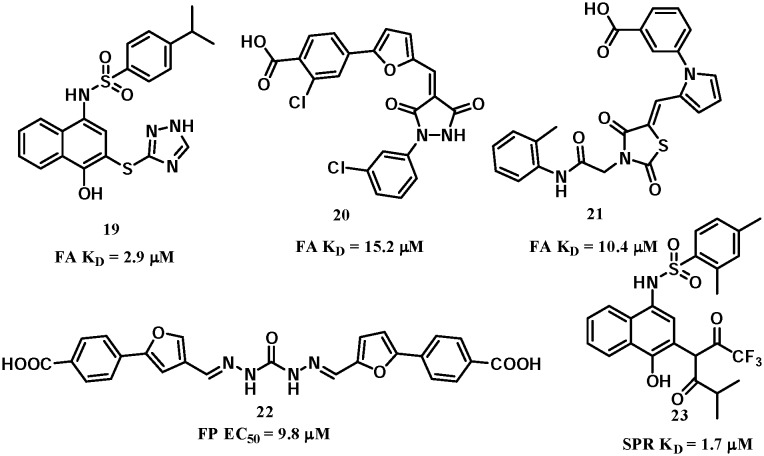

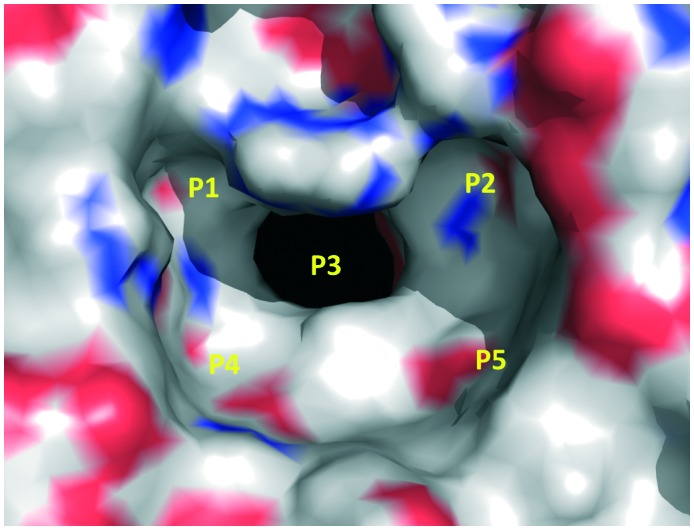

The X-ray structure of the Keap1 Kelch domain with Nrf2 was recently determined,30,43,44 which serves as the knowledge basis for the design of small-molecule PPI inhibitors.45,46 You et al. divided the binding cavity of the Keap1 protein into five “hot spots” (P1–P5, Fig. 3), based on MD simulations and MM-GBSA free energy calculations.47,48 P1 and P2 are the polar ones and P4 and P5 are the non-polar ones. P3 is formed by the 6-bladed fold symmetry of the protein and can create steric hindrance to PPI inhibitors.48

Fig. 3. Five hot spots of the Keap1 binding cavity.

Several strategies, including high-throughput screening and structure-based optimization, target-based virtual screening, and fragment-based drug design, have been utilized to discover small-molecule Keap1–Nrf2 PPI inhibitors, which will be discussed herein, respectively.

2.1. High-throughput screening and structure-based optimization

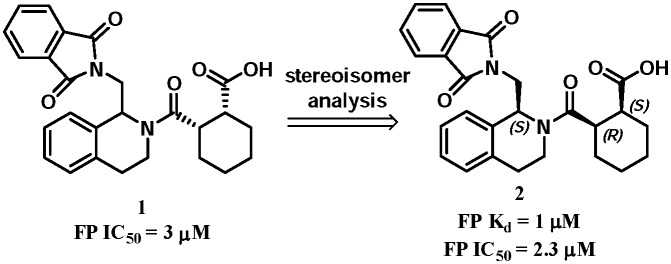

The 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) scaffold was reported as the first small-molecule Keap1–Nrf2 PPI inhibitor (Fig. 4). Compound 1 was identified by a fluorescent polarization (FP) based high-throughput screening of 337 116 compounds in the NIH MLPCN library (PubChem BioAssay ID: 504523, 504540).49 The FP assay results showed that compound 1 has an IC50 value of 3 μM. Further evaluation of the eight isomers identified the SRS-stereoisomer 2 as the lead with a KD value of 1 μM. Functional assay showed that compound 2 could induce downstream ARE activation in HepG2 cells with an EC50 value of 18 μM and promote the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 with an EC50 of 12 μM.

Fig. 4. The tetrahydroisoquinoline Keap1–Nrf2 inhibitors by high-throughput screening.

The co-crystal structure of the Kelch domain and compound 2 revealed that compound 2 occupied the P2, P3 and P5 pockets (PDB code: ; 4L7B, Fig. 5).50 In the P2 pocket, the carboxyl group of 2 formed two hydrogen bonds with Asn414 and Arg415. The THIQ core is located in the central P3 pocket and formed hydrophobic interactions with the side chains of Arg415 and Ala556. The guanidine of Arg415 interacted with the core ring of compound 2via a π–cation interaction. The cyclohexane ring inserted into the P5 pocket and hydrophobically interacted with Tyr334. The phenyl ring of the phthalimide group formed a π–π stacking interaction with Tyr572. A hydrogen bond was formed between the carbonyl group of 2 and Ser602. Structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies showed that (a) the five-membered ring compound 3a had a similar activity (IC50 = 2.2 μM) while further reduction of the ring size was unfavourable (compounds 3b–3c); (b) introduction of a nitrogen atom into the six-membered ring decreased the activity (compound 4); (c) one carbonyl group of the phthalimide could be reduced and the phenyl ring could be removed without decreasing the activity (compounds 5 and 6); (d) the replacement of the acid function with a tetrazole group (compound 7) decreased the potency; and (e) introducing a methyl group at the 5-position (compound 8) increased the potency, suggesting some steric tolerance of the P3 pocket.

Fig. 5. Co-crystal structure of compound 2 with the Keap1 protein (PDB code: ; 4L7B) and the structure–activity relationship of representative tetrahydroisoquinoline inhibitors.

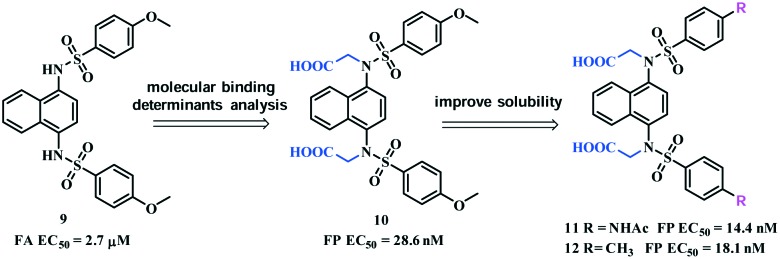

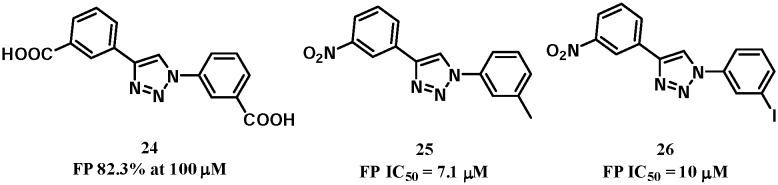

The 1,4-diaminonaphthalene compounds were another series of inhibitors discovered via a high-throughput screening using a homogeneous confocal fluorescence anisotropy (FA) assay.51 The initial hit 9 had an EC50 value of 2.7 μM. The co-crystal complex of compound 9 and the Keap1 protein revealed that the compound symmetrically occupied the P3, P4 and P5 subpockets (PDB code: ; 4IQK, Fig. 6). The naphthalene ring deeply inserted into the P3 pocket. One of the sulfamides formed a hydrogen bond with Ser508 and the 4-methoxylphenyl rings hydrophobically interacted with P4 and P5 and formed a π–π stacking interaction with Tyr334 that contributed to its potency. This compound showed a comparable dose-response activity as DMF (structure shown in Fig. 2) in an Nrf2 specific ARE-driven luciferase cell reporter assay.51

Fig. 6. Co-crystal structure of compound 9 with the Keap1 protein (PDB code: ; 4IQK).

This scaffold has attracted a lot of interest to search for more potent Keap1–Nrf2 inhibitors. Based on MD simulations and MM-GBSA free energy calculations, You et al. identified P1 and P2 as the hot spots that could be filled with polar functional groups. Arg415 in P1 and Arg483 and Ser508 in P2 were found to be the determinants for binding.48 Based on these, compound 10 (Fig. 7) was designed by introducing symmetric acetic acid groups on the amino groups. The FP assay demonstrated that compound 10 potently inhibited the Keap1–Nrf2 interactions (EC50 = 28.6 nM). This compound also dose-dependently activated Nrf2-mediated transcription in a cell-based ARE-luciferase reporter assay.

Fig. 7. Structures of compounds 9–12 and their optimization strategies.

Compound 10 was further optimized to improve its drug-like properties,52 given its poor water solubility at pH = 7.4 (388 μg mL–1) that is unsuitable for the in vivo experiment. You et al. identified two analogues, compounds 11 and 12 (Fig. 7), with improved binding activities with the Keap1 protein. Compound 11 showed greatly improved water solubility (5000 μg mL–1) and was >10-fold more active than compound 10 in Nrf2 induction at 20 μM. Compound 11 also significantly reduced the levels of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines in a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-challenged mouse model. This is the first example of small-molecule Keap1–Nrf2 PPIs in the treatment of inflammatory diseases in vivo.

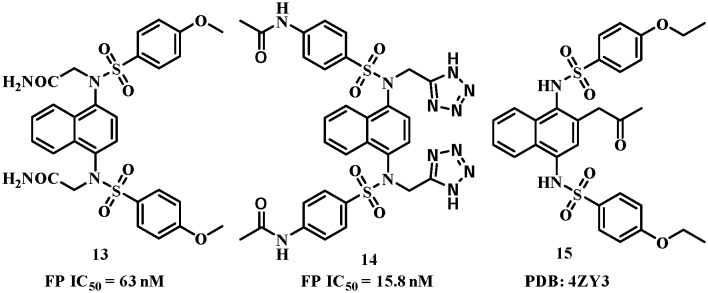

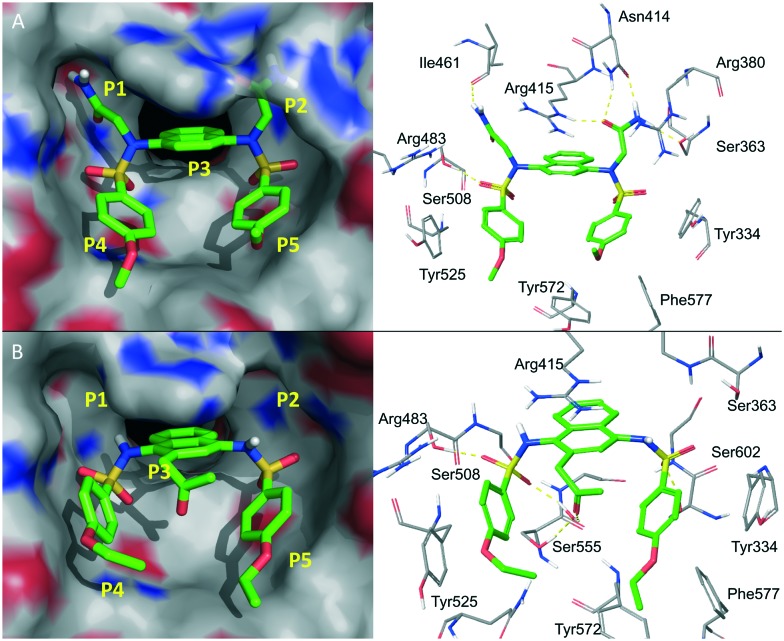

The excellent potency of the diacetic compounds was later confirmed by another group independently.53 They reported that compound 13 (Fig. 8) potently inhibited Keap1–Nrf2 interactions with an IC50 value of 63 nM. The co-crystal complex (PDB code: ; 4XMB, Fig. 9A) confirmed the five hot spots predicted by You et al.48 and the diamide group, located in the P1 and P2 pockets, formed several hydrogen bonds with Ser363, Arg380, Asn414, Arg415 and Ile461, responsible for the high potency. Very recently, You et al.54 published a follow-up work on the SAR study of the polar recognition group. Compound 14 with tetrazole groups as bioisosteric replacements was demonstrated to retain the inhibitory activity with a better pKa (5.12), log D(pH = 7.4) (2.31) and transcellular permeability than compound 11 (pKa = 4.79, log D(pH = 7.4) = 1.02). Compound 14 also showed better efficacy in inducing Nrf2 downstream genes.

Fig. 8. Structures of compounds 13–15.

Fig. 9. Co-crystal structures of compounds 13 (A, PDB code: ; 4XMB) and 15 (B, PDB code: ; 4ZY3) with the Keap1 protein.

The 1,4-diaminonaphthalene scaffold has also been reported to inhibit the interactions between Keap1 and phospho-p62, which binds to the same pocket at the bottom surface of the Kelch domain (PDB code: 4ZY3, Fig. 9B).55 The lead compound 15 had a very similar binding mode to compound 9 and the propionyl group formed water-mediated hydrogen bonds with the side chains of Ser555 and Arg415. Systematic biological studies demonstrated the therapeutic potential of compound 15 against hepatitis C virus (HCV)-positive hepatocellular carcinoma.

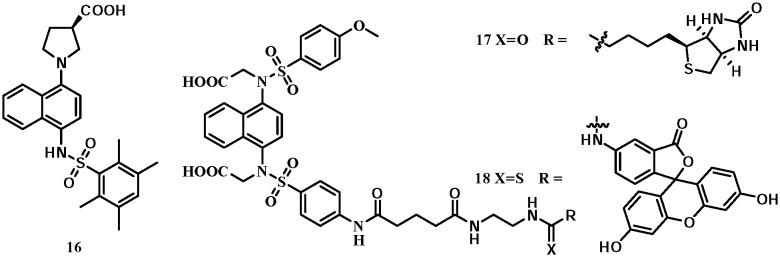

A naphthylpyrrolidine-3-carboxylic acid (compound 16, Fig. 10), namely RA839, was identified by Winkel et al. as a Keap1–Nrf2 inhibitor with an IC50 of 0.14 μM using an FP assay. The co-crystal structure (PDB code: ; 5CGJ) showed a similar binding mode to compound 9: the naphthalene inserted into the central P3 pocket and formed a π–cation interaction with Arg415. The carboxylic group formed a key hydrogen bond with Arg483. The hepatic mRNA levels of the Nrf2 target genes, GCLC and NQO1, were significantly induced by RA839 in a mouse model.56 The 1,4-diaminonaphthalene scaffold has been used to develop small-molecule chemical probes targeting Keap1.57 A fluorescein or biotin functional group was introduced, positioning towards the outside of the P4 or P5 pocket, which could tolerate large functional groups, leading to probes 17 and 18. Both compounds had high inhibitory potencies of Keap1–Nrf2 interactions. Probe 18 has also been used to visualize Keap1 in NCM460 colonic cells.

Fig. 10. Structures of compounds 16–18.

2.2. Target-based virtual screening

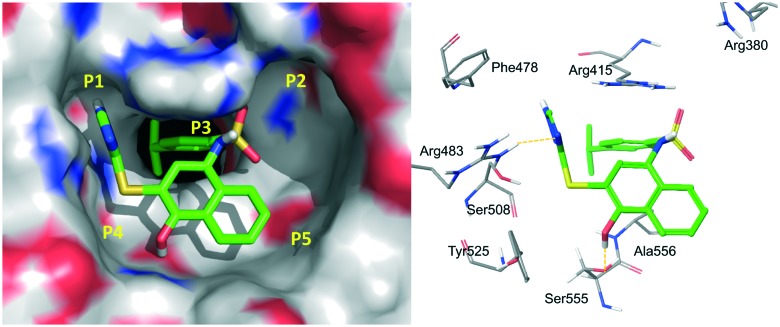

Virtual screening is a complementary approach to HTS for hit identification from commercially available or in-house chemical libraries,58 including structure/target-based59 and ligand-based60in silico screening. In 2014, a hierarchical virtual screening approach was developed by our group.61 Target-based virtual screening of a commercial chemical database was carried out followed by a hit-based substructure search of the database to establish a preliminary SAR prior to focused medicinal chemistry work. With this approach, three classes of novel inhibitors were identified with informative SARs (Fig. 11). The lead candidates showed promising inhibitory activities against Keap1–Nrf2 interactions, with KD values of 2.9 μM, 15.2 μM and 10.4 μM for compounds 19–21, respectively. Compound 22 (Fig. 11) was later independently discovered by another target-based virtual screening from the Specs database with an EC50 of 9.8 μM in an FP assay and showed cellular activities in an ARE-luciferase reporter assay.62

Fig. 11. Structures of compounds 19–23.

Docking of compound 19 in Keap1 showed that the compound occupied the P1, P3 and P4 subpockets (Fig. 12).61 Its p-isopropyl phenyl ring formed a π–cation interaction with Arg415 and inserted into the pore of the P3 pocket. The hydroxyl group formed a key hydrogen bond with Ser555 and could not be substituted with a methyl group. Moreover, a salt bridge interaction may be formed between the negatively charged triazole with Arg483. An acetate group retained the binding activity but not heterocyclic rings without a negative charge. The SAR also showed that the naphthyl group was important: removing one of the aromatic rings compromised the activity. Further functional assay showed that compound 19 could cause Nrf2 nuclear translocation and activate its downstream genes in cells.

Fig. 12. Docking mode of compound 19 with the Keap1 protein (PDB code: ; 4IQK).

Unfortunately, there have been some critics of compound 19 as it contains a fragment of pan-assay-interference-compounds (PAINS).63,64 To address such concerns, several biological experiments have been performed that support Nrf2 activation, including Nrf2 nuclear translocation and the up-regulation of Nrf2 downstream genes.61 Compound 19 also showed cellular protective effects against oxidative stress.65 These cellular results were consistent with Nrf2 activation, overall suggesting that compound 19 is a true Keap1–Nrf2 inhibitor. Indeed, a similar compound, compound 23, was discovered as a Nrf2 activator with a KD value of 1.7 μM by an independent group.66 Of note, the use of PAINS as a filter in drug discovery has been challenged recently,67,68 because 27 of the 437 compounds in the ; docking.org website (6.2%) and 67 from the 1775 drugs in the DrugBank (3.8%) are PAINS. Compounds with potential promiscuous actions must be carefully investigated to validate the mechanism of action rather than being excluded directly.67

2.3. Fragment-based drug design

Fragment-based drug design (FBDD) is potentially a more effective approach to identify PPI inhibitors.45,69 This approach has been successfully employed in inhibiting the Keap1–Nrf2 interactions.70,71

The 1,4-diphenyl-1,2,3-triazole compounds were identified as potential Keap1–Nrf2 PPI inhibitors using an in silico fragment-based approach.70 Compounds from 178 000 fragments of the ZINC database were docked into the Keap1 Kelch domain. The top 364 fragments were selected as a training set for further analysis. Common features were identified: carboxylate or nitro substituents formed favourable electrostatic and hydrogen bond interactions with Arg380, 415, 483 and Asn382 of Keap1. In some cases, the scaffold formed additional hydrogen-bonding interactions with the side chain of Ser602. Based on these, compound 24 (Fig. 13) was designed to mimic the pharmacophores and showed an 82% inhibition of Keap1–Nrf2 interactions at 100 μM but no apparent induction of NQO1 in Hepa1c1c7 mouse hepatoma cells, suggesting the need to improve the physicochemical properties of the two carboxyl groups. Further SAR study identified compounds 25 and 26 with improved Keap1–Nrf2 inhibitory activities. Both compounds demonstrated promising NQO1 induction in cells (doubling concentration of 0.6 μM and 1.3 μM, respectively).

Fig. 13. Structures of compounds 24–26.

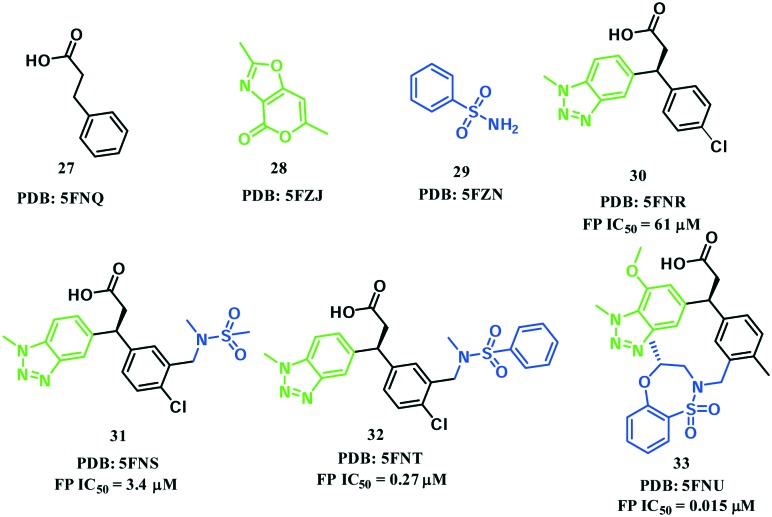

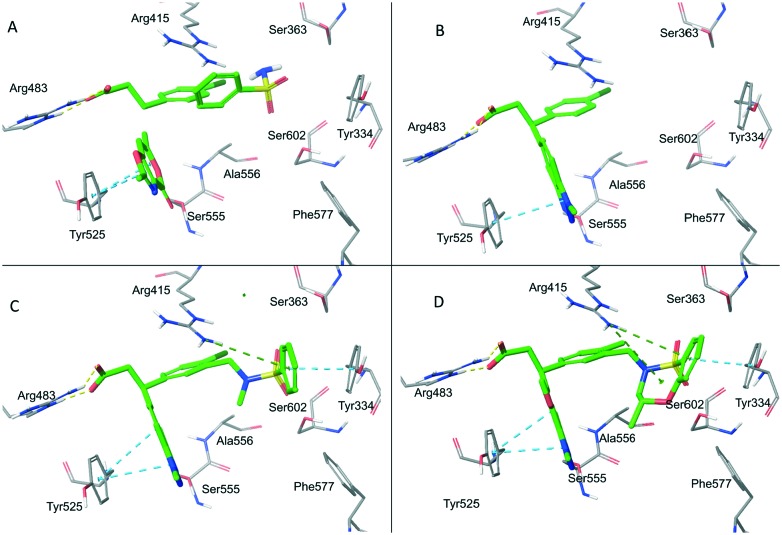

In 2016, Astex Pharmaceuticals and GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals disclosed a novel phenylpropanoic acid-based Keap1–Nrf2 PPI inhibitor through the FBDD method.71 A crystallographic screen of approximately 330 fragments led to the identification of three fragments 27, 28 and 29, which were located in the vicinity of Arg483, Tyr525 and Ser602, respectively (Fig. 14 and 15A). Among them, fragment 27 was identified as the “anchor fragment” for hit elaboration despite the FP IC50 of more than 1 mM. A benzotriazole moiety was attached directly to 27 in the fragment growing step to mimic the π–π stacking interaction of fragment 28 with Tyr525 (Fig. 15B). The target fragment 30 showed a significantly improved binding activity (FP IC50 = 61 μM, ITC KD = 59 μM). In order to recapitulate the hydrogen bonding interaction of fragment 29 with Ser602, a sulfonamide was introduced into the 3-position of the chlorophenyl ring, resulting in compound 31 with a 20-fold increase in potency. A benzene ring was then introduced on the sulfonamide (compound 32) that formed a π–π stacking interaction with Tyr334 (Fig. 15C), which further enhanced the potency by more than 10-fold. Finally, in order to fix the molecule in its bound conformation, a fused 7-membered benzoxathiazepine was formed by the cyclization of the phenyl sulphonamide. This cyclization could also fill the space between the sulphonamide and benzotriazole moieties that might be important to the binding activity. As a result, compound 33 had an IC50 value of 15 nM and retained the binding mode (Fig. 15D). This compound showed a high potency in cell-based assays, and activated the Nrf2 pathway in vivo using chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) models. Compound 33 is the most potent Keap1–Nrf2 PPI-based inhibitor reported to date.

Fig. 14. Structures of compounds 27–33.

Fig. 15. Co-crystal structures of fragments 27–29 (A), compound 30 (B), compound 32 (C) and compound 33 (D) with the Keap1 protein.

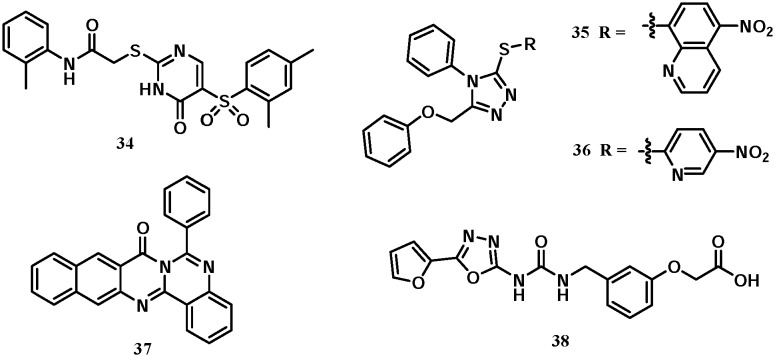

2.4. Other leads

Several additional classes of Keap1–Nrf2 inhibitors have been discovered (Fig. 16). Marcotte et al. identified compound 34 as a lead via a high-throughput screening. Its binding activity with the Keap1 protein is not very strong with an EC50 value of 118 μM. This compound is bound to Keap1 in a very interesting mode, wherein two molecules of compound 34 inserted into the Keap1 central cavity side by side and formed multiple hydrogen bonds and π–π stacking interactions with several key residues (PDB code: ; 4IN4).51 In 2014, Kazantsev et al. reported the 1-phenyl-1,3,4-triazole scaffold to inhibit Keap1–Nrf2 interactions.72 Compounds 35 and 36, namely MIND4 and MIND17, showed moderate inhibitory activities with KD values of 22.8 and 16.5 μM, respectively, and could induce the expression of Nrf2 downstream target genes in vitro. Compound 36 showed neuroprotective potential in an in vivo Huntington's disease model. 2-Phenylquinazoline-4-amine (compound 37) was recently reported as an Nrf2 activator that doubled NQO1 activity at 70 nM.73 Compound 38, reported by Satoh et al., is directly bound to the Kelch domain of Keap1 but the binding affinity was not reported (PDB codes: ; 3VNG, ; 3VNH).74

Fig. 16. Structures of compounds 34–38.

3. Conclusions and perspectives

With the progress in structural biology, the understanding of the binding interactions between Keap1 and Nrf2 opens the opportunity for developing small molecules to inhibit the Keap1–Nrf2 protein–protein interactions. Several groups have disclosed unique chemicals with decent inhibitory potencies as promising leads. Although the electrophilic Nrf2 activators may lack selectivity and cause off-target side effects, it might also give rise to multiple-target properties with broader biological activities that are difficult to achieve by direct Keap1–Nrf2 inhibition. Thus, further evaluation is needed to determine the advantages and limitations of selective Keap1–Nrf2 PPI and covalent electrophilic activators.

As the Keap1–Nrf2–ARE pathway plays a critical role in protecting cells from oxidative stress, which contributes to numerous human diseases, potent Keap1–Nrf2 PPI inhibitors discovered to date may be useful in many clinical indications. The in vivo efficacy needs more rigorous validations. Till now, only a few disease models have been evaluated in some studies, including the LPS-challenged inflammatory model,52 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) models,71 and a Huntington's disease model.72 Other disease models, such as cancers, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson disease, chronic kidney disease18 and cancer chemoprevention,75 may be considered in future studies.

The encouraging results in the Keap1–Nrf2 field have attracted growing research interest. It is important to enhance the hit rate using modern drug discovery strategies. At the same time, it is also critical to explore new chemical sources for more chemotypes of lead compounds, such as natural products, natural product-inspired libraries, and libraries via diversity-oriented organic synthesis. In summary, research in Keap1–Nrf2 PPI inhibition is evolving rapidly and Keap1–Nrf2 PPI is becoming a research hotspot.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Michaela Mühlberg from MedChemComm, RSC for the kind invitation on this review. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81502978 to C. Z. and 81673352 to Z. M.), the Youth Grant of Second Military Medical University (2014QN08 to C. Z.) and the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute of U.S.A. (R01CA193278 to C. X.).

Biographies

Chunlin Zhuang

Chunlin Zhuang, Ph.D., is currently a lecturer at the School of Pharmacy, Second Military Medical University, China. He received his Ph.D. degree in medicinal chemistry from the research group of Professor Wannian Zhang in 2014. In 2012, he was sponsored by the China Scholarship Council's Ph.D. Abroad Training Plan to work under the supervision of Professor Chengguo Xing at the University of Minnesota. His research interest is mainly focused on target identification of natural products and structure-based drug design of protein–protein interaction inhibitors.

Zhongli Wu

Zhongli Wu is a research associate at the School of Pharmacy, Second Military Medical University. He received his Bachelor's degree in Biotechnology at Henan Institute of Science and Technology, China (2012) and his Master's degree in Biochemical Engineering at Zhejiang University of Technology, China (2015). He joined WuXi AppTec Shanghai as a research fellow in the medicinal chemistry department (2015–2016). His research interests focus on the synthesis of bioactive natural products and related fluorescent probes.

Chengguo Xing

Chengguo Xing, Ph.D., is currently a professor and the Frank A. Duckworth Eminent Scholar Chair in Drug Discovery and Development at the University of Florida. He received his Ph.D. degree in organic chemistry from Arizona State University (2001). He joined Harvard University as a postdoctoral associate in 2001–2003 and the University of Minnesota as a faculty in 2003–2016. His research interests focus on isolating, identifying, designing, and synthesizing biologically active small molecules, employing such candidates as probes to tackle fundamental health-related biological questions and diseases, and evaluating their clinical potential in clinically relevant animal models.

Zhenyuan Miao

Zhenyuan Miao, Ph.D., is currently an associate professor at the School of Pharmacy, Second Military Medical University, China. He received his Ph.D. degree in medicinal chemistry from the research group of Professor Wannian Zhang in 2006. In 2015, he joined the research group of Professor Gunda I. Georg as a visiting scholar. His research interest is mainly focused on medicinal chemistry aspects of natural products, small molecule inhibitors of protein–protein interactions and fluorine-containing drug discovery.

Footnotes

†The authors declare no competing interests.

‡The protein figures were generated using PyMol (http://www.pymol.org/). The chemical structures are generated by ChemDraw 15.1.

References

- Finkel T., Holbrook N. J. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekiner-Gulbas B., Westwell A. D., Suzen S. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013;20:4451–4459. doi: 10.2174/09298673113203690142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakkiyalakshmi E., Sireesh D., Rajaguru P., Paulmurugan R., Ramkumar K. M. Pharmacol. Res. 2015;91:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. A., Johnson J. A. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2015;88:253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.07.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg M., Patil J., D'Angelo B., Weber S. G., Mallard C. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howden R. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity. 2013;2013:104308. doi: 10.1155/2013/104308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van-Assche T., Huygelen V., Crabtree M. J., Antoniades C. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011;17:4210–4223. doi: 10.2174/138161211798764799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenitzer J. R., Freeman B. A. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1203:45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman H. J. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2016;97:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan M., Rajasekaran N. S. Front. Physiol. 2016;7:241. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens D. S., Nawrot T. S. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2016;3:258–269. doi: 10.1007/s40572-016-0098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova-Kostova A. T., Talalay P. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008;52(Suppl 1):S128–S138. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyakhovich V. V., Vavilin V. A., Zenkov N. K., Menshchikova E. B. Biochemistry. 2006;71:962–974. doi: 10.1134/s0006297906090033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favreau L. V., Pickett C. B. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:4556–4561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K., Wakabayashi N., Katoh Y., Ishii T., Igarashi K., Engel J. D., Yamamoto M. Genes Dev. 1999;13:76–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak M. K., Kensler T. W. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010;244:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M. C., Ji J. A., Jiang Z. Y., You Q. D. Med. Res. Rev. 2016;36:924–963. doi: 10.1002/med.21396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magesh S., Chen Y., Hu L. Med. Res. Rev. 2012;32:687–726. doi: 10.1002/med.21257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang C., Miao Z., Sheng C., Zhang W. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014;21:1861–1870. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666140217104648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namani A., Li Y., Wang X. J., Tang X. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1843:1875–1885. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K., Chiba T., Takahashi S., Ishii T., Igarashi K., Katoh Y., Oyake T., Hayashi N., Satoh K., Hatayama I., Yamamoto M., Nabeshima Y. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;236:313–322. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon M., Thomas N., Itoh K., Yamamoto M., Hayes J. D. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:31556–31567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403061200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nioi P., Nguyen T., Sherratt P. J., Pickett C. B. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:10895–10906. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.10895-10906.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh Y., Itoh K., Yoshida E., Miyagishi M., Fukamizu A., Yamamoto M. Genes Cells. 2001;6:857–868. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhry S., Zhang Y., McMahon M., Sutherland C., Cuadrado A., Hayes J. D. Oncogene. 2013;32:3765–3781. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Liu K., Geng M., Gao P., Wu X., Hai Y., Li Y., Li Y., Luo L., Hayes J. D., Wang X. J., Tang X. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3097–3108. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi N., Itoh K., Wakabayashi J., Motohashi H., Noda S., Takahashi S., Imakado S., Kotsuji T., Otsuka F., Roop D. R., Harada T., Engel J. D., Yamamoto M. Nat. Genet. 2003;35:238–245. doi: 10.1038/ng1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Kong A. N. Mol. Carcinog. 2009;48:91–104. doi: 10.1002/mc.20465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Suzuki T., Kobayashi A., Wakabayashi J., Maher J., Motohashi H., Yamamoto M. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28:2758–2770. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01704-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo S. C., Li X., Henzl M. T., Beamer L. J., Hannink M. EMBO J. 2006;25:3605–3617. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K., Mimura J., Yamamoto M. Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2010;13:1665–1678. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. D., Lo S. C., Cross J. V., Templeton D. J., Hannink M. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:10941–10953. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.24.10941-10953.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova-Kostova A. T., Holtzclaw W. D., Cole R. N., Itoh K., Wakabayashi N., Katoh Y., Yamamoto M., Talalay P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:11908–11913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172398899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell M. A., Hayes J. D. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015;43:687–689. doi: 10.1042/BST20150069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter S., Gupta S. C., Chaturvedi M. M., Aggarwal B. B. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2010;49:1603–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A. J., Kerns J. K., Callahan J. F., Moody C. J. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:7463–7476. doi: 10.1021/jm400224q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Yamamoto M. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2015;88:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abed D. A., Goldstein M., Albanyan H., Jin H., Hu L. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2015;5:285–299. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock R., Bertrand H. C., Tsujita T., Naz S., El-Bakry A., Laoruchupong J., Hayes J. D., Wells G. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2012;52:444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoyama D., Chen Y., Huang X., Beamer L. J., Kong A. N., Hu L. J. Biomol. Screening. 2012;17:435–447. doi: 10.1177/1087057111430124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock R., Schaap M., Pfister H., Wells G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013;11:3553–3557. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40249e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M. C., Yuan Z. W., Jiang Y. L., Chen Z. Y., You Q. D., Jiang Z. Y. Mol. BioSyst. 2016;12:1378–1387. doi: 10.1039/c6mb00030d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong K. I., Padmanabhan B., Kobayashi A., Shang C., Hirotsu Y., Yokoyama S., Yamamoto M. Mol. Cell.Mol. Cell. Biol.Biol. 2007;27:7511–7521. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00753-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan B., Tong K. I., Ohta T., Nakamura Y., Scharlock M., Ohtsuji M., Kang M. I., Kobayashi A., Yokoyama S., Yamamoto M. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng C., Dong G., Miao Z., Zhang W., Wang W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:8238–8259. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00252d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner J., Fry D. C., Peng Z., Roberts J. Future Med. Chem. 2011;3:2021–2038. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villoutreix B. O., Kuenemann M. A., Poyet J. L., Bruzzoni-Giovanelli H., Labbe C., Lagorce D., Sperandio O., Miteva M. A. Mol. Inf. 2014;33:414–437. doi: 10.1002/minf.201400040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z. Y., Lu M. C., Xu L. L., Yang T. T., Xi M. Y., Xu X. L., Guo X. K., Zhang X. J., You Q. D., Sun H. P. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:2736–2745. doi: 10.1021/jm5000529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Magesh S., Chen L., Wang L., Lewis T. A., Chen Y., Khodier C., Inoyama D., Beamer L. J., Emge T. J., Shen J., Kerrigan J. E., Kong A. N., Dandapani S., Palmer M., Schreiber S. L., Munoz B. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:3039–3043. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jnoff E., Albrecht C., Barker J. J., Barker O., Beaumont E., Bromidge S., Brookfield F., Brooks M., Bubert C., Ceska T., Corden V., Dawson G., Duclos S., Fryatt T., Genicot C., Jigorel E., Kwong J., Maghames R., Mushi I., Pike R., Sands Z. A., Smith M. A., Stimson C. C., Courade J. P. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:699–705. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte D., Zeng W., Hus J. C., McKenzie A., Hession C., Jin P., Bergeron C., Lugovskoy A., Enyedy I., Cuervo H., Wang D., Atmanene C., Roecklin D., Vecchi M., Vivat V., Kraemer J., Winkler D., Hong V., Chao J., Lukashev M., Silvian L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:4011–4019. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z. Y., Xu L. L., Lu M. C., Chen Z. Y., Yuan Z. W., Xu X. L., Guo X. K., Zhang X. J., Sun H. P., You Q. D. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:6410–6421. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A. D., Potteti H., Richardson B. G., Kingsley L., Luciano J. P., Ryuzoji A. F., Lee H., Krunic A., Mesecar A. D., Reddy S. P., Moore T. W. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;103:252–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M. C., Tan S. J., Ji J. A., Chen Z. Y., Yuan Z. W., You Q. D., Jiang Z. Y. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;7:835–840. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T., Ichimura Y., Taguchi K., Suzuki T., Mizushima T., Takagi K., Hirose Y., Nagahashi M., Iso T., Fukutomi T., Ohishi M., Endo K., Uemura T., Nishito Y., Okuda S., Obata M., Kouno T., Imamura R., Tada Y., Obata R., Yasuda D., Takahashi K., Fujimura T., Pi J., Lee M. S., Ueno T., Ohe T., Mashino T., Wakai T., Kojima H., Okabe T., Nagano T., Motohashi H., Waguri S., Soga T., Yamamoto M., Tanaka K., Komatsu M. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12030. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkel A. F., Engel C. K., Margerie D., Kannt A., Szillat H., Glombik H., Kallus C., Ruf S., Gussregen S., Riedel J., Herling A. W., von Knethen A., Weigert A., Brune B., Schmoll D. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:28446–28455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.678136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M., Zhou H. S., You Q. D., Jiang Z. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:7305–7310. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoichet B. K. Nature. 2004;432:862–865. doi: 10.1038/nature03197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T., Li Q., Zhou Z., Wang Y., Bryant S. H. AAPS J. 2012;14:133–141. doi: 10.1208/s12248-012-9322-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripphausen P., Nisius B., Bajorath J. Drug Discovery Today. 2011;16:372–376. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang C., Narayanapillai S., Zhang W., Sham Y. Y., Xing C. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:1121–1126. doi: 10.1021/jm4017174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H. P., Jiang Z. Y., Zhang M. Y., Lu M. C., Yang T. T., Pan Y., Huang H. Z., Zhang X. J., You Q. D. MedChemComm. 2014;5:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlin J. L., Inglese J., Walters M. A. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2015;14:279–294. doi: 10.1038/nrd4578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baell J., Walters M. A. Nature. 2014;513:481–483. doi: 10.1038/513481a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang C., http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-90030-1015518668.htm, 2014.

- Hu L. Q., Magesh S., Chen L., Lewis T., Munoz B. and Wang L., USA Pat., WO2013067036A1, 2013.

- Senger M. R., Fraga C. A., Dantas R. F., Silva, Jr. F. P. Drug Discovery Today. 2016;21:868–872. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilchmann F., Marcaida M. J., Kotak S., Schick T., Boss S. D., Awale M., Gonczy P., Reymond J. L. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:7188–7211. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jubb H., Higueruelo A. P., Winter A., Blundell T. L. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012;33:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand H. C., Schaap M., Baird L., Georgakopoulos N. D., Fowkes A., Thiollier C., Kachi H., Dinkova-Kostova A. T., Wells G. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:7186–7194. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies T. G., Wixted W. E., Coyle J. E., Griffiths-Jones C., Hearn K., McMenamin R., Norton D., Rich S. J., Richardson C., Saxty G., Willems H. M., Woolford A. J., Cottom J. E., Kou J. P., Yonchuk J. G., Feldser H. G., Sanchez Y., Foley J. P., Bolognese B. J., Logan G., Podolin P. L., Yan H., Callahan J. F., Heightman T. D., Kerns J. K. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:3991–4006. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantsev A., Thompson L. M., Abagyan R. and Casale M. USA Pat., WO2014197818A2, 2014.

- Ghorab M. M., Alsaid M. S., El-Gazzar M. G., Higgins M., Dinkova-Kostova A. T., Shahat A. A. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2016;31:34–39. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2016.1163343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M., Aoki T., Inoue H., Tanaka T. and Kunishima N., Japan Pat., JP2013028575, 2013.

- Hayes J. D., McMahon M., Chowdhry S., Dinkova-Kostova A. T. Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2010;13:1713–1748. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]