Abstract

We comprehensively investigated the biodiversity of fungal communities in different developmental stages of Trypophloeus klimeschi and the difference between sexes and two generations by high throughput sequencing. The predominant species found in the intestinal fungal communities mainly belong to the phyla Ascomycota and Basidiomycota. Fungal community structure varies with life stage. The genera Nakazawaea, Trichothecium, Aspergillus, Didymella, Villophora, and Auricularia are most prevalent in the larvae samples. Adults harbored high proportions of Graphium. The fungal community structures found in different sexes are similar. Fusarium is the most abundant genus and conserved in all development stages. Gut fungal communities showed notable variation in relative abundance during the overwintering stage. Fusarium and Nectriaceae were significantly increased in overwintering mature larvae. The data indicates that Fusarium might play important roles in the survival of T. klimeschi especially in the overwintering stage. The authors speculated that Graphium plays an important role in the invasion and colonization of T. klimeschi. The study will contribute to the understanding of the biological role of the intestinal fungi in T. klimeschi, which might provide an opportunity and theoretical basis to promote integrated pest management (IPM) of T. klimeschi.

Keywords: Trypophloeus klimeschi, life stages, intestinal fungal, fungal communities, integrated pest management

1. Introduction

According to current statistics, more than 10% of insects in nature interact with symbiotic microorganisms [1]. The interaction between symbiotic fungi and bark beetles has also been studied extensively [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The vast majority of bark beetles are closely related to symbiotic fungi at various stages of development, and some bark beetles directly use the fungal fruiting bodies or fungal hyphae colonized in the gallery as a food source [2,8]. A variety of symbiotic fungi, from the microecological point of view of the bark beetles, make the larvae more advantageous than other xylophagous insects. The bark beetles use intestinal microbiotas to improve the utilization of plant carbon and nitrogen nutrition, which is more difficult for insects to decompose, thereby improving the constraints of the bark beetles on overcoming the nutrient-poor factors of food sources and ensuring their development and reproduction [9,10,11]. Trypophloeus klimeschi Eggers (Coleoptera, Curculionidae, Scolytinae) was first recorded in the Kyrgyz Republic, which borders Xinjiang Province in China [12]. Following an outbreak in 2003 in Xinjiang Province, T. klimeschi spread rapidly to the adjacent areas. The widespread outbreak of this beetle has caused huge economic, ecological, and social losses in China’s northwest shelter forest. The insect is now found in Dunhuang, where it has been identified as T. klimeschi by morphology [12,13]. This is the first systematic survey of fungal communities across the life cycle of T. klimeschi. The previous research on the intestinal fungal diversity of insects was conducted mainly through traditional methods such as culture separation and morphological identification [14]. This provides an important basis for the composition and species diversity of insect gut fungal, but it is inevitably incomplete in the description of insect gut microbes. According to statistics, approximately 99% of the microorganisms in nature are not culturable [15], but molecular biology technology can make up for this limitation. Molecular biology methods allow for the subsequent sequencing and analysis of the DNA to characterize fungal species composition and abundance [16].

There have been many reports on the research of intestinal micro-organisms with bark beetles, such as the intestinal microflora of some bark beetles showed differences in different geographic environment [17,18]. However, there are few studies on the differences in the entire development stage of the bark beetles, including difference in sexes. Recently, the symbiotic relationship between insects and their intestinal microbiota has attracted widespread attention from scholars around the world. Studies have shown that symbiotic microbes play a very important role in the invasion, settlement, spawning, development, reproduction, and other roles in developmental and life cycle stages of bark beetles [19,20,21,22]. Concurrently, a better understanding of the symbiosis formed by an insect and its colonizing microorganisms could be useful to improve insect control, use and development [17,23]. Through clarifying the composition of insect gut fungi, scientists can further study the role of gut fungi in the host physiology.

High throughput sequencing technology is used to study the fungal community structure and diversity dynamics at different developmental stages, different generations, and between T. klimeschi adult males and females. The results reveal the interaction between symbiotic microorganisms and T. klimeschi and provide a theoretical basis for the development of new biological control technologies.

2. Results

2.1. Overview of Sequencing Analysis

The proportion which equaled the number of high quality sequences/valid sequences was over 97% in each development stage (Table 1). Briefly, raw sequencing reads with exact matches to the barcodes were assigned to respective samples and identified as valid sequences. The low-quality sequences were filtered through the following criteria: sequences that had a length of <150 bp, sequences that had average Phred scores of <20, sequences that contained ambiguous bases, and sequences that contained mononucleotide repeats of >8 bp. Following sequence trimming, quality filtering, and removal of chimeras, the number of sequences per sample (overwintering mature larval, overwintering female adult, overwintering male adult, neonate larvae, mature larvae, female adult, and male adult) was 41,015 ± 2088, 47,239 ± 2773, 43,208 ± 1023, 45,476 ± 1562, 46,214 ± 1804, 45,491 ± 2324, 43,728 ± 1163, respectively. The rarefaction curves indicated that species representation in each sample approached the plateau phase, and it was unlikely that more fungi would be detected with additional sequencing efforts (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Sequences generated before and after quality filter.

| Sample | High Quality Sequences | Valid Sequences | High Quality Sequences/Valid Sequences (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| overwintering mature larvae | 41,015 ± 2474 | 42,304 ± 1921 | 97 |

| overwintering female adult | 46,744 ± 2433 | 48,111 ± 3367 | 98 |

| overwintering male adult | 42,786 ± 1073 | 43,667 ± 957 | 99 |

| neonate larvae | 45,228 ± 1564 | 46,470 ± 1545 | 98 |

| mature larvae | 46,150 ± 1806 | 46,540 ± 1846 | 98 |

| female adult | 45,388 ± 2334 | 46,135 ± 2491 | 99 |

| male adult | 43,632 ± 1167 | 44,336 ± 997 | 99 |

Figure 1.

The rarefaction curve in each sample (Note: OTU: Operational Taxonomic Unit).

2.2. The Diversity and Community Structure of Fungal Diversity in Different Development Stages of T. klimeschi

2.2.1. Fungal Diversity in Different Development Stages

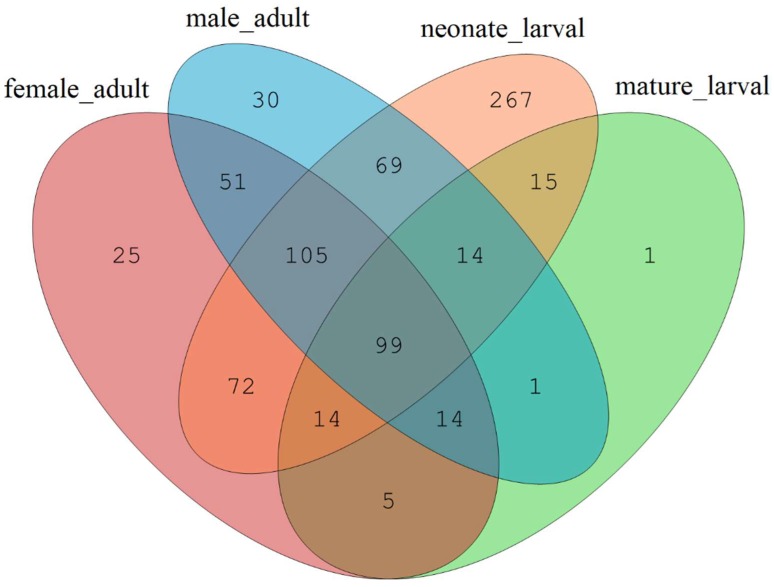

T. klimeschi undergoes complete metamorphosis: larvae and adults differ greatly in form and function. This study divided the relatively long larval stage into neonate larval and mature larval stages. The high-quality sequences were clustered into different OTUs (Operational Taxonomic Units) by the UPARSE pipeline at a 3% dissimilarity level. The authors found abundant fungi persisted in all development stages of T. klimeschi but, the diversity and structure of the T. klimeschi—associated fungal community varied significantly across host development stages. A Venn diagram was used to compare the similarities and differences between the communities in different development stages (Figure 2). Subsequent to sequence standardization, the fungal community in the neonate larvae was more diverse than the community identified in the mature larvae. Fungal community richness further increased in adults. Chao and ACE (Abundance-based Coverage Estimator) index values suggested that the fungal community richness decreased from neonate larvae to mature larvae then increased from mature larvae to adult (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram representing the distribution of the fungal OTUs in different development stages of T. klimeschi.

Table 2.

Biodiversity index values of T. klimeschi in different development stages.

| Chao 1 | ACE | Simpson | Shannon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonate larval | 354.667 ± 102.627 a | 352.667 ± 102.627 a | 0.870 ± 0.050 a | 4.993 ± 0.532 a |

| Mature larval | 92.333 ± 14.154 c | 92.457 ± 13.940 c | 0.781 ± 0.001 c | 3.331 ± 0.791 c |

| Female adult | 243.667 ± 13.796 ab | 240.667 ± 13.796 ab | 0.821 ± 0.070 ab | 4.032 ± 0.690 ab |

| Male adult | 221.667 ± 76.788 b | 221.667 ± 96.308 b | 0.800 ± 0.031 b | 3.811 ± 0.149 b |

| F | 9.293 | 8.974 | 4.322 | 10.136 |

| df | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| P | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.046 | 0.007 |

The data represent the mean ± standard deviation. Different small letters indicated significant difference between sites for that parameter. Means compared using one-way ANOVA, within each group, bars with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05 level.

2.2.2. Fungal Community Composition and Structure Succession Analysis

To identify gut fungal community structure succession in different development stages, the ITS (Internal Transcribed Spacer) sequences were classified at the phylum, class, order, and family levels. The taxonomic analysis of sequences revealed that the most prevalent phylum in all development stages was Ascomycota (69.933 ± 13.828% of the sequence) and Basidiomycota (6.152 ± 7.928% of the sequence). There were notable trends and changes in the relative abundance of the different fungi taxa in different development stages (Figure 3a). The relative abundances of Ascomycota were significantly decreased after eclosion (ANOVO: F = 4.850, df = 3, p = 0.033). Basidiomycota were richer in neonate larval than during other life stage (ANOVO: F = 4.751, df = 3, p = 0.035).

Figure 3.

Fungal community structure variation in different development stages of T. klimeschi at the phylum level and the genus level. (a) phylum level; (b) genus level.

2.2.3. Clustering Patterns of Samples in Different Development Stages

The authors compared community structures between samples using Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) that revealed the development pattern in each life stage for the unweighted and weighted UniFrac distances (Figure 4). According to the unweighted UniFrac NMDS, neonate larvae and mature larvae formed a unique cluster, separated from the adults. According to principal coordinates (NMDS1 and NMDS2), the differences in fungal communities were great between neonate larvae, mature larvae and adults, while the differences were small in adult females compared with adult males. According to the weighted UniFrac NMDS, the neonate larval, mature larval and adults were separated and clustered based on NMDS1and NMDS2.

Figure 4.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling analysis of the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index of the fungal community OTUs (≥97% identity) in different development stages of T. klimeschi based on Illumina sequencing of ITS genes. (a) Unweighted; (b) Weighted.

2.2.4. Differences Between Samples in Different Development Stages

Differences in the community composition among different development stages were tested using the Duncan’s test for multiple comparisons. The genera Nakazawaea, Trichothecium, Aspergillus, Didymella, and Villophora which belonged to the Ascomycota; and Auricularia which belonged to Basidiomycota were more prevalent in the larvae samples (p ≤ 0.05). Nakazawaea, Aspergillus, Villophora, and Auricularia were abundant and active in neonate larvae, while Trichothecium and Didymella significantly increased in mature larvae (p ≤ 0.05). Adults harbored high proportions of Graphium which belonged to Ascomycota (p ≤ 0.05). The author also found Fusarium, which belonged to Ascomycota, persisted through metamorphosis and did not have a significant change in relative content (p > 0.05). Furthermore, Fusarium was the most abundant genus in different development stages (Figure 3b) (See Table A1 in Appendix A).

2.3. The Diversity and Community Structure of Fungal Diversity in Different Generations

2.3.1. Fungal Diversity in Different Generations

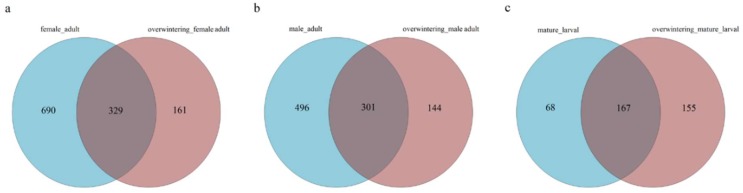

Due to the significant environmental differences between the two generations, the authors quantified the composition and structure of gut fungal communities of the first generation and overwintering generation. The high-quality sequences were clustered into different OTUs by the UPARSE pipeline at a 3% dissimilarity level. A Venn diagram was used to compare the similarities and differences between the communities in different generations (Figure 5). Chao and ACE index values suggested that there were significant differences in the fungal community richness between the two generations in larvae. This trend was also true for Simpson and Shannon index values (Table 3). The fungal community in larvae of the overwintering generation was more diverse than the community identified in larval of the first generation. However, there were no significant differences of the fungal community richness in adults between two generations.

Figure 5.

Venn diagram representing the distribution of the fungal OTUs in different generations of T. klimeschi. (a) Adult females vs. overwintering adult females; (b) adult males vs. overwintering adult males; (c) mature larvae vs. overwintering mature larvae.

Table 3.

Biodiversity index values of T. klimeschi in different generations.

| Chao 1 | ACE | Simpson | Shannon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female adult | 280.000 ± 12.124 | 280.000 ± 12.124 | 0.737 ± 0.034 | 2.997 ± 0.248 |

| Overwintering female adult | 497.027 ± 235.154 | 497.303 ± 235.623 | 0.842 ± 0.037 | 4.940 ± 1.089 |

| T | 1.675 | 1.674 | 2.720 | 3.352 |

| df | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| p | 0.236 | 0.236 | 0.113 | 0.079 |

| Male adult | 243.000 ± 91.099 | 243.000 ± 91.099 | 0.707 ± 0.150 | 2.897 ± 0.916 |

| Overwintering male adult | 407.667 ± 19.757 | 407.667 ± 19.757 | 0.862 ± 0.028 | 4.300 ± 0.335 |

| T | 2.607 | 2.607 | 1.532 | 1.947 |

| df | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| p | 0.121 | 0.121 | 0.265 | 0.191 |

| Mature larval | 236.320 ± 9.269 | 239.730 ± 10.922 | 0.819 ± 0.006 | 3.230 ± 0.036 |

| Overwintering mature larval | 167.333 ± 19.218 | 167.333 ± 19.218 | 0.570 ± 0.087 | 2.240 ± 0.195 |

| T | 10.643 | 9.199 | 5.127 | 8.606 |

| df | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| p | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.036 | 0.013 |

The data represent the mean ± standard deviation. Means compared using t-test.

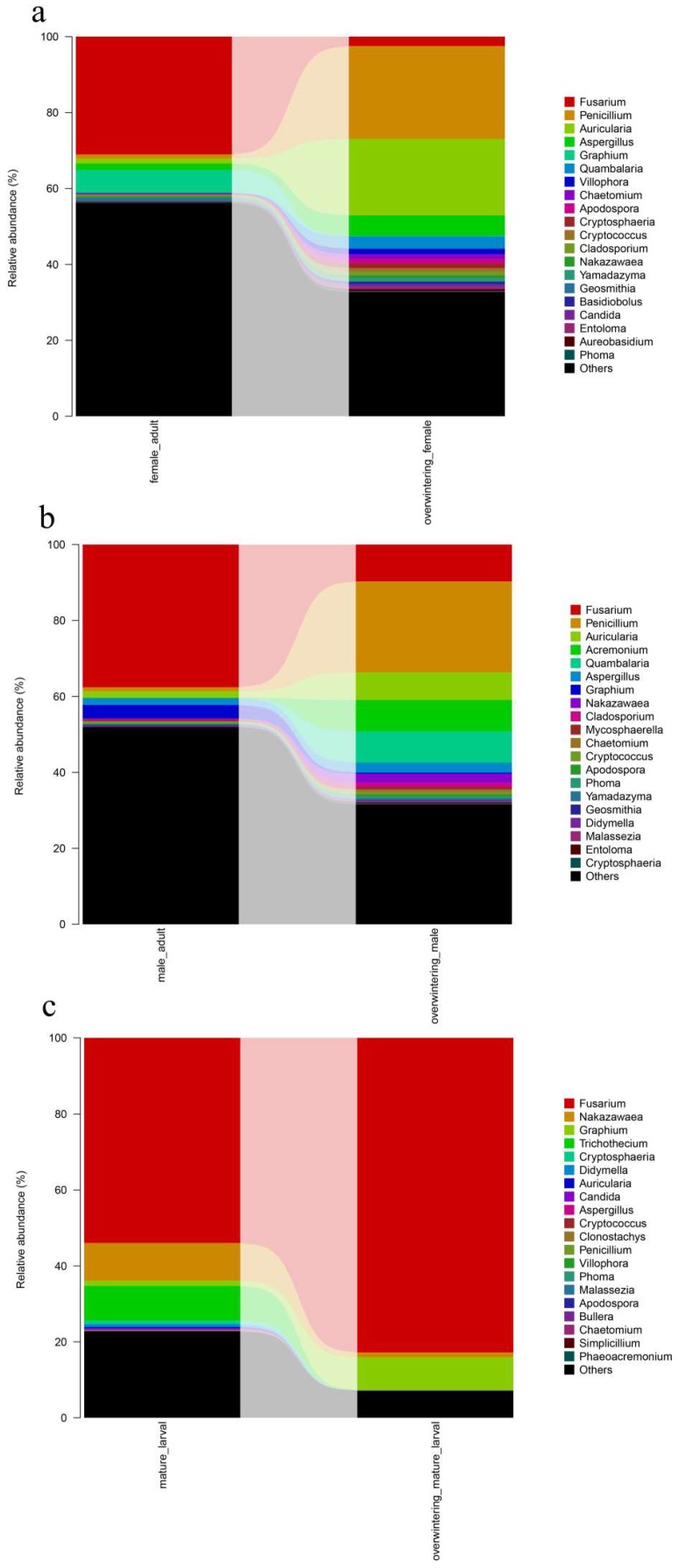

2.3.2. Fungal Community Composition and Structure Succession Analysis

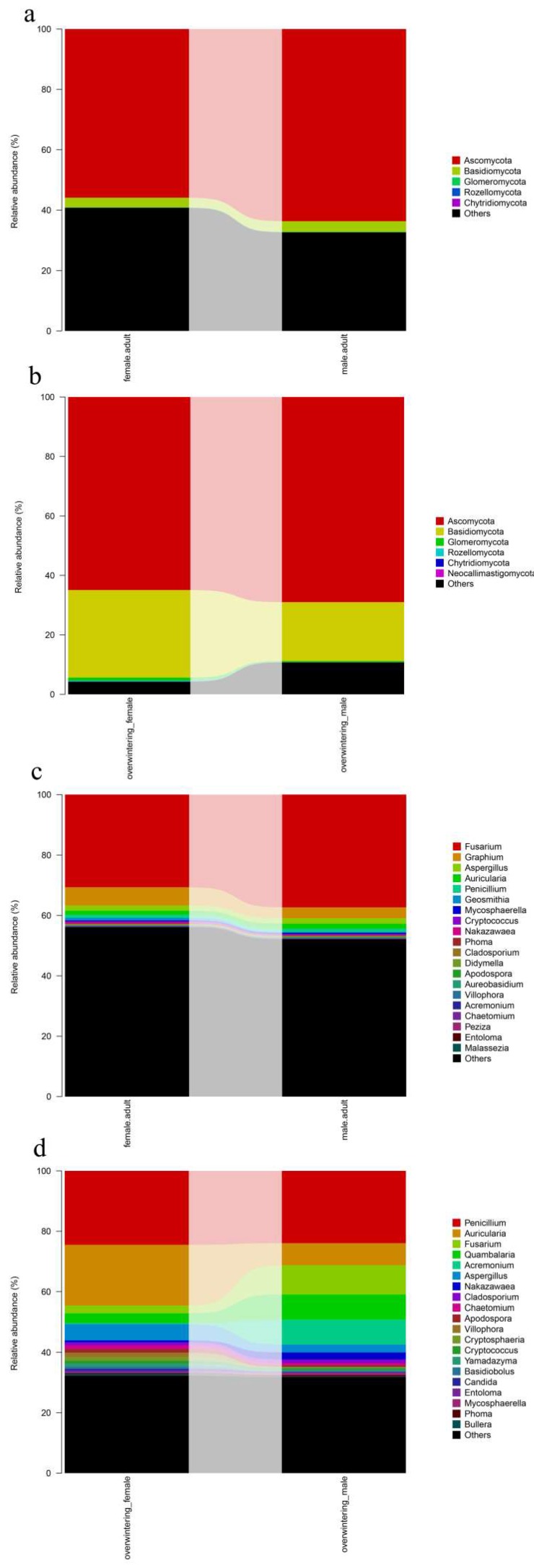

To identify gut fungal community structure succession in different generations, the ITS sequences were classified at the phylum, class, order, and family levels. There were notable trends and changes in the relative abundance of the different fungal taxa in different generations (Figure 6). The relative abundance of Ascomycota was significantly increased in the overwintering generation (p ≤ 0.05). (See Table A2 in Appendix A).

Figure 6.

Fungal community structure variation in different generations of T. klimeschi at the phylum level. (a) Adult females vs. overwintering adult females; (b) adult males vs. overwintering adult males; (c) mature larvae vs. overwintering mature larvae.

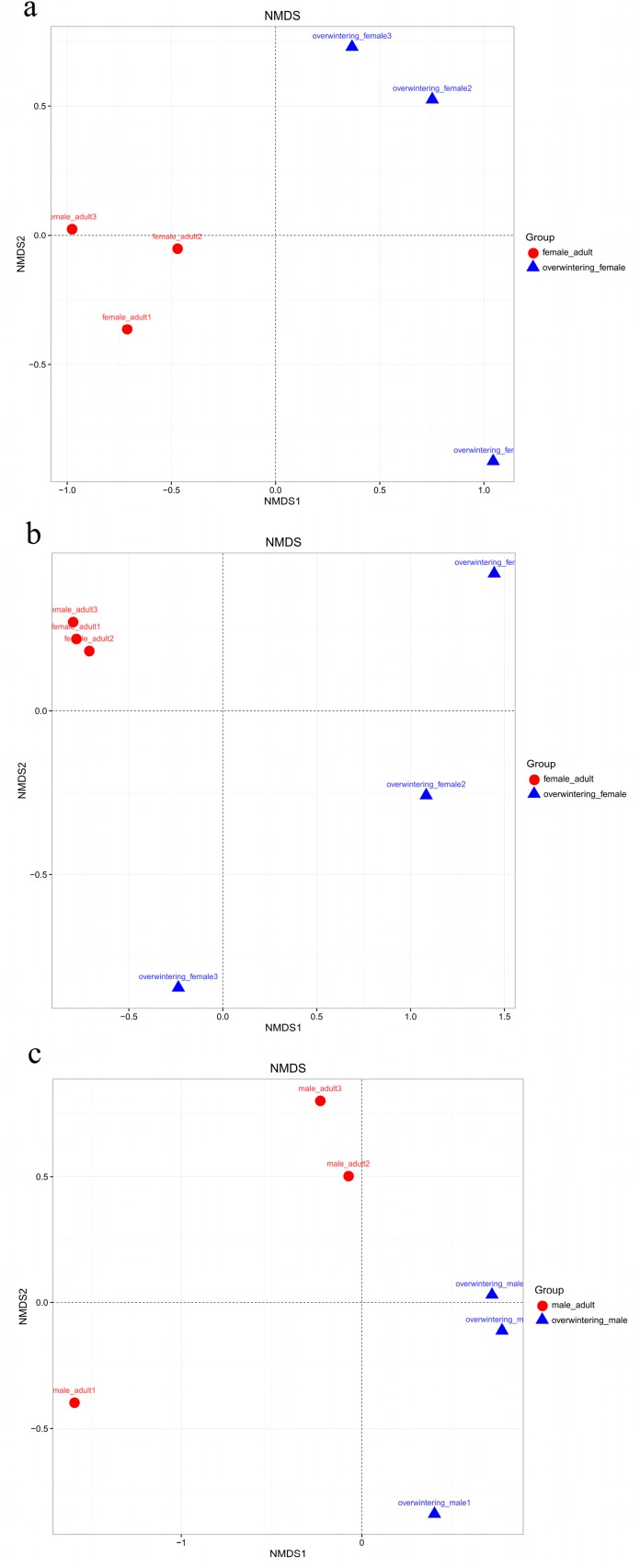

2.3.3. Clustering Patterns of Samples in Different Generation

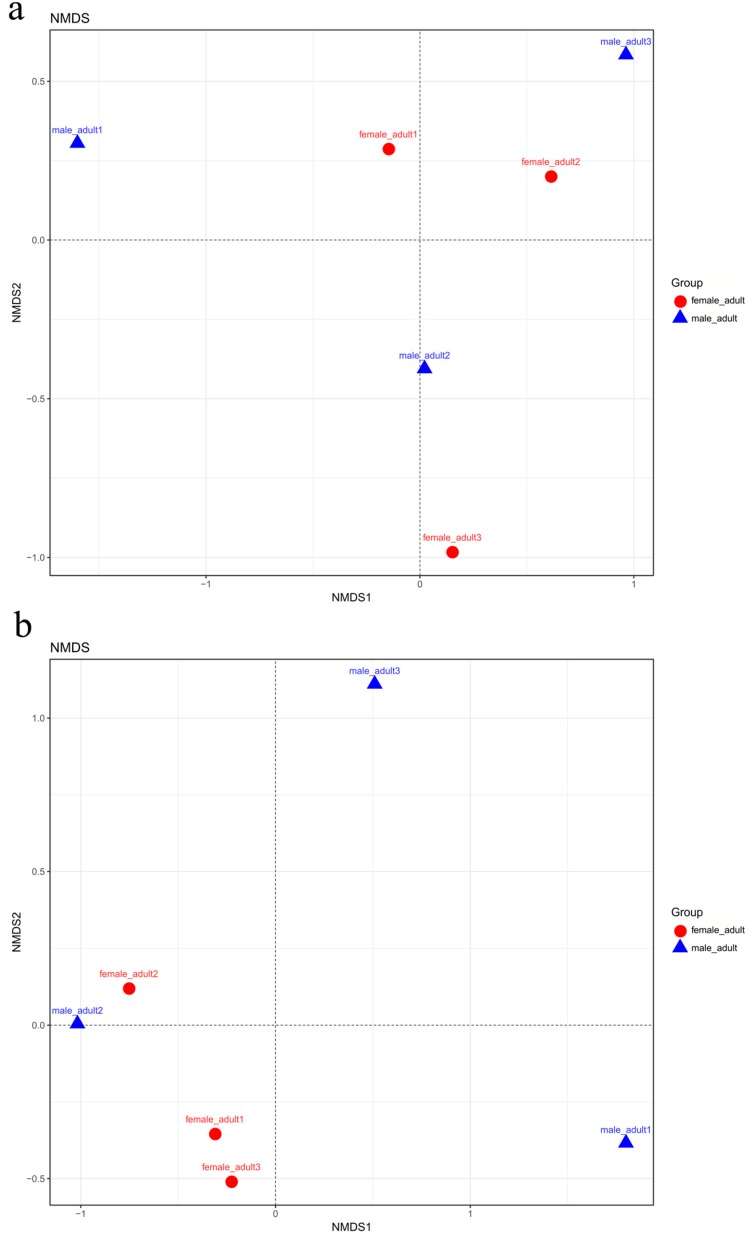

The authors compared community structures between samples using NMDS that revealed the development pattern in different generations for the unweighted and weighted UniFrac distances (Figure 7A,B). According to the unweighted UniFrac NMDS, the overwintering generation formed a unique cluster, separated from the first generation. According to principal coordinates (NMDS1 and NMDS2), the differences in fungal communities were great between the overwintering generation and first generation. This trend was also true for the weighted UniFrac NMDS.

Figure 7.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling analysis of the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index of the fungal community OTUs (≥97% identity) in different generations of T. klimeschi based on Illumina sequencing of ITS genes. Adult females vs. overwintering adult females: (a) Unweighted; (b) Weighted; adult males vs. overwintering adult males: (c) Unweighted; (d) Weighted; mature larvae vs. overwintering mature larvae: (e) Unweighted; (f) Weighted.

2.3.4. Differences Between Samples in Different Generations

Differences in the community composition among different generations were tested using the Duncan’s test for multiple comparisons. The diversity and composition of the T. klimeschi-associated fungal community varied substantially between the two generations. Regarding adults, Aspergillus, which belonged to the Ascomycota, was significantly increased in the overwintering generation (p ≤ 0.05). The pest overwintered in the form of mature larvae. The authors found that the fungal community during the overwintering stage varied substantially. Fusarium, which belongs to the Ascomycota, was significantly increased in overwintering mature larvae (p ≤ 0.05), whereas Nakazawaea, which belongs to the Ascomycota, decreased (p ≤ 0.05). Trichothecium and Cryptosphaeria were absent in overwintering mature larvae. Unidentified_Nectriaceae was only appeared in overwintering mature larvae. (Figure 8) (See Table A3 in Appendix A).

Figure 8.

Fungal community structure variation in different generations of T. klimeschi at the genus level. (a) Adult females vs. overwintering adult females; (b) adult males vs. overwintering adult males; (c) mature larvae vs. overwintering mature larvae.

2.4. The Diversity and Community Structure of Fungal Diversity between Males and Females

2.4.1. Fungal Diversity in Different Sexes

Considering the difference between adult males and adult females, the internal fungal communities associated with mature adults of each sex were studied separately. A Venn diagram was used to compare the similarities and differences between the communities in different sexes (Figure 9). Chao and ACE index values suggested that there were no significant differences of the fungal community richness in different sexes. This trend was also true for the Simpson and Shannon index values (Table 4).

Figure 9.

Venn diagram representing the distribution of the fungal OTUs in different sexes of. (a) Adult females vs. adult males; (b) overwintering adult females vs. overwintering adult males.

Table 4.

Biodiversity index values of T. klimeschi in different sexes.

| Chao 1 | ACE | Simpson | Shannon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female adult | 432.713 ± 11.738 | 433.573 ± 12.919 | 0.792 ± 0.014. | 3.670 ± 0.145 |

| Male adult | 388.000 ± 103.697 | 388.000 ± 103.697 | 0.766 ± 0.119 | 3.590 ± 0.823 |

| T | 0.681 | 0.685 | 0.358 | 0.163 |

| df | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| P | 0.566 | 0.564 | 0.755 | 0.885 |

| Overwintering female adult | 452.710 ± 82.078 | 453.717 ± 88.444 | 0.878 ± 0.036 | 5.093 ± 1.154 |

| Overwintering male adult | 492.667 ± 70.088 | 492.667 ± 0.088 | 0.878 ± 0.046 | 4.603 ± 0.603 |

| T | 1.098 | 1.071 | 0.016 | 0.989 |

| df | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| P | 0.387 | 0.396 | 0.989 | 0.427 |

The data represent the mean ± standard deviation. Means compared using t-test.

2.4.2. Fungal Community Composition and Structure Succession Analysis.

To identify gut fungal community structure succession in different sexes, the ITS sequences were classified at the phylum, class, order, and family levels. There were notable trends and changes in the relative abundance of the different fungi taxa in different sexes (Figure 10a,b). There were no significant differences of gut fungal community between females and males (see Table A4 in Appendix A).

Figure 10.

Fungal community structure variation in different sexes of T. klimeschi at the phylum level and genus level. (a,b) Phylum level; (c,d) genus level2.4.3. Clustering Patterns of Samples in Different Sexes.

The authors compared community structures between samples using NMDS that revealed the development pattern in different sexes for the unweighted and weighted UniFrac distances (Figure 11). Samples obtained from different sexes of T. klimeschi were not scattered relatively within the NMDS plot, indicating that the fungal community structure in T. klimeschi is relatively conserved.

Figure 11.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling analysis of the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index of the fungal community OTUs (≥97% identity) in different sexes of T. klimeschi based on Illumina sequencing of ITS genes. Adult females vs. adult males: (a) Unweighted; (b) Weighted; overwintering adult females vs. overwintering adult males: (c) Unweighted; (d) Weighted.

2.4.4. Differences Between Samples in Different Sexes

Differences in the community composition among different sexes were tested using the Duncan’s test for multiple comparisons. The community structure of fungi between adult males and females were similar (Figure 10c,d) (See Table A5 in Appendix A).

3. Discussion

Although not often obvious to the naked eye, fungi are as deeply enmeshed in the evolutionary history and ecology of life as any other organism on Earth [24]. Furthermore, many data are available for relevant ecological traits such as acting as decomposers by releasing extracellular enzymes to break down various plant biopolymers and using the resulting products [25,26], or communities of endophytic fungi containing wood-decomposer fungi that are present in a latent state prior to plant death [24]. Investigation of the gut fungal community of bark-inhabiting insects is important to better understand the potential role of gut microorganisms in host nutrition, cellulose/hemicellulose degradation, nitrogen fixation, and detoxification processes. Additionally, microbes in the beetle’s intestine have proven to be an important source of enzymes for various industries [27]. The authors not only conduct fungal inventories of T. klimeschi across the full host life cycle, but also compare the differences in the community composition in different generations and each sex, which provides new insights into the metabolic potentials of Curculionidae-associated fungal communities. However, not all active fungi could be successfully detected and identified inside the host.

The predominant species found in the intestinal fungal communities of T. klimeschi formed a group of low complexity, mainly belonging to the phyla Ascomycota and Basidiomycota. A low level of fungal community complexity is typical of the bark beetle gut discovered to date, except in the fungus-feeding beetles [17,28,29]. The presence and high abundance of these fungal phyla have been previously reported in the gut of larvae from several Coleoptera [30,31,32,33].

However, the structure of the fungal community differed depending on the developmental stages. The fungal community in the neonate larvae was more diverse than the community identified in the mature larvae. Fungal community richness further increased in adults. Since the neonate larvae of T. klimeschi feed on inner bark and the gallery contain almost entirely excrement, the living habits were similar to Trypophloeus striatulus [34]. Such behavior might contribute to maintaining gut fungal community in the neonate larvae stage. It has been documented that the prepupal larvae of T. striatulus evacuate their gut [34]. This phenomenon implies that gut fungal community might be re-structured in the subsequent developmental stages of the life cycle. Furthermore, micro-environments were different between larvae and adults. Moreover, this difference in taxonomic membership might reflect different functional roles across certain life stages. Some fungal taxa guide the entrance point for gallery construction, such as Trypophloeus striatulus possibly attraction to odor emitted through lenticels that overlie susceptible Cytospora-infested phloem [34].

Fusarium was the most abundant genus and was conserved in all development stages. This result indicates that the conserved fungal community of shared fungal taxa should be well adapted to T. klimeschi. It was interesting that Fusarium species (Ascomycota, Nectriaceae) are among the most diverse and widespread plant-infecting fungi, and numerous metabolites produced by Fusarium spp. are toxic to insects [35,36]. The Tenebrio molitor larvae were able to use the wheat kernels that were colonized by Fusarium proliferatumor and Fusarium poae which produced fumonisins, enniatins, and beauvericin during kernel colonization without exhibiting increased mortality. The result suggests that Tenebrio molitor can tolerate or metabolize those toxins. Some insect species appear to benefit from the presence of aflatoxin producers [37,38] or mycotoxin produced by Fusarium spp. fungi [39]. The authors have not investigated induced reactions of Fusarium fungi to the presence or feeding of T. klimeschi, this will be the subject of subsequent studies.

The genera Nakazawaea, Trichothecium, Aspergillus, Didymella, and Villophora which belonged to the Ascomycota; and Auricularia which belonged to Basidiomycota were more prevalent in the larvae samples.

Nakazawaea is the ascomycete yeast genus, derived from the genus Pichia [40]. Yeasts are frequently isolated from the larvae of bark beetles [41,42]. Additionally, Nakazawaea is widely distributed in nature and common to insects that bore into forest trees [43,44,45]. Yeasts are commonly associated with bark beetles and might be an important nutritional source for the insect host [28,46]. Moreover, yeasts such as the Candida species can assimilate nutrients such as nitrate, xylose, and cellobiose [47]. Nutritional needs should be different over the developmental stages of the beetle, as the beetle needs nutritional benefits to accomplish different steps in its life style, such as development and ovogenesis [48]. The high prevalence of yeasts associated with the larvae supports the hypothesis that yeasts are essential nutritional elements for the development of the T. klimeschi. Trichothecium has shown potential for biotransformation and enzyme production [49]. Found in several wood-feeding Coleptera larvae, Trichothecium was the most abundant genus as well [33]. There are few reports about Aspergillus interaction with insects; perhaps it plays the same role as the genus Fusarium. Auricularia are typical wood-inhabiting fungi in the forest ecosystem. They can degrade cellulose, hemicelluloses, and ligini of wood [50]. Some wood-inhabiting fungi provide foods and breeding grounds for some beetles [51,52]. Similar to termites [53], T. klimeschi also feeds on plant tissue lacking nitrogen nutrients. Some studies have reported that the mycelium of Auricularia could improve the quality of termite foods and increase egg production by termites [54].

According to this study’s results, the fungal community in the neonate larvae was more diverse than the community identified in other development stages. Considering that the digestive system of the neonate larvae was just maturing, ingesting large amounts of carbon and nitrogen nutrition associated with their symbiotic microorganisms explains why the guts of neonate larvae contained more diverse fungal communities. Overall, these fungi are all relevant to nutritional metabolism. The authors speculate that these fungal symbionts might play important roles in nutrition in T. klimeschi.

Adults harbored high proportions of Graphium, which belongs to Ascomycota. The genus Graphium is known as ‘blue stain fungi’ [55]. When bark beetles invade conifers, the fungus taps into the sapwood nitrogen and transports it to the phloem where the beetle feeds, increasing the nitrogen content by up to 40% [56]; this is critical for bark beetle development and survival [2,9,56]. Moreover, one blue stain fungus Leptographium qinlingensis is the pathogenic fungus carried by adults of Dendroctonus armandi, which develops in the tissues and cells of xylem and phloem of Pinus armandi after D. armandi attacks healthy host trees, decomposes the secretory resin cells in resin ducts and the parenchyma cell sapwood tissues, then affects the metabolism of resin [57]. The presence of Graphium was also observed in larvae and adult beetles of Euwallacea fronicatus as well as in the galleries of several tree species [33,58]. According to the result, the authors speculate that the physiology and biochemistry resistance of P. alba var. pyramidalis was weakened and nutrient degradation was accelerated by the attacking of genus Graphium. Moreover, some fungal taxa guide the entrance point for gallery construction, such as Trypophloeus striatulus possibly attraction to odor emitted through lenticels that overlie susceptible Cytospora-infested phloem [34]. We speculated that Graphium plays an important role in the invasion and colonization of T. klimeschi.

The fungal community structures found in the guts of adult females and adult males were similar, suggesting that the fungal community structure in T. klimeschi adult is conserved.

Interestingly, there was a significant difference in fungal community structure between the mature larvae and overwintering mature larvae. The pest overwintered in the form of mature larvae. Insects face great challenges in surviving at low temperatures in frigid and temperate zones [59,60,61]. Insects’ cold-tolerance capacity is a dominant factor that affects their adaption to the geographical environment [62,63]. The present results suggested that gut fungal community compositions differed during the overwintering period. Fusarium, which belongs to the Ascomycota, were significantly increased in overwintering mature larvae. Nectriaceae only appeared and was abundant in overwintering mature larvae. We hypothesized that the two genera are associated with the insect overwintering process and resistance to low temperatures.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Collection Site Description

The T. klimeschi were collected from the bark of infested Populus alba var. pyramidalis at the shelter belt of Dunhuang City (40°06′50.61″ N, 94°36′10.24″ E), Gansu Province, China. Dunhuang is located in Northwestern Gansu Province, which has a temperate continental, dry climate with low rainfall, high evaporation, large temperature differences between day and night, long sunshine duration, an annual average temperature of 9.4 °C, monthly average maximum temperature of 24.9 °C (July), and monthly average minimum temperature of −9.3% °C (January), extreme maximum temperature of 43.6 °C, and minimum temperature of −28.5 °C.

4.2. Life-Cycle of T. klimeschi Description

There were two generations of T. klimeschi per year and the pest overwintered in the form of mature larvae. There were two peak periods in a year. Mature larvae began to pupate in early May. Adults started to emerge beginning in mid-May, with a peak from late-May until mid-June. Second generation larvae pupated in mid-July. Adult emergence peaked in August. T. klimeschi began wintering in October (see Table A6 in Appendix A).

4.3. Insect Collection and Dissection

According to the life history of T. klimeschi, larvae and adult females and males were collected from January 2017 to August 2017. The pest overwintered in the form of mature larvae from October to May of the following year. Due to the lowest average temperature being in January, overwintering mature larvae were collected in January 2017. Adults began to emerge in mid-May with a peak from late-May until mid-June. Overwintering adults were collected in May 2017. The neonate larvae of the first generation were collected in June 2017. The mature larvae of the first generation were collected in July 2017. The adults of the first generation were collected in August 2017. To identify gut fungal community structure succession in different development stages, the authors compared neonate larvae, mature larvae, adult females, and adult males. To identify gut fungal community structure succession in different generations, the authors compared adult females with overwintering adult females, adult males with overwintering adult males, and mature larvae with overwintering mature larvae. To identify gut fungal community structure succession in different sexes, the authors compared adult females with adult males and overwintering adult females with overwintering adult males.

The samples were collected at the laboratory in sterile vials. To investigate the influence of sex on gut-associated fungi, adult females and males were separated according to morphology (according to the morphological observation, the salient features distinguishing adult males and females are in the granules of the elytron: the male has three sharp corners on interstria 5 near the tail at the declivity of the left and right elytrons, and the females do not have this feature (relevant data have not been published). A total of 180 insect samples in each life stage were gathered for high-throughput sequencing analysis.

Insect samples were rinsed in sterile water, surface sterilized with 70% ethanol for 3 min, and then rinsed twice in sterile water. Following being placed in 10 mM sterilized phosphate-buffered saline (138 mM NaCl and 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4) the insects were dissected under a stereomicroscope with the aid of insect pins to excise the mid-guts and hindguts [64]. Sixty guts were excised from each sample. The treatment in each sample was repeated three times.

4.4. DNA Extraction

The E.Z.N.A. Fungal DNA Kit (Omega Biotech, Doraville, GA, USA) was used to extract T. klimeschi samples guts fungal DNA following the instruction booklet. The gut fungal DNA was stored at −20 °C before using. DNA samples were mixed in equal concentrations, and the mixed DNA specimens were sent to Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for analysis by high throughput sequencing.

4.5. Bioinformatics and Statistical Analysis

Following sequencing, all reads were processed and analyzed using the QIIME package release v1.8.0 [65]. Sequences were clustered by the open-reference OTU clustering using the default settings at a 97% identity threshold. The representative ITS sequences were assigned to taxonomy using the UNITE database [66]. The alpha diversity analysis included observed species, ACE and Chao estimators, Simpson and Shannon diversity indices estimate of coverage. Rarefaction curves were generated based on observed species. According to the OTU classification and classification status identification results, the specific composition of each sample at each classification level was obtained. Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis was conducted on the sample-OTU matrix using the Bray–Curtis distances. Additionally, Venn diagrams were also created to observe the partition of the OTUs across different samples. The data differences were analyzed by SPSS (SPSS version 20.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) software.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed the structure of the gut-associated fungal communities in the different developmental stages of T. klimeschi and the difference between sexes and two generations. The current study helps gain better understanding of the evolutionary and ecological roles of gut symbionts in many important insect groups. A better understanding of the relationship between fungal symbionts and the Coleoptera host would lead to new concepts and approaches for controlling insect pests by manipulating their microbiota. The authors propose that gut-associated fungi could interfere with the development of T. klimeschi and, hence, may have potential as vectors for biocontrol agents.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The relative abundance of the different fungal taxa in different development stages of T. klimeschi at the genus level.

| Taxonomy | Neonate Larval | Mature Larval | Female Adult | Male Adult | F | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Genus | |||||||

| Ascomycota | Fusarium | 0.208 ± 0.188 | 0.544 ± 0.040 | 0.267 ± 0.092 | 0.366 ± 0.240 | 2.456 | 3 | 0.139 |

| Nakazawaea | 0.226 ± 0.175a | 0.099 ± 0.004ab | 0.004 ± 0.003b | 0.001 ± 0.001b | 4.394 | 3 | 0.042 | |

| Graphium | - | 0.014 ± 0.005b | 0.060 ± 0.035a | 0.036 ± 0.012ab | 5.822 | 2 | 0.021 | |

| Trichothecium | 0.001 ± 0.001b | 0.091 ± 0.013a | 0.000 ± 0.000b | - | 144.986 | 2 | 0.000 | |

| Aspergillus | 0.038 ± 0.015a | 0.001 ± 0.000c | 0.017 ± 0.005b | 0.018 ± 0.005b | 10.035 | 3 | 0.004 | |

| Penicillium | 0.010 ± 0.003a | 0.001 ± 0.000b | 0.011 ± 0.004a | 0.011 ± 0.002a | 10.614 | 3 | 0.004 | |

| Didymella | 0.001 ± 0.001b | 0.007 ± 0.003a | 0.002 ± 0.001b | 0.002 ± 0.002b | 5.452 | 3 | 0.025 | |

| Villophora | 0.008 ± 0.006a | 0.000 ± 0.000b | 0.001 ± 0.000b | 0.001 ± 0.001b | 5.110 | 3 | 0.029 | |

| Basidiomycota | Auricularia | 0.094 ± 0.071a | 0.040 ± 0.001ab | 0.013 ± 0.003b | 0.017 ± 0.012b | 4.072 | 3 | 0.050 |

Table A2.

The relative abundance of the different fungal taxa in different generations of T. klimeschi at the phylum level.

| Taxonomy | Female Adult | Overwintering Female Adult | T | df | p | Male Adult | Overwintering Male Adult | T | df | p | Mature Larval | Overwintering Mature Larval | T | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascomycota | 0.559 ± 0.012 | 0.649 ± 0.167 | 0.987 | 2 | 0.428 | 0.637±0.132 | 0.690 ± 0.112 | 0.646 | 2 | 0.585 | 0.777 ± 0.040 | 0.994 ± 0.005 | 9.457 | 2 | 0.011 |

| Basidiomycota | 0.032 ± 0.009 | 0.294 ± 0.131 | 3.598 | 2 | 0.069 | 0.036 ± 0.025 | 0.198 ± 0.152 | 2.004 | 2 | 0.183 | 0.013±0.007 | 0.003 ± 0.002 | 4.000 | 2 | 0.057 |

Table A3.

The relative abundance of the different fungal taxa in different generation of T. klimeschi at the genus level.

| (A) | |||||||||||||

| Taxonomy | Female Adult | Overwintering Female Adult | T | df | p | Male Adult | Overwintering Male Adult | T | df | p | |||

| Phylum | Genus | ||||||||||||

| Ascomycota | Fusarium | 0.267 ± 0.092 | 0.025 ± 0.022 | 4.254 | 2 | 0.051 | 0.366 ± 0.240 | 0.097 ± 0.131 | 4.196 | 2 | 0.052 | ||

| Penicillium | 0.011 ± 0.004 | 0.245 ± 0.196 | 2.098 | 2 | 0.171 | 0.011 ± 0.02 | 0.240 ± 0.196 | 2.043 | 2 | 0.178 | |||

| Acremonium | 0.001 ± 0.000 | 0.003 ± 0.004 | 1.037 | 2 | 0.409 | 0.001 ± 0.000 | 0.082 ± 0.123 | 1.155 | 2 | 0.367 | |||

| Aspergillus | 0.017 ± 0.005 | 0.054 ± 0.036 | 1.546 | 2 | 0.262 | 0.018 ± 0.005 | 0.026 ± 0.005 | 6.003 | 2 | 0.027 | |||

| Graphium | 0.060 ± 0.035 | 0.001 ± 0.002 | 2.817 | 2 | 0.106 | 0.036 ± 0.012 | 0.003 ± 0.005 | 3.455 | 2 | 0.075 | |||

| Basidiomycota | Quambalaria | 0.000 ± 0.000 | 0.033 ± 0.036 | 1.534 | 2 | 0.265 | 0.000 ± 0.000 | 0.083 ± 0.131 | 1.091 | 2 | 0.389 | ||

| Auricularia | 0.013 ± 0.003 | 0.201 ± 0.152 | 2.144 | 2 | 0.165 | 0.017 ± 0.012 | 0.070 ± 0.026 | 3.305 | 2 | 0.081 | |||

| (B ) | |||||||||||||

| Taxonomy | Mature Larval | Overwintering Mature Larval | T | df | p | ||||||||

| Phylum | Genus | ||||||||||||

| Ascomycota | Fusarium | 0.544 ± 0.040 | 0.828 ± 0.148 | 4.352 | 2 | 0.051 | |||||||

| Nakazawaea | 0.099 ± 0.004 | 0.013 ± 0.010 | 18.758 | 2 | 0.171 | ||||||||

| Graphium | 0.014 ± 0.005 | 0.087 ± 0.106 | 1.137 | 2 | 0.409 | ||||||||

| Trichothecium | 0.091 ± 0.013 | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| Unidentified_Nectriaceae | - | 0.056 ± 0.047 | - | - | - | ||||||||

| Cryptosphaeria | 0.010 ± 0.010 | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

Table A4.

The relative abundance of the different fungal taxa in different sexes of T. klimeschi at the phylum level.

| Taxonomy | Female Adult | Male Adult | T | df | p | Overwintering Female Adult | Overwintering Male Adult | T | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascomycota | 0.559 ± 0.012 | 0.636 ± 0.133 | 1.057 | 2 | 0.401 | 0.648 ± 0.170 | 0.691 ± 0.113 | 0.780 | 2 | 0.517 |

| Basidiomycota | 0.032 ± 0.009 | 0.035 ± 0.025 | 0.260 | 2 | 0.819 | 0.295 ± 0.132 | 0.198 ± 0.153 | 0.934 | 2 | 0.449 |

Table A5.

The relative abundance of the different fungal taxa in different sexes of T. klimeschi at the genus level.

| Taxonomy | Female Adult | Male Adult | T | df | p | Overwintering Female Adult | Overwintering Male Adult | T | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Genus | ||||||||||

| Ascomycota | Fusarium | 0.267 ± 0.092 | 0.366 ± 0.240 | 0.566 | 2 | 0.629 | 0.025 ± 0.022 | 0.097 ± 0.131 | 1.148 | 2 | 0.370 |

| Aspergillus | 0.017 ± 0.005 | 0.018 ± 0.005 | 0.212 | 2 | 0.851 | 0.054 ± 0.036 | 0.026 ± 0.005 | 1.514 | 2 | 0.269 | |

| Penicillium | 0.011 ± 0.004 | 0.010 ± 0.002 | 0.164 | 2 | 0.885 | 0.245 ± 0.196 | 0.240 ± 0.196 | 0.123 | 2 | 0.913 | |

| Graphium | 0.060 ± 0.035 | 0.036 ± 0.012 | 0.322 | 2 | 0.798 | 0.001 ± 0.002 | 0.003 ± 0.005 | 0.164 | 2 | 0.885 | |

| Acremonium | 0.001 ± 0.000 | 0.001 ± 0.000 | 0.132 | 2 | 0.911 | 0.003 ± 0.004 | 0.082 ± 0.123 | 1.101 | 2 | 0.386 | |

| Basidiomycota | Auricularia | 0.013 ± 0.003 | 0.017 ± 0.012 | 0.580 | 2 | 0.620 | 0.201 ± 0.152 | 0.070 ± 0.026 | 1.514 | 2 | 0.269 |

| Quambalaria | 0.000 ± 0.000 | 0.000 ± 0.000 | 0.126 | 2 | 0.928 | 0.033 ± 0.036 | 0.083 ± 0.131 | 0.600 | 2 | 0.609 | |

Table A6.

The life cycle of T. klimeschi.

| Month | Jan.–Apr. | Mar. | Jun. | Jul. | Aug. | Sep. | Oct. | Nov.–Dec. | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | M | L | E | M | L | E | M | L | E | M | L | E | M | L | E | M | L | E | M | L | E | M | L | |

| Overwintering generation | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| − | − | − | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||

| First generation | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ||||||||||||||||||

| − | − | − | − | |||||||||||||||||||||

| + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Overwintering generation | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | |||||||||||||||

Remarks: +: Adult; ○: Egg; ▲: Larva; −: Pupa; E: Early; M: Middle; L: late.

Author Contributions

G.G. and H.C. conceived and designed the experiments; G.G. performed the experiments; G.G. and L.D. analyzed the data; J.G. and C.H. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; G.G. wrote the paper.

Funding

We acknowledge the financial support of the Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shanxi Province of China (2017ZDJC-03), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0600104), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Z109021640).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Baumann L., Thao M.L., Funk C.J., Falk B.W., Ng J.C., Baumann P. Sequence analysis of DNA fragments from the genome of the primary endosymbiont of the whitefly bemisia tabaci. Curr. Microbiol. 2004;48:77–81. doi: 10.1007/s00284-003-4132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrington T.C., Vega F.E., Blackwell M. Ecology and evolution of mycophagous bark beetles and their fungal partners. Insect-Fungal Assoc. Ecol. Evolut. 2005;11:257–291. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirisits T. Bark & Wood Boring Insects in Living Trees in Europe a Synthesis. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2007. Fungal associates of European bark beetles with special emphasis on the Ophiostomatoid fungi; pp. 181–236. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klepzig K.D., Six D. Bark beetle-fungal symbiosis: Context dependency in complex associations. Symbiosis. 2004;37:189–205. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paine T., Raffa K., Harrington T. Interactions among Scolytid bark beetles, their associated fungi, and live host conifers. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1997;42:179–206. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Six D.L. Bark beetle-fungus symbioses. Insect Symbiosis. 2003;7:97–114. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitney H.S. Relationships between bark beetles and symbiotic organisms. Bark Beetles N. Am. Conifers. 1982;3:183–211. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams A.S., Six D.L. Temporal variation in mycophagy and prevalence of fungi associated with developmental stages of Dendroctonus ponderosae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) Environ. Entomol. 2007;36:64–72. doi: 10.1093/ee/36.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayres M.P., Wilkens R.T., Ruel J.J., Lombardero M.J., Vallery E. Nitrogen budgets of phloem-feeding bark beetles with and without symbiotic fungi. Ecology. 2000;81:2198–2210. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[2198:NBOPFB]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibson C.M., Hunter M.S. Extraordinarily widespread and fantastically complex: Comparative biology of endosymbiotic bacterial and fungal mutualists of insects. Ecol. Lett. 2010;13:223–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janson E.M., Stireman J.O., Singer M.S., Abbot P. Phytophagous insect-microbe mutualisms and adaptive evolutionary diversification. Evolution. 2008;62:997–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eggers V.O.H. Trypophloeus klimeschi nov. spec. Entomol. Blatter. 1915;25:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao Y., Luo Z., Wang S., Zhang P. Bionomics and control of Trypophloeus klimeschi. Entomol. Knowl. 2004;41:36–38. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lysenko O. Non-sporeforming bacteria pathogenic to insects: Incidence and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1985;39:673–695. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.39.100185.003325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams D., Douglas A. How symbiotic bacteria influence plant utilisation by the polyphagous aphid, Aphis fabae. Oecologia. 1997;110:528–532. doi: 10.1007/s004420050190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu H., Wang Z., Liu L., Xia Y., Cao Y., Yin Y. Analysis of the intestinal microflora in Hepialus gonggaensis, larvae using 16S rRNA sequences. Curr. Microbiol. 2008;56:391–396. doi: 10.1007/s00284-007-9078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broderick N.A., Raffa K.F., Goodman R.M., Handelsman J. Census of the bacterial community of the gypsy moth larval midgut by using culturing and culture-independent methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:293–300. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.293-300.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funk D.J., Bernays E.A. Geographic variation in host specificity reveals host range evolution in Uroleucon ambrosiae Aphids. Ecology. 2001;82:726–739. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[0726:GVIHSR]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douglas A.E. The microbial dimension in insect nutritional ecology. Funct. Ecol. 2009;23:38–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01442.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morales-Jiménez J., Zúñiga G., Ramírez-Saad H.C., Hernández-Rodríguez C. Gut-associated bacteria throughout the life cycle of the bark beetle Dendroctonus rhizophagus Thomas and Bright (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) and their cellulolytic activities. Microb. Ecol. 2012;64:268–278. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9999-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterkova-koci K., Robles-Murguia M., Ramalho-Ortigao M., Zurek L. Significance of bacteria in oviposition and larval development of the sand fly Lutzomyia longipalpis. Parasite Vector. 2012;5:145. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Six D.L. The bark beetle holobiont: Why microbes matter. J. Chem. Ecol. 2013;39:989–1002. doi: 10.1007/s10886-013-0318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geib S.M., Filley T.R., Hatcher P.G., Hoover K., Carlson J.E., Jimenez-Gasco M.D.M., Nakagawa-Izumi A., Sleighter R.L., Ming T. Lignin degradation in wood-feeding insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:129–132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805257105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peay K.G., Kennedy P.G., Talbot J.M. Dimensions of biodiversity in the earth mycobiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;14:434–447. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talbot J.M., Allison S.D., Treseder K.K. Decomposers in disguise: Mycorrhizal fungi as regulators of soil C dynamics in ecosystems under global change. Funct. Ecol. 2008;22:955–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01402.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindahl B.D., Tunlid A. Ectomycorrhizal fungi-potential organic matter decomposers, yet not saprotrophs. New Phytol. 2015;205:1443–1447. doi: 10.1111/nph.13201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Douglas A.E. Multiorganismal insects: Diversity and function of resident microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2015;60:17–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suh S.O., Marshall C.J., Mchugh J.V., Blackwell M. Wood ingestion by Passalid beetles in the presence of xylose-fermenting gut yeasts. Mol. Ecol. 2010;12:3137–3145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Florn R., Evelyn G., Zulema G., Nydia L., César H., Amy B., Gerardo Z. Gut-associated yeast in bark beetles of the genus Dendroctonus erichson (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2010;98:325–342. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu X., Li M., Chen H. Community structure of gut fungi during different developmental stages of the Chinese white pine beetle (Dendroctonus armandi) Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8411–8418. doi: 10.1038/srep08411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott J.J., Oh D.C., Yuceer M.C., Klepzig K.D., Clardy J., Currie C.R. Bacterial protection of beetle-fungus mutualism. Science. 2008;322:63. doi: 10.1126/science.1160423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masuya H., Yamaoka Y. The relationships between fungi and Scolytid and Platypodid beetles. Jpn. For. Soc. 2009;91:433–445. doi: 10.4005/jjfs.91.433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziganshina E.E., Mohammed W.S., Shagimardanova E.I., Vankov P.Y., Gogoleva N.E., Ziganshin A.M. Fungal, bacterial, and archaeal diversity in the digestive tract of several beetle larvae (Coleoptera) BioMed Res. Int. 2018;5:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2018/6765438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furniss M.M. Biology of trypophloeus striatulus (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) in feltleaf willow in interior alaska|environmental entomology|oxford academic. Environ. Entomol. 2004;33:21–27. doi: 10.1603/0046-225X-33.1.21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Summerell B.A., Laurence M.H., Liew E.C.Y., Leslie J.F. Biogeography and phylogeography of Fusarium: A review. Fungal Divers. 2010;44:3–13. doi: 10.1007/s13225-010-0060-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo Z., Döll K., Dastjerdi R., Karlovsky P., Dehne H.W., Altincicek B. Effect of fungal colonization of wheat grains with Fusarium spp. on food choice, weight gain and mortality of meal beetle larvae (Tenebrio molitor) PLoS ONE. 2014;9:100–112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dowd P.F., Bhatnagar D., Lillehoj E.B., Arora D.K. Insect interactions with mycotoxin-producing fungi and their hosts. Mycotoxins Ecol. Syst. 1992;5:137–155. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dowd P.F. Insect management to facilitate preharvest mycotoxin management. Toxin Rev. 2003;22:327–350. doi: 10.1081/TXR-120024097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulthess F., Cardwell K.F., Gounou S. The effect of endophytic Fusarium verticillioides on infestation of two maize varieties by Lepidopterous stemborers and Coleopteran grain feeders. Phytopathology. 2002;92:120–128. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2002.92.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurtzman C.P. Chapter 51—Nakazawaea Y. Yamada, Maeda & Mikata (1994) Yeasts. 2011;2:637–639. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis T.S. The ecology of yests in the bark beetle holobiont: A century of research revisited. Microb. Ecol. 2014;69:723–732. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hofstetter R.W., Dinkins-Bookwalter J., Davis T.S., Klepzig K.D. Symbiotic Associations of Bark Beetles. Bark Beetles. 2015;6:209–245. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polburee P., Lertwattanasakul N., Limtong P., Groenewald M., Limtong S. Nakazawaea todaengensis f.a., sp. nov., a yeast isolated from a peat swamp forest in Thailand. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017;67:23–77. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lou Q.Z., Min L., Sun J.H. Yeast diversity associated with invasive Dendroctonus valens, killing pinus tabuliformis, in china using culturing and molecular methods. Microb. Ecol. 2014;68:397–415. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Durand A.A., Buffet J.P., Constant P., Deziel E., Guertin C. Fungal communities associated with the easten larch beetle: Diversity and variation within developmental stages. Biorxiv. 2017;16:40–42. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaewwichian R., Limtong S. Nakazawaea siamensis f.a., sp. nov., a yeast species isolated from phylloplane. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014;64:266–270. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.057521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kurtzman C.P. Three new ascomycetous yeasts from insect-associated arboreal habitats. Can. J. Microbiol. 2000;46:50–58. doi: 10.1139/cjm-46-1-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee S., Kim J.J., Breuil C., And J.J. Diversity of fungi associated with mountain pine beetle, Dendroctonus ponderosae, and infested lodgepole pines in British Columbia. Candian For. Serv. 2006;91:433–455. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharma A., Gautam S., Mishra B.B. Trichothecium . Encycl. Food Microbiol. 2014;41:647–652. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fang W.U., Yuan Y., Liu H.G., Dai Y.C., University B.F. Auricularia (Auriculariales, Basidiomycota): A review of recent research progress. Mycosystema. 2014;33:198–207. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoebeke E.R., Wheeler Q.D., Gilbertson R.L. Second Eucinetidae-Coniophoraceae association (Coleoptera; Basidiomycetes), with notes on the biology of Eucinetus oviformis Leconte (Eucinetidae) and on two species of Endomychidae. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 1987;89:215–218. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lawrence J.F. Host preference in ciid beetles (Coleoptera: Ciidae) inhabiting the fruiting bodies of Basidiomycetes in North America. Bull. Museum Comp. Zool. 1973;145:163–212. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lilburn T.G., Kim K.S., Ostrom N.E., Byzek K.R., Leadbetter J.R., Breznak J.A. Nitrogen fixation by symbiotic and free-living spirochetes. Science. 2001;292:2495–2498. doi: 10.1126/science.1060281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lenz M. Food resources, colony growth and caste development in wood-feeding Termites. Nourishment Evolut. Insect Soc. 1994;22:114–119. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wingfield M.J., Gibbs J.N. Leptographium and Graphium species associated with pine-infesting bark beetles in England. Mycol. Res. 1991;95:1257–1260. doi: 10.1016/S0953-7562(09)80570-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bleiker K.P., Six D.L. Dietary benefits of fungal associates to an eruptive herbivore: Potential implications of multiple associates on host population dynamics. Environ. Entomol. 2007;36:1384–1396. doi: 10.1093/ee/36.6.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pu X.J., Chen H. Biological characteristics of blue-stain fungus (Leptographium qinlingensis) in Pinus armandi. J. Northwest A F Univ. 2008;36:129–134. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Freeman M., Sharon M., Dori-Bachash M., Maymon M., Belausov E., Maoz Y., Margalit O., Protasov A., Mendel Z. Symbiotic association of three fungal species throughout the life cycle of the ambrosia beetle Euwallacea nr. Fornicates. Symbiosis. 2016;68:115–128. doi: 10.1007/s13199-015-0356-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang J., Gao G., Zhang R., Dai L., Chen H. Metabolism and cold tolerance of Chinese white pine beetle Dendroctonus armandi (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) during the overwintering period. Agric. For. Entomol. 2017;19:10–22. doi: 10.1111/afe.12176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee R.E., Jr. Insect cold-hardiness: To freeze or not to freeze: How insects survive low temperatures. Bioscience. 1989;39:308–313. doi: 10.2307/1311113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khani A., Moharramipour S., Barzegar M. Cold tolerance and trehalose accumulation in overwintering larvae of the codling moth, Cydia pomonella (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Eur. J. Entomol. 2007;104:385–392. doi: 10.14411/eje.2007.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Körner C. The use of ‘altitude’ in ecological research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007;22:569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rowe R.J., Lidgard S. Elevational gradients and species richness: Do methods change pattern perception? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2009;18:163–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2008.00438.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Delalibera I., Handelsman J., Raffa K.F. Contrasts in cellulolytic activities of gut microorganisms between the wood borer, Saperda vestita (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), and the bark beetles, Ips pini and Dendroctonus frontalis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) Environ. Entomol. 2005;34:541–547. doi: 10.1603/0046-225X-34.3.541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Caporaso J.G., Kuczynski J., Stombaugh J., Bittinger K., Bushman F.D., Costello E.K., Fierer N., Pena A.G., Goodrich J.K., Gordon J.I. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kõljalg U., Nilsson R.H., Abarenkov K., Tedersoo L., Taylor A.F., Bahram M., Bahram M., Bates S.T., Bruns T.D., Bengtssonpalme J., et al. Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Mol. Ecol. 2013;22:5271–5277. doi: 10.1111/mec.12481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]