Ovarian hemangiomas are extremely rare tumors, most of which are asymptomatic and of the cavernous type.1 Considering the rich vascular supply of the ovary, the low incidence of ovarian hemangiomas is somewhat surprising. There are about 50 documented cases in the literature. The 12 described in Table 1 were associated with gynecologic tract disease including endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial carcinoma and endometriosis.1–34 Ovarian hemangiomas have been reported in both adults and children and most of the reported cases have been unilateral and small.2,3 Although often an incidental finding at operation, ovarian hemangioma may rarely be associated with gynecologic cancers.4–8 The tumor in our case was an additional and incidental finding in a surgical specimen removed because of a serous papillary carcinoma involving the left tuba and ovary.

Table 1.

Clinico-pathologic features of patients with ovarian hemangioma associated with gynecologic tract disease and coexistent lesions reported in the literature.

| Author | Age | Symptom | Maximum size (cm) | Location | Type | Luteinization | Coexistent lesion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payne et al 1869 | 25 DOD |

Vaginal bleeding | NA | Bilateral | NA | No | Abdominopelvic hemangiomatosis, uterine polyp |

| Kusum et al 1980 | 45 | Irregular vaginal bleeding | 2 | L | NA | No | Cystic hyperplasia of endometrium |

| Alvarez et al 1986 | 68 | Abdominal discomfort | 24 | L | Cavernous | No | Simple endometrial hyperplasia |

| Grant et al 1986 | 59 | Aching breasts, postmenopausal bleeding | 1,5 | R | Mixed | No | Cystic hyperplasia of endometrium |

| Savargaonkar et al 1994 | 69 | Postmenopausal bleeding | NA | NA | NA | Yes | Endometrial hyperplasia, tubal carcinoma |

| Tanaka et al 1994 | 16 | Abdominal mass | 15 | R | Cavernous | No | Turner’s syndrome and bilateral gonadal tumors |

| Carder et al 1995 | 36 | Dysfunctional uterine bleeding | 0,5 | L | Cavernous | Yes | Cystic hyperplasia of endometrium |

| Carder et al 1995 | 62 | Postmenopausal bleeding | 1 | L | NA | Yes | Endometrial carcinoma |

| Rivasi et al 1996 | 46 | Metrorrhagia, anemia | 0,5 | NA | Capillary | No | Endometrial cancer |

| Jurkovic et al 1999 | 32 | NA | NA | L | Cavernous | No | Mucinous cystadenoma |

| Miliara et al 2001 | 71 | Rectosigmoid carcinoma | 0,8 | L | NA | Yes | Rectosigmoid carcinoma, endometriosis |

| Gücer et al 2004 | 70 | Postmenapousal bleeding | 1,5 | L | Mixed | Yes | Endometrial cancer |

| Current case | 65 | Irregular vaginal bleeding and pelvic pain. | 0,5 | L | Capillary | No | Serous papillary carcinoma of the ovary, endometrial polyp |

NA=Not available, DOD=Died of disease.

CASE

A 65-year-old woman was admitted to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Pamukkale University for irregular bleeding and pelvic pain. The medical history of the patient was unremarkable. The serum androgen, estrogen, and progesterone levels were not examined preoperatively, although they were within normal limits postoperatively.

Pelvic examination revealed a normal-sized uterus and palpable abdominopelvic mass. Serum hormonal levels including FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone), LH (luteinizing hormone), TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone), prolactin, estradiol and tumor markers including CA125, CA19-9 and CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) were within normal limits. On ultrasonographic examination, the mass was solid and measured approximately 6 centimeters. The patient underwent laparatomy for a left adnexal mass. Macroscopically a tumor mass 6×4×2.5 centimeter in size was recognized in the adnexal region. The right ovary measured 3×2×1 centimeter, and grossly was unremarkable. The patient underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy, a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, appendectomy, partial omentectomy, and pelvic lymph node dissection. Ascites was not detected at operation. Macroscopic examination of the uterus (125 grams) showed an endometrial polyp measuring 1×1×0.6 centimeters and no leiomyoma was observed.

The specimen was fixed in 10% neutral formalin. The paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Using the avidine-biotin peroxidase complex method, we performed an immunohistochemical analysis for vimentin, CD34, CD31, inhibin, estrogen and progesterone. Immunohistochemically, we found expression of CD34, CD31, vimentin and no expression of inhibin, estrogen and progesterone receptors.

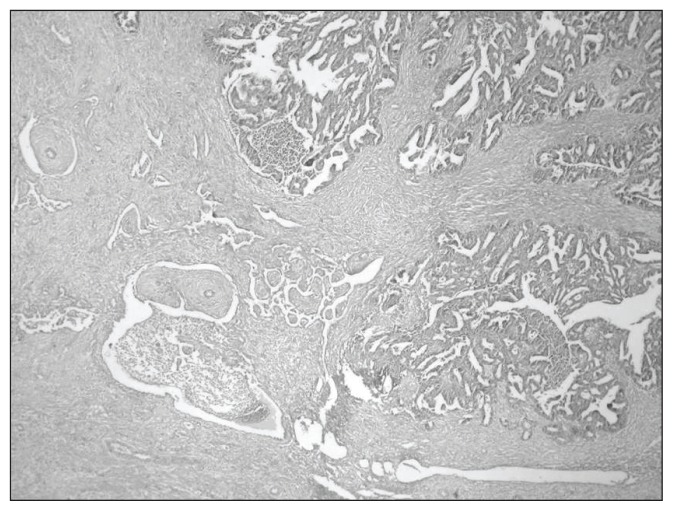

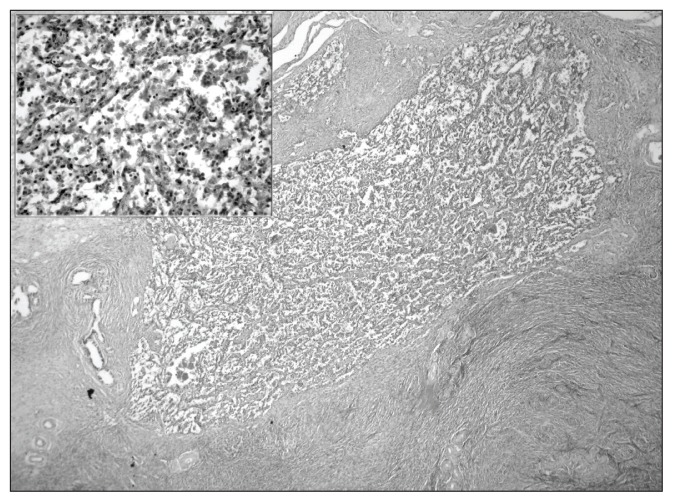

Histologically, the tumor was a serous papillary carcinoma involving the left tuba and ovary (Figure 1). Also, a small capillary hemangioma was incidentally diagnosed, composed of numerous small vascular spaces lined by a single layer of endothelial cells. The hemangioma was clearly distinct from the neoplastic elements. Mitotic activity was not noted and no atypical cells were seen (Figure 2). Neither teratomatous components nor luteinization of the surrounding ovarian stroma was observed, even in the serial sections of the ovary. Microscopic evaluation of the endometrium revealed an endometrial polyp composed of irregularly shaped, crowded, hyperplastic glands.

Figure 1.

Papillary serous carcinoma involving the left tuba-ovary (H&E, ×10, original magnification).

Figure 2.

Ovarian hemangioma composed of numerous small vascular spaces. The inset shows vascular spaces lined by a single layer of endothelial cells with no nuclear atypia and mitosis (H&E, ⋄10, ×40, original magnification).

DISCUSSION

Vascular tumors of the female genital tract, especially hemangiomas of the ovary, are uncommon. The first was reported by Payne in 1869.9 A review of the literature reveals that our case was unique because of the co-existence of the hemangioma with a serous papillary carcinoma of the ovary and an endometrial polyp. In most patients, ovarian hemangiomas are discovered incidentally, and sizes range from 0.3 to 24 centimeter.10,11 The tumor is usually unilateral, but bilateral tumors have been reported.1,12,13 Although they have been found in different parts of the ovaries, the medulla and hilar region are the most common location of the tumor.12

The etiology of ovarian hemangiomas is unknown and controversial. A hemangioma is now considered a part of a mature teratoma or a benign pure ovarian parenchymal neoplasm.14–17 Similarly, some authors have proposed that hemangiomas are either hamartomatous malformations or neoplasms; both origins are probable, and formation may be stimulated by hormonal influences, pregnancy, or infection.18,19 A review of the literature revealed that some ovarian hemangiomas are associated with endometrial hyperplasia and malignancies including endometrial cancer and germ cell tumor.4–6,8,10

In a few reported cases, ovarian hemangioma was associated with stromal luteinization, generalized hemangiomatosis and Ascites, leading to abdominal and pelvic symptoms.1,8,11,14,17,20,21 Miyauchi hypothesized that multicentric abnormal proliferation of endothelial cells is the underlying pathology in generalized hemangiomatosis.13 Luteinization of the ovarian stromal cells was regarded as a reactive phenomenon to the presence of any expansile lesion, including hemangioma. 4 Although our patient did not have stromal luteinization in the affected and contralateral ovary, an endometrial polyp was observed. The pathogenesis of stromal luteinization remains controversial and there is a debate whether these luteinized cells promote the growth of the hemangioma and endometrial polyp or just represent a stromal reaction.20,21 However, it is well known that luteinization may result in androgenic or estrogenic manifestations that could stimulate the development of endometrial hyperplasia, polyp and hemangioma, because the angiotropic effects of estrogens are well established.4,7,8,10,20 It is obvious that the same growth factor may act on both the endometrial polyp and the endothelium, causing the concomitant growth of the two neoplasms. Postmenopausal bleeding and endometrial polyp-like endometrial hyperplasia may manifest hyperestrogenism. However, immunohistochemical studies have failed to reveal any affinity between the endothelium of our case and estrogen and progesterone receptors. Therefore, we suggest that ovarian hemangiomas may occur independently of stimulation by estrogen and progesterone.

Hemangioma must be differentiated from proliferations of dilated blood vessels. Shweta questioned the number of true ovarian hemangiomas because of the difficulty in distinguishing a small hemangioma from dilated hilar vessels. He proposed that a mass of vascular channels, large as well as small, and with minimal amounts of stroma, should form a reasonably circumscribed lesion distinct from the remainder of the ovary and can be regarded as true hemangioma.2 Papillary tufting, significant cytologic atypia or mitotic activity, hemorrhage, and necrosis were not present, differentiating this lesion from angiosarcoma.11

Teratomas are included in differential diagnosis due to the prominent vascular component. In such cases careful sampling is important to exclude the presence of other teratomatous elements before diagnosing the tumor as a pure hemangioma.14,15 We suggest that the tumor described in this report is an ovarian hemangioma arising from ovarian parenchymal cells rather than a teratoma originating from germ cells.

MR imaging is sometimes of value for making a preoperative diagnosis of ovarian hemangioma.17,26 Hemangiomas should be considered when a richly vascularized tumor with prominent blood flow is detected on color Doppler sonography or MRI.21,22

Although some cases may not have been recognized or recorded, to the best of our knowledge this is the first case of a capillary ovarian hemangioma synchronous with a serous papillary carcinoma of the ovary. It should be noted that an ovarian hemangioma can be associated with gynecologic cancers and hemangiomatosis; therefore surgical removal of the involved areas and careful examination of the contralateral ovary and endometrium for a possible malignancy and examination of the abdominopelvic region for hemangiomatosis is essential.

Footnotes

This case was presented as a poster at the XXIII World Congress of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine May 26-60, 2005, Istanbul, Turkey

REFERENCES

- 1.Lawhead RA, Copeland LJ, Edwards CL. Bilateral ovarian hemangiomas associated with diffuse abdominopelvic hemangiomatosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uppal S, Heller DS, Majmudar B. Ovarian hemangioma-report of three cases and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2004;270(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00404-003-0584-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerbie AB, Hirsch MR, Green RR. Vascular tumors of the female genital tract. Obstet Gynecol. 1955;6:499–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gucer F, Ozyilmaz F, Balkanli-Kaplan P, Mulayim N, Aydin O. Ovarian hemangioma presenting with hyperandrogenism and endometrial cancer: a case report. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94(3):821–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivasi F, Philippe E, Walter P, de Marco L, Ludwig L. Ovarian angioma. Report of 3 asymptomatic cases. Ann Pathol. 1996;16(6):439–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka Y, Sasaki Y, Tachibana K, Maesaka H, Imaizumi K, Nishihira H, Nishi T. Gonadal mixed germ cell tumor combined with a large hemangiomatous lesion in a patient with Turner’s syndrome and 45,X/46,X, +mar karyotype. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1994;118(11):1135–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carder PJ, Gouldesbrough DR. Ovarian haemangiomas and stromal luteinization. Histopathology. 1995;26:585–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1995.tb00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savargaonkar PR, Wells S, Graham I, Buckley CH. Ovarian haemangiomas and stromal luteinization. Histopathology. 1994;25(2):185–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1994.tb01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Payne JF. Vascular tumors of the liver, suprarenal capsules and other organs. Trans Path Soc London. 1869;20:203. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarez M, Cerezo L. Ovarian cavernous hemangioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110(1):77–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gehrig PA, Fowler WC, Jr, Lininger RA. Ovarian capillary hemangioma presenting as an adnexal mass with massive ascites and elevated CA-125. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;76(1):130–2. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talerman A. Hemangiomas of the ovary and the uterine cervix. Obstet Gynecol. 1967;30:108–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyauchi J, Mukai M, Yamazaki K, Kiso I, Higashi S, Hori S. Bilateral ovarian hemangiomas associated with diffuse hemangioendotheliomatosis: a case report. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1987;37(8):1347–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1987.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Itoh H, Wada T, Michikata K, Sato Y, Seguchi T, Akiyama Y, Kataoka H. Ovarian teratoma showing a predominant hemangiomatous element with stromal luteinization: report of a case and review of the literature. Pathol Int. 2004;54(4):279–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2004.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prus D, Rosenberg AE, Blumenfeld A, et al. Infantile hemangioendothelioma of the ovary: a monodermal teratoma or a neoplasm of ovarian somatic cells? Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1231–5. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199710000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talerman A. Nonspecific tumors of the ovary. In: Kurman RJ, editor. Blaustein’s Pathology of the Female Genital Tract. 5th edn. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. pp. 1014–44. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaneta Y, Nishino R, Asaoka K, Toyoshima K, Ito K, Kitai H. Ovarian hemangioma presenting as pseudo-Meigs’ syndrome with elevated CA125. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2003;29(3):132–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1341-8076.2003.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shearer JP. Hemangioma of the ovary: Report of a case of a child 3, 5 years of age. Med Ann DC. 1935;2:223. [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiOrio J, Lowe LC. Hemangioma of the ovary in pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1980;24:232–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miliaras D, Papaemmanouil S, Blatzas G. Ovarian capillary hemangioma and stromal luteinization: a case study with hormonal receptor evaluation. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2001;22:369–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamawaki T, Hirai Y, Takeshima N, Hasumi K. Ovarian hemangioma associated with concomitant stromal luteinization and ascites. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;61:438–41. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paladini D, Di Meglio A, Esposito A, Di Meglio G, Riccio A, Di Pietto L, Formicola C. Ultrasonic features of an ovarian cystohemangioma; a case report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1991;40(3):239–40. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaeffer MH, Cancelmo JJ. Cavernous hemangioma of ovary in a girl twelve years of age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1939;38:722–723. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gay RM, Janovski NA. Cavernous hemangioma of the ovary. Gynaecologia. 1969;168:248–257. doi: 10.1159/000302090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caresano G. L’emangioma cavernoso dell’ovaio. Presentazione di un caso e rassegna della bibliografia. Minerva Ginecol. 1977;29:103–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cormio G, Loverro G, Iacobellis M, Mei L, Selvaggi L. Hemangioma of the ovary. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1998;43(5):459–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.M’pemba Loufoua-Lemay AB, Peko JF, Mbongo JA, Mokoko JC, Nzingoula S. Ovarian torsion revealing an ovarian cavernous hemangioma in a child. Arch Pediatr. 2003;10(11):986–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jurkovic I, Dudrikova K, Boor A. Ovarian hemangioma. Cesk Patol. 1999;35(4):133–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mirilas P, Georgiou G, Zevgolis G. Ovarian cavernous hemangioma in an 8-year-old girl. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1999;9(2):116–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1072225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant JW, Millward-Sadler GH. Haemangioma of the ovary with associated endometrial hyperplasia. Case report. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;93(11):1166–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1986.tb08640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loverro G, Cormio G, Perlino E, Vicino M, Cazzolla A, Selvaggi L. Transforming growth factorbeta1 in hemangioma of the ovary. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;46(3):210–3. doi: 10.1159/000010019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kela K, Aurora AL. Haemangioma of the ovary. J Indian Med Assoc. 1980;75(10):201–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiOrio J, Jr, Lowe LC. Hemangioma of the ovary in pregnancy: a case report. J Reprod Med. 1980;24(5):232–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez MA. Hemangioma of the ovary in an 81-year-old woman. South Med J. 1979;72(4):503–4. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197904000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]