Abstract

Objective:

The primary goal of this study was to examine the associations between baseline body image dissatisfaction (BID) and subsequent anxiety trajectories in a diverse, community sample of adolescent girls and boys.

Method:

Participants were 581 adolescents (baseline age: M=16.1, SD=0.7; 58% female; 65% non-Hispanic White) from U.S. public high schools. Self-report questionnaires were administered during school at three annual assessment waves. Latent growth curve modeling examined the association between baseline BID and growth factors of anxiety disorder symptom trajectories. Covariates included baseline gender, age, race/ethnicity, parental education attainment, body mass index standard scores (BMI-z), and depressive symptoms.

Results:

Higher BID at baseline was significantly associated with higher initial symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), and significant school avoidance (SSA; ps=.001-.04), but was unrelated to initial separation anxiety disorder (SEP) symptoms (p=.27). Higher baseline BID also was associated with attenuated decreases in SAD symptoms across time (p=.001). Among adolescents with low baseline anxiety symptoms only, higher BID was associated with more attenuated decreases in SAD symptoms (p=.01) and greater increases in PD symptoms (p=.02). BID was unrelated to changes in GAD, SEP, and SSA symptoms (ps=.11-.94).

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that BID is associated with concurrent symptoms of multiple anxiety disorders; and may have a prospective link to SAD and PD symptoms during adolescence. As such, assessing body image issues may be important to assess when identifying adolescents at risk for exacerbated SAD and PD symptoms.

Keywords: body image, body dissatisfaction, physical appearance, anxiety, adolescents

Adolescence represents a high risk developmental period for the emergence and exacerbation of anxiety disorder symptoms (Beesdo-Baum & Knappe, 2012). Nearly one-third of U.S. adolescents report the presence of at least one anxiety disorder (Merikangas et al., 2010). Adolescents reporting anxiety disorder symptoms, at both subthreshold and full-syndrome levels, are at greater risk for the onset and/or persistence of anxiety disorders later in adolescence and adulthood (Beesdo-Baum & Knappe, 2012). Furthermore, elevated anxiety disorder symptoms during adolescence are associated with high rates of psychiatric comorbidity, significant impairment in social and academic domains, and increased health service utilization (Kendall et al., 2010; Merikangas et al., 2010).

Body image satisfaction, which refers to individuals’ perceptions of their physical appearance and the thoughts and/or feelings resulting from these perceptions (Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe, & Tantleff-Dunn, 1999), tends to decrease from childhood into adolescence, following the onset of puberty and an increased salience of physical appearance for both girls and boys (Bully & Elosua, 2011). Body image dissatisfaction is common among adolescents, with prevalence rates ranging from 30–80% (Dion et al., 2015). Moreover, such dissatisfaction confers increased risk for the onset of eating disorders, depression, substance use and abuse, and suicidality in adolescents (du Roscoät, Legleye, Guignard, Husky, & Beck, 2016; Field et al., 2014; Paxton, Neumark-Sztainer, Hannan, & Eisenberg, 2006; Stice, 2002).

Body image dissatisfaction also may play a role in the etiology of anxiety disorder symptoms in adolescents. Sociocultural models of body image dissatisfaction and eating disorder psychopathology (Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2012; Stice, 2001; Thompson et al., 1999) propose that perceived pressure from family, peer, and the media to conform to sociocultural body ideals leads individuals to internalize these ideals as being their personal standard, central to their self-worth, and important to attain. Such body ideal internalization gives rise to appearance-based social comparisons with others and body surveillance (i.e., thinking about how one’s body looks to others) (Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 1999), which often elicits poor perceived physical appearance because these body ideals are extremely difficult to achieve. Body dissatisfaction subsequently is posited to lead to negative affect because physical appearance is central to self-evaluations. Prior theories have focused on negative affect as being comprised of depressive symptoms and poor self-esteem (Stice, 2001). However, there are theoretical and empirical reasons that anxiety disorder symptoms, as a component of negative affect, also would emerge and/or worsen in response to body image dissatisfaction via sociocultural mechanisms.

Several eating disorder models posit that anxiety may function as a core mechanism through which body image dissatisfaction leads to and maintains disordered eating behaviors (Aspen, Darcy, & Lock, 2013; Pallister & Waller, 2008). Actual and potential negative evaluations about one’s physical appearance are hypothesized to become feared outcomes that pose substantial threats to the self and one’s sense of worth among individuals who internalize sociocultural body ideals. As such, perceived pressures to conform to sociocultural body ideals, weight- and shape-related teasing or rejection, appearance-based social comparisons, and body surveillance are conceptualized as potent social evaluative threats. Among individuals who develop body image dissatisfaction, exposure to appearance-related social evaluative threats is hypothesized to give rise to biased implicit attention and memory for appearance-related stimuli and explicit rumination about feared or actual consequences of negative evaluations. These cognitive vulnerabilities are posited to elicit anxiety symptoms directly and also result in the implementation of safety behaviors that seek to gain control and prevent feared consequences (e.g., self-weighing to ameliorate weight gain fears) that then paradoxically exacerbate anxiety.

Adolescents may be especially susceptible to experiencing anxiety in response to body dissatisfaction and sociocultural pressures about physical appearance ideals. The pressure to conform to sociocultural ideals and engage in social comparisons with peers is of central importance during this developmental period (Rose & Rudolph, 2006), making negative appearance-based evaluations especially salient (Myers & Crowther, 2009). Relative to children and adults, adolescents also experience a neural imbalance between enhanced corticolimbic circuit sensitivity to perceived threats and immature cognitive control circuitry that occurs as a function of normative brain development (Somerville & Casey, 2010). As such, adolescents with body image dissatisfaction may experience heightened anxiety responses upon exposure to appearance-related social evaluative threats, but have a limited capacity to regulate emotions, cognitive vulnerabilities, and safety behaviors. The influence of body image dissatisfaction on anxiety disorder symptoms, therefore, may be particularly robust among adolescents and represent an important intervention target during this high risk developmental period.

In support of these theoretical tenets, body image dissatisfaction consistently has been associated with more concurrent overall anxiety symptoms and, specifically, more symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), and separation anxiety disorder (SEP) in community samples of adolescents (Abdollahi, Abu Talib, Mobarakeh, Momtaz, & Mobarake, 2015; Cruz-Sáez, Pascual, Salaberria, & Echeburúa, 2015; Dooley, Fitzgerald, & Giollabhui, 2015; Duchesne et al., 2016; Ferguson, Munoz, Contreras, & Velasquez, 2011; Hughes & Gullone, 2011; Ivarsson, Svalander, Litlere, & Nevonen, 2006; Touchette et al., 2011). Conversely, adolescents with better body image satisfaction report lower anxiety symptoms (Cromley et al., 2012; Koronczai et al., 2013). Despite consistent cross-sectional associations, few studies have examined the prospective relationship between body image dissatisfaction and anxiety disorder symptoms. In the only known prospective study involving adolescents, higher baseline body image satisfaction was associated with lower trait and state anxiety one year later (Ohannessian, Lerner, Lerner, & von Eye, 1999). Overall, existing research suggests that body image satisfaction may play a role in the etiology of anxiety in adolescents. Yet, it is crucial for advancing developmental risk models and interventions for research to investigate the unique role of body image dissatisfaction in trajectories of specific facets of anxiety disorder symptoms (rather than total anxiety symptoms) during adolescence.

The Present Study

Adolescence represents a critical risk period for the development and exacerbation of anxiety disorder symptoms, underscoring the importance of identifying novel risk factors to improve screening, early identification, and intervention efforts. Body image dissatisfaction, which also carries a heightened salience during adolescence, has been proposed to contribute to the emergence and worsening of negative affect (Stice, 2001). Although sociocultural theories have focused on depressive symptoms and self-esteem at the exclusion of anxiety, preliminary evidence and theories that consider cognitive behavioral mechanisms suggest that body image dissatisfaction also may influence the etiology of anxiety disorder symptoms (Aspen et al., 2013; Ohannessian et al., 1999; Pallister & Waller, 2008). Body image dissatisfaction appears to be a modifiable risk factor, as several interventions targeting improvements in body image satisfaction have been effective in reducing risk for adverse psychological outcomes (Atkinson & Wade, 2015; McLean, Wertheim, Marques, & Paxton, 2016; Stice, Marti, Spoor, Presnell, & Shaw, 2008; Wilksch & Wade, 2009, 2014). Therefore, elucidating the role of body image dissatisfaction in specific anxiety disorder symptoms trajectories among adolescents has the potential to yield significant theoretical and clinical implications.

In addition, several notable gaps in the literature examining body image dissatisfaction and anxiety remain. First, the majority of studies include only females, limiting the generalizability of findings to males who also experience body dissatisfaction and anxiety at high rates (Dion et al., 2015; Merikangas et al., 2010). In addition, although prior studies often have included demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status) and body composition as covariates, most studies have failed to adjust for depressive symptoms in the analyses. Similar to these to these other covariates (Anderson & Mayes, 2010; Beesdo-Baum & Knappe, 2012; Gariepy, Nitka, & Schmitz, 2010; Kimber, Couturier, Georgiades, Wahoush, & Jack, 2015; Ohannessian, Milan, & Vannucci, 2017; Pelegrini et al., 2014), depressive symptoms are associated with both anxiety symptoms and body image dissatisfaction (Kendall et al., 2010; Stice, 2001). As such, it is unclear as to whether the relationship between body image dissatisfaction and anxiety persists beyond the effects of depressive symptoms. Finally, no known prospective studies have examined the relationship between body image dissatisfaction and specific facets of anxiety disorder symptoms, with existing work focusing on total anxiety. Although there are core features common across all anxiety disorders, anxiety nonetheless is a heterogeneous construct with many presentations (e.g., GAD, PD, SAD, SEP, among others) that have diverse implications for etiology and treatment.

Given these limitations, the current study sought to examine the associations between baseline body image dissatisfaction and subsequent anxiety disorder symptom trajectories in a large, diverse community sample of adolescent girls and boys. We hypothesized that adolescents with higher body image dissatisfaction at baseline would report higher concurrent GAD, PD, SAD, SEP, and significant school avoidance (SSA) symptoms, as well as greater increases (or more attenuated decreases) in these symptoms over time, above and beyond the effects of demographic characteristics, body composition, and depressive symptoms.

Method

Participants

All adolescents who were enrolled full-time in the 10th and 11th grades at seven public high schools in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States (U.S.) were eligible for the study. Participants who completed self-reports of their demographic characteristics, body image dissatisfaction, and anxiety disorder symptoms were included in the present study. There were no additional exclusion criteria. At baseline, the sample was comprised of 678 adolescent girls and boys (58% female; Age: M = 16.07, SD = 0.71 years). The race/ethnicity composition was: 65% non-Hispanic White, 18% African American, 9% Hispanic, 3% Asian, and 5% “Other.” Adolescents reported their parents’ highest level of education completed as follows: less than high school for 4% of mothers, 3% of fathers; high school for 39% of mothers, 46% of fathers; two years of college for 20% of mothers, 18% of fathers; four years of college for 28% of mothers, 25% of fathers; and graduate/medical school for 9% of mothers, 8% of fathers.

Procedures

All 10th and 11th grade students enrolled at seven public high schools located within 60 miles of the study site (Newark, Delaware, U.S.) were invited to participate in a longitudinal study of adolescent adjustment via an invitation letter sent directly to parents. Parents provided informed consent passively, which was indicated by a non-response to the research team. Parents who did not want their adolescents to participate (<1%) contacted the research team directly. Adolescents provided assent for their participation until age 18, at which time participants provided their own informed consent. Approximately 20% of students were absent on the day of data collection, and 3% of adolescents declined participation. Participating adolescents completed self-report surveys during the spring of 2007 (Time 1), 2008 (Time 2), and 2009 (Time 3). Trained research personnel administered surveys in schools. Adolescents who were not present on the day of data collection were mailed surveys to complete at home and return to the research team. Participants who graduated from high school were invited to take an online version of the survey. The survey took approximately 40 minutes to complete. At each time point, participants were given a movie pass upon turning in their survey. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained to protect the participants’ privacy. All procedures were approved by the University of Delaware Institutional Review Board.

Participants with data from at least two assessment waves were included in the current study (N = 581). There were no significant differences between the full baseline sample (N = 678) and this subsample with regard to demographic characteristics and baseline body image dissatisfaction, anxiety disorder symptoms, and depressive symptoms (ps > .05). Data were missing for 4.3% of participants at Time 2 and 22.8% of participants at Time 3, respectively. Participants with data missing for at least one assessment wave (Age: M = 16.12, SD = 0.71 years) were significantly older than those who were not missing any data (Age: M = 15.83, SD = 0.64 years), t(554) = -3.53, p = .002. However, there were no systematic differences between those with and without missing data in other demographic characteristics or baseline anxiety disorder symptoms, depressive symptoms, or body image dissatisfaction (ps > .05).

Measures

Body image dissatisfaction.

The Physical Appearance Self-Competence subscale of the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (SPPA; Harter, 2012) assessed adolescents’ degree of satisfaction with their physical appearance at baseline. This subscale was comprised of 5 items that were presented in a structured alternative format (sample item: Some teenagers wish their body was different but other teenagers like their body the way it is). For each item, adolescents chose which description fit them the best and then rated whether that description was sort of true or really true for them. Items were scored on a 4-point scale and summed to generate the subscale. The subscale score subsequently was reverse coded so that higher scores reflected higher body image dissatisfaction. The SPPA has demonstrated good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity in adolescents (Harter, 2012). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .88 in the current study.

Anxiety disorder symptoms.

The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher, Khetarpal, Cully, Brent, & McKenzie, 1995) assessed anxiety disorder symptoms at Times 1–3. Adolescents rated how frequently they experienced 41 anxiety symptom descriptions over the past three months (sample item: I feel nervous with people I don’t know well). The response scale ranged from 0 = not true or hardly ever true to 2 = very true or often true. Responses were summed to generate the SCARED subscales, which included: GAD (9 items), PD (13 items), SAD (7 items), SEP (8 items), and SSA (4 items). The SCARED possesses excellent reliability and good convergent validity with clinical assessment measures in adolescent samples (Muris, Merckelbach, Ollendick, King, & Bogie, 2002). The Cronbach alpha coefficients for the SCARED subscales in the current study had the following ranges across time points: GAD = .87-.88, PD = .87-.88, SAD = .84-.88, SEP = .78-.80, and SSA = .70-.71.

Demographic information.

A demographic questionnaire assessed participants’ baseline gender (male or female), age (years), race/ethnicity (white, black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, Asian, and “other”), and their parents’ highest level of education completed (less than high school, high school, two years of college, four years of college, graduate or medical school).

Body composition.

Adolescents reported on their weight and height, which was used to calculate their body mass index (BMI) as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). Numerous studies have found high correlations between self-reported and actual measured weight and height, as well as BMI calculated from these metrics in adolescents (rs = .82-.96; De Vriendt, Huybrechts, Ottevaere, Van Trimpont, & De Henauw, 2009). BMI standard (BMI-z) scores adjusted for age and sex were calculated based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts (Kuczmarski et al., 2002).

Depressive symptoms.

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC; Weissman, Orvaschel, & Padian, 1980) assessed depressive symptoms in the past week at baseline. The CES-DC is a 20-item self-report measure with item responses ranging from 1 = not at all to 4 = a lot. A total score is generated by summing the responses. The CES-DC is a reliable and valid measure of depressive symptoms in adolescents (Garrison, Addy, Jackson, McKeown, & Waller, 1991). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .90 in this study.

Analytic Plan

Data were screened for normality. All continuous variables exhibited satisfactory skew (values ranged from -0.08 to 1.70) and satisfactory kurtosis (values ranged from -0.62 to 5.99), and no outliers were identified. Analyses were conducted with Mplus version 7.4 software (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2015).

Latent growth curve modeling using the structural equation modeling framework (Wickrama, Lee, O’Neail, & Lorenz, 2016) was conducted to examine whether baseline body image dissatisfaction was associated with the initial level and subsequent changes in anxiety disorder symptoms. Factor loadings for the latent slope factor were set at 0, 1, and 2 for anxiety disorder symptoms observed at Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3, respectively. A linear slope function was evaluated. Although a non-significant Chi-square test indicates adequate model fit, this test statistic is highly sensitive to sample size and therefore often inflated and significant with large samples despite very small departures in how well the model reproduces the variance-covariance matrix (Wickrama et al., 2016). Therefore, acceptable model fit was indicated by values of the comparative fit index (CFI) greater than .95 and values of the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), the upper limit of the RMSEA’s 90% confidence interval, and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) less than .08 (Wickrama et al., 2016).

For each anxiety disorder symptom trajectory, an initial unconditional latent growth curve model was estimated to confirm the appropriateness of using a linear slope function. Subsequently, conditional latent growth curve models were estimated to investigate the effects of baseline body image dissatisfaction on growth factors of anxiety disorder symptom trajectories. Five models were estimated to examine GAD, PD, SAD, SEP, and SSA symptom trajectories. In each model, body image dissatisfaction was included as the predictor and baseline reports of gender, age, race/ethnicity, mean parental education status (as a proxy of socioeconomic status), BMI-z scores, and depressive symptoms were included as covariates. These covariates were selected because prior literature has suggested that each construct is systematically linked to both body image dissatisfaction and anxiety symptoms (Anderson & Mayes, 2010; Beesdo-Baum & Knappe, 2012; Gariepy et al., 2010; Kimber et al., 2015; Ohannessian et al., 2017; Olino, Klein, Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 2010; Pelegrini et al., 2014; Stice & Shaw, 2002). Associations were considered statistically significant at p values < .05.

As described in the procedures section, data were determined to be missing at random. The full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation approach was applied to handle missing data, which uses all available data to produce maximum likelihood-based sufficient statistics (Wothke, 2000). FIML yields unbiased parameter estimates, preserves sample size, and minimizes potential missingness biases (Wothke, 2000). Notably, follow-up sensitivity analyses revealed the same pattern of results when including only individuals with complete data.

Results

Bivariate correlations for baseline variables indicated that higher body image dissatisfaction was significantly associated with higher BMI-z scores (r = .17, p < .001) and more depressive symptoms (r = .38, p < .001). Higher baseline body image dissatisfaction also was correlated with lower parental education (r = -.10, p = .049), but there were no significant gender or race/ethnicity differences (ps ≥ .10).

Unconditional Latent Growth Curve Models

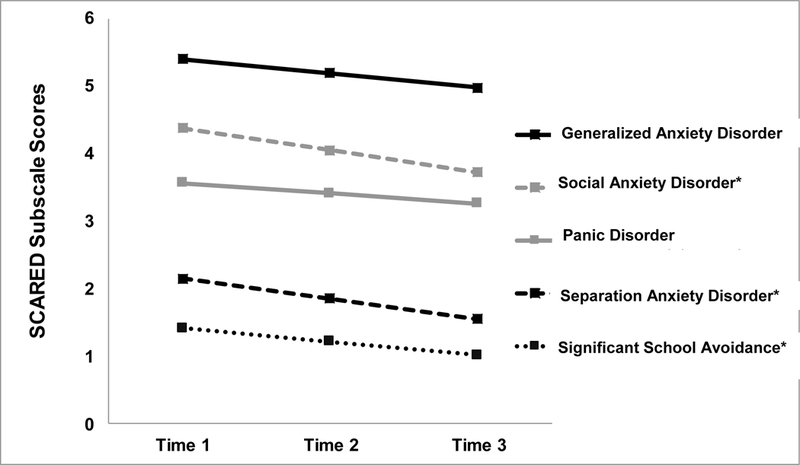

Fit indices from unconditional latent growth curve models indicated that a linear slope function was a good fit for all anxiety disorder symptom trajectories (Chi-Square test ps = .01-.66; CFIs = .96–1.00; RMSEAs, RMSEA Upper 90% CIs, and SRMRs = .003-.07). Table 1 depicts the unstandardized parameter estimates across all anxiety disorder symptom trajectories. Figure 1 displays the estimated growth factors for each trajectory. The mean intercept factor scores differed significantly from zero for GAD, PD, SAD, SEP, and SSA symptoms (ps < .001). Significant negative slope factor scores were observed for SAD, SEP, and SSA symptoms (ps ≤ .002), suggesting overall decreases across time. Mean slope factor scores did not significantly differ from zero for GAD and PD symptoms (ps = .10-.30), suggesting an overall stable course.

Table 1.

Unstandardized Parameter Estimates for Unconditional Latent Growth Curve Models of Anxiety Disorder Symptom Trajectories in Adolescents.

| GAD Symptoms | PD Symptoms | SAD Symptoms | SEP Symptoms | SSA Symptoms | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | p-value | Estimate | SE | p-value | Estimate | SE | p-value | Estimate | SE | p-value | Estimate | SE | p-value |

| Intercept | |||||||||||||||

| Mean | 5.40 | 0.19 | <.001 | 3.56 | 0.19 | <.001 | 4.38 | 0.15 | <.001 | 2.15 | 0.11 | <.001 | 1.41 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| Variance | 18.90 | 1.14 | <.001 | 19.38 | 2.13 | <.001 | 11.80 | 0.71 | <.001 | 3.31 | 0.57 | <.001 | 2.13 | 0.21 | <.001 |

| Linear Slope | |||||||||||||||

| Mean | -0.21 | 0.13 | .10 | -0.15 | 0.14 | .30 | -0.33 | 0.10 | .002 | -0.30 | 0.07 | <.001 | -0.20 | 0.04 | <.001 |

| Variance | 3.01 | 0.64 | <.001 | 4.92 | 1.16 | <.001 | 1.85 | 0.42 | <.001 | -0.15 | 0.35 | .67 | 0.48 | 0.10 | <.001 |

| I-S Covariance | -7.96 | 0.64 | <.001 | -9.60 | 1.49 | <.001 | -5.16 | 0.42 | <.001 | -0.18 | 0.40 | .66 | -0.76 | 0.13 | <.001 |

Note: GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder; PD = Panic Disorder; SAD = Social Anxiety Disorder; SEP = Separation Anxiety Disorder; SSA = Significant School Avoidance; I = Intercept; S = Slope.

Figure 1. Estimated Growth Factors of Anxiety Trajectories from Unconditional Latent Growth Curve Models.

Note: SCARED = Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders.

* Slope factors of these anxiety trajectories were statistically significant (ps < .001), suggesting overall decreases in symptoms over time.

The variances of the intercept factors were statistically significant for GAD, PD, SAD, SEP, and SSA symptoms (ps < .001), which indicated the presence of substantial inter-individual variability in adolescents’ initial symptom levels. The variances of the slope factors also were statistically significant for GAD, PD, SAD, and SSA symptoms (ps < .001), which suggested the presence of substantial variability in adolescents’ rates of change in these anxiety disorder symptoms. However, the slope factor variance was not significant for SEP symptoms (p = .67), suggesting that most adolescents reported similar decreases in SEP symptoms. Finally, there was significant, negative covariance between the intercept and slope factors for GAD, PD, SAD, and SSA symptoms (ps < .001), which indicated that adolescents with higher initial anxiety disorder symptoms tended to have greater decreases in these symptoms across time. The covariance between intercept and slope factors was not significant for SEP symptoms (p = .66).

Conditional Latent Growth Curve Models

Fit indices from conditional latent growth curve models indicated that all anxiety disorder symptom trajectory models including baseline body image dissatisfaction and covariates were a good fit (Chi-Square test ps = .01-.98; CFIs = .96–1.00; RMSEAs, RMSEA Upper 90% CIs, and SRMRs = .002-.07). Table 2 displays the unstandardized parameter estimates for adjusted models. Higher ratings of body image dissatisfaction at baseline were significantly associated with higher mean intercept factor scores for GAD, SAD, PD, and SSA symptoms (ps < .05), indicating that adolescents reporting greater body image dissatisfaction had lower higher anxiety disorder symptoms. Baseline body image dissatisfaction was unrelated to the intercept factor score for SEP symptoms (p = .27). There was a significant association between baseline body image dissatisfaction and mean slope factor scores for SAD symptoms (p = .001), which suggested that adolescents reporting higher body image dissatisfaction experienced more attenuated decreases and/or greater increases in SAD symptoms across time. There was no significant association between body image dissatisfaction and slope factor scores for GAD, PD, SEP, and SSA symptoms (ps =.11-.94).

Table 2.

Unstandardized Parameter Estimates of the Conditional Latent Growth Curve Models Examining Associations Between Baseline Body Image Dissatisfaction and Anxiety Disorder Symptom Trajectory Growth Factors in Adolescents.

| Intercept Factor | Linear Slope Factor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ | SE | p value | γ | SE | p value | |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) Symptoms | ||||||

| Age | 0.23 | 0.21 | .25 | -0.01 | 0.18 | .99 |

| Gender | -1.45 | 0.31 | < .001 | 0.35 | 0.27 | .20 |

| Race/Ethnicity | -0.03 | 0.32 | .92 | 0.14 | 0.28 | .63 |

| Parental Education | -0.07 | 0.15 | .65 | -0.25 | 0.14 | .07 |

| BMI-z | 0.22 | 0.17 | .18 | 0.01 | 0.15 | .94 |

| Depressive Symptoms | -0.16 | 0.04 | < .001 | 0.07 | 0.01 | < .001 |

| Body Image Satisfaction | 0.24 | 0.04 | < .001 | -0.06 | 0.04 | .11 |

| Panic Disorder (PD) Symptoms | ||||||

| Age | 0.21 | 0.21 | .30 | -0.04 | 0.19 | .83 |

| Gender | -1.19 | 0.31 | < .001 | 0.68 | 0.28 | .02 |

| Race/Ethnicity | -0.60 | 0.32 | .06 | 0.47 | 0.29 | .11 |

| Parental Education | 0.18 | 0.15 | .24 | -0.28 | 0.14 | .05 |

| BMI-z | 0.11 | 0.17 | .52 | 0.05 | 0.16 | .76 |

| Depressive Symptoms | -0.15 | 0.02 | < .001 | 0.08 | 0.01 | < .001 |

| Body Image Satisfaction | 0.15 | 0.05 | .01 | 0.06 | 0.04 | .13 |

| Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) Symptoms | ||||||

| Age | 0.06 | 0.19 | .75 | 0.02 | 0.15 | .90 |

| Gender | -0.77 | .29 | .008 | 0.36 | 0.22 | .10 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.33 | 0.30 | .27 | -0.19 | 0.23 | .39 |

| Parental Education | 0.14 | 0.15 | .33 | -0.13 | 0.11 | .23 |

| BMI-z | 0.18 | 0.16 | .27 | 0.10 | 0.12 | .39 |

| Depressive Symptoms | -0.04 | 0.01 | .004 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .29 |

| Body Image Satisfaction | 0.26 | 0.04 | < .001 | -0.10 | 0.03 | .001 |

| Separation Anxiety Disorder (SEP) Symptoms | ||||||

| Age | -0.02 | 0.13 | .86 | -0.04 | 0.10 | .68 |

| Gender | -0.83 | 0.19 | < .001 | 0.05 | 0.15 | .73 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.19 | 0.20 | .33 | 0.09 | 0.15 | .55 |

| Parental Education | 0.21 | 0.09 | .03 | -0.04 | 0.07 | .63 |

| BMI-z | -0.03 | 0.10 | .78 | -0.08 | 0.08 | .32 |

| Depressive Symptoms | -0.05 | 0.01 | < .001 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .65 |

| Body Image Satisfaction | 0.03 | 0.03 | .27 | -0.01 | 0.02 | .94 |

| Significant School Avoidance (SSA) Symptoms | ||||||

| Age | 0.03 | 0.08 | .67 | -0.10 | 0.06 | .10 |

| Gender | -0.42 | 0.12 | < .001 | 0.01 | -.09 | .98 |

| Race/Ethnicity | -0.12 | 0.12 | .34 | 0.21 | 0.09 | .03 |

| Parental Education | 0.04 | 0.06 | .47 | 0.01 | 0.05 | .88 |

| BMI-z | 0.03 | 0.06 | .66 | -0.01 | 0.05 | .86 |

| Depressive Symptoms | -0.05 | 0.01 | < .001 | 0.02 | 0.01 | < .001 |

| Body Image Satisfaction | 0.03 | 0.02 | .04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .42 |

Notes: BMI-z = body mass index standard scores adjusted for age and sex. Gender was coded as female = 1 and male = 0. Race/ethnicity was coded as non-Hispanic white = 1 and other = 0. p values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Exploratory Post-Hoc Analyses

Adolescents without elevated anxiety disorder symptoms.

To evaluate whether body image dissatisfaction predicted trajectories involving the initial onset of anxiety symptoms, conditional latent growth curve models were conducted that excluded participants who met the clinical cutoff for any of the anxiety disorder subscales or total score (n = 103; 18% of original sample). Fit indices from conditional latent growth curve models indicated that all models were a good fit (Chi-Square test ps = .01-.96; CFIs = .95–1.00; RMSEAs, RMSEA Upper 90% CIs, and SRMRs = .001-.08). Higher body image dissatisfaction was significantly associated with higher initial GAD, PD, SAD, and SSA symptoms (ps < .01), but was unrelated to initial SEP symptoms (p = .64). There were significant associations between baseline body image dissatisfaction and mean slope factor scores for SAD and PD symptoms (ps = .01-.02), which suggested that adolescents reporting higher baseline body image dissatisfaction experienced more attenuated decreases in SAD symptoms and greater decreases in PD symptoms over time. There was no association between body image dissatisfaction and slope factor scores for GAD, SEP, and SSA symptoms (ps = .18-.71).

Gender differences in full sample.

In light of theory hypothesizing that the link between body image dissatisfaction and negative affect may be more robust among adolescent girls relative to boys (Klump, 2013; Stice, 2001), multiple group analysis using nested model comparisons was conducted to test whether there were gender differences in the degree to which baseline body image dissatisfaction was associated with anxiety disorder symptom trajectory parameters. No significant gender differences were observed.

Discussion

The objective of this prospective study was to investigate whether body image dissatisfaction was associated with concurrent anxiety disorder symptoms and subsequent anxiety trajectories in a community sample of adolescent girls and boys. Findings indicated that adolescents reporting higher body image dissatisfaction at baseline had higher initial symptoms of GAD, PD, SAD, and SSA. Strikingly, higher body image dissatisfaction predicted more attenuated decreases in SAD symptoms and more accelerated increases in PD symptoms. These relationships were observed even after accounting for the effects of age, gender, race/ethnicity, parent education, body composition, and depressive symptoms. These novel prospective findings suggest that body image dissatisfaction contributes to differential changes in SAD symptoms and worsening of PD symptoms during adolescence. As such, it may be worthwhile for sociocultural models to include SAD and PD symptoms into the construct of negative affect and integrate cognitive behavioral and neural mechanisms into these models.

The overall trajectories of GAD and PD symptoms were stable across two years from middle-to-late adolescence, whereas SAD, SEP, and SSA symptom trajectories decreased over time. These findings are consistent with developmental theories suggesting that the predominant manifestation of specific anxiety symptoms is linked to developmental tasks and contexts (Weems, 2008). SEP tends to predominate during childhood as a result of attachment-related fears, then decreases throughout adolescence as youth gain autonomy (Hale, Raaijmakers, Muris, & Meeus, 2008; Nelemans et al., 2014). SAD emerges in early adolescence due to increases in the salience of peers and social comparisons to self-evaluations (Beesdo-Baum & Knappe, 2012), which may then either stabilize or decrease as youth gain experience with navigating their diverse social contexts (Hale et al., 2008; Nelemans et al., 2014). GAD and PD often emerge in adolescence and predominate into adulthood with increased performance- and future-oriented fears (Beesdo-Baum & Knappe, 2012). To this end, GAD and PD symptoms tend to remain relatively stable throughout the middle-to-late adolescent period (Ohannessian et al., 2017).

Consistent with prior cross-sectional studies in adolescent samples (Abdollahi et al., 2015; Ivarsson et al., 2006; Touchette et al., 2011), body image dissatisfaction exhibited concurrent associations with GAD, PD, and SAD symptoms. Although body dissatisfaction has been linked to SEP symptoms in adolescents (Ivarsson et al., 2006; Touchette et al., 2011), this relationship was not observed in the current study. Extending prior work, adolescents with higher body image dissatisfaction also reported higher anxiety-related SSA symptoms. Indeed, sociocultural theories (Stice, 2001; Thompson et al., 1999) suggest that adolescents who are dissatisfied with their bodies internalize pressures from peers to adhere to sociocultural body ideals or engage in unfavorable appearance-based comparisons with peers. The perceived peer pressure, appearance-related teasing, and social comparisons may, in turn, lead to increased anxiety and avoidance about attending school among those with poor body image.

Higher baseline body image dissatisfaction was prospectively predictive of more attenuated decreases in SAD symptoms. Body image dissatisfaction may have a causal link to SAD symptoms because social evaluative processes are inherent to body image dissatisfaction. According to sociocultural models, individuals realize discrepancies between their actual and ideal bodies via appearance-based comparisons with peers and media figures and considerations about how one’s body looks to others (Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 1999). Such social comparisons and body surveillance come to represent potent social evaluative threats and frequently elicit body dissatisfaction because sociocultural body ideals are nearly impossible to actualize (Aspen et al., 2013; Pallister & Waller, 2008; Stice, 2001). Notably, findings are consistent with hypotheses made by cognitive behavioral models that propose a link between body image dissatisfaction and anxiety symptoms. Specifically, body dissatisfaction is hypothesized to give rise to subsequent negative self-evaluations, cognitive biases, and safety behaviors that lead to and maintain anxiety (Aspen et al., 2013; Pallister & Waller, 2008). It is also possible that fears of negative evaluation, social appearance anxiety, and increased neuroendocrine sensitivity to appearance-based social evaluative threats also account for the prospective relationship between body image dissatisfaction and SAD symptoms (Levinson et al., 2013; Friederich et al., 2007; Lupis, Sabik, & Wolf, 2016; Menatti, DeBoer, Weeks, & Heimberg, 2015). Research is needed to evaluate these mechanisms in adolescents.

Among adolescents with subclinical anxiety symptoms only, those reporting higher body image dissatisfaction at baseline experienced greater increases in PD symptoms. In line with both sociocultural and cognitive behavioral models, individuals with severe body image disturbances report that perceived appearance-related social evaluations from others, body surveillance, and body checking behaviors serve as common triggers for PD symptoms (Phillips, Menard, & Bjornsson, 2013). As such, adolescents with poor body image satisfaction may perceive potential appearance-related social evaluations as threatening and engage in body vigilance more frequently (Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2012; Leahey, Crowther, & Ciesla, 2011), thereby increasing their panic-provoking triggers and subsequent risk for exacerbated PD symptoms. Upon exposure to appearance-related social evaluative threats, cognitive behavioral models suggest that it also is possible that adolescents with higher body image dissatisfaction have more cognitive biases that elicit or exacerbate PD symptoms, such as attention and memory biases for appearance-based imperfections/rejection and inaccurate perceptions of ambiguous social situations as threatening (Fang & Wilhelm, 2015; Rodgers & DuBois, 2016).

Adolescence may represent a high risk developmental period during which the relationship of body image dissatisfaction with SAD and PD symptoms is especially robust. A marked social re-orientation occurs during adolescence, as peer relationships become increasingly salient and emotionally charged (Nelson, Jarcho, & Guyer, 2016). Peer relationships among adolescents also are in constant flux and involve prominent social hierarchies, with their daily lives becoming entrenched with social comparisons (Nelson et al., 2016). In addition, social evaluative fears and peer rejection sensitivity increase sharply through adolescence (Nelson et al., 2016). As such, negative appearance-based social comparisons made by adolescents with body image dissatisfaction may be particularly provocative and more likely to elicit SAD and PD symptoms. Of note, the surge of gonadal steroid hormones during puberty exerts organizational effects on the regulation of neurotransmitter systems relevant for both body image dissatisfaction and anxiety (Klump, 2013; Nelson et al., 2016). It is possible that these post-pubertal organizational effects on brain structure and function may cause neural perturbations that enhance sensitivity to perceived appearance-related social evaluative threats and subsequently exacerbate SAD and PD symptoms.

Strengths and Limitations

The current study was novel in its investigation of body image dissatisfaction as a predictor of specific anxiety disorder symptom trajectories during adolescence, a high risk developmental period for the emergence of body image and anxiety problems. Additional study strengths include the prospective design and the inclusion of important covariates in analyses. However, the narrow age range (15–17 years) did not allow for the systematic examination of developmental differences. Despite the diverse racial/ethnic composition of the sample, the subsamples of non-White participants were too small to conduct meaningful multiple group analyses to evaluate racial/ethnic differences.

Although the self-report measures utilized were well validated, shared method variance may have influenced the findings because all constructs were self-reported. Adolescents’ self-report responses also may be subject to systematic reporting biases that could have impacted the findings, such as overweight adolescents under-reporting their weight, boys over-reporting their height, or adolescents not accurately reporting on their true anxiety or depressive symptoms. As such, replication is required using gold standard clinical interviews and body composition assessments. In addition, the body image measure broadly assessed the degree to which adolescents were dissatisfied with their general bodies, which was a study strength because the measure was applicable to adolescents of any sex or gender orientation. However, future studies would benefit from also including gender-specific body image dissatisfaction measures (e.g., focus on thinness for girls versus musculature for boys) that may capture unique associations between girls’ and boys’ body image dissatisfaction and anxiety trajectories.

Several aspects of the study design must be considered when making inferences about the study findings. It was not possible to examine non-linear slope trajectories without setting at least one parameter equal to zero because anxiety disorder symptoms were assessed at only three time points. In addition, body image dissatisfaction was assessed only at baseline and therefore it was not possible to examine bidirectional effects between body image dissatisfaction and anxiety disorder symptoms. An important direction for future research will be to distinguish the direction of this relationship. In light of the significant negative covariance between the intercept and slope factors scores for GAD, PD, SAD, and SSA symptoms, it is possible that findings may be partly attributed to the regression to the mean bias. Follow-up analyses excluding adolescents who met clinical cutoffs for any probable anxiety disorder revealed comparable findings to initial models, which bolsters confidence that regression to the mean was likely minimal. Although findings generalized to the subset of adolescents with subclinical anxiety disorder symptoms, the data did not afford the ability to evaluate the true onset of initial social anxiety disorder and panic disorder symptoms because the vast majority of participants (96%) reported at least some minimal anxiety disorder symptoms at baseline. Additional prospective studies in children and adolescents with minimal anxiety disorder symptoms at baseline are needed to examine whether body image dissatisfaction is a risk factor for the development of anxiety disorders.

Conclusions and Implications

In the present study, higher body image dissatisfaction was associated with higher concurrent symptoms of GAD, PD, SAD, and SSA, and was predictive of more attenuated decreases in SAD symptoms and greater increases PD symptoms over time in a community sample of adolescents. Prospective findings suggest that PD and SAD symptoms may be in part linked to body image dissatisfaction among adolescents, and therefore should be considered as a component of negative affect in sociocultural models of body image and disordered eating. It also may be worthwhile for sociocultural models to evaluate the validity of incorporating cognitive, behavioral, and neuroendocrine mechanisms that give rise to anxiety and other aspects of negative affect such as depression. To elucidate developmental theories of disordered eating and anxiety, comparable prospective studies are needed to examine the temporal relationship between other forms of eating disorder psychopathology and anxiety trajectories across the lifespan as well. Taken together, findings suggest that body image issues may be important to assess within the context of comorbid anxiety disorder symptoms. Assessing whether adolescents have higher levels of body image dissatisfaction also may be important when identifying which adolescents are at higher risk for exacerbated SAD and PD symptoms.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant K01-AA015059 (PI: Ohannessian). We would like to thank all of the adolescents who participated in this study. We would also like to acknowledge the Adolescent Adjustment Project staff for their unmatched dedication to the implementation and conduct of this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdollahi A, Abu Talib M, Mobarakeh M, Momtaz V, & Mobarake R (2015). Body-esteem mediates the relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety: The moderating roles of weight and gender. Child Care in Practice, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ER, & Mayes LC (2010). Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(3), 338–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspen V, Darcy AM, & Lock J (2013). A review of attention biases in women with eating disorders. Cognition and Emotion, 27(5), 820–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson MJ, & Wade TD (2015). Mindfulness‐based prevention for eating disorders: A school‐based cluster randomized controlled study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(7), 1024–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo-Baum K, & Knappe S (2012). Developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 21(3), 457–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Cully M, Brent D, & McKenzie S (1995). Screen for child anxiety related disorders (SCARED) Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Bully P, & Elosua P (2011). Changes in body dissatisfaction relative to gender and age: The modulating character of BMI. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 14(01), 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromley T, Knatz S, Rockwell R, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, & Boutelle K (2012). Relationships between body satisfaction and psychological functioning and weight-related cognitions and behaviors in overweight adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(6), 651–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Sáez S, Pascual A, Salaberria K, & Echeburúa E (2015). Normal-weight and overweight female adolescents with and without extreme weight-control behaviours: Emotional distress and body image concerns. Journal of Health Psychology, 20(6), 730–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vriendt T, Huybrechts I, Ottevaere C, Van Trimpont I, & De Henauw S (2009). Validity of self-reported weight and height of adolescents, its impact on classification into BMI-categories and the association with weighing behaviour. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 6(10), 2696–2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries DA, Peter J, de Graaf H, & Nikken P (2016). Adolescents’ social network site use, peer appearance-related feedback, and body dissatisfaction: Testing a mediation model. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(1), 211–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion J, Blackburn M-E, Auclair J, Laberge L, Veillette S, Gaudreault M, . . . Touchette, É (2015). Development and aetiology of body dissatisfaction in adolescent boys and girls. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 20(2), 151–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley B, Fitzgerald A, & Giollabhui N (2015). The risk and protective factors associated with depression and anxiety in a national sample of Irish adolescents. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 32(01), 93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Roscoät E, Legleye S, Guignard R, Husky M, & Beck F (2016). Risk factors for suicide attempts and hospitalizations in a sample of 39,542 French adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 517–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne A-P, Dion J, Lalande D, Bégin C, Émond C, Lalande G, & McDuff P (2016). Body dissatisfaction and psychological distress in adolescents: Is self-esteem a mediator? Journal of Health Psychology, [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang A, Sawyer AT, Aderka IM, & Hofmann SG (2013). Psychological treatment of social anxiety disorder improves body dysmorphic concerns. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(7), 684–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang A, & Wilhelm S (2015). Clinical features, cognitive biases, and treatment of body dysmorphic disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11, 187–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ, Munoz ME, Contreras S, & Velasquez K (2011). Mirror, mirror on the wall: peer competition, television influences, and body image dissatisfaction. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(5), 458. [Google Scholar]

- Field AE, Sonneville KR, Crosby RD, Swanson SA, Eddy KT, Camargo CA, . . . Micali, N(2014). Prospective associations of concerns about physique and the development of obesity, binge drinking, and drug use among adolescent boys and young adult men. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(1), 34–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Harney MB, Koehler LG, Danzi LE, Riddell MK, & Bardone-Cone AM (2012). Explaining the relation between thin ideal internalization and body dissatisfaction among college women: The roles of social comparison and body surveillance. Body Image, 9(1), 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederich H-C, Uher R, Brooks S, Giampietro V, Brammer M, Williams SC, . . . Campbell, IC(2007). I’m not as slim as that girl: Neural bases of body shape self-comparison to media images. Neuroimage, 37(2), 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gariepy G, Nitka D, & Schmitz N (2010). The association between obesity and anxiety disorders in the population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Obesity, 34(3), 407–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison CZ, Addy CL, Jackson KL, McKeown RE, & Waller JL (1991). The CES-D as a screen for depression and other psychiatric disorders in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(4), 636–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale WW, Raaijmakers Q, Muris P, & Meeus W (2008). Developmental trajectories of adolescent anxiety disorder symptoms: A 5-year prospective community study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(5), 556–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S (2012). Self-perception profile for adolescents: Manual and questionnaires. Denver, CO: Univeristy of Denver, Department of Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes EK, & Gullone E (2011). Emotion regulation moderates relationships between body image concerns and psychological symptomatology. Body image, 8(3), 224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivarsson T, Svalander P, Litlere O, & Nevonen L (2006). Weight concerns, body image, depression and anxiety in Swedish adolescents. Eating Behaviors, 7(2), 161–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Compton SN, Walkup JT, Birmaher B, Albano AM, Sherrill J, . . . Gosch E(2010). Clinical characteristics of anxiety disordered youth. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24(3), 360–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber M, Couturier J, Georgiades K, Wahoush O, & Jack SM (2015). Ethnic minority status and body image dissatisfaction: A scoping review of the child and adolescent literature. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17(5), 1567–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL (2013). Puberty as a critical risk period for eating disorders: A review of human and animal studies. Hormones and Behavior, 64(2), 399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koronczai B, Kökönyei G, Urbán R, Kun B, Pápay O, Nagygyörgy K, . . . Demetrovics Z(2013). The mediating effect of self-esteem, depression and anxiety between satisfaction with body appearance and problematic internet use. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 39(4), 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, . . . Johnson CL (2002). 2000. CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and development . Vital and Health Statistics. Series 11, Data from the National Health Survey, 246, 1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahey TM, Crowther JH, & Ciesla JA (2011). An ecological momentary assessment of the effects of weight and shape social comparisons on women with eating pathology, high body dissatisfaction, and low body dissatisfaction. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 197–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A (2015). Teens, social media, and technology overview: 2015. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson CA, Rodebaugh TL, White EK, Menatti AR, Weeks JW, Iacovino JM, & Warren CS (2013). Social appearance anxiety, perfectionism, and fear of negative evaluation. Distinct or shared risk factors for social anxiety and eating disorders? Appetite, 67, 125–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupis SB, Sabik NJ, & Wolf JM (2016). Role of shame and body esteem in cortisol stress responses. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39(2), 262–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean SA, Paxton SJ, Wertheim EH, & Masters J (2015). Photoshopping the selfie: Self photo editing and photo investment are associated with body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(8), 1132–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean SA, Wertheim EH, Marques MD, & Paxton SJ (2016). Dismantling prevention: Comparison of outcomes following media literacy and appearance comparison modules in a randomised controlled trial. Journal of Health Psychology, [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menatti AR, DeBoer LBH, Weeks JW, & Heimberg RG (2015). Social anxiety and associations with eating psychopathology: Mediating effects of fears of evaluation. Body Image, 14, 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J. p., Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, . . . Swendsen J(2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Domínguez S, Rodríguez-Ruiz S, Fernández-Santaella MC, Jansen A, & Tuschen-Caffier B (2012). Pure versus guided mirror exposure to reduce body dissatisfaction: A preliminary study with university women. Body Image, 9(2), 285–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach H, Ollendick T, King N, & Bogie N (2002). Three traditional and three new childhood anxiety questionnaires: Their reliability and validity in a normal adolescent sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(7), 753–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, & Muthen BO (1998-2015). Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen. [Google Scholar]

- Myers TA, & Crowther JH (2009). Social comparison as a predictor of body dissatisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(4), 683–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelemans SA, Hale WW, Branje SJ, Raaijmakers QA, Frijns T, van Lier PA, & Meeus WH (2014). Heterogeneity in development of adolescent anxiety disorder symptoms in an 8-year longitudinal community study. Development and Psychopathology, 26(01), 181–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EE, Jarcho JM, & Guyer AE (2016). Social re-orientation and brain development: An expanded and updated view. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 17, 118–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Lerner RM, Lerner JV, & von Eye A (1999). Does self-competence predict gender differences in adolescent depression and anxiety? Journal of Adolescence, 22(3), 397–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Milan S, & Vannucci A (2017). Gender differences in anxiety trajectories from middle to late adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(4), 826–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, & Seeley JR (2010). Latent trajectory classes of depressive and anxiety disorders from adolescence to adulthood: Descriptions of classes and associations with risk factors. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 51(3), 224–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallister E, & Waller G (2008). Anxiety in the eating disorders: Understanding the overlap. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(3), 366–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton SJ, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, & Eisenberg ME (2006). Body dissatisfaction prospectively predicts depressive mood and low self-esteem in adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(4), 539–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegrini A, Coqueiro R.d. S. , Beck CC, Ghedin KD, Lopes A. d. S., & Petroski EL (2014). Dissatisfaction with body image among adolescent students: Association with socio-demographic factors and nutritional status. Ciência y Saúde Coletiva, 19(4), 1201–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Menard W, & Bjornsson AS (2013). Cued panic attacks in body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 19(3), 194–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers RF, & DuBois RH (2016). Cognitive biases to appearance-related stimuli in body dissatisfaction: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 46, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, & Rudolph KD (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 98–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville LH, & Casey B (2010). Developmental neurobiology of cognitive control and motivational systems. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 20(2), 236–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E (2001). A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology: Mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(1), 124–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(5), 825–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti CN, Spoor S, Presnell K, & Shaw H (2008). Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: Long-term effects from a randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 329–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, & Shaw HE (2002). Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: A synthesis of research findings. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(5), 985–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JK, Heinberg LJ, Altabe M, & Tantleff-Dunn S (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Touchette E, Henegar A, Godart NT, Pryor L, Falissard B, Tremblay RE, & Côté SM (2011). Subclinical eating disorders and their comorbidity with mood and anxiety disorders in adolescent girls. Psychiatry Research, 185(1), 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weems CF (2008). Developmental trajectories of childhood anxiety: Identifying continuity and change in anxious emotion. Developmental Review, 28(4), 488–502. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Orvaschel H, & Padian N (1980). Children’s symptom and social functioning self-report scales comparison of mothers’ and children’s reports. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 168(12), 736–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama K, Lee TK, O’Neail CW, & Lorenz FO (2016). Higher-Order Growth Curves and Mixture Modeling with Mplus. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wilksch SM, & Wade TD (2009). Reduction of shape and weight concern in young adolescents: A 30-month controlled evaluation of a media literacy program. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(6), 652–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilksch SM, & Wade TD (2014). Depression as a moderator of benefit from Media Smart: A school-based eating disorder prevention program. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 52, 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wothke W (2000). Longitudinal and multigroup modeling with missing data. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]