Abstract

Background

Behavioural problems are common among children with Down syndrome (DS). Tools to detect and evaluate maladaptive behaviours have been developed for typically developing (TD) children and have been evaluated for use among children with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD). However, these measures have not been evaluated for use specifically in children with DS. This psychometric evaluation is important given that some clinically observed behaviours are not addressed in currently available rating scales. The current study evaluates the psychometric properties of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), a commonly used screening tool developed for TD children and commonly used with children with IDD.

Method

The study investigated psychometric properties of the CBCL among school-age children with DS, including an assessment of the rate of detecting behaviour problems, concerns with distribution, internal consistency, inter-rater reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity with the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) and Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form (NCBRF). Caregivers of 88 children with DS aged 6–18 years rated their child’s behaviour with the CBCL, ABC, and NCBRF. Teachers completed the Teacher Report Form (TRF).

Results

About 1/3 of children with DS were reported to exhibit behaviours of clinical concern on the total score of the CBCL. Internal consistency for CBCL subscales was poor to excellent, and inter-rater reliability was generally acceptable. The subscales of the CBCL performed best when evaluating convergent validity, with variable discriminant validity. Normative data conversions controlled for age and gender differences in this sample.

Conclusion

The study findings suggest that, among children with DS, some CBCL subscales generally performed in a psychometrically sound and theoretically appropriate manner in relation to other measures of behaviour. Caution is warranted when interpreting specific subscales (Anxious/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, and Thought Problems). The CBCL can continue to be used as a screening measure when evaluating behavioural concerns among children with DS, acknowledging poor discriminant validity and that key behaviour concerns in DS may not be captured by the CBCL screen.

Keywords: Down syndrome, trisomy 21, behaviour, measurement, children

Children with Down syndrome (DS) exhibit a range of maladaptive behaviours, with reported rates of 18–43% (Capone, Goyal, Ares, & Lannigan, 2006; Dykens & Kasari, 1997; Dykens et al., 2015; Patel, Wolter-Warmerdam, Leifer, & Hickey, in press; Visootsak & Sherman, 2007). Rates of maladaptive behaviours are reported to be higher in children with DS than in typically developing children, and continue to be a concern after controlling for developmental level (Capone et al., 2006; Coe et al., 1999; Cuskelly & Dadds, 1992; Evans, Canavera, Kleinpeter, Maccubbin, & Taga, 2005; Evans & Gray, 2000; Feeley & Jones, 2008; Foley et al., 2015; Gath & Gumley, 1986; Glenn & Cunningham, 2007; Loveland & Kelley, 1991; Nicham et al., 2003; Pitcairn & Wishart, 1994; Pueschel, Bernier, & Pezzullo, 1991; van Gameren-Oosterom et al., 2011). Common maladaptive behaviours include noncompliance, inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (Cornish, Steele, Monteiro, Karmiloff-Smith, & Scerif, 2012; Dykens & Kasari, 1997). Contributing factors to these maladaptive behaviours in individuals with DS can include weaknesses in executive functioning, processing speed, learning, coping with stressors, the environment, and comorbid psychopathology (Daunhauer, Fidler, & Will, 2014; Jacola, Hickey, Howe, Esbensen, & Shear, 2014). Maladaptive behaviours have a negative impact on the family and home environment, and often serve as a reaction to academic or vocational demands, transitions, or changes (Owen et al., 2004; Roach, 1999; Sanders, 1997). Thus, maladaptive behaviours are a significant concern for children with DS.

Down syndrome working groups were formed by the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) to evaluate clinical outcome measures for use with individuals with DS, including measures of maladaptive behaviour (NICHD, 2015). There currently are multiple informant-report measures of maladaptive behaviour available that are used with individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) that were developed for typically developing (TD) children. For example, the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC) and Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) are commonly used to assess maladaptive behaviours and screen for mental health concerns in children with TD and IDD (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015). Other measures of maladaptive behaviours were developed for individuals with IDD more generally, such as the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC), Behavior Problem Inventory (BPI), Developmental Behavior Checklist (DBC), and Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Form (NCBRF) (Aman, Singh, Stewart, & Field, 1985a; Aman, Tassé, Rojahn, & Hammer, 1996; Einfeld & Tonge, 1995; Rojahn, Matson, Lott, Esbensen, & Smalls, 2001). In addition, there are measures to assess specific symptoms of concern, such as repetitive behaviours (Repetitive Behavior Scale – RBS-R). The NIH DS Working Group rated currently available measures of maladaptive behaviour as being appropriate for individuals with IDD (ABC, BPI, DBC, NCBRF, RBS-R), or whether the measures were in need of modification or were promising for use with individuals with DS (BASC, CBCL) (Esbensen et al., 2017). However, no measure of maladaptive behaviours was rated as being appropriate or validated for use with individuals with DS. While studies have reported on the prevalence of behavioural concerns specifically in children with DS, few studies have examined the psychometric properties of behavioural measures specifically for use with individuals with DS (Dykens & Kasari, 1997; Fidler, Hodapp, & Dykens, 2000). Among adolescents with DS, the CBCL demonstrates limited convergent validity with the BASC-2 (Jacola et al., 2014).

The NIH DS Working Groups identified the need for establishing valid outcome measures to detect treatment changes in clinical trials, and the lack of empirical evidence for using currently available measures with individuals with DS (Esbensen et al., 2017; NICHD, 2015). Behavioural outcomes that were especially in need of development included noncompliance, self-regulation of emotions and behaviour, and coping with transitions. This priority is reinforced by recent findings that measures developed for individuals with IDD may be omitting key behaviours of concern in individuals with DS (Patel et al., in press). Key behaviours of concern in DS that are not adequately captured on commonly used measures of maladaptive behaviour include wandering, self-stimulatory behaviours, insistence on sameness, and self-talk (Feeley & Jones, 2008; McGuire & Chicoine, 2006; Patel et al., in press; Stein, 2016). By inadequately assessing maladaptive behaviours, currently available measures of behaviour may not be valid or sensitive to treatment change, and may have contributed to the wide range in reported behaviour problems.

Measures of maladaptive behaviour developed for typically developing children generally have age- and gender-based normative data and thus are most useful in clinical settings. Few measures developed for individuals with IDD have threshold scores or account for the impact of age and gender on the presentation of maladaptive behaviours. The importance of evaluating age in relation to maladaptive behaviours is highlighted by age effects in children with DS on all subscales of the CBCL when assessing raw scores (Dykens, Shah, Sagun, Beck, & King, 2002). Thus, individuals with the DS behavioural phenotype may be developing at a different pace in terms of maladaptive behaviours. Gender differences in maladaptive behaviours are also present in children with DS, with inconsistent patterns of findings (Dykens et al., 2015; Jacola et al., 2014; Määttä, Tervo-Määttä, Taanila, Kaski, & Iivanainen; van Gameren-Oosterom et al., 2013).

Given the concern for, and variable rates of maladaptive behaviour, as well as the lack of empirically supported measures of maladaptive behaviour in children with DS, this study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the CBCL for use with children with DS. First, we described the rates of different maladaptive behaviour problems among subscales, and among DSM-Oriented clinical domains to understand the pattern of behaviours of concern. Second, we examined the internal consistency of the CBCL and its subscales. Third, we examined the inter-rater reliability of subscales on the CBCL and TRF. Fourth, we examined the convergent and discriminant validity of the CBCL and its subscales with two measures developed for and validated with children with IDD more broadly, specifically the ABC and NCBRF. Last, we examined age and gender differences on the CBCL subscales and domains, for both raw and t-scores. Understanding the psychometric properties of the CBCL with children with DS will inform the use of this measure and support the identification of reliable measures when reporting maladaptive behaviour problems.

Method

Participants

Parents of 88 children with DS completed rating forms as part of several larger clinical and community-based studies on behaviour and cognition. Data from these studies were combined post-hoc for the current proposed analyses. Children with DS ranged in age from 6 to 18 years of age (M = 11.35 years, SD = 3.02), were primarily male (61.4%) and Caucasian (83.0%). Standard scores were obtained on different measures of cognition, depending on the clinical or research purpose. Standard IQ scores are summarised in Table 1 by cognitive test. Respondents were primarily mothers (92%), with fathers completing 3% of forms and both parents working together to complete 5% of forms.

Table 1.

Mean standard scores on measures of cognition.

| n | Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAS-II General Conceptual Ability | 24 | 43.04 (10.84) | 25–65 |

| Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV | 5 | 47.80 (8.20) | 40–60 |

| Stanford-Binet-5 | 7 | 47.86 (2.27) | 47–53 |

| Leiter-R | 1 | 38.00 (---) | --- |

| Kaufman Brief Test of Intelligence | 48 | 43.50 (4.89) | 40–57 |

Procedure

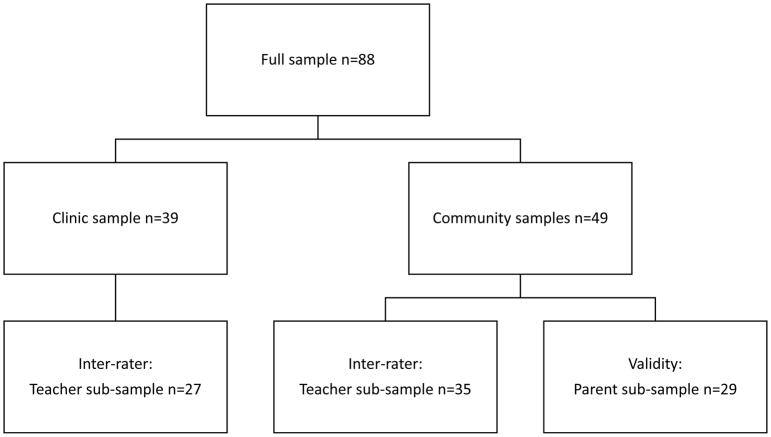

Families were recruited based on the age of the child and a diagnosis of DS. Families were recruited through a paediatric medical centre, a DS specialty clinic, and through newsletters distributed by the local DS association. Clinical chart review contributed 39 children to the current sample where parent and teacher ratings of behaviour were documented (see Figure 1). The remaining children were recruited from community studies on DS. In community studies, parents provided information on the child’s demographics and completed rating scales of the child’s behaviour on the CBCL. A subset of 29 parents completed additional rating scales of child’s behaviour on the ABC and NCBRF. Within a week, teachers also completed behavioural rating forms on the TRF that were distributed and collected through parents. Teacher reports were collected from 62 teachers across community studies and clinical records. Teacher reports were not documented in 12 clinical charts, were not obtained for 12 children in community-recruited research studies as the child was on school break, and were not obtained as part of the study protocol in one research study involving 2 children. All study activities were approved and overseen by the Institutional Review Board at the medical centre.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of samples included in analysis

Measures

The Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) for children ages 6–18 years obtains parent ratings of 112 problem behaviours, in addition to descriptions of their child’s strengths and challenges (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The Teacher Rating Form (TRF) is completed by teachers rating problem behaviour. Both the CBCL and TRF assess symptoms on the following subscale: Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Rule-Breaking Behavior and Aggressive Behavior. An Internalizing Problems score is derived from symptoms on the Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, and Somatic Complaints subscales. An Externalizing Problems score is derived from symptoms of Rule-Breaking Behavior and Aggressive Behavior. In addition to a Total Problems score, six DSM-Oriented subscales are also assessed on the CBCL and TRF, including Affective Problems, Anxiety Problems, Somatic Problems, Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems, Oppositional Defiant Problems and Conduct Problems. Internal consistency and one-week test-retest reliability ranges from good to excellent for each of the domains with TD children (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Internal consistency is moderate to high for all composite and syndrome scales with children with IDD (Jacola et al., 2014). Items are rated on a 3-point scale from (0) not true to (2) very true, and t-scores are created based on an age and gender normative sample. Approximately 6% of typically developing children are expected to have t-scores above the threshold score of 65.

The Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) is a rating scale of maladaptive behaviours for children and adults with IDD (Aman et al., 1985a; Aman, Singh, Stewart, & Field, 1985b). Subscales assess Irritability, Lethargy, Stereotypic Behaviours, Hyperactivity, and Inappropriate Speech. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale from (0) not at all a problem to (3) the problem is severe in degree. Internal consistency is good to excellent, inter-rater reliability is moderate and retest reliability extremely high (Aman et al., 1985b).

The Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Forms (NCBRF) for parents and teachers measures adaptive and maladaptive behaviours among children with IDD (Aman et al., 1996). Adaptive subscales assess Compliant/Calm and Adaptive/Social. Maladaptive subscales assess Conduct Problems, Insecurity, Hyperactivity, Self-Injury, Ritualistic Behaviours, and Sensitivity. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale from behaviour did not occur or was not a problem (scored 0) to behaviour occurred a lot or was a severe problem (scored 3). The NCBRF demonstrates high inter-rater reliability between parent and teacher forms on all scales and high internal consistency for multiple subscales (Aman et al., 1996).

Data Analysis

For the purpose of the current analyses, raw total and mean standardised scores were calculated for the CBCL subscales and DSM-Oriented subscales. The percentage of children scoring above the clinical range of concern was calculated. The clinical range of concern was considered a t-score above 65 (1.5 standard deviations above the mean; >94th percentile), consistent with recommendations in the CBCL (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The distribution of subscale (t- and raw) scores was assessed and concerns with skew or kurtosis identified. Skew was considered a concern if the statistic was less than -0.8 or greater than 0.8. Kurtosis was considered a concern if the statistic was less than -3.0 or greater than 3.0.

Internal consistency of each subscale was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha. Internal consistency measures whether items proposed to measure the same construct produce similar scores. Interrater-reliability was calculated using the two-way mixed average measures form of intra-class coefficients (ICC) comparing corresponding subscales on the CBCL and TRF. Inter-rater reliability assesses the degree to which different raters give consistent estimates of the same items.

Convergent and discriminant validity was explored by correlating subscales on the CBCL subscale and DSM-oriented subscales with the subscales from the ABC and NCBRF. Convergent validity assesses the degree to which measures of a construct that should be related to each other are in fact related to each other. Discriminant validity assesses the degree to which measures that are not supposed to be related are actually unrelated. Authors developed a priori hypotheses for subscales that should demonstrate convergence.

To assess for possible gender differences on subscale scores, t-tests were conducted on the CBCL raw and t-scores. Correlations were run to assess for possible associations with age on the CBCL raw and t-scores.

Results

Group differences were run to assess comparability between community and clinical samples. Samples did not differ on age (t(86) = 1.46, p = .15), gender (χ(1)2 = .00, p = .98), race (χ(3)2 = 4.14, p = .25) or IQ (t(80) = 0.02, p = .99). Children from the clinic sample were reported to have higher t-scores on subscales of Anxious/Depressed (t(86) = 2.08, p = .04), Aggressive Behavior (t(86) = 2.28, p = .02), Total Problems (t(58) = 2.08, p = .04), Somatic Problems (t(66) = 2.31, p = .02), and Conduct Problems (t(67) = 2.25, p = .03).

Frequency of Behaviour Problems

Table 2 presents the mean t-scores and standard deviations for CBCL subscales and DSM-oriented subscales and the rates at which children met clinical criteria for subscales. The range of t-scores is presented, as well as whether the distribution of scores on a subscale presented with concerns for skew or kurtosis. On the CBCL subtests, over 40% of children with DS in the sample met the criteria for clinical concern for Thought Problems and Attention Problems. The behaviour of least concern was Anxious/Depressed, with only 4% of children with DS meeting the criteria for clinical concern on this subscale. On the CBCL DSM-Oriented subscales, between 12–28% of children met the criteria for clinical concern on any subscale. The distribution of subscale scores was sometimes skewed, with 3 of 8 CBCL subscales and 4 of 6 DSM-Oriented subscales demonstrating concerns with positive skew. Kurtosis (leptokurtic distribution or positive kurtosis) is a concern for the Anxious/Depressed subscale and the Somatic Problems DSM-Oriented subscale, suggesting a dichotomous response pattern.

Table 2.

Psychometric properties of CBCL subscale and DSM-oriented subscales.

| n | Mean (SD) | Range | Clinical concern | Skew | Kurtosis | Alpha | Inter-rater reliability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxious/Depressed | 88 | 53.47 (5.55) | 50–74 | 4.5% | r,t | r,t | .77 | .28 |

| Withdrawn/Depressed | 88 | 58.40 (8.16) | 50–81 | 23.9% | r,t | .74 | .51** | |

| Somatic Complaints | 88 | 56.57 (6.16) | 50–76 | 10.2% | r | .58 | .24 | |

| Social Problems | 87 | 60.56 (6.54) | 50–78 | 25.3% | r | .74 | .44* | |

| Thought Problems | 87 | 63.46 (8.62) | 50–79 | 44.8% | .61 | .38* | ||

| Attention Problems | 88 | 63.03 (8.08) | 50–90 | 44.3% | .78 | .57** | ||

| Rule-Breaking Behavior | 87 | 56.48 (6.17) | 50–73 | 11.5% | r,t | .58 | .68** | |

| Aggressive Behavior | 88 | 58.99 (8.51) | 50–82 | 28.4% | .90 | .65** | ||

| Internalizing Problems | 84 | 53.21 (10.16) | 33–73 | 14.3% | .84 | .46* | ||

| Externalizing Problems | 84 | 56.17 (10.36) | 33–76 | 22.6% | .90 | .70** | ||

| Total Problems | 60 | 59.48 (9.11) | 38–78 | 33.3% | .94 | .65** | ||

| DSM-Oriented | ||||||||

| Affective Problems | 69 | 59.07 (7.60) | 50–76 | 21.7% | .58 | .05 | ||

| Anxiety Problems | 69 | 57.10 (7.61) | 50–80 | 24.6% | r,t | r | .73 | .37 |

| Somatic Problems | 68 | 56.25 (7.02) | 50–87 | 11.8% | r,t | r,t | .63 | −.01a |

| ADH Problems | 69 | 59.62 (7.91) | 50–80 | 27.5% | .85 | .65** | ||

| Oppositional Defiant Problems | 69 | 59.17 (8.02) | 50–80 | 18.8% | t | .85 | .52** | |

| Conduct Problems | 69 | 57.23 (7.32) | 50–78 | 20.3% | r,t | .79 | .73** | |

p < .05,

p < .01

not computed due to negative average covariance among items and violation of reliability model assumptions.

r Areas of concern for raw scores

t Areas of concern for t-score

Internal Consistency

The alpha coefficients for the CBCL subscale and DSM-Oriented subscale scores are presented in Table 2. The alpha coefficients for the CBCL subscales ranged from .58 (poor) to .94 (excellent). Two subscales presented with poor internal consistency (Somatic Complaints, and Rule-Breaking Behavior), one with questionable internal consistency (Though Problems), and four with acceptable internal consistency (Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Social Problems and Attention Problems). Only one subscale presented with excellent internal consistency (Aggressive Behavior) in this sample of children with DS. Internalizing Problems demonstrated good internal consistency and Externalizing Problems and Total Problems both demonstrated excellent internal consistency.

Internal consistency for the DSM-Oriented subscales ranged from .58 (poor) to .85 (good). One subscale presented with poor internal consistency (Affective Problems), one with questionable internal consistency (Somatic Problems), and two with acceptable internal consistency (Anxiety Problems and Conduct Problems). Two subscales (Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems, and Oppositional Defiant Problems) presented with good internal consistency in this sample of children with DS.

Interrater-reliability

Inter-rater reliability ICC for the CBCL subscale and DSM-Oriented subscale scores are presented in Table 2. Most CBCL and DSM-Oriented subscales demonstrated statistically significant ICC values, demonstrating agreement among parent- and teacher-ratings on the behavioural measures. However, the ICC estimates ranged from poor (values less than 0.5) to moderate (values between 0.5 and 0.75) (Koo & Li, 2016).

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Validity between theoretically related subscales on the CBCL and ABC provided variable results (see Table 3). Evidence for convergent validity of CBCL subscales was present for Anxious/Depressed (with Irritability and Lethargy of ABC), Withdrawn/Depressed (with Lethargy of ABC), Thought Problems (with Stereotypy of ABC), Attention Problems (with Hyperactivity of ABC), Rule-Breaking Behavior (with Irritability of ABC), and Aggressive Behavior (with Irritability of ABC). Social Problems did not demonstrate convergent validity with any subscale on the ABC. Evidence of convergent validity was also present for CBCL DSM-Oriented subscales with the ABC, including for Affective Problems (with Lethargy of ABC), Anxiety Problems (with Irritability and Lethargy of ABC), Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems (with Hyperactivity of ABC), Oppositional Defiant Problems (with Irritability of ABC) and Conduct Problems (with Irritability of ABC). However, these subscales on the CBCL also correlated with several other subscales of the ABC, inconsistent with a priori hypotheses, thus demonstrating poor discriminant validity (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Convergent validity of CBCL subscales and DSM-oriented subscales with ABC (n=29).

| Irritability | Lethargy | Stereotypy | Hyperactivity | Inappropriate Speech | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxious/Depressed | .73** | .38* | .27 | .69** | .40* |

| Withdrawn/Depressed | .03 | .82** | .42* | −.01 | .02 |

| Somatic Complaints | .56** | .22 | .28 | .52** | .46* |

| Social Problems | .20 | .52** | .52** | .12 | .34 |

| Thought Problems | .35 | .39* | .44* | .30 | .35 |

| Attention Problems | .50** | .39* | .23 | .52** | .48** |

| Rule-Breaking Behavior | .65** | .15 | .26 | .46** | .40* |

| Aggressive Behavior | .89** | .01 | .21 | .81** | .61** |

| Internalizing Problems | .40* | .64** | .37* | .30 | .29 |

| Externalizing Problems | .82** | .07 | .28 | .77** | .48** |

| Total Problems | .66** | .48** | .41* | .60** | .53** |

| DSM-Oriented | |||||

| Affective Problems | .29 | .48** | .61** | .35 | .22 |

| Anxiety Problems | .68** | .40* | .16 | .58** | .48** |

| Somatic Problems | .53** | .18 | .24 | .56** | .31 |

| ADH Problems | .74** | .09 | .12 | .74** | .54** |

| Oppositional Defiant Problems | .89** | −.08 | .07 | .79** | .62** |

| Conduct Problems | .80** | .10 | .17 | .65** | .55** |

p < .05,

p < .01

Note: Bold and underlined reflect relationships hypothesized to establish convergent validity.

Convergent validity between theoretically related subscales on the CBCL and NCBRF also provided variable results depending on the construct being explored (see Table 4). Evidence of convergent validity of CBCL subscales was present for Anxious/Depressed (with Insecure/Anxious and Self-Injury/Stereotypic of NCBRF), Withdrawn/Depressed (with Self-Isolated/Ritualistic of NCBRF), Social Problems (with Self-Isolated/Ritualistic of NCBRF), Thought Problems (Self-Injury/Stereotypic and Self-Isolated/Ritualistic of NCBRF), Attention Problems (Hyperactive of NCBRF), Rule-Breaking Behavior (Conduct Problem of NCBRF) and Aggressive Behavior (Conduct Problem of NCBRF). Evidence of convergent validity was also present for CBCL DSM-Oriented subscales, including for Affective Problems (with Self-Isolated/Ritualistic of NCBRF), Anxiety Problems (with Insecure/Anxious and Self-Injury/Stereotypic of NCBRF), Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems (Hyperactive of NCBRF), Oppositional Defiant Problems (Conduct Problem of NCBRF) and Conduct Problems (Conduct Problem of NCBRF). However, these subscales on the CBCL also correlated with several other subscales of the NCBRF, inconsistent with a priori hypotheses, thus demonstrating poor discriminant validity (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Convergent validity of CBCL subscales and DSM-oriented subscales with NCBRF (n=29).

| Conduct Problem | Insecure/ Anxious | Hyperactive | Self-Injury/ Stereotypic | Self-isolated/ Ritualistic | Overly Sensitive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxious/Depressed | .78** | .85** | .71** | .61** | .45* | .41* |

| Withdrawn/Depressed | −.04 | .23 | .08 | .44* | .83** | .22 |

| Somatic Complaints | .60** | .57** | .55** | .36 | .22 | .26 |

| Social Problems | .09 | .33 | .31 | .39* | .50** | .40* |

| Thought Problems | .51** | .64** | .55** | .49** | .45* | .38* |

| Attention Problems | .43* | .53** | .68** | .38* | .45* | .50** |

| Rule-Breaking Behavior | .57** | .51** | .61** | .35 | .32 | .34 |

| Aggressive Behavior | .87** | .74** | .79** | .43* | .13 | .57** |

| Internalizing Problems | .41* | .61** | .43* | .52** | .65** | .36 |

| Externalizing Problems | .76** | .57** | .74** | .45* | .22 | .50** |

| Total Problems | .62** | .69** | .74** | .52** | .56** | .58** |

| DSM-Oriented | ||||||

| Affective Problems | .34 | .44* | .39* | .67** | .49* | .36 |

| Anxiety Problems | .63** | .73** | .62** | .44* | .42* | .50** |

| Somatic Problems | .64** | .63** | .57** | .51** | .19 | .24 |

| ADH Problems | .72** | .57** | .84** | .24 | .12 | .48** |

| Oppositional Defiant Problems | .84** | .68** | .70** | .32 | .05 | .54** |

| Conduct Problems | .72** | .68** | .71** | .42* | .28 | .55** |

p < .05,

p < .01

Note: Bold and underlined reflect relationships hypothesized to establish convergent validity.

Gender and Age Comparisons

No statistically significant differences were found for gender on any of the CBCL subscale or DSM-Oriented subscale raw or standard scores (see Table 5). Similarly, no statistically significant correlations were found for age on any of the CBCL subscale or DSM-Oriented subscale raw or standard scores. The CBCL raw and normative data do not appear to demonstrate any gender or age variation among children with DS.

Table 5.

Gender difference on CBCL subscales and DSM-oriented subscales and correlation of subscales with age.

| Males | Females | Correlation with age | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxious/Depressed | 88 | 53.5 (4.8) | 53.4 (6.6) | .02 |

| Withdrawn/Depressed | 88 | 58.9 (8.5) | 57.6 (7.7) | .10 |

| Somatic Complaints | 88 | 56.7 (5.8) | 56.4 (6.8) | .16 |

| Social Problems | 87 | 59.9 (6.3) | 61.6 (6.9) | .04 |

| Thought Problems | 87 | 64.6 (8.7) | 61.6 (8.3) | .06 |

| Attention Problems | 88 | 62.3 (8.3) | 64.2 (7.7) | −.13 |

| Rule-Breaking Behavior | 87 | 56.4 (6.3) | 56.6 (6.0) | −.18 |

| Aggressive Behavior | 88 | 59.5 (8.6) | 58.1 (8.4) | −.17 |

| Internalizing Problems | 84 | 54.0 (9.8) | 52.0 (10.8) | .16 |

| Externalizing Problems | 84 | 56.3 (10.7) | 56.0 (9.9) | −.15 |

| Total Problems | 60 | 59.7 (9.5) | 59.2 (8.7) | .04 |

| DSM-Oriented | ||||

| Affective Problems | 69 | 60.3 (7.7) | 57.2 (7.2) | .06 |

| Anxiety Problems | 69 | 57.3 (7.2) | 56.7 (8.3) | .04 |

| Somatic Problems | 68 | 56.3 (5.7) | 56.2 (8.9) | .09 |

| ADH Problems | 69 | 59.6 (8.0) | 59.6 (8.0) | .02 |

| Oppositional Defiant Problems | 69 | 59.8 (8.2) | 58.2 (7.8) | .04 |

| Conduct Problems | 69 | 57.4 (7.8) | 57.0 (6.7) | −.14 |

Discussion

The assessment of maladaptive behaviour in children with DS generally uses measures that have not been examined for their psychometric properties when used specifically with this population. There is a need to understand the reliability and validity of measures of behaviour specific to children with DS (Esbensen et al., 2017). We evaluated the CBCL among children with DS to understand its psychometric properties and support selection of appropriate measures for children with DS. After conversion based on CBCL age and gender norms, no significant differences were found on any subscale, justifying use of the standard CBCL scoring with children with DS. However, the CBCL demonstrated variable reliability and validity across different subscales.

The overall subscale scores of Internalizing and Externalizing Problems, as well as the Total Problems all demonstrated sound internal consistency and inter-rater reliability, consistent with findings from the normative data (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). These subscales demonstrated more variability in construct validity, demonstrating good convergent validity with subscales on the ABC and NCBRF, yet questionable discriminant validity. Overall, this pattern of findings suggests that the Internalizing, Externalizing and Total Problems subscales of the CBCL are psychometrically sound for use with children with DS.

In contrast, the individual subscales that comprise Internalizing Problems (Anxious/Depressed and Somatic Complaints) demonstrated poor to acceptable internal consistency and non-statistically significant inter-rater reliability. Similarly, internal consistency was poor to acceptable and inter-rater reliability was poor for the DSM-Oriented subscales of Affective Problems, Anxiety Problems and Somatic Problems. This pattern of findings relating to inter-rater reliability likely reflects a combination of the challenges in using informant-reports to assess for internalizing problems, as well as children exhibiting a different pattern of behaviours across settings (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987). However, it is concerning that these subscales tended to demonstrate poor internal consistency. The exception is the Withdrawn/Depressed subscale which demonstrated acceptable internal consistency and inter-rater reliability. Further, the internalizing subscales of Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed and Somatic Complaints generally demonstrated good convergent validity but poor discriminant validity in comparison to the ABC and NCBRF. The DSM-Oriented subscales of Affective and Anxiety Problems demonstrated poor discriminant validity with the NCBRF, but good convergent and discriminant validity with the ABC. These challenges may reflect the small sample size, or reflect a different presentation of behaviours associated with internalizing symptoms. Thus, caution is warranted when using the CBCL internalizing subscales of Anxious/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Affective Problems, Anxiety Problems and Somatic Problems with children with DS. Future research is encouraged to use the Withdrawn/Depressed Problems subscale.

The individual subscales that comprise Externalizing Problems (Rule-Breaking Behavior and Aggressive Behavior) demonstrated poor or excellent internal consistency and statistically significant inter-rater reliability. The DSM-Oriented subscales of Oppositional Defiant Problems and Conduct Problems all demonstrated stronger internal consistency and inter-rater reliability. Thus, when examining externalizing problems, these DSM-Oriented subscales demonstrate stronger reliability estimates than the standard individual subscales. The aforementioned externalizing subscales demonstrated good convergent validity with the ABC and NCBRF, but questionable discriminant validity. Thus, these subscales are likely appropriate for use with children with DS, although caution is warranted for interpreting the function of externalizing behaviours.

The remaining stand-alone subscales, of Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, and the DSM-Oriented subscale of Attention-Deficit Hyperactive Problems generally demonstrate acceptable to good internal consistency, statistically significant inter-rater reliability, and good convergent and discriminant validity. It is worth noting that Thought Problems correlates with the Insecure/Anxious subscale of the NCBRF, drawing into question the validity of this specific subscale.

The normative data conversions eliminate gender and age differences, providing a preliminary suggestion of appropriate score conversion for children with DS. The feature is a benefit for using the CBCL with children with DS as it provides threshold scores for evaluating the clinical significance of scores. Together with the findings from the internalizing and externalizing subscales, these findings demonstrate that the CBCL partially meets the needs of NIH DS working group for being a psychometrically sound measure of behaviour in children with DS.

Despite the promising psychometric properties of the CBCL for use with children with DS, other areas of caution are noted. The discriminant validity of the CBCL was generally poor in comparison to the ABC and NCBRF. This finding may reflect a small pilot sample size, or shared variance due to parent reports and assessing the construct of behaviour. However, it may be that the subscales on the CBCL are not differentiating areas of concern common in children with DS. For example, children with anxious symptoms may present with more externalizing problems like compulsive behaviours (Evans & Gray, 2000). Further research would benefit from exploring the utility of the CBCL, ABC and NCBRF specifically for use with larger samples of children with DS, in comparison to direct observation of behaviour.

An additional area of caution is whether the CBCL is capturing key symptoms observed in children with DS. Common behaviours include wandering, self-talk, noncompliance, difficulties with social boundaries, and a need for sameness (McGuire & Chicoine, 2006; Patel et al., in press; Stein, 2016). Wandering can stem from challenges with inhibitory control, and also serve an attention-seeking function, yet is not captured on the CBCL by items such as “runs away from home.” Further, items such as disobedience and “impulsive acts” likely are not sensitive to detecting treatment changes in wandering. Individuals with DS frequently engage in self-talk. Similar to among the general population, self-talk can be functional, and a method of coping (Glenn & Cunningham, 2000), and can serve as an indicator of stress in an individual with DS. However, items from the CBCL such as “talks too much” and “hears things that others do not hear” do not capture the functional or stressful indicators of self-talk. Individuals with DS may appear noncompliant or disobedient as they may not understand instruction, they may have a skill deficit, or they may be tired from too many demands or quick transitions. Noncompliant behaviours can present differently, including verbal refusal, aggressive behaviour, sitting on the floor, or engaging in social overtures to avoid task demands (Wishart, 1993). While some items on the CBCL may capture aspects of this behaviour (“disobedient at home,” “disobedient at school”), these items are not likely to be sensitive to treatment effects, or to capturing treatment effects in different presentations. Similarly, these noncompliant behaviours are not the same as “breaks rules” as noncompliance may not have that kind of intent. Challenges with social boundaries are likely captured by “not liked by other kids” and “showing off or clowning” on the CBCL, but may not be sensitive to detecting treatment effects over time as changing others’ perspectives are slower to change.

Caution is also warranted for understanding the factor structure of the CBCL in children with DS. Individuals with DS often demonstrate a strong need for sameness, which may present itself as challenges with transitions or repetitive questioning about schedules (McGuire & Chicoine, 2006; Patel et al., in press; Stein, 2016). Some items on the CBCL may capture this characteristic, including “can’t get his/her mind off certain thoughts,” and “repeats certain acts over and over”. These symptoms fall on the Thought Problems subscale. However, among children with DS observed in clinic these behaviours are often more related to an anxious component. Thus, the CBCL factor structure may be questionable when applied to children with DS.

Other items on the CBCL may be targeting different symptoms in TD children than in children with DS. For example, “stealing” may not reflect a conduct behaviour in children with DS, but may reflect poor impulse control or comprehension challenges related to their cognitive deficit. While the CBCL is intended as a tool where clinical judgement is required, there is a need for clinicians to interview parents to better understand certain behaviours. This concern draws attention to the need for the development of a new measure of behaviours in children with DS with items that better reflect an underlying construct.

Endorsement of some items may reflect medical or developmental concerns in individuals with DS, rather than maladaptive behaviour. The overlap between medical symptoms and behaviour is also seen in TD children with complex medical conditions and emphasises the need for obtaining comprehensive information about a patient using multiple modalities before rendering diagnostic conclusions. It is important to balance the need for parsimony of scale length with the potentially significant implications of an endorsed critical item. These items are not expected to be endorsed frequently in the TD population, and were not endorsed frequently in the current study. However, they are still important to include because elevations at the item level may require immediate intervention (i.e., “sometimes talks about killing self”) or provide significant contribution to a differential diagnosis (i.e., “often sets fires,” “hurts animals”). We would not recommend excluding these items in the clinical setting.

There are several limitations of the current study that are worth noting. As ratings on the CBCL were collected across clinic and research studies with different study purposes, test-retest was not evaluated. Similarly, construct (convergent and discriminant) validity was assessed on only a small subset of the sample, and sensitivity to detecting change over time was not assessed. Despite these limitations, there are numerous strengths to the current study. Our study is the first psychometric evaluation of the CBCL in children with DS. Including both a clinical and a community sample ensured variability in presenting behavioural concerns and ensures for a more representative sample of children with DS. Demonstrating evidence of strong psychometric properties for some subscales of the CBCL validates its use in current studies of children with DS, particularly the Internalizing, Externalizing and Total Problem scores. Thus, our findings have implications for clinical trials targeting to improve behavioural outcomes as measured by these omnibus subscales for children with DS.

This study contributes to our understanding of measurement of behaviours in children with DS, which has important implications for accurately assessing symptoms and evaluating outcomes in children with DS (Esbensen et al., 2017; NICHD, 2015). Our preliminary findings indicate that some subscales of the CBCL perform in a psychometrically sound and theoretically appropriate manner in relation to other measures of behavioural problems. The individual internalizing subscales and DSM-Oriented subscales on the CBCL warrant caution when used with informant-reports and for discriminating from other constructs. The individual externalizing subscales and DSM-Oriented subscales demonstrate strong psychometric properties, but again some caution is warranted for discriminating from other constructs and understanding the function of the behaviour. The current findings suggest a similar interpretation for using Social Problems and Thought Problems subscale, as reliability is adequate but discriminant validity is variable. Attention Problems and Attention-Deficit Hyperactive Problems demonstrate strong psychometric properties, likely associated with the prevalence of these symptoms among children with DS. Subscales on the CBCL with sound psychometrics are recommended for clinical diagnostics of children with DS, although their utility for detecting change has not yet been evaluated in this population. Despite these promising finding using the CBCL with children with DS, future research is also needed to develop measures that better capture behaviours commonly observed in children with DS that are not captured on current rating scales.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was prepared with support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (R21 HD082307, A. Esbensen, PI), the Jack H Rubinstein Foundation (Esbensen), the Foundation Jérôme Lejeune (Esbensen), the Emily Ann Hayes Research Fund (Esbensen), and the Schmidlapp Young Women Scholar Award (Chen). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research would not have been possible without the contributions of the participating families and the community support from the Down Syndrome Association of Greater Cincinnati.

References

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological bulletin. 1987;101(2):213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla L. ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Aseba; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, Singh NN, Stewart AW, Field CJ. The Aberrant Behavior Checklist: A behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1985a;89:485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, Singh NN, Stewart AW, Field CJ. Psychometric characteristics of the aberrant behavior checklist. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1985b;89:492–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG, Tassé MJ, Rojahn J, Hammer D. The Nisonger CBRF: A child behavior rating form for children with developmental disabilities. Research in developmental disabilities. 1996;17(1):41–57. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(95)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone G, Goyal P, Ares W, Lannigan E. Neurobehavioral disorders in children, adolescents, and young adults with Down syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics. 2006;142(3):158–172. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe DA, Matson JL, Russell DW, Slifer KJ, Capone GT, Baglio C, Stallings S. Behavior problems of children with Down syndrome and life events. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1999;29(2):149–156. doi: 10.1023/a:1023044711293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish K, Steele A, Monteiro CRC, Karmiloff-Smith A, Scerif G. Attention deficits predict phenotypic outcomes in syndrome-specific and domain-specific ways. Frontiers in psychology. 2012;3:227. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuskelly M, Dadds M. Behavioural problems in children with Down’s syndrome and their siblings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1992;33:749–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daunhauer LA, Fidler DJ, Will E. School function in students with Down syndrome. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014;68(2):167–176. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2014.009274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens E, Kasari C. Maladaptive behavior in children with Prader-Willi syndrome, Down syndrome, and nonspecific mental retardation. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1997;102(3):228–237. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(1997)102<0228:MBICWP>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens E, Shah B, Davis B, Baker C, Fife T, Fitzpatrick J. Psychiatric disorders in adolescents and young adults with Down syndrome and other intellectual disabilities. Journal of neurodevelopmental disorders. 2015;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s11689-015-9101-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens E, Shah B, Sagun J, Beck T, King B. Maladaptive behaviour in children and adolescents with Down’s syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2002;46:484–492. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2002.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einfeld SL, Tonge BJ. The Developmental Behavior Checklist: The development and validation of an instrument to assess behavioral and emotional disturbance in children and adolescents with mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1995;25(2):81–104. doi: 10.1007/BF02178498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esbensen AJ, Hooper SR, Fidler D, Hartley SL, Edgin J, d’Ardhuy XL, … Urv T. Outcome measures for clinical trials in Down syndrome. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities. 2017;122(3):247–281. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-122.3.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DW, Canavera K, Kleinpeter FL, Maccubbin E, Taga K. The fears, phobias and anxieties of children with autism spectrum disorders and down syndrome: Comparisons with developmentally and chronologically age matched children. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2005;36(1):3–26. doi: 10.1007/s10578-004-3619-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DW, Gray FL. Compulsive-like behavior in individuals with Down syndrome: its relation to mental age level, adaptive and maladaptive behavior. Child development. 2000;71(2):288–300. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeley K, Jones E. Strategies to address challenging behaviour in young children with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice. 2008;12(2):153–163. doi: 10.3104/case-studies.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler D, Hodapp R, Dykens E. Stress in families of young children with Down syndrome, Williams syndrome, and Smith-Magenis syndrome. Early Education and Development. 2000;11(4):395–406. [Google Scholar]

- Foley KR, Bourke J, Einfeld SL, Tonge BJ, Jacoby P, Leonard H. Patterns of depressive symptoms and social relating behaviors differ over time from other behavioral domains for young people with Down syndrome. Medicine. 2015;94(19):e710. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gath A, Gumley D. Behaviour problems in retarded children with special reference to Down’s syndrome. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;149(2):156–161. doi: 10.1192/bjp.149.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn SM, Cunningham C. Typical or pathological? Routinized and compulsive-like behaviors in children and young people with Down syndrome. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2007;45(4):246–256. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556(2007)45[246:TOPRAC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn SM, Cunningham CC. Parents’ reports of young people with Down syndrome talking out loud to themselves. Mental Retardation. 2000;38(6):498–505. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2000)038<0498:PROYPW>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacola LM, Hickey F, Howe SR, Esbensen A, Shear PK. Behavior and adaptive functioning in adolescents with Down syndrome: Specifying targets for intervention. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2014;7(4):287–305. doi: 10.1080/19315864.2014.920941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of chiropractic medicine. 2016;15(2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveland KA, Kelley ML. Development of adaptive behavior in preschoolers with autism or Down syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1991;96(1):13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Määttä T, Tervo-Määttä T, Taanila A, Kaski M, Iivanainen M. Mental health, behavior, and intellectual abilities of people with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice. 11(1):37–43. doi: 10.3104/reports.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire D, Chicoine B. Mental Wellness in Adults with Down Syndrome. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nicham R, Weitzdorfer R, Hauser E, Freidl M, Schubert M, Wurst E, … Seidl R. Spectrum of cognitive, behavioural and emotional problems in children and young adults with Down syndrome. Journal of Neural Transmission Supplement. 2003;67:173–191. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6721-2_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD. Outcome measures for clinical trials in individuals with Down syndrome. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/meetings/2015/Documents/DS_outcomes_meeting_summary.pdf.

- Owen DM, Hastings RP, Noone SJ, Chinn J, Harman K, Roberts J, Taylor K. Life events as correlates of problem behavior and mental health in a residential population of adults with developmental disabilities. Research in developmental disabilities. 2004;25(4):309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel L, Wolter-Warmerdam K, Leifer N, Hickey F. Behavioral characteristics of individuals with Down syndrome. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Pitcairn TK, Wishart JG. Reactions of young children with Down’s syndrome to an impossible task. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1994;12(4):485–489. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-835X.1994.tb00649.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pueschel SM, Bernier J, Pezzullo J. Behavioural observations in children with Down’s syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 1991;35(6):502–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1991.tb00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. BASC3: Behavior Assessment System for Children. PscyhCorp; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roach MA, Osmond GI, Barratt MS. Mothers and fathers of children with Down syndrome: parental stress and involvement in childcare. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1999;104:422–436. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(1999)104<0422:MAFOCW>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojahn J, Matson JL, Lott D, Esbensen AJ, Smalls Y. The Behavior Problems Inventory: An instrument for the assessment of self-injury, stereotyped behavior, and aggression/destruction in individuals with developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2001;31(6):577–588. doi: 10.1023/a:1013299028321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders JL, Morgan SB. Family stress and adjustment as perceived by parents of children with autism or Down syndrome: implications for intervention. Child and Family Behavior Therapy. 1997;19:15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Stein D. Supporting Positive Behavior in Children and Teens with Down Syndrome. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- van Gameren-Oosterom HB, Fekkes M, Buitendijk SE, Mohangoo AD, Bruil J, Van Wouwe JP. Development, problem behavior, and quality of life in a population based sample of eight-year-old children with Down syndrome. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gameren-Oosterom HB, Fekkes M, Van Wouwe JP, Detmar SB, Oudesluys-Murphy AM, Verkerk PH. Problem behavior of individuals with Down syndrome in a nationwide cohort assessed in late adolescence. Journal of Pediatrics. 2013;163(5):1396–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visootsak J, Sherman S. Neuropsychiatric and behavioral aspects of trisomy 21. Current psychiatry reports. 2007;9(2):135–140. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart J. Learning the hard way: Avoidance strategies in young children with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice. 1993;1(2):47–55. [Google Scholar]