Abstract

BACKGROUND

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a common inflammation of the nasal mucosa in response to allergen exposure. We translated and validated the Score for Allergic Rhinitis (SFAR) into an Arabic version so that the disease can be studied in an Arabic population.

OBJECTIVES

SFAR is a non-invasive self-administered tool that evaluates eight items related to AR. This study aimed to translate and culturally adapt the SFAR questionnaire into Arabic, and assess the validity, consistency, and reliability of the translated version in an Arabic-speaking population of patients with suspected AR.

STUDY DESIGN

Cross-sectional.

SETTING

Tertiary care hospital in Riyadh.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

The Arabic version of the SFAR was administered to patients with suspected AR and control participants.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURE

Comparison of the AR and control groups to determine the test-retest reliability and internal consistency of the instrument.

RESULTS

The AR (n=173) and control (n=75) groups had significantly different Arabic SFAR scores (P<.0001). The instrument provided satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.7). The test-retest reliability was excellent for the total Arabic SFAR score (r =0.836, P<.0001).

CONCLUSION

These findings demonstrate that the Arabic version of the SFAR is a valid tool that can be used to screen Arabic speakers with suspected AR.

LIMITATIONS

The absence of objective allergy testing

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is inflammation of the nasal mucosa in response to allergen exposure, which affects 5% to 40% of the world’s population.1 Although not fatal, the disease has significant effects on daily activities and quality of life.2,3 Only a few epidemiological studies have estimated the prevalence of AR in Saudi Arabia, but many studies have examined specific patients groups in other regions. For example, Nahhas et al examined 6- to 8-year-old children in Madinah city, and found that 24% of the 5188 children had AR symptoms although only 4% had been diagnosed with AR.4 Sobki and Zakzouk5 evaluated the prevalence of AR among children in Saudi Arabia and associations with hearing impairment and bronchial asthma. The study included 9540 children (44% male, 56% female), and 2529 patients (26.5%) had rhinitis, with 649 patients also having asthma (25.7% of the rhinitis group).5 Abdulrahman et al6 also performed the phone-based Allergies in Middle East Survey, which included 1639 individuals who were >4 years of age and resided in Egypt, Iran, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. The results revealed that the prevalence of physician-diagnosed AR was 10% in the Middle East, 11% in Egypt, 8% in Lebanon, and 9% in both Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.6 Within Saudi Arabia, reports on the prevalence of AR are conflicting, 4–12 which may reflect broad differences in the distribution of AR among the Saudi population. Regional variations across the country have been reported previously. 13,14 As the global prevalence of AR is increasing, a tool is needed to help study this disease in the Saudi population.

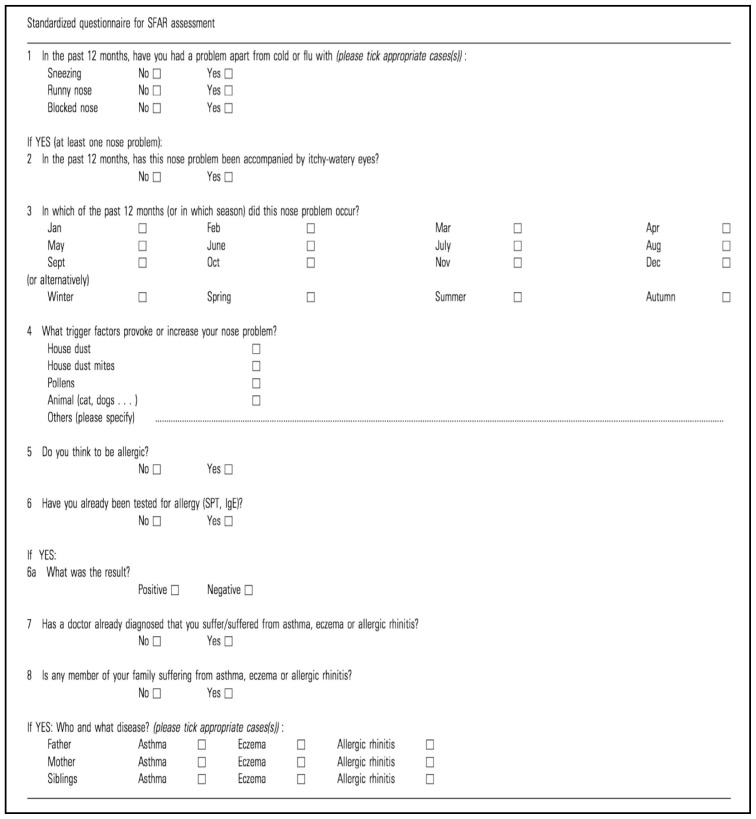

The symptoms of AR that motivate people to seek medical attention include sneezing, itching, rhinorrhea, and nasal obstruction. However, a definitive diagnosis requires taking a comprehensive history, a clinical examination, and laboratory testing. AR has historically been classified as intermittent, perennial, or occupational, although the Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma Group (ARIA) developed a new classification of AR based on intermittent or persistent symptoms.15–17 Multiple non-instrumental tests for AR have been reported, although few have been validated. Many screening instruments use self-assessment questions, while others rely on a physical assessment. It would be preferable to have a simple tool that could be used by general practitioners and other physicians, such as the Score of Allergic Rhinitis questionnaire (SFAR; Appendix 1), which was created by the Annesi-Maesano group in 2002.1 The SFAR tool uses a structured scoring system with eight questions about symptoms, time of occurrence during the year, triggers, personal and family histories of allergy, and allergy tests. The tool was developed in French using data from 3001 participants,1 and has subsequently been translated into other languages, including Turkish.17 The SFAR tool can quantitatively screen patients for AR and has a superior scoring system, sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values, compared to other tools. This tool is easy to use, can be completed in <3 min, and provides useful information for studying the prevalence and causes of AR. However, we are unaware of a validated Arabic version of the SFAR tool. Thus, we translated, culturally adapted, and validated the SFAR questionnaire for the Arabic population.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Development of the Arabic SFAR

The four steps for validation of the Arabic SFAR followed the standard recommendations for cross-cultural adaptation.18–20 Three fluently bilingual otolaryngologists translated the original English version of SFAR into Arabic (Appendix 2). The questionnaire was subsequently back-translated into English and compared to the original SFAR items by two other qualified professional translators who were familiar with American English and Arabic. The backward-translated version was then sent to the investigators for review and comments. The original and backward-translated versions were compared, based on a critical assessment and adaptation of semantic equivalence to determine whether the original meaning has been retained. The cut-off score to label a participant as having AR was 7, based on the study by Annesi-Maesano et al.1

To detect potential conceptual problems, the preliminary Arabic SFAR was administered to 23 patients with AR and 15 control participants, after obtaining their consent for participation. The Arabic SFAR was subsequently amended according to the participants’ suggestions, with several additional descriptive words added to a few questions to make them easier for the participants to understand. Finally, cultural modification of the Arabic SFAR was performed before it was finalized (Appendix 2).

Study design and sample

The study protocol was approved by the Research Center of Medical College of King Saud University and its Ethical Committee, and all participants provided informed consent. Individuals with poor Arabic reading and writing abilities, or with a non-Arabic mother language, were excluded from this study. This cross-sectional study evaluated 75 control participants and 173 patients with AR, who were recruited from the primary healthcare clinic at King Abdul-Aziz University Hospital in Riyadh during August–November 2016. All patients with AR had signs and symptoms that were confirmed by our otolaryngologists. The controls were healthy individuals who had accompanied the patients to the otolaryngology clinic, but were found to not have AR signs/symptoms by our otolaryngologists. All investigators were otolaryngologist specialists or consultants who were blinded to the purpose of the study.

Before the clinic visit, potential participants were asked to sign the consent form and then complete the Arabic SFAR. The completed questionnaires were placed in sealed envelopes and given to the clinic nurses in order to blind the physicians to the responses. All participants were assessed by our otolaryngologists to document their history, including presence or absence of AR symptoms (sneezing, nasal congestion, watery rhinorrhea, postnasal drip, nasal itching, anosmia/hyposmia, headache, tearing, red eyes, fatigue, and malaise), and completed a physical examination to document AR signs (allergic shiners, nasal crease, swollen nasal mucosa, pale, bluish-gray color, watery nasal discharge, and nasal septum deviation or perforation).

Validation of the tool and statistical analysis

The Arabic SFAR was tested in terms of diagnosis validation and internal consistency. The diagnostic validation was performed by comparing the SFAR scores between the patients and controls. The internal consistency of the Arabic SFAR was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, with a value of 0.7 indicating acceptable reliability. The test-retest reliability was assessed by estimating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the eight items and the total Arabic SFAR score.

Based on normality tests, the data were not normally distributed. Thus, non-parametric statistical tests were used in the study. The mean scores for the individual items and the total Arabic SFAR scores were compared between the AR and control groups using the Mann-Whitney test. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to determine the correlation between the SFAR items and total score. The significance level was set at .05, and all analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software (version 22; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

The AR group included 100 female patients and 73 male patients (mean [SD] age: 38.54 [13.59] years). All patients in the AR group had pale nasal mucosa and swollen hypertrophied turbinates. Clear rhinorrhea and ocular signs were present in 87.3% and 59.5%, respectively. The SFAR scores ranged from 0 to 16, and the mean total SFAR score in the AR group was 10.31 (2.96), compared to 3.93 (2.46) in the control group (P <.0001) (Table 1). All Arabic SFAR items were significantly correlated with the total Arabic SFAR score in the AR group (Table 2). The overall internal consistency of the Arabic SFAR items was satisfactory (Cronbach’s α=0.7), and the total Arabic SFAR scores exhibited good reliability (r=0.836).

Table 1.

Comparison of Arabic SFAR results between the patient and control groups.

| Comparison | N | Mean | Standard deviation | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Item 1 | Patients | 173 | 2.4451 | 0.71009 | <.001 |

| Controls | 75 | 0.6533 | 0.89281 | ||

| Item 2 | Patients | 173 | 1.2023 | 0.98216 | <.001 |

| Controls | 75 | 0.1067 | 0.45242 | ||

| Item 3 | Patients | 173 | 1.2601 | 0.60662 | <.001 |

| Controls | 75 | 0.7467 | 0.71836 | ||

| Item 4 | Patients | 173 | 1.6532 | 0.70377 | .001 |

| Controls | 75 | 1.2267 | 0.98053 | ||

| Item 5 | Patients | 173 | 1.7919 | 0.61241 | <.001 |

| Controls | 75 | 0.0533 | 0.32438 | ||

| Item 6 | Patients | 173 | 0.3353 | 0.74924 | .006 |

| Controls | 75 | 0.08 | 0.39456 | ||

| Item 7 | Patients | 173 | 0.4335 | 0.497 | <.001 |

| Controls | 75 | 0.1867 | 0.39227 | ||

| Item 8 | Patients | 173 | 1.1908 | 0.98449 | .024 |

| Controls | 75 | 0.88 | 0.99946 | ||

| Total | Patients | 173 | 10.3121 | 2.96603 | <.001 |

| Controls | 75 | 3.9333 | 2.46233 | ||

SFAR = score for allergic rhinitis

Table 2.

Correlations between the questionnaire items and the total Arabic SFAR score.

| Arabic SFAR items | Total score | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Item 1 | Correlation | .163 |

| Two-tailed | .032 | |

| p-value | ||

| Item 2 | Correlation | .579 |

| Two-tailed | <.001 | |

| p-value | ||

| Item 3 | Correlation | .550 |

| Two-tailed | <.001 | |

| p-value | ||

| Item 4 | Correlation | .716 |

| Two-tailed | <.001 | |

| p-value | ||

| Item 5 | Correlation | .328 |

| Two-tailed | <.001 | |

| p-value | ||

| Item 6 | Correlation | .469 |

| Two-tailed | <.001 | |

| p-value | ||

| Item 7 | Correlation | .715 |

| Two-tailed | <.001 | |

| p-value | ||

| Item 8 | Correlation | .577 |

| Two-tailed | <.001 | |

| p-value | ||

SFAR = score for allergic rhinitis

DISCUSSION

The present study developed a tool for assessing Arabic patients with suspected AR, as few studies have examined AR in Arabic or Saudi populations. Our preliminary review of the literature revealed research and development of the SFAR tool by Annesi-Maesano’s group.1 That tool has subsequently been adapted and translated into other languages, and has provided similar results in the studies by Ologe et al.,20 Cingi et al.,17 Wang et al.,21 and Piau et al.,22 as well as the present study. The popularity of the SFAR tool is likely related to the fact that it is simple, easily administered, and inexpensive. The present study revealed that, similar to the findings of Cingi et al. and Ologe et al.,17,20 the Arabic SFAR provided satisfactory results for consistency and re-testability in our group of Arabic patients with AR. Furthermore, our findings indicate that the Arabic SFAR can be used to distinguish between patients with AR and healthy people.

Although the present study used a relatively small sample, based on the need to test and validate the translated SFAR, the internal consistency of the Arabic SFAR provided a similar Cronbach’s alpha value (0.7), compared to those from the original SFAR study (0.79)1 and Cingi et al.’s study (0.69).17 Furthermore, the strong correlation between the test and re-test scores indicate that the Arabic SFAR is highly reproducible, and similar results were observed for each item. Moreover, the ability of the Arabic SFAR to distinguish between patients with AR and control participants was confirmed based on the blinded examinations that were performed by our otolaryngologists. Thus, the total Arabic SFAR score and item-specific scores may be useful for evaluating Arabic patients with suspected AR.

One potential limitation in the present study is the absence of objective allergy testing. However, debate remains on the accuracy and validity of the skin prick test for diagnosing allergies (including AR).23–26 Moreover, since 1998, three large expert panels have made recommendations regarding the diagnosis of allergic and nonallergic rhinitis, which do not specifically recommend allergy testing (e.g., percutaneous skin testing or radioallergosorbent testing) but do indicate that it can be useful in ambiguous or complicated cases. 15,27,28 Thus, the general recommendations for allergy testing vary,29,30 and a systematic review of the evidence regarding allergy testing has indicated that physicians should select tests that alter outcomes or treatment plans.30 In this context, empirical treatment is appropriate for patients with classic symptoms, observation may be appropriate for mild cases, and diagnostic tests may be appropriate if the case involves severe symptoms or an unclear diagnosis, or if the patient is a potential candidate for allergen avoidance treatment or immunotherapy. 30 Another limitation of this study is the absence of random probability sampling, as we selected a convenience sampling method for validation.

In conclusion, the Arabic SFAR is a valid and reliable quantitative screening tool for patients with AR. The tool provided results that were comparable to those of the original SFAR. The Arabic SFAR was able to clearly differentiate between cases of AR and healthy controls, which makes it a simple and rapid assessment tool for clinicians who are studying this disease.

Appendix 1.

Appendix 2.

REFERENCES

- 1.Annesi-Maesano I, Didier A, Klossek M, Chanal I, Moreau D, Bousquet J. The score for allergic rhinitis (SFAR): a simple and valid assessment method in population studies. Allergy. 2002;57:107–114. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.1o3170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trikojat K, Buske-Kirschbaum A, Plessow F, Schmitt J, Fischer R. Memory and multitasking performance during acute allergic inflammation in seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47:479–487. doi: 10.1111/cea.12893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beasley R. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet. 1998;351:1225–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nahhas M, Bhopal R, Anandan C, Elton R, Sheikh A. Prevalence of allergic disorders among primary school-aged children in Madinah, Saudi Arabia: two-stage cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobki SH, Zakzouk SM. Point prevalence of allergic rhinitis among Saudi children. Rhinology. 2004;42(3):137–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdulrahman H, Hadi U, Tarraf H, Gharagozlou M, Kamel M, Soliman A, et al. Nasal allergies in the Middle Eastern population: results from the “Allergies in Middle East Survey”. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26(Suppl 1):S3–23. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alqahtani JM. Asthma and other allergic diseases among Saudi school children in Najran: the need for a comprehensive intervention program. Ann Saudi Med. 2016;36:379–385. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2016.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al Anazy FH, Zakzouk SM. The impact of social and environmental changes on allergic rhinitis among Saudi children. A clinical and allergological study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;42:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(97)00103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabry EY. Prevalence of allergic diseases in a sample of Taif citizens assessed by an original Arabic questionnaire (phase I) A pioneer study in Saudi Arabia. Allergol Immunopathol. 2011;39:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bener A, al-Jawadi TQ, Ozkaragoz F, al-Frayh A, Gomes J. Bronchial asthma and wheeze in a desert country. Indian J Pediatr. 1993;60:791–797. doi: 10.1007/BF02751050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al Frayh AR, Shakoor Z, Gad El Rab MO, Hasnain SM. Increased prevalence of asthma in Saudi Arabia. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001;86:292–296. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)63301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mustafa S, Gad-El-Rab MO. A study of clinical and allergic aspects of rhinitis patients in Riyadh. Ann Saudi Med. 1996;16:550–553. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1996.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klossek JM, Annesi-Maesano I, Pribil C, Didier A. INSTANT: national survey of allergic rhinitis in a French adult population based-sample. Presse Med. 2009;38:1220–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2009.05.012. [in French] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adebola SO, Abidoye B, Ologe FE, Adebola OE, Oyejola BA. Health-related quality of life and its contributory factors in allergic rhinitis patients in Nigeria. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2016;43:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N Aria Workshop Group; World Health Organization. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(5 Suppl):S147–S334. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, Denburg J, Fokkens WJ, Togias A, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) 2008 update. Allergy. 2008;86:8–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cingi C, Songu M, Ural A, Annesi-Maesano I, Erdogmus N, Bal C, et al. The score for allergic rhinitis study in Turkey. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011;25:333–337. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1417–1432. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guillemin F. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of health status measures. Scand J Rheumatol. 1995;24:61–63. doi: 10.3109/03009749509099285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ologe FE, Adebola SO, Dunmade AD, Adeniji KA, Oyejola BA. Symptom Score for Allergic Rhinitis. J Olaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148:557–563. doi: 10.1177/0194599813477605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang YH, Wang YC, Wu PH, Hsu L, Wang CY, Jan CR, et al. A cross-sectional study into the correlation of common household risk factors and allergic rhinitis in Taiwan’s tropical environment. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2017;10:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piau JP, Massot C, Moreau D, Aēt-Khaled N, Bouayad Z, Mohammad Y, et al. Assessing allergic rhinitis in developing countries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:506–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Majamaa H, Moisio P, Holm K, Turjanmaa K. Wheat allergy: diagnostic accuracy of skin prick and patch tests and specific IgE. Allergy. 1999;54(8):851–856. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soares-Weiser K, Takwoingi Y, Panesar SS, Muraro A, Werfel T, Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, et al. The diagnosis of food allergy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2014;69(1):76–86. doi: 10.1111/all.12333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krouse JH, Shah AG, Kerswill K. Skin testing in predicting response to nasal provocation with alternaria. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(8):1389–1393. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200408000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gungor A, Houser SM, Aquino BF, Akbar I, Moinuddin R, Mamikoglu B, et al. A comparison of skin endpoint titration and skin-prick testing in the diagnosis of allergic rhinitis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2004;83(1):54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dykewicz MS, Fineman S, Skoner DP, Nicklas R, Lee R, Blessing-Moore J, et al. Diagnosis and management of rhinitis: complete guidelines of the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters in Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;81(pt 2):478–518. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)63155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Evidence report/technology assessment No. 54. Management of allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. May, 2002. [Accessed online November 1, 2005]. at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/tp/rhintp.htm.

- 29.Orlandi R, Baker J, Andreae M, Dubay D, Erickson S, Terrell J for the Allergic Rhinitis Guideline Team. University of Michigan Health System. Guidelines for clinical care. Allergic rhinitis. [Accessed online November 1, 2005]. at: http://cme.med.umich.edu/pdf/guideline/allergic.pdf.

- 30.Gendo K, Larson EB. Evidence-based diagnostic strategies for evaluating suspected allergic rhinitis. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:278–289. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-4-200402170-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]