Hybrids of allosteric modulators of the muscarinic receptor and the AChE inhibitor tacrine and the orthosteric muscarinic agonists iperoxo and isox were synthesized.

Hybrids of allosteric modulators of the muscarinic receptor and the AChE inhibitor tacrine and the orthosteric muscarinic agonists iperoxo and isox were synthesized.

Abstract

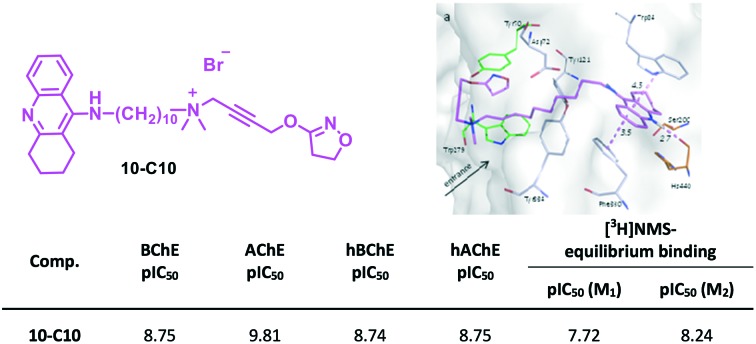

A set of hybrid compounds composed of the fragment of allosteric modulators of the muscarinic receptor, i.e. W84 and naphmethonium, and the well-known AChE inhibitor tacrine on the one hand, and the skeletons of the orthosteric muscarinic agonists, iperoxo and isox, on the other hand, were synthesized. The two molecular moieties were connected via a polymethylene linker of varying length. These bipharmacophoric compounds were investigated for inhibition of AChE (from electric eel) and BChE (from equine serum) as well as human ChEs in vitro and compared to previously synthesized dimeric inhibitors. Among the studied hybrids, compound 10-C10, characterized by a 10 carbon alkylene linker connecting tacrine and iperoxo, proved to be the most potent inhibitor with the highest pIC50 values of 9.81 (AChE from electric eel) and 8.75 (BChE from equine serum). Docking experiments with compounds 10-C10, 7b-C10, and 7a-C10 helped to interpret the experimental inhibitory power against AChE, which is affected by the nature of the allosteric molecular moiety, with the tacrine-containing hybrid being much more active than the naphthalimido- and phthalimido-containing analogs. Furthermore, the most active AChE inhibitors were found to have affinity to M1 and M2 muscarinic receptors. Since 10-C10 showed almost no cytotoxicity, it emerged as a promising lead structure for the development of an anti-Alzheimer drug.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is one of the most prominent neurodegenerative diseases affecting worldwide about 9% of the population aged over 65 and 26% of the people older than 85.1 Due to the rising number of patients,2 in the future there is an urgent need for the development of new, highly effective drugs against AD. Besides other strategies, today's pharmacotherapy of AD is essentially based on the cholinergic hypothesis since the concentration of ACh is decreased in the brain leading to the loss of cognitive functions. The main therapeutic approach is to inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE), an enzyme responsible for the rapid hydrolysis of ACh,3 and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), an enzyme with structural features very similar to those of AChE.4–6 Indeed, high levels of BChE were found to influence Aβ aggregation during the early stages of senile plaque formation.7 Therefore, concurrent inhibition of both BChE and AChE may have clinical benefits in the treatment of AD symptoms.7 Tacrine (Fig. 1), donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine are well-known ChE inhibitors for AD therapy.8 Nevertheless, the clinical effectiveness of AChEIs in AD therapy is still under debate9 and the use of tacrine is currently limited due to its severe hepatotoxicity.10 As a consequence, tacrine has recently been used for the development of hybrid molecules11–15 in order to combine its potent AChE inhibition with other favorable pharmacological benefits, such as reduced hepatotoxicity. In particular, the bis(7)tacrine dimer 9-C7 (Fig. 2) was found to address both sites of the enzyme, the catalytic active site (CAS) and the peripheral anionic site (PAS), resulting in 1000-fold higher AChE inhibitory potency than tacrine.16

Fig. 1. Structures of tacrine 1, iperoxo 2, isox 3, W84 4 and naphmethonium 5.

Fig. 2. Structures of the different hybrid sets and tacrine dimers investigated in this study.

In addition, agonists of the muscarinic receptor, especially of the M1 subtype, have gained great interest in the development of anti-Alzheimer drugs because muscarinic M1 agonists can directly stimulate neurotransmission. Recently, so-called dualsteric ligands, combining the moieties of allosteric modulators such as W84 4 and naphmethonium 5 (Fig. 1) and the superagonist iperoxo172 (Fig. 1) were tested for their anticholinesterase activity and found to be moderate inhibitors of rat brain cholinesterase.18 In order to find compounds with improved anticholinesterase activity for both AChE and BChE combined with affinity to the M1 and M2 receptor and to derive structure–activity relationships, this small set of compounds was further expanded by the synthesis of new hybrids. The use of polymethylene linker chains of different lengths and the linkage of the phthalyl moiety to the agonist isox 319–21 (Fig. 2) as well as combining tacrine and iperoxo within one molecule led to new hybrid molecules (Fig. 2). The entire set of compounds was tested for their anticholinesterase activity and affinity to the M2 and in part the M1 muscarinic receptor in order to find out whether hybrid compounds can serve as a strategy for the development of anti-Alzheimer drugs.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

The synthesis of the iperoxo related bisquaternary ligands 7a-C7/C8,18,22 7b-C7/C8,18,22 6a/b-C6,18 and isoxazole derivative 8a-C619 and the synthesis of the homodimeric tacrine hybrids 9-C7/C1023 were accomplished according to previously described procedures (Scheme 1). In brief, phthalimidopropylamine 11a19 and 1,8-naphthalimidopropylamine 11b19 were reacted with a large excess of commercially available dibromoalkanes in refluxing acetonitrile (Scheme 1). The monoquaternary intermediates were obtained in 57–98% yield. Subsequent reaction with a slight excess of iperoxo-base 217,20 and 4-(isoxazol-3-yloxy)-N,N-dimethylbut-2-yn-1-amine 3,19 respectively, in refluxing acetonitrile afforded the desired compounds 7a-C9, 7a-C10, 7b-C9, and 7b-C10 in 88–95% and 8a-C4, and 8a-C8 in 53% and 63% yield, respectively.

Scheme 1. a: CH3CN, reflux.

For the preparation of the two tacrine-containing hybrid molecules, tacrine 124 was treated with a large excess of commercially available 1,7-dibromoheptane and 1,10-dibromodecane to obtain the known intermediates 13-C725 and 13-C10.24 Subsequent addition of two equivalents of iperoxo-base 217,20 in acetonitrile in a microwave assisted reaction yielded the target compounds 10-C7 and 10-C10 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. a: KOH, CH3CN, rt. b: KI/K2CO3, CH3CN, 80 °C (microwave).

2.2. Pharmacology

The compounds were evaluated towards BChE (E.C. 3.1.1.8) from equine serum, hBChE (E.C. 3.1.1.8) from human serum, AChE (E.C. 3.1.1.7) from electric eel, and hAChE (E.C. 3.1.1.7), a recombinant expressed in HEK 293 cells (see Table 1). The compounds containing a naphthyl moiety (7b-C7 and 7b-C8) were reported in the literature to exhibit higher anticholinesterase activity toward the cholinesterase from rat brain homogenates than the hybrids comprising a phthalyl moiety (7a-C7 and 7a-C8) (Table 1).18 These findings could also be confirmed using the other AChEs and BChEs. With regard to the linker length, a longer linker resulted in higher anticholinesterase activity, with 7a-C10 and 7b-C10 having the highest inhibitory potency (pIC50 (BChE) = 5.37 and 6.99 and pIC50 (AChE) = 5.26 and 6.50, respectively). In contrast, compounds linked to isox 3 (8a-C4, 8a-C6, and 8a-C8) as well as the hybrids containing a more rigid allosteric fragment (6a-C6 and 6b-C6) showed moderate cholinesterase inhibition.

Table 1. In vitro cholinesterase activity, cytotoxicity and log P values of the investigated compounds.

| Compound | BChE a pIC50 b [M] | AChE c pIC50 b [M] | hBChE d pIC50 b [M] | hAChE e pIC50 b [M] | Cytotoxicity | log P f |

| HEPG2 IC50 [μM] | ||||||

| 1 | 8.57 | 7.60 | n.d. | n.d. | 111 (±2.28) | n.d. |

| 6a-C6 | 4.97 | 5.62 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.84 |

| 6b-C6 | 6.07 | 5.98 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.54 |

| 7a-C7 | 5.19 | 4.83 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.79 |

| 7a-C8 | 5.13 | 4.89 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.78 |

| 7a-C9 | 4.88 | 4.80 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.79 |

| 7a-C10 | 5.37 | 5.26 | 5.71 | 4.88 | n.d. | 0.80 |

| 7b-C7 | 6.69 | 6.04 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.70 |

| 7b-C8 | 6.46 | 6.10 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.61 |

| 7b-C9 | 6.49 | 6.44 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.69 |

| 7b-C10 | 6.99 | 6.50 | 6.58 | 5.97 | n.d. | 1.77 |

| 8a-C4 | 4.07 | 19.12% inhib. at 100 μM | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.55 |

| 8a-C6 | 4.41 | 32.91% inhib. at 100 μM | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.99 |

| 8a-C8 | 5.10 | 4.17 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.83 |

| 9-C7 | 9.14 | 10.48 | n.d. | n.d. | <1.38 (±0.08) | n.d. |

| 9-C10 | 9.34 | 9.00 | n.d. | n.d. | <1.25 (±0.00) | n.d. |

| 10-C7 | 8.29 | 8.76 | 8.34 | 8.70 | >160 (±0.00) | 2.05 |

| 10-C10 | 8.75 | 9.81 | 8.74 | 8.75 | 32.2 (±0.41) | 3.28 |

| 13-C7 | 6.58 | 9.40 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 13-C10 | 8.06 | 9.25 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

aBChE from equine serum (E.C. 3.1.1.8).

bpIC50 (SE) values are the negative logarithm of the concentration causing half-maximal inhibition of cholinesterase activity.

cAChE from electric eel (E.C. 3.1.1.7).

dhBChE from human serum (E.C. 3.1.1.8).

ehAChE, a recombinant expressed in HEK 293 cells.

fFor log P calculation, see Tables S2 and S3 (ESI).

Tacrine is known as a potent anticholinesterase inhibitor.26 Replacing the naphthyl moiety of hybrid 7b-C10 with tacrine 10-C10 resulted in excellent inhibitory activity for both AChE (pIC50 = 9.81) and BChE (pIC50 = 8.75), with an increased potency compared to that of monomeric tacrine 1 (Table 1). A similar inhibitory activity was found against hChEs, where it exhibited about 1.5–2 log unit higher potency than 7b-C10 and tacrine 1. Moreover, the hybrid 10-C10 is as active as the previously reported dimers 9-C7 and 9-C10 (Fig. 2).16,23,27,28 A shorter linker length (10-C7) decreased the inhibitory activity slightly (Table 1).

Since the hybrids 7a-C6 and 7b-C6 were found to have comparable binding affinity measures regarding the M1 and M2 receptor29 and because tacrine, an allosteric modulator, is known for its M2 receptor subtype selectivity (over M1 and M3)30 the compounds 7a/b-C10 and 10-C7/C10 were tested for their affinity to the M2 receptor, representatively (see Table S1‡). Thus, the M2 receptor was chosen foremost instead of M1 to offer the tacrine moiety the highest propensity to bind allosterically to the M receptor. Firstly, the allosterically retarding action of selected compounds on the kinetics of [3H]NMS dissociation from M2 receptors was checked and quantified in order to calculate the incubation time needed to reach binding equilibrium in the presence of a given test compound (cf. Table S1,‡ and detailed experimental procedures). Thereafter, in equilibrium binding experiments all compounds were found to show almost the same high affinity log IC50 values in orthosterically unliganded M2 receptors in the nanomolar range of concentration, suggesting that the iperoxo part of the hybrids is occupying the orthosteric binding site of M2 (cf. high affinity of iperoxo31). Thus, the tacrine moiety of 10-C7/C10, even in M2 receptors, was not able to hinder the iperoxo moiety from governing the high affinity binding of the hybrids to the orthosteric site. The inhibition of orthosteric ligand dissociation by the hybrids (Fig. S1A‡) revealed their affinities (log KX,diss) at the allosteric site of M2 receptors to be lower than at orthosterically unliganded receptors throughout (Table S1‡) which is in line with downward directed inhibition curves at the orthosterically unliganded receptor and binding equilibrium (see above and Fig. S1B‡). The compounds 7b-C10 and 10-C10 had equal log KX,diss values in NMS-occupied M2 receptors, suggesting that the tacrine moiety was equal to the naphmethonium moiety regarding their contribution to allosteric binding of these otherwise identical hybrids (Table S1‡). Finally, the selected tacrine hybrids 10-C7 and 10-C10 were studied in NMS liganded and unliganded M1 receptors and yielded qualitatively a very similar picture, with the exception that the dissociation of [3H]NMS from M1 receptors was maximally retarded 5-fold by 10-C10 (equivalent to a reduction of k–1 to 20 percent, cf. Fig. S2A‡). This value of 10-C10, nevertheless, was reached in a concentration dependent fashion and thus documented the possibility of a purely allosteric binding pose also of this hybrid at M1 receptors (cf. Fig. S2A‡). That being said, quantitatively, the individual affinity measures of 10-C7 and 10-C10 dropped between 3- and 8-fold (Fig. S2 and Table S2‡) compared to that of M2 receptors (Fig. S1 and Table S1‡). The extent of decreased binding affinity of these hybrids at the orthosterically unliganded M1 receptor could be explained by the 10-fold loss of iperoxo affinity compared to M2 receptors reported recently,32 whereas the twofold affinity loss reported for tacrine alone in the literature is too small to explain it.30 The ratios of affinity measures calculated based on receptor occupancy with or without NMS differed at M2 receptors for 10-C7 (104-fold) compared to 10-C10 (20-fold) (cf. Table S1‡), whereas the corresponding ratios calculated at M1 receptors for 10-C7 (79-fold) and 10-C10 (55-fold) were similar (cf. Table S2‡). Taken together, 10-C7 and 10-C10 showed slightly attenuated affinity measures in M1 compared to M2 receptors but qualitatively similar receptor affinity binding profiles.

Future studies will explore how these high affinity muscarinic hybrids interact with M1 receptors in the context of AD.

2.3. Cytotoxicity

The use of tacrine in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease is currently limited due to its severe hepatotoxicity.10,13 Interestingly, the combination of tacrine with iperoxo through a heptyl or decyl linker chain (10-C7 and 10-C10) resulted in a lower cytotoxicity towards HEPG2 cells than the dimers 9-C7 and 9-C10 (Table 1). In particular, the cytotoxicity of the most potent hybrid 10-C7 is very low, which makes it an interesting lead compound.

2.4. Physicochemical properties

The log P value (octanol–water partition coefficient) is a measure of lipophilicity and enables to some degree prediction of permeability across biological membranes in vitro and in vivo.33 Therefore, the lipophilicity of the novel hybrid compounds was determined by using a RP (reversed phase) HPLC method reported earlier.34 Log P values ranged from 0.78 to 3.28 (Tables 1, S2 and S3‡) and hint at good oral bioavailability.35 Hybrids containing a phthalyl moiety are more hydrophilic (log P = 0.78–1.55) than their naphthyl analogs (log P = 1.54–3.28). Not surprisingly, the longer the chain length, the greater the lipophilicity. The two tacrine-linked hybrids 10-C7 (log P 2.05) and 10-C10 (log P 3.28) share a similar overall lipophilic molecular skeleton like their phthalyl and naphthyl analogs, even though they possess only one permanently charged nitrogen.

2.5. Computational studies

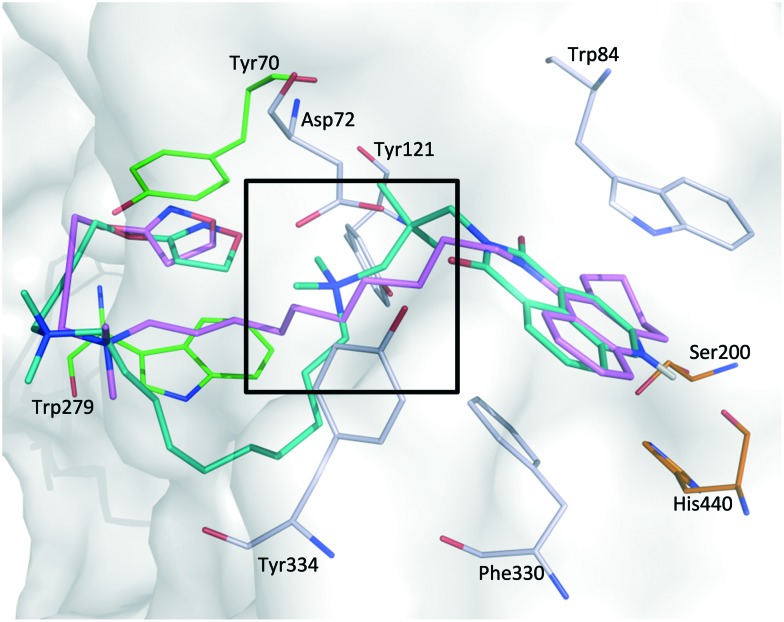

Tacrine and bis-tacrine derivatives are some of the most active inhibitors of AChE, displaying one-digit nanomolar IC50 values.23,36–38 The crystal structures of these ligands in complex with AChE show conserved binding modes of the tacrine pharmacophore in the catalytic active site (CAS).39–41 This conserved binding mode was also assumed for the tacrine scaffold of 10-C10 as well as for the naphthyl moiety of 7b-C10 and the phthalyl moiety of 7a-C10, the most promising hybrid derivatives endowed with anticholinesterase activity. Docking studies for these large compounds were performed using a scaffold match constraint to reduce the search space and obtain more consistent poses. The selected representative poses of the three ligands show a similar orientation of the CAS-binding motif and of the iperoxo motif, which is placed in the peripheral anionic site (PAS) (Fig. 3). For 10-C10, a hydrogen-bond distance of 2.7 Å between the tacrine unit and the His440 backbone is observed; further stabilization might occur through π–π interactions with Trp84 and Phe330 (at 4.5 and 3.5 Å, respectively; Fig. 3a). While the decamethylene linker spans the AChE binding gorge, the quaternary ammonium group is placed at the entrance of the binding site where it is rather solvent exposed. The iperoxo motif refolds back and is localized in the PAS region. Similar interaction possibilities were found for 7b-C10 and 7a-C10 (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. (a) Docking solution of 10-C10 (pink), with the interaction distances shown in the CAS (orange) and the iperoxo motif in the PAS (green). (b) Docking solution of 7b-C10 (blue) and 7a-C10 (yellow) with their interaction distances. Distances were measured between the geometric centers of the interacting units and are given in italic numbers, with the unit Å omitted for clarity. The figure was generated with PyMol (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.8.0.5, Schrödinger, LLC).

Besides rather unspecific hydrophobic interactions, a hydrogen bond interaction between one of the carbonyl oxygens and Tyr334 is observed for 7b-C10 and 7a-C10 (2.6 Å distance in both cases). The extended decamethylene linker protrudes from the enzyme surface. The additional permanently charged nitrogen atom, which represents the major difference between 7b-C10 and 7a-C10 on the one hand and 10-C10 on the other hand, is placed between Tyr121 and Asp72 in the middle of the AChE gorge (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Overlap of the docking solutions of 10-C10 (pink) and 7b-C10 (blue), highlighting the main difference in the linker region (box). The figure was generated with PyMol (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.8.0.5, Schrödinger, LLC).

Given the similar binding modes, the question arises as to why 7b-C10 shows a remarkably lower affinity than 10-C10. An obvious hypothesis is that the additional quaternary ammonium group causes this difference, presumably because of a much higher desolvation penalty in comparison to that of the uncharged alkylene chain. A 3D-RISM analysis carried out with MOE42 supports this assumption: relevant unfavorable contributions (depicted in red in Fig. 5) to the solvation free energy of binding appear around the ammonium group of 7b-C10, but not in the corresponding area of 10-C10 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Depiction of 3D-RISM computed ΔGbinding solvation contributions for (a) 7b-C10 and (b) 10-C10 (red = unfavorable and green = favorable contribution), contoured at an iso-level of 1 kcal mol–1 Å–3. The figure was generated with MOE 2016.05.

As the docking poses of 7a-C10 and 7b-C10 are virtually identical in the linker region, the same unfavorable contributions of the quaternary nitrogen can be assumed for 7a-C10.

In addition to this qualitative representation of (de-)solvation contributions to the binding free energy, solvation free energies were calculated with the quantum chemical SMD method for tetramethylammonium and n-propane as the two fragment molecules representing the different linkers in 7b-C10 (ammonium) and 10-C10 (alkylene chain).43 Using n-octanol as the dielectric medium mimicking the protein environment, a desolvation free energy of –3.26 kcal mol–1 was obtained for propane (as expected, propane favors an apolar environment), whereas a value of +0.92 kcal mol–1 was calculated for tetramethylammonium. Accordingly, a free energy difference of 4.18 kcal mol–1 (in favor of propane, viz.10-C10) may arise due to the different solvation properties. This estimate would be perfectly in line with the affinity difference between 10-C10 and 7b-C10, which should be around 4.5 kcal mol–1 based on the difference in IC50.

Computational studies showed that all three ligands are likely to display a similar orientation in the AChE binding site. However, the extra charge incorporated by the quaternary nitrogen in the linker of 7b-C10 and 7a-C10 appears to be rather unfavorable and is most probably the main reason for the relatively low IC50 values of 7b-C10 and 7a-C10 in comparison to that of 10-C10.

3. Conclusion

In summary, a set of hybrid compounds was investigated which incorporates one moiety (phthalyl, naphthyl, tacrine) that binds to the catalytic active site and another moiety (iperoxo 2, isox 3) that addresses the peripheral anionic site of cholinesterases. The two pharmacophoric groups were connected by a polymethylene chain of varying length. The compounds were evaluated for their anticholinesterase activity and the results obtained from the structure–activity relationship studies indicated that both the nature of the two moieties and the length of the alkylene chain are crucial for their potency. Naphthyl-related hybrids (b series) were found to be more active than the corresponding W84-related analogs (a series). Additionally, the longer the alkylene chain length, the higher the observed pIC50 values. Compounds bearing longer linker length fit better into the binding gorge of the enzyme and therefore result in higher activity. Computational studies supported these experimental findings. The ten-methylene chain exactly covers the distance between PAS and CAS of the cholinesterase, engendering a simultaneous block of the enzyme activity. Notably, the additional quaternary ammonium group in the naphmethonium- and W84-related dual derivatives resulted in an unfavorable higher desolvation penalty in comparison to the uncharged alkylene chain present in the tacrine-related hybrids. The tacrine containing hybrids 9, 10, and 13 exhibit the highest inhibitory activity towards both BChE and AChE with subnanomolar IC50 values for 9-C7 and 9-C10 as well as 10-C10, besides the alkylated tacrine derivatives 13. In addition, the most potent ChE inhibitors show high affinity to muscarinic M1 and M2 receptors and thus have possibly a dual mechanism of action. Of note, the most potent compound showed a low cytotoxicity which makes 10-C7 and 10-C10 very promising lead structures for the development of anti-Alzheimer drugs. Structural variations of the hybrid compounds, especially with regard to optimization of the linker, without quaternary ammonium groups in order to obtain tertiary amines, are however necessary in the light of drug development studies and are in progress.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Chemistry

Melting points were determined on a B540 Büchi apparatus (Flawil, Switzerland) as well as on a Stuart melting point apparatus SMP3 (Bibby Scientific, UK) and are uncorrected. 1H (400.132 MHz) and 13C (100.613 MHz) NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AV 400 instrument (Bruker Biospin, Ettlingen, Germany) or on a Varian Mercury 300 (1H, 300.063; 13C, 75.451 MHz) spectrometer (Darmstadt, Germany). As an internal standard, the signals of the deuterated solvents were used (DMSO-d6: 1H 2.5 ppm, 13C 39.52 ppm; CDCl3: 1H 7.26 ppm, 13C 77.16 ppm). Abbreviations for data quoted are s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; q, quartet; m, multiplet; b, broad; dd, doublet of doublets; dt, doublet of triplets; tt, triplet of triplets; and tq, triplet of quartets. Coupling constants (J) are given in Hz. TLC analyses were performed on commercial silica gel 60 F254 aluminum sheets and on pre-coated TLC-plates Alox-25/UV254 (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany); spots were further evidenced by spraying with a dilute alkaline potassium permanganate solution and with Dragendorff reagent44,45 for tertiary amines. For column chromatography, silica gel 60, 230–400 mesh (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and aluminium oxide 90 basic (Macherey Nagel, Düren, Germany) were used. Column chromatography was also performed on an Interchim Puri Flash 430 (Ultra Performance Flash Purification) instrument (Montluçon, France) connected to an Interchim Flash ELSD. The columns used are silica 25 g, 30 μm; Alox-B 40 g, 32/63 μm; and Alox-B 25 g, 32/63 μm (Interchim, Montluçon, France). ESI mass spectra of the compounds were obtained on an Agilent LC/MSD Trap G2445D instrument (Waldbronn, Germany) and on a Varian 320 LC-MS/MS instrument (Darmstadt, Germany). Data are reported as mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of the corresponding positively charged molecular ions. Microwave supported reactions were carried out on an MLS-rotaPREP instrument (Milestone, Leutkirch, Germany). Chemicals were of analytical grade and purchased from Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany), Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Homburg, Germany) and Sigma Chemicals (München, Germany). The purity of final compounds 7a-C9, 7a-C10, 8a-C4, 8a-C8, 7b-C9, and 7b-C10 was determined using an Agilent Technologies 1220 Infinity LC HPLC instrument (Waldbronn, Germany). The HPLC analyses were performed on a LiChrosher® 100 RP-8 analytical column (250 × 4.6 mm; 5.0 μm; Bischoff). The injection volume of the sample was 10 μL. The mobile phase consisted of (A) 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 3) and (B) acetonitrile (A/B 30 : 70) and was isocratically delivered at a flow rate of 1 ml min–1. All final compounds tested for biological activity showed ≥95% purity (detection by UV absorption at 210 nm). The purities of target compounds 10-C7 and 10-C10 were determined using capillary electrophoresis and were found to be ≥95%. The CE measurements were performed by means of a Beckman Coulter P/ACE System MDQ (Fullerton, CA, USA), equipped with a diode array detector measuring at wavelengths of 210 nm and 254 nm. A fused silica capillary (effective length 50.0 cm, total length 60.2 cm, inner diameter 50 μm) was used for the separation. A new capillary was conditioned by rinsing for 30 min with 0.1 mol L–1 NaOH, 2 min with H2O, 10 min with 0.1 mol L–1 HCl and 2 min with H2O. Before each run the capillary was rinsed for 2 min with H2O and 5 min with the running buffer. All rinsing steps were performed with a pressure of 30.0 psi. The samples were injected with a pressure of 0.5 psi for 5.0 s at the anodic side of the capillary. The capillary was kept at 25 °C and a voltage of +25 kV was applied. A 50 mM aqueous sodium borate solution, pH 10.5, was prepared as running buffer, using ultrapure Milli-Q water (Millipore, Milford, MA, USA). The aqueous solutions were filtered through a 0.22 μm pore-size CME (cellulose mix ester) filter (Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany).

Tacrine 1,24 the two bistacrines 9-C7/C10,23 phthalimidopropylamine 11a,19 naphthalimidopropylamine 11b,19 Δ2-isoxazolinyl tertiary base 2,17,20 isoxazole tertiary amine 3,19,20 and the bisquaternary ligands 7a-C7, 6a-C6, 6b-C6, 7b-C7,187a-C8, 7b-C8,22 and 8a-C619 were prepared according to previously reported procedures. The synthesis of the intermediates 13-C7 and 13-C10 was carried out according to ref. 24 and 25.

4.1.1. General procedure for the synthesis of phthalimido monoquaternary bromides (12a-C4, 12a-C8, 12a-C9, 12a-C10)

To a stirred solution of phthalimidopropylamine 11a (1 equiv.) in acetonitrile, the suitable alkyl dibromide (10 equiv.) was added and the reaction was refluxed for 3 days. After the reaction was completed (TLC monitoring, eluent a: CH2Cl2/MeOH = 9 : 1; eluent b: 0.2 M aqueous KNO3/MeOH = 2 : 3), about one-half of the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and diethyl ether was added. The solvent was decanted off and the residue was repeatedly washed with diethyl ether providing the desired monoquaternary intermediates.

4-Bromo-N-[3-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)propyl]-N,N-dimethylbutan-1-aminium bromide (12a-C4)

Phthalimidopropylamine 11a (1.00 g, 4.31 mmol) and 1,4-dibromobutane 12-C4 (5.1 ml, 43.1 mmol) in acetonitrile (15 ml) were used as reactants to give 12a-C4 (1.12 g, 57% yield).

Compound 12a-C4: brownish solid (from 2-propanol/diethyl ether); mp 178–181 °C; Rf = 0.52 (SiO2, 0.2 M aqueous KNO3/MeOH = 2 : 3); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.83–2.06 (m, 4H, +N–CH2–CH2–CH2), 2.18–2.38 (m, 2H, Npht–CH2–CH2), 3.22–3.53 (m, 2H, CH2–Br), 3.42 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.61–3.73 (m, 2H, CH2–N+), 3.74–3.82 (m, 2H, +N–CH2), 3.86 (t, 2H, Npht–CH2, J = 6.6), 7.63–7.78 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.79–7.87 (m, 2H, arom.). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 21.6, 22.8, 29.1, 33.2, 35.2, 51.6 (2C), 61.8, 63.3, 123.6 (2C), 131.9 (2C), 134.5 (2C), 168.4 (2C). MS (ESI) m/z [M]+ calcd for C17H24BrN2O2+: 367.1, found: 367.1.

4-Bromo-N-[3-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)propyl]-N,N-dimethylbutan-1-aminium bromide (12a-C8)

Phthalimidopropylamine 11a (1.00 g, 4.31 mmol) and 1,8-dibromooctane 12-C8 (7.9 ml, 43.1 mmol) in acetonitrile (15 ml) were used as reactants to give 12a-C8 (1.48 g, 68% yield).

Compound 12a-C8: white solid (from 2-propanol/diethyl ether); mp 149–153 °C; Rf = 0.66 (SiO2, 0.2 M aqueous KNO3/MeOH = 2 : 3); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.12–1.28 (m, 8H, +N–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.61–1.65 (m, 2H, +N–CH2–CH2), 1.67–1.72 (m, 2H, CH2–CH2–Br), 2.10–2.18 (m, 2H, Npht–CH2–CH2), 3.27 (t, 2H, CH2–Br, J = 6.6), 3.31 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.45–3.51 (m, 2H, +N–CH2), 3.58–3.65 (m, 2H, CH2–N+), 3.71 (t, Npht–CH2, J = 6.3), 7.59–7.63 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.66–7.69 (m, 2H, arom.). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 22.6, 22.9, 26.2, 28.0, 28.5, 29.1, 32.7, 34.3, 35.1, 51.5 (2C), 61.5, 64.5, 123.6 (2C), 131.9 (2C), 134.5 (2C), 168.3 (2C). MS (ESI) m/z [M]+ calcd for C21H32BrN2O2+: 423.2, found: 423.2.

9-Bromo-N-[3-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)propyl]-N,N-dimethylnonan-1-aminium bromide (12a-C9)

Phthalimidopropylamine 11a (180 mg, 0.78 mmol) and 1,9-dibromononane 12-C9 (1.6 ml, 7.75 mmol) in acetonitrile (12 ml) were used as reactants to give 12a-C9 (394 mg, 98% yield).

Compound 12a-C9: yellow foamy solid; Rf = 0.47 (SiO2, CH2Cl2/MeOH = 9 : 1); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.17–1.29 (m, 10H, +N–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.55–1.68 (m, 2H, +N–CH2–CH2), 1.68–1.77 (m, 2H, CH2–CH2–Br), 2.13–2.18 (m, 2H, Npht–CH2–CH2), 3.30 (t, 2H, CH2–Br, J = 6.6), 3.34 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.46–3.51 (m, 2H, +N–CH2), 3.62–3.67 (m, 2H, CH2–N+), 3.73 (t, 2H, Npht–CH2, J = 6.6), 7.62–7.66 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.67–7.71 (m, 2H, arom.). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 22.7, 23.0, 26.3, 28.2, 28.7, 29.2, 29.3, 32.9, 34.4, 35.2, 51.5 (2C), 61.5, 64.5, 123.6 (2C), 131.9 (2C), 134.5 (2C), 168.4 (2C). MS (ESI) m/z [M]+ calcd for C22H34BrN2O2+: 437.2, found: 437.2.

10-Bromo-N-[3-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)propyl]-N,N-dimethyldecan-1-aminium bromide (12a-C10)

Phthalimidopropylamine 11a (223 mg, 0.96 mmol) and 1,10-dibromodecane 12-C10 (2.2 ml, 9.60 mmol) in acetonitrile (12 ml) were used as reactants to give 12a-C10 (445 mg, 87% yield).

Compound 12a-C10: yellow foamy solid; Rf = 0.39 (SiO2, CH2Cl2/MeOH = 9 : 1); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.26–1.39 (m, 12H, +N–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.62–1.73 (m, 2H, +N–CH2–CH2), 1.75–1.85 (m, 2H, CH2–CH2–Br), 2.16–2.26 (m, 2H, Npht–CH2–CH2), 3.37 (t, 2H, CH2–Br, J = 6.9), 3.41 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.49–3.55 (m, 2H, +N–CH2), 3.65–3.71 (m, 2H, CH2–N+), 3.80 (t, 2H, Npht–CH2, J = 6.6), 7.68–7.72 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.75–7.79 (m, 2H, arom.). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 22.7, 23.0, 26.4, 28.3, 28.8, 29.3, 29.4 (2C), 33.0, 34.4, 35.2, 51.6 (2C), 61.6, 64.6, 123.7 (2C), 132.0 (2C), 134.6 (2C), 168.4 (2C). MS (ESI) m/z [M]+ calcd for C23H36BrN2O2+: 451.2, found: 451.2.

4.1.2. General procedure for the synthesis of 1,8-naphthalimido monoquaternary bromides (12b-C9, 12b-C10)

To a stirred solution of 1,8-naphthalimidopropylamine 11b (1 equiv.) in acetonitrile, the suitable alkyl dibromide (10 equiv.) was added and the reaction was refluxed for 5 days. After the reaction was completed (TLC monitoring, eluent a: CH2Cl2/MeOH = 9 : 1; eluent b: 0.2 M aqueous KNO3 : MeOH = 2 : 3), about one-half of the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and diethyl ether was added. The solvent was decanted off and the residue was repeatedly washed with diethyl ether, providing the desired monoquaternary intermediates.

9-Bromo-N-[3-(1,3-dioxo-1H-benzo[de]isoquinolin-2(3H)-yl)-2,2-dimethylpropyl]-N,N-dimethylnonan-1-aminium bromide (12b-C9)

1,8-Naphthalimidopropylamine 11b (180 mg, 0.58 mmol) and 1,9-dibromononane 12-C9 (1.2 ml, 5.80 mmol) in acetonitrile (12 ml) were used as reactants to give 12b-C9 (335 mg, 97% yield).

Compound 12b-C9: white solid (from diethyl ether); mp 143 °C; Rf = 0.42 (SiO2, CH2Cl2/MeOH = 9 : 1); 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 1.32–1.58 (m, 10H, +N–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.38 (s, 6H, C(CH3)2), 1.78–1.85 (m, 4H, +N–CH2–CH2–(CH2)5–CH2), 3.34 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.40 (t, 2H, CH2–Br, J = 6.6), 3.49–3.52 (m, 2H, +N–CH2), 3.55 (s, 2H, CH2–N+), 4.21 (s, 2H, Nnapht–CH2), 7.71 (t, 2H, arom., J = 7.4), 8.23 (d, 2H, arom., J = 8.3), 8.38 (d, 2H, arom., J = 7.2). 13C NMR (CD3OD): δ 22.8, 25.5 (2C), 26.2, 28.0, 28.5, 29.0, 29.1, 32.8 (2C), 33.6, 39.3, 52.3 (2C), 68.8, 72.5, 122.1 (2C), 127.1, 127.8, 131.3 (2C), 131.7 (2C), 134.6 (2C), 165.2 (2C). MS (ESI) m/z [M]+ calcd for C28H40BrN2O2+: 517.2, found: 517.2.

10-Bromo-N-[3-(1,3-dioxo-1H-benzo[de]isoquinolin-2(3H)-yl)-2,2-dimethylpropyl]-N,N-dimethyldecan-1-aminium bromide (12b-C10)

1,8-Naphthalimidopropylamine 11b (200 mg, 0.64 mmol) and 1,10-dibromodecane 12-C10 (1.5 ml, 6.44 mmol) in acetonitrile (12 ml) were used as reactants to give 12b-C10 (240 mg, 61% yield).

Compound 12b-C10: brownish solid (from diethyl ether); mp 145 °C; Rf = 0.67 (SiO2, CH2Cl2/MeOH = 9 : 1); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.19 (s, 6H, C(CH3)2), 1.26–1.37 (m, 12H, +N–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.70–1.79 (m, 4H, +N–CH2–CH2–(CH2)6–CH2), 3.31 (t, 2H, CH2–Br, J = 6.9), 3.54 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.65 (s, 2H, CH2–N+), 3.71–3.76 (m, 2H, +N–CH2), 4.28 (s, 2H, Nnapht–CH2), 7.69 (t, 2H, arom., J = 7.7), 8.19 (d, 2H, arom., J = 8.3), 8.45 (d, 2H, arom., J = 7.4). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 23.4, 26.4, 26.8 (2C), 28.3, 28.8, 29.4 (2C), 32.9, 34.4 (2C), 39.4, 48.3, 53.2 (2C), 68.4, 72.1, 122.2 (2C), 127.3 (2C), 128.2, 131.7, 132.0 (2C), 134.8 (2C), 165.3 (2C). MS (ESI) m/z [M]+ calcd for C29H42BrN2O2+: 529.2, found: 529.2.

4.1.3. General procedure for the synthesis of phthal–isox hybrids (8a-C4, 8a-C8)

To a stirred solution of the bromo intermediate (1 equiv.) in acetonitrile, the isoxazole tertiary amine 3 (1.5 equiv.) was added and the reaction was refluxed for 2 days. After the reaction was completed (TLC monitoring, eluent 0.2 M aqueous KNO3/MeOH = 2 : 3), about one-half of the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residual solid obtained was collected by filtration and purified through crystallization, providing the desired target compounds.

N 1-(3-(1,3-Dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)propyl)-N4-(4-(isoxazol-3-yloxy)but-2-yn-1-yl)-N1,N1,N4,N4-tetramethylbutane-1,4-diaminium bromide (8a-C4)

N-(4-Bromo-butyl)-phthalimidopropyl-dimethylammonium bromide 12a-C4 (1.00 g, 2.23 mmol) and tertiary amine 3 (603 mg, 3.35 mmol) in acetonitrile (20 ml) were used as reactants to give 8a-C4 (743 mg, 53% yield).

Compound 8a-C4: colorless solid (from 2-propanol/diethyl ether); mp 193–195 °C; Rf = 0.4 (SiO2, 0.2 M aqueous KNO3/MeOH = 2 : 3); 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 1.83–1.92 (m, 4H, +N–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–N+), 2.16–2.27 (m, 2H, Npht–CH2–CH2), 3.13 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.19 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.42–3.57 (m, 6H, Npht–CH2–CH2–CH2–N+–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–N+), 3.82 (t, 2H, Npht–CH2, J = 6.3), 4.43 (s, 2H, +N–CH2–C ), 5.06 (s, 2H, C–CH2–O), 6.18 (d, 1H, H-4isox, J = 1.7), 7.81–7.89 (m, 4H, arom.), 8.44 (s, 1H, H-5isox, J = 1.7). 13C NMR (CD3OD): δ 19.4, 19.6, 22.0, 34.6, 50.0 (4C), 54.2, 57.2, 62.1, 63.0, 63.2, 75.2, 86.7, 95.7, 122.9 (2C), 131.9 (2C), 134.1 (2C), 161.3, 168.4 (2C), 170.8. MS (ESI) m/z [M]+ calcd for C26H36BrN4O4+: 549.2, found: 549.2.

N 1-(3-(1,3-Dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)propyl)-N8-(4-(isoxazol-3-yloxy)but-2-yn-1-yl)-N1,N1,N8,N8-tetramethyloctane-1,8-diaminium bromide (8a-C8)

N-(8-Bromo-octyl)-phthalimidopropyl-dimethylammonium bromide 12a-C8 (1.00 g, 1.98 mmol) and tertiary amine 3 (536 mg, 2.97 mmol) in acetonitrile (20 ml) were used as reactants to give 8a-C8 (854 mg, 63% yield).

Compound 8a-C8: white solid (from 2-propanol/diethyl ether); mp 190–191 °C; Rf = 0.42 (SiO2, 0.2 M aqueous KNO3/MeOH = 2 : 3); 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 1.36–1.44 (m, 8H, +N–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.73–1.85 (m, 4H, +N–CH2–CH2–(CH2)4–CH2–CH2–N+), 2.15–2.25 (m, 2H, Npht–CH2–CH2), 3.14 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.22 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.36–3.41 (m, 2H, +N–CH2–(CH2)7), 3.46–3.51 (m, 4H, CH2–+N–(CH2)7–CH2–N+), 3.81 (t, 2H, Npht–CH2, J = 6.6), 4.49 (s, 2H, +N–CH2–C ), 5.06 (s, 2H, C–CH2–O), 6.21 (d, 1H, H-4isox, J = 1.4), 7.80–7.88 (m, 4H, arom.), 8.48 (s, 1H, H-5isox, J = 1.4). 13C NMR (CD3OD): δ 22.2, 22.3, 22.4, 24.2, 25.8, 25.9, 28.5, 34.7, 50.1 (4C), 53.9, 57.3, 63.6, 64.2, 64.4, 75.7, 86.6, 95.9, 123.1 (2C), 132.2 (2C), 134.4 (2C), 161.5, 168.6 (2C), 171.0. MS (ESI) m/z [M]+ calcd for C30H44BrN4O4+: 603.3, found: 603.3.

4.1.4. General procedure for the synthesis of phthal–iper hybrids (7a-C9, 7a-C10)

To a stirred solution of the bromo intermediate (1 equiv.) in acetonitrile, the Δ2-isoxazolinyl tertiary amine 2 (1.5 equiv.) was added and the reaction was refluxed for 5 days. After the reaction was completed (TLC monitoring, eluent 0.2 M aqueous KNO3/MeOH = 2 : 3), about one-half of the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and diethyl ether (5 ml) was added. The solvent was decanted off and the residue was repeatedly washed with diethyl ether, providing the desired target compounds.

N 1-(4-((4,5-Dihydroisoxazol-3-yl)oxy)but-2-yn-1-yl)-N9-(3-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)propyl)-N1,N1,N9,N9-tetramethylnonane-1,9-diaminium bromide (7a-C9)

N-(9-Bromo-nonyl)-phthalimidopropyl-dimethylammonium bromide 12a-C9 (330 mg, 0.64 mmol) and tertiary amine 2 (174 mg, 0.95 mmol) in acetonitrile (10 ml) were used as reactants to give 7a-C9 (405 mg, 91% yield).

Compound 7a-C9: yellow, very hygroscopic solid (from diethyl ether); Rf = 0.4 (SiO2, CH2Cl2/MeOH = 8 : 2); 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 1.31–1.44 (m, 10H, +N–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.70–1.88 (m, 4H, +N–CH2–CH2–(CH2)5–CH2), 2.15–2.25 (m, 2H, Npht–CH2–CH2), 3.03 (t, 2H, H-42-isox, J = 9.6), 3.13 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.24 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.34–3.40 (m, 2H, +N–CH2–(CH2)8), 3.45–3.54 (m, 4H, CH2–+N–(CH2)8–CH2–N+), 3.81 (t, 2H, Npht–CH2, J = 6.6), 4.39 (t, 2H, H-52-isox, J = 9.6), 4.50 (s, 2H, +N–CH2–C ), 4.92 (s, 2H, C–CH2–O), 7.81–7.89 (m, 4H, arom.). 13C NMR (CD3OD): δ 22.2, 22.4, 22.5, 26.0 (2C), 28.7, 28.9, 32.6 (2C), 34.8, 50.1 (4C), 54.1, 57.3, 61.7, 64.3 (2C), 70.1, 75.6, 86.5, 123.1 (2C), 132.2 (2C), 134.4 (2C), 167.5, 168.6 (2C). MS (ESI) m/z [M]2+ calcd for C31H48N4O42+: 270.2, found: 270.0.

N 1-(4-((4,5-Dihydroisoxazol-3-yl)oxy)but-2-yn-1-yl)-N10-(3-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)propyl)-N1,N1,N10,N10-tetramethyldecane-1,10-diaminium bromide (7a-C10)

N-(10-Bromo-decyl)-phthalimidopropyl-dimethylammonium bromide 12a-C10 (420 mg, 0.79 mmol) and tertiary amine 2 (216 mg, 1.20 mmol) in acetonitrile (8 ml) were used as reactants to give 7a-C10 (496 mg, 88% yield).

Compound 7a-C10: brownish, very hygroscopic solid (from diethyl ether); Rf = 0.3 (SiO2, CH2Cl2/MeOH = 9 : 1). 1H–NMR (CD3OD): δ 1.32–1.44 (m, 12H, +N–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.70–1.86 (m, 4H, +N–CH2–CH2–(CH2)6–CH2), 2.16–2.26 (m, 2H, Npht–CH2–CH2), 3.03 (t, 2H, H-42-isox, J = 9.6), 3.14 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.25 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.33–3.38 (m, 2H, +N–CH2–(CH2)9), 3.41–3.50 (m, 4H, CH2–+N–(CH2)9–CH2–N+), 3.81 (t, 2H, Npht–CH2, J = 6.3), 4.39 (t, 2H, H-52-isox, J = 9.6), 4.51 (s, 2H, +N–CH2–C ), 4.92 (s, 2H, C–CH2–O), 7.81–7.88 (m, 4H, arom.). 13C NMR (CD3OD): δ 22.2, 22.4, 22.6, 26.1, 26.2, 28.9, 28.9, 29.1, 32.6 (2C), 34.8, 50.2 (2C), 50.4 (2C), 54.1, 57.3, 61.7, 64.4, 64.5, 70.1, 75.7, 86.4, 123.2 (2C), 132.2 (2C), 134.5 (2C), 167.5, 168.7 (2C). MS (ESI) m/z [M]2+ calcd for C32H50N4O42+: 277.2, found: 277.0.

4.1.5. General procedure for the synthesis of naphthal–iper hybrids (7b-C9, 7b-C10)

To a stirred solution of bromo intermediate (1 equiv.) in acetonitrile, Δ2-isoxazolinyl tertiary amine 2 (1.5 equiv.) was added and the reaction was refluxed for 3 days. After the reaction was completed (TLC monitoring, eluent 0.2 M aqueous KNO3/MeOH = 2 : 3), about one-half of the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and diethyl ether was added. The solvent was decanted off and the residue was repeatedly washed with diethyl ether, providing the desired target compounds.

N 1-(4-((4,5-Dihydroisoxazol-3-yl)oxy)but-2-yn-1-yl)-N9-(3-(1,3-dioxo-1H-benzo[de]isoquinolin-2(3H)-yl)-2,2-dimethylpropyl)-N1,N1,N9,N9-tetramethylnonane-1,9-diaminium bromide (7b-C9)

N-(9-Bromo-nonyl)-1,8-naphthalimidopropyl-dimethylammonium bromide 12b-C9 (242 mg, 0.41 mmol) and tertiary amine 2 (111 mg, 0.61 mmol) in acetonitrile (3 ml) were used as reactants to give 7b-C9 (300 mg, 95% yield).

Compound 7b-C9: yellow solid; mp 185 °C; Rf = 0.59 (SiO2, CH2Cl2/MeOH = 9 : 1); 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 1.32 (s, 6H, C(CH3)2), 1.36–1.46 (m, 10H, +N–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.74–1.82 (m, 4H, +N–CH2–CH2–(CH2)5–CH2), 3.01 (t, 2H, H-42-isox, J = 9.6), 3.24 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.33 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.48–3.54 (m, 4H, +N–CH2–(CH2)7–CH2–N+), 3.56 (s, 2H, CH2–N+), 4.25 (s, 2H, Nnapht–CH2), 4.37 (t, 2H, H-52-isox, J = 9.6), 4.50 (s, 2H, +N–CH2–C ), 4.90 (s, 2H, C–CH2–O), 7.77 (t, 2H, arom., J = 7.7), 8.31 (d, 2H, arom., J = 8.3), 8.45 (d, 2H, arom., J = 7.2). 13C NMR (CD3OD): δ 22.5, 22.8, 25.5, 26.0, 26.1, 28.7, 28.8, 28.9, 32.6 (2C), 39.4, 50.1 (2C), 52.2 (2C), 54.1, 57.3, 64.3, 68.8 (2C), 70.1, 72.6, 75.6, 86.5, 122.2 (2C), 127.1 (2C), 127.9, 131.3 (2C), 131.8, 134.6 (2C), 165.4 (2C), 167.5. MS (ESI) m/z [M]2+ calcd for C37H54N4O42+: 309.2, found: 309.2.

N 1-(4-((4,5-Dihydroisoxazol-3-yl)oxy)but-2-yn-1-yl)-N10-(3-(1,3-dioxo-1H-benzo[de]isoquinolin-2(3H)-yl)-2,2-dimethylpropyl)-N1,N1,N10,N10-tetramethyldecane-1,10-diaminium bromide (7b-C10)

N-(10-Bromo-decyl)-1,8-naphthalimidopropyl-dimethylammonium bromide 12b-C10 (175 mg, 0.29 mmol) and tertiary amine 2 (78 mg, 0.43 mmol) in acetonitrile (6 ml) were used as reactants to give 7b-C10 (211 mg, 93% yield).

Compound 7b-C10: brownish solid; mp 186 °C; Rf = 0.2 (SiO2, CH2Cl2/MeOH = 9 : 1); 1H NMR (CD3OD): δ 1.33 (s, 6H, C(CH3)2), 1.37–1.46 (m, 12H, +N–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.77–1.85 (m, 4H, +N–CH2–CH2–(CH2)6–CH2), 3.01 (t, 2H, H-42-isox, J = 9.6), 3.21 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.31 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.45–3.51 (m, 4H, +N–CH2–(CH2)8–CH2–N+), 3.55 (s, 2H, CH2–N+), 4.28 (s, 2H, Nnapht–CH2), 4.38 (t, 2H, H-52-isox, J = 9.6), 4.46 (s, 2H, +N–CH2–C ), 4.90 (s, 2H, C–CH2–O), 7.81 (t, 2H, arom., J = 8.0), 8.35 (d, 2H, arom., J = 8.3), 8.52 (d, 2H, arom., J = 7.2). 13C NMR (CD3OD): δ 22.5, 22.8, 25.4, 26.1, 26.2, 28.9, 29.0, 29.1 (2C), 32.5 (2C), 39.3, 50.1 (2C), 52.2 (2C), 54.0, 57.2, 64.3, 68.8 (2C), 70.0, 72.6, 75.5, 86.4, 122.3 (2C), 127.1 (2C), 128.0, 131.4 (2C), 132.0, 134.6 (2C), 165.5 (2C), 167.5. MS (ESI) m/z [M]2+ calcd for C38H56N4O42+: 316.2, found: 316.4.

4.1.6. General procedure for the synthesis of the tac–iper hybrids (10-C7, 10-C10)

To a solution of given amounts of intermediate bromide in 15 ml of acetonitrile 2 equiv. of the Δ2-isoxazolinyl tertiary amine 2 and a catalytic amount of KI/K2CO3 (1 : 1) were added. The reaction mixture was heated in the microwave (500 W, 80 °C) for 4 h. After cooling to room temperature excess KI/K2CO3 was filtered and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. The residue obtained was purified via column chromatography (Alox, CH2Cl2 : MeOH = 9 : 1), providing the target compounds.

N-(4-((4,5-Dihydroisoxazol-3-yl)oxy)but-2-yn-1-yl)-N,N-dimethyl-7-((1,2,3,4-tetrahydroacridin-9-yl)amino)heptan-1-aminium bromide 10-C7

N-(7-Bromoheptyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroacridin-9-amine 13-C7 (300 mg, 0.80 mmol) reacted with tertiary amine 2 (291 mg, 1.60 mmol) to obtain the target compound 10-C7 (188 mg, 42% yield).

Compound 10-C7: yellowish, hygroscopic solid; Rf = 0.42 (Alox, CH2Cl2 : MeOH = 9 : 1); 1H NMR (DMSO): 1.23–1.29 (m, 6H, NH–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.54–1.65 (m, 4H, CH2–CH2–N+/NH–CH2–CH2), 1.81–1.86 (m, 4H, C2–H2/C3–H2), 2.71 (t, 2H, C1–H2, J = 5.9), 2.90 (t, 2H, C4–H2, J = 6.2), 2.99 (t, 2H, H-42-isox, J = 9.6), 3.04 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.27–3.34 (m, 2H, CH2–N+), 3.38–3.43 (m, 2H, NHCH2), 4.29 (t, 2H, H-52-isoxJ = 9.6), 4.41 (br, 2H, +N–CH2–C ), 4.92 (br, 2H, C–CH2–O), 5.41 (t, 1H, NH, J = 6.1), 7.34 (ddd, 1H, C7–H, J = 1.3, J = 6.8, J = 8.2), 7.52 (ddd, 1H, C6–H, J = 1.3, J = 6.8, J = 8.3), 7.70 (dd, 1H, C5–H, J = 1.0, J = 8.4), 8.11 (d, 1H, C8–H, J = 8.1). 13C NMR (DMSO): 21.6, 22.4, 22.6, 25.0, 25.5, 26.0, 28.1, 30.4, 32.1, 33.4, 47.8, 49.7, 53.2, 57.1, 63.1, 69.5, 76.0, 85.9, 115.7, 120.1, 122.9, 123.1, 127.8, 128.1, 146.7, 150.3, 157.8, 166.6. MS (ESI) m/z [M]+ calcd for C29H41N4O2+: 477.3, found: 477.4.

N-(4-((4,5-Dihydroisoxazol-3-yl)oxy)but-2-yn-1-yl)-N,N-dimethyl-10-((1,2,3,4-tetrahydroacridin-9-yl)amino)decan-1-aminium bromide 10-C10

N-(10-Bromodecyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroacridin-9-amine 13-C10 (305 mg, 0.73 mmol) reacted with tertiary amine 1 (266 mg, 1.46 mmol) to obtain the target compound 10-C10 (44.0 mg, 10% yield).

Compound 10-C10: brown, hygroscopic solid; Rf = 0.41 (Alox, CH2Cl2 : MeOH = 9 : 1); 1H NMR (DMSO): 1.21–1.24 (m, 12H, NH–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2–CH2), 1.51–1.58 (m, 2H, NH–CH2–CH2), 1.62–1.65 (m, 2H, CH2–CH2–N+), 1.81–1.84 (m, 4H, C2–H2/C3–H2), 2.70 (t, 2H, C1–H2, J = 5.9), 2.90 (t, 2H, C4–H2, J = 6.1), 3.00 (t, 2H, H-42-isox, J = 9.6), 3.06 (s, 6H, +N(CH3)2), 3.29–3.33 (m, 2H, CH2–N+), 3.38–3.44 (m, 2H, NH–CH2), 4.30 (t, 2H, H-52-isox, J = 9.6), 4.42 (s, 2H, +N–CH2–C ), 4.93 (s, 2H, C–CH2–O), 5.47 (br, 1H, NH), 7.34 (ddd, 1H, C7–H, J = 1.2, J = 6.8, J = 8.1), 7.51–7.55 (m, 1H, C6–H), 7.70 (dd, 1H, C5–H, J = 1.0, J = 8.4), 8.11 (d, 1H, C8–H, J = 8.1). 13C NMR (DMSO): 21.7, 22.3, 22.6, 24.9, 25.5, 26.1, 28.3, 28.5, 28.6, 28.7, 30.4, 32.1, 33.1, 47.7, 49.7, 53.2, 57.1, 63.1, 69.5, 76.0, 85.9, 115.5, 119.9, 123.0, 123.1, 128.0, 147.2, 150.5, 157.4, 166.6. MS (ESI) m/z [M]+ calcd for C32H47N4O2+: 519.4, found: 519.5.

4.2. Pharmacology

4.2.1. AChE/BChE inhibition

The determination of IC50 values for AChE and BChE inhibition by all the compounds was performed according to a known procedure based on the Ellman assay.46 AChE (E.C. 3.1.1.7, from electric eel) and BChE (E.C. 3.1.1.8, from equine serum) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). hAChE, (E.C. 3.1.1.7, a recombinant expressed in HEK 293 cells) was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany) and hBChE (E.C. 3.1.1.8, from human serum) was kindly donated by Dr. Oksana Lockridge (University of Nebraska Medical Center). DTNB (Ellman's reagent), ATC and BTC iodides were obtained from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland). For buffer preparation, 2.40 g of potassium dihydrogen phosphate were dissolved in 500 ml of water and adjusted with a NaOH solution (0.1 M) to pH 8.0. Enzyme solutions were prepared with buffer to give 2.5 units per ml and stabilized with 2 mg bovine serum albumin (SERVA, Heidelberg, Germany) per ml of enzyme solution. 396 mg of DTNB were dissolved in 100 ml of buffer to give a 10 mM solution (0.3 mM in assay). The stock solutions of the test compounds were prepared either in pure buffer (1, 9-C7, and 9-C10), in a 50%/50% mixture of buffer/ethanol (7a-C10, 8a-C6, 6b-C6, 7b-C8, 7b-C9, 7b-C10, 10-C10, and 10-C7) or in pure ethanol (7a-C7, 7a-C8, 7a-C9, 8a-C4, 8a-C8, 6a-C6, 7b-C7, 13-C7, and 13-C10) with a concentration of 33.3 mM (1 mM in assay) and diluted stepwise with ethanol to a concentration of 33.3 nM (1 nM in assay). The highest concentration of the test compounds applied in the assay was 10–3 M (the amount of EtOH in the stock solution did not influence the enzyme activity in the assay). The assay was performed at 25 °C according to the following procedure: a cuvette containing 1.5 ml of buffer, 50 μL of DTNB solution, 50 μL of the respective enzyme and 50 μL of the test compound solution was incubated for 4.5 min. Then the reaction was started by addition of 10 μL of the substrate solution (ATC/BTC). The solution was mixed immediately and incubated for a further 2.5 min. Then the absorption was measured at 412 nm using a Shimadzu UVmini-1240 spectrophotometer (Duisburg, Germany). To measure the full enzyme activity, 50 μL of buffer replaced the test compound solution. For determining the blank value, additionally 50 μL of buffer replaced the enzyme solution. Each test compound concentration was measured in triplicate. The percentage enzyme activity was plotted against the logarithm of the compound concentrations from which the IC50 values were calculated with the GraphPad Prism software.

4.2.2. M2- and M1-receptor binding measurements

Cell culture and preparation of membranes. Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO cells) endowed with the human M2- or M1-receptor gene by stable transfection were generously provided by Dr. N. J. Buckley, University of Leeds, UK. Cells were cultured and processed as reported earlier.47 The membrane pellets obtained were washed twice in 20 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM Na4EDTA, pH 7.4, 4 °C (storage buffer) and the final pellets were stored as a membrane suspension in storage buffer at –80 °C. The Lowry method was applied to determine the protein content which amounted to 3.8 mg per ml of membrane suspension.

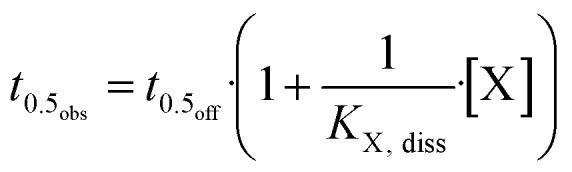

Binding experiments. [3H]NMS filtration binding experiments were carried out as described previously.48 In 1.2 ml 96-deep well microplates (Abgene House, Epsom, UK), membranes were added to 400 μl of incubation buffer (10 mM HEPES, 10 mM MgCl2, and 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, at 30 °C). In [3H]NMS equilibrium binding experiments 0.2 nM [3H]NMS and 25–40 μg protein per ml of membranes were applied. Nonspecific [3H]NMS binding was estimated in the presence of 1 μM atropine and did not exceed 5% of total radioligand binding. Under control conditions specific binding of [3H]NMS was characterized by a negative log equilibrium dissociation constant, logKD,M2 = –9.12 ± 0.10 and logKD,M1 = –9.42 ± 0.04 (mean ± SEM, n = 6). In homologous and heterologous competition experiments with [3H]NMS the incubation time amounted to 2 h and 2–4 h, respectively. In order to calculate the incubation time necessary to equilibrate [3H]NMS binding in the presence of an allosteric test compound the following equation was used:

|

1 |

t 0.5obs is an estimate of [3H]NMS association half-life in the presence of the allosteric test compound X, t0.5off is the half-life of [3H]NMS dissociation in the absence of allosteric modulator (t0.5off,M2 = 2.1 ± 0.03, means ± SEM, n = 12; t0.5off,M1 = 7.4 ± 0.54, means ± SEM, n = 12), and KX,diss indicates the modulator concentration at which the half-life of [3H]NMS dissociation is doubled. Equilibrium was assumed to be reached after 5 × t0.5obs.

In dissociation experiments, membranes were incubated with [3H]NMS for 30 minutes (M2) or 60 minutes (M1) at 30 °C. Then, aliquots of this mixture were added to excess unlabelled ligand in buffer over a total period of 120 min followed by simultaneous filtration of all samples. In order to determine the effect of the test compounds on the dissociation of [3H]NMS, dissociation was measured by the addition of 1 μM atropine in combination with the respective test compounds. Three-point kinetic experiments were performed in analogy to two-point kinetic experiments49 with measurements of [3H]NMS binding at t = 0.5, 5 and 8 min at M2 and t = 0.5, 14 and 17 min at M1 receptors.

Receptor bound radioligand was separated by filtration on a Tomtech 96-well Mach III Harvester (Wallac®) using glass fibre filtermats (Filtermat A®, Wallac, Turku, Finland) which had been pretreated with 0.2% polyethyleneimine (M2: 0.2%, M1: 0.1%). The filtration was followed by two rapid washing steps (aqua purificata, at 4 °C) whereafter the filtermats were dried for 3 min at 400 W in a microwave oven. Finally, scintillation wax (Meltilex® A, Wallac, Turku, Finland) was melted for 1 min at 90 °C onto the filtermat using a Dri-Block® DB-2A (Techne, Duxford Cambridge, UK). After placing the filters in sample bags (Wallac, Turku, Finland) filter bound radioactivity was measured using a Microbeta Trilux-1450 scintillation counter (Wallac, Turku, Finland).

Data analysis. Computer-aided, non-linear regression analysis using Prism 5.03 (GraphPad Software®, San Diego, CA, USA) was applied to analyse the binding data from individual experiments. [3H]NMS dissociation data were analysed assuming a monoexponential decay. The ability of the allosteric agents to retard [3H]NMS dissociation was expressed as the % reduction of the apparent rate constant k–1 for [3H]NMS dissociation. The concentration–effect curves (CECs) for the reduction of the [3H]NMS dissociation rate constant k–1 and of [3H]NMS specific binding by the test compounds were fitted to a four parameter logistic function. The upper plateau was the value of k–1 measured in the absence of test compound and was fixed at 100%, whereas the log inflection point (log IC50) and slope factors n were set as variables. The bottom plateau was checked as to whether it, as a variable, yielded a significantly better fit compared with it being fixed at 0%. Finally, we tested whether the slope factors of the curves were different from unity. In all statistical comparisons an F-test was applied and P < 0.05 was chosen as the level of statistical significance. Applying the four parameter logistic function, the log IC50-values were estimated with n constrained to –1 if the observed slope factors did not differ significantly from unity. The inflection point of a CEC for the retarding action of the test compound on radioligand dissociation stands for an effect and thus was designated log KX,diss. In homologous competition binding experiments, the KD value for the radioligand was calculated according to DeBlasi et al.50 In heterologous competition binding experiments, performed in parallel under identical experimental conditions with respect to membranes, radioligand affinity and concentration, the log IC50 values for the hybrid compounds were taken to reflect a model-independent measure of binding affinity and were used for comparisons.

4.3. Cytotoxicity

The compounds to be tested were solubilised and serially diluted in DMSO. 1 × 105 HEPG2 (ATCC) cells per ml were incubated in a volume of 200 μL in 96-well cell culture plates in RPMI medium (Gibco) with 10% FCS (PAA) without phenol red with serial compound dilutions at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 72 h. The final concentration of DMSO was 1%. After 24 h of incubation, 10% of an AlamarBlue solution (Trinova) was added. The IC50 value was calculated with respect to controls without compounds from the absorbance values measured at 550 nm using 630 nm as the reference wavelength.

4.4. Log P determination by means of RP HPLC34

The partition coefficients of the compounds 7a-C7, 7a-C8, 7a-C9, 7a-C10, 8a-C4, 8a-C6, 8a-C8, 6a-C6, 6b-C6, 7b-C7, 7b-C8, 7b-C9, 7b-C10, 10-C10, and 10-C7 were determined by RP chromatography using methanol/phosphate buffer 70 : 30 as eluent. The phosphate buffer was prepared by dissolving potassium dihydrogen phosphate in water (0.02 M) and adding aqueous sodium hydroxide solution (0.1 M) to adjust the pH to 8. Liquid chromatography was conducted on an Agilent 1100 series system using a C18 reversed-phase (Knauer, Germany) (150 × 4.6 mm) column. The mobile phase (MeOH/phosphate buffer = 70/30) was used at a flow rate of 1.5 ml min–1. The chromatographic systems were calibrated with solutes (2-butanone, acetanilide, 2-phenylethanol, benzene, toluene, chlorobenzene, ethylbenzene, biphenyl) for which an experimental octanol/water partition coefficient was available.51 The testing compounds 7a-C7, 7a-C8, 7a-C9, 7a-C10, 8a-C4, 8a-C6, 8a-C8, 6a-C6, 6b-C6, 7b-C7, 7b-C8, 7b-C9, 7b-C10, 10-C10, and 10-C7 were dissolved in MeOH (100 μg ml–1). Experiments were run in triplicate. The peak maxima were measured at 254 nm. Capacity ratio was calculated using the following equation: k′ = (tr – to)/to. tr is the average retention time of the analyte and to is the average retention time of the solvent. A linear regression was performed for the log k′/log P data of the reference compounds to obtain a correlation equation (y = 2.348x + 1.3027; R2 = 0.9813) which was used for the calculation of the log P values of the compounds (Tables S3 and S4, ESI‡).

4.5. Computational studies

Docking studies were performed according to a previously developed protocol for bis-tacrine compounds.38 Briefly, the TcAChE crystal structure with PDB ID ; 2CKM was chosen due to its high resolution of 2.15 Å.39,52 This isoform is complexed with a bis-tacrine ligand; accordingly, the PAS-forming residues Tyr70 and Trp279 show a parallel orientation with the second tacrine unit binding between them in a sandwich-type π–π interaction. This particular orientation of the PAS residues is not present in any hAChE crystal structure known to date. However, a reorientation of the amino acids according to an induced-fit process seems reasonable also for other isoforms of AChE.

Although the inhibition data were obtained with eeAChE, a TcAChE crystal structure was used for the docking studies because of the much higher resolution in comparison to the low-resolution (>4.20 Å) structure of eeAChE. Both isoforms show high homologies with respect to the hAChE (Table S5, ESI‡).

Docking settings were previously reported by Chen et al.38 Briefly, Gold 5.2.2,53,54 was used with 4 000 000 as the number of operations and the scoring function ASP,55 generating 50 poses for 7b-C10 and 10-C10. The protonation of the protein and the ligands was performed at pH 8, which reflects Ellman assay conditions. Ligand protonation states were calculated using MoKα,56 which indicated a protonated acridinic nitrogen of the tacrine moiety.

Following the approach of Chen et al., a scaffold match constraint was used for docking of 10-C10.38 A representative binding pose was identified as the top ASP pose (score: 85.50), which also yielded the best DSX score (–183.41). The scaffold of 7b-C10 was extracted from the second-best pose (ASP) due to its large overlap with the tacrine scaffold. In a docking using this scaffold, the second best ranked ASP pose (score: 76.71) was also the top pose in rescoring with DSX (–181.81) and thus chosen as the representative binding pose. 7a-C10 was created through a modeling approach by elimination and addition of the required atoms in the 7b-C10 docking solution (rank 1, ASP) according to the protocol used by Sawatzky et al.57 The isoindoline-dione motif was minimized to an RMSD gradient of 0.001 kcal mol–1·Å–1 to achieve planarity by keeping all other atoms fixed. The so designed ligand was locally minimized in the binding site using MinMuDS58 with CSD potentials (final DSX score: –153.39).59

A 3D-RISM calculation was performed with default settings in MOE 2016.05,42 using the 7b-C10 and 10-C10 docking poses and ; 2CKM binding site atoms within 8 Å around the ligand.

Solvation free energies were calculated with the SMD method, a parameterized SCRF-based solvation model developed by Truhlar and coworkers, which is based on the quantum mechanical charge density of the solute molecule interacting with a continuum description of the solvent.43 The tetramethylammonium and n-propane model compounds were built and preminimized (with MMFF94s) in MOE. Quantum chemical calculations with the SMD solvation model were carried out with Gaussian09 Revision C.0160 at the HF/6-31G* level of theory (full geometry optimization). Instead of calculating the transfer free energies from the gas phase to water (which leads to overestimation of the desolvation penalties,61 in particular for charged compounds), the transfer free energies from water (ε = 78.3553) to n-octanol (ε = 9.8629) (obtained from SCRF/SMD calculations with water and n-octanol as solvents, respectively) were used to estimate the desolvation free energy.

Abbreviations

- ACh

Acetylcholine

- AChE

Acetylcholinesterase

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ATC

Acetylthiocholine

- BChE

Butyrylcholinesterase

- BTC

Butyrylthiocholine

- CAS

Catalytic active site

- DTNB

Dithionitrobenzoic acid

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- M1

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype 1

- M2

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype 2

- RMSD

Root mean square deviation

- PAS

Peripheral anionic site

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the German Academic National Foundation (Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes) for awarding a Ph.D. scholarship to S. Wehle. The skillful technical assistance of Mechthild Kepe, Iris Jusen and Matthias Hoffmann is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank the Institute for Molecular Infection Biology of the University of Würzburg (Germany) for evaluation of the cytotoxicity.

Footnotes

†The authors declare no competing interests.

‡Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: M2 and M1 binding experiments, log P values and sequence alignment for acetylcholinesterases. See DOI: 10.1039/c7md00149e

References

- Deutsche Alzheimer Gesellschaft, Factsheet “Das Wichtigste 1 – Die Häufigkeit von Demenzerkrankungen”, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard C., Gauthier S., Corbett A., Brayne C., Aarsland D., Jones E. Lancet. 2011;377:1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soreq H., Seidman S. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:294–302. doi: 10.1038/35067589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet Y., Lockridge O., Masson P., Fontecilla-Camps J. C., Nachon F. J. Biolumin. Chemilumin. 2003;278:41141–41147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacobini E. Pharmacol. Res. 2004;50:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasker A., Perry E. K., Ballard C. G. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2005;5:101–106. doi: 10.1586/14737175.5.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geula C., Darvesh S. Drugs Today. 2004;40:711–721. doi: 10.1358/dot.2004.40.8.850473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimmer T., Kurz A. Drugs Aging. 2006;23:957–967. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623120-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Torrero D. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008;15:2433–2455. doi: 10.2174/092986708785909067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins P. B., Zimmerman H. J., Knapp M. J., Gracon S. I., Lewis K. W. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1994;271:992–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange J. H., Coolen H. K., van der Neut M. A., Borst A. J., Stork B., Verveer P. C., Kruse C. G. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:1338–1346. doi: 10.1021/jm901614b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L., Jumpertz S., Zhang Y., Appenroth D., Fleck C., Mohr K., Tränkle C., Decker M. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:2094–2103. doi: 10.1021/jm901616h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Zenger K., Lupp A., Kling B., Heilmann J., Fleck C., Kraus B., Decker M. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:5231–5242. doi: 10.1021/jm300246n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreiras M. C., Soriano E., Marco J. L. Bioact. Heterocycl. 2013:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Romero A., Cacabelos R., Oset-Gasque M. J., Samadi A., Marco-Contelles J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:1916–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Y. P., Hong F., Quiram P., Jelacic T., Brimijoin S. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1997:171–176. doi: 10.1039/a601642a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kloeckner J., Schmitz J., Holzgrabe U. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:3470–3472. [Google Scholar]

- Matera C., Flammini L., Quadri M., Vivo V., Ballabeni V., Holzgrabe U., Mohr K., De Amici M., Barocelli E., Bertoni S., Dallanoce C. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;75:222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disingrini T., Muth M., Dallanoce C., Barocelli E., Bertoni S., Kellershohn K., Mohr K., De Amici M., Holzgrabe U. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:366–372. doi: 10.1021/jm050769s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallanoce C., Conti P., De Amici M., De Micheli C., Barocelli E., Chiavarini M., Ballabeni V., Bertoni S., Impicciatore M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999;7:1539–1547. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barocelli E., Ballabeni V., Bertoni S., De Amici M., Impicciatore M. Life Sci. 2001;68:1775–1785. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)00973-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock A., Merten N., Schrage R., Dallanoce C., Batz J., Kloeckner J., Schmitz J., Matera C., Simon K., Kebig A., Peters L., Müller A., Schrobang-Ley J., Tränkle C., Hoffmann C., De Amici M., Holzgrabe U., Kostenis E., Mohr K. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:1044. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier P. R., Han Y. F., Chow E. S.-H., Li C. P.-L., Wang H., Lieu T. X., Wong H. S., Pang Y. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999;7:351–357. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Chen J., Chen X., Huang L., Li X. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:7406–7417. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camps P., Formosa X., Munoz-Torrero D., Petrignet J., Badia A., Clos M. V. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:1701–1704. doi: 10.1021/jm0496741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy R. Lancet. 1987;1:322. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Carlier P. R., Ho W. L., Wu D. C., Lee N. T., Li C. P., Pang Y. P., Han Y. F. NeuroReport. 1999;10:789–793. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199903170-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y. F., Li C. P., Chow E., Wang H., Pang Y. P., Carlier P. R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999;7:2569–2575. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony J., Kellershohn K., Mohr-Andra M., Kebig A., Prilla S., Muth M., Heller E., Disingrini T., Dallanoce C., Bertoni S., Schrobang J., Tränkle C., Kostenis E., Christopoulos A., Holtje H. D., Barocelli E., De Amici M., Holzgrabe U., Mohr K. FASEB J. 2009;23:442–450. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-114751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer-Day J. S., Campbell H. E., Towles J., el-Fakahany E. E. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991;203:421–423. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90901-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrage R., Seemann W. K., Kloeckner J., Dallanoce C., Racke K., Kostenis E., De Amici M., Holzgrabe U., Mohr K. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013;169:357–370. doi: 10.1111/bph.12003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrage R., Holze J., Klöckner J., Balkow A., Klause A. S., Schmitz A. L., De Amici M., Kostenis E., Tränkle C., Holzgrabe U., Mohr K. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014;90:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao K., Fujikawa M., Shimizu R., Akamatsu M. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2009;23:309–319. doi: 10.1007/s10822-009-9261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alptüzün V., Prinz M., Hörr V., Scheiber J., Radacki K., Fallarero A., Vuorela P., Engels B., Braunschweig H., Erciyas E., Holzgrabe U. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:2049–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C. A., Lombardo F., Dominy B. W., Feeney P. J. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet-Personeni C., Bentley P. D., Fletcher R. J., Kinkaid A., Kryger G., Pirard B., Taylor A., Taylor R., Taylor J., Viner R., Silman I., Sussman J. L., Greenblatt H. M., Lewis T. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:3203–3215. doi: 10.1021/jm010826r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier P. R., Du D. M., Han Y., Liu J., Pang Y. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:2335–2338. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Wehle S., Kuzmanovic N., Merget B., Holzgrabe U., Konig B., Sotriffer C. A., Decker M. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014;5:377–389. doi: 10.1021/cn500016p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydberg E. H., Brumshtein B., Greenblatt H. M., Wong D. M., Shaya D., Williams L. D., Carlier P. R., Pang Y. P., Silman I., Sussman J. L. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:5491–5500. doi: 10.1021/jm060164b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel M., Schalk I., Ehret-Sabatier L., Bouet F., Goeldner M., Hirth C., Axelsen P. H., Silman I., Sussman J. L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:9031–9035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissantz C., Kuhn B., Stahl M. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:5061–5084. doi: 10.1021/jm100112j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical Computing Group, Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), 2016.05, 1010 Sherbooke St. West, Suite No. 910, Montreal, QC, H3A 2R7, Canada.

- Marenich A. V., Cramer C. J., Truhlar D. G. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:6378–6396. doi: 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragendorff G., Verlag der Kaiserlichen Hochbuchhandlung Heinrich Schmitzdorff (Karl Böttger), Sankt Petersburg, 1872, vol. 1. Auflage, p. 312. [Google Scholar]

- Nayeem AA K. A., Rahman M. S., Rahman M. J. Pharmacogn. Phytother. 2011;3:118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ellman G. L., Courtney K. D., Andres, Jr. V., Feather-Stone R. M. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tränkle C., Weyand O., Voigtlander U., Mynett A., Lazareno S., Birdsall N. J., Mohr K. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;64:180–190. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tränkle C., Dittmann A., Schulz U., Weyand O., Buller S., Johren K., Heller E., Birdsall N. J., Holzgrabe U., Ellis J., Holtje H. D., Mohr K. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;68:1597–1610. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostenis E., Mohr K. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1996;17:280–283. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)10034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBlasi A., Oreilly K., Motulsky H. J. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1989;10:227–229. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(89)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansch C., Leo A. and Hoekman D., Exploring QSAR: Volume 2: Hydrophobic, Electronic and Steric Constants, American Chemical Society, Washington DC, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein F. C., Koetzle T. F., Williams G. J. B., Meyer E. F., Brice M. D., Rodgers J. R., Kennard O., Shimanouchi T., Tasumi M. J. Mol. Biol. 1977;112:535–542. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(77)80200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCDCSoftware. GOLDSUITE 5.2, www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk.

- Verdonk M. L., Cole J. C., Hartshorn M. J., Murray C. W., Taylor R. D. Proteins. 2003;52:609–623. doi: 10.1002/prot.10465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooij W. T., Verdonk M. L. Proteins. 2005;61:272–287. doi: 10.1002/prot.20588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milletti F., Storchi L., Sforna G., Cruciani G. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007;47:2172–2181. doi: 10.1021/ci700018y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawatzky E., Wehle S., Kling B., Wendrich J., Bringmann G., Sotriffer C. A., Heilmann J., Decker M. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:2067–2082. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzmüller A., Velec H. F. G., Klebe G. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:1423–1430. doi: 10.1021/ci200098v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neudert G., Klebe G. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:2731–2745. doi: 10.1021/ci200274q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J., Trucks G. W., Schlegel H. B., Scuseria G. E., Robb M. A., Cheeseman J. R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G. A., Nakatsuji H., Caricato M., Li X., Hratchian H. P., Izmaylov A. F., Bloino J., Zheng G., Sonnenberg J. L., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Montgomery Jr J. A.., Peralta J. E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M., Heyd J. J., Brothers E., Kudin K. N., Staroverov V. N., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A., Burant J. C., Iyengar S. S., Tomasi J., Cossi M., Rega N., Millam J. M., Klene M., Knox J. E., Cross J. B., Bakken V., Adamo C., Jaramillo J., Gomperts R., Stratmann R. E., Yazyev O., Austin A. J., Cammi R., Pomelli C., Ochterski J. W., Martin R. L., Morokuma K., Zakrzewski V. G., Voth G. A., Salvador P., Dannenberg J. J., Dapprich S., Daniels A. D., Farkas Ö., Foresman J. B., Ortiz J. V., Cioslowski J. and Fox D. J., Gaussian 09 Revision C.01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT.

- Mysinger M. M., Shoichet B. K. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010;50:1561–1573. doi: 10.1021/ci100214a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.