Abstract

Coronary fistulas are anomalous shunts from a coronary artery to a cardiac chamber or great vessel, bypassing the myocardial circulation. A 42-year-old Asian man with no significant history of cardiac disease presented with exertional chest discomfort in the form of chest tightness over the precordial area. The patient had no cardiac risk factors, but given the duration and persistence of symptoms, we did a stress echocardiogram. The exercise led to a ‘coronary artery steal phenomenon’ caused by the coronary fistula, which diverted the blood from the left anterior descending artery to the pulmonary artery thereby producing the ischemic symptoms and ventricular tachycardia. Transcatheter coil embolization was unsuccessful, but the fistula was eventually closed surgically. A repeat stress echocardiogram before discharge was completely normal. We emphasize the need to individualize treatment, taking into consideration all factors in a particular patient.

Coronary fistulas are anomalous shunts from a coronary artery to a cardiac chamber or great vessel, bypassing the myocardial circulation. Usually congenital, they can also be acquired due to coronary atherosclerosis, Takayasu arteritis, trauma or other conditions. However, they may present much later in life or be diagnosed incidentally. They may remain asymptomatic or lead to sudden cardiac death. Given this variability in presentation and few cases reported, consensus on management guidelines in asymptomatic cases is lacking and recommendations are based on anecdotal case reports or small case series. We present a case of coronary artery fistula diagnosed in the fifth decade and presenting as ventricular tachycardia.

By presenting this case, we aim to not only highlight an unusual case presentation of a coronary fistula, but also provide a logical approach in deciding the treatment for similar cases. We also hope to emphasize the need to individualize the treatment, taking into consideration all the factors in an individual patient.

CASE

A 42-year-old Asian man with no significant history of cardiac disease presented to the hospital with complaints of atypical chest discomfort associated with palpitations and lightheadedness for 2 hours at his workplace. There was no dyspnea, orthopnea, sweating, nausea/vomiting or loss of consciousness at the time of presentation. On closer questioning the patient reported experiencing exertional chest discomfort in the form of chest tightness over the precordial area for the past several years. On occasion, he also had nausea coincident with the pain, but he had not sought medical attention earlier. On examination, he had a regular pulse rate of 78/min, blood pressure of 130/70 mmHg, and normal jugular venous pressure. Cardiac auscultation revealed a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs, rubs or gallops. Electrocardiogram (EKG) at the time of admission showed sinus rhythm with left axis deviation, left anterior fascicular block and incomplete right bundle branch pattern. However, a comparison could not be made in absence of any prior EKGs. Acute coronary syndrome was ruled out with three sets of negative cardiac enzymes. The patient lacked any cardiac risk factors, but given the duration and persistence of symptoms, further work up was warranted and the decision to do a stress echocardiogram was made.

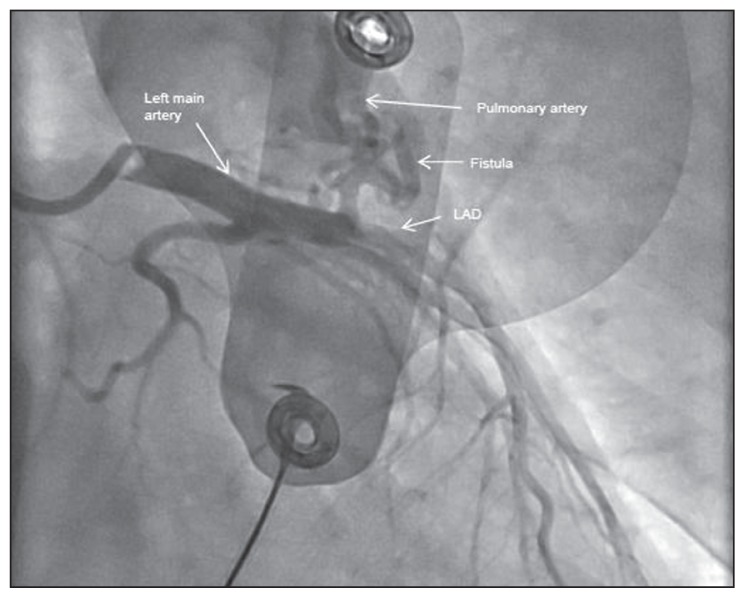

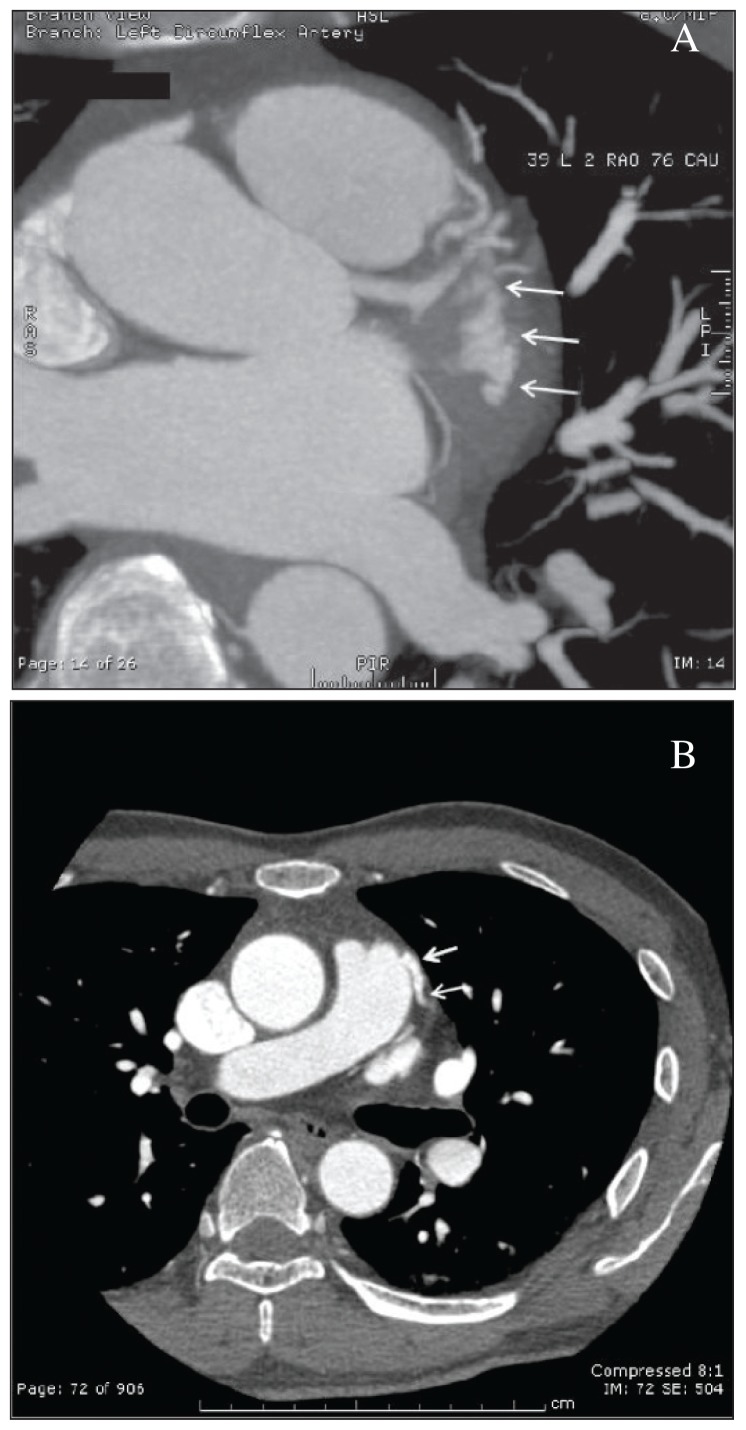

During the stress test, heart rate climbed to 120/min following 7 minutes of exercise. The patient suddenly developed monomorphic ventricular tachycardia, which lasted approximately 8 seconds and resolved spontaneously with termination of exercise. During this episode, the patient developed shortness of breath and palpitations/lightheadedness; however, he did not have a full syncopal episode and he was positioned horizontally. His immediate blood pressure was documented as 120/60 mm Hg. During exercise, he had an adequate heart rate and blood pressure response. This prompted cardiac catheterization (Figure 1) revealing a large fistula from the left anterior descending (LAD) artery to the pulmonary artery, which was subsequently delineated by CT angiogram of the coronaries (Figures 2A and 2B – the arrows point to the fistula). The coronary fistula was presumed congenital in etiology. Cardiac MRI (done to rule out any other pathologies) failed to reveal any scar or asymmetric hypertrophy, which could explain the ventricular tachycardia. Biochemical and hematological investigations including cardiac biomarkers were normal. Combination of presentation with the cardiac catheterisation findings helped us establish a cause–effect relationship between the coronary fistula, ischemic symptoms and ventricular tachycardia. We concluded that exercise led to a ‘coronary artery steal phenomenon’ caused by the coronary fistula, which diverted the blood from the LAD to the pulmonary artery thereby producing the ischemic symptoms and ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 1.

Cardiac catheterisation.

Figure 2.

A) Magnified view, arrows points to the fistula. B) CTA coronary arteries.

Transcatheter coil embolization was attempted but was unsuccessful. The fistula was eventually closed surgically. The patient did well post-operatively and was symptom free. A repeat stress echocardiogram done prior to discharge was completely normal. The patient is being followed up in the outpatient cardiology clinic every three months, and was doing well without recurrence of symptoms.

DISCUSSION

A coronary arterial fistula (CAF) is a connection between one or more of the coronary arteries and a cardiac chamber or great vessel. It is a rare defect with an incidence of about 0.2%–0.3%.1 Associated clinical symptoms are variable and can range from being completely asymptomatic to sudden cardiac death depending, on the size of the communication and resistance of the recipient chamber. Unless very large and hemodynamically significant, it is often asymptomatic in younger patients. Most coronary fistulas are discovered incidentally on coronary angiography, but transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) with a bubble study and CT angiography are needed to identify the origin of coronary fistulas, and for angiographic anatomic assessment of the lesions.2 MRI and multi-detector computed tomography are alternatives to evaluate the anatomy, flow, and function of CAF.3

With increasing age, symptoms begin to appear and the incidence of complication rises. Although rare, coronary artery fistulas should always be considered in a diagnostic cardiology work-up as they can result in cardiac symptoms, and the associated complications can be catastrophic. In a large series of 51 patients with coronary fistulas, angina pectoris occurred in 57% of the cases, often in the absence of an underlying coronary artery disease.4 A phenomenon known as ‘coronary steal’ produces the ischemia, whereby blood flow is directed away from the distal coronary vascular bed. Other potential complications include: infective endocarditis, ischemia or infarction-related arrhythmias, and coronary rupture.

The fistulae can rarely get obstructed due to progressive atherosclerosis causing resolution of symptoms with advancing age. However, an extremely rare case of congenital coronary-pulmonary arterial fistula complicated with a giant coronary artery aneurysm diagnosed at 65 years of age, was recently reported from Copenhagen.5 Bilateral coronary artery to pulmonary artery fistulas is an uncommon anomaly.6,7 A rare case of combination of right coronary and left circumflex coronary arterial fistula draining into the main pulmonary artery was reported from India, where the patient presented with acute chest pain in the emergency, was diagnosed by exercise thallium-201 SPECT myocardial imaging and managed conservatively.6

In asymptomatic patients, the goal is to balance complications anticipated with the presence of a fistula, with those associated with an intervention. The indications for treatment of coronary arterial fistulas include the presence of a large or increasing left-toright shunt, left ventricular volume overload, myocardial ischemia, left ventricular dysfunction, congestive cardiac failure and prevention of endocarditis/endarteritis. The size, site, number, and the shunt related to the fistula helps in deciding the need and choice of intervention. Usually, all but small fistulous connections need to be tackled. The goal is to obliterate the fistula without compromising the coronary flow. The treatment options are surgical or catheter closure. Transcatheter coil embolization requires an experienced operator and interventional specialist with expertise in both coronary arteriography and embolization techniques.

Situations where trancatheter closure is impractical such as large fistulas, multiple openings, associated significant aneurysmal dilatation and others are addressed surgically. The complications of surgical closure include risk of intra-operative myocardial ischemia in 5%, and recurrence.8,9 In the index case, surgical closure was attempted after unsuccessful transcatheter coil embolization.

REFERENCES

- 1.Qureshi SA. Coronary artery fistulas. Orphanet J of rare disease. 2006;1:51–55. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma ES, Yang ZG, Guo YK, Zhang XC, Sun JY, Wang RR. Clinical value of 64-slice CT angiography in detecting coronary artery anomalies. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2008 Nov;39(6):996–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schroeder S, Achenbach S, Bengel F, Burgstahler C, Cademartiri F, De Feyter P, George R, Kaufmann P, Kopp AF, Knutti J, Ropers D, Schuijf J, Tops LF, Bax JJ. Cardiac Computed tomography: indications, applications, limitations and training requirements. EJH. 2008;29:531–556. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rippel RA, Kolvekar S. Coronary artery fistula draining into pulmonary artery and optimal management: a review. Heart Asia. 2013 Jan 25;5(1):16–17. doi: 10.1136/heartasia-2012-010169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frestad D, Helqvist S, Helvind M, Kofoed K. Giant aneurysm in a left coronary artery fistula: diagnostic cardiovascular imaging and treatment considerations. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 May 8;:2013. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-008853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patted SV, Halkati PC, Dixit MD, Patil R. A case of symptomatic double coronary arterypulmonary artery fistulae. Ann Pediatr Card. 2010;3:171–3. doi: 10.4103/0974-2069.74050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vijayvergiya R, Bhadauria PS, Jeevan H, Mittal BR, Grover A. Myocardial ischemia secondary to dual coronary artery fistulas draining into main pulmonary artery. Int J Cardiol. 2010 Apr 15;140(2):e30–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangukia CV. Coronary artery fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012 Jun;93(6):2084–92. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.01.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Testuz A, Roffi M, Bonvini RF. Coronary to pulmonary artery fistulas: an incidental finding with challenging therapeutic options. J Invasive Cardiol. 2011 Jul;23(7):E177–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]