Abstract

BACKGROUND

Disease-specific quality of life instruments assess the impact of chronic rhinosinusitis on patients’ quality of life (QoL). To the extent of our knowledge, there are no Arabic versions of two instruments—the Rhinosinusitis Disability Index (RSDI) and the Chronic Sinusitis Survey (CSS).

OBJECTIVE

Develop an Arabic-validated version of both instruments, thus allowing its use among the Arabic population.

DESIGN

Prospective cross-sectional study for instrument validation.

SETTING

Tertiary university hospital.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This study was conducted between September 2015 and October 2016. We followed the international comprehensive guidelines for translation and cross-cultural adaptation of QoL instruments.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Test-retest reliability, discriminant validity, and responsiveness ability of both the RSDI and CSS Arabic versions.

SAMPLE SIZE

124.

RESULTS

The sample comprised 75 patients diagnosed with chronic rhinosinusitis and 49 healthy control subjects. The Arabic version of both instruments showed high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha: RSDI=0.97, CSS=.88) and the ability to differentiate between diseased and healthy volunteers (P<.0001). The translated versions also detected significant change in response to an intervention (P<.0001).

CONCLUSION

These Arabic validated versions of the RSDI and CSS can be used for both clinical and research purposes.

LIMITATIONS

This study was performed in only one tertiary hospital.

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is defined as a group of disorders characterized by inflammation of the nasal and paranasal sinus mucosa for at least 12 consecutive weeks.1 CRS is a common clinical condition encountered daily in otorhinolaryngology practice and affects an estimated 31 million Americans annually.1 In addition to the significant physical symptoms caused by CRS,1 it exerts a considerable impact on patients’ quality of life (QoL).2 The assessment of the outcomes of CRS treatment regimens should be based on symptom relief reported by patients and supplemented by an assessment of their QoL.2 Currently, there are several disease-specific instruments, which aid in the assessment of QoL and the outcomes of treatment regimens in patients with CRS.3 For example, the Rhinosinusitis Disability Index (RSDI) is a disease-specific QoL instrument that was developed and validated by Benninger and Senior in 19974 to assess both general and disease-specific QoL parameters in CRS patients.5 Because of the RSDI’s simplicity and suitability for measuring disease-specific and general QoL parameters, it is a valuable and practical instrument for use in the evaluation and assessment of CRS treatment outcomes for patients.4 The RSDI consists of 30 items divided between three main domains: physical, functional, and emotional. Responses are provided using a 5-point Likert scale, and scores range from 0 to 150, with higher scores indicating that CRS exerts a greater impact on QoL.5 In addition, the Chronic Sinusitis Survey (CSS), developed by Gliklich and Metson in 1995,6 is considered one of the most frequently used QOL instruments for CRS patients and consists of two main sections. The first section is symptom based and consists of three items, and the second section is medication based and consists of three items. In contrast to other QOL instruments used for CRS patients, items on the CSS pertain to the duration, rather than the severity, of symptoms.6 Furthermore, the brevity of the CSS in comparison to other QOL instruments may increase the likelihood that patients will complete the questionnaire. To our knowledge, no Arabic versions of the RSDI or CSS have been developed. Therefore, the aim of this study was to translate, validate, and adapt the RSDI and CSS for use with Arabic populations.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This prospective cross-sectional study to validate the instrument was conducted at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia between September 2015 and October 2016. Patients were recruited consecutively from a rhinology clinic at King Abdulaziz University Hospital by convenience sampling. The inclusion criteria were the European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Ployps (EPOS) criteria.7 Patients had to be at least 17 years of age and able to understand the objectives of the study. In addition to age less than 17 years, exclusion criteria were an inability to read or write Arabic and being mentally challenged or having difficulty with comprehension. In addition, healthy asymptomatic medical students or relatives who accompanied patients during clinical visits were recruited for the control group. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the ethics committee at the College of Medicine at King Saud University. Informed written consent was obtained from the participants.

Cross-cultural adaptation procedure

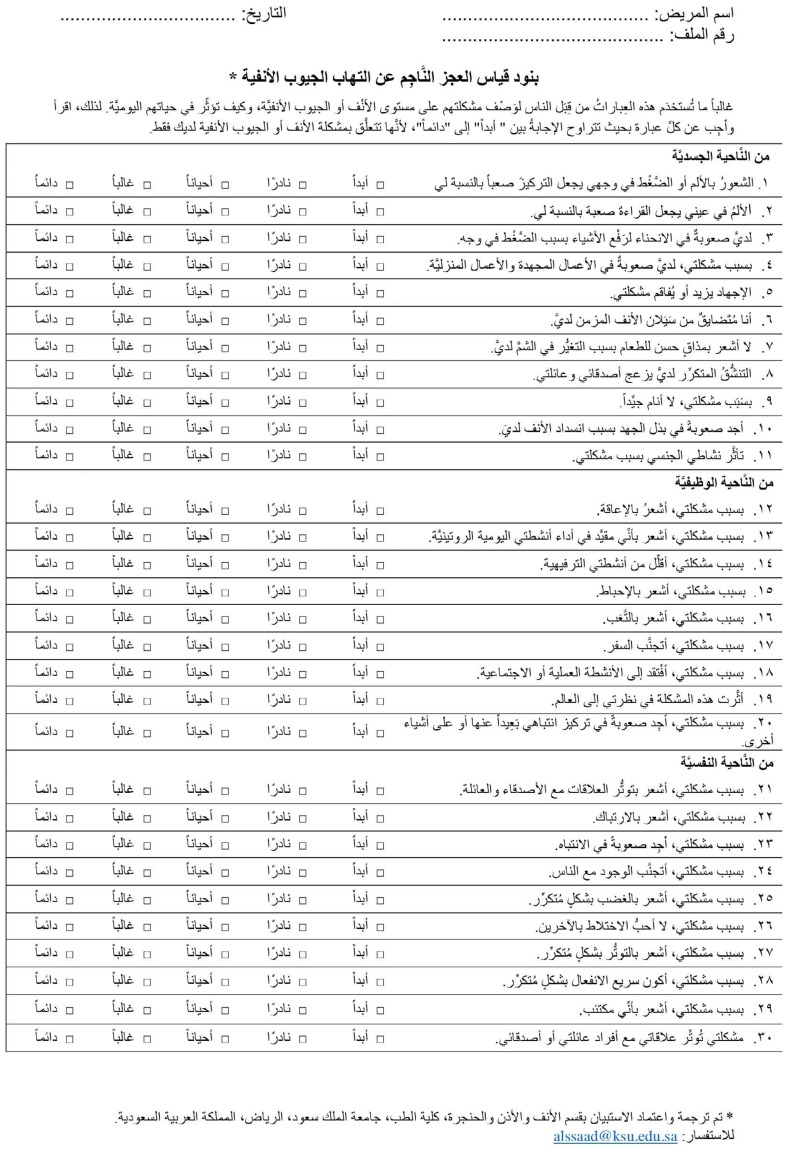

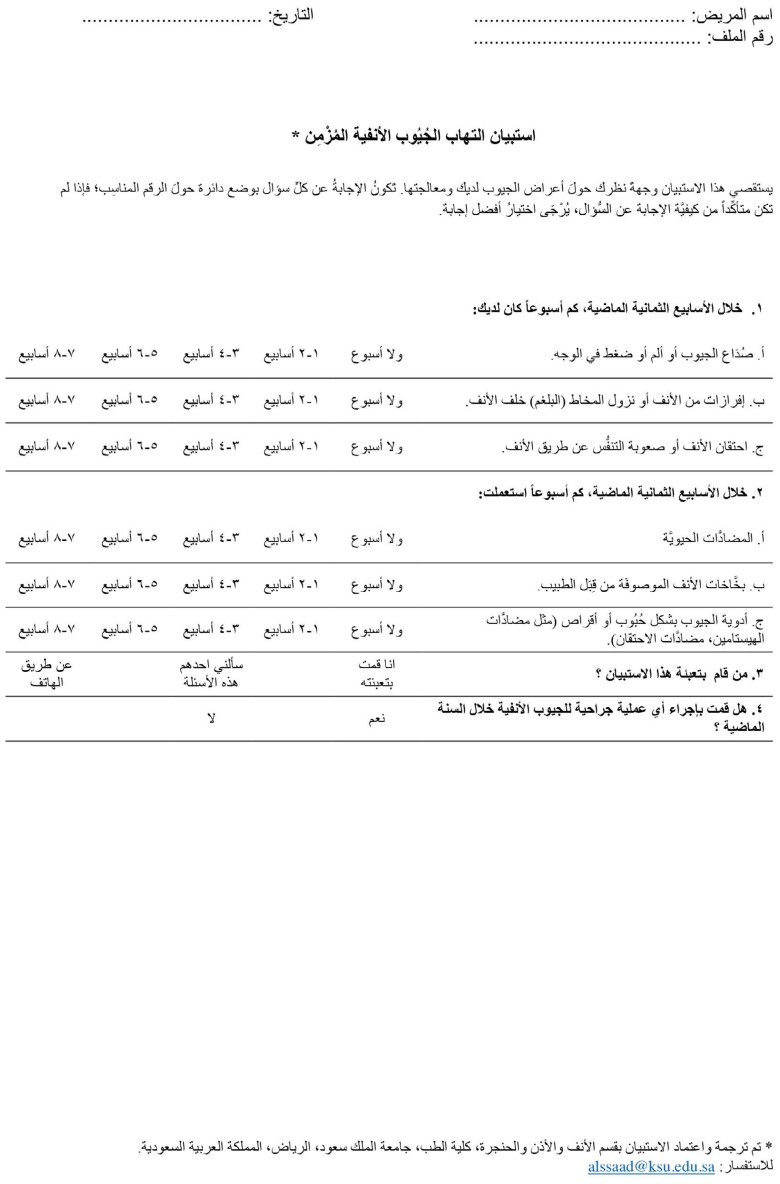

Two independent bilingual professional translators whose native language was Arabic translated the original RSDI and CSS questionnaires from English into Arabic. Thereafter, the two translated versions of the RSDI and CSS were reviewed by two medical professionals who were familiar with the instrument validation process in order to address discrepancies between them and create a single common Arabic version of each questionnaire. Back translation of the Arabic versions of the RSDI and CSS into English was performed by a bilingual native English speaker who spoke Arabic as a second language. These versions were reviewed by the research team and compared with the original versions to ensure that they had the same semantic value. Ten CRS patients were then recruited from the rhinology clinic at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, and a pilot study was conducted to evaluate the Arabic versions of the questionnaires. All subjects participated in the pilot study voluntarily. Each subject completed the Arabic versions of the RSDI and CSS and discussed the clarity of each item with the research team. No modifications were required after the pilot study. The Arabic versions of the RSDI and CSS are shown in Appendices A and B, respectively.

Data were transferred into an Excel spreadsheet using Microsoft Excel 2010 version and analyzed using the Stata (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC). The internal consistency of the translated questionnaires was assessed via Cronbach’s alpha, with a value of .70 or higher considered satisfactory.8,9 Test-retest reliability was performed by asking 20 patients with CRS with no recent changes in treatment or medical status to complete the translated RSDI and CSS twice within a 2-week period. Test-retest reliability was measured using Spearman’s correlation analysis. To determine the extent to which translated questionnaires could differentiate between healthy and unhealthy subjects, we compared mean RSDI and CSS scores between the control group and CRS patients. The responsiveness of the translated questionnaires was assessed by comparing mean pre-intervention scores with those obtained three months subsequent to the intervention using t tests.

RESULTS

The 124 subjects in the study included 75 patients diagnosed with CRS and 49 healthy control subjects. The mean age of overall subjects was 32 years and 52% were male (Table 1). Demographic characteristics did not differ significantly between the control and rhinosinusitis groups. In the rhinosinusitis group, 12, 15, and 48 subjects had allergic fungal sinusitis, CRS without nasal polyposis, and CRS with nasal polyps, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

| Control group (n=49) | Rhinosinusitis group (n=75) | All participants (N=124) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age (mean, SD, range) | 23 (6) (19–52) | 37(13) (17–75) | 32 (12.9) 17–75 |

<.0001 |

| Male (n, %) | 23 (47) | 41 (55) | 64 (52) | .4 |

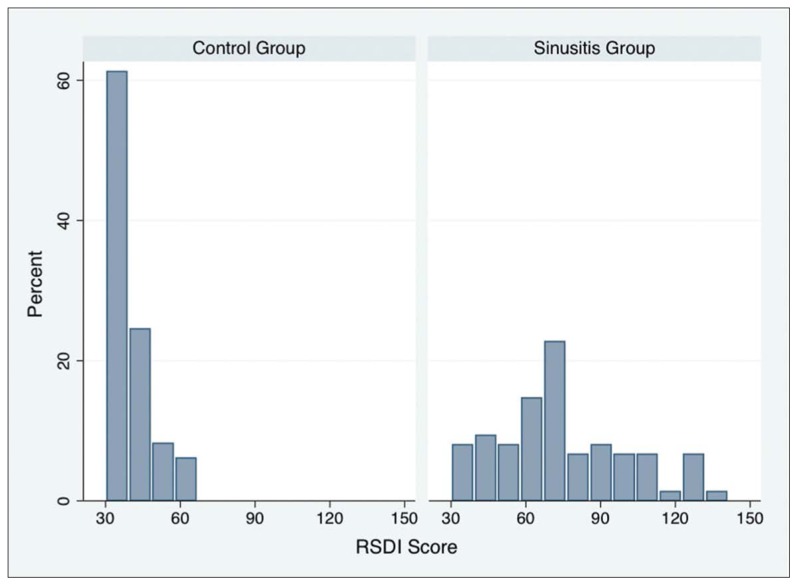

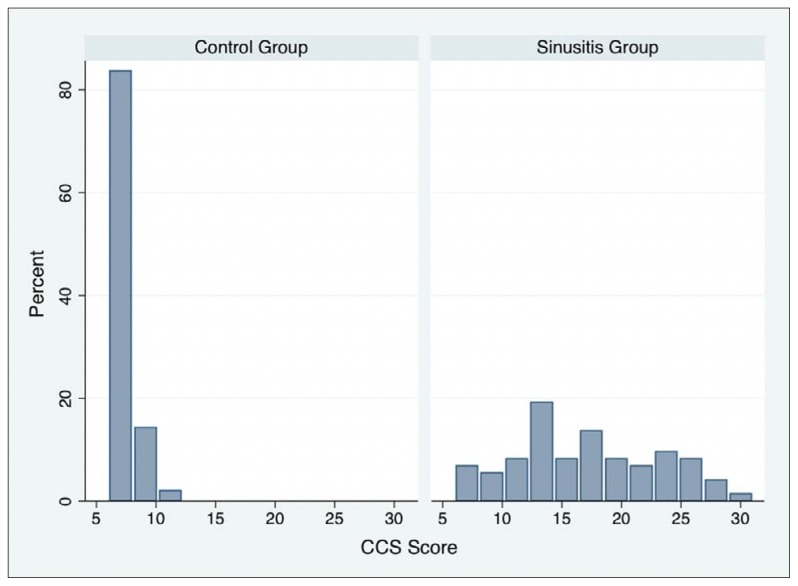

Mean baseline RSDI and CSS scores in the control and rhinosinusitis groups are shown in Table 2. The distribution of scores for the adapted RSDI and CSS questionnaires in the control and rhinosinusitis groups are shown in Figures 1A and 1B, respectively. Mean RSDI and CSS scores in the rhinosinusitis group were significantly higher than those in the control group (P<.001) (Table 2). The results mean that the adapted versions of the RSDI and CSS differentiate between healthy subjects and patients with rhinosinusitis. Cronbach’s alpha for the overall RSDI scale and the physical, functional, and emotional subscales, and the Cronbach’s alpha for CSS and the coefficient for test-retest reliability for the RSDI and CSS are shown in Table 3. Spearman’s correlation coefficient for the relationship between the RSDI and CSS was .69. The internal consistency of the adapted questionnaires was adequate, as Cronbach’s alpha exceeded .70. Items correlation for both RSDI and CSS are shown in Table 4, and Table 5, respectively.

Table 2.

Initial RSDI and CSS scores by group.

| Control group | Rhinosinusitis group | Total | P value (t test two means) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| RSDI | 38.7 (36.0–41.3) | 74.4 (68.5–80.4) | 60.3 (55.5–65.2) | <.0001 |

| CSS | 7.1 (6.7–7.5) | 17.2 (15.9–18.9) | 13.2 (11.9–14.4) | <.0001 |

Mean score and range. RSDI: Rhinosinusitis Disability Index, CSS: Chronic Sinusitis Survey.

Figure 1A.

Distribution of RSDI scores.

Figure 1B.

Distribution of CSS scores.

Table 3.

RSDI and CSS reliability performance.

| RSDI | RSDI subscales | CSS |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.97 | 0.88 |

| Cronbach’s alpha by domain | ||

| Physical | 0.92 | 26.4 (11.32), 1 |

| Functional | 0.93 | 16.5 (8.3), 0.75 |

| Emotional | 0.95 | 17.3 (9.6), 0.86 |

| Test-retest reliability (Spearman) | 0.76 | 0.77 |

RSDI subscales scores are mean (standard deviation) standard error of the mean. Mean scores. RSDI: Rhinosinusitis Disability Index, CSS: Chronic Sinusitis Survey

Table 4.

Rhinosinusitis Disability Index item-test and item-other correlation.

| Items | Item-test correlation | Item-rest correlation | Average inter-item correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Physical | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.87 |

| Functional | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.73 |

| Emotional | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.80 |

Table 5.

Chronic Sinusitis Survey item-test and item-other correlation.

| Items | Item-test correlation | Item-rest correlation | Average inter-item correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Item 1a | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.56 |

| Item 1b | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.52 |

| Item 1c | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.53 |

| Item 2a | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.57 |

| Item 2b | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.57 |

| Item 2c | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.55 |

In the rhinosinusitis group (n=75), 14 patients received non-surgical medical treatment, and 61 underwent surgery. Only 40 patients were available for responsiveness analysis. Mean pre- and post-intervention RSDI and CSS scores in the rhinosinusitis group are shown in Table 6, along with the paired values for sensitivity to change. The mean pre-intervention scores for both questionnaires were significantly higher than the mean post-intervention scores (P<.001).

Table 6.

RSDI and CSS sensitivity to change.

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Change | P value (paired t test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| RSDI | 75.9 (68.4–83.4) | 44.2 (38.6–49.8) | 40 (24.5–38.9) | .0001 |

| CSS | 17.5 (15.5–19.4) | 10.6 (9.3–12.0) | 6.8 (4.8–8.9) | .0001 |

Mean score and range. RSDI: Rhinosinusitis Disability Index, SCC: Chronic Sinusitis Survey. The sample mean-difference=31.7, t statistic=8.9, and the degrees-of-freedom were 39.

DISCUSSION

Although non-CRS-specific instruments that measure general QoL, such as the Short Form 36 (SF-36), can be used to assess the impact of CRS,10 multiple CRS-specific instruments have been developed and have become increasingly popular. Compared to instruments that measure general QoL, CRS-specific instruments are more suitable, as they can be used to evaluate domains that are pertinent to CRS, are not strongly affected by the impact of comorbidity on QoL, and are likely to be sensitive to minor clinical changes.4,11 Furthermore, Quintanilla-Dieck et al3 conducted a systematic review of CRS-specific QoL surveys and found that the CSS was used most commonly, followed by the RSDI and the Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22). Each questionnaire measures different factors and has certain advantages over the others; therefore, they complement each other. In fact, 48% of the studies reviewed used a combination of surveys. In addition, the results of the review showed that the RSDI and SNOT-22 were strongly correlated with each other and weakly correlated with the CSS. This finding suggests that the RSDI and SNOT-22 are similar, and the researchers concluded that a combination of either the RSDI or SNOT-22 and the CSS would provide a more comprehensive evaluation.3

In a previous review of the literature, we found that the RSDI had been adapted and validated for use with Nigerian populations.12 The CSS had been adapted and validated for use with both Chinese and Norwegian populations.13,14 In addition, we described the translation, cultural adaptation, and validation of Arabic versions of the questionnaires. In comparison with the development of a new QoL assessment tool, cross-cultural adaptation of a reliable validated measurement instrument is inexpensive, less laborious, and less time consuming. In addition, it allows for the use of common instruments to compare data from studies examining CRS burden and treatment across different cultures, and it facilitates conducting multi-center and multi-national studies.15 However, cross-cultural adaptation cannot be achieved with mere literal translation. The choice of wording should ensure that the concept (i.e., conceptual equivalence) and meaning (i.e., semantic equivalence) of the original tool is conveyed in the new version in a manner that is relevant to the target culture (i.e., cultural adaptation). Furthermore, the psychometric properties of the new version (i.e., reliability and validity) should be compared to those of the original version in order to verify equal measurement (i.e., measurement equivalence). A translated version that is equivalent to the original questionnaire version with respect to all of the above qualities is said to have “functional equivalence,” which is a term coined by Herdman et al.16

There is no consensus with respect to the most appropriate method for cross-cultural adaptation. However, we followed the steps deemed essential in most guidelines (i.e., forward translations, reconciliation into one version, back translation, expert committee discussions, and cognitive debriefing or pilot testing).17–21 No changes were made following the pilot studies conducted to assess the Arabic versions of the questionnaires. This is likely to have occurred because of the simplicity of the terms used in the tools, which is one of their many favorable qualities.

Reliability is defined as the extent to which an instrument produces consistent and stable results, and it is commonly evaluated by determining the tool’s internal consistency and test-retest reliability. Internal consistency is defined as the extent to which items proposed to measure a certain construct are correlated with each other, and it is measured using Cronbach’s alpha. The Arabic RSDI demonstrated excellent internal consistency (alpha=.97) for the overall scale and all of the subscales, which is similar to that observed for the original English version (alpha=.95) and is superior to that observed for the Nigerian version (alpha=.74 to .93). In addition, Cronbach’s alpha for the adapted version of the overall CSS was .88, which is similar to those observed for the original (.73) and Chinese (.76) versions, and is higher relative to that observed for the Norwegian version (.39).

Test-retest reliability is defined as a measurement tool’s ability to produce stable results over time. The test-retest time intervals in the current study ranged from 4 to 14 days. We believe that this period was sufficiently long to limit recall bias and sufficiently short to prevent clinical changes that can result in the erroneous conclusion that a tool is unstable. As in the assessment of the original instruments, we used Spearman’s correlation coefficients to evaluate the reliability of the Arabic instruments. Spearman’s correlation coefficient for the adapted version of the RSDI was .76; this is comparable to coefficients observed for the original version, which ranged from .60 to .92. In addition, Spearman’s correlation coefficient for the Arabic CSS was .77, which is consistent with those observed for the original (.86) and Chinese (.82) versions.

Validity is defined as the extent to which an instrument measures what it is supposed to measure. We evaluated the ability of the adapted questionnaires to discriminate between CRS patients and healthy subjects using t tests, and they both demonstrated significant discriminant validity (P<.001). Responsiveness, which is another measure of validity, is defined as the ability to detect clinical change over time, usually subsequent to the implementation of an intervention. Paired t test results showed that the Arabic versions of both questionnaires were responsive (P<.001).

We translated the RSDI and CSS from English into formal Arabic. Although this is the official language used in education, writing, and the media in all Arab countries, it differs from spoken Arabic dialects, which vary between countries and regions. Although local dialects (e.g., Lebanese, Tunisian, and Moroccan) have been used in the adaptation of some measurement instruments used in the healthcare field,18,22,23 most Arabic versions of instruments adapted in different countries use formal Arabic.18 Thus, the current study used the formal Arabic language, even though the adapted versions were validated in a Saudi Arabian population, as we believe that the use of formal Arabic allows for broader applicability across Arab nations.

This study was conducted in one hospital, which limits the ability to recruit a large sample size and requires the use of convenience sampling. However, the hospital is a tertiary care center that receives consultations from all regions of Saudi Arabia and the study sample would be representative of each. Also, the study participant numbers are comparable to other questionnaire validation studies.2,12,14 The mean age of the control group was significantly lower than that of the CRS group. However, It is expected that the control group would have a higher tendency to be younger given that CRS burden worsens over time.

In conclusion, this study provided the first Arabic versions of the RSDI and CSS, which demonstrated reliability and validity for use with Arabic-speaking patients with CRS for both clinical and research purposes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by College of Medicine Research Center, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia.

Appendix A. The Arabic version of the RSDI

Appendix B. The Arabic version of the CSS

Footnotes

Funding: None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benninger MS, Ferguson BJ, Hadley JA, Hamilos DL, Jacobs M, Kennedy DW, et al. Adult chronic rhinosinusitis: definitions, diagnosis, epidemiology, and pathophysiology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(3 Suppl):S1–32. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(03)01397-4. Epub 2003/09/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharyya N. Symptom outcomes after endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(3):329–33. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.3.329. Epub 2004/03/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quintanilla-Dieck L, Litvack JR, Mace JC, Smith TL, editors. International forum of allergy & rhinology. Wiley Online Library; 2012. Comparison of disease-specific quality-of-life instruments in the assessment of chronic rhinosinusitis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benninger MS, Senior BA. The development of the Rhinosinusitis Disability Index. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123(11):1175–9. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900110025004. Epub 1997/11/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumann I. Subjective outcomes assessment in chronic rhinosinusitis. Open Otorhinolaryngol J. 2010;4:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gliklich RE, Metson R. Effect of sinus surgery on quality of life. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117(1):12–7. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770199-2. Epub 1997/07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, Bachert C, Alobid I, Baroody F, et al. EPOS 2012: European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2012. A summary for otorhinolaryngologists. Rhinology. 2012;50(1):1–12. doi: 10.4193/Rhino50E2. Epub 2012/04/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ. 1997;314(7080):572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7080.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nunnally JC, 8c Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gliklich RE, Metson R. The health impact of chronic sinusitis in patients seeking otolaryngologic care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113(1):104–9. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989570152-4. Epub 1995/07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopkins C. Patient reported outcome measures in rhinology. Rhinology. 2009;47(1):10–7. Epub 2009/04/23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asoegwu C, Nwawolo C, Okubadejo N. Translation and validation of the Rhinosinusitis Disability Index for use in Nigeria. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2017:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00405-017-4518-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang PC, Tai CJ, Chu CC, Liang SC. Translation and validation assessment of the Chinese version of the chronic sinusitis survey. Chang Gung Med J. 2002;25(1):9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stavem K, Rossberg E, Larsson PG. Reliability, validity and responsiveness of a Norwegian version of the Chronic Sinusitis Survey. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2006;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6815-6-9. Epub 2006/05/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt SM, Alonso J, Bucquet D, Niero M, Wiklund I, McKenna S. Cross-cultural adaptation of health measures. European Group for Health Management and Quality of Life Assessment. Health Policy. 1991;19(1):33–44. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(91)90072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herdman M, Fox-Rushby J, Badia X. ‘Equivalence’ and the translation and adaptation of health-related quality of life questionnaires. Quality of Life Research. 1997;6(3) doi: 10.1023/a:1026410721664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, et al. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8(2):94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al Sayah F, Ishaque S, Lau D, Johnson JA. Health related quality of life measures in Arabic speaking populations: a systematic review on cross-cultural adaptation and measurement properties. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(1):213–29. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0129-3. Epub 2012/02/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein J, Santo RM, Guillemin F. A review of guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires could not bring out a consensus. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2015;68(4):435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2011;17(2):268–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein J, Osborne RH, Elsworth GR, Beaton DE, Guillemin F. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Health Education Impact Questionnaire: experimental study showed expert committee, not back-translation, added value. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2015;68(4):360–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khalaf M, Matar N. Translation and trans-cultural adaptation of the VHI-10 questionnaire: the VHI-10lb. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(8):3139–45. doi: 10.1007/s00405-017-4585-9. Epub 2017/05/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guermazi M, Allouch C, Yahia M, Huissa T, Ghorbel S, Damak J, et al. Translation in Arabic, adaptation and validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use in Tunisia. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2012;55(6):388–403. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]