Abstract

Urophysa is a Chinese endemic genus comprising two species, Urophysa rockii and Urophysa henryi. In this study, we sequenced the complete chloroplast (cp) genomes of these two species and of their relative Semiquilegia adoxoides. Illumina sequencing technology was used to compare sequences, elucidate the intra- and interspecies variations, and infer the phylogeny relationship with other Ranunculaceae family species. A typical quadripartite structure was detected, with a genome size from 158,473 to 158,512 bp, consisting of a pair of inverted repeats separated by a small single-copy region and a large single-copy region. We analyzed the nucleotide diversity and repeated sequences components and conducted a positive selection analysis by the codon-based substitution on single-copy coding sequence (CDS). Seven regions were found to possess relatively high nucleotide diversity, and numerous variable repeats and simple sequence repeats (SSR) markers were detected. Six single-copy genes (atpA, rpl20, psaA, atpB, ndhI, and rbcL) resulted to have high posterior probabilities of codon sites in the positive selection analysis, which means that the six genes may be under a great selection pressure. The visualization results of the six genes showed that the amino acid properties across each column of all species are variable in different genera. All these regions with high nucleotide diversity, abundant repeats, and under positive selection will provide potential plastid markers for further taxonomic, phylogenetic, and population genetics studies in Urophysa and its relatives. Phylogenetic analyses based on the 79 single-copy genes, the whole complete genome sequences, and all CDS sequences showed same topologies with high support, and U. rockii was closely clustered with U. henryi within the Urophysa genus, with S. adoxoides as their closest relative. Therefore, the complete cp genomes in Urophysa species provide interesting insights and valuable information that can be used to identify related species and reconstruct their phylogeny.

Keywords: Urophysa, Semiaquilegia adoxoides, cp genome, repeat analysis, SSRs, positive selection analysis, phylogeny

1. Introduction

The genus Urophysa (Ranunculaceae) is a Chinese endemic genus with only two species, Urophysa rockii Ulbr. and Urophysa henryi (Oliv.) Ulbr. U. rockii is an extremely rare species with fewer than 2000 individuals living in Jiangyou, a Sichuan province of China, and U. henryi is distributed in Guizhou, south Chongqing, north Hunan, and west Hubei [1]. The two species’ natural populations are restricted to small and isolated areas separated by high mountains and deep valleys and grow in steep and karstic cliffs with dramatically shrinking and fragmenting natural distributions [2]. In addition, the plants are collected for Chinese traditional medicine for the treatment of contusions and bruises, which contributed to the decline of their populations [3]. Previous studies on the genus Urophysa are scarce and mainly focused on the endangered U. rockii, its growing environment and conservation strategies [4], its biological and ecological characteristics, and its reproductive biology [5,6]. A recent study suggested that the uplift of the Yungui Plateau played an important role in the species divergence of Urophysa [2]. However, the chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) phylogeny showed inconsistency with the nuclear ribosomal DNA (nrDNA). Hence, to gain a better insight into the relationship of these two species and understand their genome structure so as to facilitate their speciation process and the conservation of U. rockii, we assembled and characterized the complete chloroplast genome sequence of U. rockii and U. henryi using the Illumina paired-end sequencing reads.

The angiosperm cp genome is one of the three DNA genomes (the other two are nuclear and mitochondrial genome), is uniparentally inherited, and has a high conserved circular DNA arrangement [7]. It is widely considered an informative and valuable resource for investigating evolutionary biology because of its relatively stable genome structure, gene content, and gene order [8,9,10,11,12,13]. The cp genome of plants always ranges from 115 to 210 kb and has a quadripartite structure that is typically composed of two copies of inverted repeat (IR) regions, which are separated by a large single-copy (LSC) region and a small single-copy (SSC) region [14,15,16]. Because of its compact size, less recombination, and maternal inheritance, the cp genome has been used to generate genetic markers for phylogenetic analysis [17,18], molecular identification [19], and divergence dating [20]. Especially, the low evolutionary rate of the cp genome in taxa that are not very young makes it an ideal system for assessing plant phylogeny [21].

In the present study, we report the complete chloroplast genome sequences of these two Urophysa species and their relative Semiquilegia adoxoides for the first time. Combining previously reported cp genome sequences, we performed phylogenetic analyses according to the whole cp genome and shared single-copy genes. Our findings will contribute to our understanding of the evolutionary history of the genus Urophysa. Additionally, highly variable regions and genes that were detected to be under positive selection could be employed to develop potential markers for phylogenetic analyses or candidates for DNA barcoding in future studies.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Three Species

The complete chloroplast genome of U. rockii, U. henryi, and S. adoxoides showed a single circular molecule with a typical quadripartite structure (Figure 1). The sizes of the U. rockii, U. henry, and S. adoxoides cp genomes were found to be 158,512 bp, 158,303, and 158,340 bp, respectively, which are in the range of most angiosperm plastid genomes [22]. The cp genome consists of a pair of IRs (IRa and IRb, with length 26,473–26,584 bp), separated by a LSC (87,031–87,202 bp) region and one SSC (18,192–18,220 bp) region (Table 1). The GC content of each species was very similar in the whole cp genome and the same region (LSC, SSC, and IR), but in the IR regions it was clearly higher than in the other regions, possibly because of the high GC content of the rRNA (55.8%) that was located in the IR regions (Table 2). These results are similar to a previously reported high GC percentage in IR regions [23,24,25].

Figure 1.

Gene maps of the Urophysa rockii, Urophysa henryi and Semiquilegia adoxoides chloroplast (cp) genomes. Genes shown inside the circle are transcribed clockwise, and those outside are transcribed counterclockwise. Genes belonging to different functional groups are color-coded. The darker gray color in the inner circle corresponds to the GC content, and the lighter gray color corresponds to the AT content. SSU: small subunit; LSU: large subunit; ORF: open reading frame.

Table 1.

Summary of complete chloroplast genomes. LSC, large single-copy; SSC, small single-copy; IR, inverted repeat

| Species | LSC | SSC | IR | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (bp) | GC% | Length (%) | Length (bp) | GC% | Length (%) | Length (bp) | GC% | Length (%) | Length (bp) | GC% | |

| U. rockii | 87,128 | 37.2 | 55.0 | 18,216 | 32.5 | 11.5 | 26,584 | 43.7 | 16.8 | 158,512 | 38.8 |

| U. henryi | 87,031 | 37.2 | 55.0 | 18,260 | 32.6 | 11.5 | 26,506 | 43.6 | 16.7 | 158,303 | 38.8 |

| S. adoxoides | 87,202 | 37.2 | 55.1 | 18,192 | 32.5 | 11.5 | 26,473 | 43.7 | 16.7 | 158,340 | 38.9 |

| Tsuga chinensis | 88,522 | 36.3 | 55.3 | 18,405 | 32.0 | 11.5 | 26,632 | 43.1 | 16.6 | 160,191 | 38.1 |

| Aconitum austrokoreense | 86,362 | 36.2 | 55.4 | 16,948 | 32.7 | 10.9 | 26,291 | 43.0 | 16.9 | 155,892 | 38.1 |

| A. kusnezoffii | 86,335 | 36.2 | 55.4 | 16,945 | 32.7 | 10.9 | 26,291 | 43.0 | 16.9 | 155,862 | 38.1 |

| A. volubile | 86,348 | 36.2 | 55.4 | 16,944 | 32.6 | 10.9 | 26,290 | 43.0 | 16.9 | 155,872 | 38.1 |

| Ranunculus macranthus | 84,637 | 36.0 | 54.6 | 18,909 | 31.0 | 12.2 | 25,791 | 43.5 | 16.6 | 155,129 | 37.9 |

| R. occidentalis | 83,532 | 35.9 | 54.1 | 21,269 | 31.6 | 13.8 | 24,831 | 43.6 | 16.1 | 154,474 | 37.8 |

| R. austro-oreganus | 83,582 | 35.9 | 54.1 | 21,249 | 31.6 | 13.8 | 24,831 | 43.6 | 16.1 | 154,493 | 37.8 |

| Clematis terniflora | 79,328 | 36.3 | 49.7 | 18,110 | 31.4 | 11.4 | 31,045 | 42.0 | 19.5 | 159,528 | 38.0 |

| Coptis chinensis | 84,567 | 36.4 | 54.4 | 17,376 | 32.1 | 11.2 | 26,762 | 43.0 | 17.2 | 155,484 | 38.2 |

Table 2.

Comparison of the sizes of coding and non-coding regions among species.

| Species | Protein-Coding | tRNA | rRNA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (bp) | GC% | Length (%) | Length (bp) | GC% | Length (%) | Length (bp) | GC% | Length (%) | |

| U. rockii | 78,867 | 39.2 | 49.8 | 2687 | 53.2 | 1.7 | 8602 | 55.8 | 5.4 |

| U. henryi | 78,769 | 39.2 | 49.8 | 2695 | 53.3 | 1.7 | 8602 | 55.8 | 5.4 |

| S. adoxoides | 78,498 | 39.3 | 49.6 | 2706 | 53.6 | 1.7 | 8602 | 55.8 | 5.4 |

| T. chinensis | 78,903 | 38.4 | 49.3 | 2716 | 53.1 | 1.7 | 9050 | 55.4 | 5.6 |

| A. austrokoreense | 79,575 | 38.3 | 51.0 | 2810 | 53.0 | 1.8 | 9050 | 55.4 | 5.8 |

| A. kusnezoffii | 78,294 | 38.4 | 50.2 | 2813 | 52.9 | 1.8 | 9046 | 55.3 | 5.8 |

| A. volubile | 79,560 | 38.3 | 51.0 | 2810 | 53.0 | 1.8 | 9050 | 55.5 | 5.8 |

| R. macranthus | 78,615 | 38.2 | 50.7 | 2738 | 53.1 | 1.8 | 7559 | 55.2 | 4.9 |

| R. occidentalis | 69,294 | 38.6 | 44.9 | 2717 | 53.1 | 1.8 | 9050 | 55.4 | 5.9 |

| R. austro-oreganus | 74,355 | 38.1 | 48.1 | 2796 | 52.9 | 1.8 | 9050 | 55.4 | 5.9 |

| C. terniflora | 81,819 | 38.3 | 51.3 | 2718 | 53.4 | 1.7 | 9050 | 55.4 | 5.7 |

| C. chinensis | 71,637 | 39.0 | 46.1 | 2716 | 53.2 | 1.7 | 9050 | 55.5 | 5.8 |

The genomes contain 87 coding genes, 36 transfer RNA genes (tRNA), and 8 ribosomal RNA genes (rRNA) (Table 3). Most of the genes occur as a single copy in LSC or SSC regions, while 18 genes are duplicated in the IR regions, including seven protein-coding genes (ndhB, rpl2, rpl23, rps7, rps12, rps19, ycf2), seven tRNA species (trnA-UGC, trnI-CAU, trnI-GAU, trnL-CAA, trnN-GUU, trnR-ACG, and trnV-GAC) and four rRNA species (rrn4.5, rrn5, rrn16, and rrn23). The gene ycf1 straddles the SSC and IRs, while rps12 locates its first exon in the LSC region and two other exons in the IRs. The LSC region comprises 63 protein-coding genes and 21 tRNA genes, whereas the SSC and IR regions include 12 and 7 protein-coding genes, with one and seven tRNA, respectively. The protein-coding genes present in the U. rockii cp genome include 9 genes encoding large ribosomal proteins (rpl2, rpl14, rpl16, rpl20, rpl22, rpl23, rpl32, rpl33, rpl36) and 12 genes encoding small ribosomal proteins (rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7, rps8, rps11, rps12, rps14, rps15, rps16, rps18, rps19). There are 5 genes encoding phytosystem I subunits (psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ), along with 15 genes related to photosystem II subunits (psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, psbZ) (Table 3). Six genes (atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF, atpH, atpI) encode ATP synthase and electron transport chain components (Table 3). A similar pattern of protein-coding genes is also present in U. henryi and S. adoxoides. There are eight intron-containing genes, six of which contain one intron; only the genes clpP and ycf3 have two introns (Table S1). All these eight genes possess at least two exons, and ycf3 has three exons. The rps16 gene has the longest intron (866 bp), and rpoC1 has the longest exon (1613 bp).

Table 3.

List of genes encoded in two Urophysa species and S. adoxoides.

| Category for Genes | Group of Genes | Name of Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Self-replication | transfer RNAs | trnA-UGC *, trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnE-UUC, trnF-GAA, trnfM-CAU, trnG-GCC, trnG-UCC, trnI-CAU *, trnI-GAU *, trnK-UUU, trnL-CAA *, trnL-UAA, trnL-UAG, trnM-CAU, trnN-GUU *, trnP-UGG, trnQ-UUG, trnR-ACG *, trnR-UCU, trnS-GCU, trnS-GGA, trnS-UGA, trnT-GGU, trnT-UGU, trnV-GAC *, trnV-UAC, trnW-CCA, trnY-GUA |

| ribosomal RNAs | rrn4.5 *, rrna5 *, rrn16 *, rrn23 * | |

| RNA polymerase | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1, rpoC2 | |

| Small subunit of ribosomal proteins (SSU) | rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7 *, rps8, rps11, rps12 *, rps14, rps15, rps16, rps18, rps19 * | |

| Large subunit of ribosomal proteins (LSU) | rpl2 *, rpl14, rpl16, rpl20, rpl22, rpl23 *, rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 | |

| Genes for photosynthesis | Subunits of NADH-dehydrogenase | ndhA, ndhB *, ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK |

| Subunits of photosystem I | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ | |

| Subunits of photosystem II | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, psbZ | |

| Subunits of cytochrome b/f complex | petA, petB, petD, petG, petL, petN | |

| Subunits of ATP synthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF, atpH, atpI | |

| Large subunit of rubisco | rbcL | |

| Other genes | Tanslational initiation factor | infA |

| Protease | clpP | |

| Maturase | matK | |

| Subunit of Acetyl-CoA-carboxylase | accD | |

| Envelope membrane protein | cemA | |

| C-type cytochrome synthesis gene | ccsA | |

| Genes of unknown function | hypothetical chloroplast reading frames (ycf) | ycf1 *, ycf2 *, ycf3, ycf4 |

* Gene with two copies.

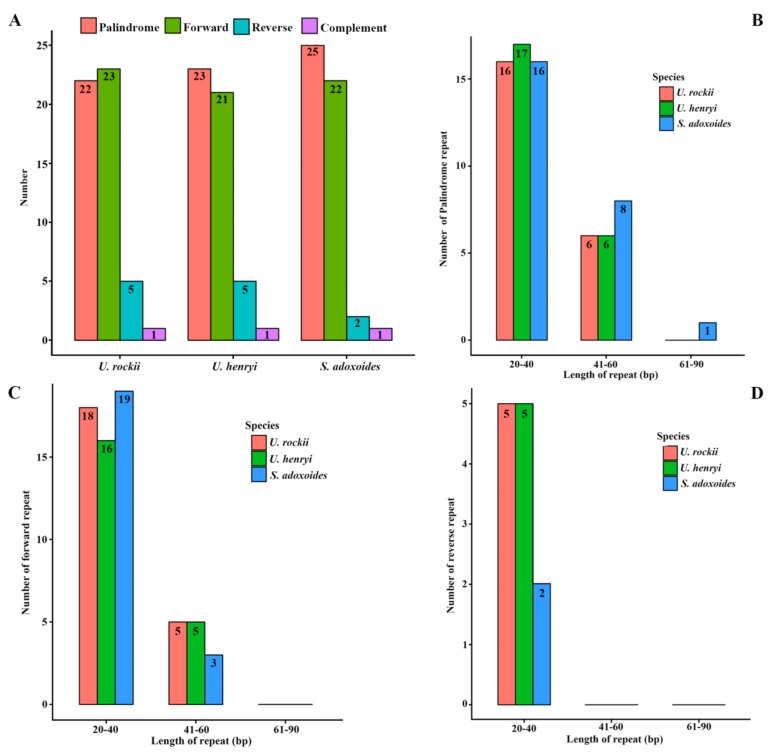

2.2. Repeat Analysis

Chloroplast repeats are potentially useful genetic resources to investigate population genetics and biogeography of allied taxa [26]. Analyses of various cp genomes revealed that repeat sequences are essential to induce indels and substitutions [27]. Repeat analysis of the U. rockii cp genome revealed 22 palindromic repeats, 23 forward repeats, 5 reverse, and 1 complement repeats. Among them, 16 palindromic, 18 forward, and 5 reverse repeats are 20–40 bp in length. Six palindromic and five forward repeats are 41–60 in length (Figure 2). Similarly, 23 and 25 palindromic repeats, 21 and 22 forward repeats, 5 and 2 reverse repeats, and 1 complement repeats were detected, and the detailed repeats length distributions are shown in Figure 2. The number and length of the repeats indicate that U. rockii is more similar to U. henryi than to S. aquilegia. Previous studies suggested that the slipped-strand mispairing and improper recombination of repeat sequences can result in sequence variation and genome rearrangement [28,29,30]. These repeats are informative sources for developing genetic markers for phylogenetic and population studies [31].

Figure 2.

Analysis of repeated sequences in U. rockii, U. henryi, and S. adoxoides chloroplast genomes. (A) Total of four repeat types; (B) Frequency of the palindromic repeat by length; (C) Frequency of the forward repeat by length; (D) Frequency of the reverse repeat by length.

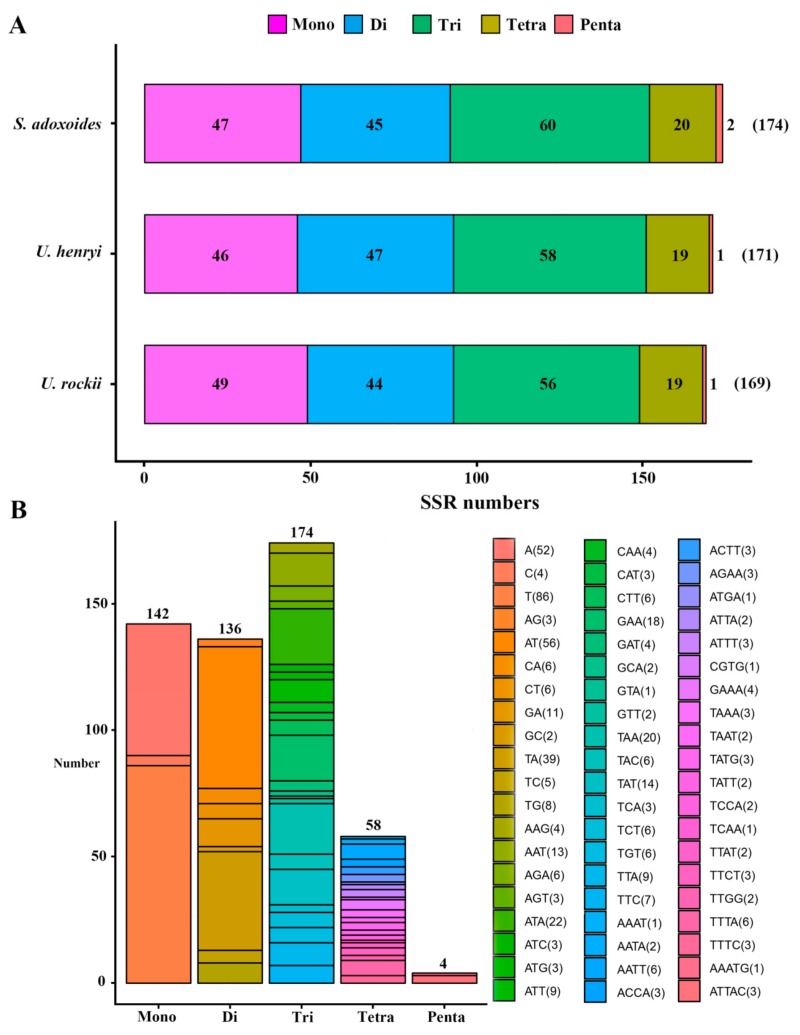

Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in the cp genome can be highly variable at the intra-specific level and are therefore often used as genetic markers in population genetic and evolutionary studies [12,32,33,34]. Because of a high polymorphism rate at the species level, SSRs have been recognized as one of the main sources of molecular markers and have been extensively researched in phylogenetic and biogeographic studies of populations [35,36,37]. In this study, we analyzed the SSRs in the cp genomes. Five categories of perfect SSRs (mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, and penta-nucleotide repeats) were detected in the cp genome of these three species, with an overall length ranging from 10 to 26 bp (Figure 3, Table S2). Certain parameters were set, because SSRs of 10 bp or longer are prone to slipped-strand mispairing, which is believed to be the main mutational mechanism for polymorphism [38,39,40].

Figure 3.

Analysis of simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in chloroplast genomes of the three species. (A) Number of different SSR types detected in each species; (B) type and frequency of each identified SSR.

A total of 169 microsatellites were detected in the U. rockii cp genome on the basis of the SSR analysis. Similarly, 171 and 174 SSRs were detected in U. henryi and S. adoxoides, respectively (Figure 3A). The most abundant were tri-nucleotide repeats, which accounted for about 33.85% of the total SSRs, and whose number varies from 56 in U. rockii to 60 in S. adoxoides, followed by mono-nucleotide repeats (27.63%), di-nucleotide repeats (26.46%), and tetra-nucleotides repeats (11.28%). Penta-nucleotide repeats were the least abundant (0.78%; Figure 3, Table S2). Most previous studies revealed that the richness of SSR types varies between species. In Quercus species, mono-nucleotide repeats are the most abundant, accounting for about 80% of the total SSRs [34]. In the cp genome of Forthysia, the number of di-nucleotide repeat is the highest [41]. Tri-nucleotide SSRs are most abundant in Nicotiana species, accounting for approximately 43.03% [42]. These results suggest that different repeats may contribute to the genetic variations differently among species. Thus, the SSR information will be important for understanding the genetic diversity status of Urophysa and its relatives.

In U. rockii, more than 96.2% mono-nucleotides are composed of A/T, and a majority of di-nucleotides (84.9%) is composed of A/T (Figure 3B, Table S2), which is consistent with U. henryi (97.8% mono-nucleotides and 83.0% di-nucleotides) and S. aquilegia (97.9% mono-nucleotides and 85.6% di-nucleotides). Our findings are comparable to previously reported observations that SSRs found in the chloroplast genome are generally composed of poly-thymine (polyT) or poly-adenine (polyA) repeats and infrequently contain tandem cytosine (C) and guanine (G) repeats [43]. Therefore, these SSRs contribute to the AT richness of the three species cp genome, as previously reported for different species [43,44]. SSRs were also detected in CDS regions of the U. rockii cp genome. The CDS regions account for approximately 49% of the total length. About 68.6% of SSRs (68.4% for U. henryi and 67.2% for S. adoxoides) were detected in non-coding regions, whereas only 28.9%of SSRs (29.2% for U. henryi and 30.5% for S. adoxoides) are present in the protein-coding region of U. rockii. Furthermore, about 62.1% of SSRs are present in the LSC region of U. rockii (66.1% for U. henryi and 68.9% for S. adoxoides), and a minority of SSRs exist in IR regions (17.8% in IRa and IRb in total). It was observed that 49 SSRs (28.9%) were located in 19 genes (CDS) regions (atpF, rpoC1, rpoC2, rps14, rps15, rps19, psaB, psaA, rbcL, rpl33, rpl22, ndhB, ndhD, ndhF, ndhH, ccsA, ycf1, ycf2, ycf3) in U. rockii. The detailed SSR location information is listed in Table S2. These results suggest an uneven distribution of SSRs in the U. rockii, U. henryi, and S. adoxoides cp genomes, as was also reported in different angiosperm cp genomes [44]. Moreover, the cp SSRs of the three species presented abundant variation and are useful for detecting genetic polymorphisms at population, intraspecific, and cultivar levels, as well as for comparing more distant phylogenetic relationships among species.

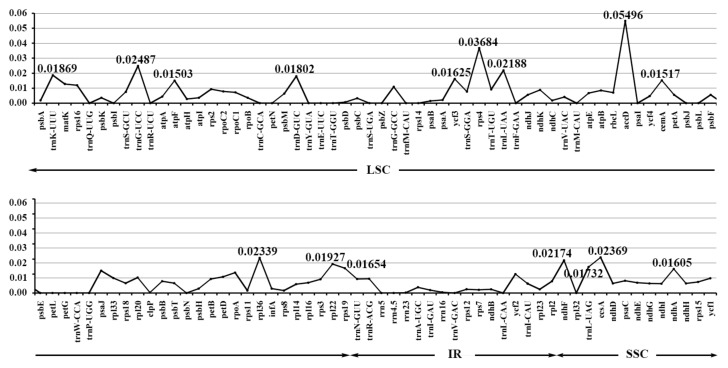

2.3. Genomes Sequence Divergence among the Three Species

In order to calculate the sequence divergence level, the nucleotide diversity values in the LSC, SSC, and IR regions of the chloroplast genomes were calculated (Figure 4, Table S3). In the LSC regions, these values varied from 0 to 0.05496, with a mean of 0.00705, in the IR regions they varied from 0 to 0.01265, with a mean of 0.00363, and only the SSC region had >0.010 average sequence nucleotide diversity, and its values varied from 0 to 0.02369, with a mean of 0.01048. All these results indicated that the differences among these genome regions were small. However, some highly variable loci, including trnK-UUU, trnG-UCC, trnD-GUC, atpF, rps4, trnL-UAA, accD, cemA, rpl36, rpl22, rps19, ndhF, trnL-UAG, ccsA, ndhA, and ycf3 were more precisely located (Figure 4, Table S3). All these regions displayed higher nucleotide diversity values than other regions (value > 0.015). Twelve of these loci were found to be located in the LSC region, and four in the SSC region, but the nucleotide diversity in the IR regions appeared small, less than 0.015. Among these loci, atpF, accD, ndhF, rpl22, ccsA, and ycf3 have been detected as highly variable regions in different plants [19,23,45,46]. On the basis of these results, we believe that accD, rps4, ccsA, rpl36, and ndhF, which have comparatively high sequence deviation, are good sources for interspecies phylogenetic analysis, as shown in previous studies [42,44].

Figure 4.

The nucleotide diversity of the whole chloroplast genomes of the three species. LSC: large single-copy region; IRs: inverted repeats region; SSC: small single-copy region.

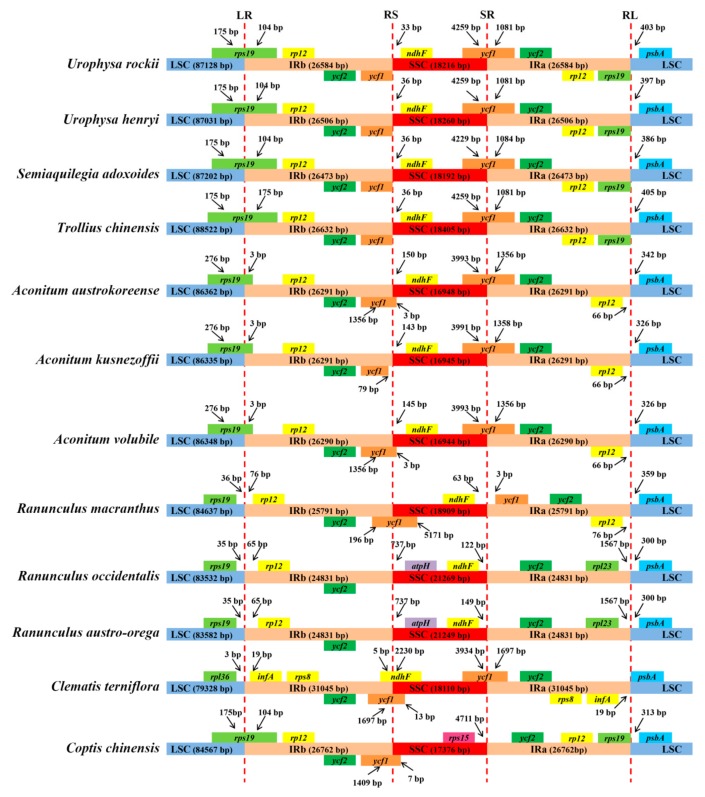

Expansion and contraction at the borders of IR regions is the main reason for size variations in the cp genome and plays a vital role in its evolution [39,47,48]. The IR/LSC and IR/SSC junction regions were compared to identify IR expansion or contraction. The rps19, ndhF, ycf1, and psbA genes were located in the junctions of the LSC/IRa, IRa/SSC, SSC/IRb, and IRb/LSC regions, respectively (Figure 5). Despite the similar length of these three species IR regions, from 26,473 to 26,584 bp, some IR expansion and contraction were observed. The rps19 gene traverses the LSC and IRb regions (LR line), with 104 bp located in the IR region. The RS line (the junction line between IRb and SSC) is located between ycf1 and ndhF, and the variation in distances between the RS line and ndhF ranges from 33 to 36 bp across the three species. The SR line (the junction line between SSC and IRa) intersects the ycf1 gene, the SSC and IRa regions are the same in U. rockii and U. henryi (4259 bp in SSC and 1081 bp in IRb), while different in S. adoxoides (4229 bp in SSC and 1084 bp in IRb) (Figure 5). The distance between the psbA and RL line varies from 386 to 403 bp. Compared to species of other genera, the IRb/SSC and SSC/IRa regions of Urophysa showed an expansion in ycf1, but a contraction in rps19 (Figure 5). The expansion and contraction detected in the IR regions may act as a primary mechanism in creating the length variation of the cp genomes in U. rockii, U. henryi, and S. adoxoides, as previous studies suggested [32,34,42,49].

Figure 5.

Comparison of the borders of the LSC, SSC, and IR regions of the chloroplast genomes of the three species. LR: junction line between LSC and IRb; RS: junction line between IRb and SSC; SR: junction line between SSC and IRa; RL: junction line between IRa and LSC.

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

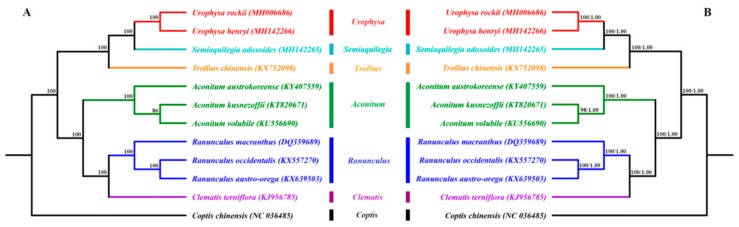

To study the phylogenetic position of U. rockii and U. henryi within the Ranunculaceae family, we used 79 single-copy genes shared by the cp genomes of 12 Ranunculaceae members, representing seven genera (Figure 6). For Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum parsimony (MP), the posterior probabilities and bootstrap values were very high for each lineage, with all values ≥98%. Both the maximum likelihood (ML), BI, and MP phylogenetic results strongly supported that U. rockii is closely clustered with U. henryi within the genus Urophysa, with S. adoxoides as their closest relative with 100% bootstrap value (Figure 6), which is consistent with the results of previous molecular studies [50,51,52]. Furthermore, the species in each genus formed a single clade. The first clade is formed by species of the genera Urophysa, Semiaquilegia, and Trollius, the second clade was divided into two clades: one clade includes the Ranunculus and Clematis species, and the other clade consists of just the Aconitum species. Additionally, the topological structures from the whole complete chloroplast genome sequences and the CDS sequences are similar to that from single-copy genes (Figure S1), and all lineages possess high bootstrap values. These results suggest that there is no conflict among the entire genome data set, CDS sequences, and 79 shared single-copy genes of these cp genomes. Furthermore, these results are in accord with previous phylogeny research [53]. All these phylogenetic analyses are substantially increasing our understanding of the evolutionary relationship among species in Ranunculaceae.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic relationship of Urophysa with related species based on 79 single-copy genes shared by all cp genomes. Tree constructed by (A) maximum likelihood (ML) with the bootstrap values of ML above the branches; (B) maximum parsimony (MP) and Bayesian inference (BI) with bootstrap values of MP and posterior probabilities of BI above the branches, respectively.

2.5. Positive Selected Analysis

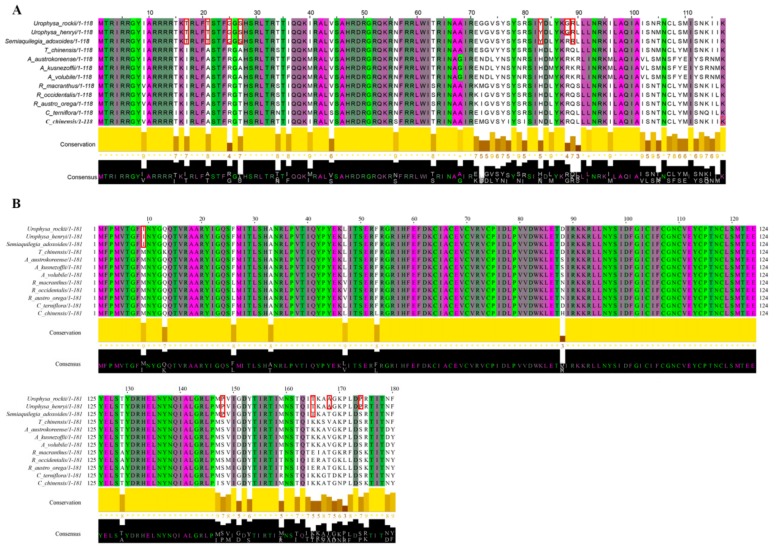

Of 57 single-copy CDS genes initially considered for the positive selection analysis (Table S4), 47 were eventually selected (Table 4). No significant positive selection was detected for all genes (p-value > 0.05), but six genes that possess high posterior probabilities for codon sites were found in the Bayesian Empirical Bayes (BEB) test (atpA, rpl20, psaA, atpB, ndhI, and rbcL) (Figure 7, Figure S2 and Table 4). Previous studies suggested that codon sites with a high posterior probability should be regarded as positively selected sites [54], which means that these six genes may be under positive selection pressure [55]. After Jalview visualization, the results of the amino acid properties across each column of all species revealed that many amino acids vary between different genera, such as the 88th amino acid (G in U. rockii and U. henryi, R in other species) of the rpl20 gene (Figure 7A) and other amino acids (marked with red blocks in Figure 7A). In the ndhI gene, two amino acids (the A in 168th and the P in 174th) were specific for U. rockii and U. henryi, and three amino acids (the 9th, 148th, and 165th, marked with red blocks in Figure 7B) were only possessed by U. rockii, U. henryi, and S. adoxoides. The amino acid properties of the other four genes (atpA, atpB, rbcL, and psaA) are shown in Figure S2. As we know, most amino acids may be under strong structural and functional constraints and not free to change [55]. We detected six genes with high posterior probability in codon site and many different amino acids among species, which may play an important role in Urophysa species evolution and environment adaptation. Populations of U. rockii and U. henryi are distributed only in karst regions of southern China, and the karst environments are characterized by low soil water content, insufficient light, and poor nutrient availability, which might have exerted strong selective forces on plant evolution [56].

Table 4.

The potential positive selection test based on the branch-site model.

| Gene Name | Null Hypothesis | Alternative Hypothesis | Significance Test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnL | df | Omega (ω = 1) | lnL | df | Omega (ω > 1) | BEB | NEB | p-Value | |

| psbI | −188.6475 | 26 | 1 | −188.6475 | 27 | 3.40383 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psbL | −164.11693 | 26 | 1 | −164.1169 | 27 | 3.40719 | NA | NA | 1 |

| rps14 | −621.64162 | 26 | 1 | −621.6416 | 27 | 3.40833 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psaI | −214.67663 | 26 | 1 | −214.6766 | 27 | 3.38764 | NA | NA | 1 |

| atpH | −434.45059 | 26 | 1 | −434.4506 | 27 | 3.35869 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psaJ | −318.52192 | 26 | 1 | −318.5219 | 27 | 3.4089 | NA | NA | 1 |

| atpE | −868.20243 | 26 | 1 | −868.2024 | 27 | 3.40891 | NA | NA | 1 |

| atpA | −3297.629 | 26 | 1 | −3297.41 | 27 | 69.43581 | 220, E, 0.794 | NA | 5.04 × 10-1 |

| petN | −126.25816 | 26 | 1 | −126.2582 | 27 | 3.40693 | NA | NA | 1 |

| rps11 | −920.92455 | 26 | 1 | −920.9246 | 27 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psbT | −216.52331 | 26 | 1 | −216.5233 | 27 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 |

| ndhG | −1238.1161 | 26 | 1 | −1238.116 | 27 | 3.33667 | NA | NA | 9.99 × 10-1 |

| ycf4 | −1275.4093 | 26 | 1 | −1275.409 | 27 | 3.40886 | NA | NA | 1 |

| rps18 | −567.98294 | 26 | 1 | −567.9829 | 27 | 3.39414 | NA | NA | 1 |

| petB | −1274.0507 | 26 | 1 | −1274.051 | 27 | 3.403 | NA | NA | 1 |

| rpl20 | −1000.285 | 26 | 1 | −999.941 | 27 | 112.30316 | 88, R, 0.683 | NA | 4.07 × 10-1 |

| psbN | −223.7602 | 26 | 1 | −223.7602 | 27 | 3.40292 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psbF | −198.46733 | 26 | 1 | −198.4673 | 27 | 3.38407 | NA | NA | 1 |

| petG | −206.74878 | 26 | 1 | −206.7488 | 27 | 3.42095 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psbK | −375.13705 | 26 | 1 | −375.1371 | 27 | 3.4063 | NA | NA | 1 |

| rpl36 | −267.8099 | 26 | 1 | −267.8099 | 27 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 |

| rps2 | −1620.734 | 26 | 1 | −1620.734 | 27 | 3.40891 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psbM | −179.71897 | 26 | 1 | −179.719 | 27 | 3.4064 | NA | NA | 1 |

| rpoB | −6830.0894 | 26 | 1 | −6830.089 | 27 | 3.40847 | NA | NA | 9.99 × 10-1 |

| psaA | −4245.754 | 26 | 1 | −4245.49 | 27 | 63.47379 | 28, R, 0.778 | NA | 4.66 × 10-1 |

| psbH | −540.92362 | 26 | 1 | −540.9236 | 27 | 3.40123 | NA | NA | 1 |

| ndhE | −616.75534 | 26 | 1 | −616.7553 | 27 | 3.40218 | NA | NA | 1 |

| atpB | −3133.747 | 26 | 1 | −3133.75 | 27 | 1 | 115, N, 0.828 | NA | 1 |

| ndhI | −1307.986 | 26 | 1 | −1307.68 | 27 | 575.22179 | 174, S, 0.696 | NA | 4.35 × 10-1 |

| cemA | −1787.561 | 26 | 1 | −1787.561 | 27 | 3.40891 | NA | NA | 1 |

| ndhJ | −1001.4075 | 26 | 1 | −1001.407 | 27 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psbJ | −209.10513 | 26 | 1 | −209.1051 | 27 | 3.38566 | NA | NA | 1 |

| petA | −1331.3789 | 26 | 1 | −1331.379 | 27 | 3.4089 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psbC | −2760.6743 | 26 | 1 | −2760.674 | 27 | 1 | NA | NA | 1 |

| ndhH | −2643.2896 | 26 | 1 | −2643.29 | 27 | 1 | NA | NA | 9.98 × 10-1 |

| rbcL | −2937.477 | 26 | 1 | −2937.41 | 27 | 5.22178 | 440, E, 0.736 | NA | 7.20 × 10-1 |

| clpP | −1301.1173 | 26 | 1 | −1301.117 | 27 | 3.40876 | NA | NA | 1 |

| ndhC | −731.03212 | 26 | 1 | −731.0321 | 27 | 3.33544 | NA | NA | 1 |

| ycf3 | −935.76375 | 26 | 1 | −935.7638 | 27 | 3.40891 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psbD | −1922.7755 | 26 | 1 | −1922.775 | 27 | 3.38592 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psbA | −1960.3785 | 26 | 1 | −1960.379 | 27 | 3.39639 | NA | NA | 1 |

| petL | −172.24809 | 26 | 1 | −172.2481 | 27 | 3.40087 | NA | NA | 1 |

| rpl33 | −413.59385 | 26 | 1 | −413.5939 | 27 | 3.4089 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psbE | −435.90511 | 26 | 1 | −435.9051 | 27 | 3.40785 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psaC | −498.98549 | 26 | 1 | −498.9855 | 27 | 3.408 | NA | NA | 1 |

| atpI | −1445.5558 | 26 | 1 | −1445.556 | 27 | 3.39588 | NA | NA | 1 |

| psaB | −4069.2947 | 26 | 1 | −4069.295 | 27 | 3.41513 | NA | NA | 1 |

Bold types are positively selected sites. BEB: Bayesian Empirical Bayes; NEB: Naïve Empirical Bayes; Amino acid: (E: Glu; R: Arg; N: Asn; S: Ser).

Figure 7.

Two of the amino acids sequences that showed positive selection in the branch-site model test. (A) Amino acids sequences of the rpl20 gene; (B) amino acids sequences of the ndhI gene. The red blocks represent the different amino acids.

However, five of the abovementioned six genes are involved in photosynthesis (atpA, psaA, atpB, ndhI, and rbcL) (Table 3). The gene rpl20 is involved in translation, which is an important part of protein synthesis [57]. The genes atpA and atpB participate in ATP synthesis, which is the main source of energy for the functioning of living cells and all multicellular organisms [58]. Additionally, rbcL is the gene for the Rubisco large subunit protein, which is an important component of photosynthetic electron transport [59,60]. Most previous research has revealed that positive selection of the rbcL gene in land plants may be a common phenomenon [61]. All these genes might play important roles when founder effects occur in populations; both changes in selection pressures and genetic drift result in the rapid shift of these genes to a new, coadapted combination. Therefore, all these genes under positive selection give an indication of why U. rockii and U. henryi could adapt to the harsh environment of karst (characterized by low soil water content, periodic water deficiency, and poor nutrient availability). Moreover, the results of the gene effectiveness test (rbcL and rpl20) (Figure S3) suggested that these genes can distinguish the species of Urophysa and its relatives and can be used for future phylogenetic analyses. The six genes will not only provide insights into chloroplast genome evolution of species of Urophysa, but also offer valuable genetic markers for population phylogenomic studies of Urophysa and its close lineages.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Materials and DNA Extraction

Fresh leaves of U. rockii, U. henryi, and S. aquilegia were collected from Jiangyou (Sichuan, China; coordinates: 31°59′ N, 104°51′ E), Yichang (Hubei, China; coordinates: 30°42′ N, 111°17′ E), and Nanchuan (Chongqing, China; coordinates: 30°04′ N, 90°33′ E), respectively. The fresh leaves from each site were immediately dried with silica gel for further DNA extraction. The total genomic DNA was extracted from leaf tissues with a modified Cetyl Trimethyl Ammonium (CTAB) method [62].

3.2. Chloroplast Genome Sequencing and Assembling

All cp genomes were sequenced using an Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform by Biomarker Technologies, Inc. (Beijing, China) In order to eliminate the interference from mitochondrial or nuclear DNAs, all the cp genome reads were extracted by mapping all raw reads to the reference cp genome of Trollius chinensis (KX752098) with Burrows Wheeler Alignment (BWA) [63]. High-quality reads were obtained using the CLC Genomics Workbench v7.5 (CLC Bio, Aarhus, Denmark) with the default parameters set. A few gaps in the assembled cp genomes were corrected by Sanger sequencing. The primers were designed using Lasergene 7.1 (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA). Primer synthesis and the sequencing of the polymerase chain reaction products were conducted by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). The primers and amplifications are shown in Supplementary Table S5.

3.3. Genome Annotation and Analysis

The complete cp genomes were annotated using the online program DOGMA [64]. The annotation results were checked manually, and the codon positions were adjusted by comparing to a previously homologous gene from various chloroplast genomes present in the database using Geneious R11 (Biomatters, Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand). Furthermore, the OGDRAW1 program [65] was used to draw the circular plastid genome maps. GC content and codon usage were analyzed by the MEGA 6 software [66]. The complete cp genomes of U. rockii, U. henryi, and S. adoxoides are deposited in the GenBank under the accession numbers MH006686, MH142266, and MH142265, respectively.

3.4. Repeat Sequence Characterization and SSRs

Perl script MISA [67] was used to search for microsatellites (mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexa-nucleotides) loci in the cp genomes. The minimum numbers (thresholds) of the SSRs were 10, 5, 4, 3, 3, and 3 for mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexa-nucleotides, respectively. All the repeats were manually verified, and redundant results were removed. REPuter was employed to identify repeat sequences, including palindromic, forward, reverse, and complement, within the cp genome [68]. The following conditions for repeat identification were used: (1) Hamming distance of 3; (2) 90% or greater sequence identity; (3) a minimum repeat size of 30 bp.

3.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the single-copy genes of the three taxa, together with nine species downloaded from the NCBI GenBank (Tables S6 and S7). The sequences were aligned using MAFFT v5 [69] in GENEIOUS R11 (Biomatters, Ltd.) with the default parameters set and were manually adjusted in MEGA 6.0 [66]. Maximum parsimony (MP) analyses were conducted using PAUP [70]. All characters were equally weighted, gaps were treated as missing, and character states were treated as unordered. Heuristic search was performed with MULPARS option, tree bisection-reconnection (TBR) branch swapping, and random stepwise addition with 1000 replications. The maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were performed using RAxML 8.0 [71]. For ML analyses, the best-fit model, general time reversible (GTR) + G was used with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Bayesian inference (BI) was performed with Mrbayes v3.2 [72]. The Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis was run for 1 × 108 generations. The trees were sampled at every 1000 generations with the first 20% discarded as burn-in. The remaining trees were used to build a 50% majority-rule consensus tree. The stationarity was considered to be reached when the average standard deviation of split frequencies remained below 0.001. Additionally, in order to test the utility of different cp regions, phylogenetic analyses were performed for the complete chloroplast genome sequences and the CDS sequences, respectively.

3.6. Chloroplast Genome Nucleotide Diversity and Positive Selected Analysis

The cp genome sequences were aligned using MAFFT v5 [69] and adjusted manually. Furthermore, a sliding window analysis was conducted for nucleotide diversity in LSC, SSC, and IR regions of the cp genomes using the DnaSP version 5.1 [73]. In addition, to identify the genes under positive selection in U. rockii and U. henryi, endemic to special karst environment, an optimized branch-site model [74] combined with Bayesian Empirical Bayes (BEB) methods [55] were used by comparison with their relatives. We firstly extracted all CDS sequences from U. rockii, U. henryi, S. adoxoides, and nine closely related species downloaded from GenBank (Table S6). The single-copy CDS sequences between these twelve species were obtained (see the Table S4). Each single-copy CDS sequence of these twelve species was aligned according to their amino acid sequence alignment generated by MUSCLE [75], and the “number of gaps” in the alignments was further checked. Then, the alignments of the corresponding DNA codon sequences were further trimmed by TRIMAL [76], and the bona fide alignments were used to support the subsequent positive selection analysis. The optimized branch-site model in the CODEML program implemented in the PAML 4 package [77] was used to assess potential positive selection affecting individual codons along a specifically designated lineage, which was set as U. rockii and U. henryi. Selective pressure is measured by the ratio (ω) of the nonsynonymous substitution rate (dN) to the synonymous substitutions rate (dS). A ratio ω > 1 indicates positive selection, ω = 1 implies neutral selection, and ω < 1 suggests negative selection [78]. Log-likelihood values were calculated in an alternative branch-site model (Model = 2; NSsites = 2; and Fix = 0) that allowed ω to vary among different codons along particular lineages and a neutral branch-site model (Model = 2; NSsites = 2; Fix = 1; Fix ω = 1) that confined the codon sites under neutral selection (ω = 1) on the basis of the likelihood ratio tests (LRT). The right-tailed chi-square test was performed to calculate the p values based on the difference in log-likelihood values between the alternative model and the neutral model with one degree of freedom to assess the model fit. Then, the p values were further adjusted according to multiple statistical tests [79]. A gene with an adjusted p value smaller than 0.05 and with positively selected sites was considered a positively selected gene (PSG). Moreover, in order to identify specific amino acid sites that are potentially under positive selection, a BEB method was implemented to calculate the posterior probabilities for sites classes. Codon sites with a high posterior probability were regarded as positively selected sites [54]. Jalview [80] was used to view the amino acid sequences of positively selected genes. In the end, in order to test the effectiveness of genes under positive selection, we randomly chose two genes to conduct the phylogenetic analyses.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Fang-Yu Jin, Hao Li, Fu-Min Xie, and Xin Yang for their help in materials collection.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/19/7/1847/s1.

Author Contributions

D.-F.X., Y.Y., S.-D.Z., and X.-J.H. conceived and designed the experiment; D.-F.X., J.L., and S.-D.Z. collected the materials; D.-F.X., Y.-Q.D., Y.Y., and H.-Y.L. participated in data analysis and manuscript drafting; D.-F.X., Y.-Q.D., X.-J.H., and S.-D.Z. revised the manuscript; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31470009, 31570198, 31500188), the Specimen Platform of China, Teaching Specimen’s sub-platform (Available website: http://mnh.scu.edu.cn/), the Science and Technology Basic Work (Grant No. 2013FY112100).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fu D.Z., Orbelia R.R. Flora of China. Volume 6. Science Press; Beijing, China: 2001. pp. 277–278. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie D.F., Li M.J., Tan J.B., Price M., Xiao Q.Y., Zhou S.D., He X.J. Phylogeography and genetic effects of habitat fragmentation on endemic Urophysa (Ranunculaceae) in Yungui Plateau and adjacent regions. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0186378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du B.G., Zhu D.Y., Yang Y.J., Shen J., Yang F.L., Su Z.Y. Living situation and protection strategies of endangered Urophysa rockii. Jiangsu J. Agri. Sci. 2010;1:324–325. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J.X., He X.J., Xu W., Meng W.K., Su Z.Y. Preliminary study on Urophysa rockii. II. Biological characteristics, ecological characteristics and community analysis. J. Sichuan For. Sci. Technol. 2011;32:28–39. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y.X., Hu H.Y., He X.J. Genetic diversity of Urophysa rockii Ulbrich, an endangered and rare species, detected by ISSR. Acta Bot. Boreal.-Occident. Sin. 2013;33:1098–1105. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y.X., Hu H.Y., Yang L.J., Wang C.B., He X.J. Seed dispersal and germination of an endangered and rare species Urophysa rockii (Ranunculaceae) Acta Bot. Boreal.-Occident. Sin. 2013;35:303–309. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park M., Park H., Lee H., Lee B.H., Lee J. The complete plastome sequence of an antarctic bryophyte Sanionia uncinata (hedw.) loeske. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:709. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong W.P., Liu H., Xu C., Zuo Y.J., Chen Z.J., Zhou S.L. A chloroplast genomic strategy for designing taxon specific DNA mini-barcodes: A case study on ginsengs. BMC Genet. 2014;15:138. doi: 10.1186/s12863-014-0138-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curci P.L., de Paola D., Danzi D., Vendramin G.G., Sonnante G. Complete chloroplast genome of the multifunctional crop Globe artichoke and comparison with other Asteraceae. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0120589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downie S.R., Jansen R.K. A comparative analysis of whole plastid genomes from the Apiales: Expansion and contraction of the inverted repeat, mitochondrial to plastid transfer of DNA, and identification of highly divergent noncoding regions. Syst. Bot. 2015;40:336–351. doi: 10.1600/036364415X686620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadachowska-Brzyska K., Li C., Smeds L., Zhang G.J., Ellegren H. Temporal dynamics of avian populations during pleistocene revealed by whole-genome sequences. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:1375–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suo Z.L., Li W.Y., Jin X.B., Zhang H.J. A new nuclear DNA marker revealing both microsatellite variations and single nucleotide polymorphic loci: A case study on classification of cultivars in Lagerstroemia indica L. J. Microb. Biochem. Technol. 2016;8:266–271. doi: 10.4172/1948-5948.1000296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saina J.K., Li Z.Z., Gichira A.W., Liao Y.Y. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima (mill.) (Sapindales: Simaroubaceae), an important pantropical tree. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:929. doi: 10.3390/ijms19040929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yurina N.P., Odintsova M.S. Comparative structural organization of plant chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes. Genetika. 1998;34:5–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jansen R.K., Raubeson L.A., Boore J.L., DePamphilis C.W., Chumley T.W., Haberle R.C., Wyman S.K., Alverson A., Peery R., Herman S.J., et al. Methods for obtaining and analyzing whole chloroplast genome sequences. Method Enzymol. 2005;395:348–384. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)95020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jansen R.K., Ruhlman T.A. Plastid Genomes of Seed Plants. In: Bock R., Knoop V., editors. Genomics of Chloroplasts and Mitochondria. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2012. pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi K.S., Chung M.G., Park S. The complete chloroplast genome sequences of three Veroniceae species (Plantaginaceae): Comparative analysis and highly divergent regions. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:355. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong W.L., Wang R.N., Zhang N.Y., Fan W.B., Fang M.F., Li Z.H. Molecular evolution of chloroplast genomes of orchid species: Insights into phylogenetic relationship and adaptive evolution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:716. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong W., Liu J., Yu J., Wang L., Zhou S. Highly variable chloroplast markers for evaluating plant phylogeny at low taxonomic levels and for DNA barcoding. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krak K., Vít P., Belyayev A., Douda J., Hreusová L., Mandák B. Allopolyploid origin of Chenopodium album s. str. (Chenopodiaceae): A molecular and cytogenetic insight. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0161063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith D.R. Mutation rates in plastid genomes: They are lower than you might think. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015;7:1227–1234. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansen R.K., Cai Z., Raubeson L.A., Daniell H., Depamphilis C.W., Leebensmack J., Müller K.F., Guisinger-Bellian M., Haberle R.C., Chumley T.W., et al. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:19369–19374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709121104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qian J., Song J., Gao H., Zhu Y., Xu J., Pang X. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of the medicinal plant Salvia miltiorrhiza. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e57607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asaf S., Waqas M., Khan A.L., Khan M.A., Kang S.M., Imran Q.M., Shahzad R., Bilal S., Yun B.W., Lee I.J., et al. The complete chloroplast genome of wild rice (Oryza minuta) and its comparison to related species. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:304. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu C., Tembrock L.R., Zheng S., Wu Z. The complete chloroplast genome of Catha edulis: A comparative analysis of genome features with related species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:525. doi: 10.3390/ijms19020525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang J., Chen R., Li X. Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genome of four known Ziziphus species. Genes. 2017;8:340. doi: 10.3390/genes8120340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yi X., Gao L., Wang B., Su Y.J., Wang T. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Cephalotaxus oliveri (Cephalotaxaceae): Evolutionary comparison of Cephalotaxus chloroplast DNAs and insights into the loss of inverted repeat copies in gymnosperms. Genome Biol. Evol. 2013;5:688–698. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cavalier-Smith T. Chloroplast evolution: Secondary symbiogenesis and multiple losses. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:62–64. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asano T., Tsudzuki T., Takahashi S., Shimada H., Kadowaki K. Complete nucleotide sequence of the sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) chloroplast genome: A comparative analysis of four monocot chloroplast genomes. DNA Res. 2004;11:93–99. doi: 10.1093/dnares/11.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Timme R.E., Kuehl J.V., Boore J.L., Jansen R.K. A comparative analysis of the Lactuca and Helianthus (Asteraceae) plastid genomes: Identification of divergent regions and categorization of shared repeats. Am. J. Bot. 2007;94:302–312. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nie X.J., Lv S.Z., Zhang Y.X., Du X.H., Wang L., Biradar S.S., Tan X.F., Wan F.H., Weining S. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of a major invasive species, crofton weed (Ageratina adenophora) PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong W.P., Xu C., Li D.L., Jin X.B., Lu Q., Suo Z.L. Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genome sequences in psammophytic Haloxylon species (Amaranthaceae) Peer J. 2016;4:e2699. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaur S., Panesar P.S., Bera M.B., Kaur V. Simple sequence repeat markers in genetic divergence and marker-assisted selection of rice cultivars: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015;55:41–49. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.646363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Y., Zhou T., Duan D., Yang J., Feng L., Zhao G. Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genomes of five Quercus species. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:959. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Powell W., Morgante M., McDevitt R., Vendramin G.G., Rafalski J.A. Polymorphic simple sequence repeat regions in chloroplast genomes-applications to the population genetics of pines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:7759–7763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Provan J., Corbett G., McNicol J.W., Powell W. Chloroplast DNA variability in wild and cultivated rice (Oryza spp.) revealed by polymorphic chloroplast simple sequence repeats. Genome. 1997;40:104–110. doi: 10.1139/g97-014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pauwels M., Vekemans X., Gode C., Frerot H., Castric V., Saumitou-Laprade P. Nuclear and chloroplast DNA phylogeography reveals vicariance among European populations of the model species for the study of metal tolerance, Arabidopsis halleri (Brassicaceae) New Phytol. 2012;193:916–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.04003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rose O., Falush D. A threshold size for microsatellite expansion. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1998;15:613–615. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raubeson L.A., Peery R., Chumley T.W., Dziubek C., Fourcade H.M., Boore J.L., Jansen R.K. Comparative chloroplast genomics: Analyses including new sequences from the angiosperms Nuphar advena and Ranunculus macranthus. BMC Genom. 2007;8:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huotari T., Korpelainen H. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Elodea Canadensis and comparative analyses with other monocot plastid genomes. Gene. 2012;508:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang W.B., Yu H., Wang J.H., Lei W.J., Gao J.H., Qiu X.P., Wang J.S. The complete chloroplast genome sequences of the medicinal plant Forsythia suspensa (Oleaceae) Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:2288. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asaf S., Khan A.L., Khan A.R., Waqas M., Kang S.M., Khan M.A., Lee S.M., Lee I.J. Complete chloroplast genome of Nicotiana otophora and its comparison with related species. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:447. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuang D.Y., Wu H., Wang Y.L., Gao L.M., Zhang S.Z., Lu L. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Magnolia kwangsiensis (Magnoliaceae): Implication for DNA barcoding and population genetics. Genome. 2011;54:663–673. doi: 10.1139/g11-026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen J., Hao Z., Xu H., Yang L., Liu G., Sheng Y. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of the relict woody plant Metasequoia glyptostroboides Hu et Cheng. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:447. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim K.J., Lee H.L. Complete chloroplast genome sequences from Korean ginseng (Panax schinseng Nees) and comparative analysis of sequence evolution among 17 vascular plants. DNA Res. 2004;11:247–261. doi: 10.1093/dnares/11.4.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu Y., Woeste K.E., Zhao P. Completion of the chloroplast genomes of five Chinese Juglans and their contribution to chloroplast phylogeny. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;7:1955. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang R.J., Cheng C.L., Chang C.C., Wu C.L., Su T.M., Chaw S.M. Dynamics and evolution of the inverted repeat-large single copy junctions in the chloroplast genomes of monocots. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008;8:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang M., Zhang X., Liu G., Yin Y., Chen K., Yun Q. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Z.Z., Saina J.K., Gichira A.W., Kyalo C.M., Wang Q.F., Chen J.M. Comparative genomics of the balsaminaceae sister genera Hydrocera triflora and Impatiens pinfanensis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:319. doi: 10.3390/ijms19010319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li C.Y. Classification and Systematics of the Aquilegiinae Tamura. The Chinese Academy of Science; Beijing, China: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bastida J.M., Alcántara J.M., Rey P.J., Vargas P., Herrera C.M. Extended phylogeny of Aquilegia: The biogeographical and ecological patterns of two simultaneous but contrasting radiations. Plant Syst. Evol. 2010;284:171–185. doi: 10.1007/s00606-009-0243-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fior S., Li M., Oxelman B., Viola R., Hodges S.A., Ometto L., Varotto C. Spatiotemporal reconstruction of the Aquilegia rapid radiation through next-generation sequencing of rapidly evolving cpDNA regions. New Phytol. 2013;198:579–592. doi: 10.1111/nph.12163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wei W., Lu A.M., Yi R., Endress M.E., Chen Z.D. Phytogeny and classification of Ranunculales: Evidence from four molecular loci and morphological data. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2009;11:81–110. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lan Y., Sun J., Tian R.M., Bartlett D.H., Li R.S., Wong Y.H., Zhang W.P., Qiu J.W., Xu T., He L.S., et al. Molecular adaptation in the world’s deepest-living animal: Insights from transcriptome sequencing of the hadal amphipod Hirondellea gigas. Mol. Ecol. 2017;26:3732–3743. doi: 10.1111/mec.14149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang Z., Wong W.S., Nielsen R. Bayes empirical Bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:1107–1118. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ai B., Gao Y., Zhang X., Tao J., Kang M., Huang H. Comparative transcriptome resources of eleven Primulina species, a group of ‘stone plants’ from a biodiversity hot spot. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2015;15:619–632. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muto A., Ushida C. Transcription and translation. Methods Cell Biol. 1995;48:483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Romanovsky Y.M., Tikhonov A.N. Molecular energy transducers of the living cell. Proton ATP synthase: A rotating molecular motor. Physics-Uspekhi. 2010;53:931–956. doi: 10.3367/UFNe.0180.201009b.0931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allahverdiyeva Y., Mamedov F., Mäenpää P., Vass I., Aro E.M. Modulation of photosynthetic electron transport in the absence of terminal electron acceptors: Characterization of the rbcL deletion mutant of tobacco. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2005;1709:69–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Piot A., Hackel J., Christin P.A., Besnard G. One-third of the plastid genes evolved under positive selection in PACMAD grasses. Planta. 2018;247:255–266. doi: 10.1007/s00425-017-2781-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kapralov M.V., Filatov D.A. Widespread positive selection in the photosynthetic Rubisco enzyme. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007;7:73–82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doyle J.J., Doyle J.L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull. 1987;19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wyman S.K., Jansen R.K., Boore J.L. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3252–3255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lohse M., Drechsel O., Kahlau S., Bock R. Organellar genome draw—A suite of tools for generating physical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes and visualizing expression data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:575. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kumar S., Nei M., Dudley J., Tamura K. MEGA: A biologist centric software for evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequences. Brief. Bioinform. 2008;9:299–306. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thiel T., Michalek W., Varshney R., Graner A. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 2003;106:411–422. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kurtz S., Choudhuri J.V., Ohlebusch E., Schleiermacher C., Stoye J., Giegerich R. REPuter: The manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Katoh K., Standley D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Swofford D.L. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods) Sinauer; Sunderland, MA, USA: 2003. Version 4b10. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: Maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ronquist F., Teslenko M., van der Mark P., Ayres D.L., Darling A., Hohna S., Larget B., Liu L., Suchard M.A., Huelsenbeck J. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Librado P., Rozas J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang Z., dos Reis M. Statistical properties of the branch-site test of positive selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:1217–1228. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Edgar R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Capella-Gutierrez S., Silla-Martínez J.M., Gabaldon T. TrimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang Z. PAML 4: Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang Z., Nielsen R. Codon-substitution models for detecting molecular adaptation at individual sites along specific lineages. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002;19:908–917. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Clamp M., Cuff J., Searle S.M., Barton G.J. The Jalview java alignment editor. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:426–427. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.