Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

Off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (OPCAB) is a popular treatment for patients with ischemic heart disease, especially for high-risk patients. However, whether OPCAB can lead to better clinical outcomes than on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (ONCAB) in patients with enlarged ventricles remains controversial. This prospective randomized study was designed to characterize comparison of early clinical outcome and mid-term follow-up following ONCAB versus OPCAB in patients with triple-vessel disease and enlarged ventricles.

DESIGN AND SETTINGS

Prospective randomized trial of patients treated at The First Affiliated Hospital, China Medical University, over a 3-year period (2007–2010).

METHODS

A total of 102 patients with triple-vessel disease and enlarged ventricles (end-diastolic dimension ≥6.0 cm) were randomized to OPCAB or ONCAB between July 2007 and December 2010. The in-hospital outcomes were analyzed. The study included a mid-term follow-up, with a mean follow-up time of 49.40 (12.88 months).

RESULTS

No significant differences were recorded in the baseline clinical characteristics of ONCAB and OPCAB groups. A statistical difference was found between the two groups at the time of extubation, intensive care unit stay, hospital stay, blood requirements, incidence of intra-aortic balloon pump support, pulmonary complications, stroke, reoperation for bleeding, and inotropic requirements >24 hours (P<.05). The number of anastomoses performed per patient, the incidence of postoperative ventricular arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, new-onset atrial fibrillation, hemodialysis, infective complications, recurrent angina, and percutaneous reintervention were similar between the 2 groups (P>.05). The left ventricular end-diastolic dimension was significantly smaller at 6 months’ follow-up in the 2 groups than it was before operation (<.05). No differences in hospital mortality and mid-term mortality between OPCAB and ONCAB groups were found. During the follow-up, no patient in either group had undergone repeat coronary artery bypass grafting.

CONCLUSION

No differences in early and mid-term mortality were found between OPCAB and ONCAB in patients with triple-vessel disease and enlarged ventricles. However, OPCAB seems to have a beneficial effect on postoperative complications.

Ventricular enlargement is often a result of adaptive response to ischemic cardiac injury and results in the clinical syndrome of congestive heart failure (CHF). It has been reported that after a myocardial infarction (MI), 26% patients develop left ventricular (LV) dilation, leading to a spherically shaped ventricle with diminished contractile function and hearing failure.1 As the normal elliptical shape transforms to a spherical shape, the global systolic function worsens and the prognosis becomes extremely poor, with frequent readmissions and an extremely low survival rate of 5 years. In this case, surgical treatment remains one of the major resources and is expected to cope up with this severe situation. Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) constitutes the basic part in the treatment of coronary artery disease with post-infarction LV dilation.

On-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (ONCAB) is one of the most commonly performed procedure and a well-established treatment for ischemic heart disease. This procedure with cardiac arrest allows the performance of coronary artery anastomosis in a steady, bloodless surgical field.2 Nevertheless, significant morbidity remains mostly because of the whole-body response to the nonphysiologic nature of the on-pump, leading to a propagation of systemic inflammatory response syndrome such as cytokines and complements.3,4 In addition, the use of on-pump and cardiac arrest may result in myocardial dysfunction and, in some patients, myocardial stunning, blending diathesis, neurological deficits, tissue edema, and renal impairment.5–7

In recent years, the standard technique of ONCAB has been challenged by the emerging off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (OPCAB) technique, which avoids the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and cardioplegia. Comparative data regarding the effects of ONCAB versus OPCAB in patients with enlarged ventricles are scarce. Hence, the aim of the present study was to investigate if the off-pump approach would offer early clinical outcome and mid-term survival benefits in patients with triple-vessel disease and enlarged ventricles.

METHODS

Patient Selection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of China Medical University and was in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki. We used the CONSORT checklist (http://www.consort-statement.org/#12a) for design and conduct of this study.

After receiving the written consent from patients with triple-vessel disease and enlarged ventricles (end-diastolic dimension ≥6.0 cm at the tips of the papillary muscles determined by transthoracic echocardiography) (n=102), they participated voluntarily for ONCAB versus OPCAB in our hospital from July 2007 to December 2010. All of the operations were performed by the same surgical team. The patients were divided into 2 groups: In group A (n=51), ONCAB was initially performed with hypothermic CBP and cold blood cardioplegic arrest and in group B (n=51), the patients had initially OPCAB. Among the OPCAB group, conversions to ONCAB occurred in 2 patients (3.9%) because of hemodynamic instability. Among the ONCAB group, 1 patient (1.96%) had his operation converted from on-pump to OPCAB because of heavily calcified aortas. All of the above-mentioned patients were still included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

Exclusion criteria included emergency or urgent operation, combined valve surgery, dyskinetic ventricles (LV aneurysms), history of renal insufficiency (Cr >2 mg/dL), stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) within 1 month, and continuous infusion of inotropics on the day of the operation. Data were collected on the following variables: age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), previous MI, atrial fibrillation, CHF, peripheral artery disease (PAD), history of smoking, dyslipidemia, left main stenosis >50%, previous stroke, previous percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), carotid stenosis >50%, body mass index (BMI), serum creatinine, NYHA (New York Heart Association) class III–IV, ejection fraction (EF), left ventricular end-diastolic dimension (LVEDD), number of anastomoses, ventricular arrhythmia, blood requirements, intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) support, postoperative MI, new-onset AF, pulmonary complications, hemodialysis, stroke, infective complications, reoperation for bleeding, inotropic requirements >24 h, intensive care unit (ICU) stay, postoperative hospital stay, and in-hospital mortality. Recently we made a follow-up on mortality, and the mean follow-up time was 49.40 months (12.88).

Randomization

Before being able to randomize, the surgeon entered a preoperative plan including which coronary arteries were to be grafted, what would be the conduit type, and whether a single, sequential, or y-graft was planned. Having done this the, patient was subsequently randomized to either OPCAB or ONCAB. A randomization table was generated with a computer, and the results were concealed in sealed opaque envelopes. Both the patients and the surgeons were unaware of the result of randomization until the patient was put under general anesthesia and the sealed envelope was opened. Postoperative care team will be blinded according to detailed protocols. Events will, however, be evaluated by an independent committee composed of 2 physicians with relevant medical background in the field of cardiac surgery.

Surgical technique

Median sternotomy was used as the surgical access in all cases. Left internal mammary arteries (LIMA) were harvested in all cases and saphenous veins were used as other conduits. In both OPCAB and ONCAB groups, cardiac displacement was achieved by using a half-folded swab being snared down to the posterior pericardium between the left inferior pulmonary vein and the inferior vena cava. In off-pump group, the target vessels were exposed and controlled with silastic sling. The chosen devices for coronary artery stabilization were the Medtronic Octopus and apical suction positioning device (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minn). The target vessel was then opened and an intracoronary shunt (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minn) was put in to maintain distal perfusion during the performance of anastomosis. Visualization of the operative field was achieved using the carbon dioxide surgical blower system. All proximal anastomoses were performed with the use of side-biting aortic clamp. For the ONCAB group, the standard CPB technique was employed with ascending aortic cannulation and venous drainage via 2-stage venous cannula within the right atrium with complete clamping of the aorta with cardioplegia arrest.

Strategy for revascularization

Surgical revascularization was mainly started from LIMA to the left anterior descending artery (LAD) grafting. Following this, the right coronary system was approached, and finally the circumflex territory was revascularized. In patients with left main disease, LAD and circumflex arteries were always grafted regardless of the degree of stenosis. All other vessels with significant lesions (>70%) were identified preoperatively in the angiogram and selected as a target for revascularization.

Postoperative management

All postoperative cardiac surgery patients were taken to a dedicated cardiac ICU. Each patient was required to meet standard criteria before extubation. Patients were generally transferred from the cardiac ICU if they were considered at risk clinically for decreased oxygen delivery. All patients received intravenous nitroglycerin (0.1–8 μg/[kg.min]) and dobutamine (1–8 μg/[kg.min]) infusions for the first 24 hours. Oral routine medications included daily aspirin and resumption of cholesterol-lowering agents, β-blockers, and angiotension-converting enzyme inhibitors as appropriate.

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

The data were managed and analyzed using SPSS, version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). All continuous variables were shown as mean (standard deviation). Continuous variables were compared by t test. Postoperative complications and some preoperative risk factors were compared using the χ2-test. For those percentages below 5%, Fisher exact test was used. Survival was estimated by using Kaplan-Meyer survival curves. A P value of less than .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Preoperative characteristic

Table 1 shows preoperative characteristics in both patient groups. No significant preoperative differences were observed between the 2 groups with regard to age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, COPD, previous MI, CHF, PAD, history of smoking, dyslipidemia, left main stenosis >50%, previous stroke, previous PCI, carotid stenosis >50%, BMI, serum creatinine, NYHA class III–IV, EF, or LVEDD.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients.

| Variables | ONCAB group (n=51) | OPCAB group (n=51) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Mean age (Y[SD]) | 65.7 (7.6) | 63.7 (8.6) | .227 |

| Sex ratio (M/F) | 38/13 | 40/11 | .641 |

| Hypertension (%) | 35 (68.6%) | 31 (60.9%) | .407 |

| Diabetes (%) | 21 (41.2%) | 25 (49%) | .426 |

| COPD (%) | 5 (9.8%) | 8 (15.7%) | .373 |

| Previous MI (%) | 39 (76.5%) | 36 (70.6%) | .501 |

| CHF (%) | 34 (66.7%) | 31 (60.8%) | .537 |

| Peripheral artery disease (%) | 6 (11.8%) | 8 (15.7%) | .565 |

| History of smoking (%) | 27 (52.9%) | 31 (60.8%) | .424 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 35 (68.6%) | 36 (70.6%) | .830 |

| Left main stenosis >50% | 16 (31.4%) | 14 (27.5%) | .664 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 18 (35.3%) | 17 (33.3%) | .835 |

| Previous PCI (%) | 8 (15.6%) | 9 (17.6%) | .790 |

| Ejection fraction (mean [SD]) | 41.9 (8.8) | 43.39±9.53 | .771 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.65 (4.8) | 24.63±5.35 | .291 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.05±0.39 | .340 |

| NYHA class III–IV (%) | 20 (39.2%) | 21 (41.2%) | .840 |

| AF (%) | 5 (9.8%) | 6 (11.8%) | .750 |

| LVEDD (cm) | 6.48±0.37 | 6.5 (0.4) | .809 |

| Carotid stenosis >50% | 21 (41.2%) | 18 (35.3%) | .541 |

ONCAB: On-pump coronary artery bypass grafting, OPCAB: off-pump coronary artery bypass, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, MI: myocardia infarction, CHF: congestive heart failure, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention, BMI: body mass index, AF: atrial fibrillation, LVEDD: LV end-diastolic dimension, SD: standard deviation, IABP: aortic balloon pump, NYHA: New York Heart Association.

Perioperative data

Table 2 shows perioperative data in the 2 groups. The 2 patients of the OPCAB group required conversion to on-pump technique intra-operatively because of hemodynamic instability. No significant difference was found between the 2 groups in the postoperative new-onset AF. Postoperative ventricular arrhythmia, hemodialysis, infective complications, and acute myocardial infarction (MI) (acute MI was defined as CK-MB release >80 IU/mL regardless of concomitant changes in electrocardiogram or impaired hemodynamics) were lower, but the difference was not statistically significant in the OPCAB group. The number of anastomoses was more in the ONCAB group (3.14 [0.53] vs 3.02 [0.55]), but the difference was not statistically significan. In contrast, the blood requirement was significantly greater among the ONCAB group (52.9% vs 21.6%, P=.001). In the ONCAB group, 18 patients (35.3%) had IABP support versus 6 patients (11.8%) in the OPCAB group (P=.005). Inotropic requirements >24 hours was higher in the ONCAB group than in the OPCAB group (49.0% vs 21.6%, P=.004). The frequency of pulmonary complications was higher in the ONCAB group than in the OPCAB group (21.6% vs 5.9%, P=.021). None of the OPCAB patients had a stroke (stroke was defined as new acute focal neurologic deficit with signs and symptoms lasting greater than 24 hours, and neurologic events included TIA and stroke), versus 5 (9.8%) patients in the ONCAB group (P=.022). Reoperation for bleeding was higher in the ONCAB group than in the OPCAB group (7.8% vs 0%, P=.041). Analysis showed significant benefits from OPCAB for the time to extubation (10.22 [14.70] hours vs 21.94 [30.55] hours, P=.015), ICU stay (43.35 [32.83] hours vs 46.71 [49.99] hours, P=.003), and hospital stay (11.53 [4.86] days vs 15.27 [5.81] days, P=.001). In-hospital mortality was lower, but the difference was not statistically significant in the OPCAB group (7.8% vs 11.8%, P=.505).

Table 2.

Perioperative data.

| Variables | ONCAB group (n=51) | OPCAB group (n=51) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Number of anastomoses/patient | 3.1 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.6) | .273 |

| Ventricular arrhythmia (%) | 15 (29.4%) | 8 (15.7%) | .097 |

| Blood requirements (%) | 27 (52.9%) | 11 (21.6%) | .001 |

| IABP support (%) | 18 (35.3%) | 6 (11.8%) | .005 |

| Postoperative MI (%) | 8 (15.7%) | 4 (7.8%) | .219 |

| New-onset AF (%) | 7 (13.7%) | 8 (15.7%) | .780 |

| Pulmonary complications (%) | 11 (21.6%) | 3 (5.9%) | .021 |

| Hemodialysis (%) | 6 (11.8%) | 3 (5.9%) | .295 |

| Stroke (%) | 5 (9.8%) | 0 (0%) | .022 |

| Infective complications (%) | 6 (11.8%) | 2 (3.9%) | .141 |

| Inotropic requirements >24 h (%) | 25 (49.0%) | 11 (21.6%) | .004 |

| Reoperation for bleeding (%) | 4 (7.8%) | 0 (0%) | .041 |

| Time to extubation (h) | 21.9 (30.6) | 10.2 (14.7) | .015 |

| ICU stay (h) | 46.7 (50.0) | 43.4 (32.8) | .003 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 15.3 (5.8) | 11.5 (4.9) | .001 |

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 6 (11.8%) | 4 (7.8%) | .505 |

ONCAB: On-pump coronary artery bypass grafting, OPCAB: off-pump coronary artery bypass, IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump, MI: myocardial infarction, AF: atrial fibrillation, ICU: intensive care unit, LVEDD: LV end-diastolic dimension.

The follow-up data

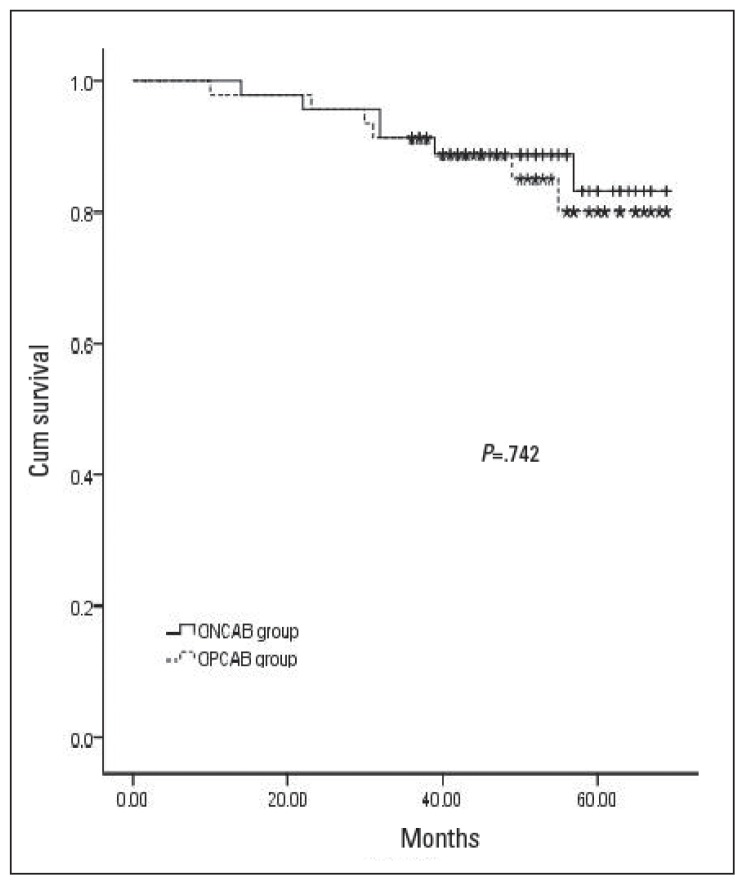

Table 3 shows the follow-up data in the 2 groups. No patient emigrated during the study period or was lost to follow-up. All survivors had follow-up investigation from 10 months to 69 months, with the mean follow-up time of 49.40 (12.88 months). LVEDD was significantly smaller at 6 months’ follow-up than it was before operation in the ONCAB group (5.96 [0.31 cm] vs 6.43 [0.33 cm], P=.000) and in the OPCAB group (6.08 [0.52 cm] vs 6.46 [0.39 cm], P=.000). However, there were no significant differences at 6 months’ follow-up between the 2 groups (P=.211). At the follow-up, recurrent angina had occurred in 4 of 45 (8.9%) OPCAB patients and 2 of 47 (4.3%) ONCAB patients (P=.368). Percutaneous reintervention had been performed at the discretion of blinded local cardiologists in 1 of 47 (2.1%) OPCAB patients and 1 of 45 (2.2%) ONCAB patients (P=.975). No patient in either group had undergone repeat CABG. The mortality showed that 7 patients (14.9%) had died in the OPCAB group versus 6 patients (13.3%) in the ONCAB group (P=.742). Kaplan-Meyer survival curves for the 2 groups are reported in Figure 1.

Table 3.

The follow-up data.

| Variables | ONCAB group (n=45) | OPCAB group (n=47) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| LVEDD at six months follow-up (cm) | 6.0 (0.3) | 6.1 (0.5) | .211 |

| Percutaneous reintervention (%) | 1 (2.2%) | 1 (2.1%) | .975 |

| Mortality during follow-up (%) | 6 (13.3%) | 7 (14.9%) | .742 |

| Mean follow-up time (M) | 49.5 (12.8) | 49.3 (13.1) | .937 |

ONCAB: On-pump coronary artery bypass grafting, OPCAB: off-pump coronary artery bypass, SD: standard deviation, LVEDD: left ventricular end-diastolic dimension.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meyer survival curves for OPCAB and ONCAB groups.

DISCUSSION

Ventricular enlargement is often the result of adaptive response to ischemic cardiac injury and results in the clinical syndrome of CHF. Despite medical advances, the number of deaths attributable to CHF continues to rise.8 Although the gold standard therapy for severe CHF refractory to medical management is heart transplantation, limitation of donors, cost, and post-transplant morbidities prevent its widespread applicability. For this reason, CABG has been the most widely applied technique.9

Previous studies10 have suggested that patients who have ischemic cardiomyopathy and a preoperative LVEDD of greater than 70 mm are poor candidates for CABG. Some authors have demonstrated that patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and LV enlargement who underwent CABG did worse than those with small ventricles.11 Recent studies have also shown that surgical ventricular restoration (SVR) improves regional myocardial performance in nonischemic areas remote from the scar, improves EF, and reduces ventricular dys-synchrony. 12–14 However, whether the surgically induced ventricular geometric changes will lead to better clinical outcomes remains controversial. Some authors did not reveal significant difference between the results of the CABG alone and combined with SVR in patients with ischemic heart failure.15,16 In March 2009, the results of the Hypothesis 2 arm were presented at American College of Cardiology meeting and published a month later in the New England Journal of Medicine.17 The investigators concluded that “adding surgical ventricular reconstruction to CABG reduced the left ventricular volume, as compared with CABG alone. However, this anatomical change was not associated with a greater improvement in symptoms or excise tolerance or with a reduction in the rate of death or hospitalization for cardiac causes.” As to our own experience, SVR was performed only for classic LV aneurysm of ischemic cardiomyopathy in our hospital. Our study suggested that CABG can be performed with reasonably low operative mortality and mid-term follow-up outcomes in patients with triple-vessel disease and enlarged ventricles.

The dilatation of ventricle induces LV geometric changes that lead to mitral valve dysfunction (displacement of papillary muscles, tethering of leaflets, and annular dilatation).18,19 There is little doubt that mitral repair or replacement should be performed concomitantly with CABG when significant mitral regurgitation (MR) exists. In our hospital the policy is to repair the mitral valve when MR is more than moderate or the mitral annulus is 36 mm in the presence of marked dilatation of the ventricle. To ensure that the mitral valve operations were not confounding our results, we removed all individuals undergoing either mitral valve repair or replacement at the time of their bypass operation.

Revascularization using CABG still remains the benchmark treatment today for patients with triple-vessel disease and high operative risk score. Nevertheless, today the global percentage of surgeons using less invasive OPCAB procedures is estimated only at 20%, although it is expected that the procedure could be beneficial for high-risk patients.20 The effect of reducing the injury (related to the use of cardiopulmonary bypass) has never led to significantly lower postoperative morbidity and mortality rates in the OPCAB group when low-risk groups of patients were compared.21 The largest randomized study (the ROOBY trial) comparing the results of conventional and OPCAB showed that OPCAB is not superior to ONCAB.22 However, the cited research remains controversial because more than 50% of procedures were performed by surgeons with small–to-moderate experience. Another limitation of this study was the high conversion rate from OPCAB to ONCAB. This research reminds us once again how important the training process is to achieve proficiency in technically demanding procedures. The patients with triple-vessel disease and enlarged ventricles definitely belong to the high-risk group, and our study confirms OPCAB seems to have a beneficial effect on morbidity.

However, there is much criticism about the off-pump method because of the potential for incomplete revascularization and the worsening quality of vascular anastomosis performed on the beating heart. Findings about the inferior patency rate of conduits performed off-pump were reported from numerous randomized studies comparing angiographic results of ONCAB and OPCAB, especially when the grafts were made of great saphenous vein.23 An observed trend toward a higher mean number of coronary anastomoses and 1-year rates of graft patency performed in the ONCAB group than in the OPCAB group was reported.22 However a randomized trial concluded that OPCAB and ONCAB were associated with similar early and late graft patency, incidence of recurrent or residual myocardial ischemia, need for re-intervention, and long-term survival.24 Although we observed a slightly fewer anastomoses in the off-pump group as well, it did not translate into a worse survival. Similar survival among our OPCAB patients compared with ONCAB suggests that the extra grafts may not be crucial such as grafts to the diagonal branches of the LAD coronary artery and the tenuous circumflex branch, which may carry a relatively small proportion of myocardial flow. The present study was designed to analyze recurrent angina and not graft patency, so no routine angiographic follow-up is available. This controversy about graft patency, however, remains to be resolved by larger, prospectively randomized trials with long-term follow-up angiographic studies.

In high-risk patient cohorts, the benefits of avoiding CPB and aortic manipulation may be more apparent than in lower risk patients. However, one of the main limitations of OPCAB is the occasional need to convert to on-pump. This occurrence is associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality and postoperative morbidity, and negates any potential benefit of OPCAB. Several authors have, however, reported that hemodynamic collapse and emergent conversion to CPB from OPCAB is associated with poor prognosis.25 In our study, as previously reported, 2 patients died in hospital due to the conversion to ONCAB. Certain maneuvers may avoid some of the potentially deleterious hemodynamic consequences during OPCAB that may lead to conversion. At our institution, certain intra-operative techniques can facilitate OPCAB even during challenging cases. The sequence of grafting (LITA to LAD anastomosis prior to other anastomoses may maintain cardiac performance), timing of proximal anastomoses, grafting collateralized vessels first, use of cardiac stabilizing device in combination with an apical suction positioning device, use of intracoronary shunts, trials of temporary regional ischemia before arteriotomy, judicious use of inotropic agents, and minimizing compression during cardiac positioning can all be used to result in a successful OPCAB procedure.

Although the short-term results of our trial are encouraging, it is important to recognize that we stipulated a high level of expertise for participating surgeons. Therefore, surgeons, particularly trainees or inexperienced surgeons, who are early in the learning curve, may choose to tailor their surgical approach according to the expected technical difficulties and potential benefits for each patient. In our clinical routine, we complete more than 50% of cases off-pump. The entire cardiac surgical staff is therefore highly familiar with this technique. Less experienced centers and centers still in the process of establishing off-pump programs should start out with standard patients having good target vessels. Subsequently, the experience thus gained can be transferred to high-risk cases, aiming for excellent results in that challenging population.

Study limitations

The single-surgeon, single-center nature of the trial design also limits the generalizability of surgical outcomes, as both the center and the surgeon have a greater than average experience and interest in OPCAB. The duration of stroke and postoperative MI were lower in our institute than in other institutes. Moreover, the small population of the current study may also induce some bias, which may result in higher incidence of stroke and postoperative MI. IABP was used more actively in the current study in our center as the larger left ventricle and the lower EF of the patients. IABP was also used under the condition when patients were supported by moderate dosage of inotropic agents. So the use of IABP was higher in our institute than in other institutes. The majority of the hospital death occurred if patients had the EF level less than 35% and the left ventricle larger than 70 mm. The higher number of such patients with high risks in the current cohort may contribute to the high mortality rate. We were not able to study the graft patency in either group, a crucial outcome when comparing off-pump with on-pump revascularization. The present report does not include data on long-term morbidity and mortality. However, further follow-up and angiographic control of graft patency are planned and are in the process of being performed.

In conclusion, OPCAB compared with ONCAB reduced early morbidities in patients with triple-vessel disease and enlarged ventricles. However, no differences in terms of early and mid-term mortality were found between OPCAB and ONCAB. A large, randomized clinical trial warranted to confirm the influence of the off-pump technique in patients with triple-vessel disease and enlarged ventricles.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matter C, Mandinov L, Kaufmann P, Nagel E, Boesiger P, Hess OM. Function of the residual myocardium after infarct and prognostic significance. Z Kardiol. 1997;86:684–90. doi: 10.1007/s003920050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shennib H, Allan GL, Akin J. Safe and effective method of stabilization for coronary bypass grafting on the beating heart. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:988–92. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clausell N, Polancsyk C, Savaris N. Cytokines and troponin-I in cardiac dysfunction after coronary artery grafting with cardiopulmonary bypass. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2001;77:114–9. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2001000800002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler J, Rocker GM, Westlably S. Inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;55:552–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)91048-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu L, Gu T, Shi E, Jiang C. Surgery for chronic total occlusion of the left main coronary artery. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:156–61. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2012.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckberg GD. Update on current techniques of myocardial protection. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:805–14. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahimtoola SH. From coronary artery disease to heart failure: role of the hibernating myocardium. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:16E–22E. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80443-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure): developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2005;112:e154–235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.167586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Hellermann-Homan JP, Killian J, Yawn BP, et al. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community based population. JAMA. 2004;292:344–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louie HW, Laks H, Milgalter E, Drinkwater DC, Jr, Hamilton MA, Brunken RC, et al. Ischemic cardiomyopathy. Criteria for coronary revascularization and cardiac transplantation. Circulation. 1991;84(5 Suppl):III290–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamaguchi A, Ino T, Adachi H, Murata S, Kamio H, Okada M, et al. Left ventricular volume predicts postoperative course in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:434–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Athanasuleas CL, Buckberg GD, Stanley AW, Siler W, Dor V, Di Donato M, et al. Surgical ventricular restoration in the treatment of congestive heart failure due to post-infarction ventricular dilation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1439–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Donato M, Sabatier M, Montiglio F, Maioli M, Toso A, Fantini F, et al. Outcome of left ventricular aneurysmectomy with patch repair in patients with severely depressed pump function. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:557–61. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dor V, Sabatier M, Di Donato M, Montiglio F, Toso A, Maioli M. Efficacy of endoventricular patch plasty in large postinfarction akinetic scar and severe left ventricular dysfunction: comparison with a series of large dyskinetic scar. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;116:50–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Appoo J, Norris C, Merali S, Graham MM, Koshal A, Knudtson ML, et al. Long-term outcome of isolated coronary artery bypass surgery in patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2004;110(11 Suppl 1):II13–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138345.69540.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Neill J, Starling R, McCarthy P, Albert NM, Lytle BW, Navia J, et al. The impact of left ventricular reconstruction on survival in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30:753–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones RH, Velazquez EJ, Michler RE, Sopko G, Oh JK, O’Connor CM, et al. Coronary bypass surgery with or without surgical ventricular reconstruction. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1705–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yiu SF, Enriquez-Sarano M, Tribouilloy C, Seward JB, Tajik AJ. Determinants of the degree of functional mitral regurgitation in patients with systolic left ventricular dysfunction: a quantitative clinical study. Circulation. 2000;102:1400–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.12.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menicanti L, Di Donato M, Frigiola A, Buckberg G, Santambrogio C, Ranucci M, et al. Ischemic mitral regurgitation: intraventricular papillary muscle imbrication without mitral ring during left ventricular restoration. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:1041–50. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.121677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemma MG, Coscioni E, Tritto FP, Centofanti P, Fondacone C, Salica A, et al. On-pump versus off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery in high-risk patients: operative results of a prospective randomized trial (on-off study) J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:625–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng ZZ, Shi J, Zhao XW, Xu ZF. Meta-analysis of on-pump and off-pump coronary artery revascularization. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:757–65. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shroyer AL, Grover FL, Hattler B, Collins JF, McDonald GO, Kozora E, et al. On-pump versus off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1827–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takagi H, Matsui M, Umemoto T. Lower graft patency after off-pump than on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: an updated meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:e45–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puskas JD, Williams WH, O’Donnell R, Patterson RE, Sigman SR, Smith AS, et al. Off-pump and on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting are associated with similar graft patency, myocardial ischemia, and freedom from reintervention: long-term follow-up of a randomized trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:1836–43. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel NC, Patel NU, Loulmet DF, McCabe JC, Subramanian VA. Emergency conversion to cardiopulmonary bypass during attempted off-pump revascularization results in increased morbidity and mortality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:655–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]