Abstract

BACKGROUND

Left ventricular hypertrophy assessed by electrocardiography (ECG-LVH) is a marker of subclinical cardiac damage and a strong predictor of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events. The prevalence of ECG-LVH is increased in obesity and type 2 diabetes; however, there are no data on the long-term effects of weight loss on ECG-LVH. The purpose of this study was to determine whether an intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI) reduces ECG-LVH in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes.

METHODS

Data from 4,790 Look AHEAD participants (mean age: 58.8 ± 6.8 years, 63.2% White) who were randomized to a 10-year ILI (n = 2,406) or diabetes support and education (DSE, n = 2,384) were included. ECG-LVH defined by Cornell voltage criteria was assessed every 2 years. Longitudinal logistic regression analysis with generalized estimation equations and linear mixed models were used to compare the prevalence of ECG-LVH and changes in absolute Cornell voltage over time between intervention groups, with tests of interactions by sex, race/ethnicity, and baseline CVD status.

RESULTS

The prevalence of ECG-LVH at baseline was 5.2% in the DSE group and 5.0% in the ILI group (P = 0.74). Over a median 9.5 years of follow-up, prevalent ECG-LVH increased similarly in both groups (odds ratio: 1.02, 95% confidence interval: 0.83–1.25; group × time interaction, P = 0.49). Increases in Cornell voltage during follow-up were also similar between intervention groups (group × time interaction, P = 0.57). Intervention effects were generally similar between subgroups of interest.

CONCLUSIONS

The Look AHEAD long-term lifestyle intervention does not significantly lower ECG-LVH in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes.

CLINICAL TRIALS REGISTRATION

Trial Number NCT00017953 (ClinicalTrials.gov)

Keywords: blood pressure, diabetes, electrocardiography, exercise, hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, obesity, weight loss

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are major risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD), and this is due, in part, to adverse effects on cardiac structure and function.1–4 Several studies demonstrate that both obesity and diabetes are independent predictors of increased left ventricular (LV) mass, and having both conditions may increase the odds of LV hypertrophy (LVH) by up to 3-fold.4–6 LVH can be readily assessed using standard 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG), from which a number of voltage-based criteria have been proposed.7 ECG-LVH is a strong predictor of future CVD events,8,9 and regression of ECG-LVH is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.10,11 Thus, ECG-LVH may be a useful surrogate endpoint for studies assessing changes in CVD risk over time.

Exercise and weight loss are recommended to lower risk of CVD events in individuals with type 2 diabetes.12 There is some evidence that improvements in LV mass with lifestyle intervention may be related to favorable changes in body weight, glycemic control, and cardiorespiratory fitness; however, a more rigorous investigation is needed.13 To our knowledge, there are currently no randomized clinical trials on the long-term effects of weight loss on ECG-LVH. Thus, the purpose of this study was to determine whether a structured weight loss intervention reduces ECG-LVH in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes from the Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) trial.

METHODS

Study design

Look AHEAD was a multicenter randomized clinical trial designed to examine the effects of an intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI) compared with a diabetes support and education (DSE) control on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. A total of 5,145 individuals were recruited from 16 centers throughout the United States between 2001 and 2004. The study design and baseline characteristics of the randomized participants were published previously.14,15 Individuals with type 2 diabetes were eligible if they were 45–76 years old, overweight or obese based on BMI ≥25 kg/m2 (>27 kg/m2 if currently taking insulin), and able to complete a maximal exercise test. Major exclusion criteria included hemoglobin A1c >11%, blood pressure ≥160/100 mm Hg, triglycerides ≥600 mg/dl, weight >350 lbs, CVD events in the previous 3 months, or recent weight loss. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each center and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00017953).

Study interventions

The ILI involved a combination of group and individual sessions during a 4-year period with the most intensive application during year 1 and less frequent attention during years 2–4.16 During an extended follow-up period, ILI participants were encouraged to continue having one individual contact per month and were offered at least 2 group classes and courses each year to help maintain eating and physical activity behaviors that promote weight loss. Participants were instructed to reduce their energy intake to 1,200–1,800 kcal/day depending on body weight and increase their physical activity to ≥175 min/week (with intensity prescribed as moderate to vigorous, e.g., brisk walking) in order to achieve and maintain 5–10% weight loss. Participants randomized to DSE were invited to attend 3 group sessions per year during the active phase of the intervention and one session per year during the follow-up phase.17 These sessions provided general information on topics related to diet, physical activity, and social support, but not specific behavioral strategies that would result in weight or fitness changes. Although the active intervention ended in September 2012, the ILI produced significantly greater weight losses relative to DSE, which were maintained across the entire study period (average of 9.6 years of follow-up).18

Assessment of ECG-LVH

Standard 12-lead ECGs were recorded with the participant resting in the supine position after an overnight fast at baseline and every other year thereafter using MAC electrocardiographs (Marquette Electronics, Milwaukee, WI). Digitized tracings were transmitted to the Look AHEAD ECG Reading Center at Wake Forest School of Medicine for centralized reading and data processing. All ECGs were visually inspected for technical errors and inadequate quality. Using the Cornell voltage criteria, ECG-LVH was defined as RaVL + SV3 >2,800 µV in men and >2,000 µV in women based on the sum of the R-wave amplitude in lead aVL and the S-wave amplitude in lead V3.7,19

Other variables of interest

Standardized interviewer-administered questionnaires were used to obtain information on demographics, socioeconomic status, medical history, and medication use. Weight and height were measured in duplicate using a digital scale and a standard, wall-mounted stadiometer. History of CVD at baseline was defined by self-report as a history of myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass, angioplasty/stent procedures, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, stable angina, and congestive heart failure. Standard procedures were used to measure waist circumference, blood pressure, and blood chemistries, as previously described.15 A graded exercise treadmill test was used to assess cardiorespiratory fitness.20

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle and all available follow-up data were included. Data were restricted to those obtained prior to September 14, 2012 (i.e., the intervention phase of Look AHEAD), when the median follow-up was 9.5 years. Baseline CVD risk factors were compared between groups using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Longitudinal logistic regression analysis with generalized estimation equations was used to compare the prevalence of ECG-LVH during follow-up, adjusting for baseline ECG-LVH status and study visit. Linear mixed models were used to assess the impact of intervention assignment on the absolute Cornell voltage over time, including the baseline value and study visit as covariates. Secondary models included time-varying BMI to account for the potentially confounding effects of changes in chest size and body fat on the ECG signal, as well as baseline systolic blood pressure, time-varying systolic blood pressure, and time-varying antihypertensive medication use to account for the potentially confounding effect of hypertension on LV mass. Tests of interaction were examined by sex, race/ethnicity, and baseline CVD status. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by removing participants with evidence of interventricular conduction defects at baseline, defined as a QRS duration ≥120 ms. We also examined whether the magnitude of weight loss (≥10% vs. <10% weight loss at each visit, included as a time-varying covariate in the fully adjusted model), influenced the outcomes.

RESULTS

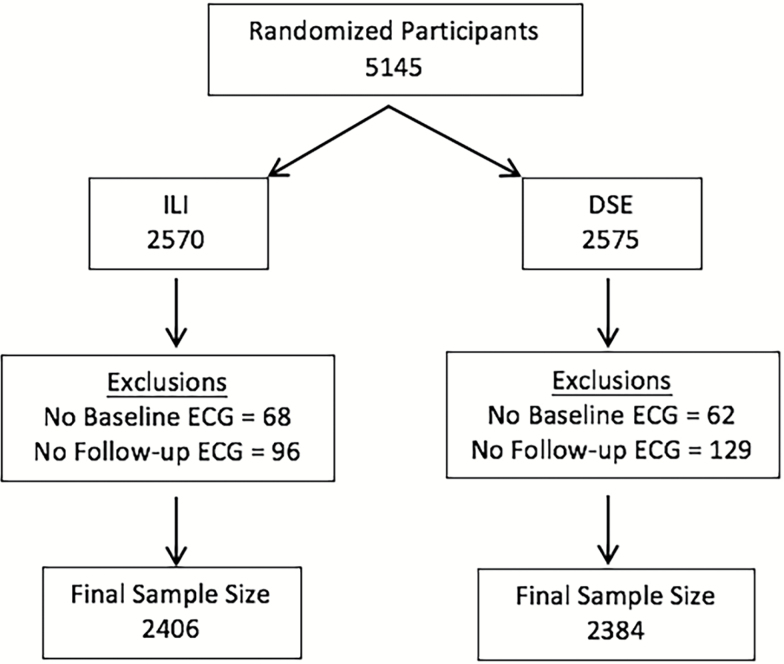

The present analysis included 4,790 Look AHEAD participants who completed a baseline ECG assessment and at least 1 ECG assessment during the 10-year follow-up period (Figure 1). This sample included 805 (33.8%) and 812 (33.8%) with 5 follow-up ECG measures, 1,159 (48.6%) and 1,201 (49.9%) with 4 follow-up ECG measures, 228 (9.6%) and 227 (9.4%) with 3 follow-up ECG measures, 104 (4.4%) and 88 (3.7%) with 2 follow-up ECG measures, and 88 (3.7%) and 78 (3.2%) with 1 follow-up ECG measure, in the DSE and ILI groups, respectively. Baseline demographics were similar between intervention groups (Table 1), with the exception of systolic blood pressure, which was slightly higher in the DSE group (P = 0.01). Participants who were excluded from this analysis were slightly younger than those who were included (57.4 vs. 58.8 years), but were otherwise similar.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram. Abbreviations: DSE, diabetes support and education; ECG, electrocardiography; ILI, intensive lifestyle intervention.

Table 1.

Cardiovascular disease risk factors at baseline by randomization arm (N = 4,790)

| DSE | ILI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2,384 | 2,406 | |

| Age (years) | 58.9 (6.9) | 58.6 (6.8) | 0.14 |

| Sex | |||

| Women | 1,433 (60.1) | 1,429 (59.4) | 0.61 |

| Men | 951 (39.9) | 977 (40.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.97 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1,505 (63.1) | 1,521 (63.2) | |

| African American | 379 (15.9) | 376 (15.6) | |

| Hispanic | 307 (12.9) | 305 (12.7) | |

| Other | 193 (8.1) | 203 (8.4) | |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 154 (6.6) | 152 (6.4) | 0.79 |

| High school graduate | 433 (18.7) | 424 (18.0) | |

| College graduate | 1,733 (74.7) | 1,782 (75.6) | |

| History of CVD | 0.31 | ||

| Yes | 315 (13.2) | 342 (14.2) | |

| No | 2,069 (86.8) | 2,064 (85.8) | |

| Diabetes duration | 0.41 | ||

| Less than 5 years | 1,063 (44.9) | 1,097 (46.0) | |

| At least 5 years | 1,307 (55.1) | 1,285 (54.0) | |

| Use of diabetes medications | |||

| None | 280 (12.2) | 288 (12.4) | 0.90 |

| Oral meds only | 1,647 (71.7) | 1,678 (72.0) | |

| Insulin | 370 (16.1) | 364 (15.6) | |

| Use of lipid-lowering medications | |||

| Yes | 1,145 (49.2) | 1,179 (49.9) | 0.53 |

| No | 1,182 (5.8) | 1,173 (50.1) | |

| Use of antihypertensive medications | |||

| Yes | 1,687 (72.1) | 1,735 (72.8) | 0.58 |

| No | 652 (27.9) | 647 (27.2) | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 1,225 (51.5) | 1,199 (49.9) | 0.52 |

| Past | 1,055 (44.4) | 1,098 (45.7) | |

| Current | 97 (4.1) | 105 (4.4) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||

| Less than 30 | 336 (14.8) | 372 (16.3) | 0.38 |

| 30–39 | 1,398 (61.5) | 1,379 (60.3) | |

| 40+ | 540 (23.7) | 535 (23.4) | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | |||

| Women | 111.1 (13.3) | 110.4 (13.6) | 0.19 |

| Men | 118.3 (13.0) | 118.6 (14.0) | 0.54 |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||

| Systolic | 129.4 (17.1) | 128.1 (17.3) | 0.01 |

| Diastolic | 70.2 (9.6) | 69.9 (9.5) | 0.22 |

| Fitness (METS 80% HR) | 5.1 (1.5) | 5.2 (1.5) | 0.09 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 190.2 (37.3) | 190.9 (38.0) | 0.52 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 43.6 (11.7) | 43.5 (11.9) | 0.76 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 111.7 (32.4) | 111.9 (32.0) | 0.87 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 179.8 (119.5) | 181.5 (112.8) | 0.62 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 7.3 (1.2) | 7.3 (1.1) | 0.38 |

| Renal function | |||

| ACR (mg/g) | 0.047 (0.23) | 0.046 (0.20) | 0.88 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 90.0 (15.9) | 90.3 (16.3) | 0.55 |

| Prevalence of ECG-LVH | 123 (5.2) | 119 (5.0) | 0.74 |

Data are expressed as frequency (%) or means (SD); P values are based on chi-square or t-tests. Abbreviations: ACR, albumin-to-creatinine ratio; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DSE, diabetes support and education; ECG-LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy assessed by electrocardiography; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; ILI, intensive lifestyle intervention; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; METS, metabolic equivalents.

The prevalence of ECG-LVH at baseline was similar between intervention groups (ILI: 5.0%, DSE: 5.2%, P = 0.74; Table 1), but differed between subgroups of interest. The baseline prevalence of ECG-LVH was substantially higher in women vs. men (7.7% vs. 1.1%; P < 0.0001) and slightly higher in individuals with vs. without a history of CVD (6.4% vs. 4.8%; P = 0.09). In addition, there were differences by race/ethnicity (P < 0.0001) with African Americans having the highest prevalence of ECG-LVH at baseline (10.5%), followed by Hispanics (6.1%); non-Hispanic Whites had the lowest prevalence (3.1%). The observed subgroup differences were similar across intervention groups.

As previously reported, the ILI produced sustained reductions in body weight across the intervention period.18 In the present analysis, mean weight losses at years 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 were −6.4%, −4.7%, −4.7%, −5.3%, and −5.9%, respectively, in the ILI group compared to weight losses of −1.0%, −1.2%, −1.9%, −2.7%, and −3.4%, respectively, in the DSE group. Changes in body weight, cardiorespiratory fitness, systolic blood pressure, and antihypertensive medication use across follow-up are shown by intervention group in Supplementary Table 1.

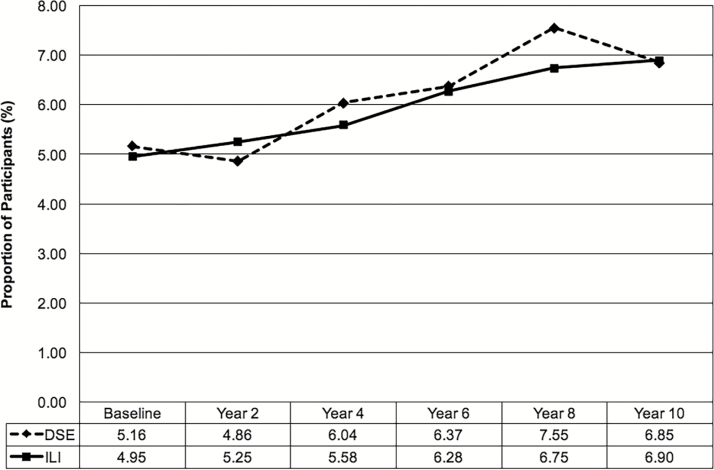

As shown in Figure 2, the prevalence of ECG-LVH increased to ~6.9% in both intervention groups by year 10. Overall, the prevalence of ECG-LVH during follow-up was similar between groups: odds ratio for DSE vs. ILI: 1.02, 95% confidence interval: 0.83–1.25; group × time interaction, P = 0.49. There were no significant interactions with sex or race/ethnicity; however, the interaction between baseline CVD status and intervention group was significant (P = 0.045). Among participants with a history of CVD, those randomized to the DSE group were more likely to have ECG-LVH during follow-up compared to those randomized to ILI (odds ratio for DSE vs. ILI: 1.67, 95% confidence interval: 0.96–2.91; P = 0.07), which was not observed in those without a history of CVD (odds ratio for DSE vs. ILI: 0.96, 95% confidence interval: 0.77–1.21; P = 0.76). Results were essentially the same when models were adjusted for time-varying BMI, systolic blood pressure, and antihypertensive medication use (Table 2) and after removing 172 participants with a baseline QRS duration ≥120 ms (although the intervention effect in those with a history of CVD was weakened, P = 0.13). Results from the fully adjusted models indicate that higher systolic blood pressure across follow-up was associated with greater prevalence of ECG-LVH (Supplementary Table 2). The magnitude of weight loss, however, was not associated with ECG-LVH prevalence (odds ratio for ≥10% vs. <10% weight loss: 1.08, 95% confidence interval: 0.87–1.33; P = 0.49).

Figure 2.

ECG-LVH by intervention group. Trajectories over time did not differ between intervention groups, P = 0.49. Abbreviations: DSE, diabetes support and education; ECG-LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy assessed by electrocardiography; ILI, intensive lifestyle intervention.

Table 2.

Odds ratios and 95% CI for prevalent ECG-LVH in DSE vs. ILI overall and in subgroups of interesta

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Overall | 1.02 | 0.83–1.25 | 0.87 | 1.01 | 0.82–1.25 | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.81–1.23 | 0.96 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Men | 0.99 | 0.55–1.77 | 0.96 | 1.06 | 0.58–1.93 | 0.85 | 1.08 | 0.58–2.00 | 0.82 |

| Women | 1.00 | 0.80–1.25 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.79–1.25 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.77–1.21 | 0.78 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.92 | 0.68–1.23 | 0.56 | 0.93 | 0.69–1.26 | 0.66 | 0.93 | 0.68–1.26 | 0.65 |

| African American | 1.11 | 0.75–1.64 | 0.61 | 1.11 | 0.75–1.65 | 0.59 | 1.06 | 0.72–1.56 | 0.78 |

| Hispanic | 1.14 | 0.59–2.18 | 0.70 | 1.11 | 0.58–2.12 | 0.76 | 0.89 | 0.48–1.65 | 0.72 |

| Other | 1.37 | 0.76–2.45 | 0.29 | 1.22 | 0.66–2.24 | 0.53 | 1.15 | 0.62–2.13 | 0.65 |

| History of CVD | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.67 | 0.96–2.91 | 0.07 | 1.72 | 0.98–3.01 | 0.06 | 1.74 | 0.95–3.17 | 0.07 |

| No | 0.96 | 0.77–1.21 | 0.76 | 0.95 | 0.76–0.19 | 0.66 | 0.91 | 0.73–1.15 | 0.44 |

Model 1 adjusts for visit and baseline ECG-LVH status. Model 2 adjusts for visit, baseline ECG-LVH status, and time-varying BMI. Model 3 adjusts for visit, baseline ECG-LVH status, time-varying BMI, baseline systolic blood pressure, time-varying systolic blood pressure, and time-varying antihypertensive medication use. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DSE, diabetes support and education; ECG-LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy assessed by electrocardiography; ILI, intensive lifestyle intervention; OR, odds ratio.

aTests of interactions with intervention group were significant for baseline CVD status (P = 0.045), but not sex (P = 0.85) or race/ethnicity (P = 0.79).

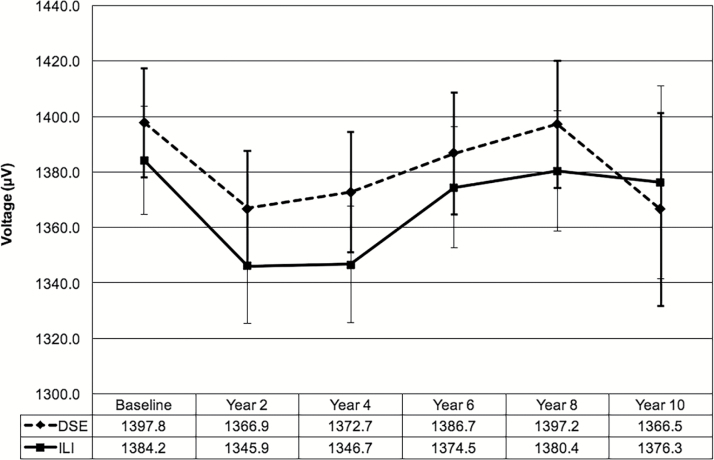

The mean (SD) absolute Cornell voltage was similar in the DSE and ILI groups at baseline: 1,397 (487) µV vs. 1,384 (485) µV, respectively (P = 0.33). During follow-up there were similar increases in Cornell voltage between groups overall (Figure 3; group × time interaction, P = 0.57), with a marginal mean (SE) difference of 19.4 (12.7) µV between groups (P = 0.13, Table 3). While the magnitude of the intervention effect differed across subgroups of interest (Table 3), similar effects were observed when stratified by sex, race/ethnicity, and history of CVD. These results were unchanged after adjusting for time-varying BMI, systolic blood pressure, and antihypertensive medication use and after removing participants with a baseline QRS duration ≥120 ms. Higher systolic blood pressure at baseline and during follow-up and not using antihypertensive medications were associated with higher Cornell voltage (Supplementary Table 2). Greater weight loss was also modestly associated with Cornell voltage, such that participants who achieved ≥10% weight loss had a Cornell voltage that was about 15 µV lower than those who achieved <10% weight loss: β = −14.8 (7.4) µV; P = 0.046.

Figure 3.

Mean Cornell voltage and 95% confidence intervals by intervention group. Trajectories over time did not differ between intervention groups, P = 0.57. Abbreviations: DSE, diabetes support and education; ILI, intensive lifestyle intervention.

Table 3.

Linear regression results for the effect of randomization to DSE vs. ILI on absolute Cornell voltage overall and in subgroups of interesta

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| â | SE | P value | â | SE | P value | â | SE | P value | |

| Overall | 19.4 | 12.7 | 0.13 | 20.9 | 127 | 0.10 | 16.0 | 12.6 | 0.21 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Men | 29.8 | 21.9 | 0.17 | 31.6 | 21.9 | 0.15 | 26.7 | 21.7 | 0.22 |

| Women | 16.4 | 14.7 | 0.27 | 16.0 | 14.9 | 0.28 | 12.7 | 14.7 | 0.39 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 13.5 | 16.3 | 0.41 | 15.3 | 16.3 | 0.35 | 11.9 | 16.2 | 0.46 |

| African American | 45.0 | 32.2 | 0.16 | 46.5 | 32.4 | 0.15 | 31.4 | 32.0 | 0.33 |

| Hispanic | 33.0 | 33.3 | 0.32 | 34.5 | 33.5 | 0.30 | 22.2 | 33.2 | 0.50 |

| Other | 3.2 | 41.3 | 0.94 | -0.60 | 42.1 | >0.99 | 4.0 | 42.0 | 0.92 |

| History of CVD | |||||||||

| Yes | 57.3 | 39.6 | 0.15 | 58.8 | 39.5 | 0.14 | 52.5 | 39.2 | 0.18 |

| No | 14.4 | 13.4 | 0.28 | 15.5 | 13.5 | 0.25 | 10.6 | 13.3 | 0.42 |

Model 1 adjusts for visit and baseline Cornell voltage. Model 2 adjusts for visit, baseline Cornell voltage, and time-varying BMI. Model 3 adjusts for visit, baseline Cornell voltage, time-varying BMI, baseline systolic blood pressure, time-varying systolic blood pressure, and time-varying antihypertensive medication use. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DSE, diabetes support and education; ILI, intensive lifestyle intervention.

aTests of interactions between intervention group and sex (P = 0.37), race/ethnicity (P = 0.95), and baseline CVD status (P = 0.23) were all nonsignificant.

DISCUSSION

We determined the effects of weight loss on ECG-LVH in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes from the Look AHEAD trial. Obesity causes notable changes in the ECG that reflect alterations in cardiac structure and function, as well as abdominal enlargement and heart displacement. Accordingly, reductions in body weight may help restore normal ECG patterns through favorable changes in cardiac geometry (e.g., reduced LVH) and orientation. We hypothesized that weight loss induced by caloric restriction and increased physical activity would reduce ECG-LVH in Look AHEAD participants. In contrast to our hypothesis, we found that the Look AHEAD long-term lifestyle intervention did not significantly lower the prevalence of ECG-LVH in this population.

Several studies show that weight loss leads to reductions in LV mass, as assessed by echocardiography or magnetic resonance imaging.13,21–24 One study by Hammer et al., which specifically examined the effects of weight loss on LV mass in obese individuals with type 2 diabetes, found that a very low-calorie diet (plus an exercise program in half the participants) reduced LV mass by 16%.25 However, the sample size was small (n = 12), the duration of the intervention was relatively short (16 weeks), and there was no control group. Few studies have reported the effects of weight loss on ECG markers of LVH.26,27 Alpert et al. found that surgically induced weight loss in normotensive morbidly obese subjects led to a significant reduction in ECG-LVH, as assessed by a variety of different criteria.26 Although they did not look specifically at Cornell voltage, they did observe a significant reduction in RaVL amplitude, suggesting that fewer participants met Cornell voltage criteria for ECG-LVH after weight loss. Pontiroli et al. reported a reduction in SV3 (but not RaVL) amplitude 1 year after bariatric surgery in obese individuals; however, this improvement was observed in subjects whose blood pressure normalized during the follow-up period, but not in those who remained hypertensive.28 To our knowledge, we are the first study to report long-term changes in ECG-LVH following caloric restriction and exercise. Our results show that randomization to an ILI, which produced, on average, less weight loss (~6% at their last measurement during the intervention period) compared to the much larger weight losses (i.e., >15%) achieved in the bariatric surgery studies, did not reduce the overall prevalence of ECG-LVH. Interestingly, we found that Cornell voltage was significantly lower in those who lost ≥10% body weight; yet, this did not translate to a lower prevalence of ECG-LVH, suggesting that a substantial amount of weight loss may be necessary to reduce ECG-LVH using standard criteria. As reported previously, systolic blood pressure and antihypertensive medication use were lower in the ILI group across 10 years of follow-up.18 Although reductions in systolic blood pressure were associated with lower prevalence of ECG-LVH and reduced Cornell voltage, accounting for changes in blood pressure and medications during follow-up did not alter the results.

While there was no overall intervention effect on ECG-LVH, we did observe a slight moderating effect of CVD status. In fact, our results suggest that individuals with a history of CVD were more likely to have ECG-LVH during the intervention period if they were randomized to the DSE group, although the association did not reach statistical significance and was further attenuated after removing individuals with interventricular conduction defects (e.g., left or right bundle branch block).18 We also observed significant differences in the prevalence of ECG-LVH across sex and racial/ethnic subgroups at baseline; however, the intervention response did not differ between these groups. Notably, in our study women and minorities had a higher prevalence of ECG-LVH compared to men and non-Hispanic Whites, respectively. Sex differences have been reported previously using Cornell voltage criteria in population-based studies.29–31 Although we had limited power for the subgroup analyses, the observed differences were greater in our cohort (i.e., 7-fold vs. 3-fold). Racial/ethnic differences in ECG-LVH have also been reported in prior studies and are consistent with our findings of more prevalent ECG-LVH in African Americans vs. non-Hispanic Whites, with intermediate prevalence in Hispanics.29,32,33

Despite its widespread availability, relatively low cost, ease of use, and high specificity, the clinical utility of ECG is limited by its low sensitivity for detecting LVH. This is due, in part, to the increased amount of thoracic adipose tissue (i.e., chest wall fat and/or epicardial fat) in overweight and obese patients, which increases the distance between the myocardium and thoracic electrodes and effectively reduces precordial ECG voltages.34 At the same time, obesity-related increases in the LV mass-to-volume ratio in the absence of LVH (i.e., concentric LV remodeling) can result in increased ECG values, thereby reducing the specificity of ECG in some obese individuals.35 Although many of the ECG criteria are highly dependent on body habitus,36,37 Cornell voltage may have superior diagnostic performance for the detection of LVH in overweight and obese individuals compared to other criteria likely because it is partially independent of precordial voltages and better reflects the posterior-horizontal direction of electrical forces associated with LVH.31,36–38 As such, our finding that absolute Cornell voltage increased during follow-up, as did the prevalence of ECG-LVH using corresponding criteria, suggests that anatomic LV mass likely increased in both groups during the 10-year period. Moreover, recent data suggest that accounting for the effects of BMI on ECG voltages may improve the sensitivity of ECG-LVH criteria.39,40 In secondary analyses, we adjusted for time-varying BMI to account for potential changes in thoracic adipose tissue with weight loss. Our results were unchanged, suggesting that changes in body weight had no major effect on the ability of Cornell voltage criteria to assess changes in the prevalence of ECG-LVH during follow-up.

The strengths of this analysis include the large, well-characterized cohort with good retention and many years of follow-up; however, there are several limitations. We used ECG to assess LVH which, as described above, is an indirect measure that presents some diagnostic challenges in overweight and obese individuals. Although our use of Cornell voltage criteria, along with models adjusted for prospective changes in BMI, may have minimized major biases related to body size, the true effect of the ILI on changes in LV mass cannot be determined. It is also possible that defining ECG-LVH based on other criteria such as Cornell product, Sokolow-Lyon, or Romhilt-Estes, could lead to different results and alter the conclusions. Another limitation is the relatively small number of racial/ethnic minorities and participants with a prior history of CVD, which may have limited our ability to detect associations in these subgroups. Furthermore, as with all randomized clinical trials, the study results may not be widely generalizable given the specific patient population, trial design, and selection of study measures.

In conclusion, our study showed that a long-term lifestyle intervention did not significantly lower ECG-LVH, as compared with a diabetes education control, among overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary data are available at American Journal of Hypertension online.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by DHHS/NIH cooperative agreements (DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, DK56992); NIDDK; NHLBI; NINR; NCMHD; NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) provided personnel, medical oversight, and use of facilities.

REFERENCES

- 1. Eguchi K, Boden-Albala B, Jin Z, Rundek T, Sacco RL, Homma S, Di Tullio MR. Association between diabetes mellitus and left ventricular hypertrophy in a multiethnic population. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101:1787–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Russo C, Jin Z, Homma S, Rundek T, Elkind MS, Sacco RL, Di Tullio MR. Effect of obesity and overweight on left ventricular diastolic function: a community-based study in an elderly cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57:1368–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Turkbey EB, McClelland RL, Kronmal RA, Burke GL, Bild DE, Tracy RP, Arai AE, Lima JA, Bluemke DA. The impact of obesity on the left ventricle: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2010; 3:266–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lauer MS, Anderson KM, Kannel WB, Levy D. The impact of obesity on left ventricular mass and geometry. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA 1991; 266:231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Simone G, Palmieri V, Bella JN, Celentano A, Hong Y, Oberman A, Kitzman DW, Hopkins PN, Arnett DK, Devereux RB. Association of left ventricular hypertrophy with metabolic risk factors: the HyperGEN study. J Hypertens 2002; 20:323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Paranicas M, O’Grady MJ, Lee ET, Welty TK, Fabsitz RR, Robbins D, Rhoades ER, Howard BV. Impact of diabetes on cardiac structure and function: the strong heart study. Circulation 2000; 101:2271–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hancock EW, Deal BJ, Mirvis DM, Okin P, Kligfield P, Gettes LS, Bailey JJ, Childers R, Gorgels A, Josephson M, Kors JA, Macfarlane P, Mason JW, Pahlm O, Rautaharju PM, Surawicz B, van Herpen G, Wagner GS, Wellens H; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; American College of Cardiology Foundation; Heart Rhythm Society . AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:992–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Levy D, Salomon M, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Prognostic implications of baseline electrocardiographic features and their serial changes in subjects with left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation 1994; 90:1786–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Gattobigio R, Zampi I, Porcellati C. Prognostic value of a new electrocardiographic method for diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy in essential hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 31:383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Okin PM, Devereux RB, Jern S, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Nieminen MS, Snapinn S, Harris KE, Aurup P, Edelman JM, Wedel H, Lindholm LH, Dahlöf B; LIFE Study Investigators . Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy during antihypertensive treatment and the prediction of major cardiovascular events. JAMA 2004; 292:2343–2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Prineas RJ, Rautaharju PM, Grandits G, Crow R; MRFIT Research Group . Independent risk for cardiovascular disease predicted by modified continuous score electrocardiographic criteria for 6-year incidence and regression of left ventricular hypertrophy among clinically disease free men: 16-year follow-up for the multiple risk factor intervention trial. J Electrocardiol 2001; 34:91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buse JB, Ginsberg HN, Bakris GL, Clark NG, Costa F, Eckel R, Fonseca V, Gerstein HC, Grundy S, Nesto RW, Pignone MP, Plutzky J, Porte D, Redberg R, Stitzel KF, Stone NJ; American Heart Association; American Diabetes Association . Primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in people with diabetes mellitus: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Circulation 2007; 115:114–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kosmala W, O’Moore-Sullivan T, Plaksej R, Przewlocka-Kosmala M, Marwick TH. Improvement of left ventricular function by lifestyle intervention in obesity: contributions of weight loss and reduced insulin resistance. Diabetologia 2009; 52:2306–2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ryan DH, Espeland MA, Foster GD, Haffner SM, Hubbard VS, Johnson KC, Kahn SE, Knowler WC, Yanovski SZ; Look AHEAD Research Group . Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Control Clin Trials 2003; 24:610–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bray G, Gregg E, Haffner S, Pi-Sunyer XF, WagenKnecht LE, Walkup M, Wing R. Baseline characteristics of the randomised cohort from the look ahead (action for health in diabetes) study. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2006; 3:202–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wadden TA, West DS, Delahanty L, Jakicic J, Rejeski J, Williamson D, Berkowitz RI, Kelley DE, Tomchee C, Hill JO, Kumanyika S; Look AHEAD Research Group . The Look AHEAD study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006; 14:737–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wesche-Thobaben JA. The development and description of the comparison group in the Look AHEAD trial. Clin Trials 2011; 8:320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Clark JM, Coday M, Crow RS, Curtis JM, Egan CM, Espeland MA, Evans M, Foreyt JP, Ghazarian S, Gregg EW, Harrison B, Hazuda HP, Hill JO, Horton ES, Hubbard VS, Jakicic JM, Jeffery RW, Johnson KC, Kahn SE, Kitabchi AE, Knowler WC, Lewis CE, Maschak-Carey BJ, Montez MG, Murillo A, Nathan DM, Patricio J, Peters A, Pi-Sunyer X, Pownall H, Reboussin D, Regensteiner JG, Rickman AD, Ryan DH, Safford M, Wadden TA, WagenKnecht LE, West DS, Williamson DF, Yanovski SZ. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Casale PN, Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Campo E, Kligfield P. Improved sex-specific criteria of left ventricular hypertrophy for clinical and computer interpretation of electrocardiograms: validation with autopsy findings. Circulation 1987; 75:565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jakicic JM, Jaramillo SA, Balasubramanyam A, Bancroft B, Curtis JM, Mathews A, Pereira M, Regensteiner JG, Ribisl PM; Look AHEAD Study Group . Effect of a lifestyle intervention on change in cardiorespiratory fitness in adults with type 2 diabetes: results from the Look AHEAD Study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009; 33:305–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hinderliter A, Sherwood A, Gullette EC, Babyak M, Waugh R, Georgiades A, Blumenthal JA. Reduction of left ventricular hypertrophy after exercise and weight loss in overweight patients with mild hypertension. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162:1333–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Himeno E, Nishino K, Nakashima Y, Kuroiwa A, Ikeda M. Weight reduction regresses left ventricular mass regardless of blood pressure level in obese subjects. Am Heart J 1996; 131:313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reid CM, Dart AM, Dewar EM, Jennings GL. Interactions between the effects of exercise and weight loss on risk factors, cardiovascular haemodynamics and left ventricular structure in overweight subjects. J Hypertens 1994; 12:291–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de las Fuentes L, Waggoner AD, Mohammed BS, Stein RI, Miller BV 3rd, Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Klein S, Davila-Roman VG. Effect of moderate diet-induced weight loss and weight regain on cardiovascular structure and function. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54:2376–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hammer S, Snel M, Lamb HJ, Jazet IM, van der Meer RW, Pijl H, Meinders EA, Romijn JA, de Roos A, Smit JW. Prolonged caloric restriction in obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus decreases myocardial triglyceride content and improves myocardial function. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52:1006–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alpert MA, Terry BE, Hamm CR, Fan TM, Cohen MV, Massey CV, Painter JA. Effect of weight loss on the ECG of normotensive morbidly obese patients. Chest 2001; 119:507–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eisenstein I, Edelstein J, Sarma R, Sanmarco M, Selvester RH. The electrocardiogram in obesity. J Electrocardiol 1982; 15:115–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pontiroli AE, Pizzocri P, Saibene A, Girola A, Koprivec D, Fragasso G. Left ventricular hypertrophy and QT interval in obesity and in hypertension: effects of weight loss and of normalisation of blood pressure. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004; 28:1118–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rautaharju PM, Zhou SH, Calhoun HP. Ethnic differences in ECG amplitudes in North American white, black, and Hispanic men and women. Effect of obesity and age. J Electrocardiol 1994; 27 (Suppl):20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Porthan K, Niiranen TJ, Varis J, Kantola I, Karanko H, Kähönen M, Nieminen MS, Salomaa V, Huikuri HV, Jula AM. ECG left ventricular hypertrophy is a stronger risk factor for incident cardiovascular events in women than in men in the general population. J Hypertens 2015; 33:1284–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cuspidi C, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Sala C, Grassi G, Mancia G. Accuracy and prognostic significance of electrocardiographic markers of left ventricular hypertrophy in a general population: findings from the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate E Loro Associazioni population. J Hypertens 2014; 32:921–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Okin PM, Wright JT, Nieminen MS, Jern S, Taylor AL, Phillips R, Papademetriou V, Clark LT, Ofili EO, Randall OS, Oikarinen L, Viitasalo M, Toivonen L, Julius S, Dahlöf B, Devereux RB. Ethnic differences in electrocardiographic criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy: the LIFE study. Losartan intervention for endpoint. Am J Hypertens 2002; 15:663–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jain A, Tandri H, Dalal D, Chahal H, Soliman EZ, Prineas RJ, Folsom AR, Lima JA, Bluemke DA. Diagnostic and prognostic utility of electrocardiography for left ventricular hypertrophy defined by magnetic resonance imaging in relationship to ethnicity: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am Heart J 2010; 159:652–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shirani J, Berezowski K, Roberts WC. Quantitative measurement of normal and excessive (cor adiposum) subepicardial adipose tissue, its clinical significance, and its effect on electrocardiographic QRS voltage. Am J Cardiol 1995; 76:414–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rodrigues JC, McIntyre B, Dastidar AG, Lyen SM, Ratcliffe LE, Burchell AE, Hart EC, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Hamilton MC, Paton JF, Nightingale AK, Manghat NE. The effect of obesity on electrocardiographic detection of hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy: recalibration against cardiac magnetic resonance. J Hum Hypertens 2016; 30:197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Abergel E, Tase M, Menard J, Chatellier G. Influence of obesity on the diagnostic value of electrocardiographic criteria for detecting left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Cardiol 1996; 77:739–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Okin PM, Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kligfield P. Electrocardiographic identification of left ventricular hypertrophy: test performance in relation to definition of hypertrophy and presence of obesity. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996; 27:124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Okin PM, Jern S, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, Dahlöf B; LIFE Study Group . Effect of obesity on electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients: the losartan intervention for endpoint (LIFE) reduction in hypertension study. Hypertension 2000; 35:13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Robinson C, Woodiwiss AJ, Libhaber CD, Norton GR. Novel approach to the detection of left ventricular hypertrophy using body mass index-corrected electrocardiographic voltage criteria in a group of African Ancestry. Clin Cardiol 2016; 39:524–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Angeli F, Verdecchia P, Iacobellis G, Reboldi G. Usefulness of QRS voltage correction by body mass index to improve electrocardiographic detection of left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol 2014; 114:427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.