Abstract

Purpose: Age at diagnosis has been identified as a major determinant of thyroid cancer-specific survival. But the cut-off value for age was controversial. The interaction among gender, age and histologic subtypes needed to be answered.

Methods: We identified 59,892 thyroid cancer (TC) patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. We divided the patients into the following three groups according to age: 20-44 years (young), 45-64 years (middle-aged), and ≥ 65 years (elderly). Logistic regression model was used to identify factors relating to prognosis in elderly patients. Multivariable Cox regression model identified potential prognostic factors. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results: Elderly patients had significantly worse prognosis than the other two groups, P=0.001. Elderly patients had higher proportion of male gender, advanced tumor grade, follicular subtype and advanced tumor stage. There was no survival difference for elderly patients to receive lobectomy and total thyroidectomy, P=0.852. Cox proportional hazards regression model showed that gender, marital status, histology, tumor grade, tumor size, TNM stage, surgery and radiotherapy were all independent prognostic factors in the multivariable analysis. Male patients with TC had worse prognosis than their female counterparts in differentiated tumor but not in undifferentiated tumor. There were more patients of larger tumor, advanced TNM stage and histologic subtypes in male patients.

Conclusions: In conclusion, there were a series of factors contributing to the poor prognosis in elderly patients including clinic-pathologic factors and therapy selection. There was no survival difference for elderly patients to receive lobectomy and total thyroidectomy.

Keywords: Clinic-pathologic Features, Elder, Prognosis, SEER, Thyroid cancer

Introduction

Thyroid cancer (TC) is the most common endocrine malignancy, with an estimated 56,870 new cases in the United States in 2017 1. The long-term prognosis for TC patients is generally excellent with appropriate treatment 2. The mainstay treatment for TC patients is still surgical resection, with or without adjuvant radioactive iodine therapy. Histologic subtype has been proved to be prognostic factor 3, 4. Papillary thyroid cancer accounts for more than 90% of all cases and has good prognostic 5, 6. Thyroid cancer are reported to be female predominant while male patients have more aggressive behaviors and worse prognosis compared with female 7.

Age at diagnosis has been identified as a major determinant of thyroid cancer-specific survival 8. Patients older than 45 years of age are generally considered to have poor prognosis 5, 9, 10. With advancing age, a higher-risk histological phenotype is more likely 11. Older age at diagnosis was independent risk factors of disease-specific mortality of TC patients 12. How to define older patients remains a question. Most studies used 45-year old as a cutoff value 9, 10, 12. However, patients around 45-year old cannot be recognized as elderly. Some other studies used 65 years 13 or 60 years14. Little is known about the clinic-pathologic and prognostic factors in elder patients. Interaction between gender and histologic subtypes in elderly patients needs further study.

In this study, we will use the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database to analyze the effect of age on prognosis and the clinic-pathologic features of elderly patients.

Materials and Methods

Database

This study is a retrospective cohort review using the largest publicly available dataset on human cancer - the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. This database contains information collected from different cancer registries of 18 geographic regions across the U.S. Together, these regions currently represent approximately 27.8% of the total U.S. population. The particular database from which we identified patients for analysis was “Incidence-SEER 18 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2015 Sub (1973-2013 varying)”, from the SEER Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) Research Data (1973-2013), sponsored and maintained by the National Cancer Institute, the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences (DCCPS), Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch, and released April 2016.

Outcome variables

TC patients were selected based on histology type according to the histology codes in the International Classification of Disease for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-0-3) SEER site/histology validation list 2015. Specifically, TC patients were identified using the following ICD-0-3 codes: Classic Papillary Thyroid Cancer (C-PTC): 8050/3, 8260/3, and 8343/3; Variant Papillary Thyroid Cancer (V-PTC): 8340/3, 8350/3, 8344/3, 8052/3, 8130/3, and 8342/3; FTC (Follicular Thyroid Cancer): 8330/3, 8331/3, 8332/3, and 8335/3; MTC (Medullary Thyroid Cancer): 8345/3, 8510/3, 8346/3, and 8347/3; and ATC (Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer): 8021/3. C-PTC, V-PTC, and FTC were classified as differentiated thyroid cancer. While MTC and ATV were recognized as undifferentiated thyroid cancer. Patients with other histology types in the database were excluded from our study cohort.

For insurance status, individuals in the “Any Medicaid”, “Insured” or “Insured/No specifics” groups were clustered together as the “Insured” group; for marital status, the “Separated” and “Divorced” groups were combined to form the “Separated/Divorced” group, and the “Single” and “Unmarried or Domestic Partner” groups were combined to form the “Single” group; for cancer-directed surgery status, the “Subtotal or Near Total Thyroidectomy” and “Total Thyroidectomy” groups were combined to form the “Total Thyroidectomy” group. The “Lobectomy” group consisted of TC patients who underwent lobectomy, with or without subsequent isthmusectomy. If a patient initially underwent a thyroid lobectomy and then went on to have a completion thyroidectomy, his/her surgery status in SEER was coded as “Total Thyroidectomy” 1. Patients who had less than one lobe removed, or who were classified under “Thyroidectomy, Not Otherwise Specified (NOS)” or “Surgery, NOS”, were excluded from our analysis.

Patient Population

Among subjects in the dataset, those eligible to our study were thyroid cancer (TC) patients who met the following criteria: 1) were diagnosed with TC from 2004 to 2013, 2) were aged 20 years or older at the time of diagnosis, 3) had TC as their only known malignancy throughout this period. Cases that were diagnosed clinically only, via autopsy only, or via radiography without microscopic confirmation were excluded from our study cohort. Based on these criteria, our study cohort consisted of a total of 59,892 TC patients.

Clinic-pathological variables of interest pertaining to patient demographics or disease status were extracted from the SEER database. Demographic variables obtained included patient age as recorded at the time of TC diagnosis, gender, marital status, ethnicity, insurance status, survival time (since TC diagnosis until disease-specific death as of December 31, 2013, in months), and disease-specific survival (DSS) status; clinical data obtained included status of cancer-directed surgery (no surgery, lobectomy, or thyroidectomy), and status of radiotherapy (yes or no); pathological characteristics obtained included histological subtype, grade of disease, tumor size, tumor stage as classified according to the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual (6th edition, 2004), and status of lymph nodes resection (yes or no).

Statistical Methods

The patients' demographic and tumor characteristics were summarized with descriptive statistics. Comparisons of categorical variables among different groups of patients were performed using the Chi square test, and continuous variables were compared using Student's t test. The primary endpoint of this study was cause specific-survival (CSS), which was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of cancer specific death. Deaths attributed to pancreatic cancer were treated as events and deaths from other causes were considered as censored observations. Survival function estimation and comparison among different variables were performed using Kaplan-Meier estimates and the log-rank test. The multivariate Cox proportional hazard model was used to evaluate the hazard ratio (HR) and the 95 % confidence interval (CI) for all the known prognostic factors. We used log-rank test to analyze the potential relating factors to no microscopic confirmation. All of statistical analyses were performed using the Intercooled Stata 13.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Statistical significance was set at two-sided P < 0.05.

Ethnic issues

This study was deemed exempt from institutional review board approval by The First Affiliated Hospital, China Medical University; informed consent was waived.

Results

Patient demographics

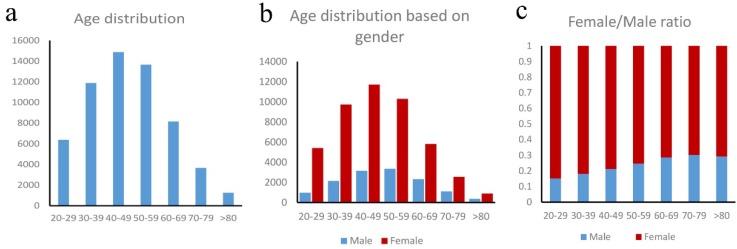

Our study consisted of 59,892 TC patients, with a median (range) age of 47 years (20 - 101 years). Based on the age distribution of these patients (Figure 1a), the peak incidence occurred in the 40-49 and 50-59 years old, which, together, accounted for 47.7% of all the patients. For females, the peak TC incidence occurred in the 40-49 age group, which accounted for 25.2% of all the female patients. For males, the peak TC incidence occurred in the 50-59 age group, which accounted for 25.0% of all the male patients (Figure 1b). In our entire study cohort, the female-to-male ratio is 3.46:1, indicating that thyroid cancer occurred more frequently in women than in men. Furthermore, there is a steady decrease in the proportion of female-to-male ratio (Figure 1c) which indicating the increasing of male and decreasing of female with advancing age. For the 20-29 age group, the female-to-male ratio was 5.58:1; and it was 3.08:1 for the 50-59 age group, 2.30:1 for patients older than 60 years.

Figure 1.

a. Age distribution in thyroid cancer patients, b. Age distribution based on gender, c. Female/male ratio in thyroid cancer patients.

We divided the patients into the following three groups according to age: 20-44 years (N= 25,520, 42.6%), 45-64 years (N = 25,925, 43.3%), and ≥ 65 years (N = 8,447, 14.1%), henceforth referred to as the young, middle-aged, and the elderly group, respectively. The clinic-pathologic characteristics of the young, middle-aged, and elderly TC patients were summarized in Table 1. The three age groups displayed significant differences with respect to gender distribution, marital status, ethnicity, insurance status, histology subgroup, tumour size, differentiation grade, invasion depth (T stage), lymph nodes (N stage), status of metastasis, AJCC 6th TNM stage, treatment with surgery, radiotherapy, and lymph nodes resection.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinic-pathological characteristics among the young, middle-aged, and elderly thyroid cancer patients

| Factors | 20 - 44 years old N (%) |

45 - 64 years old N (%) |

> 65 years old N (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 20,908 (81.9) | 19,547 (75.4) | 6,009 (71.1) | |

| Males | 4,612 (18.1) | 6,378 (24.6) | 2,438 (28.9) | < 0.001 |

| Married status | ||||

| Married | 15,226 (62.6) | 17,779 (72) | 4,819 (60.1) | |

| Widowed | 106 (0.4) | 710 (2.9) | 1,766 (22.0) | |

| Separated or divorced | 1,361 (5.6) | 2,494 (10.1) | 756 (9.4) | |

| Single or unmarried | 7,627 (31.4) | 3,695 (15.0) | 682 (8.5) | < 0.001 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 20,448 (81.4) | 20,911 (81.6) | 6,772 (81.0) | |

| African-American | 1,381 (5.5) | 1,584 (6.2) | 469 (5.6) | |

| Other | 3,299 (13.1) | 3,121 (12.2) | 1,124 (13.4) | < 0.001 |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Uninsured | 994 (5.2) | 1,029 (5.1) | 173 (2.6) | |

| Insured | 18,065 (94.8) | 19,106 (94.9) | 6,499 (97.4) | < 0.001 |

| Histology subgroup | ||||

| C-PTC | 16,997 (66.6) | 15,580 (60.1) | 4,654 (55.1) | |

| V-PCT | 6,818 (26.7) | 8,294 (32.0) | 2,603 (30.8) | |

| FCT | 1,360 (5.3) | 1,406 (5.4) | 679 (8.0) | |

| MTC | 336 (1.3) | 504 (1.9) | 271 (3.2) | |

| ATC | 9 (0.0) | 141(0.5) | 240 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| Grade | ||||

| Well differentiated | 4,478 (81.1) | 4,169 (76.8) | 1,121 (57.8) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 882 (16.0) | 862 (15.9) | 341 (17.6) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 132 (2.4) | 188 (3.5) | 151(7.8) | |

| Undifferentiated | 27 (0.5) | 209 (3.9) | 328 (16.9) | <0.001 |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||

| < 1.0 | 7,373 (30.1) | 9,848 (39.7) | 2,746 (35.2) | |

| 1.1 - 2.0 | 7,890 (32.2) | 7,305 (29.5) | 1,950 (25.0) | |

| 2.1 - 4.0 | 6,836 (27.9) | 5,484 (22.1) | 1,865 (23.9) | |

| > 4.0 | 2,427 (9.9) | 2,162 (8.7) | 1,246 (16.0) | < 0.001 |

| Surgery | ||||

| No surgery | 391 (1.6) | 555 (2.2) | 563 (6.8) | |

| Lobectomy | 2,572 (10.2) | 3,099 (12.1) | 1,152 (14.0) | |

| Total thyroidectomy | 22,209 (88.2) | 21,895 (85.7) | 6,533 (79.2) | < 0.001 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 14,344 (56.5) | 13,312 (51.6) | 3,841 (45.8) | |

| No | 11,044 (43.5) | 12,489 (48.4) | 4,553 (54.2) | < 0.001 |

|

Lymph nodes resection |

||||

| No | 10,786 (42.5) | 13,306 (51.5) | 5,035 (59.9) | |

| Yes | 14,617 (57.5) | 12,532 (48.5) | 3,370 (40.1) | < 0.001 |

| AJCC 6th T stage | ||||

| T0 | 34 (0.1) | 44 (0.2) | 29 (0.4) | |

| T1/T2 | 18,933 (76.6) | 19,186 (76.4) | 5,207 (65.2) | |

| T3/T4 | 5,755 (23.3) | 5,895 (23.5) | 2,749 (34.4) | < 0.001 |

| AJCC 6th N stage | ||||

| N0 | 17,368 (72.5) | 20,162 (81.3) | 6,433 (81.7) | |

| N1 | 6,600 (27.5) | 4,646 (18.7) | 1,445 (18.3) | < 0.001 |

| Distant metastasis | ||||

| No | 24,848 (99.2) | 25,011 (98.3) | 7,731 (93.8) | |

| Yes | 191 (0.8) | 431 (1.7) | 507 (6.2) | < 0.001 |

| AJCC 6th TNM stage | ||||

| I | 24,624 (98.4) | 13,037 (53.4) | 3,629 (46.1) | |

| II | 244 (1.0) | 3,297 (13.5) | 964 (12.2) | |

| III | 30 (0.1) | 5,249 (21.5) | 1,587 (20.1) | |

| IV | 129 (0.5) | 2,812 (11.5) | 1,698 (21.6) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer, TNM tumor-node-metastasis, C-PTC Classic Papillary Thyroid Cancer, VPTC Variant Papillary Thyroid Cancer, FTC, follicular thyroid cancer, MTC Medullary thyroid cancer, ATC Anaplastic thyroid cancer.

There were 2,438 (28.9%) male patients in the elderly groups, higher than that in the young and middle-aged groups. More elderly patients were covered by insurance. For the histologic subtypes, elderly patients had more undifferentiated and poorly differentiated thyroid cancer. As for the tumor size, elderly patients had more tumors >4cm. For treatment, fewer elderly patients receive total thyroidectomy or radiotherapy. Elderly patients had higher proportion of T3/4 disease and more metastasis diseases compared with the other two groups of patients.

To better understand the difference between male and female in the elderly patients, we compared the clinic-pathologic characteristics between females and males, which was summarized in Table 2. More male patients were married and Caucasian. Male patients had higher percentage of undifferentiated tumor. Female patients had smaller tumor size and earlier TNM stage than male patients.

Table 2.

Comparison of clinic-pathological characteristics between female and male elderly thyroid cancer patients from the SEER database.

| Factors | Female N (%) |

Male N (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Married status | |||

| Married | 3,005 (52.7) | 1,814 (78.1) | |

| Widowed | 1,577 (27.7) | 189 (8.1) | |

| Separated or divorced | 610 (10.7) | 146 (6.3) | |

| Single or unmarried | 509 (8.9) | 173 (7.5) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 4,746 (79.7) | 2,026 (84.0) | |

| African-American | 368 (6.2) | 101 (4.2) | |

| Other | 840 (14.1) | 284 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| Insurance status | |||

| Uninsured | 125 (2.6) | 48 (2.5) | |

| Insured | 4,640 (97.4) | 1,859 (97.5) | 0.805 |

| Histology subgroup | |||

| C-PTC | 3,314 (55.2) | 1,340 (55.0) | |

| V-PCT | 1,930 (32.1) | 673 (27.6) | |

| FCT | 454 (7.6) | 225 (9.2) | |

| MTC | 153 (2.5) | 118 (4.8) | |

| ATC | 158 (2.6) | 82 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| Grade | |||

| Well differentiated | 810 (59.6) | 311 (53.4) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 244 (18.0) | 97 (16.7) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 91 (6.7) | 60 (10.3) | |

| Undifferentiated | 214 (15.7) | 114 (19.6) | 0.004 |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||

| < 1.0 | 2,135 (38.1) | 611 (27.7) | |

| 1.1 - 2.0 | 1,466 (26.2) | 484 (21.9) | |

| 2.1 - 4.0 | 1275 (22.8) | 590 (26.7) | |

| > 4.0 | 725 (12.9) | 521 (23.6) | <0.001 |

| Surgery | |||

| No surgery | 357 (6.1) | 206 (8.7) | |

| Lobectomy | 838 (14.3) | 314 (13.2) | <0.001 |

| Total thyroidectomy | 4,677 (79.6) | 1,856 (78.1) | |

| Radiotherapy | |||

| Yes | 2,596 (43.5) | 1,245 (51.3) | |

| No | 3,372 (56.5) | 1,181 (48.7) | <0.001 |

| Lymph nodes resection | |||

| Yes | 2,339 (39.1) | 1,031 (42.5) | |

| No | 3,641 (60.9) | 1,394 (57.5) | 0.004 |

| AJCC 6th T stage | |||

| T0 | 15 (0.3) | 14 (0.6) | |

| T1/T2 | 3,904 (68.5) | 1,303 (57.1) | |

| T3/T4 | 1,783 (31.3) | 966 (42.3) | <0.001 |

| AJCC 6th N stage | |||

| No | 4,823 (85.3) | 1,610 (72.4) | |

| Yes | 831 (14.7) | 614 (27.6) | <0.001 |

| Distant metastasis | |||

| No | 5,585 (95.2) | 2,146 (90.4) | |

| Yes | 279 (4.8) | 228 (9.6) | <0.001 |

| AJCC 6th TNM stage | |||

| I | 2,850 (50.7) | 779 (34.5) | |

| II | 682 (12.1) | 282 (12.5) | |

| III | 1,086 (19.3) | 501 (22.2) | |

| IV | 999 (17.8) | 699 (30.9) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer, TNM tumor-node-metastasis, C-PTC Classic Papillary Thyroid Cancer, VPTC Variant Papillary Thyroid Cancer, FTC, follicular thyroid c

Survival differences

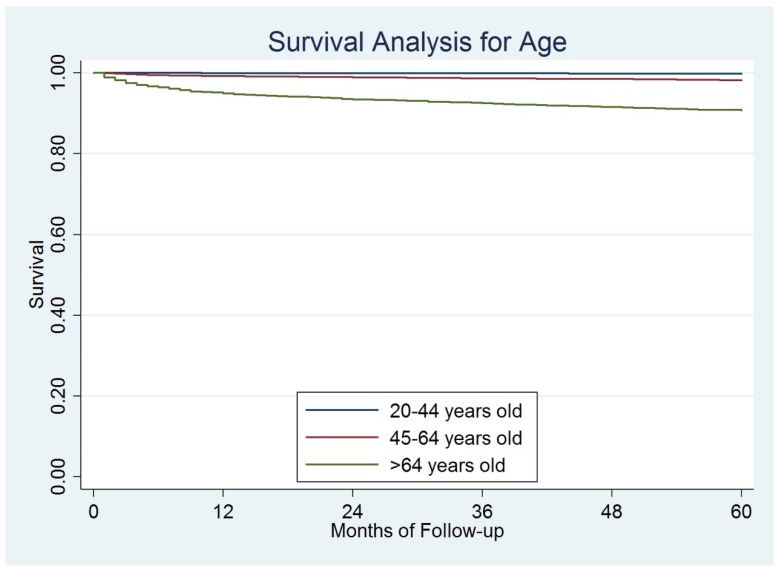

The median follow-up for the entire cohort was 47 months (range 1-119 months). Till December 31, 2013, a total of 1,171 (2.0%) disease-specific deaths were observed. The overall 5-year DSS rate was 97.8%. Based on the results from the log-rank test, elderly patients had significantly worse prognosis than the other two groups of patients. The 5-year DSS was 99.8%, 98.3%, and 90.8% for young, middle-aged, and elderly patients, respectively, P=0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The survival difference among different ages.

To better understand the prognostic factors for elderly patients, we focus on the elderly patients for survival analysis. Based on the univariate analysis, variables that were determined to be significantly associated with a lower 5-year DSS rate included male (P<0.001), being widowed (P<0.001), MTC and ATC (P<0.001), undifferentiated tumor (P<0.001), tumor size > 4.0 cm (P<0.001), T3/4 (P<0.001), lymph nodes metastasis (P<0.001), presence of distant metastasis (P<0.001), higher TNM stage (P<0.001), without surgery (P<0.001), no radiotherapy (P<0.001), and no lymph nodes resection (P<0.001). Ethnicity and insurance status were not significantly correlated with survival.

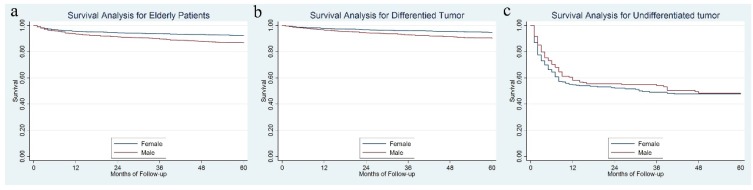

Female patients had a significantly better 5-year DSS than male, 92.3% vs. 86.6%, P = 0.001 (Figure 3a). Further analysis showed that for differentiated tumor, a significant survival difference was observed between gender (94.6% for females vs. 90.0% for males, P < 0.001) (Figure 3b), while for patients with an undifferentiated tumor, the 5-year DSS rate was not significantly different between females and males, 47.6% for females vs. 47.8% for males, P = 0.363 (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

The survival difference between female and male in the whole cohort (3a), in the differentiated tumor (3b) and undifferentiated tumor (3b).

Multivariate analysis

Variables showing a trend for association with survival (P < 0.05) were included in the Cox proportional hazards regression model. Gender, marital status, histology, tumor grade, tumor size, TNM stage, surgery and radiotherapy were all independent prognostic factors in the multivariable analysis (Table 3). There was no survival difference for elderly patients to receive lobectomy and total thyroidectomy, P=0.852. Compared for female patients, the hazard ratio for male patients was 1.77, P<0.001.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of survival

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Male | 1.77 | 1.52 - 2.06 | < 0.001 |

| Married status | |||

| Married | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Widowed | 1.72 | 1.45 - 2.05 | < 0.001 |

| Separated or divorced | 1.04 | 0.79 - 1.30 | 0.778 |

| Single or unmarried | 1.15 | 0.90 - 1.46 | 0.875 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 1.00 | Reference | |

| African-American | 0.73 | 0.50 - 1.07 | 0.110 |

| Other | 1.20 | 0.97 - 1.47 | 0.091 |

| Histology subgroup | |||

| C-PTC | 1.00 | Reference | |

| V-PTC | 0.56 | 0.44 - 0.71 | < 0.001 |

| FTC | 1.39 | 1.05 - 1.83 | 0.021 |

| MTC | 2.87 | 2.10 - 3.91 | < 0.001 |

| ATC | 41.57 | 34.27 - 50.44 | < 0.001 |

| Grade | |||

| Well differentiated | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Moderately differentiated | 2.77 | 1.42 - 5.38 | 0.003 |

| Poorly differentiated | 25.30 | 15.07 - 42.47 | < 0.001 |

| Undifferentiated | 120.98 | 75.56 - 193.68 | < 0.001 |

| Tumor size(cm) | |||

| < 1.0 | 1.00 | Reference | |

| 1.1 - 2.0 | 2.70 | 1.71 - 4.26 | < 0.001 |

| 2.1 - 4.0 | 8.79 | 5.89 - 13.13 | < 0.001 |

| > 4.0 | 25.86 | 17.53 - 38.13 | < 0.001 |

| Surgery | |||

| No surgery | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Lobectomy | 0.07 | 0.05 - 0.09 | < 0.001 |

| Total thyroidectomy | 0.08 | 0.07 - 0.10 | < 0.001 |

| Radiotherapy | |||

| Yes | 1.00 | Reference | |

| No | 0.67 | 0.58 - 0.78 | < 0.001 |

| Lymph nodes resection | |||

| Yes | 1.00 | Reference | |

| No | 0.90 | 0.77 - 1.05 | 0.166 |

| AJCC 6th TNM stage | |||

| I | 1.00 | Reference | |

| II | 2.73 | 1.29 - 5.76 | < 0.001 |

| III | 5.32 | 2.96 - 9.56 | < 0.001 |

| IV | 100.87 | 61.38 - 165.77 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: HR: Hazard ratio, CI: Confident Index, AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer, TNM: tumor-node-metastasis, C-PTC: Classic Papillary Thyroid Cancer, VPTC: Variant Papillary Thyroid Cancer, FTC: Follicular thyroid cancer, MTC: Medullary thyroid cancer, ATC: Anaplastic thyroid cancer.

Discussion

Thyroid cancer has been established to have an obvious female predominance 7, 15. In our present study, we also found that female/male ratio was larger than 1 in all the age groups, especially in the young patients. The underlying mechanism for female predominance in TC was still unknown. Some studies showed that estrogens may play a role in favoring the malignant progression of thyroid tissue to cancer 15, 16. Our study further found that there was a steady decreasing in the proportion of female in the TC patients as the age increasing. For the elderly patients, the female/male ratio was only 2.46. This finding supported the theory that sex hormone was important in gender imbalance of TC patients.

Age at diagnosis has long been identified as an established prognostic factor for TC patients 8, 17. The cutoff value for age to predict prognosis has been controversial 9-14. In our present study, we applied two most common used cut-off value: 45 years and 65 years old to divide patients into 3 groups: 20-44 years, 45-64 years, and ≥ 65 years. We found that patients older than 65 years old (elderly patients) had significantly worse prognosis than the other two groups. To better understand the potential reasons for the survival difference among ages. We compared the clinic-pathologic features among these three groups of patients and found that elderly patients had higher proportion of male gender, advanced tumor grade, follicular subtype and advanced tumor stage (Summary Stage and AJCC 6th Stage). These factors were all proved to be independent risk factors for prognosis in both univariate analysis and multivariable analysis which were consistent with previous reports 14, 17. Shah S et al. found that there was a significantly larger percentage of excellent responders among young patients (age <55) than among old patients (age ≥ 55) 8. Some other studies showed that age was a strong, continuous, and independent mortality risk factor in patients with BRAF V600E mutation but not in patients with wild-type BRAF 13, 17.

In our study, we found that age was a major determinant of therapy choice. Fewer elderly patients received surgery or radiotherapy which may also explain the poor prognosis in elderly patients. Moreover we found there was no survival difference for elderly patients to receive lobectomy and total thyroidectomy. There was report showing that survival was similar for total thyroidectomy compared with lobectomy across patients younger than 45 years old with tumors of 1.1 to 4.0 cm 9. Mendelsohn AH et al. showed that controlling for tumor size, multivariate analysis revealed no survival difference between patients who had undergone total thyroidectomy and those who had undergone lobectomy 18. Based on the literature and our finding, there is no need to carry out total thyroidectomy in elderly patients.

We found that male patients with TC had worse prognosis than their female counterparts, which was consistent with previous studies 7, 19, 20. Our further analysis showed that tumor sizes of our male patients were larger than that of female patients. There were more patients of advanced TNM stage and histologic subtypes in male patients, suggested the more aggressive behaviours in male patients with TC. Furthermore, we analysed the survival disparity between female and male according to the histologic subtype and we found that significant survival difference was observed between genders in differentiated tumor while not in undifferentiated tumor. More and more studies showed that undifferentiated TC possessed heterogeneous and unique profiles and there was a need to reveal the significance of detailed molecular profiling of this disease 21, 22.

Potential limitations of our study should be taken into consideration. Firstly, there may be some other factors that contribute to the survival disparity among different ages, such as chemotherapy. However, data related to chemotherapy are not available in SEER database. Secondly, Detail information about radiotherapy and co-morbidities are not available in the SEER database, moreover, information of screen is also not available in the SEER database. Finally, this was a retrospective study.

In conclusion, there were a series of factors contributing to the poor prognosis in elderly patients including clinic-pathologic factors and therapy selection. There was no survival difference for elderly patients to receive lobectomy and total thyroidectomy. It is worthwhile to confirm the value of lobectomy in elderly patients in prospective clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank those who have been involved with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, including the staff members of the National Cancer Institute, and the Information Management Services, Inc.

Dr. Haiyan Zhang is an Irma and Paul Milstein Program for Senior Health fellow supported by the MMAAP Foundation (http://www.mmaapf.org)

Funding

This work was supported by the Milstein Medical Asian American Partnership (MMAAP) Foundation (http://www.mmaapf.org) grant to Dr. Sean X. Leng.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies L, Welch HG. Thyroid cancer survival in the United States: observational data from 1973 to 2005. Archives of otolaryngology-head & neck surgery. 2010;136:440–4. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carling T, Ocal IT, Udelsman R. Special variants of differentiated thyroid cancer: does it alter the extent of surgery versus well-differentiated thyroid cancer? World journal of surgery. 2007;31:916–23. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0837-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazaure HS, Roman SA, Sosa JA. Aggressive variants of papillary thyroid cancer: incidence, characteristics and predictors of survival among 43,738 patients. Annals of surgical oncology. 2012;19:1874–80. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tubiana M, Schlumberger M, Rougier P, Laplanche A, Benhamou E, Gardet P. et al. Long-term results and prognostic factors in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Cancer. 1985;55:794–804. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850215)55:4<794::aid-cncr2820550418>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang L, Zheng RS, Wang N, Zeng HM, Yuan YN, Zhang SW. et al. [Analysis of Incidence and Mortality of Thyroid Cancer in China, 2013] Zhonghua zhong liu za zhi [Chinese journal of oncology] 2017;39:862–7. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3766.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan HX, Pang P, Wang FL, Tian W, Luo YK, Huang W. et al. Dynamic profile of differentiated thyroid cancer in male and female patients with thyroidectomy during 2000-2013 in China: a retrospective study. Scientific reports. 2017;7:15832. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14963-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah S, Boucai L. Effect of Age on Response to Therapy and Mortality in Patients with Thyroid Cancer at High-Risk of Recurrence. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism; 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adam MA, Pura J, Goffredo P, Dinan MA, Hyslop T, Reed SD. et al. Impact of extent of surgery on survival for papillary thyroid cancer patients younger than 45 years. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2015;100:115–21. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verburg FA, Mader U, Tanase K, Thies ED, Diessl S, Buck AK. et al. Life expectancy is reduced in differentiated thyroid cancer patients >/= 45 years old with extensive local tumor invasion, lateral lymph node, or distant metastases at diagnosis and normal in all other DTC patients. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;98:172–80. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwong N, Medici M, Angell TE, Liu X, Marqusee E, Cibas ES. et al. The Influence of Patient Age on Thyroid Nodule Formation, Multinodularity, and Thyroid Cancer Risk. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2015;100:4434–40. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeon MJ, Kim WG. Disease-Specific Mortality of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Patients in Korea: A Multicenter Cohort Study. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Howell GM, Carty SE, Armstrong MJ, Lebeau SO, Hodak SP, Coyne C. et al. Both BRAF V600E mutation and older age (>/= 65 years) are associated with recurrent papillary thyroid cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2011;18:3566–71. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pitoia F, Jerkovich F, Smulever A, Brenta G, Bueno F, Cross G. Should Age at Diagnosis Be Included as an Additional Variable in the Risk of Recurrence Classification System in Patients with Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. European thyroid journal. 2017;6:160–6. doi: 10.1159/000453450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zane M, Parello C, Pennelli G, Townsend DM, Merigliano S, Boscaro M. et al. Estrogen and thyroid cancer is a stem affair: A preliminary study. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2017;85:399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derwahl M, Nicula D. Estrogen and its role in thyroid cancer. Endocrine-related cancer. 2014;21:T273–83. doi: 10.1530/ERC-14-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen X, Zhu G, Liu R, Viola D, Elisei R, Puxeddu E, Patient Age-Associated Mortality Risk Is Differentiated by BRAF V600E Status in Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2017. Jco2017745497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendelsohn AH, Elashoff DA, Abemayor E, St John MA. Surgery for papillary thyroid carcinoma: is lobectomy enough? Archives of otolaryngology-head & neck surgery. 2010;136:1055–61. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ricarte-Filho J, Ganly I, Rivera M, Katabi N, Fu W, Shaha A. et al. Papillary thyroid carcinomas with cervical lymph node metastases can be stratified into clinically relevant prognostic categories using oncogenic BRAF, the number of nodal metastases, and extra-nodal extension. Thyroid: official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2012;22:575–84. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li T, Sheng JG, Li WQ, Shi YQ, Chen XY, Zhang JQ. et al. [The derivation and validation of a prediction rule for differential diagnosis of thyroid nodules] Zhonghua nei ke za zhi. 2013;52:945–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasaian K, Wiseman SM, Walker BA, Schein JE, Zhao Y, Hirst M. et al. The genomic and transcriptomic landscape of anaplastic thyroid cancer: implications for therapy. BMC cancer. 2015;15:984. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1955-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodward EL, Biloglav A, Ravi N, Yang M, Ekblad L, Wennerberg J. et al. Genomic complexity and targeted genes in anaplastic thyroid cancer cell lines. Endocrine-related cancer. 2017;24:209–20. doi: 10.1530/ERC-16-0522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]