Abu Bakr Muhammad Ibn Zakariya Al Razi was born in Al Rayy, a town on the southern slopes of El Burz mountains near present-day Tehran, Iran, in the year 865 AD (251 Hegira). His early interests were in music. He then started studying alchemy and philosophy.1 At the age of thirty, he stopped his work and experiments in alchemy due to eye irritation by chemical compounds he was exposed to. Among his discoveries in alchemy, he is credited with the discovery of sulfuric acid and ethanol.

His teacher in medicine was Ali Ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari, a physician and philosopher born to a Jewish family in Merv, Tabaristan of modern-today Iran. Ibn Rabban converted to Islam during the rule of the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mu’tasim who took him into the service of the court, in which he continued under the Caliph Al-Mutawakkil. Al-Razi studied medicine and probably also philosophy with Ibn Rabban. Therefore, his interest in spiritual philosophy can be traced to this master. Al Razi quickly surpassed his teacher, and became a famous physician. He was appointed as director of the hospital of his hometown Al Rayy during the reign of Mansur Ibn Ishaq Ibn Ahmad Ibn Asad of the Samanian dynasty. Al Razi’s fame reached to the capital of the Abbasids. He was called upon by Caliph Al Muktafi to be the chief director of the largest hospital in Baghdad. Al Razi is attributed with a remarkable method for selecting the site of a new hospital. When the Chief Minister of Al Muktafi, named Adhud Al Daullah, requested him to build a new hospital, he had pieces of fresh meat placed in various areas of Baghdad. A few days later, he checked the pieces, and he selected the area where the least rotten piece was found, stating that the “air” was cleaner and healthier there.

Following the death of Caliph Al-Muktafi in 907, Al Razi returned to his hometown Al Rayy. He was in charge of the hospital there and dedicated most of his time for teaching. It is said that he had several circles of students around him. When a patient came with a complaint or someone from the laity had a question; it was passed to the students of the “first circle”. If they could not give an answer, then it was passed to those in the “second circle” and so on. If all failed to give an answer, then it came to Al Razi who gave the final answer.

Al Razi was quite generous and charitable for his patients, treating them in a quite humane manner, giving them treatment without charging them. In his latter years, he had cataract in both eyes and became blind. He died in Al Rayy on October 27, 925 at the age of 60 years.

He wrote more than 224 books on various subjects. His most important work is the medical encyclopedia known as Al-Hawi fi al-Tibb, known in Europe as Liber Continens. His books in medicine, philosophy and alchemy had greatly effected the human civilization, especially in Europe.1 Some authors considered him the greatest Arabic-Islamic physician and one of the most famous known to humanity.2

Richter-Bernburg wrote a comprehensive bio-bibliographical survey of Al Razi’s medical works which had a great impact on posterity, and illustrated the textual scholarship and clinical observations of this greatest medical practitioner and writer.3 His most significant books were:

Kitab Al-Hawi (Liber Continens), a compilation of his readings of Greek and Roman medicine, his own clinical observations and case studies, and methods of treatment during his years of medical practice. It is generally thought that this book was compiled by his students after his death. It was translated in 1279 to Latin by Faraj Ibn Salim, a scholar working at the Court of the king of Sicily. The first Latin edition of the “Continens”, published at Brescia, Italy, in 1486, is the largest and heaviest book printed before 1501. This book was considered the most significant medical book in the medieval ages. The fame of Al Razi as one of the greatest Muslim physicians is mainly due to the case records and histories written in this book.

Kitab Al Mansuri Fi al-Tibb (Liber Medicinalis ad Almansorem) is a concise handbook of medical science that he wrote for the ruler of Al Rayy Abu Salih Al-Mansur Ibn Ishaq, the ruler of Al Rayy around the year 903.

Kitab Man la Yahduruhu Al-Tabib (Book of Who is not Attended by a Physician or A medical Advisor for the General Public) is dedicated to the poor, the traveler, and the ordinary citizen who could consult or refer to it for treatment of common ailments when a doctor was not available.

Kitab Būr’ al-Sā’ah (Cure in an Hour) is a short essay by Al-Razi concerning ailments that he claims can be cured within an hour’s time. They include headache, toothache, earache, colic, itching, loss of feeling in numb extremities, and aching muscles.

Kitab al-Tibb ar-Ruhani (Book of Spiritual Medicine).

Kitab al-Judari wa al-Hasbah (The Book of Smallpox and Measles).

Kitab al-Murshid (The Guide) is a short introduction to basic medical principles that were intended as a lecture to students.

Al Shakook ala Jalinoos, (The Doubt on Galen). In this book he criticized some of Galen’s theories, particularly the four separate “humors” (liquid substances, including blood, phlegm, yellow bile and dark bile), whose balance were thought to be the key to health and a natural body-temperature. He reported that Galen’s descriptions did not agree with his own clinical observations.

Al Syrah al-Falsafiah (The Philosophical Approach).

Kitab Sirr Al-Asrar (Book of Secret of Secrets) deals with alchemy.

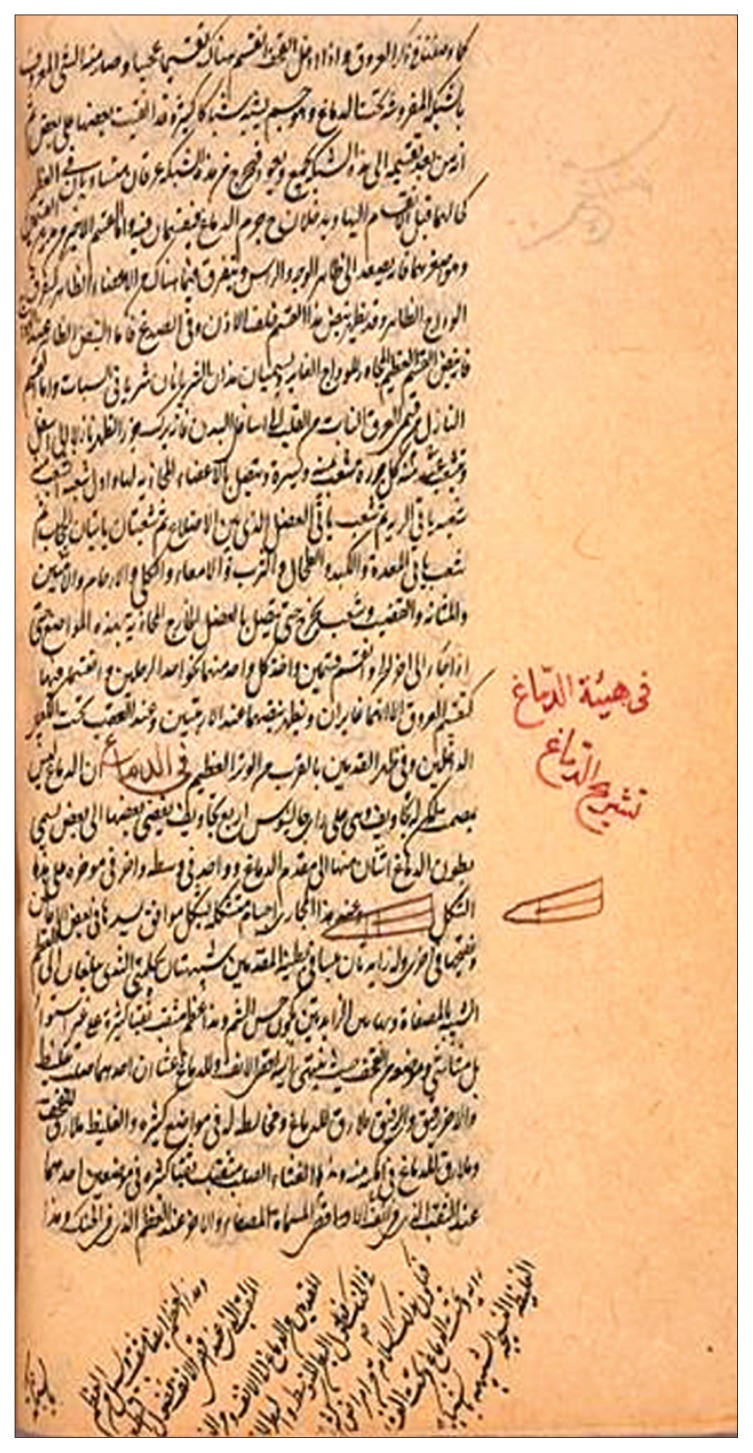

Page from Kitab Al Mansuri fi al Tibb on the morphology and anatomy of the brain (National Library of Medicine). The text in red reads: On morphology of the brain: Anatomy of the brain. The page describes in amazing detail the ventricles of the brain, as well as other observations.

Al Razi utilized case histories extensively in his writing as an educational tool and as documentation of the various illnesses he diagnosed and treated. Alvarez-Millan discussed the description of diseases occurring in Kitab al-Tajārib, the largest and oldest collection of case histories, so far as is known, in medieval Islamic medical literature. Since Al Razi was a prolific medical writer, that discussion includes a review of his medical and therapeutic principles dealing with eye diseases, as described in his learned treatises, and a comparison with those therapies actually employed in his everyday practice. 4 Rhazes made important contributions to neurology and neuroanatomy. He stated that nerves had motor or sensory functions, describing 7 cranial and 31 spinal cord nerves. He assigned a numerical order to the cranial nerves from the optic to the hypoglossal nerves. He classified the spinal nerves into 8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 3 sacral, and 3 coccygeal nerves. In his clinical case reports cited in his books Kitab al-Hawi and Al-Mansuri Fi At-Tibb, he showed an outstanding clinical ability to localize lesions, prognosticate, and describe therapeutic options and reported clinical observations, emphasizing the link between the anatomic location of a lesion and the clinical signs. Al Razi was a pioneer in applied neuroanatomy. He combined a knowledge of cranial and spinal cord nerve anatomy with an insightful use of clinical information to localize lesions in the nervous system.5 In addition, he is credited as the first physician to clearly separate and recognize concussion from other similar neurological conditions.6

In addition to his contributions to the neurological sciences, he was a pioneer in the treatment of mental illnesses. When he was the director of the main hospital in Baghdad, he established a special section for the treatment of the mentally ill. He treated his patients with respect, care, and empathy. As part of discharge planning, each patient was given a sum of money to help with immediate needs. This was the first recorded reference to psychiatric aftercare.7

Al Razi is considered the “original portrayer” of smallpox.8 While serving as the Chief Physician in Baghdad, he was the first to describe smallpox and to differentiate it from measles. He wrote a treatise on the subject: “Kitab al Judari wa al Hasbah”. This book was translated more than dozen times into Latin. In spite of this, it is of interest to know that European physicians continued to confuse these two illnesses until recently.9

The first monograph written on pediatrics was authored by Al Razi. It is known in Latin as Practica Puerorum. Radbill reviewed a Latin translation of this treatise, which is labeled a “Booklet on the Ailments of Children and their Care”.10 The book has 24 chapters dealing with various illnesses in newborns, infants and children. The topics covered included skin diseases, eye and ear diseases, and gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting, abdominal distention, diarrhea and constipation. He devoted chapters to paralysis, epilepsy and enlargement of the head (hydrocephalus).

Al Razi advocated the use of honey as a simple drug and as one of the essential substances included in composed medicines.11 His contributions to pharmacology include the introduction of mercurial ointments. He developed instruments used in apothecaries (pharmacies) such as mortars and pestles, flasks, spatulas, beakers and glass vessels.

There is much more to be discussed about the contributions of this great Muslim scholar to philosophy, chemistry and medicine. We can not give him justice in a short article. The more we learn about his contributions and life dedicated to medicine, the more we value our Islamic cultural and scientific heritage.

REFERENCES

- 1.El Gammal SY. Rhazes contribution to the development and progress of medical science. Bull Indian Inst Hist Med Hyderabad. 1995;25(1–2):135–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ammar S. Abû Bakr ibn Zakaria Er-Razi (Rhazès): the greatest Arabo-Islamic physician and one of the most famous who knew humanity. Tunis Med. 1985;63(12):663–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richter-Bernburg L. Abu Bakr Muhammad al-Razi’s (Rhazes) medical works. Med Secoli. 1994;6(2):377–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez-Millan C. Practice versus theory: tenth-century case histories from the Islamic Middle East. Soc Hist Med. 2000;13(2):293–306. doi: 10.1093/shm/13.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souayah N, Greenstein JI. Insights into neurologic localization by Rhazes, a medieval Islamic physician. Neurology. 2005;65(1):125–128. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000167603.94026.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCrory PR, Berkovic SF. Concussion: the history of clinical and pathophysiological concepts and misconceptions. Neurology. 2001;57(12):2283–2289. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.12.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daghestani AN. Images in psychiatry: al-Razi (Rhazes), 865–925. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1602. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behbehani AM. Rhazes. The original portrayer of smallpox. JAMA. 1984;252(22):3156–3159. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.22.3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunha BA. Smallpox and measles: historical aspects and clinical differentiation. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2004;18(1):79–100. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(03)00091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radbill SX. Classics from medical literature IV. The first treatise on Pediatrics. Am J Dis Child. 1971;122(5):369–376. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1971.02110050039001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katouzian-Safadi M, Bonmatin JM. The use of honey in the simple and composed drugs at Rhazés. Rev Hist Pharm (Paris) 2003;51(337):29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]