Abstract

BACKGROUND

Cancer is the second leading cause of death, following cardiovascular diseases, accounting for 12% of annually reported deaths in Bahrain. We determined the epidemiological patterns of malignancies in Bahrain and compared them with those of other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and other developed countries.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Data for the study were obtained from the Bahrain Cancer Registry (BCR) database. The overall and type-specific 5-year average incidence rates were calculated for the years 1998–2002 and derived using the CANREG software formula. The incidence rates for the year 2000 were used for comparing Bahrain with those of other countries in the Arabian Gulf using the statistics of the Gulf Centre for Cancer Registration.

RESULTS

During the 5-year period there were 2405 cancer cases in Bahrain (1239 males and 1166 females), with an annual average of 481 cases. The world age-standardized incidence rates (ASR) were 162.3 and 145.2 per 100 000 for Bahraini males and females, respectively. Generally, Bahraini men had a higher ASR for most cancer types, and the most common type of cancer was lung for males (35.2 per 100 000), followed by bladder (14.5) and prostate (14.3), and breast for females (46.8), followed by lung (12.2) and ovary (7.7).

CONCLUSION

Compared to other Gulf countries, Bahrain had higher incidence rates for cancers of the lung, prostate, colorectum, bladder, kidney, pancreas and leukemia among males and for cancers of the breast, lung, bladder, thyroid, uterus and ovary among females. A rising trend in cancer incidence is likely to continue for years or even decades to come.

Cancer is one of the major health problems in the Kingdom of Bahrain. It is the second leading cause of death, after cardiovascular diseases, accounting for 12% of annually reported deaths.1 It inflicts a substantial burden on healthcare services, consuming a large proportion of financial and other resources.1

The role of cancer registries in cancer control is not equivocal.2 Recognizing this important role, the Ministry of Health (MOH) put cancer control among its highest priorities and established a cancer registry. The establishment of the Bahrain Cancer Registry (BCR) through a ministerial decree (No. 5, 1994) was a key step in declaring cancer as a notifiable disease and laying the foundation for a database. This paper presents the first 5 years experience of the newly established registry. It describes the epidemiological patterns of malignancies in Bahrain and compares them with those of other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and other developed countries.

The Kingdom of Bahrain is located centrally on the southern shores of the Arabian Gulf, and comprises of an archipelago of islands with a total land area of 717.5 square kilometers. Bahrain island is the largest of these islands accounting for nearly 83% of the total area of the Kingdom including the capital, Manama.3 According to the 2001 census, the total population of Bahrain was 650 604 persons of whom 405 667 (62.4%) were Bahraini and 244 937 non-Bahraini. The growth rate between the 1991 and the 2001 censuses was 2.7% for the total population, 2.5% for the Bahraini and 3.1% for the non-Bahraini.4 The 5-year average estimated midyear population for 1998–2002 was 638 033 of whom, 398 455 (62.5%) were Bahraini, and 239 578 (37.5%) were non-Bahraini.3 It should be noted here that the majority of the non-Bahraini population (69.2%) are males, who form the major part of the working force. The non-Bahraini population is unstable, characterized by a very rapid turn over during the year, and their transitional nature could affect the interpretation of cancer occurrences.

The government is committed to providing a high standard of comprehensive health care to residents,5 including public health, and primary, secondary and tertiary care services. Primary health care is delivered through a network of 22 well-equipped health centers, staffed with qualified family physicians and allied health personnel and distributed in all geographic regions. General and specialized secondary care is provided through the main government hospital, Salmaniya Medical Complex (SMC), which has recently been expanded to house the new Oncology Services Centre that is equipped with the latest diagnostic and therapeutic technology to provide different types of treatment including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy and bone marrow transplantation.1 The Bahrain Defense Force (BDF) Hospital is the second general secondary hospital that primarily serves Ministry of Defense employees and their families and accommodates the centre for cardiac surgery in the country. Secondary care is also provided by six other private hospitals. Together, the government and private hospitals have a capacity of around 2000 beds and ratios of 22 doctors of different specialties and 50 nurses for every 10 000 population.1

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The BCR is a population-based registry where all physicians in the Kingdom were requested in 1994, following the ministerial decree, to report all cancer cases to the Cancer Registry Office, which is organizationally annexed to the Medical Review Office at SMC. A fulltime epidemiologist and a part-time medical records technician working as a tumor registrar operate the registry.

Cases included in the study were those registered as having a malignant disease in the BCR between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2002, whether the cancer was microscopically or clinically diagnosed. Personal, clinical and tumor details are entered in the registry using a specially designed registration form, and checked for duplication and consistency using the CANREG IV software that was developed by The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) specifically for cancer registration.6 Coding anatomical sites and morphology of tumors is done according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O-3).7

In addition to passive notification, case finding is enhanced by several approaches. First, medical records of patients admitted with cancer to SMC, which is the main source of cases, are sorted at the Medical Record Department upon discharge and checked for their registration status. Second, the Registrar visits the BDF Hospital periodically to review and identify lists of newly diagnosed cases. Third, the Registrar also receives cancer death notifications from the Birth and Death Registration Office, MOH, on a regular basis. The “Death Certificate Notification” (DCN) cases are cross-matched with the registered cases to sort out the unmatched cases (true DCN), which are then followed back for any hospital information related to malignancy and date of diagnosis. Of these true DCN cases, any case would be registered as an ordinary one if there were enough information indicating that it was an incident case. Those with insufficient clinical data or if the information was not indicative of the cancer are registered as “Death Certificate Only” (DCO) cases.

Using the check program, which is built-in within the CANREG software, data were examined for duplicate registration as well as for illogical errors in combinations of variables such as site-sex, site-morphology and age-morphology. Data was also checked for illogical combinations that could not be captured by CANREG such as morphology versus basis of diagnosis (e.g., leukemia), behavior versus stage codes (for in-situ), basis of diagnosis versus status codes (for DCO) and morphology versus stage. Cases in which diagnosis was based on the histology of metastasis (secondary site) were reviewed to ensure that the depicted site was for the suggested primary and not for the secondary tumor. Missing date of birth was replaced by the first two digits of the Central Population Register number, which represents the year of birth. In this case, the first of January was designated to complete the full date of birth. Missing data for unknown primary site and other variables were sought and recorded when found.

Incidence rates were calculated from the CANREG software, in which crude total and age-sex-specific incidence rates (ASPRs) for each type of cancer were calculated by dividing the number of registered cases in a year by the corresponding estimated mid-year population for the same year, the latter being an approximation of the person-years at risk.

The 5-year average total and ASPRs for the period from 1998 to 2002 were calculated according to the method used in “Cancer Incidence in Five Continents”.8 In this method, the total number of cases registered in the 5-year period is divided by person years at risk derived by multiplying the mid-year estimated population of the middle year (2000) times the number of years of the study period (five years). Rates were standardized for age and sex, by the direct standardization method using the world standard population supplied by the CANREG software.

The age-standardized incidence rates (ASRs) of some of the leading cancers in Bahrain in the year 2000 were compared with the corresponding rates for the same year for Kuwait, Oman and Saudi Arabia.9 These countries were chosen because they have good national coverage and reliable cancer registries, and as data for the 5-year period is not available for these countries, the year 2000 was taken to represent the mid-year of the 1998–2002 period.

RESULTS

Overall cancers

During the 5-year period (1998–2002) there were 2405 cancer cases in Bahrain (1239 males and 1166 females) with an annual average of 481 cases. Of the males, 962 were Bahraini and 277 non-Bahraini. The corresponding figures for females were 964 and 202, respectively. The average annual crude incidence cancer rates for males were 95.7/100 000 among the Bahrainis, 33.4/100 000 among the non-Bahrainis, and 67.6/100 000 among all males combined. The corresponding rates for females were 97.7, 54.7 and 86.0 per 100 000 women, respectively. The world ASRs were 162.3 and 145.2 per 100 000 among Bahraini males and Bahraini females, respectively. The corresponding rates for the non-Bahraini males and females were 116.3 and 115.4 per 100 000, respectively, and the ASR for both Bahrainis and the non-Bahrainis were 147.7 and 139.1 per 100 000, respectively. Generally, ASPRs increased with age for both Bahraini and non-Bahraini males and females (Figure 1). Compared to males, females showed higher rates at young ages and lower rates at older ages among both Bahrainis and non-Bahrainis.

Figure 1.

Average age-specific incidence rates of all cancers by nationality and gender, 1998–2002

Cancer among the Bahraini population

Bahraini males had higher ASRs than females in almost all common cancers except thyroid cancer (Table 1). Bladder cancer was four times more common, cancer of the lung almost three times more common while colorectal and pancreatic cancers were two times more common among males than females. In contrast, thyroid cancer was almost seven times more common among females than males.

Table 1.

Age-standardized rate (world)/100 000 for common cancers among Bahraini males and females, 1998–2002.

| Cancer type | Male | Female | M/F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trachea, bronchus and lung (C33–34) | 35.2 | 12.2 | 2.9:1 |

| Colorectal (C18–20) | 12.8 | 7.3 | 1.8:1 |

| Leukemia (C91–95) | 9.1 | 4.4 | 2.1:1 |

| Bladder (C67) | 14.5 | 3.8 | 4.4:1 |

| Non-Hogdkin’s lymphoma (C82–85;96) | 7.9 | 5.8 | 1.4:1 |

| Stomach (C16) | 8.7 | 5.4 | 1.6:1 |

| Thyroid (C73) | 1.1 | 7.6 | 1:6.9 |

| Kidney (C64–66;C68) | 5.2 | 3.5 | 1.4:1 |

| Liver (C22) | 5.2 | 3.5 | 1.5:1 |

| Pancreas (C25) | 4.9 | 2.8 | 1.8:1 |

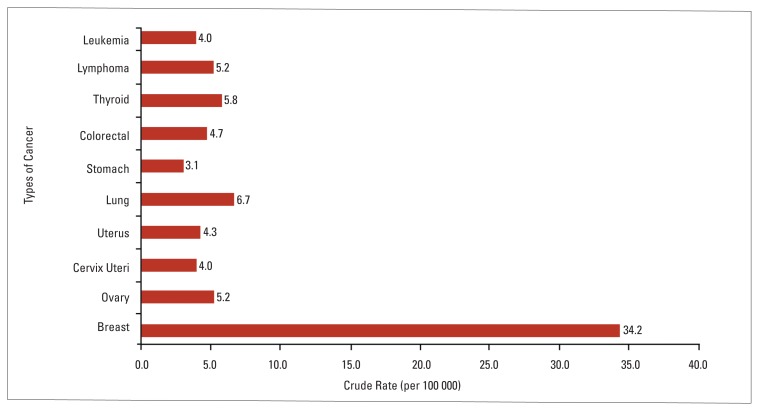

Bronchial and lung cancer is the commonest cancer among Bahraini males, followed by bladder, prostate, colorectal cancers, and leukemia (Figure 2). The commonest five cancers among Bahraini females are breast, lung, thyroid, ovary and colorectal (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Incidence rates of commonest types of cancer among Bahraini males, 1998–2002.

Figure 3.

Incidence rates of commonest types of cancer among Bahraini females, 1998–2002.

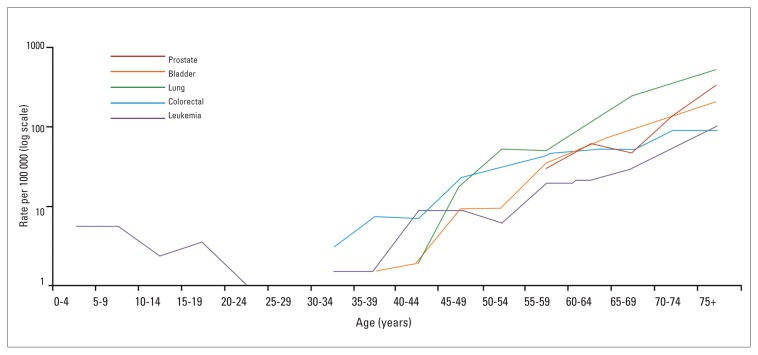

The ASPRs of the five commonest cancers among Bahraini males and females (Figures 4, 5) indicate large gaps between the leading cancer in each sex and other cancers at all age groups. Lung cancer among males increases steeply with age, particularly at the older ages. Breast cancer has a bimodal distribution among Bahraini females with the first mode between the mid 40’s and the mid 50’s and the second at the 65–69 years age group. Prostate cancer has a pattern similar to that of lung cancer among males but with a delayed start. Bladder cancer directly increases with age after the age of 40 years among males. In males, leukemia has a similar pattern as that of prostate cancer but with lower rates at all age groups. Colorectal cancer in males has a peak in the 70–74 years age group. Lung cancer among Bahraini females has an identical age pattern as that of the males with lower rates at all age groups. Colorectal cancer among females has a slow and gradual increase with a peak at the age 55–59 years and higher rates from 65 years and above. The ASPRs of colorectal cancers among females are lower than their male counterparts. Ovarian cancer has a bimodal distribution with age while thyroid cancer is unimodal with its highest peak at the age of 60–64 years.

Figure 4.

Age-specific incidence rates of five commonest cancers among Bahraini males, 1998–2002.

Figure 5.

Age-specific incidence rates of five commonest cancers among Bahraini females, 1998–2002.

Comparing of the sex-specific cancers among the Bahraini with their counterparts in GCC countries population, Bahraini females have the highest incidence rates of breast, uterus and ovarian cancers and the second for cervical cancer among GCC countries, and Bahraini males have the highest ASR for prostate cancer in the year 2000 (Tables 2, 3). The ASR for breast cancer among Bahraini females in that year was 57.2 per 100 000. The corresponding rates for Kuwaiti, Omani and Saudi females were 41.7, 14.9 and 13.9 per 100 000, respectively. The ASRs for ovarian and endometrial cancers among Bahraini females were 8.2 and 5.5 per 100 000, respectively. The corresponding rates were 4.3, and 3.0 for Kuwaiti, and 6.0, 1.3 for Omani, and 2.2 and 2.4 per 100 000 for Saudi females, respectively. Bahrain ranks second to Oman in cancer of the cervix, the rate being 4.4 per 100 000 in 2000 for the Bahraini and 7.0 per 100 000 for the Omani females. The rates for Kuwaiti and Saudi females in 2000 were 2.3 and 2.1 per 100 000, respectively (Table 2). The ASR for cancer of the prostate among Bahraini males was 19.3 per 100 000 in 2000. The corresponding rates in the same year were 7.3, 8.7 and 3.6 per 100 000 among Kuwaiti, Omani and Saudi males (Table 3).

Table 2.

Age-standardized rate (world)/100 000 for common cancers among Bahraini females and their counterparts in selected Gulf Cooperation Council countries, 2000.

| Site (ICD-10) | Bahrain | Kuwait | Oman | Saudi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast (C50) | 57.2 | 41.7 | 14.9 | 13.9 |

| Trachea, bronchus and lung (C33–34) | 12.3 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 1.3 |

| Colorectal (C18–20) | 9.0 | 14.7 | 4.4 | 4.5 |

| Cervix uteri (C53) | 4.4 | 2.3 | 7.0 | 2.1 |

| Uterus (C54–55) | 5.5 | 3 | 1.3 | 2.4 |

| Ovary (C56) | 8.2 | 4.3 | 6.0 | 2.2 |

| Leukemia (C91–95) | 2.6 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 3.1 |

| Bladder (C67) | 3.7 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| Non-Hogdkin’s lymphoma (C82–85;C96) | 5.1 | 3.5 | 5.4 | 3.9 |

| Stomach (C16) | 6.5 | 0.9 | 5.6 | 1.5 |

| Thyroid (C73) | 8.1 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4.5 |

| Kidney (C64–66;C68) | 5.6 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 0.9 |

| Liver (C22) | 7.3 | 0.6 | 3.1 | 2.7 |

| Pancreas (C25) | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

Table 3.

Age-standardized rate (world)/100 000 for common cancers among Bahraini males and their counterparts in selected GCC Countries, 2000.

| Site (ICD-10) | Bahrain | Kuwait | Oman | Saudi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trachea, Bronchus and Lung (C33–34) | 33.5 | 16.0 | 8.8 | 4.3 |

| Prostate (C61) | 19.3 | 7.3 | 8.7 | 3.6 |

| Colorectal (C18–20) | 12.5 | 10.2 | 4.1 | 4.7 |

| Leukemia (C91–95) | 7.1 | 2.8 | 5.9 | 3.4 |

| Bladder (C67) | 14.5 | 6.0 | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| Non-Hogdkin’s lymphoma (C82–85;C96) | 5.6 | 10.1 | 7.7 | 5.3 |

| Stomach (C16) | 11.2 | 2.5 | 13.2 | 2.7 |

| Thyroid (C73) | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| Kidney (C64–66;C68) | 6.5 | 5.9 | 2.6 | 1.9 |

| Liver (C22) | 7.4 | 4.0 | 5.9 | 6.1 |

| Pancreas (C25) | 4.1 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.5 |

Cancer of the lung was highest in the Bahraini compared to their Kuwaiti, Omani and Saudi counterparts in that year. It was 8 times more common in Bahraini than Saudi males and nearly 10 times more common among the Bahraini than the Saudi females. Bahrain had the highest rates of bladder cancer in both sexes compared to the other GCC countries. The male rates were 3.9 times higher in the Bahraini compared to the Saudi, 4 times compared to the Omani and 2.4 times compared to the Kuwaiti. The Bahraini female rates were 3.7 times that of the Saudi, 2.5 times that of the Omani and 2 times of the Kuwaiti female rates for bladder cancer. Bahraini females had the highest incidence rate of thyroid cancer in the GCC countries while the Bahraini males had a very slightly higher ASR. Bahraini males had also the highest rates of colorectal, kidney, liver and pancreatic cancers. Moreover, the Bahraini females had the highest ASRs in GCC countries for cancers of the stomach, kidney, liver and pancreas. Bahraini males were second for stomach cancer while females occupied the same rank for colorectal cancer and leukemia (Tables 2, 3).

DISCUSSION

Before any interpretation of the findings can be made, completeness of registration and the quality of the data need to be addressed. It is known that in their early stages registries face a problem of incompleteness, which improves when more vigilant quality control measures are applied and the awareness of notifying physicians of the existence and benefits of the registry increases.10 Cancer registration in Bahrain started in 1994 and, as with any newly established registry, there were some difficulties in ascertaining all cases and gathering all the required information as well as in coding and validation procedures. From 1998 onward, registration was done following a set of rules described in the manual of registration of the World Health Organization11 and checking the data through CANREG software. As for the coverage, in the years prior to 1998, registered cases were those reported from the SMC, the only hospital that provided oncology care and radio- and chemotherapy in the country. Coverage is considered good as not less than three fourths of the cases in Bahrain are diagnosed at SMC. The cooperation with the BDF Hospital, since 1998, yielded better coverage, especially for cases that might be diagnosed and treated overseas. Moreover, coverage is further enhanced by the routine cross-checking of the BCR with the death register.

Taking into consideration possible artifacts in the currently presented incidence statistics of the disease, Bahrain is right in the heart of the third stage of transition, according to Omran’s theory of epidemiologic transition,12 where chronic diseases, namely those of the cardiovascular system, cancer and diabetes are dominating the main burden of disease. They account for more than half of reported annual deaths, with cancer occupying the second rank of leading causes of death following cardiovascular diseases.1 This is in line with lifestyle changes that have taken place in the Bahraini community in the last two decades. The prevalence of tobacco smoking is 25% in men and nearly 10% in women.13 In fact, the phenomenon of women smoking is increasing with the spread of sheesha (water pipe) smoking, and the increase in social acceptability of this type of smoking in the Kingdom.13 Moreover, obesity is on the increase with more than half of women and men either overweight or obese, and very few exercise regularly.14,15

The pattern of cancer incidence reported here for males is slightly different from that in the developed countries as lung cancer is the leading type among Bahraini men while prostate cancer has now taken the lead in many of developed countries.16 This could partly be due to the increased screening and early diagnosis, which intensified in the western world. For females, however, the patterns are similar with breast cancer by far the leading type. Breast cancer among Bahraini women (46.8/100 000) is four times that of lung cancer (12.2/100 000), the second commonest. One distinct observation in the incidence of breast cancer in Bahraini females compared to western countries, is that it begins to increase in incidence early in a young age group, a phenomenon which could warrant some genetic predisposition that needs further study. The pattern of cancer in Bahraini males is different from that of other GCC countries. Lung cancer ranks first for Bahraini males in contrast to stomach cancer among the Omani, and leukemia among Saudi males. Breast cancer however, is the most frequent cancer in all females in the GCC countries.9

With the evolving lifestyle behaviors that lead to an increasing risk of cancer occurrence, along with currently modest prevention and control activities, the pattern of common types of cancer in Bahrain is likely to pursue a rising trend for years or even decades to come. This situation is challenging to the health authorities in their attempts to ameliorate the cancer burden on the community. Moreover, in the current healthcare system the government ensures availability and accessibility of cancer preventive and curative services to all residents of the country, which imposes a huge financial burden on the MOH. However, the government has a great opportunity to cut the cost by strengthening cancer preventive programs since about sixty percent of the common cancers in Bahrain are associated with smoking and diet and thus are preventable.17 It is universally accepted that a more than 50% reduction in cancer mortality could be expected from effective anti-tobacco programs (35%) and modification of dietary habits (20%) in developing countries.2,18 Furthermore, about a 20% reduction in breast cancer mortality is achievable through a properly designed and implemented screening program.2,19 A recent systematic review of seven completed and eligible trials showed a similar overall reduction rate, but as the effect was lower in the highest quality trials, the authors concluded that a more reasonable estimate is a 15% relative risk reduction. Meanwhile, the authors warned of the possible harms of over-diagnosis and over-treatment that screening might cause.20

These promising results in all such preventive modalities are, however, not easy to achieve without the realization of the need for resources including organizational, physical and human; and the sustainable commitment to procure them. We must also understand that it is difficult to convince people to put their knowledge about healthy behaviors into practice. For example, anti-tobacco measures may take up to thirty years before their maximum impact on cancer incidence is realized. For that, scientists believe that there will be a strong role for early detection and screening, treatment and palliative care modalities for years to come. They warn that screening is not just testing. It requires good compliance, a high-quality test, efficient referral, effective treatment and adequate follow up.19,21 Above all, the health authorities in Bahrain must invest heavily now in preventive cancer health care and not expect the payback until ten to twenty years from now.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ministry of Health. Health statistics 2004. Manama (Bahrain): Ministry of Heath; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Policies and managerial guidelines. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2002. National cancer control programmes. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Central Statistics Organization. Statistical abstract 2002. Manama (Bahrain): Central Statistics Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Central Statistics Organization. Basic results for population, housing, buildings and establishments census. Part One. Manama (Bahrain): Central Statistics Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health. Policies and strategic directions. Manama (Bahrain): Ministry of Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooke A, Parkin M, Ferlay J. CANREG 4. Version 4.28 [software] Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A, Shamugaratnam K, Sobin L, et al., editors. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parkin DM, Whelan S, Ferlay J, Teppo L, Thomas DB, editors. Cancer incidence in five continents. VIII. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2005. IARC Scientific Publications No 155. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gulf Centre for Cancer Registration. Gulf Cooperation Council countries 2001. Riyadh (Saudi): GCCR; 2004. Cancer incidence report. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esteve J, Benhamou E, Raymond L. Descriptive epidemiology. IV. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1994. Statistical methods in cancer research. IARC Scientific Publications No 128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esteban D, Whelan S, Laudico A, Parkin DM, editors. Manual for cancer registry personnel. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer, International Association of Cancer Registries; 1995. IARC Technical Report No 10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Omran AR. Epidemiologic transition theory revisited thirty years later. Wld hlth quart. 1998;51(2,3,4):99–119. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamadeh RR. Non-communicable diseases among the Bahraini population. A review. East Med Hlth J. 2000;6(5–6):1091–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alsuwair A, Alsayyad J, Aljalahmeh M, Moosa K. Non-communicable diseases profile in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Bahrain: Disease Control Section, Ministry of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamadeh RR. Risk factors of major non-communicable diseases in Bahrain. The need for a surveillance system. Saudi Med J. 2004;25(9):1147–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferlay J, Bary F, Pisani P, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2002. [Version 20] Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. Cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide. IARC Cancer Base No 5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamadeh RR. Avoidable risk factors of cancer in Bahrain. Int J Food Sci Nut. 1998;49:559–564. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doll R, Peto R. The causes of cancer Quantitative estimates of avoidable risks of cancer in the United States today. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller AB. Screening for breast cancer. Is there an alternative to mammography? Asian Pacific J Can Prev. 2005;6:83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gotzsche PC, Nielsen M. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001877.Pub2. Art No.: CD001877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller AB. Perspectives on cancer prevention. Risk Analysis. 1995;6:655–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1995.tb01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]