Abstract

Many biological processes involve solute-protein interactions and solute-solute competition for protein binding. One method that has been developed to examine these interactions is zonal elution affinity chromatography. This review discusses the theory and principles of zonal elution affinity chromatography, along with its general applications. Examples of applications that are examined include the use of this method to estimate the relative extent of solute-protein binding, to examine solute-solute competition and displacement from proteins, and to measure the strength of these interactions. It is also shown how zonal elution affinity chromatography can be used in solvent and temperature studies and to characterize the binding sites for solutes on proteins. In addition, several alternative applications of zonal elution affinity chromatography are discussed, which include the analysis of binding by a solute with a soluble binding agent and studies of allosteric effects. Other recent applications that are considered are the combined use of immunoextraction and zonal elution for drug-protein binding studies, and binding studies that are based on immobilized receptors or small targets.

Keywords: biological interactions, transport proteins, receptors, binding, allosteric effects, immunoextraction

1. Introduction

Zonal elution is the most prevalent form of affinity chromatography that is used for the analysis of solute-protein interactions and solute-solute competition for binding sites on proteins [1–5]. In this method, a small amount of an analyte or solute (A) is injected into a chromatographic system that contains an affinity column with an immobilized biological ligand or binding agent (L). This injection is often made in the presence of a mobile phase that contains a known concentration of a competing agent or interacting agent (I). The time or mobile phase volume that is required to elute the solute from the column is then monitored and used to provide information on the interactions between the injected solute, the agent in the mobile phase, and/or the immobilized binding agent [6]. This review will examine the theory, principles and applications of zonal elution affinity chromatography method in the study of solute-protein binding and solute-solute competition for proteins.

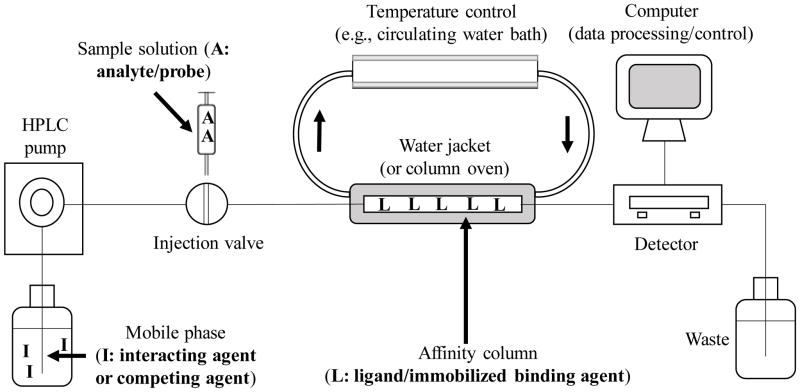

A typical HPLC system for performing a zonal elution experiment is shown in Figure 1 [6]. This particular system design includes an online detector; however, a fraction collector and an offline detector can also be employed, particularly when the experiment involves a low-performance affinity column [4,6,7]. Temperature control is ideally needed for this type of system to obtain optimum precision and accuracy [6]. Linear elution conditions are also often required, in which the amount of the injected solute is negligible compared to the amount of the binding agent in the column [2,6,8]. However, nonlinear elution conditions can be employed in some situations for zonal elution experiments [9–11].

Figure 1.

A typical HPLC system for use in zonal elution affinity chromatography and studies of solute-protein binding or solute-solute competition for proteins.

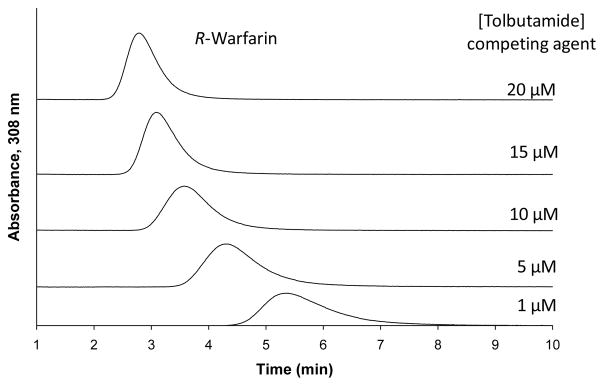

The use of zonal elution affinity chromatography for binding studies was first described in 1974 by Dunn and Chaiken in a work based on low-performance columns [12]. Starting from this pioneering work, the same format has been used in many other studies using both high- and low-performance systems to examine solute-protein binding and solute-solute competition for sites on proteins [11,13–33]. An example of the use of an HPLC system is shown in Figure 2 [31]. In this example, R-warfarin was injected as a probe into a column that contained immobilized human serum albumin (HSA) as the binding agent. The mobile phases in this example had tolbutamide as a potential competing agent for R-warfarin at a mutual binding site on HSA. As the concentration of tolbutamide was increased in the mobile phase, there was a decrease in the observed retention time for R-warfarin, indicating that either direct competition or a negative allosteric interaction was present between tolbutamide and R-warfarin during their binding to HSA [31]. A similar format has been used to examine the retention and competition of numerous other solutes on affinity columns [6].

Figure 2.

Typical chromatograms obtained in zonal elution studies using injections of R-warfarin as a site-selective probe for HSA and mobile phases that contained various concentrations of tolbutamide as a competing agent or interacting agent. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [31].

There are several advantages to using zonal elution and affinity chromatography for the analysis of solute-protein binding and solute-solute competition. First, only a small amount of solute is needed per injection and the same preparation of an immobilized binding agent can often be used for many experiments [4,6]. In addition, it is possible in some situations (e.g., with chiral compounds) to examine the binding by more than one solute per run, as long as sufficient resolution is present to differentiate between the corresponding peaks for these solutes [4]. There are several other advantages when using this type of method as part of an HPLC system, including the good precision and speed of HPLC as well as the variety of detectors that can be used to monitor solute elution [32].

Zonal elution has several additional advantages when compared to frontal analysis, which is the other major form of affinity chromatography that is used for binding studies [6]. These advantages include the ability of zonal elution to work with a smaller amount of a solute than frontal analysis and the longer time that is often needed for frontal analysis experiments. As will be shown in Section 7, zonal elution can also be used in work with binding agents that may contain multiple sites for a solute and can allow binding strengths to be measured at individual sites [16,26]. The main disadvantages of zonal elution are that frontal analysis tends to give more precise binding constants and can be used to independently determine both the number of binding sites that are present for a solute and the equilibrium constants for each group of sites [6].

2. General Principles of Zonal Elution Affinity Chromatography

Various types of information on how solutes bind to or compete for an immobilized agent can be obtained by zonal elution affinity chromatography. Examples include information on the strength of this binding, the effects of temperature or solvent composition on these interactions, and the effects of changing the structure of the solute or binding agent on these processes [4,6].

Each of these experiments relies on the fact that the retention of an injected solute within an affinity column is directly related to the interactions of this solute with the immobilized binding agent. This relationship can be described by using the following equation for the overall observed retention factor (k) of a solute on such a column [6,34,35].

| (1) |

The retention factor in eqn. (1) can be found from experimental data by using the standard expressions k = (tR - tM)/tM or k = (VR - VM)/VM, where tR is the retention time of the injected solute, VR is the corresponding retention volume, tM is the column void time, and VM is the void volume. Other terms that are shown in eqn. (1) include the total moles of binding sites for the solute in the column (mL), the association equilibrium constants for the solute at each binding site (KA1 through KAn), and the relative mole fraction for each type of binding site in the column (n1 through nn). Eqn. (1) shows that a solute’s retention will be a function of the solute’s binding strength for the column, the total amount of binding sites that are present, and the relative distribution of these sites. It is through this relationship that both qualitative and quantitative information can be acquired about the interaction between the injected solute and the immobilized binding agent based on careful measurements of the solute’s retention under various experimental conditions [6]. Based on the general principle, zonal elution affinity chromatography can be used for many applications (Table 1). Please see below for detailed discussion.

Table 1.

List of applications of zonal elution affinity chromatography

| Estimation of relative extent of binding |

| Determination of bound vs. free solute fractions |

| Comparison of solute retention factors |

| Competition and displacement studies |

| Characterization of type of interaction |

| Identification of competitive vs. non-competitive interactions |

| Measurement of binding strength |

| Determination of equilibrium constants for binding |

| Identification of binding forces and thermodynamic studies |

| Effects of pH or solution composition on binding |

| Effects of temperature on binding |

| Characterization of binding sites |

| Identification of binding sites |

| Effects on interaction when changing a solute’s structure |

| Effects on interaction when changing a binding agent’s structure |

| Other applications |

| Interaction of a solute with a soluble binding agent |

| Quantitative analysis of allosteric interactions |

| Analysis of solute interactions with non-covalently immobilized agents |

| Analysis of protein interactions with small immobilized targets |

3. Estimation of Relative Extent of Binding by Zonal Elution

One way zonal elution affinity chromatography has been utilized is to determine the relative degree to which an analyte or solute is binding to an immobilized agent [6]. At equilibrium, the retention factor of an injected solute on an affinity column will be equal to the ratio of its bound fraction (b) with the immobilized binding agent versus the free fraction (f) that is present in the same region of the mobile phase, where k = b/f. Because the bound and free fractions for the solute must be equal to one (i.e., f = 1 – b), it is possible to use these relationships to obtain the following equation for estimating the bound fraction of a solute based on its measured retention factor [6].

| (2) |

For instance, this method has been used with HSA columns to estimate the bound and free fractions for various drugs in the presence of this protein [36].

A similar approach can be used to compare the retention factors for related solutes on the same affinity column [6]. In the case of solutes with a single, identical binding site on an immobilized binding agent, the ratio of the retention factors for these solutes should be equal to the ratio of their association equilibrium constants at that site. Although this comparison is valid for a common single binding site, the same approach can lead to some errors when comparing the relative binding of solutes that may have different binding regions on an immobilized ligand. This situation can occur because separate binding sites on a protein may have different losses in their activity after immobilization [37,38]. Under these circumstances, the observed relative binding may give only an approximation of the solute’s behavior in solution [6].

4. Competition and Displacement Studies using Zonal Elution

Zonal elution has been employed in many reports for examining competition and displacement in solute-ligand systems [14,16–18,23–31]. In this type of study, an analyte or solute is injected into an affinity column in the presence of a mobile phase that contains a fixed concentration of a possible competing agent. An example of such a study was given earlier in Figure 2 [31]. From the change in retention that is observed for the solute as the concentration of the competing agent is varied, it can be determined whether the two solutes are interacting as they bind to the same affinity ligand [6].

The nature of this interaction can be determined by comparing the change in the measured retention with the response that is expected for various models [6]. Examples of interactions that may be present include direct competition between the injected analyte and agent in the mobile phase, allosteric interactions, or the absence of any interactions between these two chemicals on the immobilized binding agent [14,16–18,23–31]. One way these interactions can be examined is by making a plot of the retention data according to eqn. (3) [6].

| (3) |

In this equation, kA is the retention factor for the injected analyte; KA and KI are the association equilibrium constants for the analyte and the competing agent, respectively, at their site of competition; [I] is the concentration of the competing agent; and CL is the concentration of the affinity ligand in the column. A corrected retention factor equal to the term kA – X is also sometimes used instead of kA in eqn. (3), where X represents the retention factor for the injected analyte due to binding sites in the column at which competing agent has no interactions [39].

Figure 3 shows the results that are obtained for various types of interactions when a plot of 1/kA versus the competing agent concentration is made according to eqn. (3) [26]. In the absence of any competition between the analyte and mobile phase additive, a plot that is prepared in this manner shows only random variations about a horizontal line, as illustrated in Figure 3(a) for digitoxin as the injected analyte and when using glimepiride as a mobile phase additive. When direct competition is present at the same binding site for the analyte and competing agent, a linear plot with a positive slope is generated, as shown in Figure 3(b) for L-tryptophan as the analyte and in the presence of mobile phases containing glimepiride. Deviations from a positive linear response, as demonstrated in Figure 3(c) for injections of R-warfarin as the analyte and glimepiride as the mobile phase additive, can occur if a negative allosteric effect or multisite competition is present. A positive allosteric interaction results in a plot like the one shown in Figure 3(d) for tamoxifen as the analyte tamoxifen and glimepiride as the mobile phase additive, in which the value 1/kA decreases with an increase in the concentration of the agent that has been placed into the mobile phase [6].

Figure 3.

Plots made according to eqn. (3) for various injected solutes - (a) digitoxin, (b) L-tryptophan, (c) R-warfarin and (d) tamoxifen - and mobile phases containing glimepiride that were applied to HSA columns. These plots represent systems in which there was (a) no interaction between the injected solute and agent in the mobile phase for binding sites in the column, (b) direct competition of these agents at a single type of common binding site, (c) negative allosteric effects between these agents during their binding to the column, or (d) positive allosteric effects as these agents were binding to the column. Behavior similar to that in (c) can also be produced by direct competition at multiple binding sites [6]. Adapted with permission from Ref. [26].

5. Measurement of Binding Strength by Zonal Elution

Zonal elution affinity chromatography can also be utilized to obtain quantitative information about the strength of an analyte-ligand interaction. For instance, eqn. (3) can be used to describe a system in which an injected solute and a competing/interacting agent bind to the same site on an immobilized ligand [4,6]. In this situation, a plot of 1/kA versus [I] should be linear, and the ratio of the best-fit slope to the intercept should correspond to the association equilibrium constant for the competing agent (KI) at the common binding site. The association equilibrium constant for the injected analyte at the same site (KA) can be obtained from the intercept by using an independent measure of the concentration of binding sites in the column (CL). Association equilibrium constants that have been determined by this approach on HPLC systems for various drug-protein systems often have precisions of 5–10% and, when the column is prepared using appropriate immobilization conditions, give values that are consistent with those measured in solution [40].

6. Identification of Binding Forces and Thermodynamic Studies by Zonal Elution

Factors that may influence a solute-ligand interaction can also be studied by zonal elution affinity chromatography. Some of these factors include the pH, ionic strength or general content of the mobile phase [4,6]. For example, a change in the pH of the mobile phase can lead to variations in the conformation of a complex solute or binding agent and changes in the coulombic interactions between a solute and a binding agent such as a protein. An increase in ionic strength can reduce coulombic interactions due to a shielding effect; however, an increase in ionic strength can also increase binding by a non-polar solute by promoting hydrophobic interactions. A change in the mobile phase’s polarity (e.g., by adding a small amount of an organic modifier) can further alter the degree of non-polar interactions or affect retention by a solute through changes that are produced in the conformation of a binding agent such as a protein [4,41].

Figure 4 shows some examples of zonal elution studies that were carried out for this purpose. These results show the effects of changing the pH, organic modifier content of the mobile phase, and mobile phase’s ionic strength on the retention of R- and S-propranolol on HPLC columns that contained immobilized α1-acid glycoprotein (AGP) [22]. These results indicated that this binding was dependent on the pH, as indicated by Figure 4(a). In addition, hydrophobic interactions played an important role in the binding of propranolol with AGP because the retention times for R- and S-propranolol decreased significantly when even a small amount of isopropanol was added to the mobile phase, as shown in Figure 4(b). Coulombic effects also played a role in this binding, as indicated by the effects of changing the ionic strength (i.e., phosphate concentration) in Figure 4(c) [22].

Figure 4.

Change in retention with (a) pH, (b) mobile phase organic modifier content, and (c) ionic strength for R- and S-propranolol on columns containing immobilized AGP. Adapted with permission from Ref. [22].

Temperature is another factor that can be controlled and modified during zonal elution studies [21,24]. The retention data in this case can be examined by using eqn. (4) when the injected solute and immobilized agent have 1:1 binding interactions [6].

| (4) |

In this equation, T is the absolute temperature, R is the constant of ideal gas law, ΔH is the change in enthalpy for the binding process, ΔS is the change in entropy, and the other terms are as described previously [37,42–47]. The slope of a linear plot of ln k vs. 1/T, as prepared according to eqn. (4), can be used to determine the value of ΔH for the system, provided that there is no temperature dependence in the number of binding sites (mL) for the immobilized agent [36,48,49]. In addition, the value of ΔS can be acquired from the intercept of this plot if a separate estimate of (mL/VM) is available [6].

7. Characterization of Binding Sites by Zonal Elution

Another application of zonal elution affinity chromatography is to determine the location and structure of binding sites on a protein [4,6,26,28,31,50]. This can be achieved by using site-selective probes during competition studies. When such probes are used with eqn. (3), the resulting plots of 1/kA versus [I] can be utilized to provide information on binding by the competing agent at the same site that is being sampled by the injected probe. This method has been employed in a number of reports [4,6], including those that have examined binding by HSA and modified forms of HSA with various drugs at regions such as Sudlow sites I and II (i.e., the two major drug binding sites of this protein) [26,28,31]. With these probes, it is possible to generate affinity maps that show the binding constants for a given solute at specific regions on a protein. Figure 5 shows an example of this type of map for glimepiride, which describes the interactions of this pharmaceutical with the major and minor drug binding regions of HSA [26].

Figure 5.

Affinity map showing the interactions of glimepiride with the major and minor binding regions of normal and glycated HSA, as examined by competition studies and zonal elution affinity chromatography. Terms: Ka, association equilibrum constant. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [26].

An alternative way of characterizing binding sites by zonal elution affinity chromatography is to examine how a solute-ligand interaction is affected by changes in the structure of the solute [4,6]. This is the principle behind the use of zonal elution to develop a quantitative structure-retention relationship (QSRR). In a QSRR study, a large number of compounds with similar structures are injected onto a given affinity column. Based on the retention times that are measured for these compounds, the structural features of the solutes that are most important to the binding process are determined. The arrangement and nature of these features can then be used to provide a model of the site on the binding agent that is interacting with these solutes [48]. Such an approach has been used in describing the binding regions for various classes of drugs on HSA and AGP [4,6].

A complementary method to using a QSRR is to see how the retention of a solute varies as changes are made to sites on the immobilized binding agent [4,6]. One such study used HSA that had been modified by acetylation with p-nitrophenyl acetate at Tyr-411; this was followed by the use of zonal elution experiments to examine the effects of this modificaiton on the interactions of various solutes at the indole-benzodiazepine region of HSA [51]. Another report used o-nitrophenylsulphenyl chloride to modify Trp-214 at the warfarin-azapropazone site of this protein and to see how this modification affected the ability of HSA to bind to R- and S-warfarin [52]. Other examples of this approach have used modification of the lone free cysteine residue on HSA by ethacrynic acid or bismaleimidohexane, the use of BSA fragments, or the use of glycated HSA in binding studies based on zonal elution affinity chromatography [26,28,29,53–55].

8. Alternative Applications of Zonal Elution Affinity Chromatography

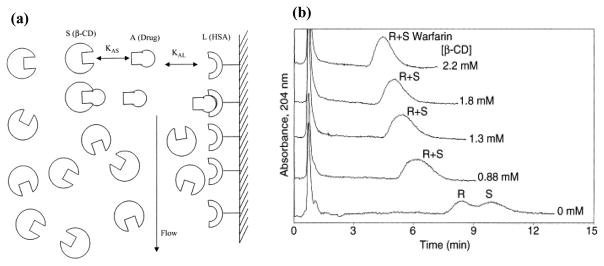

Zonal elution affinity chromatography can be employed in a number of additional formats for binding studies. For example, this method can be modified to look at the interaction of a solute with a binding agent that is present in a soluble form in the mobile phase [12,18,56]. Such an approach, as illustrated in Figure 6, has been used with HSA columns to examine the binding of drugs with soluble β-cyclodextrin [18]. This example made use of the ability of the injected drugs to bind to both immobilized HSA and to form a complex with β-cyclodextrin. As β-cyclodextrin formed a complex with a drug, the observed retention time of the drug on the HSA column decreased, making it possible to use this shift in retention to determine the association equilibrium constant for the drug:cyclodextrin complex [18].

Figure 6.

Use of zonal elution affinity chromatography to study the binding of a solute with a soluble binding agent, as illustrated here for the interaction of an injected drug (A) and with a soluble agent (S; β-cyclodextrin or β-CD) in the presence of an immobilized affinity ligand (L; HSA). The diagram in (a) shows the general model for examining this interaction, and (b) shows some chromatograms that were obtained by this approach for examining the retention and binding of R- and S-warfarin to immobilized HSA in the presence of mobile phases that contained known concentrations of β-cyclodextrin. Terms: KAS, association equilibrium constant for the binding of A with S; and KAL, association equilibrium constant for the binding of A with L. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [18].

Another modified form of zonal elution affinity chromatography has been described for the quantitative analysis of allosteric interactions by solutes with proteins [15–17,26]. This can be accomplished by using the following relationship to describe the change in retention for an injected solute during a zonal elution-based competition study [17].

| (5) |

In this equation, kA and kA,0 are the retention factors for the injected analyte (A) in the presence and absence of the competing or interacting agent (I), respectively; CI is the concentration of the interacting agent in the mobile phase; KA and KI are the association equilibrium constants for the injected analyte and the interacting agent at their binding sites in the absence of an allosteric interaction; and K’A is the association equilibrium constant for the injected analyte after an allosteric effect on the binding of A has been induced by I. The ratio K’A/KA that appears in this equation is the coupling constant for the effect of I on A [17]. An example of a plot that was prepared according to eqn. (5) is shown in Figure 7 for the allosteric effect of glimepiride on the binding of tamoxifen to HSA [26]. The same approach has been used to study the allosteric effects of R- or S-ibuprofen on the binding of HSA to benzodiazepines [15,17], and the allosteric effects of tamoxifen and warfarin on each other during their binding to HSA [16].

Figure 7.

Analysis of an allostric effect by using zonal elution affinity chromatogeraphy. This example used glimepiride in the mobile phase as an interacting agent and tamoxifen as an injected probe for the tamoxifen site on immobilized HSA. The resulting retention data were then used to prepare a plot according to eqn. (5). The same data gave a nonlinear response for the plot in Figure 3(d) that was prepared according to eqn. (3). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [26].

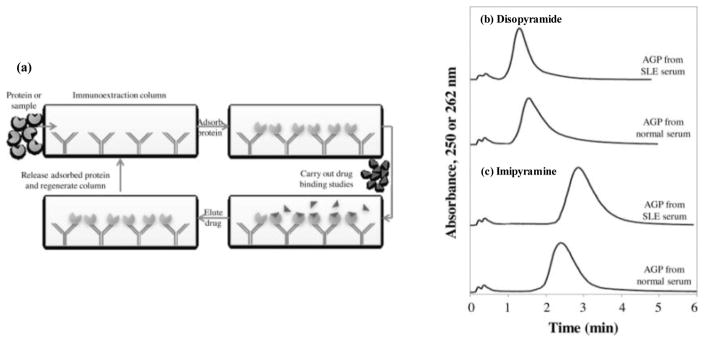

Most previous reports using zonal elution affinity chromatography have employed covalently immobilized proteins. An alternative route is to use biospecific adsorption, such as based on the binding of a protein with an immobilized antibody [14,27]. This approach has been used with small immunoextraction columns, as shown in Figure 8 for the extraction and non-covalent immobilization of AGP for use in drug binding studies [14]. In this method, the same immunoextraction column can be used to isolate a protein from various samples, and only a small amount of protein for column preparation is required [27,57,58]. This second feature has made it possible to use this format with individual patient samples, as has been demonstrated for the analysis of drug interactions with AGP that has been isolated from normal serum or from serum that was obtained with patients with systemic lupus erythematosus [14].

Figure 8.

(a) General approach based on immunoextraction for the capture of a protein and its use in drug binding studies, and (b-c) use of this approach with AGP that was isolated from normal serum or serum for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) for binding studies using disopyramide or imipramine as the injected analyte. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [14].

Zonal elution methods and affinity chromatography have also been used in a number of recent studies to examine the binding of drugs onto non-covalently immobilized receptors [59–67]. This work has involved the use of immobilized artificial membrane columns [5,33] or the adsorption of cell membranes containing specific receptors onto the surface of activated silica [59–65]. For example, cell membrane chromatography has been employed to examine single-site or multi-site interactions between drugs and receptors, such as those involving the binding sites of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 for sorafenib and taspine [19,63].

Most studies using zonal elution affinity chromatography make use of immobilized proteins; however, it is also possible to use small targets that have been adsorbed or immobilized into columns for such experiments. A recent example of this latter case involved the study of a transient protein-protein interaction between retinoic acid receptor (RARγ) and cellular retinoic acid binding proteins (CRABP) with retinoic acid that had been non-covalently bound to immobilized CRABP. The retinoic acid that was bound to the column was able to form a complex with RARγ as this receptor was injected into this column, thus delaying the elution of RARγ and allowing this interaction to be examined [20].

9. Conclusions

This review examined the theory, principles, and applications of zonal elution affinity chromatography as related to the study of solute-protein interactions or solute-solute competition for binding sites on proteins. This approach has been applied to a variety of solute-protein systems. Recent examples have included the interactions of drugs and solutes with serum transport proteins such as HSA or AGP, the binding of solutes with immobilized receptors, and the study of protein-protein interactions by using non-covalently immobilized solutes. It was shown how a wide range of information can be obtained through these experiments. This information included estimates of the relative extent of solute-protein binding, the competition of solutes for binding sites on proteins, and measurements of the strength of these interactions. It was also demonstrated how zonal elution affinity chromatography could be utilized in examining the effects of pH, mobile phase composition or temperature on this binding, as well as in characterizing solute binding sites on proteins. Other applications that were discussed were the use of zonal elution affinity chromatography for studying the binding of solutes with soluble agents and the analysis of allosteric effects.

The variety of information that can be obtained by this method should continue to make this approach appealing in the future for examining other interactions of interest to biomedical research or pharmaceutical analysis. Areas of expected growth in this field include more applications that examine drug interactions with nucleic acids or protein-protein interactions [16,68]. Improvements are also anticipated in approaches for preparing affinity columns for zonal elution, as illustrated in recent work using protein entrapment [69], immunoextraction [14,27] or other non-covalent immobilization methods [59–67]. In addition, further developments are expected in new approaches for analyzing the data that can be obtained through zonal elution, as represented by recent methods created for examining allosteric effects by this technique [15–17,26]. Such efforts should continue to expand the power and flexibility of zonal elution affinity chromatography for the study of solute-protein binding and related systems.

Zonal elution can be used in affinity chromatography to study solute-protein binding

Several solute-proteins or solute-receptor systems have been studied by this method

The strength of binding and location of binding sites can be examined by zonal elution

Competition studies and the analysis of allosteric effects are possible as well

Several other applications for zonal elution-based binding studies are also discussed

Acknowledgments

This project was funded, in part, by the National Institutes of Health under grants R01 GM044931, R01 DK069629, and P30 EY003039.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hage DS, Matsuda R. Affinity chromatography: a historical perspective. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1286:1–19. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2447-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuda R, Bi C, Anguizola J, Sobansky M, Rodriguez E, Vargas Badilla J, Zheng X, Hage B, Hage DS. Studies of metabolite-protein interactions: a review. J Chromatogr B. 2014;966:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfaunmiller EL, Paulemond ML, Dupper CM, Hage DS. Affinity monolith chromatography: a review of principles and recent analytical applications. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2013;405:2133–2145. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6568-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hage DS, Anguizola J, Barnaby O, Jackson A, Yoo MJ, Papastavros E, Pfaunmiller E, Sobansky M, Tong Z. Characterization of drug interactions with serum proteins by using high-performance affinity chromatography. Curr Drug Metabol. 2011;12:313–328. doi: 10.2174/138920011795202938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moaddel R, Wainer IW. The preparation and development of cellular membrane affinity chromatography columns. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:197–205. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hage DS, Chen J. Quantitative affinity chromatography: practical aspects. In: Hage DS, editor. Handbook of Affinity Chromatography. 2. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2006. pp. 595–628. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitos I, Visy J, Simonyi M, Hermansson J. Stereoselective allosteric binding interaction on human serum albumin between ibuprofen and lorazepam acetate. Chirality. 1999;11:115–120. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(1999)11:2<115::AID-CHIR6>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vidal-Madjar C, Jaulmes A. Theoretical Aspects of Quantitative Affinity Chromatography. In: Dondi F, Guiochon G, editors. Theoretical Advancement in Chromatography and Related Separation Techniques. Springer; Dordrecht: 1992. pp. 481–511. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnold FH, Schofield SA, Blanch HW. Analytical affinity chromatography. I. Local equilibrium theory and the measurement of association and inhibition constants. J Chromatogr. 1986;355:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)97300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vidal-Madjar C, Jaulmes A, Racine M, Sebille B. Determination of binding equilibrium constants by numerical simulation in zonal high-performance affinity chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1988;458:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Q, Wang J, Zheng YY, Yang L, Zhang Y, Bian L, Zheng J, Li Z, Zhao X, Zhang Y. Comparison of zonal elution and nonlinear chromatography in determination of the interaction between seven drugs and immobilised β2-adrenoceptor. J Chromatogr A. 2015;1401:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunn BM, Chaiken IM. Quantitative affinity chromatography. Determination of binding constants by elution with competitive inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:2382–2385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.6.2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Haj MA, Kaliszan R, Buszewski B. Quantitative structure-retention relationships with model analytes as a means of an objective evaluation of chromatographic columns. J Chromatogr Sci. 2001;39:29–38. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/39.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bi C, Matsuda R, Zhang C, Isingizwe Z, Clarke W, Hage DS. Studies of drug interactions with alpha1-acid glycoprotein by using on-line immunoextraction and high- performance affinity chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2017;1519:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.08.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Fitos I, Hage DS. Chromatographic analysis of allosteric effects between ibuprofen and benzodiazepines on human serum albumin. Chirality. 2006;18:24–36. doi: 10.1002/chir.20216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Hage DS. Quantitative studies of allosteric effects by biointeraction chromatography: analysis of protein binding for low-solubility drugs. Anal Chem. 2006;78:2672–2683. doi: 10.1021/ac052017b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J, Hage DS. Quantitative analysis of allosteric drug-protein binding by biointeraction chromatography. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1445–1448. doi: 10.1038/nbt1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, Ohnmacht CM, Hage DS. Characterization of drug interactions with soluble β-cyclodextrin by high performance affinity chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2004;1033:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du H, Wang S, Ren J, Lv N, He L. Revealing multi-binding sites for taspine to VEGFR-2 by cell membrane chromatography zonal elution. J Chromatogr B. 2012;887–888:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sjoelund V, Kaltashov IA. Modification of the zonal elution method for detection of transient protein-protein interactions involving ligand exchange. Anal Chem. 2012;84:4608–4612. doi: 10.1021/ac300104d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xuan H, Hage DS. Immobilization of α1-acid glycoprotein for chromatographic studies of drug–protein binding. Anal Biochem. 2005;346:300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xuan H, Hage DS. Evaluation of a hydrazide-linked α1-acid glycoprotein chiral stationary phase: separation of R- and S-propranolol. J Sep Sci. 2006;29:1412–1422. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200600051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang P, Hou X, Lv N, Feng L, Wang S. Cell membrane chromatography with zonal elution for characterization of seven alkaloids binding to α1A adrenoreceptor. J Liq Chromatogr Rel Technol. 2015;38:986–992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao X, Zheng X, Wei Y, Bian L, Wang S, Zheng J, Zhang Y, Li Z, Zang W. Thermodynamic study of the interaction between terbutaline and salbutamol with an immobilized β2-adrenoceptor by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B. 2009;877:911–918. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anguizola J, Bi C, Koke M, Jackson A, Hage DS. On-column entrapment of alpha1- acid glycoprotein for studies of drug-protein binding by high-performance affinity chromatography. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2016;408:5745–5756. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9677-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuda R, Li Z, Zheng X, Hage DS. Analysis of multi-site drug-protein interactions by high-performanceaffinity chromatography: binding by glimepiride to normal orglycated human serum albumin. J Chromatogr A. 2015;1408:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuda R, Jobe D, Beyersdorf J, Hage DS. Analysis of drug-protein binding using on-line immunoextraction and high-performance affinity microcolumns: studies with normal and glycated human serum albumin. J Chromatogr A. 2015;1416:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anguizola J, Joseph KS, Barnaby OS, Matsuda R, Alvarado G, Clarke W, Cerny RL, Hage DS. Development of affinity microcolumns for drug-protein binding studies in personalized medicine: interactions of sulfonylurea drugs with in vivo glycated human serum albumin. Anal Chem. 2013;85:4453–4460. doi: 10.1021/ac303734c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuda R, Anguizola J, Joseph KS, Hage DS. Analysis of drug interactions with modified proteins by high-performance affinity chromatography: binding of glibenclamide to normal and glycated human serum albumin. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1265:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.09.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xuan H, Joseph KS, Wa C, Hage DS. Biointeraction analysis of carbamazepine binding to α1-acid glycoprotein by high-performance affinity chromatography. J Sep Sci. 2010;33:2294–2301. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201000214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joseph KS, Hage DS. Characterization of the binding of sulfonylurea drugs to HSA by high-performance affinity chromatography. J Chromatogr B. 2010;878:1590–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hage DS, Sengupta A. Characterisation of the binding of digitoxin and acetyldigitoxin to human serum albumin by high-performance affinity chromatography. J Chromatogr B. 1999;724:91–100. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00589-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanghvi M, Moaddel R, Wainer IW. The development and characterization of protein-based stationary phases for studying drug-protein and protein-protein interactions. J Chromatogr A. 2011;1218:8791–8798. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.05.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dalgaard L, Hansen JJ, Pedersen JL. Resolution and binding site determination of d,l-thyronine by high-performance liquid chromatography using immobilized albumin as chiral stationary phase. Determination of the optical purity of thyroxine in tablets. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1989;7:361–368. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(89)80103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaliszan R, Noctor TAG, Wainer IW. Stereochemical aspects of benzodiazepine binding to human serum albumin. II. Quantitative relationships between structure and enantioselective retention in high performance liquid affinity chromatography. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42:512–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noctor TAG, Diaz-Perez MJ, Wainer IW. Use of a human serum albumin-based stationary phase for high-performance liquid chromatography as a tool for the rapid determination of drug-plasma protein binding. J Pharm Sci. 1993;82:675–676. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600820629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang J, Hage DS. Characterization of the binding and chiral separation of d- and l-tryptophan on a high-performance immobilized human serum albumin column. J Chromatogr A. 1993;645:241–250. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(93)83383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loun B, Hage DS. Characterization of thyroxine-albumin binding using high-performance affinity chromatography II. Comparison of the binding of thyroxine, triiodothyronines and related compounds at the warfarin and indole sites of human serum albumin. J Chromatogr B. 1995;665:303–314. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(94)00547-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noctor TAG, Wainer IW, Hage DS. Allosteric and competitive displacement of drugs from human serum albumin by octanoic acid, as revealed by high-performance liquid affinity chromatography, on a human serum albumin-based stationary phase. J Chromatogr B. 1992;577:305–315. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(92)80252-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hage DS. High-performance affinity chromatography: a powerful tool for studying serum protein binding. J Chromatogr B. 2002;768:3–30. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(01)00482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allenmark S. Chromatographic Enantioseparation: Methods and Applications. 2. Ellis Horwood; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilpin RK, Ehtesham SB, Gilpin CS, Liao ST. Liquid chromatographic studies of memory effects of silica-immobilized bovine serum albumin. I. Influence of methanol on solute retention. J Liq Chromatogr Rel Technol. 1996;19:3023–3035. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilpin RK, Ehtesham SE, Gregory RB. Liquid chromatographic studies of the effect of temperature on the chiral recognition of tryptophan by silica-immobilized bovine albumin. Anal Chem. 1991;63:2825–2828. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peyrin E, Guillaume YC, Morin N, Guinchard C. Sucrose dependence of solute retention on human serum albumin stationary phase: hydrophobic effect and surface tension considerations. Anal Chem. 1998;70:2812–2818. doi: 10.1021/ac980039a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su W, Gregory RB, Gilpin RK. Liquid chromatographie studies of silica-immobilized hew lysozyme. J Chromatogr Sci. 1993;31:285–290. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peyrin E, Guillaume YC. Chiral discrimination of N-(dansyl)-DL-amino acids on human serum albumin stationary phase. Effect of a mobile phase modifier. Chromatographia. 1998;48:431–435. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(98)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peyrin E, Guillaume YC, Guinchard C. Peculiarities of dansyl amino acid enantioselectivity using human serum albumin as a chiral selector. J Chromatogr Sci. 1998;36:97–103. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/36.2.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang J, Hage DS. Role of binding capacity versus binding strength in the separation of chiral compounds on protein-based high-performance liquid chromatography columns: Interactions of D- and L-tryptophan with human serum albumin. J Chromatogr A. 1996;725:273–285. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(95)01009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang J, Hage DS. Effect of mobile phase composition on the binding kinetics of chiral solutes on a protein-based high-performance liquid chromatography column: interactions of D- and L-tryptophan with immobilized human serum albumin. J Chromatogr A. 1997;766:15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(96)01040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basiaga SBG, Hage DS. Chromatographic studies of changes in binding of sulfonylurea drugs to human serum albumin due to glycation and fatty acids. J Chromatogr B. 2010;878:3193–3197. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noctor TAG, Wainer IW. The in situ acetylation of an immobilized human serum albumin chiral stationary phase for high-performance liquid chromatography in the examination of drug–protein binding phenomena. Pharm Res. 1992;9:480–484. doi: 10.1023/a:1015884112039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chattopadhyay A, Tian T, Kortum L, Hage DS. Development of tryptophan-modified human serum albumin columns for site-specific studies of drug-protein interactions by high-performance affinity chromatography. J Chromatogr B. 1998;715:183–190. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haginaka J, Kanasugi N. Enantioselectivity of bovine serum albumin-bonded columns produced with isolated protein fragments. J Chromatogr A. 1995;694:71–80. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(94)00692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haginaka J, Kanasugi N. Enantioselectivity of bovine serum albumin-bonded columns produced with isolated protein fragments. II. Characterization of protein fragments and chiral binding sites. J Chromatogr A. 1997;769:215–223. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(97)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng X, Podariu M, Bi C, Hage DS. Development of enhanced capacity affinity microcolumns by using a hybrid of protein cross-linking/modification and immobilization. J Chromatogr A. 2015;1400:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andrews P, Kitchen BJ, Winzor DJ. Use of affinity chromatography for the quantitative study of acceptor-ligand interactions: the lactose synthetase system. Biochem J. 1973;135:897–900. doi: 10.1042/bj1350897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vuignier K, Schappler J, Veuthey JL, Carrupt PA, Martel S. Drug-protein binding: a critical review of analytical tools. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;398:53–66. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3737-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hage DS, Anguizola JA, Jackson AJ, Matsuda R, Papastavros E, Pfaunmiller E, Tong Z, Vargas-Badilla J, Yoo MJ, Zheng X. Chromatographic analysis of drug interactions in the serum proteome. Anal Methods. 2011;3:1449–1460. doi: 10.1039/C1AY05068K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hage DS, Phillips TM. Immunoaffinity chromatography. In: Hage DS, editor. Handbook of Affinity Chromatography. 2. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2006. pp. 127–172. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ohnmacht CM, Schiel JE, Hage DS. Analysis of free drug fractions using near-infrared fluorescent labels and an ultrafast immunoextraction/displacement assay. Anal Chem. 2006;78:7547–7556. doi: 10.1021/ac061215f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Muhammad S, Han S, Xie X, Wang S, Aziz MM. Overview of online two-dimensional liquid chromatography based on cell membrane chromatography for screening target components from traditional Chinese medicines. J Sep Sci. 2017;40:299–313. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201600773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yue Y, Dou L, Wang X, Xue H, Song Y, Li X. Screening β1AR inhibitors by cell membrane chromatography and offline UPLC/MS method for protecting myocardial ischemia. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2015;115:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma W, Zhang D, Li J, Che D, Liu R, Zhang J, Zhang Y. Interactions between histamine H1 receptor and its antagonists by using cell membrane chromatography method. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2015;67:1567–1574. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Du H, Ren J, Wang S, He L. Cell membrane chromatography competitive binding analysis for characterization of α1A adrenoreceptor binding interactions. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;400:3625–3633. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5026-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang L, Ren J, Sun M, Wang S. A combined cell membrane chromatography and online HPLC/MS method for screening compounds from Radix Caulophylli acting on the human α1A-adrenoceptor. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2010;51:1032–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Du H, He J, Wang S, He L. Investigation of calcium antagonist-L-type calcium channel interactions by a vascular smooth muscle cell membrane chromatography method. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;397:1947–1953. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3730-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Y, Yuan B, Deng X, He L, Wang S, Zhang Y, Han Q. Comparison of alpha 1-adrenergic receptor cell-membrane stationary phases prepared from expressed cell line and from rabbit hepatocytes. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2006;386:2003–2011. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0859-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Šípová H, Homola J. Surface plasmon resonance sensing of nucleic acids: a review. Anal Chim Acta. 2013;773:9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mohamad NR, Marzuki NHC, Buang NA, Huyop F, Wahab RA. An overview of technologies for immobilization of enzymes and surface analysis techniques for immobilized enzymes. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2015;29:205–220. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2015.1008192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]