Abstract

The novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) has been identified as a cause of pneumonia; however, it has not been reported as a cause of acute myocarditis. A 60-year-old man presented with pneumonia and congestive heart failure. On the first day of admission, he was found to have an elevated troponin-I level and severe global left ventricular systolic dysfunction on echocardiography. The serum creatinine level was found mildly elevated. Chest radiography revealed in the lower lung fields accentuated bronchovascular lung markings and multiple small patchy opacities. Laboratory tests were negative for viruses known to cause myocarditis. Sputum sample was positive for MERS-CoV. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance revealed evidence of acute myocarditis. The patient had all criteria specified by the International Consensus Group on CMR in Myocarditis that make a clinical suspicion for acute myocarditis. This was the first case that demonstrated that MERS-CoV may cause acute myocarditis and acute-onset heart failure.

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is a novel coronavirus that was reported for the first time in June 2012, in Saudi Arabia in a patient with pneumonia.1 Later, many other cases of pneumonia due to MERS-CoV infection have been reported in other countries such as United Kingdom2 and Germany.3 A majority of the patients diagnosed with MERS-CoV infection require hospitalization to the intensive care unit (ICU) and mechanical ventilation. In-hospital mortality is very high and is expected to reach 65%.4

CASE

A previously healthy 60-year-old man presented to the emergency room because of a 4-day history of fever, shortness of breath, cough with yellowish sputum, and left side chest pain, which was worsened by inspiration. Physical examination showed a body temperature of 38°C, blood pressure of 115/70 mm Hg, pulse rate of 120 beats per minute, and respiratory rate of 24 per minute. The jugular venous pressure was elevated, as assessed clinically. Auscultation of his chest revealed widespread crackles.

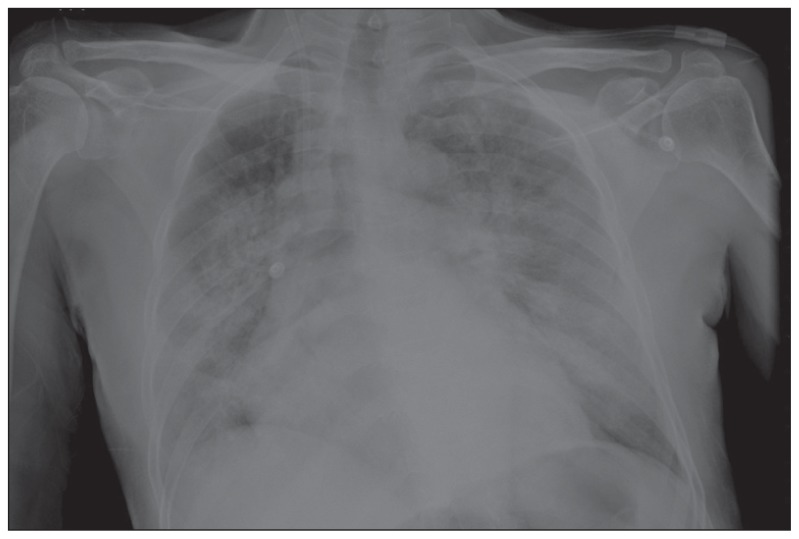

Laboratory tests obtained on admission showed an elevated troponin-I level of 1.13 μg/L and an elevated pro-brain natriuretic peptide level of 6000 pg/ml, which increased to 8906 pg/ml on the second day. White blood cell count was 7.4×103 per mm3, which increased to 18×103 per mm3 on the third day as the highest level (with 68% neutrophils and 27% lymphocytes). Serum creatinine level was mildly elevated, to 120 μmol/L. Chest radiography revealed accentuated bronchovascular lung markings and multiple small patchy opacities present in the lower lung fields. Another chest radiography performed 3 days later revealed that the opacities had become larger and denser (Figure 1). Electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia at a rate of 120 beats per minute and diffuse T-wave inversion. Transthoracic echocardiography performed on the first day showed severe global left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction and small pericardial effusion.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray on the third day of admission. Accentuated bronchovascular lung markings and multiple patchy opacities present in both lungs.

The patient was admitted to the ICU as a case of pneumonia and was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics (intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 g every 6 hours and azithromycin 500 mg once daily). He also received furosemide intravenously for congestive heart failure. Routine sputum and blood cultures were negative for bacterial infections.

A differential diagnosis of the severe LV dysfunction included myopericarditis, ischemic cardiomyopathy presented with acute coronary syndrome, and stress-induced cardiomyopathy. Myopericarditis was supported by chest pain description. The elevated level of troponin could be attributed to any 1 of the possibilities discussed here.

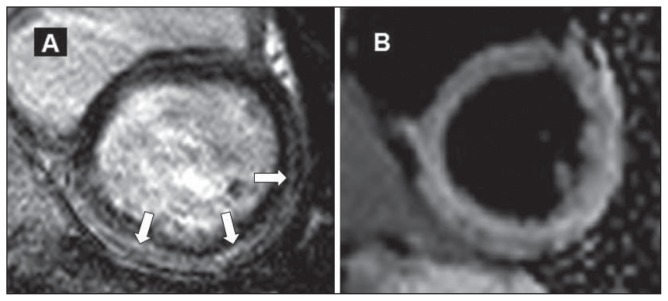

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) was performed using a 1.5-T Siemens scanner. Multislice, T1-weighted (T1w), inversion-recovery gradient-echo sequences, and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) images were acquired 10 minutes after injection of 0.1 mmol/kg gadoterate (a gadolinium-containing contrast agent). T2-weighted (T2w) short-tau inversion recovery (T2w-STIR) images were obtained before contrast administration. LGE images revealed a linear pattern of increased signals in sub-epicardial regions of inferior and lateral walls of the left ventricle (Figure 2A). This pattern of LGE is consistent with myocarditis.5–8 T2w images assessed visually showed an increased signal intensity at the apical and lateral walls of the left ventricle (Figure 2B). This is evidence of myocardial edema and acuteness of the myocardial injury.8,9

Figure 2.

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR). Panel A shows T1w LGE image in short-axis view. Arrows point to the sub-epicardial accumulation of contrast in the inferior and lateral walls. Panel B shows T2w short-tau inversion recovery (T2w-STIR) image in a short-axis view. There is an increased myocardial signal intensity, which is more prominent in the lateral and inferior walls.

Laboratory tests were negative for viruses known to cause myocarditis: influenza, parainfluenza, adenovirus, coxsackievirus B, parvovirus B19, echovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus. Bacterial blood cultures were negative for any growth.

As a result of published reports on MERS-CoV fatal infection in Saudi Arabia, the Saudi Ministry of Health requested that all patients with pneumonia requiring admission to the ICU be tested for MERS-CoV. A sample of the patient’s sputum was sent for reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction assay, which was positive for MERS-CoV.

During the second week of admission, the patient required hemodialysis because of acute renal failure, which improved after 4 weeks. He also required intubation for mechanical ventilation because of respiratory failure that continued for 6 weeks. He was then transferred to the general admission ward and stayed there for about 1 month for rehabilitation. LV systolic function remained severely impaired on echocardiography performed 3 months after the first one. He was discharged home when his clinical condition was stable.

DISCUSSION

The clinical presentation of patients with acute myocarditis varies, ranging from a subclinical disease to a fulminant heart failure and cardiogenic shock. According to the European Study of Epidemiology and Treatment of Inflammatory Heart Disease, 72% of patients had dyspnea, 32% had chest pain, and 18% had arrhythmias.10 The patient had all criteria specified by the International Consensus Group on CMR in Myocarditis that make a clinical suspicion for acute myocarditis.8 The patient had left side chest pain suggestive of pericarditis, evidence of myocardial injury (elevated troponin and severe global LV dysfunction on the first day of presentation), and confirmed viral infection. The elevated level of troponin is known to occur in about 35% of myocarditis cases.11

Acute myocarditis can be confidently diagnosed using CMR.5–8 The signal response from normal myocardium is reduced during LGE imaging, revealing areas with increased accumulation of gadolinium as bright regions that has been shown to reflect a myocardial injury. In this case, the distribution of LGE in the sub-epicardial region is consistent with myocarditis. Myocardial injury due to myocarditis can be easily differentiated from an ischemic injury, as the latter results in sub-endocardial involvement on LGE images.8 LGE is generally absent in stress-induced cardiomyopathy.12 T2w-STIR imaging is used to detect tissue edema, which indicates acuteness of the myocardial injury.8,9 When both criteria, i.e., LGE and presence of edema, are met, the diagnosis of acute myocarditis can be made with an excellent specificity of 91% when validated by endomyocardial biopsy.13 A third criterion that supports the diagnosis is an increased global myocardial early enhancement ratio between the myocardium and skeletal muscle in gadolinium-enhanced T1w images.8 For the patient in this study, the skeletal muscle mass size in obtained images was not satisfactory for assessment and, thus, certain criterion could not be applied. However, in the setting of clinically suspected myocarditis, 2 criteria are required to diagnose acute myocarditis according to the International Consensus Group on CMR in Myocarditis (Lake Louise Consensus Criteria).8

No improvement in LV systolic function was observed on echocardiography performed 3 months after the first one. This was not surprising, as among patients with acute myocarditis presented with severe LV dysfunction, about 50% developed chronic ventricular systolic dysfunction.14,15 This case report demonstrates that MERS-CoV may cause acute myocarditis and acute-onset heart failure.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bermingham A, Chand MA, Brown CS, Aarons E, Tong C, Langrish C, Hoschler K, Brown K, Galiano M, Myers R, Pebody RG, Green HK, Boddington NL, Gopal R, Price N, Newsholme W, Drosten C, Fouchier RA, Zambon M. Severe respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus, in a patient transferred to the United Kingdom from the Middle East, September 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:20290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchholz U, Müller MA, Nitsche A, Sanewski A, Wevering N, Bauer-Balci T, Bonin F, Drosten C, Schweiger B, Wolff T, Muth D, Meyer B, Buda S, Krause G, Schaade L, Haas W. Contact investigation of a case of human novel coronavirus infection treated in a German hospital, October–November 2012. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assiri Abdullah, McGeer Allison, Perl Trish M, Price CS, Al Rabeeah AA, Cummings DA, Alabdullatif ZN, Assad M, Almulhim A, Makhdoom H, Madani H, Alhakeem R, Al-Tawfiq JA, Cotten M, Watson SJ, Kellam P, Zumla AI, Memish ZA. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:407–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahrholdt H, Wagner A, Deluigi CC, et al. Presentation, patterns of myocardial damage, and clinical course of viral myocarditis. Circulation. 2006;114:1581–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.606509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahrholdt H, Goedecke C, Wagner A, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance assessment of human myocarditis: a comparison to histology and molecular pathology. Circulation. 2004;109:1250–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118493.13323.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdel-Aty H, Boye P, Zagrosek A, et al. Diagnostic performance of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in patients with suspected acute myocarditis: comparison of different approaches. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1815–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedrich Matthias G, Sechtem Udo, Schulz-Menger Jeanette, Holmvang G, Alakija P, Cooper LT, White JA, Abdel-Aty H, Gutberlet M, Prasad S, Aletras A, Laissy JP, Paterson I, Filipchuk NG, Kumar A, Pauschinger M, Liu P. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in myocarditis: A JACC White Paper. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1475–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdel-Aty H, Zagrosek A, Schulz-Menger J, et al. Delayed enhancement and T2-weighted cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging differentiate acute from chronic myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;109:2411–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127428.10985.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hufnagel G, Pankuweit S, Richter A, et al. The European Study of Epidemiology and Treatment of Cardiac Inflammatory Diseases (ESETCID) First epidemiological results. Herz. 2000;25:279–85. doi: 10.1007/s000590050021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith SC, Ladenson JH, Mason JW, Jaffe AS. Elevations of cardiac troponin I associated with myocarditis. Experimental and clinical correlates. Circulation. 1997;95:163–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eitel I, von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F, Bernhardt P, Carbone I, Muellerleile K, Aldrovandi A, Francone M, Desch S, Gutberlet M, Strohm O, Schuler G, Schulz-Menger J, Thiele H, Friedrich MG. Clinical characteristics and cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings in stress (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy. JAMA. 2011;306:277–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutberlet M, Spors B, Thoma T, Bertram H, Denecke T, Felix R, Noutsias M, Schultheiss HP, Kühl U. Suspected chronic myocarditis at cardiac MR: diagnostic accuracy and association with immunohistologically detected inflammation and viral persistence. Radiology. 2008;246:401–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2461062179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quigley PJ, Richardson PJ, Meany BT. Long term follow up of acute myocarditis. Correlation of ventricular function and outcome. Eur Heart J. 1987;8:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mason JW, O’Connel JB, Herskowitz A, et al. A clinical trial of immunosuppressive therapy for myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:269–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508033330501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]