The emergence of a novel human coronavirus recently renamed the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) from the Arabian Peninsula has created global alarm because it is the causative agent of a severe and frequently fatal acute respiratory illness (SARI) resembling the illness caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus (SARS-CoV).1–4 The case fatality rate (CFR) in patients infected with MERS-CoV is high—estimated at 43% in 147 patients reported so far by World Health Organization (WHO).3 This rate is higher than that of SARS—estimated at 15%, and is strongly age- and sex-dependent.4 Although the source of virus in patients with sporadic infection remains unknown, it appears likely to be some species of animal.4,5 Clear evidence of limited human-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV has now been documented in several case clusters, including particularly family members and patients in health care facilities,6–8 but all such clusters have, at least thus far, been limited in extent. However, a real concern persists that the virus will adapt to interhuman transmission and switch from an aborted epidemic to a pandemic similar to the SARS-CoV epidemic in 2003–2004. MERS-CoV is transmitted through droplets and contact. In the case of invasive respiratory procedures, MERS-CoV is transmitted through airborne route.2 Early diagnosis and strict implementation of the core components for infection prevention and control programs are crucial for preventing epidemic amplification. 2 In the absence of an effective vaccine and a specific antiviral treatment, there is an urgent need to rapidly identify potential therapeutics.

Coronaviruses: Back to Basic

The name “coronavirus” was coined in the mid-1960s, and it was derived from the “corona”-like or crown-like morphology observed for these viruses when viewed in negatively stained preparations under electron microscope. Coronaviruses are enveloped, spherical, or pleiomorphic viruses, typically about 100 nm in diameter, and are the largest positive-strand RNA viruses. They possess a 5′-capped, single-strand positive-sense RNA genome, with a length between 26.2 and 31.7 kb—the longest among all RNA viruses. The genome is packaged into a helical nucleocapsid surrounded by a host-derived lipid bilayer. The virion envelope contains at least 3 viral proteins: the spike protein (S), the membrane protein (M), and the envelope protein (E). The M and E proteins are involved in virus assembly, whereas the spike protein is the leading mediator of attachment and viral entry.9,10 The spike protein is also a major factor in determining the host range. Coronaviruses are classified into the following 4 different genera, historically based on serological analysis and now on genetic studies: alpha-, beta-, gamma-, and delta-CoV (Table 1). In animals they cause a wide variety of respiratory, enteric, central nervous system (CNS), and other diseases, whereas in humans they cause primarily respiratory infections.9,10 The 5 human coronaviruses are as follows: alpha coronaviruses including 229E and NL63, and beta coronaviruses including OC43, HKU1, and SARS-CoV (the coronavirus that caused the SARS epidemic in 2002–2003).11 Although the human coronaviruses were discovered only in the beginning of 1960s, they have probably been circulating in the human population worldwide for a long time. HCoV-OC43 apparently jumped from a bovine host into humans about 120 years ago and has become endemic worldwide.12 Interest in this family of viruses grew in the aftermath of the SARS coronavirus, which resulted in a global outbreak of pneumonia in 2003 affecting people in approximately 30 countries and resulting in about 800 deaths.11 This episode led to the identification of many new family members, and also shed light on the capabilities of coronaviruses to jump across species boundaries.

Table 1.

Coronavirus taxonomy.

| Order | Nidovirales |

| Family | Coronaviridae |

| Genera | Alphacoronavirus Betacoronavirus Deltacoronavirus Gammacoronavrus |

| Genome | (+)ssRNA, ~30 kb (20–33 kb) |

| Genes | 1a, 1b, S, E, M, N, Assorted ORFs |

MERS-Coronavirus

In June 2012, a novel human coronavirus was identified in a Saudi Arabian businessman who died of an acute respiratory illness and renal failure.5 Since that time, the same virus has returned in both sporadic cases, in small clusters, and in large health care facilities outbreaks. To date, cases have been reported from 9 countries: Jordan,8 Saudi Arabia,5 Qatar,3 the UK,13 Germany,14 the United Arab Emirates (UAE),3 Tunisia,15 France,16 and Italy17 (Table 2). All cases either occurred in the Middle East or had direct links to a primary case infected in the Middle East.3,6,18 In May 2013, the Coronavirus Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses named the novel coronavirus as “Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV),” on the basis of the outbreak dynamic.1 The presence of MERS-CoV was demonstrated by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and the isolation of the virus from respiratory secretions.5,19–22 The analysis of the genome size, organization, and sequence revealed that MERS-CoV is a Betacoronavirus in lineage c (significantly different from SARS-CoV, which is also a Betacoronavirus but in lineage b) and human betacoronaviruses OC43 and HKU1 which are placed in lineage a.4,5 The virus is most closely related to several bat coronaviruses from various bat species in Africa and Eurasia23 The polymerase amino acid sequence of the most closely related bat virus (VM314) differs from MERS-CoV only by 1.8% (as opposed to the HKU5, which differs by 5.5%–5.9%).5,23 MERS-CoV genetic sequences from 21 cases in Saudi Arabia have been pooled with 9 previously published MERS-CoV genomes. The investigators estimate that MERS-CoV emerged in July 2011, though the emergence could have occurred as early as July 2007.24 The reservoir and hosts of the MERS-CoV are still unknown. Although virus RNA was possibly detected from bat feces collected in the vicinity of the index case, it seems unlikely that bats are the immediate contact for the human cases because human–bat contacts are of relatively low frequency.25 Two independent studies suggested that dromedary camels in Oman, the Canary Islands, and Egypt might have been infected with the virus or a MERS-CoV-like virus in the past. However, human cases were not detected in these areas.26,27 Further surveillance of both bats and other potential reservoirs is ongoing and the epidemiology of this virus will become clearer. With the exception of extensive sequence data,23 information on the biology of the MERS-CoV or its pathogenicity in man is scant. Studies in vitro revealed a broad tropism for replication in cell lines originating from different mammalian species, potentially indicating a low barrier for cross-species transmission.28 As compared with other coronaviruses, MERS-CoV was isolated and propagated relatively easily in Vero and LLC-MK2 cells. The only other human coronaviruses that replicate well in these monkey-cell lines are SARS-CoV and HCoV-NL63, both of which use human angiotensin–converting enzyme 2 as their receptor.29 In contrast, the cell receptor for the MERS-CoV has been identified as dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4).30 The DPP4 protein, a common protease, is expressed on several epithelial cells, including primary human bronchiolar lung tissue, and is consistent with the ability of the virus to infect the lower respiratory tract. The protein is also present on the epithelium of kidney, small intestine, liver, and prostate.20 In infected patients, MERS-CoV has been detected in the respiratory tract, blood, urine, and rectal mucosa. Whether the virus replicates in the respiratory tract and then disseminates to other organs, such as kidney or gastrointestinal mucosa, remains to be determined. MERS-CoV has been shown also to infect rhesus macaques, allowing the development of an experimental animal model. In this model, extensive viral pneumonia occurs, demonstrating at least partial fulfillment of Koch postulates.31

Table 2.

MERS cases and deaths.

| Countries | Cases (Deaths) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| France | 2 (1) |

| Italy | 1 (0) |

| Jordan | 2 (2) |

| Qatar | 6 (3) |

| Saudi Arabia | 124 (52) |

| Tunisia | 3 (1) |

| UK | 3 (2) |

| UAE | 4 (2) |

| Germany | 2 (0) |

| Total | 147 (63) |

NB. Current as of October 27(modify Ref.3)

Epidemiology

The earliest known cases of MERS were in a small cluster in Zarqa city in Jordan.8 In April 2012, an outbreak of high fever and acute lower respiratory symptoms of unknown etiology was reported by the Ministry of Health in Jordan in an intensive care unit (ICU) of a hospital in Zarqa with a high rate of transmission to health care workers (HCWs). Among the 11 people affected, 7 were nurses and 1 internist; 1 of the nurses later died. In October 2012, after the discovery of the MERS-CoV, stored samples from this outbreak were tested, and the diagnosis of MERS-CoV was confirmed by RT-PCR in 2 of those who had died—the index patient and the male nurse caring for him. Further analysis identified 11 probable cases from this outbreak of whom 10 were HCWs and 2 were family members of cases.8

The first laboratory confirmed case from which the virus was first isolated was reported on September 20, 2012.5 A 60-year-old Saudi man from Bisha was transferred on June 13, 2012 to a private hospital in the port city of Jeddah, with a 7-day history of fever, cough, and shortness of breath that progressed to acute respiratory distress syndrome with multi-organ dysfunction syndrome, similar to what has been described in severe cases of influenza and SARS. Hematologic changes were evident in this patient in the form of lymphopenia, neutrophilia, and late thrombocytopenia. This patient had no underlying condition and no history of animal contact. He died of progressive respiratory and renal failure. A postmortem examination was not performed. 5 Since that time, MERS has returned as sporadic cases and small clusters in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the UAE, and Jordan. Cases also appeared in the UK, Germany, Tunisia, France, and Italy, and these cases originated in adults who came from or were traveling in the Middle East. Certain MERS cases were clearly transmitted between human beings, primarily in health care and hospital settings but also within families. The incubation period for MERS-CoV is still largely unknown but was reported as prolonged in 1 documented instance of person-to-person nosocomial transmission (9–12 days).32 SARS-CoV also demonstrated a prolonged incubation period (median 4–5 days; range 2–10 days) compared to other human coronavirus infections (average 2 days; typical range 12 hours to 5 days).11,33 Allowing for inherent variability and recall error, an exposure history based on the prior 14 days is a reasonable and safe approximation. No reported instance of transmission has been reported before the onset of symptoms of disease. Transmission to casual and social contacts is uncommon. In Saudi Arabia where the majority of laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV were reported, we observed 3 main epidemiological patterns. In the first pattern, sporadic cases occur in communities. Surveillance of immediate and neighboring premises were performed for several cases, along with investigations of adjoining areas and locales such as rest houses (istirahat) and farms that had been visited by cases. This was used to guide specimen collections that were forwarded to reference laboratories for sequencing studies. The hypothesis of bats being the possible source of infection is underlined by a study where bats were captured or their feces were collected during 2 samplings in October 2012 and April 2013 in regions of Saudi Arabia where cases were reported. Of a total of 1003 samples, only 1 positive sample of MERS-CoV was identified in October 2012 in a fecal pellet of the bat species Taphozous perforatus from Bisha, a town in the vicinity of the place of residence of the index case.25 The fact that no other sequence information could be generated from this animal might indicate a very low virus load in the sample, but this does not rule out higher divergence within other genomic regions. Considerable efforts are under way to identify possible animal sources of MERS-CoV infection.

In the second pattern, clusters of infections occur in families. A first cluster occurred in October 2012. Of the 4 individuals in the household, 3 were laboratory-confirmed cases, of which 2 died. A second cluster between 2 family contacts occurred in February 2013. One of the individuals died, and 1 recovered after experiencing a mild respiratory illness. Similar family clusters occurred in both the UK and Tunisia.7,15 These clusters provided clear evidence of human-to-human transmission among family members possibly involving different modes, such as droplet and contact transmission. The risk of MERS-CoV infection among close contacts of patients is low, although the infection risk is increased in patients with immunosuppression or co-existing illnesses.

The third pattern comprises clusters of infections in health care facilities. Such events were reported in France, Jordan, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia.3 The largest cluster was recently reported from hospitals in the governoate of Al-Hasa, in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia between April 1 and May 23, 2013: 23 confirmed and 11 probable cases were diagnosed as part of a single outbreak that involved four healthcare facilities.33,34 The majority of cases were patients, but 5 family members and 2 health care workers were also affected. The hemodialysis unit was the most heavily affected, with 9 confirmed cases, but transmission also occurred in the ICU and the medical ward. Based on the epidemiology, one of the patients in the hemodialysis unit appeared to have transmitted the infection to 7 persons, another patient apparently infected 3 persons, and 4 patients transmitted the infection to 2 persons each. The median incubation period was 5.2 days, with a range of 1.9 to 14.7 (95% CI).34 The outbreak was reminiscent of SARS,35–39 with 7 secondary cases transmitted in a hemodialysis unit. It could have been caused by multiple zoonotic or human introductions in the community or inconsistent application of appropriate infection control practices by hospitals. Despite a thorough investigation, the questions whether the person-to-person transmission occurred through respiratory droplets or direct contact, or whether it was airborne remain unanswered. Based on the currently available data, the airborne transmission of MERS-CoV cannot be excluded, but there is no indication that it plays an important role in the transmission of the virus. Of the 23 coronavirus-infected individuals in this outbreak, 65% died. Most of the cases in this cluster had comorbidities.34 With strict infection control measures in place, the outbreak was effectively controlled and no more new cases were reported. This shows that preventive infection control measures are crucial to prevent the spread of this virus. At the moment there is no evidence of any change in the infectiousness of MERS-CoV. However, the pandemic potential of MERS-CoV remains low. The basic reproduction number (R0) was estimated at 0.69, lower than the R0 for prepandemic SARS (0.80) and well below the epidemic threshold of 1.40

Clinical Disease

MERS-CoV infection has affected persons aged >24 years, except for 7 children, aged 2 to 18 years. The median age of patients is 50 years (range: 2–94 years).18 Earlier reports suggested a predominance of male patients, but later series showed a larger proportion of younger female cases. The male-to-female ratio is 1.6:1.4,18 The reason for the strong male predominance in the beginning of the outbreak remains unexplained The proportion of cases associated with health care settings has increased substantially, and now accounts for 23% of all reported cases.18 MERS occurs more frequently among persons with chronic underlying medical conditions or immunosuppression (Table 3), but some were in previous good health.41 The severity of illness associated with MERS-CoV infection ranges from mild to fulminant with the majority experiencing severe acute respiratory disease requiring hospitalization.18,22,41,42 A total of 18 asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic cases were reported. All cases were without any symptom or were very mild with 1 episode of fever with or without myalgia and chills. In Saudi Arabia, 16 asymptomatic cases were detected during screening of all contacts of diagnosed cases. The remaining 2 asymptomatic cases were detected in the UAE. The recent identification of milder or asymptomatic cases of MERS in health care workers, children, and family members of MERS cases indicates that the severe disease that predominates among proven cases likely represents the tip of the iceberg, and there is a spectrum of milder disease that requires definition.4,18,41 The clinical syndrome is similar to SARS in which case infected persons present initially with fever myalgia, malaise, and chills or rigor (Table 4).43–46 Cough is common, but shortness of breath, tachypnea with progression to pneumonia, and respiratory failure occur early, particularly in patients with comorbidities. Unlike other atypical pneumonias caused by mycoplasma, viruses, or chlamydia, upper respiratory symptoms such as rhinorrhea and sore throat are uncommon. One in 4 or 5 patients had accompanying gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea.41 One patient, with an underlying immunosuppressive disorder, presented with fever, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, but no respiratory symptoms initially; pneumonia was identified incidentally on a radiograph.47 Lymphocytopenia was common with a normal neutrophil count on admission, and in some patients the platelet count was depressed with a consumptive coagulopathy. The levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate transaminase, and lactate dehydrogenase were raised.33,41 Other biochemical values were normal in the majority of patients. However, these laboratory findings did not allow reliable discrimination between MERS and other causes of community-acquired pneumonia.

Table 3.

People at high-risk of developing severe MERS-CoV infection.

| Diabetes |

| Chronic kidney disease |

| Chronic heart disease |

| Hypertension |

| Chronic lung disease |

| Obesity |

| Smoking |

| Malignant disease |

| Steroid use |

MERS-CoV: Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus.

Table 4.

Comparison of demographic, clinical, and laboratory features of MERS-CoV with SARS-CoV infection.a

| Variables | MERS-CoV | SARS-CoV |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Demographics | ||

| Number of cases | 136 | 752 |

| Incubation periods (days; mean 95%) | 5.2 (1.9–14.7); range 2–13 | 4.6(3.8–5.8); range 2–14 |

| Age of patient | 56 (mean 14–94) | 39.9 (mean 1–91) |

| Percent of children | 5–6% | 5–7% |

| See distribution no. | 83 male, 53 female | 343 males, 409 females |

| Ratio of male to female | 1.6:1 | 0.84:1 |

| Clinical featuresb (%) | ||

| Fever >38°C | 98 | 99.9 |

| Chills or rigors | 87.1 | 51.5 |

| Myalgia | 32.1 | 48.5 |

| Malaise | 38 | 58.8 |

| Cough | 83 | 65.5 |

| Rhinorrhea | 46 | 13.8 |

| Sore throat | 21 | 16.5 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 21 | 26.7 |

| Diarrhea | 26 | 20.1 |

| Mortality | 43 | 0–40 |

| Laboratory Resultsb (%) | ||

| Leukopenia (<40.0×109 cells/L) | 14 | 24.2 |

| Lymphopenia (1.5×109 cells/L) | 34 | 66.4 |

| Thrombocytopenia (<140×109 cells/L) | 36 | 29.7 |

| Elevated serum alanine aminotransferase level | 11 | 44.1 |

| Elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase level | 49 | 45.6 |

| Radiographic manifestationsb (%) | ||

| Initial abnormal chest radiograph | 100 | 60–100 |

Modify from R42, 43.

Based on published papers.

MERS-CoV: Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, SARS-CoV: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

Depending on the interval between the onset of fever and hospital admission, initial chest radiographs were abnormal in all cases. A spectrum of the following radiographic abnormalities was seen: ground-glass opacifications or patchy-to-confluent air space consolidation, nodular opacities, reticular opacities, reticulonodular shadowing, and pleural effusions. Progression from unilateral focal air space opacities to multifocal or bilateral involvement was frequent in patients admitted to the ICU.33,41 About 89% of patients reported from Saudi Arabia required admission to an ICU, and 72% required mechanical ventilation or the implementation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Forty-two of the 77 patients were reported to have died (case-fatality rate [CFR]: 60%).41 The mortality rate was similar in female and male patients. CFRs were higher with increasing age. The terminal events were severe respiratory failure, multiple organ failure, and sepsis. The cumulative CFR decreased from 60% to 43%, calculated from the beginning of the outbreak until October 4, 2013,18 which may be a reflection of enhanced surveillance activities. All deaths were reported among adults except one in a 2-year-old child.4

Diagnosis

MERS is a viral pneumonia that progresses rapidly. The initial manifestations of MERS are not specific, and it cannot be clinically differentiated from other acute community-acquired pneumonias. The occurrence of lower respiratory disease, particularly pneumonia, in epidemiologically linked patient clusters raises the level of suspicion but is not unique to MERS. Diseases such as influenza can cause similar outbreaks. The case definition of MERS has been refined over time (Table 5).48 Given the lack of characteristic clinical features associated with MERS, the definition of cases relies heavily on a history of contact with known patients.

Table 5.

Revised interim case definition for reporting to WHO: MERS-CoV.a

| Probable case |

|---|

| Three combinations of clinical, epidemiological, and laboratory criteria can define a probable case: |

| A person with a febrile acute respiratory illness with clinical, radiological, or histopathological evidence of pulmonary parenchymal disease (e.g., pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome) AND Testing for MERS-CoV is unavailable or negative on a single inadequate specimen AND The patient has a direct epidemiological link with a confirmed MERS-CoV case. |

| A person with a febrile acute respiratory illness with clinical, radiological, or histopathological evidence of pulmonary parenchymal disease (e.g., pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome) AND An inconclusive MERS-CoV laboratory test (i.e., a positive screening test without confirmation) AND A resident of or traveler to Middle Eastern countries where MERS-CoV virus is believed to be circulating in 14 days before onset of illness. |

| A person with an acute febrile respiratory illness of any severity AND An inconclusive MERS-CoV laboratory test (i.e., a positive screening test without confirmation) AND The patient has a direct epidemiological-link with a confirmed MERS-CoV case.2 |

|

|

|

Confirmed case A person with laboratory confirmation of MERS-CoV infection. |

MERS-CoV: Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, WHO: World Health Organization.

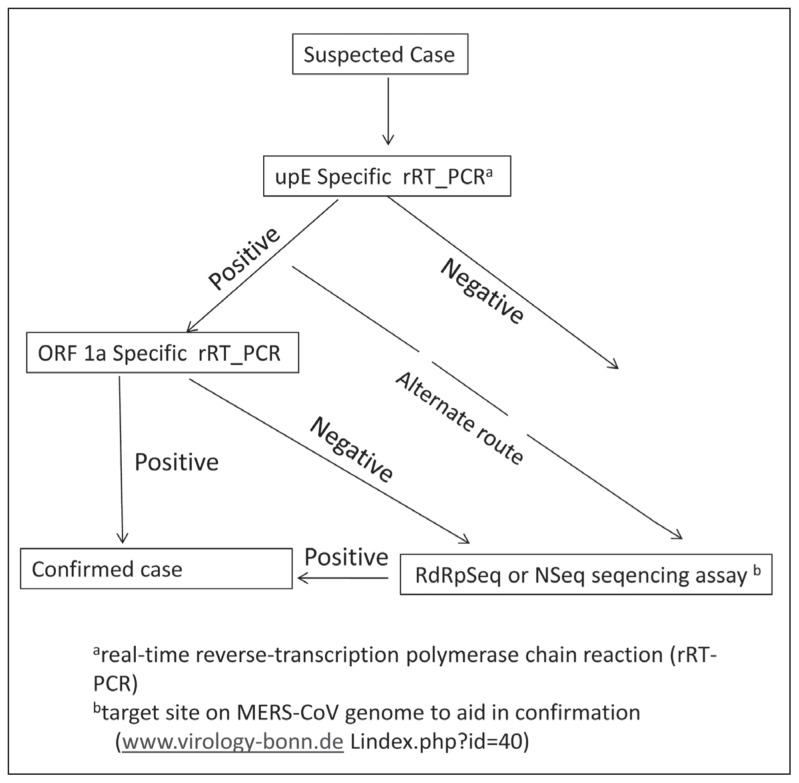

The first molecular identification of a MERS-CoV was completed using a conventional (non-real-time) pan-coronavirus RT-PCR. More specific real-time RT-PCR assays were described later.49 Subsequently, a number of RT-PCR assays that are specific for the novel coronavirus were developed. Currently described tests include an assay targeting upstream of the E protein gene (upE) and assay targeting the open reading frame 1b (ORF 1b) and the ORF 1a gene. The assay for the upE target is considered highly sensitive, with the ORF 1a assay considered to be of equal sensitivities. The ORF 1b assay is considered less sensitive than the ORF 1a assay but may be more specific (Figure 1).50,51 In our national reference laboratory in Saudi Arabia we are targeting both upE assay for screening and ORF1a assay for confirmation. Diagnostic laboratory work and PCR analysis should be conducted on clinical specimens from patients who are suspected or confirmed to be infected with novel coronavirus adopting practices and procedures described for basic laboratory— Biosafety Level 2 (BSL-2).52,53 There is a need to have a carefully designed protocol that is adhered to for the collection and transport of samples, including appropriate cold chain, avoiding freezing until the specimens reach the destination laboratory.

Figure 1.

Testing algorithm for suspected cases for MERS-CoV (modified Ref 50).

Evidence suggests that nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs are not as sensitive as lower respiratory specimens for detecting MERS-CoV infections. NP swabs were negative in patients who were close contacts of confirmed cases and who developed pneumonia following contact. In addition, a number of cases had negative tests on NP swabs with positive tests of lower respiratory tract specimens. 54 Lower respiratory tract specimens included sputum, endotracheal aspirate for patients on mechanical ventilation, and bronchial alveolar lavage for those in whom it is indicated for patient management.52,53 Patients, in whom the diagnosis was strongly suspected on the basis of epidemiological and clinical data, might not be adequately excluded as having infection based solely on a single negative NP swab. The MERS-CoV strain has been demonstrated to grow well in cell lines using LLC-MK2 and Vero cells. Virus isolation in cell culture is not recommended, but if done, these activities must be performed in BSL-3 facilities.55,56 A serological test based on indirect immunofluorescence using convalescent patient serum has been described.51 Recently a serological tool based on protein microarray technology has been developed for the specific detection of IgM and IgG antibodies against MERS-CoV. The tool has been validated with a limited number of specimens using putative cross-reacting sera of patient cohorts exposed to the 4 common hCoVs and sera from convalescent patients infected with MERS-CoV or SARS-CoV.57,58 This assay will aid the diagnosis in individual patients, as well as confirm positive tests. It will also be useful in contact studies and for human and animal population screening. This will need to be validated for use in the Middle East.

Management

Early diagnosis and strict implementation of the current WHO guidelines for preventing infection and control during the care of probable or confirmed cases of MERS-CoV are crucial for preventing spread.59 General supportive care continues to be the keystone for managing patients who have an acute respiratory failure and a septic shock as a consequence of severe infection.2 Patients with suspected MERS-CoV infections were initially treated empirically with broadspectrum antibacterial drugs that are effective against other agents that cause typical and atypical acute community-acquired pneumonia to exclude these diagnoses. 2,60,61

A review of published reports by the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC)61 suggested that the use of convalescent sera from recovered patients, although untested, is likely to be the best therapy because of its likely efficacy in the treatment of subjects with SARS-related pneumonia. Viral kinetic data for MERS-CoV are currently lacking, and knowledge in this area will facilitate planning of infection control and clinical management. The administration of convalescent plasma for SARS-CoV within 14 days of the onset of illness was associated with a higher discharge rate on day 22 of illness than for those who received convalescent plasma late or not at all.61,62 Although convalescent plasma may provide a useful treatment modality for severe MERS-CoVco disease; however, the use should be accompanied by an appropriately planned evaluation of effectiveness. Peg IFN was 50 to 100 times more effective for MERS-CoV than SARS-CoV.63 Recent published data suggests this is the most active agent in vitro of various compounds screened. Type I and III IFN efficiently reduced MERS-CoV replication in HAE cultures. MERS-CoV appears to be 50 to 100 times more sensitive to IFN-α than is SARS-CoV.63,64 A 16-hr subcutaneous administration with ribavirin in MERS-CoV–infected macaques led to improvements in clinical signs, radiographic changes, and viral load. The combination appeared to have no clinical benefit when given to patients infected with MERS-CoV.42 There is limited, inconsistent evidence that Lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra) has in vitro anti-SARS-CoV effect and possible clinical benefit in patients, though the scientific rationale for these effects is unclear.65 Ongoing in vitro studies with MERS-CoV are not yet conclusive, and there is no evidence that administration would be beneficial for patients with MERS-CoV.62 Early in vitro evidence suggests cyclosporin A—a potential pan-CoV inhibitor—demonstrates some in vitro effect against MERS-CoV, although no clinical or animal studies exist.63 The use of cyclosporine A is not recommended outside of an appropriately planned evaluation of effectiveness. The ISARIC recommends that neither ribavirin nor corticosteroids be used outside of a randomized clinical trial (unless for some other clinical indication) because of their potential severe adverse side effects.

Conclusion

The MERS-CoV is a highly pathogenic emerging respiratory virus that has caused a small but lethal epidemic centered in Saudi Arabia but capable of limited person-to-person spread. The cause is a Betacoronavirus, which is most closely related to several bat coronaviruses but probably transmitted by some still unidentified intermediate animal host. The virus produces severe and progressive pneumonia, frequently accompanied by renal failure. The virus appears to infect preferentially older adults with underlying illness, although younger adults and children have also been infected. The range of illness varies from asymptomatic infection to pneumonia with respiratory failure, and has been fatal in about half of all recorded infections.

Epidemiological human and animal investigations are required to find and identify the animal reservoir(s) that either directly or indirectly transmits the virus occasionally to humans. Researchers confirmed that the virus was being transmitted from person to person in multiple clusters of MERS-CoV infection. An active surveillance for clusters of cases of severe respiratory disease must be a priority, especially among health care workers. Such surveillance should include the rapid diagnosis and stringent infection control measures for suspected or confirmed human infections. Extensive serological testing of potentially exposed human populations and contacts will be a key indicator of the extent of infection and disease due to novel coronaviruses. General supportive care continues to be the keystone for managing patients who have an acute respiratory failure and a septic shock as a consequence of severe infections. It is difficult to make predictions regarding the future of MERS-CoV, but the following two scenarios are possible in the future: First, the current pattern of ongoing cases could continue, and, the virus could die out and go away similar to SARS-CoV, or second, there could be a change in the transmission pattern leading to more outbreaks and a pandemic. The establishment of a convalescent plasma bank, development of an effective vaccine, and design of randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials to test potential specific antiviral agents are all urgently needed.

REFERENCES

- 1.De Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric RS, Brown CS, Drosten C, Enjuanes L, et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Announcement of the Coronavirus Study Group. J Virol. 2013 Jul;87(14):7790–2. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01244-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infections when novel coronavirus is suspected: What to do and what not to.do. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/InterimGuidance_ClinicalManagement_NovelCoronavirus_11Feb13u.pdf.

- 3.WHO. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – update. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2013_10_04/en/index.html http://www.who.int/csr/don/2013_08_29/en/index.html http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/update_20130813/en/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Penttinen PM, Kaasik-Aaslav K, Friaux A, Donachie A, Sudre B, et al. Taking stock of the first 133 MER S coronavirus cases globally – Is the epidemic changing? Eurosurveillance. 2013;18(39, 26):1–5. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.39.20596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Health Protection Agency (HPA) UK Novel Coronavirus Investigation team. Evidence of person-to-person transmission within a family cluster of novel coronavirus infections, United Kingdom, February 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(11) doi: 10.2807/ese.18.11.20427-en. pii=20427. Available from: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC. Clusters Under Investigations. [Accessed on September 7, 2013]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/mers-clusters.

- 8.Hijawi B, Abdallat M, Sayadeh A, Alqasrawi S, Haddadin A, et al. s from a retrospective investigation. Novel coronavirus infections in Jordan, April 2012: epidemiological finding. EMHJ. 2013;19(1):S12–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyrrel DAJ, Almedia JD, Berry DM, Cunningham CH, Hamre D, Hofstad MS, Malluci L, McIntosh K. Coronavirus. Nature. 1968;220:650. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McIntosh K. Coronaviruses: a comparative review. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1974;63:85–129. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van der Hoek L. Human coronaviruses: what do they cause? Antivir Ther (Lond) 2007;12:651–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vijgen Leen, Keyaerts Els, Moës Elien, Thoelen Inge, Wollants Elke, et al. Complete Genomic Sequence of Human Coronavirus OC43: Molecular Clock Analysis Suggests a Relatively Recent Zoonotic Coronavirus Transmission Event. J Virol. 2005;79(3):1595–1604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1595-1604.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bermingham A, Chand MA, Brown CS, Aarons E, Tong C, Langrish C, et al. Severe respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus in a patient transferred to the United Kingdom from the Middle East, September 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17(40) pii=20290. Available from: http://www.Eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchholz U, Müller MA, Nitsche, Sanewski A, Wevering N, Bauer-Balci T, et al. Contact investigation of a case of human novel coronavirus infection treated in a German hospital, October–November 2012. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(8) pii=20406. Available from: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gulland A. Novel coronavirus spreads to Tunisia. BMJ. 2013;346:f3372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gulland A. Two cases of novel coronavirus are confirmed in France. BMJ. 2013;346:f3114. doi: 10.1136/bmj.F3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puzelli S, Azzi A, Santini MG, Di Martino A, Facchini M, Castrucci MR, et al. Investigation of an imported case of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in Florence, Italy, May to June 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(34) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.34.20564. pii=20564. Available from: http://www.Eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CDC. Updated Information on the Epidemiology of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Infection and Guidance for the Public, Clinicians, and Public Health Authorities, 2012–2013. 2013;62(38):793–796. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corman VM, Eckerle I, Bleicker T, Zaki A, Landt O, et al. Detection of a novel human coronavirus by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Eurosurveillance. 2012;17(39):1–6. doi: 10.2807/ese.17.39.20285-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 2012;17(49):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.S, Guggemos W, Kallies R, Muth D, Junglen S, Muller MA, et al. Clinical features and virological analysis of a case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:745–751. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70154-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guery Benoit, Poissy Julien, el Mansouf Loubna, Séjourné Caroline, Ettahar Nicolas. Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus:a report of nosocomial transmission. The Lancet. 2013;381(9885):2265–2272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Memish ZA, M.D., Zumla Alimuddin I, Md.D, PhD, Al-Hakeem Rafat F, M.D., Al-Rabeeah Abdullah A, M.D, et al. Family Cluster of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infections. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2487–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Annan Augustina, Baldwin Heather J, Corman Victor Max, Klose Stefan M. Human Betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012–related Viruses in Bats, Ghana and Europe. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2011;19(3):456–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1903.121503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cotten Matthew, PhD, Watson Simon J, PhD, Kellam Paul, PhD, Al-Rabeeah Abdullah A, FRCS, Makhdoom HatemQ, PhD, et al. Transmission and evolution of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia: a descriptive genomic study. The Lancet. 2013 Sep 20; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61887-5. Early Online Publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Memish ZA, Mishra N, Olival KJ, Fagbo SF, Kapoor V, Epstein JH, et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus in Bats, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(11) doi: 10.3201/eid1911.131172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reusken CB, Haagmans BL, Muller MA, Gutierrez C, Godeke GJ, Meyer B, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013 Aug 8; doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70164-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perera RA, Wang P, Gomaa MR, El-Shesheny R, Kandeil A, Bagato O, et al. Seroepidemiology for MERS coronavirus using microneutralisation and pseudoparticle virus neutralisation assays reveal a high prevalence of antibody in dromedary camels in Egypt, June 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(36) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.36.20574. pii=20574. Available from: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muller MA, Raj VS, Muth D, et al. Human coronavirus EMC does not require the SARS-coronavirus receptor and maintains broad replicative capability in mammalian cell lines. MBio. 2012;3:e00515–1. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00515-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Josset Laurence, Menachery Vineet D, Gralinski Lisa E, Agnihothram Sudhakar, et al. Cell Host Response to Infection with Novel Human Coronavirus EMC Predicts Potential Antivirals and Important Differences with SARS Coronavirus. mBio. 2013;4(3):e00165–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00165-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raj VS, Mou H, Smits SL, Dekkers DH, Müller MA, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature. 2013;495:251–4. doi: 10.1038/nature12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munster Vincent J, de Wit Emmie, Feldmann Heinz. Pneumonia from Human Coronavirus in a Macaque Mode. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1560–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1215691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Update: Severe Respiratory Illness Associated with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) — Worldwide, 2012–2013. 2013 Jun 7;62 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Joint Kingdom of Saudi Arabia/WHO mission; Riyadh. 4–9 June 2013; http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/MERSCov_WHO_KSA_Mission_Jun13_.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Assiri Abdullah, M.D., McGeer Allison, M.D., Perl Trish M, M.D., Price Connie S, et al. Hospital outbreak of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(5):407–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donnelly CA, Ghani AC, Leung GM, et al. Epidemiological determinants of spread of causal agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Lancet. 2003;361:1761–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13410-1. [Erratum, Lancet 2003;361:1832.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riley S, Fraser C, Donnelly CA, et al. Transmission dynamics of the etiological agent of SARS in Hong Kong: impact of public health interventions. Science. 2003;300:1961–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1086478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipsitch M, Cohen T, Cooper B, et al. Transmission dynamics and control of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1966–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1086616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dye C, Gay N. Modeling the SARS epidemic. Science. 2003;300:1884–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1086925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varia M, Wilson S, Sarwal S, et al. Investigation of a nosocomial outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Toronto, Canada. CMAJ. 2003;169:285–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breban R, Riou J, Fontanet A. Interhuman transmissibility of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: estimation of pandemic risk. Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61492-0. published online July 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Assiri Abdullah, Al-Tawfiq Jaffar A, Al-Rabeeah Abdullah A, Al-Rabiah Fahad A, Al-Hajjar Sami, et al. Epidemiological, demographic and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study? The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 13(9):752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.AlBarrak Ali M, MD, Stephens Gwen M, MD, MSc, Hewson Roger, PhD, Memish Ziad A., MD Recovery from severe novel coronavirus infection. Saudi Med J. 2012;33(12):1265–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peiris Joseph SM, M.D., D.Phil, Yuen Kwok Y, M.D, Osterhaus Albert DME, Ph.D, Stöhr Klaus., Ph.D The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2431–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hui DS, Chan PK. Severe acute respiratory syndrome and coronavirus. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2010;24:619–38. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lee N, Hui DS, Wu A, et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1986–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yieh KM, Peng MY, Lin JC, Wang NC, Chang FY. Clinical and laboratory features in the early stage of severe acute respiratory syndrome. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2006;39:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Booth CM, Matukas M, Tomlinson GA, et al. Ann Saudi Med 2013 September–October www.annsaudimed.net Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 144 patients with SARS in the greater Toronto area. JAMA. 2003;289:2801–09. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.JOC30885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guery B, Poissy J, el Mansouf L, Séjourné C, Ettahar N, Lemaire X, Vuotto F, Goffard A, et al. Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus: a report of nosocomial transmission. Lancet. 2013 Jun 29;381(9885):2265–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.WHO. Revised interim case definition for reporting to WHO – Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/case_definition/en/index.html.

- 49.Corman VM, Eckerle I, Bleicker T, Zaki A, Landt O, Eschbach-Bludau M, et al. Detection of a novel human coronavirus by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Euro Surveill. 2012;(17) doi: 10.2807/ese.17.39.20285-en. pii=20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.WHO. Laboratory testing for novel coronavirus. Available from http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/en/index.html.

- 51.Corman VM, Müller MA, Costabel U, Timm J, Binger T, Meyer B, Kreher P, et al. Assays for laboratory confirmation of novel human coronavirus (hCoV-EMC) infections. Euro Surveill. 2012 Dec 6;17(49) doi: 10.2807/ese.17.49.20334-en. pii: 20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.CDC. Interim Guidelines for Collecting, Handling, and Testing Clinical Specimens from Patients Under Investigation (PUIs) for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Version 2. http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html.

- 53.CDC. Interim Laboratory Biosafety Guidelines for Handling and Processing Specimens Associated with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Jun 7, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/downloads/Interim-MERS-Lab-Biosafety-Guidelines.pdf.

- 54.WHO. Interim surveillance recommendations for human infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/InterimRevisedSurveillanceRecommendations_nCoVinfection_27Jun13.pdf.

- 55.Chan JF, Chan KH, Choi GK, et al. Differential Cell Line Susceptibility to the Emerging Novel Human Betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012: Implications for Disease Pathogenesis and Clinical Manifestation. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1743–52. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kindler E, Jónsdóttir HR, Muth D, et al. Efficient replication of the novel human betacoronavirus EMC on primary human epithelium highlights its zoonotic potential. MBio. 2013;4:e00611–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00611-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reusken C, Mou H, Godeke GJ, van der Hoek L, Meyer B, et al. Specific serology for emerging human coronaviruses by protein microarray. Eurosurveillance. 2013 Apr 04;18(14) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.14.20441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.K-H Chan, et al. Cross-reactive antibodies in convalescent SARS patients’ sera against the emerging novel human coronavirus EMC (2012) by both immunofluorescent and neutralizing antibody tests. J Infection. 2013:S0163–4453. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.WHO. Infection prevention and control during health care for probable or confirmed cases of novel coronavirus (nCoV) infectionInterim guidance. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/IPCnCoVguidance_06May13.pdf.

- 60.International Severe Acute Respiratory & Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) Treatment of MERS-CoV: Decision Support Tool Clinical Decision Making Tool for Treatment of MERS-CoV v.1.1. Jul 29, 2013. http://www.hpa.org.uk/webc/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1317139281416.

- 61.Cheng Y, Wong R, Soo YO, Wong WS, Lee CK, Ng MH, Chan P, et al. Use of convalescent plasma therapy in SARS patients in Hong Kong. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2005;24:44–6. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1271-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chiiueh Tzong-shi, Situ LK, Lin Jung-Chung, Chan PaulKS, Peng Ming-Yieh, et al. Experience of using convalescent plasma for severe acute respiratory syndrome among healthcare workers in a Taiwan hospital. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2005;56:919–922. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de Wilde Adran H, Raj V Stalin, Oudshoorn Diede, Bestebroer Theo M, van Nieuwkoop Stefan, et al. MERS-coronavirus replication induces severe in vitro cytopathology and is strongly inhibited by cyclosporin A or interferon-α treatment. J Gen Virol. 2013;94(8):1749–1760. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.052910-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Falzarano Darryl, de Wit Emmie, Martellaro Cynthia, Callison Julie, Munster Vincent J, Feldmann Heinz. Inhibition of novel β coronavirus replication by a combination of interferon-α2b and ribavirin. http://www.nature.com/srep/2013/130418/srep01686/pdf/srep01686.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Chan KS, Lai ST, Chu CM, Tsui E, Tam CY, et al. Treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome with lopinavir/ritonavir: A multicentre retrospective matched cohort study. Hong Kong Med J. 2003;9:399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]