Abstract

Pre-clinical cell and animal nutrigenomic studies have long suggested the modulation of the transcription of multiple gene targets in cells and tissues as a potential molecular mechanism of action underlying the beneficial effects attributed to plant-derived bioactive compounds. To try to demonstrate these molecular effects in humans, a considerable number of clinical trials have now explored the changes in the expression levels of selected genes in various human cell and tissue samples following intervention with different dietary sources of bioactive compounds. In this review, we have compiled a total of 75 human studies exploring gene expression changes using quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR). We have critically appraised the study design and methodology used as well as the gene expression results reported. We herein pinpoint some of the main drawbacks and gaps in the experimental strategies applied, as well as the high interindividual variability of the results and the limited evidence supporting some of the investigated genes as potential responsive targets. We reinforce the need to apply normalized procedures and follow well-established methodological guidelines in future studies in order to achieve improved and reliable results that would allow for more relevant and biologically meaningful results.

Keywords: health effects, plant food bioactives, mRNA levels, RT-qPCR, human tissues, interindividual variability

1. Introduction

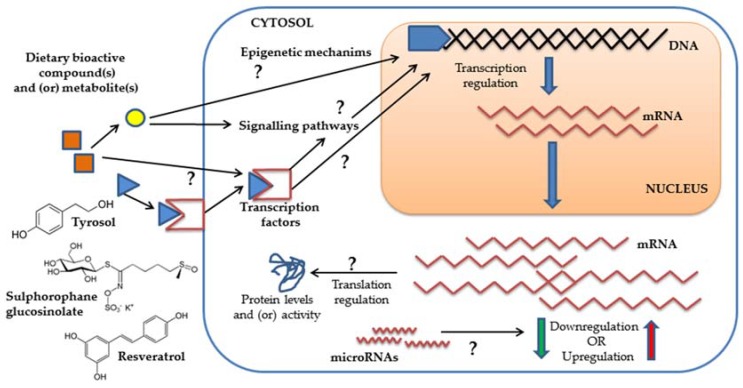

Plant foods and many of their derived products (beverages, oils, extracts) contain a variety of essential and non-essential bioactive compounds (mostly fatty acids and phytochemicals) which have been endorsed with a variety of biological activities that can contribute to the promotion of a healthy status and/or the prevention of various chronic and inflammatory disorders (e.g., cancer, obesity, cardiovascular and neurological diseases) [1,2]. A large number of pre-clinical studies have repeatedly shown that exposure of human cultured cells or animal models to some of these bioactive compounds and/or some of their derived metabolites is associated with changes in the levels of a wide array of molecular targets which suggest that this might constitute one of the mechanisms of action by which dietary bioactive compounds exert their beneficial effects [3]. Many of these compounds have been shown to exert anti-proliferative [4], anti-inflammatory [5] and anti-obesity [6] effects as well as cardiovascular [7] and neurological [8] protection, in association with changes in the expression of genes implicated in cancer development (TP53, CTNNB1, MYC, MMPs), apoptosis (CASPs, BAX, BCL2), cell cycle control (CDKN1A, CDKN2A), transcription (NFKB, AKTs, STATs, NFE2L2, JUN), cell adhesion (VCAM1, ICAM1), inflammation (TNF, ILs, NOS2, PTGS2, CCL2), xenobiotic metabolism (CYPs, UGTs, SULTs), energy metabolism (PRKAs (AMPK), PPARs, PPARGC1A, UCPs), transporters (SLC2A4), and/or redox processes (NOS2, GPXs, GSTs, SODs, CAT) to mention but a few examples. Many of these molecular targets are involved in multiple cellular processes and appear to be commonly responsive to different compounds and thus, different bioactives or bioactive-containing products appear to exert their anti-inflammatory effects by downregulating the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF, IL1B and IL6, to reduce weight gain by altering key metabolic regulators like PRKAs (AMPK), PPARs or UCPs or to exert antioxidant effects by the modulation of key targets such as HMOX1 or GPX (extensive reviews on the regulation of genes by plant food bioactives in relation with chronic disorders can be seen at [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. It has been proposed that the molecular responses to the bioactive compounds may be universal and present a high level of complexity given the large number of different molecules that can be modulated in the different types of cells and tissues within the body [9]. The specific mechanisms by which the dietary bioactive compounds or their derived metabolites may affect the different molecular targets have not yet been elucidated. Many of the molecular target changes have been shown at the level of gene expression and thus, it has been postulated that the effects of the bioactive compounds may be mediated by the induction or repression of gene expression via direct molecular interaction (signaling pathways, transcription factors) or, most likely, by epigenetic mechanisms (DNA methylation, histone modifications, microRNAS or LncRNAs) [9,10] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme summarizing some of the general potential molecular mechanisms triggered in cells by bioactive compounds and/or derived metabolites and that may promote gene expression changes.

Another crucial issue that remains unresolved is the verification in humans of the proposed molecular responses to the intake of these compounds. An increasing number of human intervention trials have attempted to explore the effects of the consumption of different bioactive compounds or bioactive-containing foods or products on gene expression in different human tissues but, the results are still very limited. Despite the guiding principles proposed by the MIQE guidelines [11] to improve the general quality of gene expression biomedical research, many errors such as inappropriate study design and sampling protocols and gene expression data analysis-related incorrectness continue to be reported [12]. The validation of the involvement of specific gene targets and molecular mechanisms in the response to specific bioactive compounds or metabolites poses an extra level of difficulty in human dietary intervention studies that, at present, is far from being resolved. In this review, we have compiled a selection of human intervention trials in which the sample population was challenged with a source of bioactive compound(s), i.e., diets, foods or food-derived products (extracts, drinks, oils) and in which gene expression responses were investigated in different cells and tissue samples using RT-qPCR, the gold standard for accurate and sensitive measurement of gene expression [13]. Our main aims were to: (1) critically appraise the experimental design, methodology and gene expression data analysis applied in these studies; and (2) re-examine and discuss the accumulated evidence and relevance of the attained results. We herein reinforce the urge to follow general normalized procedures to improve the quality of future nutrigenomic studies so that we can collect most reliable gene expression responses to food bioactive compounds in humans and provide better evidence of the molecular targets and mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of these compounds.

2. Literature Searching, Studies Selection and Data Extraction

This review has collected human clinical trials in which the test group of volunteers was administered with different dietary sources of bioactive compounds and where potential gene expression changes were investigated in human cells or tissues using RT-qPCR in response to the intervention. A search of the literature was undertaken using the PubMed database (last date assessed February 2018). Several key words were used in combination: (human OR humans OR patient OR patients OR volunteer* OR participant* OR subject* OR male OR males OR female OR females OR men OR women) AND (gene regulation OR nutrigenomic* OR gene OR genes OR gene expression OR transcription OR transcriptomic* OR mRNA OR messenger RNA OR RT-PCR OR real-time PCR OR PCR-arrays) AND (plant bioactive* OR polyphenol* OR phenolic* OR flavonoid* OR carotenoid* OR phytosterol* OR glucosinolate* OR fatty acids).

Human trials performing only microarray analyses for gene expression changes in response to dietary bioactive compounds were not specifically searched for and, therefore, not included in this review because of the broad diversity of analytical strategies, the complexity and large differences in the data reporting, and the still requested validation of the results by RT-qPCR. This type of studies deserves a complete separate revision. After we excluded some manuscripts reporting only microarray results, we revised and compiled information from 75 human intervention trials published between 1994 and 2018 (supplementary Table S1) [4,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87]. Data extraction was conducted by two independent reviewers (BP and MTGC) and distributed in Supplementary Tables S1–S3. We classified the trials by intervention type and recorded the type of participants and trial design; involved groups (control, treatment); dose and duration; and associated bioavailability studies (Supplementary Table S1). We then assessed the reporting of several critical methodological details: description, preparation and characterization of the biological samples; experimental protocols applied for RNA isolation and characterization, and the selection of the reference gene(s) for data normalization (Supplementary Table S2). We finally recorded the gene expression changes reported in the manuscripts as potentially attributed to the interventions, the type of comparisons and sample size for each group compared, as well as the data analysis and presentation. We additionally searched for information about the potential association of the gene expression results with the presence of bioactive compounds and/or derived metabolites detected in the body after the intervention and/or with potential confirmatory changes at the protein level (Supplementary Table S3).

3. Summary of the Experimental Designs of the Intervention Trials Examined in this Review

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) constitute one of the most powerful tools of research to evaluate the effectiveness of intervention with a drug or a dietary compound such as bioactive compounds on human health [88]. Of the studies included in this review (Supplementary Table S1) a considerable proportion (76%) was randomized with ~60% designed in parallel groups and ~39% in crossover. About 65% of these randomized studies were also blinded, most commonly (84%) double blinded, indicating that a good proportion of the trials follow an appropriate design. A few parallel or crossover studies did not report randomization and/or blinding. Regarding the sex of the participants, 59% of the studies were conducted in mixed cohorts of men and women, 33% in groups of men and only 8% in women. As for the health status, nearly 60% of the studies were carried out in healthy volunteers including some healthy obese people, smokers and sportive individuals. Among the disease groups, gene expression studies were carried out in patients with various disorders such as metabolic syndrome (MetS), diabetes, hypertension, obesity, risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), diverse types of cancer (oral, colon, prostate, leukemia) and various other inflammatory diseases (chronic gastritis, photo-dermatosis, sickle cell disease, Friedrich ataxia, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, cystic fibrosis).

We have collected a total of 75 intervention studies looking at the effects on gene expression of the intake of a variety of sources of bioactive compounds, from complex mixtures such as mix meals and diets (fruit + vegetable diets, Mediterranean diets), foods and derived food products (broccoli, oils, nuts, beverages, onions, fermented papaya, propolis), and extracts and supplements (grape, berry and pomegranate extracts, plant extracts, oil derived extracts and compounds, mixed supplements), to single compounds such as β-carotene (β-car), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), resveratrol (Res), quercetin (Quer), flavopiridol, genistein, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), and curcumin (Cur). The duration of the interventions ranged from a few days up to one year but most studies were carried out in periods between one and 3–4 months. Approximately 15% of the studies were classified as acute or postprandial since gene expression was measured within 3–24 h of the intake. The doses of the test compounds/products were very variable and fluctuated between a few mg to g quantities. For example, the doses employed with single bioactive compounds varied between 30 mg of β-car [71], Quer [79], or genistein [83], up to nearly 3 g of EPA/DHA [72] or Res [76] and even up to 12 g of Cur [87]. Comparisons between several doses were also investigated in several studies (n = 19) and in 3 studies the exact daily dose of the treatment was not reported.

One of the most critical points in a clinical trial design is the use of appropriate control groups and one of the best approaches should be the use of a matched placebo in which the control group would consume an almost identical test product containing all the constituents except for the bioactive ingredient [89]. The selection of a suitable control group is particularly complicated in trials with dietary interventions as evidenced by the variety of comparative strategies applied in the different studies included in this review. There were a considerable number of single-arm studies that did not include comparison to a control group and the changes in gene expression were only reported between after (post-) and before (pre-) intervention. Other trials estimated gene expression differences: (i) between low vs. high doses of the test bioactive compound(s), as in several studies looking at the effects in gene expression of the bioactive compounds present in the olive oil [27,28,30,31,34,35] or those present in broccoli sprouts [21,26]; (ii) between different diets [18,19] or food products [22,32,33,55]; and (iii) comparison to a placebo group [15,49,50,51] not always well described.

Around 50% of the trials included the study of the appearance and/or changes in urine, plasma and/or in some tissues of the levels of different compounds and metabolites that were potentially derived from the intake of the test product, i.e., bioavailability studies. For example, the intake of mix fruit and vegetable was found to be associated with changes in the levels of carotenoids in plasma and of flavonoids in urine [15,16,17], the intake of broccoli with increases of sulphoraphane metabolites in urine and plasma [21,22,25], the intake of olive oil products with changes in tyrosol (Tyr) and derived metabolites (hydroxytyrosol, HTyr) in urine and plasma [28,30,31,34,35], or the presence of urolithins in prostate [37] and colon [4] tissues with the intake of walnuts and pomegranate. Some of the trials carried out with single compounds also reported the appearance of β-car [71], EPA/DHA [72], Res [73,74,76,77], Quer [80,81] or EGCG [85]. Of note, a few trials reported a high interindividual variability in the presence of the bioactive compounds and/or metabolites in the biological samples examined [4,37,76].

4. Overview of Some Critical Issues Related to the RT-qPCR Experimental Protocols Used in the Intervention Trials

RT-qPCR remains a most sensitive and reliable technique that can specifically measure small to moderate changes in mRNA levels in cells and tissues in response to environmental challenges [13] such as those promoted by dietary supplementation with bioactive compounds and/or foods and food products enriched in these compounds. Supplementary Table S2 collects information about some of the most critical points relative to the RT-qPCR experimental protocols form all the human intervention studies gathered in this review, i.e., type of samples (cells or tissues) and preparation, RNA extraction protocols and quantity/quality assessment as well as the house keeping gene(s) used as a reference for data normalization.

4.1. Sample Characterization and Handling

The majority of the intervention studies included in this review used RNA extracted from whole blood (10 studies) or from blood isolated immune cells (40 studies), principally from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (55%), as the target tissues in which to measure gene expression changes that might be attributed to the intervention with the test products containing bioactive compounds. Also, isolated lymphocytes were the target tissue in seven studies [14,38,42,43,44,60,79], and monocytes, polymorphonuclear granulocytes and neutrophils were used in one or two studies [23,45,60,81]. A total of 10 studies reported gene expression changes in tissue samples from the gastrointestinal tract (oral, stomach, small intestine and colon samples) [4,21,47,48,52,54,61,66,71,86]. Other additional internal tissue samples used in humans were biopsies from prostate [29,37,83], adipose tissue [36,73,74,85], skeletal muscle tissue [73,74,75,80,84] and skin samples [46,59,68,69]. One study looked at gene expression changes in cells present in nasal lavage [22]. In general, and despite the fact that all these blood cells and tissue samples are heterogeneous and constituted by different types of cells, most of the studies examined here did not report a complete blood count and blood cell proportions or some description of the cell types and composition present in any of the investigated tissues. Only one study, reported the proportion of immune cells forming the isolated mononuclear cell samples showing moderate interindividual variability in the cell composition: lymphocytes (84.4 ± 2.9%), monocytes (13.0 ± 3.2%) and granulocytes (2.2 ± 1.4%) [51]. A few other studies reported mononuclear cells purity (>95%) [58], isolated blast cells enrichment (>70%) [82], or neutrophils enrichment and viability (>90% cells, 90% viable) [45]. In the biopsies, classification between cancer and non-cancerous tissue samples was indicated to be carried out by specialized pathologists but no further description of the cell composition within the samples was included [4,37]. Only one study used laser capture microdissection for tissue sampling attaining a specific number of cells (10,000) from benign and from normal tissues [83].

Sample handling and preparation protocols also contribute to the experimental variability and thus, it is important to report in as much detail as possible how the samples were obtained and processed until use [11]. The revision of this part of the experimental protocol in all the selected articles evidenced a general poor or limited description of the procedure used to obtain the samples as well as about the processing time, the sample storage conditions and the time elapsed until RNA extraction. There is a broad variation in the sampling procedures used or the information reported with a considerable number of studies including few details. For example, for the gene expression studies carried out in whole blood, only half of them specifically reported the collection of fasting blood samples. Also, only six of these studies applied a specific commercial kit for direct RNA isolation from blood whereas the rest of the studies did not provide any information about the protocol used. In those cases where the storage was reported, the most common way of long term sample storing was at −80 °C (as shown in ~40% of the studies). However, the time elapsed before storage was not reported in many of the studies and, in those where it was indicated, it varied from quick-freezing in liquid N2 to maintenance and/or transport at room/low temperature for several hours before freezing. The preservation solution varied between studies (RNAlater or lysis buffer were most commonly used, but other buffers, DEPC-treated solutions, or even specific cell culture medium were also used). Further, and importantly, there was no reporting of the storage time period prior to the RNA extraction except for one study that indicated to have done gene expression analyses within one month of storage [61].

4.2. RNA Extraction Protocols, Quantity and Quality

RNA extraction, quantitation and integrity inspection are also critical steps that can influence the gene expression changes. The use of different RNA extraction protocols may account for some of the differences in gene expression results and various factors can affect the final quantity and quality of the isolated RNA (i.e., degradation by ubiquitous RNases, co-extraction of inhibitors, presence of contaminant DNA and/or protein) potentially compromising the results of the RT-qPCR analysis [12]. This is especially critical if we want to compare results from different studies. In this review, most of the studies indicated to have isolated the RNA using one of the many different commercially available extraction kits including mostly those based on affinity columns or those using the Trizol reagent and liquid-liquid extraction. Nevertheless, about 17% of the studies did not describe clearly the protocol used. In addition, of all the studies included, only 12 studies (16%) specified to have applied a DNase treatment in the procedure to remove contaminating genomic DNA.

Reliable analysis of changes in the mRNA levels requires that the extracted RNA is of high quality and that both the quantity and integrity is accurately determined [90]. This is especially relevant in human clinical studies with usually limited and unique tissue samples, however, not many publications report RNA yield and/or quality values [12]. In this review, most of the selected studies that indicated to have measured the quantity of extracted RNA, reported to have done so by spectrophotometry (Abs 260 nm) using the NanoDrop system in many cases. Only in one study they used the Ribogreen method [44]. Nevertheless, none of the studies presented information about the RNA yield obtained from the specific cells or tissues analyzed except for one study where they indicated an average RNA yield of 0.3–1.0 μg extracted from nasal lavage samples [22].

Of the 75 clinical studies included in this review, we found that 66 publications (88%) did not report any quality score of the RNA samples used in the gene expression studies even though, a considerable number of these studies reported to have assessed the quality of the RNA, either by spectrophotometry determination of the Abs260/280 (mostly using the NanoDrop system) or by agarose gel and examination of the 18S and 28S bands (often using the Bioanalyzer capillary chips). Of those studies that included information about the RNA quality, two of them only mentioned that some of the samples had low quality [15,82] and four studies reported the quality of the ARN based solely on the Abs260/280 with values between 1.8 and 2.1 [37,67,74,75]. Two studies reported the RNA integrity number (RIN) values of their samples, RIN > 8.0 [64] and RIN = 6–9 [54], respectively, and only two other studies combined Abs260/280 and RIN values [4,51] to prove the quality of their RNA samples.

4.3. Reference Genes

The selection of genes stably expressed to be used as endogenous or reference genes remains the most common method for mRNA data normalization and a critical issue in RT-qPCR studies, especially when working with heterogeneous tissue samples. The incorrect use of reference genes can have a profound impact on the results of the study [91]. Table 1 displays the list of reference genes, with the most updated nomenclature available from GeneCards [92], used in the intervention studies included in this review. The majority of these studies used a single gene as a reference with GAPDH being the most commonly one applied, followed by ACTB and 18S rRNA. The rest of the studies applied other common but yet less frequently used genes such as B2M, HPRT1, GUSB, or ribosomal proteins. There were also two studies in which normalization was carried out using the gene AW109 [62], an RNA competitor [93], and single stranded DNA (ssDNA) [75], respectively, as references. As for the type of samples in which these genes were used for normalization, the three top reference genes, GAPDH, ACTB and 18S rRNA, were indistinctively used in a wide range of cell types and tissue samples, i.e., whole blood, mononuclear cells, other various isolated immune circulating cells (lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils), gastrointestinal biopsies, prostate biopsies, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue and skin. On the other hand, in mononuclear cells (the primary type of cells used in the gene expression human studies) most of the listed genes (GAPDH, ACTB, 18SrRNA, HPRT1, B2M, UBC, PPIA, HMBS, YWHAZ, RPL13A, RPLP0) were used as reference genes.

Table 1.

List of reference genes reported in the human intervention studies included in this review.

| Gene Symbol | n Studies 1 | Cell/Tissue Samples in Which the Gene Has Been Used as a Reference Gene |

|---|---|---|

| Most common genes used as reference genes | ||

| GAPDH | 31 [4,16,18,20,25,26,28,32,33,34,35,37,39,40,44,45,46,49,50,51,53,55,57,64,65,67,72,73,78,79,86] 1 tested, but not used [63] |

Blood, white blood cells, mononuclear cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, gastric antrum, colon cancer and colon normal tissue, prostate hyperplasia and prostate cancer tissue, skeletal muscle, adipose tissues |

| ACTB | 16 [14,18,40,41,42,43,46,48,58,63,64,70,76,81,82,84] 1 tested, but not used [53] |

Blood, white blood cells, leukemic blasts, lymphocytes, CD14+ monocytes, colon cancer and colon normal tissue, skeletal muscle tissue, skin tissue |

| 18S rRNA | 11 [15,17,21,22,24,56,59,61,80,85,87] 1 considered, but not used [66] |

White blood cells, mononuclear cells, skeletal muscle tissue, buccal swabs, gastric mucosa, adipose tissue, nasal cells, epidermis blister, buttock skin |

| Other genes less commonly used as reference genes | ||

| B2M | 6 [18,40,70,71,74,82] | Blood, mononuclear cells, leukemic blasts, colon tissue, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue |

| HPRT1 | 3 [18,38,40], 2 tested, but not used [4,72] 1 considered, but not used [66] |

Blood, lymphocytes |

| GUSB | 2 [29,52], 1 tested, but not used [4] | Oral mucosa, prostate tissue |

| RPLP0 | 3 [40,60,82], 1 tested, but not used [63] | Blood, leukemic blasts, lymphocytes, neutrophils |

| RPL13A | 1 [27] | Mononuclear cells |

| RPL32 | 1 [36] | Adipose tissue |

| HMBS | 2 [45,47] | Neutrophils, colon mucosa |

| ATP5O | 1 [66] | Duodenal biopsies |

| DUSP1 | 1 [54] | Oral biopsies |

| ALAS1 | 1 [83] | Prostate cancer and normal tissue |

| YWHAZ | 1 [38] | Lymphocytes |

| UBC | 1 [58] | Mononuclear cells |

| PPIA | 1 [58] | Mononuclear cells |

| G6PD | 2 [66,72] | Blood (tested but not used), duodenal tissue (selected but not used) |

| Other reference molecules used | ||

| AW109 | 1 [62] | Mononuclear cells |

| ssDNA | 1 [75] | Skeletal muscle |

1 Number of studies that report to have used and/or tested the reference gene. Genes nomenclature from GeneCards [92] (in alphabetical order): ACTB, actin beta; ALAS1, 5′-aminolevulinate synthase 1; ATP5O, ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F1 complex, O subunit; AW109, competitor RNA; B2M, beta-2-microglobulin; DUSP1, dual specificity phosphatase 1; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GUSB, glucuronidase beta; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; HMBS, hydroxymethylbilane synthase (alias: PBGD, porphobilinogen deaminase); HPRT1, hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1; PPIA, peptidylprolyl isomerase A; RPLP0, ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0 (36B4 rRNA: encodes for RPLP0); RPL13A, ribosomal protein L13A; RPL32, ribosomal protein L32; 18S rRNA, 18S ribosomal RNA; ssDNA, single stranded DNA; UBC, ubiquitin C; YWHAZ, tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein zeta.

Only a few studies indicated to have used the average value or the combination of various reference genes (GAPDH, ACTB, HPRT1, B2M) [18,40], (GAPDH, ACTB) [64] and (ACTB, UBC, PPIA) [58] for the normalization process whereas others reported to have used separate reference genes (RPLP0, ACTB, B2M) [82] and (GAPDH, HMBS) [45] for the analysis of expression changes of different target genes within the same study. A total of seven studies did not clearly report the use of or the specific reference gene employed in their analyses. Regarding the criteria employed to choose the reference gene(s), very few studies indicated to have taken into consideration either information from the literature [66], the RefGenes tool in the curated expression database Genevestigator [38] or to have determined the stability of the genes using specific tools such as GeNorm or Normfinder [4,76].

4.4. Gene Expression Data Reporting

Supplementary Table S3 compiles information about the different genes that were investigated in each of the trials included in this review. In general, and regarding the sample size, most gene expression analyses were carried out using a small number of individuals per group (generally <25 and, frequently, the control and treated groups were integrated by less than 10–15 individuals). Table S3 includes the list of genes that were found upregulated (↑, red color) or downregulated (↓ green color) in response to each intervention. When available, we added the significance of the change (p-value) and the specific comparison in which the change was detected. We also annotated those genes that exhibited a not significant change and those that were reported not to be affected with the treatment. This information specifically shows the variety of comparative strategies and presentation of results (gene expression change) used in the different studies. Differential expression was reported for some genes as: (i) the difference between after (post-) and before (pre-) intervention (↑HMOX1 in blood after intervention with 150 g of broccoli [26]); (ii) the difference between the treated and the control group only at the end of the intervention period (↑PPARA in blood in a group consuming EPA or DHA against a control group, [72]). There were various other comparative approaches such as between different doses of the bioactive compounds (↑PPARA in white blood cells when comparing olive oil with a high level of polyphenols vs. olive oil with a moderate dose of polyphenols [31]), between different diets (↓UCP2 in blood with tocopherol-enriched Mediterranean diet vs. a Western high-fat diet [19] or between different food products (↑HMOX1 in cells from nasal lavage after intervention with 200 g of broccoli sprouts vs. 200 g of alfalfa sprouts [22]).

For the estimation of the gene expression changes, the majority of the trials reviewed here used relative expression quantification applying the Ct comparative method based on a standard curve, normalized Ct values (using a reference gen) and the 2(−∆∆Ct) formula [94]. Nevertheless, the presentation of the results (expression changes) also varied a lot between the studies. The changes in the genes were reported either as relative expression levels in the different groups (occasionally as arbitrary units or as the number of copies of mRNA), as a change (typically as FC or ratio but also as the % of change) or as a combination of both within the same report. The final results were typically presented using a statistical approach to describe the central tendency and the dispersion of the results but there was also a high variability in the estimators used in each study. Around 65% of the studies used the mean value as an estimator of the average changes but a few studies reported the median [4,14,43,51,66,76] or even the geometric mean of the data [31]. Regarding the dispersion of the results, most studies indicated either the SEM (~35%) or the SD (~29%) but some studies reported the confidence intervals [18,31,47,54,62,77,86] or the quartiles/ranges [4,14,37,42,43,51,66,76,82]. Overall, there was a considerable lack of clarity in the presentation of the results, many of which (~50%) were included only in figures not always well described. In some studies it was not trivial to infer the evidence supporting the changes. Between 23% and 24% of the studies failed to report or to correctly identify the measurement of the average change or the data variability. Of note, a few studies reported the distribution of gene expression changes in the sample population, e.g., % of individuals exhibiting downregulation, upregulation or no change for a particular gene [4,82,86] whereas in some other studies, individual gene expression changes were displayed [14,54,57].

4.5. Gene Expression Results: Association with Bioavailability of Bioactive Compounds and/or with Protein Confirmatory Studies

Of the trials collected in this review that reported the presence of certain compounds and metabolites in the blood, urine and/or tissue samples (bioavailability), only a few (17 studies) attempted to investigate the potential relationship between the gene expression changes detected and the appearance and/or concentration of the specific compounds and/or metabolites. Only 5 of those studies reported some positive or inverse correlations between the changes of the expression in some genes and the levels of some metabolites. For instance, the downregulation of the expression of IFNG, OLR1 or ICAM1 and the upregulation of ABCA1 in peripheral blood cells in association with the increase of Tyr and/or HTyr metabolites in urine or plasma following the intake of olive oil rich in polyphenols [28,30,31]. With regards to the validation of the gene expression changes by further testing the levels of the corresponding proteins and/or protein activity, only 27 studies (36% of total) made an attempt to substantiate gene changes with protein changes. In those, ~50% of the examined gene changes resulted in some confirmatory protein changes, e.g., the downregulation of TNF in blood and the reduction of the plasma levels of TNF following the intake of a grape seed extract [49] or, the upregulation in mononuclear cells of LDLR and the increase in the levels of LDLR in monocytes and T-lymphocytes after the intake of mix plant stanol esters [62].

5. Gene Expression Changes in Human Cells and Tissues in Response to Food Bioactive Compounds: Overview of the Accumulated Evidence

5.1. Gene Expression Changes Specifically Reported in Blood Isolated Immune Cells in Response to Different Sources of Bioactive Compounds

Table 2 collects the genes reported to be significantly (p-value < 0.05) up- or downregulated in blood isolated immune cells after intervention with dietary foods or products containing bioactive compounds. The table indicates the type of cells where the study was carried out, the comparison in which the changes were detected and the potential bioactive compounds involved in the response. Most of the studies were carried out in peripheral blood mononuclear cells but there were some studies looking at isolated lymphocytes [14,34,42,43,79], neutrophils [45,60] or granulocytes [23]. Most trials were carried out with foods or products containing mixed bioactive compounds and only a few studies investigated the effects of isolated compounds, e.g., Quer [79,80] or EPA/DHA [65,67]. The table also indicates the biological processes and health effects investigated in each study in relation with the response to the intervention and to which the changing genes might be associated with, i.e., metabolism of lipids and carbohydrates and associated disorders (atherosclerosis, high blood pressure), regulation of the inflammatory status, and oxidative stress and antioxidant responses. The messages associated with the different interventions and with the changing genes were messages of improvement or beneficial effects. Some of the genes most commonly investigated in relation with these responses and that might be considered as targets responsive to bioactive compounds included well known transcriptional factors, cytokines, key metabolic regulators and antioxidant genes. For instance, some members of the PPAR family (PPARG) were upregulated in circulating blood immune cells in response to the intake of mixed bioactive polyphenols and fatty acids [31,67,70]. Also, some cytokines (TNF) and interleukins (IL1β, IL6) were found to be downregulated in this type of cells following intervention with different oils [27,67], fruit extracts [51] or nuts [38]. Regarding the transcription factors, NFKB and EGR1 were downregulated in these cells after the intake of mixed omega-3 [65] or mixed olive oil bioactive compounds [27,64] whereas NFE2L2 was found increased in response to the mixed compounds present in sunflower oil [32] and in coffee [42,43] but downregulated in response to the intake of a berry extract rich in anthocyanins [53]. Several genes related with the antioxidant status regulation (SODs, CAT, GPX1) also exhibited up- or downregulation in the immune cells with different interventions [32,42,45,60].

Table 2.

Overview of the significant gene expression changes reported in peripheral blood isolated immune cells in response to different interventions with various diets, foods, or derived products containing bioactive compounds (p-value < 0.05).

| Reference | Cells 1 | Groups Compared | Potential Bioactive Compounds (Specifically Indicated in the Article) | Upregulated genes | Downregulated Genes | Main Biological Message Reported in the Article Potentially Associated with the Gene(s) Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells | ||||||

| Daak AA et al., 2015 [65] | White blood cells | Omega-3 capsules vs. placebo capsules (high oleic oil blend) | EPA, DHA | - | NFKB1 | Improvement of oxidative stress status and amelioration of inflammation |

| Farràs M et al., 2013 [31] | White blood cells | Olive oil high polyphenols vs. low polyphenols | Mixed olive oil compounds (polyphenols) | ABCA1, SCARB1, PPARG, PPARA, PPARD, MED1, CD36, PTGS1 | - | Enhancement of cholesterol efflux from cells |

| Nieman DC et al., 2007 [80] | White blood cells | Quer vs. placebo | Quer | - | CXCL8, IL10 | Modulation of post-exercise inflammatory status |

| Mononuclear cells | ||||||

| Konstantinidou V et al., 2010 [28] | Mononuclear cells | Med diet + olive oil vs. control diet | Mixed compounds in the Med diet (potential specific contribution of olive oil polyphenols) | - | ADRB2, ARHGAP15, IL7R, POLK, IFNG | Regulation of atherosclerosis-related genes, improvement of oxidative stress and inflammatory status |

| Radler U et al., 2011 [70] | Mononuclear cells | Low-fat yoghurt containing grapeseed extract + fish oil + phospholipids +L- Carn + VitC + VitE (post vs. pre) | Mixed compounds (polyphenols, fatty acids, vitamins) | PPARG, CPT1A, CPT1B, CRAT, SLC22A5 | - | Regulation of fatty acids metabolism |

| Jamilian M et al., 2018 [67] | Mononuclear cells | Fish oil vs. placebo | Mixed compounds (EPA + DHA) | PPARG | LDLR, IL1B, TNF | Improvement of inflammatory status and of insulin and lipid metabolism |

| Plat J & Mensik RP, 2001 [62] | Mononuclear cells | Oils with mixed stanols vs. control (margarine + rapeseed oil) | Mixed compounds (stanol esters: sitos, camp) | LDLR | - | Improvement of LDL-cholesterol metabolism |

| Shrestha S et al., 2007 [57] | Mononuclear cells | Psyllum + plant sterols vs. placebo | Mixed compounds (Psyllum fiber + plant sterols) | LDLR | - | Improvement of LDL-cholesterol metabolism |

| Perez-Herrera A et al., 2013 [32] | Mononuclear cells | Sunflower oil vs. other oils (virgin olive oil, olive antioxidants, mixed oils) | Mixed compounds in sunflower oil | CYBB, NCF1, CYBA, NFE2L2, SOD1, CAT, GSR, GSTP1, TXN | - | Induction of postprandial oxidative stress (potential reduction by oil phenolics) |

| Rangel-Zuñiga OA et al., 2014 [33] | Mononuclear cells | Heated sunflower oil (post vs. pre) | Mixed compounds in sunflower oil | XBP1, HSPA5, CALR | - | Induction of postprandial oxidative stress |

| Camargo A et al., 2010 [27] | Mononuclear cells | Olive oil high polyphenols vs. low polyphenols | Mixed olive oil compounds (polyphenols) | - | EGR1, IL1B | Lessening of deleterious inflammatory profile |

| Castañer O et al., 2012 [30] | Mononuclear cells | Olive oil high polyphenols (Post vs. Pre) or Olive oil high polyphenols vs. low polyphenols | Mixed olive oil compounds (polyphenols) | - | CD40LG, IL23A, IL7R, CXCR2, OLR1, ADRB2, CCL2 | Reduction of atherogenic and inflammatory processes |

| Martín-Peláez S et al ., 2015 [35] | Mononuclear cells | Olive oil high polyphenols (post vs. pre) or Olive oil high polyphenols vs. low polyphenols | Mixed olive oil compounds (polyphenols) | - | ACE, NR1H2, ILR8 | Modulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and systolic blood pressure |

| Boss A et al., 2016 [64] | Mononuclear cells | Olive leaf extract vs. placebo (glycerol +sucrose, no polyphenols) | Mixed olive leaf compounds (oleuropein, HTyr) | ID3 | EGR1, PTGS2 | Regulation of inflammatory and lipid metabolism pathways |

| Ghanim H et al., 2010 [58] | Mononuclear cells | Polygonum cuspidatum extract vs. placebo | Mixed compounds in Polygonum cuspidatum extract (Res) | IRS1 | MAPK8, KBKB, PTPN1, SOCS3 | Suppressive effect on oxidative and inflammatory stress |

| Barona J et al., 2012 [50] | Mononuclear cells | Grape powder vs. control | Mixed compounds in grape powder (polyphenols) | NOS2 | - | Anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory response |

| Tomé-Carneiro J et al., 2013 [51] | Mononuclear cells | Grape extract, Grape extract + Res (post vs. pre or extracts vs. placebo) | Mixed compounds in grape extract (Res) | LRRFIP1 | IL1β, TNF, CCL3, NFKBIA | Beneficial immune-modulatory effect |

| Kropat C et al., 2013 [53] | Mononuclear cells | Bilberry pomace extract (post vs. pre) | Mixed compounds in bilberry pomace extract (anthocyanins) | NQO1 | HMOX1, NFE2L2 | Regulation of antioxidant transcription and antioxidant genes |

| Isolated single type of cells | ||||||

| Persson I et al., 2000 [14] | Lymphocytes | Mix Veg (post vs. pre) | Mixed compounds in the Mix Veg | - | GSTP1 | Compensatory downregulation of endogenous antioxidant systems |

| Hernández-Alonso P et al., 2014 [38] | Lymphocytes | Diet + pistacchio vs. control diet | Mixed compounds in the pistachio (fatty acids, minerals, vitamins, carotenoids, tocopherols polyphenols) | - | IL6, RETN, SLC2A4 | Impact on inflammatory markers of glucose and insulin metabolism |

| Boettler U et al., 2012 [43] | Lymphocytes | Coffee brew (post vs. pre) | Mixed compounds in coffee (CGA, NMP) | NFE2L2 | - | Regulation of antioxidant transcription |

| Volz N et al., 2012 [42] | Lymphocytes | Coffee brew (post vs. pre) | Mixed compounds in coffee (CGA, NMP) | NFE2L2 | HMOX1, SOD1 | Regulation of antioxidant transcription and antioxidant genes |

| Morrow DMP et al., 2001 [79] | Lymphocytes | Quer vs. placebo | Quer | - | TIMP1 | Mediator of carcinogenic processes |

| Marotta F et al., 2010 [45] | Neutrophils | Fermented papaya (Post vs. Pre) | Mixed compounds in fermented papaya | SOD1, CAT, GPX1, OGG1 | - | Regulation of redox balance |

| Carrera-Quintanar L et al., 2015 [60] | Neutrophils | T1: Lippia citriodora extract T2: Almond beverage (+vitC + vitE) T1 + T2 (post vs. pre) |

Mixed compounds | - | SOD2, SOD1 | Adaptative antioxidant response |

| Yanaka A et al., 2009 [23] | Polymorpho-nuclear granulocytes | Broccoli sprouts (post vs. pre) | Mixed compounds (SFGluc) | HMOX1 | - | Protective effect against bacterial infection (anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory) |

1 White blood cells or Leukocytes: mononuclear cells agranulocytes (lymphocytes and monocytes) and polymorphonuclear granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, mast cells); Lymphocytes (T cells, B cells, NK cells). Table abbreviations (in alphabetical order): camp, campestanol; CGA, chlorogenic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; HTyr, hydroxytyrosol; l-Carn, l-carnitine; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Med, Mediterranean; NMP, N-methylpyridinum; post-, after treatment; pre-, baseline or before treatment; Quer, quercetin; Res, resveratrol; SFGluc, sulforaphane glucosinolates; sitos, sitostanol; Veg, vegetables; VitC, vitamin C; VitE, vitamin E. Genes nomenclature from GeneCards [92] (in alphabetical order) : ABCA1, ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 1; ACE, angiotensin I converting enzyme; ADRB2, adrenoceptor beta 2; ARHGAP15, rho GTPase activating protein 15; CALR, calreticulin (alias: CRT); CAT, catalase; CCL2, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (alias: MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein 1); CCL3, C-C motif chemokine ligand 3; CD36, CD36 molecule; CD40LG, CD40 ligand; CPT1A, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A; CRAT, carnitine O-acetyltransferase; CXCL8, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 (alias: IL8); CXCR2, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (alias: IL8RA); CYBA, cytochrome B-245 alpha chain (alias: P22-Phox); CYBB, cytochrome B-245 beta chain (alias: NOX2, GP91-Phox); EGR1, early growth response 1; GPX1, glutathione peroxidase 1; GSTP1, glutathione S-transferase Pi 1; GSR, glutathione-disulfide reductase (alias: GRD1); HMOX1, heme oxygenase 1 (alias:HO-1); HSPA5, heat shock protein family A (Hsp70) member 5 (alias: BIP); ID3, inhibitor of DNA binding 3, HLH protein; IFNG, interferon gamma; IL1B, interleukin 1 beta; IL6, interleukin 6; IL7R, interleukin 7 receptor; IL10, interleukin 10; IL23A, interleukin 23 subunit alpha; IRS1, insulin receptor substrate 1; LDLR, low density lipoprotein receptor; LRRFIP1, LRR binding FLII interacting protein 1; MAPK8, mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 (alias: JKN1); MED1, mediator complex subunit 1 (alias: PPARBP); NFE2L2, nuclear factor, erythroid 2 like 2 (alias: NRF2); NQO1, NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1; NOS2, nitric oxide synthase 2 (alias: iNOS); NR1H2, nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group H member 2; OGG1, 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase; OLR1, oxidized low density lipoprotein receptor 1; POLK, DNA polymerase kappa; PPARA, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha; PPARD, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor delta; PPARG, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma; PTGS1, prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 (alias: COX1); PTGS2, prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (alias: COX2); PTPN1, protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 1 (alias: PTP1B); RETN, resistin; SCARB1, scavenger receptor class B member 1 (alias: SRB1); SLC2A4, solute carrier family 2 member 4 (alias: GLUT4); SLC22A5, solute carrier family 22 member 5 (alias: OCTN2); SOCS3, suppressor of cytokine signaling 3; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1 (alias: Cu/ZnSOD); SOD2, superoxide dismutase 2 (alias: MnSOD); TIMP1, TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1; TNF, tumor necrosis factor (alias: TNFα); TXN, thioredoxin; XBP1, X-box binding protein 1. Orange color: upregulated genes; green color: downregulated genes.

5.2. Accumulated Evidence for Specific Gene Targets in Response to Different Sources of Bioactive Compounds

We specifically looked at all the changes reported in different cells and tissues for some genes that might be considered targets responsive to bioactive compounds and that are associated with inflammation (TNF) (Supplementary Table S4), energy metabolism (PPARs) (Supplementary Table S5), and antioxidant effects (GPXs) (Supplementary Table S6). As already stated, data reporting was variable among the studies and the quality of the results was generally poor. Where possible and using the information available from the articles we estimated the coefficient of variation (CV) of the reported gene expression changes. Overall, between 40% and 60% of the studies reported a lack of effect of the intervention on the selected genes.

Main details and results from those other studies reporting significant outcomes for TNF, PPARs and GPXs expression changes are gathered in Table 3. Based on these results, it would appear that the intake of different mix bioactive compounds could be associated with the downregulation of TNF and the upregulation of some PPARS (PPARA, PPARG) and GPXs (GPX1) genes in blood and/or in isolated blood immune cells. There were, however, some opposed significant results such as the upregulation exhibited by TNF expression levels in blood in response to EPA/DHA [72]. Also, different members of the same family of genes may react differently as it was the case of the GPX genes in response to the intake of hazelnuts [40]. Regarding the effect size (gene expression changes) and, for comparative purposes, we estimated and converted all the results into FC-values and % of change. We observed a large variation in the changes reported ranging from very small FC-values, e.g., +1.06 (6%) for PPARG in mononuclear cells [67] or +1.07 (7%) for TNF in blood [72] to rather high changes, i.e., FC > +2.5 (>150%) such as those reported for some members of the PPARs and GPXs families [18,31,70]. As for the variability in these gene expression responses, in those studies for which we were able to estimate the CV, these CV values were high and variable. In some cases, the % of change attributed to the intervention was in the range of the estimated CV, e.g., the 11% reduction of TNF by fish oil EPA + DHA with an estimated variability of 10.5–18.0% [67]. In other studies, the CV was well above the % of change attributed to the intervention, e.g., a 100% increase in PPARA attributed to mix olive oil compounds with estimated CV values > 100% [31]. In addition, none of these studies reported the potential association between those gene expression changes and the presence or changes in the quantities of specific compounds or derived metabolites in the samples and, there was little or none evidence supporting the regulation of the corresponding encoded proteins. Overall, the level of evidence supporting the specific described gene changes as potential mechanisms of response to the intake of the bioactive compounds present in the test food products investigated remains very low.

Table 3.

Overview of the significant expression changes reported for specific gene targets in different cells and tissue samples following intervention with diet, foods, or derived products containing bioactive compounds. Analysis of the evidence supporting the changes and, the potentiality of these changes as a mechanism of action underlying the beneficial effects attributed to these products and bioactive compounds (p- value < 0.05).

| Reference | Cells 1 (n = Number of Samples Analysed) | Groups Compared | Potential Bioactive Compounds (Specifically Indicated in the Article) | Gene Expression Change (FC; % of Change) | Data Quality | Variability (Estimated CV %) | Association with Specific Compounds, Metabolites | Protein Change | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammation: TNF | |||||||||

| Di Renzo L. et al., 2017 [40] | Blood (n = 22) |

McD meal + hazelnuts vs. McD meal (post-) |

Mix compounds present in the hazelnuts (fatty acids, polyphenols, etc.) | ↓TNF (FC < -1.5; −34%) |

Poor | No information available | No evidence | No evidence | Low |

| Weseler AR et al., 2011 [49] | Blood (n = 15) |

Grape seeds (post- vs. pre-) |

Mix compounds present in the seeds (flavanols) | ↓TNF (FC = -1.14; −12%) |

Poor | No information available | No evidence | Inhibition of ex vivo LPS-induced TNF in blood | Low |

| Tomé-Carneiro J et al., 2013 [51] | Mononuclear cells (n = 9–13) |

Grape extract + Res (post- vs. pre-) Grape extract + Res vs. control (post-) |

Mix compounds present in the grape extract + Res | ↓TNF (FC = −2.56 to −1.54; −61% to −35%) |

High | 3.2–7.9 (only baseline levels) | No evidence | (NC) TNF in serum or plasma | Low |

| Jamilian M et al., 2018 [67] | Mononuclear cells (n = 20) |

Fish oil (EPA + DHA) vs. placebo (post-) | Fish oil compounds (EPA + DHA) | ↓TNF (FC = −1.12; −11%) |

Medium-Poor | 10.5–18.0 | No evidence | No evidence | Low |

| Vors C. et al., 2017 [72] | Blood (n = 44) |

EPA vs. control (post-) DHA vs. control (post-) |

EPA, DHA | ↑TNF (EPA, FC = +1.07; 7%)(DHA, FC = +1.09; 9%) |

Poor | 19.8–24.2 | No evidence | No correlation between TNF and TNF in plasma | Low |

| Energy metabolism: PPARs | |||||||||

| Radler U et al., 2011 [70] | Mononuclear cells (n = 20–22) |

Low-fat yoghurt (grapeseed extract + fish oil + phospholipids + l-carn + vitC + vitE) (post- vs. pre-) |

Mix compounds (PUFAs, polyphenols, l-carn) | ↑PPARG (FC = +2.53; 153%) |

Poor | 49.8 | No evidence | No evidence | Low |

| Vors C et al., 2017 [72] | Blood (n = 44) |

EPA vs. control (post-) DHA vs. control (post-) |

EPA DHA |

↑PPARA (EPA, FC = +1.12; 12%) (DHA, FC = +1.10; 10%) |

Poor | 17.9–26.1 | No evidence | No evidence | Low |

| Jamilian M et al., 2018 [67] | Mononuclear cells (n = 20) |

Fish oil (EPA + DHA) vs. placebo (post-) | Fish oil compounds (EPA + DHA) | ↑PPARG (FC = +1.06; 6%) |

Medium-Poor | 9.0–11.3 | No evidence | No evidence | Low |

| Farràs M al., 2013 [31] | White blood cells (n = 13) |

High- vs. low-polyphenols in olive oil | Mix olive oil compounds (polyphenols) | ↑PPARG (FC = +2.8; 180%) ↑PPARA (FC = +2.0; 100%) ↑PPARD (FC = +2.0; 100%) ↑MED1 (FC = +1.45; 45%) |

Poor | 32.2–118.3 | No evidence | No evidence | Low |

| Antioxidant system: GPXs | |||||||||

| Di Renzo L et al., 2014 [18] | Blood (n = 24) |

Red wine Med meal + red wine McD meal + red wine (post- vs. pre-) |

Mix compounds in red wine | ↑GPX1 (FC = +1.41; 41%) (FC = +1.52; 52%) (FC = +2.83; 183%) |

Poor | No information available | No evidence | No evidence | Low |

| Di Renzo L. et al., 2017 [40] | Blood (n = 22) |

McD meal + hazelnuts vs. McD meal (post-) |

Mix compounds present in the hazelnuts (fatty acids, polyphenols, etc.) | ↑GPX1, GPX3, GPX4 (F > +1.5; 50%) |

Poor | No information available | No evidence | No evidence | Low |

| ↓GPX7 (FC < −1.5; −33%) | |||||||||

| Donadio JLS et al., 2017 [39] | Blood (unclear, n = 130 or n = 12?) |

Brazil nuts (with Se) (post- vs. pre-) |

Mix compounds present in the brazil nuts (Se, fatty acids, polyphenols, etc.) | ↑GPX1 (FC = +1.3; 30% for a particular genotype) |

Poor | No information available | No evidence | No evidence | Low |

| Marotta F et al., 2010 [45] | Neutrophils (n = 11) |

Fermented papaya (post- vs. pre-) |

Mix compounds present in the fermented papaya | ↑GPX1 (FC = +61–67; >6000% (?)) |

Poor | No information available | No evidence | No evidence | Low |

1 White blood cells or Leukocytes: mononuclear cells agranulocytes (lymphocytes and monocytes) and polymorphonuclear granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, mast cells). Table abbreviations (in alphabetical order): CV, coefficient of variation; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; FC, fold-change; l-carn, l-carnitine; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; McD, MacDonald; Med, Mediterranean; NC, no change; post-, after treatment; pre-, baseline or before treatment; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; Res, resveratrol; Se, selenium; VitC, vitamin C; VitE, vitamin E. Genes nomenclature from GeneCards [92] (in alphabetical order): GPX1-4, glutathione peroxidase 1-4; MED1, mediator complex subunit 1 (alias: PPARBP); PPARA, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha; PPARD, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor delta; PPARG, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma; TNF, tumour necrosis factor (alias: TNFα). Orange color: upregulated genes; green color: downregulated genes.

Main details and results from those other studies reporting significant outcomes for TNF, PPARs and GPXs expression changes are gathered in Table 3. Based on these results, it would appear that the intake of different mix bioactive compounds could be associated with the downregulation of TNF and the upregulation of some PPARS (PPARA, PPARG) and GPXs (GPX1) genes in blood and/or in isolated blood immune cells. There were, however, some opposed significant results such as the upregulation exhibited by TNF expression levels in blood in response to EPA/DHA [72]. Also, different members of the same family of genes may react differently as it was the case of the GPX genes in response to the intake of hazelnuts [40]. Regarding the effect size (gene expression changes) and, for comparative purposes, we estimated and converted all the results into FC-values and % of change. We observed a large variation in the changes reported ranging from very small FC-values, e.g., +1.06 (6%) for PPARG in mononuclear cells [67] or +1.07 (7%) for TNF in blood [72] to rather high changes, i.e., FC > +2.5 (>150%) such as those reported for some members of the PPARs and GPXs families [18,31,70]. As for the variability in these gene expression responses, in those studies for which we were able to estimate the CV, these CV values were high and variable. In some cases, the % of change attributed to the intervention was in the range of the estimated CV, e.g., the 11% reduction of TNF by fish oil EPA + DHA with an estimated variability of 10.5–18.0% [67]. In other studies, the CV was well above the % of change attributed to the intervention, e.g., a 100% increase in PPARA attributed to mix olive oil compounds with estimated CV values > 100% [31]. In addition, none of these studies reported the potential association between those gene expression changes and the presence or changes in the quantities of specific compounds or derived metabolites in the samples and, there was little or none evidence supporting the regulation of the corresponding encoded proteins. Overall, the level of evidence supporting the specific described gene changes as potential mechanisms of response to the intake of the bioactive compounds present in the test food products investigated remains very low.

5.3. Summary of the Effects on Gene Expression of Specific Food Products Containing Bioactive Compounds

Table 4 gathers the reported changes on gene expression following the consumption of three of the most investigated plant derived foods and products containing different families of bioactives, i.e., olive oil and extracts rich in polyphenols, mostly focused on Tyr and HTyr [27,28,30,31,34,35,36,63,64]; broccoli sprouts and derived products rich in sulphoraphane glucosinolates (SFGluc) [21,22,23,24,25,26]; and grape extracts containing polyphenols, mainly with a focus on Res [48,49,50,51,73,74,75,76,77,78]. Most of these gene expression changes were investigated in blood or peripheral blood immune cells except for a few studies conducted in adipose and/or skeletal tissue, and in samples from the gastrointestinal tract.

Table 4.

Overview of the significant gene expression changes attributed to the intervention with specific foods or derived products containing bioactive compounds and reported in different cells and tissue samples (p-value < 0.05).

| Reference | Cells 1 | Groups Compared | Potential Bioactive Compounds (Specifically Indicated in the Article) | Upregulated Genes | Downregulated Genes | Genes not Changing or with a Not Significant Change | Association with Metabolites | Effect on Protein Levels | Main biological Message Reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olive oil and derived products | |||||||||

| Farràs M et al., 2013 [31] | White blood cells 1 | High vs. moderate polyphenol olive oil (post-) | Olive oil polyphenols | ABCA1, SCARB1, PPARG, PPARA, PPARD, MED1, CD36, PTGS1 | - | (NC) ABCG1, PTGS2 | ↑HTyr acetate in plasma with ↑ABCA1 | NR | Enhancement of cholesterol efflux from cells |

| Konstantinidou V et al., 2010 [28] | Mononuclear cells | Med diet + olive oil (polyphenols) vs control diet (post-) |

Mix compounds present in the Med diet and the olive oil (fatty acids, polyphenols, vitamins etc.) | - | ADRB2, ARHGAP15, IL7R, POLK, IFNG | - | ↓IFNG with ↑Tyr in urine (highest dose of olive oil) | ↓ IFNγ in plasma (post- vs. pre-) | Regulation of atherosclerosis-related genes, improvement of oxidative stress and inflammatory status |

| Camargo A et al., 2010 [27] | Mononuclear cells | High vs. low polyphenol olive oil (post-) | Olive oil polyphenols | - | EGR1, IL1B | (NS↓) JUN, PTGS2 | NR | NR | Lessening of deleterious inflammatory profile |

| Castañer O et al., 2012 [30] | Mononuclear cells | High vs. low polyphenol olive oil (post-) | Olive oil polyphenols | - | CD40LG, IL23A, IL7R, CXCR2, OLR1, ADRB2, CCL2 | (NS↓) IFNG, VEGFB, ICAM1 (NC) ALOX5AP, TNFSF10 |

↓OLR1 with the ↑Tyr and ↑HTyr in urine | ↓CCL2 | Reduction of atherogenic and inflammatory processes |

| Hernáez Á et al., 2015 [34] | Mononuclear cells | High vs. low polyphenol olive oil (post-) | Olive oil polyphenols | - | - | (NS↑) LPL | NR | NR | Reduction of LDL concentrations and of LDL atherogenicity |

| Martín-Peláez S et al., 2015 [35] | Mononuclear cells | High vs. low polyphenol olive oil (post-) | Olive oil polyphenols | - | ACE, NR1H2, CXCR2 | (NS↓) CXCR1, ADRB2, MPO, ACE (NC) ECE2, OLR1 |

NR | NR | Modulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and systolic blood pressure |

| Crespo MC et al., 2015 [63] | Mononuclear cells | Olive mill waste water extract Hytolive (enriched in HTyr) vs. placebo (post-) | Olive waste polyphenols (HTyr) | - | - | (NC) Phase II enzymes: NQO1,2, GSTA1,4, GSTK1, GSTM1-5, GSTO1,2, GSTP1, GSTM1,2, HNMT, INMT, MGST1-3 | NR | NR | Hormesis hypothesis of activation of phase II enzymes by polyphenols |

| Boss A et al., 2016 [64] | Mononuclear cells | Olive leaf extract (oleuropein, HTyr) vs. placebo (post-) | Olive leaf polyphenols (oleuropein, HTyr) | ID3 | EGR1, PTGS2 | - | NR | NR | Regulation of inflammatory and lipid metabolism pathways |

| Kruse M et al., 2015 [36] | Adipose tissue | Olive oil (MUFA) (post- vs. pre-, postpandrial) | Mix olive oil bioactive compounds | CCL2 | - | (NS↓) IL6, IL8 (NS↑) IL10, TNF (NC) IL1β, ADGRE1, SERPINE1 |

NR | (NC) MCP-1 (CCL2) | Acute inflammatory and metabolic response related genes |

| Broccoli and derived products | |||||||||

| Atwell LL et al., 2015 [25] | Blood | Broccoli sprout (SFGluc) vs. Myrosinase-treated broccoli sprout extract (SFGluc) (post- vs. pre-) |

SFGluc | - | - | (NC) CDKN1A, HMOX1 | NR | (NC) plasma levels of HMOX1 (HO-1) | Search for chemopreventive targets |

| Doss JF et al., 2016 [26] | Blood | Broccoli (SFGluc) | SFGluc | HBG1, HMOX1 | - | (NS↑) NQO1 | NR | (NC) Hbg1 or HbF | Gene expression studies in sickle cell disease (oxidative stress related) |

| Riso P et al., 2010 [24] | Mononuclear cells | Broccoli (SFGluc, Lut, β-car, VitC) (post- vs. pre-) |

SFGluc, Lut, β-car, VitC |

- | - | (NC) OGG1, NUDT1, HMOX1 | NR | NR | Antioxidant protection related to DNA repairing enzymes |

| Yanaka A et al., 2009 [23] | Polymorpho-nuclear granulocytes | Broccoli sprout (SFGluc) (post- vs. pre-) |

SFGluc | HMOX1 | - | - | NR | NR | Protective effect against bacterial infection (anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory) |

| Gasper AV et al., 2007 [21] | Gastric antrum | Broccoli drink (containing SFGluc) (post- vs. pre-) |

SFGluc | GCLM, TXNRD1 | - | (NC) CDKN1A | NR | NR | Effect on xenobiotic metabolism |

| Riedl MA et al., 2009 [22] | Cells from nasal lavage | Broccoli sprout (SFGluc) (different doses) vs. control (alfalfa sprout) |

SFGluc | GSTM1, GSTP1, NQO1, HMOX1 | - | - | NR | NR | Effect on Phase II metabolism |

| Grape products and compounds (Res) | |||||||||

| Weseler AR et al., 2011 [49] | Blood | Flavanols isolated from grape seeds (post- vs. pre-) | Flavanols | - | IL6, TNF, IL10 | (NS↓) CAT, GSR, HMOX1 (NC) IL1β, CXCL8, NOS2, NFKBIA, ICAM1, VCAM1, GPX1, GPX4, SOD2 |

NR | Plasma: ↓TNF (NC) IL10 |

Anti-inflammatory effects in blood |

| Barona J et al., 2012 [50] | Mononuclear cells | Grape powder vs. placebo | Mix compounds in grape (flavonoids) | NOS2 (individuals without dyslipidemia) | - | (NC) CYBB, SOD1, SOD2, GPX1, GPX4 | NR | NR | Anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory response |

| Tomé-Carneiro J et al., 2013 [51] | Mononuclear cells | Grape extract vs Grape extract + Res (post- vs. pre-) |

Polyphenols, Res | LRRFIP1 | IL1β, TNF, CCL3, NFKBIA | (NC) NFKB1 | NR | NC in TNF levels in PBMC or serum | Beneficial immune-modulatory effect |

| Nguyen AV et al., 2009 [48] | Colon tissue (cancer and normal) | Low concentration of grape powder (post- vs. pre-) | Res, flavanols, flavans, anthocyanins, catechin | Normal tissue MYC Cancer tissue MYC, CCND1 |

Normal tissue CCND1, AXIN2 |

- | NR | NR | Effect on cancer related pathway |

| Mansur AP et al., 2017 [78] | White blood cells | Res (post- vs. pre-; T vs. C) |

Res | - | - | (NC) SIRT1 | NR | ↑ Serum hSIRT1 | Comparative study with caloric restriction |

| Chachay VS et al., 2014 [76] | Mononuclear cells | Res (from Polygonium cuspidatum) | Res | - | - | (NC) NQO1, PTP1B, IL6, HMOX1 | NR | ↓plasma IL6 | Effects on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| Yiu EM et al., 2015 [77] | Mononuclear cells | Res (two doses) (post- vs. pre-) | Res | - | - | (NC) FXN (dose 1) (NS↓) FXN (dose 2) |

NR | (NC) FXN in PBMC | Effect on the neurodegenerative disease (Friedreich ataxia) |

| Olesen J et al., 2014 [75] | Skeletal muscle | Res (post- vs. pre-; T vs. C) |

Res | - | - | (NC) PPARGC1A, TNF, NOS2 | NR | (NC) TNF, iNOS in muscle and plasma |

Metabolic and inflammatory status |

| Yoshino J et al., 2012 [73] | Skeletal muscle and adipose tissue | Res (post- vs. pre-; T vs. C) |

Res | - | - | (NC) SIRT1, NAMPT, PPARGC1A, UCP3 | NR | NR | Metabolic effects |

| Poulsen MM et al., 2013 [74] | Skeletal muscle and adipose tissue | Res (post- vs. pre-) | Res | - | Muscle SLC2A4 |

Muscle (NC) PPARGC1A Adipose (NC) TNF, NFKB1 |

NR | NR | Metabolic and inflammatory effects |

1 White blood cells or Leukocytes: mononuclear cells agranulocytes (lymphocytes and monocytes) and polymorphonuclear granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, mast cells). Table abbreviations (in alphabetical order): β-car, β-carotene; HTyr, hydroxytyrosol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Lut, lutein; Med, Mediterranean; NC, no change; NR, not reported; NS, not significant; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acids; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; post-, after treatment; pre-, baseline or before treatment; Res, resveratrol; SFGluc, sulphoraphane glucosinolates; Tyr, tyrosol; VitC, vitamin C. Genes nomenclature from GeneCards [92] (in alphabetical order): ABCA1, ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 1; ABCG1, ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 1; ACE, angiotensin I converting enzyme; ADRB2, adrenoceptor beta 2; ADGRE1, adhesion G protein-coupled receptor E1 (alias: EMR1); ALOX5AP, arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase activating protein; ARHGAP15, rho GTPase activating protein 15; CAT, catalase; CCL2, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (alias: MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein 1); CCL3, C-C motif chemokine ligand 3; CCND1, cyclin D1; CD36, CD36 molecule; CD40LG, CD40 ligand; CDKN1A, cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (alias: p21); CXCL8, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 (alias: IL8); CXCR1, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 1; CXCR2, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (alias: IL8RA); CYBB, cytochrome B-245 beta chain (alias: NOX2, GP91-Phox); ECE2, endothelin converting enzyme 2; EGR1, early growth response 1; EMR1, FXN, frataxin, Friedreich ataxia protein; GCLC, glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (alias: γGCL); GPX1, glutathione peroxidase 1; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; GSTA1, glutathione S-transferase alpha 1; GSTA4, glutathione S-transferase alpha 4; GSTK1, glutathione S-transferase kappa 1; GSTM1, glutathione S-transferase Mu 1; GSTM2, glutathione S-transferase Mu 2; GSTM3, glutathione S-transferase Mu 3; GSTM4, glutathione S-transferase Mu 4; GSTM5, glutathione S-transferase Mu 5; GSTO1, glutathione S-transferase omega 1; GSTO2, glutathione S-transferase omega 2; GSTP1, glutathione S-transferase Pi 1; GSR, glutathione-disulfide reductase (alias: GRD1); HBG1, hemoglobin subunit gamma 1; HMOX1, heme oxygenase 1 (alias:HO-1); HNMT, histamine N-methyltransferase; ICAM1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; ID3, inhibitor of DNA binding 3, HLH protein; IFNG, interferon gamma; IL1B, interleukin 1 beta; IL6, interleukin 6; IL7R, interleukin 7 receptor; IL8, interleukin 8; IL10, interleukin 10; IL23A, interleukin 23 subunit alpha; INMT, indolethylamine N-methyltransferase; JUN, jun proto-oncogene, AP-1 transcription factor subunit; LPL, lipoprotein lipase; LRRFIP1, LRR binding FLII interacting protein 1; MED1, mediator complex subunit 1 (alias: PPARBP); MGST1,microsomal glutathione S-transferase 1; MGST2, microsomal glutathione S-transferase 2; MGST3, microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3; MPO, myeloperoxidase; MYC, MYC proto-oncogene, BHLH transcription factor; NAMPT, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase; NFKB1, nuclear factor kappa B subunit 1; NFKBIA, NFKB inhibitor alpha; NQO1, NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1; NQO2, N-ribosyldihydronicotinamide: quinone reductase 2; NOS2, nitric oxide synthase 2 (alias: iNOS); NR1H2, nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group H member 2; NUDT1, nudix hydrolase 1; OGG1, 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase; OLR1, oxidized low density lipoprotein receptor 1; POLK, DNA polymerase kappa; PPARA, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha; PPARD, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor delta; PPARG, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma; PPARGC1A, PPARG coactivator 1 alpha (alias: PGC1α); PTGS1, prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 (alias: COX1); PTGS2, prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (alias: COX2); PTPN1, protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 1 (alias: PTP1B); SCARB1, scavenger receptor class B member 1 (alias: SRB1); SERPINE1, Serpin Family E Member 1; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; SLC2A4, solute carrier family 2 member 4 (alias: GLUT4); SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1 (alias: Cu/ZnSOD); SOD2, superoxide dismutase 2 (alias: MnSOD); TNF, tumor necrosis factor (alias: TNFα); TNFSF10, TNF Superfamily Member 10; TXNRD1, thioredoxin reductase 1 (alias: TR1); UCP3, uncoupling protein 3; VCAM1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; VEGFB, vascular endothelial growth factor B. Orange color: upregulated genes; green color: downregulated genes.

A total of eight clinical trials that investigated the effects of the consumption of olive oil products containing bioactive compounds (polyphenols) were included in this review. These studies focused on the potential benefits of olive oil bioactives on energy metabolism, such as the regulation of the levels of cholesterol [31,34], and on inflammatory related processes [27,30,64] as well as in the concurrent regulation of the expression levels of specific genes related with these processes. The accumulated evidence to support any of these genes as specific gene targets responsive to the intake of the olive bioactives is still very limited although some of those genes display preliminary consistent changes following the consumption of these products. For example, the gene ADRB2 was found to be downregulated in mononuclear cells in three separate trials comparing the intake of olive oil containing high vs. low doses of polyphenols [28,30,35]. Also, the transcription factor EGR1 which regulates the transcription of numerous inflammatory related interleukins and cytokines [95], or the IL7R were found downregulated in mononuclear cells in response to high-polyphenol olive oil and olive leaf extract [27,28,30,64] supporting the anti-inflammatory effects attributed to these products. On the other hand, the changes in the expression levels reported for other targets such as the chemokine CCL2 were found to be reduced in mononuclear cells following 21 days of intervention with olive oil polyphenols [30] as opposed to the induction reported in adipose tissue after 4 h of the intake of mix olive oil bioactive compounds or the lack of effect detected in the same adipose tissue after 28 days consuming the olive oil bioactive compounds [36]. PTGS2 (also designated as COX2 and critically involved in the anti-inflammatory response) was found downregulated following intervention with olive leaf polyphenols in mononuclear cells [64] but no significant change was detected in studies conducted with olive oil polyphenols [27,31]. Regarding the specific bioactive compounds present in the olive products, Tyr and derived metabolites (HTyr) have been investigated and reported as some of the molecules potentially responsible for some of the gene expression effects observed in humans. The upregulation of the membrane transporter ABCA1 has been related with the increase of the levels of HTyr in plasma [31], or the downregulation of IFNG or OLR1 have been associated with the increase of Tyr in urine [28,30].

Among the six intervention studies conducted with broccoli, the richest source of SFGluc, five trials examined and reported the effects of this type of product in the expression of HMOX1. The results were diverse with three studies giving significant evidence of the upregulation of this gene in blood [26], in polymorphonuclear granulocytes [23], and in nasal lavage cells [22] whereas in the remaining two studies, no change was detected in blood [25] or in mononuclear cells [24]. In all these intervention trials, the main bioactive compound to which the effects might be potentially attributed to was the SFGluc but, we found no evidence of the presence of SFGluc metabolites in the biological samples in association with the specific gene responses. The overall accumulated evidence in humans of the gene regulatory effects of SFGluc from broccoli remains limited.

The last group of bioactive-containing products gathered in Table 4 refers to studies conducted with grape derived powders and extracts, to which anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and metabolic benefits have also been attributed to. Some of the gene expression changes reported in humans after intervention with these grape extracts shows downregulation effects in various interleukins and in the multifunctional pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF [49,51]. In this latter study, the downregulation of TNF has been associated with the presence of Res in the grape extract [51]. Grape products are characterized by containing mix flavonoids, but it has received special attention for the presence of Res, a widely investigated stilbenoid with many reported beneficial effects [96]. We have also gathered in Table 4 several human trials in which the test product was the single compound Res. None of these studies reported significant gene expression changes except for the downregulation of the glucose transporter SLC2A4 in muscle tissue [74]. Of note, two studies reported the absence of effect on TNF in skeletal muscle [75] and in adipose tissue [74]. Equally, two other studies reported the lack of effect on the expression levels of the deacetylase SIRT1 [73,78], a well-established target of Res in pre-clinical models [97].

6. General Discussion

In this review, we have thoroughly examined 75 human clinical intervention studies published in the past 20 years that investigated the health benefits of the intake of different bioactive compounds or of foods or food products containing these compounds, and that included the study of the changes promoted in specific gene targets in different cells and tissues using RT-qPCR. In general, there was a poor quality in the design and description of the experimental protocols as well as in the analysis and reporting of the gene expression changes posing doubts about the consistency and validity of the published results. A similar scenario was illustrated for biomedical research [12] reinforcing the need to apply the MIQE guidelines and well-established recommendations for RT-qPCR analyses [11,13] to enhance the quality of future gene expression studies. We have compiled in Table 5 some of the most critical experimental inaccuracies found in the human intervention studies reviewed here, in parallel with some general recommendations that should be necessarily implemented in order to produce more reliable gene expression results that could be truly attributed to the intake of dietary bioactive compounds. On the basis of this Table, we suggest the feasibility of establishing a quality score system that would define the validity and sufficiency of the human trials investigating gene expression responses to intervention with dietary bioactive compounds, with a maximum score for those studies implementing all the points proposed here, i.e., best study design, good sample population description (even at individuals levels), good placebo-control and intervention groups that allow for the attribution of the effects to the intake of specific compound(s), thorough application of the MIQE guidelines for the RT-qPCR analyses, good comparative strategy and clarity of results presentation, assessment of interindividual variability, parallel bioavailability studies that allow for potential association between gene expression changes and the presence of specific compound(s) and/or derived metabolite(s) in the analyzed biological samples, and last, but not least, potential confirmation of the gene changes at the level of protein amounts and/or activity.

Table 5.

General recommendations to further enhance the quality and relevance of future intervention trials looking at the effects on gene expression of dietary bioactive compounds in humans.

| Specific critical issues related to the human gene expression studies revised in this article that need improvement | Strategies to improve the quality of the studies and the level of evidence to support the link between gene response-bioactive compound |

|---|---|

| Human clinical trial design | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| qRT-PCR experimental protocols | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Data comparison and presentation | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Other relevant information needed to prove the relationship between the intake of bioactive compounds and gene expression changes and to increase the level of evidence supporting these molecular changes as a responsive mechanism underlying the health benefits of bioactive compounds in humans | |

|

|

|

|

|

|