Abstract

A 59-year-old man with a background of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was diagnosed with a large mixed laryngopyocele that was successfully drained and marsupialized endoscopically using suction diathermy without requiring tracheostomy. Because of the rareness of the case, we performed a systematic review. Of 61 papers published between 1952 and 2015, we reviewed 23 cases written in English that described the number of cases, surgical approaches, resort to tracheostomy, complications, and outcomes. Four cases of laryngopyoceles were managed endoscopically using a cold instrument, microdebrider, or laser. Eighteen cases were operated on via an external approach, and 1 case applied both approaches. One of 4 endoscopic and 10 of 18 external approaches involved tracheostomy. Management using suction diathermy for excision and marsupialization of a laryngopyocele has never been reported and can be recommended as a feasible method due to its widespread availability. In the presence of a large laryngopyocele impeding the airway, tracheostomy may be averted in a controlled setting.

Laryngoceles has the incidence of 1 in 2.5 million people in the United Kingdom annually.1 It is estimated that 8% of laryngoceles get infected and become laryngopyoceles.1,2 Since 1952, only 61 papers on laryngopyoceles have been reported. Gender distribution extracted from 40 papers (53 patients) written in English transcript revealed that 69% and 31% of laryngopyoceles occurred in men and women, respectively. Also, 62% of the cases were between fourth and sixth decades. Moreover, 79%, 17%, and 4% of the laryngopyoceles were of mixed, internal, and external types, respectively. Definitive surgical approach and tracheostomy are performed depending on the type of laryngopyocele, its presentation, and patient’s comorbidities. Since laryngopyoceles are rarely reported, no large case series has been reported to date. In this study, a case of large mixed type of laryngopyocele was discussed, and a systematic review was conducted to present the number of cases, surgical approaches, tracheostomy resort, complications, and outcomes since 1952.

CASE

A 59-year-old gentleman with a background of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease presented with odynophagia for 3 days. He had hoarseness, fever, and pain in the neck region but had no neck swelling or dyspnea at the initial presentation. He was coughing since 2 weeks prior to presentation. A flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscope (FNPLS) showed a swelling over the right arytenoid and false cord. Vocal cords were normal with patent airway.

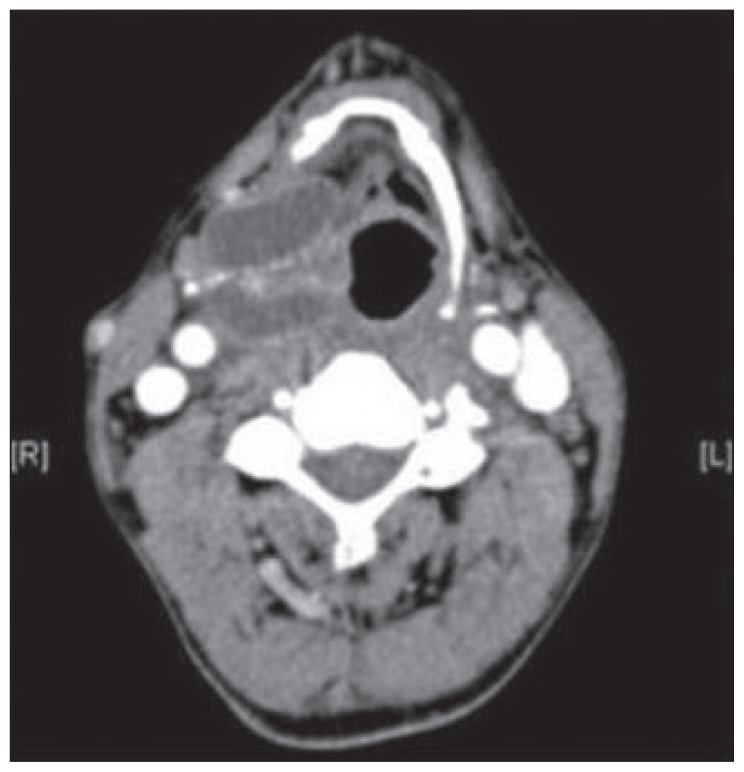

Computer tomography (CT) showed a lobulated low-attenuation cystic lesion in the right paralaryngeal space at the level of the thyroid cartilage with herniation through the thyrohyoid membrane (Figure 1). These findings described a mixed type of laryngopyocele.

Figure 1.

CT scan axonal and coronal view of right laryngopyocele herniating through the thyrohyoid membrane.

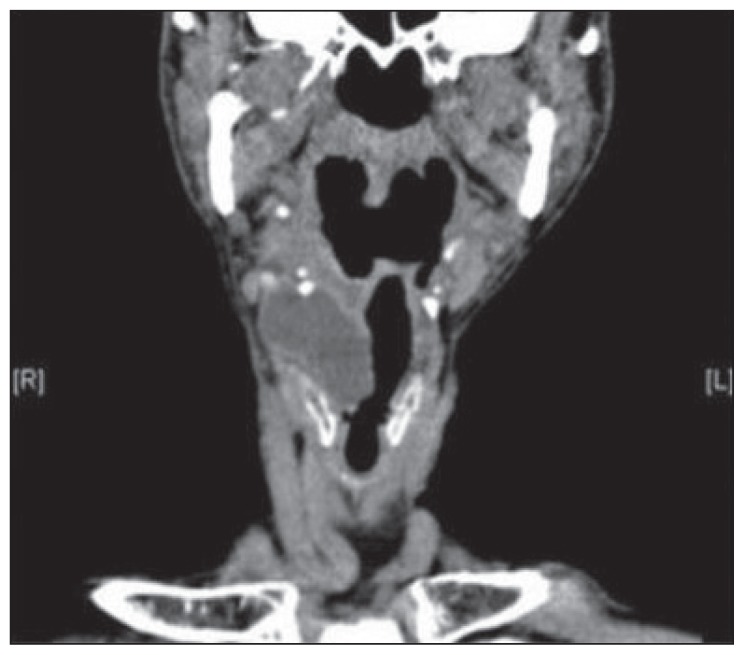

He was conservatively treated with a course of intravenous and oral antibiotics. However, after completion of antibiotic treatment, he complained of worsening odynophagia accompanied by a soft and fluctuant, 3×3 cm2 swelling in the right neck (Figure 2). FNPLS showed that the entire glottis except small chunk of its posterior commissure was obscured by the bulge over the vestibular fold. He was readmitted for intravenous antibiotics therapy. In the ward, he developed stridor, and immediate surgery was planned. He was successfully intubated using a small-sized endotracheal tube. Surgery was done via endoscopic approach using suspension laryngoscopy (Figure 3). The dome of the internal component was ruptured and enlarged using microlaryngeal scissors (Figure 3b). The edge of the incised sac was then held with a microlaryngeal forcep and marsupialized using suction diathermy (Figure 3c). He had no intraoperative complications. He was extubated and had an uneventful postoperative period. Unfortunately, the patient defaulted follow-up and could not be contacted for further assessment.

Figure 2.

Right neck swelling of the laryngopyocele.

Figure 3.

(a) Bulging of internal component obstructing the glottis, (b) rupture of dome during manipulation, (c) pulling out sac using microlaryngeal forcep, and (d) using suction diathermy for marsupialisation.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

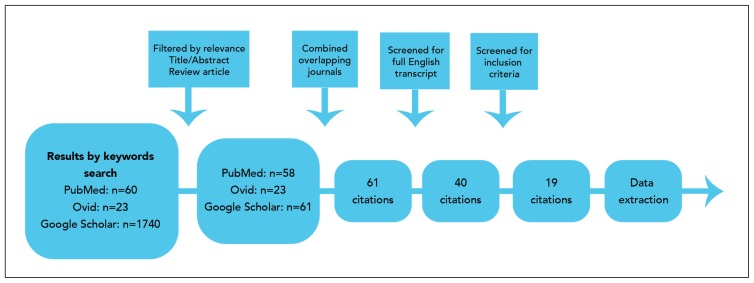

A systematic review via Google Scholar search engine, PubMed, and Ovid databases using key words such as infected laryngocele, Laryngopyocele, and pyolaryngopyocele was conducted. Journals dating from 1952 to January 2015 containing the aforementioned key words were identified and filtered based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Journals included in the review were those that were written in English and covered all of the following details: the number of cases, surgical approaches, tracheostomy resort, complications, and outcomes.

Databases and search engines showed 60, 23, and 1470 results by key word search through PubMed, Ovid, and Google Scholar, respectively (Figure 4). Then, 59, 23, and 61 results were obtained after filtration according to relevance. These results were cross-matched to eliminate any overlapping publications. A total of 40 papers written in English transcript representing 53 patients and their management were noted. Of these results, a review of 19 papers reflecting 23 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria is presented in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Study selection process.

Table 1.

List of publications that fulfil the inclusion criteria describing surgical approach, tracheostomy resort, complications, and outcome.

| No. | Year | Author | No. of cases | Type | Definitive management surgical approach | Tracheostomy performed | Complications | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | 1955 | Chessen J, Luter P | 1 | Mixed | External approach | Yes | None | Uneventful |

| 2 | 1962 | Krekorian EA | 1 | Mixed | External approach | No | None | Uneventful |

| 3 | 1973 | Thawley SE, Bones RC | 2 | Mixed | External approach (both) | Yes (both) | None | Uneventful |

| 4 | 1978 | Kukreja HK | 1 | External | External approach | No | None | Uneventful |

| 5 | 1985 | Weissler MC, Fried MP, Kelly JH | 2 | Mixed | External approach (both) | Yes (both) | None | Uneventful |

| 6 | 1987 | Maharaj D, Fernandes CMC, Pinto AP | 2 | Mixed | Case 1: external approach Case 2: bilateral Laryngopyocele: right (external approach); left (endoscopic approach) |

Yes (both) | Case 1: none Case 2: left side recurred after 6 months and resolved with excision via external approach |

Uneventful after excision via external approach for both cases |

| 7 | 1993 | Ophir D, Babiacki A | 2 of 3 cases * | Mixed | Case 1: external approach Case 2: external approach |

Case 1: Yes Case 2: No |

None | Uneventful |

| 8 | 2001 | Kalish LK Bova R Havas TE |

1 | Mixed | Internal component: endoscopic drainage via cruciate incision External component: external approach |

Yes | None | Uneventful |

| 9 | 2004 | Papila I, Acioglu E, Karaman E | 1 | Internal | Endoscopic approach | No | None | Uneventful |

| 10 | 2005 | Jahendran J, Sani A, Rajan P, et al | 1 | Mixed | External approach | No | None | Uneventful |

| 11 | 2007 | Frederickson KL, D’Angelo Jr AJ | 1 | Internal | Endoscopic excision | No | None | Uneventful |

| 12 | 2008 | Barman D, Pakira B, Majumder P, et al | 1 of 3 cases* | Mixed | External approach | Yes | None | Uneventful |

| 13 | 2010 | Ozcan C, Vayisoglu Y, Guner N | 1 | External | External approach | No | None | Uneventful |

| 14 | 2011 | Fraser L, Pittore B, Frampton S, et al | 1 | Mixed | Endoscopic approach: Marsupialization with microdebrider HPE** returned as carcinoma in situ; completed with laser ventriculotomy | No | None | Uneventful |

| 15 | 2011 | Zenon A, Randhawa PS, O’Flynn P et al | 1 | Internal | Endoscopic approach: deroofing by laryngeal forceps and excision | Yes | None | Uneventful |

| 16 | 2012 | Bakir S, Gul A, Kinis V et al | 1 | Mixed | External approach | No | None | Uneventful |

| 17 | 2013 | Gafton AR, Cohen SM, Eastwood JD | 1 | Mixed | External approach: CT-guided hookwire localization | No | None | Uneventful |

| 18 | 2014 | Luiz-Hernandez J, Tacorente-Perez L, Serdio-Arias J et al | 1 | Mixed | External approach: cervicotomy and block exeresis | Yes | None | Uneventful |

| 19 | 2015 | Karna S, Guiney P, Flatman S | 1 | Mixed | External approach | No | None | Uneventful |

Which fulfils inclusion criteria with all details needed to tabulate;

HPE, histopathological examination.

Eighteen patients had mixed laryngopyoceles. Three patients had internal and 2 patients had external laryngopyoceles. Sixteen of 18 patients with mixed laryngopyoceles were operated via external approach. Ten of these patients underwent tracheostomy. Only one patient with mixed laryngopyocele was operated endoscopically without tracheostomy akin to the present case. All 3 internal laryngopyoceles were removed via endoscopic approach, of which one case underwent tracheostomy. Both external laryngopyoceles were removed via external approach with no tracheostomy performed.

DISCUSSION

Napolean’s surgeon, Dominique Larrey first described laryngocele in muezzins (men who chanted out call to prayer) in 1829.1,2 In 1867, Virchow coined the term “laryngocele,”‘ which is an air-filled abnormal dilatation of the saccule of laryngeal ventricle.3 Saccules are lined with mucosal glands that lubricate the vocal cords. Obstruction of the neck by laryngocele causes stasis of mucous secretion forming laryngomucocele.4 Infected laryngoceles become laryngopyoceles.

Laryngoceles may be congenital or acquired due to long-standing intralaryngeal pressure in occupations such as glassblower, wind instrument player, singer, public speaker, or those with chronic cough akin to the patient in the present case.5 It may also be due to the obstruction of the laryngeal ventricle opening by laryngeal tumors or scarring causing valve effect. Cases of laryngopyoceles associated with laryngeal tumors and intravenous neck injection due to drug abuse have been reported in the published studies.6 Common pathogens include Staphylococcus aureus, hemolytic Streptococcus B, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.7

Internal laryngoceles are purely confined within the larynx. External laryngoceles herniate through the defect caused by the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve at the thyrohyoid membrane.8 Mixed laryngoceles have features of both types. Laryngopyoceles may present with a rapid progressive airway obstruction, neck mass, hoarseness, dysphagia, odynophagia, pain, and fever.

Three mortalities due to airway obstruction secondary to laryngopyoceles have been reported.9–11 Spontaneous rupture of internal or external component with spillage into the airway passages or parapharyngeal spaces may cause mediastinal abscess or jugular vein thrombosis.12 Laryngoscopy may show a mass on the vestibular fold, aryepiglottic fold, or pyriform sinus, which may push the larynx to one side and obscure the glottis. X-rays may show an air fluid level, mass, or trachea displacement. CT scan aids in determining the nature, site of laryngopyocele, and laryngeal structures. 7 Magnetic resonance Imaging has superior soft tissue resolution, but it is more expensive.13

Few cases of regression of laryngopyoceles with antibiotics alone have been reported. Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment. The management of 23 patients who met the inclusion criteria were tabulated and compared. Eighteen and 4 patients were operated via external and endoscopic approaches, respectively. One patient had both methods done. It was found that surgery via external approach was more favored in patients with mixed or external type of laryngopyoceles. This approach varied with the size, type, and location of a lesion. All patients with internal laryngopyocele were operated endoscopically. For mixed type, of 3 of 18 cases that were done endoscopically, 1 case had to be reoperated with external approach due to recurrence, 1 case had cruciate incision done for drainage, and another case was operated using microdebrider.

Endoscopic decompression with marsupiliazation is recommended for internal laryngopyocele. This method avoids surgical morbidity associated with external approach, such as possibility of injury to the superior laryngeal nerves and vessels.2 One case of a mixed laryngopyocele that was treated endoscopically recurred and had to be operated via external approach.14 Otherwise, all of the patients had an uneventful outcome. In the published studies, none of the authors commented on patient’s inability to reach high range following surgery. Endoscopic techniques described include cold instrumentation, microdebrider, and laser surgery. No reports on laryngopyocele managed endoscopically using suction diathermy were available. This study was the first to report on managing a mixed laryngopyocele using this straightforward, feasible method that is readily available in most centers. In addition, it also minimized bleeding during excision and marsupialization.

Further review noted that 10 of 18 patients operated via external approach had tracheostomy done. The indications for 8 and 2 of the patients were respiratory distress and a preliminary measure to secure the airway, respectively. Only 1 case operated endoscopically required tracheostomy that was done to secure the airway during the operation, as the patient had an internal type of laryngopyocele. Ultrasound-guided drainage of laryngopyocele prior to definitive treatment has been reported to be beneficial.15 This step may allow relief of the airway obstruction and averted tracheostomy. The patient in this case study was successfully intubated in a controlled setting despite having a large internal component that obscured the glottis. The evasion of tracheostomy benefited the patient by allowing shorter recuperative time.

CONCLUSION

Laryngopyoceles carry the risk of acute airway obstruction and need to be handled with tact. The published studies showed that external surgical approach is preferred in managing external and mixed laryngopyoceles. The innovative method of endoscopic approach using suction diathermy for the excision and marsupialization of mixed laryngopyoceles is advocated due to its feasibility and availability in most centers. In addition to reducing surgical trauma and risk of injury to the superior laryngeal nerve neurovascular bundle, this endoscopic approach also minimizes bleeding and provides rapid hemostasis to the surgical site. Endotracheal intubation is advocated in a controlled setting as to expedite patient’s recovery along with the minimally invasive method.

Footnotes

SIMILAR CASES PUBLISHED: None specified.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weissler MC, Fried MP, Kelly JH. Laryngopyocele as a cause of airway obstruction. Laryngoscope. 1985;95(11):1348–51. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198511000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fredrickson KL, D’Angelo AJ. Internal Laryngopyocele presenting as acute airway obstruction. Ear, Nose & Throat Journal. 2007;86(2):104–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thawley SE, Bone RC. Laryngopyocele. The Laryngoscope. 1973;83(3):362–368. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jahendran J, Sani A, Rajan P, Mann GS, Appoo B. Intravenous neck injections in a drug abuser resulting in infection of a laryngocele. Asian Journal of Surgery. 2005;28(1):41–44. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60257-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcotullio D, Paduano F, Magliulo G. Laryngopyocele: an atypical case. American Journal of Otolaryngology. 1996;17(5):345–348. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(96)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman J. Three Cases of Infected Laryngocele. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 1952;66(8):409–412. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100047848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan NA, Watson G, Sivayoham E, Willatt DJ. Pyolaryngocoele: Management of an unusualcause of odynophagia and neck swelling. Clinical Medicine: Ear, Nose and Throat. 2008;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frohlich S, O’Sullivan E. Repeated episodes of airway obstruction caused by apyolaryngocele. European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2011;18:179–181. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328344b62f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byard RW, Gilbert JD. Lethal Laryngopyocele. Journal of Forensic Science. 2015;60(2):518–520. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.12676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mays CA. A case of fatal asphyxia due to infection of a ventricular laryngocele. British Journal of Surgery. 1954;41(170):662–3. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004117025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beautyman W, Hatdak GL, Taylor M. Laryngopyocele — Report of a Fatal Case. New England Journal of Medicine. 1959;260:1025–1027. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195905142602007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krekorian EA. Laryngocele and laryngopyocele. Laryngoscope. 1962;72:1297–312. doi: 10.1288/00005537-196210000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lebecque O, Coulier B, Cloots V. Laryngopyocele. JBR-BTR Journal Belge de Radiologie – BelgischTijdschrift voor Radiologi. 2012;95(2):74–76. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maharaj D, Fernandes CM, Pinto AP. Laryngopyocele (a report of two cases) The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 1987;101(8):838–42. doi: 10.1017/s002221510010283x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mace ATM, Ravichandran S, Dewar G, Picozzi GL. Laryngopyocoele: simple management of anacute airway crisis. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 2008;123(2) doi: 10.1017/S0022215108002417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]