Abstract

Background:

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is an inflammatory demyelinating disease that selectively affects the optic nerves and spinal cord and generally follows a relapsing course. Therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) appears to be effective in patients with central nervous system inflammatory demyelinating disease who do not respond to first-line corticosteroid treatment.

Objective:

We represent a retrospective review of the use of TPE in the treatment of an acute attack of NMO in five patients who failed to respond to initial immunomodulatory treatment.

Materials and Methods:

We evaluated the effect of TPE on the degree of recovery from NMO. It was performed using a single volume plasma exchange with intermittent cell separator (Hemonetics Mobile Collection System plus) by femoral or central line access and scheduled preferably on alternate-day intervals from 8 to 10 days. Both subjective and objective clinical response to TPE was estimated, and final assessment of response was made at the time of the last TPE in the series.

Results:

All patients were severely disabled before the initiation of TPE and they were female; with the mean age of these patients was 52.5 years (range = 36-69 years), the median age of NMO diagnosis was 49.4 years (range = 35–65 years), and the median duration of disease was 2.6 years (range = 0–5 years). Out of five patients, three had a history of bilateral optic neuritis, and all patients were anti-against protein aquaporin-4antibody positive. Totally 24 TPE procedures were performed on five patients, the mean time of start of TPE in the acute attack was 18.6 days. Patients were severely disabled at the initiation of TPE (range = expanded disability status scale 6.5–9), and improvement was observed early in the course of TPE treatment in most patients.

Conclusion:

The present study provides clinical support for the importance of TPE in refractory acute attack in NMO. However, with new diagnostic technologies and increasing clinical awareness, we may see a more improved ways of TPE in these patients in the future; hence, TPE is more effective modality of treatment as it also removed the antibodies.

Keywords: Aquaporin antibody, neuromyelitis optica, therapeutic plasma exchange

INTRODUCTION

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is an inflammatory demyelinating disease that selectively affects the optic nerves and spinal cord and generally follows a relapsing course.[1] The clinical hallmark of the disease is a relapsing-remitting course of neurological deficits resulting in a step-wise deterioration of visual and neurological functions.[2] High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone is commonly used to treat the acute exacerbation of NMO, but some deficits deteriorate in spite of treatment. Therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) appears to be effective in patients with the central nervous system inflammatory demyelinating disease who do not respond to first-line corticosteroid treatment. The possible beneficial effect of TPE is through the elimination of pathogenic inflammatory mediators, including autoantibodies, complement components, and cytokines from the blood.[3] The NMO Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody is an IgG1 directed against protein aquaporin (AQP-4). This antibody is detected with tissue based immunofluorescence assay with a sensitivity and specificity more than 60% and 90%, respectively. Clinically diagnosed NMO patients share clinically common and evolutional characteristics regardless of their NMO IgG status. Beyond the surrogate marker value of NMO IgG, this marker is now used as a major diagnostic criterion.[4] Studies and case series have found that plasma exchange is effective in suppressing acute attacks in 50%–89% of patients with NMO, although the exact efficacy of plasma exchange for NMO attack was underestimated.[5,6,7,8] TPE is becoming the preferred standard rescue therapy for NMO patient when pharmacotherapy elicits only a weak or no response.[9,10] We represent a retrospective review of the use of TPE in the treatment of an acute attack of NMO in five patients who failed to respond to initial immunomodulatory treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

A retrospective review was performed on five patients of NMO who were treated at our institution from January 2013 to December 2016. All patients were diagnosed according to the currently NMO diagnostic criteria proposed by Wingerchuk et al.,[4] diagnosis of NMO can be made with high specificity if, absolute criteria is a history of at least one episode of Optic neuritis (ON) and one episode of myelitis, with two of the following three supporting criteria are met: (1) Contiguous spinal cord magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) lesion extending over three or more vertebral segments, (2) Brain MRI not meeting diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis, and (3). NMO-IgG positive. Patients fulfilling the above-diagnosed criteria who are refractory to high-dose corticosteroid treatment, or having worsening of neurological symptoms for >24 h, without evidence of new infection or explained by other underlying acute medical condition.[11] The timing of TPE commencement was determined by the neurologist, based on the patient clinical condition and subjectively when the patient did not achieve moderate or marked improvement after the initial treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone or deterioration in condition. Informed written consent to use the patient medical record for research was obtained at the time of first TPE.

Therapeutic plasma exchange protocol

Patient's blood counts, electrolytes, serum proteins, coagulation profile, and vitals were checked and appropriate steps were taken to correct the deranged parameters. The consent for the procedure was taken from the patient/patients relatives before the procedure. TPE was performed using a single volume plasma exchange with intermittent cell separator (Hemonetics Mobile Collection System plus, kit 980/790) machines by femoral or central line access using 12 French double lumen dialysis catheter. It was scheduled preferably on alternate-day intervals for 8 to 10 days. Anticoagulation with citrate was systematically used. Replacement of plasma removed during the session was performed with isotonic sterile saline, to make up one-half of the volume and with 5% purified human albumin and fresh frozen plasma to complete it. A careful monitoring of hemodynamic parameters was done, and complications during or following TPE were rapidly recognized and reverted by rationale interventions of the medical staff that assisted the procedure. Indications for TPE, number of cycles and sessions, duration of each session, the volume of plasma exchanged and patient tolerance to the procedure were systematically recorded. Calcium replacement with 10 ml of 10% calcium gluconate was infused over 15 min approximately halfway through the procedure to avoid citrate toxicity. Hemogram, serum electrolytes, total protein, and albumin were monitored daily. The immediate outcome was assessed shortly after each session, and overall outcome was assessed at the time of discharge. The amount of plasma to be exchanged should be determined in relation to the estimated plasma volume (EPV). A simple means of estimating, the EPV can be calculated from the patient's weight and hematocrit using the formula. EPV = (0.65 × wt [kg]) × [1 − Hcv].[12] We also assessed the adverse events during the TPE procedure in each patient.

Clinical evaluation

We evaluated the effect of TPE on the degree of recovery from NMO. Both subjective and objective clinical response to TPE was estimated by a transfusion medicine physician and neurologist independently. With each TPE, transfusion physician and neurologist evaluated all patients. The patient and transfusion medicine physician's final assessment of response was made at the time of the last TPE in the series. The treating neurologist's assessment of response was made at the time of the next neurological examination after the last TPE. The outcome of TPE was evaluated based on the criteria of Keegan et al.:[5] “no improvement” (no improvement in neurological symptoms or function), “mild improvement” (improvement in symptoms or examination, but with residual impairments in daily function), “moderate improvement” (improvement in primary symptoms but not completely resolved; no impairments in daily function), and “marked improvement” (complete resolution of symptoms). In each patient's neurological evaluation by pre- and post-TPE expanded disability status scale (EDSS) score was also performed, which is another measure of disability. Patient's characteristics and demographic profile and time of onset of improvement were noted. The assessment was made after completion of each cycle and at the end of completion of TPE.

RESULTS

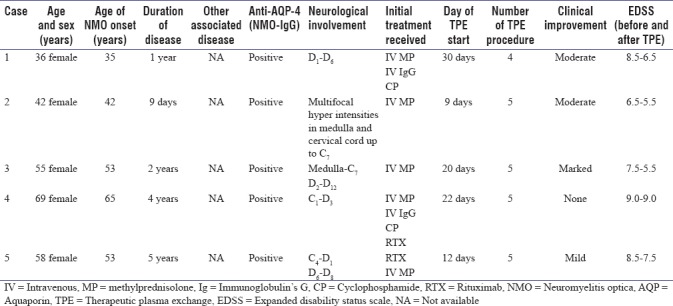

All five patients who fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of NMO and had undergone TPE for acute exacerbations after being refractory to high-dose steroid treatment which was given for 5 days and also repeated if there was worsening of symptoms for the next 5 days. Some of these patients also received other disease-modifying immune-modulatory therapies such as cyclophosphamide and rituximab during their course of the disease. All patients were severely disabled before the initiation of TPE. All patients were female; with the mean age of these patients was 52.5 years (range = 36–69 years), the median age of NMO diagnosis was 49.4 years (range = 35–65 years), and the median duration of disease was 2.6 years (range = 0–5 years). In our series, all patients had evidence of acute long segment myelitis with spinal cord lesions extending more than 3 vertebral segments (range = 3–12). Out of five patients, three had a prior history of bilateral optic neuritis, and all patients were anti-AQP-4 antibody positive. The other clinical characteristic and demographic profile of patients are summarized in Table 1. In our series, 24 TPE procedures were performed on five patients, the mean time of start of TPE in the acute attack was 18.6 days, the mean number of TPE session was 4.4 (standard deviation [SD] ±1.2), the mean volume of plasma exchange was 2875 ml (SD ± 125) and mean time duration of a session was 270 min (SD ± 35). All the procedures were well-tolerated with only transient adverse events, all of which were successfully resolved with no residual sequelae. In our series, we noticed minor side such as citrate toxicity in 2 (8.3%) procedures which was managed with intravenous calcium, hypotension in 1 (4.2%) during the procedure, which was also readily corrected with intravenous fluids or temporarily halting the TPE procedure, catheter-related problem were noticed in 2 (8.3%) which was properly managed by critical care team and allergic reaction to fresh frozen plasma in 1 (4.2%) procedures which was managed by antihistamine. No infections and death occur in consequences of TPE in our case series. Good TPE acceptance occurs in 75% of procedures. The therapeutic efficacy of TPE was remarkable, all the patients showed improvement which started after two cycles of plasma exchange. There was marked improvement in 1 (20%) patient (case 3), moderate improvement in 2 (40%) patients (case 1 and 2), and mild improvement in 1 (20%) patient (case 5) and there was no improvement seen in 1 (20%) patient (case 4) as per the Keegan et al. criteria.[5] Patients were severely disabled at the initiation of TPE (range = EDSS 6.5–9) and improvement was observed early in the course of TPE treatment in most patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients undergoing therapeutic plasma exchange

DISCUSSION

Initially NMO, long considered as a clinical variant of multiple sclerosis; is now considered as a distinct debilitating autoimmune neurological disorder. In recent years, major progress has been made in the diagnosis as well as treatment of NMO. After standard neurological examination and the exclusion of infection, steroids are the initial standard treatment given for 5 consecutive days in a dose of 1 g methyl prednisolone per day intravenously. If the patient's condition does not sufficiently improve or the neurological symptom worsens, TPE was performed after taking patient consent. In our case series, we analysed the clinical effectiveness of TPE in five patients who were steroid refractory, seropositive NMO fulfilling the NMO disease criteria. Two out of five patients were also refractory to other modifying therapies responded to TPE. In our study, we observed that four patients show neurological improvement after initiation of TPE and improvement were noted after the second cycle. The average mean time of start of TPE after the acute episode was 16–20 days. The immediate response to TPE as a disease-modifying therapy in acute episode suggests a significant reduction in anti-AQP-4 antibody levels, although we had not estimated the level of antibody. Previous studies had suggested that five or six plasma exchange sessions are required to substantially reduce the blood antibody level of IgG by an 85%.[9,13,14,15] In three of our patients, there was a significant improvement (60%, moderate/marked), whereas one patient (20%) had mild improvement, and another patient (20%) did not show any improvement in his neurological status after completion of five cycles of TPE. The response rate of TPE in our series was 60%–80% which was compared to response rate observed in other series.[5,6,7,8,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] In our series, we also used the EDSS for neurological disability assessment as four of our patients had improvement in the EDSS score as compared to their preTPE score.[8,13,16] The one patient who does not respond to TPE had also received other immune therapies in the past after which also there was no improvement. It might be possible that it represents severe form of NMO which has malignant course hence showed no neurological improvement even to TPE.[10] TPE is a relatively safe and well-tolerated effective procedure for treatment of an acute refractory attack of NMO. The study has a total of 6 adverse events noted in over 24 procedures of TPE giving an overall adverse event rate of 25%. Although this rate is higher than published in previous studies (ranged 4.6%–21%).[19,20,21] All these adverse events were minor and successfully resolved with no sequelae. They include citrate toxicity, hypotension, catheter-related problems, and allergic reaction.

Furthermore, understanding the physiological changes that occur during aphaeresis and knowledge of underline medical condition in the patients that could predispose them toward these reactions would allow for early intervention and potentially lessening these reactions. The limitation of this study is that our study was a retrospective with small sample size. There have been several retrospective studies which have shown a favorable response, but no randomized controlled trial (RCTs) had been done on TPE in the patients with NMO disease. As NMO is a rare disease, hence there is limited evidence for the efficacy of TPE and also the ethical difficulties in conducting RCTs.[22] Steroids have an only immunomodulatory effect, and they do not remove the antibodies; hence, significant improvement after steroid may not be noticed in all patients.[10,23] The study data provide clinical support for the importance of TPE in a refractory acute attack in NMO. However, with new diagnostic technologies and increasing clinical awareness, we may see a more improved ways of TPE in these patients in the future; hence, TPE is the more effective modality of treatment as it also removed the antibodies.

CONCLUSION

This study suggests that acute attack of NMO can be safely and effectively treated with TPE, which results in marked improvement in the neurological status. Although further studies are needed to examine which clinical characteristics and profile may predict a better response to TPE and whether this treatment should be used for all patients with NMO who also have brain involvement. Furthermore, the timing of the start of TPE is another factor which needs to be answered in future studies, may be suggested that the earlier we start TPE in an acute attack, the better will determine the clinical outcome. We suggest TPE should be included as a potential disease-modifying therapy for patients who are refractory to steroid or other immunomodulatory therapies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wingerchuk DM, Hogancamp WF, O'Brien PC, Weinshenker BG. The clinical course of neuromyelitis optica (Devic's syndrome) Neurology. 1999;53:1107–14. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucchinetti CF, Mandler RN, McGavern D, Bruck W, Gleich G, Ransohoff RM, et al. A role of humoral mechanism in the pathogenesis of devic's neuromyelitis optica. Brain. 2002;125:1450–61. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehmann HC, Hartung HP, Hetzel GR, Stuve O, Kieseier BC. Plasma exchange in neuro-immunological disorders: Part 1: Rationale and treatment of inflammatory central nervous system disorders. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:930–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.7.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2006;66:1485–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216139.44259.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keegan M, Pineda AA, McClelland RL, Darby CH, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG, et al. Plasma exchange for severe attacks of CNS demyelination: Predictors of response. Neurology. 2002;58:143–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llufriu S, Castillo J, Blanco Y, Ramió-Torrentà L, Río J, Vallès M, et al. Plasma exchange for acute attacks of CNS demyelination: Predictors of improvement at 6 months. Neurology. 2009;73:949–53. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b879be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe S, Nakashima I, Misu T, Miyazawa I, Shiga Y, Fujihara K, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of plasma exchange in NMO-igG-positive patients with neuromyelitis optica. Mult Scler. 2007;13:128–32. doi: 10.1177/1352458506071174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang KC, Wang SJ, Lee CL, Chen SY, Tsai CP. The rescue effect of plasma exchange for neuromyelitis optica. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:43–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonnan M, Cabre P. Plasma exchange in severe attacks of neuromyelitis optica. Mult Scler Int. 2012;2012:787630. doi: 10.1155/2012/787630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khatri BO, Kramer J, Dukic M, Palencia M, Verre W. Maintenance plasma exchange therapy for steroid-refractory neuromyelitis optica. J Clin Apher. 2012;27:183–92. doi: 10.1002/jca.21215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magaña SM, Keegan BM, Weinshenker BG, Erickson BJ, Pittock SJ, Lennon VA, et al. Beneficial plasma exchange response in central nervous system inflammatory demyelination. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:870–8. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan AA. A simple and accurate method for prescribing plasma exchange. ASAIO Trans. 1990;36:M597–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonnan M, Valentino R, Olindo S, Mehdaoui H, Smadja D, Cabre P, et al. Plasma exchange in severe spinal attacks associated with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Mult Scler. 2009;15:487–92. doi: 10.1177/1352458508100837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brecher ME. Plasma exchange: Why we do what we do. J Clin Apher. 2002;17:207–11. doi: 10.1002/jca.10041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SH, Kim W, Huh SY, Lee KY, Jung IJ, Kim HJ, et al. Clinical efficacy of plasmapheresis in patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and effects on circulating anti-aquaporin-4 antibody levels. J Clin Neurol. 2013;9:36–42. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2013.9.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merle H, Olindo S, Jeannin S, Valentino R, Mehdaoui H, Cabot F, et al. Treatment of optic neuritis by plasma exchange in neuromyelitis optica. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:858–62. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim YM, Pyun SY, Kang BH, Kim J, Kim KK. Factors associated with the effectiveness of plasma exchange for the treatment of NMO-igG-positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Mult Scler. 2013;19:1216–8. doi: 10.1177/1352458512471875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munemoto M, Otaki Y, Kasama S, Nanami M, Tokuyama M, Yahiro M, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of double filtration plasmapheresis in patients with anti-aquaporin-4 antibody-positive multiple sclerosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:478–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.07.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madore F. Plasmapheresis. Technical aspects and indications. Crit Care Clin. 2002;18:375–92. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(01)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiprov DD, Golden P, Rohe R, Smith S, Hofmann J, Hunnicutt J, et al. Adverse reactions associated with mobile therapeutic apheresis: Analysis of 17,940 procedures. J Clin Apher. 2001;16:130–3. doi: 10.1002/jca.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan AA. Therapeutic plasma exchange: A technical and operational review. J Clin Apher. 2013;28:3–10. doi: 10.1002/jca.21257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan SM, Zantek ND, Carpenter AF. Therapeutic plasma exchange in neuromyelitis optica: A case series. J Clin Apher. 2014;29:171–7. doi: 10.1002/jca.21304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abboud H, Petrak A, Mealy M, Sasidharan S, Siddique L, Levy M, et al. Treatment of acute relapses in neuromyelitis optica: Steroids alone versus steroids plus plasma exchange. Mult Scler. 2016;22:185–92. doi: 10.1177/1352458515581438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]