Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

Saudi Arabia has implemented strategies for the eradication of malaria. However, influx of people from countries endemic for malaria for either employment or Hajj makes the country highly susceptible to malaria importation. The Makkah region is known to host millions of immigrants yearly and has a surveillance system to monitor the incidence of malaria. The objective of this study was to examine malaria patients, nationality, and parasite type in Makkah region between 2008 and 2011.

DESIGN AND SETTINGS

A retrospective analysis of all reported malaria cases from 19 sentinel sites in Makkah region, Saudi Arabia, for the period between 2008 and 2011.

METHODS

Analysis of surveillance data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago).

RESULTS

A total of 318 malaria cases were reported in these 4 years, of which only 3.6% of cases were less than 10 years of age, including 2 cases below 5 years. Non-Saudis were 95% and Pakistanis, Nigerians, and Indians accounted for 62.0%. Plasmodium falciparum (67%). Plasmodium vivax (32%) and Plasmodium ovale (1.6%) were the notable parasites.

CONCLUSION

The low frequency of malaria in Makkah suggests that Saudi Arabia is in the consolidation phase of malaria eradication. The absence of local transmission of malaria is indicated by low frequency of malaria in children less than 5 years of age, and high frequency of malaria in non-Saudis is evidence of malaria importation. Health workers attending to foreigners with febrile illness from Pakistan, Nigeria, and India should consider malaria as their first line of suspicion.

Malaria is one of the 3 top most communicable diseases of public health concern in the world.1 It is endemic in the tropical region of Africa, and part of Asia and Americas. Current reports showed an estimated 216 million episodes of malaria in 2010, with a wide uncertainty interval (5th–95th percentiles) from 149 million to 274 million cases. Approximately, 86% of malaria deaths globally were of children less than 5 years of age.2 Unfortunately, no successful vaccine is available, and most of the strains of malarial parasite are becoming resistant to available anti-malarial drugs—quinine3 and artemisinin derivatives. 4

In Saudi Arabia, malaria control activities started in 1948 in the Eastern province. However, a joint Saudi-World Health Organization (WHO) pilot malaria control project was launched in March 1952, and it was not until 1956 that a national malaria control service was established. In 1963, Saudi Arabia signed a pre-eradication program plan with the World Health Organization and started the destruction of reservoir of infection, public health education, large-scale vector control (by spraying residential houses with dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) in hyperendemic areas, weekly application of larvicides, ultra–low-volume space spraying, prompt treatment of malaria cases, and training of health workers on the control and management of malaria. 5,6

The substantial progress in the interruption of malaria in the Eastern and Northern provinces and its clearance from the Western province and the valley of the Aseer region was made since 1980, and Saudi Arabia has since witnessed a substantial decline in the incidence of malaria.6

However, the economic strategic position of Saudi Arabia offering employment to millions of people from countries known to be endemic for malaria and the millions of people coming from all over the world to perform Hajj makes the country highly susceptible to malaria importation. An active sentinel surveillance system was established particularly in the Makkah region, which receives millions of people every year. This report presents the frequency of malaria disease, type of malarial parasite, and nationality of malaria cases seen over a period of 4 years (2008–2011) in the Makkah region.

METHODS

Saudi Arabia has an established surveillance and reporting system for malaria. It is mandatory in Saudi Arabia to report all malaria cases seen in primary health centers and hospitals within 24 hours to the malaria elimination program unit with a detailed surveillance sheet showing the personal details and movements or travels. Each vector control unit at provincial level has a number of sentinel sites that report on a weekly basis to the provincial center. The center, in turn, collates the data from all the sites and sends them directly by fax to the headquarters of the malaria elimination program in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. At the malaria elimination program unit, the data is aggregated, analyzed, and sent as weekly reports to the directorate of preventive medicine. The ministry of health summarizes these reports to generate monthly, quarterly, and annual reports. All reports are checked, and appropriate reconciliation is done for the accuracy and completeness of data at different levels of the reporting system on a regular basis. In the Makkah area, the reports of all malaria cases, received from the 19 sentinel sites from 2008–2011, cross checked, and validated, were analyzed in this study. SPSS, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Laboratory-confirmed malaria cases dropped from 63 in 2008 to 48 in 2009, and increased to 93 and 114 in 2010 and 2011, respectively (Table 1). The proportion of children less than 10 years of age declined from 11% in 2008 to 3.6% in 2011 with an overall decline of 6%, including 2.2% under 5 years of age in the 4-year period. Only one fifth cases were adolescents, and young adults (20 years to less than 40 years of age) increased from 35% in 2008 to 43% in 2009 before dropping to 37% in 2010 and 34% in 2011. Less than 10% of cases were 60 years or above.

Table 1.

The age distribution and WHO regions of malaria patients seen in Saudi Arabia over a period of 4 years: 2008–2011.

| Age (y) | 2008 n (%) | 2009 n (%) | 2010 n (%) | 2011 n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 0 – 4 | 3 (4.8) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (1.8) | 7 (2.2) |

| 5 – 9 | 4 (6.3) | 3 (6.3) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (1.8) | 12 (3.8) |

| 10 – 14 | 7 (11.1) | 2 (4.2) | 5 (5.4) | 9 (7.9) | 23 (7.2) |

| 15 – 19 | 7 (11.1) | 4 (8.3) | 12 (12.9) | 17 (14.9) | 40 (12.6) |

| 20 – 24 | 8 (12.7) | 6 (12.5) | 10 (10.8) | 12 (10.5) | 36 (11.3) |

| 25 – 29 | 6 (9.5) | 7 (14.6) | 14 (15.1) | 8 (7.0) | 35 (11.0) |

| 30 – 34 | 3 (4.8) | 3 (6.3) | 6 (6.5) | 8 (7.0) | 20 (6.3) |

| 35 – 39 | 5 (7.9) | 5 (10.4) | 7 (7.5) | 11 (9.6) | 28 (8.8) |

| 40 – 44 | 2 (3.2) | 2 (4.2) | 8 (8.6) | 11 (9.6) | 23 (7.2) |

| 45 – 49 | 5 (7.9) | 4 (8.3) | 5 (5.4) | 10 (8.8) | 24 (7.5) |

| 50 – 54 | 9 (14.3) | 7 (14.6) | 7 (7.5) | 9 (7.9) | 32 (10.1) |

| 55 – 59 | 2 (3.2) | 2 (4.2) | 5 (5.4) | 5 (4.4) | 14 (4.4) |

| ≥60 | 2 (3.2) | 2 (4.2) | 10 (10.8) | 10 (8.8) | 24 (7.5) |

| WHO geographical regions | |||||

| Saudis | 4 (6.3) | 3 (6.3) | 5 (5.4) | 4 (3.5) | 16 (5.0) |

| African region | 26 (41.3) | 16 (33.3) | 29 (31.2) | 40 (35.4) | 111 (34.9) |

| Eastern mediterranean | 28 (44.4) | 25 (52.1) | 45 (48.4) | 52 (46.0) | 150 (47.5) |

| Southeast Asia (SEARO) | 5 (7.9) | 4 (8.3) | 14 (15.1) | 17 (15.0) | 40 (12.6) |

| Total | 63 | 48 | 93 | 114 | 318 |

Nationality of malaria patients

Only 16 patients (5%) were Saudis. The largest number of patients were from the Eastern Mediterranean (150), with Pakistan (34.0%), Yemen (5.3%), and Sudan (3.8%) as major countries and the African region (111) led by Nigeria (16.7%), Mauritania (3.5%), and Mali (3.1%). The Indians (11.6%) were the major importers from the South Asia region (Table 2). Thus, Pakistan, Nigeria, and India accounted for 62.0% of malaria cases in the 4-year period.

Table 2.

The nationalities of malaria patients seen in Makkah, Saudi Arabia: 2008–2011.

| Nationality | Year | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | ||

|

| |||||

| Pakistani | 17 (27.0) | 17 (35.4) | 33 (35.5) | 41 (36.0) | 108 (34.0) |

| Nigerian | 12 (19.0) | 5 (10.4) | 16 (17.2) | 20 (17.5) | 53 (16.7) |

| Indian | 5 (7.9) | 4 (8.3) | 11 (11.8) | 17 (14.9) | 37 (11.6) |

| Yemen | 5 (7.9) | 3 (6.3) | 3 (3.2) | 6 (5.3) | 17 (5.3) |

| Saudi | 4 (6.3) | 3 (6.3) | 5 (5.4) | 4 (3.5) | 16 (5.0) |

| Sudanese | 3 (4.8) | 3 (6.3) | 5 (5.4) | 1 (0.9) | 12 (3.8) |

| Mauritania | 3 (4.8) | 2 (4.2) | 2 (2.2) | 4 (3.5) | 11 (3.5) |

| Mali | 2 (3.2) | 1 (2.1) | 4 (4.3) | 3 (2.6) | 10 (3.1) |

| Ethiopian | 2 (3.2) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (2.6) | 7 (2.2) |

| Niger | 2 (3.2) | 2 (4.2) | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 5 (1.6) |

| Guinea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (4.4) | 5 (1.6) |

| Afghanistan | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.2) | 3 (2.6) | 5 (1.6) |

| Chadians | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.2) | 2 (1.8) | 4 (1.3) |

| Comoros | 2 (3.2) | 2 (4.2) | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.3) |

| Somalia | 2 (3.2) | 1 (2.1) | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 4 (1.3) |

| Ivory Coast | 1 (1.6) | 1 (2.1) | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 3 (0.9) |

| Benin | 1 (1.6) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 3 (0.9) |

| Bangladesh | 0 | 0 | 3 (3.2) | 0 | 3 (0.9) |

| Senegalese | 0 | 0 | 3 (3.2) | 0 | 3 (0.9) |

| Iraqi | 1 (1.6) | 1 (2.1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) |

| Tanzania | 1 (1.6) | 1 (2.1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.6) |

| Egyptian | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Lebanese | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Burkina Faso | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) |

| Total | 63 | 48 | 93 | 114 | 318 |

Types of parasites

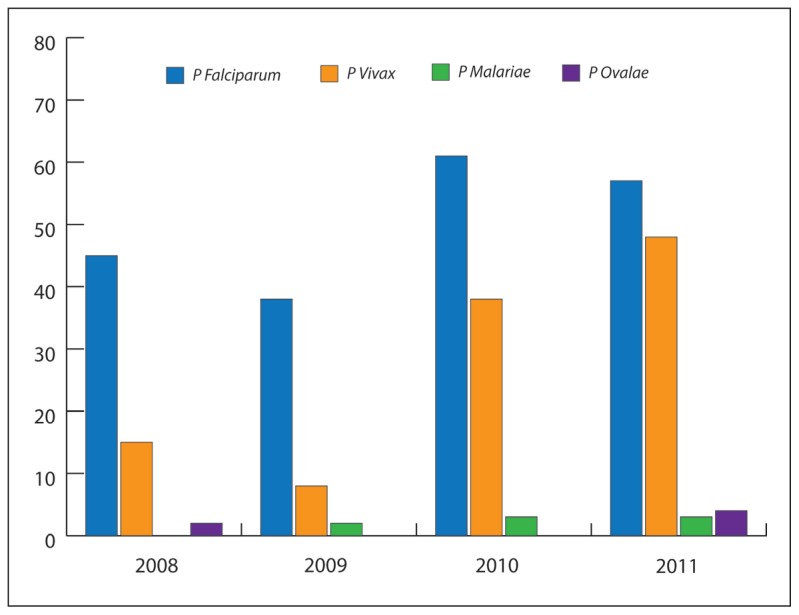

Plasmodium falciparum constituted 64% (73%, 79%, 68%, and 51% in 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011 respectively), and the proportional distribution of the parasites in the 4 years was statistically significant P<.05, specifically between the proportion of this parasite in the first 3 years (2008–2010) and 2011 (Table 2). However, Plasmodium vivax constituted about a third of total cases (25%, 19%, 31%, and 43% in 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011, respectively). There were only 5 cases of Plasmodium ovale (1.6%), one case in 2008 and 4 cases in 2011 (Figure 1). There were 1 case, 2 cases, and 3 cases of Plasmodium malariae in 2009, 2010, and 2011 respectively. The P falciparum and P vivax were found in all the age groups, while a few cases of P malariae were observed in adults 40 years and above. The 5 cases of P ovale were distributed equally in patiens at 10-year intervals between age 10 and 60 years. About 89% of malarial parasites from Nigeria were P falciparum in contrast to 47% seen in patients from Pakistan and about 41% of those from India. But, about 54% of Indian patients and 47% of Pakistani patients had the P vivax as against 11% of such parasites from Nigeria. Pakistan and India together accounted for about 70% of all cases of P vivax. Four of the 5 cases of P ovale were diagnosed from the Pakistani patients and the remaining 1 from a Saudi. The 6 cases of P malariae were distributed between Pakistan (33.3%), India (33.3%), Comoros Island (16.7%), and Ethiopia (16.7%). More than two thirds of the Saudi cases were infected with P falciparum (69%), followed by P vivax (25%).

Figure 1.

The types of malaria parasite isolated in Saudi Arabia: 2008–2011.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated a reduction in the local transmission of malaria. The age distribution of malaria cases, which was concentrated to the middle age group, is a reflection of the age group of nationals coming to Saudi Arabia either for hajj or employment. The finding that the few malaria patients less than 10 years of age were non-Saudis suggested that the local transmission must have been truncated. This is an interesting finding that of 1.5 to 2.7 million estimated deaths from malaria yearly, 70% to 90% of them were children less than 5 years of age.3,7

The low occurrence of malaria observed among Saudis, especially among children less than 5 years of age, is good evidence of the success of the malaria eradication program in Saudi Arabia, similar to the public health control approach by nations with successful eradication of malaria.5

According to the WHO, the present phase of malaria eradication in Saudi Arabia is more of the consolidation phase.5 Therefore, monitoring must continue on a periodic basis with an emphasis on adherence to the basic public health control strategies for sustainability of the gains already accomplished. The preponderance of non-Saudis among cases of malaria seen in Makkah corroborates reports of cross-border transmission of malaria, WHO, 2008.8 And the low level of imported malaria as well as the significant decrease over the years of P falciparum is in consonance with a drop in imported malaria in England, which could be an indication of falling malaria incidence globally over the last 5 years.2,6

However, a policy implication of these findings for the Saudi health authority may be to advise all health care workers working in Saudi Arabia to be on the lookout for malaria in pilgrims and others coming from (Pakistan, Nigeria, and India) if ever they present with febrile illness while in Saudi Arabia. Albeit, the present effective control of the vector suggests that visitors are less likely to be re-infected and so the chance of continuous transmission could be reduced.9 The distribution of the type of parasite is in agreement with the worldwide knowledge.10 The P falciparum is known to be most common in tropical Africa while P vivax in Asia. Fortunately, intense observation and experimentation over the last 150 years have yielded an immense amount of knowledge about the life cycle and transmission of the Plasmodium parasites. P falciparum is responsible for a high percentage of malaria fatalities and P malariae exhibits extreme longevity in the host, surviving for up to 50 years, and is known to be more resistant to anti-malarial drugs. Both P ovale and P vivax persist in the liver of their hosts, and causes relapse.10

Table 3.

The distribution of types of parasite by age group of malaria patients {2008–2011).

| Type of malaria parasite | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P falciparum | P vivax | P malariae | P ovale | |||

|

| ||||||

| Age group of patients | 0 – 9 | 15 (78.9) | 4 (21.1) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19 |

| 10 – 19 | 40 (63.5) | 22 (34.9) | 0.0 | 1 (1.4) | 63 | |

| 20 – 29 | 48 (67.6) | 22 (31.0) | 0.0 | 1 (1.4) | 71 | |

| 30 – 39 | 33 (68.8) | 14 (29.2) | 0.0 | 1 (2.0) | 48 | |

| 40 – 49 | 29 (61.7) | 15 (31.9) | 2 (4.3) | 1 (2.1) | 47 | |

| 50 – 59 | 27 (58.7) | 16 (34.8) | 2 (4.3) | 1 (2.2) | 46 | |

| 60 – HI | 12 (50.0) | 10 (41.7) | 2 (8.3) | 0.0 | 24 | |

| Year of presentation | 2008 | 46 (73.0) | 16 (25.4) | 0 | 1 (1.6) | 63 |

| 2009 | 38 (79.2) | 9 (18.8) | 1 (2.1) | 0 | 48 | |

| 2010 | 62 (66.7) | 29 (31.2) | 2 (2.2) | 0 | 93 | |

| 2011 | 58 (50.9) | 49 (43.0) | 3 (2.6) | 4 (3.5) | 114 | |

| WHO regions | Saudis | 11 (68.8) | 4 (25.0) | 0.0 | 1 (6.3) | 16 |

| African region | 89 (80.2) | 20 (18.0) | 2 (1.8) | 0.0 | 111 | |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 87 (57.6) | 58 (38.4) | 2 (1.3) | 4 (2.6) | 151 | |

| South East Asia (SEARO) | 17 (42.5) | 21 (52.5) | 2 (5.0) | 0.0 | 40 | |

| Total | 204 (64.1) | 103 (32.4) | 6 (1.9) | 5 (1.6) | 318 | |

In conclusion, the low frequency of malaria seen in the Makkah region is good evidence of the success of malaria eradication programs in Saudi Arabia. Without bias to the completeness of the malaria surveillance system, the current level of malaria elimination fits into the second phase of the basic tenets of the 3-phase agenda (attack, consolidation, and maintenance) for the global eradication of malaria.7 The present eradication measures should be consolidated, and with an adequate control of the vectors, the chances of local transmission will be very low.11 Also the surveillance system in all the regions of Saudi Arabia should be continuously monitored for accuracy, timeliness, and completeness of all records. Health workers should consider malaria as the first line of suspicion for pilgrims from Pakistan, Nigeria, and India with febrile illness.

Footnotes

Competing interests

None declared.

Author’s contribution

ZAM, MA, and RH conceived the study, designed the study protocol, and carried out the clinical assessment; EAB carried out the statistical analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript. ZAM MA, RH, and HNS critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. ZAM, RH, and MA are guarantors of the paper.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Funding

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bruce-Chwatt LJ. Essential malariology. London: Williams Henneiman Medical Books Ltd; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) World Malaria Report. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloland PB. WHO/CDS/CSRIDRS/2001. World Health Organisation; Geneva. Switzerland: 2001. Disease incidence and trends En Bioland, PB Drug resistance in malaria. No 20012-11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duff PE, Sibley CH. Are we losing the artemisinin combination therapy already? Lancet. 2005;366:1908–1909. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67768-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Malaria Eradication Program in the United States NMEPUS. [Last Access August 21]. http://en.wikipeddia.org/wiki/National-Malaria-Eradication-Program.

- 6.Phillips RS. Current status of Malaria and Potential for Control. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2001 Jan;14(1):208–226. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.1.208-226.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO meeting on cross-border collaboration on malaria elimination; 23–25; September 2008; Antalya, Turkey. [accessed 27 April 2013]. http://www.euro.who.int/data/assets/pdf_file/0008/98774/E92012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Health England; Malaria imported into the United Kingdom in 2012: implications for those advising travelers. Public Health Report. 2013 Apr 26;7(17) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snow RW, Marsh K. New insights into the epidemiology of malaria relevant to disease control. British Medical Bulletin. 1998;54(2):293–309. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rich SM, Ayala FJ. Evolutionary Origins of Human Malaria Parasites. In: Dronamraju Krishna R, Arese Paolo., editors. Emerging Infectious Diseases of the 21st Century: Malaria - Genetic and Evolutionary Aspects. Springer; US: 2006. pp. 125–146. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clyde DF. Recent Trends in the Epidemiology and Control of Malaria. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1987;9:21–243. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]