Abstract

Resection of double-strand breaks (DSBs) dictates the choice between Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), which requires a 3′ overhang, and classical Non-Homologous End Joining (c-NHEJ), which can join unresected ends1,2. BRCA1 mutant cancers show minimal DSB resection, rendering them HDR deficient and sensitive to PARP1 inhibitors (PARPi)3–8. When BRCA1 is absent, DSB resection is thought to be prevented by 53BP1, Rif1, and the Rev7/Shld1/Shld2/Shld3 (Shieldin) complex and loss of these factors diminishes PARPi sensitivity4,6–9. Here we address the mechanism by which 53BP1/Rif1/Shieldin regulate the generation of recombinogenic 3′ overhangs. We report that CST (Ctc1, Stn1, Ten110), an RPA-like complex that functions as a Polymeraseα/primase accessory factor11 is a downstream effector in the 53BP1 pathway. CST interacts with Shieldin and localizes with Polα to sites of DNA damage in a 53BP1- and Shieldin-dependent manner. Like loss of 53BP1/Rif1/Shieldin, CST depletion leads to increased resection. Furthermore, in BRCA1-deficient cells, CST blocks Rad51 loading and promotes PARPi efficacy. Finally, Polα inhibition diminishes the effect of PARPi in BRCA1-deficient cells. These data suggest that CST/Polα-mediated fill-in contributes to the control of DSB repair by 53BP1, Rif1, and Shieldin.

Keywords: DNA repair, 5′ end resection, 53BP1, Rif1, Shieldin, CST, BRCA1, PARPi, Polymerase α/primase, fill-in synthesis

This study was initiated to determine whether the control of 5′ resection at DSBs resembles the regulation of resection at telomeres. Formation of telomeric t-loops requires generation of 3′ overhangs after DNA replication12,13,14,15. Newly-replicated telomeres are resected by Exo1, generating 3′ overhangs that are too long and require Polα/primase-mediated fill-in16 (Fig. 1a). Polα/primase is brought to telomeres by an interaction between CST (also called AAF11,17) and POT1b in mouse shelterin16 (Fig. 1a). Here we test whether CST/Polα fill-in of 3′ overhangs plays a role in the regulation of DSB resection by 53BP1/Rif1/Shieldin.

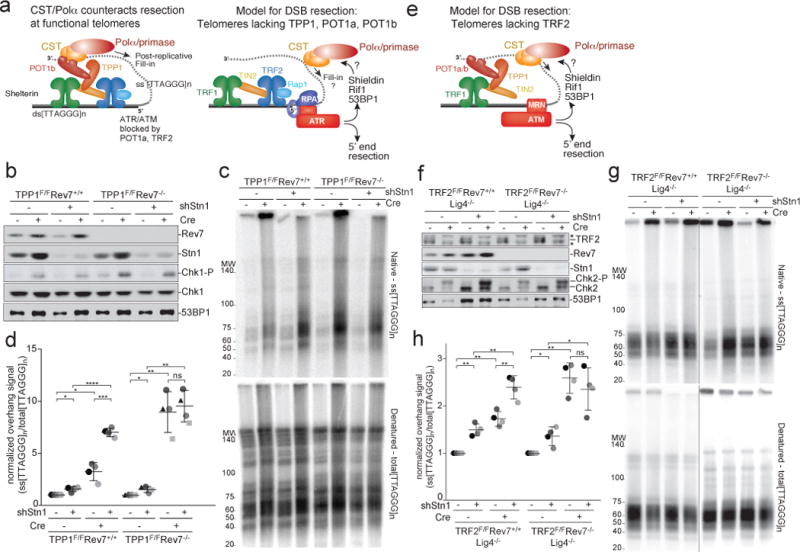

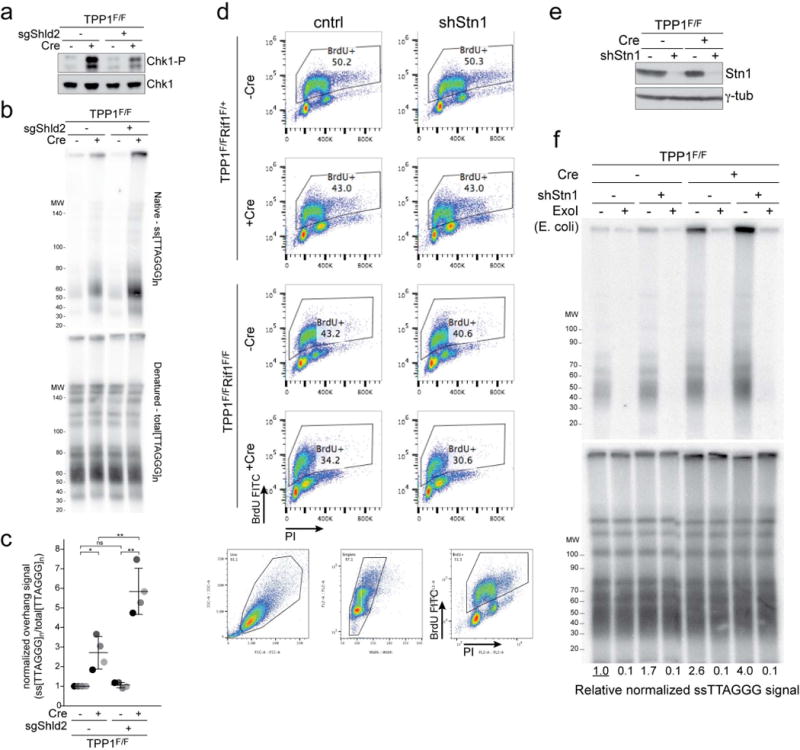

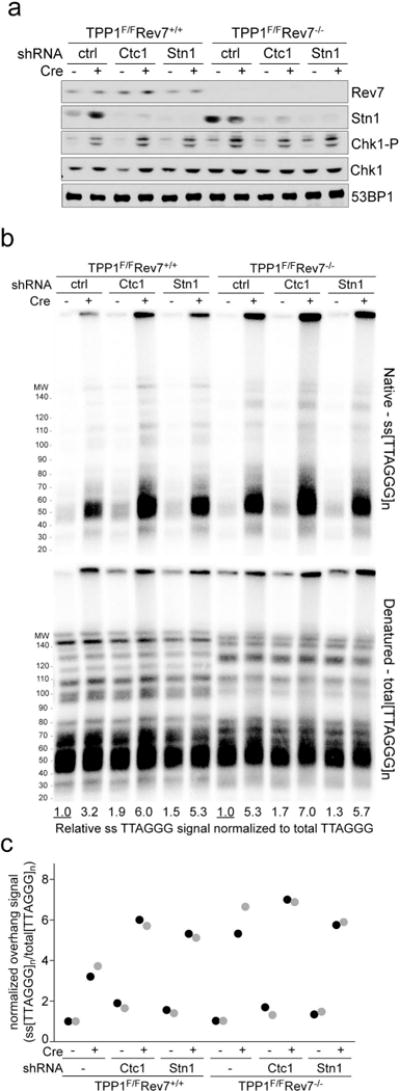

Figure 1. Shieldin and CST counteract resection at dysfunctioinal telomeres.

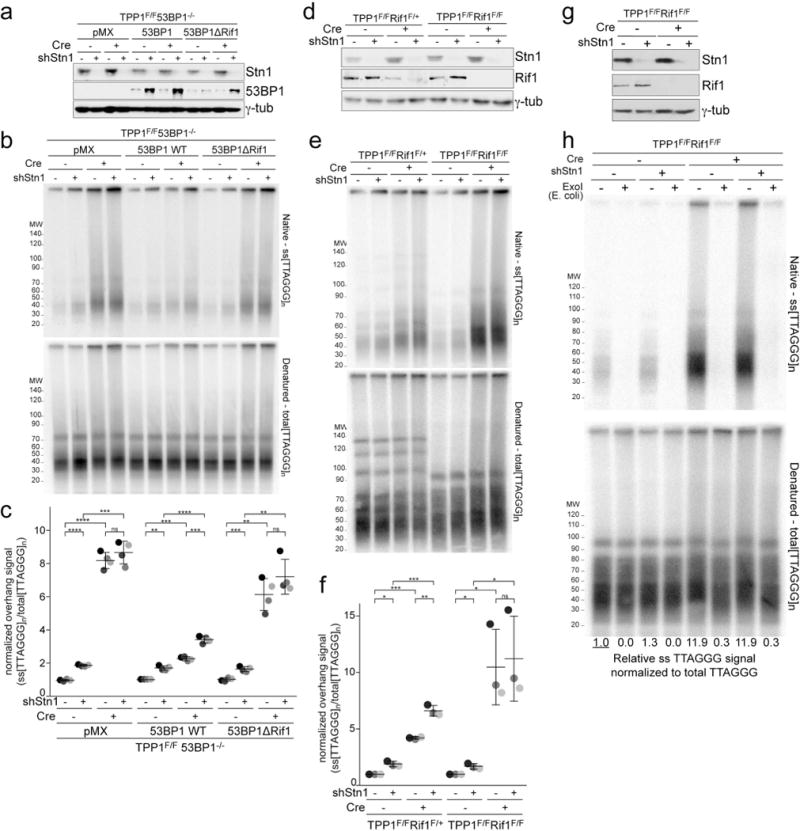

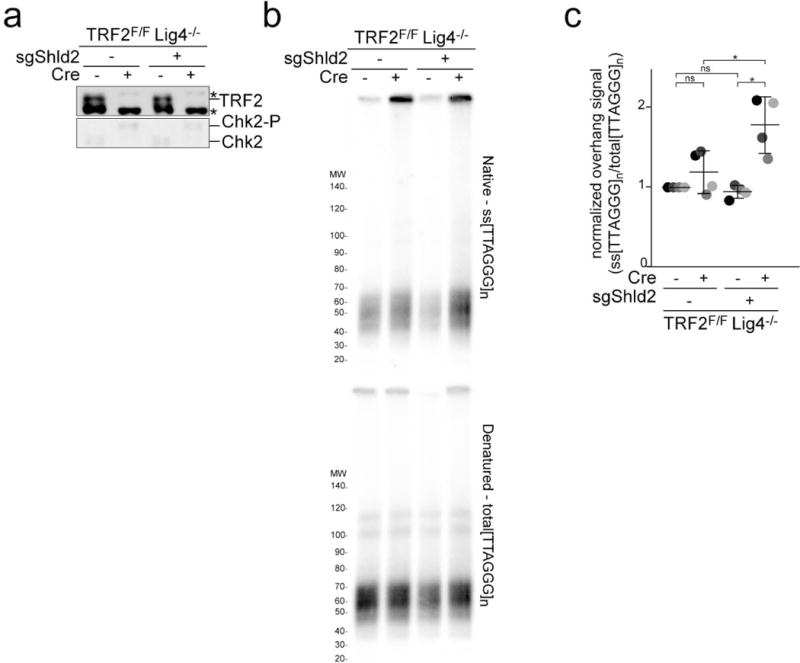

a, Left: Schematic showing POT1b-bound CST counteracting resection of telomere ends. Right: Depiction of telomeres lacking TPP1, POT1a, and POT1b as a proxy for DSB resection. Telomeres lacking TPP1 undergo ATR-dependent hyper-resection that is repressed by 53BP1. b, Immunoblots showing loss of Rev7 and Stn1 in the indicated TPP1F/F Rev7+/+ MEFs and TPP1F/F Rev7−/− (CRISPR) clones treated with Cre (96 h) and/or Stn1 shRNA as indicated. Chk1-P serves as a proxy for TPP1 deletion. c, Quantitative analysis of telomere end resection in the cells shown in (b) using in-gel hybridization to detect the 3′ overhang (top) followed by rehybridization to the denatured DNA in the same gel (bottom) to determine the ratio of ss to total TTAGGG signal. Representative of four experiments. d, Quantification of resection detected as in (c), determined from four independent experiments (different shades of gray) showing means and SDs. Three independent Rev7 KO clones were used (distinct symbols). e, Telomeres lacking TRF2 as a model for resection upon ATM activation. f, Immunoblots showing Cre-mediated deletion of TRF2 from TRF2F/F Lig4−/− cells, CRISPR deletion of Rev7, shRNA-mediated reduction of Stn1, and Chk2 phosphorylation. Asterisk: non-specific. g and h, Telomere end resection analysis on the cells in (f) as in (c) and (d). Means and SDs from four independent experiments using two clones of each genotype. Note that the order of the samples is different in (h) versus (f) and (g). All data panels in the figure are representative of four experiments. All means are indicated with center bars and SDs with error bars. All statistical analysis based on two-tailed Welch’s t-test. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001; ns, not significant.

To study the role of CST at sites of DNA damage, we used telomeres lacking shelterin protection, which are a model system for DSB resection8,15,18–20. Hyper-resection occurs upon Cre-mediated removal of TPP1 (and POT1a/b) from telomeres of TPP1F/F mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs). This hyper-resection is counteracted by 53BP1 and Rif120, which accumulate in response to ATR signaling at telomeres lacking POT1a (Fig. 1a). Like 53BP1, Shieldin limited hyper-resection at telomeres lacking TPP1: TPP1−/− cells lacking either Rev7 or Shld2 showed telomere hyper-resection (Fig. 1b-d, Extended Data Fig. 1a-c).

As CST is essential21,22, we used shRNAs to explore the role of CST in telomere hyper-resection. Depletion of Stn1 or Ctc1 increased the telomeric overhang signal in cells lacking TPP1 (Fig. 1b-d; Extended Data Fig. 1d; Extended Data Fig. 2) and tests with E. coli ExoI confirmed that the signal derived from a 3′ overhang (Extended Data Fig. 1e, f). Importantly, Stn1 or Ctc1 knockdown did not affect the resection at telomeres when TPP1 was deleted from Rev7-deficient cells (Fig. 1b-d; Extended Data Fig. 2). Furthermore, Stn1 knockdown had no effect on telomere hyper-resection when either 53BP1 or Rif1 were absent or when cells contained an allele of 53BP1 that does not recruit Rif123 (Extended Data Fig. 3). These data suggest that CST acts in a 53BP1-, Rif1-, and Shieldin-dependent manner to limit the formation of ssDNA at dysfunctional telomeres.

To determine whether CST also counteracted resection at sites of ATM signaling, we used conditional deletion of TRF2 (Fig. 1e). Telomeres lacking TRF2 undergo c-NHEJ-mediated fusion24–26. In DNA ligase IV (Lig4)-deficient cells where such telomere fusions are prevented26, telomeres lacking TRF2 undergo 5′ end resection that is exacerbated by loss of 53BP1 or Rif18,19 (Fig. 1e). Similarly, the 5′ end resection was increased by Rev7- or Shld2-deficiency (Fig. 1f-h; Extended Data Fig. 4). When Stn1 was depleted from cells lacking TRF2, resection at telomeres was significantly increased (Fig. 1f-h) and this effect was epistatic with Rev7 (Fig. 1f-h). Thus, CST counteracts resection in a Shieldin-dependent manner in the context of ATM signaling.

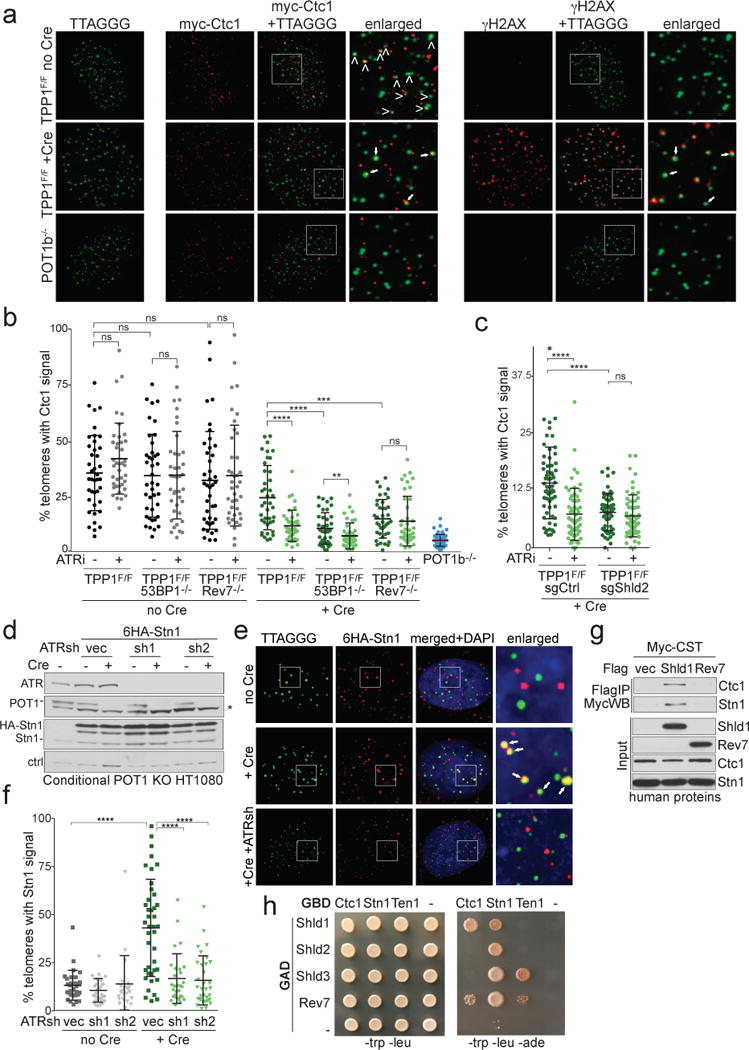

We next determined whether CST localized to damaged telomeres in a 53BP1- and Shieldin-dependent manner. Myc-tagged Ctc1 was detectable at telomeres with functional shelterin, whereas in POT1b-deficient cells – which show extended telomeric 3′ overhangs but no DNA damage signaling27 – Ctc1 localization at telomeres was minimal (Fig. 2a,b). When ATR was activated by deletion of TPP1 (Fig. 2a; right panel), Ctc1 was again detectable at telomeres (Fig. 2a, b), despite the absence of POT1b. Recruitment of Ctc1 to dysfunctional telomeres depended on ATR signaling, 53BP1, and Shieldin (Fig. 2b,c). Similarly, Cre-mediated deletion of the single human POT1 protein from conditional POT1 KO HT1080 cells28 led to telomeric accumulation of Stn1 that required ATR kinase (Fig. 2d-f). Thus, CST localizes to damaged telomeres in a Shieldin-dependent manner.

Figure 2. 53BP1- and Shieldin-dependent localization of CST to dysfunctional telomeres.

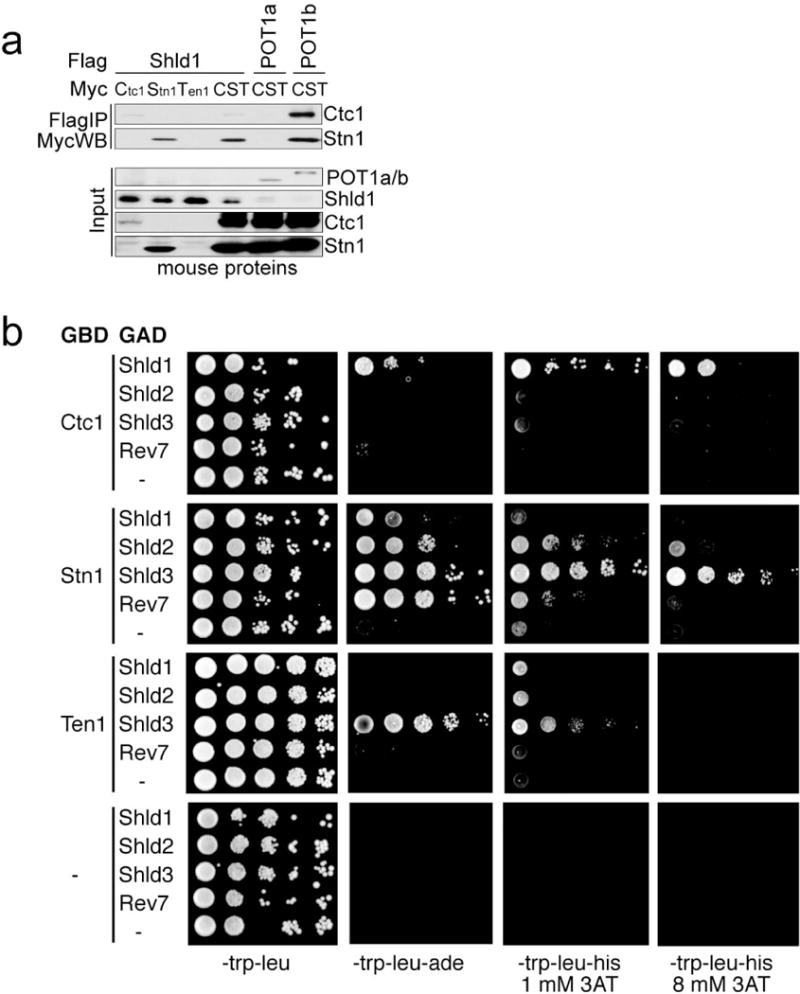

a, Left: Representative IF-FISH for 6myc-tagged Ctc1 (red) at telomeres (false-colored in green) in TPP1F/F MEFs before and after Cre (96 h). Arrowheads: Ctc1 at telomeres. POT1b−/− cells control for spurious telomere-Ctc1 co-localization. Right: The same nuclei showing γ-H2AX (red) at telomeres lacking TPP1. The γ-H2AX and Ctc1 signals are both false-colored in red. Arrows: telomeres with Ctc1 and γ-H2AX. b, Quantification of the % of telomeres co-localizing with Ctc1 detected as in (a). Each dot represents one nucleus from the indicated TPP1F/F cell lines with and without Cre and/or ATRi. Means and SDs from three independent experiments. c, As in (b) but using TPP1F/F cells treated with a Shld2 or a control sgRNA. Means and SDs as in (b). d, Immunoblots for POT1 deletion, ATR knockdown, and HA-Stn1 in conditional POT1 KO HT1080 cells. Asterisk: non-specific band. e, IF-FISH showing telomeric DNA co-localizing with Stn1 in cells as in (d) treated with Cre (96 h) and ATR shRNAs. f, Quantification of Stn1 localization at telomeres before and after POT1 deletion with or without ATR shRNAs as in (e). Means and SDs from three independent experiments. Each symbol represents one nucleus. g, Immunoprecipitation of human CST (each subunit Myc-tagged) with Flag-tagged human Shld1 or Rev7 co-expressed in 293T cells. h, Yeast 2-hybrid assay for interaction between CST and Shieldin subunits. All data panels in the figure are representative of three experiments. All means are indicated with center bars and SDs with error bars. All statistical analysis as in Fig. 1.

Co-IP experiments showed that Shieldin components could associate with CST (Fig. 2g; Extended Data Fig. 5a). In a yeast 2-hybrid assay, Ctc1 robustly interacted with Shld1, and Stn1 did so with Shld3 (Fig. 2h and Extended Data Fig. 5b). Weaker interactions were detectable between Ten1 and Shld3; Stn1 and Shld1, Shld2, and Rev7; and Ctc1 and Rev7. Thus, Shieldin binds CST through multiple direct interactions.

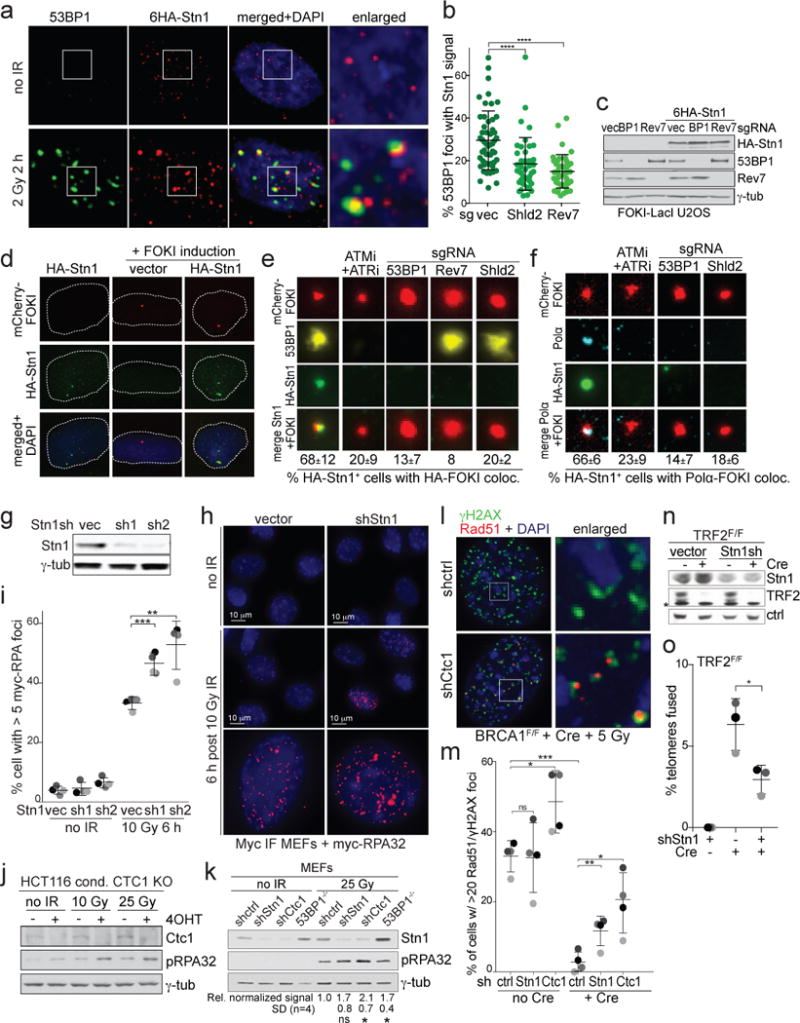

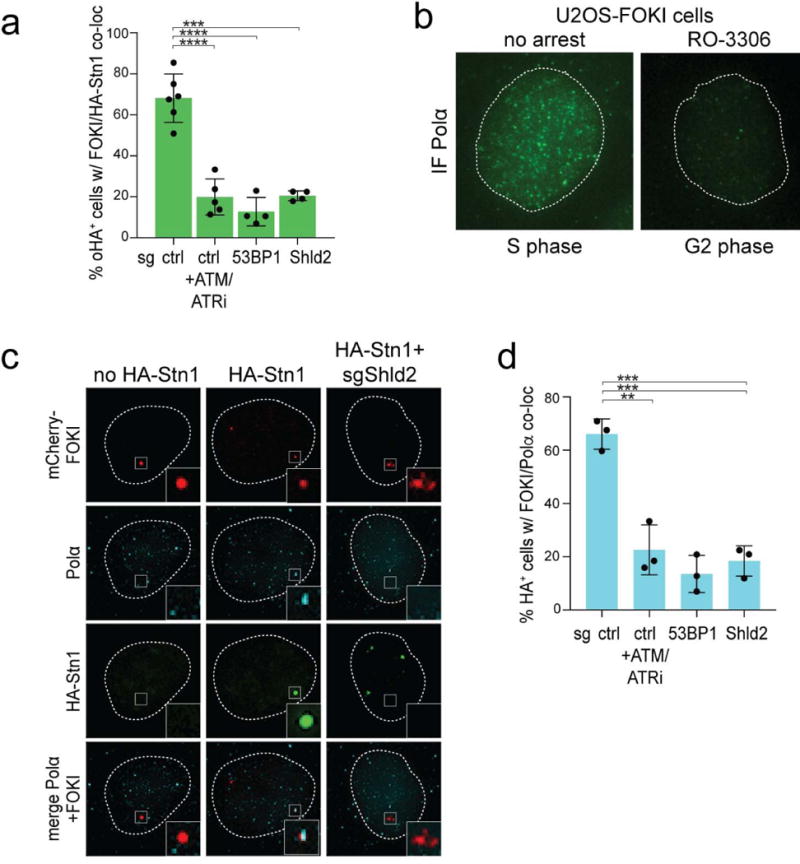

Ionizing radiation (IR)-induced DSBs in human cells showed Stn1 co-localizing with 53BP1 (Fig. 3a,b) in a manner dependent on Shieldin (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, Stn1 was detectable at FOKI-induced DSBs in U2OS cells and this localization required ATM/ATR signaling, 53BP1, and Shieldin (Fig. 3c-e; Ext. Data Fig. 6a), indicating that CST is recruited to sites of DNA damage by Shieldin.

Figure 3. CST localizes to DSBs and represses ssDNA formation.

a, IF for 53BP1 and HA-Stn1 in IR-treated HT1080 cells. b, Quantification of 53BP1/Stn1 co-localization as in (a) in cells with the indicated sgRNAs. Means and SDs from three independent experiments (>15 nuclei/experiment (symbols) for each experimental setting). c, Immunoblots for the indicated proteins in FOKI-LacI U2OS cells treated with the indicated sgRNAs. d, IF for mCherry-FOKI (red), and HA-Stn1 (green) in FOKI-LacI U2OS cells as in (c). e, Examples of HA-Stn1 co-localizing with FOKI foci in cells as in (d) treated with ATM and ATR inhibitors, or the indicated sgRNAs and quantification of Stn1/FOKI co-localization. Means and SDs from three independent experiments with >80 induced nuclei analyzed for each condition. f, As in (e) but monitoring Polα at DSBs in G2-arrested cells expressing HA-Stn1. g, Immunoblot for Stn1 knockdown in Myc-RPA32-expressing MEFs. h, IF for myc-RPA32 after 10 Gy IR (6 h). i, Quantification of cells with RPA foci as in (h) in >30 nuclei for each condition in three independent experiments (grey shading) with means and SDs. j and k, Immunoblots for IR-induced RPA phosphorylation (pS4/S8) after deletion of CTC1 from human cells (j) or after depletion of Stn1, Ctc1, or 53BP1 from MEFs (k). l, IF for Rad51/γH2AX co-localization at IR-induced DSBs in BRCA1-deficient cells treated with Ctc1 shRNA. m, Quantification of data as in (l). Means and SDs from four independent experiments (grey shading) (>60 nuclei/experiment). n, Immunoblot for Stn1 knockdown and TRF2 deletion from TRF2F/F RosaCreER MEFs. Asterisk: non-specific. o, Effect of Stn1 shRNA knockdown on telomere-telomere fusions. Means and SDs from three independent experiments (>6000 telomeres each). All IF and immunoblots shown are representative of three experiments. All means are indicated with center bars and SDs with error bars. All statistical analysis as in Fig. 1.

Since CST is associated with Polα/primase, we examined the localization of Polα ατ DSBs. Because Polα forms numerous S phase foci (Extended Data Fig. 6b), we examined cells arrested in G2 (Fig. 3f; Extended Data Fig. 6c). In cells expressing HA-Stn1, Polα co-localized with Stn1 at FOKI-induced DSBs (Fig. 3f; Extended Data Fig. 6c). Localization of Polα to DSBs depended on ATM/ATR signaling, 53BP1, and Shieldin (Fig. 3f; Extended Data Fig. 6d), demonstrating that Polα and CST require the same factors for their localization to DSBs.

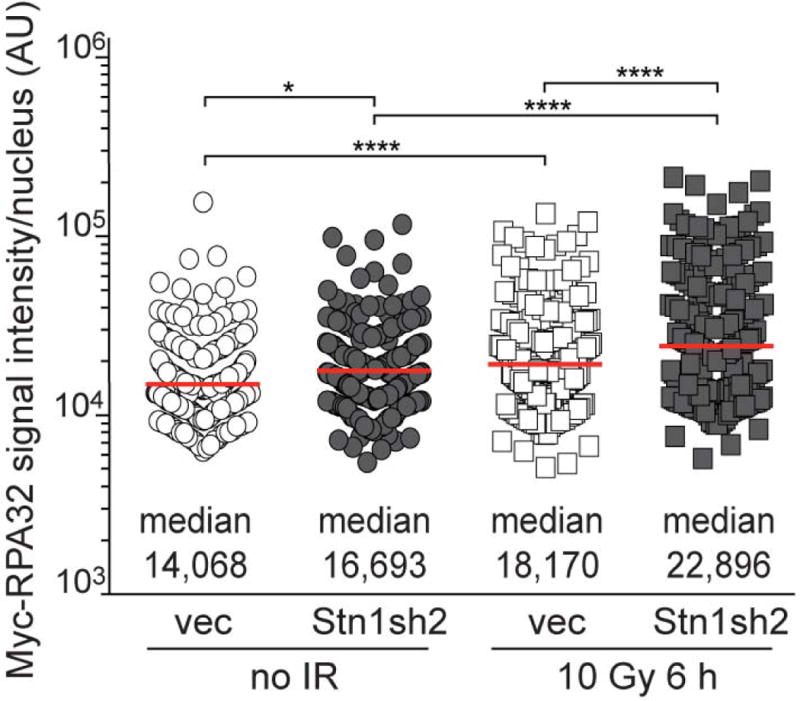

Depletion of Stn1 increased the percent of cells containing RPA foci after IR (Fig. 3g-i); increased the signal intensity of the RPA foci (Fig. 3h); and increased the overall RPA signal intensity per nucleus (Extended Data Fig. 7). Furthermore, deletion of Ctc1 from a human HCT116 cell line21 led to an increase in the phosphorylation of RPA upon irradiation (Fig. 3j) and CST depletion increased phosphorylation of RPA in irradiated MEFs (Fig. 3k). Depletion of CST also increased the IR-induced Rad51 foci in cells lacking BRCA1 (Fig. 3l,m), suggesting that HDR is restored. Conversely, depletion of CST diminished c-NHEJ based on an assay for the fusion of telomeres lacking TRF226 (Fig. 3n,o).

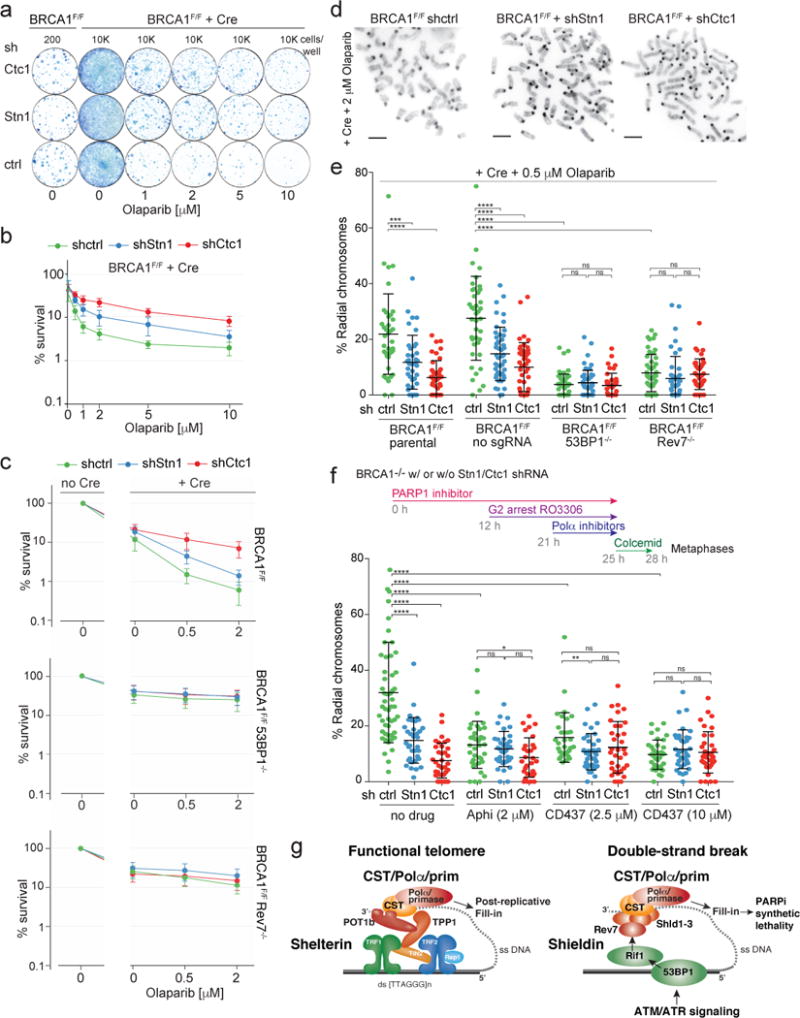

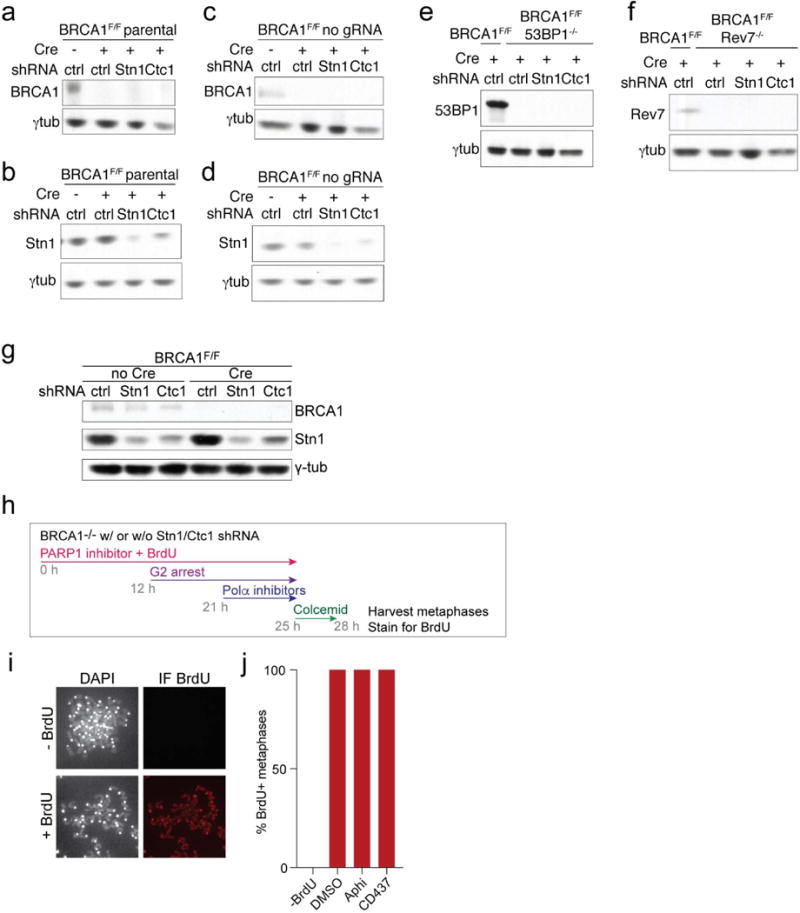

BRCA1-deficient cells become resistant to PARPi treatment when 53BP1, Rif1, or Shieldin are absent3–9. Similarly, Stn1 or Ctc1 depletion from BRCA1F/F MEFs reduced the lethality of PARPi in BRCA1-deficient cells (Fig. 4a, b; Extended Data Fig. 8a-f). In contrast, in BRCA1F/F subclones lacking 53BP1 or Rev7, depletion of Ctc1 or Stn1 did not affect PARPi resistance (Fig. 4c; Extended Data Fig. 8c-f). Furthermore, CST depletion reduced the PARPi-induced radial chromosomes in BRCA1-deficient cells (Fig. 4d,e) and this effect was epistatic with 53BP1 and Rev7 (Fig. 4e). These data are consistent with CST acting with 53BP1 and Shieldin to minimize formation of ssDNA at DSBs.

Figure 4. CST and Polα affect the outcome of PARPi in BRCA1-deficient cells.

a, Colonies detected in a PARPi survival assay using BRCA1F/F MEFs with or without Cre and shRNAs to CST. b, Graphical representation of data as in (a) from three independent experiments. c, Epistasis analysis of PARPi resistance induced by absence of 53BP1 or Rev7 and depletion of CST subunits. Means (symbol) and SEMs (error bars) from three independent experiments. d, PARPi-induced radial chromosomes in BRCA1-deficient cells. Scale bar: 1 μm. e, Means (center bar) and SDs (error bars) of % of misrejoined (radial) chromosomes in >10 metaphases per experimental setting for each of three independent experiments. Each dot represents one metaphase. f, Effect of Polα inhibition on radial formation in PARPi-treated BRCA1−/− cells using the experimental timeline shown. Means (center bar) and SDs (error bars) of % radial chromosomes in >10 metaphases per experimental setting for each of three independent experiments. Each dot represents one metaphase. g, Graphical representation of the similar mechanisms by which resection is counteracted at functional telomeres and at DSBs. Panels (a) and (d) are representative of three experiments. All statistical analysis as in Fig. 1.

To examine the consequences of Polα inhibition in PARPi-treated BRCA1-deficient cells without confounding S phase effects, cells were arrested in G2 before addition of Polα inhibitors (Fig. 4f). Cells that experienced Polα inhibition in G2 showed reduced formation of radial chromosomes (Fig. 4f; Extended Data Fig. 8g). BrdU incorporation experiments confirmed that the harvested mitotic cells had passed through S phase during PARPi treatment (Extended Data Fig. 8h-j). The effect of Polα inhibition with 10 μm CD437 was not exacerbated by depletion of CST (Fig. 4f). Collectively, these data are consistent with CST/Polα acting to limit formation of recombinogenic 3′ overhangs at DSBs in BRCA1-deficient cells (Fig. 4g).

Our data suggest a sophisticated mechanism by which 53BP1 and Shieldin with CST/Polα to fill-in resected DSBs. At telomeres, the POT1/TPP1 heterodimer recruits CST/Polα/primase to fill in part of the 3′ overhang formed after telomere end resection (Fig. 4g). We propose that at sites of DNA damage, Shieldin recruits CST/Polα/πριμασε for the similar purpose of filling in resected DSBs. In both settings, CST is tethered, allowing CST to engage ssDNA despite its modest affinity29 and enabling regulation of the fill-in reaction through recruitment. Recent data showed that 53BP1 represses mutagenic Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) possibly by preventing excessive resection30. Our findings on CST/Polα could explain this observation. At telomeres, partial fill-in by CST/Polα counteracts hyper-resection but leaves a 3′ overhang that can form a t-loop, a process similar to the initiation of HDR12,13. At DSBs, CST/Polα could similarly counteract hyper-resection, and thus SSA, while generating a 3′ overhang sufficient for HDR. In BRCA1-deficient cells, this fill-in reaction, together with the persistence of CST/Shieldin at the DSBs, could block HDR and result in lethal mis-repair.

Methods

Data reporting

See Reporting summary.

Cell culture and expression constructs

BRCA1F/F and TRF2F/FLig4−/− MEFs were derived from BRCA1F/F1, TRF2F/F2, and Lig4+/−3 mice by standard crosses. Mice were housed and cared for under Rockefeller University IACUC protocol 16865-H at the Rockefeller University’s Comparative Bioscience Center, which provides animal care according to NIH guidelines. MEFs were isolated from E12.5 embryos and immortalized with pBabeSV40 large T antigen (a gift from G. Hannon) at early passage (P2/3), as described previously2. Genotypes were determined by Transnetyx Inc. using real time PCR with allele-specific probes. TPP1F/F, TPP1F/F 53BP1−/− 4, TPP1F/F Rif1F/F or Rif1F/+5, and POTbSTOP/STOP6 MEFs were described previously. MEFs and U2OS cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Corning) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco), non-essential amino acids (Gibco), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco), 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma). 293T, Phoenix, and conditional POT1 knockout HT1080 clone c57 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum (BCS), non-essential amino acids, L-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin as above. For most Cre-mediated gene deletion experiments (see exceptions below), retroviral infections with pMMP Hit&Run Cre were repeated three times2. Time points of cell harvest indicate hours after the second Cre infection.

U2OS cells containing a LacO array and a tamoxifen- and Shield1-regulated mCherry-FOKI-LacI fusion were used as described8. Cells were harvested 4 h after induction of FOKI by addition of 0.1 μM Shield1 and 10 μg/ml 4-OHT. Human CTC1F/F HCT116 cells9 were cultured in McCoy’s 5A supplemented with 10% FCS, non-essential amino acids, L-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin as above. CTC1 gene deletion was induced with 0.5 μM 4-OHT for 5 h. Gene deletion was confirmed by Western blot using anti-Ctc1 antibody (MABE1103, Millipore).

Mouse Ctc1 tagged at the N-terminus with a 6xmyc tag was delivered by retroviral transduction using pLPC or pWZL retroviral vectors. Human Stn1 tagged at the N-terminus with a 6xHA tag was delivered using the pLPC vector. Myc-tagged RPA3210 and 53BP1wt and 53BP1ΔRif111 constructs were as described. Retroviral gene delivery was performed as described12.

RNA depletion with shRNAs in pLKO.1 (Open Biosystems) was performed using the following shRNA target sites: Stn1sh1: 5′-GATCCTGTGTTTCTAGCCTTT-3′ (TRCN0000180836, Sigma); Stn1sh2: 5′-GCTGTCATCAGCGTGAAAGAA-3′ (TRCN0000184261, Sigma); Ctc1sh: 5′-CGGCAGATCACAGCATGATAA-3′; ATRsh1: 5′-CTGTGGTTGTATCTGTTCAAT-3′ (TRCN0000039613, Sigma); ATRsh2: 5′-GATGAACACATGGGATATTTA-3′ (TRCN0000196538, Sigma). Lentiviral constructs were co-transfected with packaging vectors into 293T cells and cells infected with the viral supernatant were selected in puromycin as described12.

Drug treatments were as follows. ATR inhibition: 2.5 μM ETP-46464 (Sigma), 24 h; PARP1 inhibition: 0.1-10 μM Olaparib (Selleck Chemicals), 24 h; G2 arrest: 9 μM RO-3306 (Sigma), 12 h; Polymerase α inhibition: 2.5 or 10 μM CD437 (Sigma) or 2 μM Aphidicolin, 3 h. ATM/ATR inhibition: 10 μM KU55933 (Selleck Chemical) with ATRi as above for 4 h during induction of FOKI nuclease.

CRISPR-Cas9 gene disruption

Target sequences for CRISPR/Cas9 gene disruption were determined using ZiFit (http://zifit.partners.org). Clonal cell lines with disruption of mouse 53BP1 were generated using Cas9 vector (Addgene) and sgRNA (sg53BP1(2), 5′-GAGAATCTTCTATTATC-(PAM)-3′; sg53BP1(3), 5′-GCATCTGCAGATTAGGA-(PAM)-3′5) delivered by nucleofection (Amaxa Kit R, Lonza). Clones were screened by immunoblotting and bi-allelic gene disruption was verified by Sanger sequencing of Topo-cloned PCR products of the relevant locus (sequences available on request). Clonal cell lines with mouse Rev7 gene disruption were isolated similarly using the following sgRNAs: sgRev7(2), 5′-GTGTCCCCACCACAGTGG-(PAM)-3′; and sgRev7(3), 5′-GCCGGTTCAGGTGAGCCC-(PAM)-3′) (disrupted gene sequences available on request). Oligonucleotides were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and cloned into the AflII-digested gRNA expression vector (Addgene) by Gibson Assembly (New England Biolabs). For isolation of populations with CRISPR/Cas9 disruption of Shld2 (FAM35A), 293T cells were transfected with lentiCrispr-v2-Shld2-sgRNA (5′-ATCAGTCAGATCCCTGCGTT-(PAM)-3′) or the vector control. The lentiviral supernatant was used for infection of TPP1F/F or TRF2F/F Lig4−/− MEFs; infections were done six times at 6-12 h intervals. Infected cells were then selected in puromycin for 3-5 days before Cre infection.

FOKI-LacI U2OS cells were infected with the 6xHA tagged human Stn1 retrovirus and selected in puromycin. Subsequently, cells were subjected to lentiviral infection with lentiCrispr-v2 carrying sgRNA for human 53BP1, Shld2, or Rev7 and selected in blasticidin for 3 days. Target sequences for gene disruption are as follows: human 53BP1-sgRNA1 (5′-CAGAATCATCCTCTAGAACC-(PAM)-3′), 53BP1-sgRNA2 (5′-TTGATCTCACTTGTGATTCG-(PAM)-3′), Shld2-sgRNA1 (5′-TCTGGAGAACCAATAGATTC-(PAM)-3′), Shld2-sgRNA2 (5′-TTTGAGCTAAAAAAGCAACC-(PAM)-3′), Rev7-sgRNA1 (5′-CCTCAACTTTGGCCAAGGTA-(PAM)-3′), Rev7-sgRNA2 (5′-TATACTGATTCAGCTCCGGG-(PAM)-3′). For each gene the two sgRNAs were either used individually or together.

In-gel analysis of single-stranded telomeric DNA

Mouse telomeric overhang and telomeric restriction fragment patterns were analyzed 96-120 h after Cre treatment by in-gel hybridization with a γ-32P-ATP end-labeled [AACCCT]4 probe, as previously described2. Treatment with E. coli Exonuclease I prior to MboI digestion was used to verify the 3′ terminal position of the ssDNA as described previously5. ImageQuant software was used to quantify the single-stranded telomere overhang signals and the signal from total telomeric DNA in the same lane in the denatured gel. In each experiment, this ratio was set to 1 for lanes not treated with Cre or shRNA and the ratios for the treated samples are given relative to this control.

Flow Cytometry

FACS was performed as previously described13 with gating.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as described12 with the following Abs: 53BP1 (175933, Abcam; NB100-304, Novus Biological); ATR (sc-1887, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); BRCA1 (MAB22101, R+D systems); Chk1 (sc-8408, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); Chk1-S345-P (#2341S; Cell Signaling Technology); Chk2 (BD 611570, BD Biosciences); flag-tag (M2, Sigma; F1804, Sigma); γtubulin (GTU488, Sigma); MAD2L2/Rev7 (ab180579, Abcam); myc-tag (9B11, Cell Signaling Technology); OBFC1/Stn1 (E10-376450, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); Tagged Ten1 was not detectable by immunoblotting of transfected 293T cells.

For detection of RPA phosphorylation, conditional CTC1 HCT116 cells or MEFs were irradiated and harvested 3 h later. Cells were washed in PBS, and then collected by scraping in Laemmli sample buffer, boiling for 5 min, and shearing through a syringe. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 8-16% Tris-Glycine gradient gels (Invitrogen), and transferred to nitrocellulose overnight. Immunoblotting for pRPA followed standard protocols with blocking in 5% milk/TBST and the pRPA Ab (S4/S8; Bethyl) diluted 1:1000 in 1% milk/TBST.

Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation was carried out as described12. The following plasmids were used: pLPC-flag-POT1a and -POT1b6; pLPC-myc-mouse Ctc1, pLPC-myc-mouse Stn1, and pLPC-myc-mouse Ten112; pLPC-myc-human Ctc1, pLPC-myc-human Stn1, pLPC-myc-human Ten1, pCDNA5-flag-human Shld1 (C20orf196), and pLPC-myc-hRev7, pLPC-flag-mouse Shld1 (ortholog of C20orf196). Human Rev7, Shld1, Ctc1, Stn1, and Ten1 ORFs were generated by PCR and mouse Shld1 was generated by RT-PCR. Co-transfection of Shld1 and Rev7 with CST in 293T cells was performed using calcium phosphate co-precipitation. Lysates were prepared in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% NP-40, Complete protease inhibitor mix (Roche), and PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor mix (Roche) and 50 U Benzonase.

Yeast 2-hybrid assays

For yeast 2-hybrid analysis, full-length versions of human CST and Shieldin components were cloned into the NdeI site of the pGBKT7 and pGADT7 vectors (Clontech). Plasmids in the indicated pair-wise combinations were co-transformed into budding yeast strain PJ69-4A (MATa trp1-901 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-200 gal4 gal80 LYS2::GAL1-HIS3 GAL2-ADE2 met2::GAL7-lacZ) and selected on synthetic complete drop-out media lacking tryptophan and leucine. Protein interactions were tested by plating on the same medium but also lacking adenine.

IF and IF-FISH

Previously published procedures were followed for IF and IF-FISH12. IF for myc-tagged RPA32 or Ctc1 (mouse monoclonal, 9B11 or rabbit monoclonal, 71D10, Cell Signaling Technology), HA-tagged Stn1 (3724, Cell Signaling Technology), endogenous Polα (sc-137021, Santa Cruz), and 53BP1 (612522, BD Biosciences) was carried out using the cytoskeleton extraction protocol14. Intensity measurements of RPA32-myc IF were performed in FIJI as follows: nuclei were identified using thresholding, segmented, and identified as regions of interest. The average image background was then subtracted from the image, and the total raw pixel intensity within each area of interest in the channel of interest was calculated. Rad51 (70-001, Bioacademia), and γH2AX (05636, Millipore) were detected in cells fixed in 3% PFA, and foci showing co-localization of Rad51 with γH2AX were quantified. IF imaging was performed on a Zeiss Axioplan II microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu C4742-95 camera using Volocity software or on a DeltaVision (Applied Precision) equipped with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (DV Elite CMOS Camera), a PlanApo 60× 1.42 NA objective or 100× 1.40 NA objective (Olympus America, Inc.), and SoftWoRx software.

Telomere fusion assays

SV40LT-immortalized TRF2F/F RosaCre cells were infected with Stn1 shRNA (or the empty vector) and 24 h later Cre was induced for 24 h with 4-OHT. Cells were harvested, counted (to rule out a proliferation defect), and processed for telomeric FISH on metaphases 72 h after Cre induction. This early time point was selected to avoid any effect of the Stn1 shRNA on proliferation since diminished proliferation reduces fusion frequencies. Telomere fusions were scored as described previously2.

Survival assays and chromosome analysis

PARPi survival assays and analysis of misrejoined chromosomes were carried out as described15, except that for analysis of radial chromosomes, MEFs were incubated with 0.5 μM Olaparib (AZD2281) for 24 h before harvest. For the survival assays, MEFs were seeded in 6-well plates in duplicate at 10, 50, 100, 500, 1,000, 5,000, or 10,000 cells per well. After 24 h, cells were treated with Olaparib at the indicated concentrations for 24 h. Cells were then provided with media without Olaparib and incubated for one week with a media change at day 4. Colonies were fixed and stained with 50% methanol, 2% methylene blue, rinsed with water, and dried before counting. The survival percentage at each PARPi concentration compared to untreated cells was calculated using wells with 10-100 colonies. Two technical replicates at two cell concentrations were scored for each condition in three independent experiments.

All data generated/analyzed in this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Shieldin and CST counteract telomere hyper-resection.

a-c, Effect of Shld2 on hyper-resection at telomeres lacking TPP1. a, Immunoblot for Chk1-P, an indicator of TPP1 deletion, in TPP1F/F MEFs with and without bulk population treatment with an sgRNA to Shld2 and/or Cre (representative of three experiments). b, Quantitative analysis of telomere end resection as in Fig. 1c using the cells shown in (a). c, Quantification of the extent of resection detected in (c) as in Fig. 1d. Means (center bars) and SDs (error bars) from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis as in Fig. 1. d, FACS profiles of the indicated cells incubated with BrdU to measure (lack of) S phase effects of the Stn1 shRNA. Gating strategy for live cells and singlets is shown below the FACS profiles. Representative of two experiments. e, f, Experiments to verify that the ssDNA signal derives from a 3′ overhang. e, Immunoblot for Stn1 and γ-tubulin in TPP1F/F (Rif1F/+) cells treated with Stn1 shRNA and/or Cre. Representative of two experiments. f, Quantitative assay for telomeric overhangs as in Fig. 1c. Plugs in the ExoI lanes were treated with the 3′ exonuclease from E. coli. Representative of two experiments.

Extended Data Figure 2. Hyper-resection at telomeres lacking TPP1 is counteracted by CST and Shieldin.

a, Immunoblots showing absence of Rev7 and reduction of Stn1 expression in the indicated TPP1F/F and TPP1F/F Rev7−/− MEFs treated with either Ctc1 or Stn1 shRNA. Diminished Stn1 expression is used as a proxy for the efficacy of the Ctc1 shRNA. Representative of two experiments. b, Quantitative analysis of telomeric overhangs as in Fig. 1c. Representative of two experiments. c, Quantification of the effect of Ctc1 and Stn1 on resection at telomeres lacking TPP1 as in Fig. 1d. Data is obtained from two independent Rev7-proficient and two independent Rev7-deficient clones (light and dark shading).

Extended Data Figure 3. No effect of CST depletion on telomere hyper-resection when 53BP1 or Rif1 are absent.

a, SV40LT-immortalized TPP1F/F 53BP1−/− cells were complemented with wt 53BP1 or a mutant 53BP1 lacking the ability to interact with Rif1, treated with a Stn1 shRNA as indicated, and analyzed by immunoblotting for 53BP1 and Stn1. Representative of four experiments. b, Quantitative analysis of telomeric overhangs as in Fig. 1c. c, Quantification of the resection at telomeres lacking TPP1 in four independent experiments performed as in Fig. 1d. d, Immunoblots showing loss of Rif1 and Stn1 in the indicated TPP1F/F Rif1F/+ and TPP1F/F Rif1F/F MEFs treated with Cre (96 h) as indicated and with or without Stn1 shRNA. Note diminished Rif1 levels after Cre due to heterozygosity in the TPP1F/F Rif1F/+ cells. e, Quantitative analysis of telomeric overhangs as in Fig. 1c. f, Quantification of the extent of resection detected as in (c), determined from three independent experiments (indicated by different shades of gray) showing means (center bars) and SDs (error bars). Each experiment involved all indicated samples analyzed in parallel. g, h, Experiments to verify that the ssDNA signal derives from a 3′ overhang. g, Immunoblot for Stn1 and γ-tubulin in TPP1F/F Rif1F/F cells treated with Stn1 shRNA and/or Cre. Representative of two experiments. h, Quantitative assay for telomeric overhangs as in Fig. 1c. Plugs in the ExoI lanes were treated with the 3′ exonuclease from E. coli. Representative of two experiments. All statistical analysis as in Fig. 1.

Extended Data Figure 4. Shld2 counteracts resection at telomeres lacking TRF2.

a, Immunoblots for TRF2 deletion and Chk2 phosphorylation in TRF2F/F Lig4−/− MEFs with and without bulk population treatment with an sgRNA to Shld2 and/or Cre. Asterisk: non-specific band. Representative of three experiments. b, Quantitative analysis of telomere end resection as in Fig. 1c using the cells shown in (a). c, Quantification of the extent of resection detected in (b) as in Fig. 1d. Means (center bars) and SDs (error bars) from three independent experiments. All statistical analysis as in Fig. 1.

Extended Data Figure 5. CST interacts with Shieldin.

a, Immunoprecipitation of individual mouse CST subunits or the three subunit complex (each subunit bearing a Myc-tag) with Flag-tagged mouse Shld1 co-expressed in 293T cells. Flag-tagged POT1b and POT1a serve as positive and negative controls for CST binding, respectively. Representative of two experiments. b, Two-hybrid analysis of CST-Shieldin interaction. Yeast cultures were grown overnight in synthetic complete medium lacking tryptophan and leucine to a density of 5*107 cells/ml. Serial 10-fold dilutions were generated and 4 ul of each dilution was spotted on synthetic complete media lacking the nutrients tryptophan, leucine, adenine, histidine and containing 3-aminotriazole (3-AT) as indicated. Plates were then incubated for 5 days at 30°C before imaging. Representative of three experiments.

Extended Data Figure 6. Localization of CST and Polα to DSBs.

a, Quantification of HA-Stn1 localization to FOKI-induced DSBs as in Fig. 3e. Means (center bars) and SDs (error bars) from 4-6 independent experiments (>80 induced nuclei for each condition in each experiment) are shown. b, IF for endogenous Polα in FOKI-LacI U2OS cells in S phase and after RO3306 treatment (G2). Dotted line: outline of the nucleus. Representative of two experiments. c, Examples of HA-Stn1 and Polα localization at FOKI-induced DSBs in G2-arrested FOKI-LacI U2OS cells (as in Fig. 3f). Representative of three experiments. d, Quantification of co-localization of Polα with FOKI-induced DSBs (as in Fig. 3f). Means (center bars) and SDs (error bars) from three independent experiments (>80 induced nuclei for each condition in each experiment) are shown. All statistical analysis as in Fig. 1.

Extended Data Figure 7. Effect of Stn1 knockdown on the intensity of IR-induced RPA foci.

Quantification of myc-RPA32 intensity per nucleus in the experiments shown in Fig. 3g-h. Medians (center bars and numbers below) obtained from four independent experiments with >20 nuclei for each experimental condition in each experiment. Each symbol represents one nucleus. Statistical analysis as in Fig. 1.

Extended Data Figure 8. Effect of CST and Polα on PARPi treatment of BRCA1-deficient cells.

a-f, Immunoblots on the MEFs used in Fig. 4a-e to verify the absence of deleted proteins and efficacy of the shRNAs. Reduction in Stn1 expression is used as a proxy for the efficacy of the Ctc1 shRNA since no antibody to mouse Ctc1 is available. Each immunoblot is representative of three experiments. g, Immunoblots for BRCA1 and Stn1 in the cells used in Fig. 4f. Representative of two experiments. h-j, Control experiment to assess that cells analyzed in Fig. 4f progressed through S phase during PARPi treatment. h, Experimental timeline as in Fig. 4f but with inclusion of BrdU in the media during PARPi treatment. i, Example of the assay for the presence of BrdU (IF) in metaphases harvested after the experimental timeline as in (h). j, Quantification of the BrdU incorporation into metaphase chromosomes as in (i) (one experiment with 10 metaphases per condition).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Devon White for expert mouse husbandry. Nazario Bosco, Roos Karssemeijer, Leonid Timashev, and Ylli Doksani are thanked for help with CRISPR gene knockouts, image analysis, and generating MEFs. Roger Greenberg and Carolyn Price are thanked for providing cell lines. Rockefeller University BioImaging Center provided assistance. This work was supported by grants from the NCI (R35CA210036), ACS, and BCRF to TdL, a grant from the CIHR (FDN143343) to DD, and the Banting Postdoctoral fellowship to MZ.

Footnotes

Competing interests

DD is a founder of, owns equity in, and receives funding from Repare Therapeutics.

Author contributions

MZ initiated this work in the de Lange lab. TK and FL performed resection assays. ZM and HT performed CST and Polα localization assays, pRPA assays. ZM performed PARPi and Rad51 assays. YG and TK analyzed RPA foci. AB performed yeast 2-hybrid assays. KT and HT performed co-IP analysis. KT and TdL performed telomere fusion assays. DD provided information, reagents, and advice. TdL conceived the study and wrote the paper with input from all co-authors.

Literature cited

- 1.Zimmermann M, de Lange T. 53BP1: pro choice in DNA repair. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panier S, Boulton SJ. Double-strand break repair: 53BP1 comes into focus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:7–18. doi: 10.1038/nrm3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouwman P, Aly A, Escandell JM, Pieterse M, Bartkova J, van der Gulden H, Hiddingh S, Thanasoula M, Kulkarni A, Yang Q, Haffty BG, Tommiska J, Blomqvist C, Drapkin R, Adams DJ, Nevanlinna H, Bartek J, Tarsounas M, Ganesan S, Jonkers J. 53BP1 loss rescues BRCA1 deficiency and is associated with triple-negative and BRCA-mutated breast cancers. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:688–695. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu G, Chapman JR, Brandsma I, Yuan J, Mistrik M, Bouwman P, Bartkova J, Gogola E, Warmerdam D, Barazas M, Jaspers JE, Watanabe K, Pieterse M, Kersbergen A, Sol W, Celie PH, Schouten PC, van den Broek B, Salman A, Nieuwland M, de Rink I, de Ronde J, Jalink K, Boulton SJ, Chen J, van Gent DC, Bartek J, Jonkers J, Borst P, Rottenberg S. REV7 counteracts DNA double-strand break resection and affects PARP inhibition. Nature. 2015;521:541–544. doi: 10.1038/nature14328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bunting SF, Callen E, Wong N, Chen HT, Polato F, Gunn A, Bothmer A, Feldhahn N, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Cao L, Xu X, Deng CX, Finkel T, Nussenzweig M, Stark JM, Nussenzweig A. 53BP1 inhibits homologous recombination in Brca1-deficient cells by blocking resection of DNA breaks. Cell. 2010;141:243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman JR, Barral P, Vannier JB, Borel V, Steger M, Tomas-Loba A, Sartori AA, Adams IR, Batista FD, Boulton SJ. RIF1 is essential for 53BP1-dependent nonhomologous end joining and suppression of DNA double-strand break resection. Mol Cell. 2013;49:858–871. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boersma V, Moatti N, Segura-Bayona S, Peuscher MH, van der Torre J, Wevers BA, Orthwein A, Durocher D, Jacobs JJ. MAD2L2 controls DNA repair at telomeres and DNA breaks by inhibiting 5′ end resection. Nature. 2015;521:537–540. doi: 10.1038/nature14216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmermann M, Lottersberger F, Buonomo SB, Sfeir A, de Lange T. 53BP1 regulates DSB repair using Rif1 to control 5′ end resection. Science. 2013;339:700–704. doi: 10.1126/science.1231573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noordermeer SM, Adam S, Setiaputra D, Barazas M, Pettitt SJ, Ling AK, Olivieri M, Álvarez-Quilón A, Moatti N, Zimmermann M, Annunziato S, Krastev DB, Song F, Brandsma I, Frankum J, Brough R, Sherker A, Landry S, Szilard RK, Munro MM, McEwan A, Rugy TGD, Lin Z-Y, Hart T, Moffat J, Gingras A-C, Martin A, Attikum HV, Jonkers J, Lord CJ, Rottenberg S, Durocher D. The Shieldin complex mediates 53BP1-dependent DNA repair. Nature. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0340-7. in Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price CM, Boltz KA, Chaiken MF, Stewart JA, Beilstein MA, Shippen DE. Evolution of CST function in telomere maintenance. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3157–3165. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casteel DE, Zhuang S, Zeng Y, Perrino FW, Boss GR, Goulian M, Pilz RB. A DNA polymerase-{alpha}{middle dot}primase cofactor with homology to replication protein A-32 regulates DNA replication in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5807–5818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807593200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffith JD, Comeau L, Rosenfield S, Stansel RM, Bianchi A, Moss H, de Lange T. Mammalian telomeres end in a large duplex loop. Cell. 1999;97:503–14. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doksani Y, Wu JY, de Lange T, Zhuang X. Super-resolution fluorescence imaging of telomeres reveals TRF2-dependent T-loop formation. Cell. 2013;155:345–356. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palm W, de Lange T. How shelterin protects mammalian telomeres. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:301–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazzerini-Denchi E, Sfeir A. Stop pulling my strings - what telomeres taught us about the DNA damage response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:364–378. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu P, Takai H, de Lange T. Telomeric 3′ Overhangs Derive from Resection by Exo1 and Apollo and Fill-In by POT1b-Associated CST. Cell. 2012;150:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goulian M, Heard CJ, Grimm SL. Purification and properties of an accessory protein for DNA polymerase alpha/primase. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13221–13230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sfeir A, de Lange T. Removal of shelterin reveals the telomere end-protection problem. Science. 2012;336:593–597. doi: 10.1126/science.1218498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lottersberger F, Bothmer A, Robbiani DF, Nussenzweig MC, de Lange T. Role of 53BP1 oligomerization in regulating double-strand break repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:2146–2151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222617110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kibe T, Zimmermann M, de Lange T. TPP1 Blocks an ATR-Mediated Resection Mechanism at Telomeres. Mol Cell. 2016;61:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng X, Hsu SJ, Kasbek C, Chaiken M, Price CM. CTC1-mediated C-strand fill-in is an essential step in telomere length maintenance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:4281–4293. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu P, Min JN, Wang Y, Huang C, Peng T, Chai W, Chang S. CTC1 deletion results in defective telomere replication, leading to catastrophic telomere loss and stem cell exhaustion. EMBO J. 2012;31:2309–2321. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lottersberger F, Karssemeijer RA, Dimitrova N, de Lange T. 53BP1 and the LINC Complex Promote Microtubule-Dependent DSB Mobility and DNA Repair. Cell. 2015;163:880–893. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Steensel B, Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. TRF2 protects human telomeres from end-to-end fusions. Cell. 1998;92:401–413. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlseder J, Broccoli D, Dai Y, Hardy S, de Lange T. p53- and ATM-dependent apoptosis induced by telomeres lacking TRF2. Science. 1999;283:1321–1325. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5406.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Celli GB, de Lange T. DNA processing is not required for ATM-mediated telomere damage response after TRF2 deletion. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:712–718. doi: 10.1038/ncb1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hockemeyer D, Daniels JP, Takai H, de Lange T. Recent expansion of the telomeric complex in rodents: Two distinct POT1 proteins protect mouse telomeres. Cell. 2006;126:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takai H, Jenkinson E, Kabir S, Babul-Hirji R, Najm-Tehrani N, Chitayat DA, Crow YJ, de Lange T. A POT1 mutation implicates defective telomere end fill-in and telomere truncations in Coats plus. Genes Dev. 2016;30:812–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.276873.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hom RA, Wuttke DS. Human CST Prefers G-Rich but Not Necessarily Telomeric Sequences. Biochemistry. 2017 doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ochs F, Somyajit K, Altmeyer M, Rask MB, Lukas J, Lukas C. 53BP1 fosters fidelity of homology-directed DNA repair. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:714–721. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1.Xu X, Weaver Z, Linke SP, Li C, Gotay J, Wang XW, Harris CC, Ried T, Deng CX. Centrosome amplification and a defective G2-M cell cycle checkpoint induce genetic instability in BRCA1 exon 11 isoform-deficient cells. Mol Cell. 1999;3:389–95. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Celli GB, de Lange T. DNA processing is not required for ATM-mediated telomere damage response after TRF2 deletion. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:712–718. doi: 10.1038/ncb1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank KM, Sekiguchi JM, Seidl KJ, Swat W, Rathbun GA, Cheng HL, Davidson L, Kangaloo L, Alt FW. Late embryonic lethality and impaired V(D)J recombination in mice lacking DNA ligase IV. Nature. 1998;396:173–7. doi: 10.1038/24172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kibe T, Osawa GA, Keegan CE, de Lange T. Telomere Protection by TPP1 Is Mediated by POT1a and POT1b. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1059–1066. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01498-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kibe T, Zimmermann M, de Lange T. TPP1 Blocks an ATR-Mediated Resection Mechanism at Telomeres. Mol Cell. 2016;61:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hockemeyer D, Daniels JP, Takai H, de Lange T. Recent expansion of the telomeric complex in rodents: Two distinct POT1 proteins protect mouse telomeres. Cell. 2006;126:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takai H, Jenkinson E, Kabir S, Babul-Hirji R, Najm-Tehrani N, Chitayat DA, Crow YJ, de Lange T. A POT1 mutation implicates defective telomere end fill-in and telomere truncations in Coats plus. Genes Dev. 2016;30:812–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.276873.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang J, Cho NW, Cui G, Manion EM, Shanbhag NM, Botuyan MV, Mer G, Greenberg RA. Acetylation limits 53BP1 association with damaged chromatin to promote homologous recombination. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng X, Hsu SJ, Kasbek C, Chaiken M, Price CM. CTC1-mediated C-strand fill-in is an essential step in telomere length maintenance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:4281–4293. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gong Y, Handa N, Kowalczykowski SC, de Lange T. PHF11 promotes DSB resection, ATR signaling, and HR. Genes Dev. 2017;31:46–58. doi: 10.1101/gad.291807.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lottersberger F, Karssemeijer RA, Dimitrova N, de Lange T. 53BP1 and the LINC Complex Promote Microtubule-Dependent DSB Mobility and DNA Repair. Cell. 2015;163:880–893. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu P, Takai H, de Lange T. Telomeric 3′ Overhangs Derive from Resection by Exo1 and Apollo and Fill-In by POT1b-Associated CST. Cell. 2012;150:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takai H, Wang RC, Takai KK, Yang H, de Lange T. Tel2 regulates the stability of PI3K-related protein kinases. Cell. 2007;131:1248–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirzoeva OK, Petrini JH. DNA damage-dependent nuclear dynamics of the Mre11 complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:281–288. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.1.281-288.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lottersberger F, Bothmer A, Robbiani DF, Nussenzweig MC, de Lange T. Role of 53BP1 oligomerization in regulating double-strand break repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:2146–2151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222617110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.