Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

Vaginal penetration phobia is a common and distressing problem worldwide. It interferes with vaginal penetrative sexual relations, and leads to unconsummated marriage (UCM). This problem may be heightened in Arab women, due to cultural taboos about pain and bleeding, that may be associated with the first coital experience after marriage. Data about this problem is scarce in Arab societies. The aim of this study was to evaluate the response of these women and their husbands to an individualized, psychotherapeutic assessment and treatment to resolve this problem.

DESIGN AND SETTINGS

Retrospective descriptive in a general gynecology community setting over a 6-year period.

METHODS

The study involved a retrospective sequential cohort of 100 Arab couples with UCM due to the woman’s VPP. They were evaluated by a female gynecologist in out patient clinics. Data was collected through chart review, and telephone interviews. Final analysis was performed on 100 Arab couples, who satisfied the inclusion criteria. They were followed up to assess their response to an individualized, structured treatment protocol. The treatment combined sex education with systematic desensitization, targeting fear and anxiety associated with vaginal penetration.

RESULTS

A total of 96% of the studied group had a successful outcome after an average of 4 sessions. Penetrative intercourse was reported by the tolerance of these women; further pregnancy was achieved in 77.8 % of the infertile couples.

CONCLUSION

Insufficient knowledge of sexual intercourse is a major contributor to the development of VPP in the sampled population. It appears that they respond well to an individualized, structured treatment protocol as described by Hawten 1985 (regardless of other risk factors associated with vaginismus).

Primary or lifelong vaginismus, is now known as vaginal penetration difficulty, coital or non-coital, despite a woman’s wish to have sexual intercourse.1 It creates personal and interpersonal stress in sexual relations and may lead to infertility2 or penultimate divorce. Historically, the challenge of Vaginismus has been penned in the 18th century literature3 highighting the plight of women who suffer from this condition. It remains a prevalent condition affecting 25% of women as per UK statistics and 68% in Ghana.4,5 The contrast of these figures represents a large disparity between the existence of vaginal penetration phobia (VPP) in dissimilar cultures.

Women with this condition, avoid any type of penetration, whether sexual or not, due to their fear of pain, whether anticipated or imagined, resulting in reflex involuntary vaginal muscle contraction. In severe cases, patients can have a panic disorder, with variable adductor muscle contraction in the thighs, abdomen, and pelvic floor, making vaginal penetration impossible. This disorder could be considered a specific phobia with severe anxiety or panic, provoked by exposure to a specific feared object or situation. When this fear is sexual, it becomes a fear of vaginal penetration6,7 and is termed VPP. In Arab countries and neighboring Muslim countries, where cultural norms are similar, VPP is the most common female sexual disorder, accounting for unconsummated marriage (UCM).8–11 Therefore, in these populations, the diagnosis of vaginismus due to VPP is based on a couple’s sexual history within their marriage, but specifically analyzes the wife’s response to sexual intercourse. Common reactions to sexual intercourse (on the wife’s part) will frequently be met by deep fear and severe anxiety, which produces variable degrees of involuntary adductor muscle contractions to various sexual intercourse attempts. This results in the avoidance of any coital vaginal penetrative attempts, even if she initially pleasured by the intimacy and sexual foreplay. van der Velde12 summarized this frequent VPP scenario by stating, “It is important to note that it was not the sexual situation that evoked the reaction, but rather the threatening aspect of it, penile vaginal penetration, which supported the hypothesis that vaginistic reactions are part of a general defense against a threatening situation.”

A variety of interventions have been suggested in case study reports. Effective treatments to vaginismus include sex education, psychosexual therapy, systematic desensitization, anxiolytics, and botulin toxin. While there are a few controlled studies on the management of vaginismus, they are limited and poorly designed. Presently, most of the recommendations are based on evidence from descriptive case-control studies, case studies, clinical experience, and expert opinion.13–15

The distress associated with vaginismus is heightened in Saudi Arabia due to cultural taboos regarding sex education and social pressure for couples to engage in penetrative sexual relations soon after marriage, with the added pressure to conceive early. Most of the couples obtain sexual information from unofficial sources and recounts from their peers, which can often be exaggerated and thus deeply unconstructive to this condition. It is reported that vaginismus is the most common cause of UCM in the Saudi Arabian community, being the primary cause in 63.9% to 77% in some studies.8,9 Recognized abnormal perceptions for the development of vaginismus included: (1) Violent penile-vaginal penetration causing rupture, damage, pain, or bleeding, particularly as the vagina was too small, narrow, or tight to accommodate the erect penis (psychosexual fantasies). (2) Negative attitude toward sex (i.e., filthy or shameful). (3) Disgust for the penis, testis, or semen.16

A multidisciplinary approach is that “a gynecologist, physical therapist, and psychologist/sex therapist, should be involved in the assessment and treatment of vaginismus to address its different dimensions.”17 Fear of genital pain should also be addressed with an explanation of pelvic floor muscle tension and sexual pleasure.17 In Arab societies, referral to clinics with multidisciplinary teams, specializing in psychosexual therapy, may not be accessible to the general public, as sexual concerns are considered a sensitive subject. Therefore, gynecologists are often the initial contact for women with vaginismus and VPP.

It was against this background that our study was undertaken on Arab Muslim women and their husbands, where they received a structured, managed approach to improve their VPP and sexual relations within their marriage. It is hoped that the results of this study will add to preexisting knowledge of the clinical characteristics of women with VPP in Saudi marriages. Furthermore, these results may allow comparisons with findings in other societies as well as giving insight into some simplified behavioral techniques used to reduce the severity of VPP in this population.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective study, which took place in 2 gynecology clinics in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institution Research Board (IRB). Charts of patients seen with VPP, treated and followed over a 6-year period (2007–2012), were obtained manually. Patients were then contacted to provide verbal consent as per the recommendations of the IRB. This process produced further information from couples with regard to their progress and clinical outcome. Couples presented with an inability to have coital vaginal penetration as a result of the woman’s persistent, recurrent fear and avoidance at the initiation of penetrative intercourse. The criteria for diagnosing VPP is based on the behavioral description developed by an international multidisciplinary committee. It defines VPP as “persistent difficulties to allow vaginal entry of a penis, finger, and/or any object, despite the woman’s expressed wish to do so.” This also collaborates with fear and avoidance behavior. Structural or physical reasons should be ruled out.1

A total of 100 couples who met the inclusion criteria for this study were categorized as follows: (A) married for at least 1 month and sexually active (enjoying intimate sexual relations provided penetration is not attempted or anticipated) with at least 2 failed trials of vaginal penetrative intercourse, and avoidance by the wife at the time of initial consultation. (B) Healthy, with no major mental or medical disorders, and seeking therapy to improve and resolve coital penetration fears. (C) Time lapse of at least 1 month since the completion of treatment program offered, and instruction to try penetrative intercourse. (D) Contactable either by email or telephone. (E) Agreed to participate in this study by verbal consent.

Most patients were self-referrals (90%). The remaining patients (10%) were referred from psychiatrists or other gynecologists in community clinics and hospitals. All had good general school education, with 98% of wives and 97% of husbands having received high school education or above. All husbands and 43% of wives were in employment (Table 1). Couples reported variable degrees of typical phobic avoidance muscle contraction that is, vaginistic reaction.18 This is defined “as the closure of the perineum and thighs with elevation of buttocks and withdrawal of their bodies at the trial of penile vaginal penetration attempt.” Also reported by couples was a history of a single attempt at vaginal penetration, which was preceded by anxiety and avoidance acts with severe dyspareunia, leading to apareunia with any further attempt at vaginal penetration. Fear of pain and bleeding, or damage to their genitalia (VPP), was the primary concern cited by these women for their avoidance behavior. It is noteworthy that despite the penetrative fears reported by these women, they maintained enjoyment of all other aspects of sexual intimacy and reported orgasms. This description was assumed to be related to faulty sexual knowledge obtained by these women through unofficial sources such as stories made by their peers regarding their exaggerated first coital experience and defloration. Although there are many potential risk factors reported by couples for the development of VPP, the most frequently reported in this study was insufficient knowledge about sex (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Parameter | Min. | Max. | Mean | SD | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Wife’s age (y) | 18 | 35 | 25 | 4 | 24–26 |

| Husband’s age (y) | 22 | 42 | 30 | 4 | 29–31 |

| Duration of marriage (y) | <1 | 15 | 2 | 2 | 2–3 |

| Education | Wife | Husband |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Intermediate school | 2% (n= 2) | 3% (n=3) |

| High school and above | 98% (n=96) | 97% (n=97) |

Table 2.

Reported potential risk factors for development of vaginal penetration phobia.

| Factor | Percentage 95% | Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Insufficient education | 97 | (94, 99) |

| Childhood sexual abuse | 21 | (13, 29) |

| Traumatic sexual encounter | 31 | (22, 40) |

Data collection forms were designed by the treating female gynecologist. It contained couples’ age, parity, relationship status, general health, demographics, prior significant medical or surgical history, background health, and general Information. Diagnostic criteria included a detailed medical, psychosocial, relationship and sexual history with any episodes of traumatic sexual experience at childhood, before marriage, or after marriage with present or prior husbands, history of abuse (physical or sexual), and comorbid behavioral or psychiatric conditions. Various prior consultations, interventions, and their effectiveness in resolving the condition were taken in detail. The treatment described by Hawten in 198519 was adopted using a combination of sex education, counseling, sensate focus training with Kegel exercises, and graded insertion of fingers or vaginal trainers, with free usage of local anesthesia and lubricants with vaginal containment. Psychosexual behavioral therapy involved a few sessions over different days. They were seen on a daily basis for at least 45 minutes. Anxiolysis was accomplished by teaching breathing exercises, educational gynecological examination using a mirror, patience, and empathy. However, when this failed to achieve the necessary relaxation and compliance to examine and insert vaginal trainers, SSRI therapy like escitalopram was started for severe recurrent (>2 trials in 2 different sessions) phobic and avoidance reactions to vaginal trainer insertions. They were instructed to use escitalopram for 3 weeks, before resumption of vaginal training.

All women were given the same specific instructions on the 6 stages of the sensate focus technique (Table 2), translated into Arabic. Progression through the 6 stages required comfort with the preceding stage.

An important aspect of the treatment was the use of vaginal trainers. These were used by the patient. They were either assisted or supervised by the gynecologist and their husband if he was present and willing. Vaginal training exercises began with the patient’s fingers and progressed using increasingly larger cylindrical objects that were widely available and ended with a vaginal ultrasound probe and a medium size vaginal speculum. The standardized gynecological examination was performed when the patients allowed it. It consisted of visual examination of the vulva, a wet cotton swab test (wet cotton swab touching the vaginal vestibule in all quadrants), and digital vaginal examination to examine the vulvar vestibule for any evidence of inflammation, tenderness, or structural abnormality in the external genitalia.

Surgery was reserved for correcting structural deformities. This was performed only when vaginal training with progressive dilators, (including digital corrective trials to allow larger vaginal dilator) or penile vaginal penetration fails to allow comfortable penetration. When recurrent erectile dysfunction was presented from the husband after a trial of vaginal intercourse (provided the wife has no more avoidance reactions), then referral to a urologist and examination for medical causes (e.g., diabetes) or psychological causes (e.g., anxiety) was recommended.

Couples were contacted at least 1 month after completing the treatment program, and were asked directly, if they had successful painless, comfortable, penile-vaginal penetrative intercourse. They were also asked if they were continuing to make progress sexually to determine that the progress was consistent and not sporadic.

The data was analyzed using SPSS, version 20.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Using the normal approximation, 95% confidence intervals were constructed. The Chi-square test was used for dichotomous outcomes, either association or lack of it, between the potential risk factors and the success rates. A P value less than the overall type I error rate of 5% was considered significant, and a t test was used for continuous outcomes.

RESULTS

The final analysis was performed on 100 couples as per the inclusion criteria. The couples were young Arabs; 90% of these patients were Saudi, with 10% being non-Saudi nationals, coming for treatment from other neighboring Arab countries (Table 1). For 95 women, it was their first marriage, that is, the first encounter with sexual relations, with an average of 2 years post-marriage, ranging less than 1 year to 15 years. For 5 patients, it was their second marriage, as they were divorced because of VPP. None of the husbands had a history of erectile dysfunction in the initial stages of the marriage, but all women unanimously reported an inability to have penetrative sexual relations. Out of 100 women, 7 had prior pregnancies; 2 of those pregnancies were spontaneous and 5 were achieved with the help of assisted reproduction therapy, which was reported to have been done under conscious sedation. The reported pregnancies were from the present marriages. Primary infertility was reported in 51 couples, who were married for 1 year or more and withholding birth control methods.

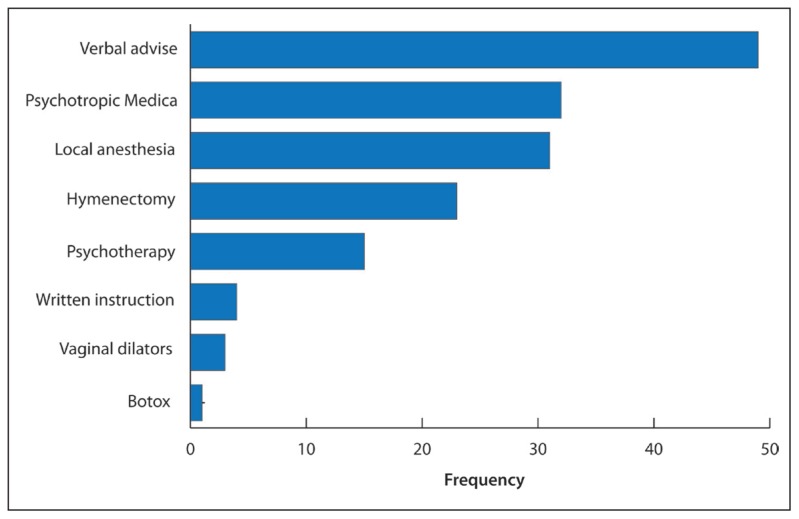

A total of 77 couples tried medical help after failure of the husband’s personal efforts to resolve their wives insecurities and fear of intercourse. A total of 303 consultations were reported overall. The majority of consultation was to gynecologists (77.4%), 16.1% to mental health specialist (psychologist or psychiatrists), and 6.2 % to faith healer. There were many reported treatments offered by prior health care providers, which were unsuccessful. It came in the form of verbal advice, which was general and non-specific, giving verbal reassurance and advising patients to relax (Figure 1). Although there are many potential risk factors reported by the couples for the development of VPP, the most frequently cited reason in this study was insufficient sexual knowledge (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Previous interventions performed for subjects.

Psychosexual behavioral therapy involved a few sessions with a mean of 3.44 (1.493) sessions. The first session lasted approximately 1 hour, which provided teaching and explanation, and allowed couples to air their queries. Further sessions lasted between 15 and 60 minutes.

There was a negative cotton tip exam in all patients excluding those having zulvo vestibuodynia syndrome dyspareunia15 or other sexual pain disorders that were found by physical examination. Only 9 patients needed surgical intervention to correct structural deformities, (6 to dilate a rigid hymenal ring, 2 to cut a longitudinal hymenal septum, and 1 to divide labial fusion secondary to prior female genital mutilation, type 3). Escitalopram was needed in 8 women for severe recurrent (>2 trials in 2 different sessions) fear and avoidance reactions to vaginal trainer insertions.

The success rate of the treatment was measured by the couple reporting total elimination of fear from vaginal penetration by coital and non-coital attempts—reported in 96 couples. Our study established that within 2 to 3 sessions, most couples had a successful intercourse outcome (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of sessions in comparison to success or failure.

| 2 to 3 | 4 to 5 | More than 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Success | 57 (98.3%) | 32 (91.4) | 7 (100%) |

| Failure | 1 (1.7%) | 3 (8.6%) | 0 (0%) |

Number of sessions: Mean=3.44 (1.493); Range=8 (2–10); Mode=2

The majority of patients, who were married for more than 1 year, needed less than 1 week of treatment to be cured irrespective of the duration of their marriage.

Successful fear-free sexual penetrative relations were reported in all further attempts after completing the treatment program in 87 patients (87% complete success), with 9 patients (9%) achieving partial success. Success was also reported as complete in 10 (83%) out of the 12 women who reported a history of childhood sexual abuse.

This success was maintained since the completion of treatment, for an average of 2.19 years (1 month–5 years). Of the 4 patients who reported an inability to have any penetrative sexual encounter (despite reporting an improvement in their fears of vaginal penetration 4% failure), 2 were already separated from their husbands due to other marital difficulties. The other 2 patients remained married and continued the pursuit of additional interventions. Pregnancy was reported in 35 out of 51 women who complained of primary infertility, accounting for 77.8% of them; 98.5% of the patients who got pregnant had successful VPP treatment.

DISCUSSION

This study has attempted to establish some of the clinical characteristics and management of 100 Arab couples with UCM due to the woman’s primary vaginismus caused by VPP. In the Muslim Arab societies as demonstrated in this study and several other reports from the neighboring Middle East and North Africa (Mena) regions,20–23 vaginismic women constitute the largest group contributing to UCM. Cultural factors play a major role in the occurrence of this condition. The leading factors that contribute to primary vaginismus include fear of pain associated with sexual penetration. This is affirmed by the popular misconception of the “breaking” of the hymen upon the first attempt of penetration, and an awareness that it will be accompanied with pain. This thought process is evident in this population and is thus the main risk factor and contributor for the development of VPP in Saudi women.

Gynecologists are generally the first physicians to interact and evaluate a woman with VPP and infertility. Generally, they were regarded as the most constructive influences;24 however, frequent negative experiences were also reported in this study. Patients were often faced with inadequately trained medical practitioners offering an insufficient medical care, and doctor–patient interactions in this context were reported to be unhelpful. A gynecologist in the Arab Muslim society, therefore, faces pressure to treat these sexual disorders. However, because of cultural taboos, gynecologists in this society are rarely adequately trained to have the understanding, support, or compassion that is required to effectively treat female sexual dysfunction.25

Referral to a clinic specializing in mental health and sex therapy may not be an acceptable treatment either, as there are stigmas attached to both therapies. Ideally, a multidisciplinary approach to VPP management is recommended. Skills to manage this problem effectively are not easily accomplished by individual practitioners.17 To the best of our knowledge, clinics offering this type of team approach are few in the developing world.

Many couples attribute their UCM to supernatural influences (witchcraft, jinn possession, or evil eye), with most couples reporting a visit to a traditional healer at least once9 before coming into contact with a gynecologist. In this study, only 6.2% of the consultations were to faith healers, which is thought to be an underestimate, as the help-seeking practice from faith healers is a common cultural belief. It deserves further investigation, and public education, to avoid adding to the preexisting wealth of misconceptions that aggravate cases of UCM and delay help being sought from professional sources.

Following the steps of Reamy in the USA,26 gynecologists in developing countries such as Jindal in India and, more recently, Fageeh from Saudi Arabia have reported the successful treatment of VPP with the conventional therapy or Botox in cases of intractable conditions, respectively.2,27 Gynecologists are trained to diagnose physiologic and anatomic causes of dyspareunia and vaginismus, but there is a need to improve training at undergraduate and postgraduate levels to enable gynecologists and other health care providers in Arab countries to provide better sexual health care.

The interventions in this study offered a treatment approach that was acceptable, short, and successful in the majority of couples. It was assessed that 48 out of 96 couples who were married for more than 1 year needed less than 1 week of treatment sessions to be cured (meaning successful penetration of some sort, which was pain free and without fear) and to consummate their marriages regardless of the duration of marriage (P=.106). The therapy durations were quite short in this study, in line with reports by other gynecologists,2,22 which contrasted the Fageeh WM study that required a few months for a cure.27 Most of the patients were cured in 1 week; this is perhaps because patients attended daily treatment sessions as instructed. This study showed that daily treatment sessions were beneficial for success, producing fast more immediate responses. At this point, our results support the finding on Turkish couples28 but did not support the findings in Taiwan, suggesting that couples with a duration of unconsummated intercourse of up to 2 years have a better success rate than those with a longer duration.29 Perhaps this could be due to cultural differences between these countries.

The approach used in this study motivated women to progress in vaginal penetration training, in addition to involving the husband in the treatment plan, which helped reduce vaginal penetration fears. We did not assess the differences between the cases who used the trainers themselves and those helped by their partners. The crude measure of success rate was 96% and 87% complete success, which is in line with reported rates in Taiwan,29 where after therapy, 93.3% of vaginismic women were successfully treated and 83.3% had regular intercourse with orgasm. In the 9 women who were regarded as having partial success, there was clinical improvement in perceived control beliefs regarding penetration and a pronounced reduction in complaints of VPP, coital fear, and catastrophic pain beliefs regarding vaginal penetration. Support and patience were important aspects of treatment as were empathy and encouragement. These improvements are similar to reports from other Asian countries, with similar cultural beliefs.23,30,31 In those presenting with primary infertility, there was a high rate of pregnancy after completing therapy, presumably due to improved intravaginal deposition of sperms. This can be regarded as a positive secondary outcome of the VPP therapy.

Despite the high success rate with the aforementioned program, there was a 4% failure to achieve a successful intercourse outcome. This may be due to the fact that a few VPP patients may require more than the program offered, because they may have underlying and unresolved relationship problems, poor self-image, and an unrelenting fear of penile penetration, which might need a different approach.

The approach used in this study may be considered an appropriate way of treating VPP in clinical settings when couples agree to intervention. It seems cost-effective, but a control group is needed in future studies to prove effectiveness.

Some limitations of the study include that this analysis is a retrospective study, representing an experience from a single center. The main strength of our study is that we analyzed a large number of patients with vaginal penetration fears, which is the largest series from Saudi Arabia so far with a long follow-up. This study is an overview of different aspects of VPP from Saudi Arabia, with suggested interventions; further studies are needed to address various other aspects of this condition in this region.

In conclusion, VPP is a common psychosexual problem in Saudi Arabia. Patients with VPP are seen frequently by gynecologists, and it seems that insufficient sexual knowledge is the major potential risk factor to developing this condition. The psychosexual behavioral therapy consisted of sex education and counseling. This was followed by assisted vaginal penetration training, coupled with motivation exercises. Spousal support and involvement of the patient’s husband as part of the treatment plan helped reduce vaginal penetration fears significantly. The cases from the Arab region are similar to patients from other parts of the world in terms of clinical presentation, but the management needs to be altered. This should be kept in mind, when planning health care programs for these patients in the future. As the gynecologist is often the initial contact for VPP patients in the Arab society, training in sexual health should be provided for interested gynecologists who can treat these patients successfully themselves as demonstrated in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basson R, Leiblum S, Brotto L, Derogatis L, Fourcroy J, Fugl-Meyer K, et al. Revised definitions of women’s sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2004 Jul;1(1):40–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jindal UN, Jindal S. Use by gynecologists of a modified sensate focus technique to treat vaginismus causing infertility. Fertil Steril. 2010 Nov;94(6):2393–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MJS. On vaginismus Transcripts of the Obstetrical Society of London. 1861. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldmeier D, Keane FE, Carter P, Hessman A, Harris JR, Renton A. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in heterosexual patients attending a central London genitourinary medicine clinic. Int J STD AIDS. 1997 May;8(5):303–6. doi: 10.1258/0956462971920136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amidu N, Owiredu WK, Woode E, Addai-Mensah O, Quaye L, Alhassan A, et al. Incidence of sexual dysfunction: a prospective survey in Ghanaian females. RB&E. 2010;8:106. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reissing ED, Binik YM, Khalife S, Cohen D, Amsel R. Vaginal spasm, pain, and behavior: an empirical investigation of the diagnosis of vaginismus. Arch Sex Behav. 2004 Feb;33(1):5–17. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000007458.32852.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Lankveld JJ, ter Kuile MM, de Groot HE, Melles R, Nefs J, Zandbergen M. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for women with lifelong vaginismus: a randomized waiting-list controlled trial of efficacy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006 Feb;74(1):168–78. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Addar MH. The unconsummated marriage: causes and management. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2004;31(4):279–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MAAS Unconsummated Marriage. AJP. 2004;15:2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badran W, Moamen N, Fahmy I, El-Karaksy A, Abdel-Nasser TM, Ghanem H. Etiological factors of unconsummated marriage. Int J Impot Res. 2006 Sep-Oct;18(5):458–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zargooshi J. Unconsummated marriage: clarification of aetiology; treatment with intracorporeal injection. BJU Int. 2000 Jul;86(1):75–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Velde J, Laan E, Everaerd W. Vaginismus, a component of a general defensive reaction. an investigation of pelvic floor muscle activity during exposure to emotion-inducing film excerpts in women with and without vaginismus. Int urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(5):328–31. doi: 10.1007/s001920170035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crowley T, Goldmeier D, Hiller J. Diagnosing and managing vaginismus. BMJ. 2009;338:b2284. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowley T, Richardson D, Goldmeier D Bashh Special Interest Group for Sexual D. Recommendations for the management of vaginismus: BASHH Special Interest Group for Sexual Dysfunction. Int J STD AIDS. 2006 Jan;17(1):14–8. doi: 10.1258/095646206775220586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melnik T, Hawton K, McGuire H. Interventions for vaginismus. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;12:CD001760. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001760.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Sughayir MA. Vaginismus treatment. Hypnotherapy versus behavior therapy. Neurosciences. 2005 Apr;10(2):163–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lahaie MA, Boyer SC, Amsel R, Khalife S, Binik YM. Vaginismus: a review of the literature on the classification/diagnosis, etiology and treatment. Women Is Health. 2010 Sep;6(5):705–19. doi: 10.2217/whe.10.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leiblum SR. Vaginismus: A most perplexing problem. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.KH. Sex therapy: A practical guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farnam F, Janghorbani M, Merghati-Khoei E, Raisi F. Vaginismus and its correlates in an Iranian clinical sample. Int J Impot Res. 2014 May 15; doi: 10.1038/ijir.2014.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nabil Mhiri M, Smaoui W, Bouassida M, Chabchoub K, Masmoudi J, MH Unconsummated marriage in the Arab Islamic world: Tunisian experience. 2013:71–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherif GAS. Unconsummated Marriage: Relationship between Honeymoon Impotence and Vaginismus. Med J Cairo Univ. 2009;77(3) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasan A, Akdeniz N. Treatment of lifelong vaginismus in traditional Islamic couples: a prospective study. J Sex Med. 2009 Apr;6(4):1054–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reissing ED. Consultation and treatment history and causal attributions in an online sample of women with lifelong and acquired vaginismus. J Sex Med. 2012 Jan;9(1):251–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auwad WA, Hagi SK. Female sexual dysfunction: what Arab gynecologists think and know. Int Urogynecol J. 2012 Jul;23(7):919–27. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1701-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reamy K. The treatment of vaginismus by the gynecologist: an eclectic approach. Obstet Gynecol. 1982 Jan;59(1):58–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fageeh WM. Different treatment modalities for refractory vaginismus in western Saudi Arabia. J Sex Med. 2011 Jun;8(6):1735–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eserdag S, Zulfikaroglu E, Akarsu S, Micozkadioglu S. Treatment Outcome of 460 Women with Vaginismus. Eur J Surg Sci. 2011;2(3):73–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeng CJ, Wang LR, Chou CS, Shen J, Tzeng CR. Management and outcome of primary vaginismus. J Sex Marital Ther. 2006 Oct-Dec;32(5):379–87. doi: 10.1080/00926230600835189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munasinghe T, Goonaratna C, de Silva P. Couple characteristics and outcome of therapy in vaginismus. Ceylon Med J. 2004 Jun;49(2):54–7. doi: 10.4038/cmj.v49i2.3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gul V, Ruf GD. [Treating vaginismus in Turkish women]. Der Nervenarzt. 2009 Mar;80(3):288–94. doi: 10.1007/s00115-008-2554-7. Vaginismusbehand-lung bei turkischen Frauen. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]